RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

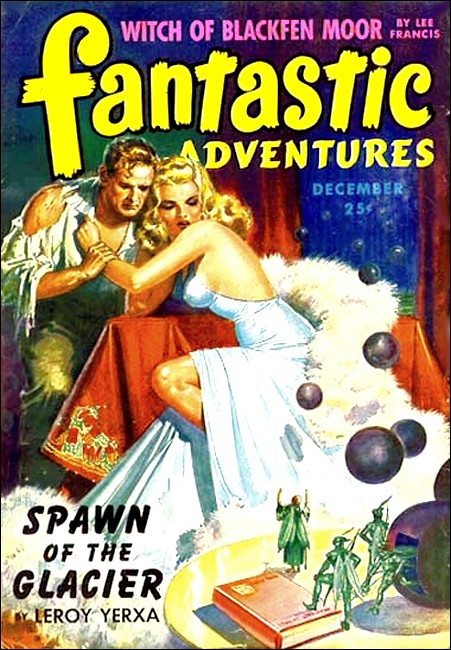

Fantastic Adventures, December 1943, with "Spawn of the Glacier"

From the heart of an age-old glacier came strange seeds that rattled. And from the seeds came a real threat to Earth.

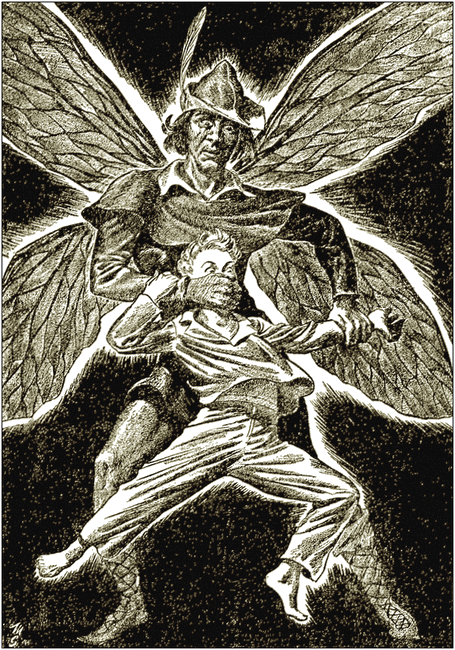

The boy struggled frantically, but the green man's hold only tightened.

THE single smoke-blackened room of the igloo was warm and held the stench of unwashed bodies, rotten fish and sweating dogs. The odors mingled until Art McFarland wanted to forget that hospitality demanded certain inconveniences. He longed to escape through the tunnel into the cold air outside.

But that wouldn't do. He was here at the invitation of Karau, who was a chief of no mean standing. McFarland curbed his natural impulses and continued to stare with a set grin at the fat, fur- covered Eskimo who crouched opposite him. Karau's smile was expansive. The big white teeth that were so much in evidence at this moment gave him the appearance of some toothy animal about to pounce on and devour its prey.

Karau was in doubt as to just what he might suggest in the manner of entertainment for this kabloona* Karau's wife was snoring loudly in her sleeping-bag. The two men munched seal and fish meat together and Karau's ideas for entertainment were nearly exhausted.

[*Eskimo for "white man." —Ed.]

Then an all-consuming grin lighted his face. Seeing it, McFarland suffered anew that urge to plunge outside and escape whatever might be coming. He had a horrible feeling that Karau might bring in a dog and tear it apart limb from limb in those huge, grist-mill teeth.

"MacFarland like story of coming life? Like fortune?"

Karau didn't wait for a reply. He stood up and shuffled across the igloo to crouch again before a blackened chest. In this chest he kept his entire fortune. He carefully removed a rusty frying pan, a sock with a large hole in the toe, several empty tin-cans, and at last, to his evident satisfaction, a battered teakettle. He replaced each item with loving care, save for the teakettle, and ambled back to his original squatting-place. The tea-kettle lacked both handle and spigot. As he flourished it, the kettle rattled as though filled with stones.

Karau placed the kettle on the floor in front of him, leaned close to McFarland and spoke in a loud whisper.

"Karau secret medicine man—wise man of tribe. Karau will tell you what is in your future."

McFarland sighed with relief. Karau had a bad case of halitosis, but even that was preferable to any of the more terrible things that might have happened.

"I guess McFarland can stand it," he said with a grin. "Probably I have a better future than I had a year ago."

He could see no advantage in telling this overfed Eskimo that a year ago doctors had given him up as a helpless wreck. He had been forced to leave the research laboratory of Plastics Inc., and come North for a rest.

"Frobisher Bay is a lonely place when we're frozen in," his old friend Ed Fisher had written the previous summer. "But the trading post is here, and I'm here. I'll guarantee you'll get a complete rest, and I do mean rest. You'll see nothing but natives and snow for six months. Wire me if you plan to come."

McFarland, for reasons that were a mystery to him now, had wired. That was last fall. In a week the first boat would come through from Canada. He'd go back to Plastics Inc. if they still wanted him.

He wondered what J. Manning Clark and his daughter, Sylvia, were doing at the moment. J. Manning Clark owned half of Plastics Inc. What about Sylvia? Probably running around with some one else by now.

"McFarland will watch close?"

HIS attention snapped back to Karau. The self-termed medicineman of Frobisher Bay was on his hands and knees. In his right hand, still greasy with remains of a half-rotted salmon, Karau was shaking a handful of small, round pellets. McFarland's thoughts slipped a cog, back to the last time he had thrown a pair of six's with the dotted bones. He watched the huge, hairy paw as it moved in rhythm and released the pellets. They rolled across the icy floor. Karau was crawling on all fours, his eyes shining. The pellets, each perhaps an inch in diameter, fanned out into a rough circle. McFarland watched with dreamy eyes. Only half his mind was on Karau as the dark man traced a thick finger from one pellet to another, marking an erratic trail on the dirty ice.

Karau scooped the pellets up and carefully dropped them back into the broken tea-kettle.

He studied the design for some time, then stared up at McFarland, apparently hoping his mumbo-jumbo had provoked interest. The American smiled.

"I suppose I have a future?"

Karau shook his head brightly.

"Big future." His eyes sparkled. "You catch ship soon and sail away?"

It was a question. Karau knew that he had said something that could not be denied. "You be glad to get back to white man country. You tell white men in big city you have friend in North name Karau. Very powerful friend— medicine man."

McFarland nodded, waiting for Karau to go on. He was gradually being overcome by the smell of the seal-oil lamp. His eyes moved slowly from side to side as the tiny curl of smoke arose from the flame.

Karau looked disappointed.

"That your fortune," he said, with a touch of resentment in his voice. What had the kabloona expected?

"Oh!" McFarland forced a polite smile. "Oh, yes! I should have known. Say, that's a pretty nice fortune, Karau. Darned if you aren't good."

Karau grinned happily.

"I hear whisper of voices in magic balls," he said proudly. "Karau only man in tribe who has them. Find in glacier very long distance away."

McFarland's interest suddenly grew. The fortune was about what he had expected from the slow-witted Karau. But the pellets, the small, round objects that Karau had tossed from the tea- kettle?

He leaned forward.

"Let's take a look at those things?"

A cunning look came into Karau's eyes.

"Powerful medicine," he said in a confidential whisper. "Be careful."

He pawed gently into the kettle and brought out a dozen of the pellets. He placed them carefully in McFarland's outstretched palm.

The sandy-haired man held them carefully. They were spheroids, having a slightly fiat surface on opposite sides. They reminded him of clay marbles, being about that size and color.

"Hold to ear and here whisper of magic." Karau was proud of his magic pellets. He wanted to show them off to their full advantage.

McFARLAND held them to his ear.

The motion of his hand made them rattle faintly as though they were filled with hard seeds. In spite of the urge to escape more of Karau's hospitality, McFarland was intrigued by these mysterious spheroids. They weren't like anything he had ever seen before. They reminded him somehow of seeds. Seeds that had dried and hardened to a rocklike composition. On the spur of the moment he held them toward Karau and opened his fingers. "How much?"

Karau was pleased. A crafty look came into his eyes. If the kabloona wanted these worthless balls, then the kabloona must think they were real magic. Karau had kept them because they brought him power in the tribe. The kabloona was ignorant to think that they really held magic power. Karau's understanding of the white man was limited. He was McFarland's best friend until trade articles were produced. Then Karau became shrewd and grasping. Perhaps, is he could argue well, McFarland would part with that sharp hunting- knife?

Karau shook his head violently.

"Powerful magic. Cannot sell."

McFarland knew his man. He hadn't worked at the post throughout the winter months without learning that lesson.

"Perhaps could trade?" Karau asked hopefully.

"No good," McFarland said with a smile. "They aren't worth much."

Karau was frightened. He wanted that knife. Wanted it more now than anything in the world. It was a fine knife and his eyes strayed to it and stayed there.

"Powerful magic," he repeated stubbornly. "Mighty fine magic."

McFarland had lost. With the look of one who had fought a battle and been beaten, he unbuckled his belt and slipped the knife and sheath from it. He held it before him.

"Knife—for all the magic balls?" he asked, and his lips were set in a determined line. Karau didn't hesitate. To hesitate now might lose him a wonderful knife. He emptied the tea-kettle in front of the white man.

Then grasping the knife, he drew it from the sheath and started to mumble delightedly over it.

McFarland stood up awkwardly. He had two handfuls of little brown marbles. Marbles that Karau had dug out of the ice on some forgotten glacier. Marbles that were hollow like seeds, and rattled.

"You're a hell of a trader," he thought, as he thanked Karau properly for a pleasant evening, and crawled out into the snow.

THE sun was rising slowly. The snow near the store was slushy

and black with a winter's accumulated filth.

McFarland stood for a time, staring into the south. He hoped that damned boat would get through and that Sylvia Clark would still have an occasional evening for him when he got back to Chicago.

A winter here would kill or cure a man. McFarland knew from the way his lungs responded to deep breaths of icy air, that he was cured.

Inside the trading post, he felt his way through the store and into the room at the rear. Fisher was snoring in complete comfort. McFarland slipped his purchase of rattling marbles into his duffle-bag and made a mental note not to tell Ed that he had fallen for an Eskimo's sucker game. He undressed, stretched his smooth, muscular body across the bunk and groaned in relaxation. With heavy blankets about his chin, McFarland went to sleep.

He dreamed that he had made a necklace of the rattling marbles and was placing it tenderly around Sylvia Clark's white throat. The marbles started to rattle and Sylvia screamed in terror. She kept insisting that the necklace was strangling her, and McFarland laughed.

"They're just full of teeth," he said, in the dream. "Karau's teeth. He keeps them there so he won't get them dirty. Karau's got the biggest teeth in the world."

RUDOLPH HALL thought Sylvia Clark the most stunning creature he had ever seen, and Hall was a splendid judge of beauty. Sylvia Clark was tall, just to the point of being willowy. Her hair had that fresh, vibrant color of newly woven yellow silk. Her tanned shoulders and bronzed face indicated that she had spent hours exposed to the sun. Now, in the dim light of J. Manning Clark's big study, her lips drooped a trifle with exhaustion. Her long lashed eyelids covered half of the deep blue of her eyes.

Rudolph Hall saw that the girl was blushing uncomfortably under his steady scrutiny, so he turned his attention reluctantly to his ex-wife, another object of beauty who sat near the fireplace.

Howard Steele, bald-headed and resigned, sat under his wife's wing near J. Manning Clark's desk. Their son, Jimmy, sat on the desk, legs dangling, eyes heavy with drowsiness. Jimmy, age ten and as bright as a child should be, was a normal boy. But it was Rudolph Hall's opinion that little boys in general should be held in a world apart from grownups. Preferably a world of iron bars and razor straps. Rudolph Hall hated little boys.

Charlotte Grande, his ex-wife, was the principal target for Rudolph Hall's hatred. The reason was simple. Until today, Charlotte Grande had been Charlotte Hall, wife of Rudolph. Their divorce was final but their arguments were everlasting.

Hall completed his little visual trip from person to person, stared at Sylvia again until he was sure that she objected, then listened in on the conversation that five minutes before he had chosen to ignore.

Hall himself was of the smooth-haired, greasy-skinned type, generally classified as doubtful on any girl's matrimonial list. Still, there was that quality of polish that assured him of a steady position as Plastics, Inc. South American representative. The polish helped, but the deciding factor was his ability to speak Spanish fluently.

"But I still say there is no immediate cause for worry over J. Manning," Freida Steele was saying. Freida Steele never saw cause for worry over anything but her stomach and the personal fortune in the Steele strong-box. "After all, he's a full grown man. He knows the Matto Grosso country better than any of us."

Freida had never been out of Chicago.

Hall smiled slightly and his upper lip curled. From the corner of his eyes he saw that Sylvia Clark, J. Manning's daughter, had heard enough of the inane conversation. He stood up abruptly.

"Isn't it about time we stopped discussing the possibility that J. Manning may be in trouble?" He noticed that Sylvia flashed a grateful smile in his direction. "J. Manning Clark is president of Plastics, Inc. If he says the fibres found in the Matto Grosso section are suitable for our purpose, he knows what he's talking about. He's also old enough to take care of himself down there. I predict that we'll hear from him in a few days."

A nice speech, he thought. The others stared at him with a begrudging respect. Steele and his little family depended on J. Manning. Sylvia was naturally worried about her father. Charlotte, damn her, was interested in anything or anyone who would continue dishing out money for her support.

Charlotte thought it time to offer an opinion. "Just the same, I'll feel safer when Art gets back."

HALL felt the hair on the back of his neck bristle. He shot a quick glance at Sylvia. She was smiling softly. The smile disappeared almost at once. Hall wasn't sure of Charlotte. He had expected his ex-wife would pull out of the Plastic setup for parts unknown. Her friendship with Sylvia had presented ample ground for her presence here this evening. J. Manning's home was always more or less open house, for that matter. Now Hall wasn't so sure of himself.

So the little devil was anxious for Art McFarland to return. Was that the way the wind blew?

Hall stared at Charlotte a little dreamily. She had the chassis, the pouting lips and the heavy blue-black hair that hooked men neatly and securely.

"I, for one, am going to head for home." Hall tried to sound sleepy, disinterested. "I need sleep and I think our charming hostess does, also."

"Oh, no!" Sylvia sprang to her feet. "You mustn't hurry."

Her voice, tired and with no ring of sincerity in it, prompted them all to rise. Jimmy Steele climbed off the desk.

"Ain't we gonna go look for Mr. Clark, Dad?"

Jimmy didn't seem to realize that J. Manning Clark was lost somewhere a thousand miles from civilization in the jungle country of Brazil. To Jimmy, the Matto Grosso was a romantic, meaningless name that you found in a book of maps. Jimmy had a yen for adventure.

Mrs. Steele thought an apology was due for Jimmy's ignorance. She offered it in a loud voice while Howard Steele and Rudolph Hall went for the coats.

"Jimmy's so smart for a boy of his age." She stopped to catch her breath and to push her voice to a higher level. "I do hope that J. Manning is safe."

"Aw, Mom!" Jimmy tried desperately to get her attention. "Cut out the gushing. You know what Pa says?"

Charlotte Grande saved the situation by swaying across the room with a nice movement of her lips, placing a finger under Jimmy's chin, and planting a lush kiss on his mouth.

"Nice boys should be seen and not heard—much," she said in a tinkling voice. "There's a kiss for you, Jimmy. Some men don't appreciate my kisses."

Jimmy wiped the heavy application of lipstick away with a motion of disgust and turned away, while Rudolph Hall felt himself redden under the fiery look his ex-wife was flashing at him.

Through the whole performance, Howard Steele and Sylvia Clark had remained in a world apart. A little worried, bewildered world that they shared together. Somehow the group found its way to the door. Howard Steele remained behind, as his wife swept Jimmy outside. He twisted his derby in nervous fingers and tried to find the correct words.

"J.M. and I are in this together," he said at last. "Now, Sylvia, I'm in touch with the Brazilian government. Your Dad was safe arid well only last week. I am expecting another wire any minute, saying that he's reached the coast and is on his way home."

For the first time, the girl seemed on the verge of tears.

"But," she protested, "that wire. It said that the natives had returned alone. That Dad had wandered away and couldn't be found."

She started to cry softly, grasping the little man's arm. Howard Steele was deeply touched. He made a gesture to move away, then hesitated. His eyes lighted in a desperate attempt at a smile.

"Why," he said, as though the idea had just occurred to him, "there might even be a wire waiting for me at home this minute. I must hurry..."

"Howard...!"

His wife's voice, clear and demanding, came from the darkness beyond the porch. "Please hurry. Jimmy will catch cold."

She might as well have said: "That girl is too pretty for you to be left alone with."

Sylvia heard Jimmy's voice. "Oh, Mom, I ain't gonna catch nothing."

Then they were gone, all of them, and Sylvia Clark stood swaying in the open door. She wondered if, of that entire group of people, all dependent on her father for an income, Howard Steele was her only true friend.

ART McFARLAND had never been as happy as he was this morning. He had purposely kept his return a secret until now. The trip from Newfoundland had been swift, and his first glimpse of home was a real thrill. The plane trip to Chicago brought back a wealth of old memories, and the family mansion in Evanston had never seemed so big and comfortable before.

McFarland was an orphan and a bachelor. His father, a chemist, had died when the boy was twenty. His mother, a warm-hearted, quiet woman of fifty, followed her husband after a year of grieving. That seemed like a long time ago. McFarland had celebrated his thirtieth birthday at the trading post on Frobisher Bay.

He added ice to a half glass of ginger ale, poured in a jigger of Old Taylor and stirred the mixture slowly. With the glass in his hand, he walked into the den, sat down near the gun- case and stared dreamily out the window overlooking Lake Michigan.

Unable to enjoy the drink before he called Sylvia Clark, he went to the phone and dialed the Clark home.

"Oh! Art, I'm so glad," Sylvia gasped, when he had identified himself, "we hadn't expected you back so soon."

"Listen," McFarland said eagerly, after they had chatted for a few moments. "Round up the J. Manning Clark pensioners and come over this evening. We'll celebrate the return of the wandering Zombie."

"Art!" She sounded worried. "You —aren't sick now? The trip cured you?"

He chuckled.

"My heart has picked up speed until I've got too much blood. You should see me. I'm so tough I can eat an Eskimo raw."

Sylvia was worried about something. Some of the happiness was missing from her laughter.

"Art?"

"Uhuh? What's up?"

"It's Dad. He went down to the Matto Grosso a month ago. The natives took him into the back country looking for a new fibre he thinks the company can use. The natives returned and told a wild story about Dad being dead—killed by wild animals. That's all we can learn."

She broke off, and he realized she was trying hard not to cry.

"Don't you worry about J.M., kid," he said trying to make his words sound convincing. "He can take care of himself. We'll talk it all over, tonight. Maybe I'd better go down myself."

"Art! Would you?"

She sounded relieved.

"We'll worry it out, tonight," he said. "Okay?"

It was. He hung up and returned to the den.

THE Steele clan arrived first. There was that period of gushings in which Freida Steele did everything but kiss McFarland, and Jimmy stood nearby, holding his father's hand and scowling at his mother.

"And we're so glad you've come back. It's so nice to have a man here when we're in trouble. You do look so devastatingly strong and healthy, Art."

McFarland managed to evade a continuation of the welcoming speech, shook hands warmly with Steele, and held Jimmy at arm's length for a complete examination. Jimmy wriggled a little but looked very proud. He had a lot of admiration for Art McFarland. Art could make any kind of a model airplane he wanted. Art could do darn near anything.

"Did you shoot any polar bears?" Jimmy demanded.

"I shot bears and seals," McFarland said. "And I've got a fish-spear in my trunk. It was carved out of whale-bone by a real Eskimo. I thought you'd like it."

"Hot dog!" Jimmy Steele's eyes were wide. "Where is it?"

"How silly!" his mother interposed. "Art, you couldn't give the child a spear."

Sylvia Clark came in, then, with Charlotte, Rudolph Hall between them. Charlotte studied Art McFarland with warm, mist- filled eyes. Hall stepped forward with outstretched arms. He managed a smile, but it didn't fool any of them.

"The hero returns," he said. McFarland took the hand. It reminded him of a frozen fish he had tried to eat in Karau's igloo and he let go of it quickly.

"Not quite a hero," he said, with an easy laugh, "but I do feel a lot stronger."

Sylvia was watching him from the background and it made McFarland nervous when Charlotte stepped toward him quickly, clasped his hands in her own and drew him close to her.

"Art," she said throatily, "Rudolph, the old villain, has just given me a divorce. I'm so glad you're home. I was on the verge of being all alone again."

McFarland wasn't surprised. He knew what Charlotte was after. But at this moment his eyes and thoughts were on the lovely girl framed in the dark doorway behind Charlotte. He had never dared to kiss Sylvia before. Perhaps the very fact that she was J. Manning's daughter had placed them worlds apart.

He broke away from Charlotte almost roughly and moved toward the door. The girl was waiting, her face tipped upward, arms at her sides.

"Sylvia—I've missed you...!"

He knew that the others were turning, watching.

"Hello, Art. It's good to see you again."

His arms swept around her and their lips met. A stray curl of soft yellow hair fell across her face and brushed against his nose.

She broke away, but he knew she wasn't entirely displeased.

"Art! Please!"

Her face was crimson. McFarland turned toward the others, linking Sylvia's fingers in his own. Freida Steele was staring at them, her lips parted with surprise. Charlotte's cheeks were burning red. There was a smile on Rudolph Hall's lips. A tight, sardonic smile. His chance would come later. For the moment, the look of hatred on Charlotte's face was enough to satisfy him.

Sylvia forced her fingers from McFarland's then, but he was sure that she returned the pressure slightly before she did so.

"I think that, after Mr. McFarland's impulsive gesture, I'd better replace some of my makeup."

She moved away rather hurriedly. After a moment of hesitation, Freida Steele took Charlotte's arm.

"If you intend to be selfish with your kisses, Art," she said coyly, "there's no reason why we should wait here."

Together, they followed Sylvia.

ART McFARLAND recognized in himself a strength he had not had before that trip north. His father had left a fortune and a huge estate to him. A wizard in research and in the development of new products, he had taken advantage of his father's name to make a lasting friendship with J. Manning Clark. Hence his work for the laboratories of Plastics Inc. McFarland had been drinking too much. His night life got the better of him. The trip to Frobisher Bay resulted.

Before that trip he hadn't been sure of anything. Now, with the touch of Sylvia's kiss still warm on his lips, he was sure, at least, that he was in love.

McFarland didn't like servants around. Now he prepared drinks and passed them to Steele and Hall. He poured a special glass of ginger-ale for Jimmy Steele.

McFarland wanted to know more about J. Manning's disappearance, but thus far no one had offered to bring up the subject. He realized that Hall didn't give a damn what happened to the boss, so long as the money continued to roll in. Howard Steele sat alone, answering questions politely, but refusing to mention J. Manning. McFarland knew that for some reason, Hall resented him. Probably because Charlotte had made a play for him when she came in. McFarland wasn't fooled by the divorce. There was jealousy in Hall's eyes every time he looked at his ex- wife.

"I hadn't heard anything about you and Charlotte, Rudolph," he said casually.

Hall laughed nervously.

"You haven't heard about any of us since you went up there and loafed on a glacier for a year."

McFarland chuckled, but he knew there was something behind Hall's remark that wasn't pleasant. He sent Jimmy Steele for some more ice, pocketed an extra bottle opener and sat down comfortably in his favorite chair. He sipped at his drink slowly, studying Hall.

"I'd have thought you and Charlotte would have skipped town for a while. Don't you find it pretty tough going to the same places? Sort of hanging out the old sign 'business as usual'."

Hall's face turned a faint pink.

"Charlotte does what she wants to," he said with a trace of bitterness. "As for me, this is where I do my business."

McFarland thought of Sylvia Clark.

"That business wouldn't point toward Sylvia, would it? She needs someone with her father away."

Hall stood up abruptly, placing his glass on the table.

"That," he said, "is none of your damned business."

McFarland didn't move, but his fingers tightened around his glass.

"Your opinion," he said with a nod. "Mine differs. I figured you out as a two-bit fortune hunter from the first day I met you. You thought Charlotte had dough and you married her for it. You're really in love with her now, at least to the extent that you burn up when anyone else gets within six feet of her. That divorce business was for a reason. Sylvia Clark has money and you stand ace-high with J. Manning. Do I make myself clear?"

A sneer twisted Hall's lips.

"So clear that you make yourself look like a jealous boy," he snarled. "Pardon me if I make your party slightly smaller by leaving."

He went toward the door swiftly, but there was a stiffness to the set of his shoulders that betrayed the brave front he had been showing. Hall had planned on a clear field, with McFarland out of the way. He didn't enjoy the present outlook.

"WHERE is Rudolph?" Freida Steele asked. The same question was mirrored on the faces of the other women. "Surely he didn't leave?"

Charlotte Grande giggled hysterically.

"The same old Art," she said walking toward McFarland swiftly. He didn't move as she sat down easily on the arm of his chair. "Rudolph is a fool, isn't he?"

McFarland didn't answer. He was looking into Sylvia's eyes. They were filled with cold, unexplainable anger.

Barely ten minutes ago the girl had returned his kiss with a tenderness that surprised him. Now, she was angry. He wondered if Rudolph Hall's sudden departure had something to do with her attitude.

"Hall had to leave," he said. "Does that break up the party? I've been waiting for someone to tell me about J. M. I don't believe he's in trouble. J. Manning just doesn't allow trouble to stop at the same hotel with him."

They all started talking at once. That is, all except Sylvia. She sat quietly and listened.

The strain had been great. Now that he had asked for it, every person in the room was leaning on him for support. Howard Steele told the story. He knew no more about it than McFarland already had heard. The Brazilian Consulate hadn't been able to get an intelligent account of what had happened.

"I'm waiting for a full confirmation by letter," Steele said. "I'm afraid there's nothing we can do, at least for the present."

McFarland hesitated.

"Then why worry?" he said finally. "J. Manning would give us the devil if he knew we were crying over him. J.M.'s not a tenderfoot. Animals don't kill him. He kills them."

They all managed a smile at that and McFarland was quick to switch to some other line of thought.

"Jimmy!" Jimmy Steele's head jerked erect. He had been dozing. "Run upstairs and bring down a little box you'll find on my bed. I've got something to show you."

While the boy was gone, he told the story of the Eskimo, Karau, and the rattling marbles.

"Karau taught me how to tell a fortune with them," he said as Jimmy returned. "I'd like to try my skill."

He was using every trick he knew to entice Sylvia Clark into the circle. She was angry at him. Angry about something, probably Hall. To hell with Hall.

Jimmy put the box down carefully on McFarland's knee. Steele and his wife drew their chairs close. Jimmy stood at McFarland's elbow, Sylvia came over and stood stiffly behind Howard Steele.

McFARLAND took out a dozen of the little marbles. They felt slightly pliable in his hands. He shook them quickly, tossed them on the floor, and started a little white lie about Jimmy Steele and his future.

"The marbles say you're going to be a pilot, Jimmy," he said seriously "I guess that one over there must mean that you're going to be so good you'll be away ahead of the rest of the pilots. That's why that one marble is alone." They were all serious, and Sylvia managed a little smile.

Jimmy looked awed.

"Did you learn all that up north, Art?"

McFarland picked up the marbles. "Sure did," he said. "And now let's try your Pop." Jimmy snorted.

"Pop ain't got no future," he said. "Pop's old."

Every one but Freida Steele laughed at that, and she gave Jimmy a lecture on respect for his parents.

One fortune-telling suggested another. Charlotte was going to find a new husband, a handsome one, to which she answered lightly:

"Art, I've always loved you."

McFarland didn't have the heart to throw the marbles again. He put them back into the box.

"Sorry I can't offer you anything to eat. Haven't found a cook yet."

"You don't need a cook," Jimmy said. "Why don't you marry Sylvia?"

"I wonder if Sylvia can cook," Charlotte asked with venom in her voice.

"I wonder if you can be nice long enough to eat at Cooley's Cupboard with us?" McFarland said abruptly. "I'm going to see that you are all well fed before I let you go home."

They all moved to the hall, and McFarland put the box of rattling-marbles on the open window sill.

It might have been Freida Steele's coat that knocked the box off. She put the coat on with a great show of gusto, sweeping close to the window as she did so. The box tipped over. The rattling-marbles rolled out and fell into the soft soil outside.

McFarland remembered the box a few days later. When, out of idle curiosity, he looked for the marbles, they were gone. The rain had driven them into the soft dirt.

They hadn't been much of a success anyhow. He hadn't spoken to Sylvia Clark since the night of that unpleasant party.

Perhaps he should have paid more attention to the rattling- marbles. He wondered about that later, when it was too late.

THE plants were tall and covered with long, almost transparent leaves. They grew, a dozen of them, among other varieties common to all gardens.

Hanging from the end of each stem was a small, dark ball. The balls looked like the rattling-marbles, but were much larger. In all, there were over fifty of the black balls, each of them approximately nine inches in diameter.

The seeds that started them had been spilled carelessly from a box on the window ledge. Seeds from a lonely Eskimo hut at Frobisher Bay, and before that, from the icy heart of a glacier.

It was close to midnight, the second week after Arthur McFarland had quarreled with Rudolph Hall.

A steady breeze blew off Lake Michigan, disturbing the hedge and rocking the little spheroids rhythmically. One of them finally dropped from its stem and settled slowly down to the earth. That was the signal for the awakening. As though by prearranged signal, the others also drifted downward to the ground.

A small door opened at the side of the first spheroid. Opened inward, leaving a mysterious cavity.

Then, more startling than anything that had happened thus far, a tiny man stepped over the open sill of the door and jumped to the earth. He was an old man, hardly more than five inches tall, clothed from head to foot in a green robe. There wasn't an inch of him that wasn't green. Pale, dainty emerald feathers sprouted from his back and hung downward. He carried a staff that was taller than himself, holding it like a badge of authority.

For a time he stood alone, cut off from the world by the hedge that was a dozen times higher than himself, and by the house that must have been too vast for him to understand.

Then he turned toward the opened spheroid and motioned with his arm. This was the signal for the other doors to become suddenly filled with small, emerald bowmen, all falling over each other in their eagerness to reach open air. They looked as though each had been turned out of the same mold. Each was the size of his leader. However, their clothing was different. The first to alight had been old, almost monkish in appearance. These were husky warriors, dressed in green to match the texture of their flesh. Their clothing was skin tight. They wore pointed shoes, feathered hats, and carried bows that were as tall as themselves. A pair of transparent feathers sprouted from between the shoulder blades of each and hung down to the calf of his legs. The feathers resembled the leaves that grew on the strange plants above the heads of the little men.

In a twinkling, the warriors had formed in a tight group about the old man. Their language would have sounded high-pitched and very strange to anyone but themselves.

The old man held his staff aloft for silence. "What awesome world is this in which the plant men have come?"

HIS followers stared up at the house and, in the opposite direction, at the hopeless tangle of the hedge. They shook their heads.

"The leadership of the plant men falls on my shoulders." The old man fluttered his wings slightly, as though very proud indeed of his splendid heritage. "It is so long since the last seeds have germinated that we have much to plan and accomplish. However, I am the only leader who came from the crop. I am complete master."

More nodding heads. The leader was announcing his policy. The plant men waited.

"It has evidently been many years since the grave-of- ice. Through some good fortune, we have come again to our country. One thing is fearful indeed. It would seem that a race of giants has come into power. We must proceed cautiously, learning as speedily as we can. When the seeds are ripe, they will be planted again. There is work to be done. Scouts must determine just how extensive the battle will be."

Among his followers, the leader was a powerful man. A man with a voice that demanded respect.

Without further instructions, a half dozen warriors leaped into the air, spread their wings and flew above the hedge. They looked like small birds, the moonlight reflecting in their green wings as they circled higher and higher into the air.

A huge square of light flashed out into the darkness from the side of the great cliff above the plant men. One of the scouts, more daring than the others, flew upward toward this light. He saw that it came from an opening in the wall of the cliff, and was produced by a transparent tube as large as himself that hung from the top of a square room behind the opening.

As there was nothing to alarm him for the present, the scout dropped gently onto the window-sill of Jimmy Steele's room and looked around with sparkling, green eyes. This was indeed a great and fascinating place. He had never seen anything like the room. A huge, four-posted thing was in one corner. Lying across it, covered by a snowy white cloth, was a giant. At least the creature had the appearance of a giant, although his eyes and his expression were very gentle. The giant was studying a book. The scout remembered the books of law that the plant men had used years ago. This, however, was many times larger.

The scout was very excited by the discovery. He sprang away from the window and dropped gently back into the garden. He was the last to return. The others had gone only to the hedge top and had long since returned to report to the leader.

The scout was terribly keyed up over what he had found. He had trouble in making his voice sound official and disinterested.

"I have to report that we are born again in the midst of a land of giants. That I have seen one of them and he is much larger than we. Our battle to overcome him will be great."

The leader's splendid green face seemed to pale slightly, but he remained unshaken. This could not be true. No finer, taller men grew in all the world than his own ancestors.

"We shall see this for ourselves," he said. "Two of our plastas* will enter the giant's dwelling. We must learn just how powerful the giant is."

[* The spheroid balls in which these men were born. Each plasta held six men. These six plant men formed a permanent crew for their own plasta. —Ed.]

JIMMY STEELE liked Robin Hood. He thought Robin Hood was about the nicest guy in history. Jimmy's mind never bothered to unscramble the rather questionable lives of men like Robin Hood and Paul Bunyan. They were as much alive to him as were Columbus and Buffalo Bill.

Robin Hood was a "right guy" and Jimmy Steele thought there was a lot of Robin Hood in Art McFarland. Of course, Art didn't carry a bow and arrows, but Art had brought a fish-spear all the way from the North Pole, almost, and that was just as good.

Jimmy believed in fairies all right. There wasn't any doubt about that. When he was reading Robin Hood in bed, and the fairies came floating through the open window in two little black balls, and stepped out on the table by his bed, his eyes might have grown a little round and excited, but he didn't become alarmed.

It was well that he didn't. Jimmy was flirting with death in the form of tiny arrows.

He was thrilled by the little group of perfect Robin Hoods that climbed out of the black balls, and stood stiff and alert, staring up at him. Jimmy knew Robin Hood didn't have wings, but fairies always did, so that made it even.

He couldn't help smiling at the wiz-zen-faced little old man who advanced stiffly across the table until he was close to Jimmy's face. Jimmy thought he looked like Friar Tuck, with green parrot feathers hanging down his back.

The little man held up his arm, and his fingers just reached the rim of the water glass on the table. The other fairies, all of them alike, drew little arrows from their quivers and placed them loosely in their bows. They stood in a determined group behind their leader.

Jimmy didn't know just how you got along with fairies.

"Hello," he said, and smiled at them so they wouldn't run away.

They didn't, although afterward the leader admitted that it was a bad moment. He hadn't expected such a blast of sound. He put finger-tips to his ears and shook his head violently.

Jimmy caught the hint.

"Hello," he said again, this time almost in a whisper.

The leader bowed at the waist, evidently working on the theory that if worse came to worse, he could always get tough when it was necessary. He started to talk swiftly, asking questions that were nothing but a mass of question marks as far as Jimmy was concerned. The tiny, high-pitched voice meant nothing to him. He turned the water-glass over, picked up the little man with the staff and sat him down on top of the glass.

FORTUNATELY for Jimmy, he did it quickly, and the leader was safe again in a moment. Had that moment lasted long enough for him to cry out in fright, the bowmen would have released a flight of arrows.

As it was, the leader moved uneasily on top of the glass. From this point of vantage he could easily see the pages of Jimmy's book. He spent several minutes studying it.

While he was thus occupied, Jimmy lay very still, watching his guests.

"Can you read?" he asked the leader.

The leader didn't understand the words. He shook his head—first yes, then no. That would take care of everything.

The leader was very worried. He couldn't even reason with the giant. The words on the page were foreign to him. He had never seen such marks before. This created a problem. He spoke to his followers, keeping all the dignity that such a position would allow.

"The giant will not harm us for the present. He is entertained. We must gain his friendship if possible. Throw down your bows."

And while Jimmy watched with interest, the leader studied the page of Robin Hood.

He finally decided that he could not read it, regardless of how he tried. He became angry. He and his men were intelligent. Before the death-of-ice swept them from earth, his plant men had been the ruling race. Now they were replaced by giants—but wait? Were these giants? The one on the bed seemed to have the mind of a child.

He must be a child giant.

The leader shivered. Imagine, then, the size and the power of the matured giants I Only one plan of action suggested itself to the leader.

He must work slowly. No point of reproducing the plant man race until he was ready for them. The little group would have to learn to determine what battles they were to fight. Then, equipped with information about these giants, they could reclaim what had been theirs before the death-of-ice came.

The little giant on the bed was friendly. He must, in some way, be sworn to secrecy. They would learn his language. It would be of great value.

The leader took a deep breath, fluttered to the table top, and ordered his warriors back into their plastas. This move would tell the boy-giant they were leaving. Then the leader approached the huge head that leaned over the table top.

The leader motioned toward the window with his arm. Then he smiled in a friendly manner. He made several motions toward the window and back, trying to tell the boy-giant that they would go, and come again. Jimmy got the idea. The fairies were going away but they would come back.

Then the old man held his finger to his pursed lips. It was a sign that no one could possibly misunderstand.

Jimmy shook his head delightedly.

He put his fingers to his own lips.

"I won't tell anyone," he promised. "Not anyone."

"Not anyone," the leader repeated in a thin voice. Already he could speak the language, although he didn't understand it.

He bowed once more, thinking it good manners, and moved toward the plasta. At the door, he turned once more and placed his finger to his lips. Jimmy repeated the process, and waved his hand.

"Goodbye," he said.

The leader smiled.

"Good bye." He made two words of it.

When he closed the door of the plasta, the leader was well satisfied. He had already learned the proper word to use when departing from the company of the giants. He repeated it over and over as the plasta floated from the window and sank down behind the hedge.

Jimmy Steele lay awake for a long time that night. Robin Hood was on the table, neglected and forgotten. Jimmy Steele had a date with some real fairies. That was better than Robin Hood and Buffalo Bill put together.

ART McFARLAND wasn't satisfied with the setup, but he didn't know any other way of keeping Sylvia Clark busy while he was in Brazil. She needed company. The J. Manning Clark mansion on Lake Shore Drive was a lonely place. But McFarland couldn't ask the girl to stay alone at the Evenston place.

McFarland didn't especially like Charlotte Grande. The girl was after him, or any reasonable facsimile. Still, she was good company for Sylvia.

The two girls managed to get along well enough. Tennis, golf and a love for the outdoors gave them a common bond.

McFarland invited the entire group to the Evanston house for the summer. There was more room than he knew what to do with. Freida Steele was so pleased to get out of the cramped apartment on West Madison that she overrode any objection her husband might have. Jimmy, after his first meeting with the fairies, didn't think there was a house in the world as nice as Art's.

Sylvia decided to come, as long as there would be others about for company, and Art McFarland made plans to leave for the Matto Grosso as soon as his passports and transportation could be arranged.

Three weeks after he returned from Frobisher Bay, McFarland was ready to leave to search for J. Manning Clark.

IT was Friday evening. The others had arrived with their baggage. Quiet Howard Steele was last. He came in a cab, with odds and ends that Freida must have if life were to be at all livable. However, he came with news that changed Art McFarland's entire summer—perhaps his entire life.

Steele rang the front door bell excitedly and barged in before any of them could open the door for him. They were gathered in the hall, greeting Charlotte Grande and her ten pieces of luggage. When Charlotte moved, she went all out on the project.

Steele waved a sheet of paper that bore the unmistakable letterhead of the Brazilian Consulate.

"It's J. M." Steele's voice was hysterical with relief. "He wired Washington that he is safe. His business demands that no one contact him until he advises us."

Art McFarland took the letter and read aloud:

Dear Mr. Steele:

I promised to advise you as soon as I heard from your partner, J. Manning Clark. As Clark and I are also old friends, I am writing personally.

A wire reached me today. He refused to contact you direct for reasons that I cannot now divulge. However, I assure you that there is nothing to worry about. He has discovered certain materials that may revolutionize your business. J. Manning Clark will contact you at the proper time. Meanwhile, accept my word that he is safe and that I will let you have further news.

Respectfully,

Ramando Quartez,

Office of the Brazilian Consul,

Washington, D.C.

McFARLAND passed the letter to Sylvia, who read it over to herself. There were tears of relief in her eyes. No one spoke for a full minute, then the room was filled with eager voices.

"He had no right to worry us so," Freida Steele protested.

"J. M. has a right to do what he damn well pleases," Charlotte Grande said softly. She went to the divan, lighted a cigarette and sat down carefully, making sure a proper amount of silk clad knee was visible to her public.

McFarland sighed.

"Well, looks as though I stay home after all," he said. "That's about the most welcome postponement I've ever made."

Sylvia folded the letter and passed it back to Steele.

The little man was quite overcome by it all. He wiped an impatient hand across his eyes, and his fingers were shaking.

"I'm—I'm happy," he said. "For Sylvia's sake."

Sylvia smiled. The odd, half-fearful expression was gone. Her face had color once more.

For that matter, McFarland thought Sylvia was tops tonight in a number of ways. There was no comparison between Charlotte's tight fitting dress and the creation that Sylvia had been poured into. Her shoulders were tanned. The silken hair had been combed out to full length, and the pale-blue silk evening gown with a wide skirt that swept the floor, brought out every dimple and curve as though they had been carved from pure ivory.

Sylvia could look lovely without being aware of it. She did everything simply and without pretense. Now she was staring up at McFarland, eyes brimming.

"Thanks for wanting to help, Art. I suppose we can all go home now and let you rest."

He chuckled.

"I had to fight to get you here," he said. "You certainly wouldn't walk out, now, just because I'm staying at home! There's room for everyone. Let's make it a party until we hear from J. M. The old joint needs some life in it."

"You're so sweet!" Freida Steele had already made up her mind to stay.

Charlotte arose and swayed across the floor to Sylvia's side. She took her arm and, in a voice dripping with honey, said:

"Come on, Syl, let's get settled. I'm waiting to get a crack at you on those tennis courts."

"She's waiting to get a crack at her, all right," McFarland thought grimly.

The evening might have ended in a dull game of bridge if Jimmy Steele hadn't gone to his room at that time. Jimmy had been staying with Art McFarland for two weeks. Tonight Jimmy had another date with the fairies.

Howard Steele was explaining that the Matto Grosso jungle had a lot of valuable timber and fiber hidden in its remote vastness. He was wondering aloud if J. M. had found a good substitute for wood-pulp plastic.

Charlotte had flashed her nicest smile at McFarland, and McFarland was mentally tearing Hall apart limb for limb because he couldn't beg a smile from Sylvia.

THE scream was full of fear and terrible pain. It was Jimmy's voice, rising to a high-pitched cry of terror.

Freida sprang to her feet.

"It's Jimmy!"

McFarland reached the hall and took the steps three at a time. He threw open the door at the end of the hall and saw Jimmy stretched out on the floor half-way between the door and the bed. The boy's face was cut and bleeding. His eyes were closed and as McFarland scooped him up in his arms, he felt Jimmy's body grow tense.

"Art, look out for the green fairies!"

He had to push his way through the others to get Jimmy downstairs and across the lounge to the divan. He sent Freida for water, to keep her quiet. They bathed Jimmy's forehead and washed the dozens of tiny wounds on his face.

When Jimmy opened his eyes, there were a lot of familiar faces close to his. His mother was crying and Art McFarland had a puzzled, angry expression on his face.

Jimmy didn't dare to tell that the green fairies had suddenly started shooting arrows at him.

Art might believe him, but Jimmy didn't dare tell Art.

McFarland went outside, after that. He had a little thinking to do. Jimmy watched him as he left the room, and wondered just how much McFarland had guessed. Maybe if he were alone with Art, he'd dare to tell him. He'd have to tell someone, or the fairies might try to kill him again.

McFARLAND wandered across the moonlit lawn. He was puzzling over what had caused those scratches on Jimmy Steele's face. Jimmy wouldn't talk. That might mean that a favorite cat had crawled into Jimmy's bedroom and scratched him. Jimmy would be afraid that the cat might be punished.

That explanation didn't satisfy McFarland.

"Art, look out for the green fairies!"

There was a bizarre, almost frightening meaning in the boy's words. Jimmy had a healthy imagination, but Jimmy was almost out cold when he said that. McFarland's experience told him that people usually muttered truths when they were unable to control their lips.

He had come as far as the greenhouse, hesitated, then opened the door and went inside. The place was dark. He felt for the light-switch and snapped it on. He was surprised at what he saw.

Ben, the gardener, had been given a free hand. The place was about a hundred feet long, filled with tables of earth and flower pots. A fine collection of native plants and shrubs were in sight.

With Jimmy now occupying a very small place in his mind, McFarland walked toward the plants, admiring Ben's handwork. He reached the first group of palms before he heard a tiny voice call out:

"Stay where you are!"

McFarland stopped in his tracks, staring around with amazement. At first he could see no one. The voice, coming from somewhere below him, sounded like the piping of a tiny flute. Then, on the edge of a small flower pot, he saw a little man, hardly five inches tall. The little green fellow brandished a staff in the air that was taller than his own body. He was completely green, both in clothing and skin, and emerald wings fluttered about his shoulders.

McFarland realized that he was staring at one of Jimmy Steele's fairies. He was too fascinated to move or speak.

"We have tried to avoid contact with your kind until we were fully prepared," the little man shouted. "Now that you have discovered us, we must act."

He turned and shouted a command into the foliage on the plant table.

"Destroy, the giant! Release your arrows!"

Something hit McFarland in the neck. Swearing with pain, he reached up and drew out a small, dart-like arrow.

"Take it easy, will you?" he shouted. "You don't have to—"

Before he could protect himself, dozens of the darts buried themselves in his face and shoulders.

It wasn't funny, now. He looked for the little man who had shouted at him, but the leader was gone. Then, gradually, he could see the warriors who were shooting at him. They were like their leader, green in color, but dressed differently. They had scattered carefully among the plants, hiding behind the leaves.

McFarland felt as though he had walked straight into a hornet's nest.

He staggered back toward the door, protecting his eyes with his hands. He managed to find the light-switch and plunged the entire place into darkness.

The army of plant men stopped firing at once.

McFARLAND, shaking his head like an angry bull, plunged through the door and fell headlong into the shrubbery outside. His hair was disheveled and his shirt was torn almost from his shoulders.

He managed to get to his feet, and stagger toward the house. Blood had run down his face and he could hardly see. He fumbled with the door knob and stumbled into the kitchen.

There was a sudden movement of pale blue color near the refrigerator. Sylvia had come to the kitchen for ice.

She saw McFarland standing there, wiping blood from his face with the back of his hand.

"Art! What happened?"

She was at his side, helping him to a chair by the table.

"I'm all right," he said grimly. The barbs were stinging his face and shoulders.

"But what happened. Where in heaven's name...?"

"I went for a walk," he said. Then a chuckle escaped his lips. "Guess I met some of Jimmy's fairies."

SINCE the first night that the plastas of the plant men fell from the ripened vines, they had made great strides toward their conquest of the world. In every growth of plant men there was a leader. The little man with the extra fine feathers who had been born with the robe and staff of knowledge, was the leader of the first growth. His name was Thorna, and he had been properly chosen by his warriors. Thorna ruled well. He led his people in the right direction, preparing for war against the giants.

A select group of warriors had learned, with Thorna, the language of the child-giant. They thought they had filled the child-giant with arrows, leaving him to die. The child-giant would have no opportunity to tell others what had happened.

But first, Thorna had become familiar with the language spoken by the giants.

To him also went credit for finding the Temple of Glass. Thorna discovered the Temple of Glass and was wise enough to realize that the warm, damp air made his people grow larger and stronger.

If the giant had not stumbled into the Temple of Glass, Thorna would have not attacked the giant-race so soon. Now, there was no choice. He must follow up quickly and claim the giant as prisoner.

Thorna stood in stately dignity on top of the flower-pot where he had directed the battle. The giant was gone, and the light that startled them into hiding, was gone also. Thorna spoke.

"The giants, we have seen, are not fighters."

A mighty cheer followed that ringing declaration.

"We will multiply speedily. We will find in the new plastas, a group of sub-leaders who will learn from me each day. I think that we are now ready to follow up our first victory and claim the weakened giant as our rightful prisoner."

Another cheer.

"We will, in a few weeks, have a complete legion of warriors. At present a few dozen will suffice to bring back the wounded enemy. May I have volunteers?"

Every plant man on the table stepped forward. Some of them, perched high among the plants, almost broke their necks getting down to the leader. Thorna held up his hand for silence.

"We will take fifteen plastas of men. The giant had retreated to his cliff. We will search for him there."

Secretly, Thorna was shaking in his boots. He had been frightened to death of the child-giant. He didn't want to tackle the giant's cliff alone, but he must, to keep his standing as leader.

Out of a broken glass near the end of the hot-house floated fifteen small plastas. They gained speed in the breeze, sailed upward toward the kitchen window and drifted silently through it. Thorna, in the first spheroid, guided it deftly to a huge round-topped landing field. Through the slitted eye piece of the plasta he saw something that took his breath away.

THE giant was here, but he was not alone. He was seated in a chair, bending over a huge table. Leaning close to him was a female giant, the most breath-taking person Thorna had ever seen. Even though her skin had none of the green pigment that was so attractive, Thorna recognized beauty when he saw it.

The girl-giant was plucking arrows from the giant's wounds. He sat patiently as she drew them out, and dabbed at the blood with a huge wad of white stuff.

The girl-giant had flesh of golden brown. Her body was moulded into the finest blue and white garment Thorna had ever seen.

Thorna stepped uncertainly from his plasta. His five personal warriors sprang out, taking positions behind him. To them, the giant's will was already broken, and he was ready for the kill Thorna did not fear the girl-giant. She would be weak.

The slight click of the plastas, as they hit the table startled Sylvia.

She turned around quickly, uttered a startled little cry and threw her arms about McFarland's neck. That was only for a moment. She drew away, blushing a little, still staring with wide, blue eyes and parted lips at the scene on the table.

This was the time to assert himself, Thorna thought. He stepped quickly to the edge of the table, raised both arms above his head and planted his feet solidly.

The last of the plastas had floated through the window, and a small body of bowmen were ready, bows strung.

Thorna's voice was very weak and thin, in spite of the bellow he attempted to send toward the pair of giants.

"You are a conquered people. We call upon you to surrender yourselves to us."

For a moment McFarland's face remained solemn. Then a smile curled his lips and he slapped his knee with his palm. A laugh shook his body.

"Well, I'll be blitzkrieged!" he howled. "Sylvia, did you hear that? Jimmy's fairies have conquered us!"

The girl said nothing. Her mind was in such a turmoil at that moment that she couldn't think clearly. The figures on the table were like living, green dolls.

McFarland leaned forward and picked up Thorna.

Thorna started to kick and shout as the big hand went around him. He managed to howl one command.

"Attack!"

A dozen arrows sped through the air toward the pair of giants. With an oath, McFarland dropped the leader to the table where the little feathered man flopped on his back, then managed to regain his feet and rush for the plasta. As he ran, he shouted wildly:

"Retreat. They are too powerful. We shall be killed."

The arrows still flew. McFarland, afraid that one of them would do serious harm to the girl, whipped the table cloth from the table. He held it between them and the bowmen. The other hand swooped out and captured the plasta in which Thorna had taken refuge.

THE battle was over. The bowmen were helpless, now that the heavy curtain hung between them and the giants. They might have flown over it and inflicted punishment, but the loss of their leader left them with no heart to fight on. There was a sudden rush for the plastas and a mass retreat out the window. Five bowmen remained. In a small circle, back to back, they waited with drawn bows. They were the personal bowmen of Thorna, and to leave now would bring certain death to them from their own people.

The plasta was in McFarland's hand. He lowered the table-cloth slowly. Before him were the five tiny plant men, shaking in their green boots, waiting for the final swoop of that terrible hand that would mean death to them all.

McFarland pulled out a thorn that had penetrated his wrist and started to laugh.

"I think," he said, "that you'd better lock the kitchen door. We'd better stay alone until we convince ourselves that we're still sane."

Sylvia stood up and walked to the door as though she were in a dream. She slipped the bolt into place and returned. She stood by the table, staring down at the group of warriors.

"They're afraid of us, Art. The poor little darlings."

McFarland was busy. He managed to pry open the door of the plasta which he still held in his hand. He reached in with two fingers and drew out Thorna. Thorna fought and kicked and scratched but it was useless. McFarland placed him gently on the table and the leader sank to his knees.

"We plead for mercy!" His tiny voice shook. "What would you do with the body of such as I. I am an old man and of no value."

Sylvia forgot the warriors for the moment.

"Art," her voice was pleading, "we aren't crazy, are we? This is really happening?"

He pointed to the plant man.

"He sure takes it seriously enough," he said.

Sylvia picked up Thorna. She placed him in the palm of her hand and stroked his wings.

"Don't be frightened," she said softly. "We won't harm you."

Thorna's heart did a flip-flop. So, after all, he was not such an old man. He had charmed the mighty giantess. He sank to his knees on the soft palm of her hand.

"I thank you, mighty giantess. And now, may we go?"

"No," McFarland said. Thorna started to shiver.

"We meant no harm to the white giant."

"You meant to kill me," McFarland reminded him, "and it's no fault of yours that you didn't. Why did you attack the boy?"

"Please, Art," Sylvia said. "Let the little fellow go."

McFarland felt his bleeding shoulder.

"Nothing doing! I can't let my guests wander around here and have these—these midget Robin Hoods bump them off. How does it sound? Arthur McFarland arrested for allowing fairy warriors to murder his guests!"

Sylvia laughed.

"A little silly," she said. "And remember, this little man said himself that you and I are a conquered people. Please, Art, I'll make him promise not to harm us."

McFarland winced.

"Okay," he said.

"You'll promise to be good?" he heard Sylvia ask.

He stood up and went to the door.

"I'm going to take a bath, and see if I can lose the sting of these cuts with a couple of highballs."

Sylvia hadn't heard him. She was placing the little man carefully in the little round ball. McFarland went into the hall, slamming the kitchen door behind him.

Sylvia Clark didn't realize, as she watched the last plasta float out the kitchen window, that she had opened negotiations for an enterprise greater than J. Manning Clark could ever have hoped to achieve. Nor did she know that the leader, Thorna, had gained the confidence of his people, and fallen madly in love with a woman giant.

Thorna's whole being was shaken by her beauty, and the mighty, tender voice. He couldn't blame the man-giant for being angry, but from now on the man-giant was safe. He could thank the lovely giantress in blue and white for that.

IT was an awe-stricken, frightened Thorna who crept silently from the Temple of Glass and flew alone above the hedge to the cliff. He saw the light that burned above him, flew upward quickly, and landed on the window-sill. This was not the giantess's room. Another giantess occupied it. She was dark- skinned and attractive, stretched across her bed in a red robe.

Thorna stared with admiration at the new giantess, then slipped from the sill and flew along the cliff wall to the next lighted window. He flew inside, recognizing at once, the soft blue dress that lay across the chair near the bed.

The giantess was asleep. Her head was buried in a pillow. Long, golden hair curled in all directions over the white cloth. Thorna dropped softly to the pillow near her head. Sylvia Clark's eyes opened slightly, then widened. A smile moved her lips.

"Hello, little man," she said. "Am I dreaming again?"

Thorna sat down, cross-legged on the pillow.

"Would the giantess listen if Thorna asked her some important questions?"

He was very serious.

She nodded and the movement almost threw him from the pillow. He regained his balance.

"Where did you come from?" Sylvia asked.

"From the Palace of Glass," he said. Sylvia looked puzzled. "That's a pretty name. Where is it?"

Thorna pointed out the window.

"Only a short way," he said. "It belongs, I think, to the giant we attacked."

Sylvia thought she understood. The little winged man must have come from Art's greenhouse.

"But I mean, where did you come from in the first place?"

Thorna had come to ask questions, not answer them, but if the giantess wanted to know about the plant men, he would be proud to tell her.

"It is a long story. You will tell no one?"

"No one."

"Once," Thorna said with a mournful sigh, "we were the only people on earth. The animal kingdom did not trouble us. The world was hot and wet. We flourished, and were the ruling race. No more powerful warriors were there than the plant men. At last the death-of-ice came."

"The death-of-ice? I don't understand."

Thorna took a deep breath.

"The death-of-ice was a huge ice-sheet that moved over the land. It dug great valleys and made high mountains. It slowly buried our homes and our families."

Could he mean the glacial age, Sylvia wondered?

"Fortunately," Thorna went on, "we, the plant men, are reproduced by plants. The plant grows quickly, the plastas are formed and in each plasta there are six men."

His chest swelled slightly.

"I am the leader."

"But, if the death-of-ice destroyed you all, how...?"

"HOW are we here now? We know not. Some of the seeds of our civilization were scooped up and frozen by the death-of-ice. Somehow those seeds found their way to warm earth, and grew. They would not grow in a cold climate."

Sylvia Clark was beginning to understand. As wild as it might sound, she knew that Art McFarland's "rattling marbles" had produced these men. She remembered hearing McFarland say that they had fallen out the window, and were buried in the dirt.

"That's a very interesting story," she told Thorna.

Thorna glowed.

"And now—if I may ask the giantess a question—where did the giants like yourself come from?"

Sylvia smiled, picked him up, and placed him closer to her ear.

"I'm not really big," she said. "All people on earth are as large as I."

She saw Thorna's face turn a very pale green. He shivered violently.

"All—as large as you?"

She nodded.

"Millions of us," she said. "Of course, I suppose we seem very large to you."

Thorna gulped.

"Very large," he agreed. Then, anxiously, "But, before the death-of-ice came, we were as large as any one."

Sylvia chuckled.

"It must have been a small world," she said.

Thorna managed a doubtful smile.

"As leader of my people, I had planned to conquer all of you. I suppose it would be impossible?"

The question was very humble. Sylvia nodded her head.

"Any more questions?" she asked.

He shook his head.

"I thought perhaps our small size might be caused by the cold air. We seem to grow many inches taller in the warmth of the Palace of Glass. Are there warmer lands?"

"Yes," she said. "Many lands are warmer. My father is in a land now that grows tropical plants like those in your Palace of Glass. The heat there is almost too much for us to bear."

"And the moisture? It is a damp land?"

"Yes."

Thorna was eager. "It is far away?"

"Farther than you could go in a long, long time, because of your size," Sylvia assured him.

Thorna was crestfallen.

"It isn't fair," he said. "Once we were all-powerful. Now you have taken our world and we are midgets. We do 4 not deserve such a fate."

Sylvia was touched. The little men didn't really mean any harm.

"Do you think," she asked eagerly, "that if you were in a warm land, you would grow?"

He nodded his head fiercely. Then he frowned.

"But such dreams are impossible."

"I am not sure that they are. Could you survive if you all stayed in your plastas for many days?"

"Yes."

Sylvia was satisfied.

"Then it's all settled," she said. "Tomorrow I'm shipping a large package by air-express to the Matto Grosso. When you feel the warmth and moisture that you need, break out of the package, and you will be in the warm land."

Thorna did not know what she planned to do, nor did he fully understand the meaning of all the words she used, but he trusted the giantess.

"I don't know how to thank you."

"Never mind," she said. "Have your entire army in my room, tomorrow night. I'll take care of..."

"Help!"

A HIGH pitched scream of terror interrupted her in mid- sentence. It seemed to come from one of the rooms down the hall. Sylvia sprang from her bed.

She reached for her robe and turned to see Thorna still waiting on the pillow.

"You'd better go," she said. "Don't forget—tomorrow night."

As she opened her door, she realized who had cried out in the night. She ran down the hall and met Art McFarland coming from the opposite direction. Freida Steele was laboring up the stairs from the lounge, her heavy body wrapped in a pink house-coat. Jimmy, in his shorts, met his mother at the head of the stairs.

"A woman screamed, Mom. Was it Sylvia?"

"I'm sure I don't..."

McFarland threw open the door to Charlotte Grande's room. Sylvia, close behind him, started to scream, then clapped her hand tightly over her mouth. She turned in time to stop Jimmy Steele at the door.

"You'd better go back to your room, Jimmy," she said.

Freida saw Sylvia's expression and started to sob.

Sylvia slammed the door in her face. She turned toward the bed. McFarland released Charlotte's limp wrist and looked up at Sylvia, his eyes burning with rage.

"She's dead," he said. "We can thank those little green devils, and their darts.".

"Oh I—no!"

Sylvia moved toward the bed slowly, hating to look, knowing that she must. Charlotte had been reading. The book was on the floor. The dark red robe was torn open. Her face and throat were Covered with blood. Her eyes stared straight at the ceiling.

"It's going to be a hell of a case for the police," McFarland said bitterly. "We'll all go to jail if we start talking about green fairies."

EVENTS were piling up too swiftly to suit Art McFarland. During the short weeks since he had returned from Frobisher Bay, J. Manning Clark had been lost and then found in the jungles of the Matto Grosso. McFarland had been attacked and pronounced "conquered" by little men with bows and arrows. Now Charlotte Grande was dead.

McFarland wandered around the study, sipping a Tom Collins, and trying to make sense out of the situation. He wished he'd stayed at Frobisher Bay all summer. Even Karau would be preferable to this.

Ironically enough, all this had happened because he had accepted that battered tea-pot of rattling-marbles from Karau.

It was late in the afternoon of the day following Charlotte's death. The police had come, questioned everyone and gone. No one, thank God, had mentioned the fairies. Charlotte had been taken away. The howl of the police ambulance still sounded in McFarland's ears. He shook his head, put the empty glass on the bookcase and stared for a long time out the window toward the greenhouse. Damned if he was going to go out and mix up again with those little devils.

Jimmy Steele came downstairs from his mother's room. Freida had been sobbing loudly all day and Howard Steele had finally given up trying to comfort her and had gone to the factory.

Jimmy wandered hesitantly into the library. He sat on the edge of a chair near the hall, staring at McFarland.

"Hello, Jimmy," McFarland said. "Your mother feeling any better?"

Jimmy shook his head. He had a terrific lump in his throat that wouldn't go away. He'd liked Charlotte a lot. She was a pretty lady. After a while he left his chair and came to the window. He grasped one of McFarland's fingers in his hand, and stared out the window.

"Art?"

"Uhuh?"

"You think the green men might have killed Charlotte?"

McFarland looked startled, then remembered that Jimmy had been attacked in the same manner.

He stared down at the youngster.

"Jimmy - tell me about them, will you?"

Jimmy's jaw set in a determined line, then he looked up, and his expression softened. Tears were in his eyes.

"I promised not to tell, Art, but they didn't play fair. They shot arrows at me."

"But why?"

Jimmy shuddered.

"I said I was going to tell, and they told me I shouldn't."

"Tell what, Jimmy?"

"About me learning—teaching them our language."

McFarland sat down in the davenport and motioned for the boy to sit beside him.

"Look, son," he said sternly, "you start at the beginning and tell me everything you know about the green fairies."

JIMMY took a deep breath. "They came into my room one night. They kept coming back again, and I said I wouldn't tell about them because they were fun to have around. They started pointing at the words in my Robin Hood book. They wanted to learn how to talk like us."

He hesitated, obviously very impressed by what had happened.

"The leader—, he called himself Thorna—is awful smart. He learned how to talk like me right away. Then one night he said I mustn't tell. That he was going to conquer the whole world. I was scared. I said I was going to tell you, and then they all shot arrows at me. It didn't hurt much, Art, but I'm glad you came when you did."

He added the last part bravely, then subsided into silence.

McFarland sat very still for a long time. Then he left the boy and went outside into the garden.

"I'm damned," he kept repeating softly to himself.

He circled the greenhouse slowly.

There was only one entrance other than the door itself. Near the rear of the building he found a small pane of broken glass. He went to the tool shed and found another window-pane. Returning, he placed it securely over the hole. He found a padlock in the shed, slipped it into the door of the greenhouse and locked it. He didn't know that Thorna and his warriors had already escaped from the Palace of Glass. Ben, the red-haired gardener was leaning on a rake near the corner of the house. McFarland approached him.

"Stay out of the greenhouse from now on, Ben," he said.

The gardener started to protest.

"But the plants, sir. They need attention daily."

"Never mind, Ben," McFarland said, then added a little lamely, "I'm starting some tropical stuff in there next spring. I want the junk we have now to die out."

He turned abruptly and walked away. Ben removed his cap slowly and scratched his head. Then he started to rake again. Orders, even screwy ones, were orders.

WHILE McFarland was occupied with his tour of the grounds, Sylvia Clark had made a decision. One thing convinced her that the plant men had not murdered Charlotte Grande. They had attacked both Jimmy and Art and the wounds were only slight. Charlotte had been cut deeply. Deeply enough to die before anyone reached her door.

At the moment, Sylvia was busy packing a large, corrugated box. It was a sturdy affair, suitable for air-express. She had called for an express pick-up. She placed the last plasta inside the box, folded the cover down and sealed it with tape. On the outer side she wrote directions that would insure the box delivered to J. Manning Clark in the Matto Grosso district in Brazil.

Thorna had assured her that his people could live in a suspended state inside the plastas. He also promised that when the plastas became very warm and moisture penetrated the packing, he would give orders that their prison be broken open. After that, Sylvia told him, it would be but a short distance to the steamy jungle, and a suitable home.

Sylvia was almost sure that she was doing the right thing. She had found a bloody ice-pick pushed between the sheet and mattress of Charlotte's bed, and she didn't want to tell anyone until she had an idea who might have used it.

Whoever had used the pick on Charlotte knew about the fairies, and had tried to imitate their attack.

She was almost sure that no one but Jimmy, Art and herself knew about those little green men. It couldn't be one of them.

She hoped that she wasn't mistaken. That she wasn't sending a box full of murderers to South America.

J. MANNING CLARK returned from Brazil two weeks after Sylvia mailed him the package containing the plant men. He flew home without letting them know that he was coming. His entrance to Art McFarland's home was abrupt and without fanfare, as were all of J. Manning's movements. As usual, since Charlotte Grande's death, the Steeles, McFarland and Sylvia were collected in the library, talking about practically any subject but the one that interested them most.

J. Manning, huge, gray old warrior that he was, opened the door and walked calmly in on the scene.

"Well? Well? Don't stand there gaping at me!"

When the excitement had died down slightly, Sylvia had kissed her father until he was actually blushing, and the others had gripped his hand, J. M. found a place at McFarland's side and sat down. Sylvia sat close to him.

"I suppose you've all been wondering what I was doing there in that hellhole of a jungle?"

J. Manning was well past fifty with a face that was toughened by the wind and sun of strange lands.

"I was about ready to take a fast trip to the Matto Grosso," McFarland said. "Why didn't you send more letters?"

J. Manning chuckled.