RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Jean-Leon Gerome (1824-1904)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Jean-Leon Gerome (1824-1904)

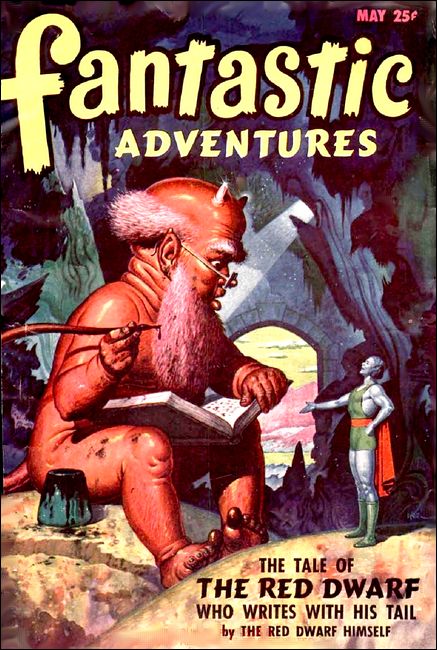

Fantastic Adventures, May 1947, with "The Emperor's Eye"

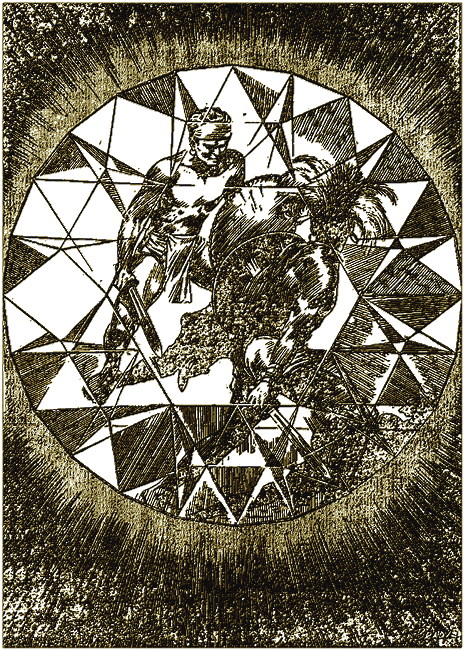

Pale light shimmered in the lens, then a strange scene became visible to the eye.

It was called the Eye Of Magic by the Old Ones—this strange

bit of ruby glass. And if you looked into it too long

you....

I HAVE hesitated for many weeks, to record these words. Now I am forced to do so. Why am I forced to give to the world a story that is mine, and mine alone? Why must I go against my will and pass on to you something that I prefer to remain locked within myself?

If your name was Ron Crawford, and you entered an old antique shop on June twentieth, to come out some three months later, would your friends ask questions? If you entered sound of body and mind, to come out with your back and waist lashed with bloody whip marks, would people demand an explanation? I think so.

Well, my name is Ron Crawford, and I believe that the time has come when I can keep my secret no longer. A few of my personal friends demand an explanation, and they deserve one.

I recall the day clearly, for the morning was spent in the preparation of a special Sunday feature article about that infamous God of Carthage, the thing that swallowed living persons in a stomach of fire and gorged upon burnt flesh, blood-encrusted Baal-Molach.

I explain my calling briefly by saying that I am and was employed at the Central Museum of Ancient History, as librarian. I have a fair knack with words, and do an occasional piece for special newspaper supplements.

Back to the facts. On June twentieth I left the museum at nine in the morning, carrying the manuscript—"Baal-Moloch, Fire God of Hell" tucked under my arm. It was worth, I hoped, about fifty dollars to me. I treated it accordingly. Once it was in the hands of the editor of the Central Times, I took a bus across town, planning to visit some old friends.

I dropped off the bus at Kenmoor Avenue, a dingy little street on which a small group of people catered to the public's love for the ancient. It was a warm, sunny afternoon by now, and I moved slowly, looking into several windows containing antiques.

Half way down the block I stopped short. I was staring through a fly-specked window at an odd collection of odds and ends from all ages. What had caught my eye? That's the uncanny part of it. I had no idea. I have a habit of seeing something before my eyes actually focus upon it. Something of unusual interest had stopped me in my tracks, yet I wasn't sure of the specific item.

I stood there with hands clasped behind my back, legs apart at a comfortable angle, and looked at the bits of flotsam left here from other ages.

There were a dozen ancient musical instruments, an old typewriter, a broken chair, and a battered, felt-lined case containing some rings and bits of colored glass.

I sucked in my breath sharply.

Close to the glass, and in a position where I failed to place it clearly in my mind at first, was the oddest bit of glass I had ever seen. Even through the dirty window, the sun caused it to glow like a thing alive. It had the quality and color of a ruby, but was much larger than any I have ever seen. It couldn't be a ruby, for it was shaped more like a lens. Like, the lens, let me explain, of a pair of rose-colored glasses.

My own thoughts caused me certain amusement. How often had I heard the term "through rose-colored glasses"? This then, was my own private dream, and I decided then and there to look through my personal rose-colored glass.

I was impatient to enter the shop, and to stare through the lens. It almost seemed at that moment as though magic was in-the glass. As though I would find a better, more exciting world beyond that bit of glass.

"Bosh," I said aloud, and the sound of my own voice startled me. I pushed on the door and entered. A set of chimes announced my coming. I smelled the dusty, age-old odor of the place, and stood there, looking over everything in sight. The counter was covered by all sorts of junk. Musical instruments, knives, watches, all hung from the wall.

A short, rotund old man came hobbling from the rear of the store. He wore a once-white shirt, partly covered by a buttonless vest. His eyes were hidden behind a green eye shade. He rubbed his hands together violently, as though to gain certain warmth from the movement.

"There is something' you would like?"

It was both a question and a promise. I made the error of glancing toward the window. At once he pounced upon the first object in view and came back with a hunting knife.

"Fine blade," he said with great enthusiasm. "Very good for hunting."

I shook my head, and it made him appear very sad. He replaced the knife and started to tug on an old violin case.

"Moosic is a wonderful gift."

"Not for me," I said.

He hunched his shoulders and rubbed his hands once more, as though not ready to give up.

"Then—you saw something in the window?"

I MOVED closer to the case of odd jewelry and pointed to the

ruby-like lens.

"May I look at that, please?"

His grin broadened.

"You can look," he assured me. "I don't know what it is, but look!"

It took a lot of puffing on his part to reach the lens. He placed it carefully in my palm. My fingers touched the outer rim of the lens, and a strange, tingling excitement filled me. I've never had any object exercise so great a power over my nerves and blood stream. It was like a thing alive. Like a ruby eye staring up at me. Here was something that meant much to me, and yet I could not guess what, or how.

"Odds and ends," the little man was mumbling half to himself. "A lady comes in with a hand full of odds and ends. There's some gold. Maybe a good stone. I take the lot. That's in the bottom of the box. What is it?"

He didn't expect an answer. He was speaking a riddle, for which he knew there was no answer.

Only half hearing him, I polished the lens on my coat lapel, I felt a little foolish, standing there with that bit of worthless glass in my hand.

How could I tell him I wanted to look through it—at a rose-colored world? It was an insane idea. Still, I told myself, if you have a whim, satisfy it.

"I'll give you two-bits for it," I said.

He didn't hesitate.

"I made a good investment on the other stuff," he explained. "Two-bits from you is clear profit."

I passed him the coin, half expected him to bite it to make sure of its worth, and watched him slip it into his vest pocket.

We stood there, staring at each other. I said:

"Thanks. I guess that's all."

"Don't mention it. The pleasure is all mine."

I turned my back to him. I took three steps toward the door, could contain my curiosity no longer, and lifted the ruby lens to my right eye.

So many things can take place in a second. So many things, mentally and physically. At once I realized that by closing my left eye and looking through the lens with my right, I could see exactly nothing. Then, when disappointment flooded over me, I did see something.

Something so incredibly horrible that I tried to take my eye away, and could not. My arm seemed frozen rigid, my fingers would not loosen themselves from the ruby lens. I was paralyzed.

I tried to speak—to cry out, but no sound came from my lips.

Slowly, ever so slowly, the glass seemed to grow to a sea of scarlet. It was as though I had been tossed into a vest ocean of blood. The ugly stuff was flowing about me, first in drops,-then in filthy pools.

With every muscle, every bit of strength I possessed, I tried to force myself to drop that lens. I could not.

Very slowly, I was lifted until I was well above the floor. My body remained rigid, and I whirled in a maddening circle. I whirled, faster and faster, end over end through nothingness.

As I twisted about, I knew I was no longer in the shop. I was not in a familiar world. I twisted and gyrated directly into that world of dripping, flowing red.

I could shout once more, but my voice could summon no one.

The pressure upon my body became almost unbearable. I was hot and cold in spells. I stared through the lens intently. I could see only the ghastly sea ahead of me.

GRADUALLY the twisting motion stopped. I moved slowly out of

the orbit I had been locked within. My body righted itself and I

stood on something solid. The blood pool wavered and formed

itself into thousands of designs. I remember having one insane

thought.

"If Disney could create colors like this, he could frighten the entire world with one movie."

The designs were beginning to make sense. I was aware of a picture ahead of me. A picture in red. I was free to move. I could remove the glass from my eyes.

I stood in the center of a small room, but it was a room I recognized as having been gone for these many centuries. I was present inside the apartment of a Roman noblewoman. I knew this, for I have studied such things for many years. I was as much at home as I would have been had I actually lived here myself. Although the ruby lens allowed me to examine the room, I was still facing that dull, maddening red.

I had been drawn swiftly through Hell itself, and dropped here in this place.

Slowly, for I was badly frightened, I removed the lens from my eye. The dream room did not fade. I did not fall back into my own groove of life. Instead, the room remained, and with me in it. Only the colors changed and became normal.

I wasn't sure from the first, just what sort of a dream I had invaded. Remember at that time, I was re-living the past for the first time. Now, as I write, details seem a bit less startling. It's hard to combine my present reactions with those I first felt, upon finding myself in the room of the noblewoman, Agrippina; But wait, for I am ahead of my story.

The room was low ceilinged, rather spacious, and the floor was inlaid with thousands of colored tile.

The walls were decorated lavishly. Pictures wrought of bronze and gold were everywhere. The couch, a huge thing, was covered with brilliant fabrics. Chairs were covered with hand-carved pictures of ivory and tortoise shell. Bronze braziers stood in the corners of the roof, burning brightly, warming the place to perfect comfort.

I stood transfixed, my mind absorbing each detail slowly. I tried to probe and solve the problem, but I could not. This was no dream, for as I moved about, I touched certain objects and found them real. My knees, still weak, struck a heavy chair and I felt pain.

I was sure of this much. Whether a clever theatrical trick, or reality, the room was honestly constructed. Was I going mad from some hoax? But who would go to the trouble of hypnotizing and placing me in these surroundings? I would be presumptuous to believe that I was important enough to bother with.

Was I, by the magic of the ruby lens, actually transported here into a world of the past which I had studied so carefully?

A high-pitched, tortured scream came from outside the room. That, I told myself, was no dream. It was a warning that I must act at once. I had to face the situation with my mind fully awake, until I understood what was happening. I glanced around hurriedly for an avenue of retreat. There was one door from the chamber. Light came through a single, broad window. What lay beyond? For the moment I must remain here. I must preserve some remnant of sanity. If I went out that window, would I drop into—nothing?

I was sure that the cry emerged from a woman's throat. This was confirmed by the swift, light tread outside the door. I saw the heavy pink drapes that bordered the window, and slipped hurriedly behind them. The very color of the drapes told me that this was the woman's chamber. That she sought refuge here.

The door opened swiftly. The woman came, running, panting with fear. Behind her, in hurried pursuit, came half a dozen heavily-armored soldiers. Why didn't I question their dress? Why wasn't I amazed by what I saw? Remember, I had studied all this many times. I saw now, only what I had imagined for many, many years.

The woman wasn't young, and yet there was a beauty about her that whispered her loveliness as an ageless thing. She was clad in a pale blue robe that flowed about a delicately chiseled body. Her face, attractive even in terror, was carefully made up with delicately colored cosmetics. Dark tresses flowed about her face—her slender neck. She threw herself desperately upon the bed. The blue eyes, flashing wildly, mirrored horror. Her nostrils were distended.

She threw one arm up and over her face.

Already the men were closing in about her. Daggers were drawn. Short, ugly blades sought her flesh.

AT THAT instant I could see only the woman. She tossed the

robe from her, revealing the delicately colored flesh, the firm

smoothness of her unprotected body. Struggle as I might, I could

not move to save her. Here was beauty, trying to save itself

against the bite of steel. Every nerve in me fought against what

was to happen, but I was frozen to the wall.

Slowly her hand came away from her face. Carefully manicured fingers moved down her side. I had never imagined such perfection from a Goddess. Her breathing was hard. Her entire body pulsated with the longing to live.

An assassin shouted in a guttural voice. I heard her cry out for pity, and still there was fury in her words.

"Kill me, brave soldiers. You see that I cannot protect myself. My armor is as thick as my white skin."

"They cannot," I told myself. "They cannot destroy..."

A blade descended, hit the full curve of her breast and buried itself in her heart. She fell back, struggled to rise again, and another dagger buried itself beside the first. They stood over her and lashed out time after time until she was still. It was a long time before her corpse lay silent and did not writhe under their blows.

I TRY to express myself clearly and yet how can a man say that he watched a defenseless woman die without any attempt to protect her? Say what you will. I could not move. If you were allowed, even for an instant, to see history as it made itself long before you and I were alive on this earth, could you change one detail of that history? That, I think, will explain my point.

It was a long time after they left and before my stunned mind would function clearly again. I say a long time. Time is relative. It seemed ages, but I suppose I looked at that bloody corpse for only the matter of minutes. Through me coursed such hatred as few men undergo. Once I left my hiding place and started to move toward the mutilated, bloody thing on the bed. Her eyes were wide open, but they would never greet me as they might have, a few minutes ago. The brilliance was gone from her face. She was ashen, and the cosmetics seemed too bright—too barbaric. There should have been no color on that face.

I heard footsteps once more. I retreated hurriedly and hardly breathed in my hiding place near the wall.

A young man entered the room. He startled me, for he appeared vaguely familiar. I told myself I could not know him. This place is strange to me. I have never been here before.

He walked slowly to the bed. He seemed half frightened, half exuberant over what he saw. Behind him walked two of the assassins with sheathed swords. Their faces wore cruel smiles.

The young man was thick-set and he was clad in a rich, white flowing robe. His sandaled feet carried him in a listless, flowing motion. His stomach was large for a man his age, and his face, gray and blotched by unclean living. His hair, even his face, reminded me somehow of the dead woman before him. Once, as he turned toward the window, I held my breath and saw the dull, slate colored eyes and the cruel mouth.

He stopped a few short steps from the couch and a smile touched his lips. His voice, so soft that it was caressing, came to me clearly.

"I did not know that I had so beautiful a mother."

His voice and words brought such a feeling of revulsion to me as I have never felt toward any man, living or dead. His words brought also a chord of sudden understanding—memory.

It dawned on me at that moment that I knew exactly where I was. I knew the man I stared upon. Only one man in Roman history had stared at his own mother and spoken those words over her corpse. A man born of hatred and spawned in lust. I, Ron Crawford, from 1945, was staring out upon a twice re-acted scene. I knew that the time was somewhere about the year of fifty. I was watching the Emperor, Nero, gloating over his mother's death. This was a murder he had ordered by his own words.

DID I have need to rationalize my own thoughts? Was it

necessary for me to say to myself, "Ron, this is impossible. You

cannot actually be thrown backward' into Roman history?"

Would that have made the situation any the less dangerous? I knew that, dream or no dream, any betrayal of my presence in this room would mean sudden and violent death.

Every muscle in my body ached. Blood pounded at my temples. The youth near the bed withdrew from the room without further words. His men followed him. I was alone with the corpse of the woman Aggripina, who's husband had said on the day of Nero's birth, "No good man can possibly be born from us."

And now, the child had grown up to murder his own mother.

I stood on the balcony, overlooking the city of Rome. The city of Seven Hills, born not so many years ago, and forming one of the most beautiful, most powerful capitols of earth. We were alone, the corpse of Aggripina and I. In spite of my own danger, I had covered the body tenderly with a silken cover. I had tried the door and it was secured from the outside. There was no escape, save from the balcony. How long I had remained in the room, I do not know. Not until darkness came did I dare leave the hiding place behind the drapes.

This thing I looked down upon was no product of a hypnotized mind. This was a city, bathed in the brilliance of a huge, silvery moon, and pulsing with life and sound. This was Rome, ruled in blood and hate. The city was still warm from the day's sun, and impressive with its thousands of acres of tall buildings and huge columns of marble.

Pale yellow light flowed over the streets, touching the Colosseum and the many impressive buildings within sight of my eyes. Streets were lighted with torches that flowed endlessly in every direction. The place was alive, and I remembered the accounts of thieves, murderers and scum who wandered about at night.

I had a job at hand and it could not wait. It was a task I didn't relish, for I still held to the dream that this might all break like a bubble, and release me from a hellish nightmare. That I would find myself back in the world where I rightfully belonged.

I waited for the city to sleep, but sleep it would not accept. The lights remained brilliant. I knew nothing of the time, but the moon was high and I had been here for hours. It must be close to the beginning of the morning hours.

No one had entered the apartment. I grew desperate. I had one plan. Get as far as possible away from this room of death.

The street below me was deserted and filthy with mud. It seemed more like an alley, running between two well lighted thoroughfares. Finally, with my teeth gritted and every nerve on edge, I slipped over the ornate balcony, grasped the metal strands with both hands, took a deep breath and let go. I flexed my knees as I dropped. I hit hard and mud splashed over me. In spite of my flexed knees the fall knocked the wind out of me and I rolled over and over, groaning with pain.

The breath came back slowly and I staggered to my feet. I was hardly ready for the shout of alarm that came as I arose.

"A thief below the balcony of Aggripina. Capture the thief!"

Terror seized me, and I tried to run. White hot pain shot upward from my ankle. I stumbled and fell. I had sprained the ankle badly with the fall I fought to regain my footing. Even as they closed in, I knew that this was no ordinary arrest. I saw the faces 'of the men who had murdered the woman in the room above. They had been waiting.

NERO'S private dogs of war were on guard. They had caught a

prize they had not expected, but I assumed, of no less value. I

was hauled rudely to my feet and spun around to the lantern

light. I heard a brutal chuckle.

I knew that capture now meant death—torture.

Wildly I twisted about and sought to free myself, lashing out in all directions. A fist hit me in the cheek—hard. Blood tasted salty on my lips. Then my arms were pinned back until I was sure they would be torn from the sockets.

"Murder the thief," someone growled. "He demands no better treatment."

"Wait," cried another. It was a voice of authority. "The Emperor should hear of this. He is no common thief, this man. He wears strange garb. He dropped from the balcony of the Emperor's beloved mother. He may be a valuable prize."

I was unable to see them, for the lantern remained poised in front of my eyes.

"Saved he will be," a third voice said. "The Emperor pays well."

"But not so well that I'll be denied the pleasure of one blow."

A terrific force struck me full in the face. A searing, hot flame seemed to blank out the remainder of the world. After that, I knew, no more.

HOW I first came to the Colosseum I do not know. I suppose I

was carried here like a sack of potatoes, by the husky soldiers

who captured me, When I awakened, I was locked in a cold, rock

cell.

There was a single metal door with three bars worked into a small opening. This was the single entrance which allowed a small quota of foul air to enter. Many men had evidently been imprisoned here, and I suppose none of them were allowed to wash. There was a bare cot of rough boards, a flimsy robe tossed across it, and an earth bowl in the far corner. I put the robe on at once, for all my clothing had been stolen, and the little warmth I could gather from the clothing was much needed. Outside the cell, I could hear the hollow sounds of voices, and the corridor was full of mysterious echoes. I awakened with a throbbing headache. I was intensely hungry. Whether it was day or night, I didn't know.

I sat on the cot, after throwing the robe about myself, and shivered in agony. There came the occasional flash of a torch. I could make nothing of the distant voices. They were muffled and foreign to my ears.

I must have waited two hours, after I awakened, for my jailor to come. When he did, he was the filthiest scum of humanity I have ever seen. His robe would have passed for a dirty wiping cloth. He had no teeth, a low forehead, wild, uncombed hair and a slouching cringing way about him that put me on guard at once.

He carried a slop bowl full of greasy porridge. I suppose it was made of meat scraps and cereal. He placed it on the floor, favored me with a sly wink and backed out of the door. He left without speaking a word.

I smelled the contents of the bowl and forgot at once, any idea I may have had to eating. In half an hour, I would judge, he was back. He swore at me in a guttural tongue and emptied the bowl on the cell floor. He locked me in securely.

That was my final contact with man for approximately twenty-four hours. I say again, I could only guess at time. It was probably a bad guess. I took stock of my assets, and decided I had none. My own clothing was gone, and so was the ruby lens. They had left sandals in place of my shoes.

I was in a panic, for I knew that the ruby lens had brought me here, and without it, I had no opportunity to escape this mad world.

A LONG-DRAWN blast upon a horn brought me out of the stupor I

was in. I sat up weakly, bracing myself with my hands on either

side against the cot. The cell was only dimly lighted by the

torches outside. I was weak with hunger and cold. I managed to

struggle to my feet and saw men moving swiftly up and down the

corridor beyond the cell door. There was a great rattling of

locks and the sound of chains rattling and being dropped. Cell

doors near mine were being opened. I waited, daring to hope that

I also, would soon be free. I shook from head to foot.

At last my own cell was thrown open and I went out, to mingle with the smells and sounds that hundreds of; black, white and yellow men make when crowded into small confines. The warm smell of animal droppings was foul in the air. Slaves were dressed in many costumes. Various colors clashed with the smoking yellow of the torch light.

Something big was happening. I sensed it. There must have been half a thousand of us in the long, wide corridor. Few of them spoke. They milled into groups, like frightened,'condemned animals.

I overheard one word:

"Arena!"

It meant little to me then, for I was not thinking clearly. My mind still dung to thoughts of food and rest and warmth. Slowly, like an immense tidal wave, we started to move in a definite direction down the corridor. I saw soldiers, occasionally, swinging their whips—shouting commands.

I reached a place where light flooded in and blinded me. I threw up my hands to protect my eyes and shuffled-on, pushed from behind and on all sides.

Gradually the light wasn't so bad, and I let my hands drop. My face was rough and bearded. My lips, parched and dry, were open and I imagine I wasn't a pretty sight.

Ahead of us, already crowded with men of every breed, was the vast, wooden floored arena that acted' as stage to death for the Colosseum. This, then, was Nero's Arena. Around it was a high wall, and above that, row upon row of marble walls and seats. Upward, it seemed to the sky, were line upon line of cleanly robed spectators staring with fixed curiosity at we who came to—death.

Someone thrust a short, blunt blade in my hand. With a listless, detached feeling, I held the blade at my side and continued to stare up at the free, blue sky and the wonderful sight of the Colosseum around me. It was like a nightmare in which you suffer and do not suffer—in which you die a million times, and yet stand there and watch yourself die.

Soldiers moved among the throng in the Arena. They herded us about like cattle. We were being roughly divided into two groups, one group on each side of the area.

I was pushed roughly against the wall, and I choked with the heat of the sun and the dryness of-the dust that hung over all of us. I judge that there were two armies of men condemned to death, probably a thousand in all.

Above us, in another world, thousands of people were waiting to cheer as we spilled our blood on the plank floor. They were making a game of our misery. Now the Arena was empty of soldiers.

A high pitched trumpet sounded in a distance. I received a rough push in the back that sent me spinning forward. At the same time, cries of hatred rang from hundreds of throats. I managed to keep my feet under me, and lifted the weapon that would decide my own fate. I was conscious of a clean, grinning face close to my own. He was a big man, stripped to the waist, with sweat pouring from every pore. He had a shock of uncombed carrot red hair. He shouted at me.

"Fight like a fool. Give no quarter or you'll die."

That man, for he had evidently been watching, and pitied me, fought at my side from then on like a demon.

His huge shoulders were almost black from the sun and wind. Rippling muscles played under his skin as he leaped, first ahead of me, then to one side. I'm not a fighting man, but when a knife comes ripping toward you, you find ways of keeping it from being buried in your guts. You dodge and scream and slug your way through. You sweat and cry and keep on cutting and hacking at flesh, as long as strength remains in your body. I don't know how long I followed the red headed man into battle. At least once, he warned me with his shouting, so that I could pivot and save my back from receiving ten inches of hard steel.

I was part of this battle, and if I were to live, I had to kill. My heart wasn't in it at first. Fighting for life changes that. There came the time when to kill was my prime mover. To push my sword into soft flesh, rip it loose and plunge again, was the only thing I lived for.

The game was no longer an impersonal thing. It was a beast that snarled and pounced upon me, and retreated, when I was lucky, to lick its wounds.

HOW long it went on, I'll never know. I lived to draw blood

and I waded in the gore that made the planks slimy and footing

uncertain. When it was over, and the trumpets had sounded, I

looked around me. Redhead was still there, not ten yards away,

grinning at me as though the whole thing had been good fun and

necessary exercise. I closed my eyes momentarily to take away the

dizziness that flooded over me. Mangled remains of once living

men were stacked about like slaughtered cattle.

Then I was aware of a voice, far away and not clear enough for me to understand. I looked up and up, and saw the dazzling thrones of ivory and gold. I saw the lovely woman and the ugly Emperor who sat upon them. It was he who spoke. He was holding his hand in the air. His thumb pointed to the sky.

Those who still lived among the blood bath in the arena, were to be spared.

We were given life, at least for the time, by the grace of the pot-bellied, slate-eyed youth who last night, had caused the assassination of his own mother.

Here was Nero, Emperor of all Rome, sparing his slaves while the words he had spoken only last night, still echoed in my ears. Lisping, delicately spoken words, as he stared down at the nude, blood soaked body of the woman who had given him life.

"I did not know I had so beautiful a mother."

Suddenly I forgot everything about me, and could see only him. r See him and hate him and feel myself sick in the pit of my stomach.

The man for whom I felt only disgust, ordered me into his presence. I, Ron Crawford, was on my way to talk to Emperor Nero, in his bath.

First I was forced, if force was necessary, to wash myself from head to foot and don clean clothing. As the games were still under way, Nero and his wife were staying in the beautiful apartment behind the thrones, in the heart of the Colosseum.

I was taken into a small, tiled room, where Nero was at work cleansing the dust of the day from his ample body. In the center of the place was a huge tub, set into the floor. The ugly Emperor was seated in this tub, suds about his chest, puffing and carrying on like a six-year-old in the middle of the Saturday night bath. He splashed water with great abandon, and studied me with amused eyes as I stood inside the door, waiting for him to speak. The dull, luster less eyes moved, over me.

The thick lips moved at last.

"You wonder why I summon you, slave?"

I knew that it would be wise to act humble before him. I kept my mouth closed, not trusting myself to speak without insulting him. He crawled from the tub and wrapped himself in a huge towel. Then, parading slowly about, his fat toes leaving wet marks on the tile floor, he frowned. His lips were pouted slightly.

"Yesterday I spared your life. Don't you fear that today I might order your death by some interesting manner of torture?"

In spite of myself, I laughed shortly. I felt disgust more than fear.

"Should I flatter myself, that, from hundreds of men, you paid special attention to me?"

He turned slowly and regarded me with certain respect.

"Oddly enough, my thoughts were for you," he said. "I watched you fight yesterday. You were pointed out to me as the mysterious intruder who invaded a certain apartment. You're presence there had special meaning for me."

His eyes narrowed.

"You seem to have in your possession, certain knowledge and perhaps memories that would harm me if generally passed along. I wish to question you."

I WAS sure that he referred not only to his mother, but also

to the ruby lens. He could easily have watched me die before I

could betray his secret. However, the appearance of myself

and the strange lens, might be a different story. How much

should I tell him? I had to protect my life if that were

possible. There were loop-holes through which I might escape. I

regarded him with a show of calmness that was not in my

heart.

"You are interested In the object I brought with me to this place? Without me alive, that object would be worthless. I am able, of course, to exercise certain magic."

At the sound of the word, I'm sure that his eyes showed sparkle and interest. I might be hitting close to the mark.

"The Emperor's Eye," I heard him say, half in a whisper, as though speaking to himself.

Suddenly it was clear to me that the ruby lens and the Emperor's Eye were one and the same, I cursed myself for not remembering before. That term should be familiar to me, but it wasn't. Vague memories stirred within me. Old books I had read. Mysterious stories of an Emperor's Eye, given to a Roman leader by an Egyptian Princess, and later cursed by an Egyptian Priest. If I could only clarify my own thoughts. Nero was watching me closely. He almost seemed to notice my thought process.

"The ruby lens had great power," I said hurriedly. "I brought it with me from a distant land." I had hooked him cleverly. I knew that he was puzzled by the strangeness of my clothing, by my appearance and actions.

"Listen wisely," I said. "I came at an opportune time. I would achieve great power if I betrayed certain information I ran across upon arriving here."

I was playing with Roman dynamite at the moment. His eyes were slits of anger. Murder was his specialty. If he dared...?

"You were in the apartment of Aggripina," he lisped. "You saw certain things there that make you dangerous, alive."

I shrugged.

"On the other hand, I have certain value alive. I am not a Roman or a slave. I came here from a far place, and by employing a great power which you are unable to make use of without my instructions. A place so far that you can never even dream of going there. My knowledge is valuable to you. You know something of the ruby lens. I know much more."

The hatred seemed to drain from him, and instead, I saw lust for a power he coveted. What that power was, even I couldn't guess. "Bluff, Ron," I told myself desperately, "Bluffing is the only way of saving yourself."

"It is truly the Emperor's Eye?"

He had me stumped, for I remembered nothing of importance about the lens. It was nothing but a memory pattern, too faint for me to grasp. I nodded.

"It is the Emperor's Eye," I said.

His voice sank to an eager whisper. He came close to me and put one fat hand on my shoulder.

"The same Eye of magic that belonged to Cleopatra? The Eye that opened magic adventure and wonderful pleasures to the Emperor Caesar?"

I was more at sea than ever. If I could only remember what I knew, and yet what I did not know.

"The same," I said. "It has been in my possession. I travelled with it here. In my hands, it is useful. With my death, it will return to the age from which it came. You will never make use of it, once I am harmed."

I wasn't sure that he believed. However, at this moment, the Eye was all important to him. He could not chance a failure to test it. He had on more question.

"Where do you come from, intruder?"

I SMILED broadly. I had the upper hand now.

"From beyond the very chasm of time," I said. "From an age where none of the things that happen here are secret. Call me Master, rather than slave. If I have your friendship, then give me also your respect."

I'm not proving to you that I was brave. I was frightened, I've never been so darned frightened in my life. It was a case of win all or lose everything.

"Your clothing was strange," he said thoughtfully. "The short cloak was of a strange fabric. Your stocking were of rich eastern silk. Rare materials covered your body. You come from the Orient?"

I had him guessing, and I intended to keep him that way,

"I say that I come from beyond the chasm of time," I said. "Now, must I try myself with foolish answers to foolish questions? If you picture a world where buildings touch the sky, and man made machines fly at will through the Heavens, then you see a small part of my world. People in my world can band together in a day, to destroy such a place as this with a single dropped explosive. Now, is that enough, or must I prove it?"

He was shaking his head from side to side, a look of foolish wonder in his eyes.

"Only one thing troubles me," he said. "Are you prepared to forget certain things you saw, upon first coming to Rome?"

Show respect or fear of him, I thought, and you are lost. I drew myself up haughtily.

"I forget nothing," I snapped. "I keep secrets well when they do not concern me. I am your friend as long as you treat me decently. I may share some of the secrets of the Emperor's Eye. I make no promise, however. It depends upon my treatment at your hands:"

Nero, for the present, was satisfied and flattered.

"I have made a grave error," he said slowly. "You will be escorted to your rooms. If all is not satisfactory, call upon your slaves, or send for me. I hope that your presence here will bring great satisfaction to you—and perhaps—to me also."

"That," I assured him, "sounds more pleasant to me than did the caves of the Colosseum."

Under my outward calm, I was shaking in my sandals. The power of the Emperor's Eye had saved my life, and I had no idea what that power actually was. God grant it, I would remember.

THIS was the last day of the games. I had slept well and I had

dreamed. I have no faith in dreams, other than their effect upon

the inner mind. During my rest, (no doubt the most fortunate

sleep I had ever slept), there came back to me certain bits of

knowledge I had once read and long ago forgotten. The Emperor's

Eye, as Nero had said came from the love enchantress of the Nile,

Cleopatra. Cleopatra who had come to Caesar wrapped in, rare

rugs, to be presented to him in all her loveliness, in his

private chamber.

I say that I am a librarian. Thank God for the profession. These bits of fact and fantasy I had consigned to my inner mind over a period of fifteen years at the Museum. The Emperor's Eye was first a love charm, and was later stolen and cursed by an Egyptian Priest who had reason to hate all Romans. It brought only bad luck to Caesar and those who followed him.

Nero could not know of the curse. He knew only of the great power the Eye held as a love charm. With it, they said, a man could be transported to such gardens of perfumed bliss, that he need never ask for anything more in Heaven itself. Was that what Nero dreamed of?

After that night of dreams, my head was clear again. Nero wished the love secrets of the charm for himself, and it had never occurred to him that by placing the lens to his eyes, he could achieve sudden results. That these results were not pleasant, he could not know. The Eye was a curse, and he still believed it to be a charm.

This was the knowledge I had managed to regain from the forgotten file cabinet of my mind, on that warm night in my new apartment.

THE sun was bright in the windows of the room. I was up and

dressed when slaves brought huge baskets of fruit for me to feast

upon. I ate little, for my problem was as great as ever. I

couldn't satisfy Nero's lust for the use of the charm, for if he

used it, he would suffer as I had, by being tossed away into some

remote spot. I would be left to explain what had happened, and

with his going, my last avenue of escape would be rudely cut

off.

I leaned back on my bed, trying to ignore the sleepiness and content that stole over me with the warmth of the sun. A girl entered the room alone, and came hesitantly toward me. I sat up, staring into deep violet eyes that sparkled with interest and amusement. Her slim, smoothly satin body was draped in seductive silken wraps. Her sandals displayed crimson toe-nails and tiny feet.

I had seen this woman before. Held again by the magic of the eyes, I remembered her. I had watched her from a distance, seated beside Nero in the Colosseum. Poppaea Sabina, enchantress of all men, wife of the Emperor.

"The Emperor has told me of you, intruder," she said. "You come truly from a world beyond our time?"

There was a soothing, teasing rhythm to her voice that held me.

"And you are Poppaea Sabina," I said. "I have heard much through history of your loveliness. Of the beauty that weaves a spell about the heart of all men."

Her blush was as innocent and pink as the coloring of a small girl's delicate cheek. She bowed her head slightly.

"Thank you, intruder," she whispered. "Your compliments are weapons, aimed well at my heart."

My thoughts were in reality, a long distance from this room now. If I had played with dynamite in speaking to Nero, then this woman of nobility was the atomic bomb of Rome. Nero would take pleasure in feeding bits of my flesh to the Russians' bears, chained in hunger below the very apartment I occupied. Should he hear the words I had just used, my life was gone as surely as the men who died yesterday.

"I would like to leave this room," I said, and I really mean it. I wanted to get away from her and stay away—as far as I could. "Could I go to the place where we watch the games?"

She seemed alarmed.

"Oh, no, you would not leave me when I am lonely. Nero is dressing. Talk to me, and we three will attend the games together."

I was sure that I had to get away from her while there was time. I started toward the door.

"We will talk some other time," I said. "If you will show me the way to the games. I'm lost in these vast halls."

She seemed resigned. She took my arm, and it was no accident that her fingers pressed tightly into my flesh. She was warm and the warmth created an aroma of perfume that made me dizzy.

"Then come, but I will pout as a child, if you pay so little attention to me in the future."

In five minutes, we had pursued a round-about course through the halls and she had left me sitting on a cushioned marble bench where I could look down upon the arena.

I spent ten miserable minutes watching a lion, starved for food, tear down a screaming, dying slave and eat the wretch bit by bit. School children, having their Saturday afternoon off for the games, ate candies and seemed to enjoy themselves as though they watched a good football game. Mothers cheered and fainted, and were revived to cheer some more. The lion and the audience seemed to have good, moral fun. I was sick and had to retreat once more to the halls behind the Colosseum. This time I found my way alone and avoided Poppaea Sabina. I felt safer, once I reached the apartment again.

NERO came for me there some half hour later. He wore his

finest robe and walked with delicate, mincing steps. He had eaten

and bathed well, for he was in high spirits.

"The good Poppaea tells me you did not like her company," he said upon first seeing me as I stood near the window. "It makes Poppaea feel badly, but frankly, intruder, you are very wise."

I grinned openly at him.

"I have never been attracted to another person's private property," I said, "be it attractive or repulsive."

He nodded and chuckled.

"I would not say that Poppaea was repulsive?"

I shook my head.

"On the contrary," I agreed, "the Emperor shows great good taste. Poppaea Sabina, so it is told in our books of history, is as fine as silk and has most attractive assets. A fine choice for a monarch."

He took the flattery well, and for the present, I had made him forget the Emperor's Eye.

"And now shall we seek the games? I wish to speak later of more important things."

Without asking questions, I followed him down the broad marble halls. We met Poppaea and her group of maidservants, and with her, went onward toward the marble and gold thrones.

Nero paid no further attention to me after we were seated.. The same bench, placed at one side of his own splendid throne, had been reserved for me. I tried to act quite at ease, for I was playing the part of a man who could be amazed or changed by no experience. In this acting of mine lay security. How long could I keep it up?

There were animal fights. Dozens of lions matched against wild elephants, imported from Africa. Bears fighting to the death with lean, hungry tigers. I watched a man, chained to a heavy pole, and torn to bits by leopards. What amazed me most was the attitude of the people, including the mildest of them, toward such horrible death.

I could picture some grandmother in the back row taking great interest in the good, clean fun. It was so terrible, and in the same breath, so matter of fact, that I wondered if my own age wasn't a slightly censored version of this same unvarnished lust for blood and human sacrifice.

The part I had dreaded most was the slaughter of humans. Now I knew I could not face what was to come, for two men entered the arena, and each carried a small shield and a shining steel blade.

This was worse than watching the men before, for one of the pair was my friend of the arena a few hours passed, the red headed slave who had saved my life time and again in the fray of battle.

I admired his courage, for he smiled and waved his blade in the air, bowing directly toward the place we occupied. His enemy for the hour was a huge blackamoor, taller by inches than the red head, and looking as black and fierce as the devil of darkness.

A small section of the arena had been raised above the general level. As the two men sprang to the platform, Nero arose, approached me and spoke.

"I grow bored with—this." He waved a hand dramatically toward the arena. "You are my guest, and as such, you will rule the victor! A thumb up, if the vanquished is to live—a thumb down if he is to die. It is simple."

The duel was on as he walked away. I was still thunderstruck by the man who could look upon a man's battle to death as boring and uninteresting to himself. Then it dawned upon me that I had a terrible trust in my hands. I alone would say if these men lived or died.

My eyes glued themselves on the sight below. I became unconscious of everything else that happened about me.

FROM the very first, the red-head had the edge on the black

fighter. He was lighter, and therefore swifter on his feet. His

sword swung through the air twice, to each blow from the

blackamoor. There was terrible strength and energy there, born of

desperation. There was no quarter given or asked for.

I watched with fascination as they whirled about each other. Cheers rose like great waves, drowning every small sound. The blades flashed in the sun, sometimes bright, sometimes tinted with droplets of flying blood. I myself was silently cheering for the first time.

The man with the red hair had to win. It could not be otherwise.

Suddenly it was all over. My friend of the arena must have slipped in the gore beneath his feet. He fell back, caught himself with one elbow and tried to rise. The blackamoor's blade flashed down and when he lifted it again, the red-head had no weapon. It was spinning swiftly across the planks, to stick, upright and quivering, some yards away from them both.

There was no sound how to disturb my concentration on the scene. My blood pounded in my temples. My heart was sick. It seemed to pound so hard that I thought it would break from my ribs.

Then the blackamoor had his blade risen high above his head. He was looking upward, questioningly, his eyes on me.

Slowly I stood up. A sea of white faces were turning, looking upward.

He had won fairly, the blackamoor. There had been no foul play. It was an unfortunate accident. Still, I could make no other choice. My life had been saved, and I must save the redhead's.

I put my thumb up, pointing it into the blue sky.

The blackamoor backed away slowly, never looking at me again. His blade dropped at his side. He moved away. The man with the red hair did not move at once. Then he came to his knees and arose, his head held high. I saw pride there, and bewilderment. He had expected no quarter, but I knew from the pale, set face, that he was grateful.

The audience remained still for a moment. Then, as one voice, a great cheer rang out. I sank back, wiping sweat from my forehead. Popular feeling had approved of my decision. I had done the right things How I sat through the remainder of the games, I don't know. I was not called upon for another decision, for death won them all after that. I was sick and unable to think clearly for the remainder of that day.

I sat again in the presence of Nero, and listened to a man who would willingly kill me, if he was sure that he could do so without doing himself harm. I was permitted to live for two reasons. First, he wasn't sure about my real power. Second, he wanted certain knowledge which he believed I possessed. I sat on a low divan opposite his own, and watched him as he chewed delicately at grapes from a heavy stem. We were without attendants, for he wished no one present with the subject of our conversation being so personal.

It was late at night, and I had been brought here by a man-servant to the small, carefully decorated room. Nero was smiling, sure of himself. He tried slowly, with utmost respect, to pump answers from me.

"I am curious as to how you first obtained the Emperor's Eye."

With the knowledge I had been able to recall, I felt sure that I could stall him off for some time. He shrugged, as though the subject was of little importance.

"There was the matter of a Nile Princess who presented herself and the magic love charm to several great Romans. In our advanced world, such a charm is no longer needed. It is but one of our many possessions passed on from your world."

At the mention of Cleopatra, his eyes glistened. He was greatly impressed.

"I AM told that the Emperor's Eye has the power to bring about

great changes in a man's power. That it gives him the opportunity

to feast upon the lavish passions, without the introduction of

drugs."

I nodded, then frowned.

"While it is of great value to a man, and serves him with Heavenly dishes of delight, I caution you not to attempt to use it without my assistance. Those who have tried to fathom its secret alone, have died dreadful deaths, and suffered from even worse fates."

I had guessed his thoughts correctly, for he paled.

"Why so?" he asked abruptly. "What power do you have that I would not have alone?"

I smiled.

"Not power," I assured him, and he seemed to relax. "Rather, let us use the word knowledge. While you have all the power in the world, I alone have the knowledge of the Eye. The time, and other points, must be taken into consideration."

As much as I would have enjoyed pushing that ruby charm into his eye and thereby, sending him away for all time, to some remote hell of his own, I dared not do so. Upon my head would lie the blame of his disappearance. In addition, I would never escape myself, without the lens.

"Tell me, intruder," he said suddenly, tossing the grapeless stem to the floor, "you claim to have certain vast wells of knowledge, and to have travelled here from great distances. In the light of such knowledge, what do you see in my time that is of great importance?"

This, I thought, is the supreme test—the all important question. The answer would either place me in the position of one who knew dramatic events in advance, so far as he was concerned, or it would brand me as an imposter. How much did I dare say?

"We who travel from time to time, back to ancient cities, are protected by our own magic. While we know of events before you witness them taking place, by the very nature of history, we are powerless to change it. Thereby, we can tell what will happen but we can in no way prevent it from happening!"

He nodded, attempting to look profound and succeeding in looking only stupid and very self contented.

"You speak wisely," he said. "However, I ask for knowledge that will prove your worth to me. Come, intruder, make some of your great predictions."

I was ready when he asked for it, and I gave him an answer that I think affected him more than any words that he ever heard spoken.

"I don't think, the citizens of Rome would approve paying their taxes for the construction of the Golden House, do you?"

He came upright on the divan, fists clenched, eyes blazing.

"The plans are private—my own. No one has seen them."

"Careful," I begged, smiling. "Remember, I am not a spy. I do not have to spy upon you."

He relaxed, but he was visibly shaken.

"No matter. The plans have been seen by no one. Go on. I am very much interested."

"Perhaps, after the fire," I continued, "the plans for the Golden House, a fitting place for you, will be more readily accepted. After all, if Rome burns to the ground, it must be re-built."

The Emperor didn't move that time. His eyes widened with honest fear. There were no blueprints that showed that Rome would burn. Only history had told me that. The devilish plan to burn a city to the ground must have been in his mind only. He knew that. He knew that I possessed almost more knowledge than he himself.

"No one knows of—of—?"

HIS mouth lolled open. He seemed to lose his power of

speech.

"I understand," I said hurriedly. "Remember what I said. I can predict happenings, but I cannot affect their happening in any way. I am only a man and cannot change the course of history that has been written for these thousands of years. You can have respect of me; but you need not fear me. I cannot and would not betray a thing that will happen in spite of myself."

I think I was a form of God to him at that hour. He continued to look at me, and gradually his shaking stopped and he got control over his nerves. I had delivered a long speech and I wasn't entirely sure I had said the right things. Finally he arose from his divan and drew his robe tightly about him. He glanced at the door.

"Perhaps," he faltered, "this interview can be prolonged at a later date. For the present, I must rest. You may live with us and rest in the safety of my house. No one will harm you. When you wish to leave, we will say our farewell and be sorry that you must go."

He hurried from the room as though the devil himself were after him. The great Nero, I thought. I have been able to make a coward of an Emperor. For a few hours at least, he's frightened of me. Frightened of Ron Crawford.

"You are in every way, a nobleman," I said as he left the room. "And now I must also rest."

I did not go to my own apartment after leaving Nero's chamber. I walked slowly in the corridors. I came at last to the deserted, moon-lit terraces that looked down upon the empty arena. The Colosseum was very beautiful and one would not guess that death had been stalking here so short a time ago.

It was a cool night, glowing silver, with every marble column, each terrace dipped in the stuff and left gleaming.

I was alone, centuries away from my people, centuries away from everything I knew.

I stood by the golden thrones, resting against one of them, staring upward at the same sparkling, untroubled sky that men had looked to for ages, and would look too for many more.

I thought once I heard the tap-tap of gentle footsteps against the marble floor. Then I forgot and looked down at the dark, blacked out area of the arena. When would death walk here again? How long before men would again drain blood from other men? When Nero willed it! When his people wanted more sport. War was like that. Let people live in peace for a time, and they longed again for the blood games. Only the games of my day are worse. They destroy nations at a blow, while brutal Nero killed but a few. How long would we go on having enough raw material to throw into our games of human sacrifice?

"Must I follow my lover by so many hidden routes?"

Startled from my dreams, I pivoted to face Poppaea Sabina. She had come up quietly behind me, and stood there staring up with long-lashed eyes, the moon making her a breathing angel of perfection.

Try as I might to condemn this girl—to push her from my mind—I was chocked up inside each time she was near me. I could not control my emotions where she was concerned, and I know that she realized that.

"You shouldn't have come here," I said sternly.

Her lips were in a perfect oval. Her eyes, wide and innocent, stared into my own. Without a word, she put her arms about me and pressed herself close.

I leaned close to her face, smelled the warmth of her perfume and then her lips were pressed to mine, seeking my love.

I broke away from her, trying hard not to prolong the contact.

"You're trying to arrange my death," I said, but I wasn't sure that I even cared!

She smiled and kissed my cheek.

"Call me bad, and unkind and a cheat," she said gently, "but I do not have to seek young men in the darkness. I have done so only because you are very different than anyone I have ever met before. You mean much more to me than you can ever guess, intruder."

I'M NOT sure that I could have remained the stern man from a

mysterious other world, if at that moment, all Hell hadn't broken

loose about us.

How many there were I don't know. I saw the Emperor himself, first. He came from the shadows, and he had not changed his clothing since I left him. He had stalked his prey and caught us cleverly.

Soldiers sprang from all directions. Before I could fight, the girl was torn from me. My arms were pinned behind my back, and Nero came close, pushing his ugly face close to mine.

His eyes were blazing as he grasped the girl by the arm and threw her, face down, upon the floor. He kicked her deliberately in the side.

Whirling upon me once more, he growled:

"Let your damned magic help you now, if it will. I have been under your spell long enough. I suspected you would meet her one of these nights. It was your magic that brought her to you."

Words were useless. Action was impossible. My arms were held by a dozen men. A sharp blade was pressed tightly against my shoulder. It cut through the robe and was pricking my flesh.

"Throw him down below, where he belongs," Nero shouted. His fury was a terrible thing now. "I'll wager a hungry jungle beast will take care of him and his magic."

They threw me to my knees, and kicked me until my body ached from more blows than I could count. I tried to get up, and once I felt sure that in my attempt to save Poppaea from more of his well-aimed kicks, I would be able to reach the pot-bellied fool. He turned on me, however, and while I was still on my knees, sank his foot into my neck. Something snapped and I blacked-out.

HOW long I was in the windowless cell, I don't know. I was

never given food or clothing. I had been stripped of all my

clothing, and sores festered, bled and turned black on my sides

and back. My neck felt as though it was broken.

No man ever went through a worse bit of hell. Through it all, I could see only the girl who had come to me, and who I now swore in my heart, was sincere in her love. Poppaea Sabina I told myself over and over, was in history a woman who drove men mad with love and left them broken and alone. I couldn't make myself believe that. Perhaps no one had known her as I. Perhaps her lips told the truth. Perhaps her words, tender words, were also, honest. Would it be impossible for a girl who never honestly loved a man during her lifetime, to fall desperately in love with another who comes to her from another age?

All my arguments gained me nothing. I only knew that if I could save her from what was to come, I would save her regardless of what happened to me. Fool, perhaps, but at least a fool honest in his convictions.

I moved about for several hours, resting when I could no longer move. I had to keep my blood circulating, for the dampness of the cell and the cold air that came from the cracked rocks, would freeze me where I. sat.

I did not give up easily. I think two days must have passed, but I can only guess the time. I moved about, and rested. At last I could no longer find the energy to rise. I lay still, pressed against the icy floor, gasping for breath. My body cried out for food and strength but they didn't come. Not a sound penetrated the place.

At last I no longer felt the cold or the need of food. I wanted death, and I was conscious only of repeating the girl's name over and over. The vision that name brought to me warmed me. Her arms comforted me in my wait for death.

If I could have heard a sound—just a tiny sound? The stillness was the thing that would destroy my mind. I listened with all the attentiveness I could muster.

Then—long after I ceased to listen, or care, or mouth her name over with my lips, I heard the sound.

He came. The red-headed man came. He wrenched the cell door open and I know I must have looked like a corpse to him as he gathered me tenderly in his arms. He kicked the door open, carried me out of the cell and up and up over what seemed to be millions of dark, stone steps.

I tried to talk and he covered my lips with his hand. I felt the warmth of his big body giving me new life. I remained quiet, closing my eyes, feeling the tears run down my cheeks. Let someone bring you back from the grave and restore life to you from his life, and you would cry also. You would not be ashamed of those tears.

I LAY in the small, warmly covered bed for a week I stared

around at the stone walls and toward the cloth-shaded door, too

weak to move, without any wish to talk. He came often, always

grinning, always happy. He closed the door behind him each time,

locking it carefully, and fed me all the food I could take.

As my strength came back, I knew that this was the red-head's room and that he had me hidden here, somewhere below the walls of the Colosseum. One day I sat up, tried a few steps, and felt up to getting around alone. I talked to him that day. He told me what had happened.

"I saw them drag you down into the dungeons," he said. "I knew you were the one I had saved that day in the Arena, and the one who, in turn, had spared my life." He smiled, that same sincere, brotherly smile I had learned to bless him for. "My name is Tiber Corbalo. I am of Roman blood. I caused certain discomfort for Nero, and he wanted to see me die in a bloodbath. He forgot me in the process of passing time, and fortunately for me, he was not present when you pardoned me."

He frowned.

"The clumsy ox hasn't had cause to remember me since. I have been made a trainer of gladiators. I am quite happy."

"You saved my life," I said. "The score is more than even. You took a terrible chance."

His face reddened.

"You were marked for a slow death," he said. "I waited my time, paid the guards well and took you out of there. No one will be the wiser. The Emperor will never ask them to look for your body. You will be forgotten."

Tiber Corbalo arose and strode across the room. He stood before the door, drew away the covering, and stared out into the torch-lighted hallway. His finely-molded arms were folded across his chest.

"I keep you hidden here. The other slaves dare not enter my quarters, I have certain power here, thanks to you and your pardon."

He pivoted and smiled down at me.

"You must be the very devil with women."

He startled me, and my face felt hot. Before I could interrupt, he went on:

"Poppaea Sabina has been sent to the northern provinces for six months. She raised an awful smell about the whole thing. Dared to swear before the Emperor that you were the first man she ever truly loved." He shook his head sadly. "The girl must have gone mad. She wouldn't have dared say such a thing to Nero if she were sane. Only his great admiration of her beauty kept him from killing her at once."

I hastened to tell him the whole story. I assured him that I had nothing to do with carrying on an affair with the girl.

He shrugged.

"No matter what happened," he said, "I can well imagine her feelings. You aren't repulsive, you know. I've seen many Roman women who would have knifed their husbands for a tug at that curly black hair of yours."

I reached for the nearest heavy object, an earthen bowl and threatened to break it over his head. He made a great show of being frightened and promised not to bother me more with the affairs of the heart.

"You say that Poppaea Sabina is in the north?" I asked after some time.

He smiled.

"She was in the north," he said. "I have heard from certain sources that she has come back to Rome and is in hiding. She, it is told secretly, has tried a hundred times to find a way of freeing you."

Then she was sincere. She hadn't given me up for dead. I felt much better, though I hoped I didn't show it. I hated to go through another episode such as the one Tiber had subjected me to.

I was thoughtful for some time. Finally I reached my decision.

"I've got to see her," I said. "You know nothing of me, save for the fact that I saved your life. You've repaid me for that debt. Now, tell me where I can find the girl, and I'll clear out of here. You can forget all about me."

He shook his head. His face sobered.

"I owe you more than that," he said. "I am safe in Rome, thanks to you. I'll find a way of escape for you. Above all, I will prevent you from seeking the girl again, and in that manner, losing the one chance you have of saving your neck."

I hated to bring him any deeper into the mess. I knew that I could never find my way about the city alone. I had to see Poppaea.

"Bring the girl here," I said stubbornly.

It was the first time I had seen Tiber show fear. It was visible only in the sudden pallor of his face. Then the fear was gone and the color came back.

"Suppose I should manage to reach her," he asked? "Why should she come here with me? It would mean her death if she accompanied me to the Colosseum, and ours as well."

I nodded, realizing that he was right.

"I see that. I cannot endanger you more than I have already."

I had taken advantage of him with those words, and I hadn't meant to. He moved, swiftly to his chest and found a short, keenly-sharpened dagger. He slipped it into his tunic.

"Where shall I say she is to come? Who shall I say wants to see her?"

A wild hope surged through me.

"Tell Poppaea that the owner of the Emperor's Eye believes in her love and needs her at once."

I knew that if she was honest, she would know the message came only from me, and she would not hesitate. Tiber looked puzzled.

"The Emperor's Eye?"

"That will be enough," I said.

He went to the door.

"I will try. I know friends who may tell me where she is. Don't leave this room. The door is bolted. Ignore anyone who comes. I will come back soon—or not at all."

He was gone and the door was closed tightly. I heard his footsteps fade quickly and the room was barren and lonely. I felt as though my best friend had gone to death—for me.

IT was late, and many of the torches had blown out with the

gusty wind that swept down the tunnel. Shadowy figures moved past

the room occasionally, slowly, their feet dragging from fatigue.

It was dark in the room and I had the cloth drawn away from the

door. My face was pressed against the bars. I studied everyone

who approached, my heart beating loud, then soft again when the

one I waited for did not come.

Then they came, two hooded shadows, moving closer together, staying in the shadow of the wall. I stepped away from the door, my heart in my mouth. The door grated open, Tiber came in first, drawing a smaller figure behind him.

"It is she," he said. "I will wait."

He was gone again, out into the corridor, lost in the darkness. The room was hushed. We stood in the darkness, two uncertain, lonely souls, waiting for a thread of understanding to draw us together. Then she was clinging to me and sobbing, and her lips were against my cheek. Tears wet my face. I could almost see the happiness and gratitude that sparkled once more in those violet eyes.

"Then you did not die?"

Her voice was a faint whisper.

"I did not die," I said. "I'm—glad you came. I shouldn't have asked. It was wrong, even from the first."

SHE shivered and held me closer.

"It was never wrong. We cannot help it if we meet, across centuries, and love."

"Then you believe me? You know that I'm not one of your people?"

"I never doubted it," she said. Her voice was stronger now. "We will never be happy for more than a moment. You will go. I will die in misery. I am not so dull that I cannot sense my own fate. Only, never tell me. Never forecast what will happen to me. I'd rather not know. I'd rather spend these few precious moments with you, and remember them regardless of the misery that follows."

There was a bond between us then that no one, Nero, or even the Devil who protected Nero could have broken. It was to me, the brightest morning in the brightest spot in the world. The girl looked refreshed and so full of love and the will to live, that I wondered at the hell she had been through at the hands of the Emperor. Tiber, his hair carefully combed, served our breakfast of finest fruits and seated himself with us to share the feast. The room might have been the greatest hall in the palace, we were so content this day.

Poppaea had come last night in the garb of a slave. The dull, brownish material could not hide the beauty of the girl who sat at my side, her fingers entwined in mine.

"The city is bright, this morning," Tiber said. "Nero is cursing his luck and saying that he'll beat you when he finds you."

Poppaea laughed aloud. I had never seen her truly happy before.

"Let the old fool catch me," she said. "If I am never happy again, I will laugh in his face, for he'll never rob me of the wonderful company I have at this feast."

Tiber arose and bowed low. Then, as he seated himself again, his face sobered.

"Now we must consider plans for escape," he said.

Poppaea pressed a kiss to my cheek and said:

"It is quite simple. We will go north dressed as poor peasants. Once away from Rome, we can make our plans."

She looked to me, and her eyes suddenly reflected the sadness that I had felt since Tiber spoke of escape.

"I have not made you love me," she said accusingly.

It made me miserable, for I knew what she must know, and would not admit. We had both lost this game, and could not win it together. Our paths lay apart. Thousands of years apart.

"I am not free to go as I'd like to go," I said. "We can't escape by running. Fate and time will catch up with us before the tracks grow cold."

Tiber frowned.

"You wouldn't spurn the love of such a lady?"

He was half teasing, half in earnest. Poor Tiber. He knew very little of the problem we were up against.

"Listen to me, Tiber," I said. "Listen, Poppaea. I do not belong to Rome. I do not belong with you. I came from a strange land, many years away. Poppaea knows this in her heart, but she tries to escape from fate. We cannot do that. Through the power of the Emperor's Eye, I came here against my will. Once it was within my power to return, but I fell in love, and would not steal the Eye from Nero and make my escape. I waited too long. Nero has the Eye and I must make another attempt to steal it from him and go back where I belong."

The girl was clinging to me. She sobbed softly.

"I'm not a part of this world," I said gently. "In a manner of speaking, I possess rare magic. I know everything that will happen here in your lifetime, and many centuries to follow. All the paths of your lives have been layed out and recorded in history. I can tell you the time of the births, the deaths, and the wars. I know what will happen to Poppaea when I leave her, I refuse to tell her that, but I promise that she will not suffer many days of pain on earth."

The room was deathly still. Tiber stared at me with great respect and amazement.

"If I tried to stay here, I would be swallowed up and destroyed by the things that happen. By events that have no room left in their pages for me. I would become nothing. You do not believe me. Test me, Tiber?"

He looked awed.

"Predict for us what great thing will take place. If such an event does take place, then I will say you are right. That you cannot fight the power of fate that binds you to the future."

"Then listen. I have counted the days roughly since I came here. If I am right, tomorrow will bring a great disaster to Rome. Tomorrow a great fire will run rampage in the city. It is recorded in that manner. The fire will be set by Nero's hand, though that will never be proven in this time, Nero will set about at once, rebuilding the city according to his plan."

"And if this happens, can it make a difference in my love for you?"

I tried to make myself believe that Poppaea was right. That somehow we could see the thing through. At last I was forced to say that this was not true.

"You are tied into the events of history, Poppaea," I said. "You have a certain path to tread, and I can never take you from it. Fate would destroy me in the matter of days, if I interfere with its course."

An utter calmness took possession for the girl's features.

"Then, if this—this fire comes to destroy the city, I will believe you. Then you must find the Emperor's Eye and you must leave me. Will your love die, when you go?"

"When your love dies for me," I said.

She stood up, wrapping the robe about her closely as though afraid, of the cold. Her face was deathly white and still.

"Kiss me, then, for I leave until tomorrow."

I felt strange, kissing the lips that had been so warm, and were now cold as death.

"And tomorrow?" I asked.

"Let tomorrow tell its story," she said. "Tiber, will you take me to the place from which I came?"

I made no attempt to stop her then. We were both fighting a hard battle, and it was bad enough for her without using more words.

TIBER CORBALO was breathless and pale as he rushed into the

room. I had spent a terrible night, and now, as he sprang toward

me across the room, I put my hands on his shoulders and gripped

them tightly.

"Easy, man. It has happened?"

He could only shake his head in confirmation. After a time, he found his voice.

"The city is in flames. Half of Rome is gone. They say the mad Emperor sits on his balcony, laughing like a fool and enjoying the death of Rome as he enjoys the death of his slaves."

I pushed him back on the cot and waited for him to grow calm. His fists kept clenching and unclenching. He looked at me with fear clouded eyes.

"How—how could you tell us of this. You are a man of magic. You are a God. I did not know I, a low born Roman, was saving the life of such as you. What can I do? How can I do, more to help you?"

The man was half out of his mind. I sat beside him and talked in a quiet voice.

"I am no more a God than you, Tiber," I said. "But listen to me. We will always be friends. Almost brothers. Now I have proven to you and to Poppaea that I have no place under your sun. I have to go back to my time—today, and as soon as I can get that Eye. As long as I stay here, I will bring more misery to all of us. Tiber, take me to Nero. I'll handle him."

Suddenly he sprang to his feet,

"BY THE Gods." he said in a strange voice, "why didn't I think

of this yesterday?"

"There is time enough, if we hurry."

"No, no," he cried. "The noblewoman said something to me when I left her. She gave me a message to give you if the fire came."

I was more excited than he, now, but he blurted out his story before I could speak.

"She said, 'There will be no fire, and my lover and I will flee. But, should the fire come, tell him this. Tell him he need not fear. By the time that Rome has burned half-way to the ground, he will have his Emperor's Eye safely in his keeping. That will be my last token of my love for him.'"

"What did she mean? What wildness was in her mind?"

Tiber had thrown open his chest of weapons and drawn out two short-swords. He pressed one of them into my hands.

"Nero still has the Emperor's Eye," he said savagely. "If Poppaea Sabina tried to present you with that token of her sincerity, she must go to the Emperor. He might kill her with his own hands."

I saw red then. I had learned to fight in this strange world, and now I wanted to fight—and kill. If death came as payment, then I could as well die in this age as in another.

We dashed through the halls like madmen. Once in the street, the pungent smoke choking my nostrils, I followed Tiber closely as he hurried through the rubble toward Nero's palace.

How long we ran, I don't know. We reached the palace, and no one guarded the gates or the halls. Everyone had been sent to fight the fire. Flames arose in all directions, and Rome was a madhouse of screaming, shouting, sobbing....

I FOLLOWED Tiber up—up, flight after flight of stairs.

At last, panting with the exertion, he stopped and drew me back

against the wall, pointing to an open door opposite the place

where we stood.

Across from us, sitting on a finely-wrought divan, and dressed in his finest robes, was Nero.