RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"The Isle of the Virgins,"

Wenborne-Sumner Co., Buffalo, NY, 1899

"The Unknown Island" ("The Isle of the Virgins")

Street & Smith, New York, 1906

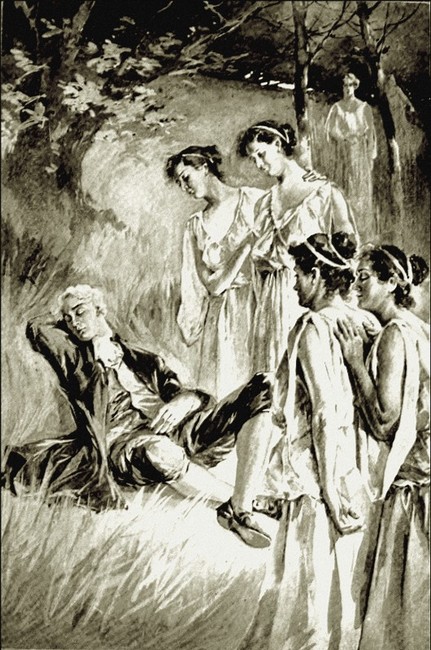

Frontispiece.

"What is it, anyhow?" exclaimed one.

"GENTLEMEN," said the President, concluding his address, which had been closely followed and liberally applauded, "I think we have now but the last step to take—the selection and appointment of a suitable person for that position which Dr. Parkman has demanded to be filled. Four weeks ago I committed to Major Payne the work of searching out a desirable man. He has found it no easy task to get men willing to engage in an enterprise that seems to offer no rewards but hardships, dangers, and, perchance, death. However, he has presented me with the names of about forty candidates gathered from all parts of the United Kingdom, and he is now ready to report. He is, as you are aware, a keen judge of men, and I, for one, am willing to abide by his selection. Gentlemen, what have you to say?"

The President sat down and looked around upon the assembled company, who numbered about a dozen persons. They were all men of wealth, influence, and social position in London. One had been a Cabinet Minister, and, until he had developed a strong tendency toward Radicalism and acquired a general reputation for eccentricity, had stood high in the favor of his Sovereign; another held a title and graced a seat in the House of Lords; while a third had distinguished himself successively as a diplomatist, historian, and archaeologist. The last named was the first to break the silence that followed the President's remarks.

"Do the forty men from whom we are to make our selection know anything of the nature or the object of the expedition?" he asked.

"No," replied the President, "they know nothing beyond the fact that the chosen man must be completely at the service of the Company; that he must, while in the Company's employ, sever all ties that bind him to home and country."

"I do not find it hard to believe that Major Payne had a difficult task," said Lord Fitzwalter in a languid drawl. "Men willing and ready to make that sacrifice are scarce."

"It was not that alone which made it difficult, my lord, but the attributes which this man must possess. My instructions to Major Payne on the point read as follows:

"'Find us a man sound in body and in limb; of intrepid daring and of cool judgment; one that can endure cold, hunger, and fatigue. He must be a person of at least fair education, and of unimpeachable character. He must be quick to decide, resolute when decided, and able to face death, if necessary, without flinching.'"

"I would like to see the man that answers that description," said the Savant, who occasionally indulged in humor. "As you have included most of the virtues known on earth, I should think it would be difficult to find him short of Heaven."

"Yet, Major Payne asserts he has found him," replied the President, "and the Major, as you know, makes few mistakes. He is now ready to present his report. Shall I call him in?"

"Yes," responded each member of the Company, which, as yet, had not seen fit to give itself a name, perhaps, the better to preserve the secret of its existence and doings.

The President touched a bell on the table beside him. Presently a door opened and Major Payne appeared. One glance at the Major's face, with its iron jaw, aquiline nose, and keen gray eyes peering out from beneath their shaggy brows, was enough to convince any physiognomist that its owner was a man of character, as well as a judge of character. He bowed to the members of the company, and, after a few concise preliminary remarks, said:

"Gentlemen, out of forty-two men of whom England may well be proud, I have selected three who might have defended the Pass at Thermopylae, or stood beside Horatius Cocles on the Bridge of the Tiber. You can now make your selection."

"Tell us something about these men," said the President. Lord Fitzwalter and the others leaned forward, with interest depicted on their faces; and, the Major, clearing his throat, began:

"One is fifty-five years of age; served at Delhi and Lucknow, and came out of the Crimean war with honorable scars and the Victoria Cross. The second is also a soldier. He served with distinction in the Crimea, taking part in the famous Balaklava charge, which, in itself, is sufficient proof of his bravery and adherence to duty. The third is a young man who pleases me more by the promise he gives for the future, than by the record he can show of the past. His best recommendation is that he resembles, in every way I can see, his late distinguished father, under whom I had the honor to serve in three campaigns."

"Have you yourself a choice, Major Payne?" asked the President.

"I have, sir," replied the Major promptly.

"You would answer for him?"

"With my life."

"Bring him in please."

Major Payne left the room and presently returned, ushering in a young man, at the first sight of whom every member of the Company rose to his feet in astonishment.

The new-comer was scarcely more than a boy in years, yet the term "boy" could not fittingly be applied to one who had about him such a resolute air of manliness. He was about five feet, eleven inches in height, and of magnificent proportions. He carried himself with a degree of ease and grace that bespoke suppleness and strength. His face, lit up by a pair of dark-brown eyes, was remarkably handsome—women would have called it beautiful—and in it reposed that look of self-confidence that indicates firmness and the will to do and dare. This young Adonis was the man chosen by Major Payne for the above-mentioned position.

"Major Payne," said Lord Fitzwalter, who was the first to recover from the effects of his surprise, "We did not expect you to bring in a beardless youth—with all respect to the young gentleman—to accept responsibilities great enough for a man of iron frame and iron will. We thought you had better judgment."

"Is there any particular virtue in a beard, my lord?" asked the Major, eyeing the nobleman with ill-concealed disdain. "I am not aware that Caesar, Napoleon, or Washington was adorned with a hirsute appendage. At least the cuts I have seen don't say so."

There was silence for some moments; then the President asked:

"Are we to understand that this is the best man you could find in England?"

"I didn't find him in England," answered the Major proudly, "though I searched the country from Cornwall to the Cheviot Hills. This young man is from Dumfries, Scotland."

The Major himself was a good Scotchman.

The members of the Company took no pains to conceal their dissatisfaction and disappointment, and it was some time before the Major could get another hearing.

"Gentlemen," said he gravely, taking no apparent notice of the lack of courtesy their surprise excused them for showing, "you have done me the honor of leaving to my judgment, which you have more than once seen fit to extol, the selection of a suitable person to fill the important post referred to by Dr. Parkman. I have made my choice. Permit me to introduce to you Mr. John Fairfax."

The calmness with which this graceful speech was delivered, the dignified manner of the Major, and the smile that played about the features of the young stranger had a visible effect upon the members of the Company. They looked at one another, and resumed their seats, apparently ashamed of having emerged from their aristocratic impassivity.

"Mr. Fairfax," said the nobleman, "if you knew the nature of the position referred to, you could not blame us for having been somewhat unfavorably impressed by your youthful appearance. It is such that the discretion that comes from worldly experience, and the strength and hardihood that are developed by years of toil and dangers, are absolutely necessary to the successful discharge of the duties involved. Ninety-nine men out of a hundred would shrink from it."

The young man bowed; he did not look as if he felt called upon to speak. The Major folded his arms and regarded with intense satisfaction the bearing of his handsome protégé.

"We feel, however," continued Lord Fitzwalter, "that we are bound to consider any candidate whom Major Payne recommends. How old are you?"

"Twenty-two."

"Married?"

"No."

"In the event of being selected, are you willing to accept this position with all its dangers and responsibilities?"

"So far as the danger is concerned, I am," replied the young man, "but I must know the responsibility attached before I can answer that part of the question."

"We cannot explain the responsibility till you have taken an oath that you will not divulge it or any secret of the Company's."

"I cannot take such an oath, sir, till I am assured I shall be burdened with no secret troublesome to my conscience."

The Company seemed not displeased with this answer. The young man showed himself to be both cautious and conscientious.

The oath was taken. John Fairfax, whether engaged or not, was to betray none of the Company's secrets, unless impelled to do so by conscientious scruples or the demands of honor and justice.

"And now," said the President, "listen. We—the Company—are sending on a secret expedition one Dr. Parkman, Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. The object will be made known to you by him when you have been some days at sea. It is of the utmost importance to the Company."

"Is it in every way a legitimate enterprise?" asked Fairfax.

"Yes. We are known as men who would not engage in anything else. It may necessitate travel in foreign lands, and entail upon Dr. Parkman and those who accompany him hardships and great dangers. Its success depends largely upon Dr. Parkman's living long enough to carry it out. He is an old man, and is far from being robust in health. He is quite unable to defend himself from danger. The man we select must travel with him as his body-guard; he must be responsible for his personal safety. That's all."

"I will accept the charge," said Fairfax.

"Are you willing to pledge yourself by oath to forsake home and country in the interests of the expedition while it lasts?"

"I am."

A half hour's conversation followed. All necessary details were discussed and settled. Then the young man took the following oath:

"I, John Fairfax, do hereby promise to travel with Dr. Parkman wheresoever he may choose to go, until released either by his death or the successful termination of the Expedition. I swear that, so far as may lie in my power, I will protect him from insult and danger. If necessary I will risk my life and limb in his defence."

TWO months later, the Eurydice, a vessel specially fitted up by the London Company, was ploughing its way through a chop-sea in the Pacific Ocean, some degrees South of the Equator. The renowned Dr. Parkman was on board, and with him, the man that had sworn to stand by him in all dangers, and to follow him whithersoever he might lead. The voyage so far had not been unpleasant. The Doctor had his books to interest him—works on geology, astronomy, and navigation, and old classical authors that he perused with avidity; his companion had his pipe to solace him while he lounged lazily about on the deck, and a few works of some of the modern authors to amuse him in the evenings.

Fairfax had tried from the first to learn something of the object of the enterprise from the Doctor, but found him inclined to be very uncommunicative. It was not till they were rounding Cape Horn, where they encountered some rough weather, and the Doctor became so sick that he thought he was going to die, that he was willing to tell anything. Then he gave only an outline of the project and the causes of its being set on foot.

They were in search, he said, of a mysterious island, which as yet, it was supposed, had never been visited by anyone from the known world. Its exact location was not known. Their duty was to find it or perish in the attempt.

This information staggered Fairfax. He could not conceive how the eccentric old man had managed to get English capitalists interested in his visionary scheme. At a period, not far from the close of the nineteenth century, when explorations (except, perhaps, in the interior of the African continent) were a thing of the past, it seemed to him absolutely preposterous that there should be an undiscovered island, however small.

"Tell me, Doctor," said he, as he sat in his friend's state- room, a week later, and watched him eating a supper, surprisingly large for a man claiming to be ill, "what on earth put the idea of this strange island in your head? What proof have you of its existence? You admit that neither you nor anyone else ever visited it?"

"That's so. Pass me some of the chicken—and cut another slice of bread, John—That's it—Thanks."

"Don't you think if there was any such island as you speak of, some of our navigators would have come across it before this?"

"Our navigators, as you call them, John, have heretofore based all their reckonings on the assumption that the earth is round. Instead of circumnavigating a globe, as they have foolishly supposed, they have been wandering around a central point on a flat surface. Outside of that circle that marks the limits of their explorations, there is a world unknown to them. Cut that piece of ham for me, and pass the condiments."

"Good Heavens!" exclaimed Fairfax, as he realized he was the pledged follower of a man who was in all probability crazy. "Are you not a believer in the rotundity of the earth?"

The Doctor shook his head, emitted a surly grunt, and went on eating. His manner so annoyed the young man that he broke out with:

"Look here, Doctor, when I set out on this expedition, I supposed the man I swore to follow was at least sane enough to accept, as the world does, the Copernican System of—"

"Humph! Copernicus was an old fool. What credit the world gives him belongs to Pythagoras and others who derived their knowledge from the Chaldeans, Hindus, and Egyptians. Tho had more sense than either he or Ptolemy, who simply resurrected a doctrine that the Platonists and Aristotelians had believed in for ages, and made an ass of himself with his theory of epicycles. It seems the older the world grows the more easily it is duped."

"I agree with you," muttered Fairfax, thinking of himself and the London Company, and vowing never again to pledge himself to anything blindly.

"If Copernicus is wholly right how was it that Thales, the Milesian, predicted a solar eclipse six hundred years before the birth of Christ? Answer me that, John."

"I know nothing about it," said Fairfax somewhat sharply. He was angry with himself and everyone else.

"We have it on no less an authority than Herodotus, who says that during a battle between the Medes and Lydians—"

"O dear! O dear! It's awful!"

"What?"

"To think I am pledged to act on a theory opposed to all that is established in the most perfect of the sciences."

The Doctor laughed, which was a rare thing for him to do.

"Stuff and nonsense," he exclaimed. "Astronomical science is still in its infancy. We are fated to see the overthrow of many of the popular notions of to-day. We will see, re-established, on conclusive and satisfactory evidence, the theory that the earth is the quiescent centre of the universe, with the sun and the other celestial bodies its servants. John, there are wonderful things in this world of ours that we know very little about."

"I'll admit that," said Fairfax, "but the most wonderful thing to me is how you ever got any sensible men to listen to you—especially a body of conservative Englishmen. It seems like a dream to me that I, who had always been credited with an average degree of common sense, am connected with such a wild scheme. Does anyone else on board know the ridiculous object of our cruise?"

"Yes, the captain and two of the officers, who are, like yourself, sworn to secrecy, and to follow me wherever I choose to go. That gang of rough sailors knows nothing whatever about it. They have agreed to go wheresoever they are commanded and ask no questions. That's all I'll tell you to-night."

The fact that three others knew the secret eased Fairfax's mind a little. They were apparently sensible men and not likely to be led away by delusions. They were all pretty well educated. The Captain, a middle-aged man with a weather-beaten face, was Dr. Parkman's brother. He was a good seaman, a strict disciplinarian, and, when not engaged in his duties, a jolly sociable person.

The project did not now seem quite so foolish, though it was not exactly the one to recommend itself to sensible, practical men. All were sworn not to return till the expedition ended successfully or Dr. Parkman died.

One evening, two months from the time Fairfax entered the service of the Company, he approached Captain Parkman, who was sitting on the deck, enjoying a smoke, and watching the bounding, heaving mass of waters about him.

"Captain," said he, "the Doctor has told me the object of our journey, and has sent me to you for further particulars. Will you tell me how he got the idea there was any such island not yet known to the civilized world?"

"Yes. Come alongside," answered the Captain, "and I'll reel it off. Two years ago this summer, my brother and I were aboard a vessel bound for Hong Kong. When we were in a certain place—"

"Whereabouts, Captain?"

"Never mind, boy. You'll learn that, perhaps, later on. One evening the Doctor and I were sitting together on the deck, just as you and I are now. It was a calm evening in July; not a ripple on the water and scarcely the suggestion of a breeze. We were talking of one thing and another, the beauty of the night and so on, when, of a sudden, the Doctor grasped my arm and exclaimed:

"'Look! Look! In the Northern Sky!'

"I looked where he pointed, and leaped to my feet in astonishment too great for words. It was the most wonderful sight I have ever seen. There, in the northern sky, as distinct as on a map, was the picture of an island, with the outlines of its hills, valleys, and rivers discernible."

"A mirage!"

"Yes. It was oblong in shape. Near it was another island, perhaps one-twentieth as large. I had read of these mirages before and was skeptical. I had met sailors who affirmed they had seen portions of countries, hundreds of miles away, reflected in the sky. One man, whom I have always regarded as a truthful person, has told me that, on an occasion when he was on a sailing vessel in the Levant, he saw a picture of the City of St. Petersburg in the heavens. By the aid of a strong glass he identified the Neva with its bridges, the Arsenal, the great Fortress of Peter and Paul, and the Imperial Palace. Another has told me that when sailing south of the Azores, through the Sargasso Sea, he and others saw the outline of the southern portion of the Scandinavian peninsula reflected distinctly in the sky. He recognized it the more readily on account of a part of Jutland being also visible.

"Well, when the Doctor and I saw this island, we were anxious to get an idea of its size and location. It is hard to judge the distance of an isolated object in the sky, for the eye has nothing to help it—no intervening object from which to get an idea of its relative position."

"Why did you not use your telescopes?"

"I was going to tell you that we did so," replied Captain Parkman, "and we had reason for still greater astonishment; for lo! the island seemed so close that we could quite distinctly see some of the objects upon it. The Doctor, who is a man of extensive knowledge, believed it was within a radius of a few miles from our vessel.

"There was a piece of country, perhaps forty by twenty miles in area, the most beautiful I have ever seen. Two small rivers flowed from a ridge of hills that ran the entire length of the island, and there was a number of towns and villages, of which two were much larger than the rest.

"The Doctor went in for details, while I studied the general appearance. The result of our joint survey was a map, hastily drawn while the impressions were still fresh in our minds. The Doctor still has this map in his possession; it is necessarily a crude and imperfect sketch. He fixed his vision attentively on the largest town, and declared it surpassed, in grandeur, ancient Rome. He asserts that, in a large square in the centre of the city, was a monument or obelisk that appeared to be of gold. He drew my attention to it, but, before I could focus it, the mirage vanished, and, shortly afterwards, the sky was darkened by clouds, and a terrific thunderstorm raged for an hour.

"I was not a captain then, and had no authority, but I managed to ascertain an approximate idea of our latitude and longitude—a fact which my brother and I have ever since kept secret. When we returned to England we made known to the men you saw—the Company—sufficient to interest them in the organization of an expedition for the purpose of discovering this remarkable island, and the good things it may contain. We are of the belief that it is peopled by a strange race of beings, who are, perhaps, as ignorant of the existence of any other world as we are of their several names."

Fairfax thanked Captain Parkman for his information, and walked away, his mind filled with strange and worrying thoughts. The whole thing seemed ridiculous. A company of English aristocrats, with more money than brains, and more credulity than either, had fitted up a handsome vessel, and provided Dr. Parkman with the means of searching for an island which Fairfax believed existed only in the old man's vivid imagination. True, the Captain corroborated the story, and he appeared to be a sensible fellow; yet he was the Doctor's brother, and this, in itself, was sufficient, in the eyes of an unprejudiced person, to throw some doubt on his sanity. Besides, as likely as not, he had been half full of grog on the occasion of the alleged mirage.

As for the officers and the sailors, it was easy to account for their being in the expedition. The assurance of good pay, and the promise of rich rewards in the event of success, would scarcely be needed to make them jump at any enterprise offering excitement, some danger, and comparative idleness.

Fairfax was sorry he had come. He had never dreamt of such a wild-goose expedition as this. He had supposed it was some sensible enterprise from which he could, by his talents and the faithful discharge of his duties, reap commensurate rewards. Instead of that he was pledged to follow the Doctor wherever he should choose to go, which might be anywhere, considering he was so easily led by his whims. It was a serious situation. The life of John Fairfax was too precious to be wasted in an attempt to find an island which a crack-brained old scientist claimed to have seen in the sky!

THESE considerations did not make young Fairfax think, for one moment, of shirking his duty. He was determined to stick to his charge through thick and thin; and, so conscientious was he, that he deemed it his duty not only to go to his aid in absolute danger, but also to see that he was shielded as much as possible from minor discomforts. Though, as yet, the Doctor's movements were circumscribed by the limits of the boat, the love of exploring, inherent in his nature, prompted him to push his way into all sorts of nooks and corners. He was as restless as a child. Wherever he saw an effect he sought to find a cause, making every one about him uneasy till his curiosity was satisfied. A marlin-spike was a fit subject for a metaphysical dissertation; a carelessly-dropped nautical expletive was sure to draw forth a lengthy homily bristling with classical quotations. The sailors were a rough lot, despite the fact that most of them had been selected on the strength of testimonials covering other good qualities than mere indifference to danger. They did not like this spirit of enquiry in the old man. He asked too many questions, they thought, and interfered altogether too much with them, their work, and their amusements. They first showed their dislike by chaffing him, and, as he took this with bad grace, being a surly old fellow, they began, by and by, to play rough jokes upon him, blaming them invariably on the cabin-boy, Butt Hewgill, who was anything but a practical joker. This got the Doctor down very severely on the harmless Butt; which encouraged the sailors to go to further lengths, till, at last, Fairfax was obliged to interfere to save both the Doctors dignity and Butt's body.

As a consequence, Fairfax became very unpopular with the jokers, and, as he took no pains to conciliate them, they did not try to hide their dislike. One of them, in particular, became very inimical toward him, and did his best to engender the same degree of hatred in his companions. He was Mart Boxall, or "The Terror," as he was commonly called. He was a man of large stature and wonderful strength. He was some fifteen years older than Fairfax, and was a terror in the full sense of the word. There was scarcely a man on the vessel that did not stand in dread of him, when his anger was aroused, which was quite often. He was by nature a bully, and, as he knew the fear in which he was held, he availed himself of every possible occasion to pick a quarrel and develop it into a fight.

The Captain had a knack of getting along peaceably with him, and so had Maloney, an Irishman, who usually cajoled him into good humor by the exercise of his native wit and blarney; but both took care to avoid him as much as possible.

Several times since the expedition began, the Terror had made remarks in the hearing of Fairfax that were calculated to excite his anger, but his good sense forbade him to notice them. He considered himself bound, by his pledge, to sink all thoughts of self, to swallow insults, and submit to personal inconveniences for the sake of Dr. Parkman. To involve himself in danger, by yielding, for a moment, to pride, was, he deemed, an act of infidelity to his charge.

Boxall, seeing he could not aggravate the young man in this way, and stung to madness by being quietly ignored, sought to do him harm by lowering him still further in the eyes of the sailors.

"Mates," said he, "Fairfax is a swell as holds his head too high. He thinks you an' me is too far beneath him to be noticed. A lubber as feels he's too good for the company of gents wants to be taken down. Eh, lads? What do you think?"

The sailors acquiesced in this opinion, and expressed themselves as eager and happy to witness "the taking down" of any young man whose ideas were too exalted. They were ready to approve any doctrine that partook of a democratic spirit, especially when promulgated by a man so willing and able to back his arguments by physical force.

"We'll show him an English swell ain't no better'n us. Eh, mates?"

"Ay, Ay, Boxall," came the response from the crowd, and the Terror sat down with the same feeling of satisfaction as Marc Antony experienced when he heard the Roman populace take up the cry, "Death to Brutus!"

Fairfax had sufficient penetration to see he was held in no very high esteem, but he bothered his head very little about it. The sailors were no fit companions for him, being, for the most part, bad and dangerous men, and he kept aloof from them as much as possible. But he found it necessary occasionally to go among them to look for the ubiquitous old Doctor, whose sour tongue and temper were forever getting him into trouble.

One evening he went below and found the Doctor, as usual, finding fault and interfering with the men. He wanted them to carry on their sports after what he considered to have been the manner of conducting the Olympic games of Ancient Greece, and he was eager to teach them a rare style of wrestling that, he claimed, was introduced by Iphitus, King of Elis.

Fairfax knew this was just what the sailors wanted, as it served them with grounds for playing their rough pranks upon the old man. Conceiving it his duty to see his charge suffered no indignity, he went up to him, and taking him gently by the arm, said:

"Doctor, come up above and leave these men alone. You have no business down here. You're in the way."

"He ain't," cried Boxall, glad of the chance to drag the young man into trouble. "Leave the old gent alone and mind your own affairs. He's just watchin' our sport."

"I supposed he had been bothering you by the way you were treating him," said Fairfax quietly.

"No, not a bit. He's perfectly welcome. Sit down yourself an' watch the fun if you think our company ain't a little too low for you."

Fairfax appeared not to notice that the speaker's tone and manner, no less than his words, conveyed the deliberate intention of insulting him. He sat down with a look of perfect good-nature in his face, and laughingly said:

"Oh, I guess I can stand your company a little while; but don't let me interrupt your games."

There are certain events in our lives that appear trivial till we view them through the vista of years, when they assume an importance that surprises us. We find, perchance, they have been potential in shaping our destiny. We would gladly spare the reader a narration of the incidents that followed—we would overlook them as unimportant—as mere episodes of common occurrence among sailors—if it were not that they produced great effects. Boxall's invitation to Fairfax, simple as it was, had a direct influence on the life and fortune of every man aboard the Eurydice.

"Do you ever do any jumping?" asked the Terror.

"Not much," replied Fairfax, "but go on. I like to watch."

Having drawn the Doctor down beside him on the seat, he watched the sailors as they vied with one another in leaping and other feats of agility and skill. Then they got to wrestling, and he noticed there were several fine athletes among them. So far as muscular development and size were concerned, it would be hard to bring together a finer lot of men. But Boxall was by far the best. For strength and activity he was a wonder. He contended with two big, powerful sailors at once, and, in less than a minute, threw them both.

After awhile they commenced lifting heavy weights. Several among them proved themselves able, with one hand, to raise, upward from the shoulder, ten times, a hundred-pound weight, and two or three shouldered, with apparent ease, a sack weighing nearly three hundred pounds. But Boxall surpassed them all. The hundred-pound weight seemed like a cricket-ball in his hands, and he shouldered weights the others could scarcely move on the floor. Maloney was a powerful man, too. He succeeded, after a great struggle, in raising a nine-hundred pound weight a couple of inches from the floor. When he accomplished this the sailors broke into cheers, and Fairfax, ever ready to applaud a fine feat, clapped his hands also. This pleased the good-natured Maloney, but aggravated the jealous Boxall, who turned to Fairfax and said: "Let us see you lift it, sonny."

Fairfax shook his head to decline the invitation.

"Then don't crow so much. Come here Maloney. Sit down."

Maloney approached and sat down on the very weight he was after lifting.

"Now," exclaimed Boxall, "will any man here wager I can't lift him and his load?"

"I will," shouted the aggressive Doctor Parkman, rising suddenly to his feet.

"Keep quiet, sir," whispered Fairfax, pulling him back on to the bench. "Go on Boxall. He didn't mean it."

Boxall bent his gigantic frame, and, placing an arm each side of Maloney's knees, seized the iron block. All breathlessly awaited the result of the trial. Slowly, slowly, as the veins on his Herculean arms stood out like whip-cords, the weight was seen to move, and, a moment later, it rose fully six inches from the floor! Maloney got off it, and Boxall walked two steps forward and laid it down so gently that it made little or no noise.

A burst of applause, in which Fairfax heartily joined, followed this marvellous feat, and the Doctor was beside himself with excitement. Nothing would do him but he must try to lift it too, and Fairfax had hard work to restrain him. The sailors, seeing a chance for fun, did all they could to encourage the old man in his foolish attempt, and Fairfax remonstrated and expostulated.

"Let him try it, swell," said Boxall. "Mebbe you an' him can lift it. Give him a chance."

"I will not," said Fairfax, ignoring the personal insult. "He is liable to kill himself."

Quite a scene followed, but Fairfax managed to get the meddlesome old Doctor up-stairs and into his state-room.

Half an hour later, as he was lying on a bench on deck, he heard a footstep behind him, and a voice whispered in his ear:

"Mr. Fairfax."

It was the cabin-boy, Butt Hewgill. His right name was Robert, but the sailors had given him the euphonious name of Butt, partly because of the likeness of his figure to a cask, and partly on account of his fondness for adversative conjunctions, as shown in his readiness to argue. He was about fifteen years old, but was almost as large as two boys of that age, being enormously fat. Standing at a distance, he could easily be mistaken for a small vat, or a sack of meal. Once the sailors tied a rope around him, threw him overboard, and hauled him out again, pretending they mistook him for one of the large water-buckets. He had a plaintive, whining voice, and a very melancholy cast of countenance. There was not a trace of conscious humor in him, and yet he rarely spoke without exciting laughter in others, for, the more serious he became, the more comical he looked. His favorite pastime was reading; his favorite author, strange to say, the immortal Shakespeare. He had got hold of an old volume of the bard's works somewhere, and he pored over its pages at every possible chance. The interest he took in passages far beyond his understanding, and the ease with which he could quote apt speeches were surprising.

Fairfax's first inclination, when he saw the massive figure beside him, was to laugh, but he modified it into a smile when he saw Butt's rotund face. It contorted into various comical expressions indicative of a desire to excite secrecy and caution. Putting his band to the side of his mouth, the lad whispered:

"Mr. Fairfax, you're in danger!"

"In danger, Butt! Nonsense! You must check those wild flights of imagination."

"But I'm serious, sir."

"Yes, you look serious. Go on."

"The men have sent me up to ask you to come down and act as referee for them."

"What are they doing?"

"They're going to have a friendly boxing match, they say—but—don't go down, Jack," as he saw the latter rising. "Don't go down; methinks they mean to do you harm."

"Harm! Nonsense."

"Yes; they'll use you well for awhile and pretend to show you respect as referee, but they mean to do you mischief."

"How do you know?"

"I heard them when they didn't think I was listening. There's some of them great fighters, and I saw Boxall split a board with his fist. Some say he once struck a man and killed him. They have it made up to get you in among them, and coax you to put on the gloves with some of them. They'll let you win for awhile; they'll pretend you're whipping them, and then, just when you think you're a fighter, Dick Smithers says either he or Boxall will pitch in and pound the life out of you."

This was just what the rough sailors proposed doing. They were going to have some fun with the "English Swell," as they called Fairfax. Not one of them knew the capacity in which our hero stood. Why he was with the expedition had been a subject of much speculation on their part. They had seen the Captain and the officers show him considerable deference, and they had seen him lounging around as if entirely free of responsibility. They were forced to the conclusion he must be a friend of one of the aristocratic members of the Company sent out to act as a spy upon them.

"Don't go down, sir. Don't go down," pleaded Butt.

"Yes, I will. Come along. They won't harm me."

Down-stairs stepped Fairfax, followed by the quaking Butt, whose piteous, but suppressed, lamentations previous to the event showed just how bad he could feel if harm befell the young man that had befriended him.

THE only one of the sailors that protested against the proposed "fun with the swell" was Maloney. He was a warm-hearted Irishman, quiet as a lamb if people let him alone and behaved themselves; brave, and as fierce as a lion when aroused. Like many of his countrymen, he would put up with a great deal more himself than he would stand to see others suffer. He was a fine specimen of manhood, being over six feet in his stockings and proportionately built. Though not so strong as the Terror, whose marvellous strength we have seen, he was nevertheless as good as two ordinary men, and, when aroused, was able and complaisantly willing to contend with half a dozen. Numbers seemed to affect him only in so far as they increased his interest in the contest.

He was liked by all the sailors except the Terror, who, because he could not cow him as he did the others, felt bitter toward him. The Terror was feared rather than liked; had this fear been removed there was probably not a man on the vessel that would have followed his lead, because he had qualities that even bad men dislike. But fear being one of the great motives by which men can be influenced, Boxall held greater sway over the crew than Captain Parkman.

Maloney knew what was in store for young Fairfax if Boxall got him in his hands. He believed the brute would try to kill him by a blow or by crushing him. From a love of justice and fair play he argued with, and appealed to, the men, but was overruled by the influence which the Terror brought to bear on them.

Just as Fairfax, followed by the lugubrious Butt, stepped smiling down the hatchway, Maloney was called away to do duty at the wheel. This was unfortunate, for the chivalrous Maloney had made up his mind to defend the young man if it cost him his life.

"Fairfax," he whispered, as he was passing, "for God's sake turn back. Go above beyant. Thim divils has it in them to do you mischief."

"O I don't think so, Mike."

"Listen to me avic. That divil Boxall 'll kill you. He's taken a dislike to you, an' has incensed the others—the blackguard. Come back boy. Come back. Follow me."

He looked over his shoulder as he passed and made comically earnest gesticulations of warning and coaxing, but Fairfax did not follow. The daring young fellow, laughing the while, threw a piece of rope after Maloney, and sauntered down toward the sailors.

It was not that he was without fear the sailors meant mischief, but he thought the time had come to correct some of the erroneous impressions they had formed of him. The word "Swell" stood for a good deal with them. It embraced nearly all the qualities such men dislike. Fairfax understood the significance they attached to it, and believed he had only to display a little courage to dispel their repugnance to him. He considered that, in all probability, these men were destined to be his companions for years, perhaps for life, and sooner or later, it must be decided just how he was to stand among them. To show fear, by remaining above, would only intensify their dislike. He must prove to them he was no coward. He must enforce their respect at all hazards.

But no thought of self influenced his decision. Since the day he took his oath he had viewed everything from the standpoint of Dr. Parkman's interests. So far as he was personally concerned, he cared not what the sailors thought of him. He would have avoided the danger he now saw confronting him, and lain under the imputation of cowardice, if he had hot been certain it meant a series of troubles for his charge. Humiliation for himself meant insecurity for the man who looked to him for protection.

This was the first danger that arose from his conscientious regard for the duties of his position. He was fated to meet many more; but none productive of such far-reaching results. The events of the next ten minutes had a direct influence on the future of every man connected with the enterprise, from the solemn-visaged cabin-boy, Butt Hewgill, to the pompous President of the London Company.

"Soft you, a word or two before you go, Mr. Fairfax," said Butt, tugging at Fairfax's sleeve in the excitement of his fear.

"Keep quiet, Butt. You'd better go above."

"No, no! I'll stay with you, Mr. Fairfax," and the lad, his faithfulness serving the place of courage, followed in the rear.

The sailors were congregated in the forward part of the ship between decks. They were exchanging sundry expressive winks and smiles, when Fairfax walked up to them and quietly said:

"Well mates, what's up? Some fun, eh?"

"You bet," replied Smithers. "We're goin' to have a little impromptu jollification among ourselves—on the quiet—d'ye see?" and he glanced at several of his companions and conveyed signs he little guessed Fairfax understood.

"And you want me to be referee, eh?"

"Yes, we thought it well to get some great person as could look away up into the clouds, an' give impartial decisions. Do you see?"

"Perhaps I don't know enough about the game for that."

"O you'll learn," said Boxall ironically. "Anything you don't know we're willin' to teach you. Eh lads?" and he winked at the sailors.

"Ay, ay," came from all sides.

"All right then mates," said Fairfax, coolly taking a seat on top of a cask, "I'm master of ceremonies now and I must be obeyed. Sit down you fellows, and make room there for the contestants."

The men, a little surprised by his sang froid, seated themselves around in a semi-circle, and Fairfax called upon the first pair of boxers.

Two young sailors stepped out, and, putting on a pair of rather hard gloves, began to spar. They pummelled each other in a kind of good-natured way for some minutes, and one of them dropped, pretending to be beaten.

"I award the fight to Potter," said Fairfax.

"No you don't," yelled a dozen voices, and every man with well-feigned anger rose to his feet, "Give square decisions. Smith won."

Fairfax understood their base purpose. They intended in concert to dispute every one of his decisions, as a means of bringing about the real "fun." Even Potter, the victor, joined in the chorus of dissent.

"Change that decision! Take that back!" shouted several stalwart fellows, as they advanced threateningly toward our hero.

"I'll take back nothing," replied the latter coolly, drawing a revolver and levelling it upon the foremost of them. "Stand back. I'll shoot the first man disputes the referee's decisions. Next couple come forward."

He spoke laughingly, as if he understood they were only joking, but there was firmness in the tone of his voice. Surprised as they were, they were cunning enough to make pretence of joking also, and, with loud laughs and coarse jests, they sat down, giving a mock cheer for the swell referee. The young fellow's conceit—they had not yet come to regard it as courage—only served to heighten their amusement, and produced in them glowing anticipations of the coming "fun."

Fairfax put away the revolver and called for order. All became silent, pretending to hold the referee in awe, but that worthy did not fail to notice the glances and winks, pregnant with meaning, that passed from one to another.

Boxall and Smithers stepped out, and after bowing to the referee, donned the gloves, shook hands, and began to box. Fairfax watched them closely. They purposely made the most awkward movements. Two schoolboys could not have shown less skill. Smithers would strike Boxall and run away a few steps. Boxall would follow, give him a cuff, get one in return, and afterwards pretend to have been knocked down by a blow. It was easy to see through the trick. Both were expert boxers and able to compete with the best trained athletes. Boxall, besides being skilful, was as active as a kitten, and could fell an ox with a blow of his fist.

"A draw!" said Fairfax when they had concluded. There now followed a silence such as portends a storm. Smithers was the first to break it.

"Did you ever have the gloves on, Fairfax," he asked carelessly.

"A few times," answered the young man.

"Come and try them on with me."

The big bully spoke with affected friendliness and innocence, while the men around him tried hard to keep their faces straight.

"O no, no," said Fairfax, pretending to be much more afraid than he was, "not with you Smithers, not with you. You're nearly as good as Boxall. You might hurt me."

"Pshaw! He won't hurt you," growled the Terror. "Go on. It's just in fun."

Fairfax yielded, at length, to the sailor's entreaties and assurances he would not be hurt, and put on the gloves. Just as he had expected, Smithers played a deceptive game. The brute twice pretended to have been knocked down when he had been scarcely touched, and each time he complimented Fairfax on his science.

But he had not seen Fairfax's science yet, as the latter was playing a game also. He made the wildest passes and movements,—some of them so awkward that the spectators fairly shook with laughter.

It was great sport, this playing with an "English swell." If they had only known it, Dumfries, Scotland, sends out very few swells, but quite a number of sinewy, cool-headed fellows that have a happy knack of taking their own part; and, within the last year, she had sent out a man who had vanquished all Scotland in the Caledonian games.

The two sparred in this manner for some time, and at last Fairfax saw, from a wicked gleam in his opponent's eyes, that the moment had come.

It came even sooner than he expected, for he got a stunning blow between the eyes that laid him on his back, and started a howl of laughter that could have been heard two miles away. But he was on his feet again in a moment, cool and smiling as before, and approached Smithers, who exclaimed:

"How do you like that, eh?"

"He can stand a blow," whispered Boxall, who knew just how hard it was to smile after receiving such a crack.

Smithers, dropping the mask at the request of the sailors who were getting impatient to see the fun, now pitched in, and dealt several quick and heavy blows, which, a little to his surprise, and the surprise of the spectators, were rendered ineffective by some very clever parrying and dodging; and the first thing he knew he got a pretty hard tap on the nose that drew the blood. He made a vicious rush and got a second blow that caused him to stagger.

Just at this moment the tall form of Maloney appeared, and his manly voice rang out:

"Stop this you ruffians! Would you kill the poor boy? Fairfax leave that man alone. He's too much for you."

A dozen voices rose in protest, and Boxall gave Maloney a terrible look of hatred.

"See here mates," said Fairfax. "Before we go any further I want to tell you something. Stand back Maloney. Smithers isn't going to hurt me."

"Of course not. Go on with the story."

All waited in breathless silence, wondering what the "swell" had to say.

"Quick," said Boxall, exchanging winks with the others. "Spit out your story quick, for I'm going to give you some lessons in the manly art."

"Well mates," said Fairfax, "I've been for the last three days pondering over a question. It seemed to me to be necessary I should do a certain thing. About an hour ago I settled it. I made up my mind I'd do it or die in the attempt."

"What do you mean to do?" asked the crowd.

"I mean to thrash Boxall just as soon as I have got through with Smithers," was the calm reply.

IF a thunderbolt from a serene sky had dropped down among them there could not have been a greater look of astonishment on the faces of these rough sailors. They stood speechless, looking at the slim, dark-eyed young fellow who had the audacity and foolhardiness to stand within six feet of "The Terror" and calmly proclaim his settled intention of chastising him. All interest in Smithers, as an active participant in the scene, died out in that moment. He was as effectively relegated to the back ground—nay, plunged to the depths of subordinacy—as if he had been thoroughly whipped. The challenge, flung at the feet of the recognized champion, Boxall, simply robbed Smithers of his individuality. He seemed to be impressed with this notion himself, for, after staring a moment at the dumbfounded crowd, he pulled off the gloves, withdrew to a little distance, and began to wash his bloody face.

For some moments not a word was spoken. The scene was too dramatic for words. The sailors stood stock-still, as if they realized that speech and action were, for the time, exclusively the prerogatives of the two foremost figures of the picture. Incredulous surprise may express itself in shouts; silence alone is compatible with such astonishment as was depicted on their faces.

The young man certainly meant what he said, for there he was, taking off the gloves, his coat and vest, and tightening his suspenders in the form of a belt around his waist. He threw aside his cap, collar, and necktie, as if he were going to take a bath, drew a ring from his finger and put in his pocket, and, advancing to Maloney, said in a voice loud enough for all to hear:

"Maloney, I'll trust you to see I get fair play. There's a man on this boat that I'm going to thrash or he'll thrash me. I'm going to whip the Terror till he cries 'mercy', or get killed in the attempt."

Maloney drew him aside and tried to dissuade him from his mad undertaking. He whispered in his ear a dozen warnings of Boxall's almost superhuman strength and fiendish nature.

"There are no ten men on the boat that could overpower him, Fairfax," he said. "You'll be killed if you go within reach of him. For God's sake don't attempt it. Take the advice and warning of a friend that would stand by you through thick and thin—one that knows what the Terror can do."

Reasoning and advice were of no avail. The demon of rage and determination had taken such possession of Fairfax that he quivered from head to foot. The look in his face almost frightened his friend.

"Mike," he whispered, "it is too late to retreat now. Besides I've got to do my sworn duty. If this man is allowed to go unchecked, he will be a living menace to Dr. Parkman's safety. I may get badly thrashed, but, if I make anything like a good fight, it will diminish Boxall's dangerous influence on the men."

Half a dozen helped the Terror to strip, and, when he stepped out and displayed his massive figure, there was scarcely a man present that did not expect to see Fairfax a corpse in less than a minute. That individual, however, appeared more unconcerned than ever, for there was not a tremor in his voice as he said in a clear, loud tone:

"Boxall, you will understand that this fight is to continue till one of us acknowledges he is beaten. I ask no quarter and I'll give none."

"Agreed," cried Boxall, and his jaws snapped together, while his face assumed an expression truly diabolical.

Smithers and Maloney were chosen to act as seconds. The latter's parting injunction to his principal was given with tears in his eyes.

"My boy," he said, "beware an' keep out of his reach. He'd crush the life out of you. He's got a peculiar grip they call 'The Terror's Clinch' an' no man ever came out of it alive. Look out for his blows too. They're death."

Fairfax squeezed his hand and whispered some words in his ear. Then he leaped lightly to the centre of the cleared space, where Boxall was awaiting him.

They faced each other amid a silence that was broken only by the splashing of the water against the vessel's sides, the noise of the officers on the deck, and the piteous whining of poor Butt Hewgill, who lay concealed behind a pile of luggage.

While they stood eyeing each other and waiting for the word, there was opportunity for the spectators to note their disparity in size, and to form conjectures as to how long the young man could possibly live before such an antagonist. The Terror had the advantage of nearly a hundred pounds in weight; he was fully four inches taller than Fairfax, and was so much larger that it seemed as if Fairfax could have stood behind him and not been seen. His lower limbs suggested the idea of two Norwegian pines; while his arms, with their great knots of muscles so prominent, resembled limbs of oak. He was a veritable giant.

But Fairfax, stripped, was a picture,—a picture that would have delighted the eye of a Titian or a Corregio. He was tall and slim, yet of compact build. Every graceful curve of his limbs bespoke agility and strength. His face was now pale, but it was the paleness that arises from a determination to do or die rather than the pallor of fear. To all appearance, he was as calm as if he were about to take some simple exercise. Only his eyes betrayed the spirit within him; they blazed with a fierce and wicked light. He looked like a young Roman gladiator who had entered the arena to face fearful odds and die—a victor in death.

"All ready. Set to," shouted Smithers, and the contest began.

For the first few moments it looked as if Fairfax was afraid of his opponent, for he dodged his rushes, and ducked his head to avoid the blows, anyone of which would have sufficed to kill an ordinary man. But, when two whole minutes had passed, and Boxall had failed to inflict even a scratch on him, his clever dodging was regarded as the essence of good tactics rather than as a sign of fear. As yet he had not tried to deliver a blow.

Suddenly Boxall made a wicked rush and his heavy right first shot out like a piston-rod. Fairfax was quick enough to avoid the blow, but, in leaping aside, he tripped and fell, and before he could get to his feet Boxall had grappled with him.

"Heavens, Fairfax, be careful," roared the stentorian Maloney, who thought his friend must surely perish in the grasp of a man who could easily handle one thousand pounds.

Fairfax succeeded in getting the best hold; he got his right hand on the Terror's throat. The two fell to the floor, and rolled over each other several times, which brought them near an open hatchway leading to the hold. The crowd saw the danger and shouted a warning, but it was too late. The combatants, locked tight in each other's embrace, rolled over the edge and fell down the hatchway.

The fight was ended. Accident had helped to decide the issue. When the sailors looked down into the hold they saw Boxall lying on his back senseless, and Fairfax kneeling by his side. The latter was unhurt.

Boxall was still senseless when he was taken out, but he revived shortly afterward, and was able to walk about, apparently little the worse for his fall. He showed no inclination immediately to resume the fight, but he hurled, at the head of Fairfax, the threat that he would yet get even with him.

"And mark my words, youngster," he concluded, "when we next fight one of us will be crushed."

He spoke the truth.

Of all the things of the world that man values there is none more unstable in its nature than popularity. The minds of men are as easily influenced as the waters of the ocean, which can be stirred to its depths by the dropping in of a pebble. Yesterday Boxall reigned supreme by the force of the terror he could inspire among his shipmates. He was now no less abject than the once mighty Napoleon when he first touched the shores of St. Helena. His fall was as complete as if he had been whipped, for he had been defied, and had failed to overthrow the issuer of the defiance. His prowess was in question so long as young Fairfax remained unthrashed.

As for the latter, he was content to let matters remain as they were. He could gain nothing by taking advantage of Boxall's temporary weakness. He saw he had risen in the respect and esteem of the sailors, and he knew that, for the future, Dr. Parkman would be safe from their annoyances. He told Boxall he would meet him in fair fight any time he desired, and then, in company with the gratified Maloney, he walked off, showing the same carelessness of manner as he had from the beginning.

The Eurydice ploughed on through the waters of the ocean at a speed that would have been satisfactory to the sailors had any particular port been in view. Paradoxical as it seems, sailors enjoy the water more than the land, and yet the greater part of their pleasure at sea is derived from the joyful expectation of reaching port. Now there was no particular destination, and this, together with the fact that the Captain and the officers carefully kept secret the object of the expedition and the reckonings, filled the crew with dissatisfaction that gradually sought an outlet in murmurs. Boxall and Smithers did all they could to stir up dissension. They showed the men the injustice that was being done them. They were being kept in complete ignorance of the position of the vessel and of its course. If anything were to happen the Captain and his officers, the crew would be left alone, in a great ocean, without the knowledge necessary to navigate the ship.

About a week after the fight, Maloney sought out Fairfax and drew him into conversation.

"My boy," he said, "if you have any influence with the Captain, you ought to whisper a word of advice in his ear. The men are gettin' dangerous. They don't like the idea of sailin' around, at the whim of an ould Doctor, who growls instead of spakin', an' talks of nothin' but first principles an' parallaxes, an' nebular theories, an' such things. Can you do anything?"

"It's not my place to interfere," answered Fairfax. "I am as ignorant of our whereabouts as the men themselves. My grievance is just as great, but I gave my word to follow and obey."

"Bedad an' I'll let the men know this. They were under the belief you were in the Captain's confidence. Whereabouts do you think we are?"

"I don't know, Maloney. I am a poor sailor, but for several days I have been studying the signs with a view to making a guess."

"Well?"

"I think we are still within the Tropic of Capricorn. The uniform westerly flow of the waters, the altitude of the sun, and the temperature show that."

"Are we near South America?"

"That I cannot say, but I think not. I have noticed many times, and especially at night, that our course has been changed. The sailors might have noticed it too, if they had not been taken up so much with criticising the Captain. We are, I believe, cruising about in mid-ocean."

"Well, mark my words, Fairfax, there's somethin' goin' to happen. The divil's in Boxall since you gave him the set back by darin' him. He won't spake to me at all, not even to pass the time o' day."

This was true. Boxall was filled with feelings of resentment and malice. He tried to foment a mutiny among the men, and would have succeeded, but that Maloney assured them Fairfax was as far from knowing the Captain's secret as themselves. This set Boxall against the sailors and everyone else. For several days he went about in a sullen manner, refusing either to do his work or to speak with any one. In his heart he was determined upon revenge. Fairfax tried to make friends with him, and got a look of hate that, had it the power to kill, would have blasted him on the spot.

One evening the Captain, his officers, the Doctor, and Fairfax were seated together on the deck, discussing the question of what was best to be done with Boxall. All agreed that danger was imminent, if steps of precaution were not taken. The Terror was no ordinary man. He had a mind capable of conceiving any wickedness, and a will that would stop at nothing. He was plainly under the impression he was a misused man, and his black looks eloquently told he would brook no real or imagined wrong. One of the officers suggested putting the fellow in irons for a week.

"That would do no good," said Captain Parkman. "We couldn't keep him in irons throughout the expedition, and his incarceration would only intensify his hate and desire to have revenge when released. Moreover, a punishment extending over several days would have the effect of engendering sympathy among the other sailors, and no one knows what might result from it. The punishment to be effective must be short and quick."

"Captain," suggested Fairfax, "I should think it would be well to reason with the fellow. Appeal to his nobler instincts, show him his suspicions are unfounded and—"

"You don't know him, Fairfax," exclaimed Hardy, the first mate. "The man is a brute. He hasn't one redeeming trait."

It was at length agreed that Boxall should be overpowered, put in irons, and flogged for insubordination and attempts to incite rebellion. The next day was settled upon for the punishment.

It would have been better for all on board had they carried out their intention then and there. Next day was too late, as will be seen.

The Terror overheard every word of the discussion. Concealed behind a pile of rope and tackle, he listened to the verdict pronounced against him, and his breast heaved with the fierce passions of hate and revenge.

"You lubbers," he muttered hoarsely through his clenched teeth. "You'll flog me, will you? We'll see. I'll have revenge on you all or I'll die for it—and that before daylight."

He left his hiding-place stealthily, and not one of the men knew he had been on the deck.

That night was beautifully bright and calm. The firmament, lit up by the pale silver moon, and studded with countless stars, was reflected in all its grandeur in the vast expanse of placid water beneath. It was a glorious night—one that should have dispelled all evil thoughts from man and turned his heart to the Infinite Being who could make a world of such beauty.

At midnight all on board were asleep, except two or three actively engaged in the management of the vessel, the watchman, and one other person.

The last named was Boxall. He had no desire to sleep. His mind was filled with a fiendish plan of revenge. By half past twelve he had made his way unnoticed into the hold, where the fuel and provisions were stored. His movements were stealthy and catlike. Lighting a lantern he set it upon a cask, and, taking, from beneath his coat, a bag, he opened it and drew forth an auger and several other tools. He then tightly fastened the hatch-cover, threw off his coat, and set to work. His horrible purpose it is unnecessary to explain.

About three o'clock the watchman, by the merest accident, noticed there was something wrong with the vessel. One step of investigation led to another, and, at last, he discovered there was nearly a foot and a half of water in the hold. He immediately raised the alarm.

The Captain was quickly on deck. There was the wildest scene of excitement, as the men scrambled up through the hatches, some of them scarcely half-dressed.

The pumps were set working at once, and the sailors labored with zeal; but they could gain no headway. The leakage was so great that the water rose upon them at the rate of eighteen inches to the hour.

Fairfax volunteered with the first mate to go below and search for the hole, but, after an hour's vain groping about in the water, returned and took his place at the pumps. There was no great disorder. The men behaved well, and readily obeyed Captain Parkman's orders. Even Boxall, to the surprise of all, showed a disposition to obey. No one guessed he was doing it to avert suspicion. In his evil heart he was rejoicing, for he was willing to purchase revenge with his own life.

By daylight it had become evident that no efforts could keep the vessel afloat; the hold was nearly half full of water.

"Lower the boats!" shouted Captain Parkman, and the men sprang to execute his order.

Fairfax rushed off to bring his charge. He found him in his state-room, already making preparations to abandon the ship. The old man had put some things in a carpet-bag, and he now asked Fairfax to strap it about his back. The latter was surprised to find him so cool and collected.

"Come Doctor. Hurry up," he cried. "The vessel is sinking!"

"John, I have been thinking over Bessel's parallax of the Star 61 Cygni and—"

Fairfax seized him by the shoulders and hurried him out through the cabin and on to the deck where there was now the wildest scene of confusion and dismay. The men, instead of descending into the boats, were shouting at the top of their voices and cursing in a manner frightful to hear. A deadly fear came upon Fairfax when he learned the cause of the uproar.

The small boats, as well as the Eurydice, had been scuttled!

THE majority of the sailors, realizing that there was nothing to save them from a watery grave, acted like mad beasts. They shouted for the author of the mischief to show himself that they might tear him to pieces, and none was louder in his demands than Boxall. Seeing two or three regard him with suspicion, he pointed at Dr. Parkman and exclaimed:

"There! There he stands!"

Immediately—before Fairfax could guess their intention—two or three sailors sprang forward and, seizing the Doctor, threw him over the rail into the sea.

"Man overboard!" cried Hardy.

The Captain, Maloney and several others, who had been vainly endeavoring to repair one of the boats, hurried forward; but already a dark object had slipped quietly over the vessel's side, and a second splash was heard in the water. It was John Fairfax, ever mindful of his oath. Having sunk and again risen to the surface, he swam round and round, waiting for the Doctor to reappear. At last a head came above the water. He grasped it, and swam away from the vessel toward a spar, which had been thrown overboard. This he reached, and clung to with his half-drowned charge in his arms.

Boxall, with a murderous look in his face, picked up a sledge- hammer and raised it above his head, with the deliberate intention of hurling it at the men in the water. But the missile never left his hands. A shot from Captain Parkman's pistol was heard, and the next moment Boxall lay on the deck.

Overboard now went planks, doors, casks, and everything that could be of help to keep them afloat.

Smithers and two or three others had been engaged in constructing a small raft out of some planks and spars, and this was also thrown overboard.

"Overboard all for your lives!" shouted Captain Parkman. "The vessel is sinking!"

There was one wild cry, followed by a noise of splashing, and, a second later, the vessel careened over on its side, displaying in its bottom two large holes which the miscreant, Boxall, had bored. Then there was a death-like silence, succeeded by a gurgling, bubbling noise resembling a groan, and the Eurydice sank, drawing down with it all that were unfortunate enough to be within the influence of its suction.

Fairfax was not among these. Anticipating the danger, he had swum with his charge as far away from the vessel as he could.

He now looked around and saw the water strewn with planks, casks, and a few persons madly struggling for life. Seeing one object larger than the rest, he swam toward it, drawing the inanimate Doctor after him. He reached it, and, after much difficulty, pulled himself and his friend on to it. It proved to be the raft which Smithers and the others had so hastily put together. It was about sixteen feet long, and ten or twelve feet in width. Just as he was turning to see what help he could render the others, he noticed a hand clinging to the farther end of the raft. He crawled forward over the Doctor's body, reached out his arms, and helped on hoard the stalwart but half-drowned Maloney, whose first word, scarcely audible, was one of gratitude.

At this moment a cry was heard, and, turning, Fairfax beheld, about forty feet away, the ponderous Butt Hewgill, lying like a log in the water. As was afterwards learned, Butt had never sunk after the first immersion consequent upon his fall. He had refrained from making an effort, and on that account, and, perhaps, because he was so large, had floated like a cork. Fairfax plunged into the water, swam toward him, and seized him by the collar. Just as he was about to return with the lad in tow, a large object came to the surface between him and the raft. It did not need a second glance to tell him it was the inhuman Boxall.

The latter had not been touched by the bullet discharged from Captain Parkman's pistol; he had cunningly dropped, when the shot was fired, to give the impression he was killed. He had leaped into the water just before the vessel sank.

For a moment Fairfax thought he saw, in the Terror's wild eyes, an expression that meant he would prevent his regaining the raft if he could. Whether or not he guessed rightly is hard to say; certainly Boxall was too exhausted to carry out such a purpose. Throwing up his arms, and uttering a cry, he was just about to sink, when Fairfax, reaching out to a plank near him, gave it a shove and sent it within his reach. Boxall clutched it wildly, and, with renewed hope, struggled to get his chest on to it.

Maloney had by this time recovered sufficiently to rise to his feet and unfasten a piece of rope attached to the raft. With very good aim he threw an end of the rope so that Fairfax, who had meantime come closer, was able to catch it and place it between his teeth.

Still holding Butt by the hair, our hero was pulled by Maloney toward the raft As he was passing the plank to which Boxall clung, he reached out and grasped it with his left hand, in this way saving the life of the man who had been willing to die to gratify his passion of revenge.

Had it not been for his well-known laziness, Butt's conduct would have been regarded by his companions as a bit of unexampled stoicism. He did not move a muscle to save himself. Even when lifted on to the raft, he lay as passive as a log, as if he were no more than a disinterested spectator of the scene.

After Fairfax had got aboard, Boxall was hauled on with the greatest difficulty. He was not senseless, but, either from baffled rage or exhaustion, he lay quiet and suffered himself to be rolled to the center of the raft so that it might not capsize.

Though Fairfax and Maloney scanned the water on all sides, they could see no other human being. The brave Captain Parkman, with his officers and the rest of the crew, had perished.

It was a sad sight, that beautiful morning, to see, on the shining surface of the ocean, but a few bits of wreckage, where, a short time before, had sailed a gallant ship freighted with human souls.

Wonderful and incomprehensible are the ways of the Omnipotent, who, in His Infinite Wisdom, saw fit to place, among the rescued, the very man that had caused such wanton destruction! Boxall gazed on the ruin he had wrought, and not even a sigh of regret escaped him. If there was a legible expression on his wicked countenance, it was one of dissatisfaction at the incompleteness of his revenge.

Of the five human beings on the raft only two were able or willing, to put forth an effort for safety.

"Boxall," cried Maloney, eyeing him with a comic expression of disdain, "can't you give us a hand to gather thim casks an' boxes, an' tie a few more planks to the raft?"

No response came from the surly Boxall; only a look full of hate.

"Och! you lazy vagabon', you'd rather dhrown than work. I believe in my heart it was you scuttled the ship."

"Shish!" whispered Fairfax, seeing Maloney's honest Irish temper rising. "Let's have peace. Our safety depends upon united action."

"H'm! United action! With three of them prosthrate," grunted the disgusted Maloney. "Get up Goliath," he added, giving Butt a shove with his foot. "Get up you lazy bundle of averdepoise an' don't be a dead weight on us."

But Butt was not to be moved to action any more than the sullen Boxall, or the helpless Doctor, who had revived, and was now crying like a child over the loss of his brother, the warm- hearted Captain.

Fairfax and Maloney secured as many of the boxes and casks as they could, and considerably enlarged and strengthened the raft by the addition of several planks. They found in the water quite a large piece of canvas, which, having become inflated, like Butt's capacious trousers, had not sunk.

With this, a couple of planks, and some nails, secured by tearing up one of the boxes, they managed to fix up a very good sail; and, the wind rising shortly afterwards, they were soon borne some distance from the scene of the wreck.

All that day they drifted along with the ever increasing wind, and, as night approached, there came up signs of a storm. Dark clouds gathered in the sky, and the wind grew so strong that the raft, unshapely as it was, seemed fairly to fly along.

Fairfax and Maloney were brave men, but their hearts sank within them when they saw the sea becoming so agitated that, at times, they were raised ten feet high on a wave and then plunged to a depth as low.

DARKNESS came on and added to the terrors of the ship-wrecked sufferers. The storm increased in violence. The thunder rolled, and the lightning flashed so vividly and so frequently that it seemed as if they were surrounded by a phosphorescent sea. The boxes and casks, upon which they had relied for food and drink, were swept away. The sail was torn off, and drew with it the planks to which it was attached. The raft itself threatened every moment to go to pieces, under the beating of the angry, merciless waves which tossed it about like a cork. It seemed a miracle that it held together.

Its terrified and half drowned occupants clung to it with the tenacity of despair, three of them lying crosswise and holding on to the outside planks with the hope of keeping it together till the storm should subside. Butt and the Doctor did nothing but cling to Fairfax, and whine with fear. Their moans, for they were terribly sick, were pitiable to bear. The Doctor, from sheer misery, tried, several times, to throw himself into the sea, and would have succeeded but for the watchfulness of Fairfax, who did not once forget his sworn duty.

Fairfax and Maloney displayed the courage of heroes. Heedless of their own sufferings, they did all they could to inspire their companions with hope, though they had very little themselves. Assailed by hunger, thirst, and sea-sickness, they maintained their dreadful struggle against the force of the elements, knowing that, if they should succeed in living till daylight, there would still be little chance of rescue. They were alone in a great ocean, without food, and beyond the reach of succor.

By midnight the tempest had considerably abated, though the sea was still running high. The clouds, that, like a funeral pall, had obscured the sky, began gradually to roll away, and the moon, peeping fitfully through the rifts, lighted up the turbulent ocean in all its terrible grandeur and desolation. At no time during the night were the sufferers so impressed with the horror and loneliness of their situation.

"Boys," said Maloney when, about two o'clock the wind suddenly fell, "keep up your courage. We don't know what's comin' next."

"Perhaps you could tell us," growled Boxall.

"O then you're the miserable, hateful Turk," answered Maloney. "You're enough to give one sore eyes. I'd rather walk with a Hottentot through the Sahara Desert than ride with you in a gold chariot."

"I want something to eat," groaned Butt.

"Be patient," whispered Fairfax.

"'Pon me word Goliath you're the most wonderful piece of anatomy I ever saw,"—Maloney had a habit of giving nicknames—"I believe in my heart whin you're dyin' you'll be callin' for your meals. What are you sayin', Doctor? Keep still Boxall, you mumblin' haythen, an' let th' ould gentleman articulate."

"I think it is all over," said the Doctor faintly.

"D'ye mane the storm?"

"No—our existence."

"That's a consolin' piece of information. When did you arrive at that discovery?"

"We can't do without food. I'm starving."

"See here," returned Maloney, "for the last twenty-four hours I've kept two biscuits in my pocket waitin' for just such an extremity."

"Give us them! Give us them!" cried Boxall, Butt, and the Doctor together.

Maloney and Fairfax divided the two biscuits among their three starving companions, but took no bite themselves.

At last morn broke, fair and beautiful, and lo! there was land in sight away to the west. Fairfax could not suppress a cry of delight when he saw the dark ridge with a light hazy mist suspended over it. His transports exceeded those of Columbus when he first descried San Salvador. In a moment Mike was awake and his shouts of joy aroused the others.

"O glory be to the saints this day! There's blessed terra firma that I never expected to put a foot on again!"

Butt rubbed his sleepy eyes and gazed like one out of his mind, while the poor old Doctor shed tears of gratitude and joy.

"Be the livin' Cadi," cried the jubilant Maloney, "I don't care whether it's Bengal or Iceland. I'll run any man a foot-race when we land. I never expected to have the use of my mud-hooks again."

"Easy, Mike," said Fairfax. "We have to land first."

"Aisy is it? There's nothing to hindher us now. Sure I could throw a cow by its tail that little distance."

"It's a good six miles," returned Fairfax, "and if I don't mistake we're receding from the land. There seems to be a current or swell keeping us back."

"Then let us try," burst out poor Butt, his melancholy visage lengthening with the prospect of drifting seaward.

"Yes, yes. Try, try," pleaded the Doctor in accents that smote Jack's heart with pity.

Fairfax liked the old man who, in spite of his cranky ways, had a kind heart and showed much fondness for his protector.

"We'll do our best, Doctor," he said. "Keep up your courage and with God's help you'll be saved."

He looked around to find something with which they might propel the raft, but there was not even a piece of one of the boxes left.

"We're at the mercy of the waves," whined Butt.

"Keep still, you omadhaun," grunted Maloney. "Haven't we been at their mercy all night?"