RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

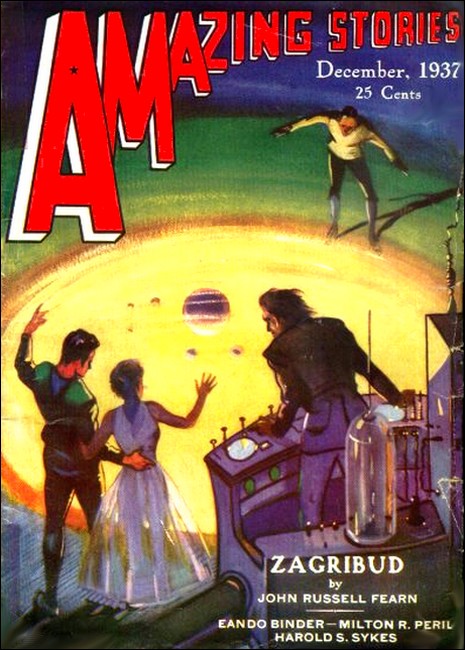

Amazing Stories, December 1937, with "The Radium Doom"

Like Milton R. Peril's earlier novel The Lost City, this story about a Martian invasion of Earth reads like the work of an author who learned English as a second language, acquiring a large vocabulary without really understanding usage. The style is often puerile and bombastic, and the narrative is replete with redundant hyperbole, malapropisms and unintentional catachreses.

Here are a few examples:

"... in the throes of a mental dream..."

"... On some faces were consternation and befogginess."

"... his statements seemed stretched and his words appeared dilated."

"The brow-beating, strength-sapping Gobi sought to manifest itself..."

"... messages that raged with beseechings for haste."

The last sentence of the blurb preceding the story in Amazing Stories reads: "The only reason why we do not praise this story, is that it will be found to take admirable care of itself." Perhaps this is a tongue-in-cheek hint of the editor's real feelings about the quality of this work. Let the reader decide!

The present digital edition of The Radium Doom has been included in this library solely for its curiosity value as an example of the "alien invasion" sub-genre of science fiction..

—Roy Glashan, 7 January 2021

In this story, the east and the west meet and the atmosphere of the cosmos is what fills the tale. The only reason why we do not praise this story, is that it will be found to take admirable care of itself.

DR. SHEFFIELD relaxed in his upholstered chair, his eyes falling on the blaze which illuminated the snug book-lined library, from its haven in the fireplace. The crackling flames were a myriad of colors. They played noiselessly with the stillness of the lore-stocked room, chasing each other along the carpeted floor, creating elongated flashes which seemed to speak to each other in understandable fashion. The middle-aged scientist watched fascinatedly the bluish taper of fire rise and fall amidst a curling consuming clutch of red; fire always centered his thoughts, made him think more lucidly.

Now he stared into the conflagration and gave himself over to the thing which occupied the foremost of his thoughts—had occupied it for many a long and tedious day.

He had thought that the presence and value of the bas-relief which he had unearthed in the Gobi desert had been unknown to the general world outside the realm of science, but Anderson had just called him and told him that things were just about going to break for them. The different archaeologists, with whom he had been in consultation since the uncovering of the gold bas-relief, had all promised silence concerning the existence of it; though they had so far been unable to tear from its grasp its meaning, they all realized that it contained something vitally important. The little they had been able to understand stood out prominently and direly. Always that elusive substance which would explain the whole thing clearly evaded their active and brilliant minds.

To begin with, the gold carving was old. That much they could easily see and feel without being misled. The characters presented thereon were of an ancient touch. It all manifested an ancient civilization—but though the world of science knew that the yellow men had been civilized far back, ages ago, long before the white men had been imbued with the expansion of their minds, this bas-relief contained something which did not coordinate with the unearthed civilization of that folk. It was contrary to the general run of findings of that long-ago educated people.

That was what Doctor Sheffield and his associates had gathered after many long and interesting studies of that gold relic. Doctor Sheffield had spared no time or money to strike the deciphering key to this readily recognized thing of tremendous importance, but each effort had met with a negative result, like the others. To a man like Sheffield, with the indefatigable energy he possessed, especially when something taunted him and refused to bow to his sharp and tirelessly boring mind, this snag of a thing aroused him to the fullest extent.

The fire crackled on. He broke the magic spell that held his eyes glued to that picture of living colors and turned to the small table at his right elbow, a table laden down with books, scripts and small fossils. Reaching down to the bottom drawer, he unlocked it and drew out something wrapped in swabs of cotton. Gently, he disentangled the gold bas-relief from its bed and placed it tenderly upon his lap, in the flare of the fire in front of him.

The precious article must have weighed about four pounds; and though it was valuable as a mineral it wasn't that element which made it stand out so startlingly. Rising from the base of it were about three-score finely carved characters, which at first glance looked like old Chinese prints. It was a beautiful piece of workmanship, so exquisitely designed that it caught the eye and held it; near the edges strung a fine lace of woven gold, spun from the very heart of that rectangular substance of art; it seemed as if he could feel with a gentle finger the delicate living links mesh along his skin.

HIS eyes rested upon the enigma which had enfolded him for so long, and though his alert glance bristled under a bank of outcropping brows, bristled because in his lap lay an unanswerable problem, he fondled it with care, and his scientific heart absorbed it with admiration. It was an object of profound art and to him, even though a blank puzzle, art and beauty went foremost into the inner recesses of his appreciative mind.

There were three orderly rows of characters, each a supreme effort. Around each raised letter was faintly etched a small design of two spacial bodies in their respective orbits, presumably two planets revolving about a center object, the sun.

Doctor Sheffield gazed long and studiously at the thin lines. It was these etchings which had made the entire working out of the bas-relief an impossibility. He could decipher with difficulty the few characters on the end, but when he attempted to put two letters together to form some cohesive meaning he could get nothing. The etchings before and after each letter destroyed every method to bring about a unity of thought. If he could but stumble upon the true essence they intended to depict, then he might figure out something to it all. But upon an ancient carving a picture of two planets revolving was beyond him. He, nor any other scientist who had seen it from time to time, could find any key or formula which would explain this.

With careful fingers he returned the bas-relief to its swab of cotton and locked it in the drawer. His large shoulders shrugged as he set himself back in the chair and dropped his gaze once again onto the brilliant glare in the fire-place.

What did Anderson mean when he said that some outside person knew of this thing? That this same person held some answer to it all? He had seen to it that few people not within the pale of science were aware of its existence.

He heard a step behind him and turned to find his man-servant ushering in a young man. His face lit up.

"I'm glad you are here, John."

The assistant professor smiled broadly. "I'm glad I am, too, Doctor. Have some good news for you!"

The older man was upright in his chair now, his eyes lighted with interest.

"So I understand. Sit down and tell me about it."

John Anderson took the seat proffered him by his superior, extending his feet toward the fire and drawing out his pipe.

"You will have a visitor here shortly," he declared between puffs. "I'm not going to tell you anything other than it was a Chinaman who called me up about an hour ago and got me to arrange for this meeting. Somehow, Doctor, I experienced a strange feeling on hearing his voice over the phone." He shook his head. "Almost as if he held the solution to it all!"

The older man rose from his chair, the light of the grate being reflected on his countenance and animating it. His eyes were aglow. He walked slowly about the room, into the shadows and out of them, his powerful shoulders shrugging every now and then.

He stopped suddenly. "Nothing is clear to me, John. There is a mystery here somewhere. The threads are trying to come together with some semblance of explanation but I understand them not. It's been a void from the first moment my eyes fell on it."

He stopped before the fire and gazed down into its depths. For a long moment his eyes stared unseeingly into the heart of it, then a shudder crept over him.

"I must tell you, John, even though you may already feel it, I fear something vitally wrong, so deep-rooted that it rips at my inner self; yet I can't explain it. I am too old and too hardened a scientist to take stock in unexplained feelings, but I am succumbing this time, mostly because everything looms right upon me, I suppose. I can speak to you, John, without being misunderstood. I hope this Chinese person of yours knows something, for I can't let this thing creep through my marrow like this. It is as if something is going to happen."

He let his glance fall on the younger man who was smoking in the chair. Their eyes met; but there was no ridicule or misinterpretation in the atmosphere.

THEY might have wandered into irretrievably profound recesses of thought had not the manservant once more made his presence known. This time Sheffield cast off his cloak of revery with ill-concealed expectation and ordered him to bring the visitor immediately into the room.

There entered into the semi-shadowed library a small but wiry figure with a smooth crop of shining black hair and a pair of piercing eyes. He advanced with a nod to Anderson and Sheffield, introducing himself as Ti Yun. The young Chinaman was seated between his hosts.

Immediately, once the light of the blaze penetrated the shadows and settled upon the physiognomy of the yellow man offsetting his parchment-like skin, the eminent Doctor's eyes crept to the deep ever-moving orbs of the man before him and he felt that his assistant had depicted some true picture of him. Staring out at him from under those scant brows were sage eyes attempting to pierce his mind, trying to extract from him something, something....

So he felt, and it was with another shudder—one of those which were becoming quite constant with him now—that he snapped the feeling of the unknown from him and addressed him.

"Ti Yun, you have aroused our curiosities. Let us be frank. What do you know about this bas-relief, this puzzling thing?"

The small man's eyes flashed, portraying every vestige of a living entity, but his pallid yellowish skin remained inanimate. Truly, thought the men watching him, if ever there was a soulful, conscious, absorbing essence which seemed to speak for itself, it was that pair of eyes.

The Chinaman laughed noiselessly. "I shall be frank, thanks to you. There will be no gain by being deceptive here. I know that you have the bas-relief in your possession. I know also, though you have not the least idea of this, that it holds the fate of the world in its very center. The flesh of the earth is reaching the point of dissolution; it will be the greatest catastrophe that ever befell it. I am not here to demand that ancient relic which you have. I am here to join every mind in one cause for what shall come. You, Doctor Sheffield, are a noted man of learning and thought. Pray that you shall be given strength and courage, to know what to do in this emergency!"

The tension that hung over the room was heavy. The scientist watched the commanding vision of the Chinaman before him, and though his statements seemed stretched and his words appeared dilated, the Doctor did not for a moment doubt his assertions. It was odd. Everything was descending upon him with too sudden a force to be ignored, scorned or disbelieved.

"Ti Yun," spoke Sheffield gravely, "understand that I and Professor Anderson are eager to hear everything you have to say. Please do not fear that we may ridicule you. We are ready to stand at your side and assist you. Your honesty seems real and not on the surface, if I am a judge of character."

Ti Yun relaxed in the chair. "Ah, gentlemen, that is what I have been wanting to hear. I couldn't bear to come to you before this, for fear I would be misconstrued and hooted out of here. I am glad that I have your confidence. It will make things easier, easier for all of us."

Sheffield said, "Our confidence comes from the fact that the bas-relief has been an insurmountable thing in our lives, and the possibility that some one may work out the true meaning from it are not to be set aside."

THE fire flickered and sputtered as a log was slowly being consumed, but nobody paid any attention to it. Two scientists' eyes were upon one thing now, the face of the Chinaman, Ti Yun.

"Gentlemen," the yellow man started, "I don't want to see that bas-relief yet. Not until I have finished with what I am going to tell you. Then it can be brought out and we can have the answer to it all.

"You can readily see that I have forced my way to you through some ulterior motive. It is not a selfish one, that I can tell you, for it concerns not me alone but every living intelligent thing on this earth. You, Doctor, and you, Professor, cannot begin to realize the dreadfulness that lies over our heads at the present moment. I shake myself time and again hoping against hope that I have been in the throes of a mental dream, but I know otherwise. I shall not hold you in suspense.

"I am a Chinaman. I was born in Mongolia, in a valley that is in the center of the great Gobi desert, which lies like a clutching threatening reptile, within the reach of the scattered yellow man ready to consume you once you enter its domain. Four unscalable walls stand around that valley like a quartet of rows of silent sentinels guarding those within its folds from the ravages and fierceness of those whirling eddying sandstorms, from the wide waterless wastes. Few people know of that valley, gentlemen; yet it is so fertile that we grow everything necessary for the personal consumption of the dwellers there, and the green pastures on which tread and browse our animals cannot be conceived of being but a bare distance from a stark aridity. Myself, I do not know where the water comes from. Many times I have attempted to discover the source of the trickling waters which course into our valley from the crevices of the vast walls, but to no avail.

"Once in a while our people gather together a small expedition and wander forth from their haven unto the distant lands and cities of other yellow men. It was during one of these journeys that they lost the gold bas-relief which your expedition found near the spot where the skull of the Peking Man was uncovered by the Roy Chapman Andrews expedition in December, 1929, the oldest skull of man ever found, reputed to be almost one million years of age. Let me tell you, incidentally, that it was the skull of one of our race.

"However, we searched the ground around there for years in the hope of finding that bas-relief. Our expedition had no right in taking that precious thing with it, for the possibility of it being lost was always apparent. We hoped to find it before it became too late for it to be of any use. We were always dreading that it might be forever sealed in the bosom of the desert by the settling blanket of ever-present sand. If that were the case, we would have to warn the world of the impending calamity and let them find out for themselves, later, that we spoke the truth without evidence. We would not admit to ourselves that we were no more to see that bas-relief, upon which rested the security of the world.

"And so months ago a yellow man told me something of your expedition in Mongolia, Of course I had known of your being there, but what he told me quickened my pulse. It seems that one afternoon just before you were ceasing your work there, you, Doctor Sheffield, wandered among a small scattering of petrified stumps with this man at your heels and pounced upon something which lay under a small obstruction. He saw your eyes distend, as though you had found the richest pearl in all the world and wanted to conceal it, even from yourself. After that day, this fellow told me, you seldom came out of your tent, only to give commands to your subordinates who were doing the routine work preparatory to closing down the camp and starting for home. Once, he said, when he was passing your tent the wind swirled past and blew the flap open at the entrance. Inside, he saw you and Professor Anderson bending over a square thing that gleamed dully in the light. Your puzzled faces were so intent upon it, that you didn't notice nim.

"When I heard that, I knew that it was the bas-relief you had before you, which had evaded the searching eyes of my people for so long. Even the ground upon which your camp had been pitched had been dug up many times. Nothing ever could stop us. So upon this discovery I hastened immediately to this country. I had been educated here, knew it well. My eminent father had prepared for the deciphering of the bas-relief when it would be found and the dissemination of the danger to the world by the education of me here in several languages. That is why I am so proficient in your tongue and mannerisms.

"From the first I loved this country, its physical freedom and the opportunities for self-expression. I couldn't get enough study during my stay here. I wanted to saturate my mind with everything, my soul with every desire.

"But I was called home, needed. Gentlemen, when I came home everything was explained to me for the first time.

"My family had been rulers of that tribe of yellow men for countless centuries. That I knew. I was the only son, the direct heir. But I learned many things that, once I had begun to digest them, made my mind whirl in confusion, then in abject terror!"

TI YUN continued: "I'll tell you the story as my father told it to me. Thousands of years ago, long before man had begun to utilize his mind for a purpose other than self-sustenance, when the wide landscape of Asia was a fertile place and populated with the animals and mammals of which you now so diligently seek the bones and deposit them under the roofs of your museums and houses of learning, that valley was an uninhabited place. There was no yellow man. In fact, no yellow man existed upon this earth.

"The yellow man was never a native of this earth! He is an immigrant! Don't look so incredulous! I am going to prove my statement in time. You ask how could he be an immigrant and still not come from this earth? Where could he have come from?

"Gentlemen, the yellow man is fundamentally built like the rest of the humans who dwell upon this mother earth, but he never came from this world. His original home is on our sister planet, Mars. That is where he comes from!

"Please do not doubt me. I told you at first that my words would seem highly distorted once you heard them. I even shelter the germ of dismay within me. But then, as I said before, I know conclusively the truth—that the yellow man, that my own ancestors, once roamed the land of that pin-point which sets so far away in the heavens but which is, as you will soon hear, so near—alarmingly near.

"The yellow man was not the highest developed form of mind on Mars; in fact, he was no more developed to that higher form which I shall explain to you, than the mind of a lower beast is to that of ours to-day.

"Countless ages ago, as our scientists now understand somewhat, the planet of Mars underwent a cataclysmic transition in its water supply. According to my father, its natural liquid resources became almost a nonentity, only a small portion of it being preserved at the poles, and it was, after a frantic and almost superhuman attempt, directed into the large canals over the entire land, which had been hastily built for the benefit of the inhabitants.

"But the supply was insufficient. The type of body that lived on and controlled the planet dwelled in water as well as on land. That body was in the form of an elongated eel, the average length being about eight to ten feet, and it was supported in the air by a score of thin but very wiry elastic legs which moved with rapid precision when it walked on the ground, and which folded up at the sides of its slimy body when it entered the water. These flying, walking, swimming eels were the highest type of civilization on Mars, higher then in mind than any form now present on this earth. Think of that and you will begin to dread the rest. For if they were so supreme in mind then, we cannot begin to comprehend their abilities now. It would be imaginative beyond words, even thoughts.

"Also, there dwelled at that time on Mars in conjunction with this super-minded eel, a race of people, the forebears of the present yellow men. At first, they were merely another form of life there, simple in mind, and following their own tendencies and inclinations, never interfered with in any way by that super race of eel-men. Their trails crossed daily without the slightest discomfort to either.

"But when that drastic drain on the water supply was felt by both races and they watched the inevitable change of their precious liquid into thin vapor, the eel-men were the first to spring into action. With a natural leaning to preservation, the yellow men joined in and in time were hard at work building up those canals which are evident over the face of the planet to-day. But by joining with these eel-men and manifesting their extraordinary laboring powers they spelled their doom. The creatures naturally assumed an authoritative state over them and began to exploit their possibilities. They worked them to death, sitting aside and preserving their spineless bodies.

"But the time came when the eel-men could not get enough liquid for their personal consumption and wallowing, and their scientists started in to discover some new means to replenish it. They looked with greedy eyes toward the earth and saw the eventual haven where they could settle down to a permanent, comfortable life. They constructed a gravitational ship that was to take them to this earth. It was a simple matter for their developed minds to overcome the problem of interplanetary travel.

"The principle of their travel, however, depended mainly upon the existence on this earth of some super-radioactive substance, which would act as rudder and controlling power for their ship once they got into this atmosphere. That power, which they had in abundance on their own planet, they finally discovered with instruments. It lay in enough of a concentrated quantity on one spot upon this globe; thus they were assured of a safe landing.

"But just before they embarked on their exploring journey, one of their scientists made the discovery that halted them temporarily. It was the finding that will be the eventual ruin and disintegration of the human race. It was the discovery that the yellow men possessed something which was of more value to them than any other liquid that they had ever come in contact with. It was the blood of the yellow men, the warm life-fluid that coursed through their veins!

"It would have been better had that sudden orgy of blood-sucking begun and ended right there, with the complete annihilation of the human race. Had the appetites of the terrible creatures been accorded full sway over their senses of mind and had they destroyed the human race once and for all time, it would have been a blessing to those now living, for the race would have been wiped off the slate long ago. But that didn't happen. The higher minds of the eel-men ordered a stop to the destruction of all their supply of blood to be taken from the yellows.

"This delayed their trip to the earth for a while. The yellow men were rounded up and put into barred and protected quarters to breed. And each eel-man was allowed only so many yellow men per Martian year for his own personal consumption, in pro rata with the supply.

"According to my father, the bodies of the yellow men were useless to them after they had been used for the life-fluid. They were reduced to fertilizer and spread over the fields.

"Imagine—I read the horror even now upon your faces—what a period my ancestors were going through. They may have been greatly inferior to that highly civilized mind of the eel-man but they harbored feelings and sensations that were human, which you and I readily understand, but which those godless beings never dreamed of. To be used on the table of a beast, for its personal and physical enjoyment, was a terrifying and heart-rending thing. But they could do nothing about it."

"THE Martian eel-men finally came to the period when they alighted on this earth. They landed in the valley in Mongolia, where I was born, and which, as I have explained, is the only spot where they could have landed, because it is immensely rich in radium, a radioactive mineral. They dropped their ships perfectly.

"It was the age when massive mammals and other gigantic land creatures roamed about, and the Martians explored the earth from end to end and gloried in its richness. They were able to preserve their puny bodies from the vast destructive animals that existed by their simple use of mental telepathy which had such a marked effect on these creatures. Every animal turned meekly aside once it came into contact with that unseen power. For the first time, the yellow men knew what a power lay in those slimy heads, for strangely enough that telepathic urge had never been effective on them.

"They slithered over the ground and glided in the water with safety. The space-machine had not been utilized in exploring the earth; it had been useless because it hadn't ample projectiveness and controlling power from a concentrated body of mineral. They could come down, rise, move along only so far as the mineral body existed, but once near the outlying reaches of the radium their speed diminished and they finally had to stop for lack of control and returned.

"The result of that trip to the earth was that the eel-men constructed many more ships for the purpose of bringing their entire supply of yellow men to the earth. But something again delayed their task.

"The eel-men who had made the journey to the earth suddenly became the victims of a body-racking disease which they couldn't cure. It paralyzed their entire bodies in the end, leaving but an active mind in a useless hulk. They realized then that the earth contained some sort of natural foe for them, a microbe, and they stopped to consider the best means of combatting it.

"They labored hard trying to discover what germ it was but nothing they did brought relief. Finally, the super-minds of the eel-men decided upon the migration of the yellow men in order that they might breed in numbers and become useful to them after they had solved the problem of the paralyzing infection. Strangely enough, the yellow men had not been affected by any destroying germ such as had harmed the invaders. So more eel-men sacrificed themselves to the earth's germ, in order that they might place upon their planet load upon load of the yellow men.

"And thus it was that, on the last load, they left that bas-relief. On it was carved the different times when they would descend again, when Mars would be in proximity to the earth, and for many, many years they did come on those dates recorded, but they never stopped longer than to take back a large supply of their delectable humanity. Suddenly they stopped coming for a reason I don't know. When, after a long period of dates on the bas-relief had passed by and they showed up no more, a deep breath of prayer was offered up, and they soon became a memory only, to the minds of the existing generations, though in our hearts there was etched indelibly an unknown fear.

"Gentlemen! the day is near when that fear will flame anew! Those dreadful depictions which linger deep, deep in the recesses of the brain lobes, those fantastic thoughts which are in-explainable shall soon crash into plain view. A hideous sword of Damocles lies over all of us!

"The bas-relief was kept always under lock and key. The house of Yun trusted nobody with its terrible secret. My ancestors long before had etched in the beautiful characters of their written language the meaning of that gold relic left them by the eel-men. It was done so that the successive generations might interpret for themselves the positions of the different solar bodies. It is probably this which makes it indecipherable to you; you can't understand its significance. But there is a key-note upon that bas-relief that can be explained only by one of the house of Yun. We know, however, that the inhabitants of Mars must descend only on the time of greatest proximity of their globe with ours. It creates a greater potency for their ships. But the question is, when will they come? That I can tell only by looking at that gold slab.

"So you ask how do I know that they will come? I shall tell you. One night years ago, when I was but a small child, I remember my father running into his study in an extremely disturbed state. At that time I didn't comprehend the full importance of it, when he said to himself, 'They have come! They have come!' He took me by the arm and led me to his observatory window. There, in the heavens, a black, gigantic, egg-shaped body floated. He watched it with popping eyes, I with a curiously innocent gaze. For some reason it didn't stop here, but disappeared. I recall vividly my parent throwing himself upon his face and becoming hysterical with an outburst of prayer. I had never seen him like this; only the stern haughty ruler he had been.

"He sent me to school in America. When I became mature he told me of his intentions. The time was very near, he explained, when the people of the earth were to mass themselves against a foe who would undoubtedly conquer them. The eel-men would take what they wanted, he declared solemnly. We would never be able to combat such a superior intelligence. It was written in the books.

"He showed me the transcriptions of his forefathers, how they had written of the terrible consequence of being a man. They were all of the belief that the future of the human was destined to be a sacrifice upon the altar of a super-being. My eminent father's intention was for me to disseminate the knowledge to the world. He sent me in search for that bas-relief, which had been lost long before, for on it was the date of doom! Then came that lucky find of yours!

"My father bade me go immediately to you. I came with a trembling heart lest my mission be ridiculed in its fantasy, lest it would be heralded as a far-fetched tale, but you have accorded me genuine attention and I am content. As God has made us, I have spoken the truth! That is all."

THE head scientist lay back in his chair, his hands folded on his breast, and stared at the yellow countenance of Ti Yun. The room had long since become cold, the fire being in the hearth a mess of charred embers. Professor Anderson sat silent, speechless.

The Chinaman looked into the faces before him. "May I see the gold bas-relief?"

Doctor Sheffield stirred into action. He leaned down and unlocked the drawer of the table at his elbow, and drew forth from it the swabbed, precious article.

Ti Yun's fingers reached eagerly for it. His eyes studied the old wording and, as though he had suddenly become aged on the instant, his head dropped on his chest.

He said, "You know what it says here?"

They shook their heads.

Ti Yun continued, "Several proximities have occurred since that space ship was here last. But this bas-relief has not any of those dates upon it. The next proximity written thereon is—three months from now!"

The statement galvanized them into action. Sheffield sprang from his chair and extended his hand for the bas-relief. "Explain it to me," he demanded.

With both scientists about him, Ti Yun interpreted the meaning of the inscription on the relic and with shaking fingers he pointed out the spot where the two planets would swerve near each other. Both watched him with absorbed, lined faces.

"Why did you wait this long?" the doctor cried. His face betook a hard look. "Never mind," he snapped. "It's no use grieving over that now. We must make this known immediately, get the heads together and fight it! It is our only salvation!"

Anderson observed his superior striding the floor like a madman, but knew all the while, however, that a turmoil of mental effort was going to be beneficial. He knew that Sheffield had believed that tale as he himself had believed it; felt, too, that there was no essence of untruth whatsoever in the statements of Ti Yun. In the sea of their orthodox scientific minds, ordinarily, there would have been no surface for that fantastic tale to have anchored to as barnacles do to wood under water, but something had rung true and clear here, so genuine that their hearts were being beset by a fear never known to them.

Sheffield snapped on the lights which lit the room. Gone were the shadows which had accentuated the starkness of the tale, dissolved were the eerie depictions which had played over the dark walls. He took from a rack a large volume, opened it, and studied it intently.

After a moment, "You are right, Ti Yun," he said hollowly. "But a bare three months remain, until Mars comes within 33,000,000 miles of us. Three months for us to do what must be done!" He dropped the book and leaned heavily on the table with one hand, the other stroking his cheek feebly. "Heavens! We must do something! Humanity must survive those ghastly creatures!"

PROFESSOR ANDERSON got out of his chair, his fine athletic form becoming taut. "Doctor," he said slowly, "we must not keep this solely in our hands. We must call in the greatest minds of the world to aid in attacking this evil. We must all be one now, white, yellow and black. Nations and people must melt into one solidified unit for safety!"

The Chinaman caressed the gold bas-relief gently, the thing which his many ancestors before him had held in their hands, and exclaimed, "The world may not accept the story and the truth. I am afraid we will be censured as sensation-seeking persons."

"You may be right," Sheffield asserted. "But they must be told. We cannot withhold anything, even though we may be subjected to the utmost ridicule. My standing, however, in the world of science will not be ignored. I shall bring over to my way of thinking the higher heads. They will see what peril lies over us. There is no time to be lost. We must start immediately."

And so it was done—the alarming of the entire world. Newspapers carried the stories of Ti Yun and the stern command of Sheffield, that it was the greatest catastrophe that could befall the earth, and within twenty-four hours the whole civilized world was staring at their possible eradication.

The reaction was peculiar and somewhat running with the grain of human nature. It was partly the way the famous scientist had stated. The every-day mass read and wondered, a momentary fear possessing them; then they paused to burst out into the expression that a good yarn was being put over on them. They read the narrative of Ti Yun as they would consume mystery tales—avidly, and presently uninterestedly.

But to the scientific world it was a different thing. They demanded an ample and decisive proof from the famed and honored Sheffield, evidence of this fantastic presumption, and they received it. Sheffield presented it to them with the bas-relief and the salient features that went with it.

Even with science on the platform of belief, however, the masses would not acquiesce to the fact that they were going to be used as food for a pack of eels, which were supposed to derive from Mars, and which would possess more mind than the worldly human. It was too grotesque a tale to be taken without a grain of salt, and it was pooh-poohed. Governments continued their oiled paths, paying little or no attention to it. They were not interested in petty troubles. There was a people to be governed, money to be earned. And as the nations thought and did, so followed their many subjects and citizens. Science could evolve its own fanciful stories and seek out its own remedies.

It was a hard struggle from the beginning, the scientists noticed in alarm. They couldn't blame the people for their unbelief, it was true, for it was beyond the credibility of the ordinary run of intellects.

The keen minds, however, got together for the purpose of laying out a suitable defense and thus the days went by. Arguments were given pro and con without any end being attained.

AND then one day, several weeks later, the earth awoke to its first startling realization. Just as before they had scoffed, so now they became imbued with frantic terror.

In simultaneous reports from Shanghai and Tokio came the announcement that some mysterious death was taking the lives of hundreds of people. In the market square of Tokio alone countless bodies had been piling up one after another from unseen causes. But what terrified the people was that, though every one of those bodies had shriveled up, not one drop of blood was left in the veins! Shanghai had the same story to tell, only in more magnifying numbers. People were falling in screaming agony, and what was left of them presented the same lack of the warm fluid that sustains life!

People were now clamoring for anything to offset that thing which was assailing them. In Chicago, where the scientists were convened, they flailed them for immediate action. Where before these men of learning had been handicapped by the indifference of their fellow-men they were now hounded for instant relief.

Day and night they remained awake discussing violently the possible means of doing something. And day after day the wires grew hot with the revelation that Asia was becoming mowed down, and from an unknown cause.

Then, to the horror of everyone, San Francisco crashed one afternoon into the news with ghastly reports, followed by other cities on the coast. It was spreading into Europe, too.

The world rose up. Thousands had literally died from nothing. It was a profound puzzle. Surely it couldn't have been an unknown germ descending suddenly upon an unwary populace. A body was hurried with utmost haste to the assemblage in Chicago and examined. It proved devoid entirely of blood, but what brought everybody to their feet was the fact that the body had been punctured over the heart, two red holes being evident. And when word came in from the other centers that the other corpses had the same gashes over their hearts, then things began to happen.

From the valley in Mongolia came the wire from Xu Yun, the ruler of that isolated group, that a dozen or more ships had landed and many eel-men had scrambled out and vanished right under their very eyes. Ti Yun read the telegram to the scientists and the worn and tiring men simply tore their hair. They couldn't fight unseen foes!

While the mob below howled and screamed, Doctor Sheffield rose to his feet and spoke to the scientists.

"It has come! The Martian creatures have been with us now, creating havoc, and all in an invisible state. We have before us an example of the magnitude of their resources. They have shown what they are capable of.

"We are at a terrific disadvantage. Without knowing where our opponent is, we cannot defend ourselves. Our position is bad. And furthermore, Mars is not in its nearest position to the earth. They have come before the scheduled time. I can't understand that."

Ti Yun rose to his feet. "It is written that they generally come in advance only to leave quickly. Probably it is so that they can size up the situation here."

It was an important disclosure, unverified as it was, and it precipitated them all into a madly eager attempt to strike a solution to bring safety. Voices cracked under the strain of tensity. Hours ground away despairingly and wearily. Ti Yun had to tell his story again and again, while the rest tried to force from it some method of saving themselves. He was hoarse when at midnight his eyes suddenly dilated and he let out a screech of delight. It roused every one in the chamber and they gaped at him.

"Gentlemen," he bubbled almost incoherent with joy, "I have it! The key to everything! We shall be able to fight this enemy to a finish, to save mankind!"

OPEN-MOUTHEDLY they listened as Ti Yun went on: "I am surprised that we have not thought of it before. It is going to be the most gigantic task but now it is our only way out. Remember when I told you that the eel-men could come to the earth only through the medium of that body of radium which engulfs the valley? There is our solution. Without that radioactive mineral massed there to propel their ships, they cannot land on this earth!"

On some faces were consternation and befogginess at this; on others perplexity. Sheffield asked, getting some faint idea, "You mean that we should take the mineral from there?"

The Chinaman nodded. "Yes! That is our only hope. We should have thought of that in the first place and would have had ample time to have removed it. We must dig down those mighty walls that hem in the valley and distribute the earth all over the world. By doing that we shall be safe!"

A Frenchman interrupted, "What good will it do us? They are here now. Even if we take away the metal there remain upon the earth these invisible eel-men. We are doomed."

"I think not," returned Ti Yun. "This trip of the Martians is yet prior, two months in advance. The exodus from Mars will not begin in volume until that time, I think. For that length of time we shall be safe in so far as having to deal with thousands of the eel-men. These who are here usually go back and report on the condition of everything on our earth. If they follow out their past course, they will soon leave. But we must begin now to assemble every man available on the Gobi and break down those walls. We must!"

They would have pinned their hopes on anything plausible and this made the heart beat quicker. They immediately decided on that action. Instantly every government spun into movement and ships were commandeered to take the millions of eager men thenceward, for the purpose of tearing down those immense walls, behind which was deposited such vast stores of radium.

Ti Yun's father was placed in charge of the work. He had communicated to his son, the day before, that the Martian ships had left, but not before thousands more of men, women and children had succumbed. The fact that they had been forerunners was now a tremendous relief to all; it made everybody pitch in with abandon.

The world gave its everything. From all over Europe started a trek toward China of the millions of men who couldn't secure passages on some of the usual means of travel. They wanted to be there, to assist in anything. Factories worked day and night, supplying an almost impossible amount of shovels and picks and the like for the use of the men.

Obstacles meant nothing to them. The brow-beating, strength-sapping Gobi sought to manifest itself, but millions of men were not to be denied. Lines of rails were laid on the seething desert, clear to the valley hemmed in by the great natural walls. It took almost no time, so fast did the railway unfold itself. And immediately the slow disintegration began.

EXAMINATION revealed that the radium content in the rock was of so great a quantity that it would never again be the rare mineral it was. No effort was made, however, to isolate it from the rock and earth; there was no time for that now. Work! Faster and faster! Steadily were the shifts of men removing the key which would spell their downfall if left in its present position. As fast as the men removed the rock it was transferred to large cars which were endlessly moving back and forth on the rails. The rock was dumped on ocean liners, ships of every conceivable description, and the distribution of it over the different lands of the earth was in charge of a corps of men. To no place was given an amount large enough to produce an inlet for those Martian ships.

Sheffield and Anderson labored tirelessly, caring not so long as their eyes watched their efforts slowly but surely wearing down the resistance of the mighty walls. One wall was gone in ten days, another was slowly crumbling up. According to estimates, it would take less than five weeks for everything to be finished. And then the earth would be free!

The executive council believed in arraying the territory as if in preparation for an attack. They did not dare take any chances and get caught napping. Big guns were set ready to be focused on any given point at the word. The district for miles stretching around was one of seething humanity, ever-moving, ever-working. There was not the slightest pause. Even the scientific body had changed its residence and had moved its abode to the scene of action, establishing the laboratories at hand; they were in the thick of devising some devitalizing, counteracting influence which would block the bombardments of the plentiful radium emanation, but to no avail. At first had been suggested a thick coating of lead over the hills, but that had been deemed inadvisable owing to the length of time which it would necessitate.

Sheffield and Anderson had been accorded the honor by Xu Yun of staying in the age-old abode of the royal family, there in the fertile valley which was now shedding its outward cloak and beginning to look at the threatening desert for the first time.

It was here that the famous scientist viewed the massive room wherein were stored the scripts which had survived thousands of years. The walls were stacked with bound books of all sizes, reaching up to the ceiling—an invaluable lore-covered interior.

Doctor Sheffield removed a volume from the rack and tenderly examined it. His breath almost ceased. Staring up at him were pictures the like of which he had never seen before, and characters which seemed similar to the ancient Chinese on the bas-relief. At some other time the discovery of the ancient manuscripts would have been a great finding, but now only a temporary outburst issued from his lips. There were things of primary importance on his mind. Rut he couldn't help but delve into the mustiness of the aged papyrus with its wonderfully preserved markings. From book to book he moved with a wonder and scientific joy in his eyes; here lay volumes beyond value; the fact that they could have existed through millenniums was astounding. It is known that papyrus is of astonishing durability, not perishable in a few years like common paper.

There was no reading these at a few sittings, or even in years, and he paused after going through several.

"Xu Yun," he inquired, "which is the most valuable here?"

The Chinese ruler smiled. "I doubt whether you will understand it, it is so old. Even I comprehend it not to the fullest. But there are drawings—"

From a locked drawer he withdrew a wrapped article. Unwinding it, a cord-tied mass of paper-like material was evident.

Sheffield gazed at the strange tint which was woven into the glazed fibre of the paper and as his fingers felt it, he could almost discern an invisible strength beneath them. The oddish, green lines which crept through every sheet, were like living threads keeping alive an inanimate object.

"How could these drawings be so life-like, so beautiful?" he marveled to himself. Then suddenly he awoke with a start. An elongated creature, its body reposing in the air upon many stilt-like legs glared loathsomely at him. Its head crept out of its slimy body, like a grotesque feature coming out of a cave-like formation.

"An eel-man," rasped Anderson.

"Exactly," confirmed Xu Yun. "The picture is perfect." He pointed to the long tentacles that reached down from the lower jowls to flop against the ground. "These are the suckers which pierce the body and extract the blood!"

They stared long at the picture of the creature. In their minds roamed the thoughts of such a blood-curdling animal being a superior mind and wandering over the face of the earth overriding the puny attempts of the earth dweller in his effort to remain alive. The calm and gentle peace of the earth came to them, the beautiful evenings which permeated the joyful heart, the loves for the brother flesh—all the finer and aesthetic states of existence gone to a destructive waste. Cities which had spread with the countless generations of inhabitants crumbling into a dust that would resound only to the patter of scaly, filthy paws. Desiccation!

"Good Heavens!" was all they could muster into expression.

The newspapers of the world published that terrifying picture. It was enough to speak for itself, and it did, hideously! Those suckers almost leaped at them from the paper and sank their cold, clammy tenacity into their yielding skin!

FROM all parts of the world sped messages that raged with beseechings for haste. The workers in Mongolia were exhorted to strive to their capacity, and the continuous stream of incoming men grew in volume until every foot of ground was packed. It taxed the ingenuity of the directors to feed that mass, but the world took from its own table so that those working might not want. Their only fear was that the work might be in vain, in spite of the announcement that it would not take more than five weeks to clear the land of those towering cliffs.

Mars was almost at its nearest approach to the earth. The eel-men, had they desired, could have come at any time now, in any number. But just as Ti Yun had spoken, they held their reins, yet. And so the days went by and the terrestrials held their breaths and subdued those terrifying thoughts which lay within.

The desert was no more; it was a human melting pot redundant with humanity. Not one pause for silence. Every load that was carted away meant less strength for those Martians. Every bit of earth that was dug loose meant that much increased closeness to freedom.

Then came the day when the wires heralded the disastrous fact that a space flier had landed. It had happened in the middle of the night and was witnessed by thousands of men, who immediately set up a tremendous uproar.

The Martian ship came to earth in the middle of the valley. Sheffield and Anderson had at that moment been in the sky-room of their host, Xu Yun, and had been one of the first to sight it. With terrified eyes they watched it come hurtling through the heavens as if it were some astral body afire.

"They're here." Shrieks rose from everywhere, when it crashed into the valley with a resounding noise.

Instantly Xu Yun's face burst into a straw-grasping look. "See!" he cried. "They can't control their ship! They have not enough radium power from the surface!"

And it appeared as though this statement might be the truth. Something had been the matter with the landing of the Martian vehicle! It had not come down in ordinary fashion, but had been propelled like some drunken meteoric body, which caught itself just in time, and had broken its fall at the last moment. And that glistening light had been the metal of the ship on fire!

THEY were affixed, as were the other millions who were now staring at it. The ship rested in a half-imbedded hollow which it had scooped up in its mad dive. It had no apparent opening through which anyone might issue forth. For quite a while they watched it lethargically, but it remained motionless and silent, as if life had perished within it on the perilous journey through the earth's unyielding atmosphere. During that time no man went near it. Perhaps it was because they were so terrified that their presence of mind was all gone. They simply stared and gawked.

Sheffield and Anderson were almost convinced that enough radium had been transported from the vicinity. The suspense was broken by an Englishman who came bursting in. He was one of the directors of the entire work.

"What'll we do?" he asked quickly in a strained voice.

Sheffield raised his hand. "Don't do a thing until I give the word. Train several guns on it but don't fire until I signal. I want to see what will happen with that ship. Perhaps those Martian creatures have perished in their swift descent."

They watched it for longer moments. "Let's go over and look at it," proffered Professor Anderson. "We might be able to study it."

They strode over to the ship, while around them countless faces were staring at them and at that weapon of destruction. Even in the night these men looked frightened and pale.

A searchlight suddenly broke through and fell on it outlining it in every detail. It was about twenty feet in width and thrice as high. Tapping the outside hulk, they could feel no hollow sounds; it seemed as if it were some object composed entirely of solid metal.

Anderson turned to the Chinaman at his side.

"Xu Yun," he asked, "perhaps you know how this thing is entered?"

"According to a script," the ruler nodded, "these open from the top, a narrow strip unfolding down the middle, which is a ladder."

They examined it more closely. This time there were quite a number of men around them, who were interested in the findings of the scientists. All were silent, patiently waiting.

"I wonder how many Martians can get in this," one scientist ventured. "About a score of eel-men," replied Xu Yun. "This one of their small ones. They have massive ones for the transport of hundreds."

"Bring the men with the torches," ordered Sheffield. "Everybody stand back!"

The electric arc torches were brought forth and applied. Try as they did, however, they could not dent the metal at all. It remained immune. A ladder was hauled up and placed against the side. The scientist ascended it slowly, carefully.

Every eye watched him scale it anxiously. Nobody dared to wonder at the outcome; they only stared.

JUST when Doctor Sheffield had reached the top, a matter of about fifty feet or more from the ground, a sudden rumbling became apparent from within and immediately everyone stiffened. Sheffield paused, his fingers entwined around the rung of the immense ladder, and before him he saw the top slowly revolve as if on an axis, and then move away from the center as though it were an opening.

Like a plummet, he dropped to the bars below him and was soon on the ground below. With a silent signal to disperse, he ran for the house, Anderson and the Yuns behind him. Men scattered in all directions. The English director sped past him.

"Fire, once the men are free of that ship," the scientist commanded. "Don't wait. Get rid of it immediately!"

Everybody disappeared as though by magic. Sheffield and Anderson were once more in the sky-room with the Yuns, staring at yonder ship of doom.

The top slowly turned again and again, like a top spinning in slow motion, and then a long strip of metal unfurled from the very peak of it to the bottom, and everything became quiet once again. The searchlight was still focused upon it, and it was plainly to be seen. A row of steps crept the entire length of it, but no life was visible yet.

"Why," stormed the Doctor, "don't they fire?"

Their nerves were worn to a frazzle waiting for the shell to come whizzing over their heads to strike that ship. No more did they want to study it and its contents; freedom from its frightful meaning was what was craved.

A movement was seen on the steps. Into view came a descending creature about ten feet in length with limp, impeding tentacles that seemed to get in its way, as it labored for breath. It writhed as though in pain. The glaring white light of the beam made monstrous a savage head swaying from side to side.

"An eel-man!" whispered Ti Yun shiveringly. And as he spoke there came down the steps four more of the creatures.

The men were frantic. "Where are those confounded men at the guns? Why don't they fire?" But still no gun shattered the stillness of the night. Everything was silent. The painful, struggling movement of the eel-men was noiseless.

"The earth's pull is too heavy for their Martian bodies," Xu Yun pointed out. "They're moving around so that they can get used to it."

And it was so. They slithered along the ground on their many feet, their bodies falling on their bellies time and again in an effort to remain upright. A marked improvement appeared, however, after about ten minutes. They were able to walk on the ground and not struggle. During that time a half-dozen more of the creatures had emerged.

One, who seemed in better shape than any of the rest, gazed around the land with large bulbous eyes, blinking in the merciless luminosity of the searchlight. His eyes fell on the one wall of the mountain which remained and he snapped his head surprisedly at the excavated sides. He whirled on the others of his tribe and something went between them. To those who watched in the dark it looked as though he were informing them of the reason for the strange action of their interplanetary ship. Once one of them broke into a throaty, raucous voice. Sheffield ran his hand through his hair with a wild look. Where was that shell?

Eleven of the eel-men were now picking their ways over the green sod of the valley, gradually moving away from their ship.

AT that moment came the long-awaited crash of the distant gun and the whine of the shell as it split the air overhead. The explosion was tremendous, being so near the men, not ten feet away from the space-ship. It tore a large hole in the side of the Martian means of travel. Sheffield couldn't help but wonder at that time why the electric arc hadn't been able to dent the metal and yet the shell tore it apart. Perhaps, he thought, it was because there had been an opening which had permitted the outer blow to crash inward without resistance.

Another and another shot fell, and after the earth-trembling noise and dust had subsided there was indescribable wreckage all around. Of the eel-men all sight was lost.

The gun was silenced and the men went forth to explore the debris. An exhaustive survey revealed torn and twisted parts of the eerie and inhuman creatures, but nothing was left of the ship that would aid their work by the examining of it. It seemed very strange that the eel-men had all been blown to smithereens; they had been some distance from the ship which had received the brunt of the exploding shells.

The directors convened immediately and were unanimous in the view that the remaining hill must be downed, even if men had to swarm over it like flies and stand on each other's head to get at that earth with its ore.

Doctor Sheffield stated, "What we saw to-night, if magnified by hundreds of such machines, will mean quick finish for all of us. Our single consolation lies in the fact that the power of the radium is almost nil. We can remove that hill in a week. But that will be too late. It must be gotten rid of in two days or less. The Martians will begin now to come in vast numbers. Every load taken away from here means that their ships will act as meteors without control. Let that be our incentive. This predatory enemy of mankind must perish!"

The muscle-racking efforts were redoubled. Every man, his arms and mind already failing under the strain, was instilled with a new strength: Fear. Yet infused in them was the spirit of victory, for had they not seen with their own eyes that they had taken the toll of Martian property and life?

Twelve hours elapsed from the time of the Martian demise. The hill was disappearing from view as though vast teeth were biting off chunks of it. Then came the terrible announcement to the world that almost a thousand workers on the remaining natural tower had suddenly succumbed in fearful agony, and that all of their blood had been drained from their veins!

IT was very obvious now! The I shells had not destroyed all of those creatures! They had become invisible and had escaped danger to themselves so that they could coordinate their bodies with the greater gravity of the earth, and then they attacked the laborers on the last hill, so that there might yet remain enough strength for the direction of their fellow creatures' ships.

Once again the outlook of the world was dark, a gaping hole where their hearts had been. All their hopes, suffering and undertakings were to be in vain, then? Why should they go through all this miserable discomfort to themselves if it would only be futile and they were to die ignominiously on the altar of a brutal, fiendish blood-sucker from another world? Should they really even attempt succor for themselves, when it was being tossed in their faces that nothing could save their skins? Why persist in fighting against the inevitable? The invisible?

No one amongst the workers knew whose turn would be next to feed his life blood to the Martians. Yet, insanely frantic, they gave not one step but kept their blood-shot eyes on the incessantly descending picks and shovels. For several hours after the massacre they kept steadily ahead, laboring against time. During that time no one was touched.

This was very strange to all. "If those eel-men want to exterminate all of us to save the radioactive power, they would not have stopped so suddenly," reasoned Sheffield.

"You forget," advised Xu Yun, "that they absorb the blood in their own bodies. They are so greedy that they would not think of extracting it from a man and squirting it away. And they can hold only so much."

This statement was evidenced several hours later when an immense swollen thing on crawling legs was sighted struggling away over the desert beyond the farthest outpost.

The scientists were immediately transported there. Crowds of men followed. It must have been an abnormal being, for though ten or twelve feet in length, it was fully fifteen feet high, far higher than any of those that had come out of the Martian ship.

Ti Yun exclaimed, "He's full of blood! Swollen!"

They hastened nearer. The eel-man had long since become aware of them but it seemed to do nothing to defend itself. It just moved along stupefiedly.

The two long suckers which were dangling from around its neck were distended and raw, as it could be seen. The Martian made a movement—the tentacles flew out with a snap—and men fell back in legions. But the creature simply turned and stared listlessly at the scurrying men. This gesture halted the fleeing workers, and they pondered its apparent harmlessness, then returned slowly.

"It won't harm us to get near him and study him," spoke up Anderson. "Must be numb, that fellow!"

ONCE more they crowded around the sluggish tracks of the Martian. One crazed man pulled a gun and levelled it at the thing. Sheffield roared not to shoot, even as some one tore the weapon from him.

This time the eel-man was angered, and it whirled and swung its suckers. It caught the nearest man in the stomach and sent him flying straight into those behind him. Again there was a rush for the background.

"Let us get in front of him," suggested Sheffield. "We might be able to see what happens from that angle better."

The two scientists and several co-followers made their way around the creature. Several men raised their rifles ready to fire at the least provocation toward Sheffield and Anderson.

The Martian stopped its dull floundering at the sight of them and glared malevolently at the men. Sheffield and Anderson felt a slight shock suffusing their bodies as the large globules of eyes focused on them, but nothing harmed them. Sheffield stuck out his hand and made slowly toward the beast.

Instantly the creature halted, dropping its body to the ground and waved its head with its slobbering jaws from side to side. From its rear it slowly started to disappear, become invisible. The blankness moved toward its head, but right in the middle of its swelled slimy body it stopped. Lying on its belly was half a Martian! The transparency went no farther, even though the eel-man waved its head angrily from side to side—and then its entire body flashed again into view once more. Viciously it spat, then the suckers flailed the ground balefully. Again it attempted to become wholly transparent, but only the rear half succeeded.

"The instant the creature becomes invisible, shoot!" ordered Sheffield.

SOMETHING was the matter with this Martian, they saw. It couldn't muster to its command that essence of invisibility. It raised of a sudden its inflated awesome body and lashed out spasmodically with its tentacles and fastened them upon two men standing nearby.

Instantly the guns roared. The thing dropped, and the bloated body started to slowly disgorge its accumulation of blood, which poured out in a putrefying horrible mess. The stench grew so unbearable that it was all Sheffield and Anderson could do to hack those vicious suckers from the victims and drag them out of the range of the fumes without being overcome themselves.

The injured men were taken away to be treated, and Sheffield offered up the explanation:

"There is the reason those creatures couldn't become invisible and continue with their destruction. They have attacked in few numbers but consumed so much blood that it has made them sluggish. It is apparent that the human blood's composition will not become coherent with invisibility like the rest of their bodies. And transparency is their chief weapon against us."

This one encounter brought joyous tears to the face of the anxious world, for it proved that satiation of the earth-man's blood would be their own undoing. Men, women and children shrieked with delight.

Orders were given to anyone seeing any visible Martian to shoot to kill instantly. Man could expect them to be revealed now owing to their tremendous store of blood which dilated their bodies so grotesquely. And within several hours several more of the lethargic creatures had been killed, as they were struggling with their loads of blood over terra firma. The news of it caused the workers to scream with joviality and serenity for the first time in many weeks, even as they put forth their last ounce of energy to remove the remaining rock and earth.

And then another one of the spaceships landed. The men gazed at it transfixedly as they saw it come shooting down into the valley and force a pit in the ground half as big as itself, but their fears left almost as quickly when the dust had settled. Its metallic hulk was a glistening red and it had been beyond control. They swarmed about it but drew back suddenly in alarm.

The top was revolving with manifest speed, as though those inside were crazed with the desire of being out of its burning interior! The strip which concealed the steps was unfolding with rapidity. Men scattered like rodents, and the cry went up, "Fire! Fire!"

Ti Yun was the last one to leave the vicinity of the ship, but just as he departed an eel-man came tumbling down and caught him around the neck with one of his undulating suckers, jabbing the other meanwhile into his heart. A few had witnessed this and turned to come back to his assistance and rescue.

But a shell interrupted their efforts at that moment and fell upon the scene amid a terrific disruption, and a confused spray of debris fell among them. Another shell fell nearby, completely demolishing the home of the Yuns.

Xu Yun, watching, raised his yellow scrimpy arms to the heavens above and clenched them. His face was contorted into an unimaginable ache, then metamorphosed into a resignedness.

Twenty-four hours later the last load of earth had been removed from the vicinity, and the world of living men breathed a genuine prayer of thanks. Within a few hours scores of meteor-like conflagrations were visible in the heavens above and all knew that they were the ships of the Martians, terraqueous eel-men disintegrating into uncontrollable cinders and ashes. All through the hours those below watched the brilliant spectacle of fireworks aloft. One, a massive thing hundreds of feet long, came as far as the ground, describing a gigantic parabola as it weaved crazily through the earth's atmosphere and crashed, a flaming mass which fell into a crowd of men, killing many of them.

Within a few hours scores of meteor-like conflagrations

were visible in the heavens above and all knew that they

were the ships of the Martians, terraqueous eel-men

disintegrating into uncontrollable cinders and ashes.

Each hour with its record of streaming meteors was written in the newspapers, and each word seemed almost to jump from its bed of print, in gratitude that the human race had won its greatest battle, that an unearthly creature had been repelled.

But everything was not yet over. There were those monsters which were still upon the earth, still getting over their huge consumption of blood. They were a problem to deal with. Everybody turned out into the desert and hills armed with guns of all shapes and makes, weapons of every sort. Five were found trying to hide themselves and were disposed of immediately, their deflating bodies creating an odor that drove all away. But the good work had been finished. The world was safe.

THE Mongolian country around that valley, amid the unsurpassed rejoicing of all peoples, was transformed as a final gesture into a beautiful land, commemorating the many who had perished so that their fellow-men might be saved from the ravages of a Martian monstrosity.

One evening, in the newly constructed abode which Xu Yun called his home, the two scientists, Sheffield and Anderson, sat at a table, with the bas-relief of gold lying before them. The Chinese ruler reposed on a chair and gazed at the relic reminiscently.

"This, gentlemen," he uttered softly, "has saved humanity for posterity. Without this bas-relief there would have been a void on this planet now. Instead of love and peace going hand in hand upon the face of this globe, there would be only a hell in which would gloat a slimy creature. Many souls have gone from here to pave a smooth path for generations to be born unfettered. Mine among others!" His head dropped.

Doctor Sheffield lay back and his thoughts went back to the day when he had found the gold thing. All of the ensuing, unbelievable things which had happened since then! Through it all stood foremost the face and form of the young Chinaman who had been born a son of a ruling house of people who had been civilized long before the white man; Ti Yun, the man whose parent sat now at his side, but whose ancestors had once roamed the lands of the planet, Mars; Ti Yun, whose greatest desire and purpose was to see the earth saved from a ghastly fate, and who had given his life and blood to that end.... Ti Yun....

The world went back gradually to its routine, of course, but it was impossible for it to forget in any degree what it had just gone through. Perhaps in the years to come those new generations would read of it and marvel, but it was for the present to carry in their hearts always those emotions which had once spoken so dreadfully.

The name of Ti Yun became a household word of reverence. It was one spoken with softness always. And in their yearly pilgrimages to the now-gorgeous gardens of that fertile land in Mongolia, the millions bend down on their knees before the beautiful shrine which rests on the spot where that Martian ship went up in splinters and dust with Ti Yun in the clutch of an eel-man, and the eyes read with abated breath the epitaph:

TI YUN

HE LIVED FOR OTHERS,

AND DIED THAT

OTHERS MIGHT LIVE

And atop the inscription, set neatly in the head of the monument, is the gold bas-relief.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.