RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

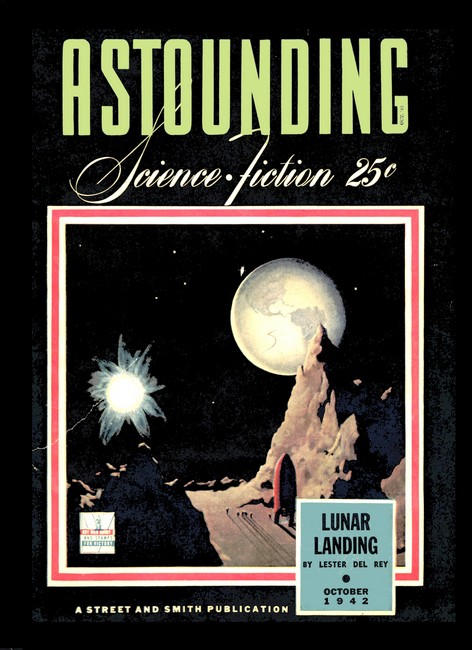

Astounding Science Fiction, October 1942, with Anachron, Inc.

Anachron Inc. were merchants, not missionaries. They were traders whose outposts and trading stations were established across time from Egypt's glory to Modern America. But Barry's station was medieval France, and his goods were umbrellas and—miracles to order!

SIX o'clock came and a squad of Civic Guards came out and started breaking up the line. The local placement bureau was closing for the day. Ted Barry cursed wearily under his breath and turned away. For the last hour he had been anxiously watching the descending sun and counting the men ahead. Fifty-four, fifty-three... forty... thirty... now twenty-eight! That close, and it all had to be done over again. He had been standing there since early dawn hoping against hope that be would get in that day, but it was not to be.

He walked down the street, thankful that be could at least do that—not shuffle along in the dispirited fashion of his mates. For most of the other men seeking occupation were still in uniform as he himself, though his distinctive uniform of a major of Commandos set him a cut above the majority. Not that having been a major was much help—not even a Commando major; ex- majors were a dime a thousand.

He took the nearest cross street that was fairly clear. The labor gangs were just knocking off for the day, and he saw that their job had been well done. The street was lined with gaping ruins, but the rubble in it had all been carted away and the bomb craters neatly leveled off and filled. Beyond he could see a block of buildings that had come through the war unscathed except for the loss of glass and the scarring of the lower walls by fragments. Directly facing them the walls of the elaborate new Museum of Art were rising—one of the many projects of made work instituted by the Commonwealth of America to take up the slack of unemployment. It was that that he hoped to be assigned to, yet he wondered bitterly what was the good of it all. What would they fill it with when it was done? For there was no more art. The savage Kultur raids of the mid-forties, unleashed by the frantic successors of the suicide madman Hitler, had seen to that.

Their systematic devastation of culture centers—and also the equally savage reprisal raids of the United Nations—had left the world without an art gallery, a museum, a college or school, church or palace. The incidental destruction of most private homes had taken care of the pitiful little household collections of pictures and books. Virtually nothing remained.

Again Ted Barry cursed, but it was a thing that had to be accepted. He made his way into the public chow hall and grabbed a tray and the necessary utensils. Then he made his way along the electric tables, picking out what he wanted to eat. Thank God, at least food was plentiful. Too plentiful. The unfillable maw of war had forced an unprecedented overproduction—to sweeten the oceans with sunken sugar cargoes, to furnish fuel for the flaming warehouses smitten from the sky, as well as to feed the hungry billions who fought, or tended the war production machines.

As he munched his food be thought gloomily over his life and the hard luck that was his in being born at the particular time he was. Born on the eve of what was then fatuously regarded as the greatest depression of all time, he had emerged from it only to be snatched into the vortex of the horrible War of Survival. And now, in the evil year 1956, he had been mustered out—two years late, for, except for the final mopping up by the Commandos, the Axis had been crushed several years before—only to find himself in a depression that might better be described as a bottomless pit. Literally thousands of square miles of useless war plants existed, tooled for planes, tanks, ships and guns; aluminum, now made by a cheap process from common clay, was a drug on the market at ten dollars a ton. Except for certain selected industries, such as textiles, staple foods, petroleum and the like, equally swollen, every other kind of plant had long since been converted to war uses or else fed into the insatiable steel furnaces as scrap. Not many had been rehabilitated. Coupled with the imbalance of production was the existence of hordes of demobilized soldiery and discharged workers. The outlook was gloomy, despite the vigorous efforts of the various commonwealths of the Federated States of the World.

Barry rose, reached into his pocket for the penny that was the nominal price of the meal—a face-saving device that kept it from being a handout—and started for the cashier's desk. He noticed a man standing by the wall who seemed to be studying the eaters; he was a well-dressed man in civilian clothes, and had a sleek, smug look about him that was slightly irritating to Barry.

As Barry brushed by the man on his way out, the fellow handed him a folded piece of paper. "This ought to interest you, buddy," said he. "I think you're just the type. Save it, it's valuable."

Barry's impulse was to shove the hand aside and pass on; it probably was one of the many come-on gags worked on the innocent veterans. But the man was in his way, and now there was an earnestness in his expression that might mean something. So, to avoid a scene, Barry mumbled something and pocketed the paper without looking at it. Then he deposited his penny at the desk and made for the door. A receptacle for trash was near it, and his eye caught sight of a complete newspaper tossed in on top the other rubbish. Its title was not alluring—The Weekly Financial Digest—but at least it was reading matter, and anything to read in the dreary little cave he lived in was an item to be prized.

He turned east in the gathering gloom and followed the littered street across town to the burrow he had made for himself in the ruins of a gutted building. It was not palatial, but better than many foxholes he had known, and in it he was king. He had a small reserve store of eatables, but above all he had independence and privacy. It was a dark hole, but that did not matter. His service "juicer," or super-battery, no bigger than a half-pint flask, still contained thousands of amperes, enough light for him for many weeks. He took off his uniform and laid it neatly away. Then he rigged the light for better reading, and settled down for a quiet evening. Idly he glanced at the dodger handed him by the man of the eating place. It proved to be a printed circular, and he wondered that a man of such well-fed appearance should be handing them out. It said,

QUALIFIED MEN WANTED

We can use a limited number of agents for our

"foreign" department, but they must be wiry, active, of unusually

sound constitution, and familiar with the use of all types of

weapons. They MUST be resourceful, of quick decision, tact and of

proven courage, as they may be called upon to work in difficult

and dangerous situations without guidance or supervision.

Previous experience in purchasing or sales work desirable but not

necessary. EX-COMMANDO MEN usually do well with us.

Application should be made at the east door of Anachron

Building, 6 Wall Street. Do not apply unless you have all the

above qualifications.

Well, thought Barry, that's a little better than most. Here

was a firm that actually wanted Commandos! Every other

prospective employer had turned him down. "Sorry," ran the

formula, "but we're afraid of you. You fellows are too damned

independent—too used to being on your own. Our men have to

do what we tell them."

He laid it aside and took up the financial paper. It was dismal reading. He waded through page after page of the wails of frustrated brokers and the gloomy forecasts of economic commentators. Then he turned the page and came upon the feature article of the issue. Among all that crepe and sounding dirges there was at least one hopeful item. Rows of big black type proclaimed:

ANACHRON BOOMING

Orders Mount—Stock Soars—Directors Optimistic

Barry's growing drowsiness was instantly overcome. Why,

it was the man from Anachron who had handed him the circular! He

must find out more about the company, since it appeared now to be

genuine and on the upgrade. He read eagerly that Anachron Common

had jumped that day from eight hundred sixty to two thousand

sixty on the strength of an earlier announcement of a special

cash dividend of forty percent and a stock dividend of one

hundred percent; that the company was rapidly expanding its

"foreign" business and had already taken thirty million bushels

of wheat, sixty million tons of steel and much other surplus

material off the market; that its profits on the sale of these

commodities had been enormous; and that the company was

contemplating vast expansion.

The article went on to say:

The activities of Anachron may be regarded as the most bullish factor in the world today. It is an open secret that since their acquisition of the Gildersleeve patents under special charter from the Federated Government, they have been utilising the Gildersleeve Heavy-duty Time Shuttle for intertemporal commerce. Thus all the wheat, steel, aluminum, textiles and so forth that they export is definitely removed from today's glutted world markets. Not only that, but we are receiving in return increasing quantities of such priceless items as books, old paintings, musical instruments, and many other things we have grown accustomed to doing without.

Uneasiness has been expressed in some quarters lest this traffic with the past ages have serious repercussions in our own, but we are assured by Mr. Otis P. Snoodington, Executive Vice President of Anachron, that the fears are baseless. He states that the most careful control is exercised over the activities of their field men in order that the economic and social life of the older civilisations is not upset unduly. Inventions too advanced for their ready comprehension are strictly withheld. Our readers in the steel industry, remembering some of the amusing orders they have received, will know what we mean.

BARRY folded the paper, closed his eyes and rested for a

moment. His mind was in a state of wild ferment. The amazing

thing he had just read sounded like a piece of wild fantasy; yet

there it was, in an unemotional business paper—a fact,

apparently. Barry was quite prepared for the concept of time

travel—he had been a science-fiction fan in the days before

the war, and had read many yarns playing with the idea, beginning

with the classic one by H. G. Wells and including many of its

successors. The only real surprise he felt was that the fantasy

had at last become cold reality. He liked the idea of

participating in it. He also needed a job.

Barry shot a quick glance at his wrist watch. It was later than he thought—past midnight. He got up and opened his kit and took from it an atomizer. He carefully sprayed his uniform with the dirt-removing substance, and when the liquid had evaporated, taking the grease stains with it, he plugged in his little flatiron and did a neat pressing job. An hour later, shaved, shined, pressed and glittering, and with three rows of medal ribbons spread across his chest, he was on his way through the dark ruins to the canyons of rebuilt Wall Street. However soiled a Commando might be from his task, it was the iron rule that when he appeared in public he must be as if on parade.

It was four when he reached the towering building that housed the head offices of Anachron, Inc., but already there were hundreds huddled before the side entrance where applicants were received. Most were derelicts, old men still hopeful, but there were many youngsters amongst them as well, chiefly from the ranks of the unrated dischargees. Barry could see only four men in the Commando uniform, and they were close to the door.

"Come on up, major," called one. "We rate these bums. You're number five."

He joined them and discovered that one was Billy Maverick who had served with him in the Hokkaido shebang. After that they swapped yarns until night paled to the pearl of dawn and that in turn gave way to full day. During that time nine others of their kind had joined them. Promptly at eight o'clock the doors were opened and they were allowed to go in. Barry glanced up at the company's trade-mark over the portal. It was an overflowing cornucopia about which fluttered a ribbon bearing the legend "Merchants, Not Missionaries." He was to see later that the same emblem appeared over the door of every office of the far-flung system. Before long he was to learn its meaning.

The preliminary interviews did not last long and they were authorized to go ahead for the physical check-up. That was grueling, including severe strength and agility tests. Five of the candidates had to drop out at that point. They had all passed the I.Q. standard, but special aptitude tests took a toll of four more. At length Barry, Maverick and a fellow named Latham were accepted, the other two candidates being deferred for reasons unstated. The three were sent to the office of Director of Personnel where they were told to sign contracts agreeing to "perform such duties as may hereafter be assigned and for such remuneration as the company may deem proper, for the period of at least one lustrum—or longer, at the option of the company—subject to prior dismissal at the discretion of the company."

"Phew!" whistled Latham. "It reads like the Nazi draft of a treaty!" But Barry signed without comment. He had had a taste of what the cold outside was like and how bleak the prospects. Moreover, his imagination had been fired by the reading of the article. Maverick likewise signed, and the vocal member followed suit.

The personnel man grinned. He knew a Commando couldn't be held by a contract if he didn't want to be held; he also knew that no employee had ever wanted to quit. He tossed the papers into a basket and issued three cards.

"Take these down to Basement A and show them to the guard. He'll put you into a bus that will take you to the barracks."

"Then what?"

"You'll be given a room and bed, and get your basic training. We can't send you foreign as dumb as you are now."

"Oh, yeah?" said the incorrigible Latham. "Well, listen, brother, we've had all the basic training there is, plus advanced, plus expert, plus practice. And if there's any place foreign between the poles that we haven't taken apart, I'd like to know what it is."

"Uh-huh," said the personnel man, nonchalantly, "Maybe. But were you ever sent to snare a papa Brontosaurus and a lady Brontosaurus on the hoof? I understand the new zoo has ordered some. And how fast can you load and fire a flintlock? How good are you at mounting and dismounting horses with sixty pounds of plate armor around your carcass? You ain't seen nothing, kid. You may be sent anywhere—and anywhen. After you've been told to sell Prester John ten carloads of apples or else, you'll know what we mean when we say 'foreign'."

"Oh," murmured Latham, meekly, "I hadn't thought of that angle."

They found their bus and were whisked away uptown to the indoctrination center. It was a superbly fitted barracks, the chow was good, but they were disappointed to find themselves in a reception ward in which there were no old-timers except their trainers. Those wouldn't talk. "A step at a time, laddies," was all the grizzled top-kick would say. "If you show you can take it, you'll learn the rest, fast enough. If not, you get the gate with a month's pay for trying."

"How much is that?" Maverick wanted to know. He, alone of all of them, had found surviving relatives on his return.

"Two hundred trade-smackers, base. When you go active the sky's the limit, what with commissions, graft, bonuses and things"

"Did you say graft?" asked Barry, sharply. The word had an ugly sound.

"Skip it," shrugged the top. "Call it side lines, if the word smells better to you. The company doesn't mind, so long as they get theirs and you don't run foul of the Control Board. There's one of you fellows, a Billy Tolton, that has the sweetest little side racket you ever heard of—he's stationed at Rome in Diocletian's time... but say, I'm not supposed to tell you guys these things, you have to find 'em out for yourselves."

Maverick snickered and Barry couldn't repress a smile. They both knew Tolton. He was as square as they make them, but a slick barracks lawyer with it. He was famous for his escapades, but somehow he managed always to be safely just inside the rules. They wondered what he had slipped across the Romans, but the sergeant would say no more, and there was nothing left but to turn in. Barry went to sleep in a little glow of triumph. He was off the streets and out of the endless queues of the unemployed. Shortly he would be traveling throughout the past, not sightseeing or adventuring, but engaged in legitimate business.

THE drudgery of the next three months came as a rude shock,

but the day came when Barry and Maverick were called up and

graduated ahead of the remainder of the class. The Foreign

Department was shorthanded and rushing men into the field the

moment they were qualified. Barry was still a little dubious as

to his qualifications, for so many questions still remained

unanswered. The fatal paradox of time commerce troubled him

unduly, though his instructors evaded his questions as not being

in their province. He could not see why tinkering with the past

would not have terrific consequences in the future that was to be

founded on it, which in turn meant this present.

They packed their bags and left the school without regrets. The course had been half lectures, and half martial and marine exercises. In the mornings they listened to talks on the commerce of the past peoples, from far Cathay to the cliff dwellers of the Southwest. Otherwise they became familiar with antique arms and modes of transportation. All were good rough-and-tumble fighters, but they added the crossbow and the blunderbuss to their repertory of arms, not to mention the catapult, Greek fire, and the handling of scythed chariots. Two days a week they spent at the ship basin where they were told about carracks, galleys, junks, cogs, praus, galleons and triremes. They served carronades and the heavier muzzle loaders of later days. From quarterstaves they graduated to broadsword play.

"What gets me," remarked Maverick, as they climbed into the taxi that was to take them back to the head office, "is why they give us all this military stuff when they say it's against the rules to do any fighting except in self-defense."

"Dunno," said Barry, "unless it's to help us take care of ourselves on the road. There were plenty of corsairs and highwaymen in the old days."

They got a thrill on arriving at the downtown building. This time they went in through the great main portal, already thronged with businessmen coming for their share of Anachron's bounteous orders. The two fresh-hatched apprentice traders did not know the curious specifications that accompanied many of the contracts, but they had an inkling from snatches of conversation overheard in the elevator. "I hear Western Spring Steel got the order for fifty thousand Mark III all-metal bows. I'm trying to snag off part of that duraluminum arrow allotment.... Oh, sure, our Toledo factory is working nights on palanquins and sedan chairs.... I hear wallpaper is going good all over the Renaissance."

The Outside Sales, Purchasing and Contract departments were all on the first twenty floors, above which only certified company employees could go. By the time Barry and Maverick reached the thirtieth floor, they were alone except for the guide who accompanied them. They started down a long corridor marked "Foreign Trade," noticing with interest that each of the many sub-offices was marked with its specialty, such as "Scandinavia: Vikings to Gustavus Adolphus." "Old American, Mayan, Aztec, Inca, Et Cetera."

The guide halted them and called attention to an alcove that was guarded by a swinging chain. A sign said, "Keep Clear, Landing for Trader Shuttles." A red light was blinking and a small gong tapped out an additional warning.

"Some fellow must be in a jam and is coming in to see the boss," said the guide, indicating that they might pause and see the time shuttle land.

In a couple of seconds it did, though it was more a matter of materialization than a landing. The alcove seemed to fill with shadowy outlines, then suddenly a solid platform appeared. The operator of the shuttle stood in a little pulpit at one end, operating its controls. A single passenger slumped morosely in the center of the vehicle, leaning on a gleaming two-handed sword that had a heavily bejeweled hilt. He was dressed in flowing garments which Barry's unpracticed eye could not positively identify, but which he took to be those of a medieval Spanish merchant. The trader was of dark complexion, with a heavy beaked nose, though it was hard to say just what he did look like, for he was wearing in addition a watery black eye, a badly cut nether lip and many minor contusions. His robes were torn and bespattered with mud and overripe eggs. Altogether he seemed to be quite unhappy.

He glared at them briefly, then without a word ducked under the chain and limped off down the hall, carrying his gigantic sword with him. The shuttle faded from sight, and the trio continued their trip on down the corridor. The bedraggled figure before them turned into an office marked "Western Europe—Medieval."

"He's one of your gang," remarked the guide. "That is where you are going."

By the time they reached the office, the trader from the shuttle had laid the sword across the assistant sales manager's desk, and was talking rapidly and agitatedly with many furious gestures.

"But, damn it all, Mr. Kilmer," he wailed, "I did tell 'em! I sent a sword—King Richard's own personal snickersnee. I sent sketches; I sent along the exact specifications. I told 'em why. What more could a man do?"

"Keep your shirt on, Jakie," sighed Mr. Kilmer, a thin, harried- looking man with a perpetual furrow between his brows. "If anyone up here slipped, you're in the clear—"

"Me in the clear!" screamed Jakie. "Of course I'm in the clear. But does saying so write off those ten thousand swords and the beating up I got? Lissen! This guy Richard says the swords are no good—not fit for knights. So he won't pay, and he won't give 'em back. He issued 'em to his men-at-arms. What's more, he had me whipped around Westminster at the tail of a cart and then stuck me in the pillory where those mugs rocked me all day. Look, I lost four teeth, see? And that ain't half of it. The hangman grabs my notebooks, order books and all my kit material and burns them in the square. A years work shot, and am I sore!"

Mr. Kilmer glanced up sadly at Barry and Maverick who were standing silently in the background, waiting to present themselves. But he said nothing for a long time, and then he addressed himself to the outraged Jakie.

"Right or wrong, this tears it," said the morose Kilmer, dragging the heavy sword to him and standing it point down beside his chair while he fiddled with a crystalline knob at the end of its hilt. "Your pal Richard the Lion Heart is just one more pain in the neck to me. Credit put in a bad report and insists on cutting the rest of the order down and demanding half cash for what we do deliver. It seems that they sent their own men to check up on your report and they came back and said that Richard was already hocked up to his eyes. What's more, Prophecy says that even with the better equipment you're trying to get him, the Third Crusade is likely to be a flop. All it accomplished along our own time line was the taking of Acre and Cyprus, and he had to split the take four ways at that. Then he got captured on the way home and his ransom broke the kingdom. I'm afraid, Jakie, that you'd better forget Richard First of England and bunt up a better prospect. And don't be so damn gullible next time."

Jakie uttered wild and sizzling words for a good five minutes, beating his breast and tearing his hair, but all he got further from the boss was the mild order to go down to the gym and get out of his make-up and have the doctors rub liniment on him. Jakie limped out of the office still smoldering. After which Mr. Kilmer turned his mournful mien on his newest traders. Both stepped forward, and he sighed heavily as he regarded them.

"New, eh?" he said, with a notable absence of enthusiasm. Barry waited. "Maybe what you just overheard was as good a start- off as any—gives you an idea why we're all graying grouches up here at home office. Stick around and I'll tell you what it's all about."

For a few minutes he was busy dialing interoffice numbers—Design, Specifications and Contracts, finally the Chief of Inspectors. Presently a messenger appeared with a roll of blueprints, copies of contracts, and another sword of similar design to the one beside the desk. Except that that one was black and pitted and crudely made by hand, whereas the new one was of the best molybdenum stainless steel. Kilmer handed both swords over for inspection, remarking that the dazzling new one was superior to anything Toledo or Damascus had ever produced. Hefting each and noting the superior balance of the dazzling Anachron product, Barry wondered how any sane warrior could reject the later model.

Kilmer took the older sword and unscrewed the crystal set in its top. Underneath was a small receptacle of about the capacity of a thimble, hollowed out of the handle. The crystal atop the other sword would not come away until forcible prying got it off. Beneath was only the cement that had held the bauble.

"Knights," explained the sales manager, in his lugubrious tones, "especially crusaders, make the vanquished swear on the hilts of their swords to pay ransom, or to reform, or to render fealty or what not. You'd think that the crosslike shape of the sticker would serve, but it isn't good enough to suit a crusader. Oh, no. They've got to have this hollowed place to carry a few saint's relics in—you know, nail parings, a few hairs, dandruff or what have you. Somehow, it makes the oath more binding. Well, we ordered a lot of ten thousand forged, and now you know what happened. That Richard is a tough egg and I don't hold with him as a rule, but in this thing he's right."

The three of them together looked at the blueprints. The receptacle was clearly shown. It was mentioned in the specifications, and in the contract with Cumberland Steel, who made the swords. An inspection report was among the papers, stating the swords were as ordered. Mr. Kilmer picked up the phone again.

"Here's where a crooked inspector gets fired," he said, dialing the Chief Inspector, "and where Cumberland gets sued. It's the doggonedest thing to make these manufacturers realize that when we specify some wacky thing, we have a reason for it. They thought the receptacle idea was silly, and it saved them a couple of operations to skip it. Now everybody loses."

He swept papers off his desk and hurled the two swords to the floor, and scowled a moment at his new employees.

"You give credit to these... er... foreigners?" asked Barry, amazed.

"When we have to," admitted Kilmer, glumly. "Many of the things we value the most are locked up in palaces, cathedrals, or the treasure hordes of Hindu princes. They are not for sale. So we look along our own history line and find out when a particular place is to be besieged and sacked, then we contact the fellow who is going to do the sacking and make a deal with him. Usually by staking him to up-to-the-next-century high-grade siege equipment. Then we split the loot. Most times he prefers cash, which we have too much of, and we prefer the goods, which he is unable to transport."

"What about the ethics of that, and the effect on the future?" asked Barry, still hammering away at his pet question.

"Oh, that? So you're the worrying kind, huh?" glared Mr. Kilmer. "Take my advice and forget it. If Projects passes it; if Philosophy, Ethics and Prophecy give it the go-ahead, and if Budget and Research says O.K. and the Control Board says hop to it, you can bank on it it's being ethical. We've had more damn deals upset because some moony old coot in Ethics or some crapehanger in Prophecy claims the effects might be unjust."

Kilmer mopped his brow indignantly.

"Not long ago," he said, "I doped out a plan to sell Jeff Davis a lot of modern ammunition—I was in North American Recent then—but Ethics and Prophecy knocked it in the head. They said that the prognosis following a Confederate victory was not good and that we have to assume the moral responsibility for the sort of futures we set up in these branch time-tracks we generate, even if they have no effect on us. Well, you can see what a hole I was in—I could have unloaded thousands of tons of stuff. So I proposed selling to Lincoln and Staunton. But no, they said, that was just as bad. The computers took the land- grabbing tendencies displayed by the Republicans in the decades right after the Civil War and forecast the effect of an easy victory with weapons superior to anything else on Earth at that time. The prognosis of that was bad, too. Prophecy opined that the United States would embark on a spree of conquest that would ruin them in the end. Tough, you see?"

"Not quite," said Barry. The application of ethics to probable alternate time-track seemed a bit involved.

"Oh, bother," exclaimed Mr. Kilmer. "Take the rest of the day off and get that stuff out of your system. Go up to Philosophy, or if they're thinking and won't talk to you, go into Public Relations and ask them for the low-down. Find out all you can, because tomorrow I'm shipping you off to Thirteenth Century France for a shakedown run."

"Hell, I can't speak Old French," said Maverick.

"You'll be speaking it tomorrow," said Mr. Kilmer, cryptically, and pressed a button for a messenger, "but get out now and leave me with my headaches. I've got to tell a guy in the Projects section why we can't spare a man to get the thousand pairs of dodos the Zoo Commission is yelling for. The boy will take you to the places you want to go."

"Takes things hard, doesn't he?" grinned Maverick, once they were out in the hall. Barry grinned back.

"You know, fellow, I think we're going to enjoy this job," he said, quite irrelevantly. And then they took the elevator to the lair of the philosophers.

THE philosophers' room was an astonishing place. It was a

dimly lit but richly furnished library, about which lounged or

paced the floor with knitted brows more than a dozen men. Few

would have been taken for philosophers on the streets; several

were bearded and bespectacled and had a musty, scholarly look,

but for the most part they looked as if they might as well be

engineers or salesmen. But all had one thing in common, a deep

immersion in profound thought.

The philosophers' room was an astonishing place.

"Sh-h," cautioned the messenger, "don't speak until you are spoken to. They get awfully sore if you snap 'em out of it."

The first of the savants to show signs of life was an immensely corpulent gentleman sprawled in an easy-chair. His eyes were tightly closed and his face puckered into an intense frown that seemed strangely infantile in view of his shiny bald pate and the multiple chins beneath. But at length he gurgled faintly and the lines of his face relaxed into a placid smile. Then, quite slowly, he opened his pale-blue goggle eyes and steadied his gaze on Barry, who was standing in front of him respectfully waiting.

"A question?" asked the philosopher, after an expressionless scrutiny.

Barry started to state the doubts that troubled him, but the wise man seemed to divine the tenor of them after the first four words, for he at once closed his eyes again and began talking in a dull monotone.

"No reconciliation of the supposed time paradox is necessary," he droned, "for no paradox exists. For every possible past there exists an infinity of possible futures of which a certain number may be considered probable. But once a complete past has occurred, there is but one resultant future, and both it and its past are facts and immutable. Through the manipulation of certain ultradimensions by the application of gravitic and temporal fields of force, we know that we may inject extraneous incident into our past at will. But every such innovation, however slight, can have no subsequent effect along our own proper time-track. At the very instant of intrusion a new time- track is set up which will branch off and thereafter develop toward its own discreet future. Is that clear?"

"Approximately," answered Barry, though still a bit dubious. "But if these are divergent and independent branches, how does one get back—"

"As one gets off a railroad siding. By backing down to the switch point and then resuming the main line. At the moment, I was considering a means to cross these lines at right angles, especially since there may be independent time lines parallel to us of which we do not dream. For the present we must be content with shuttling back and forward over the well-worn track. But you tire me. One more question only; I have patience for no more."

"What about the effect we have on the futures of the new branch lines?" was Barry's final question.

"Bah!" snorted the philosopher. "What have I to do with such trivia? We deal here with the larger aspects. Go ask Ethics your other questions."

Before Barry or Maverick could mutter a word of thanks, the man had screwed his face back into its former expression of rapt concentration and forgotten them. The messenger crooked a finger and the three tiptoed out into the corridor.

THEY visited a number of other departments before the day

was over, though not all of Anachron's many subdivisions by any

means. The order in which they made the rounds was somewhat

haphazard, but by midafternoon Barry began to have some notion of

how the wheels of Anachron went round, at least in the Foreign

Department.

First, there was the requisition room, where orders poured In from all parts of the home world. The variety of things asked for was incredible and the quantities demanded immense. On the cultural side, where the universities, libraries and museums of the world were being rebuilt and stocked, there was demand for books of all kinds—not only the rare and priceless major documents of the past, but ordinary books for circulating libraries and for sale to homes. The demand for paintings, sculpture, laces and embroideries, and handicrafts of every sort was insatiable. The reconstituted zoos were planning prehistoric sections for which they wanted living specimens of all the animals since creation. On the industrial side there were many and varied demands, such as that for genuine silk, old cheeses and wines and many others.

Services had been requested, too. The geologists had asked for surveys to be made of the world at various wide intervals in the past; societies for the prevention of this or the promotion of that would petition to have their pet cause of the past assisted. Some wanted to turn modern knowledge over to the ancient Greeks without reserve, so that the Roman Empire could never come into being, while others favored the strengthening of the bands of the Bourbons to prevent the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror from happening. The files of the order room were crammed with proposed Utopias.

Needless to say but a fraction of the orders could be filled. The more feasible of the lot were culled out and sent to the Planning Section. It was there that the motto "Merchants, Not Missionaries" came first into play, for Anachron was a commercial organization having the double purpose of acquiring valued products from the past and disposing of the unwieldy surpluses of home production. Any other consideration was secondary, and the possible moral effects of any of its acts worried the planners very slightly.

What they approved went to Projects, for preparation and estimates. Then Prophecy had a look at it, and referred its findings to Ethics. If the projects survived that gantlet, it went to the Control Board for authorization.

Barry and Maverick soon became lost in the maze of operations that followed that, especially after the secretary in Control had given them a Field Man's Manual. Somewhere along the line one or more of the many Research Bureaus put a finger in the pie; then there was Design, Contracts, Credit and all the rest. They even learned there existed an office of Intertemporal Exchange, where excess byzants, ducats, lacs of rupees, talents and pieces-of-eight could be turned in for appropriate credit. They found that out when they reported back to Kilmer and he sent them to the office with an order for three bags of coins to cover the initial expenses of their trip. That night they opened one of the bags and found it to contain many deniers and obols, as well as gold coins from the Levant,

THE following morning Mr. Kilmer seemed a mite less dismal,

but he explained that by saying it was early yet and he had not

opened his mail.

And he shot the basket of incoming memoranda a glance that would have served equally as acknowledgment of the presence of a king cobra.

A new face was present. He was an undersized chap with beady jet-black eyes, and a fidgety, nervous manner. His name was Nelden, but what his nationality was was undeterminable. His title was "Advance Man." and it appeared he had completed the preliminary field arrangements for the execution of the newest project. Barry and Maverick learned to their consternation that as soon as he had conducted them to the spot and assisted in breaking the ice, they were going to be left alone and in full charge. Anachron believed in bringing up its field men the hard way.

"You'll do well if you get off by four, Nelly," said Kilmer, glancing at his watch. "You have to take these boys by and have them psychohyped and costumed first, so you'd better get going."

"Where are you going to send me when I come back, boss?" asked Nelden, anxiously.

Mr. Kilmer ruffled orders stuck on a hook.

"St. Petersburg, I think. Peter the Great is starting a big building project there, and it's a good spot for your construction gang now that you're finished in the Scillies."

"Yes, sir," said Nelden, with a dirty sidelong look at the two who were about to supplant him. They took it he was not overfond of medieval Russians.

They walked away. Nelden leading sulkily. Far down the corridor he turned and said, "Pretty soft for you guys. I do all the dirty work, case the joint, unscramble the dizzy calendar they use and work out the geo position. Then I get a concession for a castle and build it for you. Then I stock it with trade goods, train a lot of dumb marines how to find the way. After that I have to hand it to you birds on a silver platter. And I get a lousy salary while you fellows lap up the commissions!"

"Why don't you change your rate?" asked Barry, mildly,

"Too uncertain. And too damn risky," snorted the disgruntled advance man.

They turned into one of the interminable research wings until they came to the section they were after. Four or five men sat around a table, poring over antique tomes and manuscripts. In the corner a phonograph was rattling off fast dialogue in some foreign tongue.

"These fellows," explained Nelly, "bone up on local customs, lingo and all that. When I do my scouting I bring back records to show them how the stuff sounds when the natives sling it. There isn't any French or English or Spanish where you're going. Only dialects, and they change every fifty miles. Latin and Lingua Franca is about all you can really sink your teeth into."

"These the men?" asked a man wearing a doctor's smock, who had just come in, nodding in the direction of Barry and Maverick.

"Yeah. Hype 'em."

The doctor arranged a few chairs, set the novices down in two of them and several of the scholars and Nelly took the others. A dazzling little light appeared as if by magic in the ceiling, and the doctor directed them all to study it closely. Barry felt a momentary queasiness and promptly lost all sense of time. At x hours later he was aware of the chairs being pushed back and someone saying to him, "O.K, you've got it."

Without understanding quite how, he knew that he was passably fluent in several French dialects, church Latin, with smatterings of Flemish, Cornish, Navarrese and Arabic thrown in. Then he realized he had been hypnotized and while under had been pumped full of the acquired knowledge of the others. Vague memories of monasteries and castles he had never seen were faintly troublesome, but he supposed that was to enable him to recognize them when he saw them.

"Where's the bird?" asked Nelden, looking around. Then his eye lit on a cage in the corner in which a big green parrot was preening itself. "O.K.?"

"Hope so," shrugged the head language student.

Nelden unhooked the cage and made for the door, Barry and Maverick following. When they stepped out of the elevator at the ground floor, it was into a taxi bearing the company's trademark. "Freight Export," snapped Nelden, "and step on it." He planted the parrot cage squarely on Barry's lap and began jerking out hasty phrases:

"Bit of foresight... might get you out of a jam... barons are nuts about queer birds, like falcons, eagles... they never saw a parrot... this one curses fluently in Basque and Walloon... and prays interminably in bad Latin... ought to make a hit."

He caught a breath as the machine lurched around a corner and climbed a mound of fallen brickwork. "...'n lissen... I'm taking a couple of days off... no sense in going down with you... everything's set. Gotta charter from the Duke of Cornwall, tribute one gold bar and three fine cows a year... base castle's on one of the Scillies... partly stocked and with four good cogs. You open up France... establish a fair... hire peddlers... get a stand-in with the nobility and church. And watch your step. Don't get into fights. Don't get burned at the stake for heresy. Or sorcery... that's worst. Don't waste sympathy on the serfs, they're a bunch of ignorant bums. Merchants, not missionaries, you know. And the key word is mass sales. Rockefeller made more millions selling quarts of gasoline than Tiffany ever did with diamond necklaces. And don't forget ... if you don't show a profit by the end of six months... bam ... you're out on your ear."

He shut up with a snap of the mouth and stared out the window, while Barry and Maverick exchanged blank looks. This was being put on their own with a vengeance! Then Barry's face broke into a grin, which gave way to a hearty laugh. No wonder they insisted on ex-Commandos!

THE freight export building occupied most of the site

formerly taken up by Greenwich Village. Elevated railroad spurs

ran through the lower floors of the vast pile of buildings which

rose above them for many stories of blind warehouse walls. Once

inside they were whisked aloft and stepped out into a room of

astronomical dimensions. Barry had time only to glimpse the heaps

of merchandise of every description that stood about the floor.

Bronze spears were stacked up like cord wood, flanked by hoes,

rakes, plows and reapers. Elsewhere there were bags of sugar and

flour, crates of grapefruit and other foodstuffs. Literally

thousands of crates of unknown content were on every hand. Then

they came to a machine such as they had seen Jakie arrive on,

except this one was as large as a harbor lighter and was already

piled high with boxes, bags and barrels.

"Your shuttle," said Nelden. "Runs nonstop between here and your castle. It's the only way you can get down or up—those one-man shuttles are only for special duty. Don't ever lose touch with the castle, or you're sunk. S'long. Good luck."

He herded them onto the shuttle, and before they knew what was happening a gong was clanging and they felt a queer vibration. After that they seemed to sleep awhile when a series of mild jars brought them back to full consciousness. They were in a different place. It was a huge vaulted room—or cavern—aglow with floodlights, and the shuttle was nested between a pair of unloading platforms. At the blast of a mouth whistle, two gangs of gigantic Nubian laborers sprang forward and commenced snaking the cargo out. A gangling redhead strolled over, dressed in immaculate whites and Barry saw that he had a good old Colt strapped to his hip.

"Hi," greeted the fellow, "welcome to Isla Occidentalis. Suppose you're the traders. The cogs are loaded and ready—when do you want to shove off?"

"When we get our breaths," answered Barry, marveling now at his recent impatience with the slow pace of the indoctrinational school. Anachron may have been slow on the uptake, but they made up for it in the field. Then, feeling a few amenities were in order, he introduced Maverick and himself.

The supervisor of the unloading said his name was Clarkson. "I'm slavemaster and storekeeper," he added.

"Slaves!" exclaimed Maverick, horrified. He had just finished fighting a war for freedom.

"Why not?" countered Clarkson. "You're in 1240 now. These fellows are happy as larks and better off than they ever were in their lives. We got 'em from a rock quarry of the Carthaginians in the course of a trade, and they can't be disposed of up home. So we use 'em here to cut down the overhead. You'll find 'em handy; we've taught 'em all sorts of things—to cook, tap dance, play swing. The trades, too. The company won't send down anybody but people like us. We have to make out with local talent as best we can."

Barry grunted, and proceeded to inspect the castle. Isla Occidentalis was a glorified warehouse built in castle form. It occupied the whole of a tiny rocky island off the tip of Cornwall and its concrete walls rose sheer from the foamy breakers that pounded their foundations. Except for a water gate that admitted the clumsy cogs to the inner basin, there was no opening in the walls. Even that was guarded by an Anachron-designed portcullis sliding in well-greased guides. In that day of timid mariners and knights who feared the sea, the place was impregnable and needed no more than an occasional electric eye for guards.

Clarkson, they learned, was the chatelain, and was aided by a squad of six marines who saw that the slaves kept to their assigned quarters when not otherwise engaged. In addition there were quarters for such cog captains as happened to be at base, and accommodations for the traders and home-office visitors. All the rest of the structure was filled with storerooms, some of which were refrigerated. The place was full of flagrant anachronisms, but it did not matter, as no one belonging to the contemporary age was permitted to enter. It had been designed as a handy central shipping depot for the crew of other traders yet to come—men who were to work Granada and Moorish Spain, England and the Low Countries, and the Baltic ports. The name, Isla Occidentalis, was beautifully vague, meaning a land somewhere west of Ireland.

"I'd hate to be in your shoes," was Clarkson's remark over their nightcap later. "We've got a hellish overhead here, what with interest, amortization and all, and we understand that Audits & Accounts have been burning up Sales about it. Kilmer stays in a state of frenzy all the time. After four guys took a fling at that St. Denys fair he's so anxious to crack, only to bust at it, he's been hard to live with. He tried to sell Nelden the idea of taking over, but he wouldn't touch it. So—"

"So he picked a pair of greenhorns," Barry finished for him. I get it. Oh, well. We'll have a look. By the way, what cargo have those cogs got in 'em?"

"Everything but the kitchen stove. Your flagship's chock- full of miscellaneous what have you; the other assorted livestock. It's up to you how to use it."

THE week's voyage to the mouth of the Seine was not hard to

take. Parker, ex-commander of a submarine, was flotilla captain,

and delighted in pointing out the innovations he had made on the

tublike vessels. To the eye they looked like any other merchant

ship of the age, except they were fitted with rudders instead of

steering oars. But aerodynamics engineers had reset their masts

and redesigned the running gear, while the underwater lines had

been altered for the better. Under a secret deck auxiliary

Diesels pushed them along, wind or no wind, and there were

refrigeration machines for their perishables. That was a

surprising discovery, as Barry had been told that both internal

combustion engines and ice machines were forbidden to the Middle

Ages as being too far advanced for them.

"How would you keep that stuff secret if a war galley boarded you?" he asked of Parker.

"They wouldn't board us. We've got an ace in the hole. There is a submerged torpedo tube in the bow; it shoots the cutest little dummy torpedo you ever saw. The thing is only six inches in diameter and is electric-driven so it doesn't leave a wake, but it packs a wallop good enough to go right through anything now afloat. They'd simply sink and wonder what kind of sea varmint did it to them,"

"Oh," said Barry. He was getting a better idea of how you did things when the rule book made you pull all your best punches. Then, seeing the coast of France growing more distinct by the hour, he went down to dress and help Maverick with his costume. In his hurry to shove them off, Nelden had failed to take them to the make-up place, so they had looted their hold and found something that would do. The best description of what they ultimately decked themselves out in is that the foundation garments were silver embroidered Mexican vaquero suits, except that trench caps were substituted for the sombreros. As a concession to the contemporary taste for draperies, they topped the whole ensemble with Japanese kimonos worn open in front. Each tucked a bowie knife in his belt, a blackjack, and set of chain twisters—just in case.

As the low banks of the Seine narrowed on either side of them, their hypnotically acquired memory of the place refreshened. They knew without being told that they were approaching the first of a dozen tax- and toll-collecting stations that separated them from their goal, for a line of obstructions blocked the river, forcing them into a little channel close under the south bank. There stood a formidable stone tower, and on the bank a number of crossbowmen and archers led by a man in chain mail. The latter was beckoning the ship to come to him.

"This bandit takes an eighth of all you've got," growled Parker, telling the Nubian steersman to put over the wheel. "I wish they'd let us work on him like we worked on those Japs up the Yangtze—"

Just then Barry's ring finger began to burn. Anachron used the same type of self-contained midget radio sets as the Commandos had. Barry kept his eyes on the approaching beach, but his attention was on the succession of prickling dots and dashes that his finger felt. The message was being relayed from the Isla.

Kilmer to Barry: Ten days and no report of sales. Wake up and get busy. Quit paying out all the profits in tolls and start merchandise moving. Must have ample booth space at Lagny or St Denys fairs by Monday, your time. Acknowledge.

The tingling stopped. The first ship was already easing up to the bank where the big bearded gorilla in armor strutted impatiently. The cattle ship was hove to downstream, waiting. Barry had no time to analyze the disconcertingly peremptory message or reply, so he gave the stone in the outer ring a half turn and pressed out the code symbol for "acknowledge." By then they were bumping against the quay and the toll collector sprang aboard.

"Unload your wares on the dock," he bellowed, "that I may select that which is the lawful due of my noble master, the duke."

Barry thought of the heterogeneous cargo below and shuddered. Half choking he said, "If the noble master provost will deign, I will give him refreshment in the cabin below. There is a flask of the superwine made for sovereigns, and presents worthy of the honorable provost's fair lady. It will do no harm to let these villains and slaves wait while we parley. Unloading is so noisy, you know."

"Umph", grunted the brute in hardware, thrusting out a bulldog jaw. He was not too intelligent and he feared trickery. On the other hand, he had a keen nose for a hidden bribe and he, somehow, thought he sniffed one. He barked an order to his men and clanked into the cabin. Barry followed and tapped a little silver gong, whereupon a giant Nubian appeared, slickly black and nude except for a brilliantly spotted leopard skin about his middle.

"The goblets, Sambo, and the bottles—all of them."

He set out two massive silvery goblets whose handles were formed of elephant heads from which trunks curled down to rejoin the stem. They were rather impressive-looking ornaments to the table. The provost fingered his, then lifted it with a jerk of the arm that almost hurled it over his head.

"Mon Dieu!" he exclaimed, with his eyes popping, "what manner of silver is this?"

"The quintessence of silver, excellency, from which the base dross of lead has been distilled by silversmiths of far Occidentalis," said Barry. As for himself, he preferred less capacious vessels, preferably of glass, not aluminum, when he went in for a friendly snort. But he was in an experimental mood, and Kilmer's testy message had aggravated it. So something had to be done about river tolls, eh? Well! Barry pretended nonchalance as the messboy stood a row of bottles along the table top. Rye, Scotch, tequila and good red rum were there, and the boy had thoughtfully added a half gallon Mason jar full of yellowish, pure, fresh West Virginia moonshine.

"Precious and potent vintages these," said Barry, respectfully pouring out a beaker of Scotch for his guest, "fit only for warriors. A lowly merchant such as I needs content himself with ordinary wine. A lemon squash, please, Sambo, for me."

The provost started with an exploratory sip, then drained the cup at one gulp. There were tears in his eyes for a moment, for nothing stronger than a few drops of his master's new "medicine," or the recently invented crude brandy, had ever passed his lips before. But he mastered his tears and looked speculatively at the other bottles. The clear glass of the bottles and their perfect symmetry were marvels enough, but their contents surpassed them. He tried a shot of rum.

There were tears in his eyes for a moment.

From then on the conversation ran smoothly. It was chiefly monologue, devoted to the prowess in love and in battle of François Grospied, the worthy but ill-rewarded provost of a grasping duke. He reproached the duke bitterly for having exacted too high a price for farming out the river rights. "But," he assured, with an owlish wink, "I get mine, at that."

"I'm sure you do," agreed Barry, and crooked a finger for Sambo. To him he said in an aside, "See that the boys outside have something—the mountain dew will do; let 'em have a five-gallon jug."

Things looked better. Barry bethought himself of the present he had promised for the little wife, so he stepped to a cupboard and pulled out a box of assorted rayon stockings. It was a shotgun package, of various sizes and colors. He handed over a sheeny pair of brilliant green and one of hectic red, leaving the less passionate colors in plain sight in the box.

The bleary Grospied held up a pair, then held them up again, with colors mixed that time. "Marry," he said, "a sweet combination, eh?"

"Mix 'em any way you like," said Barry. "The box is yours."

"My frien'," assured Grospied, near to complete unbending. He missed Barry completely in the affectionate sweep of his arm, but fetched up against Sambo, snatching the leopard skin away in his clumsiness. His eyes bugged again, for the absent hide revealed a pair of purple velvet tights, glittering with spangles and held up by a belt of brilliants. It was an idea of Clarkson's, that little sop to his slaves' innocent vanity. Whatever the intent, its effect on Grospied was profound. He had to have another drink. Barry suggested okolehau, which up to that time had not been sampled.

A LITTLE later, when the genial Grospied lay slumbering on

the deck, Barry stole out onto the deck. Parker was leaning on

the rail thoughtfully regarding the sprawled bodies of the duke's

henchmen. The upended jug told the tale.

"For Pete's sake," said Parker, "what did you give 'em—Mickey Finns?"

"The next thing," grinned Barry. "But say, didn't you tell me that you had a special typewriter packed away in the event we should ever fall in with a cardinal?"

"Yeah. I'll have it broken out for you if you want it. There's a box of initial blocks and a pad that goes with it, too, and assorted sealing wax."

"Swell," said Barry, and he began trying to recall all the legal phrases he knew.

A little later he was sitting in the cabin again, pecking at a monstrous oversized typewriter that wrote in black Gothic letters an inch high. He carefully left a large space where the initial letter should be, and then wrote on without it, using the best grade imitation parchment he had on board. It was an agreement between one F. Grospied, provost of the duke, and hence the king, and one Anachron Inc., ambassador Occidentalis, granting —by right of Grospied's farmer- generalship—the perpetual free use of the river up as far as the confluence of the Oise. He stuck in carbons and made four copies. Then he surveyed his work.

Barry scrutinized the last line, "transito sano hoc flumen in perpetuam," and wrinkled his nose a little. Considered as Latin it probably stank, but what the hell! He selected the correct block to supply the omitted initial and stamped on an ornate one picturing a knight on a rearing horse sticking a groveling dragon. It was in a bright vermilion. Barry chose a stick of dainty pink from the box of sealing waxes, and another of baby blue. Then after lighting a candle, he went at the dirty work of getting the party of the first part, the aforesaid F. Grospied, to his feet. It couldn't be done. The gentleman was out. So Barry gently abstracted his signet ring and sealed all five copies with the pink, after which he restored the ring. Then he sealed for his own part, pressing the blue wax with a Chinese coin be carried as a pocket piece. Two of the documents were for the principals, the copies were for duke, king and pope respectively. Barry wanted no misunderstandings. So he tucked Grospied's and the duke's copies inside the slumbering provost's belt. After that he had Sambo and the cook carry him back to his men.

"Rather unmilitary looking, don't you think?" asked Parker, apparently fascinated by the proceedings, but referring to the haphazard arrangement of the snoring forms on the shore. Their dignity had not been enhanced by the addition of their chieftain, for Barry had kept the faith. An irregular pyramid of mingled colored stockings surmounted the sleeping warrior's chest and rose and fell with every labored breath.

"Uh, yes," agreed Berry. "Let's have 'em straightened out in rows. And to avoid hard feelings later, I guess we'd better leave another jug of lightning for consolation when they wake up."

When he went to borrow Grospied's standard, which had been left leaning against the castle wall, he relented further. He drew the corks partway in half a dozen bottles of good rye, and stood them, together with the rare goblet, alongside his erstwhile guest. After that he had the Grospied banner hoisted to his cog's peak to serve as notice to all upstream that the ships were under ducal protection.

"Let's go," he said, and then relayed the message to Maverick, who still hovered anxiously off shore, wondering what it was all about.

"Awr-rk," squawked the parrot, unexpectedly, from its perch on the poop. "A king's ransom, egad! Ora pro nobis. Ora, ora, orra!"

PROGRESS up the Seine was slow, for its lower courses were

sinuous and during many hours each day the tide was against them.

They would have made faster progress had they been free to use

their kickers, but for fear of stampeding the plodding serfs

along the bank—none of whom could probably stomach the

sight of a ship of the sea gliding along against both wind and

tide as fast as man might walk—they had to use the

auxiliaries sparingly. In places there were stretches of tow-

paths, and whenever they came to one of these, Barry would put

squads of Nubians ashore and give them the end of towropes. Many

a doughty knight must have gasped in admiration for those black

giants at seeing them trotting gayly along, dragging the heavy

vessels after them with such careless ease. In fact, the slaves

towed with such ease that Parker felt compelled to ring down a

few revs—to avoid the occasional embarrassing moments when

the trotting blacks couldn't keep ahead of the slack.

Progress up the Seine was slow.

They passed many towers where rivage was collected, but their borrowed banner protected them from molestation. Barry computed that if he had paid an average toll of three percent at each of them, together with the future taxes of every kind that lay ahead, he would arrive at Paris with empty holds. He understood then why the previous expeditions had failed. His coup over Grospied was a pretty good victory at that, and the thought of it bucked him up when next he answered Kilmer's daily "hurry- up" demand.

Have a heart, boss. Sure, we've been two weeks on the voyage—you can't fly from the Scillies to Paris. We're nearly there; our cargo is intact; we've spent no money; and we've got a perpetual free pass to the lower river—and that ain't hay.

The boss snapped back:

No, it ain't hay, but breaking even ain't making profits, either. And wait until you knock their eye out at St. Denys or Lagny before you get fresh, young man.

"The dope," muttered Maverick. "Why don't he go down to Research and get a hype, too. He keeps yelping about St. Denys and Lagny, when all these shindigs are seasonal affairs. Lagny closed up shop for the year in February; St. Denys is a fall show. This is June. How could we sell out at either by last Monday?"

"Oh, well," shrugged Barry, indifferently, "let him rave. All he wants is sales, and if he's like the breed I used to know, he don't care when or how we get 'em—"

"I didn't know you'd ever sold," said Maverick.

"Sure. Before the war, when I was a kid. Vacuum cleaners, cemetery lots, grand pianos—"

"Ouch! O.K., buddy. You're chief from now on. Anybody who can sell cemetery lots is a better man than I am."

Barry was about to admit be hadn't actually sold many when the vessel went round a sharp bend and there was another castle barring the way. This one flaunted the white banner of the King of Īle-de-France. An arbalest quarrel zipped through the rigging, signifying that the colors of Grospied didn't mean a thing to them. Barry groaned.

"The jig is up. This must be France."

FOR several days they had been running through the hazy zone

that was either English or French, depending upon how you looked

at it. Its suzerain was the Duke of Normandy, a French duke, and

therefore a vassal of the French crown. Yet that same duke was

likewise King of England, and therefore no man's vassal. Try as

they might, the boys could not unravel the intricacies of

jurisdiction. So they meekly halted their ships and commenced the

haggling over the amount of douane they should pay. The tariff to

be paid at the border of a kingdom was over and above any river

or road tolls. The provost's deputy was both a stupid and greedy

man. A dozen golden livres satisfied him, and he let them go.

After that, they found, they would have to pay the river tolls

above.

They cast off and stood upstream. Then they held a council of war.

Someone, probably Dilly, captain of the cattle boat, suggested that to avoid the heavy rivage it would be better to tie up somewhere and proceed further by land. At once a howl from the others arose. They had an idea of what land travel was; moreover, they didn't have to live on a ship with bawling cows and clucking fowls.

"That's worse," ruled Barry, finally. "You pay a transit tax to every castle or monastery you pass, plus extra for the use of fords and bridges. Every baron has his hand out for the telonia, which is the land equivalent of the river tolls. That's not all. The roads are trails—quagmires when it rains; there are bandits everywhere, and sneak thieves galore. What's worse, we'd need scores of mules to carry our cargo, and we haven't that many. No, that's out. We'll stick to the river."

It was a noble resolution, but destined to be broken. They stuck, but "in," not "to." A day later, two toll stations up, they were scarcely two hours past their last big castle when the leading cog poked her nose in a submerged mud bank and stayed there. The other sheered out into what looked like better water; and it stuck hard and fast. As far as they were concerned, they were at the head of navigation.

"Shucks," muttered Barry, as he hung over the taffrail watching the seething mud kicked up astern by the struggling little propeller.

IT was midafternoon when they got off, and night was falling

when they got back to the nearest castle. They obtained

permission—by shelling out a handful of silver

deniers—to tie up to the funny little quay beside the toll

tower at the river's edge. It was a detached outwork, for the

castle itself stood on a low plateau inland about half a mile and

some several hundred feet above the water. Tomorrow they would

have to beard its baron in his den and induce him to be their

patron. Somewhere, sometime, they would inevitably have to have a

terminal where they could erect a warehouse. It seemed that this

was the place, and the time was now. There was no choice about

it.

The four ate their supper in a subdued mood, each thinking in his own fashion of the changed situation that lay ahead. It was not that they were downhearted, for men of their breed seldom get that way. They were merely thoughtful. After the coffee, Barry broke out the bottles and quietly filled the glasses around.

"Oh, well," he said, "here we are. Now, let's see—"

It was pitch dark outside by then, and the black mass of turreted Capdur chateau loomed unblinking on the hill above them. In its age people went to bed at darkfall and arose at the crack of dawn. Tomorrow they would visit the castle—and be received, for baronial hospitality was the universal custom. Man of whatever degree was welcome, each according to his rank. But baronial hospitality expected something in return, again according to rank—from the villein, labor; from the wandering jongleur, a few entertaining tricks; from merchants, samples of their wares; from the nobility, presents appropriate to their stations.

"We are merchant princes," announced Barry, gravely, "trot out the invoices and let's see what we have to give. First impressions, you know—"

IT was near midnight when the last item had been jotted down

on the list, and it was a faintly hilarious party that bade each

other good night and went severally to their bunks. And it was

near to nine in the morning when the last box came out of the

hold and was strapped to the packsaddle of one of the three

sturdy she-asses selected for the parade. The ten Nubians chosen

to go along were resplendently dressed. Their bodies were oiled

to glistening blackness, and in addition to their beloved

spangled tights, they wore beaded Indian moccasins and the full-

feathered war bonnets of Sioux chieftains. Barry and Maverick

mounted the two smart mules that had been saddled for them, and

the cavalcade set out up the winding road that would take them to

the castle.

They presented an eye-filling spectacle indeed, as attested by the excitement of the native children who ran along beside them, shouting and pointing. Villeins who happened to be along the road stepped respectfully to one side and watched with mouths agape as they went by. By the time they reached the summit of the hill and turned toward the castle on the plain ahead, they saw that a great crowd, warned by the runners who had dashed on ahead, had gathered by the gate in the barbican to await their coming.

The weird, outlandish procession was headed by Barry and Maverick, riding abreast, flanked on either side by a giant Nubian. The Nubians carried what to local inhabitants were queerly bent tubes of shiny gold having some resemblance to their hunting horns. After the leaders came the three pack animals, each loaded to capacity, the last one bearing panniers from which protruded strange comestibles—loaves of bread, corn pone, stalks of celery, and other things. Behind them came three more of the Nubian musicians, again walking abreast, the middle one having a horn stranger even than the others, shaped like a malformed gourd, and cluttered with silver wires and disks. The one on the right carried several barbaric drums, slung on a rope about his neck, while the left-hand man bore a Gargantuan viol on his back. Last of all came another black leading a magnificent Hereford steer, the like of which no Frenchman had ever seen, since it was taller and fatter by far than the best of their own scrawny breeds. And alongside him marched the ultimate Nubian, whose studied dignity was considerably impaired by having to break ranks from time to time to bring back to the fold one or the other of the three stately turkey gobblers he was shepherding.

Thirty paces before the gate, the procession halted. Barry lifted a finger and the two foremost musicians stepped forward and raised their bizarre instruments to their lips. They sounded a wondrous fanfare, shifting uncannily from key to key in flat defiance of all known laws of hornry. Just before the final grand flourish, the trumpeter sang out a long, sustained thin note while his squirming mate ripped off a sequence of rasping trombone tears. If Old French lacked the equivalent of the word "wow" until then, those present invented it on the spot. Never had there been such trumpeters; not even had the king himself had such, when he came to Capdur two years before

The two foremost musicians raised their bizarre instruments to their lips.

The fanfares over, the procession moved on. The crowd at the gate opened a lane for them, and since no one impeded, they went on through. Barry glanced at the crude stockade of pointed tree trunks and made the mental note that its purpose would be served as well or better by cyclone fencing. He must order a few thousand lineal feet of it. And then, as they crossed the tilting ground, he studied the battlements of the outer wall of the castle with a professional eye. He looked at the towers and their embrasures and the moat of stinking, stagnant water that made them hard to get at. Instantly be conceived the proper mode of attack. Instead of the cumbersome beffroi towers which besiegers built and pushed forward in order to top the walls and span the moat, he would employ a modified version of the standard hook-and-ladder fire wagons. An armored cowl would do the trick, with a hatch in the carapace through which a swiftly extensible ladder could he upreared. It would be a cinch to get a foothold on the walls with a few such vehicles.

The drawbridge was down, the portcullis up, and the gates open. So they clattered across the bridge and under the gloomy arch. Again Barry's inventive mind was running away with him. Instead of the clumsy timbers of the bridge, suspended by heavy, rusty chains, he would substitute a light bascule span of duraluminum, counterweighted so that a boy could operate it by grinding a crank. He wondered whether there was any chance of selling the medievals the idea of standardized sizes. At any rate, his next requisition on Kilmer would contain a number of curious recommendations.

They emerged into the bailey, or outer ward—a huge courtyard bustling with activity. It stank of manure, unwashed humanity and the smell of burning wood—a not altogether unpleasant combination, for in addition to the stables and blacksmith shop and the mews where the hawks and falcons were kept, there was a big communal oven and an open ditch filled with fire over which the spitted carcasses of pigs and sheep were being roasted. Chickens and peacocks and hogs roamed the inclosure, pecking or rooting among the ordure piles; naked children played amongst them, stopping only long enough to stare with their amazed elders at the strange procession passing through.

Barry led on, since still no one had appeared to greet them or to bar their way. The farther wall of the bailey was the outer wall of the castle proper, higher and stronger than the first wall and better turreted. It, too, was guarded by a moat, but again the drawbridge was down and the way open. The surly porter lounged against the stone portal, but made no move to stop them. So they entered the great paved court of the castle, mules, steer, turkeys and all. And there they were met by a flustered squire. His master wanted to know the meaning of the astonishing fanfare of trumpets that had heralded their approach. Were they, perchance, gentry incog, or the mere merchants they seemed to be?

"Both," said Barry, calmly, with a touch of hauteur. "In the land of Terra Occidentalis the merchants are the gentry. We are skilled in the arts and sciences and the use of weapons, and are not to be treated lightly. But we are come as friends, to pay our respects to the baron, and we have gifts for him, his lady, and his household. Pray inform him."

The squire surveyed the halted cavalcade and looked troubled. It was something for which there lacked precedent. So he bowed stiffly and begged them to remain where they were, then scurried away to fetch the baron in person. Barry and Maverick dismounted, as etiquette demanded, to await their host

The Sieur de Capdur was a mountain of a man, of dark complexion and beetling brow, but though he had the arrogance born of a lifetime of undisputed command, there was a rough-and- ready joviality about him that was appealing. He brushed away the formalities of greetings with a brusque question.

"You have presents for me?" he asked, getting straight to business; "fine," and he looked appraisingly at the laden donkeys. His lady, the slender and fair Yvonne, joined him with a group of maids, and in his train had come the gaunt old seneschal, his marshal of horse, his provost, and other officials of the house. They gathered eagerly about the newcomers in a semicircle, backed by the small fry of the chateau who had crowded in from the bailey and were craning from behind. Merchants from afar did not often stop at Capdur; it promised to be a gala day.

"O.K.," said Barry, "I'll be Santa Claus," and he began undoing bundles. Meanwhile the Nubians in the rear had brought up the animals, which Maverick presented with a flourish. The steer received unstinted admiration, but it was the gobblers that aroused the greatest delight.

"What bee-yootiful pheasants!" chortled Lady Yvonne, as one of the creatures strutted past, ruffling its tail and grumbling in its craw.

"Turkeys, lady," corrected Maverick, "and they're good to eat. We brought along our chef and the fixin's so you won't go wrong on how to do them." Whereupon the herders of the beef and turkeys, and the leader of the third ass, at a signal from Maverick, made off toward the bailey to prepare the evening meal. They had, in addition to the materials for stuffing, cleavers, roasters, grills and other accessories.

THE ceremony of presentation took up the whole of the

morning. Both Barry and Maverick were busy dishing out the gifts,

and demonstrating their uses when necessary. They dealt them out

in fair rotation, allowing each givee ample time to play with his

new acquisition before swamping him with another, but the

distribution ran so:

To the Sieur de Capdur: a pair of ten-power, prismatic binoculars in a handsome carrying case; the mate to friend Grospied's drinking mug; a roulette wheel and folding layout, together with an adequate supply of chips; two bottles of Bacardi rum with silver-handled corkscrew; and lastly but not least, a homemade slot machine built by Parker to while the time away. It was a thing not on the Control Board's approved list, but the Sieur de Capdur didn't know that. For his part, all barriers were down when he learned that a quarter of the take went to the house.

"Zounds!" he roared, "my fief holders wail about the taxes. We shall have their taxes, O wise merchant, and place one of these machines in every hamlet of our domain. 'Twill have the same effect, or better, if I know the varlets, and reduce the volume of their bellyaching."

"Truly," said Barry, winking knowingly, and then went on with his distribution of gifts.

To the Lady Yvonne, who had had a chair brought, and was sitting among a cluster of twittering doncelles, he presented first a five-pound box of assorted chocolates and bon-bons. She fondled the glistening box uncertainly, until he rudely broke the precious cellophane wrappings and exposed the contents. Amid a chorus of oohing and ahing they sampled them. Chocolates and cocoanut were unknown to them, and sugar only as a novelty, horribly expensive and in crude lump form, as brought back from the Levant by the crusaders. When the excitement over that died down, Barry passed out hand mirrors—a tremendous advance over the polished bits of silver they had been using—lipstick, rice powder, and perfumes in crazy little ornate bottles. To the maids in waiting Barry gave quantities of costume jewelry of the five-and-ten grade, but enormously attractive, nevertheless.