RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Astounding Science Fiction, January 1943, with Barrius, Imp.

A sequel to "Anachron, Inc." A tale of business—a peculiar sort of business—and ancient wrongs where laughing-gas and sudden death are crossed up.

THE three days' leave at "home"—"home" meaning New York of 1957—had done Mark Barry, erstwhile major of Commandos but now trader extraordinary for the great Anachron company, a world of good. He strode through the main doorway of the home office building on Wall Street full of eagerness to get on to his next assignment. That, Kilmer, his sales manager, had said, would be as manager of the station in ancient Rome.

He gave no more than a passing glance at the throng of businessmen passing in and out of the building in their eternal quest for contracts. Nor did he pause this time, as he had on his first visit, to wonder about the many queer departments housed above. For he knew now something of the intricacies of intertemporal trade, and the meticulous care that Anachron took to avoid unduly upsetting the economies or cultures of the less civilized peoples and eras with which they dealt.

When he reached the floor on which Kilmer's office was, he stepped out of the elevator and walked briskly down the hall, humming cheerily as he went. But he stilled his inward song the moment he was inside Kilmer's office, for that gentleman was sitting dejectedly at his desk, gnawing his fingers and scowling at a piece of paper on his desk. Barry knew already that his boss had long had the conviction that the business of intertemporal trade management was just one perpetual headache, and it was painfully clear that on this particular morning the managerial head was aching at one of its peaks. Kilmer acknowledged his entrance by a morose stare, then waved him wearily to a chair, after which he resumed glowering at the document that had furnished his daily upset. Presently he flipped it across to Barry.

"That's gratitude for you," he said, bitterly, and slumped deeper in his chair while Barry read the flimsy. It was an IT ethergram, dated at Rome in the year 182, routed via "Atlantis" base on Pantelleria.

WHAT DO YOU MEAN I'M FIRED YOU CAN'T FIRE ME YOU BIG STIFF STOP O.K. SHUT OFF YOUR DAMN SHUTTLES AND SEE WHO CARES I'M SITTING PRETTY STOP OR IF YOU THINK IT'LL GET YOU ANYTHING SEND DOWN ONE OF YOUR BRIGHT YOUNG MEN TO HELP ME RUN THINGS I'M TOO BUSY TO BOTHER STOP PATRICIUS CASSIDUS SEN ROM

Barry laid the message back on Kilmer's desk and raised his

eyebrows in silent interrogation. Kilmer sighed heavily and Barry

thought he was on the verge of breaking down and weeping.

"That is from Pat Cassidy, our Roman representative—the guy you were supposed to relieve," explained Mr. Kilmer in his lugubrious monotone. "I picked him up in the depths of the depression, a jobless down-at-the-heels peanut politician. I gave him the best job he ever had. I made him filthy rich. And this is what I get."

Barry still did not say anything. The situation was far from clear.

"But it's not the personal angle that's biting me," Kilmer went on, "it's the business aspects of the mess. Nothing like it ever happened in our organization before. Up in Ethics they're wild, the Control Board is having fits, and the Disciplinary Committee keeps burning me up and asking me why can't I control my men. Export-Import horses me about quotas, but when I pass 'em along to Cassidy all I get is silence. I order him up here for conference and he won't come. Finally I tell him he's fired—and I get this. Hell!"

"But," asked Barry, "what's it all about?"

"Look," said Kilmer, significantly, dragging out a ponderous file. "It made some sense when it started out, but it gets screwier with every order."

Barry took the order file and riffled through it. In the first years, when Cassidy pioneered the Roman branch under the emperor Marcus Aurelius, his orders were what were to have been expected. Anachron exported to Rome vast quantities of modernized armor and weapons—drop-forged, chrome and molybdenum alloy stuff—enough to equip ten full legions from helmet to sandals. There were tons of Portland cement, hand-operated winches and capstans, derrick fittings and cordage for the harbor improvements at Ostia. Wheat and flour used to flow by the thousands of bushels, in return for olive oil, native wines, and especially marble statuary. Then, of a sudden, the nature of the orders underwent a sharp change. Instead of their being for the huge quantities desired by Anachron, they called for scattered items, a few of each, such as a pair of dental chairs, five complete sets of surgical instruments, or ten old-fashioned fire engines with hose and pumps to be operated by willing backs. The only quantity requisitions were two in number: one for twenty tons of the drug afeverin— a sulphanilimide compound similar in properties to quinine but far more effective—and an astonishing order for ten million additional plastic poker chips.

"During the entire last quarter," Kilmer wailed, as Barry handed the file back to him, "he hasn't sold one schooner load of stuff. We have forty fine two-masters rotting at their piers at Pantelleria waiting for something to carry. Still the overhead goes on while that guy fools around with piddling orders for poker chips and drugs. Can you beat it?"

"Must be a reason," ventured Barry. "Maybe Cassidy is playing a deep game and isn't ready to spring it."

"Maybe," said Kilmer, dismally. "But you haven't heard all. There is more to this than meets the eye. When we decided to open up a branch in Rome, we selected the island of Pantelleria for our secret base—it is not far from Carthage and centrally located as regards the empire. Cassidy sold the Romans the idea that he was from Atlantis and that his ships came all the way in past the Pillars of Hercules. It was a good idea—too good, for the Romans recognized him as a kindred sort, having similar customs and religion, and made him a citizen of the city. For an ex-politician like Cassidy, that was all he needed. I suspect he started some side lines that turned into rackets, but anyhow it was not long before he was rolling in dough. Then he upped and married the widow of a rich Roman senator, and on top of that wangled a seat in the senate for himself. That was bad enough, but old Marcus Aurelius kicked the bucket and a no-good playboy by the name of Commodus became emperor in his stead. Pat Cassidy and Commodus are buddies. That tears everything."

"How come?"

"If we fire Cassidy, he says he'll have our charter revoked. If we stop sending shuttles, Commodus will confiscate our warehouses and ships. Control says we have too heavy an investment down there... mustn't do that... have to do it some other way."

"Yeah," said Barry, softly, "I begin to get it."

He stirred in his seat and stared at Kilmer as the full implications of Cassidy's rebellion unfolded in his mind. Under ordinary circumstances Anachron had a sure-fire means of bringing a recalcitrant employee to terms. They had only to threaten to shut off his shuttles and leave him stranded wherever in time he happened to be, but until Cassidy became so enamored of ancient Rome, no other employee had shown symptoms of going native. Nobody conditioned to the twentieth century relished being marooned on the sawed-off stump of a branch time track in some barbaric age. In the Cassidy case the company would only be cutting off its nose to spite its face, for they would not only lose their properties at Atlantis, but also the buildings at Ostia and in Rome. Moreover, it would be ineffectual, for Cassidy wouldn't mind it in the least.

On the other hand, if the company fired him only to leave him at large in Rome, it would have an awkward situation on its hands, even if he did not carry out his threat to confiscate the properties. His successor would have as an adversary a renegade from his own century who was a disgruntled ex-employee to boot. He could not hope to get away with the pleasant little fictions employed by Anachron salesmen in other places and ages—for Cassidy knew all the answers. Also, there would be nothing to prevent him from divulging to the Romans various secrets hitherto forbidden by Ethics and the Policy Board. Such items as explosives, power machinery and electricity were on the list. Yes, it was pretty obvious that Cassidy's attitude posed a problem.

"What," asked Barry, "are you going to do about it?"

"He says here," Kilmer replied, "that he will accept an assistant. That's you. Go down there and build the business back to where it ought to be. That's job number one. Then get Cassidy."

"Get him? Bump him off?" Barry thought that was going a bit strong.

"Oh, no. Not necessarily. A snatch will do. There ought to be plenty of jobless thugs and assassins roaming the streets hunting work to do the rough stuff for you. But I want Cassidy up here in this very office. Whether you talk him into coming or send him up in chains is all one to me. That is up to you—"

A messenger came in and deposited a memorandum on Kilmer's desk. It had a lurid red "Urgent" tag clipped to it. Kilmer read it and passed it on to Barry. It was a general order, effective at once. The memo read:

In view of a recent embarrassing situation in one of our important branches, the following rule is promulgated.

RULE G-45607: Hereafter, any Anachron employee who accepts any public office or honor in the era in which he is operating will forthwith be discharged and abandoned in that era. This penalty will be applied invariably and without regard for the magnitude of the company's investment in that era, the employee's previous good record, or surrounding circumstances.

"That means 'keep out of politics,' " said Kilmer. "Watch your step."

"I'll watch it," said Barry.

Within an hour he was ready to leave. A brief visit to the Roman room in the research wing fixed him up as to the special knowledge he would require. A skilled hypnotist put him en rapport with a pair of savants, and Barry arose shortly thereafter with his brain packed with magically acquired knowledge. He was familiar now with Roman laws and customs, and able to speak fluently in Latin and Greek. They also gave him a smattering of Aramiac, Gaulish, and the commoner Punic dialects in the event he had need to visit the provinces. After that a short stop at the costume room fitted him with a snow-white toga of fine linen for Roman summer wear—far lighter and more comfortable than the woolen ones the Romans wore. Then he went down to the shuttle room.

It was an interesting place, and one he had never seen before. True, he had made a round trip to Medieval France, but that had been on one of the big freighter shuttles operating out of the huge Export-Import warehouse uptown. The room he was in at the moment was a different sort of a terminal. Here was where the small one and two-passenger shuttles took off with special messengers and others sent abroad by the Home Office direct. Barry handed over his pass to the dispatcher in charge, and sat down to wait.

The room was large and divided in half by an iron rail which barred the passengers from the landing platforms. There were eight of those, each stall separated from the others by other iron rails. From time to time a shuttle would appear briefly in the space set aside for it, and its passenger would either step on or off, as the case might be, and the shuttle would vanish. Many of the travelers wore outlandish garb, even as the be-togaed Barry did. One resplendent creature stepped out of a shuttle wearing a suit of quilted cotton armor and a gorgeous headdress of colored feathers. His face was painted with vivid colors to a tigerish make-up.

"Hi, Steve," greeted another man in the waiting room, this one dressed as a Chinese mandarin. "How you doing? Where you been?"

"Tenochtitlan," said the one with the Aztec getup. "We're trying to get an in with Montezuma before Cortez gets there and gums the works."

Barry was curious as to the exact workings of the shuttles, but he knew that was a secret he was not likely ever to know. One of the most inflexible of Anachron's many rules forbade that information to all but qualified shuttle operators. And there was a good reason for it. Before it had been made, in the early days, each trader was allowed his own, but there were accidents. Twice embezzling agents hopped into their machines with their loot and departed deep into the past for destinations unknown. On another occasion a salesman whose sweetie had a yen to meet Marie Antoinette undertook to gratify her. They borrowed a shuttle on a Sunday afternoon with the announced intention of crashing a garden party at Versailles. Whatever happened, they were never seen again. Then there was the time when four ex-employees, fully armed with hand grenades and submachine guns, invaded the big warehouse and swiped a heavy freighter. They said they were only going to Lima to lift the Inca treasure from the Spaniards and would be back in an hour or two. They did not show up again. So Anachron thought it best thereafter to restrict the knowledge of how to operate the intertemporal vehicles to a tried and selected few.

At length the dispatcher called out, "Special shuttle for Ostia... leaving berth six in five minutes—" and Barry hitched his toga about himself and made ready to shove off. A little bit later he was stepping out of the shuttle in a small steel-walled room which had but a single door. Beside the door was hanging the receiving end of a scanner.

"End of the line," said the shuttle operator, flicking over his controls. "If the coast is clear, step out that door. It has a spring lock and will lock itself behind you."

"How do I get back in here?" Barry wanted to know.

"Mr. Cassidy has the keys," said the operator. There was a click and a whir and the shuttle and operator vanished.

"Sweet, I must say," muttered Barry, glaring at the vacant floor. Then he picked up the scanner and peeped outside.

All there was to be seen was the huge dim nave of an almost empty warehouse. Barry went through the door and picked his way among the few stacks of barrels and boxes, looking for an outer door. The big main ones were closed and barred, but he found a bricked-off cubicle he took to be the warehouse office. That he entered. Inside there was a desk and chair. On the chair sat a good-looking Greek slave boy, leaning tilted back and with his feet sprawled out on the desk, reading what appeared to be an absorbing scroll.

"Where's the boss?" demanded Barry, seeing the fellow did not look up or take any other notice of him.

"How would I know?" answered the slave, without taking his eyes from the script. Instead he twirled the knobs and exposed a fresh page. Barry's outthrust foot neatly knocked the chair from under, and hardly had the flunky hit the floor before he found himself lifted by the scruff of the neck and shaken vigorously.

"Where is Cassidus?" roared the angry Barry.

"I...I c-can't tell you, sir," moaned the Greek between chattering teeth. "He might be in the forum, or again at the palace or the senate. Or he might be at home up on the Viminal, or at his villa at Tivoli, or at his slave ranch down the Appian Way, or—"

"How am I going to find him?" reiterated Barry, renewing his shaking.

"G-go to the temple of Hermes two squares down the street," answered the miserable slave. "Not the orthodox Hellenic one, but the Atlantian shrine. Make an offering. Hermes knows."

"Hermes, huh?" growled Barry. "What do you mean, offering?"

The warehouse clerk fumbled in his tunic and brought forth a pair of blue chips. He handed them both to Barry.

"One of these ought to be enough," he said.

"All right. Call me a taxi...er, litter, that is," said Barry, pocketing the chips. They were beautifully made—a typical Anachron product—being of a pearly, jadelike plastic and having a white fleur-de-lis inlay. They were light, glossy, and unbreakable. Then he followed the boy out onto the quay and climbed into a litter that happened to be passing at the very moment.

Barry felt very lordly as he lolled back in the cushions and was borne along jigglingly by the four husky porters. He cast his eye over the harbor improvements and approved. Neat concrete quays lined the basin, and out at the seaward edge ran an efficient-looking breakwater. The warehouse he had just left was Anachron's own, built to house its wares before business declined to its present sad stage. Then Barry saw a fading sign nailed to a derrick. It announced to the world that the harbor improvements of Ostia were being made by Patricius Cassidus, contractor.

The litter drew away from the water front and into Ostia's main street. As he approached the temple for which he was bound, Barry noticed with some surprise that above the pediment there were stretched some very familiar looking wires. But he asked no questions of the bearers, and let them deposit him at the door.

He found the inside of the temple somewhat surprising, it was not in the least in conformity to the hypnotic picture given him by the scholars. The place had more the appearance of a modern bank or steamship office than a temple to the messenger of the gods. Inside the door were two marble benches along which sat a number of urchins, most of whom wore sandals to which roller skates were attached. They looked to Barry like messengers waiting for a call. A little way inside a marble counter barred off the rest of the room. Beyond it stood a heroic figure of the god himself, complete with winged shoes and winged helmet. But, incongruously, between his feet sat a modern cash register, and cut into the pedestal below there was a mailing slot.

A robed priest stepped up to the counter wearing an ingratiating smile.

"A petition to his godship, sir?" he asked.

"I suppose so." said Barry, uncertain quite how to proceed.

"Local or long distance?"

"I'm not sure."

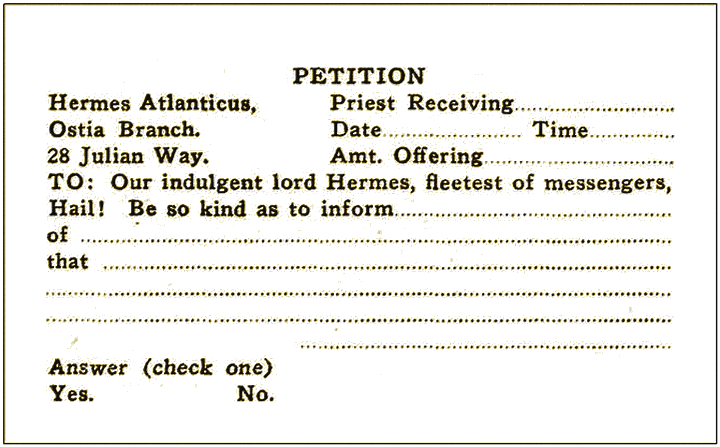

"Fill this out, please," said the priest, and pulled out a pad of printed forms from beneath the counter. He shoved it across and handed Barry a stylus. Barry looked at it, and there was a grudging admiration in his eyes. It was just the sort of thing he would have pulled if he had thought of it first. It looked like this:

Barry filled it out, leaving the address blank. Surely, the

priest knew Cassidy! The message simply stated that one Marcus

Barrius wished the honorable senator to know that his new

assistant had arrived from Atlantis and what to do? Then he

handed it to the priest.

The priest read it through carefully, counted the words, pursed his brows for a moment in heavy thought, and then mentioned a number of sesterces. Barry had completely forgotten to supply himself with Roman money, but he had the odd gift of the Anachron warehouseman. Without a word he produced one of the blue chips and offered it.

"Ah," said the priest, with apparent delight.

He fondled it a moment admiringly, then rang it up in the cash register.

Barry's petition was deposited in the slot, and somewhere behind the scenes came a faint bong. The amount of change that Barry got from his chip was amazing—one golden aureus, and a handful of lesser silver and copper coins. Blue chips, seemingly, were well thought of in Rome.

Barry stood back from the counter as other supplicants came up to file their petitions. The cash register clanged often as offering after offering was dropped into its drawer, and the little gong in the back rang as frequently. Above those sounds Barry's keen ears caught the telltale buzz-buzz-buzzity- buzz of a sending key, and he smiled inwardly at the sound. At last the priest beckoned him. He held a bit of paper in his hand which he did not deliver, but which he studied with a slightly bewildered look.

"Hermes has favored you greatly," interpreted the priest, "and sends you further tidings. The words are occult—aye, barbarous—but perhaps you will comprehend. Thus speaks the swift messenger :

"CROOK AN ELBOW WITH ME AT THE PALACE OF FORTUNA, CHOWTIME TONIGHT. SKIP THE WHITE TIE. TELL THE DRIP THAT'S WAITING ON YOU THAT YOU BELONG AND MAKE HIM KICK BACK THE ANTE. WHEN WE CHIN, IT'S ON THE HOUSE. PAT."

"Thanks," said Barry, and started to turn away. But the priest

continued to stare at the flimsy in his hand with an unhappy

expression.

"Chowtime? Drip? Chin—on the house?" he queried anxiously.

"Forget it," said Barry. For that matter the chip he had paid with had been on the house, and he was grateful for the hard money he had in change. He still had to have himself transported up to the city.

"How do I get to the Palace of Fortuna?" asked Barry, to take the priest's mind off the puzzling message. At once the priest brightened. Until then he had had a vague feeling that somehow the communication from Hermes contained a veiled reference to him, but apparently he had misread the Atlantian jargon.

"You can't miss it," he said. "It is the only place in Rome that is lit up at night. It is across the way from the coliseum—just follow the crowd."

"Thanks," said Barry, and walked away.

As his litter was carried down the street he stuck his neck out over the edge and looked back. From that point he could clearly see all of the small marble temple and its anachronistic crown of ruddy antennae.

"Racket Number One," he chuckled, "and a honey!"

The Palace of Fortuna was not misnamed. Or rather, it was undeniably palatial, though in some quarters the Fortuna part might be debatable. It was garishly lit by gasoline flares such as are used in tent shows, and stuck out in the dark streets of Rome like a Times Square in the heart of Podunk. Hordes of Roman sports were converging upon it, borne in litters, or staggering along on foot. It was an odorous mob, heavily perfumed and marcelled after the afternoon session at the baths, and it was clear that its members were on pleasure bent.

Inside, Barry was at once confronted with more of Cassidy's ingenuity, for he was beginning to recognize his touch wherever he turned. In a huge anteroom the arriving guests were shedding their hot togas for the better enjoyment of the evening. Sloe- eyed Egyptian damsels in a tricky and revealing livery attended to the checking. On the counter before them was the inevitable tray sprinkled with high denomination coins—tip bait. Barry grinned. He began to feel at home. Cassidy, whatever his faults, must be some boy.

In the foyer he came upon another interesting sight. Along one wall ran a row of cashier's cages wherein men armed with jeweler's loups, acids and balances, were weighing and appraising the vast miscellany of coins being offered them. They paid off in chips, the only medium of exchange, apparently, accepted within the walls of Fortuna's Palace. That, of course, had long been standard practice in the casinos of the world, but Barry saw a deeper significance, and his admiration for his opponent's shrewdness grew. He was insinuating Anachron chips into the Roman world as its currency!

For the coinage of the day was anything but reliable. Administrations had a way, when the fiscal going got rough, of balancing budgets by debasing their coins. What the aureus of one issue might contain in the way of gold was not at all what the next might have. Moreover, coins could be counterfeited, whereas a twentieth-century plastic product could not possibly be. So there it was—a uniform, unbreakable, beautiful, and unforgeable medium of circulation. And the beauty of it—from Cassidy's point of view—was that it could only be had through him. The fact that they could buy food and drink and places at games of chance where issued gave them limited value. But Barry had already seen that the far-flung Hermetic communication system was also accepting them gratefully. How many other rackets did Cassidy operate where the new coinage was good? And how could he lose? He bought the chips wholesale at five trade dollars the thousand; he sold them for whatever he said they were worth.

Barry wandered on past the bar, past the entrance to a sumptuous dining hall where groups were banqueting, and on through several game rooms. There was chuck-a-luck and craps, faro, poker and stud tables. Barry observed that liveried members of the house staff were most attentive to the latter, never failing to pinch off the exact amount of kitty fodder whenever it was due. He saw also that the well-patronized roulette wheels had four green zeros, and marveled at the unanalytical Latin mind. Nor did he overlook the gorillas strategically located amongst the throng, off-duty gladiators probably, ready and willing to slap down any overexuberant guest. And then a flunky plucked at a fold of his toga. The senator, he said, was awaiting his guest in his private dining room.

The dining room was at the end of a long marble corridor which was lined with soldiers of the Praetorian Guard resplendent in chromium-plated armor of Anachron's best design. A husky centurion looked Barry over curiously, but made no effort to block his passage. So, thought, Barry, Mr. Cassidy goes in for bodyguards! And then he was ushered into the dining room—one equipped in true Roman style, where Cassidy and two other guests reclined on couches while they toyed with their food.

"Hi, fella," greeted Cassidy, not bothering to get up, but waving to a vacant couch. "Welcome to our city. It's quite a place when you know the ropes. It's wide open, and I mean wide—all the way across."

Pat Cassidy in the flesh came as quite a shock. Barry had expected to meet a tall, lanky Irish lad of about his own age and who wore a rascally twinkle in his eye. The man before him may have answered to that description once, but no longer. He was disgracefully fat, and bald on top. His eyes were pale blue and goggly, with heavy bags beneath. His voice was hardly better than a croak, and he accompanied his opening remarks with a sordid wink and a knowing leer. Barry's growing admiration for the ingenuity of what rackets he had seen was suddenly tempered by disgust. The two boon companions were not of a type to reassure, either. Both were dissipated and foppish-looking, and one, whom Cassidy addressed as Quint, had a lurking air of cruelty about him that was distinctly unpleasant.

"Meet my pals, Quintus and Gaius," said Cassidy, as Barry arranged himself on the divan. "Gay is the high muckamuck of the telegraph company—or high priest of the Atlantian Hermes to the rabble. Quint manages the insurance company and runs my slave ranch for me. Clever fellow. Make friends with him and he'll give you ideas where you can pick up some pin money of your own. You gotta have a side line, you know, to make any real dough working for that lousy Anachron outfit. By the way, how's old Kilmer doing? Still raving?"

"Oh, he'll be all right when exports pick up again," said Barry, with what diplomacy he could muster. "He was pretty sore after your starting up such a good wheat and flour business that the bottom dropped out of it all of a sudden. He says the Romans never did have enough wheat, and he wants to know how come?"

Cassidy chuckled and nudged Quint.

"Little family matter," he croaked. "My wife's uncle happens to be Procurator of Egypt and holder of the grain monopoly. Naturally he didn't like the competition. So when Commodus put a heavy duty on future grain—"

"I thought you and the emperor were buddies," said Barry.

"So we are," shrugged Cassidy, "but it's give and take, you know. I let him have his way about the wheat and he lets me have my way about some other things. It pays."

In the next two hours Barry found out how well it paid. By piecing together the scraps of conversation he was able to guess at the workings of several of Cassidy's major rackets. Gaius, for example, was also the chief priest of the Atlantian Temple of the Winds, close by which was an ancient cave known as the Grotto of Boreas. Concealed within it was a Diesel-driven ice plant served only by Gay's trusted slaves. Daily a caravan of wagons came and took away the blocks of ice produced overnight—ice which brought a fine price at the many public baths where the cool rooms could be made really cool. The ice was also much in demand at banquets, and had even been used at the palace in novel forms of torture.

Barry had already guessed that enormous revenues were derived from peddling the services of the god Hermes, but he had not guessed all. Hermes, being a god, did not necessarily serve all comers, however large their offerings. Quint, in the role of the god's messenger, systematically censored the messages handled between various parts of the empire. Therefore he and the rest of the Cassidy gang knew weeks in advance of military successes or reverses in the far provinces, of the success or failure of important money crops, of the number and worth of the emeralds and pearls brought up the Red Sea every year from India. Therefore they knew how to buy and sell in Rome to advantage. They had gone so far as to establish an embryo stock exchange where they dealt in futures to their immense profit.

Nor was that all. The order for the fire-fighting equipment that had so delighted Kilmer when it first came up had been for another purpose than he had imagined. Knowing the ever-present dread of fire that haunted Rome, the Home Office made the mistake of assuming that the initial order was merely for demonstration purposes and that other orders for larger amounts would shortly follow. That they did not, Barry now learned, was due to the organization of the Phoenix Assurance Society. The PAS paid no loss indemnities, but for the high premiums it collected it did undertake to dispatch its well-trained gangs of slave firemen to put out the fire on the premises of a policy holder. Since they had pumpers and hose and ladder wagons, and also maintained a fire watch, they were usually successful. On the other hand, the buildings of nonsubscribers were left to burn. Enrollments were slow in the beginning, but the judicious use of arson remedied that defect. Commodus himself, Barry learned, was one of the stockholders. Cassidy and company, having a strangle hold on the fire-prevention business, wanted no more fire equipment.

"Don't you see, fella," asked Cassidy, with his usual leering wink, "how much better it is this way? We get more in premiums every month than I would get in commissions on a hundred fire engines. Why be a sap? But you ain't heard nothing yet. You know all that afeverin I bought? I'd have been an awful sucker if I had sold that stuff over the counter at so much an ounce. It cures malaria in one or two doses, and the malaria stays cured. Right away I saw the right set-up. There's no gratitude to be had from a man for curing him of anything, but plenty of profit if you go about it using the old bean."

As Barry listened his disgust grew. He learned about the slave ranch. Every week hundreds of emaciated and anaemic slaves were herded into the place. Those broken-down slaves had been bought in the open market by underlings of Quintus for a paltry few hundred sesterces each, since such invalid slaves were not worth their keep. At the ranch they were rehabilitated. A few shots of afeverin, a build-up diet rich in vitamins, and abundant rest did the rest. On the face of it it looked like a humanitarian proposition. Actually it was anything but. For as soon as the slaves were well and strong again and had been taught a trade, they were displayed again on the market for sale. That time, after only a few months' overhaul, they brought prices up in the thousands.

"Not bad, eh?" said Cassidy. Then he asked what ideas Barry had as to setting himself up in a noncompeting racket. It was understood, of course, that Cassidy and perhaps Commodus would be cut in on anything new that was launched.

"Can't think of one at the moment," said Barry. It looked as if Pat Cassidy and his Rome were going to be hard nuts to crack. He wanted to feel his way.

At the end of three months Barry's distaste for Rome and everything about it amounted to almost a phobia. He had seen the profligate rich throw money around in his own age, and he had also seen distress and poverty. But the orgies of the Roman wealthy and the sufferings of the poor outdid anything he knew. Nor was there in the annals of a grasping capitalism anything to equal the unconscionable rapacity of the Roman rich. Barry concluded that he would not live in Rome if they gave him the place and allowed him fifty weeks' vacation a year. All of which availed him nothing, for he committed the initial error of doing well from the start. His protests to Kilmer brought one unvarying response:

"Stick to it, you're doing fine." And then Kilmer would take what scant joy there was out of that unrelished compliment by asking when he was going to shove Cassidy off the perch and send him up home.

Barry's original intentions had been good. He started off with the idea of pepping up business as speedily as possible for Kilmer's sake. At the same time he wanted to study local conditions and find out just how firm Cassidy's grip was on the imperial machine. The answer to the latter was that Cassidy was all-powerful. Likewise, invulnerable. He was an artist at back- slapping and soft-soaping; his instinct as to when to flatter, when to browbeat, and when to bribe was infallible. He cared not a hoot how rich the other fellow got so long as he got his. It made him popular in Rome, where impoverished aristocrats fawned on him, and where the greedy wastrels of the court were ready to make any concession he demanded.

Barry saw that a frontal attack was out of the question. So he set about to develop the legitimate markets that hitherto had lacked appeal to the scheming Cassidy. He pawed through the many cases of sample materials that until then stood untouched in the Ostia warehouse. He induced Cassidy to go down there with him one day and look them over, sketching out his plans as he spoke of the possibilities in this and that. Cassidy surprised him by agreeing vigorously with all he said, and when Barry went to make out the quantity requisitions Cassidy—in his capacity of manager of the Roman branch—signed them without a murmur. On the contrary, there was a curious crooked smile on his porcine face as he scribbled his initials, and Barry thought he caught a glint of cheap cunning in his piggish eyes. But Barry filed the orders. It was a start.

The first to arrive were the ships laden with asphalt, salamanders, rollers and spreading tools.

Barry had noticed on his trips between the capital and the port that the roads, while excellent, were primarily military roads. They were well built and well drained, but they were surfaced with slabs of hewn stone. Whenever the clumsy vehicles of the day hit a joint it got a jolt. Barry saw at once that all that was needed to make them ideal highways was a thin topping of asphalt. And once that was applied the way was open for the introduction of lightweight vehicles such as wire-wheeled, ball- earing, rubber-tired wagons for country use, and rickshas for the narrow streets of the city proper.

Cassidy astonished him by appearing in person on the dock while the schooners were being discharged. He waddled into the warehouse office, accompanied as always by his guards, and handed Barry an order for one million sesterces. It was for the paving material and tools.

"I thought you said the government would pay twice this much," said Barry, turning the order over in his hands. A million sesterces scarcely covered cost, freight and overhead. "Or three times," amended Barry.

"They will. To me," said Cassidy, blandly. "I'm buying it for my construction company; it has the contract to resurface the first two hundred miles."

"But—"

"Listen, buddy, get wise to yourself. Kilmer will be happy—the stuff is moving, ain't it, and the company breaking better than even? Why should you and I lean over backward and let them skim the cream. That's for us—me, and maybe you."

"But—"

"I figured we might need protection," Cassidy croaked on, "what with the chiselers here and in case Kilmer tries to get tough again. So I had a talk with the emperor and everything's fixed. You think patents are a good thing, don't you? Well, now we've got 'em. A pal of mine named Flavius has been made Quaestor of Patents. I took up our sample line and filed on 'em. That, and a little grease to Flav did the trick. From now on I've got the sole and exclusive right to use or sell any of the things we bring in, see? I'm your customer, see?"

Barry saw. He saw what Cassidy wanted him to see. He saw more than that. He saw red. But he kept his mouth shut. His opportunity had not come; it was not even in sight. So he carried on.

His next lesson in metropolitan politics came when the rickshas were delivered. Cassidy had a double strangle hold on those, for he not only controlled their sale as patentee, but their use. Barry had completely overlooked an old Roman ordinance dating from Julius Caesar's time forbidding the use of the streets by any wheeled vehicle between the hours of dawn and dusk. Cassidy swore that he was helpless to get the edict repealed, but he did succeed in having it modified. As amended the ukase read: "Wheeled litters may be operated by approved persons." The only approved "person" turned out to be the Capitol Rapid Transit Co., whose ownership Barry had no trouble guessing.

He struggled on. He established a big department store just off the Via Sacra and stocked it well. He put in a line of kerosene lamps with glass chimneys and braided cotton wicks, and sold the oil to keep them lit. They were instantly popular, replacing as they did the smelly and nonluminous olive-oil burners theretofore used. He introduced sugar which was at once bought in vast quantities by the vintners to improve their heavier wines. No longer were the ancients restricted to the choice between vinegary clarets or the sickish honey-sweetened variety. Hardware, comprising all manner of tools, swords and daggers, iron pipe, nails and so on, went well. Cosmetics, especially perfumes, found an insatiable demand. Romans had always used the latter without stint, but since its base was olive oil and not alcohol, it left them greasy and all too often with an overriding rancid odor. In exchange for those importations Barry sent back home shiploads of marble statuary, Greek pottery, and many casks of the better wines and olive oils.

Cassidy kept his hands off the department store, but for a price. Barry had to set him up in one more monopoly—the press. Job presses, type, ink, paper and other accessories were brought down and the Daily Stentor was duly launched upon an insatiable Roman reading public. Cassidy erected billboards and soon the streets of the great city were gay with lurid lithographs announcing the coming gladiatorial contests or races at the circus. Barry watched the growth of the printing business with some disgust, then turned back to his job of building up Anachron's business.

He established a chain of soda fountains, imported cigarettes, bananas, chocolate, tomatoes, and many other novelties. Then he undertook to try his hand at tempering the brutality of the Romans. He was not forgetful of the company motto—"Merchants, not Missionaries"—but he had to live in Rome, and the all too frequent sound of cheering welling up from the stands about the blood pit of the Coliseum offended every fiber of his being. Barry was not a tender-minded man. He had participated in plenty of carnage, but that had been in time of war and had at least the merit of necessity. Not so the senseless butchery that was committed under the name of "games." The feeding of huddled groups of meek martyrs to ravenous beasts, or the fiendish hacking away of one another's limbs by gladiators for no other purpose than to amuse a sadistic and jaded mob was to Barry's mind a crime against nature. So, he thought, the next step is to begin the education of these people. They can learn that games of strength and skill do not necessarily have to be played in a wallow of gore.

"Why not?" remarked Cassidy, carelessly, when Barry broached the matter of introducing football. "It's a good, rough game. The customers ought to lap it up. I'll speak to Quint about it. He has a string of reconditioned gladiators I sold him, and no doubt he'll make 'em into a team and back 'em against somebody else's."

It was soon arranged. Barry sent a hurry call to home for balls and uniforms and then spent his spare time for several weeks in coaching the new teams. One day the Master of Games was there, and after watching the drills and scrimmages for a while, expressed great satisfaction with the new idea.

"We've got it," he assured Barry. "Just leave the rest to us."

In the period that intervened before the premiere of the novel game Barry swelled with justifiable pride whenever he saw the announcements of it on Cassidy's many billboards. He even swallowed his feelings when he received the imperial command to be present as the guest of honor. That meant sitting in the imperial box beside the infamous Commodus, which also meant that he would have to go early and see the whole show. It was the preliminary massacres he dreaded to witness, for he had no stomach for pointless slaughter designed only to whip the crowd to the proper level of frenzy for the introduction of the main event. But he decided to make the personal sacrifice of enduring them for the sake of the ultimate greater gain.

The preliminaries were a greater ordeal than he had bargained for, and he found his revulsion for things Roman climbing to new peaks. His disgust now included the women as well, for they appeared to be even more savagely bloodthirsty than the men. The representatives of their sex he loathed most were the so-called Vestal virgins. He wondered whether their thumbs were so jointed that they could only be turned downward. But the most odious feature of the early games was furnished by Barry's own host—the vain and boastful Commodus. From time to time he rose in his box to display his consummate skill as an archer. His arrow infallibly found the throat or heart of whatever wild beast or luckless gladiator he picked as a target. It was admirable shooting and the unfortunates were doomed to die in any event, but it was the whimsical way in which the emperor chose his victims that irked Barry most. Of all the guests in the box he alone refrained from murmuring the expected phrases of fulsome praise, a circumstance that did not go unnoticed by Commodus. But the emperor chose to restrain himself. A haughty but vindictive look was all he visited on Barry then, but Barry knew that from that moment he had a mortal enemy.

By the time the arena had been cleared of the corpses of the last of the earlier entertainers. Barry was already sick with suppressed rage and impotent pity. He could only grit his teeth and clench his hands to await the verdict of the crowd upon his own humane innovation. Trumpeters and heralds came in. The announcements were made, and Barry noted with some satisfaction that he was named as the introducer of the new "thrilling, stupendous, astounding spectacle brought from the far isles of Hesperides." Then he sat back a little more at ease. A build-up like that would help his game go over.

The gates were flung open, and the teams marched in. Barry sat up abruptly as if jabbed suddenly with a bayonet. He gasped. He stared and stared and gasped again. Had it not been for the announcement and the Master of Games marching in the lead carrying a single gilded football in his arms, Barry would never have guessed that the game he was about to see had any relation to football. He watched with horrified eyes as the sides were taken and the line-up made. There was no kickoff; the ball was simply awarded by the umpire after the quarterbacks tossed the dice. The only other football-ish feature was the goals—gilded baskets at opposite sides of the arena.

The teams consisted of about a hundred men on the side. Each fell in in two ranks, the first crouching, the second standing behind with naked swords in their hands. All wore heavy body armor, spiked steel helmets, gaffs at their heels, and daggers at their belts. A small cloud of retiarii—lithe and agile gladiators armed with nets and tridents—covered each end, evidently for the purpose of discouraging end runs. But it was the back formation that afforded the big thrill. Each quarterback—and judging from the delighted howls from the stands they must have been popular champions—rode a mighty war chariot whose wheels were fitted with murderous revolving scythes. The other backs, of whom there were about a dozen to the side, rode horses. They carried lances and battleaxes hung at their saddlebows.

There was a fanfare of trumpets, then a single prolonged bray. As its hoarse note died, the teams plunged into the fray. The quarterback with the ball—which he carried in a net slung over his shoulders—attempted an end run, the cavalry of his backfield preceding and flanking him by way of interference. Barry's hands gripped the stone rim of the box as he watched the horror of the scrimmage that followed. His senses reeled ... the crash of impact as the two lines met head-on ... the dozens of individual duels ... the raging juggernaut plunging around the left end ... the futile efforts of the linemen to break through the fringe of horsemen to complete their tackle by disemboweling a chariot horse. There followed the countercharge of the defending chariot... the hideous melee that followed when the two war buggies met head-on only to capsize into a welter of spinning wheels, kicking and screaming horses, slashing, stabbing and gouging men. Many died before the armored referees fought their way into the midst and declared the ball at rest. Barry hardly heard the next braying of the trumpet, or the clarion voice of the umpire calling out, "First down, forty paces made good. Time out for replacements."

Barry shuddered and closed his eyes. He already knew the routine of the scavenger squads with their mules and flesh hooks. He did not want to see any more. All he knew was that he had failed and failed miserably. The wild howling that rent the stands was proof of that. Rome was at its pinnacle of delight. They had just witnessed the opening gambit in what undoubtedly would prove the fiercest and goriest form of entertainment any had seen. They yelled and stamped and called for "Marcus Barrius, the great Atlantian gamester!" Commodus rose, acknowledged the applause—which he naturally took for himself, since he was the patron of the game—and then, as a sop to the cheering multitude, took the chaplet from his own curled locks and jammed it on Barry's head.

Barry stood stunned for a moment, paralyzed with the shame and horror of his situation. His and Commodus' eyes locked and there was in their mutual gaze all the venom of the basilisk, generated on the one part by sheer natural cruelty, on the other by outraged honor. Barry raised his hand very deliberately, snatched the accursed wreath from his head and stamped on it. He contemptuously turned his back on the emperor and stalked past the trembling other guests and out of the box. He expected to be seized at any moment, but no order was given to stop him. Just as he was almost clear of the place Commodus' voice drifted to him above the pandemonium that filled the tiered benches. It was shrill and taunting.

"We shall meet again, my dear, dear friend, in this very place. And soon!" And the voice died away in peals of merry, sardonic laughter.

Barry was in a dark and bitter mood. He had walked the empty streets unmolested, but after he reached his apartment he paced the floor for hours in agitated thought. The jig was up; that was clear. Now what to do? For now that he had publicly insulted Commodus his life was not worth a plugged nickel if he stayed in Rome. Barry knew that he had not only incurred the undying imperial enmity, but the scorn of the populace by showing his disgust at the shambles of the arena. Moreover Cassidy was aligned against him. The rupture with Commodus was not the only one of the day; earlier Barry and Cassidy had quarreled. Their break had come less than an hour before the game.

It was about an effort Barry made to ameliorate the ravages of the bubonic plague that was terrorizing the poorer districts of the city. It had raged spasmodically ever since being brought back from Asia by returning soldiers several years before, and the Romans in their ignorance were doing nothing whatever about it.

"It would help," suggested Barry, since Cassidy's co-operation was essential in view of his being the Pontifex Maximus of his system of synthetic Atlantian gods, "if you would dedicate one of your temples to your god of healing. . . Aesculapius, wasn't it?. . . and pass the word on to the people that he craves live rats as sacrificial offerings. Twenty rats a head would do it, I think, and you could promise them relief from the disease. The temple would have cages, and an oil-burning incinerator—"

"Are you crazy?" asked Cassidy. "What's the big idea? There's no market for rat carcasses that I know of. Why should I put aside a good piece of real estate, pay priests salaries and all of that to collect rats? I don't get it."

"We stop the plague," explained Barry patiently. "It's very simple. Bubonic plague is a rat's disease. Rats have fleas. When a sick rat dies his fleas have to hunt another home. If they can't find another rat, a human will do. Then the human gets sick and dies. If you kill the rats with the fleas still on 'em—zippo, no more plague."

Cassidy shook his head.

"Not practical. You've got something there, but you don't know how to handle it. When you put out good money you expect to get something back. Now here's the way we'll set the thing up—"

Barry listened in disgusted amazement as his piggish contemporary outlined the scheme. Barry was to order a stock of disinfectants. Cassidy would organize an exterminating company and put on an educational campaign on his billboards and in the paper. After that everything would be set. For a substantial fee the new company would clear a house of rats. That way it would pay.

"See?"

"No. I don't see." Barry did not bother to conceal his loathing. The heaviest toll taken by the plague was from the poorer districts, in the slums that nestled in the valleys between the hills, in the foul insulae where poor freedmen boarded. Not one there could raise the fee and it was rank nonsense to expect the grasping landlords to pay. Cassidy's plan might make him a little money, but could have no discernible effect on the plague. All Barry's pent-up hatred of the man boiled over, and for five minutes he told him what he thought of him. He pulled no punches and the blunt language he used was appropriate to his opinions. Barry had fought on five continents and the seven seas and he knew how to express himself.

"That washes you up," said Cassidy in cold fury toward the end. "No man can talk like that to Pat Cassidy and get away with it," and flung himself from the room.

Yes. Barry had good reason for the feeling that his days in Rome were numbered. He was up against a combination of ruthless power and unscrupulous wealth headed by two men he knew were out to get him. His choice was narrow. He could stay and take it, or he could cut and run. An SOS to Kilmer would bring the little shuttle for his getaway, but that was a course that Barry firmly rejected. He did not see how he could win in the coming fight, but he didn't like a quitter. He wouldn't go running to Kilmer admitting failure and with his work undone, for Kilmer had instructed him to unseat Cassidy and ship him home. Instead of that, he bad only intrenched the man more firmly than ever. Barry set his jaw. It was to be a hopeless fight, but he would not run from it.

Five minutes later he was in the editorial rooms of the Daily Stentor and at his crisp orders quailing subeditors scurried about killing the issue they were just about to put to bed. None dared oppose him, for they were slaves and thought him to be acting for their master. They knew the slightest disobedience might bring them under the lash.

"Scare head," ordered Barry. "Now take this."

For an hour he dictated. The trembling scribes gasped as they took down the treasonable and blasphemous words. They were between the devil and deep blue sea; the whipping post on the one hand, the chance of crucifixion on the other. For Barry had decided to go the whole hog.

He lit into Cassidy first, revealing the workings of his many rackets. He showed how any Roman could rid himself of malaria at the cost of a few small silver coins if afeverin were only on general sale. He told how the Hermetic telegraph system worked, of its exorbitant charges and the misuse made of the messages intrusted to it. He pointed out the iniquity of the fire protection racket and its excessive cost. He recited his vain efforts to have something done about the plague. Then he dealt with some of the minor rackets.

Cassidy had taught several of his slaves something of plastic surgery with the result that they carried on a shady side line. Freedmen or escaped slaves who had been branded on the forehead with the symbol for thief could go to Cassidy's and have the skins of their faces renewed with unblemished foreheads. He mentioned, too, the abuse of the supplies of Mercurochrome. That had been ordered for surgical use for the army, but instead was used to paint the faces of the palace harlots. Barry was not sure what had become of the dental chairs and forceps, drills and the rest, but it had been hinted that they were used for special guests in one of Commodus' torture chambers.

That led him to Commodus and his connection with the Cassidy outfit. Barry painted him as the playboy he was, excoriated him for his conceit and cruelty. He went out of his way to ridicule his habit of descending to the floor of the arena and fighting in person as a gladiator. Barry knew that was a shot that would go home, for it was the scandal of Rome. The old aristocrats had shivered when Nero sang to public audiences; now they had an emperor-gladiator—many steps lower than a mere buffoon.

At length Barry came to the finish. He spent the rest of the night seeing that the paper went out in the form he wanted. At dawn he retired to his apartment for what rest he could get. He knew it would not be long before the soldiers would be coming for him.

It was a grizzled old centurion that made the arrest. He brought a file of twenty soldiers with him and dragged Barry protesting through the streets. The destination was the palace. On the way they passed the statue that Commodus had recently erected in honor of himself in which he was depicted as the reincarnation of the demigod Hercules. Barry glanced at it and his lip curled.

There was no trial. There was only a harangue from Commodus. The essence of it was this:

"You have chosen to ridicule me as a fighter. Very well. Five days hence we will meet in the arena and see who is the better fighter. Choose any arms you please so long as there is no metal about you."

That was all. Barry was led back to his apartment. Soldiers were all over the place and he was under close arrest, but within his own rooms he was not interfered with. He sent off a long dispatch to Kilmer, bringing him up to date on happenings, making it clear that he was having to fight in self-defense. The company's rules as to mixing it up with peoples of other ages were adamant. If by any chance he should win, he did not want to have another battle with the boss over how he came to duel with an emperor.

The day set for the conflict Barry was hustled off to the coliseum early in the morning. They put him in a dark and filthy cell along with a dozen others selected to fall beneath Commodus' sword. All were going in the role of retiarius, since the only feasible weapon they were allowed was the net. Nothing else could possibly avail against the emperor's heavy body armor and helmet. But there was little hope among them. Commodus was most dextrous at evading the net; none had ever snared him. Nor did anyone wish really to try. No one knew for certain what the penalty for winning would be, but neither was he anxious to find out.

Barry was dressed simply in cotton shorts and singlet. He wore no helmet, carried no net or other recognizable weapon. But in a little sling there were three glass balls. He had chosen those from among the sample items as being probably of the most real service. He had had them sent down for demonstration, but his other duties had prevented him getting around to them before. Now, he thought grimly, we'll show them off.

They could hear little while waiting in the dungeons below the grandstand, but Barry knew from what he did hear when the games got under way. Later the guards came and took out his cellmates a few at a time. Not one came back. Barry surmised that his adversary was warming up on a few easy victims. And no doubt he was saving Barry to the last. Barry had not been able to find out just what effect his published broadside had had, but whatever its effect it must certainly have made him a marked man. Probably half a million people fought for places to see the bout of the day—Commodus versus his Atlantian detractor.

Then Barry was out in the arena. Tumultuous shouting filled the air and the seats were alive with color and movement. Commodus stood in the very center of the arena, while many spots of bloody sand attested to the exercises he had already completed. He waved a reddened sword and shouted a derisive epithet. But he waited cagily to see what Barry would do. Barry did nothing for a minute or so, then advanced slowly toward his adversary. So far his hands were empty. Within ten paces of Commodus he stopped and waited. Then Commodus gathered himself for the charge, brandished his weapon, and launched forward.

Barry had not been the star pitcher of his Commando unit's team for nothing. So quick that the eye could hardly follow, he snapped one of the glass balls out of the sling and hurled it straight at Commodus. It struck him squarely on the visor of his helmet. There was a puff of whitish vapor, and then Commodus was on his knees, blubbering and praying. His sword dropped to the sand and the buckler rolled away. But the gladiator emperor knelt and wept. Like a big wind, a monumental gasp went up from the tiered spectators. Commodus had yielded without a stroke being delivered! He was begging for mercy!

Barry waited a discreet few seconds, then strode forward and picked up the fallen sword. The gas bomb he used contained a new modification of the old tear gas. It not only brought tears by the usual reaction, but engendered the emotions that normally accompanied tears. It dissipated rapidly in the open, but those who breathed it were under the effects for hours. Barry knew that Commodus would continue to grovel and snuffle for some time. He disregarded the whimpering figure at his feet and looked to the box for the verdict. To his astonishment it was thumbs down! A great hush had fallen on the multitude, for the brown-clad mob in the upper seats were awed by the unprecedented disaster. But the knights and nobles in the boxes, not forgetting the pious Vestals, were clamoring for the victim's blood.

Something clicked within Barry. He had been calm until then; now he knew fury. What a people, to expect him to stab a man to death in cold blood! He stared up at their relentless faces. Each probably had his own excellent reason for wishing Commodus' death, but Barry did not intend to be the one to gratify them. On the contrary, he estimated the range carefully, then hurled his remaining two bombs—one into the imperial box, the other high up in the stands. He waited silently for their effect.

It was stupendous. In another instant the aristocrats were shedding tears, beseeching mercy upon themselves, Commodus, anybody and everybody that might be in need of it. The frigid Vestals melted. For once their thumbs went up as the salty water rolled down their cheeks. Even the soulless Cassidy, who had come to witness his assistant's murder, blubbered some. But it was in the stands where the unexpected happened. All hell broke loose. They went crazy. No Roman had ever seen compassion; no Roman could understand it. Yet there were among them some of the city's outstanding fight fans—men who loved their gore and knew good slaughter when they saw it—and these hard-boiled eggs were sniffling like whipped children, calling: "Don't hurt him, oh, don't hurt him, please, honorable Barrius." The inevitable succeeded. Riots broke out in every section. In two minutes a free-for-all was raging all over.

Barry cast one contemptuous look about, hurled the sword from him, and stalked disgustedly out of the arena. Two guards pounced on him at the gate and led him away to a cell, but he did not care overly. He had shot his wad and there was no more to do. But he was curious as to the outcome. He only hoped that he would learn about it before they finished him off, and also added the hope that the process of being finished off would not be too messy or take too long.

He knew the worst when they led him into the torture chamber. Most of the stuff hanging about were the same old chestnuts men have used for ages—whips, brands, pincers and the like, but the instrument of which they were most proud Barry recognized at once. It was a gleaming dental chair, and a grinning executioner was fitting a drill to its socket. A helper stood by to pedal the gadget. Rows of wicked-looking shiny forceps, hooks and crooked wires hung nearby.

"This won't hurt," soothed the fiend, as the attendants strapped Barry into the chair. "Not like knocking 'em out. It just takes longer."

Somebody stuck a wedge into Barry's mouth and the executioner closed up with his drill a-whirring. There was an interruption. The door burst open and a high official entered. It was a tribune of the Praetorian Guard.

"Hold everything," he said. "They want to examine this man before the senate. The honorable Patricius Cassidus says that he used an Atlantian gas and they want to know more about it. Make ready to take him there at once, and see that he has some of the magic gas with him."

Barry relaxed. Anything was welcome after what he had steeled himself for. But gas? There wasn't any more, and it would take him days to get some. At that, he couldn't see how it would help his cause to reduce the august senate to a state of weepy soddenness. Then his eye lit on a contraption in the corner. It was a little buggylike affair carrying a steel flask of oxygen and another of nitrous oxide. From the reading of the gauges it was clear that they had never been used, probably from ignorance. But as part of Anachron's dental equipment, there they were.

"This is more of the gas I used," said Barry, indicating the nitrous oxide container. "Have that brought along."

The session in the senate did not last a great while. Before he reached the hall Barry learned that in the pandemonium raging after he left the arena, a wrestler named Narcissus, who had some grievance against Commodus, had obeyed that section of the mob who were demanding that he be put to death. Narcissus at once performed the job by throttling him in his best professional manner. In consequence, by the time Barry was conducted into the chamber, the senators had other and more important things on their minds. They were whispering among themselves as to how they would line up behind this or that candidate for the emperorship. Cassidy was of course one of the outstanding candidates. It was of him and other contenders that they were thinking when Barry's guard brought him in. But they snapped out of their huddles when Barry was arraigned before the house.

"You are charged with using a noxious gas to defeat our emperor," said the president sternly. "We demand to know what that gas is."

"Here it is," said Barry blandly, cracking a valve. There was a hissing, and he leaned over and sniffed. He straightened up, smiling happily. "A lovely gas, really. What I took to the coliseum must have gone sour with the heat."

"Let me smell that," demanded Cassidy, stepping forward. Now Cassidy, while a versatile fellow, did not know the conventional marking for gas carboys, so he could not know until he took a whiff what sort of gas it was. Even then he didn't recognize it. But he did like it. It gave him a lift. He took another drag. Then he began to laugh and dance a little.

"Let me smell that," demanded Cassidy.

"Suwell, deelightful," he babbled, "have a sniff on me, fellows."

Curious senators crowded up, a wee bit doubtful, but wanting to know. But as each drew nearer, his doubt melted. He beamed, he giggled or burst into ribald song. Others capered, embracing anyone who came near. In a very few minutes it was a gay and happy party. All were drunk as lords. Cuckoo. Absolutely. And not the least of them was Barry. Indeed, in a moment the gas got the best of him and for a little while he passed out.

When he came to he found himself the center of a rollicking back-slapping crowd. He seemed to be popular. They liked him. But they were saying strange things to him. Were they kidding? For in their hilarious mood it was hard to judge. Yet he gathered that in their elation generated by the laughing gas they had dismissed any complaint against him. They had gone further. They had elected him to the vacant office of emperor.

"Ave, Caesar," they shouted, stamping up and down, "Hail, Barrius, Imperator Romanorum! Whee! Yippee!"

Barry was still a bit woozy himself, so he did not fully grasp what had been done to him. Then it began to dawn on him. He backed away from his enthusiastic admirers with growing concern on his face. Oh golly, golly, golly. He had played hell now! Rule G-45607! "Whoever accepts any public office... et cetera, et cetera... will be cut off." Ow!

"Barrius, Imperator, huh?" groaned Barry. "That sinks me."