RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Astounding Science Fiction, June 1941, with "Brimstone Bill"

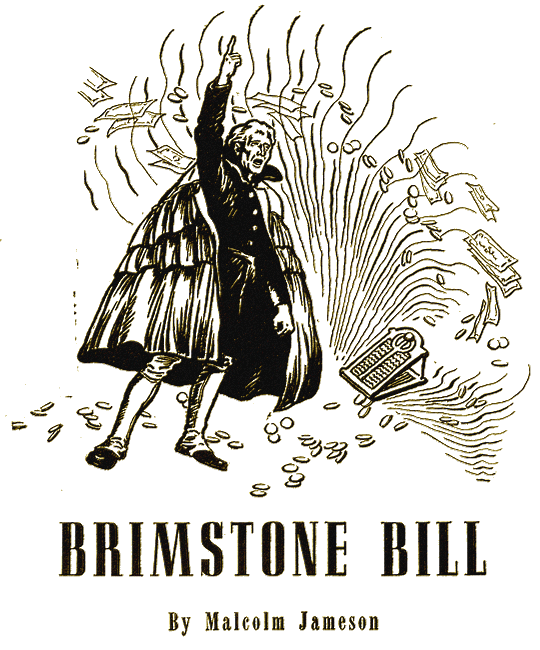

Bill was a crook, a hell-fire-damnation specialist in the art of collecting cash. A marvelous orator—with gadgets. But Commander Bullard had a good use for a bad actor!

THE prisoners were herded into the room and ranged against one of the bulkheads. Captain Bullard sat stiffly behind his desk regarding the group of ruffians with a gaze of steely appraisal. Lieutenant Benton and a pair of pistoled bluejackets were handling the prisoners, while Commander Moore stood at the back of Bullard's desk, looking on. Then Bullard gave a jerk of his head and the procession started. One by one they shuffled to the spot before his desk, clanking their heavy chains at each dragging step. And one by one the captain of the Pollux surveyed them, critically and coldly, comparing their appearance and their marks with the coded descriptions in the ethergram on his desk.

These were the survivors of the notorious Ziffler gang, captured on Oberon the month before, after the encounter on the lip of a little crater that the Polliwogs had already come to call the "Battle of the Mirrors." The first, of course, was Egon Ziffler himself, all his arrogance and bluster melted away long since. Then came Skul Drosno, his chief aid, and there followed ten other plug-uglies who had survived the holocaust of reflected fire. All were big hulking brutes of Callistans, ray-blackened, scarred and hairy. The last and thirteenth man was of a different type altogether. Bullard waited in silence until he had ranged himself before his desk.

"Paul Grogan," called Benton, checking the final name of the list.

"Hm-m-m," said Bullard, looking at the miserable specimen standing at a grotesque version of "attention" before him, and then glancing at the Bureau of Justice's ethergram summary of his pedigree. After that he studied the prisoner in detail. He was a queer fish indeed to have been caught in such a haul.

The self-styled Grogan was a wizened, under-fed little fellow and bore himself with an astonishing blend of cringing and swagger. The strangest thing about him was his head, which was oversize for his body. He had a fine forehead topped with a leonine mane of iron-gray hair, which after a cursory glance might have been called a noble head. But there was an occasional shifty flicker of the eyes and a twitching at the mouth that belied that judgment. Bullard referred to the Bureau's memo again.

"Grogan," it said, "probably Zander, alias Ardwell, alias Nordham, and many other names. Small-time crook and chiseler, card sharp, confidence man. Arrested often throughout Federation for petty embezzlement, but no convictions. Not known to have connection with Ziffler gang."

"Hm-m-m," said Bullard again. He had placed Grogan, et cetera, now in his memory. It had been a long time since the paths of the two had crossed, but Bullard never forgot things that happened to him. Nor did he see fit to recall it too distinctly to his prisoner, for he was not altogether proud of the recollection. But to check his own powers of retention, he asked:

"You operated on Venus at one time—as an itinerant preacher, if the record is correct—under the name of Brimstone Bill?"

"Why, yes, sir, now that you mention it," admitted Brimstone Bill, with a sheepish grin. "But, oh, sir, I quit that long ago. It didn't pay."

"Really?" remarked Bullard. That was not his recollection of it. He had visited Venus in those days as a Passed Midshipman. One night, in the outskirts of Erosburg, they had curiously followed a group of skymen into a lighted hall emblazoned with the sign, "Come, See and Hear BRIMSTONE BILL—Free Admittance." And they went, saw and heard. That bit of investigation had cost the youthful Bullard just a month's pay—all he had with him. For he had fallen under the spell of the fiery oratory of the little man with the big bushy head and flashing eyes, and after groveling before the rostrum and confessing himself a wicked boy, he had turned his pockets wrongside out to find some worthy contribution to further "the cause." Bullard winced whenever he thought of it.

"No, sir, it didn't pay," said the little man. "In money, yes. But not in other ways."

"The police, eh?"

"Oh, not at all, sir," protested Brimstone Bill. "Everything I ever did was strictly legal. It was the suckers ... uh, the congregation, that is. They got wise to me. A smart-Aleck scientist from the gormel mills showed me up one night—"

He lifted his manacled hands and turned them so the palms showed outward. Deep in each palm was a bright-red, star-shaped scar.

"They crucified me. When the police cut me down the next day, I swore I'd never preach again. And I won't, so help me."

"You are right about that," said Bullard grimly, satisfied that his memory was as good as he thought it was. "This last time you have stretched your idea of what's legal beyond its elastic limit. The gang you were caught with is on its way to execution."

Brimstone Bill emitted a howl and fell to his knees, whining and pleading.

"Save that for your trial," said Bullard harshly. "Take 'em away, Benton."

AFTER they had all gone, Bullard sat back and relaxed. He promptly dismissed

Ziffler and his mob from his mind. The Oberon incident was now a closed book.

It was one more entry in the glorious log of the Pollux. It was the

future—what was to happen next—that mattered.

The Pollux had stood guard over the ruined fortress of Caliban until the relief ships arrived. Now she was homeward bound. At Lunar Base a richly deserved and long-postponed rest awaited her and her men. And there was not a man on board but would have a wife or sweetheart waiting for him at the receiving dock. Leave and liberty were ahead, and since it was impossible to spend money in the ship's canteen, every member of the crew had a year's or more accrued pay on the books. Moreover there would be bonuses and prize money for the destruction of the Ziffler gang. Never in the history of the service had a ship looked forward to such a satisfactory homecoming, for everyone at her arrival would be gayly waving bright handkerchiefs, laughing and smiling. Her chill mortuary chamber down below was empty, as were the neat rows of bunks in the sick bay. The Pollux had achieved her triumph without casualties.

It was on that happy day of making port that Bullard was idly dreaming when the sharp double rap on the door informed him that Moore was back. And the executive officer would hardly have come back so soon unless something important had turned up. So when Bullard jerked himself upright again and saw the pair of yellow flimsies in Moore's hand, his heart sank at once. Orders. Orders and always more orders! Would they never let the ship rest?

"Now what?" asked Bullard, warily.

"The Bureau of Justice," said Moore, laying down the first signal, "has just ordered the immediate payment to all hands of the Ziffler bonus. It runs into handsome figures."

Bullard grunted, ignoring the message. Of course. The men would get a bonus and a handsome one. But why at this particular moment? He knew that Moore was holding back the bad news.

"Go on," growled Bullard, "let's have it!"

Moore shuffled his feet unhappily, expecting an outburst of rage. Then, without a word he handed Bullard the second message. It read:

Pollux will stop at Juno Skydocks en route Luna to have hull scraped. Pay crew and grant fullest liberty while there. Implicit compliance with this order expected.

Grand Admiral.

Bullard glared at the thing, then crushed it to a tight ball in his fist and hurled it from him. He sat for a moment cursing softly under his breath during which the red haze of rage almost blinded him. He would have preferred anything to that order—to turn about and go out of the orbit of Neptune for another battle, if there had been need for It, would have been preferable. But this!

He kicked his chair backward and began pacing the room like a caged tiger. It was such a lousy, stinking trick to do—and to him and his Pollux of all people! To begin with, the ship had no sky-barnacles on her hull, as the pestiferous little ferrous- consuming interplanetary spores were called on account of the blisters they raised on the hull. And if she had, Juno was no place to get rid of them. Its skydock was a tenth-rate service station fit only for tugs and mine layers. The twenty men employed there could not possibly be expected to go over the hull under a month, and the regulations forbade the ship's crew working on the hull while in a planetary dockyard. The dockyard workers' guilds had seen to that. Moreover, Juno was not even on the way to Luna, but far beyond, since from where the Pollux was at the moment, the Earth lay between her and the Sun, while Juno was in opposition. It was damnable!

Bullard growled in midstride and kicked viciously at an electrician's testing case that stood in his path. That wasn't all—not by a damsite! Juno was one of the vilest dumps inside the Federation. It was an ore-gathering and provisioning point for the asteroid prospectors and consequently was populated by as vicious a mob of beachcombers and their ilk as could be found in the System. Juno literally festered with gin mills, gambling hells and dives of every description. No decent man could stand it there for three days. He either left or took to drink. And, what with what was sold to drink on Juno, that led to all the rest—ending usually in drugs or worse. It was in that hell hole that he had been ordered to set down his fine ship for thirty days. When he thought of his fine boys and the eager women impatiently awaiting their homecoming, he boiled.

"Shall I protest the order, sir?" asked Moore, hopefully.

"Certainly not," snapped Bullard, halting abruptly and facing him. "I never protest orders. I carry 'em out. Even if the skies fall. I'll carry this one out, too, damn 'em. But I'll make the fellow who dictated it—"

He suddenly checked himself. He had been about to add, "regret he ever had," when he remembered in a flash that Moore's family was in some way connected with the Fennings. Only Senator Fenning could have inspired the change of plans. The grand admiral had issued the order and signed it, of course, but he had inserted the clue as to why in its own last redundant sentence. "Implicit compliance is expected," indeed! No admiral would be guilty of such a tacit admission that perhaps not all orders need be strictly complied with. That sentence meant, as plainly as if the crude words themselves had been employed, this:

"Bullard, old boy, we know this looks goofy and all wrong to you, but we're stuck. You've been chosen as the sacrificial goat this year, so be a good sport and take it. None of your tricks, old fellow. We know you can dope out a way to annul any fool order, but don't let us down on this one."

The line of Dullard's mouth tightened. He sat down quietly in his chair and said to the expectant Moore as matter-of-factly as if he had been arranging a routine matter:

"Have the course changed for Juno, and inform the admiral that he can count on his orders being carried out to the letter."

Commander Moore may have been surprised at Bullard's tame surrender, but, after all, one was more helpless sometimes in dealing with one's own admiral than with the most ruthless and resourceful enemy. He merely said, "Aye, aye, sir," and left the room.

TWO weeks rolled by, and then another. They were well within the orbit of

Jupiter now, and indeed the hither asteroids. Hungry eyes now and then looked

at the pale-blue tiny disk with its silvery dot companion as it showed on the

low-power visifield and thought of home. Home was so near and yet so far. For

the ship was veering off to the left, to pass close inside Mars and then to

cut through beyond the Sun and far away again to where the miserable little

rock of Juno rolled along with its nondescript population.

During those days the usual feverish activity of the ship died down until it became the dullest sort of routine. Men of all ratings were thinking, "What's the use?" Moore and Benton were everywhere, trying to explain away the unexplainable, but the men did not react very well. Many were beginning to wonder whether the service was what it was cracked up to be, and not a few were planning a big bust the very first night they hit the beach on Juno. It was not what they had planned, but it seemed to be what was available. Only Bullard and Lieutenant MacKay kept apart and appeared to take little interest in what was to happen next.

Alan MacKay was a newcomer to the service, and his specialty was languages. So he had filled in what time he had to spare from the routine duties by frequenting the prison spaces and chatting with the Callistans in the brig. He had managed to compile an extraordinary amount of information relating to the recent war as seen from behind the scenes on the other side, and he was sure it was going to be of value to the Department. Moreover, he had gleaned additional data on the foray to Oberon. All of which would make the prosecutor's job more thorough when the day of the trial came. As for Bullard, he kept to his cabin, pacing the deck for hours at a stretch and wrestling with his newest problem.

His thoughts were leaping endlessly in a circuit from one item to the next and on and on until he came back to the point of departure and began all over again. There was the ship, the crew, and the devoted women waiting for the return of the crew, and the fat entries in the paymaster's books that meant so much to them both. And there was the squalid town of Herapolis with its waiting, hungry harpies with a thousand proven schemes for getting at that money for themselves; and there was the cunning and avaricious overlord of the asteroids, their landlord and creditor, who would in the end transfer the funds to his own account. That man also sat in the upper chamber of the Federation Grand Council and was a power in Interplanetary politics. His name was Fenning—Senator Fenning—and he dominated the committee that dealt out appropriations to the Patrol Force. And from that point Bullard's mind would jump to the Tellurian calendar and he would recall that it was now March on Earth, and therefore just about the time that the annual budget was in preparation. Which in turn would lead him back to the General Service Board, which dealt on the one hand with the Force as a master, but with the Grand Council as perennial supplicant for funds on the other. Which naturally took him to the necessities of the grand admiral and the needs of the Service as a whole. Which brought him back to the Pollux's orders and started the vicious circle all over again.

For Bullard was cynical and wise enough in the ways of the world to have recognized at the outset that the ship's proposed stay at Juno yard was neither more nor less than a concealed bribe to the honorable senator. Perhaps it had been a bad season in the asteroid mines and his debtors had gotten behind. If so, they would need a needling of good, honest cash to square accounts. Perhaps it was merely Fenning's insatiable lust for ever more money, or maybe he only insisted on the maneuver to demonstrate his authority. Or perhaps, even, having bulldozed the Patrol Force into erecting a small and inadequate skydock where either an effective one or none at all was needed, he felt he must have some use made of it to justify his prior action. Whatever Fenning's motives really were, they were ignoble. No exigency of the service required the Pollux to visit Juno now—or ever. And to Bullard's mind, no exigency of politics or personal ambition could condone what was about to be done to the Pollux's crew.

It was the ethical content of the problem that bothered Bullard. Practically it was merely annoying. With himself on board, his veteran officers and a not inconsiderable nucleus of tried and true men who had been in the ship for years, she could not go altogether to hell no matter how long they had to stay on Juno. He knew he could count on many—perhaps half—going ashore only occasionally; the other half could be dealt with sternly should they exceed all reasonable bounds for shore behavior after a hard and grueling cruise. But in both halves he would have to deal with discontent. The decent, far-sighted, understanding men already resented the interference with their plans, since there was no sufficiently plausible reason given for it. They would accept it, as men have from the beginning of time, but not gracefully or without grumbling. Then the riotous element would feel, if unduly harsh disciplinary measures were applied, that, somehow, they had been let down. Wasn't the very fact they had been sent to Juno for liberty and paid off with it an invitation to shoot the works?

There were other courses of action open to him, Captain Bullard knew. The easiest was inaction. Let the men have their fling. Given a few months in space again, he could undo all the damage. All? That was it. Nothing could undo the disappointment of the women waiting at Earth and Luna—nor the demoralization of the men at not getting there, for that matter. Nor could the money coaxed or stolen from them by the Junoesque creatures of Fenning ever be recovered. Moreover, the one thing Bullard did not like was inaction. If he was already half mutinous himself, what of the men? No. He would do something about it.

Well, he could simply proceed to Luna, take the blame, and perhaps be dismissed. He could give the story to the magnavox in the hope that by discrediting Senator Fenning and the System, his sacrifice might be worth the making. But would it? Would the magnavox dare put such a story on the ether? And wouldn't that be letting the admirals down? For they knew his dilemma quite as well as he did. They had chosen, chosen for the good of the Service. The System could not be broken, or it would have been long ago. It was the Pollux's turn to contribute the oil that greased the machine.

Bollard sighed. Juno was less than a week away now, and he saw no way out. Time after time in his gloom he was almost ready to admit he was beaten. But the instincts and training of a lifetime kept him from the actual confession. There must be some way of beating Fenning! It must be a way, of course, which would cast no reflection on the grand admiral. Or the ship. Or the crew. And, to be really successful, no ineradicable discredit upon himself. Bullard got up, rumpled his hair, and resumed his tigerish pacing.

IT was Lieutenant MacKay who interrupted his stormy thoughts. MacKay had

something to say about the prisoners. He had just about finished pumping them

dry and was prepared to draw up the report. There were several

recommendations he had to make, but he wanted his captain's opinion and

approval first.

"It's about that fellow Zander—the Earthman, you know—" he began.

"Oh, Brimstone Bill?" grinned Bullard. He was rather glad MacKay had broken in on him. The sense of futility he had been suffering lately had begun to ingrow and make him bitter.

"Yes, sir. He's a highly undesirable citizen, of course, but I'm beginning to feel a little sorry for him. The old scalawag hadn't anything to do with the Caliban massacre. He just happened to be there when Ziffler came, and escaped being killed only by luck. He was dealer in a rango game when they landed, and his boss had a couple of Callistan bouncers. Ziffler gave 'em the chance of joining up with him, which they did and took Brimstone along with 'em, saying he was O.K. Brimstone went along because it was that or else. He had no part in anything."

"I see," said Bullard, and thought a moment. "But I haven't anything to do with it. What happens hereafter is up to the court. You should submit your report to them."

After MacKay left, Bullard's thoughts turned upon his first encounter with the little charlatan many years before on Venus. Somehow, the fellow had had a profound effect on him at the time. So much so, in fact, that it came as something of a shock the day of his preliminary examination to find that the man had been a fake all along. Bullard had been tempted to think him a good man who had eventually gone wrong. Now he knew better. But as he continued his train of reminiscence, something suddenly clicked inside his head.

He sat bolt upright, and a gleam of hope began to dawn in his eyes. Brimstone Bill had a peculiar talent which might come in very handy in the trying weeks ahead. Could he use it with safety to himself? That had to be considered, for dealing with a professional crook had risks. Yet, according to Brimstone's own admission, it had been a gormel engineer that had shown him up, and Bullard figured that if a biophysics engineer could match wits with the grizzled trickster and win, he could. Perhaps—

But there was no perhaps about it. Bullard's fingers were already reaching for his call button, and a moment later Benton stood before him.

"Go down to the brig," directed the captain, "and bring that man Zander up here. Take his irons off first as I do not like to talk to men bound like animals. The fellow is a cheap crook, but he is harmless physically."

While he waited for Benton's return, Bullard explored the plan he had already roughly outlined in his mind. By pitting Brimstone Bill against Fenning he hoped to foil the greater scoundrel. But would he fall between two stools in the doing of it? He must also pit himself against the swindler, or else he would simply have enabled one crook to outsmart another without profit other than the gratification of spite. He had also to think of the other possible costs. The grand admiral must have no cause for complaint that there had been any evasion of his orders. Likewise Fenning must have no grievance that he dared utter out loud. There remained the item of the reputation of the Pollux and its men.

He puckered his brow for a time over that one. Then he relaxed. There were reputations and reputations, and extremes both ways. Some regarded one extreme with great favor, others preferred the other. Bullard liked neither, but for practical reasons preferred to embrace one for a time rather than its alternate. He would chance a little ridicule. After all, people might smile behind their hands at what a Polliwog might do, but no one ever curled a lip in the face of one and afterward had his face look the same. Pollux men had quite a margin of reputation, when it came to that, so he dismissed the matter from his mind. From then on he sat and grinned or frowned as this or that detail of his proposed course of action began to pop out in anticipation.

WHEN Brimstone Bill was brought in, there was no hint in Bullard's bearing

that he had softened his attitude toward the prisoner one whit. He stared at

him with cold, unsmiling sternness. "Zander," he said, drilling him with his

eyes, "you are in a bad jam. Do you want to die along with those other

gorillas?"

"Oh, no, sir," whined Brimstone, "I'll do anything.... I'll spill all I know.... I'd—"

Bullard shut him off with an abrupt wave of the hand.

"As the arresting officer I am in a position to do you a great deal of good or harm. If you will play ball with me, I can guarantee you a commutation. Maybe more—much more." He uttered the last words slowly as if in some doubt as to how much more. "Will you do it?"

"Oh, sir," cried Brimstone in an ecstasy of relief, for it was plain to see he had suffered during his languishment in the brig, "I'll do anything you say—"

"On my terms?" Bullard was hard as a rock.

"On any terms—Oh, yes, sir ... just tell me—"

"Benton! Kindly leave us now while I talk with this man. Stay close to the call signal."

Bullard never took his eyes off the receding back of his lieutenant until the door clicked to behind it. Then he dropped his hard-boiled manner like a mask.

"Sit down, Brimstone Bill, and relax. I'm more friendly to you than you think." He waved to a chair and Brimstone sat down, looking a little frightened and uncertain. Then, proceeding on the assumption that a crook would understand an ulterior motive where he would distrust an honest one, Bullard dropped his voice to a low conversational—or rather conspiratorial—tone, and said:

"Everybody needs money. You do. And—well, a captain of a cruiser like this has obligations that the admiralty doesn't think about. I could use money, too. You are a clever moneymaker and can make it in ways I can't. I'm going to let you out of the jug and put you in the way of making some."

Brimstone Bill was keenly listening now and the glint of greed brightened his foxy eyes. This man in uniform was talking his language; he was a fellow like himself—no foolishness about him. Brimstone furtively licked his lips. He had had partners before, too, and that usually worked out pretty well, also. He might make a pretty good bargain yet.

"We are on our way to Juno where we will stop awhile. I am going to let you go ashore there and do your stuff. You'll be given my protection, you can keep the money here in my safe, and you can sleep here nights. You had a pretty smooth racket there on Venus, as I remember it. If you work it here, we'll clean up. After we leave, we'll split the net take fifty-fifty. That'll give you money enough to beat the charges against you and leave you a stake. All I want you to do is preach the way you did on Venus."

While Bullard was talking, Brimstone grew brighter and brighter. It was beginning to look as if the world was his oyster. But at the last sentence he wilted.

"I can't do that," he wailed. "I'm afraid. And—"

"There are no gormel mills on Juno," Bullard reminded him, "only roughneck asteroid miners, gamblers and chiselers."

"That ain't it, sir," moaned Brimstone. "They smashed my gadgets, 'n'—"

"Gadgets?"

"Yeah. I ain't no good without 'em. And the fellow that made 'em is dead."

He talked on a few minutes more, but Bullard interrupted him. He called in Benton and told him to take notes.

"Go on," he told Brimstone Bill. "We'll make you a set."

It took about an hour before Benton had all the information he needed. Brimstone was hazy as to some of the features of his racket, but Bullard and the young officer were way ahead of him all the time.

"Can do?" asked Bullard, finally.

"Can do," declared Benton with a grin, slamming his notebook shut. "I'll put the boys in the repair shop right at it. They won't have the faintest notion what we want to use 'em for."

Benton rose. As far as that went, Benton himself was still somewhat in the fog, but he had served with his skipper long enough to know that when he was wearing a certain, inward kind of quizzical expression that something out of the ordinary was cooking. His talent for a peculiar oblique approach to any insoluble problem was well known to those about him. Wise ones did as they were told and asked questions, if ever, afterward.

"On your way out, Benton," added Bullard, "take our friend down to the chaplain's room—we left Luna in such a hurry, you know, the chaplain missed the ship—and let him bunk there. I'll see that suitable entry is made in the log. And you might tell Commander Moore that I'd like to see him."

When Benton and Brimstone had left, Bullard leaned back in his chair and with hands clasped behind his neck gazed contemplatively at the overhead. So far, so good. Now to break the news to Moore.

"I've been thinking, Moore," he said when his executive came in, "that we have been a little lax in one matter. I was thinking of ... uh, spiritual values. I'm sorry now that the chaplain missed the ship. Do you realize that we have made no pretense at holding any sort of service since we blasted off on this cruise?"

Moore's eyes bugged a little. The skipper, he was thinking, must have overdone his recent worrying. Or something. Bullard had always been punctiliously polite to the chaplain, but—

"So," went on Bullard calmly, still gazing placidly at the maze of wires and conduits hanging from the deck plates over him, "I have made appropriate arrangements to rectify that lack. I find that the Earthman we took along with the Ziffler outfit was not one of them but a hostage they had captured. He is an itinerant preacher—a free-lance missionary, so to speak. I have released him from the brig and installed him in the chaplain's room, and after he has had a chance to clean up and recover, he will talk to the men daily."

It was well that Moore's eyes were firmly tied to their sockets, for if they had bugged before, they bulged dangerously now. Bullard had brooded too much. Bullard was mad!

"Oh," assured Bullard, "there is nothing to worry about. The man is still a prisoner at large awaiting action by the Bureau of Justice. But otherwise he will have the run of the ship. And, I should add, the run of the town while we are on Juno. He calls himself, oddly enough, Brimstone Bill, but he explains that he works close to the people and they prefer less dignity."

Moore gasped, but there seemed to be nothing to say. Bullard had not consulted him, he had been merely telling him. Unless he had the boldness to pronounce his captain unwell and forcibly assume command, there was nothing to do but accept it. And with a husky, "Aye, aye," he did.

IT was the night before they made Juno that the long unheard twitter of

bos'n's pipes began peeping and cheeping throughout the ship. At the call,

the bos'n's mates took up the cry and the word, "Rig church in the fo'c's'le

ri-ight a-awa-a-ay!" went resounding through the compartments. Bullard clung

tenaciously to the immemorial old ship customs. The sound of bunks being

cleared away and the clatter of benches being put up followed as the crew's

living quarters were transformed into a temporary assembly hall. They had

been told that the missionary brought aboard at Oberon had a message for

them. They had not been told what its subject was, but their boredom with

black space was immense and they would have gone, anyway, if only from

curiosity. The text for the evening was "The Gates of Hell Are Yawning

Wide."

Two hours earlier Benton had reported that all was in readiness for the test of Brimstone's persuasive powers and that the three petty officer assistants picked by him had been instructed in their job. A special box had been rigged at one corner of the hall for the use of the captain and executive. Consequently, when "Assembly" went, Bullard waited only long enough for the men to be seated when he marched in with Moore and took his place at one corner of the stage that had been set up.

Brimstone Bill appeared in a solemn outfit made up for him by the ship's tailor. The setting and the clothes had made a new man of him. No longer was he the shifty-looking, cringing prisoner, but a man of austerity and power whose flashing eyes more than made amends for his poor physique. He proceeded to the center of the stage, glared at his audience a moment, then flung an accusing finger at them.

"Hell is waiting for you!" he exploded, then stepped back and shook his imposing mane and continued to glare at them. There was not a titter or sneer in the crowd. The men were sitting upright, fascinated, looking back at him with staring eyes and mouths agape. He had hit them where they lived. Moore looked about him in a startled way and nudged Bullard.

"Can you tie that?" he whispered, awe-struck. He had been in the ship many years and had never seen anything like it. All the skymen he knew had been more concerned with the present and the immediate future than the hereafter, and the Polliwogs were an especially godless lot. The followers of their own chaplain could be numbered on the fingers of the two hands.

Brimstone Bill went on. Little by little he warmed to his subject until he soon arrived at a stage where he ranted and raved, jumped up and down, tore his hair and beat his breast. He thundered denunciations, pleaded and threatened, storming all over the place purple-faced. His auditors quailed in their seats as he told off their shortcomings and predicted the dire doom that they were sure to achieve. His theology was simple and primitive. His pantheon consisted of but two personages—the scheming devil and himself, the savior. His list of punishable iniquities was equally simple. The cardinal sins were the ordinary personal petty vices—drinking, smoking, gambling, dancing and playing about with loose women. There was but one redeeming virtue, SUPPORT THE CAUSE!

That was all there was to it. An hour of exhortation and a collection. When he paused at the end of his culminating outpouring of fiery oratory, he asked for volunteers to gather in the offerings. Three petty officers stood up, received commodious leather bags, and went among the audience stuffing them with whatever the men present had in their pockets. For no one withheld anything, however trifling. The sermon, if it could be called that, was an impressive success. Then the lights came on bright, Brimstone Bill left the stage clutching the three bags, and the men filed out.

"Amazing," said Moore, as he sat with Bullard and watched the show. "Why, the fellow is an arrant mountebank!"

"Quite so," agreed Bullard, "but the men seem to like it. Come, let's go."

The next day saw a very different atmosphere in the ship. About two thirds of the crew had heard the preaching, the remainder being on duty. Those went about their tasks silently and thoughtfully, as if pondering their manifold sins. They had to take an enormous amount of kidding from their shipmates and a good many black eyes were in evidence by the time the ship slid down into her landing skids at Juno Skydock. Bullard did not let that disturb him; to him it was a healthful sign.

As soon as the ship was docked, he went out and met the dockmaster, who, as he had suspected, was an incompetent drone. No, he had only fourteen men available—he had not been expecting the ship—they would get at the job tomorrow or next day—or at least part of them. No, there was a local rule against working overtime—no, the ship's force could not help—six Earth weeks, he thought, barring accidents, ought to do the trick. Oh, yes, they would be very thorough. At Juno they were always thorough about everything.

Moore started threatening the man, stating he would report him to the grand admiral for inefficiency, but all Bullard said was:

"Skip it, you're wasting breath. These people have just two speeds—slow ahead and stop. Put pressure on them and they backfire. Go back aboard and post the liberty notice. Unlimited liberty except for the men actually needed to stand watch. And see that this goat gets a copy."

Moore shook his head. Something had happened to Bullard. Of course, the man was up against a stone wall, but he could at least make a show of a fight. It was a terrible thing to see a fighting man give up so easily. In the meantime Bullard had walked away and was talking with Brimstone Bill and Benton, who had just emerged from the lock and were looking around.

THERE were lively doings ashore that night. Most of the contingent that had

not heard the Rev. Zander's moving sermon went as early as possible,

ostensibly to look around and do a little shopping. In the end they wound up

by getting gloriously drunk. It was a bedraggled and miserable-looking lot

that turned up at the ship the next morning and there were many stragglers. A

patrol had to be sent out to comb the dives and find the missing ones. Many

had been robbed or cheated of all they had, and some had been indiscreet

enough to draw all their money before they went. Captain Bullard lined up the

most serious of the offenders at "mast" and handed out the usual routine

punishments—a few days' restriction to the ship.

After that things were different. The next day Benton and Brimstone had succeeded in renting an empty dance hall. As Bullard had guessed, things were dull that year in Herapolis. A gang of enthusiastic volunteers—Polliwog converts to Brimstone's strange doctrines—busied themselves in making the place ready as a tabernacle. The last touch was a neon sign bearing the same wording Bullard had seen on that other tabernacle in steamy Venus. Brimstone Bill was about to do his stuff in a wholesale way.

That afternoon when work was done, the entire liberty party marched in formation to the hall and there listened to another of Brimstone's fiery bursts of denunciation. The denizens of the town looked on at the swinging legs and arms of the marching battalion and wondered what it was all about. They supposed it was some newfangled custom of the Patrol Force and that whatever it was, it would soon be over and then they would have plenty of customers. The barkeeps got out their rags and polished the bars; gamblers made a last-minute check-up of the magnetic devices that controlled their machines; and the ladies of the town dabbed on the last coat of their already abundant make-up.

But no customers came that night. For hours they could hear the booming, ranting voice of Brimstone roaring about Hell and Damnation, punctuated by periods of lusty singing, but except for an occasional bleary-eyed miner, no patron appeared to burden their tills and lighten their hearts. At length the strange meeting broke up and the men marched back to their ship in the same orderly formation they had come.

This went on for a week. A few at a time, the members of the first liberty party recovered from their earlier debauch and ventured ashore again, but even those were soon snatched from circulation as their shipmates persuaded them to hear Brimstone "just once." Once was enough. After that they joined the nocturnal demonstration. It was uncanny. It was unskymanlike. Moreover, it was lousy business. Spies from the townspeople camp who peered through windows came back and reported there was something funnier about it than that. Every night a collection was taken up, and it amounted to big money, often requiring several men to carry the swag back.

Strong-arm squads searched the town's flophouses to find out where the pseudo-evangelist was staying, but in vain. They finally discovered he was living on the Pollux. A committee of local "merchants" called on Captain Bullard and protested that the ship was discriminating against them by curtailing the men's liberty. They also demanded that Brimstone Bill be ejected from the ship.

"Practically the entire crew goes ashore every day," said Bullard, shortly, "and may spend the night if they choose. What they do ashore is their own affair, not mine. If they prefer to listen to sermons instead of roistering, that's up to them. As far as the preacher is concerned, he is a refugee civilian, whose safety I am responsible for. He is in no sense under orders of the Patrol Force. If you consider you have a competitive problem, solve it in your own way."

The dive owners' impatience and perplexity turned into despair. Something had to be done. They did all that they knew to do. They next complained to the local administrator—a creature of Fenning's—of the unfair competition. That worthy descended upon the tabernacle shortly thereafter, backed by a small army of suddenly acquired deputies, to close the place as being an unlicensed entertainment. He was met by a determined Patrol lieutenant and a group of hard-faced Polliwog guards who not only refused to permit the administrator to serve his warrant, but informed him that the meeting was immune from political interference. It was not amusement, but religious instruction, and as such protected by the Constitution of the Federation.

The astounded administrator looked at the steely eyes of the officer and down to the browned, firm hand lying carelessly on the butt of a Mark XII blaster, and back again into the granite face. He mumbled something about being sorry and backed away. He could see little to be gained by frontal attack. He went back to his office and sent off a hasty ethergram to his esteemed patron, then sat haggardly awaiting orders. Already the senator had made several inquiries as to receipts since the cruiser's arrival, but he had delayed reporting.

The answer was short and to the point. "Take direct action," it said. The administrator scratched his head. Sure, he was the law on Juno, but the Pollux represented the law, too, and it had both the letter of it and the better force on its side. So he did the other thing—the obvious thing for a Junovian to do. He sent out a batch of ethergrams to nearby asteroids and then called a mass meeting of all his local henchmen.

IT took three days for the armada of rusty little prospectors' ships to

finish fluttering down onto the rocky wastes on the far side of Herapolis.

They disgorged an army of tough miners and bruisers from every little rock in

the vicinity. The mob that formed that night was both numerous and

well-primed. Plenty of free drinks and the mutual display of flexed biceps

had put them in the mood. At half an hour before the tabernacle meeting was

due to break up, the dive keepers all shut up shop, and taking their minions

with them began to line the dark streets between Brimstone's hall and the

skydock.

"Yah! Sissies!" jeered the mob, as the phalanx of bluejackets came sweeping down, arm in arm and singing one of Brimstone's militant hymns in unison. By the dim street lights one could see that their faces were lit up with the self-satisfaction of the recently purified. In the midst of the phalanx the little preacher trotted along, surrounded by the inevitable trio of petty officers with the night's collection.

An empty bottle was flung, more jeers, and a volley of small meteoric stones. The column marched on, scorning to indulge in street brawling. Then a square ahead they came to the miners, drawn up in solid formation from wall to wall. The prospectors were armed with pick handles and other improvised clubs. They did not jeer, but stood silent and threatening.

"Wedge formation," called Benton, who was up ahead. "Charge!"

The battle of the Saints and Sinners will be remembered long in Juno. That no one was killed was due to the restraint exercised by Benton and MacKay, who were along with the church party. Only they and the administrator had blasters, and the administrator was not there. Having marshaled his army, he thought it the better part of valor to withdraw to his office where he could get in quick touch with the senator if need be.

Dawn found a deserted street, but a littered one. Splintered clubs, tattered clothes, and patches of drying blood abounded, but there were no corpses. The Polliwogs had fought their way through, carrying their wounded with them. The miners and the hoodlums had fled, leaving their wounded sprawling on the ground behind, as is the custom in the rough rocklets. But the wounded suffered only from minor broken bones or stuns, and sooner or later crawled away to some dive where they found sanctuary. There had been no referees, so there was no official way to counteract the bombastic claims at once set up by both sides. But it is noteworthy that the Polliwogs went to church again the next night and were unmolested by so much as a catcall on the way back.

"I don't like this, captain," Moore had said that morning as they looked in on the crowded sick bay where the doctors were applying splints and bandages. "I never have felt that charlatan could be anything but bad for the ship. He gouges the men just as thoroughly as the experts here would have. Now this!"

"They would have thrown their money around, anyway," grinned Bullard, "and fought, too. It's better to do both sober than the other way."

THAT afternoon the administrator rallied his bruised and battered forces and

held a council of war. None would admit it, but a formation has advantages

over a heterogeneous mob even in a free- for-all. What do next? There was a

good deal of heated discussion, but the ultimate answer

was—infiltration. The tabernacle sign read, "Come one, come all," and

there was no admission. So that night the hall was surrounded by waiting

miners and a mob of the local bouncers long before the Rev. Zander arrived.

Tonight they would rough-house inside.

He beamed upon them.

"Come in, all of you. There are seats for all. If not, my regular boys can stand in the back."

The roughs would have preferred to the standing position, but the thing was to get in and mix. So they filed in. By the time Brimstone Bill mounted the rostrum the house was crowded, but it could have held more at a pinch.

He was in good form that night. At his best. "Why Risk Damnation?" was his theme, and as he put it, the question was unanswerable. It was suicidal folly. The gaping miners let the words soak in with astonished awe; never had they thought of things that way. Here and there a bouncer shivered when he thought of the perpetual fires that were kept blazing for him on some far-away planet called Hell. They supposed it must be a planet—far-off places usually were. They were not a flush lot, but their contribution to the "cause" that night was not negligible. There was little cash money in it, but a number of fine nuggets, and more than one set of brass knuckles and a pair of nicely balanced blackjacks. Altogether Brimstone Bill was satisfied with his haul, especially when he saw the rapt expressions on their faces as they made their way out of the tabernacle.

The administrator raved and swore, but it did no good. The chastened miners were down early at the smelter office to draw what credits they had due; the bouncers went back to their dives and quit their jobs, insisting on being paid off in cash, not promises. All that was for the cause. There were many fights that day between groups of the converted and groups of the ones who still dwelt in darkness, but the general results were inconclusive. The upshot of it was that the remainder of the town went to the tabernacle that night to find out what monkey business had been pulled on the crowd they had sent first.

The collection that night was truly stupendous, for the sermon's effect on the greater crowd was just what it had been on all the others. Not only was there a great deal of cash, but more weapons and much jewelry—though a good deal of the jewelry upon examination turned out to be paste. The administrator had come— baffled and angry—to see for himself. He saw, and everyone was surprised to note how much cash he carried about his person. What no one saw was the ethergram he sent off to the senator that night bearing his resignation and extolling the works of one Brimstone Bill, preacher extraordinary. He was thankful that he had been shown the light before it was too late.

An extraordinary by-product of the evening was that early the next morning a veritable army of miners descended upon the skydock and volunteered to help scrape the cruiser's hull. Brimstone's dwelling, they said, should shine and without delay. That night even the dockmaster had to grudgingly pronounce that the ship was clean. The job was done. She was free to go.

Bullard lost no time in blasting out. Brimstone Bill was tearful over leaving the last crop ungleaned. He insisted that they had been caught unawares the first night, and the second they were sure to bring more. But Bullard said no, they had enough money for both their needs. The ship could stay no longer. Bullard further said that he would be busy with the details of the voyage for the next several days. After that they would have an accounting. In the meantime there would be no more preaching. Brimstone Bill was to keep close to his room.

At once all the fox in Brimstone rose to the top. This man in gold braid had used him to exploit not only his own crew but the people of an entire planetoid and adjacent ones. Now he was trying to cheat him out of his share of the take.

"I won't do it," said Brimstone, defiantly. "I've the run of the ship, you said. If you try to double-cross me, I'll spill everything."

"Spill," said Bullard, calmly, "but don't forget what happened at Venus. The effect of the gadgets wears off, you know. I think you will be safe in the chaplain's room if I keep a guard on the door. But if you'd rather, there's always the brig—"

"I get you," said Brimstone Bill, sullenly, and turned to go. He knew now he had been outsmarted, which was a thing that hurt a man who lived by his wits.

"You will still get," Bullard hurled after him, "one half the net, as I promised you, and an easy sentence or no sentence at all. Now get out of my sight and stay out."

IT was a queer assembly that night—or sleep period—for a space

cruiser of the line. They met in the room known to them as the "treasure

house." Present were the captain, the paymaster, Lieutenant Benton, and two

of the petty officers who had acted as deacons of Brimstone's strange church.

The third was missing for the reason he was standing sentry duty before the

ex-preacher's door. Their first job was to count the loot. The money had

already been sorted and piled, the paper ten to one hundred sol notes being

bundled neatly, and the small coins counted into bags. The merchandise had

been appraised at auction value and was stacked according to kind.

"Now let's see, Pay," said Bullard, consulting his notes, "what is the total amount the men had on the books before we hit Juno?"

Pay told him. Bullard kicked at the biggest stack of money of all.

"Right. This is it. Put it in your safe and restore the credits. Now, how much did the hall cost, sign, lights and all?"

Bullard handed that over.

"The rest is net—what we took from the asteroid people. Half is mine, half is Brimstone's. The total?"

Benton was looking uneasy. He had wondered all the time about what the fifty-fifty split meant. He was still wondering what the skipper meant to do with his. But the skipper was a queer one and unpredictable.

"Fifty-four thousand, three hundred and eight sols," said the paymaster, "including the merchandise items."

"Fair enough. Take that over, too, into the special account. Then draw a check for half of it to Brimstone. Put the other half in the ship's amusement fund. They've earned it. They can throw a dance with it when we get to Luna. I guess that's all."

Bullard beckoned Benton to follow and left the storeroom, leaving the two p.o.'s to help the paymaster cart the valuables away to his own bailiwick. There were still other matters to dispose of. Up in the cabin Benton laid the "gadgets" on the desk.

"What will I do with these, sir?" he wanted to know. "They're honeys! I hate to throw them into the disintegrator."

"That is what you will do, though," said Bullard. "They are too dangerous to have around. They might fall into improper hands."

"Now that it's over, would you mind telling me how these worked?"

"Not at all. We've known for a century that high-frequency sound waves do queer things, like reducing glass to powder. They also have peculiar effects on organisms. One frequency kills bacteria instantly, another causes red corpuscles to disintegrate. You can give a man fatal anemia by playing a tune to him he cannot hear. These gadgets are nothing more than supersonic vibrators of different pitch such that sounded together they give an inaudible minor chord that affects a portion of the human brain. When they are vibrated along with audible speech, the listener is compelled to believe implicitly in every word he hears. The effect persists for two or three days. That is why I say they are too dangerous to keep. Brimstone could just as well have incited to riot and murder as preach his brand of salvation for the money it brought."

"I see. And the ones carried in our pockets by me and the boys were counter-vibrators, so we didn't feel the effects?"

"Yes. Like the ones you rigged in my box that night we had the try-out up forward. Neither I nor Commander Moore heard anything but ranting and drivel."

"Pretty slick," said Benton.

Yes, pretty slick, thought Bullard. He had stayed the prescribed time on Juno and had paid off the crew and granted full liberty. Outside the five men in his confidence, not a member of the crew had had a hint that it was not desired that he go ashore and waste his money and ruin his health.

"I'm thinking that the Pollux is not likely to be ordered back to Juno soon," said Bullard absently. But Benton wasn't listening. He was scratching his head.

"That little guy Brimstone," he said. "He isn't such a bad egg, come to think of it. Now that he's pulled us out of our hole, do you think you can get him out of his, sir?"

"He never was in the hole," said Bullard, reaching for the logbook. "I needn't have kept him at all once I let him out of the brig. Read it—it was on your watch and you signed it."

Benton took the book and read.

"At 2204 captain held examination of prisoners; remanded all to brig to await action of the Bureau of Justice except one Ignatz Zander, Earthman. Zander was released from custody, but will be retained under Patrol jurisdiction until arrival at base in the event the Bureau should wish to utilize him as witness."

Benton looked puzzled.

"I don't remember writing anything like that," he said.

"The official final log is prepared in this office," reminded Bullard, softly. "You evidently don't read all you sign."