RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Emil Doepler (1855–1922)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Emil Doepler (1855–1922)

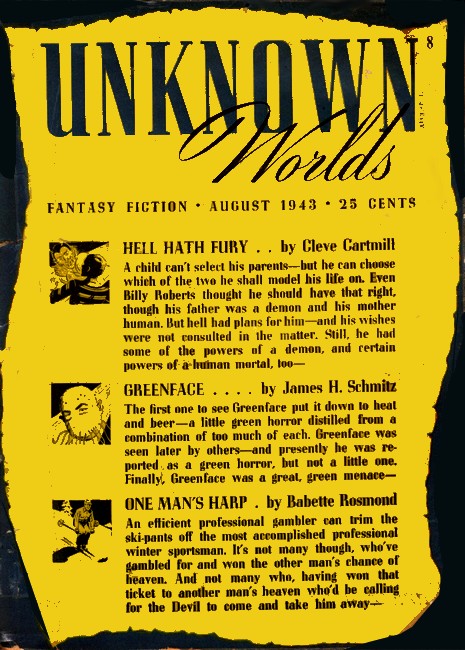

Unknown Worlds, August 1943, with "Heaven Is What You Make It"

She was a very determined woman. She was determined to fight in battle—and did, and died. And thereafter—she was determined to make the heaven she was misdirected to suit her—

OMMODORE Sir Reginald Wythe-Twombley, R.N., D.S.O., et cetera, sighed deeply and twisted unhappily at his gray mustaches. Damn these strong-minded women—especially the American variety. Why do they persist in pushing their noses in where only men belong?

"Well?" she demanded. She did not tap her foot, or plant her hands on her hips. It was unnecessary. That "well" contained both. And a lot else.

The harried commodore sighed again. As if he didn't have trouble enough already. He could only suppose she had done it that way in London, too. How else could she have obtained that absurd letter from the minister? Yet he had to dispose of her.

"But, my deah," he protested, "after all! As a nurse, now, or a lorry driver that would be practicable. But to go into a Commando unit as just ... just ... why—"

"The letter is clear," she reminded him, icily.

She stood there, imperturbable and determined. She was big for a woman—a darkish blonde with cool gray eyes and a chin that might have been chiseled out of granite. Her passport gave her age as thirty-three. It may really have been that, but she was of the type that did not suggest queries as to age. Her most salient characteristic was competence. She fairly oozed efficiency at every pore.

The commodore couched.

"It happens"—he tried to hedge—"that ... uh ... there are none of our units in the Orkneys just now. Of course, if you are very insistent about it, you could wait here at Kirkwall, but I assure you you would be more comfortable in ... well, Edinburgh, let us say."

"What about the Tordenskjold?". she asked, with a firmness that reminded him painfully of a former governess. "I understand it is about to raid the Vigten Islands and Namsos Fjord."

"Quite so," he admitted, grudgingly. At least she seemed to be well informed. "But it is officered and manned entirely by Norwegians, Danes and Frisians. You would not—"

"I speak all the Scandinavian languages fluently," she said, coolly. "Moreover, to save you your next remark. I might remind you that I have been principal of a school in the Gowanus Canal section of Brooklyn for the past ten years. I've handled roughnecks and hoodlums beside which even your dreaded Nazis are gentle. As for these fine men who will be my comrades—Well!"

The commodore surrendered. He hated to do it, for the Tordenskjold was going on something very much like a suicide mission, but he reached for a pad of blank chits. Fie scribbled a few lines on it, and then his initials. He felt himself a weakling, for the first time in many years, in taking the easy way out with t-his woman. But she still stood there, unmoved, looking at him and waiting. Then he called his orderly.

"Have the cart out," he told the marine, "and take Miss ... Miss—"

"Miss Ida Simpkins," she supplied, without a quiver of an eyelid or a trace of thanks.

"Er, Miss Simpkins," continued the commodore, "to the dock at the North Anchorage in the Flow. Put her in the Norwegians' boat and then return."

The marine saluted, and picked up Miss Simpkins' bag.

She sat stonily beside the driver all the way, looking neither right nor left. Once or twice the driver attempted conversation. but he spoke a strange archaic language that was neither Scandinavian, Scotch nor yet Gaelic. The marine sat moodily in the back of the' cart with the bag for company. Like his superior, he sighed, too, from time to time, for he was a veteran of the last war and knew that such things as this had never happened on earth or in heaven before.

The kommandör-kaptein of the quaint old cruiser received her with more equanimity than any other military man she had encountered since her strange quest began—the Saturday after Pearl Harbor. He merely read her papers through, asked three crisp questions, and assigned her to duty. She was to be the bridge messenger on the starboard watch. She was told where she could sleep and eat, and that was all there was about it. Dusk was already at hand, and shortly the old ship and the destroyer Garm would be stealing out through Hoxa Gate. Tomorrow promised to be foggy, so that under its cover they might possibly reach their destination after all. It was on those things the captain was thinking, not on the unorthodox addition to his crew.

T was early in the evening of the next day that they began to close with the rugged land. The mists had held and the sea had been calm. Except for a heavy ground swell that made the vessel wallow constantly, the voyage had had no outstanding feature. The men, grim-faced and ready, and bundled up in heavy clothes, stood always by their guns, which were loaded and trained outboard for anything that might loom suddenly on their beam.

It was just at seven bells it happened. The fog had been thicker for the past half-hour, when suddenly it lifted. A scant three miles away a large ship was charging along, throwing spray over her bridge at every swell she met. Its silhouette was unmistakable. She was a Nazi cruiser. In another instant the guns of all three ships were blazing.

The little Garm looked as if she would capsize, as she heeled under hard-over rudder and full speed to make her torpedo attack, but her larger consort clung doggedly to the old course. After that first moment, nothing was very clear. Geyserlike splashes bloomed suddenly close aboard, with deafening noise as the sensitive shells exploded on contact with the water. Spray showered the ship, and in it were deadly shell fragments. The löitnant of the watch received one such in his left eye and another in the knee. He fell to the deck with a brief groan.

"Get Fenrik Janssen," he muttered. "Quickly."

Miss Simpkins ran aft to where she knew he would be, by the 5.9-inch battery control station. But just as she was well clear of the bridge, another salvo struck. That one was a fair straddle, and many things happened, fore and aft. The bridge went up in a fountain of flame, smoke and splinters, and with it the captain and the wounded lieutenant of the watch. The after turret spouted fire heavenward, which meant it had been penetrated and whatever powder was exposed ignited. It was clear that the minutes left to the faithful old warship were numbered.

Miss Simpkins sprang to the nearest broadside gun, where she saw the trainer—a mere boy—sagging in his saddle. She embraced him with capable arms and lifted him out; then laid him gently on the deck. Half his head was gone. After that she climbed quietly into the place she had thus vacated, and grabbed the handles of the training gear. She flattened her face against the butler of the sight and found the Nazi cruiser. She tried the handles, and found that by turning them this way and that, she could bring the vertical crosswire she saw inside the telescope so that it would be in alignment with the German's principal mast. She supposed that that was the idea, so she held it there, though every few seconds the gun beside her would go off with a snapping bark that nearly caved in her eardrums. Moreover, it jolted her to her very skeleton as it lashed backward in its recoil, and the muzzle blast smote her from head to foot.

But she clung on, doing her bit as she saw it—saw bright blossom after bright blossom flower on the hated enemy's side, and saw the orange ripple of flame that marked his return of the compliment, She knew from the acrid smoke that drifted past her own nostrils that her own ship was afire, but she noted with grim delight that so was that of the Nazis. For an instant she got a glimpse of the sinking destroyer, itself blazing from stem to stern. And then she saw the vast explosion that rent the German. She saw that instantaneous blot against the sky, shot through with flame, and knew it was the Garm's last torpedo that must have done it, for suddenly she realized that her own gun had been silent for fully a minute now.

Indeed, there was no sound whatever about her, except the wild hiss of escaping steam and the crackling of flame. There was an almost inaudible moaning somewhere in the murk, but not the boom of cannon. She slid off her seat and looked about her. All she could see through blistering smoke were the legs of a dead man lying directly behind the gun. That would be one of the loaders. Then something struck the ship a blow that shook it as if it had hit a rock at full speed. Almost in the same instant there was a concussion of such stupendous violence that Miss Simpkins had only the vaguest impression of it. She only knew she was being hurled upward and outward. The dying Nazi must have delivered its own torpedo as its swan song—that was her only thought.

She was very numb about the whole thing. It had all happened so quickly, and she had been utterly unprepared. She did know, though, that she had done her best, and hoped it had helped. She was starting to fall then, and wondered how it would feel to drown. Or did it matter?

It was then that what she thought was her delirium started. There was a jumble of wildly mounting music, queer triolets that reminded her somehow of Wagner and grand opera—though it must have been from a record she had heard somewhere, since she thought opera both sinful and a waste of time and money. There was a distant, but approaching chorus of yoo-hooing— "Yohohoto, yohohoto, ahiaha!" it went. Last of all she saw the horses! A cavalry charge from the skies! Dozens of galloping horses were bearing down on her, and on each was mounted a fierce Amazon, armored and helmeted and waving a spear and yelling at the top of her lungs.

"So death is like this," thought Miss Ida Simpkins, bitterly, "and I always supposed it would be angels who would come, not heathen apparitions."

She was not far from the water by then. The dark waves were rushing up to meet her. It was at that moment that a great white charger swooped beneath her and a strong left arm swept her into its embrace. It was a woman's arm, and snowy white, and in the next instant Miss Simpkins felt herself pressed against two breasts encased in golden chain mail. They were zooming upward next, and the Amazon rider of the horse, a powerful woman with honey-colored hair, was bending forward to kiss her.

"No, NO!" screamed Miss Simpkins, fighting fiercely at her.

But it was of no use. The warrior blonde's full red lips were against hers, full of tender kiss. Miss Simpkins tried one final struggle, but to no avail. She was in cool darkness now. There was no woman, no horse, no ocean—nothing. And Miss Simpkins knew exactly what that meant. Ida Simpkins was dead.

N blackness there is no sense of time. Who knows? Perhaps there really is no time. Nor was there time in the gray stage that followed. It was a formless sort of gray, like the inside of a cloud, where there is nothing overhead or beneath or to any side. But Ida Simpkins had a kind of awakening. She was aware of herself again. She was capable of memory, and thought, and even reasoning. It puzzled her. Was she dead, or wasn't she? Maybe she had been picked up and was merely sick. Or could it be that all her ideas of the hereafter were not exactly correct after all. Perhaps this was a transition stage of some sort.

For her ideas of the hereafter had always been most definite. It was a thing that had interested her profoundly, and she had been wicked enough—though a devout and unyielding Methodist—to read the outrageous, beliefs of all the pagans, and even the mistaken views of some of the other sects of her own general faith. There was nothing in any of it that resembled this endless grayness. It was tedious, maddeningly monotonous.

She tried thinking about her past; of her strict upbringing, and how steadfastly she had always hewed to the line. She remembered well those days of schoolteaching in blighted districts, of physical instruction, and of having to learn not only boxing and wrestling, but jujitsu, so as to be able to handle the tough boys she taught. All that seemed so long ago now, though in reality it could have been but a few months. For her martial career had been a short one. One brief day, to be precise, leaving out of account the two months' battle she had had to get the opportunity to die the way she did.

Ida Simpkins had always been a profound pacifist. It was one of her many strict ideals. Smoking, drinking and gambling were wrong to her because they were injurious and wasteful, as well as sinful. Fighting and war were wrong for the same reasons, except that war embraced all the vices on such a grand scale as to be the most hateful of them all. The rape of Europe and China had offended her sense of propriety, but she had entertained the feeling that those crimes were foreign affairs. That in a sense it was due punishment for their own foul crimes. Were not the Chinese pagans? Were not the French and Viennese notoriously loose-lived? All right-thinking persons knew those things.

It was war for America that she was against. The draft was wrong, any preparation was wrong, since it implied the recognition of that which should be firmly denied. It was Pearl Harbor that jolted her out of that beautiful but impractical belief. It was late that Sunday when she first heard of it, and all that night she lay in harrowing combat with herself. Must one fight, or should one turn the other cheek? Ida Simpkins was in a dreadful dilemma. For she was a good Christian, as she understood the term, but when it came to the cheek-turning business she was notoriously stiff-necked. Her struggle with herself went on through that night and the next and next. It was nearly dawn on Wednesday when she arrived at her decision. At that moment she threw pacifism overboard and went all out for belligerency. Thereafter, she practiced it with all the fanatical fervor she applied to her other ideals.

It was not until Saturday of the same week that she penetrated the last barrier and came face to face with one of the Powers That Be. Sorry, no, they told her in Washington, but we have no battalion of death—not yet. Maybe there will be a Woman's Auxiliary Service later, something on the order of what the British have, but that is a long way off. That was enough for her. She wangled a passport and managed to get to England. There she pestered an already overburdened War Ministry until she got the coveted letter she sprang on the bewildered commodore at Kirkwall. She battered down his defenses. She got to the front. And now—now the war was over, as tar as she was concerned.

She quickly tired of memories, being no introvert. The perpetual grayness began to pall on her. Was it going to be like this all Eternity? She had a wholesome respect for Eternity. Eternity was a long time, and one should arrange his life so that it would be spent in reasonable comfort. She remembered all that from a very long way back, and had faithfully followed the rules taught her.

Was this interminable grayness to be the reward?

But she was in the beginnings of awareness of other things than mere featureless grayness. There was a sense of physical contact, of lying jackknifed face down on a moving something. As her senses became acuter, her impressions became clearer. She was lying across something short-haired and warm, and it had a detestable horsy smell. She could feel muscles and bones working beneath her, and then she knew that she was nearly naked. All that she had on were her panties, and a firm hand held them by the seat in a tight grip.

This is madness, she thought at first, until her dying dream began slowly to piece itself together again in her consciousness. But what troubled her most just then was the sense of being undressed. In her dazed and buffeted condition while at the trainer's seat at the gun, she had not noticed that the blast of every shot or every nearby bursting shell had blown some garment to shreds and entirely off her. All that was left, apparently, were the panties. But those, thank goodness, were durable—being, as they were, heavy knitted bloomers. But what was she doing face down on the shoulders of a galloping horse, and who was it holding her on? Then the dream stood forth in perfect clarity. That woman—ugh!

DA SIMPKINS opened her eyes and squirmed. All she could see was the plunging shoulder of the horse and a white human leg from the knee down. It was a naked leg—like her own, only plumper, or perhaps beefier would be the word. Ida clawed at the charging horse and tried to get upright, to slide off behind—anything. It was disgraceful for her to be in this grotesque pose—her, Ida Simpkins, formerly mistress of Gowanus Settlement House! Who did this so-and-so who had kidnaped her think she was, anyhow?

But the so-and-so's grip was unbreakable. However, she quickly shifted it to an embrace, and before Miss Simpkins knew what was happening, she had been picked up, upended, whirled about, and set astride the horse facing her captor.

"Hail, hero! Yo-ho!" shouted the beefy blonde. "I'm Brynhild—"

Her mouth dropped open and Ida thought for a moment she was going to fall off the horse. The horse seemed to sense something, for it slowed its mad gallop to an easier pace.

"Y-v-you're a woman!" gasped the Valkyrie, as if the utmost in sacrilege had been done. "How did I get hold of—"

"Of course I'm a woman," snapped Miss Simpkins.

"But it was a ship full of Norse heroes," protested the Valkyrie, "fighting against odds. Me and my girls—"

"My girls and I," corrected Miss Simpkins, firmly.

"My girls and I were watching from afar," continued Brynhild, still so taken aback by the scandalous error she seemed to have committed that she accepted the reproof meekly. "You were the last survivor, serving nobly at a gun and surrounded by raging flames. The ship blew up and you went up with it. I gathered you up in fragments as you rained down. It might have been better if I had had a bucket. I must have mixed things up—somehow."

She finished lamely, and shook her head dazedly. War in the good old days was not like this. All you had to do then was gather up a spare arm or ear or so, and maybe a head, and you had all your hero—and nothing else. The way things were going now, a poor battle maiden never knew what she was getting.

"So what?" Miss Simpkins wanted to know, entirely unmoved by Brynhild's discomfiture. "What am I being taken for a ride for? Why did you horn in on my affairs, anyway?"

"Because," explained the badly rattled daughter of Wotan, "I thought you were a Norse hero, and should be taken to Valhalla along with the others. See them—over there? And Bifrost ahead? The bridge that only gods and heroes may cross?"

Miss Simpkins looked, blinked and looked again. Sure enough, a whole squadron of cavalry was charging along their flanks, each steed with a Valkyrie and a sailor astride. She had to twist her head to see the bridge, but there it was, unmistakably—a great, glorious rainbow that had thickness as well as breadth, rearing itself above the clouds they rode upon.

Brynhild did not look happy.

"Were you really a warrior," she asked, finally, "or did I make a terrible mistake? According to the Law, no woman has, or ever will, set foot within Asgard."

"I was aiming a gun," replied Miss Simpkins sharply, "if that's what you mean by being a warrior. By the way, how long have I been dead?"

"A long, long time," answered Brynhild, cryptically, "and in the other direction."

Ida Simpkins thought that over. Dead a long time, huh, and headed for Valhalla! She knew her mythology, having studied it and taught it to the tough brats of Red Hook. Up to this moment everything was regular—providing only she were ancient Norse. There was the business of death in battle, the death kiss of the Valkyrie, and the translation to Valhalla. That, she knew, lay just over the bridge that was close ahead. It was a rowdy place, as she recalled it, but—

"If you hadn't been so darned hasty," reproached Miss Simpkins, with considerable acidity, "my own people would have got me. As it is, I don't know how to get back. I guess we'll have to go on now', even if it breaks your old law. It's a fool law anyway. I'm not going back to the gray place, I can tell you that, sister."

"We'll see what Heimdall says," said the Valkyrie, in some dejection. "He's the guardian of the bridge."

Ida Simpkins said nothing, but squirmed around so as to face the way the charger was going. The whole situation was bitterly clear now. It was a tough break to die and get taken to the wrong heaven through someone's clumsy interference, but if that was the way it was to be, so it was to be. At least, before she made any hasty decisions, she meant to look the place over and see what possibilities it had. It might be a sinful thing to spend Eternity in a heathen heaven, but who knew? There might be a purpose behind it.

That was the sweet, consoling thought that sustained her. Didn't missionaries spend their lifetime among the benighted heathen? She could not but be thrilled.

Come to think of it, had any missionary ever penetrated so deeply into the territory of the misguided and the nonbeliever? She saw a great mission ahead, and the light of battle came into her cold gray eyes and the granite mouth set itself on the old familiar lines. On to Valhalla! Ida Simpkins' work had just begun!

HE passage of Bifrost was a truly nerve-shaking experience. The frail but beautiful bridge quivered, swayed and bucked under the thunderous hoofs of the cavalcade bearing the honored dead. Ida looked down once only and gasped. The bridge was built of nothingness—a curious web of interwoven strands of fire and air and water. Its dazzling iridescence was almost more than human eye could bear.

Then they were at the summit of the great bow. Brynhild's steed, and the others following, slowed and came to a halt at what appeared to be a tollgate barring the road. At the right was a gold-plated shack, set upon a bracket extending out over an abyss so deep that Miss Simpkins dared not think about it. By the side of the door hung a huge trumpet. In the door stood a tall, fair young man in silvery armor. That must be Heimdall, keeper of the bridge and chief greeter of the fallen heroes.

He stepped out and unlatched the gate.

"You did well, Brynhild," he remarked, making a sign for the rest of the cavalcade to pass. "This will prove the greatest hero of them all. I have sharp eyes and ears, you know, and can see and hear for thousands of miles and thousands of years. This is a day that will never be forgotten in Valhalla."

Miss Simpkins compressed her lips still more firmly. That was just what she was thinking. But as she looked down at herself, it annoyed her to be in her present state of dishabille. She yearned for more adequate covering than the gray panties, useful though they were. Heimdall must have read the thought, for he entered his golden shack and at once reappeared with an armful of cloth and glittering hardware.

"With the compliments of Alberich, King of the Dwarfs," he said, bowing. "Magic has been worked into these garments. While they are intact, no man can harm you."

"Intact or not intact," snapped Miss Simpkins, "just let one try!"

But she snatched at them and, although it irked her to dress herself by the side of a public road with a flock of leering dead seamen galloping by, she managed to get the outfit on, though Brynhild had to help her with some of the straps and buckles. By the time the job was finished, she was rigged out in a style similar to that affected by the Valkyries, except that she was given a short sword instead of a spear.

"But what will papa say?" asked the worried Brynhild.

"Ah," smiled the ever-agreeable Heimdall. "I wonder."

Brynhild helped Ida mount, much to the latter's annoyance, but she found she could not manage herself very well in the cumbersome gold armor. Then they thundered on in the wake of the other heroes, hearing a gentle farewell toot of Heimdall's horn as they left.

They galloped down the other half of the bridge and into the shimmering, gold-leaved grove called Glasir. Even the ultra-practical Miss Simpkins was impressed by it, for it was all it was cracked up to be, not like the fabulous "palace" Heimdall was reputed to have atop the bridge. After a little they came out onto an extensive flat place. Ida Simpkins' reaction was that she had entered a vast airdrome, for the field was large enough to accommodate the armies of the world, and beyond stood an immense building that could easily have housed a score "of Zeppelins. But she knew from its silvery, fluted walls, and the roof of overlapping golden shields that it must be the great hall of Valhalla. Distant as they still were from it, she could hear the resounding cheers of the old-timers as they hailed the newcomers. Ida Simpkins tightened herself for the coming fray, for she intended to take no nonsense from any of them, not even Wotan himself.

"Don't forget." cautioned Brynhild, icily, for she was heartily sick of her find, "that when papa presides over the veterans, he styles himself Valfather."

"It's all one to me," said Miss Simpkins, indifferently. She firmly resolved never to board another horse again without at least thick stockings on. This one shed horribly and she knew the insides of her bare legs were plastered with white felt.

HEY rode in through a portal that would have admitted a battleship, and straight up through an aisle made through a mob of howling, armored men—huge, beefy, red-faced men, all of them, many with red or yellow beards and drooping walrus mustaches. On a dais far ahead, stood a spare man in armor, wearing a winged helmet. As they drew nearer, Ida could make out the missing eye. Yes, that was the Valfather.

Just before the throne, the horse stopped abruptly, and Ida slid off—over its fleck and head. She got up crimson, furious with Brynhild, the horse, and herself. But neither Wotan nor Brynhild were looking at her.

"Another Valkyrie?" Wotan was asking, looking a little baffled. "My memory seems to have slipped. Really, I must see Mimir soon. Who was her mother, and in what country did she live? Perhaps I may recall the incident."

Miss Simpkins was not to be put upon. Before Brynhild could answer she spoke up for herself.

"I'm a Valkyrie. Catch me traipsing all over the country picking up strange men, and dead ones at that! And you can't make me wait on tables here, either. It may be a technicality, but I'm a hero, and as such I want my rights."

"A hero?" asked the Valfather, dumbfounded, rolling his one good eye solemnly from first one of them to the other.

"That's what I thought," said Brynhild, defiantly, "and that's what Heimdall says. He let her across the bridge. That's something."

"Oh, dear," said the Valfather, anxiously. "Those Norns are holding out on me again. Why didn't I know about this before?"

Miss Simpkins could think of nothing appropriately tart to say to that. Nor did she care to. For she was beginning to relax a little and there was something about the bewildered old man that appealed to her. He seemed so good, yet so utterly impractical. She regarded him for a moment with speculative eyes. A man like that had possibilities—salvage possibilities, that is. Under firm management, he might eventually amount to something. At the moment, he seemed completely lost in the face of the inexplicable situation that had suddenly confronted him. And not unnaturally, for it must be embarrassing to a self-styled god who supposedly knows the past, present and future to its utmost detail, to have something laid in his lap that wasn't in the book. Something had to be done.

"Well, I'm here," snapped Miss Simpkins. "When do we eat?"

"Yes, yes, of course," said the Valfather, hurriedly, and clapped his hands. A tall old geezer with a shiny bald head and flowing white beard stepped forth, plucking a few tentative notes on a bejeweled harp he carried.

"Sound mess-call, Bragi," said the god of all the heroes, and sank limply onto his throne.

"Just take any vacant seat, dearie," said Brynhild in Ida's ear. "You're on your own now."

Miss Simpkins gave her a dirty look, but it was wasted on dimpled shoulder blades. Brynhild was making for the kitchen. A Valkyrie's work is never done.

In the meantime the milling crowd of heroes were beginning to sort themselves out and line up along the many long troughs that covered the floor of the vast hall. There were benches on one side of the troughs, and the warriors were shucking their outer armor and stacking it beside the place they meant to sit. Ida had a look about. Wotan seemed to have gone to sleep. There seemed to be no course open except to follow the catty advice she had just received. So she walked over to the nearest table where men were beginning to seat themselves. They were spread out pretty well, but there would easily be room for another if they would move over a little. She came up between two big huskies and pushed them gently but firmly apart. Then she unbuckled her sword belt and laid it down on the bench. She was reaching for the corselet buckles when the storm broke.

"Hey," said the big bruiser on the right, "what's the big idea? Get in the kitchen where you belong and hurry up with the chow."

Her answer was to unsnap the holdings of the corselet and fling it on the bench. Then she calmly sat down beside it. A roar went up that filled that entire side of the hall. A hairy paw snatched at the back of her neck and a blustering voice began to say something. Whatever it was, it never got said, for it turned into a howl of pain and rage. A small but strong thumb was digging into a vital nerve of the gripping paw, and another small but strong hand had seized the elbow farther up. There was a mysterious twist, a heave and another twist, and the hero went flying headfirst across the trough and lit face down a dozen feet beyond. He skidded on, plowing up the sawdust for another yard or so, then sat up with a groan.

"That," announced Miss Simpkins, calmly, standing now and facing the circle of amazed heroes that had come up, "is known as the Kata Otoshi, or Shoulder Overthrow. A very tricky race of warriors called Japs invented it. Do any of you want to make something of it?"

There was a gleam in her eyes that had not been there since the day of the big riot back there on the back water front of Brooklyn. It seemed that nobody cared to make anything of it. Moreover, fighting in the hall was a breach of etiquette. They would have all afternoon for that out on the field.

"To set you straight." she added, "I'm a certified hero, like it or not."

Suddenly there was a great gust of laughter throughout the hall. Her victim was getting dazedly to his feet, rubbing his skinned nose with one hand.

"Ha. Gunnar," yelled one tall Viking, "how does it feel to be tossed on your ear by a woman?"

Gunnar growled and turned away amidst the guffaws of the crowd. He went over to another table and sat down, leaving his arms and armor where he had left it on the seat beside Ida Simpkins. She swept them off onto the floor to make more room beside her. Everywhere the men were sitting down now, though there was much conversation going on behind the backs of hands into ears. Heimdall's prophecy had matured faster than most. It was indeed a day to be remembered in Valhalla. For few of the heroes had a greater reputation for toughness in a rough-and-tumble than Gunnar, brother and slayer of Sigurd, the lover of Brynhild. The reverberations in Asgard would not die down for ages.

But a distraction was at hand in the form of food. Columns of Valkyries were deploying into the hall, each Valkyrie either bearing a huge tray of smoking meat or a horn of mead. They had shed their armor and were now in long white gowns with their yellow hair hanging free about their shoulders. Still other Valkyries were coming along the bench side of the troughs, handing out drinking vessels. One stopped sulkily beside Ida and handed her a silver-mounted white stein. It was a ghastly-looking thing, being fashioned out of a freshly scraped human skull. The mouth, nose and eyeholes had been deftly plugged with chased silver.

"What's this thing?" demanded Miss Simpkins.

"Your drinking mug," answered the handmaiden. "It is made from the head of one of your enemies. You got fourteen, according to our count, but the other thirteen are not made up yet. They'll be up later."

"Take it away," said Miss Simpkins, firmly, "and bring me a glass of water. I don't drink mead, and I won't drink out of that thing."

"Water?" echoed Skaugul, for that was her name. "What is this 'water'?"

"Water," reiterated Ida, "the stuff they fill lakes with—what they poison to make liquor of."

"But here everyone drinks the lovely mead—"

"Up till now," snapped the ex-schoolteacher. "Now, listen, don't start any arguments with me. I've passed all the tests and here I am—a hero. As such I rate anything I want. If these dumbbells are content to guzzle the slop they do, that's their affair. I want water. Get me?"

Skaugul took on the same unhappy look that Ida had noticed several times on Brynhild's broad face. She went away. Presently she came back—and with water. In the meantime the line of Valkyries had passed by on the far side of the trough, filling skulls as they came, and dumping enormous quantities of what looked and smelled like barbecued pig into the troughs.

"Skol!" rang out tens of thousands of booming voices in unison, as all lifted their drinking mugs and emptied them. Miss Simpkins took a sip of her precious water. She had already noticed a lot of things about the service that were going to be bettered before she lived much longer; but, after all, Rome wasn't built in a day. Her companions up and down the line were grabbing up joints of the roast pig with both hands and cramming them into their mouths. The entire Valkyrie force was now concentrating on the almost impossible task of keeping the mugs filled. Miss Simpkins ignored them all. Instead, she fumbled amongst her cast-off armor and found her little sword and drew it. With it and the one hand she could not help getting greasy, she sliced off a small sliver of the part of the carcass in her section of the trough.

It was not bad, though a little gamy, and she ate another slice. Her fellow heroes had already gone through their first joints and, after some intermediate burping on a truly colossal scale, had tackled their seconds. A few hearty eaters were even yelling for thirds, which were promptly brought on the run by the obedient Valkyries. After a little they began giving up, one by one, and sat back on their benches in sated contentment, taking only a gallon or so of the abundant mead as the ultimate chaser. Miss Simpkins beckoned Skaugul, who had been hanging around somewhat frightenedly in the immediate background.

"No vegetables? No greens? No dessert?" demanded Ida, coldly, knowing perfectly well there were not.

But Skaugul merely looked blank and a little scared. She bobbed her head in what might have been an attempt at a curtsy of a sort, then scurried away. It was a long time before she returned, but return she did, and with a bowl of dark-green leaves. Her guest glowered at them.

"From the tree Yggdrasil," said the poor little Valkyrie, trembling. Ida did not know it, but Skaugul had always thought a lot of Gunnar. Next to Thor, she always told the other girls—

Ida was glaring at her.

"Greens, you said," Skaugul explained, timidly. "Heidrun eats them. Maybe you could."

"Who's Heidrun?"

"She's the goat—the one that gives the mead." By that time Skaugul was on the verge of collapse. Greens this strange female hero had asked for, and greens she had brought—the only green thing on Asgard. It was all very weird, but there was at least the precedent of the goat. So Skaugul saw no harm in mentioning it.

"Skip it," snorted Miss Simpkins. She was going to have to tackle this problem nearer its source. There was no use in punishing the child more. She tried to close her ears to the mouthsmacking and belching that filled the hall about her. She thought grimly for a moment on this subject also. What beasts uncontrolled men can be, she thought. And when Ida thought about control—well, there was only one proper kind of control in Ida's mind. That was the Ida-directed variety. She might have begun to do a little planning then and there, but at once a great shout filled the hall.

"Let's fight!" it boomed, and on the instant the men were heaving their stuffed bulks off the benches and clambering into their harness. A number were already dressed and on their way out. Ida looked at her own little pile of gilt junk and decided to leave it where it lay. It might do for ceremonial occasions, but in a fight it would be a distinct handicap to her. For she firmly intended to attend the fight. It was the custom, and she was resolved to follow the customs. Oh, she would modify them, bit by bit, but still she would not buck them.

"I'm Sigmund," bellowed a towering blond giant beside her. "How's for a little scrap? Berserk, you know, with no holds barred." She noted that he had left off his hardware as she had done. "I want to get the hang of that stunt you worked on Gunnar. Ha, ha, ho, ho, haw, haw!"

"Lead the way," she said, crisply.

HEY were late getting onto the field. By the time they arrived practically everybody had teamed off and were going at it hammer and tongs. There were many styles of fighting in progress. Some combats were duels, others between groups. Some men fought in full armor with buckler and long sword, others dispensed with the shield and flailed about them with eight-foot two-handed swords that were about as light as crowbars of the same length. Still others used war clubs and maces, and some hammered away with mailed fists. There were wrestling matches as well.

Some of the fights had already terminated, for the ground was beginning to be strewn with stray heads, severed arms and legs, and not a few of the heroes lay on their backs, split from shoulder to navel by some lucky swipe of a battle-ax. Miss Simpkins picked her way through the carnage with considerable disgust, though she knew that they would all come alive when mess call sounded again. Oh, what a wacky place, and how lucky for them that she had at last got there!

They eventually reached a comparatively clear spot, about a mile from the hall. Until then they had had to duck and dodge repeatedly to avoid losing their own heads through the backsweep of the sword of some fighter too intent to note what was going on behind or beside him. Ida stopped, and Sigmund walked on beyond about twenty paces. Then he turned, vented a tremendous roar, and charged.

She stood stock-still until he was almost upon her. At that, she gave but a little bit—just enough not to be bowled over by the impact. She did not go into action until his arms were already about her, ready to begin a bearlike squeeze. Then a lot of things happened fast. Something gouged him in the small of the back, and a sharp elbow was sticking in his throat. Sigmund hit the ground, bit out a hunk of turf, and came up yelling.

He closed again, but that time she did not throw him. She grabbed one hand and crossed his arm with hers. Then she snuggled up to him and twisted.

He howled with pain and refused to go down on his knees as any mortal would have. So she increased the pressure by a hairbreadth and was slightly sickened by feeling and hearing the bones pop. Not that it mattered. They would be whole in time for dinner.

He staggered back, looking incredulously at his dangling arm, folding it up and down across its break to make sure there was no mistake about it.

"W-wh-what ... how?" he stammered.

"The first maneuver," she replied primly, "is known as the Sora Towoshi, or Sudden Fall. The second treatment is called Ude Ori, or the Arm Break. You should have dropped to the ground. Then I would not have had to spoil your arm."

He could only gaze and fiddle with his arm in blank amazement. Yet he towered a good foot above her and probably tipped the scales at three hundred flat. It wasn't reasonable!

Ida Simpkins was aware of a sudden hush on the battlefield. Hundreds of whole and maimed heroes had knocked off their encounters and were hurrying up to see the fun. In a moment there was a deep ring about them, listening open-mouthed to the stories being told by the score or so that had witnessed Sigmund's trimming. There were deep curses, or heavy sighs, depending upon the temperament of the auditor.

"It's magic," whispered one, but in the voice of the gale.

"Stuff and nonsense," whipped out Miss Simpkins. "Who said that?"

A burly man clad in red-gold armor, complete with shield and broadsword, stepped sheepishly forward.

"Me. Hogni. I say it's magic. But it will not avail against an armed man. Not a man of courage and skill."

"Yeah? Well, come on and do your stuff. I'll show you the Taka Tooi. It's not magic, but it'll stop you."

Hogni seemed to regret his outspokenness, for he showed no anxiety to put his words into action, but the hoots and jeers of his mess-mates soon stimulated him into action. He twirled his sword and charged in the same reckless bull-fashion that Sigmund had. A gasp that must have made every leaf on Yggdrasil quiver rose from the watching crowd. For the woman stood quietly waiting, the only tense thing about her her eyes. Then he was upon her, with his sword upraised for the smashing cut that would have split her to the pelvis. But it never fell. Like lightning, a hand shot up and grasped his wrist, yanking the charging hero forward, and twisting at the same time. In the same split second she interposed her heel behind his and gave a sidewise shove. Hogni spilled quite neatly a couple of yards away.

Ida gave him an appraising look as he scrambled, muttering, to his feet. He was really enraged now, as the whole of Valhalla made the welkin ring with their ribald comment. He forgot his shield and sword and was coming at her full tilt, grasping and ungrasping his huge paws. She calmly turned her back on him and started to walk away.

She felt the wind on the back of her neck as he reached out for her. No eye among the bystanders was quick enough to see what followed. Some said she merely stooped and that he dived over her. Others said she tossed him. Whatever she did, Hogni was through for the afternoon. When they turned him over and took stock of his condition, his head lolled indifferently in any direction. That hero broke his neck.

Ida Simpkins had had enough, too, but she did not want to admit it. She was grateful now for Tim Hannigan, the big cop on the beat back home. He used to come into her gym and work out with her, and taught her tricks for some she taught him. But at that, throwing heavy men around is work, and Ida was hard put not to give vent to panting. She tried to walk past the crowd and back to the hall, but they would not have it. They clustered about her, all thoughts of fighting any more that afternoon gone by the board. They wanted to know what the new hero was called, and how she could defeat three of Valhalla's best champions with such seeming ease.

"The name," she said, very precisely, "is Miss Ida."

"Misaeda," they told the ones in the back ranks who might not have heard. "The champion calls herself Misaeda."

To answer the rest called for a speech, and to make a speech she needed wind. For that she needed time. So she asked the nearest huskies to kindly make a pile of handy corpses so she would have a rostrum to address them from. Then she stood back, breathing heavily, while they dragged the bodies up and heaped them, topping them off with a layer of shields that served very well as a floor. She climbed up onto it and motioned them to assemble in front of her. When everything was right, she began.

"You call yourselves heroes. Perhaps you were. You call yourselves champions. That you are not, and I'll tell you why. You don't live right. You gorge yourselves with rich, unbalanced foods, and dim your wits by guzzling liquor. You're fat and flabby and you don't care, because no matter what happens to you, you'll be revived enough to continue with your hoggish stuffing at the next meal. You lack skill, too. Fighters, bah! You're a lot of butchers. You have strength, bad as your present condition is, but you don't know how to use it. I guess that covers it."

She stopped abruptly and started to descend from her macabre rostrum. But they would not let her—just as she had planned. They wanted to know more—how to get in trim, how to fling giants about the way she did. She heard them in grim silence. Yes, she would teach them a lot of things—all but the last. That would be her secret, or at least until her control was established beyond possible challenge.

"All right," she flashed back at them, "if you mean it, get to work! Strip off that armor. Then line up out there in as many ranks as you please, but with room around every man enough to swing his arms and body about without interfering with his neighbor."

She waited while they stripped down to their underwear and got in gym formation, issuing the appropriate orders to correct the formation. When all was set, she started. The Swedish movements she gave them, from A to Z, demonstrating each from her high perch, then calling off the numbers. In half an hour they were sweating profusely. At the end of the hour, nine shamefaced champs lay quietly down and quit, winded and aching in every muscle. But she went relentlessly on, until she caught sight of the Valfather walking across the field accompanied by the faithful Bragi. She allowed them to stop for a rest, and awaited the coming of the all-highest.

"What manner of fighting is this we have today?" he asked mildly, as he came up. "I have seen strange ways of fighting in the world, but never a thing like this."

"Oh. we're not fighting now," she explained, "but getting ready to fight. You see I've got to get the b—"—she bit off the "bums" that came so readily to her lips and substituted "heroes"—"to get the heroes in shape to fight. It may take months. They're in awful condition now, what with lack of exercise, inadequate diet and all."

The Valfather's single eye bulged a bit. What this female hero was saying had the ring of madness. It was astounding. Lack of exercise? Why, his heroes had fought to extinction twice daily for aeons. Inadequate diet? Why, his boys could outeat, and did, any men of comparable weight and occupation in the world. Only giants could exceed them. What was this tiring Brynhild had brought up from earth and Heimdall had passed over the bridge?

"I'll talk to you more about it later," she promised him. "Right now I want to let these men go, and look over the commissary arrangements."

Paying no further heed to the Valfather, she stood up straight again and yelled for attention. The weary warriors struggled to their feet, many cramped from their momentary rest.

"Dismiss!" she said, and started to get down. But they stood staring at her. She turned back. "Dismiss, I said. It's all over for today. Scatter. Rest. Do anything. We'll take the next lesson right after breakfast tomorrow."

Down on the ground, she addressed herself to the Valfather once more.

"I'd like to see the back of the house now, please. Who is the chief cook and bottle washer?"

"Back of the house? Bottle washer? The chief cook is Andhrimnir, but we haven't any of those other things."

"You show me, pop," she said, taking Bragi by the arm. "We ought to be able to give it the once-over before supper, don't you think?"

The venerable Bragi looked startled, but he nodded. So they started back across the field. It was a winding course, for the spent warriors lay everywhere—whole for a change, but more miserable than if they had been hacked in pieces. There was only a second's pain when an ax cleaved an arm away, but reaching for the sky for minutes at a time left aftereffects. But there was not a hero there but was resolved to go on doing it. They were beginning, in a formless sort of way, to hate this Misaeda, but at the outset she had aroused their admiration. Now every man of them wanted to fit himself so he could do the things she had done. And each, as he groveled and panted, looked forward to the day when he could fling people around—beginning with Misaeda.

S in many palaces and the "grand hotels" of earth, the back of the house at Valhalla was as dismal as the recesses of an outmoded penitentiary, in sharp contrast with the gilded exterior. The kitchen was dark, gloomy and dirty, with a bloodstained earthen floor. Innumerable cobwebs hung from the undressed rafters. A huge caldron stood in the middle of the room, and in the far corner a tank of heroic dimensions. The walls were lined with racks to hold the mead-carrying horns, and the stench was terrible. The most obnoxious features of the place, however, were the pigsty and the cook himself.

Andhrimnir was a giant—and an ultra-fat one. He sat dozing on a stool six feet high, but his bulk was so great that his posture was a squat. He had nine chins and five bellies, lying fold upon fold, and his face was coarse and stupid. He was snoring stertorously as Misaeda entered.

In the pigpen—which lacked only grandstands to qualify as a bull ring, so immense was it—stood a colossal boar, surrounded by thralls. One thrall, far larger than the rest, was maneuvering before the pig with a heavy pole-ax. The pig was watching him anxiously with an expression of utter woe, and all the while great tears rolled out of his tiny red eyes and dripped from his snout. Misaeda thought she had never seen so miserable a creature.

"That is Saehrimnir," explained Bragi, proudly. "It is him we eat thrice daily. He has just been magically reassembled from the remains of the dinner. When the thrall kills him, Andhrimnir will awake and thrust him into the pot. It is a very neat and economical arrangement."

"It's outrageous," pronounced Misaeda, looking at the poor animal with rare compassion. "Wait until the S.P.C.A. hears about this. Why, to slaughter the same beast three times a day, day after day, for years and years.... Oooooh!"

She shuddered. There was that angle, of course. But she was also thinking of such collateral issues as monotony of diet—which the drunken heroes never seemed to notice—trichinosis, a constant threat, and vitamin deficiency.

The ax fell, the pig squealed, and Misaeda plugged her ears with her fingers. All slaughtered pigs squeal, but few pigs are of elephantine proportions. Saehrimnir's squeal might well have served as the signal for an air alert for the entire Atlantic coast of America. The cook, Andhrimnir, heard it, even through his deep slumber, and stirred. Misaeda hurried out a side door, dragging Bragi behind her.

There Misaeda saw something that froze her into her customary stance of cool self-possession. Hundreds of weary Valkyries sat on benches that ran along the outer back wall of the palace, waiting for the next mess call. But what caught Misaeda's eye was Brynhild and one other person. They were standing apart, Brynhild and a sly, sneaky-looking, undersized man, whispering together. At Misaeda's sudden and unexpected appearance amongst them, they both looked up, started guiltily, then exchanged knowing glances. The little man smiled a quick, crooked smile, nodded, then disappeared abruptly—much as a light goes out. Brynhild stalked to the nearest bench and sat down, trying to appear indifferent. Misaeda knew, without being told, that the little man was Loki, the Norse god of mischief. There was trouble brewing, and it was being brewed for her. Her immediate disposition of it was a disdainful sniff.

"Now," she said to the fatuous Bragi, "what about this mead stuff? Where does it come from, and how do they handle it?"

"Ah, yes," said he, "the lovely mead. Follow!"

He led her past the seated rows of fagged Valkyries to the place where an open trough entered the kitchen wall. The trough was quite similar to an irrigation or mining flume, and conveyed a gurgling, sticky amber liquid that smelled to high heaven. Valhallic mead, consisting as it does of thirty percent honey, thirty percent pale ale, and forty percent alcohol, would be smelly. The legions of flies blackening the planked sides of the flume did nothing to detract from the general nauseousness of the scene. Now Misaeda understood the big tank that stood in the corner of the kitchen, and why it was relatively easy for the harassed waitresses to satisfy the Gargantuan thirst of the Valhalla warriors. Or Einheriar, as Misaeda had just learned they were collectively called.

She insisted on tracing the flume to its source, so the unwilling Bragi had to trail along. In a couple of minutes they came upon the obvious source of the myriads of flies. Just abaft the kitchen was the golden-wired corral within which the horses of the Valkyrie squadrons were kept. They may have been celestial horses, but they conformed closely in their habits to the earthly and mortal kind.

The trail led on through the golden grove, then upward. At length the gold-leaved trees gave way to green, and she knew that they were in the famous upper bow of the great tree Yggdrasil. It was a forest in itself, with many levels and ramps leading from one to another. She saw many kinds of darting and flying animals, or others placidly browsing—squirrels, eagles, ravens, owls, and stags. But the flume led on, wide open all the way.

At last she found the source. High in the uppermost branches was a filthy platform on which stood a goat, no doubt the goat Heidrun that Skaugul had mentioned. It was a noble animal, if size is any criterion of nobility, for it matched the pig Saehrimnir in dimensions, standing some forty feet from ground to spine. It ate steadily from the leaves of the overhanging bough and its udder continually streamed the fresh-made mead into the trough that it bestrode.

"Why couldn't that animal give milk just as well?" asked Misaeda, with pointed scorn.

"She could. She did," said Bragi. "But who wants milk? We worked magic on her to change it. Neat, eh?"

Misaeda's sniff, to his poetic mind, did not constitute a satisfactory answer. She was unaware of it, and if she had been aware would not have cared a farthing, but at that moment she added one more name to the list of her nonfriends. Miss Simpkins had a way of getting people to do what she wanted them to do, but she lacked the art of making them like it.

"I've seen enough," she announced, having finished a thoroughly disapproving survey of the placid Heidrun.

"Asgard was a dreary place," remarked the innocent Bragi, as they left, "until we had mead. Heavens, you know, are always dull. One has to do something about it after the novelty has worn off. Think of it, I've been here centuries and centuries with nothing to do but sound mess call three times a day and render a ballad now and then on request!"

Misaeda's reply was a super-sniff. Might we say a snort?

UPPER that night was a repetition of dinner. Tons and tons of the unfortunate Saehrimnir's flesh and thousands of gallons of the potent mead vanished. It was accompanied, as before, by millions of cubic feet of belly gases erupted by the contented Einheriar. Altogether, according to Misaeda's lights, it was a most disgusting performance. To her further disapproval, the meal was accompanied by some very flagrant flirtations between the heroes and the willing Valkyries. It appeared that the evening meal, unlike breakfast and dinner, was to be followed by exhibitions of prowess in the field of love rather than in fighting.

"You see, my arm is all right now," said Sigmund, who had seated himself beside her. He demonstrated.

"If it's still there a second from now," she told him, "I'll tie it into a knot with the other one."

He removed the offending arm with a hurt and baffled look. He had certainly tried his best to make this female hero feel at home—offering her a challenge and all that—but everything he did seemed to be wrong. He furrowed his handsome blond brow a moment, then thought of the obvious mot juste.

"Silly of me, wasn't it?" asked the warrior. "One hero trying to make another. Sorry. Naturally, now that we have female heroes, we'll have to have some masculine Valkyries to match."

"Sir!"

And that was the extent of Misaeda's supper conversation. Sigmund hung around for a while, but found it discouraging. When Bragi appeared on the stage for the evening's ballad, he seized the occasion to vanish quietly in the crowd.

Misaeda got through that awful evening somehow. Then some magic was performed. The long troughs and benches disappeared as in a dream. In their places were lines of golden couches. Apparently taps was close at hand.

She picked a couch in the very center of the hall, since, being a hero, she had to sleep there with the others. But for the edification of her neighbors, she most pointedly drew a circle about it with her sandaled toe before she retired. To people steeped in the traditions of potential magic it was sufficient. She did not enlighten them as to what the purpose of the circle was, or what would happen to anyone rash enough to cross it, but the exhibition of the day had been enough for them all.

Morning brought breakfast, and after breakfast came the forenoon of combat time. But that morning the throngs of warriors waited. Their routine had been upset. They simply didn't know what to do. It was Misaeda who told them. Calisthenics again. And she also hinted that those who went easiest on the mead would have the best chance of sticking it out until noon. Because she meant to work them to a frazzle, and did.

All the while, the Valfather sat dejectedly on his throne, contemplating the gloomy future and the puzzling and unprecedented and unpredicted present. He was a sad and disillusioned man, godling, or what you will. He had traded an eye for all-knowledge and wisdom, and had undergone other harrowing experiences in order to make himself more fit as the leader of his people. He knew, or thought he knew, the ultimate culmination of all his efforts. And that culmination was defeat, extinction, and obliteration. Pure tragedy. Nor was there any way out. So the Norns had foretold it: so it would come to pass. It was they who had all knowledge of what had been, what was, and what was to be. Yet at no time had there been mention made of a female hero coming to Valhalla. It was that that troubled him most. Had he given his eye in vain? Were the Norns completely dependable?

Only last evening Loki had come to him. He did not like or trust Loki, but what the fellow had said seemed sound advice. Loki had insinuated that perhaps this female hero who had unaccountably appeared within the walls of sacred Valhalla might be a giant in disguise. How else could one so frail fling heroes about, breaking arms and necks?

So he himself, Wotan, the All-Highest, master of runes and prophecies, had cut runes and studied them. The answer was blank. The woman was no giant, no sorceress—a simple Norse hero cut down while resisting the hated Cimbri. There was no choice left him. He had to follow the advice of the tricky Loki and seek the aid of the reluctant Norns. It was a thing they should have told him, and had not. It was his right and duty to demand an answer. So he sent Loki as the messenger. Loki was due back at any moment.

It was in this manner that things stood when Bragi tinkled his harp and sounded mess call that momentous day. It was in this manner that things stood when the strange hero, Misaeda, and her heaving and flabbergasted disciples staggered off the fighting fields into the grand mess hall of Valhalla. Not one of them, not excepting Misaeda—though she knew dirty work of some stripe was afoot—had any inkling of what was coming.

Before they could sit down. Bragi tinkled his harp and sang out the call to "attention." The panting heroes stiffened where they stood. The tableau on the thronal dais told them something big was about to happen. Loki was there, trying to look self-effacing and unimportant, as was his wont—and Loki's presence always meant trouble. Also the chief Valkyrie was there, Brynhild, looking extremely satisfied with herself and glowing with virtuous triumph. The Valfather was slumped in his throne chair fingering a carved bit of a stick.

After a moment he handed it to Bragi, and commanded, "Read!" Bragi took it, cleared his throat, and began.

"Hark! A message from the wise sisters:

"In Hlidskjalf sits Odin,

His rule is empty.

Misaeda, amongst the Entheriar,

Usurps him.

Wroth are the Dises.

Their sooth unheeded.

"Signed:

"Urdar, Verdandi, Skuld, The Norns."

There was a hush that was painful.

"What say the Einheriar?" asked the bard.

The Einheriar exchanged a lot of sidelong glances, but not one of them saw fit to say anything. They all had visions of fair hands pushing at their throats, twisting their wrists and arms, or other unorthodox contortions that would make them subject to the ridicule of their fellows. No hero cared to stick his neck out. Not one of them opened his trap. Let the gods handle it.

HE Valfather stirred himself. He snapped out of his defeatist lethargy long-enough to get to his feet and declare:

"The self-styled hero, Misaeda, having wormed herself into our midst and violated our hospitality, is hereby expelled from Valhalla. The masters-at-arms will take appropriate measures."

Gunnar and Sigmund, who were the masters-at-arms, exchanged significant looks. It took no clairvoyant to read their meaning. It was simply, "How?"

Misaeda accepted the challenge. From where she stood in the center of the hall she called out in a high, clear voice:

"Fiddlesticks! I've got something to say about this."

Then she stared forward, the armored men clankingly making way for her. They were keenly interested. Scarcely one of them but whose cheeks still burned and ears tingled with some sharp rebuke of the morning. They respected Misaeda, but they would gladly have seen her turned wrong side out. They loathed Loki, the trickster, but they credited him with being smart. They loved their Valfather, but knew he could be thunderous and pompous as all get-out on occasion; and they also knew that Brynhild was nobody to be trifled with. They looked forward with considerable relish to what would happen when Misaeda tangled with that trio.

They had not long to wait. Misaeda was at the foot of the throne. She was mounting the dais! She was up with the big shots, where only gods and demigods dared stand!

"Listen, everybody," she began. "I didn't want to come to this lousy heaven of yours. I'm stuck with it. And it's that dumb woman's fault." Here she flung an accusing finger at the astonished Brynhild.

"She can't distinguish between right-thinking people and your kind. But I'm here, and I mean to make the best of it. Let the old Norns be wroth! What are we here for? To waste our lives in debauchery and stupid dueling, or to prepare for Ragnarok—"

A gasp from tens of thousands of throats in union almost sucked in the walls. Ragnarok, the unmentionable, shouted from the platform! It was hideous; it was blasphemous; it was unthinkable. All the world knew about Ragnarok and dreaded it, but never spoke of it. The ultimate fate of the world was the most hush-hush thing imaginable. Nobody was supposed to know it but the Valfather, Mimir, and the Norns. And all mankind, and godkind, and giantkind, and dwarf and fairykind joined in the conspiracy. If the good and kindly old man who was their chief god chose to kid himself that only he knew the future, they would not disillusion him.

The Valfather's lone eye bugged.

"Did you say Ragnarok, my child?" he asked anxiously. "Are you, perchance, a fourth Norn, that you know the unknowable?"

"Do I look like one of those crack-brained old women?" she countered. "Why do you have to be a Norn to know what everybody knows and has always known? This cockeyed set-up you have here is headed straight for a fall, and it's no secret, but you sit here day after day mooning about it and grieving over what you think can't be helped. Well, I'm not usurping anything. I'm trying to help you, that's all. If you expect to make any showing at all at Ragnarok, we'll have to get this bunch of bums in better condition. They are fat and flabby, and their kidneys are all shot from swilling mead ... oh, my, they're terrible!"

The Valfather's single eye was roaming the sea of upturned, eager faces. He did not like in the least the turn the conversation had taken. Cats were being let out of the bag by droves. And, to his amazement, the assembled throng of heroes took the nasty reference to them with meek silence. If this woman kept on talking, it was hard to say what would come out next.

"Suppose we adjourn this hearing to my chambers, my dear," suggested he, solicitously. "It must be trying to talk before so many."

"Very well," Misaeda snapped back, "but that rat"—indicating the fawning Loki by a contemptuous jerk of the thumb—"and that cat"—meaning the indignant Head Valkyrie—"don't sit in. I've got things to tell you for your own good."

The Valfather winced. Sometimes Frigga talked like that, too. He knew from a wealth of experience that whatever was for his own good was going to be hard to take. He sighed audibly. Women were like that, though, and you had to make the best of them.

"This way, my dear," he said resignedly. Then, turning to Bragi, "Tell 'em to sit down and eat. We'll put out a release later."

In the interview in the chambers—which were the usual barnlike rooms Misaeda had observed elsewhere in Valhalla, palatial only because of the vast areas of gilding—the ex-headmistress of the Gowanus Settlement School did not pull her punches.

"Are you going to be a sap all your life?" she began, with her customary disregard for tact. "You're all tied up in knots in the silliest, most impractical mythology ever invented by drunken poets. And all you do about it is sit and suffer. Or else you go off the reservation entirely and squander months down in Midgard breaking up families and impairing the morals of minors. Do you think it's right?"

She spoke with a bitter fierceness that drove him straightway into the corner. He was on the defensive from the first onset.

"Wh-wh—"

"No. Of course you don't. You're a decent guy—at heart. But you're too darn gullible. You believe you've got to do these things because they're in the book. Nuts! If you set yourself up as chief god in this wacky world, why don't you work at it? Do something."

She paused for breath, glaring at him with open disapproval. He floundered for a moment and managed a weak, "But what can I do?" when she was back at him.

"What can you do? Plenty! You swapped an eye for knowledge that everybody has. Go back and get your eye and tell old Mimir to go and jump in his own ocean. You keep fooling around on the advice of three crazy old women who are doing their best to make a monkey out of you—and succeeding. Bosh! I know as much about the future or anything else as they do. You are worrying about the giants, and the dog Garm and the wolf Fenris. Well, I ask you. What has Garm and Fenris got that is so terrible? Bad breath—halitosis, they called it in my age. Get yourself a gas mask, that's all there is to that. And you're worried about the dragon Nidhug that is gnawing at the roots of Yggdrasil. Why don't you kill it now, while the killing is good? Why wait until they all gang up on you? Snap these heroes out of their chronic jag, and swat the frost giants. Swat the fire giants. Send expeditions everywhere, one at a time. Then you'll have no Ragnarok."

"But, my dear," protested the harassed Valfather, "you don't understand. Ragnarok is far in the future. There is nothing we can do about it now. We have peace. Don't you understand? If we do the things you urge, we upset the status quo. That is always bad."

"Nuts. Excuse my frankness, but I seem to remember a gentleman hight Chamberlain. He talked like you did—of 'peace in our time.' There was another, somewhat before him, who said, 'After me the deluge.' That's you, on both counts. I ask you again, are you going to be a dope all your life?"

The Valfather was much distressed. Nobody had ever talked to him like that—not even Frigga, in her most uninhibited moments. One of the tremendous advantages of the godhead was the immunity to unmasked opinion. His satellites had always been Yes-men, and there was no denying it—he liked it. He must get rid of this troublesome female hero, with her sharp tongue and utter lack of respect of authority. He had the fleeting idea of summoning Brynhild and having her take this Misaeda back to where she had found her and dump her in the ocean. He stammeringly mentioned it.

"Not a chance," was Misaeda's tart reply. "Your stupid, bungling system wished me on you, and I stick. You've hauled me back a couple of millennia and there is no place for me to go. But if I can't have the Christian Heaven I'm entitled to, I'll do what I can with this one—on a give-and-take basis. I'll help you, you help me. Between us, we can make Valhalla a decent place to live. As for Ragnarok—that's in the bag."

Wotan tried to digest that. For he had never had much use for women except in a limited sense, and all she had said was rank heresy. Try as they might, the Aesir could not hope to survive Ragnarok. It was so written in the sacred runes. It had been foretold by the Norns. Mimir had confirmed it. Wotan himself knew it from the prescience he had so dearly bought. This Misaeda talked sheer sophistry. Yet she talked it with such an air of determined confidence that his own self-confidence was shaken. Perhaps in a case like this compromise was in order.

"My dear," he said, after a lengthy communing with his own thoughts, "I have reconsidered my expulsion order. I believe you are truly a hero from Midgard. As such, I shall let you remain in Valhalla. More than that, since you appear to have practical ideas, I shall make you chief of the Einheriar. Handle them as you will—with Ragnarok in mind. But not a word of that to them, do you hear?"

"I hear," she acknowledged grimly. The fable of the Camel in the Tent was not far from her mind. First a foothold, then control. What more could a sincere, ambitious girl ask? Well, a few things. And she asked for them.

"Very well," she added. "I'll do it. But I need a little help."

"Ask it."

"I want," she began, "first of all, that when we eat this hog Saehrimnir next, that he'll stay eaten. Get me? After that, I want herds of cattle, flocks of chickens, and some sheep. Get Mimir to furnish fish twice a week—he has plenty, and the Einheriar need variety."

The Valfather nodded approval. But he hadn't heard the half of it.

"I want," she continued, "ten thousand thralls with oxen and plows to turn up the south recreation pasture. I need only the north one for my exercises and drills. After that I want it planted in vegetables. I want cabbages, spinach and potatoes. I want asparagus, lettuce, radishes and artichokes. I want onions. Garlic. Corn and wheat."

"It's a big order," murmured the All-Highest. "Moreover, the heroes won't eat that stuff. I know 'em."

"They'll eat it," she assured him, with a stabbing glance of those steely gray eyes, "and like it. I'll guarantee it."

"All right," sighed the Valfather. "Go on."

"I want that fat cook fired ... the kitchen thoroughly cleaned and painted white inside—not gold ... and that mead-producing goat turned back into a normal goat—"

"But, my dear, the heroes will not drink milk—"

"They will drink milk," affirmed Misaeda, determinedly. "But not in such quantities as they have been drinking mead. That calls for cheesemakers. Which brings up another item. Send a squadron of Valkyries down to Midgard and have them pick out a few score deserving housewives, instead of swashbuckling killers, for a change. What we need up here is homemakers—not these floozies you hire as body snatchers."

"Floozies?" queried the Valfather, wrinkling his noble brow.

"Hussies, if you like the word better. That's all half these Valkyries are. What goes on here after dinner at nights is simply scandalous, no less. I won't have it."

By then Wotan was in such a state of confusion that he could only nod acceptance. Inwardly he was cursing the Norns for not having let him in on this thing in advance and told him what to do. He was a simple, primitive war god, and not versed in the technicalities that now confronted him.

"What else?" he asked meekly.

"I guess that's all for now," said Misaeda, relenting. She knew just how far to push a thing on a single interview. She had learned that with countless contacts with high-school board officials. Up here in Asgard she had all Eternity in which to work. What could not be done today could be done tomorrow.

The Valfather bowed her out. She marched by him primly, out onto the platform, and down the steps to the floor of the hall. The meal was over, as she well knew from the chorus of burps and the clicking of toothpicking. But she stalked to her seat, nevertheless, and sat down as if nothing out of the way had happened.

"I saved some chow for you," whispered Sigmund, leaning over and opening his tunic. Underneath his sweaty shirt was a side of ribs, greasy and underdone, but still warm.

"Thanks," said Misaeda, laconically, taking it and pretending to nibble. She was fed up with pork, but in her own peculiar way she was gratified. At least one of the heroic dead was showing symptoms of incipient good manners.

HAT night Misaeda lay on her golden couch—within the magic ring—and thought and thought. So far, so good. In a day or so she would introduce a balanced diet; her system of calisthenics was already doing marvels. Next would come the business of teaching the defunct heroes table manners; the matter of appointing corporals and sergeants and the teaching of squads right and similar basic maneuvers. After that the Blitzkrieg tactics.

Then an errant breeze wafted to her the odor of ten thousand spent warriors lying on the weather side of her. Oh, yes. There must be showers, too, and some arrangement about laundry.

Misaeda sighed. A woman's work is never done, she told herself for the nth time. These poor, poor men—so helpless, so goofy. It was lucky for them she had come amongst them! Tomorrow there would be much to do. She was so ecstatic in her previsions that she did not note or even hear the somnolent mutterings of the hero on the next couch.

"Ah, god," he moaned, "Misaeda! What next?"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.