RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

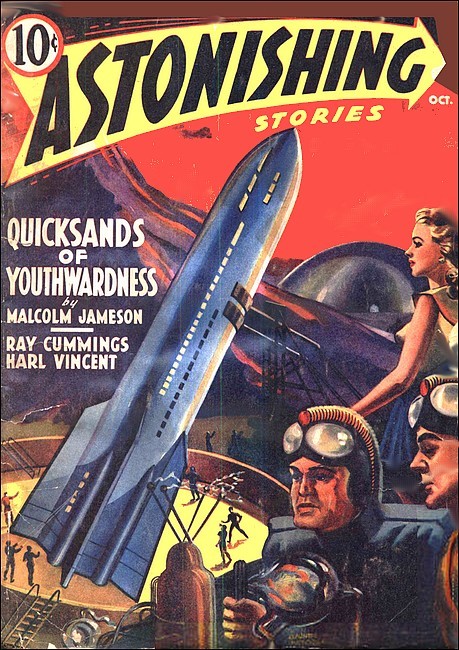

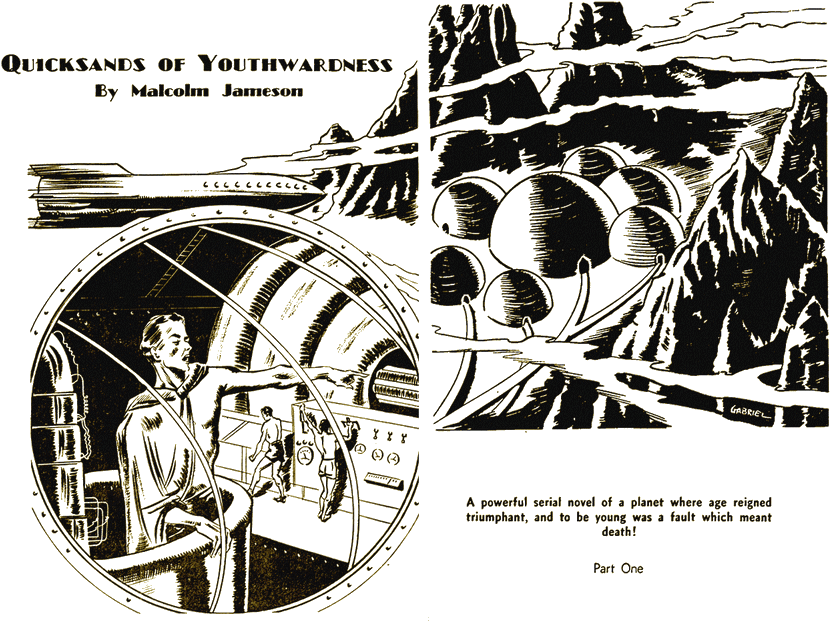

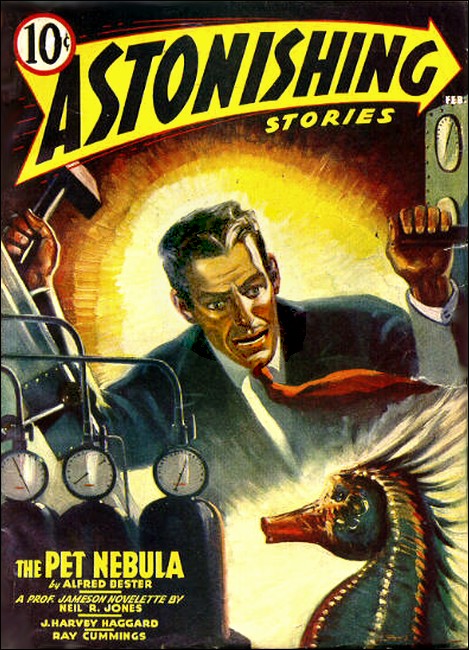

Astonishing Stories, October 1940, with first part of "Quicksands Of Youthwardness"

HIS face set in lines as grim as granite, stocky old Captain Yphon sat slumped, strapped fast in the master control chair of the dizzily-falling Thuban. Not once did his tired old eyes stray from the congested rows of gauges and indicators before him. There was no need of their wandering elsewhere, for every port and outlet was double-shuttered and screened against the beating rays of Sirius.

Except for the tough instruments that measured the invisible but all-pervading lines of magnetic force, the ship was blind. Long since that fierce radiation had vaporized the subchromatic plates in Ulberson's special cameras, hooded though they were in protective turrets overhead. Cameras and periscopes alike had collapsed, their molten lenses dribbling away to spread like so much honey over the plates of the hull.

It was the gravimeter gauges that caused Yphon grave concern. For seconds now their telltale gongs had been tapping ominously—clamoring for attention. The reading of Absolute Field Strength was bad, unbelievably bad—double that against which the ship had been designed to operate. But far worse, the needle indicating the rate of acceleration was quivering hard against its final stop-pin. The situation had passed being dangerous. It was desperate.

Captain Yphon, without turning his head, called quietly,

"Mr. Ronny. Step here please—quickly."

The haggard chief engineer stumbled the few feet from his station and presented himself at the Captain's side. The Captain did not speak at once. He was still scanning the warning instruments. Before issuing his drastic order, he must be very sure.

In that brief moment of hesitation, the other men in the room turned their heads toward him, dully anxious to catch the words of hope. There were Sid Daxon, the lanky Mate, clinging by straps to the control board, flanked by his four helpers. Beyond were Ronny's men, another four, each tending a segment of the intricate switchboard. In the background the ship's surgeon, the efficient and friendly Dr. Elgar, hung to a stanchion with one hand while he strove with the other to safeguard a trayful of hypodermics filled with the potent Angram Solution, that blessed specific against the tetany of excessive gravity.

Profusely sweating and with startling eyes, panting laboriously, they awaited the Captain's decision. Absent only was Ulberson—the great Ulberson, explorer—at whose insistence they had approached so close to Sirius. He lay in another room, whimpering in his bunk, imploring the air. "Somebody do something, do something," was the refrain. But he was unheard, or if heard, disregarded. Those others were too busy doing that something. For those frantic-appearing men in the control room were not frightened. Not one of them knew the meaning of the word "fear." Their harried, anxious looks were due solely to the uncontrollable reflexes of straining muscles and tortured glands.

"Ronny," said the Captain, "throw in your reserves—all of them. Cut over the auxiliaries—except the air-pump, we can't spare that. Everything, mind you, to the last erg—even the lights."

"Aye, aye, sir," gasped Ronny. Then hesitantly he added, "for your information, sir, the Kinetogen is already carrying a hundred per cent overload. It'll blow, sure as hell."

"We'll blow, then," was all the Captain said, still looking at his meters. Better to be blasted than to be slowly crushed and roasted with it, was his thought, but he saw no need to voice it.

Ronny made a gesture to his men at the board, knowing they had heard and understood. Swiftly, silently, they pulled open switches—closed others. Warning buzzers sounded in the after corridors and passages of the ship. Men braced themselves for the inevitable shock. Ronny himself was back at the board by the time the change-over was complete. He grasped the main feed lever—pushed it firmly shut.

Abruptly the lights went out. Like dumb ghosts in the stifling room lit only by the eerie glow of the tiny battery-fed lamps on the indicator panels, the sufferers waited. The hull trembled more, and then yet more, as increment after increment of powerful counterthrust was hurled out against the greedy grasp of Sirius. Even through the many feet of passages and the several safety doors that separated the engine room from them, they could hear the whine of the excited Kinetogen rising to a wild scream and feel it quiver, tearing at its bedplate.

"Thank you Ronny," came the Captain's steady voice, "if she'll hang together ten minutes we'll be all right."

Neither Ronny nor anyone else in the room believed the Kinetogen could stand up two minutes, let alone ten. Nor did they think ten half enough, but they were grateful to the Captain for saying so. No one responded. There was nothing to say. They could only wait.

The vibration worsened, and throughout the room, matching the terrible crescendo of the runaway Kinetogen, rose an answering chattering chorus as metal screws, loose papers, furniture, everything joined the mad dance.

Except for their heavy breathing, the throbbing, oppressed humans made no sound. Then, in a momentary lull in the wild cacophony of the hurtling ship's internal noises, as it rested, so to speak, before swelling into yet louder howls, a muffled wail penetrated to the control room. It came from the passage leading to the sleeping rooms, and plaintively stated a grievance. "My lights are out—send a man."

Daxon struggled with his safety belt, freed himself. He staggered through the darkness until he found the passage door, slammed it shut and leaned against it. "What we can't help, we have to take," he muttered through clenched teeth, "but by G...."

It was merciful in its abruptness. No one could know certainly when it happened or how. The Kinetogen, secluded in its wholly mechanical, remote controlled engine room, did all it could, and being a mere machine, could do no more. It blew up.

SID DAXON became vaguely conscious. It was utter dark and the

heavy air was foul with the fumes of volatilized metals. And it

was hot—terribly hot. He eased a limp human form off his

pinned legs and passed a trembling hand over his face and head.

Hair? Yes. Hair yet, nose, eyes—everything. Stiffly he

rolled over and managed to move a little on his hands and knees.

Crawling, he groped about the floor plates trying to orient

himself. He encountered other bodies there, scattered about, and

felt of them, listening. They were alive, all of them!

In time, he attained the pedestal of the master control chair. A swift exploration with cautious hands told him Captain Yphon lived, too, still firmly lashed to his post of duty. Now he remembered that in the base of the indicator panel stand there was a little locker. In there should be some portable hand-lamps. He fumbled the smooth face of the door until he had it open. They were there—he had a light!

Before he made any attempt to arouse the others, he flashed the light across the faces of the gauges. As was to be expected, the engine room indicators were dead. There could be nothing left back there. But impulses from the outside void were still being received, appraised and reported. The gravimeters showed a field force of nearly zero, and that diminishing. They must be going away from Sirius at a stupendous pace—must already be a long way away! A glance at the ray-sorters and the spectograph confirmed it. That one desperate effort, the dumping of all their power concentrated into one colossal dose, had done the trick. They were free.

He found Dr. Elgar face down among the litter of his overturned tray and shattered tubes. He must wake Elgar first. He was the one who would know best what to do with the force-stunned victims. Furthermore, Elgar was his buddy—they made their liberties together whenever they hit a good planet.

In a moment. Dr. Elgar gasped and regained his senses. One by one, they revived the others, last of all the Captain. Other than simple bruises or cuts acquired in falling, none was hurt.

In a short while, Ronny found the breaks in the emergency lighting circuit and had a few dim lights burning forward. As soon as he was unstrapped, stiff with age though he was and cramped from the untold hours spent tied to the hard saddle, Captain Yphon proceeded at once to the inspection of the damaged Thuban. His officers led the way, lighting the path with their hand lamps.

The wreckage of the engine room was complete. The inner bulkheads were torn and twisted like crumpled paper, and the intermediate ones pierced in many places by the hurtling splinters of the gigantic Kinetogen, but nowhere had the hull been breached. Ronny looked at the scattered fragments of his great force engine with a wry face. The auxiliaries he could repair or replace from the spare stores, but there was nothing to be done about their motive power unless somehow they could make a planetfall. And even if that unlikely feat could be accomplished, it would have to be on a civilized planet—a rare body in these parts.

Coldly and with a stern face, Captain Yphon took stock of the situation. When he had seen it all and realized how helpless they were, he slowly removed his glasses, and meticulously wiping them, said simply,

"I'm glad nobody was hurt. You are all good boys and behaved well." He screwed up his bulldog face and spat, "But that bout with Sirius was only a skirmish—now the fun begins."

In the first relief at finding themselves living and their ship intact, the last remark did not weigh heavily on the Thuban's personnel. Anyhow, in the space-ways the motto "One thing at a time" is the only tolerable rule of life. They had got out of one jam, they would get out of the next.

All hands turned to cleaning up the wreckage aft and repairing the punctured and riven bulkheads. There were warped doors to straighten and rehang, ruptured pipe and severed conduit to underrun and replace, and much else. As to the Kinetogen, there was nothing could be done about it except to sweep its parts together and stack them in bins, out of the way. In the meantime, the Thuban, with whatever residual velocity she had when she escaped the greedy embrace of the Dog Star, was drifting through space.

Observing the serene resumption of the routine, Ulberson, the charterer and nominal head of the expedition, easily regained his composure. "I knew you could pull out of there—I shouldn't have advised going in otherwise," he said blandly to Captain Yphon. "Too bad I lost my cameras. And it was too bad somebody got panicky and wrecked the main."

"Mr. Ulberson," the Captain made not the least effort to conceal his disgust, "if and when we return to Earth, you are at liberty to make any charges you choose in regard to my handling of this vessel. In the meantime, I have resumed full command. Hereafter, you will be treated as a passenger, and as such I must ask you to refrain from interfering with my crew."

As the Captain stalked out of the room, Ulberson began to sputter, but glimpsing the unsympathetic faces about him, he changed it to an airy whistle and sauntered away to his own room. Ulberson was one of those people who thought of himself as a "star," an attitude that received scant respect from the tough old skipper of the Thuban. Old Yphon's ideal was teamwork. On his ships it was "One for all, all for one." There was no place in his scheme of things for the solo performer.

ANOTHER day came when Captain Yphon sat in the master control chair and gazed forward with set face and a hint of anxiety in his eyes. This time the screens were down and the ports uncovered. Ahead lay the incomparably beautiful velvety black of the void with its untold billions of sparkling points of light. Far to the left were three cloudy patches —nebulae—gorgeously tinted in reds, greens and yellows, one of them studied with faintly glowing globules where its condensing gases were forming new flaming suns.

Those colorful nebulae, attractive enough to tourists' eyes, were not what fixed the attention of the Captain. It was the black spot dead ahead, that hole in the sky that kept on growing, eating the stars as it spread. In there was no color, not any. A month before it had been but a few degrees wide, now it was sixty —and growing. Its edge was marked by an irregular circle of ruddy stars, obliterated one by one as the Thuban approached. Yphon had been watching the occultation of those stars for many days. Always they would twinkle awhile, at first, then redden, to fade away finally to nothing as the great globular nebulae swelled up before them.

The Thuban was out of control—there was no blinking that fact. Propelled by the titanic kick of the expiring Kinetogen, she was hurtling onward at terrific speed, and must go on so forever, or until some impeding sun laid its gravitational tentacles on her and dragged her in to fiery destruction or else imprisoned her in an endless orbit. That murk before them could not be evaded, no matter what its nature. They must dive on into it and face what lay there.

IN the control room behind, Yphon could hear the drone of a

voice reading. It was Daxon, and the volume he held was that one

of the "Space-pilot and Astragator" for this quadrant of the

celestial hemisphere. The section he was reading dealt with the

supposed nature of the dark nebula ahead, as compiled from

reports of earlier voyagers. Elgar, Ronny and Ulberson sat in

various attitudes about the chart table, listening.

When Daxon came to the end of it, he tossed the book to the table.

"It's tough—but now you know what we're up against," he shrugged. "No ship that ever went into the middle of that was ever seen again. A few cut through near the edge and came out on the other side, all right, but the people in them didn't know what it was all about—they couldn't remember—not anything, either going in, or what it was like on the inside."

"So they went home and wrote accounts of it," sniffed Ulberson, with a trace of his characteristic supercilious smile.

Daxon, nettled, shot him a hard look, but for the benefit of the others, replied.

"Yes—and why not?" he snapped. "The dope was in their logs, entries showing when they sighted the cloud, their approach, the moment of entering—all about it. The chronometers and the other instruments kept on recording and there were all their cards, complete. It was only the human mind that failed. They remembered, some of them, seeing the cloud far ahead, and then, like a flash, it was just astern of them. When they were convinced of the lapse of time and saw their own handwritings in the logs, they knew their consciousness had played some kind of trick on them. They must have done all the usual things as they went along, yet none of it registered on their memories. It was something like being under an anaesthetic, I guess."

"So that's why they call it Amnesion?" remarked Dr. Elgar, in mock cheerfulness. "Fog of Forgetfulness—poetic, eh?"

"If you've got that kind of mind," admitted Daxon, with a quick grin. "But don't forget, it's near the center of that thing we're headed for, not the edge, and it's about as far through as our solar system is wide. If a touch of it wipes out all you've learned for months, were apt to be pretty doggone ignorant when we come out on the other side, if we come out."

"Must be a property of the gas," speculated Elgar, more seriously, "or--"

"Or rays," interposed the Captain, still staring ahead. "Mr. Daxon! Kindly have all outward openings closed off with ray- shields and rig the spare periscope. I don't like the looks of things ahead."

While the crew were scrambling to carry out the order, Dr. Elgar picked up the book thrown aside by Daxon. He thumbed through it to the chapter on Amnesion and read it for himself, footnotes and all. Among the lost were the Night Dragon and the Star Dust, carrying more than a thousand passengers each —two of Rangimon's transports with whole families bound for Tellunova in Hydra. Then, a few decades later, about 2306, Sigrey took his Procyon in there with a relief expedition, but failed to return. In subsequent centuries several small freighters disappeared in the vicinity and were thought to have been swallowed up by the nebula.

ULBERSON, annoyed at the ill-concealed contempt of these

hardboiled spacemen, felt he must make some gesture to

reestablish his prestige.

"A bit of luck, I'd say. Since they make such a mystery of a little black gas, it may be worth looking into. As long as we're here, I might as well solve their puzzle for them." He yawned elaborately, as if getting at it was all there was to it.

"Oh, by all means," said Elgar, amiably, and threw a wink to Daxon, who had wheeled angrily at Ulberson's words, "if you can manage it. As for myself, speaking as a medical man, I anticipate some difficulties. Explorers may be above such considerations, but I was just thinking how astonished I am going to be, say, to observe the effects of some drug I've given, having forgotten that I gave it, or what for. It is the sort of thing that is likely to make the practice of medicine uncertain. Given time, I daresay, I may develop a technique along those lines, but at the moment it looks to me as if trying to live with memory not functioning is as foggy a proposition as that smoky cloud itself."'

Ulberson glared at him, faintly suspicious that Elgar was pulling his leg, but the doctor's face was a study in innocent seriousness. Then, as the full import of what had just been said began to dawn on him, Ulberson's self-assurance sagged a little. He had braved the perils of cold on dim lit planets, and fought their bizarre fauna, but never under the handicap of amnesia. What Elgar seemed to envisage was not the forgetting of things far past, but of things in the happening—the occurrences of a few minutes ago—an instant ago!

Ulberson twisted uneasily in his chair. The implications were not pleasant. Why, that might mean that he could not retain the memory of what he started out to do he might wander around aimlessly, like an imbecile observing things, to be sure, but without linkage to their causes and then forgetting observations in the very moment of making them. That would be a horrible situation—unthinkable—intolerable.

Captain Yphon, having overheard, chuckled savagely within himself. "You hired us, my fine bucko," was his grim thought, "to take you into the Great Unknown. Well, by God, you'll get your money's worth."

IN another week the whole sky ahead was devoid of light. Lacking any reflective power, the great nebula did not appear the gaseous sphere they knew it to he. It was rather a circular emptiness in the heavens, bordered by the ever-widening ring of reddish stars that shone unsteadily on its misty circumference in the brief interval before their final extinction.

Daxon maintained a close vigil at the instrument panel. Gravity was beginning to be registered again, though lightly. The photometer indicator crawled slowly—yet rays of terrific intensity impinging on the ray-detectors—and what rays! If they did fall beyond the range of the sorters, they must be of wave shapes and frequencies unheard of—theoretically nonexistent, impossible.

Dr. Elgar stood there, too, keenly interested. Whatever the emanations of the inky fog, he wanted to see and weigh them. Since steeping himself in the accounts of Amnesion, he had been alert for any symptom of forgetfulness, but as yet there had been no evidence of amnesia within the Thuban. Everybody had been instructed to keep a minute diary, and every day scraps from them were picked at random and read to their writers. If there was forgetting, it was of so subtle a type that neither victim nor physician could detect it, although Elgar was not unaware that the seeming ability to remember might itself be an illusion. Yet it might be, since they were forewarned and the ship made tight against gases and so well screened that no ray, unless of some unknown hull-piercing type, could enter, that they could pass through the cloud with immunity.

"We must be well inside now," said the Captain, when he saw the gauges, "I'll take a look around and see how dense this nebula really is." He laid aside his glasses and seized the guiding bar of the periscope, intently watched by Dr. Elgar. If the peril lay in the rays, they might enter through the eye-piece of the periscope, and magnified by it to what would surely be a dangerous intensity at that.

Captain Yphon swung his gaze first astern, where the mist would be its thinnest. If stars could still be seen, it would be there. "All black," he said, in a matter-of-fact tone, and began to swing forward, scanning as he went. "Not a glimmer anywhere," he added, his left eye squeezed shut as he squinted with his right, "except there is a queer greenish luminosity on the hull—faint, like from a glow-worm. I can only see it for about ten yards, then it fades out."

As he spoke, a tiny glint of clear violet light began dancing on the surface of his staring eyeball. The astounded Dr. Elgar saw it brighten, then flare out into a semblance of flame—feathery sheaves of dazzling violet rays, jumping from the Captain's eye into the periscope like the flame of an arc. "Still dark," the Captain was saying, in the same ordinary tone, swinging the periscope from dead ahead on toward the port beam.

Elgar laid a restraining hand on Daxon, who was springing forward with the impulse to drag the Captain away from the periscope. "We must know," he whispered. "It doesn't seem to hurt him—he doesn't even suspect it."

Captain Yphon relinquished the periscope and picked up his glasses. He put them on and made an effort to adjust them, then snatched them off disgustedly. "What the Hell," he growled, "the right lens has gone opaque—I can't see a thing."

"Let me look at your eye," ordered Elgar, gently, "because nothing has happened to your lens."

The Captain turned full toward him, amazement on his usually composed features, opening and shutting his eyes alternately and looking dazedly about the control room. Elgar halted him and peered into his face. The left eye was normal, the dull, faded, yellowed eye of age. But the other! The right eye glowed with the soft warmth of youth. Its cornea gleamed with the firm smooth whiteness of the very young; the crystalline lens was finely transparent; the iris magnificently colored. Hastily Elgar tested it for its visual qualities. It was perfect—according to the standard for a boy of twenty!

"Captain," he said, huskily, for he felt the weight of his responsibility. "Look through the periscope again, but with the left eye this time."

"The periscope?" echoed the Captain, vaguely, "Yes, yes—we must be well inside now. I must look around and see how dense it is."

ELGAR and Daxon exchanged significant glances. Yphon had forgotten having been at the periscope, yet he had been looking through it for a full seven minutes. The amnesia of the nebula was not a myth, and that reversed ray seemed to be its avenue of infection.

Again the Captain put his eye to the periscope and again there was the strange play of violet light from the eyeball. Daxon and Elgar stood close on either side and watched its dancing brilliance. It was unreal, immaterial, like the fire from a diamond manipulated in strong light. Spectacular though the display was, Yphon appeared unaware of it. He went on as before, making an occasional calm remark about the gloom outside. When the seven minutes were up, Elgar grasped him by the shoulders and pulled him away from the eye-piece.

"What's wrong? Why did you interrupt me, doctor?" demanded the Captain, "somebody hurt?"

Earnestly staring at the doctor from beneath shaggy white eyebrows and imbedded in the wrinkled, baggy pouches of an old, old man, were two vibrant, piercing eyes, the eyes of a strong- minded, vigorous adolescent. There was something almost terrifying in its incongruousness. Elgar's judgment had been confirmed, practically, but the fundamentals of the mystery were as elusive as ever.

"How do you see?" inquired Elgar, shakily. The Captain brushed his face with his hand, looked about him, then picked up a table of haversines and examined its tiny agate type. "Why, why, fine-- better than I have in years better than I can remember ever seeing."

Dr. Elgar's relief was immense, but he saw potential danger. "Sir," he urged, "You must not use the periscope any more, nor anybody else, unless through a strong filter and under my supervision. The rays of Amnesion do effect forgetfulness, and apparently rejuvenation as well. It may not be prudent to overdo it."

It was with some difficulty that the two younger officers convinced Yphon of his lapse of memory. By careful questioning they established that as far as his time sense was concerned, he had lost nearly an hour. It was not only that he failed to remember what had passed while he was at the periscope, but it was as if during the same time his previously stored memories began to unravel, unwind, as it were, and vanish.

After that the periscope was sparingly used, and then with filters. There was not much need of it, for outside nothing could be seen except the eerie fire-fly glow of the hull, ghostly in the smoky fog. Once, Elgar induced old Angus, the steward, to expose both his eyes for a brief period to the unfiltered rays, but otherwise the phenomenon of the eye-flame was not observed again. Angus, who was quite as old as the Captain, had begun to develop cataracts, and as in the case of the Captain, a few minutes of exposure had distinctly beneficial results. And like the Captain, Angus had to be told of the experience afterward, and of what had immediately preceded it.

ELGAR pondered the remarkable therapeutic power of the queer

rays, dealing amnesia and rejuvenation with an equal hand. There

was a connection, he did not doubt. He was beginning to formulate

a theory, but that theory, although logical, was counter to all

experience.

He knew that under the stimulus of light, living cells sometimes altered themselves, that light provoked chemical action—and, as in fireflies and the phosphorescent organisms of the sea, cells sometimes produced light. But in his experience, the cells of the human body did not produce light, and the changes produced by metabolism were invariably in the direction of greater specialization, the simple to the intricate—towards senility, in other words—and that that process was irreversible. Normally, a? the cells become more and more specialized, they end by losing their adaptability, and old age and eventually death ensue. Gerocomists, he knew, could sometimes retard those changes, but never arrest them, let alone reverse them.

Yet he had just seen it done—twice. And although the rays seemed to originate within the eyes, obviously the stimulus came from the nebular gas about, with its curious, invisible rays. Could it be that that black fog had unique refractive powers that twisted the light it so completely absorbed into inverted, even negative forms? Was its absorptive power so great that it reached out, so to speak, and pulled light into itself?

And if so, did the living 'cell, under the compulsion of giving back the light it had hitherto absorbed, readjust its structure to the simpler form it used to have? If so, the structures would appear younger. Perhaps it was the simplification of the cortex of the brain that caused the memories stored there to vanish. There was no precedent in physiology or mathematics for such assumptions, but neither was there a precedent for the amazing ocular rejuvenation he had twice witnessed.

Those other ships had plunged in here, unsuspecting, and therefore unprepared. Once in the grip of the amnesiac rays, they would be helpless, for they could not reason, since reason is a cumulative process. And equally as they forgot, did they grow younger? Under unlimited pressure in that direction, how far would they go?

Dr. Elgar saw no way to approach the answers to those questions without assuming unwarranted risks. At least so far, the Thubanites appeared to be effectively insulated from the outside, and it would be reckless to invite forces within that were so unpredictable in their action.

FOR many months they plunged on through gloom- enshrouded space, guessing at their progress by dead reckoning. Yphon and Daxon had computed their most probable path. Allowing for some deceleration due to the friction of the enveloping gas, there were indications that they might have enough momentum to escape the nucleus, as their trajectory would pass about one- third of the way between it and the periphery of the nebula. There had been a steady increase in the gravity readings, but the total force indicated was not alarming. They might eventually escape the cloud entirely and emerge once more into the outer void.

This was not as heartening a hope as it might have been under other circumstances, for Ronny had reported that in spite of reclamation, there was less than a year's supply of oxygen left, and old Angus had already begun rationing out the food. Beyond Amnesion were many parsecs of empty space. Escape to it meant only the hollow advantage of dying outside in the clean clearness of inter-stellar vacuum, rather than in the depths of the dirty black mist.

Occasionally Daxon would sweep the darkness with the periscope. It had always been utter night outside, but one day he felt a thrill of surprise as he noted an unmistakable lightening of the gloom. Broad on the starboard bow, widely diffused but clearly distinguishable, was a lurid crimson glow. Hour by hour the red increased in intensity and lightened in hue, until in time it looked as if all that part of the universe to starboard was in vast conflagration, half-smothered under a pal! of smoke. Then the black mists seemed to be clearing, as a terrestrial fog lifts, and the initial glow came to be a well-defined circular patch of intense orange light which in a little while revealed its source—a sun! Here at the center of the globular nebula was a fiery yellow sun, lying unsuspected within the opaque shell of absorbent gases.

Once more the instruments recorded normal, positive light, and the spectrum of the inner sun proved to be much like that of Sol, except that it was somewhat richer in the violet band. Quick tests showed there was no further need of the elaborate system of screens. The bizarre properties of the nebular system were apparently to be encountered only in its outer husk.

But although they were no longer in the fog and were in the presence of a normal sun, their-surroundings were no less uncanny. In place of the black backdrop of space, spangled with its myriads of glittering stars and glowing nebulae, everywhere was a dull, angry, smoky red. The starless heavens of inner Amnesion resembled the interior of some cosmic furnace. Either because the inner layers lacked the absorptive powers of the outer, or were saturated by reason of their proximity to the sun, they dully reflected a ruddy glare that gave the whole region the appearance of an inferno.

Puzzled over the existence of such an open space in the heart of the nebula, for Daxon had supposed its density would increase as they neared the nucleus, he asked the Captain about it.

"Young man," said the Captain, turning his strangely youthful, burning eyes on the Mate, "when you are as old as I am and have wandered as widely in the southern void, you'll accept things as you find them. But since you want an explanation, you are welcome to my guess.

"Presumably that sun represents the condensation of what formerly occupied this space. After it became so compact that it was forced to radiate, its light pressure naturally forced the outer gases back. Those gases, caught between two forces—light pressure pushing out and gravity pulling in—necessarily were compressed, as we have seen, into a sort of shell, like the hull of a walnut, if you can think of stuff as thin as that in solid terms."

The old man grunted, and there was just the suggestion of a twinkle in his boyish eyes. "But then, I never was inside a globular nebula before—they may all be hollow, for all I know."

Daxon had to accept the tentative explanation. He could think of no better. In any case, there they were, and there was now a sun to worry about. He began measuring its apparent diameter, at first twenty minutes, then more, forty, fifty, as they approached it. Then a day came when the diameter began to lessen. They had passed perihelion, but on what shaped trajectory he could not know with any certainty. If it were hyperbolic, now, if ever, was there chance of escape.

Dr. Elgar had his own reasons for being relieved at putting more distance between them and the energetic sun. Appetites had grown voracious, animal spirits high, but with it signs of rapid aging, as shown by the graying at the temples of even the younger members of the ship's company. It was only by replacing the ray- screens that he could keep their rate of metabolism at normal. Amnesion seemed to be a region opposite extremes.

SHORTLY after perihelion, Daxon was casting about to port

with the periscope, scanning the lurid walls of the nebular

envelope. He was seeking some identifiable spot that he might use

as a point of reference to determine the extent of their

deflection by the inner sun. Suddenly the occupants of the

control room were electrified by his cry of "Planet-ho!"

Ahead and a little to the left, was a brilliant point of light, much in appearance as Jupiter viewed from Earth. Officers and crew crowded to the forward ports to look at the find.

In a few more hours, Daxon was able to announce that the angle between it and the sun was steadily opening—the planet was heading for its aphelion. If a little bit of maneuvering were possible, the Thuban might be made to intercept it. Yphon came and looked at the figures. He examined the newfound planet, and scowled at the hot little sun and the sultry background all about. He thought of their failing oxygen supply, and the dwindling stocks in the pantry. He sent for Ronny.

"Here's where we try out your jury-rigged auxiliaries, Ronny. Hook 'em up, and bring the juice up to the board here. I mean to land on that planet, if we can. We ought to be able to slow down a little, and the atmosphere there can do the rest—if there is an atmosphere."

He did not need to say that if there was no atmosphere, it didn't matter. Everybody understood the situation, it was a case of grasping at any straw.

What with the retarding effect of the millions of miles of gas they had traversed and Ronny's skillful adaptation of his surviving machinery, the Thuban's speed had been reduced to manageable proportions by the time they were in position for their planetfall. Coming in on a tangent about a hundred miles above the estimated surface, Yphon encircled the cloud-wrapped orb three times on a slowly tightening spiral, gliding swiftly through the tenuous stratosphere, braking as he went.

Elgar was quick to sample the clear gases outside. At first he found an equal mixture of hydrogen and nitrogen, but a little later there were traces of oxygen. When they were down to the level of the high cirrus, the proportion of oxygen had grown and the hydrogen content gone. One of their worries could be laid aside.

The planet not only had an atmosphere, but one that closely resembled air. It was a haven. They could go on down.

IT was not until they were below the level of the highest clouds that the milky, violet haze beneath thinned enough for them to see the details of the terrain. Lower were patches of other clouds, fleecy cumulus, and to the left the peaks of an extensive mountain range stuck up through them like the rocks of an offshore reef. Far ahead, glimpsed through rifts in the lower clouds, was the familiar blue of the sea, though tinged slightly toward purple.

As they drew closer to the ground, they could make out extensive stretches of vegetation, brown and yellow for the most part, indicating autumn. The Thubanites felt pangs of homesickness in looking down on the fair planet that was so much like their homeland. And the nostalgia was heightened by their first sight of what was unmistakably a town—then another, and they could see the threads of the highways between. Far ahead were the glittering domes of a great city just coming into visibility, a city lying by the side of an arm of the sea.

Wild excitement ran through the cabins of the Thuban. No one had forgotten the accounts of the disappearance in this region of Rangimon's two ships. If the Thuban had found her way through the encircling nebula here, why not they? Perhaps the population below were descended from those earlier Earthmen. As the talk buzzed, the ship slid on down, ever slower.

The city looming before them was quite extensive and entirely covered by a system of crystal domes, like those used on the airless planets, except that these were variously tinted in greens, ambers, pinks, yellows and blues. In the distance the aggregation looked like a mass of colossal soap-bubbles, iridescent in the noonday sun. Opposite, across the inlet, was a wide, barren patch of ground—probably a landing field, but at that distance they could not make out the characteristic slag flows of a rocket ship port.

But even as they were speculating as to the uses of the cleared area, small silvery objects could be seen rising from it into the air, hundreds of them. Through powerful glasses, Yphon and Daxon watched them take the air, wheeling and swirling like a flock of birds as the swarm headed for the oncoming Thuban. They were planes, planes of the primitive airborne type used so extensively on Earth in the pre-rocket days. A momentary apprehension that they might have hostile intent was quickly dissipated, for in a few minutes they were peaceably passing the ship on both sides, as well as above and below, and having passed, looped suddenly and turned to accompany her.

One, evidently a leader, swooped by the bow ports and as it did, a very old man leaned out over the side and made a gesture with his arm for the Thuban to follow him. The startled pilots of the space ship had only a glimpse of the steely blue eyes, the glistening bald head, and the whiskers flying flat in the hurricane of the propeller stream; but the ancient who had hailed them, apparently to make sure he was understood, shot on well ahead, went into a vertical loop, and swooped by again, repeating his signal to follow.

"Holy Comets!" exclaimed Daxon, as his second glimpse confirmed the first, "Father Time himself come out to meet us!"

But when the Earthmen peered out the ports at the machines pounding along at their sides, every pilot they could see was the same bewhiskered, aged, venerable type as the patriarch who lead them.

"WHAT a planet!" said the amazed Daxon to Elgar, as they

crouched, a half hour later, just within the open entry port of

the grounded Thuban. "But one thing's

certain—they're human."

"And another thing's certain," amended Elgar, dryly, "they've been human, from the looks of them, a darn sight longer than either you or I have."

The Thuban was lying where she had been led, in the midst of the great landing field opposite the city. Captain Yphon had slid open the entry port and was standing outside, ten paces in front of it, awaiting the representatives of the locality. The planes that had escorted them in were landing in successive waves all about, bouncing and rolling to stops. But unlike the custom of most friendly planets, where the natives rush to surround a newly landed ship, these people of Amnesion had moved with exasperating slowness.

The two officers had watched them climb out of their planes. That, it appeared, was an exceedingly laborious operation, and, once on the ground, their progress toward the waiting T hub an was equally difficult. They came on, though, tottering and stumbling, supported by staffs or canes, and finally stopped, forming a ragged semi-circle facing Yphon, as if awaiting someone yet to come. Some, too decrepit to remain standing, unfolded little portable stools, and sat. It was the air of incredible age about them all, the universal senility, that had prompted Daxon's exclamation. Toothless, wrinkled, many of them woefully bent, that strangely homogenous crowd made an almost unbelievable picture.

Presently a number of small cars sped across the field, rolling to a screaming stop just behind the assembled octogenarians from the plane squadron. A lane was opened in their ranks, and after considerable delay, a wheel-chair containing a venerable patriarch and attended by a small group who were scarcely younger, was haltingly pushed through it and brought up to where Captain Yphon was standing.

"That must be the grand-daddy of them all," whispered the irreverent Daxon, as the old man coughed, painfully cleared his throat, and began to speak. In a quavering, high cracked voice, he said, "Wall-kampt Athnaty."

The opening words were not at first understood, but as the old man continued, his auditors noticed that the language sounded strangely like English—English of an obsolete dialect, perhaps, but still English. They very quickly observed that its apparently garbled sounds were due to the queer cadences with which it was delivered. As soon as the knack of rhythm was had, understanding was easy.

"Welcome to Athanata," was what the patriarch had said, "the Planet of the Immortals. Gladly we receive the noble Earthborn, for like you, our pioneers fell from out the sky." He went on to say that he himself was Tolva, captain of the Star Dust, and that he was proud of his earthly birth, having been born near New Denver, in the shadow of "Paekpik." The astonished Thubanites knew from their study of the records, that a Captain Taliaferro had commanded one of Rangimon's transports, but that had been a cool two thousand years earlier, yet.

"Well, he looks his age," was Daxon's grunted comment.

After offering citizenship and the freedom of the city to the newcomers, Captain Tolva, if such he was, said that a guide and mentor would be assigned to each pair of men in the ship's company and that they would at once proceed to the city where all would be made comfortable. Yphon's interruption to ask for information as to the availability of mechanics and machine tools for the repair of the Kinetogen was dismissed as of no moment. "Not now," was the substance of the reply, "we are on the eve of the Great Holidays. In the coming Era, all things will be taken care of."

Yphon, seeing he would have to bide his time, made a dignified response to the address of welcome, couching his words as best he could in the same odd rhythm the oilier had used. Then the old man bowed acknowledgment and clattered on the ground with his staff. At the signal, a dozen of the waiting centenarians tottered forward and saluted. Those were to be the companions and tutors of the Thubanites.

CAPTAIN YPHON, choosing old Angus to accompany him, was driven off toward the city in the official car of Captain Tolva, leaving the others to pair off as they chose. Daxon and Elgar naturally fell together, leaving Ronny no choice but to team up with Ulberson. Two by two the crew fell in and met their guardians, grinning sheepishly as the testy old men ordered them about as though they were children.

The one told off to take care of Elgar and Daxon was somewhat spryer than the rest, fie led them to one of the little cars, managing rather better than most as to locomotion, but his millions of wrinkles, sunken cheeks and knotted linger joints told plainly enough that he had been living a long, long time. The two officers got into the car, noting with amusement that its driver was, if anything, a couple of decades older than their guide.

"Say, Sid, if the girls in this town match the boys," laughed Elgar, "you're going to find night life pretty tame."

Any reply Daxon might have made was cut off with a grunt as his head hit the back of the seat. The driver had started the machine and it leaped ahead like a rowelled bronco. They were tearing across the landing field at dizzy speed, zig-zagging wildly among dozens of other such cars, each racing and jockeying for position, dodging parked planes with an agility that would be astonishing in any driver. In a very few minutes they were climbing the ramp that led across the elevated causeway over the lagoon that separated them from the crystal domed city. Elgar caught a glimpse of what probably was a park beneath, but at this season its grasses and trees were uniformly yellowed and sere.

Daxon, leaning back, gripped his hat with one hand and tried to fend off the whipping beard of their antediluvian jehu with the other. Once, he glimpsed the startled faces of Ronny and Ulberson as they were whisked by, gaining a lap in the race of toothless madmen. Daxon attempted a hail, but the others were too occupied with hanging on to their own seats to notice.

"Phew!" whistled Elgar, as they eased through a great semi- circular opening in the first of the great crystalline domes. "These old dodos are rickety enough on their feet, but boy, how they cut loose when they have machines to carry them."

Once within the city, the ancient driver relaxed his pace, and it was well he did, for the streets were crowded with people, none of them agile enough to move faster than a walk. Like those at the landing field, all were unguessably old. Among them were many women, centenarians like the men. Some were skinny hags, others stupendously fat with multiple chins, and in between was every intermediate grade of crone and beldame. Dr. Elgar looked at them all in blanket astonishment—thousands of people, all senile. He wondered why there were no young, how the race was carried on.

The dome they were under was of a dull moss green hue, giving everything beneath it a sort of under water aspect. The buildings appeared to be of stone or brick and were reminiscent of old prints of Earth cities of several millenia before. Some houses were windowless, copies of the architectural monstrosities erected in America City during the first century or so of air- conditioning.

They had hardly become accustomed to the green, lighting when they passed through another arch into a quarter of the city under a rose-colored dome, and after that into a third where the light was a mild amber. Their car turned a corner and pulled up in front of a building bearing the black-lettered sign, "Conservation Unit No. 3."

"FOR examination and registry," croaked their guide,

laconically, "the branding will come later."

The latter phrase caused the two officers to exchange inquiring glances, but they got out of the car and followed their tutor into the building. Passing down a wide and rather crowded corridor, they caught sight of Captain Yphon through an open door. He was protesting something earnestly to a smallish, bespectacled old man in white, and gesturing toward his eyes as he talked. Before the boys could see what the controversy was about or catch the Captain's eye, they were led on past and ushered into an office.

In what was evidently a sort of anteroom to more offices beyond, they found to their astonishment a railed off enclosure filled with benches upon which sat scores of old men and women. Over their heads was the incredible sign, "Newborn Assemble Here."

"Never mind those," said their guide, rather contemptuously, "being Earthborn you are in a favored class. Follow me, if you will."

In an inner office they were confronted by a huge desk behind which sat a jovial, fat old Santa Claus, presiding over a gigantic ledger. He greeted them with a twinkle of the eye, and at once began asking questions as to name, date and place of birth, and so on, writing all the answers down. When he found that both candidates had been living less than forty earth years, he banged a bell for his messenger, waggling his head sadly.

"I am afraid," he said, apologetically, "that we will have to postpone the rest of this until after the doctor has passed on you. Get Dr. Insun," he said, more sharply, to the messenger, an emaciated old gaffer of some hundred and ten years at the very least.

Presently the bespectacled little man whom they had seen arguing with Yphon came in. He wore the white smock of his profession, but he did not have the cheerful manner that many doctors maintain. His bearing was that of a man who expects the worst of human nature and thinks there must be deception if he doesn't at once find it.

Quite briskly, for he seemed to have fewer disabilities than most, he proceeded with a cursory physical examination of the two Thubanites, pursing his lips and frowning all the while, giving vent as he went to mournful "Hm-m's" and "Tut-tut's." Finally he turned to the benign registrar and said rather jerkily, "not good specimens like the other two have to take it up with the High Priest..." then he glowered at the two young men again as if to assure himself he was making no mistake "all wrong—everything. Now, that one called Angus was perfect, and the other—Captain Yphon—if we can get his eyes fixed up he will be a valuable addition to the community. But these two..." his voice trailed off into a mournful silence.

"Won't live through the Long Night, eh?" added the jovial one, with an air of commiseration. Then he suggested, "Why not put them under the big lens on No. 7?"

The doctor shook his head gloomily. "Not time enough—only forty-four more days, you know. Sorry, but they're hopeless. May as well turn them loose and let them enjoy themselves while they can. They can't possibly survive—why, they're barely mature, mere children, too young!" And with that cryptic pronouncement of unworthiness, the doctor left the room with "the air of a man washing his hands of a bad business.

"Old Angus a perfect specimen!" muttered Daxon, looking blankly to Elgar, "but we are too young to survive. Say, what kind of screwy outfit is this, anyway?"

But Dr. Elgar was thoughtful. He suspected it was not the utter nonsense it sounded.

And yet—what else but nonsense could it be?

Astonishing Stories, December 1940, with second part of "Quicksands of Youthwardness"

THE exploring space-ship Thuban, coming within range of Sirius' dangerous gravitational pull by order of its domineering supercargo, the explorer Ulberson, blows out its motors in the struggle to get away. The ship escapes from Sirius, but wanders aimlessly through space, at a vast speed, for months. In that time the crew is able to jury-rig some auxiliary motors, but they will last only a short time, and cannot therefore be used to get the ship back to Earth.

In its wandering, the Thuban approaches a "coal-sack" in space, a dark cloud through which no light is visible. They are powerless to alter the course of the ship without ruining the auxiliaries as well as the main motor, so are forced to pass into the cloud.

Examination of the space-atlases shows that this cloud has been christened Amnesion by the few persons who have ever been inside it, because of its curious property of causing those who enter into it to lose their memories. Captain Yphon of the Thuban believes that some radiation from the cloud docs this, and has the entire ship ray-screened. But he himself looks at the cloud through an unshielded telescope, and his eye suffers a remarkable transformation. A cataract on the eye disappears and his sight becomes as good as it was when he was thirty years younger. Simultaneously he forgets everything that occurred for an hour before he peered into the telescope.

After they have penetrated almost to the center of the space- cloud, the radiation vanishes, and they spy a planet. Using the auxiliaries, they effect a landing. They are surprised to find that the planet is inhabited by incredibly aged Earthmen, descendants of marooned spacemen or in some cases the wrecked spacemen themselves. They speak a clipped, slurred form of English, and hold everything that comes from the Earth in deep reverence.

As soon as the crew has landed, they are subjected to a medical examination. The older members of the crew are treated with great respect, having come from Earth. But the younger Thubanites, though also from Earth, are disregarded.

When pressed for an explanation, one of the patriarchs of the planet, which is called Athanata, tells them that there is no point in treating them with any respect, as they are too young to live long on the planet.

IN the days immediately after their landing, the boys took in the sights. There was little else to do, for the old people were very definite that nothing could be done about repairing the Thuban during the holidays, which were of a religious nature.

Captain Yphon was living with the Prizdint, as the chief magistrate was quaintly called, after an old title formerly borne by the chief executives of America. The others were billeted in various quarters of the city, each pair being taken care of by some local family.

Elgar and Daxon were quartered with one Pilp Tutl (or Philip Tuthill, for he claimed to be one of the Earthborn) in a pleasant house in a quiet district under a pale rose dome. Tutl and his wife were far better preserved than the run of the inhabitants of Hygon, as the city was called, and so were their neighbors. The old couple were very considerate hosts, and after a brief chat at dinner, showed the boys to their rooms and then left them to themselves.

The apartment, to Elgar's delight, since he was something of an antiquarian, reminded him of the Twenty-Second Century Wing in the great museum at America City. It had the same tile-lined water bath, an elementary television set in a little cabinet, and the primitive system of lighting by means of small glowing wires enclosed in exhausted glass containers.

"Pretty soft, even if it is old-fashioned," commented Daxon, looking around. "Beats zipping through the void with nothing to breathe and less to eat."

In the morning, Tutl went out with them long enough to acquaint them with the lay of the city, then left them to their own devices. He saw that being so young and active, they could get along much faster by themselves. Furthermore, as superintendent of the power plants, he had his own work to do. He apologized for leaving, explaining that he must attend to the laying up of the machinery in preparation for Sealing Day, which was close at hand. With that, which meant nothing to his guests, he was off.

Despite the generally feeble condition of the population, there was much activity in the streets. Gangs of fairly spry old men were at work everywhere, boarding up ground floor windows, erecting heavy crating about exposed statuary, and bolting signs to buildings. It was as if preparations were being made for an approaching hurricane. The signs most noticed bore arrows and the words "Food Depot", and they were placed at frequent intervals along the street.

At a good store itself, they saw truck after truck roll up and discharge its cargo of packages, each of the same size, like picnic lunches. Craning so they could see into the door, Elgar noticed that inside there were no tables or counters—only rows and rows of deep bins, almost all of which were already full of the uniform packages.

IT was the museum that interested them the most. Beyond the

interminable rows of showcases containing bits of flora, fauna

and minerals of Athanata, was a great bay in which were housed

the space ships of the pioneers. The ships sat on concrete skids

with wooden stairways built up to their entry ports. A gang of

workmen were busy laying out a rectangle beyond the last one,

taping off distances and making blue chalk-marks on the

floor.

There were four ships there. The two tremendous transports of Rangimon, in which the first-comers had arrived, filled the center of the hall, while at one side of them was Sigrey's somewhat smaller Procyon, and on the other the wreck of a little freighter bearing the embossed name Gnat. The last was badly pitted and scored, and its bow bashed in, but intact. Behind the ships, lining the walls, were additional rows of showcases containing displays of the material found in the ships.

Elgar looked over the cases first, much interested in the medical supplies and first-aid kits furnished ships two millenia before, while Daxon was equally eager to examine the antique astragational equipment. The cases contained a queer hodge-podge of stuff, all the way from nuts and bolts to can-openers. They found Ronny back there, with one of his men, making lists of stuff they could use, in case a little burglary seemed expedient.

There was a reading room in a small bay back of the Night Dragon where the ships' libraries had been put, and there were more cases containing the logs, the muster-rolls, manifests, and other ship's documents. They noted that the Gnat was laden with telludium and other rare ores, bound from Tellunova to Earth. Among the papers of the Night Dragon, they saw their host's name, Tuthill. He had said he was her chief engineer, that is how he came to have charge of the city's powerhouses. But oddly, he knew nothing whatever of the installation on board her. Said he couldn't remember, but it was all in the books. They could find out about it, if interested, by going there and reading the engine room log. That is the way he found it out himself, he admitted, blandly.

They inspected the ships, all of which were of the obsolete rocket-propelled type. They had been pretty well gutted, as was to be expected, considering the yards of well-filled cases out on the floor, but they found that most of the Gnat's cargo was still in her.

"You know what I think?" demanded Daxon, replacing the manhole cover of the cargo hatch of the Gnat, and sniffed the heavy odor of telludium quintoxide that had welled up to him, "these old galoots can't know what this stuff's good for, or they'd have used it. From the looks of this town, there hasn't been a new idea in it since the year 2300, and that's funny, because they're human. They ought not to stand still this way for two thousand years."

But Elgar did not answer. He was on ahead, staring down into a long showcase set on trestles in the control room. In that case, neatly wired up, were twelve tiny human skeletons. All were complete, except that one lacked a left arm.

"Children—fifteen months to two or three years," said Elgar, in a low voice, and pointed to the label stating, "This vessel found early in the 14th Era in Province of Nu Noth Klina, evidently having fallen out of control. These skeletons were found huddled in control room. There is no evidence as to when or how the crew abandoned ship, or why they left these infants behind to starve."

"MY GOLLY, Sid>" exclaimed Elgar, tense, with excitement, "I

have a hunch we're about to get the lowdown on this queer planet.

You remember that old billygoat that examined us the first

day—he said we were too young to survive. Well, that is

what he meant..." pointing a trembling finger at the display of

little bones. "Come on, let's ransack this Gnat's

papers."

Somewhat mystified, Daxon followed Elgar back into the alcove library, where they pulled down the log, the muster roll, and other documents of the vessel. Elgar found the crew to number eight, with four officers. "Look for something about losing an arm," he urged Daxon, while he himself began searching the library for the ship's binnacle lists.

The last entry in the deck log said simply, "Expect to enter dark nebula at about five bells." That was all. There were no notations for months before to indicate any distress or fear of it. Daxon found nothing until he had gone back to the second week after clearing Tellunova. Then, there was this entry, "...at six- teen-fifty-three, Tubeman Simok became entangled in pericycloid mesh: left arm badly mangled. At seventeen-twenty, Lt. Tosson amputated arm. Simok resting comfortably with fair chance for recovery. Severed arm ejected through port tube."

"That's it!" ejaculated Elgar. "Twelve men on board, one of them one-armed. Twelve skeletons, one of them one-armed. That's the crew there, Sid, what's left of them."

"You're crazy," said Daxon, "you know nobody'd send out a shipload of tricky telludium ore with only a crew of kids. Why, hose weren't even kids, they're babies."

"No," said Elgar, soberly, "I'm not crazy. This all ties up with what we've already seen—forgetfulness, coupled with rejuvenescence—we see signs of it everywhere. We'll get younger and younger, and then finally go out like a candle, unless we starve first. The skipper is old enough to take it, he has the years to spare, and so has Angus, but you and I and the others are too young."

"You may see it, but it's thick as mud to me," retorted Daxon, thinking of their Earth-like surroundings and their own safe passage through the outer envelope of nebula.

"I may be wrong," hesitated Elgar, "but I think we'd better split up and each of us go on a still hunt. Find out what you can about the Athanata's orbit, and their calendar. I'll tackle the medical and historical angles."

THE evidence of the tendency toward forgetfulness of which Elgar spoke was mainly in the abundance of signs all over the city telling in utmost detail the uses and ownership of every building and thing. Not only did public buildings, such as libraries, carry brass markers setting forth what they were and how they should be used, but dwellings were similarly labelled.

Tutl's house, for an example, had an intaglio set in the wall beside the entrance stating it to be the home of Filp Tutl and Febe Tutl, and also gave their description and identifying marks and the information as to where spare keys were kept, and references to file numbers in the city's archives where additional information could be found. Besides that, one morning the two officers were astonished to find a pair of aged workmen affixing a bronze tablet alongside the Tutl marker. It stated, "Dr. Elgar—Sid Daxn—your home, come in." And below was their description and spaces left for their serial number which had yet to be assigned.

They blinked when they read it. That was hospitality with a vengeance. But now they were beginning to understand the significance of the branded or tattooed marks on people's forearms, giving their names and other data. It was preparation for a spell of amnesia. The sufferer, or his finder, had but to look at the marks, and he knew where he belonged and where his history was filed.

There was also the matter of keeping notebooks. Just as the Thubanites had started diaries in coming through the fog, so did the Athanatians record everything they did. Houses were filled with filing cases, and duplicate copies were placed with the priests in the Temple.

One day a priest came and carted away the records of Tutl and his wife, but returned a few days later with them. "Hardly any deletions," said Tutl proudly, showing the diaries to Elgar. Occasional passages had been blocked out, as by a censor, but in general the record stood.

"That's why we are such a perfect race," Tutl continued. "Here is everything worth while I've ever done. Mistakes which teach no lesson are blotted out, and we forget them. In the new Era we will start off with only the best experience to guide us. Those are grand books," and he affectionately patted the filing case, as he twirled the combination lock.

ELGAR'S research in the library was not particularly illuminating. There was a copious literature dealing with the history of Athanata and the city of Hygon, but the more of it he read, the less was his understanding. It seemed to require a key.

There were detailed accounts of this Era and that Era, but except from their numbering, it was nearly impossible to say whether a given Era preceded or followed the next one to it. It was as if a single history existed that had been run through many editions, each differing from others by minor additions or deletions. Always there were the same personalities, doing much the same things. Except that the earlier periods told of the construction of the city, while the later ones dealt only with repairs and slight additions, one Era was much alike any other, yet they were evidently distinct periods, though unconnected in any way. It was as if Time, in Amnesion, was not only discontinuous, but repetitive.

Daxon had even less success in his efforts. There was no planetarium, and people looked blank and just a little shocked when he questioned them about their relation to the sun. It was as if there was something sacrilegious in the inquiry. If there was any knowledge of astronomy, it was a secret of the priesthood, whom Daxon found singularly uncommunicative.

As to the calendar, it was nearly meaningless. Athanata did turn about an axis, but other than days the units were arbitrary and unrelated to astronomical realities. Thirty days made a month, and twelve months made a year—perhaps a tradition brought from Earth. But how many such years it required to make the circuit of the sun was unknown. Maybe the natural year was what they called an Era, but an Era appeared to be roughly eighty Earthly years, although the beginnings of each was hazy and indefinite, like the dawn of human history.

But Daxon resolved not to let the ignorance or superstition of the old men get the best of him. He took a run out to the Thuban where she still lay as she had landed in the midst of the field. He picked up his old file of observations on the sun. Day by day he made new shots and plotted them in curves. Given a little time, and he would work out Athanata's orbit for himself, although it didn't really make much difference.

IN the meantime, the business of securing the city against

whatever was to come was about finished. The food depots were

filled, their doors opened wide and secured at the tops so that

they could not be easily closed. At night the populace gave

itself over to a carnival of pleasure and merry-making, much in

the fashion they formerly did on Earth at the approach of the New

Year. Old men and aged women mingled in the streets, hilarious

and gay, or filled the cafés, grotesquely attempting to dance,

cackling all the while in high glee. Elgar would wander among

them, tremendously curious, marveling at what he saw.

Hearing that Ronny had renounced the city and gone back to the hulk of the Thuban to live, Elgar went out there one day with Daxon to see him. Ronny had found the companionship of Ulberson distasteful, and the antics of the ancient couple where he was quartered disgusted him. Ulberson had wangled a plane, somehow, out of the authorities and gone off into the interior of the country with a bagful of notebooks and chart-paper to do some exploring. As soon as he went, Ronny rounded up most of the ship's crew and went back to live in it. To amuse themselves, they pottered about in the engine room, piecing together bits of the blasted Kinetogen, welding them into bigger fragments.

"Anything to keep from going nuts," was the way Ronny put it. "I couldn't stand that wizened old galoot they boarded me with or the harridan that keeps him company. When a couple of octogenarians start making whoopee, I'm done. Didja ever see a couple of superannuated scarecrows try to jig?" he demanded, in righteous indignation. "And then when I found out what the old bird's occupation was, I walked out. He's in charge of the delumination plant, if that means anything to you. It's a field south of town where they have all those black balls and bolts of black velvety stuff parked in the sun. Absorbs light, he says, but what the use of it is, he didn't even know himself. But he's proud of his job—says it is important, as we'll see, on final Sealing Day. Rats!"

Elgar and Daxon chatted with him a little while, amused at his contempt for the Hygonians. As they left the ship, they encountered a group of the old codgers just outside the entrance. Beyond them a truck was parked and there was a post-hole digger nearby. The old men had just finished setting a post opposite the Thuban and attached to it was a sign bearing these words:

"Earth skyship Thuban. Fell 87th year, 17th Era. DO NOT OPEN until sun half high. Place in museum on blue X's. For instructions see Folio BH-446, Locker R-29, Little Temple. By order, High Priest."

"So that's what they were laying out on the floor by those other ships," grunted Daxon. "They mean to add this one to their collection."

"Like Hell!" snorted Ronny, dashing among the quavering oldsters, shooing them away. He seized the half tamped post and pulled it up by the roots and cast it out into the field. The boss of the post-setting party tried to remonstrate, but made no headway against youth and vigor. Shaking his head and muttering something about the heinousness of resisting the High Priest's order, he gathered his gang together, and after mouthing a few more protests, drove away at the mad rate always affected by the old men when they handled machinery.

ELGAR looked significantly at Daxon.

"These people don't mean for us to leave—not if they've already picked a spot in the museum for the old Thuban."

"This ship don't go into anybody's museum. Not yet, anyway," blurted Daxon, with considerable heat. "She's my ticket home, and not all the tottering old dodos in this crazy city can take it away from me."

They discussed with Ronny the chances of getting the ship off. He shook his head gloomily.

"I inspected those old wrecks at the museum—thought we might swipe one, but it's no go. They're the old atomic powered type, and there's not an ounce of fuel left aboard any of them. That's why they're stuck here. If we had the makings... I know it's dark, but I guess the planet will turn around when she comes to the end of her orbit and go back. That's all I know so far."

"I was afraid of that," remarked El-gar, thoughtfully, but it was the unguessable hazards of amnesia and the unnatural rejuvenation of the light-hungry fog that troubled him, not the dark or cold that any spaceman knows how to deal with. "Let's go see the skipper and put it up to him."

AS they drove through the streets, Ronny nudged them, calling their attention to the men setting black spheres on low brackets of the city's street lighting poles. They were the "deluminants" he had spoken of so contemptuously.

"Can you tie that?" he snorted. "Deluminants! Supposing black does absorb all the light that falls on it? So what? The dimming effect in this street you can put in your eye—anyway, what's the idea?"

But farther down the street they saw more of the deluminant stuff being rigged. At one of the big food emporiums, men were at work inside the widely opened doors, draping black velvety cloth on the inner walls, like the preparation for some grand state funeral. The doors to the food building had been secured at their tops so that they could not be closed easily. On the other hand, when they passed the museum and the main library, they noticed that their doors were closed and covered with great seals, and barricades built in front of them. Mystified by these unaccountable preparations, they hurried on to the place Yphon was.

They found him lying in an easy chair on the roof of the Presidential palace, his eyes covered with goggles having heavy clear lenses. He was looking up at the sun through an opening in the heliotrope dome, and was evidently dictating something to a black-robed little priest who sat by him taking copious notes. Behind the chair stood the wizened and bent old gerocomist who had been assigned him to affect the "restoration" of his eyes. The two Athanatians, at the unmistakably determined order of the three younger and vigorous men, flutteringly withdrew a little way toward the parapet, the priest clutching up his notes in palsied hands.

The Thuban's officers saw with their first glance that the Captain's forearms were elaborately branded with the tattoo- like markings worn by all Hygonians, and through the open front of the robe he wore they could see much other information inscribed on his chest, starting with the words. "Pol Yphn, Capt. Thubn. B. Earth—4333 E.T." and so on, even to the cumbersome serial number assigned each citizen, together with the usual cryptic references to files and lockers.

"What's the dope, skipper?" asked Daxon, affectionately, noting the branding and the Captain's attitude of resignation. "Gone native?"

"Part way," said the Captain, attempting a feeble grin. He took off his goggles and held them in his lap. "I was just about to send for you, though. There are some things you should know."

Elgar was shocked at the Captain's eyes. They were in almost the condition they had been the day they pulled out of the fall onto Sirius—faded, dull and yellow, the eyes of an aged man. But he said nothing about it, the Captain had cleared his throat and was talking.

"You boys must round up all the crew and take them aboard the ship. Dig in there behind screens, like you did coming in here, for I am afraid there is real danger ahead. Maybe you'll be immune there. As for me, and Angus, we'll be all right outside, so don't worry about us. Take care of yourselves, that's all I ask.

"It seems that they are at the end of an Era here—day after tomorrow is the last day, the day of the Final Festival. Then comes the Dark. And in the dark, so the priests say, everyone's sins are washed away and forgotten; their physical disabilities and decrepitudes removed; they will all come out at the beginning of a new Era young and strong. I know that sounds like a lot of poppycock, but on these planets of the south weird things do happen—impossible things, by any Earthly mathematics—I have seen plenty of queer ones long before we fell into Amnesion.

"The fact that the race here is controlled by the priesthood makes me think they only partially understand it themselves. It is a peculiarity of the human race, whether at home or on the farthest flung planet, that when faced with the Unknowable, they make it into a religion. I have an idea that they knew here what happens, but not why. However that may be, we see millions of people living and thriving under the conditions of this system. We have to believe them, follow their advice.

"To put it briefly, we are going into the Dark—that nebula, probably—and in there we will grow younger. And we will lose some of our memory."

ELGAR nodded his understanding. He had already guessed that

much. Yphon looked very worn and tired, but in a moment he went

on.

"For the best interests of the ship, I've taken their advice. The Prizdint assures me that it is impossible to do anything about repairs until the new Era. That is why I am dictating these notes. They want a record of everything I know—all our newer inventions and the later developments at home. When the next Era comes, I can reread what I have written and refresh my memory. In here are the plans for getting the Thuban back in commission, and taking her home. The Prizdint promises he will give us every help, if after seeing this city in the new Era, we will want to go back."

"An easy promise... seeing that he will forget it, and so will we, along with the desire," interrupted Elgar, bitterly. He was thinking not only of the preparations made in the museum for the display of the ship, but of the blacked out passages in the Tutl diaries. "Your notes have been put in a safe place, I hope?"

"Oh, yes... the Big Temple. See..." and he pulled his robe open wider and pointed to the "ZR-688". "My personal file. This priest is my amanuensis. He writes it all down and takes it over there every day and files it. If I slow down, or run out of words, he prompts me—asks questions. Smart fellow, that little old priest."

"Smart. Too smart," thought Elgar, anxiously. The Captain was in greater peril than he realized. The hierarchy that ruled Athanata would be only too glad to wring his store of knowledge from him. And equally, they would want to entrap a man of that caliber and add him to their stagnant population. Elgar saw his brother officers shared his feelings, but with a quick gesture of the hand he indicated to them to let it pass. They could discuss it later, among themselves.

"This process of rejuvenation in the dark, as I understand it," the Captain continued, "goes on evenly all over the body. That's why they're aging my eyes again. That concentrated dose of rejuvenation I got through the magnifying lens of the periscope put them out of step with the rest of me. The doctors say that if I left them that way I would be blind in the end. While I am getting younger, they would degenerate to nothing—or embryonic eyes at best—wouldn't develop afterward.

"There ought to be nothing harmful about getting young again. Not if you're old enough at the outset. But when I was down at the Registrar's to get my number and have them print the records on me with that ray-machine, I watched them running all those newborn—the ones born during the current Era—through. They number everybody indelibly, because they forget. They would lose their identity in the dark. I asked about you, but the old man in charge there just shook his head and said it was no use. It didn't matter. You were all too young to bother with. They don't want your names in the ledger because it would make their statistics look bad. Since they regard themselves as immortal, records of people who die are blots on the system."

"Immortal my eye!" rasped Ronny, with a short laugh. "Why, coming through South Portal the other day, I saw one of those old buzzards—you know how they drive—wrap his Leaping Lena around that statue that stands in the middle of the concourse. If he wasn't dead, I don't know what it takes. They must have picked him up with a blotter."

"ACCIDENTS don't count," said Yphon, with a return of his old,

grim humor, "they can't be blamed on the priests or doctors. It's

age they worry about, and that's why they have this system of

tinted domes. They are really ray-filters to regulate metabolic

rates. With recurring rejuvenation, it is important that

everybody reaches the end of an Era at the same equivalent

age. They start off the new Era all alike. The original pioneers,

the colonists on the two first ships, are almost all alive,