RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

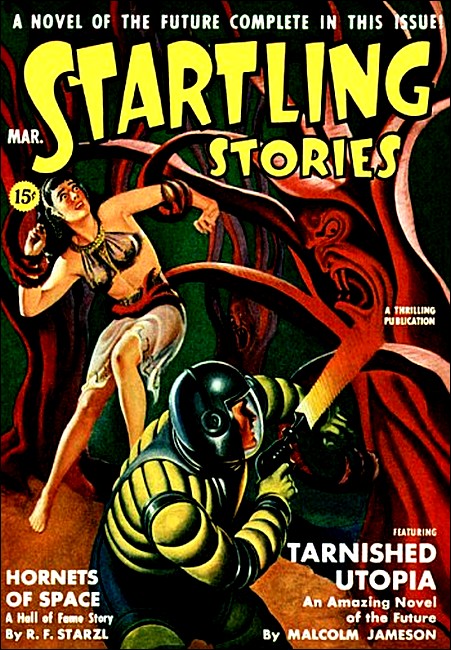

Startling Stories, Mar 1942, with "Tarnished Utopia"

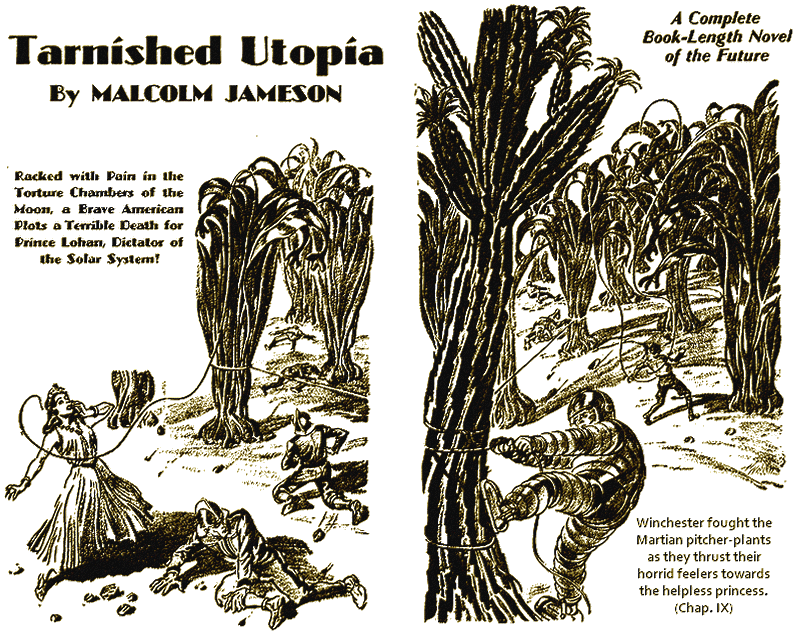

A fascinating fast-moving adventure of a man and a beautiful girl of the present, who find themselves in a strange cruel land of the future. Transferred to a vicious world, ruled over by the cruelest of dictators, he falls in love with Cynthia (the girl from the present), but finds her cold to his attentions. The man, Winchester, is made a slave; racked with pain in the torture chambers of this strange and hideous land, this brave American plots a terrible death for the tyrannical dictator. This is the type of light-reading, fast-moving adventure you won't want to put down until finished.

He did not know what had happened, or how, or when. He only knew he was falling. Instinctively he began counting. Somewhere above him the ship was falling, too. Down below, still a long way off, he could see a bed of search lights, its rays probing the clouds—looking for him, no doubt.

At the count of six he pulled the cord. Then he felt the jerk on his harness as the 'chute bellied out. His head ached fearfully and he realized for the first time he was wounded. He did not know when he struck the earth or how far he was dragged across the fields.

The hospital ward was not so bad a place, considering it was in a prison camp. Only there was never food enough. It was later, though, that he felt the pinch of real hunger. That was after he had been pronounced fit for duty and sent out daily with the other war prisoners, to repair the holes made nightly by Britain's bombers along the main railway line.

"Serves me right, I guess," Allan Winchester muttered to himself as he shouldered his pick and shovel and stumbled along after the rest. "I had no business mixing in another fellow's war."

But the guttural curse of a burly guard and the threat of the ever-ready gunbutt made him change his mind. He ducked the blow and hastened his stride, but red rage surged within him.

"No," he added, in an inaudible growl, "it is my war! It is everybody's war who hates cruelty and oppression. I'll see it through. Ruthless tyrants shall not rule the earth!"

For a moment Winchester's thoughts had gone back to the good job and cozy home he had given up in the States to fight these dictators. He had been a consulting engineer. Moreover, his bachelor bungalow in the suburbs had been the gathering place for others like him who shared his devoted hobby.

In Winchester's rare garden a few amateur enthusiasts carried on the work begun by Burbank—the creation of new and interesting plant hybrids. All that the American engineer had surrendered in a glow of indignation over the treatment of the helpless little countries of Europe. One day he had flown to Canada and joined her air force.

"And here I am," he muttered again, ruefully, "shot down in my very first big show."

"Ssh-h-h, Yank!" came a cautious hiss from the man next to him. They had been detailed to fill in a new-made bomb crater. The guard had gone on forty yards beyond.

"D'ya want to join the gang?" whispered his mate. "We've tunneled under the barbed-wire fence. Tonight's the night. Ten are going, but they say there's a hiding place outside for one or two more. Friends, you know. Working undercover."

"Count me in," answered Winchester in a low voice. He sank his pick into the soft shoulder of the crater. The guard had wheeled and was looking their way.

"I'll tell you more at mess-time," said the other man softly, as he flung a shovelful of damp earth down the slope.

Allan Winchester, the American, was the last man through the hole. Wriggling along like an earthworm, he thought the tunnel interminable, especially since the passage of the others had caused several cave-ins, which had to be dug out with the hands and pushed backward with the feet. By the time he emerged into the dark night outside the barricades, the others had gone. Winchester brushed the loose dirt from him and groped his way forward. They had told him what to do if they became separated.

It was then that the hoarse-voiced whistle on the prisoners' steam-laundry building broke the night air with its raucous blast. A flare burst overhead and floodlights came on. Rifle shots rang out. Off to the left a machine gun began to chatter. Winchester heard men shouting in the fields ahead of him, and the sudden scream of a stricken man. He dropped panting into a little ditch and crawled into some shrubbery.

For hours he lay there in a cold sweat. Heavily booted men crashed through the brush repeatedly, prodding with bayonets.

"Zehn," one said. "Ten we got, already. The Kommandant says there should be one more."

Dawn came, but they did not find the American. He stayed there all day without moving, though his thirst became painful. For far and near sounds told him the search was still on. Somehow the news must have leaked out. The prison break had turned into failure. What was to have been escape ended in a death trap.

Winchester lay still another night and day, except for chewing some lush grass for the moisture that was in it. Then on the third night he stole forth and crossed the pasture beyond. It was at Munich, those prisoners from Dunquerque had told him, that he would find friends and shelter—if he could only get to it. The address he had long since memorized.

It took Winchester four nights, walking always in the fields and skirting villages and highways. He drank occasionally from brooks and once succeeded in stealing a hatful of vegetables from a farm garden. But in time he reached the outskirts of Munich and knew that for once he was in luck. A vigorous British air raid was going on.

He made his way to the heart of the town unchallenged. Troopers and firemen were everywhere, but they had their hands full snatching at dazzling fire-bombs or dodging crashing masonry. Winchester hurried on, searching for the small alley three blocks west of the Schutzenplatz. He had little trouble finding his way, despite the pandemonium of flame and destruction going on about him, for Munich was a city fairly familiar to him. He had lived there for months when he was a student before the war.

It was during a lull in the aerial attack that Winchester reached the neighborhood. The street was perfectly dark, except for the dull red glare of reflected fires. The blackness in the alley was as pitch. The American stole into it, feeling with a cautious toe for stumbling-blocks among the cobbles.

He had hardly gone four steps when he froze motionless against a wall. Overhead a brilliant magnesium flare suddenly blazed, lighting the place up like noon. Winchester waited, tense, while it burned out and slowly drifted away. Then, as the dark returned, he took a step forward.

"No!" A soft hand clutched his sleeve. "This way. Say nothing, but—oh, please—hurry!"

The voice was low and vibrant, the voice of a woman. Winchester could barely make out her outline in the darkness, but he judged her to be young. Her hand found his and tugged. He followed her blindly. She had spoken to him in English!

She must be one of the friends his fellow prisoners had told him of. But to his surprise, instead of taking him deeper into the alley, she darted out into the broad street from which he had just come.

"Where to?" he asked huskily.

"Anywhere," she answered in an agonized voice. "Anywhere but there! I have just learned we were betrayed. Two of our members are Gestapo men and they are waiting there for us now. Come!"

They ran blindly in the dark, down one street and up another. Bombs were bursting steadily to the westward, and the barking of the ack-acks was almost continuous. A sudden flare lit the street up once more. Dead ahead of them were two gendarmes. One raised his arm and shouted a challenge, then charged forward. The girl jerked Winchester into a doorway.

"Try this door," she moaned. Her voice was urgent.

The door was locked, but Winchester drew back a yard and launched himself bodily against it. There was a rending of splintering wood and the portal crashed open, hurling the American twice his length into a dark hall. He picked himself up dazedly, only to find the girl was once more at his side. Heavy footfalls were heard running by the door. The police paused, hesitated and turned back.

"Here is a stairway going down," the girl whispered in the dark.

They tumbled down it. It was a spiral staircase and of stone. They had reached the first stage below when they heard the upper door burst open and the yells of their pursuers. Almost in the same instant there was a deafening crash and a blinding flash of light. They were flung into a far corner, and cowered there while they heard the building above them come crashing down. A bomb from the sky had miraculously covered their retreat.

Winchester lay quietly, holding the trembling form of his rescuer in his arms, until the last of the reverberations died away and until the dust which filled the air settled a little. If the policemen above had died, they had died instantly, for they made no sound. At length, assured of comparative safety, Winchester moved the girl a little way and fished out his box of treasured matches. He struck one.

They were in what appeared to be a medieval vault, of heavy stone construction. The stairs down which they had come were choked with fallen debris from above. There was the smell of smoke in the air. Beyond the circle of the flickering light the stairs curved on down into blackness.

"We had better go lower," Winchester said, lifting the girl. "The sub-cellar is the best place until this raid is over."

He did not say so, but what he feared now was fire. It was obvious they had escaped one fate only to be trapped to await another.

Before a huge nail-studded oaken door the stairs ended. The American lifted the heavy wrought-iron latch and swung it open. Inside were rows of glistening white tables, and in brackets on the walls Winchester was delighted to see wax candles. He lit one and closed the door behind.

"How incongruous!" the girl murmured, looking about. She still trembled a little, but her air was as unafraid as though she were at a party. "Look, a modern diet kitchen located in this gruesome old dungeon."

"The guy that did it knew a good air-raid shelter when he saw one," explained Winchester, casting an appraising eye over the groined stone arches overhead. "They can blast the whole town down and we'll still be all right."

But something more than the security of the chamber had taken his eye. At one end of the room was an immense electric refrigerator. The girl already had its door open, looking over its contents. People in blockaded countries soon learn to scout for food at every opportunity. Winchester himself was famished.

Now that there was light, he could see the pinch of hunger in the girl's pale face. He wondered how beautiful she would really be, with color in her cheeks and the sunken spots rounded out once more. For despite his preoccupation with food and safety, the American could not miss observing that she was the kind of girl a man meets but once in a lifetime.

"Smells all right—smells good," she pronounced, dragging out a glass bowl filled with an amber-colored gelatine. She poked a finger into the quivering stuff and tasted it. "It is good!"

They both laughed. The girl set the bowl on the shelf while she crossed the vault to the tables on the other side, where plates and cutlery were stacked. Meanwhile Winchester studied the room, trying to figure out what the layout meant.

One side was lined with shelves on which stood rows of jars containing vari-colored pellets. The label on one read: "Vitamin B Concentrate." The contents of the others were similar, though Winchester had never dreamed before there could be so many vitamins. "L2 & P1, P5 Complex" said the ticket on another jar. Another table had standard foods, such as dried beans, sugar and other staples.

"Everything but meat," commented Winchester, thinking how nice it would be to sink his teeth into a juicy porterhouse once more.

"There's meat, too," the girl told him, handing him a plate of clear amber jelly, "but I imagine this is better for you on an empty stomach. You poor fellow, you must be nearly starved."

"You don't look overfed yourself," Winchester smiled back.

Then he looked at the cupboard she had indicated when she said there was meat. She had thrown the doors open to reveal a row of small cages containing cats, dogs and rabbits—all sound asleep.

To Winchester's notion, only the rabbits were legitimate meat. He wondered, though, why they slept so soundly. The crash overhead should have wakened anything but the dead. Yet he could see their ribs rise and fall slowly as they breathed. Perhaps they had been doped for some dietetic experiment.

"Another helping?" the girl asked, reaching for the American's empty plate. Unconsciously they had eaten ravenously.

"Yeah," he yawned, lazily stretching his arms, "think I will."

She brought more food. Drowsily they ate it. Neither one knew when the candle burned out.

Winchester opened his eyes to the darkness and raised his hand to his face. To his absolute and utter astonishment, he found it entangled in a heavy growth of hair. His hand trembled as he verified a discovery that bordered on the incredible. He was bearded like a patriarch, and the hair of his head overflowed his shoulders.

He sat up gasping, struck a match and staggered to his feet. The candle of last night was no more than a blackened stump of wick. He lit another and another. The light brought fresh astonishment.

The room looked incredibly old and moldy, and stalactites the American had not noticed the night before hung dripping from the arched stones above. The stones, he observed now, were covered with heavy green moss and ferns. And, to pile surprise on surprise, so was the floor!

Winchester rubbed his forehead dazedly. He glanced at the cages of animals. Where sleek, well-fed sleeping cats and dogs had been, there were now only skeletons, or emaciated, half-mummified carcasses. Mushrooms grew on one of the tables beside the ranks of stoppered glass jars. This cavern had the look of immeasurable antiquity, and the air had the smell of cave-trapped gases that had never known the warming rays of the sun.

The American knelt beside the girl. She sprawled where she had fallen, and under her outflung arm lay the empty plate from which she had been eating the gelatine of the night before. She was alive. There was no doubt about that, but her garments had the flimsy, rotten look of wrappings from an Egyptian ancient tomb.

Nor was that all.

The oak door that gave onto the staircase was gone, except for a few soggy boards that still clung to the ancient wrought-iron hardware. Hard-packed rubble blocked the stairs. Small wonder their place of hiding had begun to look like a tomb—their burial was complete!

Only a narrow flue brought down fresh air. Winchester could make out a glimmer of green-tinged light at the top of it, but the flue was too small to admit his body.

He went back into the room and prowled among the food containers. He started to make breakfast on the gelatine stuff. But as he was about to taste it, he noticed for the first time a withered and yellowish ticket on the bowl.

Winchester took the card to the nearest light and read the dim scribble. "Lot 3133, ledger page 104." He turned the card over. On the back of it was the single word "Nein!" and a crude skull-and-crossbones. The American frowned. That was what they had eaten!

He pocketed the card and hunted for the ledger. He handled the gossamer pages gently, for fear they would fall apart under his fingers. To his delight the notes had been kept in English. On Page 104 he came upon this:

Eureka! The perfect food concentrate at last! But, alas, it is too perfect. A single grain will furnish subsistence for a large cat or a medium-sized dog for many weeks, but unfortunately the animal devotes its whole efforts to digestion. It lies stupefied as if drugged until the food has been absorbed. I must think of some way to dilute it. I have calculated that half a pound of it will sustain an adult human many centuries—perhaps five, perhaps more. What a food!

Winchester shuddered. He looked down at the girl and a fresh horror smote him. He himself was awake now—whether after months or years or centuries, he could not tell. Had they eaten the same amount? Was their rate of metabolism similar? Might the girl not sleep on for years and years to come, or whatever term it was?

He threw himself down beside her and tried to bring her to. But though he chafed and shook and even slapped her, she only stirred lightly and smiled dreamily, like a child in its cradle. At length he desisted.

He had better shave, he thought. The beard made him feel unclean. He found a pair of shears, an oft-whetted butcher knife and the scoured bottom of an aluminum pan. It was tedious and painful, but he accomplished the shave.

Digging his way up to air was a slower job. It took weeks, during which Winchester had to work mostly in the dark to conserve the few remaining candles. It was more than twenty days when finally he broke through the surface into a bright starlit night.

He hauled himself out onto the turf and drew his first breath of outside air. If the interior of the vault had been amazing, the world outside was no less so. Instead of emerging into an air-besieged German city, the American had emerged into virgin woods. It was a country of little hills, heavily grassed, and tall trees stood all about.

Winchester made a short tour of exploration close by, but saw no lights or sign of human habitation whatever. When he returned to the cavern, he sat for a long time looking at the sky.

Until the Moon rose, it looked much as it had always done. But when the Moon emerged from behind a towering oak-top, Winchester had to gasp in unstinted admiration. Whereas the Moon he had always known had been a pallid disk, featured only by craters in monochrome, this Moon was a thing of scintillating color.

It was as if it had been studded with jewels.

One crater gave off a many-faceted ruby light, another purest emerald green. Another was of the color of a prime sapphire, while over the whole surface of the globe were patches of a vague iridescence, such as is seen in fire-opals and choice moonstones. Winchester gazed and marveled.

At length he tired, and decided to go below. Tomorrow he must get up early and explore the country about him.

It was clear that the war had destroyed Munich and that it had ceased to exist as a city, but surely somewhere nearby the Germans had rebuilt its successor.

But by a happy coincidence, when Winchester went below the girl stirred slightly of her own accord and opened a lazy eye. He stood above her, holding the stump of their last candle.

She sat up, blinking.

"I think I must have fallen asleep," she said apologetically.

"I think you must have," he said. It had been three weeks since he himself had awakened.

All that time the girl had slept without moving.

"Did you rest well?" he asked.

"Oh, quite," she said, stifling a small yawn. "Do you think the raid is over?"

"Yes," Allan Winchester said, very soberly. "The raid is over."

For some reason he found it very hard to tell the girl what had happened.

Or rather, what he thought had happened. For he was not too sure that it was not all part of a not altogether unpleasant dream. Yet despite her merry peals of incredulous laughter, as if he was trying to amuse her, the aspects of the room and, above all, the gaunt carcasses of the trapped animals at last convinced her.

"So we're years and years in the future—is that it?" she asked cheerfully. "Like Wells and the others used to write about?"

"Sort of," Winchester admitted. "Only what you've read is no help. It's all woods outside, and no people that I can see. Maybe the war washed the whole world up and we're all that's left."

"Another Adam and Eve, you mean?" she asked archly.

The American blushed.

"W-well, no," he stammered. "That's not what I meant, exactly." He ruffled his hair and stared at the floor.

He felt a little out of his depth. He groped for an appropriate come-back, since she seemed to be in a light mood despite the momentous news he had given her.

"I do think, though," he managed, with a gulp, "that it is about time I knew your name. Since it is a decade or so—or maybe a century—that we've been living in this cave."

"Nonsense!" the girl retorted. "Do you call this living? But since you want to know, my name is Cynthia Schnachelbauer. My father was German. German-American."

"Oh," Winchester said, repeating the name slowly. "Sounds rather cumbersome, the last half."

"Do you want to make something of it?" Cynthia challenged, planting her hands on her hips and jutting a small jaw at him.

"I may, at that," he said thoughtfully.

Cynthia made clothes for them. The ones they had were falling apart from rot. She worked from a roll of chamois skins she found in the kitchen-laboratory. In the meantime, Winchester gathered together a pack of selected provisions. When the two of them were quite ready for their expedition, they crawled up the steps to the outside vent and stepped into the woods above. After Winchester had sealed their cave with a flat stone, they started on their journey.

Of Munich there was nothing left, or hardly a trace. The frosts of unnumbered winters and the encroachment of vegetation had thrown apart what bits of masonry were left intact after the bombers had gone. Now it was virgin forest. But beyond, where once there had been fields, the adventurers came upon an endless lawn, on which tame deer grazed and peacocks strutted.

It was mid-afternoon before they encountered any evidence of the existence of man. Rounding the spur of a low hill, they came upon a valley where the grass had every appearance of just having been mowed. Winchester stooped to examine it, for his bewilderment had been growing at seeing so many thousand acres of carefully tended lawn. As he did, his eye caught a moving object.

The thing resembled a huge tortoise, and was racing down the valley at a great clip. It had a metallic, reddish sheen, as if plated with burnished copper. It approached rapidly, and as it came, Winchester noted that the color of the grass in its wake was not quite the same as that to its right. It was a mowing machine!

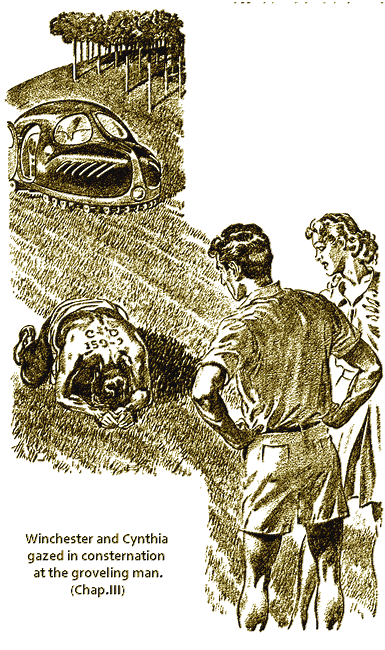

It halted abruptly some fifty feet away. A gaunt fellow, clad in a simple gray blouse and kilts of a coarse and cheap-looking material, popped out of a hatch that opened at its top. He leaped to the ground and at once prostrated himself, oriental style. In the same movement, he snatched open the back of his blouse, revealing his naked shoulders and the upper half of his back.

Since the fellow persisted in remaining in the position into which he had thrown himself, kneeling and with his face buried in the grass, Winchester and Cynthia approached him slowly. As they neared, they saw that there were symbols and numbers branded or tattooed on his back.

Winchester stared at them with a frown. What troubled him was that the figures were placed so as to be read upside down! The creature was identifying himself, and to do so he had to perform the kow-tow!

"Get up, man!" called Winchester sharply, seeing the fellow continued to grovel. "Tell us where is the nearest town."

"Ay, milord, whip me if you will, but do not mock me by calling me a 'man'," whined the operator of the mowing machine. "I am but your miserable slave. They did not tell me you were abroad today, or I would not have been so bold—"

"Nonsense!" snorted Winchester, stooping and shaking the fellow by the shoulder. "Stand up and talk face to face."

He stepped back, astonished that what he supposed to be a German peasant should speak English so instinctively. Not that it was English exactly, but a peculiar Anglo-Saxon dialect.

The man stood up, and the visitors saw he was trembling. But the moment he looked into Winchester's face, his attitude changed with startling abruptness. He dropped his whining, abject servility. In its place he registered a curious blend of rage and fright. With a bound he sprang back into his machine, screaming at the same time.

"Away! Masterless slaves, away! I have not seen you—I have not spoken to you—I do not know you!" His utterances trailed off into a wail. "Ah, why did they have to come here? Now they will punish us all!"

He slammed the hatch cover down. The machine darted forward and in a moment was no more than a dwindling speck on the distant lawn.

"That's the payoff," said Winchester softly.

Cynthia looked at him, puzzled.

"Here's a plain laborer of Middle Europe, who speaks English as a matter of course, indicating that at some time in the past the English-speaking peoples dominated this country. Yet he has the psychology of a whipped slave."

"I still don't understand," Cynthia said.

"Because we were walking boldly across what I take to be forbidden grounds, our slave at once assumed that we were of the existing master class. So he behaved accordingly."

"They must be nice people," observed Cynthia sarcastically.

"Quite," Winchester agreed grimly. "But when he stood up at my command and looked at us, he knew at once we were phonies. We are untamed slaves of his own race, not of his masters. They must be of another type altogether."

"I wonder what has happened to the world," Cynthia mused. And this time, apprehension was in her voice.

Their education was soon to begin. Unnoticed while they had been talking with the slave, a dark object had been circling in the sky above. Now it swooped, to descend at a steep angle and in a tight spiral. It was a plane of sorts, painted brilliant scarlet, but it was noiseless and apparently propelled by some invisible internal force. It made a jarless landing a dozen yards away.

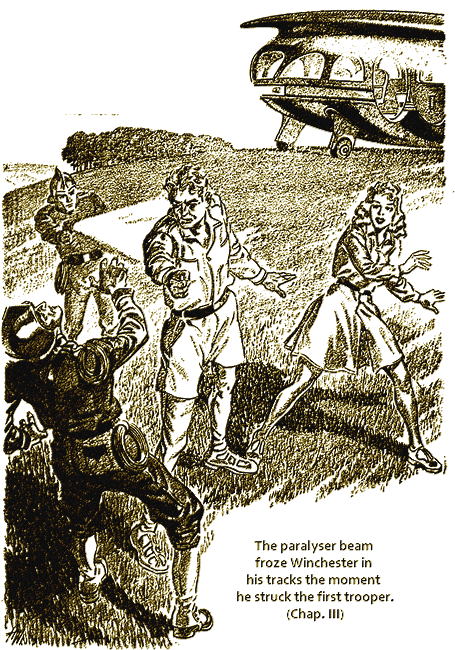

Two men sprang out. They were obviously police, for they wore trim blue uniforms glittering with gold lace and buttons. Queerly shaped weapons hung from hooks on their belts, and each wore a round leather loop dangling from shoulder to shoulder. Winchester took these to be aigulettes of some description, but he was as instantly disabused.

As the men strode toward them, they unslipped the small ends of the tapered leather straps from one shoulder, and jerked the thick ends from sockets at the other. The straps were whips!

"Down, slaves!" one yelled harshly, swinging the whip above his head.

The other already had his unlimbered, and took a vicious slash at Cynthia. The singing tip missed her face by a scant inch.

"Take it easy, you!" snarled Winchester, lunging forward.

In his sudden white rage the American cared nothing for the mysterious gadgets dangling from these men's belts. His fist caught the second trooper squarely on the jaw and the fellow flopped backward, out cold.

But the crack of knuckles against jawbone was accompanied by a soft spat! While still unbalanced from the delivery of the blow. Winchester plunged forward onto the grass, frozen into his attitude of the moment. All his muscles and bones were filled with excruciating pain, yet he was so paralyzed by the unseen, swift force unleashed by the trooper that he could not make the slightest twitch.

He felt the lash of the whip a dozen times or more; heard Cynthia's screams. Then he fainted dead away under the accumulation of pain.

He could not have been out long, but when he resumed consciousness he had normal possession of his muscles again—all except those of his arms, which dangled helplessly at his sides. He was sitting in the doorway of their captors' plane. The trooper who had knocked him out had revived his fellow officer, and the two of them were engaged in an examination of Cynthia.

"It's a good thing you didn't mark the girl," growled the leading trooper to his aide. "Prince Lohan would have busted you to a mine guard. As it is, there'll be a thousand merits to split between us for this job. She's the finest specimen I ever saw. Look! How pink and tender."

The policeman pinched Cynthia's upper arm, and was rewarded with a prompt and resounding slap in the face. But he merely laughed and held her away from him with his long arms.

Winchester looked on with burning eyes. There was cold murder in his heart, but without the use of his arms he could not rise. He had a glimmering now, though, of what the ruling race was like. These troopers were big men and blond, yet with the flat faces and almond eyes of Mongols. Somehow they combined the salient features of both Scandinavians and Tibetans.

"But unbranded Nordics?" queried the man Winchester had hit. "There's a reward for them, too, isn't there?"

Winchester noticed now that both his and Cynthia's chamois garments had been torn away, to reveal their unmarred shoulder blades.

"Sure," said the first. "They used to turn up often in the old days, but I haven't heard of one being found in years. We're in luck."

Other red planes commenced raining down. Soon the field was covered with them, as policeman after policeman came up to inspect the find. Apparently the original discoverers had broadcast the news. But no one molested Cynthia or Winchester further. It was evident they were awaiting the arrival of some higher-up.

He was not long in coming. A cigar-shaped vessel with stubby wings made its appearance in the skies. It was banded like a hornet, with alternate rings of black and gold. It made a smooth landing as had the others, and in the very midst of them.

A tall handsome man of the same Mongol-Nordic hybrid type stepped out, accompanied by another. The first was dressed elegantly in yellow silk robes ornamented with a profusion of dark jewels. The other wore yellow silk, too, but it was striped with red.

"Prince Lohan!" shouted the senior police officer, and all fell on their faces.

The kow-tow, evidently, was required of everyone. The exceptions in this case were Winchester, who could not, and Cynthia, who would not. She stood glaring defiantly at the prince who had come to look at her.

"Ah," said he presently, after inspecting her as coolly as if she had been some rare and costly species of newfound animal. "Send her to the School of Arts and Graces. Have her brought before me again at the next annual Palace competition. Dispense with her examination. I would not have her marred. We will find out what we want from the man."

His gorgeously robed companion bowed deeply.

"As for him, take him to the nearest magistrate—that will be in New Vienna. After the quiz, carry out the usual sentence for those striking one of my officers. Take care to keep him alive, though. I am curious to know where these masterless slaves come from."

Again the aide nodded. Then he made a suggestion on his own.

"And the usual roundup of your Excellency's own slaves to find out who has been harboring this pair?"

"Of course," snapped Prince Lohan.

He strode back to his ship and disappeared within. It rose at once and was out of sight in a few seconds. The motionless police kneeling on the ground rose at a signal given by the attendant whom Lohan had left behind. Winchester noticed now that not all of them were of the Mongoloid type. Many seemed normal Westerners of his own background. Perhaps not all of them were destined to be slaves.

The prince's adjutant hurled out orders. The police went into action. One drew a stumpy, conical instrument and leveled it at Cynthia. There was the faintest hint of a swift, rose-colored spark, and the girl wilted and fell unconscious. Two of the police picked her up and carried her to one of the ships.

Two others lifted Winchester and flung him into a seat, where they fastened him with a strap to keep him from falling out. In another moment the entire flotilla took the air.

New Vienna was but a village. Winchester could see it plainly as the flying machine slid down from the heights. There was a cluster of a score or more small houses nestling beside the Danube, and in their midst was one large masonry building. Before it was an empty square, and behind it another on which a few of the planes were already alighting.

Winchester's captors unloosed the paralysis that held him sufficiently for him to clamber out of the plane and walk with them from the parking lot to the front entrance of the edifice. As he rounded a corner his eye lit on the polished granite cornerstone.

The inscription read:

DEDICATED 3012 A.D.

He and Cynthia had slept a thousand years! And more, for the building was anything but new.

He was given no opportunity to speculate further as to the exact year they had awakened in. He was already up the steps and passing through the grim portals into the audience chamber of the magistrate. His examination was about to begin.

With swift efficiency the police stripped him of his chamois garment. Then, naked as he was, they strapped him into a high-backed straight chair. One trooper plunged a needle into his arm, another fastened a small aromatic capsule to his upper lip and secured it there with a sort of glue. The Mongoloid magistrate looked on with a savage scowl.

A surge of warmth pervaded Winchester's body. He felt a sudden inexplicable yearning to tell these people everything he knew. They had only to ask. But as if to make assurance doubly certain, another trooper stepped up and touched his neck with a slender silver instrument.

At once the courtroom seemed to burst into a million blobs of fiery light. An unbearable agony racked Winchester's whole being. Despite his efforts to suppress it, he screamed wildly, wishing only for sudden death.

The policeman withdrew the glittering point and the pain ceased as suddenly as it had begun. He stepped around before his prisoner and scrutinized his eyeballs. Then he turned to the magistrate.

"Ready, Excellency. The anti-inhibition serum has taken hold, and he absorbs the sensory stimulant well. His magnification of pain is enormous, and he can stand any amount of it without fainting. Will your Excellency please to proceed?"

"Where was your last hiding place, slave," asked the judge harshly, "and how long were you in it?"

"A cellar under the ruins of Munich," answered Winchester in a dull monotone, "since the year Nineteen forty-one."

"Rebellious fool and liar," snarled the judge. "How dare you address the court with such flippancy? There is no such place as Munich. It is now eighteen hundred and seventy-nine years since the birth of our glorious hero-conqueror—the Great Khan Ghengiz, our god and founder!"

At a motion from the magistrate the policeman gestured with his silvery instrument. He touched it lightly to Winchester's left shoulder, then drew a line straight down to the wrist. The sensation was exactly that of having a red-hot knife plunged into the deltoid muscle and then drawn along the bones, splitting the arm downward. Yet the point left no mark, and the excruciating pain vanished as soon as it was withdrawn.

Winchester tried desperately to concentrate on mental arithmetic. He remembered vaguely that Genghis Khan had flourished about the year 1200. That and eighteen hundred seventy-nine brought the total to somewhere above three thousand. It confirmed the date he had seen on the cornerstone. His sleep had been for more than a thousand years!

But his mind could not blank out the agony of the fiendish torture now being inflicted upon him. Cold sweat stood out on his taut muscles. The magistrate kept up his merciless questioning while the trooper drew quick, searing lines across the hapless prisoner's torso. Yet, despite his anguish, which drove him to attempt any answer that might be pleasing to the judge, Winchester could only stick to his story. The truth-compelling serum was too much for him.

"Bah!" snorted the magistrate at last. "He is a hard one. It is too bad we cannot give him the second degree, but Prince Lohan has ordered he be kept alive. Take him to the Moon. We'll let him cull meteors for a year or two. Perhaps by then he'll talk. Next!"

The next was a miserable group of slaves, similar to the one who had operated the lawn-mower. In fact, the unhappy wreck of a man was one of them. But there was one slave who did not fawn and cringe. He was a tall, bald old man with a piercing eye and a patriarchal beard. He bore himself with an air of authority and dignity in striking contrast to the cheap slave's garb he wore. He stepped without hesitation before the magistrate.

"Excellency," he said, tapping his forehead with a finger, "my grandson is one of the weak-minded. It is for that reason that I have kept him hidden since babyhood—and his sister. It would have brought shame upon my household."

"Ha!" exclaimed the judge. "Shame on a slave's household—how droll!"

The old man stared back at him in patient dignity.

"These other men of my community, of which his lordship was kind enough to give me the sub-mayorship, have known nothing of my deception. They are innocent of wrong-doing. The fault is mine and mine alone."

"It matters not," cried the judge harshly. "The law of the Khan is just. The law of the Khan must be obeyed! The rule is that wherever an unbranded slave is found, the headman of the village and every tenth man in it shall be doomed to hard-labor on the Moon. Your effort at evasion is of no avail. Officer! Take them away."

Never would Allan Winchester forget his cruel examination. Nor could he rid from his mind the sentence he must now serve.

The forehold of the prison ship was a dreary place. The twelve condemned ordinary slaves of the Lohan estate sat on hard benches and stared stupidly at the floor.

Presently the aged patriarch spoke to Winchester.

"You wonder at my seeming sacrifice, my son? I did it, not for you, but for these poor villagers of mine. I preferred to lie while there was yet time."

"I see," said Winchester. "I'm sorry I brought this on you. I did not know."

"It does not matter," said the old man with resignation. "I have lived enough. Too long. Of all these I am the only one who knows and remembers the wonderful days before They came."

"They?"

"Yes. The rulers, these men from the plateaus of Central Asia, who wormed themselves into places of power and then betrayed their trust. Until then we had enjoyed ten centuries of peace and civilization; we had evolved a veritable Utopia. There was no strife or ambition, except for the better good of all. There was enough for everybody and to spare, while each man did what he was best suited for and received what he needed for his health and happiness.

"We perfected interplanetary travel and colonized and developed the distant bodies. We moved all our machinery and heavy industry to the Moon, where people worked a short term each year, then returned to Earth to enjoy their leisure period. The Earth then, as now, was a garden, except that it was for the use of all, not a small, self-chosen few."

Winchester's face was puzzled.

"But why," he demanded, "did so many yield to the few?"

"Because," replied the old man sadly, "we did not know how to defend ourselves. There were no weapons. For many generations the doctrine of brute force had been held to be abhorrent. Consequently, when this new breed of conquerors arose, we were caught by surprise. They were a small group, never quite assimilated to the single race that is now a blend of all those that existed before."

"But again, why?" insisted Winchester. "If conditions were so perfect, why should anybody rebel?"

The patriarch's eyes became sad and dispirited.

"There was a Mongoloid by the name of Hanu Sho-Tang, who had an overweening ambition and an imperious will. He was an able man, and had advanced to be the commander of a large spaceship, but the Regents of Transportation judged him to be unfit for further advancement—he was too dictatorial and harsh to his subordinates to fit our system.

"So he sulked and schemed and sowed discontent among those of similar disposition whom he knew. Above all he read. There were history books then—it was not until he became the Khan that he had them burned."

The patriarch pronounced the title almost in a whisper, and glanced anxiously about him. But none of the other slaves were attentive. They merely sat in stupid despair. He went on.

"He came upon the old histories of the distant past, when there were separate nations and men fought bloody, useless and inconclusive wars. He found the biography of a cruel conqueror named Genghis Khan, and the life-stories of other would-be conquerors—such ineffectual imitators as Napoleon and a creature called Hitler. From your testimony in court, that man must have been about your time."

Winchester nodded with a gleam in his eyes.

"The Mongoloid absorbed the philosophies of those men. He declared himself to be the direct descendant of the original Great Khan, and began to spread his doctrines. His own kind accepted them eagerly, and I am ashamed to say, so did many of our own race. It was easy after that for them to seize the supreme power."

He stopped talking and stared out the port.

"There is no hope," mumbled the old man brokenly.

"There is always hope!" said Winchester fiercely. His eyes lit up with the fire of resolution.

He felt a gnarled hand seize him, and was surprised at the warmth and vigor of its grip.

"Ah," said the old man. "If I were only young again!"

"Be young in spirit, then," Winchester challenged. "We shall have work to do!"

He thought of Cynthia then—Cynthia, a slave girl. The blood rushed angrily to his face, and he had to clench his fists to keep them quiet.

The area below was vast, and at first sight featureless. It was one of the tracts of the Moon known in the old days as "seas." But as the spaceship prison van approached nearer, Allan Winchester saw that the plain was pimpled over with small hemispherical mounds. Each was ringed with a faint aura of greenish light and connected with neighboring mounds by other slender beams of the same pale rays.

For awhile the ship approached no closer, but spiraled about the Moon as she lost velocity. The convex line of the horizon rolled slowly toward them, as if the Moon was a gigantic ball turning ponderously over. A string of immense craters came into view, and their slopes were studded with hundreds of minor ones.

Winchester saw that many were domed. He understood then why it was that when he had first seen them from the mouth of his cave in Munich, the satellite had appeared set with sparkling jewels. For the domes were of all shapes and colors, some spherical, some ellipsoidal and others polyhedral, showing many glistening facets.

"That is Tycho," pointed the old man to one larger than the rest, crested with a translucent dome that shimmered like polished mother-of-pearl. "In it is the great city of Cosmopolis, the largest in the System. There are the dormitories of the industrial slaves, the textile mills and many machine shops.

"The variegated colors show where the foreign quarters are, where the Martians and the Venusians live, and so on, each under his own planetary conditions. Beyond it, on that pinnacle, is the Great Observatory, one of the five located on the Moon."

"How do you know these things?" queried Winchester.

"I served here for thirty years," sighed the patriarch. "When my strength and skill failed, they reduced me to a domestic slave and sent me back to Earth to be headman of Prince Lohan's cattle herd."

The ship headed down into a vast, undomed crater. There were many spaceships of various size squatting here and there on its bottom. Ungainly, high-wheeled vehicles were to be seen crawling to and from them. What appeared to be row upon row of iridescent soap bubbles, clinging to the base of the ten-thousand-foot cliffs that ringed the landing field, proved on closer approach as many small domes.

"Grand Central Station," explained the aged headman. "The huge interplanetary liners take off and arrive here—the gravity is so much less than on Earth. Passengers from Earth come over on small ferries like this one. Freighters have a port of their own, near the mining and smelter craters, and the Space Fleet uses the Military Base in Proclus, where the Academy and the Grand Arsenal are."

His words were cut short as they were hurled against the glassine visiport by the sudden increment of deceleration. For a moment Winchester was too dazed to see anything clearly. When he looked again, the prison van was gliding to a smooth stop not far from a grim, gray dome. At once, one of the awkward, high-wheeled buggies slid out of a portal in the dome's side and rolled toward them.

"A ground tender," grunted the old man. "Saves putting everybody in space-suits. There's no air out there."

In a moment two guards came in, ray-guns drawn and in hand.

"Fall in, slaves," one cried. "About face! March."

In double rank the condemned slaves shambled ahead into a corridor, turned a corner and went through the ship's lateral spacelock. Coupled to it was a bridge leading to the wheeled tenders. Winchester and the aged patriarch brought up the rear, doors clanged behind them. The tender lurched and rumbled off, its wheels bumping grittily over the irregular crater bottom.

Winchester cast a look about the chamber he was now in. It was cubical, all steel. There was no opening whatever, except the now closed outer door by which they had come in, though there were small lenses set in the plating of the polished wall opposite. These were probably peepholes through which the prisoners could be watched or counted. There could be no escape.

The van jolted on, then stopped jerkily. The clang of interlocking metal broke the silence. Then the door slid back again, revealing a short, arched corridor, lined with guards.

"Single file, swine," bawled the nearest trooper. "When you come to the sacred mark in the pavement kneel and show your marks."

The leading peasant shuffled forward, his shoulders stooped and his dull gaze fixed on the pavement a yard ahead of him, as was required of slaves. The rest of the poor wrecks followed. As they reached the place where a golden sunburst was embedded in the concrete floor, each paused and made a kow-tow, while a policeman noted the symbols on his back and checked them against his list.

"Hey!" yelled the recorder, on examining the third one. "Whoever put this guy's marks on did a sloppy job. Touch 'em up—make the figures more distinct."

The entire line was halted while the wretch was dragged out and strapped, moaning, to a crosslike structure of steel in a niche. He faced the wall while the guards brought up a machine mounted on a rolling tripod. The policeman consulted the record, set certain knobs, and focused. He tripped a switch and lavender fire flashed out of the brander, retracing the faded distinguishing numerals.

The man screamed once, then dangled helplessly in his bonds. Winchester saw and sickened. He had no brand as yet. If he was to escape, it was now or never.

He waited until it came his turn to kneel and bump his face to the sunburst set in the floor. Until that instant he had imitated the slovenly, hopeless shamble of the beaten slaves ahead of him. But out of the corner of his eye he had stolen glimpses of the guards about him. They were lolling contemptuously against the wall, serene in the belief that these trapped creatures were so spineless that they could be trusted to follow the routine like blind sheep.

Allan Winchester went into action like a springing leopard. He jerked up his head, saw at one swift glance that he was on the threshold of a vast circular open space on the order of an ancient coliseum. Groups of gray-clad slaves huddled in spots on the sands of its floor. Many doors led off it, and only a few were visibly guarded.

Winchester sprang sideward, snatching the weapon from the surprised hand of the guard that stood nearest to him. With a bound he leaped past and into the arena, then turned sharply and ran along one of its curving walls.

Shouts rose behind him, as the startled guards comprehended that a slave had been so audacious as to break out of line, snatch a gun and run away. Winchester heard the faint spatting of deadly rays. Violet streaks of light hurtled past him and ricocheted from the stones ahead, leaving mushy-looking incandescent spots wherever they hit.

He ducked low and dodged into the first door he came to. An astonished guard, who had been sitting on a stool just inside the arch, half rose, only to be butted sprawling as Winchester, still charging head down, collided full force with him.

Winchester staggered five strides beyond, then recovered his balance and sprinted on. He barely made the turn ahead, when once more the hissing streams of electronic fire came lashing after him. Before him lay a maze of twisting passages, along which were closed doors. He dared not stop to test any, but dodged onward, ever turning just ahead of the hot fire of his pursuers.

Gongs began to ring and sirens wail. A new guard jumped out into the passage dead ahead of him and leveled a weapon.

Winchester checked his headlong flight and slid to a stop, jerking to one side, just as the guard pulled his trigger. A flash, much like that of a single bolt of lightning, flared through the spot he had just side-stepped, spent itself against the wall at the far end of the corridor with a spatter of blinding light and an ear-splitting crash. Fervently hoping that pressure on the trigger was all he needed, Winchester lifted his own weapon and pointed it at his adversary. He squeezed.

Involuntarily he closed his eyes, for the effect was blinding, almost stunning. He blinked them open. There was nothing ahead of him, except a wreath of acrid smoke and the charred stumps of two shins sticking up out of a pair of boots. The rest of the guard had disintegrated!

Winchester shuddered and ran on, clinging lovingly to his weapon. It gave him an assurance he had not had before. He turned more corners but though the gongs kept on clanging, no one else appeared to halt him. Finally, winded and panting, he stopped to take stock. He realized suddenly that for some seconds now there had been no avenging pursuers behind him. That realization, instead of being cheering, somehow seemed ominous.

The gongs that had been ringing abruptly ceased. A new set of a different tone clanged twice, then went silent. Down the corridor a red lamp in a socket blazed up, winked twice and went out. Winchester did not know what these new signals signified, but he took the first turn and began to run again.

Then violent and numbing pain seized him. He gasped out one strangled moan and fell. Then he knew he was lying there rigid, struck down by the same sort of force that had laid him low when he met the first policeman. He was paralyzed. Helpless. He listened, expecting to hear onrushing guards. But to his ears there came no sound.

He was down, frozen, pinned no doubt by an ambush ray. Perhaps no one would ever come. Why should they? What worse could they do to him?

When Allan Winchester came to his full senses again, he was sitting in a relatively small room on a bench. Other men were there with him, but for awhile he was too sick and dazed to notice them.

It had been a fiendishly cruel twenty hours or so since they found him and bore him off to the torture chamber. First they had spreadeagled him face down and applied his distinguishing numerals, which in itself had been an ordeal of the first magnitude.

After that they had submitted him to the same torture given in the courtroom at his first hearing. When they had tired of that, they subjected him to yet others—all different, and all unbearable.

Now he sat waiting dazedly for whatever was to follow next. Presently he was able to take more notice of those about him. They were men like himself, non-Mongoloids, or of the slave class. But they were quite different from the spiritless creatures who had been his companions on the trip from New Vienna to the Moon.

These men swaggered and boasted and gloated over their "crimes." They, evidently, were high-spirited men and unbreakable short of death itself. Indeed, Winchester later came to know their designation, as well as his own. They formed the fast-dwindling rearguard of individualism. They were known as the Incorrigibles.

One came over and examined Winchester's raw back. It was easy to do, for none wore more clothes than a simple canvas girdle.

"Aha, fellows!" he shouted. "A new member for our club. See, he's been awarded the Red Star, and his number is higher even than Teddy's."

To show Winchester what he meant, he turned his own back and displayed his markings. Surcharged over the faint bluish script that made up his personal designation was a glaring crimson star and beneath it a numeral, also in red.

"Super-criminal, that means," the fellow grinned, turning back. "My name's Heim—ex-chief chemist of North American Plastics. I had a good job for a while in the labs in Copernicus, but they jugged me time after time for minor nonconformity. Finally I burned down an AFPA man and they hung the Red Star on me.

"But what the devil! Let 'em do their worst. I'd rather have it that way than go to their confounded Crater of Dreams and work for them for the next half century!"

"Sh-h-h, you fool!" hissed another. "Don't you know they are listening? Or do you really want to go to the Crater of Dreams?"

"Maybe I do," said Heim mockingly, "and maybe that's my play. Let's see if they are clever enough to work it out." He winked at Winchester.

Winchester grinned back. He liked the fellow, though he had little idea of what he was talking about. The man stood before him, cheerful and unsubdued, notwithstanding the hard lines on his face that told all too plainly that he had suffered fiendishly contrived tortures.

"You're way ahead of me, boys," Winchester managed painfully.

He suddenly discovered that his jaws were nearly locked as the aftermath of a certain treatment called by the guards the "Q-27." In the kaleidoscope of torture, he had forgot the one which seared the tongue and made every tooth ache abominably.

"But," he went on, "I'm one of you. Where do we go from here?"

Heim shrugged.

"You never know. They like to play with you cat-and-mouse style. But I can tell you one thing. Making a break like you did the other day won't buy you anything. They always get you in the end. Every few feet along these corridor walls is a concealed paralysis-ray projector, worked by distant control.

"Guards and trusties are warned by signal lights and gongs. They step clear and wait, while we poor devils rush right into the rays. After that, it is easy to pick you up and give you the works."

"I see," said Winchester, realizing how futile his break had been. At the same time he drew a grim satisfaction in recalling that he had cut one of the scoundrels down.

Presently guards swarmed in, alert and vigilant, for they knew the desperate type of men they had to deal with.

"Okay, you hard guys," said the leader, "on your toes. We'll give you a chance to work off some steam. Fall in, single file."

They went to the meteor fields in the airtight buggies used to convey air-breathers across the undomed areas. There were many stops as they came to the barriers formed by the pale green horizontal rays. At making certain code signals, the ray disappeared long enough to permit the cart to proceed and then showed up again behind it.

"Force walls," whispered Heim into Winchester's ear. "They are impenetrable and burn like fire. The whole plain is crisscrossed with them and each slave hut is surrounded by them. It is their control system and unbeatable."

Winchester looked out glumly, but with deep interest. He counted the barriers they crossed and noted there were more than twenty. In between lay wastes of cracked and shattered granite bedrock, strewn with gravel and metallic boulders. He saw many lines of rails with small flat-cars standing on sidings, and once he noticed a group of slaves laboriously pushing one that was piled high with meteoric matter.

At length they came to a heavily armored dome in the midst of the field. There the cargo of fresh human victims was unloaded. In the grueling days that followed, Winchester came to learn the system well.

Each dome held dormitories and kitchens for the slaves, and guard rooms for their supervisors. In the center of each was a huge hopper into which the flat-cars were dumped. Winchester was given to understand that the hopper fed the loads to a subway freight system, connecting all the domes and the smelters beyond the field. The domes themselves were surrounded by rings of force, which were only broken to let the cullers in and out.

As for the cullers, the rule was simplicity itself. They were sent out in groups, unguarded, clad in armored suits containing water and air enough for twenty hours' operation. If, within twenty hours, they brought back as many tons of ore, they were admitted to the dome and given food and rest, then sent out again. If not, they stayed outside to die of asphyxiation or thirst.

When the sun was shining, the plain was blindingly bright and searingly hot. When the sun was on the far side, all was bleak and bitingly cold. And unceasingly the cullers were subjected to the hazard of pelting meteors, which fell with terrific velocity and usually burst into a thousand hurtling fragments on impact.

"You see," explained Heim one day, "the whole set-up of these fields is to protect the domed craters. There are towers set at strategic points, which set up magnetic strains in the void overhead, attracting all the loose stuff to these chosen areas. The meteor falls are so heavy and so constant, these areas would soon be buried deep unless the fragments were continually picked up and carted away.

"Our rulers combine the need of doing that with punishment of criminals, so they send us. The mortality is terrific, but who cares? There are plenty of us. Besides, they get quite a lot of valuable by-products, such as platinum, iridium and diamonds."

Winchester gritted his teeth and hung on.

One night, after a quota haul done in less than ten hours, he and Heim and others were gathered around the mess table, singing. A former spaceship hand had made a guitar of sorts out of scraps of wood and bits of wire, and it was he who strummed the accompaniment.

The gaiety was forced, because all were dead tired, but they acted their parts vigorously, knowing that it irritated the guards to see any reaction but cowed misery.

Heim would lead off, and all would join in the refrain, thumping merrily on the table.

Oh, have you seen my Martian love, The one that is so sweet? She's feathered like a turtle-dove With pseudopoda for feet. Oh, she's grand, she's tops, she's neat, She's a monster, sure—but awfully sweet! Oh, have you seen my Martian girl, The one that is so fair, And note how quaintly her antennae curl, How wondrous green her hair? Oh, have you seen my Martian maid, The one I love so well? Her snout plates are of purest jade, To match her tummy scale.

They all jumped up and did a snake dance around the room, bellowing out the refrain while amazed guards looked on. A petty officer quietly sneaked from the room, a worried look on his face. The next stanza was led off by Winchester.

Oh, have you seen that Martian lass, The one who drives me wild? Her breath is purest methane gas and leaves me quite beguiled. Oh, have you seen my Martian belle, The one with the lidless eyes? It's true she cannot kiss so well, But—golly, boy!—she tries! Oh, she's grand, she's tops, she's swell, She's a monster—

Suddenly the clamor of a gong drowned the song. A door slid open and a fully armed captain of the guards stood on the threshold.

"We have been watching you men," announced the guard captain, after an ominous pause, "and it appears we have been too easy on you. I have reported the matter to the Commandant and he agrees that other duty is in order. The van is at the portal. Fall in—and stand at attention! As your numbers are called, step forward."

No inmate of the ferrous industry's big No. 4 plant ever saw the massive dome that covered it. All one could see, looking upward from the grimy crater floor, were rolling clouds of sulfurous smoke lit by the glare of blast furnaces, or the riotous shower of sparks as some ingot mold overflowed.

Gigantic rollers flattened out the white-hot billets fed to them, or squeezed them into strange shapes. The place had a strong flavor of the Inferno of the ancients, and the illusion was completed by the occasional glimpse of half-naked, sweating men tending the hot machines.

These were the condemned, and perched in elevated nests about the place were the demons—the ever-present slave guards.

Winchester had a place in it. Stripped to his loin cloth, he tended a huge stamp that pounded and roared, crushing the endless stream of iron-oxide brought to it by a conveyor. From the stamp the rusty fragments flowed over sorting screens, and then fell into squat gondolas crawling along on the tracks beneath.

From time to time a ponderous, atomic-powered locomotive would come and drag away the loaded cars. For days Winchester watched the spectacle in dull wonder. Iron-rust deliberately produced in oxygen furnaces and exported by the millions of cubic yards! And this in a place where virgin metallic iron could be had for the picking up, and oxygen literally worth its weight in diamonds!

Something nudged Winchester, and he heard a shout in his ear.

"Let that go!" yelled a guard, cupping his hands to make himself heard above the din. "Get down on the floor—a new detail for you!"

Winchester nodded and dropped the wrench he had in his hand. He had learned the folly of resisting every little order. He must save his fight for the really big issue that was sure to come. That is, if he could only stick it out long enough.

He clambered down the rickety ladders to the cinder-strewn floor. A three-hundred-car train of loaded cars blocked any further movement except along the track. Another guard jerked a thumb and Winchester turned in that direction.

Hundreds of feet along, he came to another group of guards standing beside what proved to be the last car of the train. They motioned for him to climb its steps and enter. He did, and noted with mild surprise that its doors were fitted with gaskets and holding-down dogs, and that the car windows were similarly equipped. In fact, the caboose had more the appearance of a ship's compartment than of a railroad coach.

Winchester settled himself without a word on one of the longitudinal benches. There were other convicts with him—red star men, all—but none he knew. They were big huskies and apparently inured to hard labor. Bundles of short-handled scoops tied with wire filled the rear corner of the car.

Presently a guard came in and closed and sealed the doors and ports. The train slowly started off. It proceeded a little way, then stopped. After that it went on, but in utter darkness, until after a time it emerged into the brilliant light of the sun-flooded Lunar plain.

"A life-size airlock, that," commented one of the prisoners.

"Yeah," agreed the man next to him. "Smack through the crater rim. Wonder what's up?"

"Dunno. Heard something about their building a new Martian Embassy over in Sevinus. His nibs, the ambassador, gets homesick for his deserts. That's what all this rust is for, I think. It costs plenty, but what of it? He's got it. Married a sister of that slant-eyed Prince Lohan, I hear—"

"Pipe down, you two," snarled a guard, and the conversation stopped.

The train skirted the plain, which was evidently one of the meteor-bombarded areas, then crawled through foothills of small craters. It came in due course to a steep mountain and entered a deep tunnel. Again there was darkness and a long stop. The guards undogged the ports and threw them open. Winchester took a deep breath of the new air and found it mildly exhilarating. It was thin and dry and also cool.

An ex-spaceman sniffed knowingly.

"Yep. It's Mars, all right."

When the train came out into the crater itself, Winchester's surprised eyes were treated to a sight he had often dreamed of in his earlier existence, but never thought he would live to see.

The dome-workers had done their job and gone. Overhead was what looked to be a dusty, dirty-greenish sky; and through some trick of refraction, the oversized Sun of Luna had been reduced to the hazy, dimmer spot of light it seems to be from Mars.

The crater floor was already covered for miles with leveled iron-rust. It shimmered with the ruddy, characteristic color of the fourth planet.

Further on they came to mounds and dumps of rust which had not yet been spread. Slave-operated tractors were at work, dragging it away with giant scrapers, and supervisors carrying photographs were showing them where and how to shape it into the mounds and hummocks that abound in the Martian desert.

The work-train pulled on beyond a little way and then began to dump its load. Off toward the center of the crater, Winchester could see a group of pyramidal stone buildings crawling with workmen. That, he presumed, was to be the new Martian Embassy.

"Don't need any more spreaders," said a guard, coming up. "Take these guys over to the West Portal and put 'em to work there. A shipment of stuff is due from the Botanical Gardens and is gotta be planted around. Tricky things, them Martian plants—you always wind up with less men than you started with. So be sure you put your tough eggs on the job, men you won't mind losing."

"I gotcha," said the train guard, grinning. "Well, they can have this whole lot and never squeeze a tear out of my eye." He turned to his charges. "Come on, you bozos. Pick up those shovels and march. We're legging it across to the other side."

Hours later the dusty convicts were brought to a weary halt beside a string of flat-cars.

"Here you go," said a man, coming out from behind the cars.

He was tall and thin, wore horn-rimmed glasses and looked more like a college professor than conductor of a work-train. He was not a Mongoloid, but he bore himself with authority.

"Thirty choice Martian phygrices here. They go into those holes. Handle 'em with care, they're man-eating. But whatever you do, don't burn one down. Those are strict orders from the Director himself. They're very valuable and rare specimens."

He poked a receipt for the plants at the convict guard.

"Sign this and I'll go on back to the Botanical Gardens and send up some moss. In an hour or so you'll get a train of desert goats. Feed them to these plants after they're bedded in. Two goats to a phygrix is about right. S'long."

He pocketed the signed receipt for the cargo and swung himself up into the cab of the waiting locomotive. Winchester looked from him to the boxed plants with interest. Each plant bore a sign.

MARTIAN PITCHER-PLANT.

Dangerous!

Handle With Caution.

"What's dangerous about 'em?" asked a convict.

"How do I know?" replied the guard. "Watch your step, that's all. Grab a couple of loose rails over there and let's skid 'em onto the ground and have a look at them."

Winchester examined one of the plants after it was on the ground and unboxed, but he failed to see anything hazardous-looking about it. The thing had a fat, bulbous root some ten feet in diameter that was covered with a leathery skin. Its upper part consisted of a number of fleshy leaves of from six to eight feet in length, temporarily bound together with turns of wire rope.

The gang slid them one by one across the gravelly waste, and lowered them into their holes. By quitting time the entire thirty had been transplanted and the backfill done. Winchester and another man began taking the ropes off the bound leaves. "Hold on," he warned, as he loosened the last knot. "Let's get out of reach before we unwind them."

He jumped back a good ten feet, holding the stray end of the line in his hand. For being so close, he could not miss the fetid breath of the thing, knew without doubt that the plant was carnivorous. But at the same time, Winchester thought he understood its method of attack.

Each of the fleshy leaves terminated in what was the caricature of a human hand. A tough, horny palm divided on one side into three muscular fingers. Growing out of the other side was an opposed thumb.

As the bonds were loosened, the fingers and thumbs kept opening and closing spasmodically, and tremors could be felt running up the leafy arms.

From the safe distance where he stood, Winchester began hauling the slack line to him and making it up into a coil. Meanwhile, the released leaves began to weave about and thresh the air, as if warming up after their long confinement.

"I'd hate to have that thing grab me," remarked his fellow convict.

"Yeah," agreed Winchester, looking dubiously at the menacing clump of leaves.

He was wondering how a plant that smelled so vilely could induce any living thing to come within its reach. An ambush as obvious as that of the phygrix seemed to him to be a poor one. He would have thought nature did things better.

Winchester retrieved and coiled all the line and turned to walk away. Down the track, he noticed that most of the other plants had been untied and the convicts were moving back toward the train. Apparently all had seen the danger as quickly as he had, for there was none of the excitement that would have been attendant on the struggle of one of them with a clutching phygrix.

Something whizzed by the American's head, narrowly missing his ear. Then another, and another. A heavy stone struck him sharply between the shoulder blades and he stumbled and fell.

At the same time, a veritable hail of gravel and small rocks began pelting the ground all about him.

He scrambled to his feet, saw that his companion was down and unconscious, bleeding from a deep cut in the head. He picked him up and staggered on a few paces, then went down himself, struck from behind again.

Winchester was unconscious but a moment. He blinked and pulled himself up to a sitting posture. For the first time, he saw the source of the barrage of missiles. The pitcher-plants had gone into action! Their hand-tipped leaves were wildly swooping and grasping the small stones that lay near them. They hurled the stones with deadly accuracy at everything in the vicinity that moved.

From the inner recesses of the plant cluster, slender, slimy antennae snaked out. These were long—sixty feet or longer—and while some retrieved and brought back the hurled stones for further casting, others groped the ground for unconscious victims.

Winchester was appalled to see one of the feelers wrap itself around the form of a convict off to his left. He turned his head quickly, just in time to see another of the antennae slithering toward him.

Dizzy and bleeding though he was, he managed to stagger to his feet, with his companion's body thrown across his shoulder. He must have made another ten feet of retreat good when one last well-aimed stone brought him down. Things in his vision swirled madly a moment and then went black.

The clickety-clack of wheels on rail joints was the first sound Winchester recognized. Then he knew he was lying on his back on one of the benches in the caboose. He heard the low voices of grumbling convicts.

"The dirty heels!" one was saying. "They wouldn't pull a trigger to fry one of those plants, but they'd burn us down as soon as look at us. 'Valuable plants,' the rat said, 'strict orders not to hurt 'em.' Huh!"

"How many guys did they get?"

"Six. And there woulda been two more if this fellow didn't have what it takes."

Winchester opened his eyes. The bruises and cuts smarted, but he sat up. Someone had put crude bandages on him, after dragging him out of the reach of the pitcher-plant.

"Where to now?" he asked.

"Central Receiving—same place you landed when you first came out. It's close by and a handier place to lock us for the rest period than to put up camps in the desert. Oh, we'll be back. There's more funny stuff to be planted in that crater before his nibs, the Martian ambassador, thinks it looks like Home, Sweet Home. Not only plants but animals. Like neuriverons, for example."

"Neuriverons?"

"Yeah—Martian thrill-suckers. A kind of mosquito. It's what they call 'analectric.' That's the opposite of electric. Instead of giving off current, they live on it. They're tough on exposed wiring, and can drill anything but armored cable. They like human currents, too—that's why they call 'em neuriverons.

"A cloud of 'em will pester you, buzzing and stinging, until you get fighting mad. Then they close up and sink their drills into you—into nerves, if they can find 'em. Ten or twelve will drive a man into fits. Some people go stark crazy. A comfy place, Mars is!"

But Winchester learned no more about Mars that day. The train was slowing for the airlock. In a few minutes he would be back at the place where he first started as a branded criminal.

A gate guard checked off each man as he entered, and another handed each his ration for the day—a greasy black pellet compounded of just the food elements needed, and no more. This and an occasional swig of synthetic water was all the nourishment a convict rated. In the hydroponic gardens of Hipparchus, they said, vegetables of every sort grew profusely. But these were for the masters.

The detail filed on into the circular open space under the main dome and threw themselves down on the sand. They could sleep or rest so many hours, then their trick would go on again. Winchester was glad to notice his friend Heim, squatting in another group not ten yards away.

"How ya doing?" grinned Heim, looking at the American's bandages.

Heim held out his own hands for exhibition. They were stained to the elbows a brilliant, bilious green. Winchester took a look around, saw no guards were watching, so he rolled across the intervening space and joined his former gang-mate. For an hour they chatted, comparing notes.

Heim was working at the quarantine station. For a week he had been dipping Uranian trabblenuts in a strongly antiseptic fluid, so as to rid them of the dangerous mold spores originating in that far-off planet. Due to some peculiarity of the trabblenut's shell, it was a job that had to be done by hand. An interplanetary fruiter had just brought in ten thousand tons of them.

As they talked on about various topics, Winchester learned more details of the warped civilization into which he had blundered. All his race, for one thing, were not slaves or convicts by any means. There were many classes and gradations.

In Cosmopolis, the industrial center, nearly all the key posts were held by Westerners. They lived on a decent scale, and the more important of them were even allowed a domestic slave or so. From the so-called "free labor" class, up to the superintendents, men were holding the same jobs they would have held before the Mongoloids took over.

"The difference is," explained Heim, "that our fathers worked only a tenth as hard and got more for it. But in those days, they produced the necessities and common luxuries, not the useless expensive things these present-day rulers want. Imagine having an embroidered carpet a mile square made for use at a single garden party, to be burned afterwards because it is soiled with spilled wine and food!"

Winchester growled softly.

"Of course," Heim went on, "there is still plenty of useful work done. For that even the Mongoloids need technicians, so they let people of that class pretty much alone. That goes for scientists and a lot of other specialists. The rule is that if you are useful to them, you get by. You could get out of here in twenty-four hours if you would play their game."

"Like what?"

"Turn stool, if you can't do anything else. A lot of these guards got their start that way."

"When I sell my soul," said Winchester, "it will be for a better price than any you've mentioned."

Just then there was a commotion at the outer door. After a moment's delay, a strange-looking group of men was brought in and led across the arena. They were accompanied by guards, but it was plain to see that they were not slaves; nor did they have the hard, strained look of convicts.

Moreover, most of them were richly dressed. Their costumes were of gay-colored silks and satins, in many cases embroidered with gold lace. They staggered as they walked, as if slightly tipsy, and here and there a solicitous guard offered a helping hand.

"There is still another class," whispered Heim, pointing. "These are artists. That fellow in the white velvet is a great composer. The guy directly behind him is a poet. The rest are sculptors, dramatists, novelists and such. For one reason or another, they are washed up and through with conscious life.

"They are on their way now to the Crater of Dreams. They will never work again, but from now on will live in a golden haze created by their own imagination—maybe for years and years."

Winchester looked puzzled.

"It's the dope-pit they're going to, to put it another way," Heim explained. "A place filled with wild Venusian Lotus. Lotus fruit will keep a man alive indefinitely, but its fumes are maddening. Once a man has been exposed to it, he becomes an incurable addict. After that he only lives to dream.

"Look!" Heim exclaimed a moment later.

Now the intellectuals were retracing their steps to the port by which they had entered. But whereas they were bareheaded when they first came, now each wore a gleaming helmet. The metal covered only the top and back of the skull. A metallic chin-strap held it on, leaving the features uncovered and free.