RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Amazing Stories, July 1940 "The Monster Out of Space"

This was no planetoid wandering in the void. It was a living monster, threatening to eat whole worlds. Could Berol's science stop it?

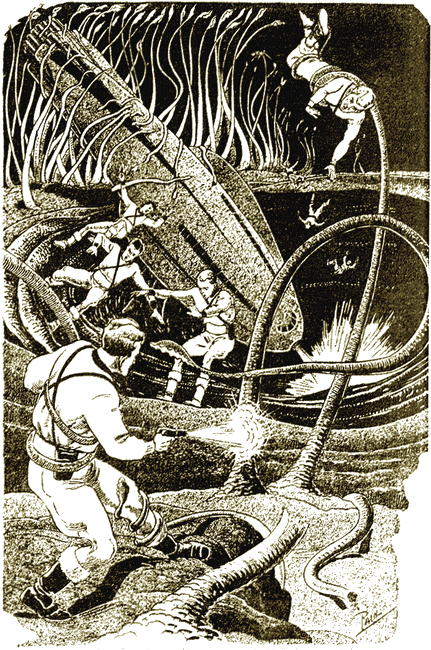

In an instant the surface of the world-monster

was a living hell of action and death.

"GRAB something, folks, and hang on. I'm putting this little packet down on her tail!"

Bob Tallen shoved home the warning-howler switch, pushed the intership phone transmitter away from him, and jabbed the ignition control for the reversing tube.

Before the blasts fired, he threw two turns of his sling around him and thrust himself easily against the braces. Sudden decelerations were all in the day's work for him. He lay there grinning at the dismayed cries wafted to him from the laboratory compartment just behind. He heard the crash of glass even above the vibration of the belching tube.

The trim little Sprite shuddered, then bucked. Slowly and tremblingly, she began her turn. It was not often the exquisite little yacht of Fava Dithrell experienced the rough and ready hand of a Space Guardsman at her throttle. Usually the ship took a more demure pace.

"Bob! What happened?" Fava herself had laboriously clawed her way to the control room, pulling along by the grab-irons in the fore-and-aft passage. Walter Berol, panting and dripping rusty- colored slime, clung uncertainly behind her. Both looked startled, but Berol also looked sheepish.

"Breakers ahead," announced Tallen calmly. "Some bonehead of a lighthouse tender forgot to recharge the beacon, or it's been robbed, or a meteor hit it. Anyhow, I thought I'd heave to and have a look-see."

"B-but... why so suddenly?" complained Berol. looking ruefully at his reeking smock. "I—I... that is, we..."

"Sudden is my nature," answered Bob Tallen serenely, jutting his jaw a trifle. "The situation called for a stop. So I stopped. It's as simple as that."

"Oh," said Berol.

"Walter was showing me how to use the laboratory he rigged up for me," explained Fava with a little flush, "and we were looking at a culture of those vermes harridans—those nasty pests that overrun Dad's plantations on Titania. You spilled 'em all over him when you reared back like that!"

"Tough," commented Tallen, looking casually up at the pulsating red light on the control board. It indicated a considerable celestial body not far ahead.

"I thought he could take care of himself. He's as big and husky as I am."

"Oh, I get it," Berol spoke up with a good-natured laugh. "The big bad caveman was up here all alone, and he thought it was time he got in an inning."

"Boys! Boys!" protested Fava. "Don't spoil our vacation. You sound like a pair of infants."

Walter Berol grinned.

Bob Tallen laughed too. "What the hell—nothing like a little emergency to pep up a party. Trot out the space suits, Fav, and we'll all take a stroll as soon as I can put this can alongside that rock, whatever it is."

Fava tapped her foot in annoyance, but there was a twinkle in her smoldering black eyes. She got a big kick out of the friendly rivalry of her two suitors. She liked them both immensely, even if they were as different as the poles.

Bob Tallen—Commander Tallen of the Space Guard—was bold, impetuous and able. He already had every decoration the Systemic Council could bestow. He would tackle a herd of Martian jelisaurs barehanded if Fava were threatened, and never think twice while he was doing it. She liked him for his swift decisions and his daring.

WALTER BEROL—Doctor Berol to the world, director of the Biological Institute—was easily more clever, but cursed with an incurable shyness that had all but wrecked his career. Yet, given time, he could solve any problem. Moreover, he was considerate and possessed of a droll sense of humor that made him good company anywhere. He was solid gold, even if not spectacular.

Fava felt the ship lurch as Tallen cut out two more tubes. The visiplate was glowing now, and a strange object was coming into focus.

"I'm damned," muttered Tallen, looking from his "Asteroid List" to the visiplate and back again. "Listen to this." He read:

The planetoid is known as Kellog's 218, and is a coffin-shaped iron body with some quartz inclusions. A Class R-41 buzzing beacon is installed, its period —

"Pear-shaped, I'd call it," said Fava. "It's a funny-looking thing, isn't it?"

"Looks like a rotten canteloupe impaled on an iron bar," remarked Berol.

"And at that end—where that pink, mushy-looking stuff is," exclaimed Fava, with growing excitement, "it seems to be covered with high grass!"

"Yes," said Berol, watching narrowly, "and it's undulating—as if in a breeze!"

"Nonsense," growled Bob Tallen, staring at the visi-screen. "How could there be wind on a boulder like that—and where did you ever see grass beyond Mars?"

It was a queer sight they saw in the visiplate—a writhing, doughy mass seemingly plastered on one end of Kellog's planetoid. And there was no beacon.

"Watch yourself!" called Tallen. "I'm landing."

WHEN Walter Berol and Fava were well up onto the first of the doughy terraces, they were astonished at how differently it appeared than as they had seen it from the ship. What they thought was mushy substance turned out to be a firm but yielding covering, much like dressed leather.

The waving grasses on closer examination appeared to be clusters of bare stalks of the same dirty pink material, standing like wild bamboo. Yet their eyes had not deceived them. The grasses did move, gently undulating as do the fronds of huge marine growths in terrestrial oceans.

"What do you suppose those things are?" Fava suddenly asked, looking down after the two had advanced a bit between two avenues of the strange clumps. At the girl's feet, scattered in the pathway, were little crimson knobs, like half-buried tomatoes.

"They look squishy," Fava said, and kicked one with her toe.

Her shrill scream followed so instantly that Berol was dazed. The nearest of the clusters came to life with startling speed. A snaky antenna dived downward like the curving neck of a swan and threw its coils around Fava. Paralyzed by the swiftness and unexpectedness of the attack, Berol stared dumbly as the groping tip took two more turns and was creeping onward to enwrap the girl's leg.

Berol fumbled at his belt for his hand-ax, and yelled hoarsely into his helmet microphone for Bob Tallen. Tallen could not be far away.

Before Berol could free his ax, he heard Fava's strangling gasp. The crushing pressure of the tentacle had choked off her breath. Horrified, he saw her being lifted upward; glimpsed a yawning, purple slit opening up a few feet beyond.

Berol's blood ran cold, but he attacked the clutching tentacle with all the fury he could muster. The first blow rebounded with such violence as to almost hurl the hatchet from his hand, but he struck and struck again. He saw little nicks appear, and a dark, viscous fluid ooze out, splattering. Half blinded by tears of helpless rage and sweat, he kept on hacking.

Then he knew he could not raise his arm, and he felt the lash of some heavy thing across his shoulders. His faceplate was fogged and he could not see, but he felt the hideous nuzzling beneath his armpit and then the cold, rib-cracking constriction as another of the frightful antennae seized him. He had only time to cry out once more:

"Help, Bob—Fava—Bob..."

Then he fainted.

"HE'S coming round."

It was Bob Tallen, speaking as through a bloody mist. Berol knew, from the sweet abundance of the air, that he must be out of his suit. He must be on the ship, then. He stirred and opened his eyes, saw Fava hanging over him, looking at him anxiously. Then he remembered—those entwining, crushing, cruel tentacles; and the vile, sticky blood of the beast—gaping, waiting, slimy and nauseating. Berol shuddered. But Fava was safe!

"It's okay, old man," he heard Tallen's reassuring voice. "You've been pretty sick, but it's all over now. We're hitting the gravel at Lunar Base in an hour, and there's an ambulance waiting. In a couple of weeks you'll be good as new."

"That... thing... was... organic," Berol managed. "Did... you..."

"Forget it," said Tallen. "The sky is full of weird monsters. I burned that one down with my flame gun, and that's that. I daresay that rock was swarming with 'em, but never mind. It's two hundred million miles away now."

Berol tried to forget it, but he could not. He could not forget that he had been at Fava's side when she was imperiled, and that he had failed. It was Tallen who blasted the monster down—whether it was animal or vegetable or some hideous hybrid.

So he was thinking as he tossed and fretted in his room in the great hospital in Lunar Base, knowing that Bob Tallen was making hay while the sun shone. Tallen was still at the base, fitting out the new cruiser Sirius which he was to command. He had all his evenings free, however, and these he spent in company with Fava...

"You are a dear, sweet boy and I'm fond of you," Fava told Walter Berol, as she walked out with him the day he was discharged. They were on the way to the launching racks to see Bob Tallen take off for his shakedown voyage. "But the man I marry must be resourceful, masterful. I'm sorry... I don't want to hurt you... but..."

"It's to be Bob, then?"

She nodded, and suddenly the universe seemed very empty. Then a feeling of unworthiness almost overwhelmed him. Yes, she was right. He lacked the red-blooded qualities she admired in Bob Tallen. He was not fit mate for her.

But as suddenly another emotion surged through him. It was the old primeval urge—old as the race itself—of a man balked of his woman. He meant to have her, Tallen or no Tallen.

"You will not marry Bob," said Walter Berol quietly.

FAVA'S voice had been urgent, frightened.

"Come over to Headquarters at once! I am so afraid—for Bob."

Walter Berol stood only for a moment on the landing deck atop his great laboratory before stepping into the gyrocopter, but in that moment he cast an uneasy glance at the serene star-spangled canopy overhead. Disquieting thoughts were running through his mind.

In the three weeks since Bob Tallen and the Sirius had departed, many disturbing reports had come in from the asteroid belt. Eleven sizable planetoids were missing from their orbits—vanished! A dozen assorted cargo ships were overdue and unreported. A lighthouse tender had sent a frantic S.O.S. through a fog of ear-splitting static, and had been choked off in the middle of it with the words, "We are being engulfed..."

The gunboat Jaguar, sent to aid the tender, had not been heard of since. It was all very inexplicable. It was ominous.

Berol strode past the grim-faced sentries outside the General Staff Suite. As Director of the Biological Institute, he could enter those carefully guarded precincts. Inside, the room was jammed with officers, listening intently and gazing at the huge visi-screen. Fava sat beside an Admiral Madigan, fists white as snow as she clutched the arm of the chair. Berol stopped where he stood. A deep bass voice was coming in through the Mark IX televox.

"That's Bill Evans, in the Capella," whispered someone.

"...we've finally caught up with the thing, whatever it is, and are close aboard now. We have circumnavigated it twice, but there is not the slightest trace of the Jaguar or any other ship."

Walter Berol was staring at an incredible landscape slipping beneath the Capella's scanner. It was a dirty pink, and studded with many curious knobs of writhing tubular matter. It looked soft and mushy, very much like a rotten pumpkin. It strangely resembled the bulbous end of Kellog's 218. Berol shuddered at the memory. Evans went on, "... the waving clumps mentioned by the Jaguar just before her radio went dead are not visible. All I can see is mounds of what looks like Gargantuan macaroni lying in heaps. The skipper is about to land. In a minute or so I'll give you a close-up. Stand by!"

There was a raucous blare of unusually heavy static, and when the voice did begin again, it was hard to make out the words. The static distorted the visuals, too, so that the screen was a blur of crawling pink light and no more. Presently the operators managed to eliminate the worst of the noise, and the voice came through once more, bellowing out against the deafening barrage of sound.

"...surface very deceptive... quite hard and tough. A landing party has gone out through the lock and is cutting samples of the surface with drills and axes. One man is chopping at a huge crimson growth as big as a barrel. Hold on—one of those hillocks of collapsed tubing is moving! The things are whipping around like snakes! Some of them have shot straight up into the air, and others are curling all around us!"

Berol edged his way through the crowd. Fava was breathing hard. Admiral Madigan's jaw was granite and his eyes never wavered from the screen.

"...they are tentacles! One has wrapped itself around our bow, and another group has caught us amidships. That is why we roll and pitch this way. The captain is clearing away the Q-guns. In a minute we will blast out—you'd better cut down on your power until that is over. There he goes..."

A dull roar filled the room and the walls trembled. Then the volume dropped. Brilliant scarlet light slashed and stabbed across the visiplate, and then it went almost black as if obscured by thick, oily smoke.

"...all stern tubes in full discharge. The surface of the planetoid—if this damn thing is a planetoid—is smoking furiously. Several clusters of the antennae astern of us have been burned away. We're still hung here, though. Looks like the impulse of the tubes is not enough to tear us loose from that grip forward ..."

A wail of unearthly static drowned out the laboring voice. Then,

"...trying the bow-tubes now. Wait. No, they can't get out that way ... the spacelock is submerged and we're twisting over fast! A huge crevasse has opened up under us. We're sinking into it! The whole port is covered. We—a-a-awrk!"

The voice ceased, choked off, and the light on the screen went out abruptly. In the dark room no one spoke for an instant. Berol felt, rather than saw, the tension among the hardened Space Guard officers. Fava's hand crept into his and clung to it.

The Capella had just gone to the doom they had so nearly missed, for there was no mistaking the similarity between this monster of unguessable nature and the menace on Kellog's 218.

"RAISE Sirius!" broke in Admiral Madigan's voice,

crisp and angry. "What the hell is Tallen doing all this

time?"

But the Sirius was there, hovering over the spot where the Capella had been, her shattering Q-rays lashing down, searing acres of the ravenous false asteroid. She turned on her televox so that those at Headquarters could see the quivering, sizzling terrain below. Clumps of the three hundred foot antennae were being roasted to a sooty ash, and swelling and popping with evil gases as they did. Bob Tallen's voice came through, strong and clear, barking out strident orders.

Nothing the Sirius could do, however, could save her floundering sister. The upper turret of the Capella sank out of sight, and the scorched, leathery integument closed over it. In a few minutes there was only a livid, ashen scar, and even that mark faded.

Commander Bob Tallen's face came onto the screen, huge in its close-up.

"Heat does it," he said tersely. "Send me all you've got, and H.E.—feroxite by the ton. I'll blast the damn thing to shreds, and then burn the shreds."

As the face faded, Admiral Madigan sprang into action.

"Out of here, all of you! Squadrons Three, Six and Ten take off at once. Report to Tallen when you get there. All reserve flotillas will install heavy-duty flame projectors and take on fuel to capacity. Report to me the instant you are ready."

He jerked out other curt orders and the officers hastened from the room. Fava had withdrawn to one side, looking on with eyes wide with horror. How well she knew the grip of those merciless tentacles! For there could be no mistaking that the monstrosity she had just been watching was the same as that on Kellog's 218, grown larger. And she sickened at the memory of the slimy fissures the vile beast seemed to open at will. It filled her with dread, for Bob Tallen was going to attack the thing, and he was rash, so reckless in his daring.

"Oh, Walter!" she cried, clutching Berol by the arm. "Do you think..."

Walter Berol shook his head gloomily.

"It is too late for brute force. The thing is too big. We should have found out something about its nature and destroyed it when it was little. But it must be four miles in diameter now, and growing as it feeds. All our fleet can have no more effect than a swarm of gnats nibbling at a rhinoceros. If it is to be attacked at all, it must be through its biological processes. Bob is attempting the impossible."

Admiral Madigan wheeled, a smile of cold scorn curling on his lip.

"So! The dreamer leans from his ivory tower to look us over and tell us we're wrong. Well! And what is the solution the great brain has to offer? Quickly! This is an emergency—men have died before our eyes!"

"I—don't—know," said Dr. Berol slowly. "It will take time, research. I will begin at once..."

"Bah!" snorted Madigan. "Research! It is lucky that there are men of action at hand. Like our Tallen."

He turned away abruptly, leaving Walter Berol standing where he was, his face aflame. Dull anger rose in his breast, but there was pity mingled with it—pity for the blind arrogance of these self-styled men of action, who thought they could control this colossal menace with their puny weapons.

For of all the men in that room, only Berol realized to the full the immensity of the threat that hung over the Solar System. If the monster had drifted in as a spore from the beyond, consumed cosmic gravel until it was big enough to digest a body like Kellog's iron planetoid, where would it stop? After the asteroids, what would it devour? The planetary moons, perhaps. And after those?

In that instant Walter Berol resolved to stop this Mooneater—and knew that he would face ridicule and obstruction. But the pink menace was more than a threat to the race—it had become a personal symbol. The creature, whatever its nature, had attacked the woman he loved, then crushed and humiliated him in her presence. Now it had brought the taunt of this space admiral.

"Fava," he said abruptly, "I want the use of the Sprite."

"And if I refuse it?"

"Then I shall commandeer it in the name of the Institute."

THE air of quiet finality in his tone startled her. He

had used it once before—the day he said she would not marry

Bob Tallen. She looked at him wonderingly, then shrugged

prettily. Let him try; he meant well. But she was sure he would

fail. Out in the cold, gravityless vacuum of space he would fail

as he always had outside his laboratories. That did not matter.

What did matter to her just then, was that she saw a pretext to

be near her sweetheart.

"Very well, Walter," Fava agreed, smiling. "But remember, I am rated as a laboratory helper—and the Sprite is my yacht. I intend going, too."

"But the danger..."

"Bob is in danger too," she said simply.

"DEAD," murmured Walter Berol. On the table in the Sprite's flying laboratory lay a clumsy Venusian rock- chewer—the Lithovere Veneris—a queer, quartz- eating variety of armadillo. Seen through the fluoroscope, all its internal organs were still.

"A twentieth of a grain of toxicin* has no effect—a tenth kills it."

[* Toxicin: a powerful chemical substance which is capable of breaking down and dissolving the proteins of certain living creatures, such as the rock-chewer of Venus, described here as an armadillo-like creature. —Ed.]

"So you think—" Fava was looking on.

"No. It is merely worth trying. The Mooneater's internal chemistry may be the same; it may not. We have twelve drums of the stuff on board. I want to plant it on the monster's next victim. Then we will watch for the effect."

The next victim was the small planetoidal body Athor. Men had learned something of the predatory habits of the pink invader. This tremendous monstrosity swerved from orbit to orbit by the manipulation of magnetic fields, which it set up with a howling of static. Inexorably it pursued the cosmic body until it overtook it. Then, without any crash of collision, the marauder would split open along its leading face and take the planetoid bodily into itself. The maw would snap shut and the Mooneater would move on, bigger and more ravenous, to its next prey.

Fava set the Sprite down in the dismal Athor canyon known as South Valley. There was barely time for what they had to do, as the Mooneater was already a huge and growing disk in the black sky. They could even make out the lightning playing over its surface where Tallen's cruisers hung in a cloud, ever blasting, burning and harassing. Time after time they had scarified its surface, until there were only black stumps where the antennae clumps had been, but as often the monster grew fresh ones.

Walter Berol put on a space suit and with four of his crew sought a cave in which to cache their deadly drug toxicin. But hardly had they emerged from the lock when, with a fiery swoop, a huge warship settled to the ground nearby. A dozen helmeted figures sprang from its airlock and bounded toward the grounded yacht.

"What are you fools doing here? This asteroid was ordered evacuated thirty hours ago!"

The voice was Bob Tallen's, harsh and angry.

Then in astonishment Tallen recognized the familiar lines of the Sprite, and knew the man before him was Berol.

"My God!" shouted Tallen hoarsely. "Fava here? Get out—at once—while you can!"

He pointed to the oncoming Mooneater, which now filled a quarter of the sky.

"I see it," replied Walter Berol. "We will leave as soon as we dump some drums of chemicals. I am planting a dose of poison..."

"Arrest this man!" Bob Tallen whirled on the bluejackets who had followed him.

The sailors from the Sirius pounced on Berol and bore him protesting and struggling into the Sprite, Tallen following close behind. Inside the yacht Tallen snapped orders to the other ship. The airlocks of both vessels rang shut, and on the instant they plunged upward with streaking wakes of flame.

"Look," said Bob Tallen dramatically, pointing back at the asteroid.

The Mooneater was no more than four diameters away. It had opened its maw, revealing a slimy, purplish cavern. Five minutes later the ghastly pseudo-lips were closing in on the periphery of little Athor. Then there was but a livid line to mark where the asteroid had gone. The pink monster rolled on, heedless of the massed cruisers stabbing at it with their Q-rays and heat guns.

EVERYONE gasped a little. "If it had not been for me,"

Tallen went on, his face a thundercloud, "you——and

Fava—would be inside there. I have placed you under

restraint to save you from your own idiocy. This is a man's game.

It is no time to play around with theories. Action is what is

required now."

"You've been in action for two months," retorted Walter Berol with pointed irony. "The Mooneater, I believe, has approximately trebled its volume in that time. If that is how effective action is, I think it is high time somebody did a little thinking."

"That's my worry," snapped Tallen. "The Autarch, head of the Systemic Council, has given me this job. When I want help I'll ask for it. Until then, you are to keep out of my way."

FROM Mars the destruction of Deimos was plainly seen. Every eye, every telescope, every pair of binoculars was trained on the oncoming scourge. Batteries of cameras drank in every detail through telephoto lenses. Photographic plates were made from ultra-violet and infra-red rays. At every vantage point the Omnivox announcers set up their mikes and described the battle to the thoroughly aroused citizenry of the Solar System.

Bob Tallen, now a Space Guard commodore, had set up his controls in the south tower of the administration building in Ares City. He was ready for the final test of strength between his forces and the hitherto irresistible pink menace. Under his direction Deimos was honeycombed with galleries and tunnels—miles of mines packed with tens of thousands of tons of feroxite. Around Mars' equator, heavy siege guns had been placed to assist the ships in their bombardment. In one tremendous concentration of flame and violent detonation Tallen proposed to blast the marauder to bits.

The Sprite was safely tucked away in Martian Skyyard, and to permit Fava and Walter Berol to witness his triumph, Tallen had made room by his side for both of them.

Fourteen cruisers of the first class, and many dozen lesser ones, had trailed the Mooneater from the asteroid zone, hammering incessantly at it as they followed. Day after day they had pumped high explosives into it and played fierce flames upon its ever- sprouting tentacles.

Hundreds of cargo ships shuttled between the fleet and the bases, bringing fresh supplies of fuel and ammunition. As a demonstration of the sustained application of brute force in massive doses, Tallen's campaign had no precedent. Now he was ready for the kill.

"It won't work, Bob," said Berol mildly, as he watched the huge pink orb advancing on Mars' tiny moon. "The thing is organic, I tell you."

"So what?" barked Tallen. "If it lives, it can be killed, can't it?"

"If you can apply enough force at one time. That is what you cannot do. You are trying to kill an elephant by jabbing it with a penknife. Being organic, the creature is capable of self-repair. That is where you're licked. You've got to upset its organic functioning..."

"I'll upset its functioning," said Bob Tallen grimly, his eye on the monster. It was within one diameter of Deimos. He jabbed the button before him—three times. The attack was on.

A cloud of cruisers darted between the yawning mouth of the Mooneater, letting their salvos go into its open chasm. Others smothered its rear areas with raging flame. And as the Moon-eater advanced relentlessly in spite of all, until its hideous pseudo- lips closed on the little satellite, Bob Tallen pressed the key that set off the radio-controlled mines.

"Ooooh! Look!" screamed Fava, gripping Berol's arm. "Bob has won! He has torn it to shreds!"

For a few minutes it appeared he had. An immense blister rose as one side of the Mooneater swelled to accommodate the terrific blast of the expanding feroxite gases within. Then the monstrosity burst shatteringly in scores of places, as in a chain of terrestrial volcanoes, tearing great strips of the beast's entrails. Gaping streamers and shreds of purplish flesh were flung out into the void, rent by the explosion. Other strings of viscid stuff drooled from the jagged slot that had been a mouth, only to flash into flame as the ray-guns lashed at them.

Then the throaty roar of thousands of heavy guns from Mars drowned out all other sound. The moment the space ships were clear, the artillery opened up, slamming salvo after salvo into the harried monster. Huge hunks of the leatherlike hide were torn out, leaving ragged craters. Tentacles were blown to flying fragments and ripped away by their roots. With an outpouring of static that exceeded any before, the monster turned away from Mars and headed back toward the asteroids.

BOB TALLEN glared incredulously after the retreating

raider. He had hurt it—yes. But it was still intact!

It had not disgorged the satellite it had just devoured. It was

on its way back to complete the clean-up of the asteroids.

Cruiser after cruiser fell away from it and headed back to Mars.

They were out of ammunition. The great stroke had been

made—and had failed!

"With your permission, Commodore Tallen," remarked Walter Berol dryly, "I will take up my researches where I left off. I notice that your high explosive shells have a penetration of something like three hundred feet. When you consider that the Mooneater is upwards of ten miles in diameter, it ought to be clear that you are doing little more than irritating its hide. It must be attacked from within, not externally."

"Research and be damned to you!" Bob Tallen flung at him, reckless in his anger and disappointment. "You keep yelping about what science can do—well, show us! Only keep out of my way."

"I will do that," replied Berol coldly. He rose and left the room, and he did not glance at Fava as he left. He realized the challenge had been given and accepted. His first job was the conquest of the Mooneater. His personal affairs could wait. After all, if the Mooneater was to be permitted to glut itself without stint on the planet bodies of the Solar System, the time was not far off when personal affairs would cease to exist. From that moment Walter Berol dedicated himself to the destruction of the pink monster.

BEROL did not go near the Sprite. Instead he took the space tender Jennie from the Martian branch of the Biological Institute and went up and into the orbit of defunct Deimos. Floating there in tumultuous disorder were the gouts of viscous matter ejected from the wounded Mooneater, intermingled with long streamers of jagged and torn tissue. Berol gathered tons of the stinking, filthy stuff and carried it down to the branch laboratory on Mars.

For many weeks he immersed himself in the examination of his specimens. He and his aides sectioned, cultured and analyzed. He was amazed at what he found. The monstrosity was built of proteins!* By some freak of internal chemistry, the creature could actually transmute the heavier elements to lighter ones: convert iron to flesh and quartz to organic fluids.

[* Protein: an albuminous compound derived from a proteid, one of a class of important compound found in nearly all animal and vegetable organisms, and containing carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and sulphur. —Ed.]

Yet despite his discovery of the macrocosmic nature of the monster's structure—it had individual cells as big as apples—he could learn little of its constitution as a whole, and nothing of its vital organisms. What he had was bits of the epidermis, or the droolings from its surface fluids. His task was as hopeless as that of reconstructing a whale from a few square inches of torn blubber.

Berol was still doggedly working at his quest when an "All- System" broadcast broke the stillness of his study. When the Autarch spoke, everyone listened.

"The peoples of the Solar System are advised that the Supreme Council has decreed that the wasteful war on the invader popularly known as the Mooneater shall cease. In spite of the gallant efforts of the Space Guard, it has destroyed all our asteroids, including Ceres and the moons of Mars. It is now close to a thousand miles in diameter and quite beyond our power to control..."

Dr. Berol gasped. He had lost touch with the outside world and did not know that things had come to such a pass.

"It is ordered, therefore, that all the satellites of the System of less than the destroyed planet bodies be evacuated immediately, and that scientists of every category abandon whatever research they may be engaged in at present, and concentrate on the problem of rendering Jupiter habitable. Our mathematicians have extended the curve of the Mooneater's consumption, knowing the size of the planetoidal bodies remaining, and have computed with great accuracy the date of extinction of each of our planets. Only Jupiter is so huge that the Mooneater can never grow large enough to swallow it.

"The Autarch has spoken!"

WALTER BEROL sat staring at the dead amplifier long after

that final click. So Bob Tallen was beaten. The Autarch was

beaten. The human race was beaten. It meant extinction, for it

was unlikely that great king of planets could ever be made

habitable for man. And if it should, there was not enough

transportation in the System to convey the populations there.

Berol, too, was beaten. He realized that. All the feverish work of recent weeks was wasted. He had reached no conclusions, he had not found the fatal toxin that would kill the monster. Nor had he any clear notion of how to introduce it if he had it. It is true a cobra can kill a bull by the prick of a fang. But Berol had no proven poison, nor the means of injection. And now came the order to drop all work. His failure was complete, for the Autarch's dictum was final.

Wearily he pressed a button on his desk.

"Close our files on the Mooneater," he told his laboratory chief. "Let me have the index on the 'Flora and Fauna of Jupiter'."

FAVA DITHRELL burst excitedly into Walter Berol's study.

"Walter," she cried, "the Mooneater is here! It is passing Europa now!"

"There is nothing we can do about it," said Berol. "We have orders to disregard it. Anyhow, Callisto is safe for the present."

When Berol had moved his headquarters to be close to Jupiter, he was not greatly surprised to find that Fava was already there as a helper. The order of the Autarch had been for engineers of every degree and all scientists to work on the Jupiter project, and Fava was known as an amateur biologist. Berol had long suspected that she applied for a position in the Callistan laboratories because Bob Tallen was based on nearby Io. Since he had been pulled off the Mooneater hunt, Tallen had been put in charge of the evacuation of Jupiter's minor satellites.

"The Mooneater," Fava was repeating. "It's behaving queerly, Walter. It passed the small outer satellites without touching one of them."

"Hm-m," he mused. "That is odd. It may be significant." He drummed the desk with his fingers. "Perhaps it has reached its full growth; it may consume less hereafter."

The behavior of the Mooneater was odd, indeed. It skirted Jupiter's moons on a lazy, incurving spiral, and then departed from the Jovian* System without molesting even its smallest satellite! Speculation was rife. Had the monster attained its optimum—its maximum size? That could be it: each race of creatures has a limiting size. Only time could answer.

[* Jove and Jupiter are interchangeable mythological terms. Jovian is the adjective. —Ed.]

But as the panic subsided among the Jovian colonists, screaming accounts of the exodus from the Saturnian System began filling the news. The pink monstrosity was heading that way, and all of Saturn's moons, with one exception, were of edible size.

On rolled the Mooneater. It slid past Phoebe, past Hyperion and Rhea and all the other little moons. It touched none of them, but went on in close to the great semi-liquid planet. There, astoundingly enough, it swam into the midst of the Ring and stayed, floating for weeks about Saturn as a self-elected satellite! Then, as unaccountably as it had come, it left, and spiraled outward to intercept Uranus.

Walter Berol learned of it only because Fava told him. Her father's ranches were located on Titania, and she feared the properties were doomed. Berol shook his head gloomily. There was nothing he could do. The Autarch had repeatedly refused to permit him to resume his efforts. The head of the Council had gone so far as to threaten stern disciplinary measures if the matter was brought up again.

But Fava's account of the Mooneater's actions in the vicinity of Saturn had a galvanic effect on Walter Berol. He jumped up excitedly.

"Yes, yes—of course! I might have anticipated it. The answer lies there, surely. She would have gone into the Rings for no other purpose—."

"She!" snapped Fava, her fears scurrying before her sense of outrage. "Why confer my sex on that unspeakable monster?" She stamped her tiny foot angrily.

"Yes—she!" Berol fairly shouted. "Don't you understand? We have to deal now with more of the accursed things—thousands, millions of them, perhaps. We must go there at once and stamp out her hellish progeny!"

FAVA was staring at him dumbfounded. Such a display of excitement was very rare with Walter Berol. He talked on, vehemently.

"This monster was small once—how small we never knew. In the beginning it probably consumed cosmic sand and gravel, then boulders, then moons. Now it is mature, and like all other living things, it is under the compulsion to reproduce. She has laid her eggs in the Ring gravel!"

Fava's tension broke with a merry tinkling laugh. "Walter, have you gone crazy? Eggs! How fantastic!"

"Not at all. There can be no other conclusion. We see the cycle of the monster's life beginning all over again—with sand and gravel, and small diameter bodies near at hand. Like the bee, the ant and the beetle, she deposits her eggs where food suitable for the newborn is the most abundant. Why else would she abstain from eating those satellites herself? We know her appetite. Hers is the mother instinct!"

Fava gasped. It was a bold idea, but plausible. The Mooneater was a living creature, no one doubted that.

"But will the Autarch—" she began.

"To hell with the Autarch and his one-track mind!" Berol yelled, snatching up his head covering. "Your yacht, Fava—it is completely equipped. We'll defy them all. The existence of the race depends on us. In those baby Mooneaters is the clue to their structure, their chemistry. Come!"

"WE are practically at Ring speed now," said Anglin, Fava's sailing master.

All about them hung the glittering quartz and crystalline iron nuggets that swing forever about Saturn in broad bands.

"Good," said Walter Berol. "Turn on the ultra-violet beam."

He slipped on a space suit and went out onto the hull. For a long time he sat, holding a long rod that had a butterfly net at its end, studying the reflected rays sent back by the Ring particles. All about them seemed to be a sort of fog, so filled was the space with suspended dust and sand. Few of the little stones that compose the Ring are larger than marbles. It was a perfect feeding ground for embryo Mooneaters.

It was more than an hour before Berol caught the first embryo, but once he learned the peculiar lemon-yellow light with which they fluoresced, he began hauling them in by the dozens. They were not unlike basketballs—leathery, pinkish orange spheres covered with downlike fuzz. Those tiny hairs were what in time would come to be the horrid tentacles that held smaller prey—until one of the myriads of slit like mouths could open beneath.

Walter Berol turned the job of catching the creatures over to a pair of deckhands, and then hurried below with his first specimens. Triumphantly he slammed them down onto the dissecting table before Fava.

Swiftly, and under her watchful gaze, he slit one of the creatures open, cutting it from pole to pole with a green scalpel. He laid bare the hooplike formation of ribs ranged after the fashion of earthly meridians. His knife revealed the heavy circumpolar muscles that pulled the ribs to one side when in the act of eating huge masses. And under the viscid, purplish jelly that filled the body cavity, Berol found the palpitating green organ that must be the brain.

As rapidly as his fingers could fly, Berol traced the outflung intricacies of the branching green nerve-trunks, even to where they terminated at the skin in the tiny red specks that picked up the motor impulses*. Berol found the arterial tubes that conveyed the purple life-juices from the central reservoir, and he located the many subsidiary stomachs that lay under the fissured openings. Within an hour he had a clear understanding of the monster's anatomy.

[* It was Fava's kicking at one of those red nerve-ends that had caused the tentacle to grasp her. —Ed.]

"Bring me a needle of toxicin," he ordered.

Fava injected the poison in one of the living specimens, but it had no effect. Then she tried heteraine, and totronol.* The totronol was also harmless, but the heteraine had a definite narcotic effect. It caused a temporary paralysis of the parts where it was injected.

[*Heteraine is a narcotic drug, extremely poisonous to humans in anything but infinitesimal doses,although it is a distillate of the paralysis spray of the Venusian giant boa. Totronol is an earth drug which totally destroys the motor nerves of the spinal column inducing a permanent and quickly fatal paralysis. —Ed.]

"That's something," muttered Berol, after they had exhausted the list of drugs and poisons. "Now for disease germs."

Ranged about the compartment were phials and phials of bacilli. There were samples of the bacteria that caused every disease of man, beast, plant or known monster of the airless, dark planets. There were skuldrums—fat, sluglike lumps of fatty stuff that was the fatal enemy of the Plutonian lizard-cats. There were the thready spirochetes that plagued the Venusian rock-chewers, driving them to madness. There were others—globular, tubular, disk-shaped, some winged, some ciliated, some with fins. Each was sure death to some other living thing.

"Here," Berol said to Fava, handing her a tray full of ripped- out nerve ganglia and greenish brain fibre. "Find out whether any of these bacteria thrive in this stuff. I'll tackle the blood angle. Hurry!"

Fava blinked in mock dismay. Walter Berol had never spoken to her in such a brusque and authoritative manner. But she did not dislike it. She took the tray and went.

In ten hours they found the parasite they sought. It was a thin, pale worm—the illi ulli, parasite worm of the Venus fish life! Once it was introduced into the green nerve stuff, it multiplied at a terrific rate and quickly consumed it all.

"Now for the grand test," said Berol, as he leaned over a baby Mooneater with a hypodermic filled with a liquid that was crawling with the illi ulli. A quick jab, and the thing was done. Within an hour the leathery ball was a flabby corpse, its nervous system gutted by the ravenous worms. As it died, its multitude of slitlike mouths gaped open, gasping like the gills of an air-strangled water fish.

"Eureka!" whooped Dr. Berol, leaping into the air.

THE Sprite lurched forward, her jets screaming

under forced discharge. Berol slewed the periscope about and took

a look astern. Thousands of the leathery balls that might have

grown into Mooneaters were springing into fiery incandescence,

then exploding with silent plops! as the full energy of

the backlashing rocket stream struck them. Berol knew there must

be many thousands more of them, but someone else would have to

sweep them up. He had bigger and more urgent game ahead. But

first he must go into Iapetus for some needed supplies.

"Fava, while I am getting my rigging on board, your job is to make the illi ulli grow. I want 'em big—as big as possible—as big as anacondas, if you can do it. Force mutations on them with the X-ray, and feed them the synthetic diet I prescribed. Cull out the larger ones and let 'em propagate, and so on."

He snatched up a set of headphones and got through to the Governor of Iapetus. He lied glibly in a manner that simply amazed Fava. For Walter Berol issued a multitude of crisp orders—and said they were in the name of the Autarch and the Systemic Council! And he was probably already down on the punishment list for having vacated his post on Callisto without permission!

"I want," Berol snapped, "two large-capacity cargo ships loaded and ready to hop off tomorrow night. Here is the list of what is to be on board them."

It was an odd list: a two hundred foot derrick, a Myritz- Jorkin drill rig, complete with drill-bits and spare cutting heads; a hundred thousand feet of steel cable on spools; a three- inch detonon gun, with a thousand rounds of H.E. ammunition, but the shells to be unloaded except for delicate fuses; and twenty drums of 80% heteraine solution. With that equipment he wanted a drill crew of huskies and roughnecks from the gas fields of Io.

"That is all," barked Berol, as the acknowledgment came back. He yanked the jack from its socket and turned, to find Fava still by him.

"Well ?" he said tartly. "Why aren't you nursing those worms along? Time flies!"

"I wanted to tell you, Walter, that I think you are wonderful." For the first time in many months Fava dropped the bantering tone she usually used toward him. "I had no idea you could be so—masterful! I didn't know... well, that you could do things... I-I..."

His impatient frown melted. Then he laughed uproariously for the first time since his encounter with the Mooneater on Kellog's 218.

"Oh, I see. Even you fell for the popular superstition that scientists have to be drier-than-dust, impractical boobs."

"B-but," she stammered, "you were always so clumsy ... so timid... outside the laboratory..."

"You saw me trying to do things I didn't know how to do. That is all. But I am back in the laboratory—the whole Solar System is my laboratory now. I'm doing the work I know best. The difference is in the scale of it. I am on my way to inject an animal with disease germs. Since its hide is five or six miles thick, it calls for a gigantic needle." He laughed a little grimly.

"SURE!" said old Harvey Linholm, the gigantic six-foot-

ten master rigger who had been supplied with the drilling gear.

"We see the whole damn idea. Me and my men will go to hell and

back with you, Doc, if it comes to that. We've lost plenty to

that moon-gobbling, howling menace, and we're fed up with it.

Besides, I'd as soon die right now takin' a crack at the thing as

wait and go to Jupiter. I can't see livin' on giant

Jupiter—think of what I would weigh there!"

Berol grinned. He turned to the captains of the two supply ships.

"All right, then. Take off at once and proceed to the spot I gave you the geodetics of. I'll overtake you. After that, follow me down."

He hurried away and mounted the ramp up the side of the Sprite's launching cradle. An obviously agitated Fava overtook him as he was about to enter the ship.

"We've lost," she moaned. "The gendarmes are on the way to seize you. The Autarch has learned of your assumption of authority here and has ordered you brought to the Earth in irons for trial."

"They'll have to hurry," said Walter Berol grimly, swinging the door open. "I'm taking off in ten seconds, Autarch or no Autarch."

"That's not all," Fava said in a low voice. "Bob Tallen has found out where I am and is on his way here to get me. I had a message from him forbidding me to have anything more to do with you."

"Ah," said Berol. "Perhaps Bob could tell us how the Autarch happens to know so much about our expedition."

"Yes," she nodded, and it was almost a whisper.

Berol's face hardened. "I am shoving off—now! You may come or not. Please yourself."

"Let's hurry then," Fava said, closing the lock door behind her. "The police and Bob won't be far behind."

THE Mooneater was as huge as Luna. Led by the Sprite, the little flotilla circled in, warily, surveying the forest of clutching tentacle tips, now reaching thousands of feet into the sky. Lower and lower they flew, until at times they were diving between rows of the clumps.

"Shoot at the red spots," directed Berol, pointing out the nerve-ends. "Or at those greenish veins."

The detonon gun crew slammed in a shell—a shell loaded with the numbing drug heteraine instead of its usual high explosive. They aimed and fired, and as the missile tore its way into the monster's nerve fibre, the nearest group of tentacles lashed and writhed in fury. Eight, nine, ten—shot after shot ripped into the antennaes' controlling ganglia. Then the clutching, whipping arms went limp and collapsed their full two miles in length onto the pink plain beneath.

The ships circled and came back to shoot down another set of antennae. By the time they slid to a stop on the horny hide of the Mooneater itself, the doped tentacles lay in mountainous piles for several miles around them.

"Quick!" commanded Berol, the moment they were at rest. "All hands outside! Squirt more heteraine into every nerve-end you see. We must anesthetize this entire area."

Men scampered about the grounded ships with big cans of heteraine strapped to their backs, jabbing sharpened pipes into the quivering nerve-ends. In a little while that part of the Mooneater was as inert as the floor of a crater on Luna herself. Beyond the narcotized section, the rest of the tentacles could be seen in agitated motion, twisting and clutching. Walter Berol anxiously scanned the black void from which he had come, but he saw no sign of the jet flames of his pursuers. He might accomplish his purpose yet.

After the anesthetic squads came the riggers. They unloaded the ships where they lay on the Mooneater, and by the time the first rest period had come, the derrick was up. Ten hours later, the hole was spudded in. Then the drill-bits began to grind, gnawing their way down through the horny hide of the monster like steel augers through an ancient cheese.

From time to time Fava and her steward made the rounds of the nerve-ends and shot fresh injections of the deadening drug into them. It was of utmost importance that they keep the monster numb and quiet where they worked, as its slightest shudder would have all the effect of a devastating earthquake. They might lose not only their drill-bits, but the derrick. And somewhere near about must be one of those auxiliary mouths that could engulf them all in a moment.

IT was at a depth of just seven miles that grizzled Harvey Linholm announced his drilling was through. Sticky, viscous purple blood was welling up and spreading lazily about the lip of the hole. That meant they were through the tough outer skin and down into the tenderer tissues beneath.

"Pump it out and set your casing," Berol said, and went to see about his snakes.

Under Fava's forced feeding they were monstrous serpents now, ten feet or more in length, and more fecund and voracious than ever. Selection and high-speed evolution had done miracles. They were unbeautiful worms—slender, eely creatures with forked tails and transparent skins, but they had insatiable appetites and bred at an astonishing rate. Walter Berol felt certain they would do the work he expected of them.

Berol stepped under the derrick presently and gazed down the shiny barrel of the well. To one side stood fourteen crates of selected illi ulli, a portable flame-cutter, and a shoulder-size container of heteraine, along with hypodermic injection pipes. The worms were hungry, as always, and squirming and hissing venomously to show their irritation at being cooped up in the long cylindrical baskets. Berol put on the heteraine container and grasped the flame-thrower, then reached for the sling that was to lower him into the depths.

A spasm of revulsion and cold fear suddenly swept over him, and for a moment he shut his eyes out of sheer horror. Thirty- seven thousand feet down into the tissues of this monster—and through a slender forty-inch hole! All the confident self-assurance that had sustained him until then oozed from the biologist. His former timidity threatened to take control again, and his resolution faltered. He was badly rattled.

For in that instant Walter Berol ceased to think of the Mooneater as a mere laboratory specimen, even though a colossal one, but rather as a living adversary. He was about to do what countless generations of men had done before him—enter into mortal hand-to-hand combat with a ruthless enemy!

Vaguely he sensed that Linholm was watching him, awaiting the signal to lower away. And back of the silent group of drillers was a small helmeted figure—Fava. She, too, was watching. And then, as in a vision, Berol was aware of the millions of helpless humans everywhere whose existence hung on his own hardihood. And Bob Tallen was on the way to stop him.

"Lower away," Walter Berol managed, and hoped dumbly that his voice did not reveal the quaver he felt in his soul.

The gleaming neochrome casing quickly turned to a dead black, as he shot past its thousands of fathoms. Down, down he plunged. Then, after what seemed centuries, his pace began to slacken and he knew he must be nearing the bottom. He ceased to feel the slick metal walls, realized he was hanging in a subterranean cavern. His next sensation was that of being plunged knee-deep in slimy mud, only the mud was warm and clinging, like a live thing.

Berol snapped on his crest lamp and looked about him. He was in a huge purple cavern, lined with slime-dripping tissue, and interlacing purple tubes told him he was looking at Gargantuan capillaries. Over in a corner was a bulbous lump of green mush—the creature's nerve stuff—a minor ganglion, no doubt, for the functioning of the antenna clump immediately overhead.

Berol stood clear and sent the sling back up. Now they would send down the baskets of illi ulli. Until they came, he sloshed about in the stinking mire, slashing at the nerve-leads with his machete and injecting each one with a few ounces of heteraine. By the time his serpents came, he had openings ready for their entry into the monster's nervous system.

He unhooked the first of the baskets with trembling hands, but steadied himself with the thought that he was now at the culminating moment of his great experiment. A few more steps, and he would know whether he had succeeded. He had gone too far to weaken, and he tried to shut out of his imagination the seven miles of solid organism that separated him from his kind.

THE pale serpents wriggled vigorously through the muck the moment Berol released them. Their instinct seemed to direct them unerringly, for they made straightway for the nearest nerve fibres. Berol saw their evil-looking heads nuzzle into the incisions he had made, and their forked tails give a final flip as they wriggled out of sight. Then he could hear the horrid gurgling as the half-starved reptiles gnawed into the green substance.

The tenth basket was down and unloaded before Berol felt the cavern shake ominously. That meant the first batches of snakes had penetrated the nerve-trunks beyond the anesthetized area, and that the Mooneater was feeling pain. Berol knew he must expect more of these mountainous shudders, and only hoped his cavern would not collapse until he had at least got all his snakes started. At their rate of propagation Berol was confident he had enough for his purpose.

Laboriously he made his way back to the spot beneath the trunk. Basket number eleven was due. But it was not a basket that came. It was a space-suited figure—a diminutive figure that fell with a rush, and floundered for a moment in the slime on the animal floor.

"You—Fava!" Berol exclaimed.

"Hurry—oh, hurry!" the girl cried. "Come up while there is time ! Bob Tallen has come—is landing near us..."

The floor beneath them heaved mightily, flung them far apart. Berol's light jarred out, and it was several seconds before he could get it on again. When he did, he saw the place they were in had been squeezed to a third its former volume, and its shape completely changed.

He glanced upward at where the hole had been, but it had been smashed flat. Two lengths of the neochrome casing stuck out, twisted and bent almost beyond recognition. The Mooneater had had a violent convulsion, and the two humans inside it were trapped!

Walter Berol fought his way to Fava, ducking under writhing capillaries and proceeding on his hands and knees at times. Fava gasped, "He—Bob—is blasting his way in! Q-rays and flame guns... He burned down those antennae to the north of us ..."

"The blundering fool!" exclaimed Walter Berol. "The one thing he should not have done. If this brute is excited at this stage, we are all lost!"

It looked as if they were indeed, for one terrific upheaval followed another in quick succession. Twice Berol was completely buried in vile semi-liquid tissue, and only his space suit saved him from suffocation. And twice he found Fava again and clung to her. At last the shudderings and quakings diminished; then ceased altogether.

It seemed a forlorn hope, but Berol thought of trying it. He jabbed viciously at his phone button, and monotonously began calling Linholm on the surface. There was a faint chance the thing's writhings might penetrate the heavy roof of monster hide over them.

Then Berol thought he heard a voice, and a little later he got Linholm.

"Things are pretty bad, Doc," Linholm was saying. "I can't help you—not for a day or so. The derrick is down... The 'earthquake' did that... Can you stick it out until I get the derrick set up again and a new hole drilled?"

Walter Berol groaned. Bob Tallen had played hell for fair.

"What about Tallen's cruiser?" Berol demanded anxiously.

"It's gone," came the answer, so faint it could hardly be heard.

"Gone away?"

"No. Gone down. It landed, blazing away, about a thousand yards to the west of us. A bunch of them tentacle things wrapped themselves around it, and the next thing I knew ... it wasn't there. It sank plumb into the monster."

BEROL snapped off the phone and stared at Fava. Now he

had the explanation of the violent upheavals. It was Bob Tallen's

attack and the monster's reaction to it. Tallen's blasting at the

edge of the narcotized area had awakened the beast, and it had

fought back in its customary manner. The end had been the usual

one—Tallen's ship had been engulfed.

The biologist sat stunned for a moment, hardly conscious that Fava was lying alongside him, clinging. His thoughts were a strange mingling of satisfaction and despair. He had inoculated the Mooneater—it would die, in time. He felt sure of that. But he and Fava were trapped, and in the tremendous convulsions that were sure to attend the monster's death agony, they would die, too. He did not mind so much for himself. But Fava...

Then he thought of Bob Tallen and his entombed Sirius. That was another bit of dramatic irony. The would-be rescuer who had brought death instead of life—and was doomed to die himself. Now he lay a thousand yards away in the corroding acids of one of the monster's minor stomachs—.

Walter Berol jumped as if prodded with a bayonet. Inside the Sirius there might be safety! It was a race with time. Could the Mooneater digest the warship in advance of its own death struggle? Berol clambered to his feet and dragged Fava up with him.

"Come," he said, and led the girl to the west wall of their deformed cavern.

He handed her the heteraine outfit while he hung on to the flame-cutter. In a few jerky words he told her what he was trying to do, and his explanation seemed to put new life into her, though both of them knew their chances of finding the cruiser were slim. Compasses were useless inside a creature that emanated erratic magnetic waves, and everywhere there was a hopeless jumble of intertwined blood capillaries and nerve-trunks. The two victims could easily be lost in the first hundred feet.

But they plodded on. It was five hundred feet before they came to a nerve-trunk that had any green substance left in it. The illi ulli had done their work well, for in the next few hundred yards they saw many mother serpents accompanied by their huge broods of infant snakes. It was not until after that, that Fava had to use heteraine shots to paralyze the tissues ahead of them.

Berol doggedly burned away or cut the barriers that they encountered. Twice he backtracked to check his orientation. It was well he did, for he discovered on both occasions he and Fava had a tendency to veer off to the north. Aside from hacking out their path, he tried not to think at all. To do that would lead to madness, for there was really no basis for hope.

AT last they came to the tough stomach wall, and the breaching of it took the last erg of energy in the flame-gun. Berol tossed it into the muck, and jerked back the folds of tissue to allow some of the fuming acids within to flow past. He helped Fava through the hole, and they plunged on, thankful for their acid- resistant suits.

"Too late," said Berol grimly, as he looked up at the hulk that had been the crack cruiser Sirius. Her outer hull was gone, leaving only a few gaunt frames, pitted and eaten to knife- thin plates which crumbled at the touch.

Corroded decks hung limply, like damp cardboard, dripping slime. All that was left of the ship was the armored central compartment that housed the gyros and the control room.

Yet so good did this man-made thing look, dilapidated and dissolving though it was in this cavern of horrors, that both Berol and Fava instinctively drew closer to it. The biologist helped the girl climb the collapsing decks, and cleared away the slimy mud that clung there. He noticed that no more of it came, and attributed that to the paralysis of this region worked by his worms.

The armored compartment seemed to be tight, so Berol carefully scraped about one of its doors until he had laid the metal bare. Then he tapped with the handle of his knife.

There was an answering tap, after a little. In a moment the door was cautiously opened, and a helmeted officer peered out. It must have been a shock to him to see all the ship outside his compartment gone, and in its place a vague blackness lit only by the crest lamp on one of the suited figures before him. He let them in, and carefully closed the door behind.

Bob Tallen stood in the center of the control room, an expression of deep concern on his face. But as he recognized Fava, he broke into a smile, though obviously a forced one.

"Thank God we found you!" he exclaimed, striding forward as if to embrace her.

"You found us?" Fava laughed merrily. "Why, you big, clumsy, heroic lummox of a meddler! If you only knew what we've gone through to find you, just to tell you to keep your shirt on and you'll be all right!"

Bob Tallen's jaw dropped in sheer amazement. Then he caught on.

"Poor Favikins—I understand. But you're safe now..."

"Don't 'Favikins' me," the girl retorted. "I'm more right in my head than I ever was. I know ability when I see it—now! We were doing fine—Walter and I—until you came blundering in and upset everything with your stupid interference.

"We have inoculated this monster with some home-grown spirochetes of our own invention, and it's dying. In about an hour it'll heave up and throw us back onto the surface—where we would be right now, if you hadn't butted in!"

Bob Tallen could only stare at her, not knowing how to take her sudden fury.

"And let me tell you one more thing, Robert M. Tallen! I demand you return to Callisto at once, and failing that I am coming after you. Demand, indeed ! And who told you that you were anybody's intended husband?"

Just then a violent temblor shook the remainder of the ship until every fixture in it rattled deafeningly. There was a succession of quick heaves, and men had to hang on to stanchions to keep their places.

"Friend Mooneater's sick," remarked Walter Berol blandly. "Stand by for a quick rise!"

THE next fifteen seconds was a tumultuous kaleidoscope.

The core of the acid-eaten ship must have turned completely over

five or six times before it came to rest. It was an experience

such as none of the occupants ever wanted to go through

again.

Then Walter Berol boldly opened the door, and they looked out onto as fantastic a landscape as ever a troolum* addict imagined. Everywhere huge chasms had opened and thick purplish stuff was puffing up in sickly bubbles. Antennae drooped and collapsed. The Mooneater's surface billowed like a typhoon-swept ocean. The monster was dying. A quarter of a mile away lay the Sprite and her two tenders, on their sides, but otherwise unhurt.

[* A troolum addict indulges in the chewing of the troolum weed, a Martian plant with the power to affect the brain in a delusory manner. Paradoxically, though the Martian name troolum sounds as though the drug induces "true" appearing visions, the exact opposite is the fact. Troolum visions are wild, impossible, incredibly fantastic, and yet, the victim believes implicitly in all he sees. —Ed.]

"Come, Walter," said Fava. "Now that Bob's all right, we can finish what we started."

"Right-ho!" Berol grinned, and he picked the girl up in his arms and strode away across the heaving plain.

"Look at him," muttered Bob Tallen in disgust. "Showing off his strength! Some people are just too conceited to live!"