RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

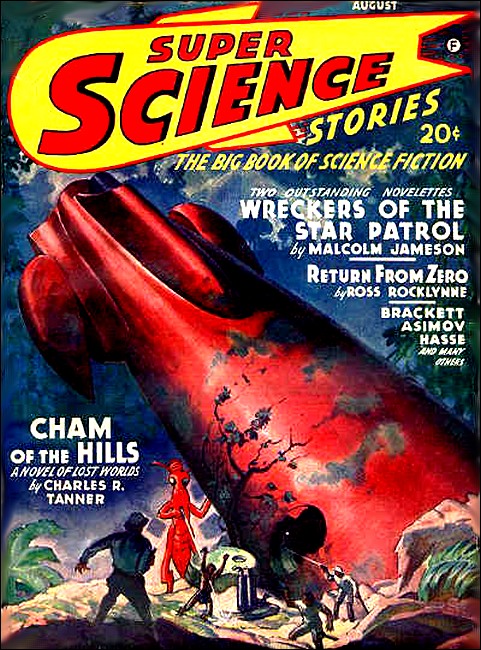

Super Science Stories, August 1942,

with "Wreckers of the Star Patrol"

"WHY should I hire you?" bellowed Captain Fennery, bunching his shaggy eyebrows into a heavy scowl. "We want no namby-pamby sissies in the Hyperion!" Bob Hartwell merely flushed and stood a little straighter. If his need had not been so great, his answer to that would have been a straight right to the jaw. Moreover, he had just told the man why he was there—of his having been in command of the neat packet, Mary Sue, of the Venus-Tellurian Line, and how that company had blown up and left him stranded on Venus.

But he restrained himself. Distasteful as working for Stellar Transport was, it was preferable to remaining in Venusport, broke and on the beach. An epidemic of paludal fever was sweeping the planet, and the crimps who supplied the swamp plantations with cheap labor were taking a heavy nightly toll. He must get off Venus at any cost.

There was an unexpected diversion, The Hyperion's second mate, a cadaverous individual of sour and spiteful mien, chose the moment to pluck his skipper's sleeve. Then he leaned over and whispered slyly in his ear. The captain shrugged his shoulders, but the mate kept on talking, smiling crookedly as he did. Presently Fennery lifted his eyes and fixed them on the young man before him with some glint of growing interest.

"Umph, may be so," he grunted, pushing the mate away. "I'll think on the matter." Then, regarding Hartwell with a curiously disturbing air of hard appraisal, he said to him, "Come back tomorrow with your duds and papers. I may be able to use you as a first after all."

"Thanks," said Hartwell briefly, and strode out of the ship.

The Stellar outfit had a bad reputation, but it was his only means of escaping the plague or slavery. He would gladly have shipped as quartermaster —or even an ALB—to get to another planet. To go as first mate was something he had not had the optimism to hope for.

So he walked with a lighter heart away from the rusty and battered old tub that lay in her launching skids, and crossed the saggy sky port to the portmaster's office where he had left his master's certificate and his dunnage.

"You're crazy—stark, raving crazy," snorted that official, a grizzled veteran of the spaceways whom Hartwell had known for a long time. "The Stellar is a gyp gang and always will be. You'd better chance the fever and the swamp crimps and wait for something safer. I never knew 'em to hire a decent man except to use him as a goat. You may come out of it with your life, but you can bet your last button that you won't come out of it with your reputation."

"I can take care of myself," said Bob Hartwell a little stiffly. He knew that every word his old friend had said was gospel, but then...

"Have you looked over that Hyperion?" stormed the portmaster. "She's hung together with paper clips, sealing wax and baling wire! The underwriters' inspector just certified her for the voyage to Mars, but I'm thinking he's the richer man today on that account—not that his employers know it."

"I've looked at her," said Hartwell, still defensive. "Sure, she's no yacht. But if she stays together long enough for me to get to Mars, that's good enough for me.'

"But the chow, man!" exploded the other. "It's condemned Patrol stores. Even the officers have to pick the weevils out. And speaking of officers, that Fennery and his mate Quorquel are a disgrace to the skylanes. Fennery is a bulldozing old sundowner and Quorquel's a slimy, conniving trickster. The only officer on the tub worth a tinker's damn is the first—hey! Didn't you say you were going as first? They've got a first mate!"

"I dunno," replied Hartwell, uncertainly. "All he said was 'maybe'."

"Watch it, son," was the portmaster's last warning. Then he shut up and put his endorsement on Hartwell's papers. Fools came and fools went. If a man ignored good advice, there was nothing an oldtimer could do.

When Bob Hartwell reached the Hyperion's berth the next day, after a night of hectic dreams, he noted that her tubes were hot and that her cargo ports were shut and sealed. The ground crew were getting clear of the searing blasts to come, but before the entry port stood Captain Fennery and beside him the portmaster with a sheaf of papers.

"Glad to see you, Hartwell," said Captain Fennery with surprising cordiality. "We're being withheld clearance for the lack of a first mate. Our Mr. Owsley indiscreetly got into a brawl with some natives in a tavern last night. The gendarmes picked him up this morning with a cut throat. Will you sign the articles quickly, please, so this gentleman will let us clear?"

The shocking news of the demise of his predecessor gave Hartwell pause, for it was confirmation of the gloomy predictions made the day before by the friendly portmaster. It matched the foreboding dreams that had kept him tossing throughout the hot, dank night. The most ominous aspect of it was that Fennery himself—perhaps Quorquel—had foreknowledge of it. Or else what did, "Come back tomorrow—may need a first mean otherwise?"

Had Owsley's death been arranged?

But Hartwell was reluctant to back out now. He had scoffed away good advice and disregarded his own better judgment. It was also not his habit to back out of commitments. So he lost but a moment in darkling consideration, then reached for the articles and signed.

A miserable specimen of the dock-rats that the Stellar Transport hired for crews was already carrying his belongings on board, and the klaxons for the take-off were screaming. He hurriedly shook the portmaster's hand, then ran into the entry port.

Once the ship was up and away, and the fleecy ball that was Venus began fading to a small bright disk astern, his misgivings began to leave him. Captain Fennery, though gruff and taciturn, made no attempt to ride him, and the odious Quorquel took out his quite obvious personal dislike in half-hidden, taunting sneers. The only other officer was the engineer— one Larsen—who kept surlily to himself, as if making the best of a dirty job that could not be evaded, wanting neither blame nor sympathy. As for the crew, Hartwell ignored them—they were the scum of the skyports of a score of planetoids. He did pick up the trick of accompanying his orders with a slug to the jaw or a pointed thrust of a booted foot; that was the way the sullen slaves of Stellar expected to be handled.

The tubes of the Hyperion were worn. At intervals one of the super-chargers would choice up and die, requiring cleaning out and repriming, but the old tub plodded on. He was amazed to see the ancient Mark I geodesic integrator still in use, but on trying it found its clumsy machinery workable and amazingly accurate. That uncouth sky-dog Fennery was a good astragator, too, he learned, as he checked the trajectory when shiny blue Tellus was abeam. They would reach Mars, all right, with their cheap freight load of Venusian teak and kegs of Attar of Loridol. And should they not, there was a well-equipped lifeboat with places for all the officers and men stowed in a blister-like compartment on the roof plate.

The Hyperion was not so hard to take.

At that, Bob Hartwell did not like the ship or anyone in her. He had already made up his mind to jump her as soon as cargo was discharged. Surely Fennery would not object, for in the dives of Ares City he could find scores of jobless mates more congenial to his ship's way of life. But object or not, his newest officer's mind was made up. Despite his frequent self-assurances to the contrary, he could not permanently down the presentment that something sinister was in the brewing.

Hartwell's mind was made up—yes.

But the plans of men do not always come to fruition; the Fates take a hand.

Thirty hours before they were due to land on Mars, Captain Fennery came bursting into his room, glowing with pleasure. He had an ethergram in his hand. Hartwell was off watch, since it was he who would have to dock her, but he sat up to hear the news. It was good news for him as well as Fennery. Stellar Transport was dropping him from its service—there would be no trouble about it after all!

"It's this way," explained the captain, showing extraordinary excitement for a man so blunt and cynical. "The company has decided this ship is not worth refitting, so they are disposing of her. They have their eye on one now lying at Mars and mean to buy it if my report of her condition is satisfactory. I'm to have command of her and I intend to take Quorquel and this crew with me as a unit. I'm sorry to have to leave you out, but the higher-ups have already promised the new first's job to one of their old hands. But never fear—I'll see that you have a berth in due time."

Hartwell could only blink. Had Stellar's vile reputation all this time been nothing but rumor? And Fennery's? Why, he couldn't have planned better himself!

The Hyperion was going to the junkpile, where she belonged— would probably be towed to one of the Scrappo asteroids where derelicts and other tough old bulks were dumped. And he was getting put out of the company with a commendation instead of the usual kick and curse. He grinned as he thought of the letter he was going to write that portmaster on Venus.

But the skipper hadn't finished with his news.

"I've got to keep you on the rolls for a week or so, though," Fennery was saying. "They want me to inspect that new ship, but I've got too much else to do. You know ships, so I'm sending you. She's lying at Moloch—that's about two hundred miles from Ares, in the Western Desert. You'll have to go by camel train, as there is a strike on among the 'coptor pilots, but you can telegraph back what you think. By the time you get back I'll have disposed of this ship and cargo and have a berth waiting for you."

"Thanks," said Bob Hartwell, wondering if miracles would ever cease.

The captain's apparent personal interest and the line's generosity were so out of keeping with the standard practice of even the well-run lines, that he could not help a twinge of suspicion as to what it was all about. It was strange that the Stellar people would buy, sight unseen, an old ship on the say-so of a one-voyage mate. It was stranger that a thug like Fennery would lift a hand to help any man.

And what of Quorquel, always flitting about in the background with his contemptuous sneer and crooked smile?

But try as he might, Hartwell could not dope out how they could hook him. So, once on Mars, he made the hard overland journey to Moloch and went over the Wanderer carefully. She was sound and well found. He reported so, taking great care to include her minor defects. She was far from new, but she would be a vast improvement over the sluggish Hyperion. Thus, he reported her, and recommended her purchase. Then he took the windy, sandy trail back to Ares.

It was at the skyport that the utmost in miracles occurred. Once more he approached the Hyperion as she lay in a launching cradle, and again her tubes glowed and smoke curled idly from them. Again her cargo-ports were closed and sealed for a voyage, and again Captain Fennery stood anxiously at her entry port alongside the local portmaster with clearance papers in his hand. Obviously she was waiting for some final matter to be cleared up and then she would soar. Then he quickened his pace. All his belongings but the clothes he wore were aboard!

"Figured you'd arrive about now," drawled Fennery, sticking out the glad hand that Hartwell heartily distrusted, "so everything's ready."

"What do you mean, ready?" Hartwell asked, puzzled. He had understood the Hyperion was to go to the junk pile.

"Loaded, provisioned, fueled, cargo and crew on board, certified and itching to go," answered Fennery. "She's been sold to the Trans-Asteroid Haulage Corporation. All she's waiting for is her skipper."

"So what?" demanded Hartwell. "I want my clothes! He'll have to hold off until I get them out."

"Hey, don't you understand?" laughed Fennery, with a bluff slap on the back. "She's had an overhaul—she's staying in service—they wanted a skipper that knew her. I recommended you. You're the captain of the Hyperion!"

"I'm damned," said Bob Hartwell, softly.

HE was damned, but not in the way he meant. All the alarm bells in his nervous system began jangling, warning as Fennery held out a paper for him to sign. It was a receipt for the Hyperion, in good repair, fully loaded and cleared for the void. Fennery insisted it was but a formality.

"Sure," said Hartwell shortly, and brushed by into the port. He wanted to have a look around before he signed anything. Things might be all right. Or they might not.

He hurried first to the tube room. It had been repaired, as Fennery had said. Three of the main driving tubes had new liners and injectors. The brightwork had been shined and there was fresh paint on the bulkheads.

It was the same way in the control room, where fresh star charts took the place of the dog-eared old ones. Hartwell examined the log, saw that there were two thousand tons of scrondium pentaluminate in the holds and provisions and fuel had been brought aboard. The invoice for the cargo hung on a hook, as did the receipts for the provisions. Everything was regular.

"I even did this for you," said Fennery, who had followed him in and was watching his inspection with satisfaction. He held out a paper. "Here's your trajectory, worked out as of five o'clock today. Callisto is your destination, and this course skips all the asteroids in between— providing you leave on the hour."

"Uh-huh," mumbled Hartwell, taking the figures. His head was swirling.

On the face of it everything was all right. His quick eye had checked it in many ways during his swift inspection. When he saw that scrondium pentaluminate was the cargo, he had glanced automatically at the holds' pressure gauges. They stood at two atmospheres—adequate to keep the volatile compound from evaporating. That was added evidence that the pentaluminate was actually in the sealed holds, for no one would have built up such a pressure for ordinary cargo.

Yet seals could be faked and invoices forged. He wondered.

"What's the tearing hurry?" he demanded, facing Fennery suddenly.

"Bonus—bonus and penalties, that's all," said he. "The Callisto refinery wants this stuff now. If it's there by the fourteenth, swell. If it's there before the fourteenth, you get a bonus of so much a day. If it's late, there'll be hell to pay, because there is a penalty for everyday lost over schedule. Trans-Asteroid had the chance and snapped it up. All they lacked was a captain familiar with the handling of the ship. That's you."

Hartwell was still regarding him dubiously. It lacked but a few minutes of five o'clock and he knew standard running times to Callisto well enough to know that if he didn't start then they'd never be there on time.

"Suit yourself," said Fennery, indifferently, half-turning, as if to go. "I thought I was doing you a favor—now you can go to hell. Trans-Asteroid isn't going to be tickled at being let down like this, and it isn't going to keep mum about it. You can pack your bag and get out of here and hunt your own job. As for me, I'm through—through with this bucket and through with you!"

"Wait," called Hartwell, as the stocky captain strode toward the port, "I'll take it and—well, thanks."

Fennery grunted, shook hands limply and went out. In his pocket he had Hartwell's signed receipt for the ship and contents.

Hartwell stared at his retreating back in a daze. He couldn't be sure whether he had been befriended, or high-pressured into making a sucker of himself. All the lurid stories of Stellar's practices and Fennery's slipperiness again flashed before his mind. Yet he had no personal grievance against company or man.

Moreover, he had signed the papers.

He snapped out of it. If there was deviltry afoot, he would have time to sniff it out before he entered the danger zone of the little planetoids. His new mates, all strangers, stood by, awaiting orders. They looked reasonably competent, and the Crew was at least no worse than the hands Fennery had taken with him.

"Take the void!" yelled Hartwell, really glad to have a command under his feet again, even if it was only the lowly, painted-up Hyperion.

The port clanged shut, the rockets swelled and roared and then came the savage lurch as the ship began to climb. Hartwell clung to the acceleration resistorstraps and watched his gauges with a critical eye. She was going up very smartly, faster than he had thought she would. She handled as daintily as if she had been in ballast.

He frowned at that thought, but then remembered the three new tubes and accessories. Of course! She would feel light.

The moment they were clear of Mars, Hartwell hastened to check the course handed him by Fennery, for the responsibility for safe navigation was his, not the former captain's. He checked it both by integrator and by hand. It was a good trajectory. Any fears he might have had that it was a trick to crash him against an asteroid vanished. Moreover, it was the shortest possible curve on which to reach Callisto, and would hit its destination smack on the nose two days before the deadline.

A more minute inspection of the ship itself uncovered nothing to give concern. As he suspected, the so-called repairs were largely superficial, but there was no evidence of sabotage, or anywhere a time bomb could be planted and not be discovered. The better things looked, the more he was mystified. He would have actually felt relieved if he could have found some deviltry that would explain Fennery's geniality.

However, he soon found other grounds for suspicion and worry—his officers and crew.

They were a disgruntled, grousing lot, all former employees of the Stellar Company, and they whispered much among themselves. He also observed that when he looked at one unexpectedly, he was quite likely to find the man regarding him with a sneer—a sneer that was always instantly erased. It was as if they regarded Hartwell as the fall-guy for some trick so obvious that no capable man would fall for it. He learned, too, that all had excellent and imperative reasons for wanting to get out of Mars—mostly concerning the police.

THEY were well past the asteroid belt when the first overt act of the crew came to his attention. In prowling about looking for trouble, Hartwell happened into the compartment where the lifeboat was stowed. To his surprise, he found his second mate and a working party of four men busily stocking it with extra water, air-flasks, and provisions. It was not a thing he had ordered.

"What's going on here?" he demanded.

"Seeing the boat's ready, that's all," answered the mate, sullenly.

"For what?" asked Hartwell, angrily, choosing for the moment to overlook the omission of the "sir." He had discovered days before that Fennery had either left him no blaster, or else the crew had concealed it before he came on board.

"For anything," answered the mate.

"It's an old Stellar custom."

"Knock it off," said Hartwell, hotly. "You're working for Trans-Asteroid now."

The mate laughed. "Hear that?" he said to the men, who were standing by, grinning. "We're working for Trans-Asteroid! Well, well, what a difference!"

A crunching blow to the jaw sent him sprawling, and the first of the three men who leaped at Hartwell was promptly jarred up against the far bulkhead and promptly went to sleep. The others decided to leave things as they were. "Pick 'em up and carry 'em down to their bunks," said Hartwell harshly, and went below.

There was no aftermath to that incident, but Hartwell was all on edge again.

He took down his almanacs and planetary tables and began checking the terminal spiral segment of his trajectory, with utmost attention to the time factor. Again everything seemed perfect—all but one item.

He discovered that their course would intersect the orbit of Hebe— the outermost of Jupiter's satellites—at exactly the moment when the little forty-mile lump of iron would arrive at the same spot.

He might have changed course then and there, but he refrained. A footnote regarding Hebe remarked that the planetoid was erratic in its motions due to the perturbations caused by its bigger sisters, and that the values given in the tables must be used with discretion. That bit of information made the advisability of changing course too soon a risky business, for he had no idea whether Hebe would be late, early, or on time at the rendezvous. And since she was so small, the change of course could be made long after she had been sighted.

Hebe came into plain view the very next day, and Hartwell began an intense study of her. After about four hours he came to the conclusion that she was slightly behind her schedule and that he would probably pass the point of collision before she arrived. He could have made certain of it by going ahead then on his main driving tubes, but since he was far into his deceleration for the planetfall on Callisto, he wanted to avoid adding momentum if he could. It would be better to wait until they were closer. Then a touch of a steering jet would throw the ship one way or the other, as needed.

He slept for four hours, for after entering the Jovian System he would dare sleep no longer, cluttered up as it was with minor moons so insignificant as not to be charted. When he woke, he saw that his predictions as to the position of Hebe were correct. Or almost, for she was on his port bow and very slowly drawing aft. He computed that the only collision danger was with her forward edge. A brief blast ahead, accompanied by a brief blast to port, would kick him ahead and to the right. The resulting delay would be insignificant.

"Blow main tubes—full speed forward!" he ordered.

They were cold and took longer than they should. But at length they sputtered into full blast and the ship began to gather more way. But the delay meant more of a turn to the right, so he yelled:

"Turn right—full power!"

"Aye," grumbled the mate at the control board. He pressed a stud. For a moment there was no response; then the shudder of the ship told that a wing tube had fired. Hartwell was watching the on rolling planetoid closely, waiting for the ship's inertia to be overcome and to see the image drop away as the ship's nose veered off to the right.

Hartwell sucked in his breath with a horrified gasp. The ship was beginning to swing all right, but the wrong way. Her bow was crawling slowly to port. Hebe was dead ahead!

The onrolling lump of iron would be at the intersection just when the Hyperion would. The ship was diving straight for her middle at full throttle!

"Right, I said, damn you!" shouted Hartwell.

"Right she is—right deflector jetting full," echoed the mate, half rising and staring at the visiscreen. Then he screamed and jabbed the general alarm, and before Hartwell could grab him, he ran out of the room yelling, "Abandon ship—collision!"

Hartwell sprang to the board, for there was still ample time to reverse the error. But jab as he would at the control buttons, there was no response. The crew had fled their stations as one man.

He muttered a curse and ran after the last of the echoing footsteps. He could not possibly handle the ship alone, and since she was doomed, he did not mean to die with her. He wanted very earnestly to stay alive and find out why this thing had been done to him.

By the time he reached the lifeboat its tubes were glowing and the panel that closed the compartment was beginning to open to the outside. He just had time to squeeze in behind the last man and get into the boat. He thrust the intervening men aside, yanked the first mate from the controls, hurled him behind him. Then he seated himself and launched the boat with a grim face.

It shot clear, and that first lashing blast blew it ten miles before he managed to set it into a rough orbit of comparative safety. It was not until then that he had time to glance at the vessel he had just left. The Hyperion was in a screaming full-power dive—or what would have been a screaming one if Hebe had had air to shrill the scream. She struck, and on the instant disappeared as a puff of vivid green flame.

He despairingly circled the tiny planet once, passing over the spot where the ship had died.

All that was to be seen were acres of glittering metal fragments. Of the two thousand tons of pentaluminate there was not a trace. There could not have been for the crystals would have flown to powder at the impact, and being under zero pressure, would have volatilized into nothingness in seconds.

BOB HARTWELL languished for three bleak months in Ionopolis' jail. He was fettered with chains, such being the barbarous custom of the harsh Ionians —descendants of Terrestrial adventurers and deportees of three centuries before.

A roving Ionian patrol vessel had witnessed the premature abandonment of the Hyperion and her crash. Within the hour they had picked up the boat, questioned its crew, and brought them all to Io. Hartwell could learn nothing more except that he was being held on the charge of barratry.

In due time the day of the trial came. It would be unfair to call the trial a farce, since the judges were upright men who conducted the proceedings with dignity. But Hartwell knew before it started that the cards were stacked against him. All parties to it were hostile to him, and he learned, to his dismay, that the one chance he might have had— cross-examination of the witnesses—had been lost. The members of the crew, pleading that they were under the necessity of making a living, had been allowed to leave depositions and depart. Their stories had agreed in every detail. By now they were scattered far and wide.

The further things proceeded, the more apparent was the deadly dilemma Hartwell found himself facing. For the prosecution was aimed not at him, but over him. A battle of giants was raging, in which he was but a miserable pawn. Counsel for the Interplanetary Underwriters tried vigorously to prove that the destruction of the Hyperion had been planned and ordered by Stellar—who, it developed, owned the dummy company which was the beneficiary of vast sums of insurance on the wreck.

Stellar, on the contrary, claimed they were lily white. Their error, if any, was in hiring a man who later proved to be incompetent.

Fennery and Quorquel, who had just a second load of scrondium pentaluminate to Callisto in their Wanderer, testified to Hartwell's "passably good" performance on the trip from Venus, but added that they recommended him to replace them solely because the ship had to leave and they could find no better. They regretted it now, but that was the way it was.

That was it. Hartwell had the hard choice of being declared incompetent or criminal. If the former, Stellar collected—if the latter, I.U. won.

Stellar won, for the I.U. man was unable to produce a scintilla of testimony showing collusion or unlawful intent. The statements left by the crew were unanimous that Hartwell got rattled when he saw Hebe loom up before him; gave conflicting orders, and then precipitately fled the ship.

In the end, Hartwell was allowed to tell his own story. The judges heard him out and, after a brief retirement, rendered the decision. They must have been impressed by his bearing, for they did not order his license cancelled. The ship was lost, they said, through "bad judgment in delaying too late to take appropriate action in the face of an emergency." That was all. The case was closed, and there could be no appeal. The damning sentence was endorsed on Hartwell's ticket in red ink. Then he was dismissed—a free man.

A free man! He walked down the marble stairs of the Tellurian Building in Ionopolis in a daze.

Free to do what—starve? Red ink on a ticket never got a man a job. He walked past the sumptuous office suites of the Tellurian Legation without noticing them, out into the dim-lit street of the city. He walked to the jail and retrieved the small amount of money that happened to be in his pockets when the crash occurred. It was all he had. After that he found a cheap lodging house near the skyport and slept on a bed of sorts for the first time in many nights.

The events of the next day confirmed his worst fears. It was the same story everywhere. No vacancies ... sorry, we don't hire strangers. We have men of our own waiting on the bench ... will let you know. Always a turndown, but never the real reason. It was not a command he had been asking for, or even a first's berth, but anything. He would have gone as a quartermaster or a tubeman, and he knew the traffic about the Jovian planets was heavy.

Late in the afternoon, when Io turned away from great, glowing Jupiter and was lit only by the pallid beams of the sun, he was told why he could not get a job on Io—or anywhere else, ever. It was a tough old skydog who; told him—a man who ran an obscure hiring hall near the skyport.

"Naw," he said, "'tain't only because you did a hitch with Stellar. Er lost a ship. Both them things hev been done before 'thout ruinin' a man. It's the I.U.'s new policy. You might ez well git wise to yourself. You're done!"

"But once I'm back home, where people know me," protested Hartwell, "I can—"

"Nope," said the old man, "'twouldn't make not a mite of difference. I just told you I can't give you a job as a groundcrew hand. I doubt if you could even get aboard a ship as a passenger, if they knew you. You're on I.U.'s secret new blacklist. They been stuck so often and so hard they're puttin' a new clause in all their policies. Clause 88. Says the insurance is null and void if the insured company employs a man that has ever caused the I.U. loss-in any capacity. Even if one of your old companies believed your story, you'd still be too expensive for 'em."

Hartwell stared back at the old skydog in blank astonishment, but he knew he had heard the truth. The companies that had refused him as a tubeman in the morning had hired other tubemen in the afternoon.

All he could do was mumble his thanks and crawl back home.

The next day a cop picked him up.

Later in the day another, and another. They wanted to know what he did for a living. All right. Get a job within three days, or else.Io, it appeared, was as tough a place as Venus.

By the third day he had the job. He signed on with an agency to be a cowhand, the Ionian version of a cattle puncher. He would be taken to the Simpson ranch, shown how to ride a tame ochtosaur, then turned loose on the range to ride herd on the wild ones. At slaughtering time he would be expected to help with the rendering of the smelly dragon fat and the tanning of the tough hides. The pay was nominal, but grub and outfit were furnished. He took it in preference to the chain gang. But it was not to be for long, for his soul burned now with but a single desire—to find Fennery and strangle the truth out of him, then go for the Stellar Transport Company.

It was for longer than he thought, for old man Simpson also ran a store and managed to keep all his employees in debt to him. But one day, as Hartwell was riding range, plodding along on the cumbersome, eight-footed, plated beast that looked like a drunk's delirious dream of a double-rhinoceros with bat wings, he became aware of something uncanny happening overhead. He looked skyward and saw them coming, at first by ones and twos, then in scores. Strange little craft of the skies that had no business being there. And they were all trying frantically to get to Ionopolis, judging from the ruinous flare of their exhausts.

Some were small inter-satellite ships and ferries, but most were tiny sky-port craft, such as tugs, yachts and tenders.

More amazing, there were planes—planes designed only for atmosphereborne flight, yet bearing the characteristic markings of Callisto and Ganymede. He saw that they had boat rockets lashed to their struts and guessed it was by means of those that they had spanned the void between the Jovian planets. One flew low enough for him to see the terror in the faces of its occupants. It was a panic! What were they fleeing from?

Presently a Callistan stratoliner got into difficulties. Its narrow wings, good enough for Callisto's heavier air, would not hold it up over Io. It staggered a moment, then fell fluttering groundward at a dangerous speed. It struck not a mile from where he sat on his steed, cradled in the natural saddle between the och's two wings and astride the dorsal hump. It flung its passengers right and left and immediately burst into flames.

Hartwell flicked on his electric goad and applied the heat to his clumsy mount's shoulder plate. The animal squalled, then flapped its bat-like wings and slowly got off the ground. In a few minutes Hartwell had dismounted and was bending over the sole survivor of the smash. He was badly hurt and had little time to live.

"Urans," the dying man gasped, trying to point back to where they had come from. "The Urans are raiding...burning, slaying, looting...warn."

That was all. The man's eyes glazed and he tried to roll over on his face. But it was enough. The Urans had not raided in two generations, but there was not a man, woman or child that did not know about them. They were a non-human race, living on dark Uranus—and they were irresistible.

They were quasi-anthropoid, resembling gorillas, except that they were covered with short feathers and had highly redeveloped brains. They had science enough to build spaceships and weapons superior to man's, but they were savages nevertheless. They never attempted to conquer or colonize. They only made forays. Two three times a century they would descend on the outposts of Saturn or Jupiter, harrying and burning, carrying away heads, loot and women. Why they took the women alive no one could explain, though perhaps it was for sacrificial purposes. What men they encountered they invariably slew, and carried away their heads and skins as trophies.

Hartwell remounted with a bound. He jerked his steed about and forced it into ungainly flight. He cared little for the Simpsons, but they were human, and there was Adele, the schoolteacher at the ranch. She had been very kind to him on the few occasions he had been there. It was unthinkable that she fall captive to the fiends from the outer planet. He must get there quickly.

The och he rode flew with exasperating slowness, and when he topped the last rise, his heart sank. A stumpy black ship was just taking off, leaving behind it huge billows of smoke mushrooming up out of the Simpson house and the hide warehouse. But there was still another on the ground, a much smaller one of reddish color. That meant that a Uran chieftain had stayed behind for some bit of last minute loot.

Then Hartwell saw what that "loot" was. Smoke began to curl from the eaves of the schoolhouse, and out of it stepped the huge Uran, bearing lightly in his arms the form of an unconscious woman. Adele! That time the och jumped, for the hot goad was applied full force.

As the och fluttered panting to the ground inside the body-strewn compound, Bob Hartwell was off in one bound, jerking his blaster out as he leaped. He knew the weapon was useless against the monster's thick hide, but it might draw his attention. The Uran was on the threshold of his ship; in a moment he would be gone.

Hartwell took careful aim and fired. The ray struck the creature squarely in the back, searing away a patch of feathers.

The Uran vented a howl of rage and threw his burden down, then whirled and glared about to see where the attack had come from. He spotted Hartwell and charged, roaring, flailing his great arms. There were weird and lethal weapons hanging to the belt he wore about his middle, but Hartwell did not expect him to use them. The Urans gloried in their fierce strength, and preferred to clasp their victims to them and with one twist of their gigantic hands wring the head from the body. So Hartwell awaited the onslaught, armed only with a cast-off och-shoe he picked up from the ground beside him. He had tossed the useless blaster away, since no man-devised ray could pierce the Uran hide.

The och-shoe was an iron affair, shaped much like a giant thumb-tack, only the pointed part was a spiral screw which worked up into the animal's horny leg. The shoe proper was a disc of iron, roughly a foot in diameter. Hartwell held it loosely behind his back until the charging foe was almost upon him. The Uran leaped, grimacing and screaming, with outstretched arms to grasp his prey.

In that brief instant, while the monster was in mid-air, Hartwell flicked the shoe to the front and planted it squarely on his own middle, set his stomach muscles, and tensed for the creature's bone-cracking grip. He ducked just as the heavy, feathered chest hit his, and felt the wind knocked out of him as he went over backward with the steel bands of arms encircling him and squeezing. For a moment things went black, and then the Uran ululated horribly and Hartwell felt the icy orange body juice of the monster oozing out upon him. He had tricked the creature into doing something he had not the strength himself to do—puncture his softest part with a shaft of twisted steel. It had been a desperate gamble—but it won!

As they rolled apart, Hartwell snatched a weapon from the Uran's belt. The chieftain staggered to his feet, clutching at his torn belly and screaming. By then Hartwell had found out how to operate the gun in his hand, and let drive with it. There was a hissing sound, a sharp kick, and the Uran's upper half silently disappeared. Hartwell left the still kicking legs on the ground behind him and darted toward the grounded ship.

Another Uran poked his snout out, only to receive the fire from his dead chieftain's gun. Hartwell blasted two more before he reached the prostrate form of Adele, but though he sprang past her and on into the ship, he saw no more. He stood for a moment in the entry port, alert for a rush. None came. He took a hasty look at the interior of the craft.

Uran science had developed on peculiar lines. Hartwell understood nothing he saw, except the nauseous bin filled with human hides and heads lately torn from their owners. He saw also the piles of booty, and selected from one of them a double handful of Saturn stones, each worth a fortune. In the emergency that lay ahead it would be well to have at hand some instantly negotiable assets. Then he opened the spigot of what seemed to be a drum of lubricant and let its contents flow out. He set the gummy liquid on fire, then ran out, caught up the unconscious Adele, and staggered through the smoke to where his och was waiting. Now to get to Ionopolis—if it could be done.

It took them four days to reach the city. The clumsy och, despite all goading, stubbornly refused to fly carrying double, so the journey was at a plodding walk.

For the first two days of the trek, the sky was full of refugee ships hurrying to what they hoped was safety. Only a few Uran ships were to be seen, only the vanguard of the horde that was sure to come as soon as they had done their vileness elsewhere. Io, it appeared, was the last place on their list.

The gates of Ionopolis were closed, and hard-faced Ionian guards turned back all but native Ionians. A clamorous mob of Tellurians, Venusians, and Martians were begging for admission within the walls, but the guards were obdurate. The city was jammed already. Io could look out only for her own.

Hartwell shouldered his way through the crowd, dragging Adele behind him. At last he got to the brutish officer in charge and whispered something to him. At first he got an angry shake of the head, but there was a flash from hand to hand, and the guard officer became more civil. The exchange of the Saturn stone had been so quickly and discreetly done that none standing by saw it. But there was a wild clamor of indignation raised by those left behind when they saw the guard summon a subordinate and have the lately arrived pair ushered through a small postern gate.

"Safety—for awhile, at least," breathed Hartwell, as they emerged inside.

Adele shuddered. She could not forget the horrible scene at the ranch.

They walked on, noticing that the city was crowded. Almost every house was shuttered up, and most had signs on them saying there was no lodging or food to be had inside. Then Hartwell spied a soldier tacking up a bulletin, and saw the crowd surge up behind him to read what the latest bad news was. He left Adele at the fringe and bucked his way in until he could see for himself. As he read it, the lines of his face tightened grimly. They had fallen out of the frying pan into the fire!

It was a proclamation by the viceroy. "Owing to the impending siege, the overcrowded condition of the city, and the shortage of food, it was imperative, the order said, for the city to rid itself at once of all non-citizens. Those foreigners who could manage to find room on board ships bound for the Inner Planets were advised to leave, but no one could be allowed into the skyport without an exit visa. All other foreigners found in the city after noon tomorrow would be given their choice of the lethal chamber or being thrust outside to take their chances with the Urans. It was a harsh measure, concluded His Excellency, but necessary. He had, however, arranged for a few 'mercy ships.'"

Hartwell backed away. Again he seized Adele by the hand, and hastened forward. The streets were packed and the going hard, but they made some progress. They had to detour four blocks to get by the Martian Embassy, for the frantic Martians were equally affected by the order, and all the ten thousand of them were trying to get passports at once. It was a foretaste of what to expect at their own legation.

There, an even larger crowd were frantically besieging the guards to let them in, and among them many aristocrats in their purple tunics, and bankers with their white and gold robes. Immense sums of money were being openly offered as bribes.

It looked like a hard nut to crack, but Hartwell cracked it. He found a back door—the one he had been taken through as a prisoner— where the crowd was small and relatively poor, and after a good deal of hushed dickering was admitted. The cost was four of the precious Saturn stones.

Two hours later he and Adele were ushered into the office of the Third Secretary. That exquisite gentleman looked Hartwell over insolently and favored Adele with a similar disdainful look. Hartwell returned the look with interest. It had been this very secretary who had committed him on the day of his arrival.

"How did you get in, you scum?" asked the secretary, in a silky voice.

"I walked in," said Hartwell, restraining himself. It was no time to display temperament. "We want visas to Tellus. Here are our passports."

The secretary did not so much as glance at them. He lay back dreamily in his chair.

"My dear fellow, don't you know there are only three ships going out tomorrow and that they are already booked to two hundred per cent capacity? There may be a third, but there are many ahead of you. Fine people, powerful people, wealthy people..."

Hartwell suppressed his craving to commit murder and drew out his remaining store of Saturn stones. There were six left. He selected a good one and held it out. The rest had to be saved for the greedy "mercy ship" people. The secretary displayed his interest by the gleam in his eyes, but, "You do not understand my friend," he said weakly. "Visas are not to be purchased." He paused and scratched his head thoughtfully. "However, I might use my influence for, shall we say, five more?"

The secretary never knew what hit him. He slithered down into his well-cushioned chair until his weight rested on the nape of his neck. And there he slept gently while the grim-faced ex-astragator rummaged his desk until he found his stamps and seals.

A moment later the passports were in order.

"Come," he said to the wide-eyed Adele, "let's go."

But he paused a moment to select the least valuable of the stones— a pale amber one of low grade, yet worth ten years' salary to its recipient. He stooped and placed it in the sleeper's hands and gently folded the fingers to encompass it.

"Appeasement," whispered Hartwell to Adele, as they tiptoed out the back door of the room. Four hours later they were on the skyfield, camped with the other lucky ones, about the fires lit near the cradles. There was one more hurdle to be jumped, but that would have to wait until the ships came in.

WHEN dawn came the Ionian soldiers routed out the half-frozen sleepers and herded them to one side of the field. The three "mercy ships" were about to land. They were three good-sized liners sent from Mars at the urgent request of the Jovian viceroy. It took them about an hour to get settled and the slag to cool enough for the people to approach. Then the grand rush began. The first ship open was immediately engulfed by a throng of frenzied refugees, each fighting to be the first in.

Two thousand of them must have been taken in when its great port clanged shut. The same thing occurred at the second, but by the time the third's turn for loading came, the soldiers had established some semblance of order. The crowd had thinned to manageable proportions, though it was evident that the remaining ship could not possibly hold more than half of them. With clubs and drawn blasters, the soldiers forced the frightened crowd to form orderly lines. Then the final loading began.

Hartwell and Adele were within a hundred places of the head of the line when the last refugee disappeared within the ship. Hartwell entertained the thought of trying to strong-arm his way forward, but a glance about at the determined military told him that that was out. It looked very much as if he were beaten again. The same thought must have occurred to many others, for the crowd began to melt and drift back toward the city. The idea of many was to secure breakfast, if food was to be had.

"Stick around," said Hartwell to Adele, as she, too, suggested they had better think of something else. "That skunk said at leastthree ships. There may be others." He lied when he said it, for what the secretary had said was that there would be only three ships and that they were booked to double capacity. But he hoped against hope that there might be another. If so, they would be on the ground. At any rate, only death lay behind them.

All the eager crowd had gone but a scant four or five hundred when the flare of breaking rockets was seen overhead. There was a scampering to get clear of the incoming ship, then a brief anxious wait, and the surge forward.

"But it's blistering my feet," wailed Adele, as they hurried across the still smoking ground.

"Damn the feet!" muttered Hartwell, picking her up and carrying her. "I can do without feet, but not without a head." They were among the first to approach the newcomer, and already the soldiers had taken charge and formed a line. This time there were only a few dozen ahead, and Hartwell knew they would get in. He saw the name of the vessel painted in fresh white letters over the entry port. It was the White Swan of Juno. It was not a liner, but an old scow of a freighter, very similar in its lines to the Wanderer he had inspected at Moloch, on Mars. As the line crawled closer, he could see a man sitting at a desk beside the port, another standing beside him with a drawn blaster, and still another armed man at the port itself.

At last Hartwell and Adele reached third place. By then he had taken in the situation. The man at the desk was Fennery, with a box before him and a large basket on the ground beside him. The box was half filled with gems and uranium briquettes, the basket with Tellurian gold-backed radium certificates. The man on guard over him was Larsen, the quartermaster; the man at the port was Quorquel. The ship was the Wanderer, as closer scrutiny of the false name showed. Underneath the paint the embossed permanent name could still be read by an inquisitive eye.

Another dilemma. Behind lay the choice of lethal chamber or sacrifice to the Urans. Ahead lay certain treachery, though the nature of it was unpredictable. But ahead also were the very men Hartwell wanted to come to grips with, and this time he was forewarned. He could not hope to cope with the forces behind him, but he might attempt once more to match wits with these crooks. He resolved to take the chance, though he realized he was involving the innocent Adele in his gamble.

"This is hay!" he heard Fennery bellow out contemptuously to a sputtering, indignant banker, who had offered a bale of countless Jovian talents. "First-water jewels, or good Tellurian cash ... no junk goes. " "B-b-but stammered the banker, despair in the face.

"G'wan," ordered Larsen, twirling his blaster. The Ionian soldier at the head of the line pushed the banker roughly out onto the field. It took real money to get aboard the merciful White Swan.

The next man up had good collateral. A pint of good Martian super- diamonds and a couple hundred thousand sols of Earth-guaranteed currency. Fennery took it all, then demanded more.

"That's all I've got," protested the man. "It's a fortune."

"Okay," said Fennery, indifferently, "but you'll be searched at the entry. What they find on you'll be extra fare for lying."

Hartwell knew that was so, for he had noticed Quorquel frisking each one as he went in, and there was another box and basket by his side. So when he confronted Fennery, he held all five of his remaining Saturn stones in his hand.

"Don't waste my time, you bum," snorted Fennery, recognizing him. He made a gesture to the soldier.

"Wait," said Hartwell, and displayed the stones. "For two, me and the young lady." He shoved Adele past him and in front.

"Not enough," grunted Fennery.

"It's twice as much per head as the guy ahead just gave you." Hartwell shot a knowing look at the Ionian soldier and delivered a friendly wink. The soldier grinned. That was enough for Hartwell. He tossed the five stones into Fennery's box and started to walk on in.

"Hey," shouted Fennery, "it's not enough, I said." But his bluster began to fade as the Ionian soldier moved forward with a threatening look. Even an Ionian can stand just so much. "But," Fennery finished lamely, "I happen to be short a mate. The stones go for her; you can work your way. Okay?"

"Okay," said Hartwell. Fennery had saved face, but at the cost of his insurance, if that was the racket this time. Also it would enable Hartwell to have access to the operating parts of the ship, a privilege which would be denied him as a paying passenger.

Hartwell underwent the loathsome Quorquel's search without batting an eye. Then he took Adele by the arm and stepped into the dark lock of the old Wanderer. Anything connected with Fennery and Quorquel was smelly; but why had they changed the old tub's name? Something most definitely stank.

"Watch your step every instant from now on," he whispered to Adele, as he led her into the musty interior. "This ship's dynamite and the personnel's poison."

Mars was the supposed destination, but the course Fennery set led far afield from the usual one.

He explained it by saying the normal course was badly cluttered with some of the tiniest of the cosmic gravel, which was very hard to predict and avoid. They would straighten up after they had pierced the Belt.

Conditions on board could only be described as awful. There was food enough, thanks to the forehold being crammed with Callistan frajiman, a sort of copra made from cactus plants. It had a vile taste and odor, but was rich in food value and vitamins. But the air was bad, and from the outset the water was rationed in driblets. Knowing Stellar's parsimonious policy in general, and that this trip was an impromptu one, Hartwell had serious doubts that many of those on board would reach the destination alive, whatever it was.

It was the living quarters that were the worst. In order to accommodate as many refugees as possible, Fennery had evidently jettisoned part of his cargo in space so that he could use the afterhold for a barracks. Hartwell recognized the odor the moment he stepped into the place. It was ochtosaur oil, which not only has a nauseous odor, but is gummy and sticky, and the drums it is transported in invariably leak. In that hold, which was always insufferably hot, due to its proximity to the driving tubes, standee bunks four tiers high had been erected. The narrow aisles that ran between could not hold all the passengers at once, so that they were compelled to lie abed. The place was almost a second Black Hole of Calcutta.

Hartwell had been given the second mate's room, which he promptly turned over to Adele and three other women. The room was designed for one occupant, but crowded as it was, it was palatial as compared with the after hold. He himself slept, when off duty, in the deck of the passage just outside the control room. He was put to work immediately, standing control watches with Larsen as helper, while Fennery and Quorquel took the other trick.

He took pains to make friends with Larsen, for he judged the fellow to have a decent streak, for all his sullen obedience to every order given him.

"There's dirty work going on here," observed Hartwell, the second night out. "It's going to be tough on that pack of suckers back aft."

Larsen grinned sourly.

"There's always dirty work afoot on a Stellar ship," he said sourly. Then added with disgust, "But this is too dirty. I'm sick of it already."

"What's the payoff?"

"I—don't—know," said Larsen, dragging thewords out worriedly. "We were three days out of Callisto with barely enough fuel to reach Mars, short of water, and short of air, what with keeping those holds up to pressure on the trip out. Then Fennery gets the S.O.S., sees dough in it, dumps the och oil over the side, and high-tails it back for Io. We couldn't get to Mars if we wanted to."

"Why did they change the name of the ship?"

"I don't know that, either."

Hartwell puckered his brow. He was going to have to do some detective work and do it fast. He did not mean to be too late, like last time.

"You going to string along?" he asked.

"Guess so. I'll have to. It's a dog's life, but they always take care of you. If you play with 'em, they cover you. If you don't—well, it's just too bad."

"I found that out."

"Yeah. There wasn't any pentaluminate on that ship you crashed. Stellar bought it, all right, and paid for it. But you went out empty. Then he loaded it and came on after. Good clean up that—my share was a grand."

"How do they split?"

"Stellar takes half; Fennery splits a third with Quorquel; we get the rest. That crew that double-crossed you got a grand apiece, too. Fennery figured you to be a good captain and that you would do just what you did. He knows Hebe like a sister, and just where she would be. It was as easy as that."

Hartwell laughed mirthlessly. Yes, it was as easy as that!

When he went off watch, Hartwell turned in after a bite to eat and pretended to be asleep. But not for long. He had previously abstracted the key to the lifeboat compartment long enough to make a copy. With that in his hand, he stole up a ladder, crossed the ship, and climbed another ladder. He unlocked the door, flicked on the light, and went in.

He was prepared for a well-stocked lifeboat—wasn't it an old Stellar custom?—but nothing like what he found. The seats for the fourteen crew members had been torn out and stacked at one side. Where they had been, there was, instead, an assemblage of packing cases and gas containers. Food, food, and more food. Spare space suits. Bottles of air at high pressures. Plenty of extra fuel. A field radio set. And seats left for only two men!

He searched further. He found a fat envelope, sealed. He weighed it in his hand, then remembered that there were plenty of such envelopes he could get at to replace it with. He tore it open and squinted at the contents. There were the insurance policies—the ship's copy of them. But more amazing, there was the Wanderer'soriginal log worked out for five days to come! He had no time to examine it, but thrust it back into the envelope and laid it away. He hunted for the jewels and money, but those evidently had not been brought up yet. Nor the blasters or ammunition. But among the tanks and boxes were the sky chests of both Fennery and Quorquel. It was to be a two-man take-off, and devil take those left behind!

For one brief moment a great and almost overpowering temptation came to him. The ship was doomed—it had inadequate air and fuel, and the water was perilously low. Those in it were either wastrels or scoundrels for the most part. Why shouldn't he slip down and quietly call Adele, and the two of them escape now while the chance was at hand?

But another thought pushed the evil one out of his head. It was not the way he wanted to deal with Fennery, nor would it exonerate him. It was easy to run, but he preferred to stay and fight. So he stopped and stood in thought for a moment. Then he resolved on his course of action. The first steps were clear, the end clouded with doubt; but it did not involve running away.

He lost no time in getting back down below. He found Larsen and shook him awake. He told him hastily—while between them they made up a dummy package to replace the stolen log and policies—roughly what was afoot.

"They take care of you, huh?" he finished. "Come, I want to show you something."

Larsen gritted his teeth when he saw, then cursed his captain and first mate fluently and at length.

"They're wary as foxes, damn 'em," he said finally, "and they've got the blasters. What can we do?"

"Plenty," said Hartwell, grimly. He had had a peep at the log he'd found and he knew he had a few days. He also was not unfamiliar with the Belt. "Gimme a hand."

That was the beginning. While Fennery and Quorquel stood their own watch together, Hartwell and Larsen were working like beavers, shuttling up and down ladders. The provision cases were broached, one by one, emptied and resealed. Their contents were stacked in Hartwell's room, much to the discomfort of the four women living there. But they were told to help themselves. Fennery's choice chow beat frajiman forty ways.

The same with water. The two stealthy rectifiers of wrong brought down all the full breakers and replaced them with others that were also full— but not of water. Ditto the air flasks. They bled several into the polluted air of the ship at large, and took them back empty. The others they switched for the ones emptied on the voyage out. They also stole most of the boat's fuel and hid it in appropriate places. The radio they did not dare remove, for there was no replacement for it, and the theft would be noticed. They contented themselves with disabling it.

"They won't enjoy their cruise, I'm thinking," remarked Larsen gleefully. He was doing something he had yearned to do for years.

"You ain't seen nothin' yet," said Hartwell, and produced a small welder. He put the deflector fins of the boat hard over and welded them that way. Then he took a wrench and cast loose the control lever, set it as if midships, and tightened it up.

That was the end of the fourth night's work. Hartwell checked over his elaborate piece of sabotage and found it good. There was one item left undone —to recover the money and jewels. It might be done, or might not.

It was the twentieth hour of the next day that Hartwell and Larsen relieved their superiors for what they knew was to be the final watch. They took over the controls as stolidly as if they had really been the dupes Fennery thought them to be. But the echoes of the steps down the corridor had hardly faded away when Hartwell jumped up.

"Remember," he warned, "if they come back and ask for me, tell 'em I got sick and had to go to the head."

Then Hartwell was off. Fennery had gone, he knew, to his room where the stuff was in the safe. Where Quorquel had gone, he could not guess. But he hurried up to the boat compartment, went in and locked the door behind him, and hid on the far side of the boat.

Presently he heard the grating of a key in the lock. Then Fennery came in. Hartwell crouched and listened. He heard the gems clink in their carrying bags as Fennery carefully stowed them underneath the seat that was to be his. After doing that, he went out.

"The money, of course," thought Hartwell, realizing that there was so much of the booty that it could not all be carried on one trip. Well, let the money go—a dozen of the best stones was worth all of it. And, he thought with sardonic satisfaction, possessing a few millions in money would add a little fillip to their discomfort while starving in the void. Moreover, he did not want to be in the boat compartment when the boat's blast was fired. He scrabbled up the jewel bags and hurried out.

He had to squeeze into the shadow of a stanchion as he heard both men coming. Both were wheezing and heavy laden, and so intent on placing their feet that they did not see him. Hartwell let them pass, then scurried on below. He had just reached the control deck when he heard the dull boom of the boat's kickoff and felt the faint tremor that shook the ship. They were on their way!

And at that moment, also, the Wanderer's own tubes sputtered, misfired, and died out. In that last ten minutes, Quorquel had been attending to a small job of sabotage of his own. Well, he was fiendishly thorough, so there was no use in hurrying about it. A minute or so would make no difference.

Hartwell dropped the jewel bags into the hands of the expectant girls.

"Stick 'em under the mattress," he directed, "and one of you be lying on it all the time. Hope it don't put kinks in your backs." And with that he was gone.

He hurriedly gave Larsen the high spots. There was no point in keeping up the watch now. If the ship was going to hit something, she would hit it, and that was that. Together they combed the vessel for what Quorquel had done.

It was plenty. The radio was smashed beyond repair, even in a sky yard. The last message that had come in was one telling of the fall of Io. The injectors and superheaters of the main driving tubes were hopelessly damaged. The momentum they had was what they would always have, neither more nor less, until they locked horns with some wandering hunk, of cosmic debris. But no, not necessarily, for they found the antiquated bow tubes still in working condition. Quorquel had not thought it necessary to spend time on them. They were smaller than the main drive and of a different model. Their injectors could not be modified to fit the rear tubes.

Hartwell learned some other discouraging facts. The retrieved water supply was so small as to help hardly at all, though there was plenty of everything else except air. The best that could be said about that was that it would support life—a headachey, listless sort of life. If he had water enough, he could electrolyze some and make air; but he hadn't. So, beyond issuing a slightly better food ration, he could do nothing to help the passengers. He did not even tell them of their predicament.

He did select six of the ablest men and call them forward. Two were engineers and one a chemist; two were in the mercantile business, but they had been enthusiastic sky-yachtsmen. The other was superintendent of a scrondium refinery. Hartwell told them something about the situation and berthed them, three in Quorquel's room, and three in Larsen's. He and Larsen, since they would be on opposite watches thereafter, moved into the skipper's cabin. That relieved the congestion aft a trifle, and gave him some helpers —if he could find any way to utilize their help.

Then he began a feverish study of the Ephemerides of the Asteroids. The more he searched the more dejected he got. There was not a single inhabited asteroid they could reach in their present condition. In ten days more the water would be gone. After that? Well, he'd have to think up something else.

IRONICALLY enough, he found an asteroid to lie dead ahead. They would crash on it inevitably unless he could work some miracle—and his fagged brain had ran out of what it takes to make miracles. The planetoid was one of the Scrappos-Scrappo IV, to be precise. It was a graveyard for ships, a handy junk pile for the disposition of derelicts so obsolete as to be not worth the cost of breaking up. From his calculations, it looked to Hartwell very much as if the weary Wanderer was about to add her rusty bones to the pile.

He scratched his head, then sent for his newly appointed civilian staff.

"In exactly seven days," he told them, "we smash on Scrappo IV. I don't think we'll actually crack up, but these freighters are cranky to handle under bow tubes alone. Then what? Any ideas?"

There was a long silence. After a bit, one of the engineers spoke up.

"I visited one of the Scrappos once. We could do worse. A great many derelicts have been dumped on them without much done in the way of stripping. Of course, space tramps visit the dumps every now and then and pick about, but we might find something worthwhile—a tube fitting here, another there, and so on. I vote we go on."

"We are going on," said Hartwell, with a grimness that was more telling than a flood of oratory could have been, "but let's not deceive ourselves. There may be spare parts enough, if we can find them. But our water will give out a day or so after our arrival. I'm not hopeful of finding that. In the meantime, you fellows circulate among the other passengers and dig out some men for working parties, if you can find any real ones among that batch of pampered aristocrats. If they talk back and tell you how much this voyage has already cost 'em, just tell 'em that from here out it'll be 'root hog, or die!' There'll be no more water for shirkers."

Hartwell resumed his anxious study of the skies ahead.

Ultimately the hour came when he had to begin deceleration. His new aides proved good men, and handled the tubes well. All in all, it was a trying maneuver, for the Scrappo was a dazzling white object, despite its heavy freckling of wreckage, and there were moments when Hartwell thought he would go blind.

But he grounded the ship in what appeared to be a blinding fog—but turned out to be particles of white dust kicked up by the blast. It stayed up for a long time, but eventually settled back to the ground, for there was no air to sustain it. But Scrappo's gravity was not so great, either, and the white dust was in no hurry to come down.

Hartwell mustered two work parties. That was all he could send out at one time, for there were only a dozen space suits on board. The engineer, Ellison, led one, and Larsen the other. Hartwell watched them leave, but without optimism. There was less than ten gallons of water left, and more than two hundred persons to divide it among. He had won, but he had lost. It looked like the end of the road, for this desolate white planetoid was the driest of deserts—soft, snowy powder.

Larsen sent two men back after a bit. They carried a strange burden. Each had a huge bag of dried clumps of rootlets with dead stems hanging limply from them. They were air plants of the genus Carnivore Veneris, insatiable consumers of carbon dioxide, formerly used on ships as air conditioners. They never died—all these needed was soaking in water and placing in foul air. Then they would burgeon gloriously until whatever hold they were placed in would look like a glen in a Venusian valley. Hartwell looked at them dubiously. It would take a quarter of the water store to revive them. Much as they needed fresh air, he told the men to dump them in the control room.

Then Ellison returned, delighted. The third ship he had visited was of the Wanderer's type, badly smashed forward, but with rear tubes intact. The fittings on at least four of them might be used, though they were somewhat larger. He thought that by interposing reducers—which could be made from other casual junk—they might be made to work.

In the meantime the chemist had been prowling around in the near vicinity. He came back looking as if he had been in a snow storm, but there was a gleam of delight in his eyes. He held out a handful of the white surface stuff of Scrappo IV.

"Here's water," he said, "enough to drown ourselves in. This stuff is gypsum. All you've got to do is heat it and rig a retort to catch the water in."

The statement galvanized his listeners to action. Ellison knew at once what to do. They would construct a huge oven under the stern of the wrecked ship with the serviceable tubes, using a tube to furnish the heat. Collector hoods, which could be made from old bulkheads, would lead the vapor to an old water tank. The passengers could turn to with improvised shovels, providing the ovens with raw gypsum, and cleaning the dehydrated stuff out at times. He thought he could do it in not more than two days.

He did. Four days later the Wanderer's tanks were overflowing. Everyone had bathed and had drunk his fill. The airplants cluttered the overhead of the ship throughout, and were spreading their tendrils farther. Now they had air and water, as well as food. They could not find a radio that could be made to work, but they did find a great quantity of rocket fuel. A half-drum here, a quarter-drum there, but the sum of them was more than enough to fill the ship's bunkers.

It was exactly a week after their landing that Hartwell lifted the Wanderer and pointed her Earthward. That was the ultimate destination of most on board, and he saw no point in going on to Mars. It was a longer voyage, but, aside from overcrowding, all on board were happy. The flabby men that had come aboard whimpering with terror were now transformed. All hands looked on the last leg of the trip as a great lark.

Hartwell spent the last day bringing his log up to date—the true log of the Wanderer. That log had been signed every day by Fennery until his desertion, and it began the day he turned back to Io. In it he had put the truth, excepting a fairy tale involving the change of name.

The other log, the one Fennery meant to take with him in the boat, was a mass of clever falsification. It made no mention of turning back after they had left Callisto. On the contrary, it was full of the details of the voyage to Mars until the very date of the desertion. As of that date there was a lurid account of an explosion in the tube room and the killing of most of the crew. A fierce fire instantly swept the ship and the officers were forced to abandon it.

Hartwell smiled a hard smile of joy. Here he had incontrovertible evidence, written in his enemy's own hand, of the vile scheme. Fennery had planned not only to double-cross the I.U. again, at the sacrifice of his crew and passengers, but his crooked company as well.

What Hartwell and Larsen had taken out of the boat was proof of that. Fennery and Quorquel had meant to go to some chosen asteroid, cache their gems and money. Then they would take the void again with only the false log and the insurance papers, and thereby give the impression of being the shipwrecked mariners they pretended to be. The company would collect the insurance, give them their cut; then they could come back and pick up their hoard.

But Hartwell had the hoard, and those who had contributed it as witnesses. Moreover, there was Larsen, now a changed man.

Luna was astern now, and the ship well down into the Earth's stratosphere. Hartwell put her into a glide until he was over the great skyport of New New York.

He landed her at quarantine, and promptly went to the office of the Director of Astronautics. In a few words he gave the outline of his story, then waited until the president of the Interplanetary Underwriters could come.

He laid the two logs on the table and told his story—both stories, that of the Hyperion as well as the Wanderer. He produced the bags of jewels.

The Director of Astronautics leaned forward and pressed a button.

"Cancel the charter of Stellar Transport," he barked into the transmitter. "Ground all ships, arrest all employees from the president down. Report back."

He turned to Hartwell.

"What else do you want?"

"I want a full exoneration in the Hyperion affair and removal from I.U.'s blacklist."

"Done," said the president of the I.U. It was his turn to grab the transmitter.

"Now to pick up Fennery and Quorquel," continued the Director. "What was their point of departure, course and speed? How much supplies did they have?"

Hartwell calmly gave the coordinates of the place of desertion. "The course?" he said, screwing up his nose. "Why, a tight, incurring spiral, with a tendency to drift in our wake. Speed? Just enough to get well clear. There was fuel enough for the initial blast, no food, no water, and what air they happened to have in their helmets."

"Why, man," exclaimed the Director, aghast, "they must be dead by now!"

"Quite probably," said Hartwell.