RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Astounding Sience Fiction, November 1944, with "Alien Envoy"

Those aliens were really alien. As totally

different from man as is a cactus plant.

Would that difference lead to inevitable extermination war—or complete lack of

conflict?

THE telecom rattled throatily, then cleared. The voice was that of Terry, bimmy fieldman.

"Hey, chief, there's something coming in over the visio you ought to have a squint at. Think it's right down our alley."

Ellwood shoved the file he was examining aside. It was the usual slush about the unrest among the talags of Darnley Valley on Venus, and dire prognostications of revolt, as if talag grousing was something new. They always bellyached, and nothing ever came of it. That's the way talags were. Anyhow, it was routine and never should have been sent up to the chief's desk. The ace bimmy—so-called from collapsing the initials of the Bureau of Interplanetary Military Intelligence—preferred not to be bothered with trifles.

"I heard you, Terry," he barked. "Let 'er flicker."

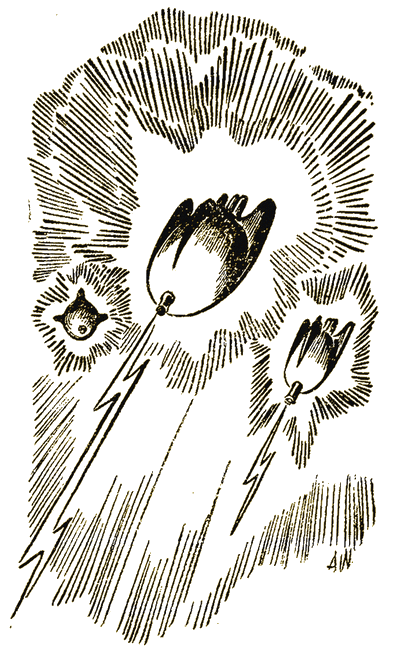

The big screen across the room came to life. For a moment there was nothing but swirling gray chaos, and then the color deepened to a velvety purple-black. The screen gained depth and the coldly burning stars came out one by one. For some seconds that was all, then an object drifted into the field. It was a bulky, teardrop shaped thing of shimmering silvery green and atop it sat a squat turret out of which peeped the blunt nose of some kind of lethal projector. But the violet aura that usually surrounded the stubby gun was missing.

That was but one detail. Ellwood gasped as he ran his eye over the image of the entire ship as it inched its way into the middle of the field of view. The after half of it glowed and sparkled with incandescent lemon-yellow fire, fading slowly to a dull orange and then a cherry-red as the tortured hull radiated its fierce heat into space. The vessel had been caught in a katatron beam. That was evident, but it was not all. There was a gaping hole through the stern out of which glowing gases were blowing, only to be instantly dissipated in the vacuum of space.

"An Ursan!" exclaimed Ellwood.

"We finally penetrated one! Who did it?"

"Commander Norcross, in the Penelope. He slammed a Mark IX torp into it, and it took. But, say, chief, that ain't all the story. The whole battle was as screwy as could be. The Ursan didn't fight back, and you know how tough they usually are. All it did was set up a terrible howl that sounded like all the static this side of Magellan rolled up in one ball. And take a gander at the co-ordinates."

Ellwood's gaze dropped to the pale white figures in the lower corner. There were three of them—celestial latitude and longitude and the angle of tilt. The wrecked Ursan was less than a million miles away—beyond the moon a little distance and up about twenty degrees.

"What in thunder was he doing this far in?" asked Ellwood. "They haven't ventured in past Jupiter in forty years."

"Search me. That's why I called you. Norcross says he's done his stuff. He's put the Ursan on the fritz, and there aren't any more around. He wants to know whether he should just call the derelict squad, kick the wreck into an orbit, or haul it in so you can have a look-see."

Ellwood fairly yelled his answers into the telecom.

"Park it in the lot by Lab Q-5, of course, you dope. Isn't this what we've been waiting for all our lives?"

The telecom crackled and died. Ellwood's fingers were racing across a panel of buttons.

"Q-5? Standby for a triple-priority job... cruiser got an Ursan... no, I mean got it... it's hanging dead in space, and it's fairly intact. They're towing it in to you, and it ought to be there by this time tomorrow. Recall Twitcherly, and be sure that Darnhurst is there. I'm leaving here right now by strato- line and I'll bring Gonzales with me. You have everything all set—complete metallurgy, chemistry, and magnetonic examination of the hull... the Valois procedure will be the best, I think. And I want a board of outplanet medicos there. We want to find out what an Ursan looks like, what makes him tick, and the rest. That means an autopsy such as never was, right down to the histology of every last cell in the monsters. That is, if they're monsters, and there's anything left of them."

"I get you, chief. Everything'll be ready to roll."

Ellwood snapped out a score of other calls. Then he sat back and relaxed.

IT had started out to be a dull, dreary day of stifling

details. Now that was changed. It was the day of days, the day of

opportunity every lummy chief before him had yearned for and

never got. What were Ursans, anyway? Where did they come from,

and what did they want? And since they were aliens from an

unknown outer world who always fought back with murderous

savagery while being at the same time virtually impregnable

themselves, what could be done to improve the technics of warfare

against them? It was a grim question that had agitated the Earth

races ever since the Ursans had first invaded their system.

Ellwood thought back over recent history. The first intruders had come in a wave of some fifty ships, dropping into the ken of the Space Patrol from the general direction of Ursa Major. On that occasion they visited most of the planets, conducting what was unmistakably a reconnaissance in spite of all the heroic space fighters could do. Dozens of the invaders were caught in the quick blasts of katatrons, but they failed to disintegrate. They merely glowed for a moment in blinding incandescence, and proceeded to carry on. They would answer the kat blast with a bolt of massive pink lightning from their own squat guns, and that would be the end of another terrestrian ship and crew. Until now not one of our vessels had managed to stay in action long enough to launch its slower but more positive torpedoes.

IT was strange. The Ursans came, and they went away, leaving

behind them the burned out hulks of the flower of the Space Navy.

A decade passed, and they did not return. Boasters claimed our

defense had taught them a lesson; they would not dare come back.

The Pollyannas took the view that it was apparent we had nothing

they wanted, therefore they were not to be feared hereafter. But

there were others who took a soberer view. The fleet was rebuilt

and strengthened. Kat pressures were built up; the speed of torps

increased. Other weapons were devised under the spur of

necessity.

The Ursans did come back. That time they came in not one wave, but ten, and each wave had more than a thousand ships. That was the year of the great running battle from past Neptune all the way in to Jupiter. The Earth forces attacked them at the perimeter of the system and hung on to the bitter end. There were many enemy casualties that time, but the surviving Ursans crowded round them and herded them into what was for them safety—down through the swirling ammonia clouds of Jupiter to a landing where no terrestrian dared follow. The tired remnants of what had been a mighty defensive fleet had no stomach for the killing gravity of Sol's greatest planet. They withdrew to lick their wounds.

For a while terror reigned on the inner planets. The Ursans did not follow up their attack, but they did not go away. It was evident they were making an advance base on Jupiter. For twenty years their ships came and went, but they did not come inside the asteroid belt again. Doggedly the dwindling Space Navy harried them, but apparently to no avail. In a duel between a Terrestrian and an Ursan, the Ursan always won. It was a dispirited, losing business.

Then came a day when the whole Ursan armada took off in one vast cloud and went back toward the upper Northern sky. Until this lone ship came wandering in, there had not been another visitation.

"I wonder," mused Ellwood, "do these creatures come in successive waves like the Goths and the Mongols and the Huns did, and is this the advance scout for a new invasion? Or what? Why did this Ursan give Norcross time to slip a torpedo into him? Asleep? Sick? Internal difficulty?"

He rose. Well, they had the ship. That was something.

ELLWOOD leaped from the plane and strode across the field. The

bimmy guards saluted and made gangway. A hundred yards from the

grounded wreck Ellwood glimpsed three sheeted forms on

stretchers.

"Who are they?" he asked.

"Tolliver, Scwheitzer, and Wang Chiang. They got theirs trying to get into the forepart—passed out in the lock. It's hot in there, and heavy, and what the Ursans use for air is out of this world. It's all over with those three lads."

Ellwood frowned. He didn't relish losing men. Moreover, men with the qualifications for being good bimmies were as scarce as the proverbial hen's teeth. Yet he was glad they had done their duty. If the forward half of the hostile ship was still intact it was important that it be left that way. The easy way would have been to blast it open, but then they would have had to reconstruct the conditions there. This way they had only to observe them.

"Did anyone come out—alive?"

"Yes. Darnhurst. He says there is at least one living Ursan still in there. He saw it crawling around in the control room, and then he got out quick."

"Did it go for him?"

"Oh, no. He just couldn't bear up against the pressure and the rest. There is some kind of gravity device operating in there and inside you have to work against 3-G's. The temperature is around a thousand, and the atmosphere is a mixture of ammonia, methane, helium, nitrous fumes, and about nine other gases that haven't yet been identified."

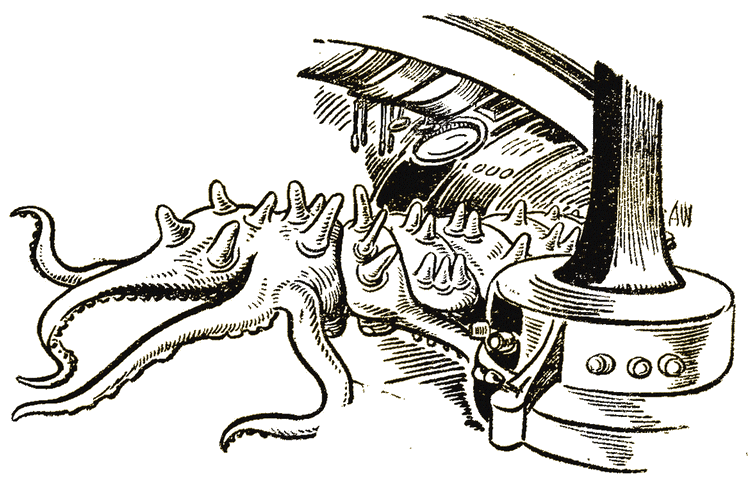

Ellwood said nothing. A gang of men were just then loading something onto a heavy truck beside the wreck with the aid of a crane. They had brought it out through the gaping hole left by the torpedo. Ellwood walked over and looked at it. It was truly a monstrous thing.

The dead Ursan partook of the qualities of an articulated deep sea turtle, crossed with an octopus and recrossed with a giant horned frog. There were seven segments, squat and heavily plated, each supported by one thick, elephantine foot no more than four inches long. Some of the segments were topped with a cluster of bony spikes, each in a different arrangement. Some were triple, some quintuple, one a simple pair. None were of the same length or thickness, and their spacing varied. The non-horned segments were two in number, one near each end. Instead of horns they were crowned with flat, lumpy superstructures from which dangled a score of octopoid antennae. Some hung lose and flabby, others were half retracted into the parent shell. They were variously tipped at their outer ends. About half ended in handlike arrangements of several fingers and an opposing thumb, others terminated in vacuum-grip cups, still others in horny, tool-like finials—chisels, socket wrenches, and the like. But of organs such as the fauna of the Solar System possessed there was no sign. There was nothing corresponding to eyes, ears or noses, nor yet the semblance of a mouth. The creatures were all plate and horn and tentacle, and incredibly massive.

"How many of these are there?"

"Three. The black gang, I guess they were. They aren't damaged much. It must have been the loss of their atmosphere that killed them."

"Rush them along to the lab, then, and let the boys there at them."

THERE followed a hectic seventy hours during which no bimmy

at that post slept more than a cat nap or ate more than a bolted

sandwich. By the time Ellwood's special harness was completed a

lot of preliminary work had been cleared away. The easiest part

of it was the accessible part of the ship itself.

The hull was of immense strength and built of an alloy that as yet defied analysis. Its tensile strength was of the order of a half a million pounds to the square inch. It was acid proof. It had no attainable melting point. It was a wonder that even a katatron could heat it white, let alone atomize it. Only the direct hit of a Mark IX torp could have punctured it.

The main drive was atomic, not much different from the terrestrial kind. The guns were simply magnetic versions of the katatron. The bimmies whose specialty was ordnance swarmed over them, delightedly taking notes. Here was something really fearsome in the way of armament. The Ursans had learned the trick of accumulating balls of magnetrons under terrific initial tension and then launching them at near the speed of light. But what was radically different was the system of control. No human, or any group of humans that could be contained in either the turret or the engine room could possibly have manipulated the scattered, queer shaped controls. None but Briarean-handed creatures could do the job. The set-up was strictly Ursan, by Ursans, for Ursans. Significantly there was nowhere a single gauge, meter, label or other visual aid to the operator.

As for the control room where the surviving monster still dwelt, whining unceasingly on forty different short-wave radio frequencies at once, Ellwood left that strictly alone. He was not finished tooling yet for his entry into it. The only precautions he took with it was to see that a reserve supply of the gases needed to replenish what the monster used was at hand if needed. But he made one startling discovery without entering the difficult chamber. One of his bimmy engineers deduced the location of the monster's air-purifying system and tapped it in mid cycle. The waste product was amazing. It was steam! Just steam. He led it into a condenser. The end product was distilled water, a fact grabbed onto with great interest by the medic gang.

They, too, had done their work, but in the end it had to be taken out of their hands. Electronicists and magnetonic sharks took over where they left off. If the beast's body chemistry was topsy-turvy, its nervous system was a thing to drive men mad. It was a mess of tangled wire—metallic wire, loaded with radium—and weird ganglia that might have served as distribution boxes. There were sets of flat, semi-bone, metalloid plates that could only be a variety of condenser. There were other screwy arrangements that were probably transformers, and the horns that adorned the spiked segments proved to be combination triodes and sending and receiving antennae. Bimmy after bimmy looked, and bugged his eyes. A thing like that just couldn't be. It violated—well, just about all the laws of electronics there were. Yet— And they would go back to work. What they dreamed of in their snatches of sleep they did not divulge, but it was wild enough to start the doctors shooting hypnophrene as a regular thing.

"There you are," said Gonzales. "It's screwy, but it is what we found."

He handed Ellwood the rough draft of the preliminary report.

THE Ursans neither ate nor drank. They breathed—breathed

the outlandish blend of gases found in their ship. There were

gills under the after edge of each segment's plate except the end

ones, and in each segment was a separate lung. The lungs

themselves were fantastic beyond expression, an impossible

blending of leathery membrane and flexible quartz tubing. In the

tubing coursed the creature's blood—a solution of silicon,

radium salts, sulphur, iron, zinc, and a score of other metals in

a mixture of acids of which nitric was the dominant member. This

blood fed the stumpy, clumsy feet and the agile tentacles. It

also fed the ganglia and nourished the other electric gadgetry.

There were sinuses filled with the liquid where it seemed to act

as an electrolyte.

"If I believe what I see here," said Ellwood tapping the document, "we are going to have to throw a lot of preconceived notions out the window. Here we have monsters with intricate nervous systems, but no brain. Yet they are intelligent, even if they do think with their reflexes. They have no organs of sight, touch, or hearing, but they evidently perceive the stars well enough to navigate, and us well enough to make us targets. This requires a radical approach."

"They perceive by means of short-wave radio," Gonzales reminded him. "That set in the corner is tuned in on the steady drone that surviving Ursan in the cruiser is sending out. I think that is what he keeps track of his surroundings by. Here's why. We have activated the nerve circuits to this pair of horns on number three segment. They gave off the identical continuous tone, and they also pick it up on the rebound. The return impulses go down to a certain ganglia and from there are fed to this set of bone plates. Unless somebody talks me down. I'm going to label those bones the retina."

Ellwood chuckled. It was not too absurd a thought. For centuries men had been using shortwave radio for night detection. Here was a living organism that used it all the time.

"Now these other spikes and horns perform similar, but different duties," continued Gonzales, putting his finger at spots on the diagram. "A current fed to this five-pronged arrangement makes an amateur [armature?] do funny things when you make noises in the vicinity. I'd call it an audio converter. The Ursans apparently don't care a hang about listening as such, but they evidently have found it useful to change what we call sound into something else that has meaning for them."

"Yes," said Ellwood, thoughtfully. "You're on the right trail. I wonder which frequencies in the band the creature uses for communication with his mates. Once we have that I'll have a jumping off point for what I intend to do."

"We'll see if we can pick it out for you, chief. There are three or four waves he uses only intermittently, and that stutteringly. It sounds very much to me as if he had been listening in on the chitchat between our ships and was trying to imitate it. Being electronically minded, the Ursans could hardly fail to have picked up our ethergrams. We have recorded a lot of the jabber already and turned it over to the cryptograph gang, but so far they haven't cracked the code. It may be as you suggest—one of those waves is the Ursan speech wave."

"Maybe, and maybe not," murmured Ellwood, "but it's a thought."

That night he made several important changes in his plans. He burned up the air with urgent messages, and before morning the first of the planes bearing rush equipment began dropping down beside the Ursan prize. By ten Ellwood was ready to test out a theory he had spent the night in evolving. He meant to go into the sealed control room and have a direct interview with the captive monster.

"Better play it safe, chief," spoke up the bimmy in charge of the guard. "That thing may act up. Sou ought to carry along a blaster."

Ellwood shook his head.

"I think," he said, smiling mildly, "that we got off on the wrong foot with these creatures right from the beginning. I don't mean with this ship or what our gang is doing about it. I mean the whole dismal history of our dealings with the Ursans. I've been thinking it over. Has it ever struck you that there has never been an instance of an Ursan ship firing on one of ours except when ours had first attacked? Could it not be that they are an essentially peaceful race of brutes and not prone to fight except in self-defense? I've come to that conclusion, and I'm staking my next move accordingly. Whatever that fellow in there was up to, coming straight toward Earth the way he was, I refuse to believe it was aggression."

"You're the boss," said the man, shrugging, but the look of uneasiness did not leave his face.

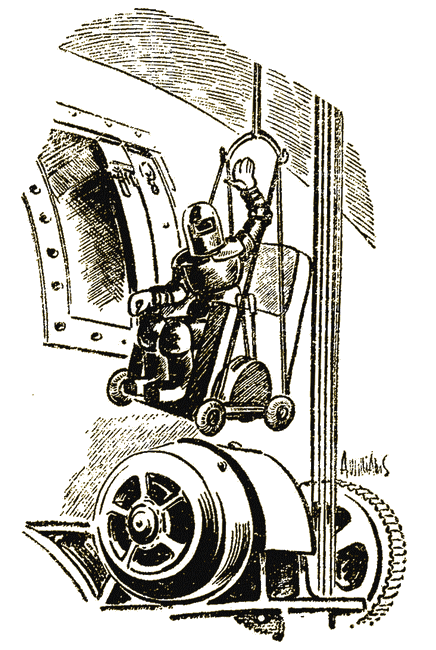

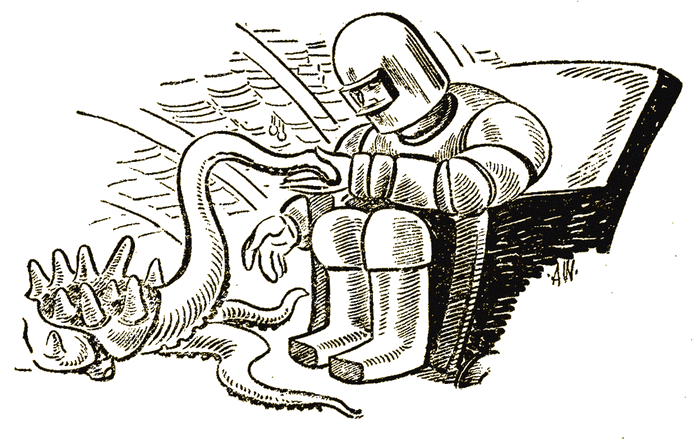

THE ponderous chair was ready. It stood on the ground just

outside the Ursan entry port, and there was a heavy crane beside

it. Ellwood let them dress him in the heavy-duty, high-resistant

spacesuit fitted with cooling coils. That would enable him to

endure the cruel temperatures so dear to his visitor, and at the

same time shield his lungs from the noxious atmosphere. Then he

let them hoist him into the chair while they rigged his accessory

tools handily about him. The chair itself had been specially

built for the occasion. It was massive and mounted on a truck

carried by thick dollies, and powered by a small atomic. In it

Ellwood could sit in relative ease despite the 3-G pull of the

control room deck.

He nodded, and the cranemen hoisted him into the open lock door. They closed it. Ellwood was in the anteroom of the visitor from the stars. The rest was up to him.

The lock grew warm, and the foul atmosphere of the ship whistled in and filled it. The pressure built up. Shortly conditions matched those in the interior. The inner lock door slid open with a hiss, and as Ellwood piloted his sturdy vehicle through it. It clicked shut behind him.

To human eyes the visibility was bad. Ellwood saw everything through a thick, milky haze, but attached to his chair were powerful lights, and after a minute or so he could see sufficiently well.

The control room was a hemispherical affair, a roundish room with a domed ceiling. Except for the floor there was hardly any part of it that was not encrusted with fantastic, intricate machinery. It rose in banks along the curving walls; it hung from the overhead. Only creatures with long multi-tentacles could have reached its scattered controls. As a piece of functional design it was doubtless splendid—but from the Ursan point of view. Ellwood swept it with one slow, wondering glance, and then put its intricacies out of his mind. In time the technicians would unravel the mysteries. His job was more comprehensive.

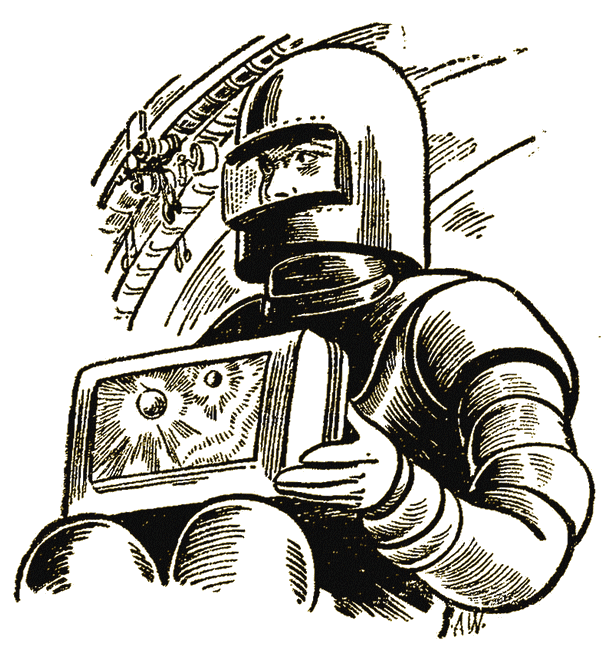

The Ursan lay motionless on the far side of the room. Ellwood could only assume that his entry had been noted. For there was not the slightest sign on the part of the monster of any change in his attitude toward his environment. Ellwood drove his chair part way across the room and stopped it there. He scanned the walls afresh for a relatively flat spot and finally found one—a huge plate that seemed to be the cover for a portion of an elaborate arrangement of magnetic gears. That was well. Ellwood relaxed and devoted his attention to the little black box in his lap. He seized its tuning knobs and began searching the short-wave band.

The two adversaries remained thus for the space of hours. Ellwood simply sat and twiddled knobs, groping for the meaning of what he heard. The monster could well have been as dead as the dissected ones in the laboratory. It never moved an inch or twitched a tentacle. But it kept on doing interesting things with its steady outpourings of radiation.

It was not long before Ellwood was aware that inside him some exceedingly queer sensations were being born. Pimple-raising thrills would creep up and down his spine; elfin fingers reached inside his eardrums and thumped them; once there were sudden shooting pains in his eyeballs; and there was a very trying period several minutes long when his heart action went crazy. Ellwood accepted it stoically. He was sure of himself and felt no fear. He was being probed, examined, mentally dissected by a diffuse electronic mind that felt its way by reflected radiation. He knew his own immense curiosity as to the nature and purposes of the thing opposite to him. It was not illogical that the feeling was mutual.

At last there was a lull. It was time for overtures, the preliminary sizings up having been completed. Ellwood flipped a switch and began sending. Dot-dash, dot-dot-dot-dash, and so on, using the wave he thought most likely the creature communicated ideas on. He sent on for one minute, then grinned grimly as he ended with the standard "Over."

The monster caught on. There was an answering rattle of meaningless ta-ta-ta-daa-daas. It made no sense, but the channel had been found. Later the cryptographers could develop the recording tapes and try their hand at unraveling the meaning. But it would not be simple. Spanish is different from Norse, but closely akin—more so, say, than Chinese. Yet all those languages expressed human thoughts in terms of human visual and aural images. How did an Ursan, a creature who had no eyes, ears, or tongue, think of the things his "brain" conceived? That was the crux of the problem.

Ellwood was eager to delve into that aspect. It was for that the extra stuff had been rushed through the stratolanes of the night, and he was prepared. For that reason he persisted with the exchange of gibberish only a little while. Then he reached into his bag of tricks and brought out item number two.

It was a small, self-contained, magazine projector. Loaded into it were the excellent films devised by the Outplanet Cultural Society for the education of the Venusian talag, the Martian phzitz, and the odd life forms that haunted the Jovian satellites. Ellwood focused it on the flat plate he was lucky enough to find. Then he started it to running.

THE golden key to successful pedagogy is the association of

ideas. That was how the OCS had solved the outland language

problem. It was true that Ursans could not see, but neither could

phzitzn. It was true that a talag is congenitally deaf, but they

learned. With an Ursan it would surely be harder, but Ellwood was

hopeful.

Nouns, the names of things, are always the obvious starting point. Ellwood's first showing was that of the sun, taken close up, near Mercury. The impressive parade of raging sunspots was there, and the streaming prominences.

"Sun," he sent, in the interplanetary code, and simultaneously uttered the word out loud. Then he diminished the diameter, showing the sun successively as it appeared on Earth, on Jupiter, and on Uranus. Each time he reiterated the noun, both in dot and dash, and by voice. He repeated the performance from the beginning, then sent "Over!"

"Sun," came back the Ursan's reply. "Over!"

Ellwood beamed beneath his helmet, though hot sweat was trickling over his eyes. The Ursan was smart. He was catching on. Now for another noun, and coupled with it a bit of semantic logic. He started the machine off again, and this time shrank the sun to a mere pinpoint of scintillating white light.

"Star," was his dual message.

"Star," said the Ursan.

Then came the planets, all of them, however different, and each Ellwood called simply planet. After that he went through them again, but that time he put the emphasis on their differences. He called them successively Mercury, Earth, Mars, and on in order. The Ursan followed. Now he was beginning to grasp the human communicative pattern. There were all-embracing words—the generic terms that included a whole class of related things. There were also specific words applying to individual variations.

Ellwood rested. Curiously, the Ursan rested, too. Perhaps he was pondering what he learned, thought Ellwood, At any rate he waited, motionless and with much of his radiation stilled. Ellwood was convinced now that his plan would work. The monster's perceptions were those of another world, yet they did perceive. That was what mattered.

Presently Ellwood repeated the show, hopeful that this time the Ursan would take another step and supply his version of the word displayed. He did not. Evidently there were no corresponding concepts in Ursan thought.

Ellwood let it go. He must be content for the time being with oneway teaching. Later—who knew? He showed next two spaceships. The first was a Terrestrian, cruiser, the other a typical Ursan craft. He established one after another the general words "spaceship," "warship," and then proceeded to differentiate into classes. The last lesson of the day was the introduction of adjectives. There were the terms Terrestrian and Ursan to define.

ELLWOOD was exhausted when he came out, and surprised to find

that he had spent but two hours within. It bad seemed far longer

under the terrible conditions suitable to Ursan life. A group of

anxious bimmies hoisted him out of the lock and released him from

his harness.

"Phew," he whistled. "Now I understand why a katatron won't work against these babies. They heat up a ship that can't be melted, but what is heat to creatures who start at one thousand as normal? And what is internal pressure increments when 3-G's is standard? I doubt if there is any way to kill these things unless it is to deprive them of the precious stink they breathe."

He rested most of the afternoon, and then went back.

In the tedious weeks of instruction that followed Ellwood made great progress. Where the monster's memory resided he could not say, but there was one. For when he finished with the concrete words he held a review. He flashed the series beginning with the sun, though without naming the objects. The Ursan faithfully supplied the appropriate nouns. He had acquired a vocabulary of more than a thousand words.

The verbs were harder, and the abstractions worse. But the course the Society had contrived was cleverly put together. Ellwood followed it religiously. He depicted various human activities, each neatly illustrated to emphasize the principle concerned. In the end he came to the concept of rivalry, and showed how rivalry grew into strife. Combat was shown in various aspects, but all of it was combat. And then Ellwood played his trump. A scene showing a fight ended in one party crawling across the lines waving a white flag. The two combatants then embraced.

At this point Ellwood got his first reaction from the monster that was more than mere parroting, It was sending agitatedly in English. It was a queer sort of English, tinged as it was with an Ursan accent, for even in code there is such a thing.

The creature got in all the words, but the syntax was his own. Some of the inversions almost defied unscrambling, but Ellwood thought he knew what the Ursan was driving at. He quit sending and listened.

"Peace!" the visitor kept repeating. "Peace. Yes, that is what I came for. We are not enemies, but friends. You are puny yet savage monsters in our eyes, but now that I have seen you at close range I see that you are not wholly bad. You do many things in clumsy ways, but we will pass over that. That is your affair. You are not to blame that your sensory equipment and mentality are as limited as they are, but I now concede that you have done remarkably well in spite of your handicaps."

"Thank you very much." said Ellwood dryly.

Being thanked seemed to disconcert the Ursan for a moment, as it was a concept not hitherto explained. But he took up his harangue again.

"I have been a prisoner in this impossible place for a long time now," sent the Ursan, "and I have listened to your teachings. Very well. Now I know about you and your strange race, and the hideous planets you choose to live on. It's my turn. Let me teach you our way. Leave off torturing me with your crude electronic devices and just sit and absorb. I assure you that what you have done to me is quite painful, but in your ignorance you could not help that. I will show you that the Ursan way is better."

Ellwood turned off his set meekly. It had not occurred to him before that mechanically generated radiation might have subtle differences in characteristics from the organically generated variety. He found himself praying that now that it was his turn and he was on the receiving end the converse effect would not be equally painful.

IT proved not to be, though there were times when Ellwood felt

he would go mad from the exquisite ecstasies that sometimes rose

to intensities amounting almost to agony. For the Ursan discarded

all dots and dashes and went straight to the source of thought.

By means of its own uncanny mechanism it managed to tune in on

the neural currents of the brain itself.

It was a dreamlike experience, verging occasionally on the nightmarish. Ellwood had a hard time later conveying some stretches of it to the Grand Council. Indeed, he had a hard time even remembering part of what he experienced, so utterly alien to human conception were many of the bizarre scenes he saw and activities witnessed.

First he had the giddy feeling one has when succumbing to a general anesthetic. It was as if his soul was being torn from his body and forced to float in space. There was never a time when he could be sure that he saw what he saw, or heard what he heard, or felt what he felt. Sensed? Divined? Perceived intuitively? Some such verb seemed more appropriate. But shortly Ellwood quit caring. He was in another world, a world so weird, so fantastic, so amazing in its extremes and distortions of ordinarily accepted laws of nature that he knew that up to then human science had no more than scratched the surface of general knowledge. He saw how chemistry, physics, all the sciences underwent profound modifications under the terrific pressures and temperatures he encountered on certain far off planets. Everything was—well, was different.

What the Ursan was giving him was a general orientation course. Ellwood was shown scores of planets compared with which Jupiter would be but small fry. He saw races of other monstrous creatures that were as different from the Ursan before him as the Ursan was from him, yet they lived in the same environment. It was analogous to the mutual enjoyment of the earth by such diverse creatures as eagles, elephants, snakes, man, fish and streptococci. Each had its own needs and duties, though each impinged at some points on the others. There was co-operation among them, and also strife. And what strife! Ellwood grew faint when he saw the fighting modes of some species of monsters.

But there was civilization, comprising manufacturing and

commerce, and attended and regulated by a sort of ethic. There

were governmental organizations, and what must have been

religious bodies. It was the industrial setup with its mighty

factories that interested Ellwood most. He saw that on those

planets certain substances quite rare with us were commonplace,

and also the contrary. Gold was abundant enough to be used for

roofing, whereas ordinary salt was extremely rare. The greatest

dearth lay in the scarcity of radium, a vital commodity since it

was to the Ursan what the more important vitamins are to us. It

was on account of radium hunger that they had been so insistent

on mining the Red Spot on Jupiter, despite our inhospitable

reception of their ships.

Imperceptibly Ellwood was brought back from the realm of the distant planets, and was kept for awhile in what can only be termed an abstract state. There were no pictures or sound in that. Only a flow of ideas. The Ursan was pouring the Ursan philosophy of inter-creature relationship into his consciousness. It was not at all a bad philosophy. It was co-operative. It recognized the rights of others to live in their own queer ways, and where they conflicted there existed an elaborate code by which they could be compromised.

At length the Ursan reached his finish. Ellwood was back in his own personality, dazed and tired, but immensely satisfied. He knew, without knowing how he felt, that henceforth intercourse between him and this monster would be easy. It would not be in dots and dashes or words in any form. It would not be simple telepathy, which after all is but the mysterious conveyances of thinkable pictures. It transcended that. It was super-telepathy, made possible by the amazing electro-magneto-neuro current command available to those with the Ursan metabolism. Somehow the raw, basic idea came over all at once. It was amorphous, instantaneous, and beyond logical analysis. But one communicated.

Ellwood knew his task was successfully completed. The wordless message given him boiled down to this:

"We, the rulers of the Armadian planets about the great sun Gol midway between you and Polaris, have looked your system over and find there is a basis for us to work for mutual advantage. We saw that you were in useful occupation of certain small planets utterly unsuitable for us. We meant to leave you alone, and have left you alone. We also found that you have two other planets, one rich and the other less so, sufficiently large to support our colonies. They are useless to you, and must always be, since your personal structure is so puny and your science elementary. We, therefore, claimed them for ourselves, resisting your ignorant and vicious attacks only in so far as we were compelled to.

"Since I find now that you are ruled by fear, and actuated at times by greed and envy, we know that you will never be satisfied with simply ceding to us what is of no value to you. You want recompense. Very well, at great risk and no small inconvenience, I have come as an emissary. In our part of the galaxy there are many small planets that would be paradisical to you, and on most of them the life forms are even more primitive than your own. If you will grant us unmolested access to Jupiter and Saturn, we will lead you to these trivial minor planets amongst us and grant you equal privileges in return. I am the envoy of Armadia. I offer you a treaty."

"I will convey your message to our ruling body," said Ellwood.

"BUT it is unthinkable," exclaimed Dilling, chairman of the

Council. "Why, think of the risks. How do we know these... these

monsters have any honor? If we allow them to build up

immense bases, strip our system of its radium, and nose about at

will, it will be but a question of time until they exterminate

us. Moreover, it is an ultimatum. We cannot entertain an

ultimatum from... from... from—"

He sputtered off into angry silence, still groping for a word beastly enough to describe the Ursan creatures as he saw them. Ellwood regarded him with quiet contempt.

"It is not an ultimatum," he said, coldly. "Alternatives were never mentioned, though there has not been a time in the past half century when the Ursans could not have seared our inner planets from pole to pole whenever they chose. I have seen their engines of destruction and they are unimaginably terrible. They are asking only that we stop beating our brains out and sacrificing our ships in futile nibbling at their radium convoys. We have had half a million fatal casualties to their three. The inmates of the ships we warmed up were only momentarily stunned. The three they lost they lost in offering this friendly gesture."

"Bah," snorted Dilling. "What is friendly about proposing to rob us of untold tons of pure radium when we put such high value on the few pounds we own?"

"The radium in question," said Ellwood, "might as well not exist as far as we are concerned. Our ships have neither the structural strength or the power to negotiate the gravity field of Jupiter, nor our men the stamina to work the mines if they could go there. You are playing dog in the manger. Yet knowing that, and our weakness, they have made an offer. They will cede us planets as valuable to us as the radium sought is to them. They do it from their sense of fair play. You will accept the treaty because you have no other choice. They will take the radium in any event and keep on slapping down any cruisers of ours that try to interfere. They offer peace instead, and commerce. Think, you other gentlemen, of what that promises. Inter-systemic commerce, not only astronomically speaking, but between systems of life that are on radically different chemical and physical levels. Trade between the tropics and the cold countries was profitable. Trade between Venus and us and Mars is profitable. Here you are offered a prospect that staggers the imagination."

Ellwood chopped off his speech and sat down. He had said what was to be said. The rest was up to the Council.

The discussion that followed was heated and lengthy, but in the end common sense won. When he left the chamber it was with authorization to negotiate.

ELLWOOD approached the Ursan ship for his final interview with

the alien ambassador. Shortly he would inherit the interesting

wreck for whatever study he wanted to make of it. For the Ursan

had broadcast to a waiting horde far out in space that terms had

been arrived at.

Shortly another Ursan ship would appear, this time with safe conduct, and take his envoy home. Meantime there were the ultimate formalities to be observed.

Ellwood carried with him the English text of the treaty. Both the Terrestrian and the Ursan copies were engraved in basic, systemic English on thick sheets of pure beryllium, a metal totally unknown on the heavy planets. He was to sign with the monster and leave him one set. In his turn the monster was to hand over a copy of the Golic version.

When Ellwood's chair rolled out onto the floor of the control room, the Ursan did what it had never done before. It moved. Inching along on its line of monopods caterpillar fashion, it slowly crossed and met Ellwood midway. Long dormant tentacles slithered out of their sockets and went to work. Two that terminated in the semblance of hands took the beryllium sheets from Ellwood, shuffled them rapidly, and returned them to him. They then reached into a locker overhead and produced a half dozen golden metallic balls. Another tentacle snaked toward a shelf and brought forward an instrument. Ellwood knew, as if by instinct, what he had to do.

The Golic text of the treaty turned out to be the oddest document in the libraries of man. It contained not words, but pure thought—thought impressed on the surface of the strange metallic spheres in the form of regenerative neuronic charges. To comprehend their meaning any intelligent human had only to run them through the instrument provided with them. It was a scanner, and as the balls rolled through, the hidden message on their surfaces suddenly and mysteriously became clear to anyone nearby.

Ellwood scanned the Golic text. It was a marvel of clarity of expression. The stipulations contained were the whole thought, without a jot of qualification or reservation. One knew what was meant. There was no room for quibbling, even if a galaxy of lawyers undertook the task. There were no shades of meaning, or misplaced commas. There were no ifs and buts and and/ors, or whereases or parties of this part and that part as cluttered up the Solar version, The Golic text said what the Solar did, but perfectly.

Ellwood signed it by merely giving his mental assent, which by some miracle of alien science became at once a part of the document. Then he put his own signature to the tin sheets, using a stylus. The Ursan signed in similar manner, but employing a special tentacle that terminated in the suitable tool. What he put down for his name was an unintelligible symbol, but it did not matter. The Solar version would always be subordinate to the Golic. It was an anachronism, a sop to legalistic tradition, a thing to be filed in archive vaults and forgotten. If ever there should arise a question, the thought spheres would provide the answer.

After the exchange of documents there was a moment of stillness. The two utterly different organisms—the Earthman and the Ursan—were as motionless as if hewn from stone. They were lost in intimate psychic rapport. There was gratitude and friendliness in it, and mutual congratulations. Each recognized that the other had done a superlative job, and each understood the purity of the other's motive. Then the mood abruptly faded, as if a connection bad been snapped. Ellwood felt completely at a loss as to how he should terminate the interview.

At that instant the Ursan did an astonishing thing. A handed tentacle crept over to Ellwood's chair and rested lightly for a moment on the padded arm. Then it slid forward past the bulbous hinge, of the wrist joint of Ellwood's armor and found his gloved hand. The handlike Ursan tentacle tip grasped Ellwood's hand and shook it solemnly, up and down. Then it dropped away, and retired to its sheath. It was good-by, and good luck.

OUT in the lock Ellwood waited for the pressure to fall, and

the good, clean, cool terrestrial air to come in. There was a

lump in his throat and his eyes were moist, and all of the

moisture was not sweat.

"How did that Ursan know we shook hands on things?" he muttered. "I never told him. Not once."