RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

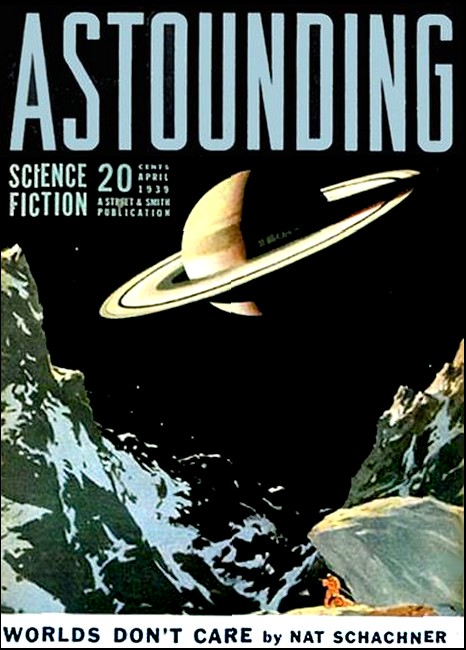

Astounding Science Fiction, April 1939, with "Catalyst Poison"

It was a wonderful idea, the Thought

Solidifier—until the idea went whacky!

OH, yes, I knew Eddie Twitterly and I knew Rags Rooney. Come to think of it, I introduced them. And I knew all about their stunt from the very beginning. It's my job to know people and what's going on. How do you think I could hold my job on the Star if I didn't?

My paper wouldn't print the low-down on the Big Day because they thought it was too fishy. That a fellow with literally millions a day income should jump the traces and behave like Eddie did, was just too much for them. It shows you how little some editors understand human nature. There was nothing fishy about it to me, because I knew Eddie so well; knew how temperamental he was.

Eddie was smart as hell. All those degrees he had and the jobs he'd held are proof of that; but he was unreliable. He couldn't stand routine. That's why they kicked him off the university faculty. He didn't fit in the factory atmosphere they have up there, the regular hours and same old grind, month in and month out. Eddie was the kind that gets steamed up over something, goes at it hammer and tongs, day and night, and then all of a sudden drops it like a hot potato. Whenever he reached the fed-up stage, he'd go on a bat; and when I say bat, I mean bat. He'd stay blotto for ten days and, likely as not, wind up in a psychopathic ward somewhere.

The psychiatrists said he had an inner conflict. He was part scientist, part artist, and it's a bad combination. His hobby was modeling. Sometimes, right in the middle of a scientific investigation, he'd get the yen to do some sculpting, and off he'd go. It muddled his work in both fields and kept him from being a big success in either. Then he'd get to thinking about that, and the next you'd know, he'd be draped across the bar somewhere telling the mahogany polisher all his troubles.

I BUMPED into him one night, shortly after he lost that

physics professorship. It was at the Spicy Club, and from the

looks of things, Eddie was celebrating his liberation from

academic life. I had Rags Rooney with me. Now Rags is an utterly

different type. He's a gambler and promoter; backs fighters and

wrestlers, ordinarily, but he'll take a part of a Broadway show,

or stake a nut inventor, or lay his money anywhere he sees a

sporting chance. Sometimes he cleans up, sometimes he loses his

shirt, but generally speaking he picks winners.

That night Eddie kept harping on some wild plan he'd just hatched to tie up his science to his art. When we found him, he was already at the talkative stage, and he proceeded to pour it on us. I was surprised to see how interested Rags got, because the whole proposition sounded screwy to me. But, after all, Rags had played long shots before and come out ahead of them, so I began to pay more attention.

Eddie's hunch, as near as I can remember it, was to build a machine based on these newfangled notions of the atom. You know the idea; that there is no such thing as matter; that everything is simply a lot of electric charges zipping and zooming around and bouncing off each other. According to him, butter and steel are just different combinations of them, revolving at different speeds. All right, he'd say, if it's electrical, you can upset it by electricity; change one to the other, or to anything else—a brick, or even a pint of red ink.

From that, he went on to tell us that feelings and thought are electricity, too. Brain cells are little batteries, and when you think, currents run back and forth in your brain. I hadn't heard that one before, but Eddie insisted that it's so; said that the current could even be metered. Well, the payoff was that he thought he could hook the two things together. If he had a machine to amplify his mental powerhouse and focus it on something—anything, even air, is always a flock of swirling electrons—he could make the electrons jump the way he wanted them to. Whatever picture was in his mind would form there.

"Just think," he said, "with my Psycho-Substantiator I could model without clay or tools. When my thoughts solidify and I see any faults and want to change them, all I have to do is think the revision. And if it comes out all right, then I imagine the material I want—marble or bronze, or even gold—and there it is! No casts to make, no chiseling, no manual work at all—a finished piece."

It must have been the crack about gold that made Rags sit up and take notice. Whatever it was, before I realized what was happening, they'd made a deal and were shaking on it. Rags was to put up the money, Eddie the brains, and split fifty-fifty on what came of it. I thought then—and I haven't changed my mind—that it was a mistake. I couldn't imagine the two of them getting together on what to do with the machine when they got it built. I spoke to Rags in the washroom about it, and warned him how flighty Eddie was.

"Hell," he said, "I've been handling sporting talent all my life and they don't come any more temperamental. This guy'll be a cinch."

I didn't see either of them for a long time—months. One night, I dropped into Rags' apartment to chin a minute with him and his missus, and the minute I got inside, I knew I oughtn't to have come. There was a first-class family row going on. I tried to duck, but she grabbed me and began laying it into me, too.

"You started all this," she said scornfully, "you and your chiseling boy friend! Thirty thousand smackers is what that no-good souse has taken this poor fish for—and look at what we get!" Boy, she was score.

She dragged me over to the table where there was a little white statuette. It was a comical thing, not bad at all; a pot-bellied little horse with big mournful eyes, made out of some white stone, but, of course, not good for much except a gimcrack.

Then she started raving again, and I learned more about Rags' home life in the next fifteen minutes than I ever dreamed of before.

"And him sounding off all the time about how he makes his living outta suckers," she snorted, "but if he hasn't been taken for a ride this time, I never saw it done. He's bought a half interest in what that dope thinks about! Imagine! Why, wine, woman, and song is all that poor louse ever thinks about, and you know what a rotten voice he has."

"What's his voice got to do with it?" Rags growled.

She gave him a dirty look. "That's why he concentrates, on the other two."

RAGS jammed on his hat and gave me the sign to come along. We

went down to Mac's place and Rags threw down a coupla slugs

before he said a word.

"Oh, everything's all right," he said in a minute, "only I see where I gotta get tough with the guy. He's not practical. The machine works like he said. What he thinks about comes out. But what the hell good is it if his mind runs to goofy doll horses? I ask you. And it could just as well been a ten-pound diamond. But that's not all. To celebrate, he goes on a four-day binge. I just found him. Two of the boys are sitting with him now in the steam room down at the gym. Soon as they cook it out of him, I'm going down and work on him."

I didn't say a word. Eddie's geared for two speeds, full ahead—his own way—and reverse. If Rags was going to put the pressure on him, I figured all he'd get would be a backfire.

They must have compromised things after a fashion. Next I heard, Rags was going around town trying to peddle a statue, a gold one this time, for a price like a couple of hundred thousand. I wanted to keep track of things, because I saw a good story coming up when the secrecy was off, so I hunted him up.

Sure enough, the statue was Eddie's second creation. It was gold, but Rags was ready to chew nails.

"The museums won't touch it," he complained; "say it's ugly. But where else will you find so much dough?"

He was right. It was ugly, terrible. A sloppy, bulging, fat, nude woman.

"Rent it to a photographer for the 'before' picture for a reducing ad," I suggested; then, seeing he was in no joking mood, I asked how it happened.

"Live and learn," said Rags, sad-like. "Like a dumbbell, I let him have his way. He was dead set to do statuary, so I says, 'O.K., but be sure to make it outta something I can hock in case the art part misses.' So he says, 'I'll do a Venus,' and I says, 'Shoot, only make her gold.' Well, he's got funny ideas about women. At the start, she was skinny enough to be an exhibit in a T. B. clinic. I kept saying, 'Put some meat on her,' thinking all the time about the weight of it when I went to sell it. He was sore at first, then he got to giggling and did what I said, and how!"

"What the hell," I told Rags. "You're sitting pretty. Go down to Wall Street and look up some of those millionaires that are moaning about the gold standard. The law says they can't hoard, but they can own golden works of art."

He took my advice and found a buyer all right, but getting that quarter of a million so easy was what ruined him. It made him greedy. Rags had made hits before, like I said, but never anything like that. Now that he had a taste of big money, he was hungry for more and hiked the limit to the sky. He was all for quantity production, and since he had plenty of cash, he began to rig for it.

In planning gold by the ton, common sense told him they couldn't go on working in laddie's third-floor studio. That plump Venus damn near caved the joists in. Rags found a place near the foot of Forty-fourth Street, in the block west of Eleventh Avenue. It was an abandoned ice plant, a big barn of a place with a dirt floor. Eddie had to dismantle his machine and take it down there, then work for two or three months making parts for the new and bigger machine with it.

The day they were ready to ride with the new equipment, Rags asked me to come down and watch it work. The place looked like a cross between an iron foundry and a movie studio. The floor was laid out in grids, four of them, each with molds for two hundred gold bricks. Pointing down at them was a circle of vacuum tubes mounted on high stands with reflectors back of them. At one side was a sort of throne where Eddie was to sit. Wires ran all over the place. Rags filled up the molds with water, and left a hose dribbling into the header so there'd be plenty of additional water to make up the difference in weight.

Eddie put up a last-minute battle about having to do something as tedious as thinking up hundreds on hundreds of little gold bars, all alike. But Rags couldn't see anything but bullion. He had sweat blood trying to get rid of the fat Venus and he wanted no more of it. At five thousand dollars apiece, the gold bricks were in handy, manageable units, and the sum of them was a fortune. Two million a day is good pay, even if you don't like the work, Rags argued. I have to admit that argument would have sold me. Eddie grumbled some more, but he focused his apparatus on the first bank of molds, put on his metal headpiece, and got on his throne.

As soon as the tubes lit up, the water began to turn pink, then a ruby red. Colloidal gold, Rags whispered. Eddie must have taught him that word. In about two hours, the first quarter off the job was done. All that time, Eddie had sat there, frowning, concentrating on the idea of twenty-four-carat gold lying in neat rows of pigs. He looked pretty tired and disgusted when he finished, but he only stopped to eat a sandwich. He growled at Rags some more, then tackled the next batch. I stuck around. You don't get to see anything like that every day.

In the afternoon, Eddie filled up Grid No. 3. He complained a lot about his head aching, but Rags wasn't listening to him. He was pacing up and down, gloating over the gold, or else sitting in a corner, figuring on the backs of envelopes. Eddie was limp by the time he got to the last set of molds, but Rags kept egging him on, yelling at him like a regular Simon Legree to hurry up, think faster and harder, so it would all be done before night. I felt sorry for Eddie, but all he did was sigh and slip his helmet on and go back to work.

It was about an hour later that things began to go sour. I heard Rags yipping, and went over to where he was. He looked scared. The molds under his feet were full of some gosh-awful, fluffy, pinkish mess.

"That's horrible," he said, sniffing the air. Then he ran over and began shaking Eddie.

Eddie had been sitting with his eyes closed, mumbling something to himself, but when Rags pounded him, he snapped out of it, shut off the juice, and came down to see what the excitement was about.

Eddie was puzzled, too, for a minute, then he began laughing.

"Tripe," he said, "that's what it is—tripe!" and then went off into another fit of laughing.

Rags was glaring at him all the time, wondering what was so funny. "Whadya mean, tripe?" he wanted to know, sore as hell.

"Why," said Eddie, as soon as he could get his breath, "I guess I must have gone nuts thinking about nothing but gold. Now I remember. I got to thinking what a lot of tripe this whole thing is; kept saying it over and over, 'This is a lot of tripe.' Ha-ha-ha! And that's what we got!"

WELL, they had it round and round. All Rags could see was a

million dollars spoiled by sheer inattention, right when his

mouth was watering for big money. But after they'd jawed awhile,

Eddie agreed to clean up the tripe, make it into gold, but later

on, after he'd had some rest. Then I asked Rags what he was going

to do with so much gold, when he had it.

"Sell it to the bank," he said, cocky as you please.

When I finished telling him about the gold laws, he was worried.

That night he went down to Washington to find out where he stood. What they said to him, I never knew; but after that, gold was out. Rags came back damning the administration like a charter member of the grass-roots conference. But he was already full of new plans. He showed me the schedule—so many tons of platinum, then so much silver, and so on. I warned him he was hunting trouble, driving Eddie like that. I thought it was a miracle that Eddie hadn't torn loose after the tripe episode. He usually did when he was fed up on anything.

"I've taken care of that," said Rags, in an offhand way. "I've got to go abroad. I'm going to Amsterdam to find out how many diamonds the market can take without cracking. While I'm gone, to be sure nothing'll slip, I've fixed it with the O'Hara Agency to keep a guard on the place, so nobody can get in or out. Eddie don't know it yet, but he'll be comfortable enough. I had a bedroom fixed up down there, and a kitchenette, and I hired a Filipino boy to stay and cook for him. He'll have to keep busy, and he can't get in trouble."

"Oh, izzat so?" I told him. "Well, you don't know Eddie. That boy could get in trouble in Alcatraz. When he gets a thirst, he can think up ways and means that'd surprise you."

Rags wouldn't listen to me, and now he's sorry. It was bad enough to lay out all that monotonous work thinking up truckloads of platinum, but to lock Eddie in that way, without even telling him about it, was just plain damn foolishness. I knew Eddie'd hit the ceiling as soon as he found it out; and whenever he did, it was going to be just too bad.

And when it happened, it was exactly that way.

I went down there one night, about a week later. It was drizzling, but I felt like a stroll, and I was worried a little about Eddie, locked up in that old plant practically alone. When I got almost to the door of it, one of O'Hara's strong-arm men stepped out from behind a signboard and flagged me down. I showed my card and told him I was a friend of Rags and knew all about the layout, but it didn't get me by. Yet I did want to know how Eddie was taking it, so I slipped the fellow a fin, and he talked.

The second night after Rags had gone, Eddie came out of the plant and started uptown. The watchmen headed him off and turned him back. Eddie didn't understand at first, and cut up quite a bit. They handled him as gently as they could, and finally shoved him through the door without roughing him up too much. It was when he heard what Rags' orders were that he went wild. He went back inside, but a couple of minutes later the door popped open and Eddie kicked the goo-goo out and threw his baggage after him.

"Tell Rooney," he yelled to the dicks, "there's more ways of choking a dog than feeding it hot butter." And with that he slammed the door and barred it.

That sounded bad to me. I wanted to know the rest, and the O'Hara man went on. The next night, they heard sounds of a wild party going on inside. That was strange, because they had kept a close watch on the place and knew nobody had gone in. But there it was—singing and laughing, plenty of whoopee. And it had been going on ever since!

I listened, but I couldn't hear a thing. Then we could make out a faint groaning.

"Oh," said the operative, "that's all right. Too much party. You know. They were fighting last night. At least, we could hear the guy bawling the girls out, and they were crying."

"Girls?" I asked. "What girls?"

"See that crack over the door?" he said. "We piled some boxes and barrels up and took a squint through there. It was something to see, I can tell you—a perfect harem, like in the movies, only more so. Five or six dames, dolled up like nobody's business, all eating off of big gold platters and passing jugs of drinks around. The only guy in there is this Twitterly, rigged out like a sultan, with a pair of 'em on his lap, handing the stuff to him. What a life! And they pay me to stand here in the rain to keep him in! Where would he want to go? He's got everything. Come on; let's hop down to the coffee pot and get on the outside of some hot chow. This joint don't need watching."

IT was raining in earnest by then, so I went back to the

Star office to file some copy. It must have been well past

midnight when I came out. The rain seemed to be over, so I

started for the subway on foot. In Forty-third Street, near

Eighth Avenue, I saw a crowd standing around the window of a

cafeteria, peeking in, and some of them were staring up at the

swinging sign out over the sidewalk. There was a ladder against

the building and I could make out a cop near the top of it

struggling with something perched on the sign. The cop was

wriggling and cussing, and whatever was up there was pecking at

him and hissing away at a great rate.

Just then the crowd let out yelps. "There's another one!" somebody said, and they all ran out to the edge of the curb, looking upward all the time. On the very end of the sign sat a fuzzy little thing, hardly bigger than your fist, but it had a tail about a yard long that hung down and curled up at the end. Its eyes shone like a cat's. Oh, more than that, they flamed—bright violet, not greenish or orange, the way a cat's do.

"He's already got four of 'em down," a fellow told me, meaning the cop.

"They're inside."

I pushed into the cafeteria, and there were some others, sure enough, sitting in a row along the counter. They seemed to be harmless enough, after you got over their looks, but what they were was something else again. They may have started out to be marmosets, but something sure went wrong with them. One was a bright-lemon color, another heliotrope, one emerald green, and the other a little of everything. They kept flipping out forked tongues, the way snakes do, and hissing. But those violet eyes were what got you. They gave you the creeps.

The cop outside came in, carrying the latest one he'd caught, a sky-blue one, with purple stripes. Two curbstone naturalists were poking at the little animals and arguing about what they could be. In the midst of that, we heard sirens outside and a police patrol car dashed up. A cop got out of the car and came into the restaurant towing a sleepy, bald-headed man who looked like he hadn't quite finished dressing.

"Do you see what I see?" the cop with the blue monkey asked him, soon as he was inside, throwing me a wink.

"Did you get me out of bed for a gag?" snapped the bald-headed man, huffy as could be. "It's a publicity stunt!" And with that he stalked out.

"A fat lot of help that zoo expert turned out to be," the cop that brought him said. "Stay with it, Clancy; the S.P.C.A. wagon'll be here soon."

I'd seen all I wanted to see, so I blew. Down the street about a hundred feet I began to feel something dragging against my shins at every step. It was dark there and I couldn't see very well, at first, but it felt like I was in high grass. I stopped and looked down. I was up to my waist in hairy, palpitating stuff! I could see a lot of little knobs swaying up and down, about the size of baseballs, and each little knob had a pair of pearly lights on it. They were dim, dim as glowworms, but there was something scary about it.

I must have yelled, because people came running up behind me, but they stopped some little distance away. As they did, the bobbing balls and the grassy stuff spread out all over the street like smoke. The way they heaved up and down and slid sideways at the same time made me sick at the stomach. Then I had a better look. They were spiders! Not the hard-boiled, tough kind of spider, with hair on its chest, but the old-fashioned wiry granddaddy longlegs—except that these must have been all of thirty inches high! I must have been pretty jittery, because the next thing I tried to do was climb a brick wall.

I found that was impractical, so I pulled myself together and began to wonder where they came from and what to do about it. They were scattering all over the street then, going away from me, and the other people were backing away from them, yelling.

Presently the emergency truck came and the boys tumbled off and started to work on the spiders. They shot a few, but soon quit that. It would have been an all-night business; there were thousands of them. Some of the cops began whanging them with nightsticks, but all a longlegs would do when it was swatted was sag a little, then come up for more. Finally, one of the cops began gathering 'em up by the legs, tying 'em in bundles with wire. The first thing I knew, the whole crowd had joined in and were having a lot of fun out of it. In a little while they had most of them tied up in shocks, like wheat. I never thought I'd live to see the day when they stacked bales of live spiders on the sidewalks of New York, but that's what they did that night.

A couple of dozen of them got away and went jiggling out into Times Square, with a lot of newsies chasing them. The cops let them corner what were left, because another call had come in. Several, in fact. Strange varmints had popped up in two or three nearby places. I didn't know what was happening, any more than anybody else. Some thought a big pet shop had been burglarized and the door left open, and some others thought this and that, but none of it made sense.

I went with the emergency truck next to Forty-fourth Street, the other side of Eighth Avenue, where a big serpent was reported to be terrorizing the neighborhood. The moment we got there, we saw the serpent, all right. We couldn't miss. It was big, and it was luminous! I should say the thing was a hundred or more feet long and a yard thick. It was made of some transparent, jellylike substance, a deep ruby red, but inside we could see its skeleton very plainly and a couple of dogs it had eaten.

The cops tried to shoot it at first, but that was a waste of time. The bullets would go through—you could see the holes for about a minute afterward. Then the holes would close up. Three or four dozen slugs didn't faze the thing. They tried to lasso it, but that didn't work either. In the first place, it was slick and slimy, and could wiggle right on through. Besides, the slime seemed to be corrosive. When a rope did stick for a few seconds, it dropped apart, charred shreds.

Next they chopped at it with axes. They picked a place about midway of the snake, or eel, or whatever you want to call it, and went to it, two men on a side. It was like chopping rubber, but they did get it in two. Then the fun began. The after piece sprouted a head, then sheered out and took the other side of the street. Both the original serpent and the detached copy stretched out to full length, and in a few minutes the cops had two snakes to worry about, instead of one.

"Forget the axes," said the lieutenant; "we gotta think of a better one than that."

It was all very exciting to me, but the main effect it had on the cops was to make 'em sore. They had nearly everything in the world on that wagon in the way of equipment, and none of it any good in a case like that. Finally somebody brought an acetylene torch into action, and that was the beginning of the end. That is, the end of that particular pair of monsters. When the flame hit 'em, the parts just hissed, shriveled up, and disappeared. In a little while there was nothing left of them except the skeletons of the two dogs and some charred meat that hadn't been digested.

A police inspector drove up in time to see the finish. "I'm glad you boys found the answer," he said, "because there's plenty more. Everything the other side of Tenth Avenue is blocked with 'em. Let's get going."

"Blocked" wasn't the word; he ought've said "buried." When we got over there, we found the fire department and about a thousand other cops already there. The avenue had been cleared, but the first four or five streets above Forty-second were packed with squirming, bellowing, hissing monsters. In some places they filled the street almost to the second-story windows. Everything that crawls, and a lot more, was all mixed up there. After one look, I knew that gelatin eel was hardly worth remembering. In this jam ahead of me were centipedes a half block long, lizards, snakes, animals that didn't look real, storybook animals, dragons, griffins, and the like. The firemen had snared a thing built along the general lines of a crocodile, but it was covered with mirror scales instead of the usual kind. It sparkled beautifully whenever it'd thresh around.

The people in the tenements were awake, and taking it hard. The women and children were on the roofs, or upper levels of the fire escapes. The men stayed lower down, some of them poking at the monsters with curtain poles, bed slats, or anything they had. On the avenue side, firemen had ladders up and were taking the people out as fast as they could. Cars and trucks kept rolling up with more men and equipment. I understood they had sent out a general alarm for all the welding-torch equipment in the city. Soon they had lines of flames working into the cross streets.

I watched them burn and slaughter the creatures for a while, but anything gets tiresome. Daylight came and I was getting hungry. I did think of Eddie several times, and wondered how he was making out, cooped up in that old plant. He was entirely cut off from me, probably surrounded by these monsters, but it never occurred to me to worry about him. I knew he had thick brick walls around him, and only one door, and that barred. I broke away and went back to midtown for some breakfast.

While I ate, I looked over the papers. The extras were not out yet, and there was nothing in them except rather facetious, wisecracking accounts of the marmoset and spider episodes. Then I heard somebody say the militia had been called out, and that the police commissioner had set up temporary headquarters in a shack in Bryant Park. I decided that was the place to go to find out what else'd happened besides what I'd seen myself.

They had already built a stockade or corral there, and in it were a number of the monsters that had been taken alive somehow or other. There was a crowd of scientists hanging around, too, and a funny-looking lot they were. I walked through them, admiring the variety of the layout of their whiskers and listening to their shop talk. Some were taking notes and making sketches and were very serious about the whole Business. Others were scoffing openly and saying it couldn't be, there were no such animals. The rest simply stood and looked. I guess they were what you'd call the open-minded ones. One bird had brought his typewriter and was sitting on a camp stool, pecking away to beat the band. I asked him what he was doing and he said he was writing a book. The title was "Phenomenal Metropolitan Fauna." Pretty good, huh? That's what I call being a live wire.

I flashed my card on the guard at the headquarters shack, and went in. A clerk was handing the commissioner a phone.

"What now?" I heard the old boy say, in a weary tone. Then he threw the phone down and tore his hair. "Pink elephants," he said, to nobody in particular, and I thought he was going to break down and cry. "Three of them, coming up Forty-second Street."

"That's going too far," said the A.P. man, tearing up his notes. "I'm through. Some Barnum is putting over the biggest hoax yet. I won't be a party to it."

I started to leave. I wanted to see how they handled the elephants, but something new was coming in over the phone, so I waited. That time it was the report about the sea serpent. Up till then I hadn't given a thought to the marine aspects of the plague, but I hung on, listening to the details.

A sea serpent had slid into the river a little above the Forty-second Street ferry and turned down the river. The battleship Texas happened to be coming up the stream at the time and sighted it. They did some fast work and got a couple of motor sailers over and began chasing it. I will have to check back the files to find out what became of that sea serpent. My recollection of it is that it got away; dived and disappeared somewhere in the upper bay. But the Texas' boats stayed with it to the end, and I heard they had a grand time, bouncing one-pounder shot off the thing's head. It had awful hard scales and they couldn't dent it. But it must have been timid, because it kept going as hard as it could and never once tried any rough stuff on the launches. One whack of that tail, and it would have been all over for them.

YOU understand by now, I guess, that those monsters were not

really ferocious; they just looked bad. They didn't bite,

most of them, but they'd jolt you into a psychosis if you were

the least weak-minded.

I suppose I seem awful dumb, now that we know what it was all about, not to have guessed earlier what was making the plague of monsters. But there was so much happening, and so fast, my brain didn't work like it ought. I might never have tumbled if Rags Rooney hadn't come rushing in, wild-eyed. He had landed an hour before from a transatlantic airplane and had been trying to get to the plant.

"Where's Eddie?" he fairly panted, grabbing my arm.

"At the plant," I told him, "by your arrangement."

"Can't you see?" moaned Rags, agonized. "He's done it again! The plant is the center of this mess, and Eddie's turning these things out with the Sicco... Psy... never mind, you know. He's got the horrors, the D.T.'s, like the doctors said he would, if he didn't lay off. We gotta stop him!"

I dragged Rags over to the commissioner and we finally made him understand. He was not what you'd call a quick thinker, but that day he'd try anything. In a minute we had the Edison substation on the line and were telling them to cut the juice off the plant.

"It's already off," a voice said. "The circuit breakers just kicked out, and won't stay in. They must have a bad overload down there, or a short."

That was the worst possible news.

"Gosh," I thought, "Eddie's already put out a coupla thousand cubic yards of assorted animals since midnight, including three elephants at one crack, without blowing any fuses. What can be coming now?"

The commissioner saw something was up, so he went with us, taking us in his car. We tore down Forty-second, blasting the air with our siren. About a block west we met the elephants coming along, docile enough, some national guardsmen leading 'em. I'd heard of pink elephants all my life, but you've got to see one to really know. I think it's the peculiar shade.

We had to park at Eleventh Avenue. There were still plenty of reptiles and minor pests packed around the plant, but flame throwers were slowly cutting their way into them.

The eaves of the plant were still oozing a few small snakes and bats, but the big door was down. The elephants had done that, I suppose. Overhead there were several army and navy planes swooping, machine-gunning the vampires, pterodactyls, and what have you that took to the air. To the side of us, a little way off, were a couple of three-inch field guns that they'd sent down in case something really big and unmanageable should come out.

We heard a big noise down at the plant, and when we looked at it again, we saw the roof begin to rise and the walls to bulge, bricks popping in every direction. Everything fell to pieces, and as soon as the dust cleared away, we were looking at the most gigantic, frightful-appearing thing there ever was, not even barring dinosaurs. It was fat and loathsome and hairy. There was no head, nothing but a gaping red mouth, full of bayonet-like teeth, with a ring of octopus tentacles around it. It began groping around with the tentacles and started picking up the small-fry monsters that were within reach. I saw it tuck away a plaid camel with one feeler while it took a coupla turns around a unicorn with another. Then the artillery let loose.

The curator fellow that was writing the book by the corral had wormed his way through the police lines and had been standing close behind us for some time. He pulled me by the sleeve.

"Beg pardon," he chirped, "but did I understand your friend to say that Twitterly was in there operating a machine by which he could telepathically control chemical changes?"

"Something like that," I admitted, not wanting to say too much.

"He was a good physicist, and chemist, too. I am surprised he permitted ethyl alcohol to enter the reaction. It's a very unreliable catalyst. Tricky, quite."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.