RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

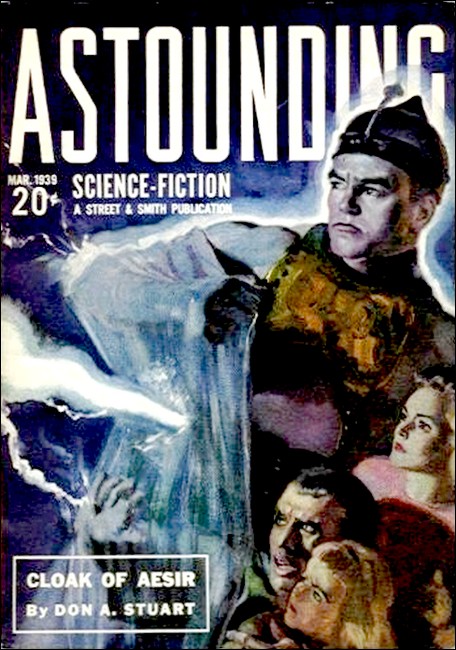

Astounding Science-Fiction, March 1939, with "Children of the 'Betsy B'"

I MIGHT never have heard of Sol Abernathy, if it hadn't been that my cousin, George, summered in Dockport, year before last. The moment George told me about him and his trick launch, I had the feeling that it all had something to do with the "Wild Ships" or "B-Boats," as some called them. Like everyone else, I had been speculating over the origin of the mysterious, unmanned vessels that had played such havoc with the Gulf Stream traffic. The suggestion that Abernathy's queer boat might shed some light on their baffling behavior prodded my curiosity to the highest pitch.

We all know, of course, of the thoroughgoing manner in which Commodore Elkins and his cruiser division recently rid the seas of that strange menace. Yet I cannot but feel regret, that he could not have captured at least one of the Wild Ships, if only a little boat, rather than sink them all ruthlessly, as he did. Who knows? Perhaps an examination of one of them might have revealed that Dr. Horatio Dilbiss had wrought a greater miracle than he ever dreamed of.

At any rate, I lost no time in getting up to the Maine coast. At Dockport, finding Sol Abernathy was simplicity itself. The first person asked pointed him out to me. He was sitting carelessly on a bollard near the end of the pier, basking in the sunshine, doing nothing in particular. It was clear at first glance that he was one of the type generally referred to as "local character." He must have been well past sixty, a lean, weathered little man, with a quizzical eye and a droll manner of speech that, under any other circumstances, might have led me to suspect he was spoofing—yet remembering the strange sequel to the Dockport happenings, the elements of his yarn have a tremendous significance. I could not judge from his language where he came from originally, but he was clearly not a Down Easter. The villagers could not remember the time, though, when he had notbeen in Dockport. To them he was no enigma, but simply a local fisherman, boatman, and general utility man about the harbor there.

I introduced myself—told him about my cousin, and my interest in his boat, the Betsy B. He was tight-mouthed at first, said he was sick and tired of being kidded about the boat. But my twenty-dollar bill must have convinced him I was no idle josher.

"We-e-e-ll," he drawled, squinting at me appraisingly through a myriad of fine wrinkles, "it's about time that somebody that really wants to know got around to astin' me about the Betsy B. She was a darlin' little craft, before she growed up and ran away to sea. I ain't sure, myself, whether I ought to be thankful or sore at that perfesser feller over on Quiquimoc. Anyhow, it was a great experience, even if it did cost a heap. Like Kiplin' says, I learned about shippin' from her."

"Do I understand you to say," I asked, "that you no longer have the launch?"

"Yep! She went—a year it'll be, next Thursday—takin' 'er Susan with W."

This answered my question, but shed little light. Susan? I saw I would do better if I let him ramble along in his own peculiar style.

"Well, tell me," I asked, "what was she like—at first—how big? How powered?"

"The Betsy B was a forty-foot steam launch, and I got 'er secondhand. She wasn't young, by any means—condemned navy craft, she was—from off the old Georgia. But she was handy, and I used 'er to ferry folks from the islands hereabouts into Dockport, and for deep-sea fishin'.

"She was a dutiful craft—" he started, but broke off with a dry chuckle, darting a shrewd sideways look at me, sizing me up. I was listening intently. "Ye'll have to get used to me talkin' of 'er like a human," he explained, apparently satisfied I was not a scoffer, "'cause if ever a boat had a soul, she had. Well, anyhow, as I said, she was a dutiful craft —did what she was s'posed to do and never made no fuss about it. She never wanted more'n the rightful amount of oil—I changed 'er from a coal-burner to an oil-burner, soon as I got 'er—and she'd obey 'er helm just like you'd expect a boat to.

"Then I got a call one day over to Quiquimoc. That perfesser feller, Doc Dilbiss, they call him, wanted to have his mail brought, and when I got there, he ast me to take some things ashore for 'im, to the express office. The widder Simpkins' boy was over there helpin' him, and they don't come any more wuthless. The Doc has some kind of labertory over there—crazy place. One time he mixed up a settin' of eggs, and hatched 'em! Made 'em himself, think of that! If you want to see a funny-lookin' lot of chickens, go over there some day."

"I shall," I said. I wanted him to stay with the Betsy Baccount, not digress. His Doc Dilbiss is no other than Dr. Horatio Dilbiss, the great pioneer in vitalizing synthetic organisms. I understand a heated controversy is still raging in the scientific world over his book, "The Secret of Life," but there is no doubt he has performed some extraordinary feats in animating his creations of the test tube. But to keep Abernathy to his theme, I asked, "What did the Simpkins boy do?"

"This here boy comes skippin' down the dock, carryin' a gallon bottle of some green-lookin' stuff, and then what does he do but trip over a cleat on the stringer and fall head over heels into the Betsy B. That bottle banged up against the boiler and just busted plumb to pieces. The green stuff in it was sorta oil and stunk like all forty. It spread out all over the insides before you could say Jack Robinson, and no matter how hard I scoured and mopped, I couldn't get up more'n a couple of rags full of it.

"You orter seen the Doc. He jumped up and down and pawed the air— said the work of a lifetime was all shot—I never knew a mild little feller like him could cuss so. The only thing I could see to do was to get outa there and take the Simpkins boy with me—it looked sure like the Doc was a-goin' to kill him.

"Naturally, I was pretty disgusted myself. Anybody can tell you I keep clean boats—I was a deep-sea sailor once upon a time, was brought up right, and it made me durned mad to have that green oil stickin' to everything. I took 'er over to my place, that other little island you see there..."— pointing outside the harbor to a small island with a couple of houses and an oil tank on it—"...and tried to clean 'er up. I didn't have much luck, so knocked off, and for two—three days I used some other boats I had, thinkin' the stink would blow away.

"When I got time to get back to the Betsy B, you coulda knocked me down with a feather when I saw she was full of vines—leastways, I call 'em vines. I don't mean she was full of vines, but they was all over 'er insides, clingin' close to the hull, like ivy, and runnin' up under the thwarts, and all over the cylinders and the boiler. In the cockpit for'ard, where the wheel was, I had a boat compass in a little binnacle. Up on top of it was a lumpy thing—made me think of a gourd—all connected up with the vines.

"I grabbed that thing and tried to pull it off. I tugged and I hauled, but it wouldn't come. But what do you think happened?"

"I haven't the faintest idea," I said, seeing that he expected an answer.

"She rared up and down, like we was outside in a force-six gale, and whistled!" Abernathy broke off and glared at me belligerently, as if he half expected me to laugh at him. Of course, I did no such thing. It was not a laughing matter, as the world was to find out a little later.

"And that was stranger than ever," he continued, after a pause, "cause I'd let 'er fires die out when I tied 'er up. Somehow she had steam up. I called to Joe Binks, my fireman, and bawled him out for havin' lit 'er off without me tellin' him to. But he swore up and down that he hadn't touched 'er. But to get back to the gourd thing—as soon as I let it go, she quieted down. I underran those vines to see where they come from. I keep callin' 'em vines, but maybe you'd call 'em wires. They were hard and shiny, like wires, and tough—only they branched every whichaway like vines, or the veins in a maple leaf. There was two sets of 'em, one set runnin' out of the gourd thing on the binnacle was all mixed up with the other set comin' out of the bottom between the boiler and the engine.

"She didn't mind my foolin' with the vines, and didn't cut up except whenever I'd touch the gourd arrangement up for'ard. The vines stuck too close to whatever they lay on to pick up, but I got a pinch-bar and pried. I got some of 'em up about a inch and slipped a wedge under. I worked on 'em with a chisel, and then a hacksaw. I cut a couple of 'em and by the Lord Harry— if they didn't grow back together again whilst I was cuttin' on the third one. I gave up! I just let it go, I was that dogtired.

"Before I left, I took a look into the firebox and saw she had the burner on slow. I turned it off, and saw the water was out of the glass. I secured the boiler, thinkin' how I'd like to get my hands on whoever lit it off.

"Next day, I had a fishin' party to take out in my schooner, and altogether, what with one thing and another, it was a week before I got back to look at the Betsy B. Now, over at my place, I have a boathouse and a dock, and behind the boathouse is a fuel oil tank, as you can see. This day, when I went down to the dock, what should I see but a pair of those durned vines runnin' up the dock like 'lectric cables. And the smoke was pourin' out of 'er funnel like everything. I ran on down to 'er and tried to shut off the oil, 'cause I knew the water was low, but the valve was all jammed with the vine wires, and I couldn't do a thing with it.

"I found out those vines led out of 'er bunkers, and mister, believe it or not, but she was a-suckin' oil right out of my big storage tank! Those vines on the dock led straight from the Betsy Binto the oil tank. When I found out I couldn't shut off the oil, I jumped quick to have a squint at the water gauge, and my eyes nearly run out on stems when I saw it smack at the right level. Do you know, that dog-gone steam launch had thrown a bunch of them vines around the injector and was a-feedin' herself? Fact! And sproutin' from the gun'le was another bunch of 'em, suckin' water from overside.

"But wouldn't she salt herself?" I asked of him, knowing that salt water is not helpful to marine boilers.

"No, sir-ree! That just goes to show you how smart she was gettin' to be. Between the tank and the injector, durned if she hadn't grown another fruity thing, kinda like a watermelon. It had a hole in one side, and there was a pile of salt by it and more spillin' out. She had rigged 'erself some sorta filter —or distiller. I drew off a little water from a gauge cock, and let it cool down and tasted it. Sweet as you'd want!

"I was kinda up against it. If she was dead set and determined to keep steam up all the time, and had dug right into the big tank, I knew it'd run into money. I might as well be usin' 'er. These vines I've been tellin' you about weren't in the way to speak of; they hung close to the planks like the veins on the back of your hand. Seein' 'er bunkers was full to the brim, I got out the hacksaw and cut the vines to the oil tank, watchin' 'er close all the time to see whether she'd buck again.

"From what I saw of 'er afterward, I think she had a hunch she was gettin' ready to get under way, and she was r'arin' to go. I heard a churnin' commotion in the water, and durned if she wasn't already kicking her screw over! just as I got the second vine cut away, she snaps her lines, and if I hadn't made a flyin' leap, she'd a gone off without me.

"I'm tellin' you, mister, that first ride was a whole lot like gettin' aboard a unbroken colt. At first she wouldn't answer her helm. I mean, I just couldn't put the rudder over, hardly, without lyin' down and pushin' with everything I had on the wheel. And Joe Binks, my fireman, couldn't do nuthin' with 'er neither—said the throttled fly wide open every time he let go of it.

"Comin' outa my place takes careful doin'—there's a lot of sunken ledges and one sandbar to dodge. I says to myself, I've been humorin' this baby too much. I remembered she was tender about that gourd thing, so the next time I puts the wheel over and she resists, I cracks down on the gourd with a big fid I'd been splicin' some five-inch line with. She blurted 'er whistle, and nearly stuck her nose under, but she let go the rudder. Seein' that I was in for something not much diffrunt from bronco bustin', I cruised 'er up and down outside the island, puttin' 'er through all sorts a turns and at various speeds. I only had to hit 'er four or five times. After that, all I had to do was to raise the fid like I was a-goin' to, and she'd behave. She musta had eyes or something in that gourd contraption. I still think that's where her brains were. It had got some bigger, too.

"I didn't have much trouble after that, for a while. I strung some live wires across the dock—I found she wouldn't cross that with 'er feelers —and managed to put 'er on some sort of rations about the oil. But I went down one night, 'round two in the mornin', and found 'er with a full head of steam. I shut everything down, leavin' just enough to keep 'er warm, and went for'ard and whacked 'er on the head, just for luck. It worked, and as soon as we had come to some sorta understanding, as you might say, I was glad she had got the way she was.

"What I mean is, after she was broke, she was a joy. She learned her way over to Dockport, and, after a coupla, trips, I never had to touch wheel or throttle. She'd go back and forth, never makin' a mistake. When you think of the fogs we get around here, that's something. And, o' course, she learned the Rules of the Road in no time. She knew which side of a buoy to take —and when it came to passin' other boats, she had a lot better judgment than I have.

"Keepin' 'er warm all the time took some oil, but it didn't really cost me any more, 'cause I was able to let Joe go. She didn't need a regular engineer, nohow—in fact, her and Joe fought so, I figured it'd be better without him. Then I took 'er out and taught 'er how to use charts."

Abernathy stopped and looked at me cautiously. I think this must be the place that some of his other auditors walked out on him, or started joshing, because he had the slightly embarrassed look of a man who feels that perhaps he had gone a little too far. Remembering the uncanny way in which the Wild Ships had stalked the world's main steamer lanes, my mood was one of intense interest.

"Yes," I said, "go on."

"I'd mark the courses in pencil on the chart, without any figures, and prop it up in front of the binnacle. Well, that's all there was to it. She'd shove off, and follow them courses, rain, fog, or shine. In a week or so, it got so I'd just stick a chart up there and go on back and loll in the stern sheets, like any payin' passenger.

"If that'd been all, I'd a felt pretty well off, havin' a trained steam launch that'd fetch and carry like a dog. I didn't trust 'er enough to send 'er off anywhere by herself, but she coulda done it. All my real troubles started when I figured I'd paint 'er. She was pretty rusty—lookin', still had the old navy-gray paint on—what was left of it.

"I dragged 'er up on the marine railway I got over there, scraped 'er down and got ready to doll 'er up. The first jolt I got was when I found she was steel, 'stead of wood. And it was brand, spankin' new plate, not a pit or a rust spot anywhere. She'd been pumpin' sea water through those vines, eatin' away the old rotten plankin' and extractin' steel from the water. Somebody —I've fergotten who 'twas—told me there's every element in sea water if you can get it out. Leastways, that's how I account for it-she was wood when I bought 'er. Later on you'll understand better why I say that-she could do some funny things.

"The next thing that made me sit up and take notice was the amount of paint it took. I've painted hundreds of boats in my time, and know to the pint what's needed. Well I had to send to town for more; I was shy about five gallons. Come to think about it, she did look big for a fortyfooter, so I got out a tape and laid it on 'er. She was fifty-eight feet over all! And she'd done it so gradual I never even noticed!

"But—to get along. I painted 'er nice and white, with a red bottom and a catchy green trim, along the rail and canopy. We polished 'er bright—work and titivated 'er generally. She did look nice, and new as you please—and in a sense she was, with the bottom I was tellin' you about. You'd a died a-laughin' though, if you'd been with me the next day, when we come over here to Dockport. The weather was fine and the pier was full of summer people. As soon as we come up close, they began cheerin' and callin' out to me how swell the Betsy B looked in 'er new colors. Well, there was nothin' out of the way about that. I went on uptown and 'tended to my business, came back after a while, and we shoved off.

"But do you think that blamed boat would leave there right away? No, sir! Like I said, lately I'd taken to climbin' in the stern sheets and givin' 'er her head. But that day, we hadn't got much over a hundred yards beyond the end of the pier, when what does she do but put 'er rudder over hard and come around in an admiral's sweep with wide-open throttle, and run back the length of the pier. She traipsed up and down a coupla times before I tumbled to what was goin' on. It was them admirin' people on the dock and the summer tourists cheerin' that went to 'er head.

"All the time, people was yellin' to me to get my wild boat outa there, and the constable threatenin' to arrest me 'cause I must be drunk to charge up and down the harbor thataway. You see, she'd gotten so big and fast she was settin' up plenty of waves with 'er gallivantin', and all the small craft in the place was tearin' at their lines, and bangin' into each other something terrible. I jumped up for'ard and thumped 'er on the skull once or twice, 'fore I could pull 'er away from there.

"From then on, I kept havin' more'n more to worry about. There was two things, mainly—her growin', and the bad habits she took up. When she got to be seventy feet, I come down one mornin' and found a new bulkhead across the stern section. It was paper-thin, but it was steel, and held up by a mesh of vines an each side. In two days more it was as thick, and looked as natural, as any other part of the boat. The funniest part of that bulkhead, though, was that it put out rivet heads—for appearance, I reckon, because it was as solid as solid could be before that.

"Then, as she got to drawin' more water, she begun lengthenin' her ladders. They was a coupla little two-tread ladders—made it easier for the womenfolks gettin' in and out. I noticed the treads gettin' thicker V thicker. Then, one day, they just split. Later on, she separated them, evened 'em up. Those was the kind of little tricks she was up to all the time she was growin'.

"I coulda put up with 'er growin' and all—most any feller would be tickled to death to have a launch that'd grow into a steam yacht—only she took to runnin' away. One mornin' I went down, and the lines was hangin' off the dock, parted like they'd been chafed in two. I cranked my motor dory and started out looking for the Betsy B. I sighted 'er after a while, way out to sea, almost to the horizon.

"Didja ever have to go down in the pasture and bridle a wild colt? Well, it was like that. She waited, foxylike, lyin' to, until I got almost alongside, and then, doggone if she didn't take out, hell bent for Halifax, and run until she lost 'er steam! I never woulda caught 'er if she hadn't run out of oil. At that, I had to tow 'er back, and a mean job it was, with her throwing 'er rudder first this way and that. I finally got plumb mad and went alongside and whanged the livin' daylights outa that noodle of hers.

"She was docile enough after that, but sulky, if you can imagine how a sulky steam launch does. I think she was sore over the beatin' I gave 'er. She'd pilot 'erself, all right, but she made some awful bad landin's when we'd come in here, bumpin' into the pier at full speed and throwin' me off my feet when I wasn't lookin' for it. It surprised me a lot, 'cause I knew how proud she was—but I guess she was that anxious to get back at me, she didn't care what the folks on the dock thought.

"After that first time, she ran away again two or three times, but she allus come back of 'er own accord—gettin' in to the dock dead tired, with nothing but a smell of oil in her bunkers. The fuel bill was gettin' to be a pain.

"The next thing that come to plague me was a fool government inspector. Said he'd heard some bad reports and had come to investigate! Well, he had the Betsy B's pedigree in a little book, and if you ever saw a worried look on a man, you shoulda seen him while he was comparin' 'er dimensions and specifications with what they was s'posed to be. I tried to explain the thing to him—told him he could come any week and find something new. He was short and snappy—kept writin' in his little book—and said that I was a-goin' to hear from this."

"You can see I couldn't help the way the Betsy B was growin'. But what got my goat was that I told him she had only one boiler, and when we went to look, there was two, side by side, neatly cross- connected, with a stop on each one, and another valve in the main line. I felt sorta hacked over that—it was something I didn't know, even. She'd done it overnight.

"The inspector feller said I'd better watch my step, and went off, shakin' his head. He as much as gave me to understand that he thought my Betsy B papers was faked and this here vessel stole. The tough part of that idea, for him, was that there never had been anything like 'er built. I forgot to tell you that before he got there, she'd grown a steel deck over everything, and was startin' out in a big way to be a regular ship.

"I was gettin' to the point when I wished she'd run away and stay. She kept on growin', splittin' herself up inside into more and more compartments. That woulda been all right, if there'd been any arrangement I could use, but no human would design such a ship. No doors, or ports, or anything. But the last straw was the lifeboat. That just up and took the cake.

"Don't get me wrong. It's only right and proper for a yacht, or anyway, a vessel as big as a yacht, to have a lifeboat. She was a hundred and thirty feet long then, and rated one. But any sailor man would naturally expect it to be a wherry, or a cutter at one outside. But, no, she had to have a steam launch, no less!

"It was a tiny little thing, only about ten feet long, when she let me see it first. She had built a contraption of steel plates on 'er upper deck that I took to be a spud-locker, only I mighta known she wasn't interested in spuds. It didn't have no door, but it did have some louvers for ventilation, looked like. Tell you the truth, I didn't notice the thing much, 'cept to see it was there. Then one night, she rips off the platin', and there, in its skids, was this little steam launch!

"It was all rigged out with the same vine layout that the Betsy B had runnin' all over 'er, and had a name on it—the Susan B. It was a dead ringer for the big one, if you think back and remember what she looked like when she come outa the navy yard. Well, when the little un was about three weeks old—and close to twenty feet long, I judge— the Betsy B shoved off one mornin', in broad daylight, without so much as by-your-leave, and goes around on the outside of my island. She'd tore up so much line gettin' away for 'er night jamborees, I'd quit moorin' 'er. I knew she'd come back, 'count o' my oil tank. She'd hang onto the dock by her own vines.

"I run up to the house and put a glass on 'er. She was steamin' along slow, back and forth. Then she reached down with a sorta crane she'd growed and picked that Susan B up, like you'd lift a kitten by the scruff o' the neck, and sets it in the water. Even where I was, I could hear the Susan B pipin', shrill-like. Made me think of a peanut-wagon whistle. I could see the steam jumpin' out of 'er little whistle. I s'pose it was scary for 'er, gettin' 'er bottom wet, the first time. But the Betsy B kept goin' along, towin' the little one by one of 'er vines.

"She'd do something like that two or three times a week, and if I wasn't too busy, I'd watch 'em, the Betsy B steamin' along, and the little un cavortin' around 'er, cuttin' across 'er bows or a-chasin' 'er. One day, the Susan B was chargin' around my little cove, by itself, the Betsy B quiet at the dock. I think she was watchin' with another gourd thing she'd sprouted in the crow's nest. Anyhow, the Susan B hit that sandbar pretty hard, and stuck there, whistlin' like all get out. The Betsy B cast off and went over there. And, boy, did she whang that little un on the koko!

"I'm gettin' near to the end—now, and it all come about 'count of this Susan B. She was awful wild, and no use that I could see as a lifeboat, 'cause she'd roll like hell the minute any human'd try to get in 'er —it'd throw 'em right out into the water! I was gettin' more fed up every day, what with havin' to buy more oil all the time, and not gettin' much use outa my boats.

"One day, I was takin' out a picnic party in my other motorboat, and I put in to my cove to pick up some bait. Just as I was goin' in, that durned Susan B began friskin' around in the cove, and comes chargin' over and collides with me, hard. It threw my passengers all down, and the women got their dresses wet and all dirty. I was good and mad. I grabbed the Susan B with a boat hook and hauled her alongside, then went to work on her binnacle with a steerin' oar. You never heard such a commotion. I said a while ago she sounded like a peanut whistle—well, this time it was more like a calliope. And to make it worse, the Betsy B, over at the dock sounds off with her whistle—a big chimed one, them days. And when I see 'er shove off and start over to us, I knew friendship had ceased!

"That night she ups and leaves me. I was a-sleepin' when the phone rings, 'bout two A.M. It was the night watchman over't the oil company's dock. Said my Betsy B was alongside and had hoses into their tanks, but nobody was on board, and how much should he give 'er. I yelled at him to give 'er nuthin' —told him to take an ax and cut 'er durned hoses. I jumped outa my bunk and tore down to the dock. Soon as I could get the danged motor started I was on my way over there. But it didn't do no good. Halfway between here and there, I meets 'er, comin' out, makin' knots. She had 'er runnin' lights on, legal and proper, and sweeps right by me—haughty as you please—headin' straight out, Yarmouth way. If she saw me, she didn't give no sign.

"Next day I got a bill for eight hundred tons of oil—she musta filled up every one of 'er compartments—and it mighty near broke me to pay it. I was so relieved to find 'er gone, I didn't even report it. That little launch was what did it—I figured if they was one, they was bound to be more. I never did know where she got the idea; nothin' that floats around here's big enough to carry lifeboats."

"Did Dr. Dilbiss ever look at her," I asked, "after she started to grow?"

"That Doc was so hoppin' mad over the Simpkins brat spillin' his 'Oil of Life' as he called it, that he packed up and went away right after. Some o' the summer people do say he went to Europe—made a crack about some dictator where he was, and got put in jail over there. I don't know about that, but he's never been back."

"And you've never seen or heard of the Betsy B since?" I queried, purposely making it a leading question.

"Seen 'er, no, but heard of 'er plenty. First time was about three months after she left. That was when the Norwegian freighter claimed he passed a big ship and a smaller one with a whale between 'em. Said the whale was half cut up, and held by a lot of cables. They come up close, but the ships didn't answer hails, or put up their numbers. I think that was my Betsy B, and the Susan B, growed up halfway. That Betsy B could make anything she wanted outa sea water, 'cept oil. But she was smart enough, I bet, to make whale oil, if she was hungry enough.

"The next thing I heard was the time the Ruritania met 'er. No question about that—they read 'er name. The Ruritania was a- goin' along, in the mid-watch it was, and the helmsman kept sayin' it was takin' a lot of starboard helm to hold 'er up. 'Bout that time, somebody down on deck calls up there's a ship alongside, hangin' to the starboard quarter. They kept hollerin' down to the ship, wantin' to know what ship, and all that, and gettin' no answer. You oughta read about that. Then she shoved off in the dark and ran away. The Ruritania threw a spot on 'er stern and wrote down the name.

"That mightn't prove it—anybody can paint a name—but after she'd gone, they checked up and found four holes in the side, and more'n a thousand tons of bunker oil gone. That Betsy B had doped out these other ships must have oil, and bein' a ship herself, she knew right where they stored it. She just snuck up alongside in the middle of the night, and worked 'er vines in to where the oil was.

"Things like that kept happenin', and the papers began talkin' about the Wild Ships. They sighted dozens of 'em, later, all named 'Something W —Lucy B, Anna B, Trixie B, oh, any number—which in itself is another mystery. Where would a poor dumb steam launch learn all them names?"

"You said she was ex-navy," I reminded him.

"That may be it," he admitted. "Well, that's what started the newspapers to callin' lern the B-Boats. 'Course, I can't deny that when they ganged up in the Gulf Stream and started in robbin' tankers of their whole cargo, and in broad daylight, too, it was goin' too far. They was all too fast to catch. Commodore What's-his-name just had to sink 'er, I reckon. The papers was ridin' him hard. But I can tell you that there wasn't any real meanness in my Betsy B—spoiled maybe—but not mean. That stuff they printed 'bout the octopuses on the bridges, with long danglin' tentacles wasn't nothin' but that gourd brain and vines growed up."

He sighed a deep, reminiscent sigh, and made a gesture indicating he had told all there was to tell.

"You are confident, then," I asked, "that the so-called B-Boats were the children of your Betsy B?"

"Must be," he answered, looking down ruefully at his patched overalls and shabby shoes. "'Course, all I know is what I read in the papers, 'bout raidin' them tankers. But that'd be just like their mammy. She sure was a hog for oil!"