RGL e-Book Cover©

(Based on a vintage magazine cover)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

(Based on a vintage magazine cover)

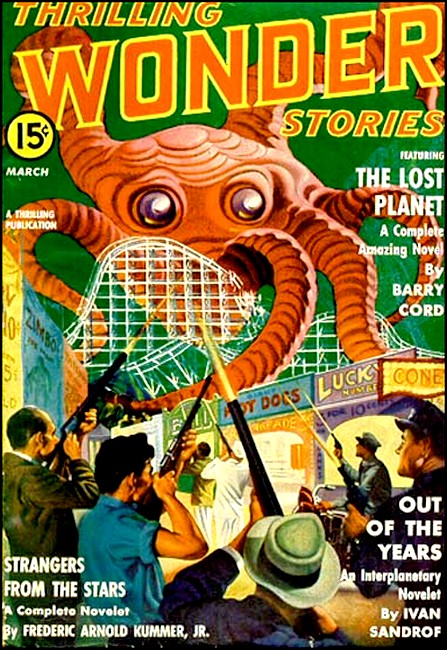

Thrilling Wonder Stories, March 1941, with "Dead End"

"COME across with fifty grand, kid, or it's going to be just too bad." Dippy Moran held out the heavily stamped check. Outstanding among the cancelled endorsements were the fatal initials "N.S.F."

"Nuts," said Hugo Trellick, staring at it, "I thought..."

"Never mind what you thought. It's the coin we want—or else!"

"Or else what?"

"You know Joe. He don't stand for no welching. The last guy that tried it on him went for a ride. He got back, all right, but he won't ever look the same."

"I'll get the money," muttered Trellick, reaching for the check.

"Oh, no you don't," snorted Dippy. "I'm hanging on to this. What's more, I'm sticking with you until you pay off. Get it?"

Trellick sighed. There was an end to all good things, and this was one of them. The three one thousand dollar notes in his wallet and the rakish foreign built roadster outside the door were all that was left of the five million his father had left him a few years before. That fifty thousand dollar rubber check stood for his last effort to come back—it stood for part of his losses at Joe Hickleman's stud joint the night before. And the Hickleman gang had a hard reputation as bad debt collectors.

Dippy Moran's threatening gaze had never left his face.

"Come on, then," said Trellick wearily.

"Where to?"

"I just remembered. My dad, before he croaked, staked a nut inventor. I've got a half interest in it—a time travel gadget. The old man thought there would be money in it."

"Yeah? Well, let's go see."

TRELLICK brought the car to a stop on the soft shoulder of

the road in front of the secluded farm house.

"Wait here. This bozo's funny about visitors. I'll do better by myself."

He slid out of the driver's seat and pushed the gate in the hedge open. After the third battery of knocks the front door was grudgingly unlocked, and Dr. Otis peered out into the dark to see who his unwanted visitor was. He was a head taller than the dapper young spendthrift who stood on his threshold.

"Oh, it's you," he said, after a moment's scrutiny. Then, as if to shut the door, "I have nothing for you yet. The book on the Constitutional convention is not selling very well and I haven't finished my studies of Lincoln—"

"It's not chicken feed I want to talk about," said Trellick roughly, pushing in. "Real dough is what I'm after, and I want it now! I'm broke, and I gotta have a hundred grand before the week is out."

"Research, my young friend, does not produce results so fast."

Dr. Otis closed and relocked the door and led the way to his laboratory. He did not like the son and heir of the man who had backed him, but he felt that at least he had to be civil to him. "Moreover, the machine is not perfected yet. It works very badly at long ranges. Two centuries is positively the upper limit at the present."

"At that," growled Trellick, "you don't have to keep on mooning around with the junk you've been wasting time with. It took you six months to find out you couldn't hear what Isabella said to Columbus and another six to learn you couldn't look in on Shakespeare writing his plays to find out whether he really wrote 'em or not. As if anybody but a lot of old mossbacks gave a hoot! What about Sir Francis Drake and the pirate Morgan I wrote you about? Those guys swiped important money and buried it somewhere. What's wrong with looking that up?"

"Too far back, the images are fuzzy," said Dr. Otis quietly. "And it doesn't interest me," he added, with dignity.

"Oh, it doesn't interest you!" sneered Trellick, wheeling on him. "Well, it interests me, and like it or not, that's where we're going. How do you get into this thing?"

He referred to the cabinet that sat against the wall, hooked to a wall outlet by a simple electric cord. It had a pair of lenses, similar to those on a penny-in-the-slot peep show, for the eyes. Dangling beside them was a set of head-phones. Beneath, the front of the machine was studded with varicolored knobs and verniers. Dr. Otis shook his head.

"I have told you repeatedly that this is no time travel machine. Such a thing is a logical impossibility, treated seriously only by half-cracked writers of fantasy. Such a machine would lead one at once into a hopeless paradox—"

"Never mind that bunk!" Trellick interrupted rudely. "What is it then? How does it work?"

"A Chronoscope, I call it," said Dr. Otis. "It consists of a set of scanners for both sight and sound that can be focused on any spot in space and at any point in time. Such an instrument can probe time in much the same manner as a telescope probes space, but since the object of its scrutiny is unaware of it, nothing is affected, as would be the case if a living man actually went back into the past. It is argued—"

TRELLICK was impatient. "Don't argue, get busy! Trot out that

Drake and Morgan stuff I sent you."

"I don't like your tone, young man. The contract I signed with your father makes me the sole judge of what sections of the past should be studied. I've already told you—"

Bam!(#suggest italics)

Without warning Trellick swung on the bigger man, smashing a heavy right to the jaw. He followed instantly with a quick left jab, then jumped back.

"That for your contract," he said in a low, deadly voice. "Will you talk reason now, or do you want more of the same?"

But Dr. Otis, for all his being a scientist, was not so tractable as Trellick had hoped. Instead, he charged like a bull, his college-trained fists plunging like pistons. Trellick exchanged another pair of blows with him, then went over backward as he crashed into a chair. Otis squared away, panting with indignation, and waited for him to get up.

But Trellick could not forget that sitting out in the road was Dippy Moran, waiting not too patiently for his fifty thousand dollars. He struggled to his feet and warily approached Dr. Otis again. Again they tangled, and with a jarred skull and a fast closing right eye, Trellick was smashed to the floor again. When he was up that time he was even more cautious, for he knew that Otis was more than his match.

Casting about for a weapon, his eye caught the heavy ebony bookends on Dr. Otis's desk. He snatched one of them up and hurled it straight for the older man's head. It struck, corner first, squarely on the left temple. There was a dull moan, and the scientist crumpled. He lay where he fell, without a further sound or quiver of motion. Trellick slowly lowered the arm that was about to cast the other one of the bookends. His jaw dropped as an awesome fear crept over him. Then, hesitantly, he knelt and passed hasty hands over the crumpled body on the floor.

Dr. Otis was dead!

Appalled, Trellick shrank back. He had been a ne'er-do-well and a wastrel, but beyond petty vices he had not resorted to crime. And this was murder! They could hang you for that! Tremblingly, he rose to his feet, recalled that Dippy Moran, the inexorable collector of gambling losses, was waiting grimly for him outside.

Hastily Trellick hefted the Chronoscope. It was lighter than he thought, hardly forty pounds. It was self-contained. He jerked the wire from the base-plug and shortened it into a coil. He snatched up a set of papers from the doctor's desk and stuffed them into his pocket. Then he managed to get the Chronoscope onto his shoulders, and staggered with it to the door.

"Phew!" he gasped, as he set the instrument down onto the soft ground beside the car. "It's heavy, but here it is. Now let's get outa here!"

"I'll say you'd better, pal. I seen what you did through the window."

TRELLICK froze.

"You going to turn me in?"

"Don't be silly," said Dippy nonchalantly. "There ain't no reward been offered yet. When there is, it'll be up to you. The Boss'll find a hide-out for you—if you can pay the rent." Dippy put a world of meaning into the way he squeezed that last word out from between his teeth. Blackmail, that indicated.

"It was self-defense," objected Trellick, doggedly. "Anyhow, nobody knows I was there tonight outside of you."

"No?" Dippy's laugh was hollow mockery. "Not counting the million prints you probably left, how about these tire tracks? You gotta tread on this buggy that's different from anything I ever seen, and it's lying there in front of the house as plain as day. They'll have your number, kid, within an hour after the cops hit the place. All I gotta say is that this here radio gadget you swiped better be worth what you say it is, 'cause the Boss don't stick his neck out for charity!"

Trellick groaned. He was in for it now. This gang would suck him dry, no matter what vast treasures of the past he uncovered. Yet there was no choice. The other road led to the Death House and the noose. He shuddered.

"Let me drive," said Dippy, scornfully, as the fleeting car reacted to Trellick's jittery nerves.

JOE HICKLEMAN proved skeptical.

"A fat help, that!" he sneered, looking down on Trellick who was sweating with the Chronoscope. The Boss turned disgustedly to his henchmen.

"Get Tony up here and have this cockeyed television gadget busted up—he ought to be able to get something for the parts. Then take this guy down to Bug's place, give him a good shellacking, and lock him up until the circulars are out. We may get something out of him yet, if it's only a deal with the D.A."

"No!" screamed Trellick, cringing at the thought of what was coming to him. "Give me time, that's all."

"You said you'd find Captain Kidd's treasure, but all I can see is fog and static."

"It's too far back—1698 or thereabouts. The Earth was billions of miles from here then, and there are too many cosmic rays between."

"Whadda I care what the alibi is?" demanded the Boss. "You promised dough, and you ain't produced in a week. Come on Patsy, grab him—"

"Wait!" wailed Trellick, grabbing at straws in desperation. "I'll prove to you the machine is a real time searcher. Is there anything that happened lately that you'd like to get the lowdown on?"

"Yeah," said Joe, after a moment's thought. "I'd like to know what rat tipped the cops off about that Rawlinson job. We knew who one of 'em was, and bumped him off, but I can't figure who else."

Trellick tuned in the coordinates of Police Headquarters on the night of March 18th. He shifted the height control, and the laterals, as he searched room by room. Presently he came to a room with five cops in it and a sweating man seated under a bright light.

"Does this guy mean anything to you?" asked Trellick, stepping back and motioning Joe Hickleman to step to the eye-pieces.

"I'll say he does," growled the Boss, grabbing for the headphones. "It's Slippery Ellis—shhhh!"

For three hours Hickleman sat, listening intently, hearing question and answer, word for word. But it only took him the first ten minutes to make up his mind.

He turned abruptly from the machine and beckoned Patsy.

"Get Slippery—he's the one. Give him Number Six, the old brickyard technique. Scram!" Then he turned calmly back to the drama being enacted in Headquarters.

"Yeah," he said complacently, as the scene terminated. "You got something there. I can see a lotta ways to use a machine like that. But I ain't forgetting you owe me fifty grand, and besides that I'm compounding a felony. So go back to your gold-digging. You got a month. Then—"

The Boss raised his brows and bulged his eyes ominously. It was his final ultimatum.

"Yessir," stammered Trellick, and heaved the first breath that could be called easy since he had become these gangsters' prisoner. Hickleman and his cohorts left the room.

After they had gone, Trellick tuned the Chronoscope to the farmhouse where the Chronoscope had been built, and watched the image of Dr. Otis as he had worked at its assembly. He could read over his shoulder as he hooked up one dial after the other, and in that way learned the purpose of several he had not been using.

THERE were sets for latitude and longitude and height above

sea-level, with verniers for delicate adjustment. There were

dials for year, month, day and hour, together with correction

tables for Julian and other calendars. Not controlled by dials,

but automatic, were five nests of cams that shot the invisible

scanners back over the serpentine path followed by the Earth and

Solar System as they hurtled through space at the rate of tens of

millions of miles per year. And there were focusing screws on the

eyepieces, and volume control on the phones.

Trellick discovered another item among the papers he had snatched from Dr. Otis' desk. In the scientist's bold handwriting were these words: "The filament in the main tube is triborium carbide, and so far as I know constitutes the total amount of this substance so far isolated. I estimate its service life at about twelve hundred hours. Economy in the use of the Chronoscope is therefore indicated."

Trellick shot a hasty glance at the meter on the machine. It read six hundred fifty four! The machine was already more than half used up! And of that amount, he himself had used up most of it in his vain searching for Captain Kidd and his buried treasure. Henceforth he must work at closer range and with as accurate preliminary data as he could secure.

When Dippy brought him his supper, Trellick gave him a list of the books he wanted bought. He could not bother with the hordes gone down on ships, the time and cost of salvage was too great, even if the position of the sunken hulk was exactly known. What he was after was shallowly buried treasure of gold or gems, preferably in some secluded spot. The books he ordered were the lives and careers of the buccaneers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Surely all those rich caches had not been uncovered!

It was Lafitte he chose. He started in the year 1818, and sought that famous privateer's marauding craft, the Jupiter. He wasted twenty precious hours of the filament's life before he found her, lazing along under full sail on an almost glassy sea. He gasped as he brought her more clearly into focus, for even at that range of a century and a quarter, she came in with startling clarity. It was as if he was perched in her mizzen rigging, looking down upon the quarterdeck of an actual ship.

A swaggering tough strode the poop, a long glass under his arm. Alternately his eyes roved aloft to check the set of the canvas or swept the empty, cloud-studded horizon. A hawk-nosed cutthroat clung to the wheel, while other picturesquely-garbed scoundrels lolled about the decks. All wore dirty sashes that once were gay in color, from which peeped the butts of pistols or the shiny brass hilts of cutlasses.

Trellick clung to the eye-pieces, watching, but the minutes wore on and nothing happened except the occasional flapping of a sail. Impatiently he jumped the setting of the Chronoscope an hour ahead and found himself about three miles astern of the pirate ship. He realized then that he must use still another dial to keep pace with the moving object of his scrutiny.

ALL day he sat there, continually shifting the time ahead,

for he was beginning to realize that the piracy business was not

always brisk. It might be days before the Jupiter fell in

with some luckless merchantman. Yet Trellick did not dare waste

his precious filament by continual tracking. At the same time he

could not risk too long a jump, as he might lose the

Jupiter altogether.

Twice a day one of Hickleman's men would bring him coffee and sandwiches, and at intervals he would sleep a little, but in the main he kept desperately at his job.

It was ten days (by Jupiter time) before he sighted the first victim, a three masted schooner with very dirty sails. There was a good breeze that day and the corsair lost little time in closing with its prey. Trellick's breath came in excited pants as he watched the engagement from the first discharge of the 32-pounders to the time when the burning schooner drifted astern, gutted of her cargo, and her scuppers running blood.

He saw many terrible scenes in the vigils that followed that first capture. Sometimes he, Trellick, in 1941, would be the first to see the sail lift above the horizon. Usually he was informed of it by the hoarse bellows of the buccaneer on watch. Sometimes he tuned in on the very midst of the furious fight.

He witnessed men shot down or hacked to pieces. He saw struggling, weeping women carried exultantly on board, and the ribald pleasantries with which they were greeted. He saw gigantic Negroes, chained in strings of four or six, driven aboard with whips and thrust down into the holds. Those, he knew, would be later sold in the slave markets of New Orleans or Pensacola for somewhere about a dollar a pound. On other days he would witness the cruel, hard discipline of the seafaring men—the floggings, dippings from yard-arm, even a keel-hauling.

To offset those sights, he saw what he was looking for—treasure! Only there were no great hauls except in the single case of a Spanish grandee captured along with his heavily bejewelled wife. Generally the loot was in the form of cargo or slaves. Yet nearly every vessel outward bound from Mexico carried at least one gold bar and ten or twelve silver ingots. Trellick shifted his scanners to the cabin below where he saw the treasure chests slowly filling.

Later, when Trellick saw them unload the stuff at Little Campeachy, the pirate's lair on Galveston Island, he learned that that was the place to watch, for the ships only acted as gatherers, as the worker bees do for the hive. To save filament he learned to take jumps in time of months. Always, after such a jump, he would find more gold and jewels, as the silver, slaves and merchandise were shipped farther east and sold, and the money brought back.

AT last came the day when Lafitte was warned that warships

were coming to raid him. That was when the most precious part of

the hoard was loaded into brass-bound chests and sturdy casks and

prepared for burial. Trellick finally had the satisfaction of

seeing four chests of gold, one small casket of gems, and two

casks of silver taken on board the Jupiter, and with them

went Lafitte himself. That voyage Trellick followed

closely, never letting the ship out of sight. In a few hours more

he would know—know where those millions in gold and rubies

and pearls were hidden, never since recovered. For it is well

known that Lafitte died poor and none of his suspected wealth has

ever come to light.

"How you doin', kid?" Joe Hickleman's gruff voice demanded. The words were friendly, but the tone was not. It sounded ominously like a threat. "Today's the last day. If you don't come through—"

"Everything's swell!" exclaimed Trellick excitedly. "Look!"

He glanced at his notes and found the day and hour when Lafitte had packed his treasure chests before taking them out to the Jupiter. Hastily he cut back the machine to show that happening. He called the Boss to the eyepiece.

"Cripes!" muttered Hickleman, as he sized up the stacked ingots and the pile of bracelets, rings and unmounted jewels. "Them sparklers is worth a cool million, even to a fence."

"I told you so," cried Trellick, triumphantly. "It was all just a matter of time—"

"Yeah," agreed the Boss, "and you just got in under the wire. If you hadn't located the stuff, I was going to sell you out. A thousand bucks the police are offering for you, but that ain't nothin'. A jerkwater college called Bairdsley Hall is offering a hundred grand for this machine in working condition. Say they bought out Otis before you croaked him, and it's worth that much to 'em to get it back, along with his notes. Whadda you think of that?"

IT was hard for Trellick to think anything, for the cold

shudders were chasing each other up and down his spine. After

all, he had not actually found the place of burial of the

treasure yet, and there was scarcely more than a hundred hours

left in the life of the filament. If in the end he failed, he

knew his gangster captor would not hesitate to betray him for

whatever he could get.

"D-don't worry, Boss," Trellick managed. "In another hour I'll have the dope. Of course, after that, I'll have to go and dig the stuff up—"

"I'll take care of that angle," said Joe Hickleman grimly. "I'm sitting in on this show from now on."

The rest of the afternoon the two men alternated at the eyepieces. What they saw could have come out of any melodrama about the freebooters of the sea.

Lafitte himself, accompanied by two husky slaves, carried the chests ashore. Four picked desperadoes rowed the boat, but waited at the shore while the pirate and his black porters disappeared into the sand dunes of Mustang Island. The two watchers of the twentieth century trailed them to a lone live oak that stood on a knoll, and saw Lafitte step off twenty paces to the southwest. Next, the slaves dug a deep hole and eased the heavy boxes into it, and returning to their spades, started refilling the hole. At that point the pistols of the pirate spoke, and the two unlucky wretches tumbled into the excavation on top of the treasure trove.

Silently Lafitte finished the burial, and afterward chopped a peculiar blaze on the offside of the lone oak. Then, his work finished, he stalked back through the dunes to where his boat awaited him. Of all living men, only Lafitte knew the exact spot where the chests lay.

"Let's go!" shouted Joe Hickleman. "What are we waiting for?"

HICKLEMAN took two of his henchmen and Trellick with him on

the trip to Texas. They hired a summer shack near Port Aransas

and told people they were vacationers from the North, come down

for a shot at tarpon fishing.

"There just ain't no oak tree!" exclaimed the Boss in deep disgust after they had combed the dunes for four days. "And the place don't look the same. Sure you know where you are? Because I ain't going to stand for any funny business much longer—"

But just then Trellick gave a little yelp. His foot had caught on a gnarled root protruding from the shifting sands. As he turned to clamber up, he saw the grain of the grey, weathered wood. It was unmistakably oak. At once he began to dig, feverishly, with both hands.

By dark they had uncovered the huge, fallen bole. Faint but still legible, despite the fact the bark was long since gone, they found traces of Lafitte's ax marks on the lower trunk. It was the witness tree!

Dawn found all four—even the puffing Boss—hard at work with pick and shovel. By the time the sun was halfway to the zenith they had turned up a skull, long, narrow and with a prognathous jaw. It could have belonged to no other than a native African. Just above the left eye socket there was a hole—the mark of Lafitte's silencing bullet.

Dippy's pick struck wood. A moment later he had fished out of the damp sand a pair of barrel staves. At his cry, the others came up closer and for another half hour they dug frenziedly, but their only reward was more staves and the rotting planks of a broken chest. A pair of brass hinges, green with age, was all the metal they found.

"You-all lookin' for pirate treasure?" drawled a voice behind. There was amusement in the tone. "'Cause if you are, I can save you work. This place's been dug clear down to water more times than I can think of. Back when I was a kid, they was some silver bars found here, but that was years ago. Since then, they've dug up acres and acres but they never found no more."

Hickleman mopped his brow and stared at the tall, gaunt man. He wore a broad-brimmed hat, and on his loose-hanging vest a silver star reposed. The pearl-handled forty-fives that hung from his belt confirmed the man's position. He was the local deputy sheriff.

"Nope," said Hickleman, kicking the skull into full view. "Just saw this lying here and thought we'd find the rest of it."

The law officer viewed it indifferently.

"Yeah," he said, "those turn up every so often." With that he chuckled and walked away.

The Boss glowered at the unhappy Trellick.

"Better think up a better one before we get back to the city," he said, tossing away his shovel scornfully.

"There isn't but one thing to do," said Trellick, doggedly. "Go back to the machine and find out who took it, and when. Maybe it's buried somewhere else."

Trellick tried to make his words sound confident, though at the bottom of his heart he felt a gnawing fear. The filament of the master tube was almost burned out. If the Boss knew that, he might give up the search and at once claim the college's reward. Trellick's reason also told him that if the treasure had been uncovered long ago, it was probably dispersed by now, and its original finders dead. Yet, since the Chronoscope was so near the end of its usefulness, he dared not ransack history for another batch of buried pirate loot. He could only go along the trail he had broken.

"Okay," said the Boss, "but make it snappy."

BACK in his city hideout, Trellick swiftly skipped down

through the century. Lightly he touched for a moment in each

year. The giant oak still stood in 1860, and '70, and '80, and

there was no sign that the ground about it had been disturbed,

although under the influence of wind and rain it frequently

changed its surface configurations.

But a day came in the early nineties when Trellick tuned in on a scene that was different. The magnificent tree lay on its side, uprooted, and two dozen paces away there were hummocks of sand that looked more manmade than natural.

Trellick hastily cut backward, groping here and there in the months just preceding, narrowing the time until he came to the exact day of the tree's destruction. It was on a day in September, and when the machine brought the picture into sharp focus he could see that it was raining in torrents and that heavy black clouds were scurrying past, driven by a fearful Gulf hurricane.

In a moment he could make out four stumbling forms, men that were slogging through the wet sands, hunting shelter. They were rough-looking men and wore patched clothing, and none looked as if he had ever shaved. Trellick took them for tramps who had gone South to escape the northern winter. As he looked on, the men sighted the tree and ran toward it. When they reached it, they huddled in the lee of its massive bole, shivering.

Trellick skipped ahead an hour, then another. Still the men huddled as the wind rose, howling ever higher. Salt spray from mountainous waves was whipping in now, mingled with the driving rain. Then came thunderous lightning, and night. Impatiently Trellick cut ahead to dawn, the break of a day full of wild fury. The great tree was down! And under it, hopelessly crushed, was one of the tramps, while the other three clung like drowned rats to its fallen branches. Off to the left, the corner of a brass-bound chest stuck out of the glistening sand. It was an act of nature, not man's cleverness that had revealed the hiding place of Lafitte's treasure.

Impatiently Trellick jumped ahead another day, and found it calm. The three men were digging furiously. Already they had uncovered half the treasure. Then he saw them hesitate, break open a cask of silver ingots, take one of them out and rebury the rest. And with that one bar of silver in their hands, they went away!

Three days later they were back, with a string of pack-mules. That time they took out all the gold and jewels and stowed them on the sturdy animals' backs. The silver they discarded as being too heavy and of little value to men so rich as they. Trellick's heart sank as he looked at the meter on the Chronoscope. There were not many hours left. Suppose these men split later and went three ways? He could hardly hope to follow more than one. Which one?

The question soon answered itself.

THE youngest of the trio, a well built fellow with a

luxuriant red beard, sank a butcher knife into the back of one of

his mates while the latter was tightening the last of the

donkeys' girths. Then, before the third one knew what was

happening, he sprang at him. The two men tussled for several

seconds, but the red-bearded one had the advantage of surprise.

In a moment he was all alone, standing among the burros on the

blood-soaked sand.

Trellick looked on in something akin to horror. Somehow he had the feeling he knew that man. There was something familiar about the eyes—and voice. Yet he could not place him.

However, brutal and cowardly as the murders were, it simplified Trellick's problem. He not only had but one man to follow, but he had the means of making him disgorge when he caught up with him in the present day. For Trellick had learned a trick or two from his association with the Boss and Dippy. He told them his plan, and they provided him the cameras and plates.

"That's right," grinned the Boss, happily, "they ain't no statute of limitation on moider. He'll have to come across when he sees these."

Trellick said nothing, but he was vaguely disturbed. What was there about this man he was photographing that seemed so familiar? He adjusted the Chronoscope once more, increased the light to maximum, and flicked the camera shutters again, so they could take still pictures of the cold-blooded murders. Well, at least they had the goods on him, whoever he was.

Small wonder the discovery of the Lafitte hoard had never been reported!

Trellick soon found a short-cut in following the small cavalcade across the prairies of Texas. Each morning he noted its direction and, knowing that it could not make more than twenty miles during the day, five minutes scouting the next morning would find it, or the embers of the camp fire left behind. Steadily the trend was to the northwest—toward the Panhandle and ultimately Colorado.

The mesquite bordering the trail turned to sage-brush, and steadily the elevation rose. In time, Trellick found himself following the laboring donkeys up a rugged canyon of the Rockies. Then, at last, his quarry settled down and made a permanent camp. First of all, to Trellick's unbounded satisfaction, the man—he watched buried the bulk of his treasure.

"Ah," breathed Trellick, "maybe all we'll have to do is dig there."

But his hopes were soon blasted. The man he pursued had kept out a pair of the gold bars and was reducing them to powder with a horse-shoer's rasp. Later, accompanied by a single donkey, he hit the trail to the nearest settlement. Trellick saw him hitch his donkeys to a post and saunter into the nearest saloon. He heard the tale of finding a placer deposit and of washing gold, and saw the powder exchanged for credit at the store, for whiskey, and for gold coin.

LATER expeditions followed, and with somewhat mingled

feelings Trellick followed his trips to Denver and to the mint,

where the man boldly sold gold bars by the dozen—a

burroload each trip. The money obtained from those sales went

into Denver banks. As the self-styled miner grew in affluence and

reputation for wealth, he became bolder. One day he came to town

with two large diamonds which he said he had bought earlier for a

lady friend, afterward changing his mind. How much would the

jeweler give for them?

Trellick saw all these things and wondered. At that rate, the buried pirate loot in the canyon of the Rockies would soon be turned into bank balances and would cease to exist in the form that Lafitte left it. Yet, when he thought of that, he thought contentedly of the damning photographs of the cowardly murders on Mustang Island. Yes, let the fellow do the dirty work of converting the pirate's cash into modern credit. The Boss could pry it loose in one interview. Already the balances totalled more than two million!

Joe Hickleman's voice broke in harshly.

"Hey, you! What about all that dough? The G-men are snooping around and want plenty for an income tax rap. I can't fool around no longer. What's the dope?"

"Coming along fine," assured Trellick, disconcerted at the urgency in the chief mobster's voice. "I'm up to 1904 and the guy has cashed in half the treasure—it's two million in the bank, and more to come."

"Well, step on it, kid. I'm in a corner. Hop ahead and get the answer, and be damn quick about it."

"I'll do my best," said Trellick, humbly.

A SMALL gong rang somewhere within the machine. Trellick was

startled. He shut off the power and began examining all the dials

and meters on the face of it. All were normal but the time meter.

That stood just a hair off zero. The machine was about to burn

out, and he was still thirty-five years behind his goal. Who was

this man who had lifted the Lafitte millions and where did he

live today?

He snapped the current back on and picked up his quarry in the famous old Brown Palace Hotel of Denver, just going into the barber shop. He snapped the switch off with a gesture of annoyance, then snapped it on again, a half-hour ahead. The man whose career he was so interested in, and whose fortune was so closely bound up in his, was just getting out of the barber chair.

His beard had been shorn away and instead he was wearing a handle-bar mustache, curled neatly at the ends as the vogue of that day prescribed. With a yawn, the plutocrat put his collar on, and leisurely tied his flowing cravat. Then he tore open a package he had brought with him and took from it an elegant Prince Albert coat of finest broadcloth. An obsequious porter brought in another box and produced a splendid specimen of the old-fashioned beaver hat.

"Very fine gentleman, sah!" said the porter, giving the final, useless whisk of his long brush. "I'll bet the ladies think you're sompin'!"

Trellick gazed long and tremblingly at the figure on the visiscreen. He could hardly believe his eyes at first, but slowly conviction got the better of his doubts. He had seen that picture before—the top-hatted, swaggering young buck with his curled mustache and imposing frock coat. It was a picture that had always stood on the mantel in his mother's house! It was a picture of his father—taken long before he was born!

Those millions! He had already had them! He had already squandered them! They were no more! All these weary weeks of search he had been following a circular trail. He was back to the beginning. Dead end? It was worse than a dead end. It was the old roundy-cum-roundy!

The hammering on the door was more insistent. Trellick stood speechless, not knowing what to say. The Chronoscope sat before him, dark and silent. That last vision had finished the overworked master tube.

"In the name of the Law!" bawled an overbearing voice. Then the door was burst in.

"You're Trellick? This the machine? We had a tip we'd find you here."

Somebody clicked a bracelet around his wrist. In a daze he was led from the room. Somehow he felt that everything had gone wrong. Of all the pirates under the sun, why had he picked Lafitte?

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.