RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a photograph of a gargoyle

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a photograph of a gargoyle

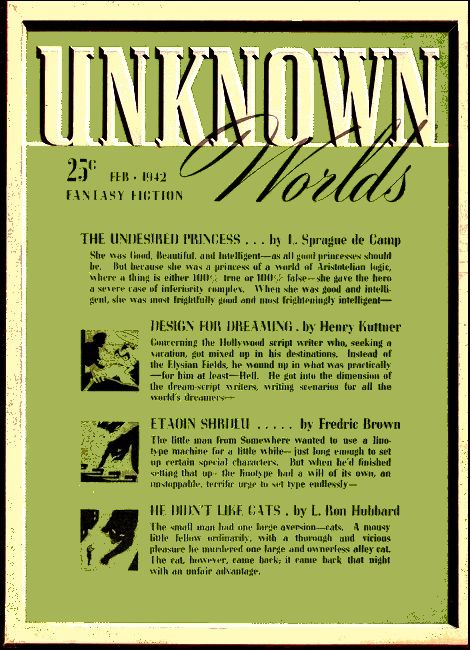

Unknown Worlds, February 1942, with "In His Own Image"

The single flashing, bloodshot eye seemed

to drill the mate through and through....

The natives had an idol of a god—a bloodthirst sort of fellow. The captain stole him—but no priests pursued. They knew their little godling—knew him better than the captain and his mate did....

FOR all their bold and swaggering walk, there was something indefinitely furtive about the two men. Perhaps it was because one of them kept looking over his shoulder, or it may have been because the other kept sidling up to him as if better to conceal the suspicious bulge under his sailor's jacket.

They stopped at Market, with Howard Street and its flophouses and hiring halls behind them, and here they waited for the traffic lights to change with that sort of mingled bewilderment and contempt that marks the seaman afoot in the heart of a great city. Traffic stopped and they struck on. In a few minutes they were climbing the low hill that leads to San Francisco's tawdry and synthetic Chinatown.

"'Tis behind Low Hing's joint," said the less stocky of the two—the crooked-nosed fellow wearing the cap of a mate. "So said that remittance man I talked with at Noumea."

"Aye," grunted the captain.

They turned into a side street and presently stopped at an alley mouth. The captain glanced about, then led the way into the rough-cobbled canyon. Its dingy brick walls were plastered with tattered posters of red covered with black Chinese characters. From above and to the left came the squeal and clatter of Chinese music, and the occasional boom of a temple gong. In the inner court they found there were doors giving access to rickety staircases.

At the top of the first dusty flight the captain kicked a China boy out of his way with a heavy curse, then turned to find the second stairs. On the third floor there was no sign of life, only a trash-littered narrow hall more appropriate to a long-abandoned house. But at one end of it there was a door, and across its flimsy panels was the crudely scrawled sign in peeling paint:

IDOLS, AMULETS AND CHARMS

BOUGHT, SOLD AND EXCHANGED

The captain did not hesitate, but thrust the door open. A high-pitched bell tinkled within, and the two men found themselves confronting an ancient counter backed by bare shelves. Farther behind, half concealed by a dirty cotton curtain, half drawn, a bald-headed, bearded old man sat on a stool. In his lap was a grotesque wooden image, and he appeared to be lost in the study of certain strange scribblings incised in its base. All about him stood other monstrous and distorted figures—of wood, of bronze, of stone. They were of all sizes and shapes. There were multiple-armed and many-eyed ones, with faces that scowled or grinned abominably. Some were animal-headed, but all were loathsome and abounded in obscene detail.

If the proprietor of the queer shop heard the bell or the heavy-footed entry of the two seafaring men, he gave no sign of it. He continued to pore over the inscriptions on the lewd figure he was holding.

"Well?" snarled the captain, drawing forth his paper-wrapped bundle and setting it down on the counter with a bang. The old man took a full minute before he turned his head and shot a cold and indifferent glance toward his callers. Then he laid aside the idol he had been studying and came slowly to the counter. He fixed a pair of glittering eyes on the hard, scarred face of the captain, then waited.

"You make gods?" inquired the seaman, and mentioned as reference the name of a malodorous character known from Paumoto to the Gulf of Huon. The leathery skin of the captain was almost black from a lifetime's exposure to the tropic sun.

The ancient shopkeeper threw back his head and laughed, cynically and with pointed scorn. The master of the auxiliary schooner Lapuu scowled.

"Men make their own gods," cackled the old man after a pause. "It is faith that does it." He resumed his probing of the hard, salt-bitten faces before him. Then he let his eyes drop and touch for a moment the package on the counter. "But," he added, "sometimes, if the pay is right—and I choose—I cut a statue."

THE captain of the Lapuu tore the wrappings from the

parcel he had brought. What he revealed was unspeakably hideous,

the creation of some drug-maddened savage—a stone

monstrosity with a double head that bore but a single eye. Its

many pairs of arms gestured variously, beseechingly,

threateningly, and otherwise in ways that had best not be told.

There was a vital cruelty about the thing that was shocking.

"We want one like that, only bigger and better," said the captain.

The dealer in idols studied the frightful creation and noted the shape and depth of the offering bowl that the fiendish figure held in its all but nethermost pair of hands.

"This is a very evil thing," muttered the old man, picking up the small statue and turning it over and over in his hands. His manner of handling the vile object was familiar yet cautious, as those wise in the ways of serpents handle venomous snakes. "It has been stolen, too."

"Aye, no doubt," said the captain hastily, "but not by me."

As he spoke, the memory leaped into his brain of the little sloop falling away astern of the Lapuu, and of the white man in it, lying face up to the staring sun of the South Sea, and of the fresh red gash under his chin and cheeks, and more of the same red splashing on the grating beneath him, A stranger, that man had been. He had come alongside pleading huskily for water and holding out a handful of pearls as the price he was willing to pay for it. And the captain remembered also the quarrel he had with his mate—the former one, not this dumb pick-up at his side—over the division of the spoils. The mate claimed that having done the dirty work, he was entitled to a full share of the profit. That mate had died that same night in a way not accurately stated in the log.

"I came by it by inheritance, so to speak," explained the captain, without the alteration of a single line of his granite face, and all the time gazing hard with his steely eyes into the piercing stare of the other. "But I know, from my knowledge of such things, where it came from, and I mean to return it. Those who once owned it are many and unforgiving. They will demand tenfold if I am to have their friendship. That is why I must take back a really first-class god—one with a brilliant eye, not a bit of glass, and with silver and jade ornaments, and of ebony, not cheap red stone like this."

"I tell you, I make no gods," snarled the surly old man. "People do that for themselves." He pushed the small idol away from him, but his eyes continued to bore into the ruthless face across the counter from him. The captain smiled faintly. Then he pulled a chamois bag from a pocket and loosened the string at its throat.

"Let that be as it may be," he said softly. "Let us call it a statue, then, but it must be four feet high and of such materials as I have mentioned."

"You have asked it," stated the old idol maker, dropping his eyes as if satisfied with his scrutiny. He shot one swift glance at the crooked-nosed mate, then held out his hand toward the captain, palm up.

The captain silently began counting out pearls into the outstretched hand of the dealer in outlandish gods. A score the old man took, of the finest, before he closed his fingers and signified it was sufficient.

"My work," muttered the craftsman, "will be done one week from Friday. The rest you must do yourselves."

"Bah!" snorted the captain, and turned on his heel, beckoning the mate to follow. They thundered down the stairs and out into the filthy court.

Above them, in the workshop of the idol vender, the old craftsman was pottering among his tools and chuckling as he poked about. There was a gleam of strange satisfaction in those eyes that could see more than was meant for them. He selected a choice chunk of ebony and laid it to one side.

"Ah, a masterful man, that captain! Gods or statues, it is all one to him." He picked up a mallet and a small chisel and went to work. "But the gods, in their own way," he mused, "are just."

THE Lapuu, as befitted her business, was small. The

cargo she sought was compact and of great value, and often lay

behind thunderous reefs of wave-swept shoals. There were but four

in her crew, Kanakas all, and each voyage saw new faces. There

were whispers in the islands concerning the high mortality on the

tiny trader, but in certain waters men do not speak too openly

about things. It is unwise to make charges without proof, and

things are hard to prove without witnesses. Though many

Kanakas—and mates—had shipped, first and last, on the

little Lapuu, no man knew of his own knowledge of a single

one who had been paid off. In none of the archipelagos could a

man be found who had sailed in the Lapuu.

When San Francisco lay twenty-eight days astern, the captain had a certain crate brought from the hold. The installation of the newest embodiment of the Great Spirit of Tana Lipa on a sort of throne in the cabin shared by the two whites was the captain's own idea. Whether the cowing of the crew was part of the idea is something that only the captain could have told. At any rate, as the packing and dunnage fell away, the Kanakas fled howling to the fo'c's'le and huddled there, whimpering, despite the angry orders and kicks showered on them by the mate. One set up a singsong monologue of propitiation.

"You'll have to finish the job yourself, mister," remarked the captain dryly from the low poop. "They're scared of the brute."

If the idol's prototype had seemed malevolent, its enlargement exuded fiendishness unspeakable. If those who hold that art is the statement of the quintessence of things are right, then the maker of that ugly figure must be reckoned as among the great masters. For unmistakable greed, lust, and sadism fairly glowed in the sensual lines and masses of the ebony torso and in the postures of the multipaired arms and legs. Some of the hands held weapons, some were clinched as if in anger, others beckoned, while some struck out with clawed talons. Yet the trunk and its unholy appendages were but accessories to the whole, topped as it was by that bifurcated head bearing its single ominous, commanding eye. Smoldering, implacable hatred and insatiable desire, if human terms may be employed in the description of an expression so inhuman, was what that leering, glassy eye conveyed. Even the mate shuddered as he beheld it when he drew back from having driven home the last screw that secured it to its new pedestal. He carefully shut the door before ascending to the poop.

The mate soon had reason enough to hate that repulsive idol even as it appeared to hate him. Fat Tom, the cabin boy and cook, steadfastly refused to enter the cabin after he had looked once upon the monstrous figure and fled, gibbering, out into the waist. Neither curses nor flogging nor threats of punishment more dire could induce him to set foot again inside. The upshot of it was the mate had to make the bunks and serve the meals himself. And as if that were not enough, the hitherto even tenor of their leisurely voyage began to be interrupted. Little things happened, none of them of great moment, but each adding to his growing irritation.

The steady, even breeze that had wafted them along so smoothly died. In its place came days of dead calm, punctuated by sudden squalls that seemed to come from nowhere and go as quick whence they had come. The crew worked sullenly and apathetically, as if they already knew the ship was foredoomed and that nothing that anyone did could be of use. Blocks jammed unaccountably, and running gear, even the newest and best stuff, parted without cause or warning. The compass card wandered at random in the binnacle until the captain himself cursed it heartily and thereafter had to depend upon the stars when he could see them.

But it was the mate who, as these accidents persisted, more and more often cast worried, surreptitious glances at the horrid creation squatting on its fantastic pedestal against the bulkhead. One night as he and the captain ate in dogged silence, the mate felt he could endure it no more. In a half-strangled voice he blurted out, "That thing gives me the creeps! It wants something!" and the captain laughed harshly and cursed him for being a superstitious fool. The mate, thus reproved and secretly ashamed of his momentary fear, kept his mouth shut thereafter. Like his captain, it had been his boast that he feared neither devil nor man. But though he could control his tongue, he could not altogether quell the uneasiness within him. It was all very well, he would say to himself, that these accidents are coincidences, but—

"Pah!" sneered the captain, as if aware of his thoughts. "A thing, a doll—no more—made by a doddering numskull in a dive in 'Frisco! 'Tis a toy with which to swindle stupid savages. Think of the pearls we'll get, man. Will not that pay for all your silly tooth chattering and the extra work you gripe about?"

But after that, the captain, too—when no one was looking—would stare thoughtfully at the ugly statue. A thorough scoundrel, he had never been permitted to live long in any one country. Consequently he had sojourned in many places and he had seen and scoffed at many such puppets, whatever their form. In this country they worshiped such and such a symbol, in that, another, but to his mind it all came to the same thing. Mankind, he thought—and his lip curled in scorn—were the gulls of priests.

Yet even as he sneered in the fullness of his contempt, a vague apprehension shook him. Unreasoning fools though he thought those others were, a wave of doubt suddenly rippled through him and his spine tingled just a little bit as he gazed into that single baleful eye. Could it be that after all there was something in this priest business? So many millions—

THERE came a night when the wind howled and the schooner

plunged frantically about in a raging sea. But it was not so bad

a night that the mate could not carry on alone, so he clung to

the wheel on the wind-swept poop and held the Lapuu on her

course as best he could, trusting that the scrap of a staysail

would stay on her. Below, in his bunk, the captain lay and idly

watched the play of light in the cabin as the fitful lightning

crackled outside. He was tired, for the day had been a hard one,

and he dozed from time to time, but the jerky motion of the tiny

ship and the violence of the thunder made sound sleep

impossible.

It was on his second or third awakening that he first noted the horrid glintings in the eye of the image, and his heart froze within him. With his eyes fairly starting from their sockets, he sat bolt upright in his bunk and stared. He would have sworn that he knew the trick of that cleverly designed eye—a ball of rose quartz cunningly hollowed at the back to admit the insertion of small emerald and diamond chips. But no! Now it was a thing of living fire, pulsating, opalescent fire; the eye of a fiend, fixed upon him with a malignant intentness that chilled him to the bone.

And then the cruel arms began to weave about in a devilish rhythm that set his pulses pounding. He tried to tell himself it was the shadows dancing, but as the last flash of lightning died he saw there were no shadows. The frightful creature gleamed with an unholy radiance all its own. And as he looked, the hideous idol seemed to grow until it loomed gigantic and menacing and filled half the tiny room. That, and what followed, drove the captain shrieking, clambering, clawing out into the storm.

The mate, his drawn face thrust into the whipping rain, clung to the rail above and stared wild-eyed into the storm-racked sea. In the lulls in the fanfare of thunder he had heard the whimperings in the cabin below, but it was that ultimate soul-chilling scream of his captain that bereft him of the shred of sanity left him. Now they were mocking, taunting voices in the winds; the scudding clouds were monsters—appalling, gesturing shapes barely glimpsed in the flickering light. The howling tempest was itself an evil entity, implacable and furious, bellowing harsh threats. The mate strained, listening, and did not know his hair was whitening.

Once, in a dazzling burst of electric fire, he caught sight of his captain, crawling forward on hands and knees, and heard him whining like a whipped dog. Again a lightning flash revealed him farther forward, crouching beside the little shack improvised of battens, fumbling with the door that kept their few remaining animals penned in. The mate averted his eyes and stared stonily at the wild ocean. In his own agony, it was nothing to him if the Malign One chose to make a beast of his skipper. Let him go and live with the goat and the chickens if that was the Great Spirit of Tana Lipa's will. In dealing with that black, one-eyed devil, each must make what bargain he could.

THE dawn came at last, gray and blustery, but there followed

shortly a marked abatement of the gale. To the astonishment of

the mate the captain suddenly appeared at the top of the ladder,

hard and swaggering as was his customary carriage.

"Get forward, mister, and set more sail," he ordered curtly. Then he turned, as if he had forgotten all about the Lapuu, and began gazing ahead as if lost in a rosy dream. The mate, frozen faced and unspeaking, stumbled forward to rout out the cowering crew.

Later, when his work was done, some weird fascination drew him irresistibly toward the cabin. The captain, lost in reverie, did not appear to be aware of his coming aft, or of his going down into the cabin under him.

The mate entered the chamber of horrors with fear and trembling, but the mysterious force that drew him was so compelling that he could do no other. It was some time before he could bring himself to lift his eyes to the hideous image that sat enthroned there, but when he did he began to understand why the deck of the cabin was strewn with blood-tipped feathers. With a thrill of horror, he looked upon the litter of bloody fragments that almost filled the bowl clutched by that all but nethermost pair of vile hands. He saw the torn entrails heaped there and the small heart that adorned the apex of the nauseous heap of offal, and the first full blast of terror seized him. Despairing, he raised his eyes until he met the steady, insatiable gaze of that awful glittering eye. It was then that it was his turn to cry out and prostrate himself before the lewd demon in the manner he thought would be the most pleasing to it.

"I will, O Great One, I will!" he whimpered. "Time—give me a little time. I did not know." And he fell to sobbing.

But outside, in the bracing sunshine and the mild breeze that had succeeded the gale, the shuddering mate regained some control of himself. He glanced uneasily aft to where the captain still stood, looking ahead as if in a trance. The mate hesitated. It was all so unreal—he must have dreamed—he must not—

"Who knows?" he suddenly whispered to himself as he felt the hairs on the back of his neck rise. "There is no harm in playing safe." And he went on forward, thinking of how to get the goat into the cabin without being noticed by the captain.

Hours later he climbed anew to the poop. He was calmer then—not serene, but at least at something like peace with himself and his diabolical master below. He slid noiselessly to his place by the taffrail and thoughtfully regarded the red caked under the ends of his broken fingernails, then he looked up at the back of his captain's head.

"After all, it was only a chicken's heart he gave," he muttered hoarsely, and he looked upon the master of the Lapuu with an emotion that was not far from pity.

The day wore on without incident. Though the gate to the animal pen yawned open for all to see, and no animal appeared on deck, neither of the two white men noticed it. Or if they noticed, they did not see fit to speak of it. After the first exchange of words in the morning, neither spoke to the other, nor appeared to see.

But night came, and it was the captain's turn to stand the first watch. The mate, fearing to profane the temple the cabin had now become, slept elsewhere—well forward, on deck, abreast the foremast. To his astonishment, the fresh dawn found him where he had laid his mattress the night before. The captain had not called him for the midwatch!

He sat upright and called for Fat Tom and coffee. But there was no answering cry or patter of feet. He looked forward to where the crew hung out, but there were only three men there—the deckhands. Fat Tom must be aft. The mate got up and walked toward the poop, calling again for the unseen cook.

As he approached he saw the captain standing with his feet widespread and glaring at him with his old-time arrogance.

"Get your own breakfast," snarled the captain.

"I want Fat Tom," persisted the mate. Why should this mad captain be permitted to bully him so? Hadn't he, the mate, sacrificed a goat instead of a chicken? By rights, he should be captain of the ship, if favor counted.

"Go get him, then," he said, waving an arm back toward the foamy wake. "He's back there."

On the instant the mate's appetite for food was gone. Sullenly and almost blindly he mounted to the poop and took the wheel. He watched with vicious envy as the captain blustered forward, storming and cursing the natives who scurried ahead of him, trying to elude his blows. The mate knew he had been beaten, outwitted. He had snatched one peaceful night—the first in many—and now he must go back to the other way, the way of anxiety and dread and nameless fears. He had been outbid. First chicken, then goat, now man! That was the utmost. The captain was the favorite.

For half an hour the captain raved and swore up forward, and every minute of that half-hour saw the mate's despair grow blacker. In the end it became absolute. Nothing—not anything—could be worse. Life was unbearable. The mate slipped a quick lashing on the wheel, and like a ghost vanished down the ladder.

It was indeed an angry god he looked upon. The bowl was heaped high and overflowed with dreadful things, but the idol still sat with unsated stare. It had a satisfactory offering, it was true, but only from one man. There lived others under his spell. The single flashing, bloodshot eye seemed to drill the mate through and through. He fell to the deck and groveled, mumbling and begging to be told what he should do. After a long time his moans ceased, and he rose stiffly, like an automaton.

"White it shall be," he said between his teeth.

The captain's resolute, overbearing stride could be heard outside, each step louder than the one before. He was coming aft. The mate stood just inside the door, his weapon ready in his hand. On the fo'c's'le three dark-skinned men set up a mournful chant, swelling louder and louder as they sang.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.