RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

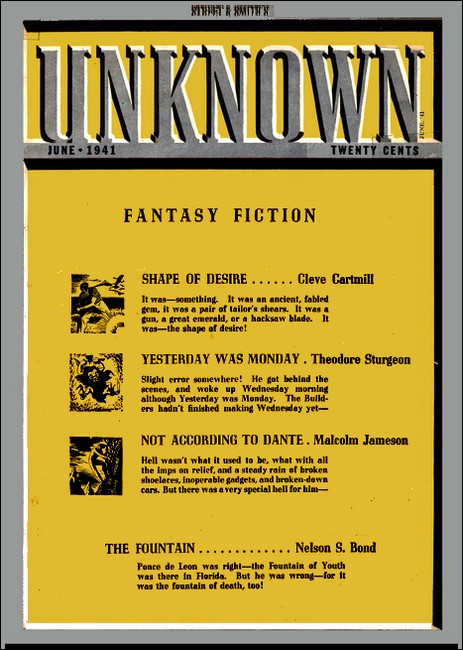

Unknown Fantasy Fiction, June 1941, with "Not According to Dante"

Hell wasn't what it used to be—but he found, waiting

for him, a very special, private hell all his own—

FOR a long time he continued to lie face down on the hard pavement in the cold, gray light of that curious land where there was neither night nor day.

He had no way of knowing how long he had slept, nor did he care. His sense of time had long since left him. How long, he could not guess. It could have been a matter of hours, it might easily have been an aeon or so. He only knew that after seemingly interminable wanderings through dark glades, and after the passage of many rivers, he had eventually come to a place where a path struck off from the broad, downward highway and led straight up the steep mountainside. He had looked dully upon the two signs, then chosen the easier road. And then, faced with yawning portal in a great, gloomy wall that barred his way, he had lain down to rest.

Before arousing himself he thought for a while on his previous journey, but it was all very vague and nebulous. In the beginning there had been another gate, and chained to it was the carcass of a dog—a three-headed dog, as he remembered it, badly emaciated. He had gone through it and walked along a river—the Acheron. He knew the name, for some historical society had evidently been along before him and marked the old historic spots with neatly embossed metal signs on iron stakes stuck into the ground. He had crossed another river lined with gaunt trees whose charred limbs still overhung the now dark river. It must have been a great sight once, that flaming Plegethon, but no longer. Cakes of hardened asphalt was all that there was left of it now.

And he remembered vaguely crossing the Styx at least fourteen times and wondering at its spiral course. He had done that by means of a modern causeway that cut straight across it, but he had not failed to note the aboriginal ferry-landing at the place he first encountered it. He wondered whether the crude skiff lying there with wide-open seams had been the ferry; a peeling sign announced the fare to be one obolus. Another sign pointed toward a low, rambling building covering many acres. It said, "Waiting-room for Shades." Somehow it suggested that the ferryman was inefficient—or temperamental, which comes to the same thing.

At another river, prompted by the sign, he had washed the blood off his forehead and face and off his bloody knuckles. Somehow he could not recall the other details that went before. That river had been named Lethe. Miles beyond—thousands, for all he knew, and a long way past the dead town of Tartarus—he had come to that steep hill and the path leading up it.

He chuckled as he remembered the signs. The one a little way up the cliff said: "To the Pearly Gates." The one by the road said: "To—" The rest was blotted out, and scrawled below were the words, "the other place." That was the work, no doubt, of a prig bound up the mountain.

PETE GALVAN stirred uneasily and began to think of getting up. The stone flags he was lying on had already made deep dents in him and he had rested long enough. The impulse to go on was strong within him. He dragged himself to a half-sitting position and began to regard the dreary landscape about him.

It, like the rest, was gray and formless. Only the wall farther down the road had shape. He dropped his gaze to the stones underneath him and cast about to see whether any of his belongings had dribbled from his pockets to the pavement. His eye caught the inscription on the stone immediately below. It said, curiously enough, "Take this, it will make you feel better." Just that, and nothing more.

He looked at the next one. It said, "I'm sure she will like it." How odd, he thought. The adjacent four or five had simply this: "Never again!" He let it go. He couldn't hope to understand everything he saw. He got up and strolled on down toward the gates.

They were big ebony gates, each leaf a hundred feet wide and three times as high. At the bottom of one a small door had been cut, and in it a sliding panel, for all the world like the door of a pre-repeal speakeasy. Above the keystone of the granite arch were cut these words:

"ABANDON ALL HOPE, YE WHO ENTER."

"Huh!" commented Pete Galvan. Then he knocked.

No one answered, so he stepped back a few paces and began tearing up the pavement. It was after about the third or fourth of the paving blocks had bounced off the black doors that the cover to the peephole slid back and a beady black eye glared out.

"Knock that off!" came a snarling, screeching voice. But on the instant its tone changed to jubilation. Galvan saw the eye disappear and at the same time heard:

"Hey, fellows, what do you think? A customer! Whee!"

There was a rattle of chains, and the small door stood open. Galvan at once pushed on in.

He was considerably startled by his reception. It was hearty, but brief.

He was hardly inside the place than hundreds of little red imps rushed him, abandoning their card and crap games. The hellions were none of them over four feet high, and all wore stubby little horns like those of a bull yearling. The tiny, ruddy devils were also equipped with venomous, barbed tails which they lashed furiously all the time. Galvan would have been completely bowled over by them, despite their small size, if it had not been that they rushed him from all sides at once.

"He's mine, I saw him first!" was what they were yelling.

But just then a superior demon of some sort made his appearance. He, unlike the imps, was quite tall and had a set of really fearsome horns. He carried a long blacksnake whip, with which, in conjunction with his tail, he promptly began lashing the howling little fiends.

"Scat!" he hissed. "Back—all of you—or I'll take you off the bench and put you back on Cave Relief." He planted a sharp, cloven hoof squarely in the stern sheets of one and drew an ear-splitting yowl. Then he jerked a nod toward Galvan. "Come into the office. Let's see what you rate."

GALVAN followed stolidly into a room let into the right-hand tower flanking the gates. The demon sat down on a handy potbellied cast-iron stove that was gleaming ruddily, and began inspecting the grime under his hideous talons. Behind a desk sat a sour-looking and very bedraggled angel.

"Name and denomination?" she asked, acidly, poising a quill pen.

"Galvan, Pete. None," he answered categorically. Then, "Say, what's going on? Where in Hell am I?"

"At the gate, dumbbell," spoke up the demon, shifting his seat slightly. The hair on his goat's thighs was beginning to smoke. It smelled abominably. "Where else in Hell did you think?"

"But I don't believe in Hell," protested Galvan.

"Oh, yeah?" said the demon, resuming his manicure.

"Silence!" snorted the angel, crossly. She was jabbing a buzzer. In a moment an imp came, capering about and making absurd faces.

"Get me file Number KF—2,008.-335," she snapped. "And ask Mortality whether they have anything on a P. Galvan, and if so, why they didn't notify me. We could have had the quarantine furnace lit off."

"Yessum," said the imp, and turned a back handspring out the door.

"NOT for us," she announced, disgustedly, after a cursory study of the asbestos-bound dossier the little hellion brought back with him. "He's not a Methodist, or a Baptist, or anything. He's not even dead! Belongs in Psychopathic. I guess."

"Nuts," remarked the demon. He spat viciously at a rat that had just nosed into the room. The rat scampered back into its hole with smoking fur, and there was a faint aroma of vitriol in the office. "Not a damned customer in months," he bemoaned.

"You are being redundant again, Meroz," she rebuked him, primly. "What other kind of customer could you get?"

"All right, all right," replied Meroz, testily. "Well, what do I do with the gink? He can't go back, and if we send him on by himself as likely as not that W.P.A. gang in mid-Gehenna would grab him and go to work on him. Then there would be Hell to pay—"

"Oh, those unemployed wraith prodders," she admitted reluctantly and with obvious annoyance, "you're right, Meroz—"

"Ha!" snorted he, ejecting two slim clouds of smoke from his shiny vermilion nostrils. "So after eighty-seven millennia of nagging, Eli Meroz is right once, huh? Think of that!"

The Deputy Recording Angel bit her lip. It was a regrettable slip.

"I mean," she hastened to say, still flustered, "that we can't afford to have any more jurisdictional disputes. After that last case the Council of Interallied Hells—"

"Yeah, I know," yawned Meroz, "but I'm asking you—what am I supposed to do? This bozo shows up here and some nitwit lets him in. Now I'm stuck."

"I know!" she cried. "You can escort him across. I'll make out a passport for him and you can get a receipt from the psychos." She reached for a sheet of blank asbestos.

"You could scratch it on a sheet of ice just as well," observed the demon with heavy sarcasm. He sighed wearily. Hell was not what it used to be.

"Galvan, Pete—U.S.A.—Earth—Solar System," she wrote. "Galorbian Galaxy—Subcluster 456—Major cluster 1,009—Universe 8,876,901— Oh, bother the rest of it. They'll know."

She wrote some more. Then she affixed the Great Seal of Hell and under the stamped name of Satan, Imperator, she scribbled her initials.

"And here's the receipt," she added. "Delivered in good condition the soul—"

"I haven't got a soul," said Galvan, sullenly.

"—the soul of one Pete Galvan, she went on serenely, "a Class D sinner."

"Class D?" demanded Galvan, angry now. "Is that the best I get? After all the booze I've drunk and—"

"Come along," said Meroz, taking a couple of turns around his gesticulating arm with his tail. "You rate the D for vanity—otherwise you'd cop no more'n a G or an H. You gotta be really tough to get up in the pictures in this place. Some day you might read 'Tomlinson'."

THE road inside was just as dreary as that outside the big black gate. On every side was the same monotonous gray landscape—broken only by the profile of ugly black dikes. Overhead was a lifeless pall, more like the roof of a vast, unlit cavern than a sky. The only hellish touch was the whiff of sulphur dioxide that Galvan scented once in a while. On the horizon, far off to the left, was a single spot of light. That was the ruddy glow on the underside of some low-hanging smoke that seemed to indicate a minor conflagration beneath.

Meroz, who had walked this far in silence, gestured toward the glow with his remarkably flexible tail.

"That," he said, moodily, "is the only job we've had this year. A train hit a bus in the Ozarks, and there were a lot of people in it—coming back from a revival meeting."

"Hillbillies," said Galvan, scornfully.

"Yeah," grinned the demon, "but they look good to us. They believe in us. It helped a lot with the unemployment situation. We're practically shut down now, you know."

"I don't get it," said Galvan, ducking and striking at something that had just pinged down and hit him in the back of the neck. He fished out a bit of brown string and threw it away. "I thought you did your stuff for all eternity. What's the line about the 'fire that is never quenched' or something like that? How about the ten billion dead sinners that did believe in you? Awk!"

Something stung him on the cheek, then fell to his lapel, where it stuck. He flicked it off, it was another string—a black one this time.

"Oh, those? They're still going strong. It's this Billy Sunday Wing that's so hard hit. It's the same old story—overexpansion. You see, during that wonderful war you put on to end war there was a great revival of the old-school hell-fire and damnation brand of religion. The Stokes trial may have helped, too, though some of us think the other way. Anyhow, we built this wing. Now look at it. Thousands of square miles of brimstone lakes and not a pound of sulphur has been burned in more than one or two percent of 'em."

"It don't add up," objected Galvan, doing a little mental arithmetic. "You made a crack back there about a lot of millennia. How do you fit that into a quarter of a century?"

"Oh, me?" the demon said. "That's easy. You see, His Majesty knew I was a very earnest tormentor and was already at the top of the imp classes. He promoted me to Demon, Second Class, and transferred me here to handle the gate detail. I jumped at it. How was I to know the place was going to be a flop?"

He paused in his stride and produced a flask from somewhere—probably a kangaroo pouch, for the fellow wore no clothes.

"Have a slug?" he offered, hospitably. "It's Nitric, CP.—a lot better than issue vitriol."

"Thanks, no," said Galvan, sniffing.

The demon took a long pull and vented a grateful hiss.

Galvan winced again as a shiny object bounced off his forehead. He stooped and picked it up. It was a gilt collar button, and had evidently been stepped on. He tossed it away, wondering where it had come from, but Meroz, bucked up by his liquor, was talking again.

"Well, to make a long story short, Old Nick had to establish Relief—"

"In 1920 or so?"

"Yes—way back there. He's very proud of it. It's his own invention, you see, and quite appropriate to the locality. It appears he'd been keeping books on us all along, and everybody knows we are not exactly saints. So first there was Cave Relief, then came the W.P.A.—"

"That sounds familiar."

"Really? Wraith Prodders Aid is the full of it. Nine tenths of our work is sticking the sinners with pitchforks, as you probably know. Nowadays the old boy keeps 'em busy—well, reasonably busy—cleaning up the grounds—"

Blam! A complete 1918 model tin-lizzy struck the road not ten yards in front of them and disintegrated into flying fragments of cast iron. It must have fallen from a great height.

"—just such stuff as that," went on the demon serenely, "only it's mostly little things—half strings with knots in 'em and such trash."

"Where," Galvan wanted to know, "does the stuff come from?"

"I'll bite." said the demon, "where does it come from? You know the habits of the living better'n I do. All we know is that it just shows up. It's mostly junk, but why do they send it here?"

Galvan enlightened him.

"I'm damned," was all Meroz could say.

MILES farther on they could hear ribald singing ahead. As they came closer they could see a string of trucks going by on a crossroad. By then the dull-red reflection on the horizon was abreast of them.

The trucks were piled high with lemon-colored sulphur, and on the top of each truck there sat a group of wild imps, waving tridents and singing lustily. Upon sighting Galvan they broke into a string of invective that would have delighted and astonished an old bos'n. But after a sharp snarl from Meroz they cut that out and returned to their singing.

"The next shift going over to No.16—that's where the Arkansas hillbillies are. That job took quite a lot of 'em off relief, what with the loaders and the brimstone haulers, and three shifts of prodders. Besides those you've got to figure two blacksmiths on the job all the time—"

"Blacksmiths?"

"Yeah. Those prongs melt down. They have to weld new ones on every hour or so. Of course, they could throw the shafts away and simply use new ones—Satan knows there are stacks enough of them around, rusting—only"—wistfully—"business might pick up."

Eventually they came to the other side. There was another wall, but not so high. In it was set a moderately small gate, with ornamental bronze doors. The demon led the way on up to it and stopped.

"End of the line." he said. "Here's where you get off."

Pete Galvan had passed through two gates of Hell already with the minimum of emotion, but as he stared at this one something flopped inside his viscera and turned clean over. It was with a definite catch of the breath that he read the inscription over the door. It was:

WELCOME, PETIE!

A bronze plate beside it carried further interesting news. The

first two lines read:

MARANTHA MIDDLEBROOK, ARCHITECT AND DONOR

ANNA MIDDLEBROOK GALVAN, ASSISTANT AND CO-DONOR

Below was this information:

MESSRS. FREUD, JUNG AND ADLER,

CONSULTANT SOUL ENGINEERS,

HAVE INSPECTED AND MAPPED THIS PLACE.

"Well, well," said Meroz, cheerfully, reading over Galvan's shoulder. "Look who I've been with all this time. A guy with a private, personal Hell, no less. Unholy Beelzebub! It must be something to work in a joint like that."

He suddenly sprouted a pair of flapping bat's wings ending five feet above his head in curving clawed finials.

"But then," he added, "this newfangled stuff is out of my line. S'long, kid, and take it easy. It's the first million years that are the hardest."

With that Meroz polished off another swig of his bonded Nitric and swirled upward and off with a heavy flapping of wings. Pete Galvan watched him go with considerable regret. Then he turned and walked slowly toward the door. Those inscriptions had worried him a lot. For Marantha Middlebrook was his maternal grandmother, and she had died before he was born. Why should she have designed a Hell for him? And yet more mysteriously, why should the other one? Anna, his mother? And then he saw that the door was ornamented with bas-relief.

THE left leaf carried a representation of a beetling, overhanging cliff with a narrow path winding along the face of it supported by jutting ledges. In the canyon below twisty things were intertwined—snakes or giant worms, they might be either. The right-hand panel was covered with diminutive figures, some running about frenziedly with hands clapped to the ears. Other agonized ones were clawing at the smooth inner sides of eggs that seemed to surround them. And as Galvan looked wonderingly at the designs, the doors opened smoothly and quietly of their own accord. On the other side was—blackness, velvety utter blackness. There was no one, either human or diabolical, in sight. The doors, apparently, had opened of their own accord.

Like a somnambulist, Pete Galvan marched straight ahead into the darkness, and did not notice that the doors folded shut behind him as he did.

It was not until he came up against a wall of cold, hard granite that he looked backward and realized that the dark was all about him. He put out a hand to one side. There was another dripping granite wall; on the other side the same thing, beaded with cold moisture. Galvan experienced a momentary fright—he had walked into a blind alley. He took three hasty steps back—he wanted to get out badly; he had suddenly remembered that Meroz was to get a receipt signed by somebody and had gone off without it. He must call him back. Then he came up against a fourth wall, squarely trapping him.

Cold sweat trickled down his taut face. Something brushed his hair and an upflung hand scraped its knuckles against more damp granite, close overhead this time. Galvan lost all control and screamed. Shrieking, he beat wildly against the hard barriers that shut him in. He felt as if he was suffocating and that his life depended upon his being let out on the instant.

For a long time he kept that up, until he fell panting and sobbing to the stony floor, weak and exhausted.

He must have slept, or fainted. For when he returned to consciousness his environment was so different he knew that the change could not have taken place without his being aware of it. A smooth surface bore down on him from above, barely touching the point of his nose, his chest and the tips of his toes. He tried to rise, but could not. He tried to raise his hands, but could not. They were at his sides, and the pressure against his knuckles told him there were also boards penning him in laterally. Then the awful truth burst upon him. It was a coffin he was in.

He was buried alive!

Again he struggled for breath—that last one, it seemed to be. Yet in his frenzy of despair he screamed without restraint until he could scream no more but lay quivering writh helpless panic. In time he lapsed into a state of dull apathy, too weak and hopeless to struggle more. And that was when he noticed the cold draft of air blowing down upon his shoulders.

He pulled himself together and tried to think the thing through. It must be that if he was in a coffin, it was one with open ends. Inch by inch he wriggled upward. And inch by inch he made progress. There was nothing to stop him, He continued, and after he had gone a long foot or so, he was aware there was a little more room around him. A few yards more and there was some gray light, enough to let him see he was in a narrow tunnel. At the end of what could have been an hour he sighted the full light of day—a circular blob of bright sunshine shining into his rabbit warren. He could roll over then and make the rest of the way on hands and knees.

Once he was outside in the blessed space and light, he drew a deep breath and rested, reproaching himself for his mad panic. If he had not let the shutting of the door upset him, he would no doubt have found the tight tunnel and escaped through it long before. In fainting he had doubtless fallen directly before it, and later, in his restless coma, he must have wriggled well into it. So, in that manner, strengthened by the glorious sunlit and unlimited space. He laughed the incident off. Now he could get about his business of exploring this Hell his forbears had so kindly bequeathed him. What had he to fear? Had he not already passed the Hells devised by twenty-five centuries of ancestors and been none the worse for it? He began to take stock of this sunlit place where he was.

He appeared to be on a broad stone platform at the base of a high cliff. He got up and walked out a little way from the cliff so he could look up at it better. But to his surprise the flat rock was not so wide as he thought, nor so flat. A few paces away it began to slope down, until it took such a sharp angle that he doubted his footing. Then to his horror he observed that it came to an end another yard below him. And beyond that was nothing—nothing but empty air. Through the violet haze of great distance he could just make out another mountain range on the other side of the incredibly deep valley that lay between the one he was on and it. He stood precariously on the brink of a precipice of unguessable height. And at that moment of horrid realization, his foot slipped!

GALVAN fell flat on his face—and clung for a while with outstretched hands to the slippery rock. This time he resolutely fought off panic, but he did not dare move until he was quite sure of the grip on himself. When that time came he crawled cautiously upward until he was once more on level stone.

It was clear that he was on the shoulder of a mountain and the ledge he was on curved both ways out of sight. Which led up and which down he could only guess and he told himself it did not matter, though, all things considered, he preferred to go down. But the nature of the ledge soon settled that problem for him. To the left, after about forty steps, he found that it narrowed to nothing. He retraced his steps and took the other trail. For a well-defined path, he noticed now, led from the mouth of the cavern he had come out of.

The ledge narrowed in that direction, too, but not unbearably. At the end of some minutes he found himself walking along the ledge that was still all of four feet wide, and he took the precaution to keep his eyes glued to the path immediately in advance of his feet. He dared not so much as glance over the edge, for the earlier glimpse of that sheer drop of many thousands of feet had frozen him to the marrow and covered him with goose pimples. Nor did he neglect to keep his left hand trailing against the cliff wall, caressing it with his fingertips as he went along. He was hideously uncomfortable, nevertheless, and it was only the occasional sight of old footprints in sandy patches that reassured him sufficiently to keep him going. If others had come this way, he could make it too, he told himself frantically.

It was when the ledge and cliff turned from stone to clay that cold fear again beset him. His first warning was when his trailing fingers struck an embedded stone and clung to it a moment while he debated exactly where he was going to place his foremost foot next. As he relinquished his hold upon the stone, it became dislodged and thundered down the face of the precipice in the vanguard of an avalanche of loose earth that tumbled down in the wake of it. Galvan gasped and flattened himself against the vertical clay bank as the torrent of dirt and gravel roared past him. When the dust had dissipated, he stared with bulging eyes at the path he had just come over. It was not there! Behind him there was only a crumbly, vertical wall down which a few belated pebbles were bounding. Faint sounds from below told him that the avalanche was still crashing earthward, despite its already long fall.

Pete Galvan's skin was white as snow and as cold as he stood there against the treacherous wall of clay. He was afraid to make a movement, yet he knew he dared not stay. For the path beneath him, disturbed by the recent dirt-fall, was sloughing away by inches and sliding into the depths.

With a heart thumping like a pounded tympanum, he forced himself to edge along. A little farther he discovered to his horror that the path was not only narrower—something less than a yard—and softer, but blocked here and there by obstacles. He could step over most of them, but eventually he came to one that was too big. It was a boulder that stood waist high, and he wondered how it got there, for the cliff above hung out over him like a sidewalk awning.

He paused and studied that boulder for a long time. He must pass it, but how? It touched the bank on the one hand, and protruded over the precipice's edge on the other. It was too high to step over, and the path beyond was too unstable to sustain a body landing from a jump. There was but one course left. He must climb up onto it, then down again.

Pete Galvan bent over and placed both hands atop the boulder, then brought up a wobbly knee. The rock trembled a little and Pete froze in his awkward position. But the rock did not roll, so he transferred a few more pounds of his weight to the pressure of his hands and the advanced knee. Again the rock trembled, but did not roll. With the courage of despair Galvan put his full weight upon it and drew up the idle leg. The boulder teetered wildly, dust rose from the canyon as the rotten soil below the boulder began shedding itself away. The boulder turned sluggishly, then like a startled hare it bounded downward, tons of dry clay tumbling after it.

Galvan leaped wildly forward as he felt the rock turn beneath him. His heels struck the path beyond, and it in turn crumpled beneath him and fell rumbling down the cliffside. He never knew how his hand managed to connect with that root, but it did. An instant later he was dangling over the chasm, clinging to a gnarled tree root that stuck out of the face of the cliff.

To his tortured mind it was all of a century that he hung there expecting every moment to have to let go and drop. Though his eyes were firmly shut, the bare thought of the bottomless abyss under him was vastly more painful than his cramped hand and the agonized arm muscles. He knew that the end was at hand, yet he clung on to the last eternal moment. And then, just as sheer horror was about to turn to black and irrevocable despair, he made that last superhuman effort. Summoning up his last ounce of reserve, he twisted and grabbed with the other hand. It, too, caught a root. He had a respite!

THAT trip up the face of the crumbling cliff was as arduous a one as man ever made, but he made it. Though he was winded and weak as a baby, he did not cease his exertions until he had placed a long distance between himself and the maddening brink. He found a spot among some trees on top of that tableland and threw himself down in the grass. He tried to sleep.

A tree nearby creaked. Yes, creaked. He thought at first it was a rocking chair with a loose rail, then it seemed that it was a door with unoiled hinges. He listened to its rhythm with growing disgust, but hardly had he adapted his ears to it than the damnable thing changed its rhythm. It not only dropped one creak from the series, but the next three were irregularly spaced. Then it took up another rhythm.

More sounds were added—the zooming buzz of some wheeling insect, now blatant, now requiring straining ears to keep up with it. Then came a pattering, as of naked feet on concrete, a noise that meant nothing to him, but annoyed him intensely; last of all, the raucous "caws" of a race of cynically derisive birds. Galvan stood it as long as he could, then rose and fled the place. A flock of carrion birds he had not noticed earlier rose as he did and sailed in ever widening circles above him, swooping now and then as if to bite at him.

Galvan ran on, until he could run no more. Then he stopped, panting. His feet were sore and cut and he wondered how he had become unshod. He had quite forgotten that he had thrown his shoes away while on the slippery ledge. But he wished now he had not, for his feet felt indescribably uncomfortable. They were not only hurt from the running, but some nasty, oozy stuff had stuck to them and was squeezing up between his toes. He looked down at them, wishing for water with which to wash them.

Despite the other horrors of this inherited Hell, he knew when he looked at those feet that he had attained the ultimate. He was standing barefooted in two inches of blended caterpillars and groveling, blind worms, and as far as the eye could reach the ground was covered with them. The vile creatures slithered and crawled, working over and under each other, and both varieties trailed a repulsive slime. But the most sickening detail was that fully half the caterpillars were covered with ulcerated knobs that grew and grew until they burst with a faint plop, throwing gouts of dirty orange liquid in every direction. And wherever those drops of infection struck, fresh ulcers grew. Galvan's own legs were speckled halfway to the knees with dirty orange droplets, and those spots itched unbearably. He watched wild-eyed as the ulcers formed.

He paused in his wild race away just once. That was in a sand spot not quite covered by the odious caterpillars. The violent rubbing with sand that he gave his rotting flesh was only an added pain. Then he knew that sand, or even water, if he had it, would not be enough. He must get somewhere where more drastic treatment—amputation, perhaps—was available, for he could not bear the thought of having those ulcers climb higher than they were already—at mid-thigh.

He charged on, trampling the squirming, hateful pests underfoot, not caring any longer where he went, so long as it was away from those diseased foul worms. He did not see the edge of the cliff until he was at it. Nothing could check the momentum of his plunge.

Down, down he went, turning slowly over and over as he fell, now glimpsing blue sky and bright sun, now the gaunt face of the unstable cliff, now the canyon bottom rushing up to smite him. He set his teeth and waited—waited for that terrible final impact that would blot out all the other horrors of this Hell.

When it did come it was a blessed relief. He struck headfirst and there was one sharp crack—hardly worse than an ordinary knockout. There was a brief explosion of light, and he slipped into cool darkness.

"HE'LL do now," Pete heard a feminine voice say, and he felt cool fingers relinquish his wrist after placing it back on the bed. He opened his eyes to see a girl in nurse's uniform and two white-smocked men standing looking at him.

"A-are you demons, too?" Galvan stammered, looking at them with one eye. The bandage over his head covered one. The question seemed to him to be a perfectly logical one. If, as the inscription on the gate suggested, this was his own private and personal Hell, doctors would do as well as anything for tormentors. He couldn't forget a certain dentist.

One of the doctors laughed. "That is a matter of opinion, sonny. But you'd better knock off going around breaking up religious services or you'll have some real demons after you. The way those Holy Sons and Daughters of the Pentecost went after you when you tried to bust up their service should have taught you that. Do you remember? You started a free-for-all and they crowned you and tossed you out on your ear."

"I don't remember nothing since I washed my face in that River Lethe," mumbled Pete Galvan, sullenly.

The first doctor looked at the second one quizzically. The other nodded.

"It's all in here," he said, tapping a roll of shorthand- covered sheets of paper. "He was delirious most of the night. The nurse on duty recorded the high spots. Most of it is commonplace enough, but what interests me in the case is that it was his own unprompted mind that designed that last gate—especially... uh... the inscription over it. It is little mysteries like that that make my job fascinating at times."

"Oh. You mean the stuff about his mother and grandmother?"

"Exactly. Of course, we already had a history of dipsomania, and in these ravings we get a glimpse of demono-mania, claustrophobia, acrophobia and mysophobia, but those, as you know, are run-of-the-mine symptoms. But he also rather clearly indicates that his grandmother was one of the old orthodox with an active New England conscience. I suspect his mother tried to do without any. He inherited the inevitable conflicts and no doubt added a few embellishments of his own—"

"Say, doc," interrupted Pete Galvan, bored with talk that had nothing to do with him that he could see, "did you know I've been to Hell and back? And what's more, it's a private, special Hell built just for me? Gee, ain't that something!"

But the doctor was looking at him disapprovingly.

"Oh, you don't believe it, huh?"

"Yes, son, I do. You were in Hell the live-long night."