RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Unknown Fantasy Fiction, March 1940, with "Philtered Power"

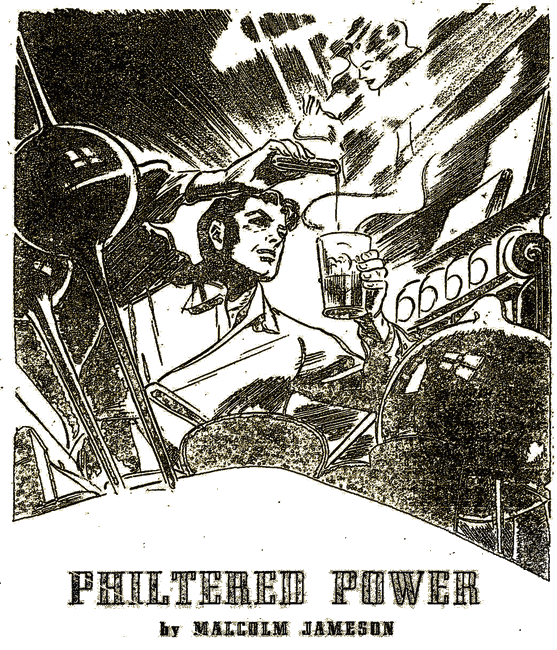

This is why, no doubt, love-philters, power- getters and magician-alchemists in general went out of style. An indubitable and scholarly—if hilarious—discussion.

IF!

If the State gold mines had not played out, the assay office would not have become the sinecure it was.

If the State had had an efficient government, the job would have been abolished decades before, instead of remaining one of the choicest plums at the disposal of the Hannigan machine. And if Doc Tannent had been any sort of chemist and had not been such a colorless, shy and helpless individual, he might have been able to hold a regular job somewhere and not be compelled to sponge on his wife's brother from time to time. And if the brother-in-law had not been a clever lawyer and therefore able to get something on Hannigan, he would never have been in the position to demand that Hannigan "do something" for the estimable but ineffectual Doc Tannent.

So it was that Doc Tannent became State assayist.

Now, that is one of the cushiest, most innocuous berths in the United States, and there should have been no reason why the good doctor should not have settled down and enjoyed himself in idleness for the remainder of his life. If only the roof had not leaked, and if it had not been that he had the dizziest, most scatterbrained assistant assayist in the whole country to help him do nothing, the startling events of that summer would never have come about. Or even granting those two accessory "ifs", if Doc had been a golf-player, no harm would have come of the appointment.

But he wasn't. He loathed, golf. And, as the bard so charmingly puts it, thereby hangs a tale.

DOC TANNENT was willing to have a soft job, but the assay office

exceeded all expectations in that direction. There was absolutely

nothing to do. There was no mail, no rocks to analyze or any

chemicals to do it with. Except for keeping office hours and

signing the pay-roll twice a month, Doc had no duties—except, of

course, the forwarding of the ten-percent "contribution" to

Hannigan as he cashed each of his pay checks.

His helper, Elmer Dufoy, ne'er-do-well nephew of a United States senator, swept the place when the spirit moved him, or on rare occasions dusted off the tops of the obsolete books on metallurgy that graced the office's library. The laboratory was kept closed and locked, and the cases of mineral specimens in the halls needed no attention. When Elmer was not skylarking with the girls in the adjutant-general's office across the road, he sometimes mixed up batches of a foul-smelling compound which his kid brother later peddled to farmers as horse liniment.

Such was the layout of the assay office, and such was the situation when Doc Tannent took over. He inspected his plant the first day, moved his belongings into his private office the next, and on the third day he became bored. For, for all his ineptness as a chemist and a human being, Doc was full of energy and liked to be doing something, if only pottering away at aimless experiments. So, being bored and having an ancient, disused laboratory at his elbow, Doc took up a hobby—a scientific hobby—and not golf, which is a much more efficient and safer method of killing time. That turned out to be a mistake; as Doc himself would be the first to admit, if it were not for the fact that today he is confined to the padded cell of Ward 8B of the State Hospital, complaining bitterly because no one will kill him as he deserves, or let him kill himself.

In the beginning he did not take the giddy Elmer into his confidence. All Elmer knew was that many strange parcels and boxes kept arriving and that Doc chose to unpack them himself and stow their contents away in the privacy of his own sanctum.

But one day a case arrived marked "Open Without Delay—Perishable," and since Doc was not in, Elmer undertook to unpack it, and looked for a place to put its contents. To his astonishment the box was filled with recently dead frogs, and while he was still staring goggle-eyed at the heap of limp amphibians, little Doc Tannent came bustling in. Around Elmer, Doc did not exhibit the bashfulness and stammering he was noted for before strangers.

"Come, come," he said sharply, "get a jar and put them on the shelf beside the scorpions."

Shaking his head and muttering, Elmer unlocked the gloomy laboratory and found a jar. An hour later he had finished helping Doc rearrange the curious contents of the private office, which Doc had rigged up for his experimentation.

Along one wall was a row of bins, and over them were shelves cluttered with jars and tins, and every container in the room bore a strange label. Such things were in Doc's hoard as camel's dung, powdered dried eyeballs of newts, tarantula fangs, dried bat's blood and tiger tendons. In the bottles were smelly concoctions marked "Theriae" this and that, and there were jugs filled with stuff like "Elixir of Ponie" and "Tincture Vervain," and there was a small beaker labeled "Pearl Solution." In addition there were tins of dried scorpions and crumbled serpent skins, and many more jars containing the organs of small animals, and each of them had a legend which described the animal and the time and circumstances of its death. One that Doc seemed to value highly read: "Gall of Black Cat. Killed in a churchyard on St. John's Eve; Moon new, Mars ascendant." It struck Elmer as a wee bit spooky, smacking of necromancy.

"Thank you," said Doc, when the queer substances had been neatly put in order. "A little later, when I have made more progress, I may ask you to help me now and then with my researches."

Elmer went away, mystified by the strange slant his new boss had taken. The last assay officer had not been that kind of scientist. He was a mathematician—had a system for doping out the chances of the ponies in today's race—and spent all his time tabulating track statistics and running the resultant data through some weird algebraic formulas. Elmer hadn't any too much respect for his various chiefs, as most of their hobbies worked out badly. He knew, for it had been his job to run down to the corner cigar store and place the former assayist's bets. He had picked up a nice piece of change a few times by placing a bet of his own—the boss' choice to lose.

"Another nut," he confided to Bettie Ellsworth, filing clerk for the adjutant-general, but Bettie was not particularly impressed. It was axiomatic that anyone accepting the assayship would be a nut. So what?

DOC and Elmer broke the ice between them the day the long box

arrived from Iceland. Elmer got the pinch-bar and nail-puller

and ripped the cover off. Inside was a slender something wrapped

in burlap and wire, and the invoice said: "One eight-foot unicorn

horn, Grade A. Guaranteed by International Alchemical Supply,

Inc." Elmer's eyes bugged at that. So! Magic and wizardry was

Doc's racket. Alchemy!

But he shucked off the burlap and stood the thing up. It was a tapering ivory rod indented by a spiral groove running around it—obviously a tusk of the narwhal. Elmer had had to pass the civil-service test, being only an assistant, and knew a thing or two about elementary science, even if his uncle was a United States senator.

"Spu-spu-spu-splendid!" stuttered Doc, delighted at its arrival. "Now I can go to work. Saw off a couple of feet of that and pulverize, it for me—and get that heavy iron mortar and pestle out of the metallurgical lab. You'll need it. And be sure you keep the unicorn flour clean—impurities might spoil the outcome."

"O.K.," said Elmer, gayly, dashing off to the lab. He remembered vaguely that miraculous things could be done by alchemy and he had hopes that Doc might teach him a few tricks.

The next day Doc put him to work making a salve out of an aggregation of dried lizards, eagle-claws, rose-petals, rabbit- fur and other such ingredients. While Elmer was stirring the mess in some gluey solvent, Doc dragged down a few of the big books he had bought recently and laid them about the room, opened with markers lying in them. Then he set a beaker of greenish fluid to boil and scuttled from one of the huge tomes to another, writing copious memoranda on a pad of paper.

"You may think that alchemy is a lot of foolishness, Elmer," said Doc, as he sprinkled a handful of chopped cockscombs into the malodorous mixture boiling in the beaker, "and so it is—a blend of superstition and pompous nonsense. But some of these prescriptions were used for centuries to treat the sick, and believe it or not, some of them were actually helpful. I grant you that with most of the patients it made no difference whatever, and a sizable number of the others died, but why did some recover?"

Elmer shook his head, not stopping his whistling as he churned and kneaded the filthy compound under his mixing pestle.

"Unknown to the alchemists of the Middle Ages, some of the ingredients they used actually had therapeutic value. Take the Chinese. They brewed a tea from dried toads' skins and gave it to sufferers from heart trouble. It helped. That is because there are some glands in the neck of a frog that secrete a hormone something like digitalis, and that is what did the trick. Maybe there is something in the superstition held by some savages that eating the vital organs of your enemy makes you fiercer and stronger. Why not? When they ate the other fellow's kidneys, they ate his adrenal glands along with them. That ought to pep up anybody.

"This work I'm doing may bring to light some hormone we haven't discovered yet. Classical chemists say, of course, that there is no point in mixing these prescriptions—that all the ingredients have been analyzed and that those that are of any use are already in our pharmacopoeia. But to my mind that is an inadequate argument. Analysis of metals tells you very little about the properties of alloys made by mixing them. So it is with these things. We have to mix them up and see what we get. That is the only way."

"Uh-huh." grunted Elmer, then sneezed violently. His annual attack of hay fever had announced its onset.

"Watch out," cautioned Doc, in some concern. "The humors, as they were called, of the body have a profound effect on these mixtures. Many, of them call for human blood, or spittle, or such things. See, I have a bottle here of my own blood that I drained out of my arm for use whenever it is called for. So don't go sneezing into that salve—you might change its properties altogether."

"Yes, sir," moaned Elmer, and dragged out his handkerchief.

ELMER DUFOY let himself into Doc's office that night with his

passkey and, after carefully shrouding the windows, turned on the

light. It was the first time in the history of the assay office

that any of its employees had worked overtime, but Elmer had a

reason. He had peeked into one of Doc's big books and seen a page

that stirred him strangely.

His courtship of Bettie Ellsworth was not going too smoothly. There was a hated rival, for one thing, and Bettie was naturally coy, for another. The page that had caught Elmer's eye was headed this way: "Love Potions and Philters. How the Spurned Suitor May Win the Coldest Damsel," and there followed similar provocative subtitles. Elmer's heart vibrated with expectancy as he hauled down the weighty volume and hastily scanned the pages.

He found what he was looking for, scribbled some notes and assembled the equipment. He robbed Doc's jars and bins of the necessary components of the stuff he was about to brew. He rigged a still, having already learned that that was the modern counterpart of the "alembic" the ancient tome called for. He found an aludel, and an athanor, and by midnight his love-potion was sizzling away merrily. Even through his hay-fever-stricken nostrils he could tell it was potent. Anything that smelled like that must have a lot of power.

At last the time came for the personal touch, and Elmer jabbed a finger with his penknife and let the blood trickle slowly into a measuring glass. He added the few drams required, set the beaker on the window sill to cool, and idly strolled up and down the room, thinking contentedly of how easy the conquest of Bettie was going to be. After a while he thrummed through some of the other books to see what formulas they might contain.

There was the "Zekerboni" of Pierre Mora, books by Friar Bacon, Basilius Valentinus, Sendigovius, Rhasis and other outlandish names. He came upon four massive volumes by one Phillippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim and found that the short for it was Paracelsus. There were books in medieval German, Latin, and what looked to him like shorthand, but what a notation on the flyleaf said was Arabic.

He might have looked farther, but his solution had cooled and the hour was late. He drew off the clear liquid as the directions- prescribed, filtered it through powdered unicorn horn and added the four drops of a certain tincture. Then he bottled it and slipped it into his pocket, well satisfied that a happy home for life was to be his lot, commencing with tomorrow.

Although he had every confidence that he had followed the directions to the letter, he was not thoroughly convinced of the efficacy of his potion until he had administered it to his victim and seen with his own eyes the consequences. That night, sleepy as he was, he took her to a show and to a soda fountain afterward. Quickly, once when she turned her head away, he dumped the potion into her ice-cream soda. He watched eagerly as the liquid in the glass slowly began to fall, drawn away through the straw clamped between the two desired ruby lips.

"I think you're cute," she remarked, irrelevantly, after the first sip.

When the glass was half empty she suddenly bounced off her stool and flung her arms about his neck, kissing him wildly. "I love you, I love you, you wonderful boy!" she exclaimed, disregarding the other customers in the place.

"Drink it all, honey," said Elmer, grabbing the check and making ready for a fast getaway. They could discuss the rest of it somewhere other than the drugstore. There were a lot of people in the place.

DOC TANNENT congratulated Elmer absent-mindedly when his helper

informed him he was about to be married. Something new had turned

up to make the assay officer preoccupied. The roof was leaking,

and badly. Eight pounds of rare herbs had been spoiled by the

water from the last rain, and two lots of salts ruined. The

superintendent of public buildings had been over and after a look

around shook his head. A new roof was needed, and that meant an

appropriation. See Hannigan, was his suggestion.

It was at that time that the convention of the Coalition Party was due to be held in Cartersburg, and Hannigan would, of course, be there, as well as the governor, the members of the legislature and all the other politicos, both big shots and small-fry. The annual convention was the whole works, as far as the government of the State was concerned. New office-holders were picked and nominated, the pulse of the people was taken, and new taxes were decided upon. The winter's legislation was planned, contracts were promised and appropriations doled out.

It was Hannigan's show, from first to last, and nobody else's. He made and broke everybody, from the governor down to the dog- catchers; he decided what the people would stand for, and inside those limits he took a cut on every dollar the State took in and had another slice out of every cent the State paid out. When you wanted to get anything, you saw Hannigan, no matter who was the nominal boss. And Hannigan, a political boss of the old school, heavy-paunched and heavy-jowled, was no man to trifle with. "What's in it for me?" was his invariable question before discussing any subject, and he would tip the derby hat more on the back of his head, take a fresh bite on his fat, black cigar, and glare at the petitioner. If the answer was satisfactory, there would be a cynical wink, a slap on the back, and the matter was as good as done.

Doc Tannent's timidity and general incapacity came back on him with full force the moment it was suggested he go see Hannigan about the roof.

"Oh, let it go," he would say whenever Elmer prodded him about it, for he dreaded the encounter with the wily politician at Cartersburg. But then it would rain again, and his office would nearly get afloat. Elmer was thinking, too, of his approaching marriage. He wanted a raise, and wanted it so badly he was willing to kick in twenty percent of the gain in order to get it.

"Hannigan won't bite you," urged Elmer, wise in the way of the State's routine. "Just talk up to him. Lay your cards on the table; you don't have to be squeamish about mentioning money. He'll rebuild the building and double our salaries if you put it up the right way. If you hit a snag, send me a telegram. In a pinch my uncle might put in a word for us."

In the end Doc went, leaving Elmer, sniffling and sneezing, to hold down the assay office in his absence. Four days later Elmer received a doleful letter from his chief, stating in rather elaborate and antiquated English that he was being subjected to what the more terse moderns would simply call the "run-around." He hadn't been able to get near Hannigan. They had shunted him from one committee to another, and nobody would promise anything.

Elmer frowned at the letter as his vision of the little love-nest he had planned began to dwindle. He was reaching for the phone to try to contact his powerful uncle in Washington when the happy thought hit him. Alchemy had got him a bride, why not the raise? He dropped everything and began a frenzied search of Doc's queer library.

WHAT he wanted was not in Paracelsus nor yet in Sendigovius. He

ran through many volumes before he found the Elizabethan

translation of an obscure treatise written by a Portuguese monk.

It dealt with charms and amulets chiefly, but there was a section

on potions. Elmer sighed happily when he turned a page and saw

staring him in the face the following caption: "For Courtiers and

Supplicants Desirous of Winning the Favour of Monarchs and

Potentates."

That was it. What he wanted exactly, for he knew from a letterhead that Hannigan was Grand Potentate of the Mystic Order of the Benevolent Phoenix. It was a natural, so to speak—supplicant, favor, and potentate—all the elements were there. He began scanning the list of ingredients.

That night he brought Bettie to the laboratory with him. She loved him so hard she could not bear to have him out of her sight. Together they mixed up the brew that was to make Hannigan eat out of Doc's hand.

First there was the heart of a dove, no color specified, to be stewed in the fat of a red bullock, calcined in an aludel with the kidney of a white hare and some virgin wax, and the resulting mess was to be treated elaborately in a retort together with sesame, ground pearls, and dill. Dill puzzled him until Bettie looked it up in another book and found out it came from a plant called Anethum Graveolans. The book explained that a pale- yellow aromatic oil was distilled from the seeds, and that it was good for flatulence.

"That ought not to hurt Doc or Hannigan either," grinned Elmer, when he found out that flatulence meant "windiness."

He dumped his mixture into a container, added the correct quantity of Doc's own blood, which was fortunately available, and shoved it into the queer antique furnace Doc had built and called an athanor. That was, as the directions said, "to rid it of its dross and bring it to a state of quintessence most pure." Patiently, hand in hand, the two lovebirds regulated the heat of the athanor as the sticky mess went through the successive states of purgation, sublimation, coagulation, assation, reverberation, dissolution, and finally descension.

It was midnight when the "descension" was completed, and after carefully blowing his nose Elmer broke the crust on his crucible and began to draw off the pale moss-green oil that was in it. There was enough to almost fill an eight-ounce bottle. It must have been of the quintessence most pure, for the stuff put in, originally, counting a couple of pints of Theriac, would have filled a top hat. Elmer was very well pleased with himself. The Aromatick Unction looked exactly as the book said it should look. He tried to judge the odor of it, but his sense of smell was hopelessly wrecked by his hay fever.

"What do you think?" he asked, pushing the bottle under Bettie's nose.

"I think," said Bettie, with pronounced enthusiasm, "that Dr. Tannent is the wisest, kindest, most deserving man in the whole, whole world, and I would give him anything I owned. Why, he's—"

"Don't you think you're just a little susceptible, hon?" growled Elmer, not pleased at the implied comparison. Then he remembered that ice-cream soda. It was the potion! He couldn't smell it; but she could. He had hit another bull's-eye!

"Come on, baby, get your bag packed. We're going to Cartersburg."

ON the bus Elmer studied the instructions. The alchemist who had

first hit on the prescription evidently had thought of

everything. The chances were that any courtier needing such a

potion to get what he wanted was also in bad with the king, so

that it was made potent enough to work through the air. The

subject was to anoint himself thoroughly with the unction, and

also carry a small vial of it in his hand. Properly prepared, the

stuff would cause sentries and guards to bow reverently and make

way, and it was solemnly assured that, once in the presence of

the potentate, anything he asked would be granted. In proper

strength, anything he wished for, even, would be granted without

the asking.

"The raise is in the bag," Elmer told Bettie, giving her a little hug.

When they got to Cartersburg they found to their dismay that the convention had already met for the main event of the week—the nomination of the next governor—and the hall was packed to the doors. There was no admission without special tickets, and all those with authority to issue the tickets were already in the hall. Doc Tannent, apparently, was in there, too, perhaps still trying vainly to get in touch with Hannigan. Elmer considered anointing himself with the unction until he remembered that it was Doc's blood, not his, that was in the compound. Whatever effect it had would benefit only Doc.

He tried to get in the side door by slipping the doorman a little change, but the doorman said nothing doing. He took a try at the basement, but a gruff janitor shooed him away. Elmer backed away from the building and studied it from the far side of the street. That was when he noted the intake for the big blower fan on the roof, and saw that it was an easy step onto the parapet by it from the next-door office building. He grabbed Bettie's hand and made for the entrance to the office building.

They had little trouble getting into the intake duct. It was a huge affair of sheet metal, obviously part of the air- conditioning system, and its outer opening was guarded by coarse wire netting to keep out the bigger particles of trash, such as leaves and flying papers. Elmer, without a moment's hesitation, yanked out his knife and cut away an opening. He figured there would be a door into the duct somewhere to allow access to it for cleaners coming from the inside of the hail.

Elmer led the way, gingerly holding the bottle in one hand while clinging to the slippery wall of the duct with the other. Bettie stumbled along behind. It got darker as they went deeper, but presently Elmer saw the cleaning-door he was looking for, only it was behind yet another filter, which meant another cutting job to do. A few yards beyond the door an enormous blower was sucking air into the auditorium, and the draft created by it was so strong that they were hard put at times to hold their footing on the slick metal deck under them. But Elmer tore at the second screen and worked his way through the opening in it.

For a moment he was convulsed with a miserable fit of sneezing and coughing, for in ripping apart the screen he had dislodged much dust. Then he started swearing softly but steadily. Bettie crawled through the hole after him and cuddled up to him consolingly.

"Whassa matta, sweeticums?" she cooed.

"Dropped the damn bottle," he snuffled, "and it busted all to hell."

He had. He struck some matches, but the wind blew them out. Then he worked the cleaning door open and a little light came in. All there was at his feet were some bits of broken glass—not so much as a smell of the precious Aromatick Unction was left. Elmer looked sheepishly at the remnants, and then, in an effort at being philosophical, he said:

"Oh, what the hell! Come on, as long, as we're here, let's watch 'em nominate the new governor. It's fun to see the way Hannigan builds up his stooges. A coupla speeches is all it takes to turn a stuffed shirt into a statesman."

THEY wandered around the attic for five minutes or so before they

found the steps that led down to the gallery of the hall. The

gallery was packed, and they couldn't see at first because

everybody there was jumping up and down and yelling his head off.

That was surprising, for it generally took a nominating

convention a couple of hours to get past the dry introductions

before they uncorked their enthusiasm and really went to town.

Then Elmer recognized that the yelling had settled down to a

steady chanting. He heard the words, but didn't believe them—not

at first. It just couldn't be. But what the crowd was calling,

over and over again, were the words:

"We want Tannent! We want Tannent! We want Tannent!"

Then they stopped the yelling in unison and let go, every fellow for himself, in what is technically known as an ovation. A high voice from down on the main floor sang out, "Tannent—ain't he wonderful!" and right away the whole auditorium took that up and made it into another chant.

Elmer gave a startled look at Bettie, but she was as bad as the rest. He marveled that he had ever thought her beautiful when he looked at her red face, eyes bulging, and the veins standing out all over. She was yelling her lungs out for Tannent. A man on. the other side slapped Elmer on the back and said something about what a grand guy Tannent was and what a swell governor he would make, and how happy he was to be able to vote for him. It was all so silly.

Elmer deserted Bettie and fought his way down the aisle until he reached the rail where he could look down onto the main floor. The band was playing "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow" and the shouting had reached heights of insane frenzy.

Something unprecedented had stampeded this convention, and Elmer, as soon as he had taken the precaution to blow his nose once more and dab the water out of his bleary eyes, hung over the rail and tried to spot the center of the commotion.

He found it. Big Tim Hannigan was plowing his way through the dense crowd beneath. Doc Tannent was sitting piggyback on top of the boss's shoulders, smiling and bowing and waving to the crowd! Men went crazy as he passed, trying to get at him to shake his hand. Elmer went crazy, too—with amazement.

And then he tumbled. It was his philter—his potion to soften up the potentate and make him give what was asked for. When it had been spilled in the air intake, the conditioning system had spread it through the auditorium and everybody was affected. They were trying to give Doc what he wanted. It didn't matter what—just whatever he wanted. "Tell us, Doc," yelled one delegate, "what'll you have? If we've got it, it's yours!" It was a powerful philter. Not a doubt of that.

By that time the bigwigs were on the rostrum—Hannigan, the incumbent governor and some others.

There was Doc, his bald head glistening and his little goatee bobbing up and down, making a speech of some sort, and not stammering while he did it, either. Hannigan, the big grafting gorilla, was at one side, beaming down on Doc with exactly the expression on his face that a fond mother wears when her baby boy steps out onto the stage at a parent-teacher's meeting to say a piece. And Hannigan's wasn't the only mug there like that. Everybody else looked the same way. Even the hard-boiled, sophisticated newspaper boys fell for the philter. The slush they sent their services that night cost several of them their jobs.

THE old governor broke three or four gavels, pounding for order,

but finally got enough quiet to scream out a few words. Elmer

suddenly realized that Doc. Tannent had already been nominated

for governor; the hubbub he was witnessing was the celebration of

it. Or maybe the crowd, in their unbridled enthusiasm, merely

thought they had nominated him for-governor. At any, rate,

this is what the old governor said:

"Please! Please! Let me say one word—"

(The crowd: "Go jump in the lake—scram—we want Tannent!")

"—I realize my administration has been a poor thing, but it was the best I could do. Now that we have nominated a real governor—"

(The crowd: "Whee! Hooray for Tannent!")

"—I resign here and now, to make way for him."

The crowd cut loose then and made its previous performance seem tame and lukewarm by comparison. Some kill-joy, probably another man with a bad cold, jumped up and remarked that the resignation of the governor accomplished nothing except the elevation of the old lieutenant-governor to the highest office of the State. Whereupon the lieutenant-governor promptly rose, flung his arms around Doc, and then announced that he had appointed Doc to be lieutenant-governor. Whereupon he resigned. That made Doc the actual, constitutional governor—on the spot.

There was a brief flurry that marked the ejection of the kill-joy from the hall, and then the assembled delegates cast the last vestiges of reserve aside and proceeded to voice their happiness. The steel trusses overhead trembled with the vibration, and the walls shook.

Doc was governor! Elmer was stunned. He had wrought more than he intended. That "quintessence most pure" must have been simply crawling with hormones favorable to Doc.

But there was more to come. In the orgy of giving Doc what he wanted, or what they thought he wanted, the legislature resigned, one by one.

Then Doc appointed their successors on the spur of the moment —according to what system no one could guess. But nobody was sane enough to want to guess—except Elmer, and he was too astonished to think about a little thing like that.

What nearly bowled him over was the consummate poise and masterful manner of Doc himself. It was as if Caspar Milquetoast had elevated himself to a dictatorship, only he carried it off as if to the manner born. Elmer knew the answer to that, but he had not foreseen it. Doc had had a few whiffs of his own philter, and was in love with himself. He believed in himself, for the first time in his life, and it made a whale of a difference. He was bold, confident and serene.

Completely flabbergasted by the turn of events, Elmer turned and started to force his way up the aisle to where he had left Bettie, when a new roar broke through the reverberating hall. It was a new note, a superclimax if such a thing were possible. Elmer turned back and gripped the balcony rail, staring down.

Hannigan was on his feet, weeping like a brand snatched from the burning at an old-fashioned revival meeting. He was making a speech, if one could call such a sob-punctuated confession a speech, and it tore the lid right off the meeting. In the pandemonium of noise, Elmer could only catch a phrase here and there. "Clean government is what you want, and that is what you'll get... many times in the past I have... but now I bitterly regret it. My bank accounts are at the disposal of the State treasurer... will deed back the public lands I... glad of the opportunity to make restitution. I will give you a list, too, of the many unworthy appointments..."

Elmer slunk up the aisle; he could bear no more. It was all very confusing. He had counted on nothing like this. If Hannigan had turned saint, it was even a greater miracle than putting hair on the fumbling, shy little Doc's chest. Elmer shuddered at that last crack. Unworthy appointment, indeed! He must get hold of his uncle right away. He had quit worrying about whether the new governor would remember that he came to Cartersburg to get the raise for him; what concerned him now was whether he still had a job.

Eventually he found Bettie, exhausted and hysterically weeping. She was awfully happy about Tannent, Elmer grabbed her hand and dragged her from the place.

THAT was how Doc Tannent got to be governor.

No, Elmer didn't get the raise. He didn't need it. A week later Bettie quarreled violently with him. The day after that she pulled his hair, stamped on his foot, and scratched at his eyes. The day following she went after him with a knife, and had carved several long gashes in him when the cops pulled her off and took her away.

Elmer, after they had finished bandaging him and put him to bed, told the attending physician the story of his conquest of Bettie. He could not understand her sudden revulsion to him. He even gave the doctor the list of ingredients in the love potion.

"That's bad," murmured the doctor, looking very profound. "Maybe it would be well if I took a blood specimen from her to see what's there."

A week later the doctor was back, and his expression was grave. He had with him a fourteen-page report from the biological bureau, and there was a lot in it about hormones and antibodies, toxins and antitoxins and other biological jargon.

"When she ingested that potion you gave her," said the doctor in his most severe manner, "she introduced in her system some strange and powerful organisms. Being a healthy girl, her body naturally resisted those foreign organisms. She built up antibodies to counteract them. It appears that she overdid. She is now immune to your influence."

"You mean," moaned Elmer, "she is going to not like me as much as she did like me?"

"Yes," said the doctor solemnly. "I am afraid that is the case. And it will be permanent. Fools, my boy, rush in where angels fear to tread."

Elmer closed his eyes and for a few minutes felt very faint. Then he suddenly thought of Doc Tannent, of whom he had said nothing, to the hospital doctor. "Oh, gosh! Doc!" he wailed, and begged the nurse to let him put in a telephone call to the governor.

It was no good, though. The governor wouldn't receive the call. He was too big a man that week. It was not until the next week that the antibodies began to propagate inside the lads of the Hannigan gang. And then—oh, boy!