RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

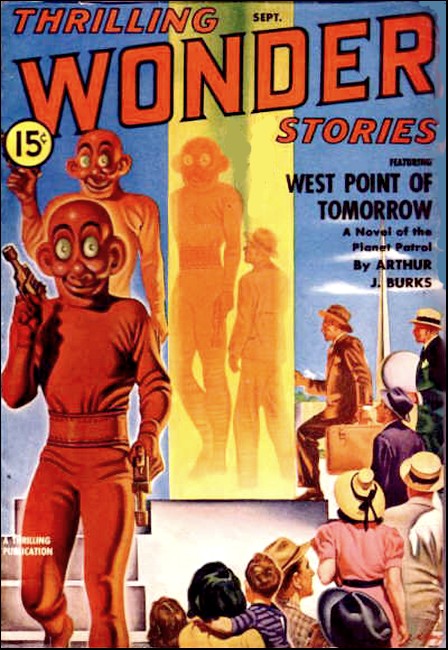

Thrilling Wonder Stories, September 1940, with "Prospectors Of Space"

"Join Spaceways and See the Universe" was the slogan

for all pilots—but not if you wanted a place in the Sun!

NEIL ALLEN called his father. In their cumbersome space suits the two stood in the twilight that passes for day on distant Triton. Their face plates were turned toward the jagged Dolphin Range, where the cabin lights of at least three space ships flickered. A stabbing searchlight streamed down from the leader, probing the frozen wastes below.

Old man Allen's hand gripped the button of his phone transmitter.

"Solar Exploitation has come to take over, son. They're looking for us."

Neil's father had foretold this. It meant the end of his career. With the preemption of Triton would come the end of space prospecting. The Metal Trust had already absorbed everything in space. But the Allens had hoped they would be unmolested on far-away Triton.

Working by the light of torches, the twelve members of their crew were slicing away slabs of rhodium. In three days more they would have had a full cargo, a profit at last on the expensive round-trip from Neptune to the nearest Solar Exploitation refinery on Callisto.

The first ship of the Exploitation flotilla sighted the little wild-cat mining expedition. It settled to the floor of the crater, the two subordinate ships following. Flood-lights switched on, the space-lock opened, and three men in space suits stepped out.

Old man Allen had been through this little ceremony before. He knew just how helpless he was. In the old days, he and his crews had fought the claim-jumpers on the spot. But the Mining Law stopped that. It pretended to permit prospecting on any "uninhabited planetary body" while it gave monopolist rights to any organization that would colonize and exploit it systematically. He had fought that in the courts, and lost. The Law promoted orderly production, the politicians said, and curbed speculation.

The three strangers arrogantly advanced to the senior Allen and handed him a metal tube. In it was the duly certified eviction notice.

Horvick, General Superintendent of Space Mines, spoke harshly.

"You have your notice, Allen. Call your men and get out. I'm giving you a break with the stuff you already have on board. Legally it's ours."

"Yours!" retorted old man Allen bitterly. He knew that one of the men confronting him was a captain of the Space Patrol, sent to enforce the Law in the void. He choked back hot words, wheeled abruptly, ordered his men into the Klondike.

THE first week of the long drag back to Earth, the old man

maintained a moody silence. There was no point now in unloading

at Callisto. They might as well go all the way and get the best

price.

The Klondike was a staunch ship, built according to Allen's own plans thirty years before. Neil Allen had lived aboard her since he was a little tot. He knew the paths among the planets as well as old harbor pilots knew their rivers.

They passed within twenty million miles of Saturn. The old man sat at the starboard lookout port, gloomily eying the beauty of the ringed planet and its spectacular family of satellites. He knew he would never see them again.

Neil fiddled with the instruments. His steady eyes filled with concern for he realized how heavy this last blow had been.

"Neil," said his father at last. "For my own life, I have no regrets. This Triton business doesn't matter—I should have retired five years ago. But I did wrong in apprenticing you to a dying trade. All you can do is hire out to Exploitation."

"Not a chance, after what they've done to you."

"Let's face facts, Neil! Space prospecting is a thing of the past. As a free-lance, I was able to follow my hunches and not have to wrangle with a bunch of Earth-bound directors. You won't be able to free-lance. You've learned an obsolete occupation. In my day, there was the whole Solar System to work in. Buck Bowen and I were the first to mine the craters of the Moon. We moved on to Mars, then to the moons of Jupiter.

"That was when they passed the Mining Law. Exploitation came after us. They let us eliminate the poor spots, find out the dangers. But when we started bringing in loads of high-grade stuff regularly, we knew that Horvick, and his gang would be along soon. Bowen and I split up after they grabbed Callisto. He thought there was more chance in the planetoid belt. I thought surely they would let me alone around Uranus. Remember our camp on Oberon? They hounded Bowen the same way. One asteroid after another they took from him. The richer ones they towed in bodily, smelted them down entirely. Two years ago Bowen was doing fine with indium ore in the Anterior Trojans. Well, he's dead now—ruined by Exploitation. You might look up his son, Sam, when you get back. He's in the same fix you are—educated to be a prospector, with no place to prospect."

The old man bravely tried to tell some anecdote of the old days. He couldn't finish it. Haggard and worn, he went to his bunk.

WHEN Neil turned the Klondike's nose downward to pass

beneath the asteroids, the old man handed him an envelope.

"Neil, this is my will. You'll have the Klondike and this cargo. There's a little money, too, in the Stellar Trust Company. I don't know what you'll do when that's gone. It ain't much."

"Cut it out, Dad. The System still has some unknown corners."

Allen shook his head. In the last few days he had weakened rapidly. The driving force in his life had been hard work. Neil groped for a suggestion that would renew the old man's urge to live.

"Dad, you were going up out of the ecliptic some time and look around. When we dump this load, let's do that."

"Not me," Allen answered wearily. "That's for you and Sam Bowen. Even with new methods it'll be a gamble. Play safe, Neil. You're as good at astrogation as you are mining. Get yourself a safe job."

"That's out!" declared Neil. "I'm following your lead as long as the old Klondike holds together!"

"Well, if that's the way you feel, go bring me that diamond-studded meteorite from the drawer of my desk."

Neil brought him the jagged piece of rock.

"This is what gave me my start in life. Bowen and I found tons of them that had fallen into the craters of the Moon. One summer we saw them, picked them up still hot. Draconids, they call them, and they have never been found anywhere else. That thing is nearly half-pure iridium." He fondled the aerolite reminiscently. "Maybe this is the answer for you, and for Buck's boy, too. Only, watch your step. It would break my heart if I thought you made the biggest find of all, and then had that skunk Horvick cash in on it."

Allen closed his eyes. Neil waited, but the old man had dropped off to sleep. He never woke up....

AFTER his father's funeral on Earth, Neil Allen wasted no

time in the personnel offices of the big companies. There was

only one that he knew much about. But the thought of that one

filled his heart with bitter rage, a hatred he focused on

Horvick, its managing director and principal stockholder. His

love of independence, inherited from his father, made him scorn

employees as mere robots manipulated by schemers.

Instead, he planned. If tons of Draconids had been picked up on the Moon, there must be billions of them in space somewhere. After he sent a letter to the last known address of Sam Bowen he haunted the Planetarium and the Geological Museum. He made himself familiar with the workings of the Assay Office, the one place in the Solar System where reasonably pure metals could be sold without having to deal with the Metal Trust.

He concentrated on the meteor swarm known as the Draconids, and their related group, the December meteors, out of Scorpio. He learned all that was known on Earth about their orbits, their frequency, and their composition.

In three weeks his plan was clear. The old Klondike was cradled in the great central bay of the United Sky-yards machine shop; Neil was all over the place, from drafting room to armature shop, checking the details and construction of his two pairs of electro-magnets. Then came the work of installing them in the roomy cargo blisters that bulged from the Klondike's sides. His only helpers were Jim Hathaway, long-time Mate of the Klondike, and five other members of the crew who had elected to stick by the ship. For years they had worked on the share basis.

It was in the Klondike that Sam Bowen found Neil the day before the job was finished. Sam's father's death had occurred about a year sooner, and he had already spent most of his modest inheritance looking for work. All he had left was the twin sister of the Klondike, Buck Bowen's old Golconda.

"It's tough," Sam declared venomously. "We won't sell ourselves to the Exploitation outfit, and Transgalactic Spaceways pays practically nothing. They can get all the pilots they want from kids that fall for the 'See the Universe' line. So what's left? Assay Office. That's loaded to the gunwales with political slickers. We're licked."

"Like hell we are," flared Neil. "There's still a frontier. We'll do what Columbus did; what the old Forty-niners did, what your father and mine did. We'll make jobs for ourselves!"

"Yeah?" retorted Sam. "Out around Alpha Centauri or Tau Ceti. If they have planets, all we have to do is find a pair of females dizzy enough to marry us, and start out there on our honeymoon. Our kids could do the mining when they got there, and their kids could bring the stuff back!"

"Back down, Sam," interrupted Neil. "Listen to me. Did you ever happen to think that every explorer and prospector in history has stuck to the plane of the ecliptic? Of course the smart ones duck under the planetoid belt to skip a hammering. Your old man may even have chased a fat asteroid up ten degrees or so. But who really knows anything about what's above us or under us?"

"We have telescopes, haven't we?" countered Sam. But he was willing to listen. "Nobody wastes rocket fuel zipping around up there because nothing's there but a lot of scattered gravel and dust. You couldn't locate a ton of pay dirt in a million cubic miles. And if you did, it's hell working in a hail of iron nuggets. Why, out on Ceres—"

"I know, you had double repulsor screens. But do you think you could stand an iridium hail if you had a bucket to catch it in?"

Neil sketched his plan. His father had learned that the meteor streams were really the debris of a defunct comet—Jenkins 368. It had long since disintegrated and scattered over its orbit, which intersected Earth's at an angle of about eighty degrees. The June and December meteors marked the nodes.

"All we have to do is plow along the orbit and gather 'em in," concluded Neil. "Not forgetting they are only half iron. The rest is iridium, rhodium, and stuff like that."

"But my Golconda isn't fitted with magnets. Where do I come in?"

"As a pack-horse. I figure to act as a sort of base ship. If I had to work it alone, I'd trail along until I caught a full load, then break away and come in with it sticking to me. But with you in the game, we can get several loads. You can peel me off every so often, bring a load in and sell it, and then come back for more. That way, we won't risk losing the swarm."

"If you ever find it, and there's anything there." Sam was still dubious. "Comets are thinner than smoke, even when they're all together."

Neil shrugged. "If prospecting was a sure thing, there wouldn't be any money in it. I know old Jenkins three-sixty-eight is spread out thin, but you can't laugh off those iridium meteors. If you want to come in, I'll swap a half interest in my ship for a half in yours. How about a partnership, Sam?"

"Well, it'll be a lot better than staying grounded." But a sudden doubt swept Sam's mind. "If we do clean up, what's to prevent Horvick from butting in with a fleet of Exploitation ships and sweeping the orbit clean?"

"Time, for one thing," replied Neil. "He's still out at Triton. They have no magnet-equipped ships—haven't even thought of it. If we work fast, there won't be anything left for them."

The next day the Klondike was ready. But the Golconda was still laid up. Sam would gather his crew and take on fuel and provisions. Neil furnished him with a copy of the coordinates of his proposed trajectory, which he could follow in a week.

Jim Hathaway raised the question of what should be done with the mining gear the senior Allen had used. Neil ordered it all stowed in the cargo blisters. Since the ship's function was to act primarily as a magnet, the more massive she was, the better she would attract and hold the cosmic litter.

It was already June when Neil took off for the Moon. The Draconids were due to appear in a few days. He preferred to wait on the Moon. With no atmosphere, the visibility was better, and the take-off into the midst of the meteor swarm would be easier against the lesser gravitational pull.

He set the Klondike down in a roomy crater. Employees of the Exploitation company were already there, waiting for the semi-annual shower, to pick up the sky-nuggets as soon as they fell. The lunar manager of the company visited the parked Klondike and growled at them for trespassing on company property.

Neil glibly quoted the law permitting transient vessels a three-day stay. Since his crew was not mining, the lunar manager could do nothing but walk away, muttering. However, he set a guard over the ship to see that no minerals were picked up.

AS soon as the shower started, Neil closed his hatches and

fired his rockets. Along the old comet path he went, picking up

speed. He turned on his repulsor screens, keeping a close watch

on the needle as it registered the hits of meteors.

Gathering acceleration, he maneuvered cork-screw style, feeling for the center of the stream. When he was receiving the maximum of hits from the rear, he knew he was on the axis of the meteor stream. He straightened out, altering his course slightly from time to time to conform to the ellipse of the orbit.

It was several hours before the pelting from the rear ceased. He cut his rockets and drifted. He had a trifle too much momentum, for now the pelting came from ahead. He was overtaking the sky-gravel.

Cautiously he shot a few measured jets from his bow tubes. He jockeyed the Klondike until she was moving along among the perihelion-bound particles at little more than their own speed.

He swept the space about him with a spotlight. He had expected to sight bits of matter of all sizes floating near him. Instead, all the light revealed was an almost milky haze. Occasionally he caught the glint of reflected light from some tiny object, but the myriad of glistening nuggets he had hoped to see were missing. For space, though, the area about him must be unusually full. Never before, outside the atmosphere of a planet, had he been able to see the beam of his searchlight.

He cut his repulsor screens and started the huge generator. The instant it roared up to full speed, he threw a switch and set up his synthetic gravity field.

It was fully an hour before he noticed any result. He had expected to hear a rain of pellets against the hull, was even afraid that some larger aerolite might come crashing through. He alternated between the lookout ports, staring into space. In the pale beam of the searchlight, all he could see was swirling wisps of milky haze. At intervals a light thud told of a sizeable particle slamming against the skin.

Before long he noticed that the outer rims of the ports seemed to be encrusted with frost. Frost in the void? Impossible! But there it was, silvery, clinging to the port frames and hull. Several inches of ice covered the metal parts, growing swiftly until the glassite panes became opaque.

He raced below and checked his generator panel. Undoubtedly there was a powerful magnetic field all about the ship. He donned a space suit and mounted to the upper lock. When he slid back the outer door, he was almost smothered by the fall of incredibly fine metallic dust. But he shook it off and climbed out on the roof of the ship.

Nothing in his short young life had prepared him for the spectacle that greeted him. Beneath his feet the Klondike appeared like a huge frost-covered watermelon. All about him, illuminated by the beam of the searchlight, was a wan fog through which fell a silvery rain of almost invisible fineness.

He stooped and tried to pick up a handful of the star-dust at his feet. But as he lifted his hand, the powder slithered out like smoke caught in a gale. It flew back to the magnetized hull. He noticed that the surface was pock-marked with tiny craters. Even as he looked, a fragment the size of a ping-pong ball whizzed past his head and embedded itself in the silvery dust.

Before Neil went below, he gathered up a bucketful of powder from the floor of the space lock. He and Jim Hathaway analyzed it in their assay booth. It was the same substance that formed the larger Draconids.

Inside the ship there was no way of knowing how thick the adhering matter had become. Usually they would feel the light pattering as they cruised through some thicker portion of the meteor swarm. But that was punctuated at intervals by the heavy jar of some greater chunk hurtling through the void.

At the end of the third day Neil led his men to the space lock. Before they had slid the outer door open two feet, they were half buried by the avalanche from above. Working with scoops and buckets, they had to clear the lock and get the surplus comet debris into the cargo blisters.

The crust on the ship was a couple of yards deep. Neil realized that by the time the Golconda reached them, he and his crew would be hopelessly imprisoned in the nucleus of a fast growing body, adding shell upon shell to itself, like the layers of an onion. He was reluctant to cut off the generator, but this was getting to be too much of a good thing.

Outside the ship, he tried to cut back around the space lock. He had to send some men to clear away the openings of the rocket jets. But the dust was so powerfully gripped by the magnetic field that it acted as if it had been saturated with heavy glue. Even when they succeeded in loosening a shovelful, it flew back the moment an effort was made to move it.

Neil left the men struggling with the outer crust and went below to the cargo blisters. He clambered over the old mining equipment that filled them. Thoughtfully he stared at the sectional tubing of the old Saturn extension trunk. Then he called Jim Hathaway.

HE had found the dismantled shaft his father had used to

penetrate the soupy top-soil of Saturn to get at the silurium

deposits. The sections were each six feet long and about three

in diameter, the ends flanged inward so the segments could be

bolted together. Inside were cross pieces that made a ladder

when assembled.

It was a troublesome job to adapt the first of the segments to the frame of the space lock door, but they managed it. Adding segments above was simple. By the time they knocked off for the day, eighteen feet of trunk led up through the accumulation of dust and gravel.

"Looks like the funnel on an ancient steamship," Neil grinned at Hathaway. They stood on the topmost rung of the ladder and hung over the top, looking down at the shining hull. "But it gives us a way to get in and out. There's enough on here for the night, so let it rain."

The next day, Neil found the level of the cosmic dust almost to the top of the extension trunk. He made it routine to add another segment every eight hours.

Trying to compute the total amount of his haul, if weighed on Earthly scales, he whistled in astonishment. If they could lay it down at the Assay Office, it would be the most tremendous fortune in the System!

By the time television contact had been made with the approaching Golconda, the Klondike was buried ninety feet deep within a shell of iridium dust.

"Where are you?" Sam Bowen asked, from the television screen in the Klondike's cabin. "My graviscope says you're within a few miles, but I can't see you. I found a swell little asteroid, though. Looks like silver."

"Okay," acknowledged Neil with a chuckle, as he realized what the Klondike looked like from a great distance.

"Land on it. I'll meet you there."

When they heard the final braking blast of the Golconda, Neil and his men climbed topside to greet the other crew. Sam Bowen stared at the men clambering out of a hole in the ground.

"What happened?" he yelled. "Where's your ship?"

Neil pointed down. "You're aboard it. We've been gathering ore while we were waiting for you."

He led Sam to the head of the Saturn trunk and showed him the lights of the cabin glimmering nearly a hundred feet below. Sam's eyes went round with astonishment.

"Hey!" Sam gulped. "If we land this on Earth, we're rich! Exploitation will be ruined!"

"Just about," agreed Neil grimly. "Their mines on the outer planets won't be worth a dime a dozen. Not with their low grade ore and that long haul!"

THE Golconda's blister hatches were open, the magnets

cut off. Madly the two crews began shoveling the rich dirt into

the holds.

Just before the Golconda was ready to shove off on her Earth-bound trip, Neil called Sam aside.

"Here's a ball of money, all right. But getting it in is going to be a bigger job than I figured on. I'm out of control already. I don't dare blast a jet. It'd backfire and wipe us all out. The Klondike is practically a celestial body. We're set on this orbit. For the next four months everything will be swell—until we pass the other node. After that, it's outer space.

"When you get in, charter some freighters to help you cart the stuff. There are only a couple of hundred feet more of this Saturn trunk. When that's used up—Well, you can see for yourself that we can't afford to grow too big."

"You won't grow so fast now," observed Sam. "Think how much more volume it takes to add a yard at this diameter."

"And think how much more mass I'm getting all the time! It adds to the pull. By the way, when you cash in on this load, drop by the Systemic Stock Exchange. Sell short every share of Exploitation Common you can margin."

Sam Bowen gasped. "You certainly believe in shooting the works, don't you?"

"Why not? This is beginning to look like a one-shot proposition. I expect to get more fun out of chopping down that skunk Horvick than out of the money."

"Maybe so," admitted Sam. "But Horvick won't take it lying down. Our dads were pretty foxy, and he cleaned 'em every time. I'm with you a hundred per cent, but he's got me plenty worried."

"Trot along and dump this load. I'll do the worrying while I'm waiting for you to come back. If Horvick tries some funny stuff, I should be ready with the answer."

During the eight days that the Golconda was absent, the newly formed "Klondikoid," as the men called it, grew another hundred and fifty feet in radius. It was fast becoming an imposing member of the Solar System. Though it was intolerably hot below, since the hull radiation had been shut off, Neil kept his generator running. The men could take turns on the top-side, but the gathering of the iridium must go on.

When the Golconda did return, she returned alone.

"Eight million sols!" Sam shouted ecstatically, waving a sheaf of papers.

He told of his descent to the sky-docks of the Assay Office, how he slid his cargo into the appraising vats, and the assay report. The metal was pure and easily separable by the swift D'Orgmenay process. The worthless iron was washed away, leaving the fifty-three per cent remainder, which proved to be all metal of the platinum group. There was also about half a bushel of small diamonds to each ton of dust.

"Fair enough," grunted Neil. "What luck did you have chartering ships?"

SAM'S face fell. "Horvick was at the Assay Office when I

landed. He nearly had fits when he saw what I'd brought—wanted to

know where we were poaching. He had a catalogue of every known

body in the System, said they owned all of 'em that had any

valuable minerals."

"Yeah?"

"Well, I just said his catalogue needed revision. But when I got out to Sidereal Sky-docks, I found he had taken options on everything that could get off the ground. He must have had a hunch. Anyway, none of the ship-owners could do business with me."

"You poor fish!" Neil said. "I'll bet you tipped your hand by selling his stock first."

"What was wrong with that?"

"Never mind. The eight million wasn't so bad. Shake a leg now. Get in with another like it."

Neil smothered his disappointment. A dozen ship loads, more or less, would not more than dent this spheroid. Getting this aggregation of metal to market was going to be a major operation, like towing in an asteroid. But there was plenty of time to consider that. They were still more than a month from perihelion.

After the Golconda had disappeared Earthward, Neil and Jim Hathaway took stock of their situation. There were seven sections of the Saturn trunk still unused—enough to last at the present rate of growth until the Golconda returned. The second day, however, they ran into a cluster of heavier meteorites and had to add two segments within eight hours.

"This is getting out of hand," said Neil.

He ordered the generator cut off. It made no difference in the rate of accretion. The hull of the Klondike and the surrounding shell of forty-seven per cent cosmic steel had become permanently magnetized by long soaking in the strong field of the electro-magnets. The dust and gravel continued to land.

Neil went daily to the topside, to check his position and watch the falling Stardust. As he stepped out onto the pock-marked surface of his synthetic planetoid the day the Golconda was due, he gave his usual glance at the Sun.

Around the flaming globe was a magnificent halo of pale light and several parhelia of greenish tinge. Haloes and parhelia in space? There must be an atmosphere of sorts here. He looked at the sky back of him. Another pale, shapeless area of light marked by a solid black spot, glowed diametrically opposite the Sun.

He looked from it to the Sun and back again. The dark hole was obviously a shadow thrown by the "Klondikoid." But a shadow set off from a luminous sky was an absurdity in the void. The amazing sight held him, despite the constant hazard, of the missiles flicking about his feet. The sky away from the Sun was taking on a brighter tone. He saw that the brilliant part was roughly annular, covering nearly half the field of his vision. It was not until then that he noticed its source.

Like snow whipped by a gale from the crest of a drift, powdery metal of almost molecular fineness was flowing along the tangential rays of the Sun that swept the shadow edge of his planetoid. Rather, they were flung away in vigorous straight lines, as moonbeams fall. The light pressure was tearing at the finer particles and sending them flying into space! That vague light must be visible for untold miles!

NEIL'S heart thumped at the full realization of his position.

His Klondike, buried beneath him, had reassembled the

ingredients of the scattered Jenkins 368. That ancient comet had

been reborn. The incredibly fine dust hurtled along by the light

waves of the Sun was its new-grown tail! Then the halo and

parhelia Sunward must be the illuminated other edge of the debris

stream.

He made sure of his observations, then scuttled down the trunk and ran to the televisor to call the Golconda. Seconds seemed hours before he succeeded in raising the anxious face of Sam Bowen.

"How far away are you?" he demanded.

"Pretty close—about half a million miles," responded Sam. "But what about the comet? Is it anywhere near you?"

"Near me?" yelled Neil. "Hell, I'm it! What do we look like?"

Bowen shook his head.

"I can't make you out yet. But there's a fine bright head, about ten degrees toward the Sun from where I think you are. The fanciest thing you ever saw in tails is running straight the other way for millions of miles."

"That's all I want to know. Hurry down here. I'll let you have a ringside seat—smack on top the nucleus!"

Ten hours later the Golconda was resting on the "Klondike."

"Too bad you can't see yourself," Sam said. "From a distance it looks like you were melting, being blown straight down to the nadir of everything."

"One way to get comet experience," grinned Neil, "is to build one. Or rebuild one. But how did you make out with your last load?"

"Same price. I caught 'em with a posted price, and they had to pay it. But they took the sign down while I was there. Said the next lot would have to be cheaper. Same with the diamonds. Down at the Stock Exchange, I ran into Horvick again. He's sore as hell, shouted that we're riding for a fall. His stock flopped twenty points as soon as I was reported landing at the Assay Office. But I sold some more. We're over a million shares short now."

"Good work. Next time you go in, make a deal with Ecliptic Salvage Company for space tugs to pull me in. That's the only way we can do it."

"Phew!" whistled Sam. "That runs into money. Pop and I dragged a little asteroid down to Mars one time. The tugmasters collected a million sols a day."

"So what?" demanded Neil. "You've already collected sixteen millions for a few parings off this ball. Even at a tenth the selling price, we can't lose."

THE day after the Golconda left, they ran into a fresh

cluster of meteorites. Neil and his crew coupled on the last

segment of the Saturn trunk—and two others they improvised out of

sheet metal. The second day there was no choice but to move onto

the top-side and set up a space camp. They brought up

provisions, air flasks, batteries, and material for a screen

against the falling meteors. They made ready for a siege against

the rigors of the void. Neil was not particularly surprised, a

day later, to see the oncoming lights of a group of space ships.

The leader probed downward with his searchlight, landed, and the

space lock opened. Helmeted figures approached, the foremost one

carrying a metal tube.

Exploitation had come to take over.

Jim Hathaway drew his space gun suggestively, looking at Neil.

"Take it easy," said Neil. "This bandit robs with the Law behind him. That's the weapon we'll use this time. His own racket—in reverse!"

"Which of you is Neil Allen?" It was Horvick's grating voice.

"I am," answered Neil. "And I order you to leave my ship at once."

"Your ship?" snarled the other. "We passed it yesterday. That will be the last load you get away with. Here is the proclamation. Now take your men and get out!"

Horvick flung curt orders to his flagship captain.

Neil turned to the commander of the Space Patrol who had landed with Horvick.

"I appeal to you in the name of the Law. This man has no right to put me off my ship into the void."

"Another space-bug," sneered Horvick, tapping his helmet. "You'd better take him in, Captain. Turn him over to the psychopathic division."

The captain led Neil, protesting his rights, into the police cruiser. Jim Hathaway was cursing vigorously, but Neil silenced him with a nudge. He had just overheard Horvick issue orders to have a fleet of space tugs sent out.

"This comet is pure stuff. We'll tow it in just as it stands. What a haul!"

Horvick was pleased with himself.

THE day the group of tugs hauling the Jenkins comet was reported, the field west of the Assay Office was crowded. The whole population had turned out to witness the unprecedented landing of a comet nucleus on Earth for smelting. On a balcony of the Government Building, Neil Allen also stood watching the handling of the silver spheroid by the Metal Trust tugs. With him, besides Sam Bowen and Hathaway, were an astronomer, an astrogation engineer, the judge of the Court of Interplanetary Equity, and the High Commander of the Space Patrol.

The glittering ball was eased down until it was a scant three thousand feet above the bins beyond the Sky-docks. Eight tugs hovered about it, gripping it with their magnetic rays. The time had almost come for the nethermost pair of tugs to let go and get out from under. Neil was talking to the man beside him.

"It's nothing but dust, finer than the finest flour. All that holds it together is the residual magnetism in my ship. In a moment you will see what I mean. The attraction was sufficient to hold it together in space. It's comparatively nothing here in the face of Earth's gravity."

The two lower tugs began moving out. In another moment they would cast off and dart away. The comet was a thousand feet up, lowering gently.

"Piracy is a grave charge," observed the judge. "If your contention is correct, Horvick must pay you five times the value of ship and cargo. He may be liable to a prison term besides. I trust your complaint is not a frivolous one. It will cost you dearly if it is."

A tremendous gasp, like a rising breeze, broke from the crowd. The two tugs were free, sliding away to the sides. From the bottom of the silvery sphere, tons of shimmering powder cascaded to the ground. No longer held back by the magnetic grip of the tugs, Earth's gravity now had hold of it, ripping it away. For a moment, nothing could be seen but the cloud of metallic dust, surging upward in recoil as the scintillating rain struck the ground.

The crowd pressed frantically back to escape the torrent of iridium dust. But even in their anxiety, men kept their faces turned skyward. The rumor had spread that Neil Allen had accused Horvick of robbing him of his ship and cargo in the void. Horvick had sent Neil back to Earth under guard, charged with lunacy. The Metal Trust had few friends in that throng.

"There she is!" cried Neil triumphantly.

IN the field the crowd was cheering wildly. In mid-air,

where a moment before the "comet" had been, hovered the rusty old

Klondike, a few hummocks of stardust still clinging to her

sides. Thirty thousand witnesses had seen the veteran ship drop

her cargo into the bins of the Assay Office. Now she was in plain

sight of all, firmly held by the grapnels of the Corporation's

tugs.

Exploitation had been exposed at last. Here was piracy, and no man could deny it.

"This'll break Horvick and his company," observed the astrogation engineer.

"That's what I figured," said Neil happily. He patted the book he had almost worn out on his trip down the comet orbit—the "Revised Statutes of the Spaceways." Then he spoke soberly to Sam Bowen. "I guess this squares things for our dads. Too bad they're not here to see it."

"Maybe they are," said Sam, with a gulp.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.