RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a oublic domain wallpaper

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a oublic domain wallpaper

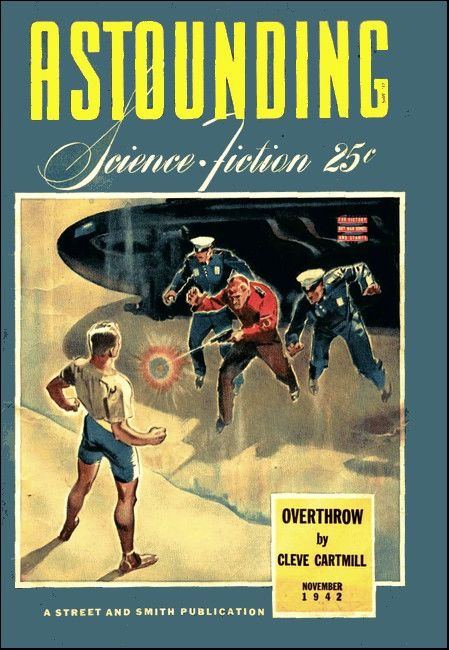

Astounding Science Fiction, November 1942, with "Sand"

Mars is a desert world, a dry, rusted corpse

of a planet. And deserts are always

tricky things—but a world of shifting sand made trickier yet by shifty crooks—

THE grimmest joke on Mars is the daily weather forecast. You see it—if you can see anything—just as you leave the skyport at Ghengiz. It is engraved in inch-deep letters on a monolithic block of permalite, and even that unabradable stone is worn round on the corners from years of sand blasting. The standing prophecy says:

WEATHER FOR TODAY AND TOMORROW.

HOT, DRY, AND WINDY,

WITH SANDSTORMS AND SHIFTING DUNES.

It is a triumph in paradoxes, for it is not only a masterpiece of accuracy, but of understatement as well.

Special Investigator Billy Neville found that out before he had been on the ruddy planet five minutes. The light scout cruiser that had brought him hardly had her grapnels firmly engaged in the deeply anchored mooring net than he could see a small blue police tank careening across the field toward him. He could only glimpse it now and then, for the driving sand was as impenetrable to vision as is flinging sleet. Then the little tank bumped alongside and a moment later a man crawled through the lee entry port. He carried a heavy suit on his arm.

"Here you are, sir," he said, "your anabrad. Put it on over your uniform, otherwise you'd be naked and flayed after about a minute out there."

Neville picked up the garment. It was not greatly unlike a diving suit except that it was unarmored. It was of a tough, rubbery texture, had leaded soles for weight, and a helmet with flexible, unscratchable glanrite goggles. He put it on, shook hands with the skipper of the cruiser, then stepped out into the blast.

The local man helped him into the little tank and pulled down the lid. Then it veered away from the cruiser, rose on one set of treads, and sailed dizzily across the field, heeled over at a sharp angle to the "breeze." The driver slowed at the gate just long enough to grin and point out the forecast for the day. Then he pulled his blue bronco back into the wind and bucked his way up what Neville took to be the main street of Ghengiz.

"The boss'll be glad to see you," yelled the driver, above the steady hissing of the rain of sand on the tank's foreplate. "Things have sure gone to hell here, and I don't mean maybe."

Billy Neville grunted. He had not the faintest idea of what Martian problems were, nor anything about the planet. But it was a safe assumption that when he was sent anywhere, things were tough. Just now he was coming from Venus after a hectic year spent in cleaning up the gooroo peddlers. He had hoped for a few weeks' leave on Earth en route, but apparently that was not to be.

He disregarded his garrulous driver and peered out the sand-stricken visiport. He could not help but notice how peculiar Martian architecture was. None of the buildings had any opening whatever below the second-floor level, and few there, unless on the lee side of the house. All were supplied with rows of grab irons or outside ladders by which the climb from street to door could be made. He guessed, and rightly, that on some days the shifting dunes partly buried the buildings. This day, though, the street was clean and glistening, as if made of polished steel.

The tank teetered and bucked its way ahead, cut a corner, skidded hard against the buildings on the lee side of the street, caromed off and wheezed to a stop before a gloomy structure of heavy permalite.

"Local headquarters," said the driver, and pushed up the hatch. "Take the right-hand ladder."

Neville grabbed at it and climbed, like a rigger going up a smokestack. Two floors up he came to a sheltered platform and a door. The door was yanked open and he darted in. A minute later be was in the presence of a haggard and weary-looking major of the Interplanetary Police. The major was just hanging up the phone.

"Well, Neville," said he, scrutinizing the young S. I. with hard, blue eyes, "you hit here at the psychological moment. The Xerxes has just been robbed. That is the fifth this year, the fifteenth in the last four years. I've ordered a copter and as soon as it comes we'll fly out and look it over while the trail is hot. I am afraid this will be as hard a nut to crack as all the others have been. But maybe I'm getting stale. That's why I asked for you. A new broom, you know—"

"I hope so, sir," said Billy Neville, modestly. He was still wondering what it was all about. He knew that the only industry on Mars was the production of super-diamonds and that there had been a number of robberies of mines. But that was all he did know. In the jungles of steaming Venus one did not bother much about anything but the immediate job in hand.

He waited, but the major did not see fit to speak again. He merely sat tapping nervously on his desk and frowning down at the papers on his blotter. Then he raised his eyes and looked wearily at Neville, but still said nothing.

"Nasty weather you're having," observed Neville, politely, waving his hand toward the outside generally. "Does it blow like this all the time?" The older cop smiled feebly.

"The obvious answer to that crack is the old wheeze they used to use back in Wyoming. No. It does not. It'll breeze along like this for a week or so. Then it'll set in and blow like hell. But if you think this is bad, you ought to see it down in the equatorial regions. They have sand typhoons there. The mines are in the temperate zone with only strong trade winds to worry over. Yet these circumpolar breezes you see up here are gentle zephyrs compared to those." He sighed, and added, "It's not the wind that we mind. It's those damned dunes. They won't stay put. Mars, my boy, is not a nice place to live."

The phone buzzed. The worry on the major's face deepened as he picked up the earpiece.

"Yes?... What! The Hannibal!... How do you know it was eleven days ago?... Oh, hypnosene, eh? They just came to and found the safe blown and looted... I see. Well, do what you can. They knocked over the Xerxes not five hours ago. I'm going there first."

He hung up and spread his hands despairingly.

"Gas, always gas. And always a different gas. First it was cyanogen, then phosgene, carbon monoxide, chloroform. We devised masks. Then they sprung thanatogen, neuronoxylene and other fancy ones. There are never any clues—we can't catch 'em—we can't stop 'em. I'm going nuts."

"It might help if you began at the beginning," suggested Billy Neville, mildly. "You know I got here less than half an hour ago."

"To be sure," replied the major, scribbling on a pad. "In just a moment—"

The phone buzzed again. That time it was a husky voice saying the copter was ready.

"Come on," said the major, buckling on a blaster. "I'll explain on the way."

WIND- and sand-swept Ghengiz faded behind them. They were up

out of the dust. Two navigators were busily taking sights on the

Sun, and on Deimos and Phobos, both, fortunately, happening to be

up.

"The only way you can find your way around this blasted planet," explained the distraught major, "is by stellar navigation. The terrain doesn't mean a damn thing. That range of dunes you are looking at won't be there in another hour. They will not only move west, but they will change their whole contour doing it. Sometimes you see a town—sometimes you don't. It all depends on whether it happens to be buried. We never know. On Earth you can figure the tides, but dunes are different. They move haphazardly and at random rates of speed."

"I'm beginning to find Mars interesting," remarked the special investigator.

"Yeah? Well, listen. Mars is a queer customer. If you know a geologist whose heart you want to break, bring him here and ask him to explain it to you. As near as I can make out, the planet congealed suddenly while it was still a viscous mass of about half iron and half granite, mixed indiscriminately. Somewhere you find outcroppings of steel, in other places stone. Later on it must have acquired an atmosphere. At least we have plenty of it now. That weathered the granite and gave us all this sand. The sand goes round and round and comes out nowhere. At the Equator the dunes are a mile high. At the poles there are no dunes. In between you have every depth. Look!"

He had the copter brought lower and pointed to a deep valley between two ranges of dunes. It looked almost as if there was a mountain lake in its depths. But there was more. A considerable town could be seen in the very midst of the shiny spot. It was a mass of small domes dependent upon a larger central dome, above which rose a slender minaret or smokestack reaching high to the skies. The top of the stack was at least as high as the neighboring dune crests. A turret-like structure sat atop it and sprouted a double ventilator, one cowl turned into the wind, the other away.

"That is a mine—a big one—the Wellington," said the major. "It is sitting on bed steel, and beneath it is a rich pocket of diamonds. When Mars solidified only part of the carbon went into solution in the iron. Bits of it were pressed into Martian diamonds, far harder and of purer fire than anything ever found on Earth. They are immensely valuable. The tough job for a prospector is finding them, for he never gets more than a fleeting glimpse of the real surface of this planet. After that comes the tougher job of building the mine in spite of the steady waves of dunes that roll over it and keep burying it. Once a mine is set, everything is grand—or would be if somebody had not thought up a way to rob them."

The copter rose higher and continued on southward. A little later it dipped again and the major pointed out something else.

"Another mine—the Robert E. Lee, I believe. It's buried now."

Neville looked. All he saw was a tiny circular building supporting a turret. But above the turret stood the same type of double ventilator he had seen at Wellington.

"Until the dune passes," added the major, "they must draw and expel their air through that trunk. It is also an access and escape hatch. What has us stumped is that all the robberies take place while the mine is submerged and yet no one ever enters through the trunk or leaves by it. How they get in and get away is what we want to find out. For they usually kill everybody in it and pick the place clean before they leave. If you can solve that one, you are as good as you are reputed to be."

Neville did not answer. He wanted to know more. After all, promotions in the I. P. went by merit, not pull, and despite the dejection and apparent defeatist attitude of the major, he knew he must have something on the ball. He would not have been made supervisor of Mars otherwise. So Neville merely bobbed his head and continued to listen.

"There's the Xerxes now!" exclaimed the major, indicating a blob on top a sand dune. It did not look in the least like the full-fledged mine Neville had been shown before. It was just another lonely turret sitting on the sand, like the Robert E. Lee.

The copter circled in the sandy gale, made five tries and finally lassoed the turret with her grapple noose. Then they snubbed down and held bobbing against the turret lee.

"You get an idea," murmured the major, "how impossible it would be for a criminal copter to approach the air intake and pollute it. It takes many tries, and at that it is not always successful. When you think of the armed guards at the top of the trunk—"

But they were already being hauled over the parapet into the turret. Four grim-looking men stood there, armed with electronic rifles. On the floor lay a fifth, dead. He was hideously bloated and covered with purple blotches that stood out in great welts.

"Just in time, inspector," said one who appeared to be their leader. "The air below is clearing now. I think you can go down."

He turned and indicated the graphs hanging on the ventilation ducts. The one on the intake side showed the irregularity—straight air being brought in for days and days. But the exhaust index showed the automatic and continuous samplers of incoming and outgoing air had done their work well. Eight hours earlier the needle had jumped far out and left a quavering track in the poison zone. Since that time it had dribbled its way more and more to the center. The latest reading showed the usual exhaust air—just air, slightly warm, slightly polluted, but no worse.

MAJOR MARTIN indicated a trapdoor and one of the men pulled

it open. A minute later they were climbing down a short ladder

into a compartment below. The hatch closed over them, shutting

out the howling banshee of the Martian gale. The two huge

ventilating trunks filled up one half the circular platform, a

tiny elevator being hung between them. The other half of the

circle was occupied by a circular iron staircase that went down

and down. The major led the way down it a few steps, then thumped

the outer wall. It was solid permalite.

"The only access to these mines," he said, "is through these chimneys until the trough comes, and the chimneys have no openings in them except at the top. Another copter load of our operatives will be along in about five minutes to begin at the top and search downward. They will not find anything, but it is routine, starting with a search of the guards up there and then this chimney, inch by inch. We may as well go on down."

They retraced their steps to the upper platform, got into the elevator, and started down. The descent took several minutes, but shortly they emerged into a circular room at the base of the chimney. Overhead great ducts carried the ventilation system, and an outlet immediately above was blowing clean, fresh air. Two corpses lay on the floor, blotched and bloated like the dead guard above. Apparently, from their attitudes, they had died instantly. Major Martin gave them but a glance.

"Necrogen," he said. "It kills at the first whiff."

A corridor took them through the living compartments where the men ate and slept when off shift. The bunks were full of dead. Here and there a body lay slumped in a chair or across a table. It was the same in the office where the heavy safe stood open and empty, its door hanging loosely on warped hinges. It was the same down in the pit, where tough-jawed machines cut the diamond-bearing iron matrix away in chunks. It was the same in the stamp room, and no different in the place where the acid vats were in which the matrix was dissolved away from the imprisoned sparklers. There was no one left alive in the Xerxes. Shortly a careful tally showed that not one of the employees was missing; they were all present—dead. Then the major showed Neville the great iron doors that gave the plant its lower exit onto the iron subsurface of the planet.

"That door opens outward," he said, "and at this moment against a pile of fine sand a thousand feet deep."

"Tunnel?" suggested Neville.

"You don't do much tunneling through diamond-studded steel," replied Major Martin dryly, "but we keep searching for them. There are none. Moreover, even if there were, there could be no practicable outlet. They have yet to invent a mole or any kind of vehicle that can navigate under sand. The only locomotion available on Mars are the crawlers, as we call the little tanks. Copters are reserved for police use only."

Neville glanced at the ventilating duct overhead and at the scattered corpses. The job was obviously done by admitting poison into the air-feed system, but how could the murderer get away, even if he had a gas-proof suit?

"What about the guard at the top of the chimney?" he asked sharply. "Why couldn't they have pulled the job, thrown the loot and other evidence down to an outside confederate, and then turned in the alarm?"

"They could have," admitted the major, "but they didn't. Two of the members of that guard are my own trusted operatives, acting under cover. We had another down here, but we've lost that poor fellow. No, it is an outside job."

Neville thought that over. Then his eye caught a little mound of raw diamonds beside one of the acid vats. They had evidently come out of the processing machine just as the robbery occurred, and had therefore not been picked up by the collectors and added to the other stock in the vault. He was amazed to see that they were of all different colors—ruby-red, emerald-green, water-white, sapphire-blue, moss-green, pink, yellow and pale-blue.

"Do Martian diamonds come like this—all colors out of one hole?"

The major nodded.

"Another tough aspect of the case. If they only produced red ones at one place and white at another, we might hope to trace them after they are stolen. But Martian diamonds are wonderfully uniform in respect to everything but color, and those are invariably mixed as you see them here. It makes it nearly impossible to find the fence."

"Hm-m-m," said Neville, pocketing the handful of sparklers.

WHEN they arrived at the Hannibal they found it completely

uncovered, and were able to land in its lee on the slick hard

surface of the mother planet. The story there was much the same,

except that the gas had not killed, but put to sleep. The only

dead were the tower guards, and they appeared to have been rayed

down from behind.

Neville took the occasion to have a close look at the outside of the mine. He could not rid himself of the suspicion that there must be some way to enter one except at the very top or bottom. He scrutinized especially closely the slender stack that rose twelve hundred feet above him. On its lee side an iron ladder rose all the way to its pinnacle, otherwise the chimney was bare, sand-blasted permalite. Neville set up a telecamera and made careful shots of the chimney all the way up and from every angle.

"I've seen enough," he said at last, picking up a few samples of the Hannibal stones. "This is a job that will take some thinking over."

"I'll say," said Major Martin, sourly.

By nightfall they were back in Ghengiz and at headquarters.

"What do you think?" asked the major desperately. "You have inspected two, and when you've seen one you have seen them all. The technique is identical. Who is doing it, and how?"

"Dunno," smiled Neville, who had slumped back in his chair and was gazing dreamily at the ceiling. "I haven't got that far yet. What I'm trying to dope out is the motive."

"Motive! Why, money, of course."

"Sure. But how much money? Even pirates don't go into wholesale massacre for the sake of a few bushels of diamonds once in a while. And the details of the Hannibal incident prove that the robber doesn't have to kill to get at his loot. It seems to me—"

The phone was buzzing.

"Yes," acknowledged the major wearily. He listened a moment, grunted, then hung up. He turned to Neville.

"The miners at the Cortez and Attila have struck. They are afraid to go on working and demand a police escort to bring them into the labor barracks here at Ghengiz, That makes the sixth mine to shut up out of fear of bandits."

"I'm not surprised," said Neville calmly, "and that gives us our No. 1 suspect. Tell me who stands to gain most by closing all these mines, and you will name the man behind these robberies. He is a clever man and thoroughly unscrupulous. What is his name?"

Major Martin frowned at his desk, considered the question a moment, then said, "Mario Hustings answers the specifications. I have thought of him as a possibility before. But there is absolutely no hookup. Moreover, he is our most dignified, wealthy and powerful citizen. We will have to practically convict him before we even accuse him. He is owner of the Consolidated, which embraces the Wellington, the Custer and the Scipio—"

"I thought you had an antitrust law here," challenged Neville.

"We have. But it was enacted after Hustings built his first three mines. Since then they must be individually owned and operated, or be shut down and revert to the public domain. The only monopoly that Hustings has is the Martian Construction Co., and he has that by virtue of patent rights. He devised the type of building you have seen, and when anyone gets a charter to open a mine it is Hustings' company that does the construction work. After that he has no more to do with it."

"That's interesting," murmured Neville. "One more question. How much have your diamond exports fallen off since the robberies began?"

"Not any. Which doesn't prove a thing. Of course, the sales of Consolidated have risen with the robberies, but so have those of the independents. It has been the custom of the diamond industry from the beginning of time to maintain an even supply so as not to break the price. All the companies have reserves—much of it here in the government vaults. So when one or two mines fade from the picture, the others make up the loss out of stock. You won't get an anywhere along that trail, I'm afraid. Even if you suspected the other companies were acting as fences, you still could not prove the diamonds were stolen unless you catch the thief in the act. Martian diamonds are indistinguishable."

"I'm not so sure of that," said Neville. "On Earth they are all different."

The major talked on, his gloom deepening as he talked. Mars was surrounded by a cordon of fast cruisers, giving absolute assurance that no unauthorized ships landed or left. The only port of entry was Ghengiz, and the most minute searches were made of every ship coming and departing. Major Martin was willing to stake his reputation that not one of the stolen diamonds had been taken away from the planet yet. The outbound cargoes were all from the government-bonded warehouses. The more he talked, the more hopeless he made the case appear. There were no criminals on Mars, or any place for than to hang out. Ghengiz was the only town, and it was well policed. Otherwise there were only the mines.

Neville yawned, got up and stretched.

"I'm going to putter around in the laboratory for a while before I turn in," he said. "By the way, will you have your operatives get me a few diamonds from each of the mines? Make sure they were mined there, too, and were not just in the vault."

"Certainly," agreed the major, and jabbed a button. "I already have them."

THE next activities of Special Operative Billy Neville might

have mystified another man, but Major Martin took them with

patience and a measure of hope. For he knew that Neville was

reputed to be the best trouble-shooter on the force. Neville

spent hours studying the enlarged photos of the mine stack. He

spent other hours sitting before a huge vacuum tube in which he

bombarded diamonds with high-tension current. The results were

not wholly encouraging. Some threw back phosphorescence of an

apricot hue, others of pale-green, red and orange. But, to his

disappointment, not all the sample diamonds from the mines showed

distinguishing phosphorescent colors. After that he sat in the

dark for a while, idly rubbing them with a silk rag.

By morning, though, he was reasonably satisfied. His next request was that sample lots of diamonds be brought to him from the bins of the mines in the bonded warehouse. After he had looked over a few of those he announced his intention of calling on Mr. Hustings.

"What for?" asked the major.

"To size him up, for one thing," replied Neville, casually, "and to jolt him for another. Please have two of your best shadows on the job, for I want him tailed from the time I leave."

The local inspector merely raised his eyebrows, but signified he would comply.

"While I am gone," added Neville, "I would like to have a crawler made ready, with an assortment of pipe wrenches, nipples and connections in it. And a container of harmless gas with a distinctive odor to it. Peppermint oil, say."

"Done," was all the major could say.

THE interview with the diamond magnate was brief. Neville

found him in the offices of his company and was admitted

immediately. The millionaire met him at the door and shook his

hand cordially. Mario Hustings was a fine-looking man for all his

sixty years, well built, bronzed and with a genial smile.

"Well, well," he said, as he pumped the hand. "So you've come to solve our crime wave, eh? I wish you luck, but I fear you will be here quite a while. I am sure you will, unless you are far more competent than our local sleuths."

"On the contrary, Mr. Hustings," said Neville, evenly, "I expect to return to Earth within a very few days. I find the case simpler than I expected. It is already solved. I do not think you will have any more robberies."

"Ah," said Mr. Hustings, dropping the hand. It was a long-drawn "ah" and ended with a rising inflection.

"The culprit is still at large," Neville hastened to add, "but we expect to apprehend him shortly."

"Good work," said Hustings heartily. "That will be a great relief to us all. Cigar?"

"No, thanks. There are a few loose ends to pick up yet and I can't stay."

Neville hurried back to the laboratory and spent another hour hurriedly scanning the dossiers of all of Hustings' employees. By the time he had found what he wanted, the tank was ready. Major Martin chose to accompany him.

"Find me a mine," said Neville, "that is about half submerged."

The rough riding little vehicle lurched off, swaying and plunging in the wind to the steady hissing of the driving sand against its sides. They plowed through lesser dunes, but as they got farther south the dunes became more and more mountainous. At times the tank would climb steeply, only to fall into a side-slide and go slithering down the face of the wave, like a wind-blown ship in the ocean. As the wind rose, they caught fewer and fewer glimpses of the sky through the curtain of driving sand above them. The tank driver made his way by compass and other mysterious instruments on his dash.

Presently it halted, crawled ahead and stopped. At first Neville could see nothing. But in a moment he made out that they were in the lee of a segment of a stack. He could not see the top of it, for it was obscured by the whipping sheets of sand, but he could see a few rungs of the outside ladder leading upward.

"They can't see us, either," he pointed out to the major, meaning the men of the tower guard.

"Now let's rig a safety line and get around on the windward side of this chimney. That is what I am interested in."

The other side was smooth, seamless permalite, despite its continual assault by sand. They had to wait for fully an hour until the growing dune had pushed them thirty feet higher. Then Neville saw what he was looking for—a little projection. It was the stub of a one-inch pipe, sticking out just far enough to admit a cap being screwed on. A helper brought the bag of wrenches and a moment later the cap was off, the connection being made, and the tank of aromatic oil brought up to be hooked on to them.

Neville screwed the last union home, then hunted for the other thing he was looking for. It was only a few feet away and almost invisible, it was camouflaged so perfectly. It was simply a short lever, recessed in the face of the chimney wall. He tripped the valve on the gas container, waited until its contents hissed away, then seized the lever and jerked it down. A small section of the wall slid open, making a doorway just large enough to admit a man clad in an anabrad or a gas-proof suit. He beckoned to Martin to follow and ducked inside. Then he shut the panel quickly so that no more sand would blow in.

Down below the alarm sirens were howling and men were shouting.

"Better get word to them it is a false alarm," suggested Neville. "We don't want to be cut down as burglars."

They stayed but a few minutes, then went out as they had come in. They wanted to get out before the secret door could be buried by sand.

"IT'S as simple as that," Neville remarked on the way back to

base. "This thing has been planned for years. There are several

of those pipe connections and secret doors at different levels.

They were put there when they built the stacks. The pipes lead

into the intake air duct, the door is so closely fitted and so

placed that the most rigid inspection of the interior would

hardly be expected to reveal it. I spotted them on my

enlargements of the plates. They have gone undiscovered from the

outside for the reason that it is impossible to inspect the

weather side of one of these chimneys except as we just did, and

heretofore no one has thought it necessary to do that.

"Hustings' man could simply come here, screw on his poison gas whenever the sand rose to the proper level, go down and rob the place as soon as the gas did its work. Ten minutes later he could make his getaway, unseen and unsuspected."

"Hustings' man, huh?" growled the major. "How are you going to prove that? It is true his company built the chimneys, but that does not necessarily involve him personally."

"It's going to be hard," admitted Neville, "but I think I can do it."

BACK at headquarters they encountered two sheepish

operatives. Shortly after Neville's visit, Hustings had hopped

into a crawler and hurried away to the southward. The I. P. men

trailed him in two other tanks, but he lost them in a sandstorm.

When last seen he was heading somewhat to the westward.

"That would be the Scipio," was the major's guess.

"Absolutely. That is where his poison gas is made," asserted Neville. "Apparently he took my visit seriously."

"How do you know that?" demanded Major Martin.

"His head chemist there formerly worked for Tellurian Chemical. He is a recognized expert on lethal gases. Moreover, the present superintendent of the Scipio was formerly a construction foreman for the Martian Building Co. It is my hunch that all of Hustings' accomplices live and work at the Scipio. I found out plenty this morning when I read their dossiers. We can make the arrest any time now. I am satisfied—"

The alarm bell on the wall began to tap. The phone buzzed.

"Sorry, Neville. But you are dead wrong about Hustings," the major said after he had taken the message. "The Scipio has just been knocked off. Hustings wouldn't kill his own men."

"Oh, wouldn't he?" said Neville grimly.

A moment later the door opened and Hustings himself walked in. His genial manner was gone. It was plain that he was excited and angry.

"A fine lot of policemen we have here!" he roared. "Yesterday you tell me you have broken the robbery ring, yet just now I get word my Scipio Mine has been robbed and all its people murdered. Necrogen again. What about the man you said you were going to take into custody? What are you waiting for?"

"For you to come back," said Neville quietly. "The man is in custody. Put the nippers on him, boys."

The two operatives sprang forward and despite Hustings' roars slapped the irons about his wrists.

"You got away with a lot, Hustings, but it's all over now. Your killing the man who built your trick chimneys for you and the man who made up your poison gases along with the jackals that did the dirty work won't let you out. It merely saves us that many trials and a mass execution. We have enough on you to hang you without their testimony."

"You can't connect me with those chimneys," Hustings yelled, his eyes ablaze and his face purple, "or the gas, either. Suspect and be damned, but what can you prove?"

"Well," drawled Neville, "leaving out of account the train of circumstantial evidence—of which there is a lot, I assure you—and the quite obvious advantage it would be to you to have all the other mines driven out of business, we have the simple fact that you are in possession of all the diamonds stolen from the looted mines. They are all impounded in this very building."

"Pah!" snorted Hustings, struggling with his wristlets. "Martian diamonds do not carry any brand. The phosphorescent test is meaningless here—they all respond the same—"

"So I discovered," said Neville dryly, "or, rather, most do. However, I applied a test you seem to have overlooked. Did you ever hear of triboluminescence? It is astonishing that a man of your cunning should have missed it—"

Hustings was glaring, panting.

"Rub a diamond in the dark with wool or silk and it is likely to give off a dim light. Your Martian gems are most responsive to it. The Hannibal stones, for example, glow pale green, whereas the Custer's are a deep magenta. Every local mine has its characteristic color. What's more to the point, the vaults in the warehouse bear that out. Each mine's output corresponds with the stones it produces. Except yours. In your vault we found not only stones from your mines, but several bushels each from all the robbed mines. But none at all from the unrobbed mines! If you can explain that—and where you have been the last six hours—you have nothing to worry about. Take him away, boys!"

Special Investigator Billy Neville sank into a chair. He was tired, and the ceaseless whine of driving sand was getting on his nerves.

"It's all yours now, major," he said. "Call a cruiser, won't you? I want to see some water for a change—not sand."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.