RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

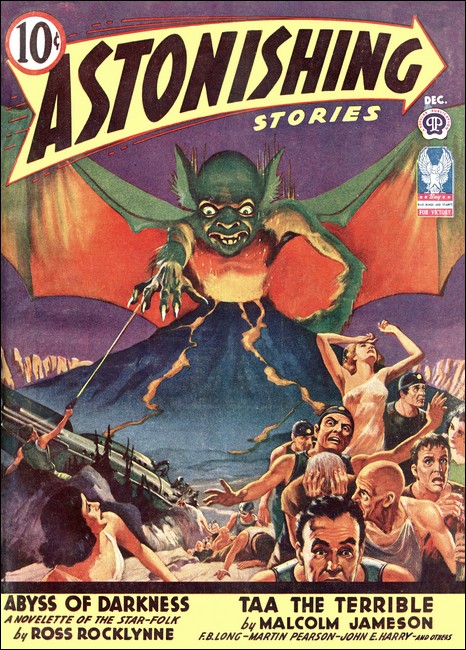

Astonishing Stories, December 1942, with "Taa the Terrible"

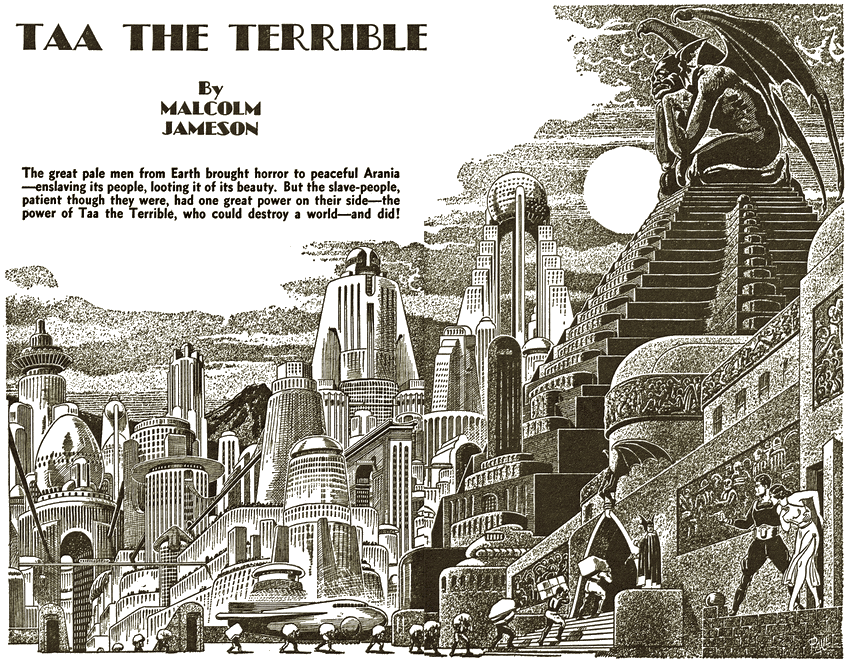

The great pale men from Earth brought horror to peaceful Arania—enslaving its people, looting it of its beauty. But the slave-people, patient though they were, had one great power on their side—the power of Taa the Terrible, who could destroy a world—and did!

ALL the way down from the spaceport Larry Frazer kept telling himself that he had picked exactly the right planet for his vacation. For Arania was the most Earthlike of any in the galaxy and its one big city, Nova Atlantis, was a riot of sub-tropical color and vivid contrasts. He reclined easily in the luxurious litter provided by the hotel where he had booked accommodations, and looked about him while the eight sturdy natives jogged doggedly along bearing him to his destination. The road wound through groves of brightly flowering trees, and here and there he could glimpse a villa half hidden in the greenery. The houses, he observed, were all of rose or jade green or creamy alabaster; everywhere his glance roamed it fell upon new beauties. The only jarring contrast was the presence of the native slaves—beetle-browed, brutish-looking men of a curious olive-green complexion. It was true they wore gorgeous liveries, but Frazer quickly found it made him uncomfortable to look into faces. There was a dull apathy there, despairing resignation that somehow went to the heart.

The scene changed. The houses were closer together, and grew ever closer until they ran into solid blocks. He was in the city now, and the stream of traffic about him became ever thicker. Something new caught his eye, something new and different. A richly lacquered palanquin borne by native lackeys in pale blue silks swung out of a court and began bobbing alongside him, now forging ahead, now dropping to the rear according to the pressure of the traffic. It was what was in the palanquin that snapped Frazer out of his languorous day dreams. The passenger in the companion vehicle was a girl of rare beauty. He was not at all sure whether she had smiled at him or at something beyond him, but of one thing he was very sure—before his stay on Arania was over he would know.

SUDDENLY there was a commotion ahead, and the hurrying rows of

litters began to slow. Then, abruptly, without an order from him

or any word of explanation, Frazer's bearers set his litter down,

crawled out of their harness and fell face down on the pavement,

bumping their foreheads against the stones and uttering curious

little cries. At the same moment the girl's palanquin was

grounded beside him, to the obvious annoyance of its

occupant.

Apparently few of the slave-borne aristocrats liked the behavior of their bearers, for a chorus of growls went up all around. Frazer was curious as to what it was all about, but when he saw the apparent cause of it he was more curious still. For it was not a brass-helmeted gendarme who had halted the traffic, or some passing nobleman of high rank. It was a gaunt and incredibly old patriarch hobbling across the road.

Except for a loincloth of twisted grasses and the white beard and silvery mane that covered his shoulders he wore nothing. The astounding feature of the spectacle was that the man took no notice whatever of the homage being rendered by the kowtowing slaves, or of the growls and epithets hurled at him by the aristocrats... yet he was a native!

"Who is the old galoot in the Father Time rig?" asked Frazer, leaning out and addressing the girl who had been brought to a stop beside him. "And why all the doings in his honor?"

She looked him full in the face for a moment, and then her quick expression of indignant annoyance softened. "Oh, you are a stranger. The man is Ghandar, chief holy man of these superstitious—"

Her words were cut off by an interruption from the rear. A man sprang from another palanquin stopped just behind them and dashed forward angrily. He wore the gold helmet of the highest rank and the scarlet cape of a magistrate. He flourished a quirt in his hand.

"What is this?" he cried harshly, pushing ahead and laying about him with his whip as he passed the grovelling bearers. Then he saw the man Ghandar, who had almost crossed the road and in another second or so would be gone. The angry nobleman gave a howl of rage and started after him, but as he did even the impatient aristocrats gasped anxiously. Apparently the high priest of the Aranians was untouchable—even by the gold- helmeted overlords.

"Oh, don't, Hugh! Please don't," screamed the girl of the palanquin, standing up and wringing her hands. "Remember your promise—"

THE man stopped and turned, and Frazer saw that he wore a

sapphire in his helmet and carried a dagger at his belt,

prerogatives of only the loftiest few. The fellow's dark, thin

face was contorted with anger, but he seemed to sense the tension

about him and abandoned his intention of flogging the holy man.

Instead he marched straight back to the litters, whose bearers

were now getting to their feet and back into their harness. He

gave the girl only a brief, venomous glance and muttered, "I'll

talk to you later in private, Nelda. Who is this man?" He jerked

his shoulder contemptuously toward Frazer. Nelda shrugged without

answering. The nobleman whirled on Frazer.

"Who are you?" he demanded, savagely, glaring down at him with furious eyes.

"Larry Frazer, if it's any of your business. I don't think it is." Frazer's own steely gaze was returning the hostile stare with compound interest. He did not like the evil face above him, or the snarl into which the thick lips were curled. For two cents—

"Everything that happens on Arania is my business," snapped the gold hat. "Especially the conduct of fools. On Arania one does not accost ladies of rank on the highways. Do I make myself clear?"

"When Larry Frazer addresses a lady and she answers him politely," said Frazer, with exasperating calmness, "that is their affair. Do I make myself clear?"

"You impudent—" began the man called Hugh, cutting down viciously with his quirt. But the whip never landed. Frazer's idle right arm lashed upward like a battering ram, and his hard fist caught the other on the chin. The gold helmet flew off and clattered to the ground, while its wearer stumbled backward groping dazedly at his battered jaw.

"I am afraid, Mr. Frazer," said the girl Nelda, her violet eyes wide with alarm, "that you have made a deadly enemy. Hugh Zero is a powerful man."

"Oh, I've survived other deadly enemies," grinned Frazer, examining his scuffed knuckles. "I'll manage."

"Arania," she remarked, "is run differently from most planets."

Traffic was moving again, and the discomfited Hugh Zero had vanished. Slaves were picking up their litters and starting forward, while the passengers stared at the serene Frazer with expressions of respect. The pampered son of the viceroy was no favorite on Arania, but it was unthinkable that anyone would be so rash as to strike him in a public place. Some of the departing aristocrats shook their heads soberly. Trouble was bound to ensue.

The palanquin moved away and Frazer caught sight of a tiny flutter of a farewell wave of the hand as it went around a corner.

By the time Frazer's litter got there, it was out of sight. So he lay back and let his trudging slaves take him on to his hotel.

THE week that followed was blissfully peaceful. Though Frazer

noted that many of his fellow guests at the resort on the flank

of Holy Hill took care to avoid him, he heard no more of the

incident. He learned only that Zero was an ardent wooer of Nelda

Sutherland—so far without encouragement.

But Frazer went about his sightseeing with a light heart. After all, wasn't he himself a wearer of the silver helmet of the first patrician order, embellished with a ruby? Being an Earthly rank, it was hardly inferior to the gold of a provincial. He was surprised to find that Arania's surface was mostly water. Only the large island on which Nova Atlantis stood was habitable for, though many chains of volcanic peaks rose above the sea, those mountains were in almost continuous eruption. Men dared not approach within hundreds of miles of them, and the tidal waves they set up made navigation a great hazard.

But the land about Atlantis was a paradise, though legend had it that four prior Earth colonies had been wiped out by cataclysms so vast that there had been no survivors to tell the tale. The natives, who somehow seemed to live through them, all said mysteriously that the invaders had been extinguished by the act of the fiery god Taa, their protector. Taa would come again, they threatened, and obliterate the newest oppressors.

Frazer listened to these fairy tales with mild interest. He had come to Arania for rest, not to delve into mythology. The natives could believe in their dread god Taa for all he cared.

He could hear nightly the throb of the great drums beating in the swamps beyond the mountain and occasionally saw the glow of fires they built upon their altars, but it was not a thing that concerned him in any way. He had sojourned on many far planets and had seen all manner of queer religions. Whatever the cult of Taa signified, it was the affair of the Aranians, not his.

Holy Hill, he learned a little later, was a mocking title bestowed by Earthmen upon the natives' sacred mountain. In earlier time it had been the abode of high priests, and only the devout were permitted to ascend it to witness the ceremonies periodically held in the great temple on the summit. But the vandal Earth colonists had changed all that. The forested slopes of the beautiful mountain, overlooking as they did the spires and domes of Nova Atlantis on the plain, were tempting sites for country villas, gambling houses and other resorts of pleasure such as the one Frazer lived in. The newcomers invaded the mountain, an act of vile desecration in the natives' eyes, and built their palaces.

In time they found the chantings of the priests and the pounding of the drums annoying, and forbade the further use of the temple above. Now it stood, a crumbling ruin of antiquity, its once perpetual altar fires dead, moss growing upon its sacred stones.

ONE day Frazer climbed to the summit and looked at it. The

structure was not unlike a teocalli of the Aztecs, except

that it was of conical shape instead of being pyramidal. He

worked his way up the flights of ancient steps until he came to

the sacrificial platform at the top. It was acres big, but the

scale was dwarfed, for in the middle of it was a colossal figure

of Taa, the God of Fire, of Creation, Destruction and Vengeance.

In common with many images of pagan gods, this one was hideous.

It was seated, a demoniac figure of greenish stone, but its

diabolical eyes were closed and the enormous bat wings folded

behind its shoulders. The hands lay idly in the lap, but the lax

curved talons held a monstrous brazen offering bowl. Frazer stood

gazing on the terrible idol for many long minutes, and was hardly

aware that the sun was down and the daylight fading into dusk.

And then an almost imperceptible swish behind him told him he was

not alone. He wheeled—and found himself facing the man

Ghandar, high priest of Taa.

"You have come to learn—not scoff like the others," said the priest in measured tones. Frazer saw then that the ancient could be erect and majestic in bearing when he chose. This expression was that of a man accustomed to command. "Ghandar knows all things. Though his back was to it, he knows that the wretch Hugh Zero would have laid his whip upon him. He knows, too, that you smote him as he deserved. Ghandar does not forget. Ghandar will help."

"I fear you did not get the story altogether straight," laughed Frazer. "I walloped Zero for purely personal reasons. As for needing help, I thank you, but I can handle that whelp."

Ghandar shook his head gravely. The stars were out then, and starlight on Arania is as brilliant as full moonlight on Earth.

"You do not know the tremendous peril you are in. It is twofold. Tomorrow workmen come to demolish this place—the mighty temple of Taa. It is the last possible defilement, and the most intolerable. Taa sleeps now, but he will awake, and when Taa awakes he is terrible. After he has thundered, there will be no more Atlantis or the accursed breed of Earthmen who have ground us down, spat upon us, and made us miserable slaves. And only Taa, through me, can save you."

"With all due respect to Taa," said Frazer, "his fight is not my fight. It may be as you say, but in a few more days I go back to Earth—"

"No!" thundered Ghandar. "You intend to, but you will not. At this very hour soldiers are on the way to your quarters to pick you up. They hope you will resist, for then they can kill you at once. Failing that, they will do so on the trip back to prison, saying that you tried to escape. It is the viceroy's order. Not ten minutes ago I was informed of it."

"How do you know these things?" asked Frazer quickly. He had expected a reprimand for brawling in the streets, possibly, but it was a serious matter to put one of the silver badge under arrest.

"Ghandar knows everything. He sees and hears through the eyes and ears of every slave on this planet. This afternoon the elder Zero died. The son, Hugh, became viceroy. He is an impetuous, foolish youth, and full of blind hate. He hates you, he hates me and my people, he hates even mighty Taa. His folly will bring his own destruction, and shortly. But his wickedness will bring yours first. Come, my son, and let my people hide you. Only in our hidden caverns can you be safe from the madman in power."

"Thanks, old man," said Frazer, marveling that a man of such obvious personal power should be so steeped in superstition that he actually believed the stuff he handed out to his people. "But I can't do it. A Frazer of the silver badge does not run away from things. Frazers fight."

"You will run away within an hour," prophesied Ghandar solemnly. "There is another trying to save you, and that one will prevail."

Before Frazer could answer the holy man was gone, stepping into a shadow and vanishing without a sound. It was puzzling. Just what did all this talk about Taa mean, anyhow? Taa, of course, was a myth, but did the threat of his coming mean that a slave rebellion was imminent? Perhaps. Such things were often masked that way. Frazer turned away, putting the colossal stone idol behind him, and slowly descended the long stairs.

FRAZER paused at the foot of the staircase to drink in the night scene. Across the valley to the north lay the shimmering bed of iridescent lights that was the city of Nova Atlantis. To the right and left lay the dark swamps where countless slaves toiled; below twinkled the lights of the many villas that dotted the flanks of Holy Hill. But above, the pure stars shone brilliantly..

Frazer sought the dark patch that would take him back to his room. He had gone but a few paces when suddenly he went tense as a cloaked figure darted out into his path. It was a woman. She spoke.

"Larry! I came to warn you. I am Nelda, the girl who—"

"I remember," he said.

"Shh," she whispered. "Death waits for you down the hill. Come with me."

"But—"

She gripped him by the arms. "The soldiers are already in your apartment. Others are ambushed along the path. They will kill you—I know, for this morning I quarreled with Hugh. He taunted me with the details of what he planned to do with you. I hurried here—"

"But wait," he objected. "I don't like to do things this way. I'm not guilty of any crimes. Even if I were, there is no reason why you should go out on a limb to shield me."

She clutched him more tightly. "Larry Frazer, I have lived the empty, silly life of this degenerate planet too long. I am fed up on fops. I have seen Hugh lash them across the face time and time again when he was in one of his tantrums. Not one ever struck back; the worms cringe, or try to laugh it off. I never knew the meaning of the word man, Larry, until the other day. Now do you see?"

"I am beginning to," he said, slowly, drawing her to him. But she pushed him away.

"Not now," she cried, "they may get impatient and come on up. Quickly, follow me!"

She broke into a run and he followed. She led the way around the sprawling base of the temple to where a small sky-cycle was parked. Its lights were out, but she fumbled at the door and instantly had it open. Then he was inside and she was twiddling with the starter.

"Toss your silver helmet behind the seat," she ordered. "Put on the bronze one you find there, and the brown jacket of a plantation foreman. I am taking you to an island—it belongs to a friend of mine. Stay there—play the part of a planter. I'll communicate with you later."

He complied silently. It was a new and incredible situation for him, and he was at a loss what to do. But he was content to let Fate run its course.

IT WAS but a moment until they were well clear of the sacred

mountain and zooming out over a misty valley. As Frazer's eyes

became better adjusted to the gloom, he could see that they were

soaring over what looked to be a vast inland sea, ringed by

tumultuous mountain ranges, studded with circular islands of

uniform size and equal spacing.

On some of them could be seen the flickering fires of altars where natives clustered, exhorting their demoniac god. Frazer could make out faintly the throbbing boom of ceremonial drums. And then he knew his flight was drawing to its close, for Nelda was pointing the nose down toward one of the islets. In seconds more the machine grounded gently in the semi-dark, and she nodded to him to get out.

"You will find the foreman's hut over there," she said, pointing. "The slaves live in grass tree-houses, but there are probably none here. This is one of the things you will have to watch; they steal away at nightfall to go to the orgies in their temples. Tomorrow your supervisor will come over to instruct you. Tell him nothing about it and follow his orders. Good-by."

She slammed the door and soared instantly up into the night. He stood there for a time, a little dazed by the swiftness of developments of the last hour.

It was almost incredible that he—Larry Frazer, well-to- do, well-connected, guilty of nothing more than a simple act of self-defense—should be standing ankle deep in the soft, yielding, damp soil of a dark island. And in the disguise of a common foreman—the lowest of all the ranks of freemen. He shook his head perplexedly. His vacation had turned out strangely.

He walked across the muddy field to the small grove that stood in the center of the island. The hut she indicated was white and stood out clearly in the starlight. As he neared it he saw the basket houses of the natives, clinging to the towering trees like cocoons to a bush. Rope ladders dangled from them, and from that he judged that her surmise was correct—the inhabitants had gone away.

He went on into his own small house and made a light. The place was plain and without any comforts, but all the essentials for solitary living were there. Food and the means of cooking it, water and a cot.

Frazer doused the light and lay down.

HE WAS up at dawn. The supervisor was already there, standing

at the foot of his bed and looking at him. The man was tall and

thin and burned by the sun to a rich walnut tan. He wore a sour,

woe-begone expression that told clearly that he was a man who

looked on the worst side of everything, and disliked what he

saw.

"Where are your workers?" he demanded, skipping over the matter of mutual introductions. .

"I don't know," said Frazer, quite truthfully. "There were none here when I arrived."

"That fellow Bjorks left before you got here, I suppose," growled the super. "It would be like him. Naturally they'd run away the moment they were left alone. They spent the night bumping their heads and caterwauling, no doubt, in one of the temples in the hills. Oh, they'll be back—they always come back. But they will have no life in them. They'll be fagged out and groggy. You'll have to drive them with the lash today."

There was a commotion outside, a sound of splashing and guttural voices. Both men went outside the hut. Scores of natives were climbing the edge of the island, wet from their long swim, but the moment they saw the Earthmen they stopped their chatter, spread out and hastily went to work plucking the weeds that grew in clumps all over the isle.

"This harvest must be in within ten days," said the super, curtly. "Then you will prepare the island for another planting. I want results, not excuses."

He strode away, climbed into a battered old skycycle and was off. Frazer watched him climb a little way, then dive onto another of the islands to inspect it and give more orders. Frazer strolled over to where the constantly arriving natives were turning to at their work. He had only a nebulous idea of what his duties were to be, for Nelda had not told him, or the vinegar- faced supervisor. But it appeared to be something in the way of agriculture. He hoped to learn more about it from the miserable creatures he was supposed to drive.

By nightfall he was able to deduce some facts from his exploration of the islet. He understood then the reason for the uniformity of it with the others, and the mathematical exactness of their placing. They were artificial. They were rimmed by low retaining walls made of heavy vines woven about stakes driven into the lake bottom. The rich soil behind the basket-like barriers must have been dredged up from the waters beyond.

The permanent nucleus of the island was the central grove which housed the workers and was ringed by a garden sufficient to grow the stuffs which they ate. All else was given over to the money crop. He plucked a bundle of the weeds and sniffed them. Then he knew what they were—lollen, the curse of the universe, from whose juices and oils a multitude of insidious and deadly drugs could be brewed. On Earth those extracts were sometimes sold illegally at thousands of dollars the ounce. Small wonder the aristocrats of Arania bore themselves haughtily! Their collective wealth must be enormous enough to buy themselves immunity for outrageous offenses.

Frazer would not have employed the wicked-looking lash that hung in his hut under any circumstances, but it turned out that there was no occasion for using it. The slaves worked steadily and without rest, going about their task with the same stolid apathy he had observed in the better treated domestic slaves of the city. When dark fell they had piled up an astonishing heap of the dirty weeds, neatly baled and ready for shipment to the refineries.

Frazer marveled at the smooth precision with which they went from one step to the next without a word of direction. He supposed that was because they had never done anything else.

The dour supervisor dropped in again three days later. He wanted to know how the crop was coming.

"It's in, ready to go," said Frazer, pointing to the mountain of smelly bales. The super grunted, exhibited neither pleasure nor displeasure, and then went off.

His parting words were, "Be ready to plant in two weeks!"

FRAZER had no idea what that meant, but he asked no questions.

He was relying on the automatic behavior of the slaves. In the

morning, he found out more about the growing of lollen.

His gang had turned to at a new occupation. They were stripping

the island of its topsoil and dumping it in the lake. They would

scoop the dirt up in their hands and dump it into baskets. Then

they would wade far out into the lake—which was hardly more

than breast deep—and drop it there. On the way back they

would come by another way, where they would dive repeatedly,

bringing up handfuls of muck from the lake bottom to pack into

their baskets. This they brought ashore to use as replacement for

the worn-out soil they had dumped. Apparently the lake waters

restored the vital elements that the greedy lollen weeds

sucked out of the ground.

Frazer watched the operation with steadily mounting disgust for Aranian agricultural methods. The bottom ooze stank to high heaven, and it was all that he could do to refrain from retching whenever the breeze wafted the smell of it his way. Indeed, the slaves themselves seemed not to have got used to it, for at times one or more of them would be seized with nausea and lie miserably for a time in the vile mud. Frazer saw that time was being lost, but uttered not a word, though he knew that a proper Aranian foreman would have driven the men back to work with his cruel lash. Not one of the glistening bodies toiling in the foul lake but was striped with the scars of old whippings.

Frazer noticed another thing about his gang. It appeared to have its own sub-foreman who gave directions so unobtrusively that it took Frazer several days to notice it being done. The man was a native, of course, and a slave. But on closer scrutiny Frazer saw that his face showed far more intelligence than the common run. His bearing, despite the sordid labor he did, was that of a free man—yet his back also bore the indelible marks of the whip. Frazer's mouth set in a grim line as he looked on the angry scars.

What fools these Aranian slave drivers are to treat willing men so, he thought, bitterly. If they let these workers alone they'd accomplish a lot more!

In that, however, Larry Frazer was not altogether correct. He didn't know that at midnight every night the quiet native strawboss met in whispered conference with a mysterious messenger who would emerge dripping from the water, talk briefly, then swim off again.

That visitor was the messenger of Ghandar, bringing instructions to the local men to carry out faithfully Frazer's orders and to guard him well.

Frazer learned about that in the middle of the tenth night after his arrival—and then the silent sub-foreman told him of it in person. He scratched at the hut's door, and asked to come in. It was important—and with him was the messenger, still wet and glistening from his long swim and panting violently.

"I am the priest Prang Ben," said the slave-leader. "I was assigned by the holy Ghandar to be your guardian. He sends word that what he feared has happened—Zero has learned of your whereabouts and is on the way here to seize you!"

It was too late—

The hum of a descending skycycle was growing louder outside. It plumped down close to the hut, splashing the soft new island mud against the window of the house. Larry Frazer was outside at once. He saw that the stubby nose of the craft flaunted the insignia of the viceroy.

"NELDA!"

"Oh, Larry, I got here in time!"

The momentary, rapturous embrace came about as naturally as if they had known each other for years.

"I beat him to it," she explained breathlessly. "A house servant told me your supervisor sold you out. Hugh has gone mad, I think—in his fury at you and in his persecution of the natives. I ran to the palace. This car was parked at the door, waiting. I jumped in."

"Where will we go?" frowned Frazer. Tomorrow the air would be filled with police craft; there would be no safety anywhere. And now, he knew, Nelda would be hunted equally with him.

"I lead the way, master," said Prang

Ben, appearing suddenly at his elbow. "It is always safe in the caverns of Taa, not only from the accursed Earthmen who afflict us, but the great god himself. There is no other place to go, for Taa comes soon—and Taa is terrible. Men who hear him speak die; the sight of men who see him is seared; his touch is extinction. Come—I show."

"There must be something to that," said Nelda, softly, touching Larry on the arm. "The natives of my household have been saying those very words for days, and lately they have been stealing away. The natives are vanishing everywhere, but where they go to nobody knows."

"Very well," said Frazer. "Let's go."

A moment later they shot upward and over an adjacent island. A police car swooped past, then dipped in respectful salute. It evidently took it for granted the viceroy was in his car, bearing his prisoner away. At Prang Ben's direction, Nelda piloted them on a little farther, then abruptly changed the course. They flew past Holy Hill, but miles to the south, and on to the great barren range that formed the west barrier wall of the island. Harsh mountains, those, unclothed by forests and rising steeply from the barren plain. Their ocean faces were precipitous cliffs against which the turbulent sea forever beat. The luxury-loving aristocrats of Nova Atlantis seldom visited the region. The priest pointed out a flat area in a cleft between two peaks.

"Land there," he said. "It is close by the brink of the cliff overhanging the ocean. We three can tip this car over it so that when day comes there will be no trace of where we landed."

The work was quickly done. Then Prang Ben performed a peculiar ululation from-the depths of his throat.

"Open," he commanded, "in the name of Taa, whose servant demands it!"

Frazer, who was staring at the flat granite mountain wall that faced him, was amazed to see it appear to crack open. Then a square slab of stone swung inward, revealing a black hole. Prang Ben at once sprang into it, calling upon the others to follow. After they had passed, the door swung to without a sound. For an instant all was black as the tomb. Then dull red glowing lights came on, spots of evenly spaced ruddy lights to show the way.

They walked along thousands of feet of tunnel, hewn out of the living rock. The digging of it must have taken millions of hours of labor. They descended spiral ramps to great depths, until Frazer knew they must be well down in the bowels of the mountain. Then they came to a door in the side of the passage.

THE sight that met their gaze was startling. It was like

looking into the maw of hell. For the doorway pierced the wall of

a vast cavern—so vast that its farther walls or roof could

not be seen. It was filled with fire and smoke. The three stood

still just within the threshold until their eyes became

accustomed to the smoky glare. Then they knew they were in the

great secret temple that age-old rumor credited the natives with

maintaining underground. Thousands of them lay prostrated on the

floor, their faces down, but with their heads toward a giant

figure of the devil-god Taa that towered near the far end of the

hall.

Much of the flame came from rows of braziers ringing the worshipping multitude, but the most vivid light sprang from the massive offering bowl which the colossus held between his hands. That seemed to be filled with molten rock or metal, which leaped upward from time to time, filling the air with spouts of sparkling brilliance and causing reverberations that shook the cavern's massive walls. Frazer thought he could discern the triple cylinders of huge electrodes which furnished the intense heat, but the idol was far away and the intervening space too smoky for him to be certain of that. But whatever priest of ancient days had rigged the temple had been a mechanical genius.

For though the idol appeared to be a duplicate of the one atop the sacred mountain—being depicted with closed eyes and folded wings—every time the cauldron boiled up and spattered its face with the flaming ejected matter, the statue's eyes would roll open and fix themselves greedily on the seething incandescent rock below, and its wings would outspread and flutter feverishly, as if in ecstasy.

Frazer was positive that the effect was achieved mechanically, for each successive movement was exactly like the last—like the ones of a walking doll. It was evident, though, that the natives did not share his skepticism. At every such demonstration, they would howl in unison.

A priest began to chant.

"Oh, great is Taa, the Maker and Destroyer, the Avenger who chastens the conqueror but spares his own. The time nears, O Taa. Prepare thy wrath; for the need of it is great and it must not be kept leashed longer. Now you sleep. Soon we sleep, too, the long sleep. Then must you awake, as often before in the past. For it it foretold that when Taa walks abroad in the land men must sleep or die; and that when Taa sleeps, man may awake and live. Rise, O Taa, and scourge our enemies!"

The coruscating fires died down and the bubbling cauldron subsided. The chanting ceased abruptly; the ceremony was at an end. The natives picked themselves up off the floor and trooped out through portals at the side. Prang Ben indicated to Frazer and Nelda that they were to follow, and led the way. Outside the great nave of the temple, roomy corridors ranged deep into the mountain. The throng was fast melting away through side doors that gave entrance to subsidiary caverns.

"Those are the fast freezing rooms," explained the priest. "My people now go into the long sleep. We do that out of terror of Taa, for when he roams the land in wrath no thing that can feel, see or hear can survive. Only in these catacombs is it possible to bear his thunders and live. We call it the Sleep of Ten Thousand Years, though no one knows how long the time really is."

Farther on they came upon other natives trundling carts on which were stacked the bodies of those already "asleep." Frazer stopped one to examine the condition of the bodies upon it. The figures were inert and without perceptible heartbeat or pulse, nor did they breathe. They were cold to the touch, and it was clear that by some means their metabolic rate had been reduced to nothing. Then Frazer noticed that in the caves to the right and left similar bodies were being slung in hammock-like bags to be left dangling in long rows like so many bats.

"You, too, will join these," said Prang Ben, pointing. "There is no other way."

"YOU have erred, Prang Ben, in I bringing these Earthmen into

the mountain," said the high priest when the two were before him.

Now he sat on a throne of sorts, and though he was still the'

emaciated patriarch of unguessable age, he looked most commanding

in his robes of flame-colored silks. There was a gleam of anger

in his eyes as he stared at Frazer and the girl.

"They would have been killed, Holiness," said Prang Ben.

Ghandar shrugged, "They must die in any event. Had you left them to that chance, they might perhaps have stolen a spaceship and escaped the planet. It is too late for that now. Already Taa stirs in his bed; in a few hours he will be awake. We cannot subject these to the Sleep like our own people. In other eras our fathers tried to save selected Earthlings from the anger of Taa—but the freezing kills them always. We want no corpses within the mountain to pollute the air during the long sleep. Take them back to the upper portal—and turn them out!"

"Hey!" yelled Frazer, angrily. "What's all this mumbo-jumbo about? Why did you butt into my affairs in the first place if it was only to give me the grand run-around?"

"Patience, son," said Ghandar, gravely. "You do not understand. I had a very real and worthy purpose in trying to protect you from the man Zero. I was hopeful that you would be the one to overthrow the present tyranny, and thus avert the coming of Taa. But I learned too late that you were merely a transient tourist, without power. Then events began to move so swiftly that I could wait no longer. Nothing can save you or our oppressors now—for I have already summoned Taa. Feel!"

A deep rumbling drowned out all sound for a moment as the mountain shuddered.

"An earthquake," cried Nelda, paling.

"But the beginning," said Ghandar. "Since there is still a little time left and you feel aggrieved at your treatment, let me tell you something of the history of this planet and our race. Then you will understand better about Taa, and the many lost Atlantises.

"My race, I am sorry to have to say, is a primitive one as compared to those of your own planet. Yet many thousands of years ago we established a civilization. We were happy in it, even if your own early explorers called it barbaric. They laughed at our fire-adoring religion, ridiculed the mighty Taa. They were followed by others who were better armed than we, greedy and cunning. They reduced us to slavery, a state no better than that of beasts. Our priests were patient and long suffering, for it is no light matter to call in Taa. But call him they did and Taa came and smote the invaders. Your people never knew what happened to that first Atlantis—or to the second or the third, or fourth. But I, high priest of Taa, know. They were destroyed just as the Nova Atlantis of today is about to be—in the identical manner and for the same reason.

"Had we hope any longer that the tyranny would be relaxed, we would have waited. But it became a race for survival. Zero was having our temples pulled down, and in the past two days has massacred many of our most faithful priests. I could not wait; I summoned my people to the mountain. Today you will not find one still outside. The gendarmes of Zero are combing the hills and forests looking for them, but they will not find any. They are all here, being put to sleep. Then, after the last one of us is safely in his hammock, Taa will awake!"

THE discourse was not enlightening—it was too laden with

mystic phrases. Taa the Terrible! Terrible twaddle!

Frazer could not deal with that which had no meaning. Let them put him out where he could handle his own affairs, out where things were tangible and not wrapped in superstitious disguises.

Then a messenger came and spoke rapidly for a couple of minutes with Ghandar.

Not even Nelda could make out the meaning of the message, for no Earthman ever unraveled the intricacies of the Aranian tongue. In that weird language no sound need necessarily ever be employed twice in the same sense; a word meant what it did only by taking into consideration the tone of voice, the pitch context, subject matter, accompanying gestures and other factors. But Frazer noticed that when the talking was concluded that there was a look of grim satisfaction on Ghandar's face.

"You have a bare chance of escaping," said the holy man, turning to Frazer and Nelda. "I learn that the man Zero, who is worried about the abrupt disappearance of my race, is preparing a sneak getaway. He has moved the seat of government to the top of our sacred mountain, known to you as Holy Hill, and has further desecrated the temple of Taa there by setting a space ship upon its broken altar. Soldiers guard the flanks of the hill, so that if there is an uprising, they can hold the people off long enough for him to escape into space. If you could steal that ship you could turn the tables on him!"

"If!" laughed Frazer scornfully. "Holy Hill is more than a hundred miles from here and we have neither arms nor transportation—"

"You shall have both," said Ghandar, and called Prang Ben to him. "Take them to Taa's Mount by the seat tunnel. Do it swiftly—for there is little time left before the fire god awakes!"

THEY went down by an elevator. It was a crude elevator, operated by hand and opposed by counterweights. But it served, for they must have descended several thousands of feet. At the bottom they emerged into a lower cavern that was dank and moldy and smelled of the sea. It was dark down there, but Prang Ben produced torches and handed them to them. Then they saw that it was a tunnel rather than a cavern they were in—one of nearly circular cross-section, perhaps fifty feet in diameter, and apparently endless in the land direction. The seaward end was closed by a vast metallic sheet, around the edges of which water seeped.

Prang Ben found a small wheeled vehicle and rolled it out. It had pedals like a bicycle and could be driven by foot by two riders in tandem.

"This is the ocean gate," said the priest, waving toward the iron door. "In a while water will be let in. I cannot go with you—it would be impossible to come back. But at the other end of the tunnel is Mount Taa, where you will find another elevator such as this. It will take you into the substructure of the temple on the summit, above where Taa still sleeps. Go swiftly, for the time grows ever shorter."

Prang Ben was gone. Frazer and Nelda exchanged glances.

"Spooky place, this," commented Frazer, looking about. "Must be a good way below sea level. Wonder what they dug it out for? It's much too large for an ordinary subterranean passage. And I wonder what else they are going to spring on us."

"Let's get going," she said. "If there's more, we'll find it out."

The little machine was speedier than they thought it would be from its appearance, and as the tunnel had a slight downward slope, they soon found themselves racing along at a goodly clip. Indeed, they took their feet off the pedals and let it coast, for it was making all of fifty miles an hour.

That enabled Frazer to pay less attention to handling the locomotion and more to study of the curious tunnel. Every ten miles or so he found that it was fitted with what appeared to be flap valves, sheets of ribbed metal so shaped and hinged as to be forced tightly shut and held there by any strong current of air or water flowing toward the sea, but of such a nature as not to impede motion inward.

He noted also that pockets of salt appeared here and there, showing that there had been times when sea water had flowed in abundance—and been dried up. That was a feature that was hard to understand, for there was no dearth of water anywhere on Atlantis, and he could not see for what possible purpose this deep subterranean salt water flume could have been built.

As they proceeded, the dampness of the walls disappeared. No longer was the atmosphere here cool and dank. It first turned warm and humid, then to a hot dry heat that felt as if the tunnel air was fresh out of a furnace. Soon it became so oppressive that Frazer began to have serious misgivings about going on. If it became much hotter, he felt they would surely perish. But just as he was applying the brakes to check their headlong speed, he found other reasons for bringing the queer little scooter car to a halt. They apparently were about to arrive at their destination.

He managed to bring it to a stop at exactly the right spot, for if the car had gone on another fifty yards it would have plunged straight down into incredible depths. For at this point the tunnel abruptly changed course—from the horizontal to the vertical. It angled sharply down toward the interior of the planet, and then narrowed into a funnel just before it turned sheer downward. A metal catwalk led out over the pit and to a small door.

"This must be the way out," said Frazer, abandoning the car where it was, and leading Nelda over the flimsy bridge. They went through the door, after glimpsing what appeared to be monstrous machines in the depths below, and on the other side of it they came upon a surprising sight.

THE room they were in was circular, and at one side was the

open elevator shaft, as Prang Ben had foretold. But the feature

of the place was a painting on the rough stone wall of the demon-

god Taa, this time depicted as wide awake and bathed in fiery

flame. His taloned claws were outstretched and threatening, his

bat-wings were outspread as if ready for flight, and there was an

expression of fiendish glee on the demoniac countenance. The most

curious exhibit of the room, however, was the sign that was

inscribed below the picture. It was in standard Earth language,

not in the cabalistic characters of Aranian.

It said, "Here sleeps Taa the Terrible. Behold him, but heed well that ye wake him not." There was an arrow pointing to a pedestal topped by a curious lens. Frazer went to it and put his eye to it.

He gasped, for after the first puzzled instant he recognized what it was he was looking at. The lens revealed a metallic tube of unguessable length and material, going straight down into the bowels of the planet. A mile or more below it glowed a ruby red; below that there was the dazzling white of rock hot enough to be incandescent.

Frazer could not figure out by what optical means the view was obtained, but there it was—the fiery magma of Arania, kept solid only by the tremendous pressure of the cooler rocks that overlay it. And then suddenly, Frazer understood everything.

"Come," he said hurriedly, grasping Nelda's hand and fairly dragging her to the elevator. "Taa is real. I have seen him, and he is terrible. We have no time—"

He jerked frantically at the elevator ropes, and she helped him. At length they came to the top of the shaft, which they found to be in a tiny chamber in the upper portion of the great cone that supported the Temple of Taa. A small winding stair took them up under the altar itself, and they found themselves in a place where light came through chinks in the stones. Day must have broken over Atlantis. They approached the lighted crevices cautiously and looked out. They knew then exactly where they were, for the substructure of the altar was supported by stonework richly ornamented with carved symbolic figures. It was through the eyeholes of a pair of mythological monsters that they did their peeping.

Not thirty feet away lay a small, smart spaceship—the two-seater variety, but capable of sustained interplanetary flight. Zero was standing beside its portal, and a stream of soldiers was passing in, each burdened with a bag or chest of valuables. If and when Zero made his get-away, he would be well- heeled!

"The thieving scoundrel," exclaimed Nelda, recognizing the chest. "He must have looted the Central Bank and the Viceregal Treasury!"

"Shh," hissed Frazer. "We've got to find a way to get out there."

IN A moment they found it—a panel of stone so set that

it could be slid back from the inside. By the time they were out,

the last of the soldiers had left the ship and was starting back

down the hill. Zero stood at the edge of the platform watching

them descend.

Frazer said quietly, "Turn around, Zero."

Zero whirled about to see the muzzle of Frazer's blaster trained unswervingly on him.

"Toss your guns away," ordered Frazer crisply.

He watched the man throw the weapons over the parapet. Then he holstered his own.

"Zero," said Frazer, advancing slowly upon him, "in a very few minutes you are going to die—but not at my hands. There are those who have more grievances against you than I—Ghandar, and the followers of Taa. You have scoffed at Taa and slaughtered his priests and violated his temples. You did wrong. Taa is very real, and he is on his way—but he will deal with you in his own fashion!"

"Hop in, let's go," shouted Frazer, and he was pushing Nelda into the ship ahead of him. He sprang into the control seat and jabbed the starting stud. The machine roared upward amid the pinging of bullets fired at them by the soldiery, aroused by Zero's frantic yells for help.

Frazer took just one downward look before he set his course. The altar platform had dwindled to a small rectangle, and at the foot of the temple structure lay the toppled image of Taa. Its wings had been broken off, its nose chipped, and it had been otherwise mutilated. To Frazer it was a grim threat.

He stood westward, and took care to be high. In a few seconds they were over the hollowed-out mountain range in which the race of Arania now were swinging in their Sleep of Ten Thousand Years.

It was a short wait. Presently he saw the sign he was looking for. He showed it excitedly to Nelda and began to explain. First there appeared an eddy in the ocean, not far offshore. It developed into a whirlpool, expanding into an ever-widening maelstrom. Frazer tried to visualize what was happening as those millions of tons of cool sea water tumbled through the intake gate and rushed through the sea tunnel they had just traversed. He could see the torrent pushing the valves open all the way, until it came to the end of the tube under the sacred mountain. And there it would plunge down, be seized by Ghandar's engines—probably injectors of some sort—and forced on to the terrible depths where Taa, the hot, lay asleep. There would be steam—vast clouds of it at fantastic pressure.

It would find itself penned in by millions of tons of rock and try to go back the way it came—but the valvular doors and the inrushing water would check that. Then it would have no choice but to—

"LOOK!" yelled Frazer, bringing the ship around and heading it

warily back toward Nova Atlantis. Nelda looked, and her eyes

widened in awe and her mouth dropped open. Holy Hill exploded,

sending a mighty column of mingled steam and fire miles into the

air. Boulders and chunks of the shattered mountain were flung

about like pebbles, raining on the city and the sky-port. Frazer

beheld one such stone, large as a fair-sized house, fall squarely

on the Earth cruiser due to soar that day with a passenger list

of wealthy tourists. The cruiser was smashed like an

eggshell.

Other things were happening. The ground surface was undulating in waves, opening here and there in deep crevasses. The towers of Atlantis were toppling; crowds of screaming Earthmen could be seen scrambling for the nearby hills and what they hoped was safety.

"Great heavens!" whispered Nelda as she looked on. At that moment fiery fissures showed in the side of the now glowing mountain. Then the mountain split and the sparkling lava flowed out and down, engulfing all that lay below it.

There was another explosion, and this time a plume of poisonous green gas was flung upward, fattening into a thick and threatening column. When it attained the altitude of several miles, the wild volcanic engendered winds spread it out across the sky like a cape. Added puffs from the fiery crater below added body to the central column. It seemed to swell out, to take the horrid form of a demoniac figure.

The grotesque apparition seemed to spread batlike wings as if to cover the whole island; its taloned hands clutched feverishly at the torrid air; the creature even appeared to have features—a wicked, fanged, malevolent face, gloating fiercely over the destruction it was wreaking. It grew and grew, now wavering, now more clearly distinct. Frazer's skin crawled.

"It is marvelous what faith, coupled with ingenuity, can do," he muttered, setting the automatic pilot to take over on an Earthbound course. Until that moment Nelda had not looked back at the mountain, but was staring over the side down at the frenzied mobs fleeing from the now blazing city. It was a spectacle sufficient to upset the strongest set of nerves. And then she took one backward glance.

"Taa!" she screamed, and fainted.

"Yes, Taa," said Frazer, softly, taking her into his arms. "Taa the Terrible!"