RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Astounding Science Fiction, February 1944, with "The Anarch"

The ideal of totalitarianism is the elimination of all individual initiative. Suppose that ideal were somehow attained. With no one, anywhere, wanting to revolt—

IT was a death paper.

Medical inspector Garrison shifted uneasily in his chair and stared at it. It was all wrong. It was on pale-green paper for one thing, and it had been altered. Down near the bottom where there was a place for a date and a signature, the word "Discharged" had been xxx'd out and "Died" supplied.

"Look here, Arna," he said to his scribe, "this won't do. This... er... ah... Leona McWhisney was admitted only last week... neomalitis, the diagnosis says... treated with sulfazeoproponyl, and due for discharge tomorrow. Treater Shubrick has scratched out the discharged and put in 'died.' That's absurd. People just don't die of neomal."

"She did," replied Arna primly. "Here's the morgue- master's receipt."

Garrison took it and frowned. Not only did she give him the morgue slip, but the report of the autopsy as well. The McWhisney woman's dead arteries had been found to be crawling with neomal bugs—and nothing else. It was a hard fact to face, and he did not want to face it. He couldn't face it. It was Earth-shaking, outrageous, impossible. It could not be reconciled with anything he knew. It put him in an awful hole.

"But look," he insisted, "we can't use the green form. That's the one for case histories of non-fatal diseases, and the Code classifies—"

"I know," she snapped, "neomalitis is a Category N malady, a mild, easily controlled undulant fever. I looked it up. Article 849 of the Code says Category N must be reported on the green form. That is what I have done."

"That is not right," he growled, glaring at the offending sheet of paper. "If the woman died, it has to be reported on an authorized death certificate. Anyhow, we are not allowed to change any form. Not ever. It means a lot of demerits for both of us."

She sniffed. She knew that as well as he. She had been struggling with the problem for two hours, and her desk was littered with volumes of the bulky Medical Instructions—those bits of the Grand Code by which they lived and which prescribed their every act.

"All right," she said coldly. "You select the right form and I'll fill it out."

Medical Inspector Garrison started to make an appropriate reply, then thought better of it. He was in no ordinary dilemma, and was beginning to know it. It was more a being caught between two opposing sets of antlers bristling with scores of prickly points. The death, as far as that went, of the obscure Leona McWhisney meant nothing to a seasoned doctor. People were dying at Sanitar all the time. But they were dying in approved ways that could be reported on approved forms. Her departure from the normal played hob with the whole Autarchian set-up. Garrison groaned aloud, for he was, until that moment, a thoroughly indoctrinated, obedient, unthinking cog in the vast bureaucracy that was Autarchia. Not once in the thirty years of his life until then had the Code failed him. He had never doubted for an instant that that wonderful document was the omniscient, infallible, unquestionable guide to human behavior. It was unthinkable that he could doubt it now. And yet—

Yet Leona McWhisney was dead, and it was his duty to sign the death papers. By doing it he would certify that her case had been handled in accordance with the Code. There lay the rub. It had been, he was sure, for he knew the superb organization of Sanitar and especially the wards under his control, and it could not have been otherwise. There was no one who would have dreamed of departing from the sacred instructions by an iota. The problem lay, therefore, on his own desk—how to close the case and still keep out of the Monitorial Courts.

The dead woman's disease, as was every other, was curable, and must be recorded on the green. So decreed the Code. But she had died inexplicably despite the Code, and having died, she must be given a death certificate. But there were only three forms of those, for there were only three possible ways for an Autarchian to die. The most common—reportable on the gray form—was by euthanasia after recommendation of a board of gerocomists, and approved by the Bureau of Population Control. Elderly citizens beyond further salvage, or those in excess of the Master Plan were disposed of in this fashion. Then there was the yellow form that was employed when violent accidents occurred. Even the all- wise framers of the Code had not known how to re-capitate or re- embowel a citizen thus torn apart. Last of all there was provided the scarlet form for the use of the executioner at Penal House after the monitors had finished dealing with dissenters. That one was on the road to obsolescence, for in recent generations there had been few who refused to abide by the Code, or scoffed at it. The trait of rebelliousness had been pretty well bred out of the race.

Still there must have been some taint of it left, for even Garrison could not bring himself to accept meekly his predicament. If people could die of neomalitis, he thought, the Code should have foreseen it and provided for its proper reporting. Apparently, they could, and apparently it had not. There was something smelly somewhere.

"When you make up your mind about that," broke in Arna, sweetly, "here are a couple of other questions they want rulings on. The treater on Ward 44-B says that he has twelve patients with neomal that should have been up and out today. The prognosis says so. He wants to know if he keeps on shooting sulfazeoproponyl. He has given all the therapeuticon prescribed."

"No, of course not. Better run 'em through the Diagnostat again and take a fresh start."

He watched unhappily as she made a note of it. It was an unsatisfactory answer and he knew it. There was no more authority for rediagnosing a case than for prolonging treatments after it was supposed to be cured. But it seemed to him that as long as they continued to be sick something should be done.

"And the admission desk wants to know," she went on, "what about quotas? According to vital statistics Sanitar is supposed to get only three hundred cases of neomal a quarter. We've admitted that many in the last ten days. Shall they keep on taking 'em in, or turn 'em away?"

"Oh, we can't turn 'em away," said Garrison weakly. He was right, too. The Code specifically forbade it. But the Code had also set the admission rate for Sanitar, based on the known incidence of various diseases, and it could not be much exceeded for the excellent reason that the hospital's capacity and personnel were fixed by the Master Plan.

"Yes, sir," said the exasperating scribe, and jotted down his answer.

He glanced worriedly at the McWhisney papers on his desk. He could not sign them as they were. He had to make sure.

"I'm going to make an inspection," he announced, and stalked out of the room.

Medical Inspector Garrison was what the Autarchian Code had

made him. It was no fault of his that he had been born into a

perfect, well-ordered world where every detail was planned and

there was no room for independent thought or initiative. He was

the natural result of his training. His very first memories had

to do with the Code, and from then on he had never encountered

anything else. At the age of five the Psychometrists had come and

taken him from his crèche and tested him with glittering

instruments that gave off dazzling multicolored lights. That was

when his first psychogram was made and his Cerebral Index

established. That was what set him on the road to doctorhood, and

made him an interne in a Sanitar at the age of fifteen. By that

time he had mastered the Junior Social Code and most of the

Medical, and along with it he learned those portions of the Penal

Code that applied, plus such other fragments as would be of use.

No man alive, with the possible exception of the Autarch himself,

could know the whole of the Grand Code, for it covered the entire

field of human knowledge. Garrison only knew that whatever there

was to be done, the manner of doing it was to be found in some

part of the Code. And he also knew that there was no other

way of doing it. That is, unless he wanted to invite the

attentions of the monitors. And it was common knowledge that no

one who went to Penal House was ever seen again. The Autarchs did

not encourage nonconformity.

It was with this background and the puzzling conflicts of the morning uppermost in his mind that he strode along Sanitar's endless corridors. Hitherto the Code had never failed him. Now he was lost in a maze of contradictory instructions, not one of which he dared question or refuse to abide by. Heretical ideas kept flitting through his troubled brain. Long dormant traits began to stir and come to life within him. Curiosity was one. Somehow it had survived in his heritage of genes. He wanted to know—wanted desperately to know—why Leona McWhisney had died, when the book said she couldn't? What was happening in neomalitis? Why was it fast becoming more prevalent? What was making it more virulent? Why didn't the sulfa drug still cure it as it had always done before?

He arrived at the admission desk and looked about him. Everything was exactly as it should be. There the applicants were being logged and turned over to the attendants to be stripped and scrubbed prior to their full examination. Their dossiers were being sent for.

He picked up one at random and examined it. It was a magnificent document, many inches thick. In it was the record of its owner's medical history from birth, complete with the X-rays and body chemistry findings taken at every successive annual examination. There were curves of growth and change, and accounts of incidental illnesses. Everything the most exacting doctor could want was there.

Garrison laid it aside and went on. He passed by the various examining rooms and laboratories with little more than a glance in. All were carrying out their functions perfectly. In one place blood and spinal fluid were being analyzed in another, men sat in rows having their electro-cardiograms recorded. A group of psychomeds were probing neural currents to find out a patient's attitude toward his own condition, and elsewhere the newcomers lay on cots having their current basal metabolism established. In the biological lab observers were scrutinizing bacteria cultures and dissecting tissue. Everywhere there were checkers, going over the other fellow's work.

The young inspector knew there could be no slip-up in the collection of basic data. A quick turn through a couple of wards revealed things going well there also, so far as the medication was concerned. He even consulted with the chief pharmaceutical inspector to make sure the drugs used were up to standard. Perfection reigned in exact accordance with the Code. The only jarring note was that the wards were becoming crowded. There were ever more sick, and the sick ones were not recovering as they should. In 45-B Garrison was stunned to learn that two more neomals had just died, and that several others were about to. It took the McWhisney affair out of the freak class. It denoted a trend. It also ended the hope of overlooking that first case.

There could be but one other factor. The data were correct, and the treatment given as prescribed. The only other room for error was in the diagnosis, so Garrison went to the elevator bank in the great central tower. No one had ever questioned a Diagnostat before, but he meant to now. He punched the button for the express car to the sub-basement.

The only word to apply to the cavern where the ponderous

machines purred and ticked was—vast. The great monsters stood in

long rows—the Sorensons down one side of the room, and the

Klingmasters the other. Those massive calculators were the only

examples in all Autarchia where two distinct models of machines

were doing the work of one. In every other case the framers of

the Code had selected the best type and discarded all the others.

But the Sorenson and Klingmaster Diagnostats arrived at their

findings through radically different channels. Since they were

equally efficient both were kept, to be used in opposing pairs,

one to check the other.

Garrison offered the foreman of the room the dossier of Leona McWhisney.

"Hm-m-m," mused the foreman, glancing at the record. "This has already been through—done on Sorenson 39, cross-checked by Kling 55. Neomalitis, Type III, sub-type C. What's wrong?"

"She's dead," said Garrison.

The foreman shrugged.

"All we do here is diagnose 'em. If they kick the bucket, it's somebody else's fault. You'd better check up on your treaters, or on the dope they use."

"I have. It must be the diagnosis. It can't be anything else."

"Oh, can't it?" countered the Diagnostat foreman. "Did you know they lost ten pneumonia cases over in Bronchial wing last week? Did you hear about the guy up in Psychopathic? A mild neurosis was all we had on the fellow here. Well, he ran amok last night—cut the throats of four fellow patients and then jumped out the window. There is something screwy going on, all right, but it's not down here."

"I want a recheck on this," insisted Garrison.

"But she's dead," objected the foreman. Then he saw the glitter in Garrison's eye. "O.K.," he mumbled, and reached for the book.

Garrison looked on in silence while the monster did its work. The data was fed in by various means through various orifices. Queerly-punched cards bore part of the information—such items as could be expressed by figures, as weight, pulse, blood-pressure, respiration, and so on. The curves of the cardio- and encephalograms were grabbed by tiny steel fingers and drawn into the maw of the machine. It clucked loudly as the X-ray plates were slid into a slot. The amplitude and frequency of the undulant fever readings were given it. When all was in the foreman closed one switch and opened another.

"This is a different Sorenson, and hooked up with a different Kling," he said. "Both were overhauled last night, but I'll bet you get the same answer as you got before."

"That's what I want to know," said the inspector.

The machine purred and groaned. Then it set up a clicking and stopped momentarily. Up to that point it had ignored the symptoms, Garrison knew, and was engaged in breaking down and analyzing the basic factors. Now it reintegrated them and was ready for its first pronouncement. A window lit up with glowing letters:

Constitution fair.

Physical Resistance Factor: 88.803.

Psychic Factor: 61.005.

Composite Factor: 72.666.

The light died, and a confirmatory card dropped out. The

purring was resumed. Garrison considered the figures. They were

about right. The woman had been of excellent general physique,

though a trifle depressed in spirits. She should have thrown off

any disease with reasonable ease.

Now a red light was burning, indicating the Diagnostat was taking into account the developments due to infection. After a bit a gong sounded, and the machine growled to a full stop. Another card dropped out:

Neomalitis, Type III, sub-type C.

Garrison looked at it, then walked across the hall to the Klingmaster. It was slower to reach its conclusion, but when it did it was identical.

"All right." said the foreman, "that's that. Now let's do the rest."

He poked one of the cards into a smaller machine—a therapeuticon, with prognosticon attachment. It took the contraption less than a minute to cough out the answer:

Indication:

6 g. sulfazeopronyl every four hours for

eight days.

Tepid baths daily; abundant rest.

Prognosis:

Discharge in nine days, ten hours.

Garrison looked crestfallen. He thought he had an out. Now he

was where he started. He shook his head dismally.

"She's dead," he said, "and it's only a week."

"An autopsy ought to settle it for you," suggested the foreman.

"It has," said the miserable inspector. "It said neomalitis."

And he walked away, leaving an indignant Diagnostat man glaring after him.

Garrison signed the pale-green paper reluctantly. There seemed

to be nothing else to do. Then he glanced at the chronodial and

saw that it was nearly seventeen, time for the day-watch to go

off duty. At that moment there was a shrill warning buzz and the

omnivox lit up. A fanfare of trumpets warned that something big

and unusual was about to come through. He got to his feet and

stood at attention. A uniformed figure appeared on the

screen.

"By order of his supremacy, the Autarch," he proclaimed in a deep, sonorous voice. "Effective immediately, those provisions of the Social and Penal Code requiring attendance during Renovation Hour at Social Halls are suspended for officials of C.I. one- thirty or better. Such officers may attend or not, as they choose—"

Garrison blinked. He had never heard the word "choose" before and had but the faintest idea of what it might mean. More obscure ones were to follow.

"If they so elect, they may stay within their own quarters or visit other officers of similar rank as theirs. Restrictions as to topics of conversation are lifted during this period. Officers will not be required to discuss assigned cultural subjects, but may talk freely on any topic they prefer. Monitors will make note of this alteration in the Codes.

"The order has been published. Carry on."

The light failed, and with it the figure on the screen.

Garrison continued to stand for about a minute, entirely at sea

as to what the communication he had just heard meant. Such words

as "elect," "choose," and "prefer" had long since become obsolete,

if not actually forbidden. The concept of choice was wholly

absent under the autocracy. It never occurred to one that there

could be such a thing—it was inconsistent with orderly life. One

simply obeyed the Code, which always said "you shall." To think

of anything different was rank heresy and treason, and subject to

the severest penalties. Garrison puzzled over the order a moment

and gave it up. No doubt there would be further clarification

later. Perhaps the Propag lecturer of the evening would have a

word to say about it. The order would be carried out of course,

but to Garrison's well-disciplined mind it had the bad fault of

ambiguity.

The ringing of the corridor gongs snapped his attention away from it. It was time to assemble for supper. He closed his desk, slipped on his tunic, and stepped out into the hall. There he faced to the left as the others were doing, and waited for the whistles of the monitors.

The signal was sounded, and the tramp of feet began. Garrison stepped along as he always had done, but with the difference that on this afternoon there was turmoil in his mind. Having to sign that altered document had done something to him. It hurt, and hurt deep. It is difficult for anyone not imbued with bureaucratic tradition to comprehend the poignancy of his anguish. He had been forced by the rules themselves to break a rule. For the first time in his existence he was compelled to question the all-wisdom of the Code. The Code had declared neomal curable; he had seen the exception. And while he was still quivering with mortification at that discovery, the pronouncement of the Autarch had come. He did not know what it meant precisely, but it signified one more thing clearly. The Autarch had seen fit to modify a Code. The implication was inescapable. The Codes were not infallible. If one provision could be altered, so could all the rest. It was food for anxious thought.

The marching men came to a downward ramp and took it. On the level below Garrison had to mark time while the officers of that floor cleared the ramp below. He took the occasion to look them over critically—something he had never thought of doing before. Like himself not a few of them but also had had inexplicable deaths in their jurisdictions, and every one of them had heard the message just received from the Autarch. But not one of them showed the flush of suppressed excitement that he was awkwardly aware warmed his own cheeks. If there was any who shared his newborn doubts, none exhibited it.

They marched like so many automatons. Nowhere was there a sign of perplexity or frustration. Instead, he now observed that all were sunk in the same dull apathy that he had noticed in the incoming patients. It was not the apathy of weariness or despair, but a sodden, negative something—sheer indifference. They did not care. There was no motive to care. Their personalities were not involved, if a citizen of Autarchia could be said to have such a thing as a personality. They were required to put in so much time, and to obey certain inflexible rules. So long as they did that they had no responsibility as to the outcome. Now they had done their stint and were on their way to replenish the energies they had expended by the ingestion of necessary food. The evening to follow would be but an extension of the day—planned, orderly, meaningless.

At times the worm turns in a curious way. In that split second the spirit of some long dead ancestor stirred within Garrison and woke him up. The breath-taking realization came to him that he was an individual—he, Philip Garrison.

Medical Inspector of the B wards of Sanitar. He was different somehow from those others. They were clods, puppets. What did it matter what their Cerebral Indexes were, so long as they could read and punch the proper buttons? Anyone above the moronic level could do the same. No thought or judgment was demanded to conform to the Code. Small wonder they swung along like men stupefied.

Garrison could not avoid a slight shudder. The trend of his thoughts were highly treasonable. Then he reminded himself that the monitors possessed only hidden mikes and scanners; they were not telepathic. They could not read the heretical notions striving to make themselves dominant in his brain. He calmed himself, and tried to change his line of thought, for he knew that madness lay that way. He endeavored to recall what a Propag had said at a recent lecture about the "dangers inherent in independent thought" and the hideous predictions of how disruptive such ungoverned activity could be.

The arrival at the dining hall put a temporary end to that. He handed his ration card to the Dietitian of the Watch. She glanced at it, scribbled the prescription, and dropped it into the messenger tube. That was all that was required. He marched on with the living robots about him. Shortly he would get food that would no doubt be good for him—sustaining, and containing what he needed, neither more nor less. It would have the calories required, and the vitamins, and the minerals. It might be tasteless, it might be unpalatable, it was almost sure to be mostly synthetic. But it was what his metabolometer called for, and with that there was no arguing.

Garrison ate in sullen silence. So did the others, but with a difference. Theirs was the stolid silence of oxen at a trough. Even the director and the ranking members of his staff on their raised dais ate in the same manner. It was a thing they had to do—it was part of the routine, joyless but necessary. Now Garrison was beginning to understand why people were falling ill with such ease, and being ill, failed to rally. Life was empty. They did not care, nor did their physicians care. It was that spirit of don't-give-a-care that was pushing Autarchia to the brink of ruin. "I'm going to do something about this," muttered Garrison to himself, "and I'll start by finding out why neomal kills."

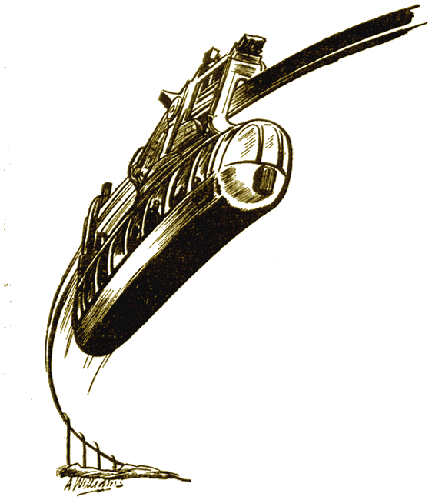

He went out with the crowd when the "dismiss" signal was given. He took the elevator to the tower where the gyrocar was waiting. Then he sat in the seat his position rated—one by a window, and hung on as the car teetered drunkenly as it cleared the slip. After that it straightened up and went whizzing along its elevated monorail, careening around curves on its nightly trip to Dorm.

The sun was on the point of setting, but everywhere there was full light. It was rolling country, covered with fields, and the horizon was broken only by the occasional bulk of a plant where alcohol or plastics were made from the products of the soil. The intervening fields were planted in corn and tomatoes, bulk crops that could be grown more profitably outdoors than in the hydropones. An army of low C.I. laborers was still at work, spraying the lush weeds under the watchful supervision of the agronomists who sat perched on lofty chairs set up among the tasseled rows.

Now that Garrison's eyes were opened, he saw what he had looked at daily but had never comprehended before. It was that the laborers' work was futile. The cornfields and the acres of tomatoes were like his wards in Sanitar. Uncontrollable and malignant weeds and blights had moved in and were taking them. As the car rushed over a hilltop where the ground rose up almost to it, he could see the details better. Where once the fruit hung bright and red and round, it was now sparse, discolored and misshapen. Plump ears of corn were replaced by scrawny spindles riddled with wormholes. Garrison could glimpse them now and then despite the weeds which in many places towered even above the tall corn.

The sight added to his glumness. It had not always been that way. Only a few years before the fields had been clean and sparkling—good reddish soil topped with orderly rows of the desired crop plants and nothing else. Insecticide sprays and selected chemical soil treatment used to work. Lately they did not seem to. Why? They had successfully done so for two hundred years. What was bringing about the change? Was the Agricultural Code inadequate, too?

The car swerved and swept across the highway. A pile of grim gray buildings flashed by. That was one of the many structures known as Penal Houses. To Garrison's new awareness it took on a change of significance. It was another symptom of what was wrong with Autarchia. Designed to hold ten thousand unhappy rebels awaiting execution, today it stood empty. Seven generations of systematic extermination of dissenters had done its work. The breed was now extinct. No one thought of, let alone dared, dissent these days. The very concept of nonconformity was extinct. Garrison knew of it only because of the warnings of the Propags and the presence of the watchful monitors. Yet the prisons still stood. They were useless anachronisms now, complete with large garrisons of monitors waiting boredly for more grist for their mills. But they could not be abolished because they, too, were part of the Master Plan. What was must always be.

Garrison turned away from the prison in disgust. It would be better, he thought, if the idle monitors were put to work in the fields tearing out the weeds by hand. Then they would be at something productive.

The car swirled on. Suddenly, but briefly, the panorama

underwent a change. For about a mile there stretched a field that

was uncontaminated like the rest. It looked as all of them used

to look. Then the car left it and was over another planted with

the same crop, but as weed-choked as the earlier ones. The

contrast of the one well-kept field with the others was

startling.

Garrison craned his neck to look back. As he did he became aware that the officer sitting behind him was watching the act intently. He was an old man and wore the distinguishing marks of a high ranking psychomed. It was that that made Garrison uneasy, for many of the senior psychomeds seemed to possess the uncanny knack of reading people's minds.

In the state of agitation he was in he preferred not to be under one's scrutiny.

"Rather different, eh?" queried the older man, with a quizzical smile. "Why, I wonder?"

"Different soil, probably," ventured Garrison, feeling some answer was expected.

"Hardly," remarked the psychiatrist. "They took such differences into account when they drew up the Master Plan. All these fields are assigned to the same tillage."

"I'm only a medic," hedged Garrison, "I wouldn't know."

"For the very reason that we are medics," pursued the other, "it might pay us to know. Below us are fields that have been successfully farmed for centuries. Now the pests refuse to be kept at bay. They are conquering except in that one field that seems to interest you. It would indicate, I think, that one Agronomist knows something the others do not. That fact is worthy of our consideration."

"Why?" asked Garrison stupidly. He knew it was stupid, but the conversation was taking a perilous turn. This psychomed was probing dangerously near to his heretical inner thoughts. Garrison wanted to mask them.

"The analogy between vegetable blight and human disease ought to be apparent to anyone," shrugged the elder doctor. "We study both and find remedies. Then, in the course of time, one or the other or both get out of control. Haven't you found it so?"

"A woman died in one of my wards last night," hesitated Garrison, "if that is what you mean. She should not have, so far as I can see. But we did our duty under the Code—"

The psychomed glanced cautiously about. The other passengers dozed sluggishly in their seats. The noise of the car precluded eavesdropping.

"Our duty is to save lives, my friend," he said in a low tone. "In that the truly excellent Code is our best guide. But there is coming a time, and soon, when it must be changed—"

"Yes, yes, perhaps," said Garrison, flurried, half frozen with alarm. Those were fearful words, and a lifetime of listening to Propags had set his reflexes. It was not a light matter to change their patterns. "If such a time should come, no doubt the Autarch will give consideration to it."

"The Autarch is neither doctor nor agronomist nor any one of the hundreds of other kinds of specialists it takes to operate a world like ours. He may sense impending peril, but how will he know how—"

"Sir," said Garrison stiffly, scared through and through, "your words border on treason. I refuse to listen. Have a care, or you will find yourself in trouble."

The old man gave a contemptuous snort.

"Trouble? Listen, boy. I am inspector-general for all the Sanitars in this hemisphere. You know of several unaccountable deaths; I know of thousands. You have seen a handful of stricken fields; I have seen abandoned wastes stretching hundreds of miles. It adds up to one dire result—pestilence and famine. Not yet, but soon. If you think the monitors are to be feared, think on that pair of scourges."

Garrison kept silent. He was afraid still in spite of himself, but he wanted to hear more.

"As for myself, nothing matters," continued the psychomed. "I chose to speak to you because you turned back for a second look at the one well managed field. It showed me that regimentation had not made a clod of you altogether. There are not many of us like that, so I broke the ice. Tomorrow I appear before a Disposal Board. The gerocomists say my heart is beyond aiding and my course is run." He grinned. "And having a bad heart I am immune from torture. Euthanasia or standard execution—it's all one to me."

"I'm sorry, sir," said Garrison.

The gyrocar was slowing for the approach to Dorm.

"You needn't be," growled the old doctor, taking in the other occupants of the car in an all-inclusive sweep of the arm. "Be sorry for those dumb inert creatures. And by the way, if you care to pursue the subject further, the name of the agronomist in charge of the field you liked is Clevering."

The car reeled to a stop. Garrison scrambled to his feet and

crossed the spidery bridge that gave access to the high tower of

Dorm.

Beneath were the huge public rooms, the baths and gymnasiums and the libraries of the Code. Down there were kept the individuals' records, and also where the vast social hall was. The rooms and dormitories were in the starlike wings.

Garrison took the elevator to his floor, and walked along the

corridor of his section. The door of the cubicle he called home

was open, as all doors had to be when the room occupant was

absent. He went in and lay down on the narrow bunk for the

prescribed period of rest. From it he surveyed his habitation

with some curiosity, never having thought to do so before.

There were the plain plastic walls, dimly luminous, and the Spartan cot he lay on. There was a chair on which he hung his clothes at night. During the night an attendant would come and replace them with others. He had no need for any but the authorized costume of the day, and it was always provided. There was a small washbowl with a shelf and mirror above it, beside which was posted his individual hygiene instructions—the hours of rising and going to bed, the hour and nature of the bath he was to take, and such details. On a small table lay a copy of the Social Code. That completed the furnishings.

Ordinary Garrison spent the rest period relaxed and with a blank mind. Today he could not. He kept turning over in his mind the problems that seemed to be growing more complex hourly. There was the death of Leona McWhisney, the enigmatic edict of the Autarch, the provocative remarks of the psychiatric inspector, and the mystery of the one uncontaminated farm. Now he had to decide also what he was going to do about the Social Hour. The daily event was always boring, as was most of the well-ordered life he led, but it was a way to while away the time until the hour set for sleeping. He wondered how one went about visiting another in his room, and if he did visit, what they would talk about. And that caused him to open an eye and wonder where was the scanner-mike that kept watch on his room, and whether it was alive all the time, or only now and then.

Habit is strong. He was already sitting up on the edge of the bunk when the stand-by buzzers sounded. That meant five minutes until Social Hour began. He was already tired of his cell and wanting to move. He heard doors outside being opened and the shuffle of feet. The others were on their way. He hesitated, then got up and went out, too. There was not a closed door in the hall. The man opposite him had just come out—a master electrician in charge of the X-ray machines.

"You are going as usual?" asked Garrison.

"Where else is there to go?" answered the fellow.

"We could stay here and talk," suggested Garrison.

"About what?" he asked curtly, and turned down the hall.

The harried glance he gave the walls and ceilings as he did was the clue to his behavior. Garrison instantly read it aright. The Autarch's edict of the afternoon stated that certain regulations were "suspended." There was nothing in the way of assurance that the free conversations allowed would not be listened to and recorded by the monitors. Garrison frowned. Could the Autarch's seeming generosity be a ruse to entrap the unwary? Small wonder the fellow had ducked. For his part Garrison realized he had just had a narrow escape. He meant fully to discuss the McWhisney death and other things with anyone who would listen.

Garrison went on to the Social Hall. The evening proved to be, if possible, duller than usual. Garrison found the other officials ranged in chairs before the lecture platform waiting stolidly for the Propag to begin. None had so much as delayed his coming. Garrison sat down at his customary place. The Propag was coming on the stage.

"It has come to my ears," he began in the sing-song voice affected by the members of his profession, "that a few of you are troubled. In hours of weakness it is human to falter, and there may be some so debased as even to doubt our wonderful Code in the dark moments. That is evil. The Code is all-wise. Believe in it, follow it, and trouble not. All will be well. Let us, my friends, go back and remember our first lessons.

"In the beginning there was chaos. All the world was divided into many nations, speaking different languages, having different customs, and struggling one with another—"

Garrison did not have to listen. The famous "Basic Lecture" had been dinned into his ears at yearly intervals all his life. Once it meant something, now it was an empty piece of ritual. Men sat through it unhearing, for they knew its words by heart.

It told of the Bloody Century—the Twentieth—and of its devastating wars. Those were the bitter conflicts between Imperialists and Republicans, Totalitarianism and Democracy, and the varicolored races. Then would come the story of the infant leagues and unions of nations, and the bickerings among them for top power. Afterwards there were fierce revolts in certain quarters. The world before The Beginning was a world of strife and murder and destruction. It was a horrid world.

"Yes, horrid!" the Propag would scream at that point. "An insane world. A world where there were many opinions about the simplest matters. Men differed, and because they differed they fought. It was under the sage Harlking the Great—the Autarch of the Fourth Coalition—that the Grand Code came into being. He perceived clearly that the world, though not perfect, was good enough if men were only content. So he convoked an assembly of the thousand wisest men of the age. These were the men we now call the trainers, for their task was to sift the world's store of wisdom and select the best for inclusion in the Code. It took forty years for them to complete their colossal work, but when it was done the Autarch pronounced it good. That was Gemmerer the Wise, for Harlking did not live to see his glorious idea come to fruition.

"Gemmerer promulgated the Grand Code, and in doing so forbade that it ever be altered. He foresaw that there would still be impatient men, or dreamers who might try vainly to better things. Man in primitive societies is hopelessly inventive. He is never content with things as are. This was an admirable trait in the formative days of civilization, but in a highly integrated world community is harbors the germ of warfare. The introduction of a new thing, is always a challenge to the old, and the partisans of the old invariably fight back. There must be no more war. Therefore there must be no new thing. Stand men, and repeat the creed of our fathers!"

Sheeplike the audience stood. The Propag led off, and the mumbled chorus of responses followed.

"The Code given us is good!"

"It must not be altered."

"It is the quintessence of the wisdom of the race!"

"It must not be questioned."

"It must be obeyed forevermore."

"Amen."

The rumbling echoes of the whispered responses died, and the

men dropped back into their seats. The Propag treated them with

his professional glare for one solemn moment. Then he partially

dropped the cloak of solemnity.

"Is there anyone present," he asked, still stern, "who... ah, prefers to talk about a topic other than the one we have been studying?"

Several men shifted uneasily in their seats, but no one answered.

"Very well," said the Propag, "we will break up into the usual groups. Group directors please take charge."

There was a rustling as the men found their way to the places where they were to be treated to cultural enlightenment. Garrison joined his proper group dejectedly. He cared less than ever for the plump, curly-haired young man who was his renovation director. That worthy looked his small flock over and saw that they were all present.

"Last night," he chirruped with a false heartiness that made Garrison want to smack him, "we were discussing the complementary effect of strong colors when placed in juxtaposition. Now, if we take a vivid orange, say, and put it alongside an intense green—"

Garrison heard it out, bored stiff. Real problems were stewing inside his head, and the froth he was compelled to listen to angered him. Otherwise it was simply dreary. But eventually it came to an end, and the Social Hour broke up. Garrison caught up with a departing agronomist, and asked him where he could find Clevering.

"Clevering? I think he's sick. He collapsed in the field today. As I was coming in I saw a Sanitar ambulance going in the gate.

"Thanks," said Garrison, and tramped down to his cubicle, and to bed.

Nine more neomals died in Ward 44-B that night, and in the

morning there were no discharges. But waiting at the admission

doors were hundreds of new cases—too many to be accommodated

under the quota. Garrison noted with a wry sort of satisfaction

that the admitting doctors were also struggling with an insoluble

problem. There were others besides, as he found out when he

reached his office. Treater Henderson was awaiting him there with

a sheaf of new diagnoses.

"What am I supposed to do with these?" he asked, plaintively, shoving them into Garrison's hands. Garrison took the topmost card and stared at it.

Diagnosis: Neomalitis, Type $#!..etaoinshrdlu..sputsputsput.

Treatment: Sulfazeoproproproproppr-popopop..nyl!

Prognosis: ?????????

He scowled and grabbed up an intercommunicator. In a moment he

had the foreman of the Diagnostat room on the wire.

"Have your machines gone crazy?" he snapped. "They stutter. They give us gibberish."

"Can't help it," came back the answering voice. "We tried machine after machine. They all do it. And our tests conclusively show—"

Garrison flipped off the connection. He was up a blind alley there and knew it. He turned to the treater.

"Keep on giving 'em the standard sulfa treatment."

After the treater left Garrison sat down weakly and wiped the sweat from his brow. So far he was within the Code, for sulfa drugs were indicated for all cases of neomal, regardless of type. But intuition told him that hereafter it would do no good. The stark truth was that the neomal bug had bred itself into a new type—a strain far hardier than the old, and more malignant. What he had to contend with was a bacillus that was practically immune to sulfazeoproponyl. It was, therefore, causing an utterly new disease, one not contemplated by the august framers. And, unless something was done quickly, a decimating plague would shortly be sweeping the world.

But what? The Code prescribed only the sulfa drug in such and such quantities, and the penalties incurred for administering any other were cruel. Garrison stared miserably at the stack of diagnosis slips. For once he felt a sense of personal responsibility to those sufferers down in the wards. He felt like a murderer. Then his eye lit on a name atop a card. The name was, "Henry Clevering, Agronomist 1st Class."

He lost no time in getting down to the ward.

The wards of Sanitar were not wards in the old sense, but groupings of rooms, and Garrison found his man in the fourth one on the left. The moment he saw him he knew his hours were numbered, for the chart showed the oscillations of the fever hitting ever new highs with a shortening of the period between. Already the ever vigilant monitors had set up a portable mike beside the bed to record his ravings when a little later he would be in delirium. In earlier days such death-bed revelations had often given them valuable leads to subversive dissenters still living.

Garrison saw the fever eyes of the sick man following him about the room, but he went about what he had to do. He closed the door softly, and then stuck a wisp of cotton into the mike so as to damp its diaphragm for the time being. He sat down beside the patient and placed a cool hand on his forehead.

"The weeds have got me at last, I guess," said Clevering, smiling feebly, "weeds or blight. They're getting bad, you know."

"Yes, I know," said Garrison, "and that is why it is bad for Autarchia to lose a man who knows how to fight them."

"Autarchia?" whispered the other, "a lot Autarchia cares. If they knew what I know, they would have crucified me long ago. But you are not speaking for Autarchia, or you would not have shut off that spy's ear."

"By Autarchia I meant the human race," replied Garrison, soothingly. "I saw your farm last night. I really saw it, for I've been blind up to now. I want you to tell me how you kept your field clean. We have needs of a sort here too, you know."

Clevering smiled wanly.

"You want to know what I did, eh? Well, I forgot the Code when I saw it wasn't working any more. I tried this and that until I found something that did work. Organic things don't stay put. They grow and change and evolve. What stood off the blights when the Code was drawn isn't worth anything these days. I found that out years ago when it first got bad. I falsified my records so the inspectors wouldn't know. That is how I kept out of Penal House. Maybe I should have spoken out before, but who was there to hear? I do love a clean cornfield, though, and that's why I kept plugging. The books helped, too."

A spasm of shivering shook him as a fresh chill came on. Garrison gave a worried look at the chart. He had not arrived too soon. The next fever peak would probably be the last. Clevering was a dying man.

"What books?" asked Garrison sharply. "There are no books that I know of except the Code."

"The... the ones in the Autarch's secret library," managed Clevering through chattering teeth. "A few were stolen years ago by a dissenter who was a palace guard until the monitors found him out. They have been handed down through several generations to trusted fellow-believers. I am the last one. There are no others that I know of."

"I am one," said Garrison quietly. He was astonished at his own coolness when he said it, for twenty-four hours earlier he would have allowed wild horses to pull him apart rather than utter the blasphemous words. Now all that was changed.

"I am seeing people die who should not be dying," he explained. "I don't like it. The Code is—" here he almost choked on the words, such is strength of inhibiting doctrine, "the Code is—well, the Code is all wrong! It's got to be changed. It's got to be repealed!"

"I believe you," said Clevering, and pulled Garrison toward him so he could whisper, "the books are under a false flooring in a shed—"

Garrison listened attentively to the instructions, but before the patient quite finished, the fever got the better of him and he rambled off into incoherent nonsense. Garrison stayed on, for it was not all nonsense. There were lucid stretches in which Clevering lived his experiments again—the trying of this or another spray on the blights, and the application of various chemicals to learn which helped the corn and discouraged the weeds. At length the end came, and there was no more to do. Neomal had claimed another victim, this one appallingly swiftly. Garrison removed the plug of cotton and softly left the room.

Garrison's life for the next five weeks was a frenzied jumble

of concealed activity. Taking infinite care to wear the mask of

common apathy, and covering his movements with studied

casualness, he steadfastly pursued two aims. One was the reading

of the forbidden books, which he dug up during his first

available free time. Thereafter he read them in his room, hiding

them meanwhile in his mattress. The books were a strangely

variegated lot. Some were on scientific subjects, others social

or philosophic. There was history, too, and something about

religion. The book he came to love most of all was a very slim

one—a little volume on "Liberty" by a John Stuart Mill. His

limited vocabulary troubled him much at first, but he shrewdly

arrived at the meanings of such words as "choice" and "freedom"

by considering the context. He discovered to his delight that

there were shades between good and bad. There were the words

"better" and "best" as well as the bare, unqualified "good."

While the books opened up vistas unimagined to his thinking, it was at Sanitar that he performed his most imperative work. He wanted to find out why neomalitis had suddenly turned killer, and how to foil it. On the pretense of checking the biologists, he pored over blood and lymph specimens of the ever arriving patients. He built up culture colonies, and then tried to destroy them with modifications of the sulfa drug. The results were negative, so he tried other compounds. Then he cultured viruses, and pitted one strain against another. And as the average Psychic Resistance Index kept dropping lower he pondered that feature. Apparently the Diagnostats were not calibrated for patients so consistently depressed and without desire to live, for shortly the uncanny machines balked at giving any prognosis whatever. All that would come out was a meaningless jumble of characters.

At last the day came when he found a drug that killed the new

strain of neomal bacilli in the laboratory. He was careful to

restrain any expression of joy, though his impulse was to leap

into the air and yell "Eureka!" Instead, he cautiously loaded a

number of hypodermic needles and wandered into a ward.

He sent the attendants away on various errands, and set about the risky job he was compelled to do. He injected all the patients in the rooms on the left-hand side of the corridor. Then he went as soon as possible to his office and awaited results.

They were not long in coming. Within the hour an agitated treater rushed in.

"All hell has broken loose in 44-B," he reported. "It can't be neomalitis those patients have. They're in convulsions."

"I'll be right down," said Garrison. His bones had turned to water, but he had to see the thing through. He knew, from his belated reading, that one was supposed to experiment on guinea pigs and monkeys before injecting strong and untried medicines into human beings. But there were no longer any such animals. They had been decreed useless and were long extinct. Yet the patients were doomed anyhow—he felt justified in taking the chance. But he had not foreseen convulsions.

By the time he reached the ward the worst of the spasms had subsided. Some of his inoculated patients had succumbed in their agony. The remainder lay spent and gasping, with expressions of utmost horror on their faces. Garrison surveyed them stonily, but his heart was cold with anxiety.

"Very odd," he remarked, making notes. "I shall report it, of course."

He was too upset to do anything else that day, but that night he thought long and hard about it. The following morning he learned to his immense relief that only a few more of his illegally injected patients had died, whereas the half ward under Code treatment had lost its normal number—about eighty percent. During the tense day that followed, the survivors among his experimental subjects began to rally. By nightfall several had lost all symptoms. In a day or so, barring relapses, they could be discharged.

"I'm on the track," Garrison exulted. "Perhaps I used too strong a solution."

He attacked the problem with renewed fury. Day after day he tried dilutions and admixtures of other chemicals. There were unhappy results at times, but on the whole he was making splendid progress. At last there came a day when there were no deaths among the ones he treated by stealth. A grand glow of achievement warmed him, and when he returned to his office he could not help walking like one who had conquered the Earth. He had tried, fumbled, and then gone over the top. Now he understood the rewards that come to those who achieve by their own wit and handiwork.

But there was another kind of reward awaiting him. At the door of his office two grim monitors met him. They shut off his remonstrances with a blow across the face. Then he was hustled into an elevator and shot to the top of the tower where an angry director was pacing the floor. A smug inspector of pharmaceuticals was standing by with a packet of inventory sheets.

"Explain yourself, sirrah!" snorted the pompous, red-faced man who headed Sanitar. "What do you mean by forging chemical withdrawals? Sulfa drugs—pah! You have not used a gram of sulfazeoproponyl in ten days. Instead you—"

"Instead, I have been saving the lives of my patients," said Garrison quietly. "I gave them the Code stuff and they died, just as they are doing in the other wards. Therefore I knew that—"

"Silence!" roared the director, shutting him off. "Not a word more. Nothing... nothing, mind you... is as hideous as willful violation of the Code. What does it matter whether a thousand or more weaklings die? It is better so than to return to chaos. Monitors, do your duty!"

The monitors did their duty. They did it precisely as the

Penal Code said they must, exactly as it had been found necessary

in the early days when there were many rebels, and those tough

and fearless. They flung chains about his wrists and dragged him

to the elevator, kicking and cuffing him at every step. They

paraded him through the great lobby on the ground floor for the

edification of his brother ratings. And then they hurled him half

unconscious into the waiting prison van. After that for awhile

Garrison hardly knew what happened to him. There was a prolonged

session under a dazzling light, during which venomous voices

hurled abrupt questions at him. They injected him with scopa, and

they brought psychomeds of the Penal branch to try hypnosis on

him. They beat him at intervals, and confronted him with the

books they had uncovered in his room.

"You are fools, fools, FOOLS, I SAY!" he screamed when he could stand it no more. "Yes, I had an accomplice. His name was Clevering... Clevering the agronomist. He's dead now, so it does not matter. He kept the weeds out. He kept the blight out. So you have corn. That was contrary to the Code, but you have it!"

That was when his memory ceased to register. The things they did to him after that did not matter. Or they did not matter until hours later when he found himself crawling miserably on the hard steel floor of a cell. He felt his wounds and the stickiness of them made him faint again. After that he slept for many hours.

How many days he languished, sore and battered and hungry, in the dark he had no notion. He was hauled out one day for questioning by a solemn board of psychomeds. That was to determine his sanity. He answered them defiantly from between swollen lips and with words that had to be mumbled for lack of teeth. They overwhelmed him with scorn, and pronounced him sane. The Penal Code could take its course. After that there was more of darkness. Not one person in Sanitar or from Dorm attempted to communicate with him. He was unclean. He was different. He was a convicted dissenter. His name was already erased from the roster of the living.

It was an eternity after that when the four burly monitors

came in the dead of night, He heard the heavy tramp of their feet

in the corridor, and the crash as his door was thrown open. Then

hand flashlights played on him.

"Up, snake!" snarled one, and yanked him to his feet.

"Don't mark him any more," warned another. "The captain said not. The Autarch is going to work on this one in person, and they say he likes 'em fresh and able to take it."

The other monitors snickered, and something whispered was said that Garrison's ears did not catch. Then he was shoved into the desolate corridor and propelled forward. Next came a jolting, mad ride to the airport, and then comparative quiet as the giant stratoplane soared through the sky. Sometime later there was another ride in a van, with a stop after a bit for challenges and explanations. Then Garrison heard the creak of great bronze gates opening on seldom-used hinges, after which he was handed through a door and into a small elevator.

The moment he stepped out he knew he must be in the palace. He had not imagined such grandeur. The floors were heavily carpeted in rich designs, and the walls glowed with an eerie softness. Uniformed flunkies and guards stood everywhere, eying him curiously. Garrison became painfully aware of his own drab appearance, for he wore only a very dirty shirt badly stained with blood, and his body was encrusted with the muck of his cell floor. His beard had grown untouched since the first day of his incarceration. Add his bloodshot eyes and battered features to that and he knew he must present a perfect picture of a desperate criminal.

A silver-robed official of the palace intercepted them.

"Oh, he can't go in like that," he said. "He'll have to be washed. This way with him."

Garrison felt better after the repair work was done. He had resigned himself to taunts and tortures and ultimate death, but it felt good to be clean for once. They even trimmed his hair and shaved him, and dressed him fully with dark-blue silken clothes after applying pleasing ointments to his welts.

"You needn't mock," Garrison cried out, as they slipped the smooth cloths onto him. "I am a dissenter and proud of it. Let's get on with it."

"Take it easy," said the treater who had patched him up. "The Autarch would not have sent for you if you had been just an ordinary case."

They gave him a sweet mixture of chocolate and milk and put him in a darkened room to rest awhile, telling him that his audience was not to be until noon. He tried to rest, but could not. Too much was running around inside his head. He knew that he was condemned to die, for the monitors had told him as much. His hope was that before the hour came he could at least get the reason for his rebellion on the record.

An officer of the guard came and escorted him down the

carpeted halls. This time there were no harsh words or cuffing,

but stiff civility. He took him to a pair of richly-paneled doors

which two flunkies drew open. Garrison was told to go in, and the

doors closed silently behind him. He had entered alone; the

officer remained outside.

It was an immense square room, luxuriously appointed, and facing him was a massive desk beside which stood a man he knew must be the Autarch. He was a magnificent specimen of manhood, tall, barrel-chested, and commanding. He wore a robe of wine-red satin bound with cloth of gold, but his gray-streaked leonine head was bare. His gaze was steady on Garrison—a coldly appraising gaze from hard blue eyes, and under them an unsmiling mouth of iron. When he spoke it was with a deep and vibrant voice without a trace of emotion in it.

"So you are a rebel," said the Autarch, almost as if he were speaking to himself.

"I am."

Garrison was desperately afraid he was about to tremble, for the man's personality was overpowering, and nothing in his previous career had conditioned him to cope with it.

"Why?"

"I was failing in my job... despite the Code," said Garrison slowly, "and I felt I should do something about it. I did, and succeeded, after a fashion. I saved the lives of some of our citizens. That is my crime. If I had it to do over again, I would do the same."

"Ah," said the Autarch, taking a deep breath. "So you defy me?"

"You do not understand, or you would not call it defiance," said Garrison, astonished at his own boldness. But he had already suffered death a hundred times in anticipation and was beyond fearing it. Nothing mattered now. The Autarch frowned momentarily, but continued to size up his prisoner for a minute or so more.

"A real rebel, a genuine, sincere dissenter," he said softly, "at last."

He moved across the room.

"Sit down," he said, "I want to talk with you."

Garrison sat down and took the proffered cigarette, wondering whether he was on the cruel end of the cat-and-mouse game.

"During my reign," said the Autarch, "I have long wanted to meet one of you. From time to time they have brought me what was alleged to be such. They were sniveling cowards all—stupid, lazy, careless or inept people who had infringed the Code without intent. They had to die, of course, and did. It is the rule, and I am as helpless in the face of it as anyone. But I did hope to find out what was wrong with the world. They could not tell me. Perhaps you can. There is more than one way of dying, I may remind you, and I have considerable latitude in that matter."

"I see," said Garrison. Things were churning about inside his skull. There was the temptation to tell his captor what he wanted to hear and thereby earn a painless death. Yet he did not know what the Autarch wanted. Besides—

"The trouble with the world," said Garrison carefully, "is the Code itself. Civilization is an organism, made up of a myriad of lesser organisms. Organisms—men, animals, plants, and on down into the microcosm of minute life—all living things. They grow and develop and evolve. Or else they degenerate. They never stand still. Only the Code stands still. It is too rigid."

"I am not prepared to admit that," said the Autarch, "but go ahead. Prove your point if you can."

It was the opening Garrison hungered for. He recited the recent behavior of neomalitis—the strange turn it was taking, and the helplessness of the doctors in the face of an uncompromising Code. He explained how bacilli could differentiate into fresh and hardier strains, more contagious and deadlier than their predecessors. And how they might become immune to treatments formerly effective. Then he detailed his own experimentation, handicapped as that was by non-cooperation and the necessity of secrecy. He mentioned Clevering and his cornfields and emphasized the parallelism between the two situations. The conclusion was inescapable. However good the old procedures may have been in their day, they were not valid now. Radically new approaches were demanded.

"Perhaps," agreed the Autarch, thoughtfully. "There appears to be truth in what you say. I may as well tell you that other diseases are becoming rampant as well—new varieties of cholera, dysentery, and pneumonia. There is a wave of suicides, too. Cattle are dying. Many of our vital crops are failing from blight or insect attack. That is not all. Non-organic things are awry. Despite controls, gradual shifts of population have thrown central power plants out of balance, and left us with highway systems that are either congested or disused."

"A city or region may be regarded as an organism, too," Garrison reminded him.

"So I see. At any rate, it is a problem that has weighed on me for some time. It is growing urgent. Something must be done, and quickly."

"I know that," said Garrison dryly.

"If," suggested the Autarch, "I should see my way clear to grant you an indefinite reprieve—perhaps amounting to a full pardon—would you undertake to bring the diseases mentioned under control?"

Garrison smiled a thin, hard smile.

"I am only one man, excellency, and an ill-equipped one at that. I happened to be lucky in stumbling on the remedy right off. In another case it might take an army of research workers years. Only by putting thousands of trained men at it in ample laboratories could such a thing be done."

"Very well. You are the new Director General of Health. I delegate you to find such men and modify the Medical Code."

"How?" asked Garrison, with a short, scornful laugh. "It is too late for that—by a half dozen generations. Not to modify the Code, but to find the men. The kind of men we need do not develop under an autarchian regime. It is the senseless persecution of your predecessors that has brought us to the brink of ruin, not the plant and animal parasites you complain of. Free men would have disposed of them long ago. But that would have required initiative and adaptability, traits long since obliterated. Now the premium is on blind obedience. Men have lost the art of thinking; they will only do what they are told."

"That makes it all the easier," said the Autarch, reaching for a pad. "You write the order stating what you want done. I will promulgate it. It is as simple as that."

Garrison stared at him in blank amazement.

"Order what?" he asked. "Men of force and talent to reveal themselves? Who is to judge whether they have those qualities? And if there are such, they will take immense pains to conceal themselves. They are afraid. I know that, because I know my own reaction to your recent order relaxing the Social Code. I didn't understand it, and I didn't trust it. For all I knew the Monitors might be listening and taking it all down."

"They were," said the Autarch, "but nothing happened. I was worrying about the state of affairs throughout the world, and hoped to pick up a clue as to what was wrong. There was only silence."

"Ah," said Garrison, grimly. "That shows the effect of fear. And the deadliness of inertia. There must be many men among our billions who see what is happening and care, but they dare not speak. They see only the Penal Houses ahead for their pains. As to the vast majority... bah, they are sheep. They are accustomed only to orders from above. Without positive orders specific to the last little detail, they will not act. What else do you expect from a race of slaves?"

"Slaves!" exclaimed the Autarch. "In the high position you held, how dare you compare yourself with a slave?"

"Wasn't I? I could cast about and find a sweeter euphemism for it, but essentially that was it. I have never known anything but regimentation. I was flattered with the label of a high cerebral rating, but why they assigned me to my job on the basis of it is more than I can understand. The commonest field hand above the moron class could have done the work I did. A machine could have. What use is intelligence if you are not permitted to use it?"

"Yes," admitted the Autarch slowly, "I see that now. But that was then. You are not only permitted to use yours now, but ordered to. Use any means you please to assure them immunity from persecution, but issue your call—"

"It will take more than negative action," Garrison reminded him. "To break away from a life of routine a man needs positive motivation. And I do not mean promotion to a job as sterile as the one he has. It will have to be one to fire his soul and kindle his mind. Simply writing an order will not suffice."

There was an interruption. The major-domo of the Palace

brought in a folder of papers. It was the weekly summary of

events in Autarchia. The Autarch studied it with a face of

thunder, then handed it to Garrison.

It was a story of regression on all fronts. The worst news came from Asia, where the strange disease that resembled cholera but responded to none of its known controls was sweeping the continent. Millions were already dead, and every ship and stratoplane was spreading the epidemic farther.

"In the absence of anything better," Garrison remarked, "this should be isolated. You should declare an immediate quarantine."

"What is that?"

Garrison told him.

"That is out of the question," decided the Autarch, after a moment's consideration of what it implied. "It would be disastrous. The entire workings of the Code hinge on dependable supply and distribution. It—"

"It," flared Garrison, "shows you how rotten your precious system is. Even you, presumably the ablest man of us all, are stopped by it, though millions die. When things start cracking you're sunk. The holy framers thought they had attained perfection and saw no alternative. Well, cling to your sacred Code and ride to doom with it. But let's end this farce. Call your executioner and finish it."

They were both on their feet on the instant. The Autarch was visibly trying to control his anger, but Garrison was not to be stopped. The sickening sense of futility he first felt when Leona McWhisney died was back with him, a hundredfold more strong. His voice rose shrilly, and he threw discretion to the winds.

"The race is facing a life-and-death crisis," he shouted. "Pestilence is here, and famine is right around the corner. In the wake of those will come economic pandemonium. The Grand Code cannot cope with them. It was not designed to. All it does is stifle us. What we need is men of imagination and boldness, not content with covering themselves by complying with some stereotyped provision of the Code. We need them by the tens of thousands, and we cannot find them on account of this unwieldy body of stupid, frozen laws. There is no time for temporizing. The Code has got to go—lock, stock and barrel!"

Garrison said a lot else along the same line. The Autarch heard him out in moody silence. Then he grasped him by the arm and led him to a side door.

"My apartment is in there. Go rest. I believe there is something in your argument, but I want to think."

That interview was the beginning of a curious friendship. They

dined together that evening, and later talked far into the

night.

By the end of the week Garrison came to appreciate that the office of Autarch was as empty as any in the realm. There, too, the dead hand of the past lay heavily. Being top dog of the pyramid of bureaucracy meant little, for in Autarchia precedent ruled. Autarchs had occasionally added to the Code, but not one had ever repealed a provision.

The books confiscated at the time of Garrison's arrest were sent for by the Autarch. He was amazed at their contents, and began to understand better the workings of his guest's mind. He liked the technical ones best; the one he could stomach least was the little essay by Mill. The idea of an individualistic society was beyond his comprehension, but on the whole he was impressed.

"Garrison," he said, "I am convinced you have more practical ideas than I. I am ready now to take advice. We will modify the Code for the emergency. You write the orders, I will issue them."

"I won't do it," said Garrison. "I don't know enough. And if I did, I still wouldn't. The principle is wrong."

"What principle?"

"The principle of handing down wisdom from aloft. The principle of autocracy, if you want to know. It is an evil thing. History has never produced a man who knew everything—"

"He can surround himself with advisers."

"Of his own picking," countered Garrison. "Yes-men they used to call them. Which is worse. It is a device to reinforce a dictator's illusions as to his own infallibility. What he needs is not a chorus of undiscriminating yessing, but frank and brutal criticism. He can get that only in a democracy."

"Democracy!" cried the Autarch scornfully. "Anarchy, you mean. What is a democracy but a howling mob of forty opinions, each as little informed as the next? Where, after an infinity of muddling and compromise, some self-styled leader manages to wheedle an agreement among fifty-one out of a hundred of the mass, whereupon he proclaims a half truth as the whole. That is clumsy nonsense. The world had democracies once. Look what happened to them!"

"Look at what is happening to their flawless successors," said Garrison quietly.

The Autarch reddened.

"At least," Garrison argued, "in a democracy the ordinary man had something to live for. He wasn't a poor pawn. If he hit on a good idea and had the will and personality to promote it, he had a chance of getting somewhere. He didn't vegetate or degenerate into the flesh-and-blood robots we have about us now. Competition with his fellows kept him from doing that. Sure, he made errors. But he did not make the stupidest of all—of freezing them into an inflexible Code. Where freedom is, a man can develop. If he is wrong, others are free to say so. Some will back him, others oppose, which is the very thing the framers of the Code thought so deplorable. But out of the conflict the better idea usually won."

"After years of wrangling and with many setbacks," objected the Autarch.

"Rather, after continual adjustments to current needs," corrected Garrison. "Democracy may have had its faults, but lack of adaptability was not one of them. In freedom of speech and reasonable freedom of action it had the machinery for correcting any intolerable fault. Which is more than you can say for your own absurd system."

"All right," retorted the Autarch. "For argument's sake suppose I grant your point. How, in view of the sheeplike nature of my people which you keep harping on, could we reinstitute an obsolete form of society such as you advocate? I offered 'em free speech, and you know what happened."

"Wake 'em up," yelled Garrison. "Make 'em mad. Then you'd see."

"With no Code to guide them? I see nothing but chaos."

"We needn't repeal the whole of the Code. Considered as a guide it isn't bad at all. Its evil feature is its pretence of being infallible. We'll teach the people how to judge when to follow and when to diverge."

"That from you," snorted the Autarch. "You, who wouldn't even tackle the revision of the Medical Code! Now you propose to upset the entire apple-cart, and destroy the people's confidence. What will you replace it with, and how?"

"What with?" smiled Garrison. "There is always your great sealed library. You have seen a small sample of it and liked it. The Code was based on it. It must be good. As to how, that will come later."

"Let's look," said the Autarch, with sudden resolution. He dug keys and combinations out of a safe.

They reached the library through a long underground passage heavy with the dust of time. Once they passed the guards at the outer barrier they were on pavement untrod for decades. Then they came to a heavy circular door that had to be opened by a complicated group of methods. At length it swung open and they stepped through.

Both gasped at the immensity of the place. Not every book ever published was there—only the ones considered by the framers in compiling the Code. But since they covered every field of human activity in utmost detail, they numbered in the millions. The stacks stretched away for thousands of feet of well-lit, air- conditioned space. The magnitude of the task they had so lightly assumed almost overwhelmed them.

After a long hunt Garrison found the medical section. He was again appalled at the extent of it, for the volumes dealing with any single aspect of his profession took up yards of shelving. He skipped histology, obstetrics, dermatology, and dozens more. There was just too much of it. How was he ever to read it all, let alone sift the chaff from the substance? He ducked the questions neatly by concentrating on the volumes devoted to the techniques of research.

Meanwhile the Autarch was delving elsewhere. He was deep among the histories and philosophies, with occasional excursions into political economy. Soon the aisles where he roamed were cluttered with "must" books. His first samplings had produced material for half a lifetime of study.

Hours later they left the place, exhausted, but burdened with books. Sheer fatigue cut their dinner talk that night to the barest minimum.

"How can we know," groaned the Autarch, "what part of this stuff is bad, and what not?"

"We'll have to leave it to the people," was Garrison's reply. "We need too many people and in too many varied fields to try to select for them. They will have to do that themselves."

"That will bring chaos, I say," grumbled the Autarch. "Anarchy. Your cure is as bad as the disease, I'm afraid."

"All right," grinned Garrison, as a sudden inspiration hit him. "I'm an anarchist. Let's analyze it. Autocracy is the complete denial of the individual. Anarchy is his fullest possible assertion. Democracy lies halfway between; under it an individual can be himself, but is subject to certain restraints. Very well. You continue to play the Autarch. I'll be the Anarch—"

"And between us we'll produce the Demagogue," remarked the Autarch, sharing his grin. "A fascinating gamble, I must say. And pray tell, my insane friend, how do we achieve this miracle?"

"You continue to issue edicts."

"Yes?"

"And I will see that they are not obeyed," chuckled Garrison.

Strange happenings came to pass shortly after that. The

sprawling radio center known as Omnivox overflowed into adjoining

buildings hastily remodeled as annexes. Peremptory calls were

sent out to Propags all over the world. Soon they came streaming

into Cosmopolis on every arriving stratoliner. There they met a

puzzling individual—one Philip Garrison, the newly appointed

Chief of Propaganda. He told them that for one month they would

read and not talk. In the meantime the standard lecture courses

were to be suspended.

At the same time the citizens of the provinces were treated to a bewildering succession of orders. The Grand Code, they were informed, was to be revised in the near future. Until that time they should continue to use it as a guide, but might depart from it in certain stated emergencies. Propag lectures stopped as the lecturers were withdrawn, but the culture courses were continued for the time being. There was a difference, though. An army of carpenters descended on the various Social Halls and cut them up into many small compartments by partitions. Each was fitted with an omnivox-screen. The most startling innovation was the broadcast instructions to the Monitor Corps. They were forbidden to molest dissenters. On the contrary, they were given strict orders to protect them from the orthodox, should those show signs of resenting their heresies.

The results as both Autarch and Garrison had anticipated, were meager. They listened in at random over the monitorial wires and knew. For a few days there was a buzz of excitement, then the people relapsed into their customary apathy. They continued to do the things they always had done, and in exactly the same manner. In all the world there were less than five hundred who took the strange edicts at anything like face value. Some were doctors, who now openly experimented as Garrison had done. The rest were in other professions.

The Autarch wanted to send for them and add them to his staff.

"No," said Garrison, "they will be more useful where they are. Moreover, if you do that you may scare others. There must be more than half a thousand alert minds on five continents. We've still got those to smoke out."

The preliminaries took the whole of the estimated month. The

zero hour was near at hand. The Propags had finished their