RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

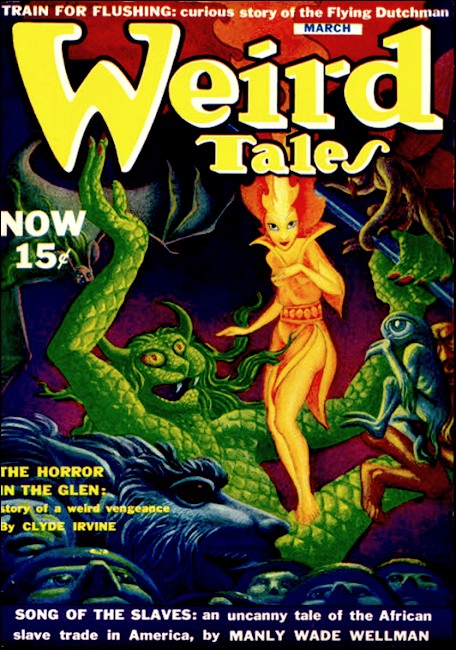

Weird Tales, March 1940, with "Train for Flushing"

THEY ought never to have hired that man. Even the most stupid of personnel managers should have seen at a glance that he was mad. Perhaps it is too much to expect such efficiency these days—in my time a thing like this could not have happened. They would have known the fellow was under a curse! It only shows what the world has come to. But I can tell you that if we ever get off this crazy runaway car, I intend to turn the Interboro wrong-side out. They needn't think because I am an old man and retired that I am a nobody they can push around. My son Henry, the lawyer one, will build a fire under them—he knows people in this town.

"And I am not the only victim of the maniac. There is a pleasant, elderly woman here in the car with me. She was much frightened at first, but she had recognized me for a solid man, and now she stays close to me all the time. She is a Mrs. Herrick, and a quite nice woman. It was her idea that I write this down—it will help us refresh our memories when we come to testify.

"Just at the moment, we are speeding atrociously downtown along the Seventh Avenue line of the subway—but we are on the uptown express track! The first few times we tore through those other trains it was terrible—I thought we were sure to be killed—and even if we were not, I have to think of my heart. Dr. Steinback told me only last week how careful I should be. Mrs. Herrick has been very brave about it, but it is a scandalous thing to subject anyone to, above all such a kindly little person.

"The madman who seems to be directing us (if charging wildly up and down these tracks implies direction), is now looking out the front door, staring horribly at the gloom rushing at us. He is a big man and heavy-set, very weathered and tough-looking. I am nearing eighty and slight.

"There is nothing I can do but wait for the final crash; for crash we must, sooner or later, unless some Interboro official has brains enough to shut off the current to stop us. If he escapes the crash, the police will know him by his heavy red beard and tattooing on the backs of his hands. The beard is square-cut and there cannot be another one like it in all New York.

"But I notice I have failed to put down how this insane ride began. My granddaughter, Mrs. Charles L. Terneck, wanted me to see the World's Fair, and was to come in from Great Neck and meet me at the subway station. I will say that she insisted someone come with me, but I can take care of myself—I always have—even if my eyes and ears are not what they used to be.

The train was crowded, but somebody gave me a seat in a corner. Just before we reached the stop, the woman next to me, this Mrs. Herrick, had asked if I knew how to get to Whitestone from Flushing. It was while I was telling her what I knew about the busses, that the train stopped and let everybody off the car but us. I was somewhat irritated at missing the station, but knew that all I had to do was stay on the car, go to Flushing and return. It was then that the maniac guard came in and behaved so queerly.

"This car was the last one in the train, and the guard had been standing where he belongs, on the platform. But he came into the car, walking with a curious rolling walk (but I do not mean to imply he was drunk, for I do not think so) and his manner was what you might call masterful, almost overbearing. He stopped at the middle door and looked very intensely out to the north, at the sound.

"'That is not the Scheldt!' he called out, angrily, with a thick, foreign accent, and then he said 'Bah!' loudly, in a tone of disgusted disillusionment.

"He seemed of a sudden to fly into a great fury. The train was just making its stop at the end of the line, in Flushing. He rushed to the forward platform and somehow broke the coupling. At the same moment, the car began running backward along the track by which we had come. There was no chance for us to get off, even if we had been young and active. The doors were not opened, it happened so quickly.

"Then he came into the car, muttering to himself. His eye caught the sign of painted tin they put in the windows to show the destination of the trains. He snatched the plate lettered 'Flushing' and tore it to bits with his rough hands, as if it had been cardboard, throwing the pieces down and stamping on them.

"'That is not Flushing. Not my Flushing—not Vlissingen! But I will find it. I will go there, and not all the devils in Hell nor all the angels in Heaven shall stop me!'

"He glowered at us, beating his breast with his clenched fists, as if angry and resentful at us for having deceived him in some manner. It was then that Mrs. Herrick stooped over and took my hand. We had gotten up close to the door to step out at the World's Fair station, but the car did not stop. It continued its wild career straight on, at dizzy speed.

"'Rugwaartsch!' he shouted, or something equally unintelligible. 'Back I must go, like always, but yet will find my Vlissingen!'

"Then followed the horror of pitching headlong into those trains! The first one we saw coming, Mrs. Herrick screamed. I put my arm around her and braced myself as best I could with my cane. But there was no crash, just a blinding succession of lights and colors, in quick winks. We seemed to go straight through that train, from end to end, at lightning speed, but there was not even a jar. I do not understand that, for I saw it coming, clearly. Since, there have been many others. I have lost count now, we meet so many, and swing from one track to another so giddily at the end of runs.

"But we have learned, Mrs. Herrick and I, not to dread the collisions —or say, passage—so much. We are more afraid of what the bearded ruffian who dominates this car will do next—surely we cannot go on this way much longer, it has already been many, many hours. I cannot comprehend why the stupid people who run the Interboro do not do something to stop us, so that the police could subdue this maniac and I can have Henry take me to the District Attorney."

So read the first few pages of the notebook turned over to me by the Missing Persons Bureau. Neither Mrs. Herrick, nor Mr. Dennison, whose handwriting it is, has been found yet, nor the guard he mentions. In contradiction, the Interboro insists no guard employed by them is unaccounted for, and further, that they never had had a man of the above description on their payrolls.

On the other hand, they have as yet produced no satisfactory explanation of how the car broke loose from the train at Flushing.

I agree with the police that this notebook contains matter that may have some bearing on the disappearances of these two unfortunate citizens; yet here in the Psychiatric Clinic we are by no means agreed as to the interpretation of this provocative and baffling diary.

The portion I have just quoted was written with a fountain pen in a crabbed, tremulous hand, quite exactly corresponding to the latest examples of old Mr. Dennison's writing. Then we find a score or more of pages torn out, and a resumption of the record in indelible pencil. The handwriting here is considerably stronger and more assured, yet unmistakably that of the same person. Farther on, there are other places where pages have been torn from the book, and evidence that the journal was but intermittently kept. I quote now all that is legible of the remainder of it.

Judging by the alternations of the cold and hot seasons, we have now been on this weird and pointless journey for more than ten years. Oddly enough, we do not suffer physically, although the interminable rushing up and down these caverns under the streets becomes boring. The ordinary wants of the body are strangely absent, or dulled. We sense heat and cold, for example, but do not find their extremes particularly uncomfortable, while food has become an item of far distant memory. I imagine, though, we must sleep a good deal.

"The guard has very little to do with us, ignoring us most of the time as if we did not exist. He spends his days sitting brooding at the far end of the car, staring at the floor, mumbling in his wild, red beard. On other days he will get up and peer fixedly ahead, as if seeking something. Again, he will pace the aisle in obvious anguish, flinging his outlandish curses over his shoulder as he goes. 'Verdoemd' and 'verwenscht' are the commonest ones—we have learned to recognize them—and he tears his hair in frenzy whenever he pronounces them. His name, he says, is Van Der Dechen, and we find it politic to call him 'Captain.'

"I have destroyed what I wrote during the early years (all but the account of the very first day); it seems rather querulous and hysterical now. I was not in good health then, I think, but I have improved noticeably here, and that without medical care. Much of my stiffness, due to a recent arthritis, has left me, and I seem to hear better.

"Mrs. Herrick and I have long since become accustomed to our forced companionship, and we have learned much about each other. At first, we both worried a good deal over our families' concern about our absence. But when this odd and purposeless kidnapping occurred, we were already so nearly to the end of life (being of about the same age) that we finally concluded our children and grand-children must have been prepared for our going soon, in any event. It left us only with the problem of enduring the tedium of the interminable rolling through the tubes of the Interboro.

"In the pages I have deleted, I made much of the annoyance we experienced during the early weeks due to flickering through oncoming trains. That soon came to be so commonplace, occurring as it did every few minutes, that it became as unnoticeable as our breathing. As we lost the fear of imminent disaster, our riding became more and more burdensome through the deadly monotony of the tunnels.

"Mrs. Herrick and I diverted ourselves by talking (and to think in my earlier entries in this journal I complained of her garrulousness!) or by trying to guess at what was going on in the city above us by watching the crowds on the station platforms. That is a difficult game, because we are running so swiftly, and there are frequent intervening trains. A thing that has caused us much speculation and discussion is the changing type of advertising on the bill-posters. Nowadays they are featuring the old favorites—many of the newer toothpastes and medicines seem to have been withdrawn. Did they fail, or has a wave of conservative reaction overwhelmed the country?

"Another marvel in the weird life we lead is the juvenescence of our home, the runaway car we are confined to. In spite of its unremitting use, always at top speed, it has become steadily brighter, more new-looking. Today it has the appearance of having been recently delivered from the builders' shops.

I learned half a century ago that having nothing to do, and all the time in the world to do it in, is the surest way to get nothing done. In looking in this book, I find it has been ten years since I made an entry! It is a fair indication of the idle, routine life in this wandering car. The very invariableness of our existence has discouraged keeping notes. But recent developments are beginning to force me to face a situation that has been growing ever more obvious. The cumulative evidence is by now almost overwhelming that this state of ours has a meaning—has an explanation. Yet I dread to think the thing through—to call its name! Because there will be two ways to interpret it. Either it is as I am driven to conclude, or else I ...

"I must talk it over frankly with Nellie Herrick. She is remarkably poised and level-headed, and understanding. She and I have matured a delightful friendship.

"What disturbs me more than anything is the trend in advertising. They are selling products again that were popular so long ago that I had actually forgotten them. And the appeals are made in the idiom of years ago. Lately it has been hard to see the posters, the station platforms are so full. In the crowds are many uniforms, soldiers and sailors. We infer from that there is another war—but the awful question is, 'What war?'

"Those are some of the things we can observe in the world over there. In our own little fleeting world, things have developed even more inexplicably. My health and appearance, notably. My hair is no longer white! It is turning dark again in the back, and on top. And the same is true of Nellie's. There are other similar changes for the better. I see much more clearly and my hearing is practically perfect.

"The culmination of these disturbing signals of retrogression has come with the newest posters. It is their appearance that forces me to face the facts. Behind the crowds we glimpse new appeals, many and insistent—'BUY VICTORY LOAN BONDS!' From the number of them to be seen, one would think we were back in the happy days of 1919, when the soldiers were coming home from the World War.

My talk with Nellie has been most comforting and reassuring. It is hardly likely that we should both be insane and have identical symptoms. The inescapable conclusion that I dreaded to put into words is so—it must be so. In some unaccountable manner, we are unliving life! Time is going backward! 'Rugwaartsch,' the mad Dutchman said that first day when he turned back from Flushing; 'we will go backward'—to hisFlushing, the one he knew. Who knows what Flushing he knew? It must be the Flushing of another age, or else why should the deranged wizard (if it is he who has thus reversed time) choose a path through time itself? Helpless, we can only wait and see how far he will take us.

"We are not wholly satisfied with our new theory. Everything does not go backward; otherwise how could it be possible for me to write these lines? I think we are like flies crawling up the walls of an elevator cab while it is in full descent. Their own proper movements, relative to their environment, are upward, but all the while they are being carried relentlessly downward. It is a sobering thought. Yet we are both relieved that we should have been able to speak it. Nellie admits that she has been troubled for some time, hesitating to voice the thought. She called my attention to the subtle way in which our clothing has been changing, an almost imperceptible de-evolution in style.

We are now on the lookout for ways in which to date ourselves in this headlong plunging into the past. Shortly after writing the above, we were favored with one opportunity not to be mistaken. It was the night of the Armistice. What a night in the subway! Then followed, in inverse order, the various issues of the Liberty Bonds. Over forty years ago-counting time both ways, forward, then again backward—I was up there, a dollar-a-year man, selling them on the streets. Now we suffer a new anguish, imprisoned down here in this racing subway car. The evidence all around us brings a nostalgia that is almost intolerable. None of us knows how perfect his memory is until it is thus prompted. But we cannot go up there, we can only guess at what is going on above us.

"The realization of what is really happening to us has caused us to be less antagonistic to our conductor. His sullen brooding makes us wonder whether he is not a fellow victim, rather than our abductor, he seems so unaware of us usually. At other times, we regard him as the principal in this drama of the gods and are bewildered at the curious twist of Fate that has entangled us with the destiny of the unhappy Van Der Dechen, for unhappy he certainly is. Our anger at his arrogant behavior has long since died away. We can see that some secret sorrow gnaws continually at his heart.

"'There is een vloek over me,' he said gravely, one day, halting unexpectedly before us in the midst of one of his agitated pacings of the aisle. He seemed to be trying to explain—apologize for, if you will —our situation. 'Accursed I am, damned!' He drew a great breath, looking at us appealingly. Then his black mood came back on him with a rush, and he strode away growling mighty Dutch oaths. 'But I will best them—God Himself shall not prevent me—not if it takes all eternity!'

Our orbit is growing more restricted. It is a long time now since we went to Brooklyn, and only the other day we swerved suddenly at Times Square and cut through to Grand Central. Considering this circumstance, the type of car we are in now, and our costumes, we must be in 1905 or thereabouts. That is a year I remember with great vividness. It was the year I first came to New York. I keep speculating on what will become of us. In another year we will have plummeted the full history of the subway. What then? Will that be the end?

"Nellie is the soul of patience. It is a piece of great fortune, a blessing, that since we were doomed to this wild ride, we happened in it together. Our friendship has ripened into a warm affection that lightens the gloom of this tedious wandering.

It must have been last night that we emerged from the caves of Manhattan. Thirty-four years of darkness is ended. We are now out in the country, going west. Our vehicle is not the same, it is an old-fashioned day coach, and ahead is a small locomotive. We cannot see engineer or fireman, but Van Der Dechen frequently ventures across the swaying, open platform and mounts the tender, where he stands firmly with wide-spread legs, scanning the country ahead through an old brass long-glass. His uniform is more nautical than railroadish —it took the sunlight to show that to us. There was always the hint of salt air about him. We should have known who he was from his insistence on being addressed as Captain.

"The outside world is moving backward! When we look closely at the wagons and buggies in the muddy trails alongside the right of way fence, we can see that the horses or mules are walking or running backward. But we pass them so quickly, as a rule, that their real motion is inconspicuous. We are too grateful for the sunshine and the trees after so many years of gloom, to quibble about this topsy-turvy condition.

Five years in the open has taught us much about Nature in reverse. There is not so much difference as one would suppose. It took us a long time to notice that the sun rose in the west and sank in the east. Summer follows winter, as it always has. It was our first spring, or rather, the season that we have come to regard as spring, that we were really disconcerted. The trees were bare, the skies cloudy, and the weather cool. We could not know, at first sight, whether we had emerged into spring or fall.

"The ground was wet, and gradually white patches of snow were forming. Soon, the snow covered everything. The sky darkened and the snow began to flurry, drifting and swirling upward, out of sight. Later we saw the ground covered with dead leaves, so we thought it must be fall. Then a few of the trees were seen to have leaves, then all. Soon the forests were in the full glory of red and brown autumn leaves, but in a few weeks those colors turned gradually through oranges and yellows to dark greens, and we were in full summer. Our 'fall,' which succeeded the summer, was almost normal, except toward the end, when the leaves brightened into paler greens, dwindled little by little to mere buds and then disappeared within the trees.

"The passage of a troop train, its windows crowded with campaign-hatted heads and waving arms tells us another war has begun (or more properly, ended). The soldiers are returning from Cuba. Our wars, in this backward way by which we approach and end in anxiety! More nostalgia—I finished that war as a major. I keep looking eagerly at the throngs on the platforms of the railroad stations as we sweep by them, hoping to sight a familiar face among the yellow-legged cavalry. More than eighty years ago it was, as I reckon it, forty years of it spent on the road to senility and another forty back to the prime of life.

"Somewhere among those blue-uniformed veterans am I, in my original phase, I cannot know just where, because my memory is vague as to the dates. I have caught myself entertaining the idea of stopping this giddy flight into the past, of getting out and finding my way to my former home. Only, if I could, I would be creating tremendous problems—there would have to be some sort of mutual accommodation between my alter ego and me. It looks impossible, and there are no precedents to guide us.

"Then, all my affairs have become complicated by the existence of Nell. She and I have had many talks about this strange state of affairs, but they are rarely conclusive. I think I must have over-estimated her judgment a little in the beginning. But it really doesn't matter. She has developed into a stunning woman and her quick, ready sympathy makes up for her lack in that direction. I glory particularly in her hair, which she lets down some days. It is thick and long and beautifully wavy, as hair should be. We often sit on the back platform and she allows it to blow free in the breeze, all the time laughing at me because I adore it so.

"Captain Van Der Dechen notices us not at all, unless in scorn. His mind, his whole being, is centered on getting back to Flushing— hisFlushing, that he calls Vlissingen—wherever that may be in time or space. Well, it appears that he is taking us back, too, but it is backward in time for us. As for him, time seems meaningless. He is unchangeable. Not a single hair of that piratical beard has altered since that far-future day of long ago when he broke our car away from the Interboro train in Queens. Perhaps he suffers from the same sort of unpleasant immortality the mythical Wandering Jew is said to be afflicted with—otherwise why should he complain so bitterly of the curse he says is upon him?

"Nowadays he talks to himself much of the time, mainly about his ship. It is that which he hopes to find since the Flushing beyond New York proved not to be the one he strove for. He says he left it cruising along a rocky coast. He has either forgotten where he left it or it is no longer there, for we have gone to all the coastal points touched by the railroads. Each failure brings fresh storms of rage and blasphemy; not even perpetual frustration seems to abate the man's determination or capacity for fury.

That Dutchman has switched trains on us again! This one hasn't even Pintsch gas, nothing but coal oil. It is smoky and it stinks. The engine is a woodburner with a balloon stack. The sparks are very bad and we cough a lot.

"I went last night when the Dutchman wasn't looking and took a look into the cab of the engine. There is no crew and I found the throttle closed. A few years back that would have struck me as odd, but now I have to accept it. I did mean to stop the train so I could take Nell off, but there is no way to stop it. It just goes along, I don't know how.

"On the way back I met the Dutchman, shouting and swearing the way he does, on the forward platform. I tried to throw him off the train. I am as big and strong as he is and I don't see why I should put up with his overbearing ways. But when I went to grab him, my hands closed right through. The man is not real! It is strange I never noticed that before. Maybe that is why there is no way to stop the train, and why nobody ever seems to notice us. Maybe the train is not real, either. I must look tomorrow and see whether it casts a shadow. Perhaps even we are not ...

"But Nell is real. I know that.

The other night we passed a depot platform where there was a political rally—a torchlight parade. They were carrying banners. 'Garfield for President.' If we are ever to get off this train, we must do it soon.

"Nell says no, it would be embarrassing. I try to talk seriously to her about us, but she just laughs and kisses me and says let well enough alone. I wouldn't mind starting life over again, even if these towns do look pretty rough. But Nell says that she was brought up on a Kansas farm by a step-mother and she would rather go on to the end and vanish, if need be, than go back to it.

"That thing about the end troubles me a lot, and I wish she wouldn't keep mentioning it. It was only lately that I thought about it much, and it worries me more than death ever did in the old days. We know when it will be! 1860 for me—on the third day of August. The last ten years will be terrible—getting smaller, weaker, more helpless all the time, and winding up as a messy, squally baby. Why, that means I have only about ten more years that are fit to live; when I was this young before, I had a lifetime ahead. It's not right! And now she has made a silly little vow— 'Until birth do us part!'—and made me say it with her!

It is too crowded in here, and it jolts awfully. Nell and I are cooped up in the front seats and the Captain stays in the back part—the quarterdeck, he calls it. Sometimes he opens the door and climbs up into the driver's seat. There is no driver, but we have a four-horse team and they gallop all the time, day and night. The Captain says we must use a stagecoach, because he has tried all the railroad tracks and none of them is right. He wants to get back to the sea he came from and to his ship. He is not afraid that it has been stolen, for he says most men are afraid of it—it is a haunted ship, it appears, and brings bad luck.

"We passed two men on horses this morning. One was going our way and met the other coming. The other fellow stopped him and I heard him holler, 'They killed Custer and all his men!' and the man that was going the same way we were said, 'The bloodthirsty heathens! I'm a-going to jine!'

Nellie cries a lot. She's afraid of Indians. I'm not afraid of Indians. I would like to see one.

"I wish it was a boy with me, instead of this little girl. Then we could do something. All she wants to do is play with that fool dolly. We could make some bows and arrows and shoot at the buffaloes, but she says that is wicked.

"I tried to get the Captain to talk to me, but he won't. He just laughed and laughed, and said,

"'Een tijd kiezen voor—op schip!'

"That made me mad, talking crazy talk like that, and I told him so.

"'Time!' he bellows, laughing like everything.' 'Twill all be right in time!' And he looks hard at me, showing his big teeth in his beard. 'Four —five—six hundred years—more—it is nothing. I have all eternity! But one more on my ship, I will get there. I have sworn it! You come with me and I will show you the sea—the great Indian Sea behind the Cape of Good Hope. Then some day, if those accursed head winds abate, I will take you home with me to Flushing. That I will, though the Devil himself, or all the—' And then he went off to cursing and swearing the way he always does in his crazy Dutchman's talk.

Nellie is mean to me. She is too bossy. She says she will not play unless I write in the book. She says I am supposed to write something in the book every day. There is not anything to put in the book. Same old stagecoach. Same old Captain. Same old everything. I do not like the Captain. He is crazy. In the night-time he points at the stars shining through the roof of the coach and laughs and laughs. Then he gets mad, and swears and curses something awful. When I get big again, I am going to kill him—I wish we could get away —I am afraid—it would be nice if we could find mamma—"

This terminates the legible part of the notebook. All of the writing purporting to have been done in the stagecoach is shaky, and the letters are much larger than earlier in the script. The rest of the contents is infantile scribblings, or grotesque childish drawings. Some of them show feathered Indians drawing bows and shooting arrows. The very last one seems to represent a straight up and down cliff with wiggly lines at the bottom to suggest waves, and off a little way is a crude drawing of a galleon or other antique ship.

This notebook, together with Mr. Dennison's hat and cane and Mrs. Herrick's handbag, were found in the derailed car that broke away from the Flushing train and plunged off the track into the Meadows. The police are still maintaining a perfunctory hunt for the two missing persons, but I think the fact they brought this journal to us clearly indicates they consider the search hopeless. Personally, I really do not see of what help these notes can be. I fear that by now Mr. Dennison and Mrs. Herrick are quite inaccessible.