RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

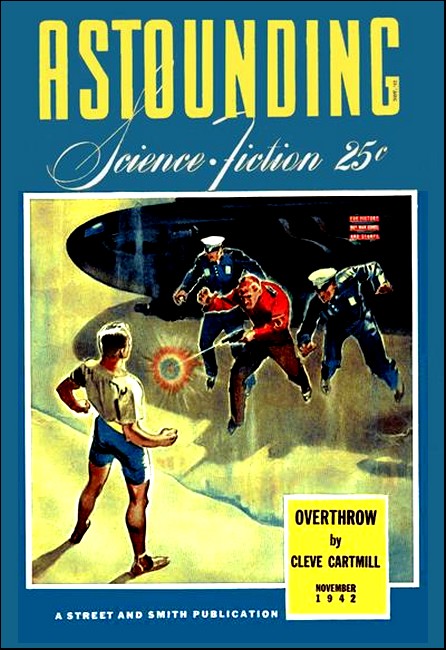

Astounding Science-Fiction, November 1942, with "Eureka!"

IN April 1942 Astounding Science-Fiction launched an open-ended series of "tall stories" under the general title "Probability Zero!" Writers were invited to submit contributions as entries in a competition, with prize money going to the first-, second- and third-placed stories each month.

The first three items published in the new series were: "Some Curious Effects of Time Travel," by Sprague de Camp; "Pig Trap," by Malcolm Jameson; and "Time Pussy," by George E. Dale.

Following the third item, the Editor printed the following description of the new series:

... The little items preceding were concocted, of course, by a sound trio of first-class, professional liars. In a length of this sort—some five hundred to seven hundred and fifty words—I think that there ought to be a number of excellent amateur liars, though. There may or may not be a "Probability Zero" department next month; the succeeding issue, however, will certainly have one—one concocted by amateurs and professionals alike. This month's supply of examples were bought at our standard space-rates; hereafter "Probability Zero" will be conducted as an open contest, wherein anyone equipped with a good, round prevarication is welcome. Readers will be invited to vote for the best of those published; the author of the winner will get twenty dollars, second place acquires ten, and third gets our check for five. Checks will be mailed as soon as the issue is decided.

To define the essence of the thing: We want science-fictional masterpieces that sound almost possible, but which are, as the department title states, "Probability Zero"—impossible by reason of known scientific law or by definition. They must be typed, double-spaced, and on one side of the usual size typewriter paper.

The old gag about truth being stranger than fiction is founded soundly; many an actual truth is highly implausible. We're looking for the exact reverse-something that's absolutely untrue, but highly plausible sounding.

For instance, it's a fact that a powerful jet of air—a real, roaring blast of air—will not blow a ball away; it will hold even a solid, fairly dense ball like a billiard ball supported in midair, pulling it back into the hardest, fastest part of the air-blast if it tries to waver out. That is obviously implausible; it happens to be true. It is also true that if you have a rope or chain running rapidly over two pulleys, with a considerable amount of slack in the chain, you can bend the chain's course into a loop—and have the loop stay there after removing the original deflecting force. The rapidly-moving chain will faithfully trace a course around the obstacle long after it has been removed, following a complicated S-course, even though under considerable tension. That's a rather implausible fact.

If facts can be that implausible, a good plausible lie should be fairly easy.

Click here to access a detailed bibliography of the Probability Zero! series in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database.

—Roy Glashan, 30 March 2022

PROFESSOR GLEASON said, "All right," and hung up the phone, "The Mad Scientist is on the way over," he told his lab director, Max Sunderberg. "Says he has made a great discovery."

"Uh-huh," said Sunderberg, adjusting the flame under a retort. "He often does. Did you ever hear what drove him mad?"

"There are several accounts. Which version do you know?"

"The one about the hole tongs. He always raves when you mention them. They work perfectly, but nobody will finance them. It broke his heart."

Sunderberg stepped to the sink and began washing his hands.

"M.S. got interested in holes when he was just a little shaver. He started collecting them—worm holes first, then woodpecker holes. He invented a gadget he called the hole extractor. You insert it in the hole, expand it a little, then give it a twist. When you pull it out the hole comes out with it. His attic is full of cases of those holes."

"What on earth does a wall-less hole look like?"

"Nothing. That's what makes M.S. mad. Nobody can see 'em. An unencased hole is just a bunch of air. Well, he improved his device until he hit on a big heavy-duty hole puller. He thought it would be a good idea to buy up used oil wells, lift out the holes an sell 'em."

"How did he propose to handle holes a mile or more long?"

"Oh, he never meant to use 'em again for oil wells. He was going to saw 'em up into short lengths and sell 'em for post holes—"

There was a knock at the door. Gleason opened it. There stood the Mad Scientist with a two-gallon water bottle in one hand. It seemed to be nearly full.

"Here it is," said the M.S. proudly, and promptly proceeded to decant the contents of his bottle into a handy beaker.

"Here is what?"

"You'll see," the M.S. said. He began helping himself to various chemicals about the laboratory. He dropped in a big lump of sulphur. It dissolved instantly. Iron, gold, platinum, rubber, a brickbat—all went the same way. The M.S. kept on. At the end of the hour he had demonstrated that his mixture would dissolve anything put into it.

"I begin to see," said Sunderberg, with a strange gleam in his eye. "But tell me, will it dissolve glass?"

"Oh, sure," said the M.S. He grabbed up a handful of pipettes and broke them like macaroni. They disappeared in the liquid like sugar does in hot water. He tossed in a quartz crystal, a handful of sand, and a glass cube that was weighting down some papers. They went, too.

"It dissolves anything. It is the universal solvent."

"Marvelous!" gasped the two sane scientists.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.