Cassell's edition of "A Moment's Madness," December 1908

He had been away nearer a year than six months; he returned to his little court improved by his travels, his dignity softened by the air of a man who knows the world, his hair dressed after the fashion of Paris, his speech adorned with delicate allusions to kings and queens; he brought with him an English valet, a set of diamonds presented to him by the Doge of Venice (these the most notable among other gifts), and the affectation of French.

Hesse-Homburg approved.

A principality as small as this that his Serene Highness ruled over is apt to be unduly proud; the castle of Hesse-Homburg was built after the plan of Marli or Meudon, the gardens laid out in the manner of Versailles; etiquette was supreme, the court complete from the Lord Chancellor to the black pages; Mr. Denton, the English valet, was reminded, on his arrival, of a performance of opera-bouffe where all the comedians appear as nobles and there is no one left to represent the citizens, so that the King and his train constitute the kingdom. Indeed, Mr. Denton had seen estates in England that would have divided between them two countries the size of Hesse-Homburg, but his admirable discretion allowed no hint of his discernment to appear.

There was a ball given in honour of his Serene Highness's return; the fountains played and coloured lights swung in the trees; ladies and gentlemen were painted, perfumed, pomaded, and laced into brocaded clothes; there was an orchestra of French fiddles on one of the castle terraces, and dancing in the long hall hung with portraits of the Prince-Electors of Hesse-Homburg.

The moonlight lay over gardens and castle like the enchantment of a fairy tale; Prince Frederic George, the Elector's brother, found it dangerous in conjunction with the low appeal of the violins; the time of year was the turning point of spring into summer, and the scent of carnations and roses stirred the air; the fountains, pretty even to those who had been to Paris, were to Prince Frederic George magical in their silver rise and fall against the wet foliage that drooped over their basins. He was staring at them when his Serene Highness touched him on the shoulder.

"Now, I am at last at leisure," said that gentleman with a kind of frozen amiability. "Let us, Frederic, talk together."

His brother bowed.

"Monseigneur."

They moved away from the fountains to a low seat under the laurels; the fiddles sounded in the distance, the plash of the water and a One rustle in the thick leaves; Prince Frederic George looked at his Serene Highness.

The Prince Elector was of a natural elegance schooled into artificial graces; his face was delicate, fair and faintly coloured, of a considerable hardness in the expression. At this particular moment he held his cane loosely in his long white fingers, and the blue tassels hanging from it swept his knee.

"Now, in my absence," he said, "how have you employed the time?"

Prince Frederic George sat stiffly, by reason of his buckram coat and the folds of black velvet round his throat; he leant forward, slowly, resting a hand on each knee.

"I have something to ask you, Monseigneur," he said, and coloured hotly in a way that annoyed his Serene Highness, who, even by this light, could perceive it.

"It is of great importance;" Prince Frederic George began again, and again stopped.

"Of what nature?" questioned his brother coldly.

There was a stir of satin as Prince Frederic George moved, and taking courage from the violins, the moonlight, and the scents of the flowers, spoke:

"I love a lady," he said bluntly, "who, I think—" He checked himself, and his fierce blush deepened.

The Prince Elector's china blue eyes were cruelly unsympathetic.

"Ah?" he answered. "Did Von Halzburg tell you of my approaching marriage?"

"No, Monseigneur." His brother looked startled.

"We have kept it secret"—the other deigned a hard, sweet smile—"until it was finally arranged. Of course, the country was expecting it—"

"Of course," said Prince Frederic George. He felt in a delicate way that it had become still more difficult to speak to his immovable brother now.

"Who is it?" He raised the dark, honest eyes that were at such variance with his foppish dress.

"I decided on a lady not unknown to you," answered his Serene Highness. "One who satisfies me with regard to fortune, person, and rank, our neighbour's daughter, the Princess Sophia Carola of Strelitz-Homburg."

The violins were hushed, leaving the fall of the fountains to sound more clearly in the stillness.

The Prince Elector felt the sudden sense of a chill, of unaccountable discomfiture. He looked at his brother, a motionless, half-seen figure in the shade of the laurels.

"And you?" he questioned.

Prince Frederic George put his hand out along the seat, and clenched the smooth edge of the marble.

"It is of no matter for me," he said dully.

His Serene Highness lifted his shoulders.

"As you please. Your love affairs—"

The other caught him up with unceremonious quickness.

"My love affairs!" His emphasis implied that the expression was blasphemy; then he lowered his voice again. "Your pardon, Monseigneur, I have no love affairs."

The Prince Elector smiled; he was in no way interested. The violins began a prelude to the dance, a throbbing invitation that came trembling through the moon-cloaked flowers.

"You intend to stay at Hesse-Homburg?" asked his Serene Highness. He turned his smooth face towards his brother.

"What else?" the answer came from the thick shadows, quiet, a little bewildered.

The Prince Elector explained. There was very little, he said, for a younger son to do at home; abroad there were chances.

"Yes?" assented Prince Frederic George. "Of what, Monseigneur?"

"Of advancement." His Serene Highness spoke drily. "Here there can be nothing."

The sense of dislike, of antipathy between them, seemed to loom, suddenly tremendous, like a tangible presence; they had always jarred on one another—never in such a fashion as to-night and now.

"There are opportunities in Paris," said the Prince Elector, "in London, in Vienna—"

"And Hesse-Homburg is small for both of us," put in his brother. "Is not that what you would say?"

His Serene Highness fondled the ribbons on his cane, and explained further, with the same even politeness, with the same hard eyes coldly stressing his words.

He spoke of what he intended with his kingdoms, of the advantage of the match with the heiress of Strelitz-Homburg, of his chancellor Von Halzburg, of new appointments; he spoke at some length, always quietly.

Prince Frederic George was not listening. When his brother ceased speaking, he turned with a weary slowness.

"I shall stay in Hesse-Homburg, Monseigneur."

A fine flush rose in the Prince Elector's cheek.

"As you wish," he said quickly.

"Your Highness can find some appointment for me?"

His brother would give no more than: "I will speak to Von Halzburg."

Prince Frederic George rose at this, bowed, and turned off down the well-set parterre, his hat in his hand. The Prince Elector looked after him with narrowed eyes, knowing that he hated him and not knowing why.

Prince Frederic George walked towards the castle and the music of the violins. Such an extraordinary and terrible thing had been contained in his brother's brief words that he felt that the world had been altered by it.

Sophia Carola was the betrothed of the Prince Elector; the elder was to have everything, even that, and for him there was nothing but silence.

He walked up the steps and along the marble terrace, and, lifting his eyes, gazed into the mystic landscape that fell away beneath the glamour of the moon into unfathomable distances.

He had never spoken to the Princess, nor to any other, of this deep secret of his; now, he never could. He did not question his brother's right nor his own helplessness; the etiquette, the formal courtliness inborn and inbred made him accept his fortune quietly with no more than a curious wonder at the pain in his heart, more intolerable than he could have believed possible.

He walked up and down the terrace aimlessly, taking no heed of the people who passed him; they seemed to him like visions of the moonlight that he could put his hand through, such an unreality had come over the world.

Presently he went in, avoided instinctively the rooms where they were dancing, and turned into a little circular antechamber softly lit with candles. The walls were painted with a gilt trellis through which roses climbed; the high ceiling was covered with pale pink clouds; in one corner, a sconce of candles either side, stood a gold bracket bearing a cupid, by Pigalle; behind it was a mirror.

The Prince leant lifelessly against the wall, his soul as bound by conventions and the ceremonies of his position as his body was disguised by brocaded clothes and his face by powder and patches.

The mirror reflected his slack figure in the stiff pink satin, his handsome face under the rolled grey curls, his hands either side of him resting against the white and gold wall.

He was neither thinking nor lamenting; apathy had mastered him. When he raised his eyes to the Cupid, it had no meaning for him. He heard through the half-open door the sound of a distant music and voices, faint like echoes; he turned his head, and noticed dully the window open into the night and the setting moon. After a while he was aware of people entering the adjoining chamber, but he did not change his position. He heard a lady sing in a fine low voice. Harp and lute accompanied her. Presently he caught her words rising with the music:

"When shall the morning come again?

(Haste while the sun is high!)

Sumner gilds the heavy grain.

And the lark hangs in the sky.

"When shall the morning some again?

'Tis only once for churls and kings.

Present joy's worth after pain,

And youth is heir of many things."

The Prince moved from the wall, his check flushed, his lips stirred; he listened with his soul in his dark eyes.

"When shall the morning come again?

The sun once set shall rise no more.

So short a time to lose or gain.

Haste, ere the first glow shall be o'er."

The Prince looked at Pigalle's Cupid, at his own face mirrored behind it, and his breath came unevenly.

"When shall the morning come again?

This day, this day alone is thine.

Up—for thy little space to reign,

Ere Death shall say, 'The night is mine'"

The song ceased; the Prince went to the window and held back the rose silk curtain.

The setting moon was showing in bars and gleams of silver behind the pine trees, and In the cast a slow pearl colour flushed the luminous sky. There was a sound of birds waking in the thick leaves, and the steady fall of the distant fountain.

"When shall the morning come again?"

"The morning!" It was his heritage, his right; he was young; it was his hour, his chance; his horse waited in the stable, she lived only a few miles away—what was there to keep him?

The once so potent reasons seemed follies now. What were his brother, the formalities, the conventions of the Court? Life was an adventure, a romance, and this day slowly breaking—his. He let the curtain fall; Pigalle's Cupid seemed smiling now; he left the antechamber.

The rooms were empty, save for the tired servants putting out the candles. They stared to see the Prince still up, but he was only aware that the dawn shone brighter through every window that he passed.

When he reached the hall he called one of the men, wearily carrying in the chairs from the terrace.

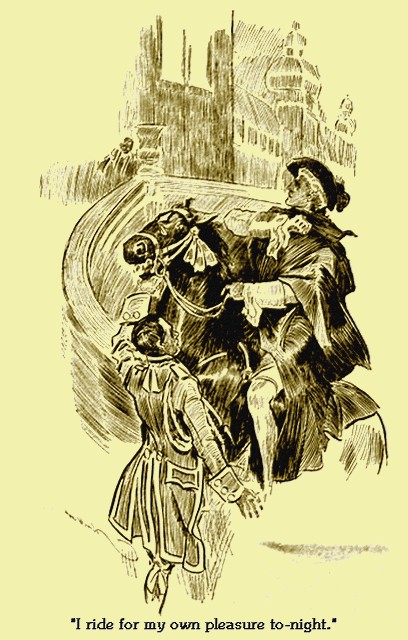

"See that my horse be brought here—quickly."

His masterful manner enforced his extraordinary command; he cared nothing what they thought of him, nor what tales were carried to his brother. He sent one of the sleepy black pages to fetch hat and cloak, and waited, leaning on the balustrade, looking into the garden. When he heard his horse's hoofs clatter on the pathway his heart gave a great bound; he put over his ball dress the cloak the negro brought, flung on the hat, and descended the wide, shining steps. The man there helped him to mount, then waited with a hesitating look.

The Prince glanced at the castle; there was a light in his brother's room; beholding it, triumph, hatred, exaltation fired his blood.

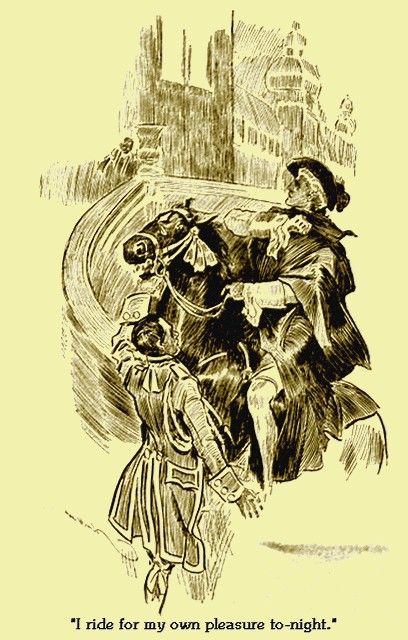

"Any message for his Serene Highness?" asked the servant.

"None," answered the Prince, still looking at the light in the window. "I ride for my own pleasure to-night. If the Elector question you, tell him that—"

He put spurs to his horse; with no backward look at the castle, but with ardent eyes on the marvellous dawn ahead of him, all flaming opal now, he rode through the park into the open country, and took the long white high road to Strelitz-Homburg. And he sang under his breath:

"When shall the morning come again?

Tis only once for churls or kings;

Present joy's worth future pain.

And youth is heir of many things."

It had been a perfect day: gold and blue from the first lift of the sun till this moment, when it neared the west. The hours had been full of enchantment for the Prince. He rode now down a quiet little village, and stopped at an inn, where he was an object of much wonderment.

The gathered rustics saw a gentleman with an air of wild gaiety dismounting from a noble brown horse; his hair was almost shaken free from powder, and he wore no hat (having flung it disdainfully aside as he rode through the tempered sunshine of the glorious woods); his cloak, of an exquisite blue colour, showed satins beneath; the rustics marked the knots of gold ribbon at his knee, the red-heeled shoes he wore—and scented an adventure.

The Prince, on his side, saw a low, thatched house with long shadows slanting under the caves, and the swallows in a row on the signpost. He entered the parlour, that looked over the great garden behind, and found it sweet beyond words.

The walls were white, the ceiling was low; a great brown clock, curiously carved, ticked loudly; there was a long shelf filled with tankards and bright glittering glasses; huge deep chairs, their wooden arms polished with much use, stood about, cushioned in faded velvets. The window, with its diamond pane of thick greenish glass, was set wide, and the tall pinks nodded against the wide sill.

A romance indeed!—and this, the fitting resting-place after a ride through fairyland. The Prince had not found ever anything so beautiful as he found this place. He went to the window; he saw a multitude of flowers that he did not know the names of, beyond the frail blossoms of apple trees, and beyond them the towers of the Castle of Strelitz-Homburg.

He had crossed the borders; he was in her country.

Presently he went out into the garden, and walked slowly, quiet with happiness, among the flowers. Hesse-Homburg and his brother were in another world. In his incongruous ball dress, with his cloak falling from his shoulders and his bright hair for once unloosed, he wandered among the uneven paths, looking at the flowers, stooping now and then to lift their heads in his hands. Once he brought his lips to the open roses.

At the end of the garden was a row of beehives; behind them a wooden paling shut off the orchard. A few white sheep rested under the apple trees, and the fallen blossoms lay delicately on the tall grass.

The Prince looked beyond this to her castle walls.

"When shall the morning come again?

'Tis only once for churls or kings.

Present joy's worth future pain,

And youth is heir of many things."

He would not let his May of life slip, he would not live to say, "Once I might have gone to her and put my fortune to the test, but I was afraid."

Slowly through the flowers he went back, and because of something in his face they served him silently, though they wondered who this was that rode in dancing shoes and bore himself so carelessly.

He took his meal alone in the low, fragrant parlour. The clock struck five in deep tones, a tortoiseshell cat jumped in at the window and rubbed itself against one of the empty chairs; a murmur of voices came softly through the half-open door.

The Prince ate a little of the fresh white bread they brought him, then rose and shook out his hair afresh, and tied it with its long black ribbon. As he did this his cloak slipped and fell to the ground, and he stood revealed in his glimmering rose pink, with a great knot of dull crimson on one shoulder. The diamonds winked in his sword-hilt and in the brooch under his radiant face.

The little fair-haired maid entered, and stood amazed. He turned with a sudden smile, and asked for some of the roses from the garden, and that his horse might be saddled. Her blue eyes widened.

"Have you run away?" she asked.

"Yes," said the Prince, "I have run away."

"It is like a fairy tale," she answered. She picked up his cloak timidly, and gave it to him; then she was gone, light of foot, and he saw her pass the window, her plaits gleaming in the still sunshine. She came to his saddle bow when he had mounted with her hands full of flowers, and he rode away with her gifts of roses, white, pink, and red, tied with his handkerchief and hanging to his pommel.

The way lay first through a little pine wood, then a narrow lane bordered with fields of young wheat winding into open meadow land, where the hawthorn was wonderful, and so at last into a broad white road with the castle gates and their guardian lions majestic ahead.

He rode up to the entrance and past it to where the wall rose only to his horse's knees, and he could look over it and behold the sweeping park land beyond. And in the first glance he gave through the trees he saw her.

She was with a company of ladies coming slowly down a shaded glade. She wore a lemon-coloured silk; she was not very near, but he knew her at once, even though her face was hidden.

He dismounted, fastened the reins to a bough of a beech tree, and vaulted over the wall. For a moment he stood with his hand on his heart, looking at her across the long, level shadows and fading sunshine; then, as if he had called her, she turned from the others and came slowly towards him.

He had not been daunted by the difficulties of his adventure, nor was he surprised by the ending to it—he found it only natural that she should come as if she knew he waited.

He watched the little group of ladies disperse in the distance, and marked how the sunlight flickered through the leaves on her dress. She seemed to be in deep thought; her wide straw hat shadowed her face, and thy green ribbons on it fluttered idly on her shoulders.

"Carola," said the Prince.

She stopped instantly and looked up; her hands, that had been locked behind her, fell apart.

"Oh!" she exclaimed, and she looked at him blankly.

Her exquisite fair face held no expression; she seemed not to know him. The Prince laughed.

"Carola!" he said again, and came towards her.

"Your—your Highness," she stammered. She stood motionless, fixing him with her beautiful eyes. He saw a miniature of his brother hanging on a chain round her long white throat, and it sent the blood into his face.

"You know why I am here," he said. "To take you away. I have ridden all day—all day. God let me find you." He stepped up to her in a tumult of feeling. "I love you utterly."

Never moving, and with no change in her face, she answered him:

"You have heard of my betrothal?"

"It is why I am here, Carola."

She moved away, still with her eyes on him, and put her hand out against the smooth bole of the beech tree near. The last sunlight filtering through the foliage crept round her gleaming bodice and slender waist and lay in the folds of her long silk skirt. The Prince stood watching her, suddenly very pale.

"Don't you understand?" he asked.

"Your brother," she said. "You—your Highness—"

"I have not come to speak of him," he answered. "What is he to us?—it is our day and our chance. I have thought you cared—I have known you cared."

"For you?" she cried, and shrank against the tree.

"For me," he answered. "I have come for you."

"Oh, what have I done?" she said softly. "What have I done?"

"You have made me love you. Are you sorry for it, Carola?"

He held out his hand; the light MI full on his disordered hair, his pale face, his tumbled dress, his intense eyes.

"It will be for always," he said between his quick breaths. "For all our lives. We have this moment only—take that thing from above your heart, and come with me."

"You hate him?" she whispered.

"Yes, I hate him—and you—you do not love him. We have had enough of lies. This morning in the dawn I saw the truth, and came to find you; the day has been paradise because it held the promise of this moment. Why don't you answer me?"

"You speak madness," she said. "I must not listen. Go back. If they discovered—"

"I have told you that I love you," he answered passionately. "Can you think of anything else?" And then the mood, the impulse that had brought him, found vent in wild words; yet true words, eloquent and from the heart. He spoke of their cramped life, he laughed at the laws and conventions that bound then both, he set his teeth at his brother's name, he entreated her, he conjured her to listen to him—"in the name of God before it is too late."

She made no attempt to interrupt. Her great bewildered eyes were fixed on him, her colourless face did not change; mute, with parted lips, she listened. He stepped before her at last. The moment of supreme crisis had arrived.

"What are you going to say?" he asked hoarsely.

He waited, and, so intent were they with one another, they did not see a lady coming silently across the grass toward them.

"Why are you silent?" he asked again.

She made a little movement, turned her head, and gave a low cry of terror.

The lady had reached them; she looked from one to the other, and there was silence. It was the Margravine; the Prince returned her gaze defiantly.

She looked at him, at his loosened hair and pale features, at his court dress, dishevelled with riding; she looked at her daughter very sharply, and her eyes narrowed.

"What is the explanation?" she asked quietly.

She was a gaunt woman, handsome, hard-eyed, and large of make; etiquette was her god; it was known she could be terrible.

The young Prince faced her with loathing in his bearing; it was she who had contrived her daughter's marriage.

"Madam, you can see," he said. "I want your daughter for my wife. I have come from Hesse-Homburg to fetch her."

Again her shrewd eyes measured him.

"You are daring," she remarked. "Carola is promised to your brother."

"But I love her," he answered her sternly; "and before God, he shall not have her."

The Margravine turned to her daughter. "And you?"

The Princess shivered. "Go back," she said to the Prince. "It is—it is impossible."

"My daughter shows some wisdom." The Margravine spoke with a cold smile. "Go back to Hesse-Homburg, your Highness."

He turned on her passionately.

"No, she shall come with me."

Sudden wrath flashed in the Margravine's eyes.

"Where? Who are you, a younger son, to woo your brother's betrothed? What can you give your wife?"

The colour rushed to his check as though she had struck it. This had not occurred to him; no practical matters had disturbed the dream that had brought him here.

"My daughter is your brother's betrothed," said the Margravine steadily. "Had she been free, I should have called you mad to forget her dignity and yours as you are doing now, to come here like this." She pointed a scornful finger at his dress. "To assail a princess with the language of a lovesick page. Take such homage, sir, to a lady who is free and of a lower birth."

He stared at her, unable to find words. At the agony in his eyes her colour rose a little.

"Come!" she said more kindly. "This is a boy's fairy-tale romance. Love"—and she lifted her shoulders—"where will love take you, my friend? It would make outcasts of both of you, marry you under a hedge, house you in a ditch, bring you to what? I think your Highness has not thought seriously of what you would offer my daughter."

The Prince spoke very faintly.

"In truth, madam, I have been mad."

Things in a moment had changed. The Margravine had swept away like cobwebs his romantic visions. He felt sick and ashamed before her scorn.

"I have been mad," he repeated.

She watched him keenly, not sure whether he were still dangerous or no—smiled dubiously.

"Go back to Hesse-Homburg," she said, "before there is any question. We wish for no scandal, my friend."

He flushed at that, and fixed his mournful eyes on the Princess. "Neither your daughter nor anyone knew of my coming, madam."

The Margravine laughed good-humouredly now. She was pleased with her success.

"Oh, I understand."

"You have cured me, madam," he answered her quickly. "I have to ask your pardon for my folly."

He looked at the princess. Save for that one broken appeal to him to go she had neither moved nor spoken since her mother came. She leant against the beech, her terrified eyes always on him, her hands clenched at her side.

"God make you more fortunate than I have been," he said unsteadily.

She came a step forward. The Margravine was between them instantly, and spoke to him with her hand on her daughter's wrist.

"Your Highness, I have been lenient to a most extraordinary degree," she said rapidly. "I shall forget it, I shall speak of it to none."

He read the threat, the command in her eyes.

"I am going," he answered. "You have taught me to remember the wretched beings we are, madam, and our paltry laws." He lifted his tragic young face and looked at the setting sun. He thought of the metaphor of the song. "The day is over," he said bitterly. "Madam, good-night."

The Margravine felt her daughter's hand quiver, and her clasp on it tightened.

"Good-night," she answered. "We must all some time be a little foolish."

The Prince leaped the wall, and went up to his horse. The two women watched from under the trees, and saw him untie the bunch of roses at the saddle. He turned his head and looked at the Princess with a wild smile; then cast the flowers on the ground, mounted, and rode over them away into the soft twilight.

The Princess made a little sound in her throat. Her mother turned to her.

"I did not know that you had this fiery lover."

"Let go of my hand, madam," she answered wildly.

"Oh! are you mad also? Are you not thankful that I came to save you from this boy's folly?"

The Princess wrenched her hand free.

"God forgive you," she murmured, and wrung her fingers together. "You have sent him away. What have you done? He is gone!"

"And you lament it," cried the Margravine, her eyes flashing. "I shall think this was not chance."

The girl turned on her mother, suddenly animated and flushed.

"It was," she cried, "my chance. Do you know what he offered me? And I was a coward."

She tore the Prince Elector's picture from the chain round her throat, and hurled it into the long grass.

"Oh! mother, what have you done?"

"Hush!" The Margravine caught her by the arm. "Do you want me to be silent? If you behave like a fool I must speak to the Prince Elector; he will not be tender with either of you."

The Princess shuddered, and put her hand to her eyes. "I will be quiet."

The Margravine picked up the miniature from the grass.

"You have broken the chain," she said. "Come in, it is nearly dark."

The Princess allowed herself to be led away. She said no more, gave no sigh nor backward look.

That evening she wrote a letter, and sent it away secretly.

A cascade was being constructed in the gardens of the castle at Hesse-Homburg. His Serene Highness had seen such an ornament on has travels, and under his personal direction the workmen piled the smooth slabs of rock one upon the other, sloped away the bank, and dug the ground for the basin into which the water was to fall.

It was at the end of a box-edged walk, and would be, when complete, a fair imitation of the original in France. The water conducted from a neighbouring stream was to fall over the rocks a height of eighty feet and plash into a vast fern-grown basin; a winding path was to lead gradually up the bank against which the rocks were set, so that the summit of the cascade could be reached. There was to be a little temple there, furnished with a seat and shaded with trees, so that it would be possible to sit and look down on the water's straight descent and the swirl in the pool below.

The work was expensive and difficult. The Prince Elector marked with pleasure how well it slowly progressed. He came every day and stood for a while watching the men at their labour; often, he said nothing, but stood with his cane under his arm, fondling the ribbons on it, as his habit was; but the men worked the better for his keen eyes upon them.

To-day he spoke: "You will have it finished for my wedding?"

The head mason answered him: "Yes." The Prince Elector passed on down the trim walks, his long fingers playing with the red tassles on his cane, and arrogant satisfaction showed in his contained face; he was pleased with himself and with his world.

Before he had reached the orangery he met Von Halzburg, his chancellor, and the two paced up and down together, discussing the affairs of Hesse-Homburg. On their parting, the Prince Elector returned slowly in the direction of the castle, and perceived Mr. Denton coming obviously in search of him.

It was drawing near to evening, and cool and pleasant in the gardens. The Prince Elector seated himself leisurely on a bench near the fountains, and waited for Mr. Denton to come up to him. It had been raining that day, and the trees and flowers were fragrantly wet and fresh. His Serene Highness marked with approval the pleasant flutter of the leaves against the paling sky. Mr. Denton approached with his noiseless step. The Prince Elector, turning from contemplation of the sunset through the foliage, rested his clear gaze on the valet.

"Have you seen his Highness my brother?" he asked.

"He has just returned, sir."

The Prince Elector's delicate brows frowned.

"He did not say where he had been?"

In a subtle way his manner implied his sense of something extraordinary in this behaviour of his brother; in a subtle way Mr. Denton made light of it in his reply.

"No, sir; he did not think it of enough importance."

The master gave him a quick glance, but the Englishman's quiet, alert face told him nothing.

"I have a letter for you, sir," said Mr. Denton.

"One of the servants of the castle of Strelitz-Homburg desired me to give it to you immediately."

He handed the Prince Elector a scaled packet, and awaited his orders.

"From whom is this?" asked the Prince—he did not know the writing.

"The man did not say, sir; only that it is secret and immediate."

His Serene Highness frowned; he disliked informality or any hint of the mysterious.

"There is an answer wanted?" He lingered over the breaking of the seals.

"I do not know, sir; the messenger has returned."

"Very well." The Prince made a motion of dismissal; Mr. Denton bowed and left.

His Serene Highness handled the letter a moment, opened it slowly, and glanced at the signature. It was from the Princess Sophia Carola. There were only a few lines, all in her own hand. As the Prince read them a curious hardness came over his face, his lips tightened, and his eyes shone unpleasantly.

But he folded the letter quietly, put it in his pocket, and began to walk up and down in front of the fountains.

The placid evening faded into twilight, the bats came out and circled round the bushes, in the windows of the castle small yellow lights appeared; still the Prince Elector walked to and fro, his eyes downcast, his mouth set sternly. Suddenly, as he turned, a man stepped out from the shadow of the laurels, and he found himself face to face with his brother.

For a second a spasm of hatred crossed his face and his eyes flashed aide, then they narrowed again, and he spoke quietly.

"So—you have returned?"

Prince Frederic George, correctly dressed, pomaded and powdered, raised his hat, and was turning off without a word when his brother stopped him.

"Where have you been?"

The younger man flushed slowly and swung round on his heel so that he faced the other.

"Where does your Highness please to think I have been?" he demanded.

There was a direct challenge in his words, a recklessness in his bearing of how that challenge might he answered. The Prince Elector clenched his hands on the red-tasseled cane.

"Perhaps I know," he said; "perhaps, also, I want to hear the tale you will tell me."

"I owe you no explanation," answered Prince Frederic George. "I am free to ride where I will—that much at least is owing, even to a younger son."

"While you are at my court you obey me."

"Had I your commands to stay in Hesse-Homburg?" flashed the other.

They stood very close together against the dark, rustling laurels.

"For two nights," said the Prince Elector, "you have not slept at home. You must have ridden out as you were—in your ball dress, without servants. You made yourself a matter of comment to my people—"

His brother interrupted hotly.

"What are your people to me? I did as I wished, and am responsible to no man."

His Serene Highness was very white. He moistened his lips, and pressed his handkerchief to them.

"Take care what you say," he answered in a low voice.

Something in his tone stung Prince Frederic George into open wrath; his sore heart and galled spirit could endure no more.

"I'll not choose my words to you!" he cried, and his dark eyes gleamed dangerously.

"You young fool!" His Serene highness lifted a face showing livid in the twilight. "You'll answer me civilly, and you will choose your words—yea, and your actions, too."

"Neither one nor the other," panted the other, rigid with anger. "What have you ever done for me that I should consider you?"

"Where did you ride from, yesterday?" asked the Prince Elector. "Answer me that!"

His brother laughed recklessly.

"By Heaven, I will not!"

"It was to Strelitz-Homburg."

"Well, if it were?"

His Serene Highness stepped back from him.

"Do you deny it?" he asked through drawn lips.

"Why should I?" The blood flamed in Prince Frederic's face, but he held his head proudly high. "Yes; whatever spy you have had at work told you right. I rode from Strelitz-Homburg."

The Prince Elector flung out his hand, caught some of the laurel leaves, and crushed them in his cold fingers. It symbolised his arrogance.

"And whom did you go to see?" he asked in a quivering voice.

His brother flung defiance at him.

"Since you know—do you think I am to be trapped into lying?"

"I think that you will not be bold enough to tell me the truth," breathed the Prince Elector.

Prince Frederic laughed.

"The truth! What have we to do with the truth? We live shams and act lies. Let the truth go, your Highness."

The elder man held in his passion with a painful effort.

"You dare me very far. Will you dare to tell me that you went to see my betrothed wife?"

Prince Frederic George drew back against the laurels; his eyes narrowed.

"So—who told you? Yes; if you wish to make words about her name. That is the truth for you. I went to see her."

"This to my face!"

"This to your face. Who told you?"

The Prince Elector put a shaking hand over the pocket where the letter lay.

"The Margravine wrote to me." He watched the effect of his lie.

Pale with scorn of all of them, Prince Frederic George flung up his head.

"She spoke me false, then. Well, it is over now. What are you goading me for?"

"I am going to discover the truth," breathed the Prince Elector.

"The truth!" Again his brother flung the word at him contemptuously. "Am I to bare my soul to feed your scorn? You can guess the truth."

"You love her," said the Prince Elector in a still voice. "Well, I do not, but she is to be my wife. Do I put it plainly?"

"You put it like the cold devil you are!" cried the other. "What right have you to use these words? What right—"

The Prince Elector interrupted, with a flash of vehemence:

"How far has this gone between you and her? Enough of your heroics. Answer me that—do you think "—he drew a sharp breath—"that she favours you?"

"Oh! be satisfied," answered Prince Frederic George wildly. "She had been mounted on my horse, and we both of us miles across the borders, if she—But I will not talk of her to you. I say it is over. Will you still goad me?"

His Serene Highness withdrew his hand from the letter in his pocket. He had discovered what he wished to know. His forehead was damp, his lips dry and trembling, but his eyes flashed triumphantly.

"Why, I can smile at your madness," he said steadily. "If by your own confession, she carts nothing, you tease wasted your knight-errantry and your love-making."

His brother caught him by the shoulder with sudden force.

"Be silent." he commanded hastily. "Don't you see? don't you understand? You drive me to violence."

The Prince Elector felt himself overpowered: his brother was by far the stronger man. Still, he did not move nor abate his mocking tone.

"I always knew you were a fool; but you will keep your folly from my affairs. Take your hands off me."

Prince Frederic George saw the furious eyes of the man he held gleaming at him, and he let go his hold suddenly, afraid of himself.

"And I," he said hoarsely. "I always hated you and your pasteboard royalty! By God! had you not been the elder, you had not flouted me now, I could have won her—ay, and kept her. I am as fine a gentleman as you, had you taken your chances fairly. Oh I I loathe your shams and pretences, your empty titles and tea-cup kingdoms. Let me go before I prove on your body who is the better man."

Every word of the poor mute letter lying in his packet rose red before the Prince Elector's eyes. He put his hand instinctively over it again, as if afraid that it might proclaim aloud the lie he was acting.

"You will leave Hesse-Homburg," he said passionately. "You will go to France—to Rome—to hell, so that I will not see your face again."

"Are you afraid of me?" answered his brother proudly. There was a sound of the rustling laurels as he crushed back against them.

"I have had enough of you for what you have done to-day. I will never forgive you This is an end of it between us!"

Through the deepening dark that divided them Prince Frederic George answered:

"Do you think I would stay to see her cross your threshold? Do not fear that I shall mar your festival. You have made this spot cursed to me. God give you joy of your choice, my brother!"

With a firm step he turned away. The Prince Elector saw his tall, indistinct figure pass before the dark laurel edge and disappear behind the fountains. Alone in the dark and the silence, his Serene Highness could not restrain a sound of rage and bitterness. With shaking fingers he pulled out the Princess's letter, and his eyes grew evil as he stared at it—a white blur in the twilight.

The Prince Elector was at Strelitz-Homburg to fetch his wife. The Margrave gave a ball to celebrate his daughter's betrothal, and in the Hall of Mirrors his Serene Highness met the Princess alone for the first time.

He had been talking with the Margravine; it was before the ball had begun, and the room was empty when he entered it. As he crossed the polished floor his own white satin-clad figure was reflected to right and left of him in the mirrors. Only a few candles as yet were lit—the light was soft and pleasant, the place very still. The Prince Elector gave a little start as he saw her enter, and close the door behind her. Yet he had known that this moment must come, he had been sure that she must seek him out and speak. He had her letter in his pocket, and his answer ready.

The Princess came slowly down the room and crossed to a gilt settee placed in a corner. He, looking at her, could for the moment think of nothing but her beauty. She wore a dress of a deep rose-pink, cut very low, and heavy with gold embroidery; her fair, smooth shoulders were reflected in the mirror behind her; in her piled-up, powdered hair was a great white rose. She held a fan of white feathers that she waved slowly to and fro, and her gorgeous blue eyes were intent on the Prince Elector.

"Your Highness," she said in a low voice; "did you receive my letter?"

He had been at Strelitz-Homburg four days, and had not passed more than a few formal words with her in the presence of others. Her question, expected as it was, gave him a curious shock; it angered him, too, more than he had thought it would.

"Yes, madam," he answered.

She dropped the feather fan into her lap.

"Have you a reply to it?" she asked. "I have been waiting."

His anger grew unaccountably, for her bearing was gentle and she was putting so obvious an effort on herself to speak at all that it should have moved his pity. But her very bright fairness and beauty, repeated by the mirrors about him, stirred him to cruelty.

"Yes; I have an answer," he said. "What do you think it is?"

A delicate colour came into her face.

"I—I have hopes," she said simply.

His fine nostrils distended. He crossed the room to the side of her gilt settee.

"Of what, madam?" he asked quietly.

She leant forward, breathing fragrance.

"That you will not do this great wrong to me—who have done no wrong to you, your Highness."

He thought of his brother's handsome face, and could not trust himself to speak.

The Princess gave him a trembling smile, with hope written on it.

"Ah! You will have thought me bold and strange—but I had no hope save in your generosity."

He was still silent.

"We are almost strangers, your Highness." Her sweet voice was very low. "While you were away I saw so much of him. I—but he never spoke to me. I did not know—until he came."

"Ah! until he came," said the Prince Elector softly. Her great eyes grew apprehensive.

"I should never have dared; but he told me—I saw it all, then I thought you would set me free." She laid her hand pleadingly on his satin sleeve. "Your Highness, your Highness, what am I to be to you—and to him?"

He stepped back, lifting his hand to the lace on his breast, and with cruel eyes fixed on her appealing fairness.

"I have your answer." He pulled a paper from his bosom.

She rose expectant, trembling between hope and fear, and clasped the back of the settee. Against the wall, behind the Prince Elector, was a sconce of candles. He turned to them, and she saw her writing on the paper in his hand. With a little quiver of dread she realised that it was her letter he held. As she watched, he twisted it up, thrust it into one of the candles, cast it flaming on the ground, and set his heel on it.

"That is your answer," he said, looking at her over his shoulder.

She went piteously pale, but her eyes were dark and brilliant.

"Which means?" she asked.

"Which means that what you wrote there and what you have said since is alike folly we had best forget, madam."

The Princess moved from the couch and took a few swift paces down the room.

"You have not understood me," she said in a bewildered way.

"Do not put it any more clearly," he answered bitterly, "for, believe me, I understand."

"But it is not possible!" she cried. "You cannot be so cruel!"

His unflinching blue eyes chilled her speech. She came back to the couch and leant against it weakly.

"But I might have known," she said faintly.

His Serene Highness, swinging the diamond star that hung on his breast by a black ribbon, crossed over to her.

"I have been very patient," he said. "I can endure no more words on this subject."

She was still incredulous of his attitude.

"But do you—can you—realise what this means to me?" she asked, with her hand on her bosom.

He smiled grimly.

"I am not so obtuse, madam—and what of myself? Your talk insults me."

She moved away from him against the cold, shining mirrors.

"Insults you?" She pulled desperately at the feathers III her fan. "I never promised you anything—you know that. It was done for me. I only ask you to be merciful."

"And I, madam"—the Prince Elector raised his head and looked her straight in the eyes—"I desire you to be silent on this matter."

The Princess drew a sobbing breath.

"Do you want me to go on my knees to you? I—I—find it difficult to speak."

"I want you only to leave the subject, madam, lest you strain my tolerance too far."

"Your tolerance!" The word stung her through her pain. "What manner of man are you to speak so to me?"

"The man who is to be your master, at least, madam." His anger was fast overmastering him; his delicate face was drawn and hard.

"Ah! You have little tenderness for me!" she cried in pain and wonder.

"It is enough that I have chosen you for my wife. It is enough that I will forgive your moment's madness!"

"Forgive!" she echoed. "I think, your Highness, that I will not forgive you!"

She sank on the couch, for she trembled so that she could not stand, and caught at the arm with nervous fingers, while her accusing eyes faced him. He shrunk under their accusation.

"I would not treat the meanest thing in my power as you are treating me," she said wildly.

Suddenly he turned on her, his fine, cold manner cast aside.

"I'll endure none of your schoolgirl airs and graces, madam. You do not know what you say. You have had my answer, and I will listen to no more."

Her anger rose to meet his.

"I know well enough what I say—and, to your shame, you know it too, Prince."

"Cease!" he cried hoarsely.

"I am not afraid. I always disliked you. I knew in my soul—I knew that I should appeal in vain."

She rose, shaking.

"Take care what you say to me," he said.

"I say this to you," she panted; "I love your brother—in these words I say it plainly to your face!"

"And I answer you, madam, that you will be my wife, notwithstanding. As for him—"

"What of him?" she broke in.

"He will not trouble us. I have sent him from Hesse-Homburg."

He saw the terror in her eyes, and he smiled unpleasantly.

"Gone? He—is gone?"

"Did you imagine that I was quite so accommodating?" he sneered. "He is gone, madam; and, while I live, he will not return!"

"Oh, God!" she cried.

She seemed utterly broken. She fell across the couch and sank into the cushions. Her breath, her very life, seemed to be struck out of her trembling body.

"Bah!" said his Serene Highness. "We have had enough of these fooleries." He bent over the settee. "Are you going to behave like a kitchen wench deprived of her swain?"

She sat up, armed with pride, and put her hands to her forehead.

"Oh! I shall learn my part in time, your Highness."

He drew back, pressed his handkerchief to his lips, and watched her as she struggled for self-control. It was pleasant to him to think of his brother riding away with an empty heart and an empty future, while she sat there vanquished, his—hating him, perhaps—but his.

After a little she turned to him and spoke in a steady voice: "I must ask your Highness to forgive me that I so far mistook you as to speak as I have done. I see very clearly my own folly."

"Ah, you do see reason now, madam."

"Oh, yes," she said. "I see reason now, your Highness."

"There is someone coming," said the Prince Elector. "They are bringing the music. You have nothing more to say to me, madam?"

Her intense eyes flashed over him.

"Nothing, your Highness."

He moved away to the window. He was more angered and shaken with this scene she had made than he cared to admit to himself, but it was balm to his wounded pride to think of Prince Frederic George wrapt in loneliness, picturing with a furious heart his brother's wedding festival, and not knowing where the bride's heart lay. Ah! there was the triumph his brother did not know.

The musicians came in one by one, carrying the harps, flutes, and violins. The room was lit, making it one glitter from end to end, every fiance reflected a dozen times.

The Margravine entered and spoke to her daughter. The guests arrived; the Princess received them gracefully. Her mother, sharp-eyed, could detect no confusion or distraction in her bearing.

She opened the ball with the Prince Elector. She had no word to give him as they walked through the minuet, and he felt her fingers cold as they touched his. But her frozen courtliness was all that was expected from her, and he was satisfied to have the thought of his brother, who did not know.

She danced half through the evening, then found an excuse to evade the gentleman who would have led her out, and escaped on to the balcony. She had no object in coaling here, save that her desperate heart might draw some comfort from the quiet; but she had a sudden inspiration as she saw Mr. Denton mounting the steps from the garden. She had noticed the man, and liked his quiet presence: it scented to her that he could be faithful. As he came along the balcony she leant forward and, on the impulse of her inspiration, spoke.

"Do you know where his Highness is—Prince Frederic George?" she said, and hardly knew that the words were formed before they had been uttered beyond recall.

Mr. Denton stopped instantly. The light falling through the open window of the ballroom revealed her pale and beautiful in her glimmering dress, her lovely eyes half-defiant, half-pleading.

"Do you know?" she repeated, and her tone was between fear and haughtiness.

"Yes, madam." He was immovable, respectful—the perfectly trained servant.

"He has left Hesse-Homburg?" asked the Princess, too proud to disguise her interest, speaking intensely, and with no affectation of indifference.

Mr. Denton replied as before:

"He left the castle at the same time as his Serene Highness, madam. He is staying now at Hartheim, while he makes ready to go abroad."

So—he lingered! He was still in the country—near—with what hopes, perhaps!

"Thank you," she said quietly.

Mr. Denton bowed and passed on.

At Hartheim, a village only a few miles away. She reached out her hands across the balcony, fired by the thought of his near presence, as he had been by hers when he rode out across the summer fields to find her.

His very name was on her lips, but she caught it back; the Prince Elector's soft footfall was behind, he stepped up to her side.

There was a curious silence between them. She would not speak to him, She put her fan to her lips, and stared across the dark garden. He pulled a leaf from the creeper on the stone and tore it delicately.

"Do you hate me?" he asked at last, smiling and bending a little closer. She half-turned to him.

"Was it not your wish," she said, "that we should speak of neither hate nor—love?"

The fragments of the torn leaf fluttered from his hand.

"For me," continued the Princess, "I shall be silent on these matters, for after all, your Highness," and her voice grew reckless, "what has it to do with us?"

"I am glad that you decide so," he answered. "Let us go in, madam."

She made a little motion with her hand unseen by him, as if she cast a message into the dark or waved a signal at Hartheim, a few miles away.

As she stepped into the candlelight she laughed.

Her ladies had put the Princess to bed and left her.

She lay very still, staring at the great round moon that hung in the square of the window. Then, when every sound in the palace was hushed, she rose very cautiously and lit a candle. By the pale light of it she saw her own face in the mirror and wondered, so strangely her fair eager features showed against the darkness of the background.

Quickly and noiselessly she dressed herself in the darkest clothes she could find, took the candle, and left the room.

She dared not think either of the joy or of the madness of what she did. Her whole being was strung to silence. She descended the stairs, light-footed, one cold hand on the wide, smooth rail; the other, holding steadily aloft the candle that cast a waving circle about her feet. As she passed the windows a great bar of moonlight lay across her path, and she took her breath fearfully, glad to escape into the darkness, with only her own little candle.

She reached the bottom of the stairs. Her straining eyes had seen nothing, her anxious cars caught no sound. She paused a moment to take her bearing; the place seemed so different in the dark, the very stillness confused her. The hall before her was glowing with moonlight falling through the tall window that bore the arms of her family, and the shadow of the dark shield was cast at her feet.

Her intention was to go through the ballroom and escape by one of the windows on to the balcony, so across the garden and park and out on the high road there where the wall was low.

She was about to move when the palace clock struck two, and she waited fearfully for the echoes to die away. But, before the last tremor of sound had vanished, a door near by unclosed and a man stepped out.

The Princess had the courage to repress the cry of dismay that rose to her lips, the courage to put out her candle and draw back into the shadow of the stairs. The man spoke:

"Is that you, madam?"

It was the voice of Mr. Denton. She realised, with a fainting spirit, that it must be the Prince Elector's room from which he came.

"His Highness is asleep, madam," said Mr. Denton, in his usual respectful ordinary tones.

At that she came forward a little. The moonlight showed her green laced hunting dress, her long curls tied in a knot at her neck, her snow-white face lit with her great wild eyes. Now that she was discovered she was quite calm.

"Have you been watching for me?" she demanded.

"Yes, madam."

"This is your master's doing." She made a desperate step in the direction of the ball-room door; quiet, respectful as always, Mr. Denton was in front of her.

"Your Highness is going to Hartheim?" he asked.

The Princess stood silent; her bosom rose and fell tempestuously, she looked at the ground, then she looked up.

"Yes, I am going to Hartheim."

It was in this man's power to prevent her, to rouse his master, but she would not stoop to lie or plead.

"Will you let me pass?" she panted, with a fair show of courage.

Mr. Denton bowed and opened the door for her.

"Have you a horse, madam?"

"No"—she glanced at his impassive presence in a bewildered way—"I?—no."

"Your Highness cannot walk four miles alone in the middle of the night," said Mr. Denton, speaking with great deference.

"I—I had not thought of it," she answered, the full difficulty and recklessness of her undertaking coming home to her. "There was no one I could trust," she added half to herself, "but I ant not afraid."

"I could get you a horse, madam," suggested Mr. Denton.

"You!" she exclaimed, "the Prince's servant!"

"I would always rather have served his brother, madam."

She stood silent for a moment, considering Mr. Denton, then she spoke:

"Very well, serve me now. It is the same thing, as you know, I think," she smiled proudly; "follow me to Hartheim."

As far as his manner ever showed anything, Mr. Denton showed pleasure that she had so quickly understood and trusted him.

"Yes, madam," he answered.

"You risk a great deal," she said curiously; "remember that."

"It is no matter at all, your Highness."

He followed her into the great deserted ball-room and deftly unfastened a window. The Princess stepped out into the moonlight and descended the steps into the garden; Mr. Denton fixed the window with noiseless precision and came down after her.

"Where can you get horses?" asked the Princess, standing among the rose bushes; "the stables are locked."

"If your Highness could walk across the park, there is a farmhouse on the high road where I could procure them."

"How?" she questioned.

Mr. Denton explained himself deferentially.

"I could say I had His Highness's orders to ride with important papers, and that he did not wish to rouse the palace for my horse. They know me, madam."

"Very well," she said, "where is this horse?"

"A few yards from the gates, madam."

"But they will be fastened," answered the Princess; "we must get over the wall where it is low and walk to the farm along the road."

She started across the moonlit garden at a quick pace, Mr. Denton a few steps behind. She had no sense now that she was doing a wild extraordinary thing, she hardly realised the strangeness of this foreign servant's devotion; her thoughts were all ahead of her body on the long, white road to Hartheim. They left the garden and entered the park. The great trees stood up huge and majestic against the silver sky; a group of delicate deer were browsing in the moonlight, and the hares fled through the long grass at their approach. It seemed to the Princess that they took hours to traverse the well-known glades, but as they reached the low wall she heard faintly the palace clock striking half-past two.

Out on the winding ribbon of the high road now, with the full moon hanging ahead of them, the Princess gathered up her skirts out of the thick white dust, and led the way along the park well in the direction of the great gates. On the other side of them was a low hedge full of sweetbrier and honeysuckle, making the air heavy with sweetness, and beyond that were young cornfields, a wondrous colour under the moon.

As they came near the gates the Princess saw facing than a farmhouse standing a little back from the road, in an orchard of pear trees.

"Is that it?" she whispered over her shoulder to Mr. Denton.

"Yes, madam."

"I remember," she answered. "They would know me; will you go up alone and try to get the horses?"

Mr. Denton bowed.

"I will wait here," said the Princess, and seated herself on the bank beneath the hedge.

She felt neither fear nor dread, but a great dreamy joy. It was beautiful to feel the soft grass and the tall wild flowers when she put out her hands, to smell the clover, the thyme, the roses, to see the dim fruit trees bending over the twisted fence, and the moon, cold, far away and pure, hanging above them. It was glorious to think of riding through the wonderful night, framing as she went the words that were to blot out her tongue-tied silence.

She heard the sound of the gate in the fence opening and Mr. Denton's steps up the path, then his loud knock on the door. There was a pause; he struck again and the Princess held her breath. It seemed as if the Prince Elector, in his sleep, must have heard this knock. She found herself glancing at the distant towers of the castle.

Then came voices, and her courage rose again. After a little she saw the yellow light of a lantern carried across the orchard and dark figures moving under the trees. Little clear yet distant sounds came through the night, the sound of bolts drawn, voices, chains rattling, and at last the clatter of moving horses. At that her blood leapt; she stood up, suddenly finding waiting unbearable, but she kept herself cautiously back in the shadow, lest anyone coming should see her.

The lantern again passed under the trees, and this time only a single figure with it. Presently Mr. Denton, leading two horses, came round by the road. They were both saddled for men; Mr. Denton explained that he had let the farmer suppose that the companion waiting for him was of his own sex.

"It is no matter," said the Princess, smiling.

Mr. Denton helped her to mount the rough country horse and she caught up the reins, seating herself as best she could on the ungainly saddle; she was a fine rider, as she should be, and with a sure seat. Mr. Denton mounted.

"You know the way?" she asked him.

"I think so, madam."

The Princess laughed.

"I know I do, very well."

She touched up the horse and they took the long, straight road to Hartheim. In a little while they came to a village and clattered through it. The Princess saw the little white houses, the orchards, the church spire swim past, and they were out on the open road again. Mr. Denton rode a pace behind silently. A sudden thought occurred to the Princess.

"Do you know where His Highness stays?" she asked under her breath. Until this moment she had not reflected on it that she did not know.

"There is only one inn, your Highness—the sign of the Peacock."

He fell behind again, and they rode on through the moonlight. It was not long before they gained the summit of a hill, and looked down on a little cluster of houses round two cross roads.

"Hartheim," said the Princess faintly.

They slowly descended the hill.

There was no one abroad in the village street, not a sound, save their own horses' shoes on the smooth road.

"This is it, madam," said Mr. Denton. He drew up before the house, where the sign swung over the door.

"What are we to do now?" murmured the Princess through white lips. Her strength had gone from her suddenly. She sat stiffly on the huge saddle, her hair shaken down by the rough riding, her eyes gleamed in the moonlight, steadfast yet afraid.

Mr. Denton dismounted and knocked. She held herself rigidly, the breath coming sharply through her cleft lips.

The door was soon opened. Being on the high road between Hesse-Homburg and Strelitz-Homburg, mine host was used to travellers.

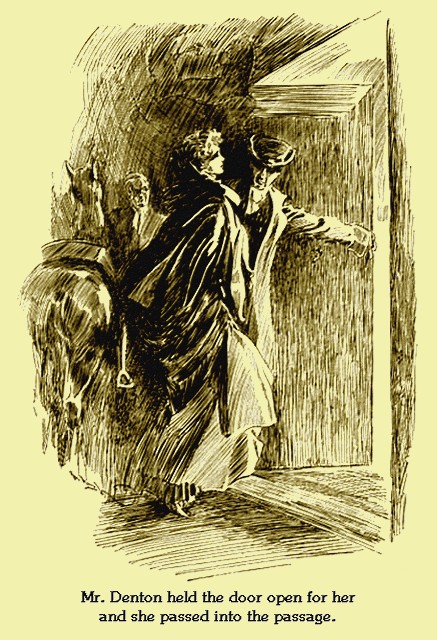

Mr. Denton spoke in a low voice to the man who opened to him. She could not tell what tale he was offering; she waited, and when the servant came to take her horse's head, she slipped from the saddle. Mr. Denton held the door open for her; she passed into the passage, and sank on the bench beside the tall clock. A candle guttering in the wind from the open door stood on a shelf; she saw the stairs ascending into darkness.

"Where is he?" she said. "Where is he?"

Her body was numb, but her heart on fire.

"I will ascertain, madam," answered Mr. Denton. He was rather pale.

Mine host descended the stairs; the Princess leant against the wall; the tall clock struck 'three with a silvery chime.

"His Highness Prince Frederic of Hesse-Homburg is here." said Mr. Denton; "he arrived about four days ago."

"Yes "—the landlord raised his candle high and stared behind it at the lady's face—"he came here."

The Princess spoke:

"Will you rouse him? On a most pressing matter, at once."

The man set the candle on the self.

"He left here this morning early," he answered. "He is gone."

"Gone!" Her head whirled. "He is gone!"

She sprang up from the bench and ran out into the road, the two men following her.

"He is gone!" she repeated. "Where?"

The landlord nodded towards the servant.

"He went to the cross roads," said the old man. "I do not know which one he took."

"Oh, too late, too late!" whispered the Princess. She fell back against the lintel of the door; she turned her face to the sky.

"We must go back," said Mr. Denton. "Quick, madam, or we shall have lost all for nothing."

"I will ride after him," she returned desperately.

"God help us! We do not even know which way he went."

It was hopeless. She looked down the pitiless dim white rood with despairing, tearless eyes; she let Mr. Denton, whose movements were quick and eager now, help her to mount, and made no complaint. Back along the road they had come, with the moon waning behind them now, and the dawn slowly filling the sky.

"We did our best, madam," said Mr. Denton.

She made no answer with her lips, but her hand motioned him to silence. She was going back with every footfall of her horse nearer the Prince Elector, nearer the castle and her old life, further from him and her hopes. Why had she not gone wildly in search of him? Again, like a coward she had turned back. What had he said: "This is our day, our chance," and she had not taken it that day; and now she could not. Their chance was over; perhaps she would never see him again.

She lifted her haggard eyes to the brightening sky, and the slow tears rolled down her cheeks.

They reached the farmhouse, and she dismounted in silence, while Mr. Denton, framing what excuse he might, led the horses back.

Every moment the light gathered strength; every moment the dangerous nature of her position increased; she might be seen, someone might discover that she left her room. Soon the servants would be abroad, people pass up and down the road. She thought of all these things in a vague way, but she was too sad for fear; before her was that picture of the cross roads branching apart under the moonlight, of the old man holding the guttering candle, under the sign of the Peacock; in her ears echoed his words:

"He went to the cross roads; I do not know which one he took."

Mr. Denton joined her, and she preceded him in silence across the park. He looked to right and left anxiously; this was the most unlooked-for and perilous part of the enterprise, but she walked rapidly with unseeing eyes. The birds were awake in the garden, and the colours of the flowers visible in the pearly light. When they gained the balcony and the gray ball-room, the sun was beginning to rise in pale gold.

The Princess turned to Mr. Denton:

"It was not meant to be," she said. "Yet, thank you!"

She never asked him to keep her secret nor hinted that she dreaded his knowledge of what she had tried to do; and that was his reward.

She turned across the shining floor. Her skirts, wet with dew and stained with dust, made a little sound of rustling in the stillness. Mr. Denton held the door for her; she passed out into the corridor and up the stairs.

Walking with a mechanical caution, she gained her room, locked the door, put away her tell-tale clothes, and all cold and numb, went on her knees beside the bed. The long rays of the early sun struck through the window, and played in her dishevelled gold hair.

"How I have dreamed to-night!" she whispered her throat, "how I have dreamed!"

The Prince Elector brought his bride home towards the evening of a mid-June day. The villagers had decorated the road to the castle with arches of flowers. A fete was held in the gardens, and a great banquet given to the country people under the trees.

The Princess, very sweet to look upon in her fine white riding dress, rode a chestnut horse at her husband's side; her manner was quiet and gentle. As the cavalcade reached the park gates the village children came across the grass and offered her a great bouquet of wild flowers. She thanked them in a voice that faltered a little, and the procession continued its slow progress under the great trees. The air was full of the golden-dusty evening sunshine. High up the leaves showed spaces of pale bright sky; it seemed to the Princess very far away when she looked up at it. On the steps of the palace the officials of the kingdom were drawn up to receive her. As the bride dismounted and set her fool on the ground, the bells sounded, and a hundred swords flashed into the air in salute from the guards gathered about the steps.

Standing on the shallow, sunny steps, the Princess listened to the chancellor's speech. She held the flowers she carried up to her face. Once she glanced furtively at her husband. Seeing nothing on his delicate features but a cold self-satisfaction, a faint colour came into her cheeks, and she looked away again.

In a few soft words she made answer to her welcome. She gave the chancellor her hand to kiss, and all of them standing there and looking at her pure loveliness had an instant and secret feeling that she was too good for the Prince Elector, but she herself hardly knew any eyes were on her at all—she went through the duties mechanically, her thoughts running on one theme.

"This is where he lived. He must have come up these steps often—often; he must have touched the doorway in passing as I touch it now; these people, now speaking to me, have spoken to him; this is his home that I have driven him from. Where is he now? Where is he now?"

Before the hour of the great banquet she contrived a few words with Mr. Denton, the first since that night that was so strange and terrible a thing to remember. She would have liked to let silence cover it for ever, but she reflected that this man, unpaid, unbesought, was keeping her secret, and that she owed him some recollection of his services.

She called him inside the antechamber where she awaited her husband alone.

"Have you in any way suffered for what you did once for me?" she asked.

"No, madam," and Mr. Demon bowed respectfully. "I explained it with regard to the horses. I think the landlord at Hartheim is safe, madam."

She winced at the name.

"Safe?"

"No one is likely to question him; I think he did not recognise your Highness."

"I was thinking of you," she answered. "I should not like you to stiffer any loss because of me—and will you take this, to pay, at least, for the horses? I have had no chance before—"

She held out a purse in a little trembling hand as she spoke.

"I would rather not, your Highness," said Mr. Denton deferentially.

"I can do nothing else for you," she answered rather piteously.

"It is no matter at all, madam."

The Princess moved away suddenly, hearing a step. Mr. Denton bowed and withdrew.

It was the Prince Elector who entered from the inner door, gravely smiling. The Princess leant her arm against the mantelpiece, and stared at her reflection in the mirror above it. She was in white and gold, gleaming, fair from head to foot. She stood quite still; there was nothing to be guessed from her face.

His Serene Highness began talking. He spoke of the gardens he was laying out, the new wing of the palace he was building; he told her of the cascade he had made, and that the water should flow down it to-night for the first time; told her also of the general prosperity and magnificence of his kingdom. She answered him when he paused for it, but she gave him no more than a few bare words, and never moved or turned her head.

He knew well enough what she was thinking of. He knew that, by banishing his brother from the country, he had only outwardly triumphed, and that the other man was there still, in her thoughts, in her heart. As he walked up and down, speaking quietly, casually, he meditated some means of delicate revenge, some way by which he could stab this resignation of hers that galled him by its new passiveness.

Sounds of the preparation of the banquet came to them—voices and snatches of music. The Prince continued to walk up and down speaking, the Princess to stand mute and to tolerate him.

Suddenly a gorgeous moth fluttered in through the open window; it was a sparkling blue colour, and it came straight to the Princess and settled on her arm. She looked up now with a little exclamation; the moth rose from her arm and flew away. She made a movement after it, towards the window.

"Come into the garden," said the Prince Elector, "and I will show you the cascade."

The moth fled into the darkness as he spoke.

"I will follow your Highness," she answered. She picked up her scarf, put it about her shoulders, and passed beside him into the summer night.

The gardens were lit with coloured lamps that east gleams of curious warm light on the trees and flowers. The stars were out, but there was no moon. As they walked down the long, bordered paths the Princess saw the blue moth now and then, flitting before her. Neither she nor her husband spoke. They passed the grove of laurels and the fountains that were not playing yet, and came to the foot of the cascade. It was finished; the smooth slabs of rock grown with ferns rose up from a basin surrounded with plants, and at the side a gradual path led to the temple at the summit.

The Prince Elector explained that when the water was turned on it would fall straight over the great height of rocks and form a pool of what was now a bare stone basin. He told her with what difficulty and expense the water had been brought, and added that the results corn. pared fairly with the cascades he had seen abroad.

"Will you mount to the top?" he asked.

"As you will," she answered.

His Serene Highness gave her a quick glance and set his lips.

The trees shading the winding upward path were all hung with red lamps, casting a rosy glow over the two figures as they' ascended, but when they reached the summit there was no light save the stars.

The Princess drew back instinctively from the edge of that sheer drop, and shuddered at the height at which she found herself.

His Serene Highness showed her the temple, finely carved within and without. It was not possible to see in this light the fineness of the workmanship. She assented to its beauty, not turning her head to the carving, nor to him. Suddenly he swung round to her with a complete change of tone and manner.

"Madam, do you think I will endure this?"

She drew herself up now.

"You have no pity, no shame, to speak to me like this." Her head dropped into her hands, and she sat very still.

Her husband stepped to her side.

"Why," he mocked, bending over her, "it is a pity he should not know of this desertion of yours—is it not, madam?"

She looked up.

"Not know?"

The Prince Elector laughed.

"'Does she favour you?'" he quoted. "I had your letter in my pocket, but I asked him that. 'Oh! rest assured she does not care,' he answered me. If she had cared, she had been on my horse before me, and we miles away.' But you were not so courageous, madam. He does not know?"

The Princess sat rigid. This was a new and terrible thought—he thought she did not care! All his life he would think that, and she would never be able to tell him. Her silence that day had been mistaken—her cowardice! Yes, she had been a coward, and this man was telling her so—this man who knew her heart. He was mocking her with her lost chance.

"You do a dangerous thing," she said in a stifled voice. "What object have you in maddening me?"

"Ah!" he said quietly. "It does sting you—you thought that he knew—that kept you calm."

She sprang to her feet.

"I could tell him yet!" she cried passionately.

He flung up his head.

"Then, by Cod, I could have my vengeance on both of you! You are my wife now."

She stared at his figure, black against the misty starlight. He moved, and she passed from the temple out into the air again, as if she stifled.

"You can never speak, I think," said his Serene Highness; "and why should you wish to? He never knew, and you can forget." He could hear her quick breathing.

"You insult me," she said thickly. "I trusted you once, and you use what I told you as an insult. I appealed to you, and you mock me with it? Why do you hate us both? You never cared for me. You might have set me free, but you were jealous that it should be he. You hated him. Why?" Her voice strengthened. "Because you have a lackey's soul, and are not fit to hold his stirrup! You!—you who had my letter and let him think I did not care!"

He made a movement forward, and caught her arm. "Curse your tongue!" he said under his breath. "Remember who I am."

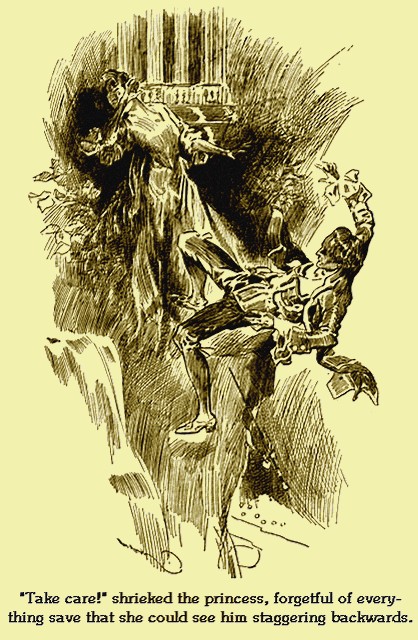

She shuddered at his touch, shrank away. Then, maddened and reckless, flung him off and made a blind step back. They were both on the edge of the cascade—a thing of stone, without movement, blind, dumb, deadly. His Serene Highness staggered unaccountably. Her whole strength could not have sufficed to throw him over, but he had caught his high heel on a loose stone and lost his balance.

"Take care!" shrieked the Princess, forgetful of everything save that she could see him staggering backwards. She flung out her hand, and then, screaming, fell back with it over her eves. She had seen him grasp at the bushes, seen his ruffles, mere patches of white, as he tossed up his arms.

It was all over in a second, incredibly soon. In one horrible flash she could see the whole ghastly thing. There was no hope for him. She turned sick at the thought of the smooth face of the rock—the hard stone at the bottom. In her horror she used his name, called him by it. "Charles!" she shrieked. "Charles!"

She dragged herself on her knees to the edge of the cascade, and, clinging to the plants, peered fearfully down. Nothing save red lights and shadow—nothing! He had made no sound—he could not have fallen. She sprang up, expecting to see his figure at her side, expecting to hear his mocking voice—to see the cruel gleam of his eyes. Nothing.

"Charles!" she cried again, and ran wildly down the path.

At the bottom she turned, hardly daring to look, hardly knowing what she did, or what had happened. By the red glow of the gala lamps she saw him lying out in the stone basin, his arms flung wide.

In his bridal clothes that glittered white and silver—lying there with a mocking expression on his upturned face—or was it only the flicker from the swaying lamps? He was dead.

She could neither cry out now nor speak. In a slow, fascinated horror she gazed on him. He was dead! It seemed impossible, beyond the mind to bear, that anyone should die so suddenly.

Her first cry had brought people from the grounds near. One or two, loitering in the shrubbery, came hurrying up. They saw two white figures lit by the trembling little lamps; he, motionless, with the light flickering to and fro on his upturned face; she staring down from the edge of the basin.

"The Prince!" cried one.