Map of Holland

Map of Europe, ca. 1650

"For, Sir, you that see all the great motions of the world and can so well judge of them, know there is no reliance on anything that is not steady to principles and prefers not the common good before private interest." —The Bishop of London to the Prince of Orange.

Prince of Orange, (1650-1702). Engraving by G. Valck.

"Mr. Mompesson," said the King serenely, "do you believe in God?"

The young man answered evenly: "Most assuredly, Sir."

The King looked at him steadily out of dark clear eyes and smiled a little like one considering. "Any particular form or manner of God?" he asked, holding his olive-hued hands to the fire blaze.

Bab Mompesson glanced up at his questioner. "I do not take your Majesty's meaning," he answered in a tone of hesitation.

The King kept his soft yet powerful gaze fixed on the man before him as he replied in the smoothest accents of his pleasing voice: "If you believe in God and go no further, Mr. Mompesson, you are scarce the man I want. My Lord Buckingham, my Lord Arlington would say as much—at times. If you would serve me you must have a creed as well as a God."

"I am of the Church of England, Sir," said Mr. Mompesson, "and zealous for the Reformed faith."

"You mean that—honestly?" asked Charles Stewart slowly.

Mr. Mompesson smiled now and returned the King's strong look strongly. "My father was of the Lord Cromwell's party as your Majesty knows—a dissenter—we have never favoured Popery."

The King placed his dark hand on the crimson sleeve of the young man. "I have no wish to convert you to the Church of Rome," he smiled. "You are here because I heard from my brother that you were the most obstinate Puritan at the Admiralty, a man of old-fashioned virtues, Mr. Mompesson."

"Sir, I hope his Highness cannot call me lacking in my duties," answered Bab Mompesson stiffly; but he slightly flushed under the continued scrutiny of the powerful dark eyes.

The King rose from the tapestry chair with a graceful abruptness and looked down on the hearth where logs burnt to a clear gold flame; he leant against the mantle that bore the arms of England and France, and stared, not now at Bab Mompesson, but at the two tall, uncurtained windows.

The sky was a foreboding grey, a few flakes of snow fluttered against its leaden depth; the trees and walks sloping down to Whitehall steps and the river swollen between its banks were bitten with frost and smitten with a keen wind.

Mr. Mompesson, following the King's gaze, glanced at this prospect without interest, then took advantage of the silence to observe the King, whom he had never spoken with before this afternoon.

The face of Charles Stewart was dark and lowering now, his mouth set with a drag of scorn, his brilliant eyes frowning under the heavy brows; the thick curls of his black peruke half concealed his worn cheeks and lined brow; he rested his strongly shaped chin in the palm of his swarthy, elegant hand and his elbow against the mantleboard as he gazed sombrely out at that dull chill view of Whitehall Gardens. He carried himself very stately when he moved to again look at Bab Mompesson, who waited silently to know the King's will.

"Mr. Mompesson," he said, "I have resolved to trust you."

The harsh lines of his face vanished as he smiled gaily; the firelight cast a glow of colour up his tall figure and struck glitter from the paste buttons of his black satins.

Mr. Mompesson bowed.

"Are you surprised?" asked the King. His rich voice had fallen again to a flattering softness; he laughed with his eyes.

"Your Majesty knows that I must be."

"Pleased—you do not add," said Charles lightly. "Well, that is no matter at all—you will serve me, I take it?"

"With all my powers, Sir."

The King laughed, not unkindly. "Look you, Mr. Mompesson, I'll put a few questions. How old are you?"

"Thirty-three, Sir."

"You have travelled somewhat?"

"In Italy, France, and Germany, Sir."

"In the train of our ambassadors?"

"Yes, Sir."

"You have learned, Mr. Mompesson, to keep a secret, to control your feelings, to watch wisely, to report concisely?"

"I have, I think, learnt those things, your Majesty."

The King fondled the ribbon that fastened his glass. "What is your wage at the Admiralty?"

"Three hundred a year, Sir."

"Paid regularly?" smiled Charles in a friendly manner.

"Not always, Sir."

"Well, I am not paid regularly myself, Mr. Mompesson."

The King glowered into the fire, showing his commanding profile toward Bab Mompesson. "You are a gentleman'?" he asked sharply.

"We have written esquire after our name for three hundred years, Sir; our lands are in Berkshire; I am a third son."

"I think you have all the qualifications, Mr. Mompesson, for the service I desire of you."

The King turned to face him full. "You and I must talk politics awhile," he added; "you know something of them?"

"Something—yes."

The King's gaze searched him intently. "Do you remember my Lord Arlington's journey to Holland two years ago?"

"Perfectly, Sir."

"And the object of it?"

"That was kept something secret. I believe he went to arrange a marriage between the Princess Mary and the Stadtholder, your Majesty's nephew."

The King seated himself again in the great chair by the hearth and leant back indolently. "He went to offer my niece's hand to my nephew and it was refused," he said, paused a moment, then added in an authoritative tone: "This is the mission I will send you on—and this time the hand of Mary Stewart must not be refused."

Bab Mompesson flushed. "I, your Majesty?"

"You," said the King. "You are the man for this. My nephew will not speak to Arlington, who bungled sadly—Temple is no better than a tool of the Dutch—and I have no man here in Whitehall whom the Prince would trust."

He smiled wickedly. "The Prince believes in God, Mr. Mompesson, a Calvinistic God; he is a fanatic in his way and honest—such another as himself alone can deal with him, do you understand? I sent Buckingham, I sent Arlington—each time a mistake. No courtier of mine can influence my nephew—he has suspicions of us all—and I will send no great men, for I do not want this news noised through Europe—you follow me?"

The King spoke rapidly, earnestly, yet with a smile. Mr. Mompesson was in every way overcome and bewildered by his Majesty's amazing frankness.

"I follow you, Sir," he made answer; "you would put a great responsibility on me. Sir William Temple is your Minister at the Hague..."

"Temple is a good soul," interrupted the King, "and the Prince liked him, but he does not, I take it, have much influence with his Highness since he has once tried to arrange this match and failed."

Mr. Mompesson endeavoured to grasp the situation. "I am to go to the Hague on a mission unknown to Sir William, a secret messenger from your Majesty to his Highness?"

The King nodded. "Do you undertake the commission?"

Bab Mompesson laughed. "Of course, your Majesty."

The King's smile was unchanging. "You are ambitious, then? My faith, I am glad of it—succeed and I'll make something of you yet. Don't cost me too much in Holland, though, Sir; we are not rich at present."

Mr. Mompesson was flushed and breathing rather thickly; this was the finest chance he had ever had in his well-filled life. The King's trust, the King's graciousness roused a warm response of loyalty in the King's subject; he stood silent, but Charles seemed pleased with his look of flattered gratitude.

"Now I'll tell you something of my policy," said his Majesty very pleasantly. "To begin with—I have done with France."

Charles II (1631-1685). Painting by John Smith, after G. Kneller.

Mr. Mompesson raised his eyes quickly; the King continued with his unalterable air of ease and authority, talking of great things in a casual, commanding fashion.

"The Parliament will not endure that French alliance. My brother's faith and his Popish marriage have cost me a great deal of popularity. You English are stiff as mulets in these matters, Mr. Mompesson—the moment has come when you must be conciliated."

He paused a moment to take note of the gratification expressed in Mr. Mompesson's frank face.

"I must have this Protestant match—England wishes it. I must have peace in Europe; for two years a useless congress has sat at Nymegen—I must have peace!"

Bab Mompesson made a simple answer: "Is this brilliant marriage a bribe to the Prince to conclude that peace he has hitherto refused, Sir? It is as well I should understand your Majesty's mind."

The King's heavy lids flickered. "No bribe," he said with distinct emphasis. "I would not bribe my nephew, but I would give him the hand of the girl who is heiress of England as guarantee of my faith in this new alliance I will make with him—you may tell him so much."

With that he looked into the steady heart of the fire with calm eyes and Mr. Mompesson replied warmly:

"Sir, what your Majesty proposes will delight England—Parliament, and people, Sir, will rejoice at your Majesty's goodness."

"But my brother and my court will have no words hard enough," said the King frankly. "Therefore go carefully, Sir. I would not have the opposition roused. Be secret, avoid the Jesuits and the French their first news of this must be that it is accomplished."

He glanced round and his lip curled freakishly. "I'll go warrant James would miss his ears to prevent this journey of yours. He suspects me, I'll warn you that—but this is my Lord Danby's policy I follow."

From the pocket of his black coat he drew out a long packet. "Here are your instructions, Sir—I and Danby drew them up. I have advised the Prince of your coming; you will live quietly at the Hague and avoid Sir William, who will be put about at not being admitted to this secret, I doubt not—so do your best, Sir."

He rose and held out the letter. "Danby will send you money and write to you; the key of the cipher is in this."

Mr. Mompesson took his instructions, kissed the hand that offered them and was leaving in elated spirits when the smiling quiet of the King, the expression of his humorous eyes struck him suddenly with a sense of danger; he knew something of the intrigues of the Stewart and Bourbon courts.

"Sir," he said on the impulse of his reflection, "your Majesty means what you have said to me? You said you would not send a great man—forgive me, Sir, was it because you would sacrifice a little one?"

"In what way, Mr. Mompesson?" asked Charles calmly.

"Your Majesty is sincere?"

"From my soul, Sir."

"Your Majesty has done with the French alliance?"

The King smiled charmingly. "Come, Mr. Mompesson, you suspect me of being a double fellow! Here is my word on it. I mean what I have said—rupture with France, peace with Holland...The Protestant match. Am I not the Defender of the Faith?" He lifted his head slowly and, still smiling but with a subtle change to slightly disdainful dignity, repeated, "My word on it, Sir."

Bab Mompesson bowed very low. "Am I to sail at once, Sir?"

Charles glanced at the bitter prospect of snow. "As soon as you may for the weather."

"And what am I to pass for, Sir?"

"A gentleman traveling for curiosity. Your wits must teach you what complexion to put upon your mission. Remember I trust you." The King's sparkling eyes contradicted the King's grave words. Bab Mompesson was not wholly satisfied, though overborne and silenced.

Charles dismissed him with the quiet, "I trust you," and turned away half restlessly, but before Mr. Mompesson had opened the door the King had swung round again on his gold heels.

"Sir," he said in a different and haughtier tone, "if my nephew prove obstinate you shall not fail to remind him of his duty to me and of the many grievous defeats he has suffered in this campaign—if he reject my alliance he is no better than lost." Then he laughed and after a few quick steps had his envoy by the arm.

"God bless you, Mr. Mompesson. I trust the damp will not give you an ague—and so farewell."

Mr. Mompesson withdrew very lowly, leaving Charles of England smiling after him. As he descended the great stairs he met three people. The first, Monsieur Barillon, representative of France powdered and gorgeous, carrying his hat with great purple feathers before his lips. Bab Mompesson, bowing himself aside on the wide landing, watched the Frenchman's light figure turn into the room at the end of the long gallery where the Duchess of Portsmouth kept court for the French faction. His uneasy reflection found voice in the quick words with which he greeted the man he found himself face to face with on the next turn of the stairs, Lord Danby, the King's first Minister, Sir Thomas Osborne once a friend of Bab Mompesson; his patron now.

"My lord—one whispered word—is the King sincere?"

Lord Danby paused; his fair face, shaded by the soft cavalier ringlets, showed anxious; he took Mr. Mompesson affectionately by the arm. "Do you think I would be party to sending you on a fool's errand, Bab?" he asked. "You were surprised at what the King had to say to you?"

"Amazed, my lord—I never looked for such distinction..."

Danby interrupted. "Do not think the King knows nothing of you. I have been begging a post for you these six months—

"And the King is sincere?" repeated Bab. "In the matter of the French? I cannot credit it."

"I dare assure you of it—Parliament would force us even if we were not willing. Hush, no more—I will come round to your lodging tonight."

With a little nod my lord passed up the great stairway, his blue and white satins disappearing round the passage that led to the King's cabinet.

Mr. Mompesson, striving to repress a flutter of excitement and to leave the palace as carelessly as he had entered it, though the secret he was entrusted with seemed to him to be written on his forehead, was a third time arrested. A girl in a mutch and cloak of grey satin was waiting by the newel-post, and when the King's messenger set foot in the hall she imperiously caught hold of his sleeve.

"Mr. Baptist Mompesson," she said sternly, "I wish to speak to you."

He stopped abashed; she was a stranger to him. "Madam," he began with a stammer, but she gave him no time for more.

"Oh!" she cried angrily, "there is a silly moppet!"

A childish laugh from behind the stair rails showed Bab that his enemies were two; a taller lady was in ambush in the shadows of the waning afternoon.

He hesitated, half annoyed, half flattered, and while he was framing some manner of speech, the girl in the grey hood gave his arm an impatient shake.

"Come with me," she commanded. "I am Mary Stewart."

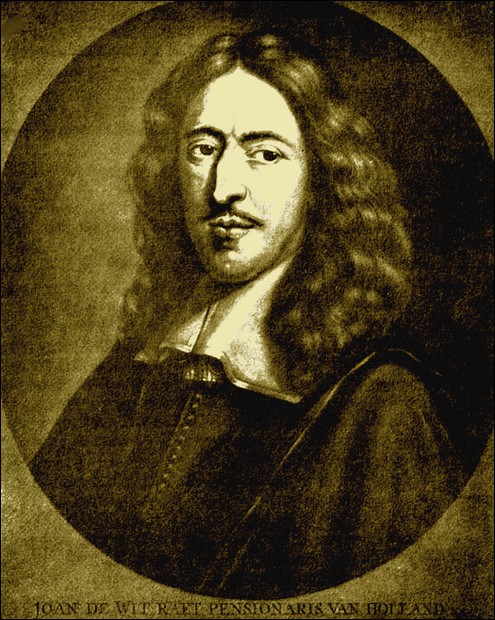

Thomas Osborne, Lord of Danby.

Bab Mompesson flushed as he bowed. "Your Highness must excuse my ignorance..."

She laughed shortly, interrupting him, "Follow me, Sir." With a proud little wave of her hand she beckoned him after her and turned rapidly down the corridor.

The other lady, plain-featured, dark, young, graceful and sprightly, flashed a sharp glance at Bab. "You had best obey the Princess."

Mr. Mompesson came stiffly. He wished he was outside Whitehall, outside, London; he had no liking for this instant interruption to his business; he was vexed that the Princess knew something of a matter he had thought secret.

The two ladies stopped before the unlatched door of the banqueting hall and the Princess struck it open with an impatient hand, entering; followed closely by her companion—and reluctantly by Baptist Mompesson. The vast chill chamber was filled with a dreary grey light of winter; the snow-flakes thickened starkly against the woodwork of the tall windows and blotted out the prospect of trees and sky.

Mr. Mompesson had been in the place once or twice before when the King dined in public, but always beyond the rope that divided the spectators from the court; now he stood near the head of the table close to the King's great chair and under the gilt gallery hung with arras of Italy and Flanders.

The tall lady closed the door cautiously, a smothered laugh from her breaking the quiet; the Princess cast her riding-mask on to the kings's chair and clasped her hands angrily, facing Bab, who looked from one to another, half amused, half perturbed.

"On what errand does my uncle send you to Holland, Sir?" demanded Mary.

Bab considered her. She was slender, stately, on the verge of beauty, the Stewart chestnut in her thick curls, and the soft short-sighted weak eyes she narrowed in an effort to see more distinctly; her mouth held an expression of gentle sweetness, even now, in her anger. Her extreme youth disarmed Bab's resentment; she had, too, an air of simplicity that put him completely at his ease; he stood meekly before her.

"His Majesty has given me no leave to speak of my errand, Madam," he answered humbly.

She swept aside his excuse. "I know, Sir—it is to find me a husband." Her lips quivered and in search of help she glanced at her friend, who leant indolently against the King's chair.

That lady smiled up at Mr. Mompesson. "Come," she said lightly, "you see we know your intrigues—confess and be absolved. What said the King?"

"Who are you, Madam?" asked Bab bluntly.

"Lady Monmouth," she answered and looked at him hardly.

"Then I cannot see your interest in the matter, Madam," he said, disliking her half-insolent air.

"You must speak for yourself, Moll," remarked my lady indifferently. "I am not like to get a good hearing, it seems, from this gallant."

The Princess darted an indignant glance over Bab's tall person and good-tempered face. "You are a proper envoy," she said scornfully, "to carry the hand of a Princess to be huckstered abroad. Oh, what a pass are we come to?"

Bab was silent.

Lady Monmouth kept her eyes fixed on him intently. "The King's brother," she said quietly, "knows as much as the King. Danby thinks he is vastly secret but his scheme entertains the court. The Duke knows Monsieur Barillon knows, I dare swear."

Bab, though disconcerted, held his ground. "Neither will prevent me from fulfilling the King's commands," he said. He fixed his eyes on the lengths of tapestry before him, resolved to foil them both by silence.

The Princess stamped her foot. "My father is as much against this as I am," she declared, and the carnation of passion stained her cheeks. "Between us we have some authority. Do you hear me, Sir? I will never marry in Holland."

Bab bowed.

In an increasing agitation the Princess continued: "I have been offered once to my cousin and refused—that was against my father's wish. I will not be cried in that market again..."

Mr. Mompesson was bound to make some protest. "Your Highness does not understand—this is a question of politics..."

"Nay, I do not understand your politics," she made quick retort. "But I see that I am to marry to please my uncle. Holland is the dullest place in the world. I cannot leave England, can I, Anne?"

The short-sighted eyes turned an appealing glance toward the Duchess. "Why, if you must," that lady made reply, "you can give some trouble first..."

The Princess's anger gave place to a wilful laugh, she tossed her head. "You know my mind, Mr. Mompesson, and you know my father's mind. You are like to have a fool's errand if you offer me to my cousin. Mr. Barillon can help me to a fine match in France."

"Do you favour the Papists, Madam'?" asked Bab sternly.

"Maybe," she returned haughtily. "At least I have no love for the Puritans, and do not mean to sit strait-laced at the Hague for the rest of time."

Bab smiled. "Shall I tell his Highness that'?" he asked. He looked upon her only as a child, the almost unconscious instrument of the French policy of the Romish Duke, her father.

"You may tell him worse if you will," she answered. "Say what he refused once is not offered again with any wish of mine. Say I was a child then but am more now and have some power, and if he likes not my message, say I have sharper for the asking."

Bab smiled and shook his head. "I fear Your Highness must find another messenger; my business is with affairs of State."

Mary came a step nearer, melting into a sudden tempting softness of anxious supplication. "Surely now, Sir, you will not go after all I have said." The lovely brown eyes opened wide on him as she approached. "Stay at Whitehall and in a day or so the King will change his mind, I'll be warrant he will."

Bab's smile deepened at her childish suggestion. "It wounds me that I must refuse Your Highness..."

She interrupted him. "Is the King's favour so much to you, Sir?"

There was a certain depth in her tone and expression as she spoke that belied her flippant pose and speech and moved Bab to answer seriously.

"Not the favour of the King only, Madam, but security in England, peace in Europe, and safety to the Reformed faith depend on success of my mission."

He spoke so gravely that the Princess was quelled, but Lady Mon-mouth turned his speech with her childish laugh. "Moll, my dear," she said, slipping her arm round Mary's waist, "they never lack specious excuses when they are going to sacrifice us, these men!"

Bab knew enough of her history to forbear a retort, and the Duchess, as if wishful to cover the bitterness in her tone, added with a indolent accent, "Madam, we have gossiped here long enough to unleash a pack of surmises. If some babble discovered us we are like to be rated for interfering with the King's messenger."

Reluctant, half pouting, with wilful tears and trembling lips Mary moved toward the door. It was cold in the empty hall and she shuddered under her cloak. "Mr. Mompesson," she said, pausing to face and dismiss him, with a sudden air of the great lady, "I wish you adverse winds, a rough sea, an ill welcome in port and no success at all in your mission, and now you know my mind." She paused breathless.

"I hope Your Highness may come to change it," answered Bab bowing. "In wishes sit heavy on the sails of any man, and if I drown betwixt here and Holland it will be an evil thought for my last that Your Highness rejoices in my disaster."

Mary looked at him doubtfully. "I meant no ill to you," she conceded with a sigh. "Now, you will put me down a vixen. God, He knows my heart is heavy in my bosom as lead in the hand—but if I cannot wish you fair sailing, I'll wish you a better errand." With that manner of high-spirited gaiety that was hers even in her trouble she gave him a little curtsy and quitted the hall on Lady Monmouth's arm.

They left the door ajar behind them, and Bab could hear the sound of high-heeled shoes and the little stir of petticoats for a moment before silence fell unbroken. Thoughtfully he stood by the King's chair on which still lay the Princess Mary's mask and reflected on what he had that afternoon seen and heard in Whitehall. Large issue and small detail—the gentle speech of the black-eyed King; the instant's impression of Monsieur Barillon, discrete, splendid, with downcast lids and a light step directed to the room at the end of the gallery; Danby's anxiety and gesture of caution; the unexpected appearance of Mary Stewart with her impetuous words and troubled loveliness; Lady Monmouth's restless spirit showing in her half-bitter sentences—were woven together across the background of the palace, as figures, trees, and flowers were woven into interchanging lines of red and blue, gold and silver in these tapestries of Ypres and Mortlock that hung from the gallery of the empty banqueting hall. And as behind all the fantasy of the arras was one colour of blue and stars never to be quite obscured, so behind Bab's racing thoughts was the purpose of his mission, the leagues with Holland, the Protestant marriage, the break with the French alliance the country loathed, the policy of the King forced at length by Parliament to the national will. Bab was proud of his task; he felt grateful to the ancient friendship of Danby that had put him in the way of such honours and to the graciousness of Charles, but he was not yet hardened diplomat enough to consider without discomfort the reluctant tears of the Princess, whose appealing youth had endeavoured foolishly to arrest his journey.

The grey clouds thickened, darkened, seemed to close down and overwhelm the land. Bab could not see the river nor the trees nor anything but a steady swirl of snow that beat noiselessly against the tall windows. The fierce weather excited him, he longed to be aboard the boat making for Holland, regardless of the most sullen seas or powerful storms. In the lowering moment of the sudden fall of snow the banqueting hall became so dark that the glowing and flamboyant painting on the ceiling disappeared in the great shadows that obscured the splendours of the place, as breath dims brightness on a glass.

Bab, roused by the gathering darkness from elated reflections, turned to leave. As he moved toward the door he thought that he heard a cautious footstep in the gallery above. He stopped instantly and looked up; but the ill light showed him nothing, nor was there another sound, though for some instants he waited. Only he fancied that he detected a disarrangement in the tapestry over the gallery rail as if some one had leant there and drawn hastily back.

"Beware of the Jesuits and the French," the King had said. Bab remembered the words, hot to think his speech with the Princess had perhaps been spied upon, and he himself already marked out as a victim of French intrigues.

Lightly and quickly he left the hall and passed downstairs without meeting any one, but in the courtyard he saw Monsieur Barillon again, stepping into his satin-lined coach with a shiver for the snow. As the running footmen took their places beside the horses, Bab with the driving storm in his face passed under the window of the coach as the Ambassador was pulling the leather curtain into place.

Bab looked up and the Frenchman looked down, pausing for a second with his hand on the blind-cord. The King's messenger stared into the keen handsome face and stopped for all the heavy beat of snow on his cheek. He thought that Monsieur Barillon would speak. But the Ambassador gave a pointed smile, twitched down the curtain and the coach swung and jolted out of Whitehall gates.

Bab instinctively put his hand to the paper lying next his heart. "He knows," was his instant thought. "Barillon knows."

Baptist Mompesson had rooms in Thryft Street, behind the Duke of Monmouth's great mansion in Soho fields; when he reached them he was snow from head to foot, and the darkness of the storm had merged into the darkness of dying day.

He took off his heavy wet mantle and went shuddering to the fire that welcomed him from the wide hearth. It was so bitter cold that last week's Gazette had spoken of a possible fair on the ice. Baptist remembered no such weather since the year of the Plague. He drew the heavy curtains over the view of dancing flakes and began packing his mails. The packet for Holland left the Thames every morning at six; he wished to depart with the next that set sail. He declared to himself that nothing less than a frost that sealed the river should delay him.

By seven of the clock his simple preparations were made. He had written to the Admiralty, packed his luggage, paid his lodging, explained his departure as a visit to his brother in Berkshire, and was ready for Danby and his last instructions.

But my lord was late. Bab became impatient; he flung up the window and stared out at the bewildering circle of snow-filled light his candles threw on to the night, closed it again and re-strapped his portmantles. Close on ten my lord was ushered up by the child who waited on Bab.

"If this storm does not abate you do not sail tomorrow," was his greeting.

Bab, in the relief of his arrival, was warm in welcome. "My dear lord, it will take more than a snowstorm to delay me."

Danby had his cloak off and was by the fire. His orange-silk coat with bullion enrichments and a thick crusted embroidery of glass sequins, his fair ringlets and clear blue eyes, his complexion of rose and white fresh above the black velvet round his throat, dwarfed the modest room to a mere background for his comely courtliness. As he held out his stiff fingers, released from chill gorgeous gauntlets of doeskin, to the grateful fire, his face wore the same anxiety as when Bab met him on the stairs.

"I would go at once—for I think I might be prevented going at all if I delayed," said Bab, looking at him keenly.

"The King holds firm—the King must have the Protestant marriage," answered Danby strongly.

Bab snuffed the candles that stood between them. "Monsieur Barillon knows," he remarked.

Danby glanced over his shoulder. "Knows what?"

"My errand—the King's mind."

"Not quite," replied the King's Minister. "Something, of course, he guesses—not all."

"How much?" demanded Bab.

Danby shrugged. "Enough to endeavour to thwart you."

"The Princess Mary knows," said Mr. Mompesson. "She met me below the stairs and entreated me to stay my journey. My Lady Monmouth was with her."

"She will give some trouble yet," frowned Danby. "As wilful a piece as need be..."

"But Protestant," added Bab.

"Yes," assented Danby. "Still her father's instrument."

He turned about, flashing his fine dress. "Look you, Bab," he said earnestly, "This marriage is the one thing to save us all. Temple and Arlington saw that two years ago and brought the King to propose it. The Prince refused the alliance, for it was put in the nature of a bribe and he smelt France behind. But I tell you, if he refuses this time, I and my policy are as good as lost."

"Are you no firmer than that in the saddle?" asked Bab, leaning forward across the table.

"Who is firm in his seat?" retorted my lord, "it is up and down with all of us. England is no passive hack to be spurred and kicked at any man's desire. I dare not, if I would, support the French alliance."

He bit his lower lip and added: "I dare not—I have been threatened with impeachment once. If I go against the Parliament, the people, I may look to a quick end to all my troubles."

"England clamours for a peace," admitted Bab, "and the maintenance of the Protestant interest in Europe—such is the policy of your lordship, I take it..."

The earl looked at him intently. "Such is my policy, the only one I dare to hold; this session roused a wind I thought would blow our heads from our shoulders. The King is most deeply pledged to France, but he was checked by this temper in the people..."

He paused and brought his hand down lightly on the low mantleshelf.

"The Duke is heir and a Papist—that is the unforgivable thing; and if his daughter, Queen of England to be, marries a Prince of her father's faith—we are all on the rocks—not I nor any man I know can pull the Government through the tumult there will be."

"The King sees this?" asked Bab.

"The King is a wise man," retorted Danby. "He observes how far he may go—he will have this marriage and a peace sooner than shake his throne."

"The Duke will never consent."

"The Duke must—his own inheritance is in great jeopardy. Think not of the Duke; King and people consent."

"But—the Prince?" asked Bab thoughtfully.

Danby bit his forefinger. "The Prince must be won—at any cost. In this match he will flout France and win England to the Dutch side; he has aimed at that since '72."

Bab was silent awhile, figuring in his mind these great policies, and my Lord of Danby spoke again impressively as one who strives to enlighten and convince.

"To please the Parliament without whom we are penniless, to please the people without whom we are not safe, the King must throw himself on the Dutch side; the French and Popery are loathed in England, and the Prince of Orange is the hope of all Protestants here. I tell you, I hold myself pledged to that young man; he is third from the throne; if he marries the Lady Mary he is second and a force in the country."

Bab gazed earnestly into the florid worn face of the King's Minister. "My lord, once again, is the King sincere? I can hardly credit it. Has he finished with France, or is this to be, as was the Triple Alliance, followed by a Treaty of Dover?"

Lord Danby did not lower his eyes. "The King could not, if he would, play false."

Bab smiled. "Your lordship knows that there is naught easier. The Prince could be dazzled with the alliance and the marriage, seduced from his allies, led into a peace, fed with promises and forsaken—is that the policy of his Majesty?"

The Minister made no answer.

"If it were," continued Bab, "it would spite me to the heart to be the engine of it..."

Danby interrupted. "The Prince of Orange is not a foolish man; he has proved that."

"He is a hard-pressed one," returned Bab. "The defeats he has suffered in the last campaign would unnerve an ordinary Prince, with De Ruyter slain and the French in Sicily. My lord, flatly, I hold his Highness an extremely brave Prince and should be reluctant to go offer him a rope of sand in his desperation."

My Lord of Danby turned about with some vehemence. "I am not deceiving you; the King will be free of France. Do you think we can afford to see the Spanish Netherlands' at the mercy of Louis?"

"I'll take your word, my lord," said Bab quietly. "I am English and Protestant and I cannot think that your lordship would have made choice of me to fool the cause I admire."

"I made choice of you," returned Danby, "because I held you an honest, prudent man, one who could speak sincerely to the Prince and carry belief. A specious diplomat would but waste his time. I warn you that you will find the Dutchman extremely obstinate, and that you must go carefully in matters of conscience."

He sighed wearily on the ending of his speech, and pushed his fingers up into his hair. "There are times, Bab," he added irrelevantly, "that I wish I was in the Tower and done with it."

"Yet your lordship would do a great deal to avoid being clapped up," smiled Bab.

"I stand or fall by the Protestant Marriage," said my lord gravely. "And others than I will go to ruin if it fail, for if the Parliament refuses supplies we are thrust into French arms and England is in a turmoil..."

He came up to the table where Bab sat. "Do your best for the sake of us all. In that paper the King gave you I have put some heads of various matter that you may use to persuade the Prince; the rest I leave to you. Live privately and avoid Sir William Temple, whose vanity is like to have a sore cut at being left out of this business."

Bab rose. "One word. If Monsieur Barillon knows the King's resolve to this match, which I think he does, am I not like to have some difficulty with his spies and agents?—for he is a very knowing man in intrigue."

"The Prince endures no Frenchman at the Hague. Your fine wits should suffice you to defeat secret designs." My lord went to the window and lifted the curtain. "What of your journey? The packet-boat leaves Gravesend at six, and the barges will take a great while down the Thames this weather."

Bab opened the window and looked out. "The storm is not near so fierce—it shall not do me the disservice to delay me. I start tonight."

When he closed the window he turned to find Danby with a half-reluctant air counting out gold pieces on to the table.

"Here are twenty pounds English," he said, "and a draft on a banker at Amsterdam for fifty. I'll send you more."

He sighed and picked up his cloak. "Make the Prince the finest offers in the world," he said, "so he consent to this match."

"Will your lordship be guarantee for the performance of these same offers?" asked Bab.

Danby held out his hand. "If I be not in the Tower," he smiled.

Baptist Mompesson grasped the still cold hand of the King's Minister and looked squarely into the steady blue eyes.

"I'll serve you well," he said simply.

The house was dark, the people being abed, and Bab took up a candle to show my lord down the steep, narrow stairs. When the street door was opened he looked anxiously up at the sky, where the snow-clouds were beginning to thin about the moon. At the corner of the square waited my lord's coach, the horses with white flakes on their harness and the feeble radiance of a street lamp showing the colours on the hammer-cloth. Danby waved his black-plumed hat, smiled and turned rapidly up the street. Bab mounted silently to his room, flung himself in the deep chair beside the fading fire and, taking his brow in his hand, mused over the mission he was embarked upon. He could not avoid falling into some exultation that he had been entrusted with an errand so nice and so important, and his apprehension, that he was to be the mere ignorant instrument to delude the Prince, had been largely removed by my Lord of Danby, whom he had known all his life and did not believe a guileful man. Besides, his own shrewdness showed him that the King had pushed the French interest in England as far as he durst; and unless he could disown the connection with Louis and placate the people with a Protestant marriage to the Princess Royal matters were like to be driven to a crisis Charles would be as reluctant to face as my Lord Danby.

And Baptist Mompesson's thoughts touched a nobler level: the King was the King, and of England; might he not in all honesty wish to aid his own blood, his country's faith? Bab thrilled at the contemplation of the struggle in the Low Countries which had been sustained four years against such unequal odds. He was not proud of the part his country had played and eager enough to see it redeemed by a change of policy; he disliked France and the arrogant King, who wished to cast the shadow of his sceptre over Europe.

Defender of the Faith!

The words haunted Bab's imagination; his Puritan blood hated the growing tyranny of Rome; his good English sense revolted at the subservience of the King to any foreign Power. He opened the window again, heedless of the chill breath from the snow-clouds above the roofs, where a faint moonlight glittered in the crystals, and gazed up into the spaces of dark blue with a fine uplift at the serenity and mystery of the scattered stars.

When he drew back into the room again he found the fire a mere heap of ashes, and one of the two candles guttered out in the draught. His eye was caught by my Lord of Danby's glittering dole which lay in a little heap on the letter of credit beneath the solitary candle.

He picked the pieces up, one at a time. "Clipped coin," he thought almost unconsciously as he looked at the uneven edges. The King's saturnine face smiled from a defaced blank.

The child's cradle packet-boat for Holland left Gravesend in a bitter cold wind that turned strongly to the south-west at the Hope, and put a day between that and Margate.

A brisk change to better weather sent them upon the coast of Holland, and Bab was in good hopes of landing on the third morning when a thick fog rose up with great swiftness and kept them stationed in the icy waters of the North Sea.

The packet carried the mail and one passenger beside Bab. He was an English clerk in employment at one of the great Amsterdam houses and had been to England to attend the death-bed of his father. Bab was quick to get this much from the captain; he had a lurking fear of Monsieur Barillon and his agents. The Englishman had not been seen since their embarkation at Gravesend; he lay in his cabin in the torture of seasickness and Bab had the ship to himself. Walking the deck in the fog that isolated them as completely as if they had been a thousand miles from land, he cast up his chances of success, all he had heard of the Prince to whom he was sent, all the arguments he should use, the care he must take to keep himself, quiet, free from curiosity or malice.

His tense thoughts were broken by some one stumbling forward on the spray-washed deck and catching his arm.

"Your pardon, Sir—but has the ship stopped?"

It was the other passenger. Bab looked at him keenly. He was a tall man, very plainly dressed in a mourning cloak of camlet, middle-aged, long-jawed, of a ghastly sallowness in the complexion, wearing a short peruke, and an old-fashioned hat.

"Certainly, do you not observe the fog?" Bab answered rather dryly.

The stranger groaned and clung to the taffrail as the ship lurched sideways into the white expanse of mist.

"I am no sailor," he confessed. "I have a great disease and sickness when on the sea."

"So it seems." Bab was concise. "Yet, having your employment in Holland, you must needs cross often."

"Not often," said the other feebly. "I forgo my country sooner."

It was all the converse they had, but Bab kept his eye on the man as he moved away up the deck.

In a few hours the fog lifted and a pilot came out in a rowing boat, and took them to the Brill. At Maaslandsluys the two passengers took a barge for the Hague, and in the unfriendly light of a dull afternoon were steered by two silent Dutchmen through the waterways of Holland.

Bab was reserved through design, and his companion through sickness; they sat wrapped in their cloaks with never a word between them till they reached the frozen canal where they had to leave the barge for a traineau. Then there was some question as to the transfer of their baggage, and Bab turned sharply to the stranger, "You must know the Dutch; will you speak to these fellows?"

The other discovered none of the confusion Bab had half expected; he addressed the porters in their own language, and so proved his advantage over Bab, who had neither Dutch nor German. As the traineau sped forward down the long canal the King's messenger almost decided that the sick passenger was no more than he declared himself to be, a clerk from Amsterdam.

Windy sea-clouds were blowing over the Hague as the Englishmen entered it, the trees were hung with snow, and the houses and churches were clear as a painting in the cold atmosphere.

Bab paid his way in the clipped English gold, and received a handful of heavy Dutch money in return. The town seemed very quiet, almost sleepy, not at all like the theatre of great events. A few boys were skating, a few people passing to and fro. When Bab stepped out of the traineau and found himself in the long neat street, a sense of depression overcame him; he seemed unaccountably far from the beginning of his mission and hopelessly far from its accomplishment.

My Lord Danby had given him the address of a house well used to accommodate English and Scotch refugees, but Bab, utterly strange to the town, resolved to stay the night, at least, in the modest hostel opposite the spot where the traineau landed him. This, it appeared, was also the intention of the other passenger, who declared himself far too sick to proceed that evening to Amsterdam. It occurred to Bab as strange that he had not travelled at once thither, without touching the Hague, and his doubts of the fellow rose even when he crept up to his room and was seen no more.

The inn was small, dark, slumberously quiet and notably clean; the black furniture in the parlour shone with a wax-like polish, and the brass about the fireplace where the pine logs blazed was of a silver paleness. The host was polite, quiet, able to speak French and a little English, and disposed to be friendly.

Bab, during his dinner of dried fish, cheese, cock-ale, and Deventer honey-cakes, obtained from him, under cover of the curiosity of an ordinary traveller, much information. The most important point was that the Prince ('Stadtholder,' the host called him, and the title sounded strange to Bab) was not at the Hague but at Dieren, a country seat of his outside Arnhem. He might return any day to attend the sitting of the States, but his movements were uncertain, his journeys unheralded. Since the close of the last campaign he had been mostly at Dieren or Honsholredijk, Bab was told, save the one week he had spent in Amsterdam in the endeavour to raise money for the war from that opulent but republican city.

The host spoke of the Prince with intense respect and affection; the losses of the last campaign he passed over as nothing to be set against the salvation of the country which the Prince had secured by his diplomacy and his valour. Bab, probing as much as he dared, was surprised at the power the Stadtholder appeared to enjoy, and the strong position he held in the United Provinces. The host said that his Highness was consulted in everything. He had remodelled the constitutions of the three provinces he had rescued from the French, and put the bridle even on Amsterdam; no one durst or wished to oppose his will. The East India Company had given him grateful presents, and Gelderland had offered him the sovereign title, which, however, was refused by a prudent Prince, who needed not the name when he had the power.

In return, said the host with animation, his Highness had made great sacrifices for his country: all the emoluments of his offices he had given the States for their defence, and his immense private fortune he was devoting to the same end; he had refused to conclude treaties for his own advantage, and his one thought and aim, since the ghastly year of '72, had been the deliverance of his country and his faith.

Bab was fired by this talk of the young Prince he had always admired. He thought of starting at once for Dieren, but considered that it might be wiser to wait at the Hague, and, since the dreary day was closing in and he had no object to serve in going abroad, he went to his room and read over the Lord Treasurer's instructions. The paper contained little he had not been told; the words of the olive-faced King remained his chief guide.

As he was opening his mails he heard a footstep outside the door. He paused instantly, put out his hand and quenched the one candle that dispelled the dusk. The handle was cautiously turned, and the face Bab had been expecting to see peeped in—it was that of the sick passenger.

The King's messenger kept still and silent, and the tall dark figure advanced into the room. When he was well over the threshold Bab sprang up from beside his portmantles.

"You are very clumsy, Sir," he said angrily.

The stranger gave a start. "Your indulgence," he answered feebly, "I have mistaken my room."

Bab Mompesson crossed over and turned the key in the lock. "You have mistaken your man," he said briefly.

"What do you mean?" quavered the stranger.

Bab had a pistol on the table; he placed his hand on it as he answered. "You are the Duke of York's spy, Sir," he said quietly. "You have been sent by his Highness to watch and circumvent me—and you were making a good beginning tonight by endeavouring to steal my papers."

The other hesitated, then laughed. "Very well," he answered in an utterly changed voice. "If you are the agent of one brother, may I not be the agent of the other?"

"I serve his Majesty," said Bab grimly. "I am glad you are so recovered of your sickness."

"Light the candles," suggested the stranger calmly, "and we will talk...You may take your hand off that pistol for I am unarmed. My name is Thomas Carew. I come from Berkshire—your county, I think, Mr. Mompesson."

As he spoke he seated himself in the cushioned chair by the glowing tiled stove, and smiled up at Bab, who lit the candles and placed them on the table. "You were doubtful of me from the first, were you not?" he asked. His manner was easy and pleasant; his heavy plain face held an expression of authority and composure. Bab disliked him intensely.

"You carry it off very well, Mr. Carew, but you have set yourself to a difficult game. If you know so much of my errand as to wish to circumvent it, you know that its success is the wish of the King and the people." He took his place behind the lights that gave a glowing fairness to his blunt Saxon features and rested his elbows on the table.

Mr. Carew fixed him with keen light eyes. "You have come to arrange a Protestant marriage between the Princess Royal and her cousin," he said in a low tone. "And I dare assure you, Mr. Mompesson, that you will never bring it about."

Bab set his lips. "Desist while you may and spare yourself some pains," continued Mr. Carew with weight.

Bab laughed shortly. "You waste your breath, Sir. Does his Highness of York carry such weight in the councils of Europe that he can prevent what England has resolved upon?"

The other's look deepened in meaning. "Behind the Duke of York is the King of France, and he will have the countries of Europe shaken like peas in a pan before he will permit the heiress of England to be united to his greatest enemy."

"Permit!" repeated Bab. "What do you, an Englishman, with such words? It is for King Charles and the Prince of Orange to say yes or no to this bargain, and if they cry quits and England is pleased, no other shall interfere."

He rose impatiently. "I know your intentions and you mine," he added, "and further speech does us no manner of good."

Mr. Carew looked at him over his shoulder. "You are resolved to go on'?"

"I am resolved to obey my master," was the short answer.

"Well," Mr. Carew rose with a little smile on his thin lips, "I think you are a very proper engine for the King's purpose, and I will tell my employer so."

Bab was slightly baffled by this. He eyed the other suspiciously. "You to your business, I to mine," he said grimly. "And I would be sorry to change with you. You are one of those who would catch us all in the French net, and make us slaves to the Pope of Rome."

"I am of the Romish faith," replied Mr. Carew, and his eyes showed angry; "so is the King's brother."

"So is not the King's niece," retorted Bab. "And remember we are in a Protestant country, Mr. Carew. The Prince, I take it, is not one to endure treasons and intrigues hatching in his dominions!"

"Would you care to speak of me to the English Ambassador'?" interrupted Mr. Carew.

Bab was taken aback by his knowledge of Danby's instructions to keep everything secret from Sir William Temple, but he put a bold face on it.

"I would speak of you to the Prince himself," he said.

Mr. Carew seemed amused. "I judge the Prince no more eager than the Duke for this match," he remarked, "and with both sides unwilling you are like to have a difficult task."

Bab was further angered that his adversary should also know the mind of the Princess Mary. "Your sly Papist talk will get no more of me," he said. "Only I warn you while we are on this soil I have a bit on you and shall not fail to tighten it."

Mr. Carew looked sourly. "If you would not be at cuffs with common sense, Mr. Mompesson, do not threaten one who has that behind him which is beyond your meddling."

Bab unlocked the door. "Get to your chamber," he said. "Neither you nor I make profit out of this talk."

The Romanist passed into the corridor and so, slowly, with a glance backwards over his shoulder, up the stairs.

Bab made the door secure, and went to the window to ease his temper by the cold sea wind on his brow. He was more annoyed than seemed reasonable to his own common sense at this instant discovery and espionage. He blamed the King for allowing his brother to so accurately plumb his intention; he blamed Danby (whom he had always considered a reckless politician) for some looseness that had disclosed his design to Barillon. Hampered at the very onset by an enemy at his heels, Bab's mind began to give audience to depressing fears and doubts. If the Prince was cold, the Duke unwilling, France inimical, the King lukewarm, and Danby tottering before the blast of an enraged Parliament, what chance had he of bringing to the ripening those schemes that he was entrusted with, the policies with which Charles had flattered his patriotism? Peace in Europe, the end of a disgraceful subservience to King Louis, succour to Holland, and the Protestant marriage to seal this and secure the future of the true faith.

Staring out over the various gables and roofs of the Hague, fast being blurred from his vision by the misty descent of night, Bab foresaw himself making a feeble and ineffectual figure in contradiction to the importance of his business, did he not exert all his wits.

He decided his first object must be to gain the Prince, and his cheek flushed as he recited in an under voice to the windy evening some of the powerful arguments he would place before his Highness, and the terms in which he would make clear to him the state of England, a country at odds with itself, outwardly corrupt, but true at heart.

The peaceful clear chimes of some great church Bab could not see broke the frosty stillness of the motionless town. Bab closed the window, walked about his room awhile, and finally unbolted the door and thrust a challenging head and shoulders on to the blackness of the corridor. The household was seemingly abed, and though Bab swept the darkness with his fat yellow candle he saw no trace of Mr. Carew. As he stood there, silent, it occurred to him with sudden force that for a man of astuteness it was a very foolish thing to make that almost open attempt to enter the room of the person supposed to be deceived, and still more foolish to suppose that one on such an errand, in a strange place, would leave about anything worth the endeavour to steal.

This reflection discomposed Bab; he felt that there was some meaning deeper and much more subtle than any apparent as yet in the behaviour of the sick passenger.

By the middle of the next day Bab had left the "Panier d'Or" and taken up his lodgings in the quarters mentioned by Danby, a fine house in the Princengracht, kept by one Mevrouw Vanderhooven, the Scotch widow of a Dutch merchant, who let chambers or offered asylum to such of her countrymen or others of the true faith who had fled the persecutions in the Scottish Lowlands or elsewhere.

Bab was given a room at the top of the house, looking on to the trees and the wide canal, now frozen, that ran out of the town toward Ryswyck. It was a pleasant apartment, the windows clear as crystal, floor and walls polished to an amber hue, curtains and bed hangings of white checkered with blue, a big stove of painted tiles and fresh linen covers to protect the seats of the shining chairs.

Mevrouw Vanderhooven was friendly if stern. She spoke sharply but with good intention. She was stout, forty-five and plain; her cap and collar were of a whiteness so glossy and pure that her brick-dust complexion and red hair glared by contrast; her course hands were deft at woman's work; her large feet nimble about the house. She prided herself upon having no weaknesses, "vanities" she called them, but she tolerated a fat grey cat that had no pretensions to respect, and she had been know to sit up all night with a one-eyed, asthmatic parrot her husband had brought home from Jamaica twelve years before. Her real and unobtrusive charity gave shelter to a sour and precise minister, named Fear-the-Foe Gibbons, who had been at his glory under the Lord Protector;' a Flemish jewel-worker and his daughter, ruined by the French occupation of the Spanish Netherlands; one of Cromwell's former officers in delicate health, who gave lessons in fencing; an old woman from Overyssel, who had lost her family in '72; and an English adventurer, exiled for his remarks on the King of England.

These people, who all seemed to Bab disagreeable and uninteresting, occupied the lower part of the house under the strict government of Mevrouw Vanderhooven, who checked with a firm hand their quarrellings and arguments, endured their complaints and joined in their endless prayers, toiled for them and obtained little thanks.

The upper part of the house was let to an old man who was one of the elders at the Groote Kerk,3 single and reserved, a young widow who did fine needlework, and a German gentleman, at present in Berlin. In the attics where the servants slept was a room that led to a small tower on the roof; this was occupied by a wrestler or tuner of stringed instruments, who owned a beautiful clavichord. He dared play only when the rest of the household were out of earshot, they being unanimous in declaring it an ungodly device.

Bab, having discovered this much of the people under the same roof, laughed inwardly at the motley crowd he found himself among, requested his meals might be served privately, and left the house with the key of his room in his pocket.

The sharp eyes of Fear-the-Foe Gibbons followed him from the tall lower window, and the Huguenot jeweller squinted from behind the gaunt shoulders of the Scotchman. Bab, glancing hack, gave them a smile that was not returned, and passed on to the left, toward the centre of the town. The wide streets, the handsome houses, the trees and open spaces, the shining windows with their outside mirrors, the clean steps and polished handles of the high doors, were a cause of marvel to the Englishman used to the crooked thoroughfares and filthy by-ways of London and Paris.

The people were well dressed though with a markedly quiet taste, the shops fine and numerous. Bab saw no sign of the effects of the war that had threatened to ruin the country four years ago, though he marked various figures such as he had seen in Mevrouw Vanderhooven's house, refugees showing more or less pride and poverty, wounds and rags.

There were several skaters on the canals, sledges for business or pleasure, drawn by ponies, and little ships blown along the ice by the wind in their great sails.

Bab came to the very centre of the town, saw for the first time the Binnenhof, the Buitenhof, and the Gevangenpoort, buildings stately and sombre and built round the Vyverberg lake, where now the swans walked slowly on the ice. Passing under the dark archway of the prison he came out into the Plaats, and so down the Kneuterdyck Avenue and into the Voorhout, filled at this hour with carriages and fashionable people, moreover in itself the finest street with the most lordly houses that Bab had ever seen. Among the passers-by he discerned Mr. Carew, the Papist spy, walking leisurely, and at that sight hastened his steps and so got out of the press through the Tournooiveld into a quieter street, having no desire to be under the observation of his enemy. A few steps brought him to a street of fine villas, white-fronted, planted with very tall trees; beyond the houses spread a large park or wood.

Bab crossed and followed the road. A great gate stood open on a wide drive, and a little group of gentlemen on horseback were talking to some men at the entrance of a small lodge or guard-house. It seemed to Bab to be a public garden. He turned through the gate and passed unchallenged down a beautiful double and lofty avenue of fine trees. The ground was thick with brown dried leaves, the path hard with frost; the thousand branches that mingled together against the grey sky were delicately outlined in snow, which also lay in patches here and there among the undergrowth.

Bab walked briskly, enjoying it; where the avenue ended he took one of the many paths and came into a portion of the wood in its natural state. Holly grew among the dried ferns; firs and yews made patches of green-blue of velvet softness against the burnished and dead hues of bare branches and faded foliage; a quantity of rooks clamoured harsh converse, and small birds flew across his way with a startled stir of wings.

Presently the clouds broke and clear silver-gold rays fell across the beech-boles and glittered in the snowdrifts.

Bab, following his path, found himself on a bank overlooking a lake that curved out of sight. A graceful beech, hung with moss, drooped above the frozen water, on which the curling gilt leaves fluttered above the sparkling rime; beyond this a group of high trees bounded Bab's vision. It was so solitary, so still, so pleasing that Bab almost unconsciously slackened his steps, and finally, becoming impatient even of his own footsteps, seated himself on the stump of an ancient tree, twisted with reddened ivy, and gazed at the sweep of ice, the silver-green trunks, the twisted, shrivelled bracken, the whole dead and lovely scene.

So remote did the place seem that he was startled when the distant chimes of the Groote Kerk reminded him of his vicinity to a town, and unreasonably surprised when a young man skated suddenly round the bend of the lake. He instantly reflected, however, that this must be a common resort, and wondered he had not seen more skaters.

With the curiosity of the idle, Bab noted the stranger's appearance as he approached through the pale sunlight under the shadows of the beech-trees. He was slight, of the middle height, and carried a large sable muff; his face was concealed by a leaf hat with a plain buckle; he wore a claret-coloured coat, fur-lined, and high soft boots. As he turned toward Bab he held the muff up to his face as a screen against the sharp wind.

Bab was struck by something heavy and foreign about the stranger's dress, then by the perfection of his skating, and he debated if he should give him greeting, and get into speech with him, seeing they were alone in the quiet landscape, when the new-comer lowered the muff and raised his head.

Observing Bab he stopped instantly and said something in Dutch.

The Englishman shook his head and smiled. "Good day," he answered pleasantly. "And if you know no tongue but that we should not hold a long converse."

The other took a half-turn about the ice and came to a stand below the spot where Bab sat. "What is your business here?" he asked in English, marked with only a slight accent.

"None at all," replied Bab frankly. "I had time on my hands and came here for pleasure, Sir. I am a stranger to the Hague."

"English?" asked the skater briefly.

"As you see."

"How did you get in?"

"Into the park?" smiled Bab. "Through the gate."

The young man reflected a moment while the light wind fluttered his hair and cravat. "Are you skating?" he inquired at length.

"No," said Bab, who thought him dry beyond politeness.

"Can you?"

"No," said Bab again.

For the first time the stranger looked up at him. "These are private grounds," he remarked, "and you have no manner of right here."

Bab was taken aback, but composed. "I'm sorry," he said. "Is this your land, Sir?"

"I come from the house."

"Where is it?" asked Bab with interest.

"Near—through the trees there." As he spoke he sat down on the bank and unstrapped his blade skates that glittered strongly through the clog of snow.

Bab rose. "I had no wish to trespass," he said good-humouredly. "I thought it public like the Mall. I only came to the Hague yesterday."

The young man, with the skates in one hand, sprang lightly up the bank and stood beside Bab. "What business have you in Holland?" he asked gravely.

"My own," said Bab quietly.

"Your reserve discovers prudence," returned the other. "Is your affair as weighty as it is secret?"

Bab looked at him closely. He had a majestic and manly countenance, remarkable eyes and thick curling hair of a dark brown; a likeness in the face to someone he had known troubled Bab.

"I am a mere traveller who comes to the Hague out of curiosity," he replied.

"Curiosity!" returned the other scornfully. "Who journeys to Holland out of curiosity!"

"I, certainly," said Bab; then with an attempt to shift the conversation; "You speak English extremely well, Sir."

The compliment did not seem to please. "My mother was English," was the indifferent answer. "Are you long for the Hague?"

Bab made a light response. "Until my curiosity is satisfied."

"Are you known to Sir William Temple?"

"No, not at all," replied Bab, half annoyed at these repeated questions.

"He is at Nymegen now," remarked the other, "attending the Peace Congress the King of England holds there. I though it might be that you waited his return."

"No—my residence here depends not on politics," said Bab, wondering why a stranger should take interest in his movements.

The young gentleman shivered. "Let us walk on," he said, fastened his skates together over his arm and thrust his hands deeply into his muff.

"Your weather is extremely cold," remarked Bab as they followed the narrow path above the bank, "but in London it has been worse."

"Yes, the packets have been delayed," was the brief answer.

Bab did not quite know how to continue. He judged his companion a gentleman, perhaps an officer of some rank, and imagined an acquaintance with him might prove useful; but he found him difficult to talk with.

"You live at the Hague?" he hazarded.

"Yes—where are you staying?"

"In the Princengracht."

"Ah, at the house of one Widow Vanderhooven."

Bab assented, surprised. "You know the place?"

"I know it as a house frequented by English and other refugees."

"A strange gathering," laughed Bab.

"Not a house an ordinary traveller was like to hear of," remarked his companion dryly.

Bab reddened. "You appear to suspect me of some far-reaching design," he returned.

The other was silent, and the King's messenger glanced doubtfully at his delicate and haughty profile. He thought the young man not more than twenty-four or twenty-five, yet the gravity of his expression and the stateliness of his manner were not in keeping with youth; he had an unfriendly air of gloom, yet the arresting attraction of composure and authority. Bab felt that this talk was not purposeless, that he had some design in his action, and so came quietly.

The path curved suddenly round the water and Bab saw, at the end of a short avenue, a white house with a high flight of steps shaded from the winter sun by the bare boughs of the snow-glittering trees.

The young man stopped and turned his clear, deep glance on Bab. "If your affair is what I think it," he said shortly, "it is ill served by delays and misunderstandings." He paused, coughed, and gave a half-resentful glance at the snow-clouds that were obscuring the sun. "You are Mr. Baptist Mompesson," he continued, "my Lord Danby's private agent."

Bab flushed and stared at the speaker. "How can you possibly come by that knowledge?" he demanded.

The young man answered brusquely: "I am the Stadtholder I came back from Dieren yesterday. This is my house; if you will come in, I will look into your business."

Bab was so amazed that he stammered like a startled child and stood foolishly.

"I perceive that you are not a very accomplished courtier," said the Prince, "but I think you do not come on an embassy of compliments."

Bab uncovered. "Your Highness had me unawares," he said simply. "Sure, I cannot mind me in a moment of my wits."

The sun was now completely veiled in sullen glooming clouds. The Prince turned down the bare avenue. He said no more to Bab, who followed, his hat in his hand, by no means pleased with this sudden and informal audience and overawed by the quiet haughtiness of the Stadtholder, whose manner showed no friendliness.

William ascended the steps slowly, and Bab came behind him into a small vestibule with a marble floor, where a clock ticked primly and dark portraits showed conspicuous on the light painted walls. The Prince put down his skates, his hat and muff on one of the chairs; the same silence that filled the wood was over the house. William opened the door to their right and Bab followed him into a small room very plainly furnished.

"You may wait here," said the Prince, and was leaving, when at the door he turned. "You have your papers."

Bab handed Lord Danby's letter, the Prince gave it an indifferent glance and returned it, departed and closed the door. Bab felt that the King of England's messenger might have had a more gracious reception; he was prepared to dislike the Prince. The room in which he waited had the air almost of a dissenting church, it was so prim, so neat and severe. The only picture was a large, sober, stormy landscape that occupied the whole of the chimney-shaft; the chairs had leather backs and seats fastened with brass nails; the wall was panelled half-way up in a linen pattern of carving, above the moulding it rose plain to the ceiling, the large crossway beams of which were finished by little shields bearing the arms of Nassau.

Bab contemplated these details with an unfriendly eye; his father had been a Puritan, but his own instincts were not for severity. The Prince was different from what he had fancied him, different from any one he had ever spoken to, and the strangeness and foreign atmosphere of master and house depressed him. He sat glaring at the vista of leafless trees through the polished window against which a few flakes of snow were falling.

It was half an hour before the Prince returned accompanied by two gentlemen as silent as himself, one young and noticeably handsome, the other very grave and older.

"Mynheer Bentinck and Mynheer Dyckfelt," said the Prince briefly. "And now, Mr. Mompesson, we will hear what you have to say," Bab had risen on their entrance. William motioned him back to his seat.

The two Dutch nobles and the Stadtholder took the stiff chairs at the table; Bab eyed them with a sinking courage. "Your Highness will understand..." he began.

William interrupted. "Make not your discourse a chime of empty words, Mr. Mompesson; we are so pressed with great business that we are wishful to come to the heart of this matter."

Bab bowed. "Yet I must be so bold as to ask Your Highness to allow that no business can be greater than that I am charged with."

William glanced at Bentinck, who gave a slight shrug. Bab was nettled.

"I am King Charles' messenger," he said, "and I was bid ask a private audience."

"These are my friends," replied the Stadtholder. "His majesty would not be secret from them, I think, but from the States." He had a slow impressive manner of speech that carried great weight, and a soft voice though it sounded weak and strained. Bab, observing him now without his beaver, thought he looked fatigued to the point of sickness, though he was not pale but had a clear, tanned complexion and eyes marvelously brilliant and alert; as he spoke he took his brow in his hand and rested his elbow on the table. "Why did my Lord Danby choose you for this mission?" he asked suddenly.

"It is difficult to say, Sir," returned Bab frankly. "Before my lord grew to such a height we were something friends, being both on the King's side, though Protestant and I of a Puritan family—but, more than that, my noble lord, his Majesty said to me: 'As you are an honest, plain dealing man who believes in God, I will trust you to convince his Highness better than a glib courtier.'"

Mynheer Dyckfelt smiled across the table at Mynheer Bentinck; the Stadtholder moved his head so that the thick chestnut hair concealed his countenance from Bab and answered quietly: "What was the bottom of his Majesty's desire in this journey of yours, Mr. Mompesson? Sir William has my full confidence. There has been many a messenger going to and fro King Charles and me since this weary war began, and none of them has wrought any good."

An earnest look sprang into Bab's blue eyes. "Sir, I have it greatly at heart to carry through the King's wish, for it is the wish also of Parliament and of England."

The Prince did not move, even by a little. "Would my uncle have peace in Europe?" he asked quietly.

"He must have peace," answered Bab. "The Parliament presses and the people clamour. Is it to our advantage to see France striding across the continent, our faith whipped with fire and sword?"

The Prince looked up, he was suddenly pale, his large eyes dark and glittering. "Does my uncle see that, at last?" he asked with a proud bitterness. "At last! He is afraid of France, would patch a timid peace—but that will not help us. I tell you, Mr. Mompesson, had my uncle aided me, even with a thousand men, in '72, he had not need to dread France now." He spoke with a force, an emotion that held Bab silent; with yet a deeper passion in his contained voice he continued: "I speak very freely to you, Sir, for I doubt not you know the mind of the King, therefore it is as well that you should gauge mine. In my desperate extremity, England held back from me and leagued with my enemies—I have been pushed to the very verge of despair and only by God's grace am I sustained—and it is always my uncle who has dipped the balance against me. Now, fearful of France, fearful of his people, he would force a peace, but we who have endured so far can endure to the end, Mr. Mompesson."

He paused in an exhausted fashion and pressed his Frisian lace handkerchief to his lips.

"The King has done with France," said Bab warmly. "I am no courtier, Sir. I loathe the King's policy. I would he had helped you in '72—but it is not too late."

"It is very well to talk of peace," returned William. "But on what terms?"

"With England on your side you could make the terms," answered Bab. "This is the main object of my embassy—to offer Your Highness, as guarantee of the King's faith, the hand of the Princess Royal."

Bentinck looked at the Prince, who kept his glance fixed on the table.

"That proposal was made me by my Lord Arlington in '76," he said.

"Affairs have changed since '76, Your Highness."

William shot him a long look. "You mean that then I had not been beaten so often by the French? It does not make me any easier to be bought, Mr. Mompesson."

"Not bought, Sir—it would be the triumph of your policy, a blow in the face for France."

"And the price?"

"Peace, Your Highness."

"On the terms of France," said the Prince. "Mr. Mompesson, I stand alone in what I do. Doubtless my task seems impossible and the King's offer brilliant, but I should be the most miserable man alive if I should accept it. I am pledged to my country, my allies, my conscience to continue this war until death or justice end it..."

"Justice!" Bab caught at the word. "The King will see justice done."

The Prince's eyes were contemptuous and Bab flushed. "England will see justice done," he amended proudly. "England admires and loves Your Highness—England would stand by you against Papist Tyranny."

"Assure me that and Europe is saved," said William.

"This match will assure it to Your Highness."

"Is the treaty or the wedding to come first?" asked the Stadtholder.

The King's messenger could not mistake the disdainful curve of his mouth.

"Your Highness does not trust England nor me," he said. "I will ask you reflect a little. My Lord Danby has pledged his position on this policy."

Bentinck spoke for the first time. "Her Highness is heiress of England. What does her father the Duke think of a Protestant match for her, when he desires to establish his own faith?"

"The Duke's will would bend to the will of the nation, my lord."

The Prince's face softened into a half-smile. "What does my cousin think of this bargain?" he said irrelevantly.

Bab was so unprepared for this from the Stadtholder's gravity that he replied awkwardly: "Her Highness is very youthful—her mind is still changeable."

"Which means she likes not what she has heard of me," said William calmly. "I recall her as a wilful child some seven years ago when I was in England. I think a lady from my uncle's house is scarce like to favour me. But this is early talking only; all else aside, I have a fancy to marry where my liking goes and should wish my wife to be of that mind."

In his heart Bab thought the fair and headstrong Princess, untaught and lively, was not likely to be attracted by this austere young man. It seemed to him that small happiness for either would lie in the match, but the domestic aspect of the affair was not his concern.

"This marriage would bring Your Highness one nearer the throne and give you immense weight in England," he said eagerly. "To one of already such power in the Councils of Europe that must have weight..."

The Stadtholder looked at him intently. "Mr. Mompesson, this is not a personal matter. I could have made separate treaties to my own advantage any year since the war began. What is my advancement compared to the great issues involved?"

"Does not Your Highness desire peace?" asked Bab tentatively.

"On just terms, yes."

"What terms?"

"The Peace of Munster established the balance of power in Europe. When France will return to that I will sign a peace."

"France never would," was surprised from Bab.

"Then let the war continue."

"To what end?" asked Bab. "Your Highness can scarce have ultimate success."

"Men have said that to me before, Mr. Mompesson," said the Stadtholder calmly. "It were an ill symptom in me if I listened to these discouragements."

"My sentence was incomplete," answered Bab. "I would say, Sir, that you can hardly come to final victory without the aid of England."

"I may achieve my end by the grace of God and my own will," returned the Prince. "What are outside aids compared to inner strength?" He rose abruptly, and the others got to their feet.

"Your Highness makes a scorn of my mission," said Bab mortified.

The Prince glanced at his friends and smiled quietly. "We must talk on this subject again, Mr. Mompesson. I have to see some of the States, now, privately," he said. "I have writ to his Majesty that you may have my reply in a few days—wait upon me again shortly."

Bab felt that he had so far failed; he had a sense of unfriendliness and prejudice on the Prince's part. Even the King's warnings had not prepared him for this unmoved distrust of England; he was overawed by the Stadtholder and resented the two silent Dutch nobles, who bent such odd glances on him. He bowed, accepting his stiff dismissal; William gave him the briefest nod, and crossed to the window with his back to the room.

As Bab closed the heavy door he heard the Prince laugh maliciously, as if he had discomfited one he disliked, and make some remark in his own language that Bab took to be a slighting stricture on himself. The Englishman was humiliated and genuinely cast down; he stood for a moment in the light-vestibule forcing his composure.