RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a portait of Suzanna Doublet-Huygens

by Caspar Netscher (circa 1639-1684)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a portait of Suzanna Doublet-Huygens

by Caspar Netscher (circa 1639-1684)

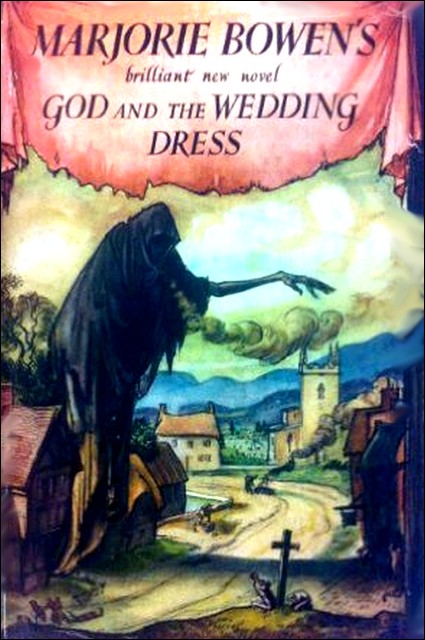

"God and the Wedding Dress," Hutchinson & Co., London, 1938

Let it suffice, at length thy fits And lusts—said He—

Have had their wish and way;

Press not to be

Still thy own foe and mine; for to this day I did delay

And would not see, but chose to wink;

Nay, at the very brink

And edge of all,

When thou would'st fall,

My love twist held thee up, my unseen link.

I know thee well; for I have fram'd

And hate thee not;

Thy spirit too is mine;

I know thy lot,

Extent, and end, for my hand drew the line

Assigned thine;

If then thou wouldst unto my seat,

'Tis not the applause and feat

Of dust and clay

Leads to that way

But from these follies a resolv'd retreat.

—Henry Vaughan.

"I cry'd out: Well, I know not what to do, Lord direct me! and the like... and casting my eye on the 91st Psalm, I read to 7th verse exclusive and, after that, included the 10th, as follows:

'I will say of the Lord, He is my refuge and my fortress: my God; in Him will I trust. Surely He shall deliver thee from the snare of the fowler, and from the noisome pestilence. He shall cover thee with His feathers, and under His wings shalt thou trust: His truth shall be thy shield and buckler. Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night, nor for the arrow that flieth by day. Nor for the pestilence that walketh in darkness, nor for the destruction that wasteth at noonday. A. thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand; but it shall not come nigh thee. Only with thine eyes shalt thou behold, and see the reward of the wicked. Because thou hast made the Lord, which is my refuge, even the Most High, thy habitation. There shall no evil befall they neither shall any plague come nigh thy dwelling'...

from that moment I resolved that I would stay in the town and, casting myself entirely upon the goodness and protection of the Almighty, would not seek any other shelter whatever. And that, as my times were in His hands, He was as able to keep me in a time of infection as in a time of health, and if He did not think fit to deliver me, still I was in His hands and it was meet He should do with me as seemed good to Him."

The History of the Great Plague in London in the Year

1665.

—Daniel Defoe. (7b Pages 15-16, Edition 1920.)

THERE are so many different kinds of historical stories and this author has tried most of them, so it is as well to make clear what has been attempted in this novel. The shell of the tale is true and concerns an incident fairly well known, though perhaps better known a hundred years ago than it is to-day. It has served to illustrate many moral poems and anecdotes, which are now as forgotten as the morality they expressed.

But the details of this episode of country life in the reign of Charles II are sparse and rest largely on legend and conjecture. The characters, too, are shadowy, mere names and labels, most of them.

None of this matters beside the spiritual truth that emerges; in that remote Derbyshire village nearly three hundred years ago, a man did try to serve his God to the best of his belief and at a terrible cost to himself and others. This action was such as to make him a hero in the eyes of the single-minded, a fool in the opinion of those who have the knowledge he could not have possessed.

He believed that he was following divine instructions. From a worldly point of view he was doing things as foolish as they were brave.

Here is good matter for study, a moving, inspiring subject; can there be a more important one than a man's sincere dealings with his God?

The background and the details have been given as much verisimilitude in time and place as the writer could achieve; such history as is introduced would pass muster in the school books, it is hoped. But the main theme is the spiritual adventure of the young man who was convinced he knew the will of God. Some readers may detect echoes of Henry Vaughan in the story; such verses as are quoted are his, as are the very beautiful lines above. The writer felt that Vaughan was the perfect expression in poetry of the spirit that moved the hero of this tale, and the poet was but a few years earlier in date than the priest, so that they share the same contemporary colouring. The letters given in this book are from originals supposed to be genuine, but unfortunately stilted and affected as well as dubious. The writer has ventured to recast them into a more sympathetic and fluid form.

The medical details, in this case so important, are given on medical authority; the principal book consulted being that by Dr. Charles Creighton: Epidemics in Britain. The rest of the material had to be gathered from old guide-books, magazines, and memoirs long since out of print.

"IF they do not know, do not inform them, but it seems incredible that they are in ignorance."

"Sir, I dare assure you that it is so—these people live as isolated an existence as if they resided in Muscovy."

"You speak in pity, Mr. Mompesson? You think them, perhaps, savages?"

"Sir, that they are rude, wild and unlettered, there can be no doubt."

"They have immortal souls, Mr. Mompesson."

"I should have said that, my Lord," replied the young clergyman with a look and an accent steady and quick.

"No, it was I who was impertinent to remind you. See, your son's craft has capsized and you must make him another—"

"—out of the pages of my sermons, my Lord."

Mr. Mompesson took a packet of manuscript from his pocket and deftly fashioned, by folding the paper, a little ship; the two men stood by the banks of a stream that eddied swiftly down a gradual hill, the clear water impeded here and there by glistening stones. Limestone rocks, thickly grown with fine ferns and glossy ivy rose on either side of the dell that was surrounded by trees that almost shut out the distant mountains that rose purple and cloud-veiled behind them.

A child of four years of age sat on the edge of the stream and watched his father fashion his new toy; the first paper ship, water-logged, had foundered in the current.

"I irk you, sir, with my childish occupations," said the young clergyman. "Your Lordship will think that Eyam has gotten an idle pastor."

The Earl regarded the speaker shrewdly.

"I am your friend," he replied quietly, and watched the launching of the paper boat, on which, in a fine careful hand, the words 'Thou hast made the desert blossom as the rose' were clearly visible.

The July day was warm, the hill air sweet with the pure scent of the wild thyme and mint, which showed their blue and purple flowers by the banks of the stream; a soft wind stirred the upper boughs of the crest of trees that overhung the dale; the two men and the child, as if entranced by the summer languor, watched the paper boat taken slowly, with a gallant dignity, down the current.

The Earl, who was the elder by twenty years or more, was a man still in the prime of life, but marked by fatigue, hardship and anxiety. He had known war, exile and poverty; but four years ago he had been living in miserable penury abroad; now he was restored to something more than his ancestral honours and he had been recently appointed Lord-Lieutenant of Derby. With little taste for Court life, the Earl of Devon resided during most of the year at Chatsworth, the antique and noble building that stood amid the dignity of the wide park through which this stream flowed; the Earl was a quiet, careful man, of whom little was known, so earnest had he been to avoid disputes or strivings with his fellows; his attire was plain, he wore his graying hair cut to the shoulders and might have been his own steward as he stood thoughtful among the knee-high flowers and grasses.

William Mompesson, on the other hand, looked above his station; his gray cloth was of the finest make, his bands of delicate lawn, his whole air full of elegance and grace; moreover, he was brilliantly handsome, his patrician and slightly aquiline features shaded by thick auburn curls. Had not his bearing been grave and slightly aloof, he would have appeared no more than what he had hitherto been, chaplain in the household of a great gentleman.

"Why did you enter the Church, Mr. Mompesson?" asked the Earl suddenly.

The dell was full of echoes, and the question, asked in a slightly raised voice, was repeated in hollow tones: "—the Church, Mr. Mompesson?"

"You hear the echoes?" smiled the young clergyman. "How am I to answer so many at once? Surely I did not enter it for preferment—since I am sent into the wilderness."

"That was my thought," said the Earl bluntly. "I should have thought, with your gifts and scholarship, family and friends, you might have hoped for a better cure than Eyam."

"Sir, it was in my patron's gift, he offered it and I took it."

The Earl was not sure whether Mr. Mompesson spoke lightly or in rebuke.

"And your wife, does she take kindly to this rural life?"

"Kate is, as I think, happy."

"Do not then, disturb her, with talk of what is happening in London. She has no friends there?"

"None, my Lord. Her family were at Cockpen, Durham, and her parents are dead. An uncle in York City is all she has."

"There is no chance that she should write to London or receive a letter from there?"

"None, my Lord, indeed."

"Nor her sister?"

"Bessie still less than Kate has any acquaintance at London. Have no fear, my Lord. I shall neither send nor receive anything for a time. Indeed, since I came to the North, I have lost my friends there."

"Very well. And no doubt it is fantastic that a mere letter, save that it came from an infected house... But our wise men can tell us very little of these matters."

"I have studied them. I thought once to be a physician," said Mr. Mompesson unexpectedly. "It is still a foggy science. But for infection, I would not trust a scrap of rag—came it never so many miles."

"Some hold that opinion." The Earl wished to probe into the character and attainments of this attractive man who deeply interested him. "I did not know, Mr. Mompesson, that you followed this modern fashion of chemical experiments and medicine."

"I have done very little, I assure you, sir."

"I rather held you to be a scholar. Sir George Savile told me you were translating Plautus."

"Again," smiled the young clergyman, "I must say—I have done very little."

"You are, sir, over-diffident. I take my leave. Let me welcome you at my house soon. You are lucky, sir, to have your son beside you. Mine is at sea and even now engaged, maybe, with the Dutch."

"I will pray for him, my Lord." Mr. Mompesson bade the little boy rise and salute the Earl, and then stood thoughtful when the boy had gone back to his play, regarding the thick-set figure of the elder man as he walked quickly down the winding path that led to Chatsworth.

In such company the young clergyman was at home; he came from an old Nottingham family of Norman extraction and had received a liberal education. When he had left Peterhouse College, he had obtained, through influence, the post of chaplain to Sir George Savile at Rufford Park and had attended him there or at Thornhill, Yorkshire, and had lived a life of elegance, ease and refinement such as best suited his temperament. His content had been completed by his early marriage to a docile and fair young gentlewoman, Catherine Carr of Cockpen, Durham, who had given him two fine children.

William Mompesson had sometimes accompanied his patron to London and thus had seen something of vice, movement, and novelty of the times, and how men strove both for good and bad, and women clung to their coat skirts impeding them with clamour, or put a staff into their hands and helped them along with noble words.

He remembered little of the Rebellion; he had been a child when the late king was beheaded, but he could recall the hurry, the anxiety, the dread of civil war; the sour clash of opinion on how God was to be served and understood. He recalled, too, the universal joy when the present Charles had returned to his own, and how the prospects for a young royalist student at Cambridge had brightened, and how soon afterwards he had come by his early living, because he was a gentleman bearing arms, well-bred and comely.

Mr. Mompesson much admired Sir George Savile, who was brilliant, witty and wise, and who had taught him to despise the tricks and superstitions of mankind and to disdain the grossness of the self-seekers, the panders, jobbers and wittols who cluttered up all approaches to authority. Sir George had drawn his young chaplain's attention to the delights of Attic philosophy, the exquisite pleasures of music, classical learning, chess and horsemanship.

There were those who said that Sir George was too much of a philosopher to be a good Christian, there were those who taxed him to his face with being an utter disbeliever, but for them he always had the same reply: 'None but a fool is an atheist,' and reminded them of the Holy Bible, where the saying is written: 'The fool hath said in his heart there is no God.'

"Come home, George," said Mr. Mompesson, rousing himself from his reverie and observing that the Earl was now out of sight. "We spend too much time idling, you and I."

The child raised his head and marked with delight the echo that, absorbed in his sport, he had not before observed.

"Sir, we stay," he protested; and cupping his fat hands round his mouth, gave stammering cries to the echoes of the glen.

Mr. Mompesson readily lingered in this sweet solitude that had that elegant luxury (to his mind) to which he was too well used; the dell was as fine as the great music-room at Rufford Park. Only when he came upon the dwellings of his rude flock was the young clergyman offended. He did not wish to return to his own house, the meanness of which vexed him. Kate and Bessie were, moreover, distracted with the feminine business attendant on the approaching wedding and he had no part in that, nor was he much at ease about that marriage.

While his child shouted through the trumpet of his hands, William Mompesson's thoughts returned with pleasure to his old life at Rufford Park and with vexation to his magnificent patron, Sir George Savile. Why had that great gentleman so encouraged and flattered him, laying him, as it were, on silk and feeding him with honey for five years, only at last to say: 'Why, Mr. Mompesson, here is the living of Eyam vacant by the death of Sherland Adams, who was a quarrelsome rogue. And it is yours.'

It would have been to many men a sentence of banishment, for the mountain village was remote and wild, and the people had been much neglected by their late pastor, who, after being suspended by Cromwell, had returned to his charge, a bitter, broken man. But at first William Mompesson had been glad to leave his golden servitude, for he had been discontented with his fastidious sheltered life and eager to exercise his energy and his gifts.

He smiled now as he thought of that flash of enthusiasm. There were no opportunities in Eyam for a man like himself. Though this was the country where his family had lived since the Norman Conquest, he had no knowledge of these hills, this rural life, these people, rude, superstitious, coarse and troublesome, who neither had, nor wished to have, any connection with the outer world. People who had hardly heard of London, whose imaginations went no further than Bakewell, and to whom the Earl of Devonshire in Chatsworth was more important than the King.

'What can I get into their thick heads?' he thought. 'What use is learning, or love of God, or holiness, or wit and enthusiasm here?'

He frowned slightly as he pondered over the part that Sir George had taken in this; had that subtle man thought that his young chaplain was becoming effeminate and pampered? Had he, with that sparkle of delicate malice which sometimes lit his urbane detachment, decided to put William Mompesson to the proof?

'Perhaps he was tired of me; perhaps he recalled that I was his dependent and might be dismissed. And took this way of doing so, courteously.'

The young man's sensitive mind was galled, not only because he detected a hidden rebuke in this banishment to this desolate post, but because he detected failure in himself. He had always believed that he was sincerely religious and that he longed to prove it. Now he knew that he regretted Rufford Park and Thornhill and was depressed—even disgusted—by Eyam.

His chance meeting with the Earl of Devonshire to whom Sir George had warmly recommended him, had stabbed him with regret for the old days when he had enjoyed as of right the company of such men and the luxuries with which they surrounded themselves. True, my Lord had been gracious, but William Mompesson knew that an occasional visit to the great man's establishment would not assuage his longing for the life that he had left.

Other considerations crossed his mind; he was a poor man. His parents, both dead, had been ruined by the civil war and what they had left him had been almost exhausted by the expenses of his education. He had not above forty pounds a year, nor was his wife in better case; the late troubles had left her orphaned and sucked up her family's substance, and she had no near relative beyond Mr. John Beilby, a gentleman possessing a small estate outside York.

And there was little George to educate—'he must go to Cambridge'—and little Bessie to portion—'she must marry a gentleman.' So, on these grounds alone, the young man was well advised to accept the rectorship of Eyam and the stipend of one penny per lot—every thirteenth dish—of ore obtained from the lead mines that, together with the manor of Eyam, had come to Sir George Savile from his great-aunt, the Countess of Pembroke. Nor was this tithe mean; the income varied from three hundred to nearly five hundred pounds a year and more than sufficed for any possible expenditure that could be made in this place.

"It will provide for you, your wife and children," Sir George had said, and William Mompesson resented the money that was the base lure to hold him in this wilderness.

'Am I to die here?' he thought, with a touch of wildness and glanced round at the sloping banks of the little glen, at the crest of trees and at the mountains beyond as if he surveyed prison walls.

He had heard how, in the old days, one parson would stay all his life in one parish—how many years?—he had lived but twenty-six himself, forty more would scarcely see his span out.

Surely the Earl had looked at him shrewdly, wondering what a man of his parts was doing here. Why had he not become a scholar attached to his beloved University, a soldier with the world before him, a curious experimenter in medicine and chemistry? There were livelihoods to be obtained through any of these vocations.

William Mompesson knew why he had taken Holy Orders. It was because he had felt a searing enthusiasm for God.

He knew also why he had accepted the chaplaincy with Sir George Savile. It was because he had been tempted by the insidious, not ignoble, bribes offered by life in a magnificent household where intelligence, taste, fondness for beauty, ease, wit and refinement were gratified to the full.

As he now pondered over his case, he realized as he had never realized before, how that early, sweet and delicate love of God had dwindled and been almost smothered during the five years he had spent in attendance on this splendid and dangerous patron.

'Did I love God, this post would not be hard. Do I not, then, love Him? Am I a hypocrite?'

He looked down at his little son; the child, suddenly tired, had fallen asleep on the crushed beds of mint and parsley; an unspeakable tenderness touched Mr. Mompesson; he stooped and gathered the warm, drowsy face, the soft, dimpled and relaxed limbs to his bosom. Here was flattering, ready love; here was affection easy to understand.

The boy awoke and cried out after his boats; but one was sunk and the other gone far down the stream.

"Will you hear the voice, George?" asked Mr. Mompesson: making a trumpet of his hands he called: "Love God," and the rocks gave back the echo—"'Love God.'"

THE young clergyman's mind was distracted with petty worries that he despised and yet that he could by no means overcome. These clangours of worldly matters overlay his deeper preoccupation with his own soul and his private honour.

He considered himself the guardian of his wife's young sister, Elizabeth, and he was not satisfied that she was making a good match with young John Corbyn; Mr. Mompesson was not pleased with the way his own wife delighted in the worldly aspect of this marriage, nor even with her attitude towards her new life. She had been in Eyam since April and more and more could he guess at the dissatisfaction behind her loyal but alarmed reserve.

Kate had lived as softly as himself at Rufford Park and Thornhill, the friend of Lady Savile, admired, flattered—and now this—a country parson's wife in this wild place. It was no wonder Kate had welcomed with childish pleasure the excitement of her sister's wedding and had made far too much of the money and position of the Corbyns.

'I must speak to Kate,' went constantly through Mr. Mompesson's mind, always followed by, 'but what can I say?'

Then there was the problem of his flock, strange unruly people, secretive, hard to understand, alien to him in everything. Some of the miners in particular were almost savages in the estimation of the cultured scholar. There was one, Sythe Torre, who seemed beyond all discipline and who led his fellows in many disgraceful and indecent pranks; he mocked, almost openly, at the new pastor, though he seemed abashed before his fine wife. And Torre was but one of the odd and difficult characters now in the spiritual charge of Mr. Mompesson; there was Mother Sydall, whom all believed to be a witch, and the herb doctor and the astrologer at The Brass Head in Bakewell—'God help me,' thought Mr. Mompesson, 'but they are no better than pagans. And their rites and customs come from heathen times.'

In his abstraction he stumbled over a stone—this snatched him out of his reverie and at the same moment he heard his name and saw a tall figure coming towards him up the glen.

"Mr. Mompesson, while you were meditating, your little one was falling into the stream." And the speaker put forward the child who, with wet skirt and rosy face, clung to his hand.

The blood rushed into William Mompesson's cheeks; this man was one whom he disliked, and who was one of his griefs and troubles—Thomas Stanley, the dissenting minister who had been appointed to Eyam under the rule of Oliver Cromwell.

"I thank you," he said stiffly, "I was forgetful." He took his son to his side. "The boy was chasing his paper boat, but it has gone."

"Perhaps," replied the Puritan, "his father chased as trivial a toy—or were your deep musings on holy matters?"

"Sir, they were private. And your sour censures, whenever we meet, strain my patience."

"If your patience never has more to bear than my poor rebukes, you are fortunate," replied Mr. Stanley steadily; he fell into step beside the young Rector—who foresaw, with vexation, that he would be forced to listen to another tedious discourse from the man whom he so heartily disliked.

Thomas Stanley was about fifty years of age, healthy and robust, with a deep chest and the slightly bowed legs of a constant horseman; he had been a chaplain to the Parliamentary troops and ridden with them in many campaigns; he was the son of a saddler of Chesterfield and had nothing of what Mr. Mompesson looked for in a gentleman. His coarse, thick grey hair was close-cropped, his blunt, not ill-shaped, features were empurpled and thickened from continuous exposure to the weather; an ugly scar puckered one cheek; his hands were like those of a labourer, and his clumsy homespun black garments were worn and faded, while his stout leather boots were patched and roughly laced with hide thongs over his rudely knit stockings.

Mr. Mompesson could have endured these offences, but he could not tolerate this ignorant fellow's assumption of a sacred office, his defiance of the Church of England and his indifference to breeding and scholarship—and his persistent interference in the parish from which he had been ejected on St. Bartholomew's Day, five years before.

The new Rector was also galled by the fact that Thomas Stanley had been revered and obeyed in Eyam and that the respectability of his character was in notable contrast with that of Sherland Adams, the man whom he had replaced and who, after the Restoration, had replaced him. Mr. Mompesson was bitterly aware that the Nonconformist still visited several of his former parishioners and, for all he, the Rector, knew, held services on the hill-side on the moors.

As they reached the mouth of the glen where it widened into the heath, the road and the village, Mr. Mompesson saw Ann, the maidservant, coming towards them, her grey gown and white apron cool in the sunshine; the child was late and his mother had sent for him; 'careless Kate,' her husband thought tenderly, 'was never careless where the children were concerned.'

He bade the boy run ahead, and when he had seen the woman take charge of him he turned to the sternly disapproving figure at his side.

"Sir, this is not the first time that you have forced your company on me. Let us come to an issue, so that, hereafter, we may leave one another in peace."

"Those are peevish words," replied the Puritan, his deep, steady voice touched with scorn. "To what issue can we come?"

"I bid you look to your ways." Mr. Mompesson flicked at some thistles with his light cane. "Sir, your interference in this parish will not be tolerated. I am very well with Sir George Savile, who is Lord of the Manor, and with my Lord at Chatsworth, who is Lord-Lieutenant—"

"But art thou," interrupted Mr. Stanley, "very well with God?"

"That is between a man and his conscience," retorted Mr. Mompesson curtly.

"Examine well that conscience of thine," said Mr. Stanley. "For many years I held this post—not always abiding here, but going much among the rude and scattered peoples of the north. Tyranny expelled me and I was forced to watch that unworthy man, Sherland Adams, usurp my place—"

"Sir, these complaints are familiar to me," interrupted Mr. Mompesson impatiently.

The Puritan continued unheeding:

"He cared for nothing but his tithes—what he might wring from the mines, and exasperated all with his litigation. You are no better, Mr. Mompesson, with your fopperies and your fine lady wife and the junketing at the Rectory."

"I no longer heed these charges that you bring against me so continuously," replied Mr. Mompesson with warmth. "But since your railings are vexatious, you rude man, I must bid you begone from my parish, Eyam, Foolow, Eyam Woodland, Bretton, Hazelford, my boundaries, the brooks and the river that you know so well."

"You bid me!" smiled the Puritan. "What are you or your patrons, or your boundaries, to me? I perform the will of God."

And he would not be silenced, but ran over his charges against the new Rector, his worldly elegance, the refinements of his household, the Papist ornaments he had introduced into the church, the frivolity of his wife and sister-in-law, who thought nothing of the poor, but who kept themselves for such gentle families as there might be in this Hundred of the High Peak, such as the Corbyns and the Lysons—and what better than neglect and worldliness could be expected from one who had been a courtier to a great lord and who bowed before such a notable malignant as the Earl at Chatsworth? Courtesy at first kept Mr. Mompesson in his place, then an ironic amusement that such bold speech should come from one so. forlorn. For the dissenter was penniless and proscribed; Mr. Mompesson did not know how he contrived to live, though he shrewdly suspected that some of his former parishioners subscribed to support Stanley; and the Rector remembered, with some shame, that the fine stipend that he enjoyed had never been drawn by the dissenter. During the suspension of the manorial rights, the tithe on the product of the lead mines had been abandoned and Stanley had received, for labours that none doubted had been zealous and arduous, a mere pittance. But Mr. Mompesson put that out of his mind and said sternly:

"I respect you for an honest man and I advise you for your own good. You have no business here. I know that you go still from house to house, helping the ignorant people with their business and their letter-writing, and under this colour praying with them."

"I have not denied it."

The Rector struck again at the thistles. "It is against the law. I think, too, that you dare to hold meetings—up in the hills or moors. It is known that last year you would not pay the steeple rate. Nor would you contribute to the Easter offering."

Mr. Stanley replied quietly: "For the first, one shilling and fourpence was demanded, and for the second, five pence. And they took my horse, whose value was over five pounds."

"For your field preachings, I might set the constable on you, yea, have the soldiers from Derby. You mind how those people called Quakers were dispersed last year?"

"Yea, and dragged away by the legs, with their heads on the ground," replied Mr. Stanley, "and taken before a Justice of the Peace, who sent them mittimus to Derby Gaol. There they were kept in a cell where they could not stand upright and their keeper struck them in the face when they prayed to God."

"Such is the law against dissenters," said Mr. Mompesson firmly, "and I have been long-suffering." He turned towards the village, the warm wind lifting the auburn curls from his shoulders, a flush on the handsome face that provoked the Puritan's contempt. "But you, sir, must leave my flock alone. Mr. Sherland Adams was lamentably indifferent to spiritual matters. But I stand for the Church of England."

Mr. Stanley dropped into his easy stride beside the young man and answered: "How deeply art thou mistaken! Both in thy menaces to me and thy confidence in thyself! I shall abate nothing of my ways because of thee. It maybe that thou shalt abate thine because of me. It maybe that God will speak to thee in this place, which is to thee so wild and savage. And then thou wilt leave thy easy living, thy music, ribbons, idols, dancings, perfumes and curlings."

Mr. Mompesson looked curiously over his shoulder at the speaker, "I am not the idler you think me, Mr. Stanley," he smiled, his vexation gone, for he felt that beneath a rude exterior this man was modest, humble and brave. "I have studied, worked and pondered."

"I make nothing of thy learning, Mr. Mompesson, Master of Arts, as thou mayest be. Nor of thy ponderings. Take heed to these people in thy charge. Their souls will not be saved from the Pit by shows of images or lute playings or honey-sweet talk. Look to these wakes, sir, they begin shortly. See if you can control the wild, the wicked and the blasphemous in these days of festival and licence."

"Could you, when you were Pastor here?" demanded Mr. Mompesson.

"Yes," answered the Puritan simply. "But under Mr. Sherland Adams bad customs prevailed again; last year it was like a heathen rioting. And the Rector himself sat in an ale-house, The Miners' Arms, and drank and jested."

At this talk of the coming merrymaking, known in Eyam as St. Helen's Wake, Mr. Mompesson's spirits sank; he did indeed feel unequal to the prospect offered by the outburst of profanity and licence, idleness and buffoonery, that he had been assured characterized this festival of harvest, which remained pagan in almost all its aspects; especially did he dislike this thought, because St. Helen's Wake coincided with Bessie's marriage, another matter before which he felt inadequate.

"You are afraid," said Mr. Stanley, who had been observing him closely. "This charge is too heavy for you, Mr. Mompesson. For you have a conscience."

The village on its pleasant valley was now before them, and the Puritan, giving the other no time to reply, abruptly turned and retraced his steps along the paths, purple with the flush of red heather, that wound towards the dell.

Mr. Mompesson looked back after his sturdy figure and almost envied him, for Thomas Stanley knew the peace of a single mind and a steadfast heart. Almost, not quite, for William Mompesson would not have cared to live, as the dissenter probably lived, in holes in the rocks, in barns, on charity. William Mompesson would not have cared to go roughly clad and to exist without all those pleasures that gilded life for him, nor without Kate and his two children.

THE village of Eyam, which William Mompesson slowly approached on the late afternoon of this warm July day, lay in the south-east part of the Parish of that name and six miles from Bakewell. Two little townships, Foolow and Eyam Woodland, and two hamlets, Bretton and Hazelford, completed the Parish; the whole was confined in the Honour of Peverel of the Peak, and in the Diocese of Lichfield and Coventry.

The Rector faced a wide street, nearly a mile in length, as he approached the Rectory from the dale, built, who knew how long ago, on a tableland of limestone, sandstone and shale, which curved through the valley surrounded by the lofty hills of the Peak. The street, of uncommon width, was guarded at the eastern or Town end by the gate known as the lych-gate; this the villagers took it in turn to watch by at night, more out of regard for ancient custom than through fear of any possible danger. Beyond this gate, which stood open in the daytime, the street widened to the spacious green and Cross, then narrowed again to the Townhead, or western part.

The village took a serpentine course and there branched from this long street, twisted lanes, the Causey or Causeway, the Dale and the Water Lane. In the centre rose the church, almost completely hidden at this season of the year by the foliage of some magnificent linden trees; above these boughs, amber-coloured from the sunlight, only the squat grey tower with the four finials was visible.

The dwellings that lined the street were simple, one-storeyed cottages, some tiled, some thatched, some flush on the wide road, others with stone-walled gardens round them; some detached, in a square of ground, others in a row; such as had space possessed neat ranks of straw-covered beehives, and many had a little pasturage in the rear where a cow was kept.

A capacious inn with a wide entrance for carriages stood on the green. The efforts of a journeyman painter had depicted a glossy and gigantic Bull's Head on the sign. Further on there were two ale-houses of modest pretensions, The Foresters' Arms and The Miners' Arms, while another inn, The Townhead, and two other alehouses, The Rose and Crown and The Royal Oak, furnished the western part of the village. To the open disgust of Mr. Stanley and the secret dismay of Mr. Mompesson, this village of less than three hundred houses and less than five hundred inhabitants had six ale-houses.

Eyam was almost deserted as the Rector walked slowly along the main street, a few old folk and children, with sleeping dogs and yawning cats, sat at their doors, spinning, gossiping or dozing in the sun. The men divided their time between the lead mines situated in the rocks of the Peak and agriculture; most families were self-supporting with their cows, poultry, bees and hay. The mines were very old and paid better every year; a man did not need to work long hours there in order to earn a good income for a labourer or peasant. These mines, besides supporting the Church, paid a tithe to the Lord of the Manor, and the expenses of their own administration by a Barmaster, Steward and yearly court called the Barmoot. The mines themselves belonged to the Parish of Eyam by virtue of a Charter supposed to have been given by King John, which no one, however, had seen.

A new mine, known as the Edgeside vein, had lately been discovered and found to be very rich in ore, and this promised fortune showed in the lively preparations being made this year for the St. Helen's Wake. Mr. Mompesson knew that this meant added riches for himself—some said that his stipend would be raised to something near a thousand pounds a year presently. Kate and Bessie had been very pleased at this talk, but he had felt uneasy. And he felt uneasy now again when he recalled the grim rebukes of Thomas Stanley.

The villagers returned his graceful salutation kindly; if he had not much impressed them as a man of God like Mr. Stanley, they bore with him because he was a handsome, amiable young gentleman, who always spoke to them courteously and who did not much interfere with them.

The Rectory stood back from the road, close to the church and in considerable grounds. Mr. Sherland Adams had let it fall into disrepair, and Mr. Stanley had turned it into a poor-house save for one room in which he lived, so Kate had burst into tears when she had first seen her new dwelling. But Sir George Savile had allowed repairs to be made and sent furniture from Rufford Park, while Kate and her sister had travelled as far as York to buy hangings and mirrors.

Then the Rector had sent to Nottingham for such chattels of his own as his parents had left him and had been stored with a relative, and Kate's uncle, Mr. Beilby, had sent some gifts, so that now, four months after their arrival in Eyam, the Mompessons were set out in a state that rivalled that of the few gentle families in the district, the Corbyns, who were rebuilding the old Manor House, the Lysons of the Hall, near Middleton Dale, and a few others of the better sort, who resided near Eyam. Yet Mr. Mompesson was conscious of a return of that distaste of his new surroundings which he had not yet been able to overcome. Eyam was truly in the wilderness and the Rectory a mean place compared to Rufford Park; he was ashamed to find that he was calculating how soon the profits from the new lead mine might come, and if they would justify him in adding a wing to the house that had been so much too large and fine for Thomas Stanley.

THE two women were in the large panelled room that looked on the rose garden and, through the gate in that, to the orchard where the beehives stood beneath the fruit trees; the sunshine was full on the group in front of the handsome mirror with the tortoise-shell frame and the bands of dark blue glass that had been a present from Lady Halifax.

Catherine Mompesson was seated on a low stool and Elizabeth Carr on a cushion by her side; the young matron wore a gown of pale grey cloth with a falling lace collar and laid seams of green braid, she had sea-green ribbons in her hair, at her bosom and wrists; she was a slight, gay creature, with fine, bright brown ringlets and large hazel eyes, her features childishly small and pretty, her complexion too brilliant to need the velvet patch she had stuck by her delicate chin.

Five years of marriage and the birth of two children had not sobered the Rector's wife into any gravity or heaviness of deportment; at twenty-four years of age, she seemed no older or more serious than the younger sister who sat beside her, wearing a gold coloured gown of a bird's-eye pattern and holding up to the dazzling light a sample of white satin.

Bessie Carr was darker than Kate, an abundance of glossy, chestnut curls hung gracefully from her small head, and charm was given her insignificant features by her animation, sparkle and radiancy of her clear eyes and pure complexion. In the cushioned window seat slept the other Elizabeth, the Rector's little daughter, curled up in her muslins and silks, with the curtains drawn forward to shield her from the sun's bright rays.

William Mompesson paused at the door and smiled tenderly at this peaceful scene. But he recalled the stinging rebukes of the dissenter and inwardly admitted that there was truth in them. The room was handsomely furnished; there were inlaid cabinets, a sideboard with silver flagons, portraits in gilt frames, damask hangings, chairs with velvet cushions, cups and platters, and the two young women in their expensive garments, with patterns of tinsels, satins, buckrams, braids and fringes scattered over their knees and on the floor beside them.

"We are choosing the wedding clothes," smiled Catherine. "And yours, too, my dear—even if you must wear gown and bands, I'll see that they are of the finest quality." He had no heart for a rebuke, though he thought they made too much of this wedding and spent a good deal of time and thought on the preparations for it, rejoicing, besides, with too open a guileless pleasure, on the worldly advantages of the match.

"Where do the patterns come from?" he asked, trying to show a courteous interest in their dainty task.

"From Derby," said Kate. "Mr. Vickers got them for us; they came by the carrier this morning. Mr. Vickers is a clever tailor, for this outlandish place."

"But is not your finery complete?" asked the Rector pleasantly; he took the place beside his tiny daughter in the window seat and looked with a deep affection at the sleeping infant.

"Not complete," cried Elizabeth Carr, who was always ready to chatter. "Most of the dresses are made, but there are household furnishings and ornaments to attend to—you know that John says I am to have new goods in a new house..."

"And there, Mompesson," put in Kate quickly, "is a chance for you to read us a homily, on a new heart too."

"I cannot preach to you, Kate." Mr. Mompesson smiled a little sadly. "Save when you go to church and then, I think, you do not listen."

"Nay, but I do, and think what a fine figure you make in the pulpit..."

"Do not laugh, Kate, for I am like to make but a poor figure in Eyam. These people give no heed to me. To them I am not only a stranger, but almost a foreigner."

The women spoke together.

"They are so barbarous, so wild..."

Mr. Mompesson hushed this pretty clamour. "They are given into my charge. And when this wedding is over, Kate, you must go among them more, and make friends with them, and help them."

"Oh!" Mrs. Mompesson gave her lord a mischievous glance. "I must, indeed! Why, I hardly understand what they say—and they stare at me as if I was a mummer at a fair..."

"And I'm sure," added Bessie eagerly, "I don't know how you expect Kate to remain in this lonely place..."

"Will not you live here?" asked the Rector. "What of the fine new Manor House, Bess?"

"John has promised to take me to Derby and to Buxton. John will not be tied here, as you will be. We shall have a coach, we might even go to London. And we'll carry Kate with us, too, say what you will, dear sir."

"Truly," put in Mrs. Mompesson eagerly. "I hope we do not stay here long, even now in the summer I feel shut in by these mountains—so far away from the rest of the world; and what must it be, for desolation, in the winter..."

"We are not in Muscovy or Cathay," said the Rector gently, "but a few miles and you are in a fine town, Buxton or Sheffield..."

"He protests against himself, dear," smiled Bessie to her sister. "He feels exiled here, too; how different his spirits are from what they were at Rufford Park! Is he not often apart in a melancholy?"

"It is true," agreed Kate tenderly. "Where were you to-day? You had George abroad so long I sent Ann after you, and she found you where I knew you would be, in that solitary glen."

The Rector was impressed by this picture that the two young women, with simple sincerity, gave him of himself. It was true that he had fallen into a pensive, inactive habit, had become slothful and languid, since he had been confronted with the difficulties of his new post. "I must amend my own ways," he admitted, "the task I have weighs on me. I feel that it is one for a better man. One older and of more power. I should do more with these people, who have become very irreligious under Sherland Adams's idle ministry..." He did not add the thought that was in his mind—that there were many in his parish who were God-fearing, but that these were secretly followers of the Rev. Thomas Stanley and heeded him, William Mompesson, not at all.

"Let it go," said Kate easily. "You do your duty and the people are content. I wonder only that Sir George sent you here. Pray, before the winter comes, beg him to send us to another living or take us again to Rufford Park."

"Nay, my Kate, we have been cream fed, cushioned on silk, too long."

The young women laughed and their delicate mockery roused him; he saw, with a sudden painful clarity, the whole pleasant scene as an enchanter's delusion. These two lovely girls, the beautiful infant, the handsome room, the prospect beyond, honey, roses, fruit, all the symbols of ease, of luxury, of rich idleness—what manner of man, of priest was he to be content with this?

He rose and approached the laughing Bessie and the smiling Kate and said to them earnestly and with deep tenderness:

"I am at fault. I should set you a better example. I conjure you, both of you, to give no cause for mockery. I am the Rector, Kate, and you are the Rector's wife. What was suitable for Rufford Park is not suitable here," he glanced at the boxes of patterns, the cuttings of braid and tinsel. "I will have this wedding plain, Bessie. You have no other guardian save your uncle, Mr. Beilby, and he is of my mind. All must be sober, even plain. Besides that, gauds are not fitting our station, we cannot afford them."

"John is well enough for money," pouted Bessie, fingering a length of azure ribbon.

"His father's settlements are not very generous, dear. And whatever he has, your provision does not come from him until you are his wife. I'll have no debts, Bessie. No useless expense. It is my charge to see your little fortune wisely bestowed."

"How serious you are, Mompesson!" protested Kate. "Is this a time for homilies?"

"Alas, if I speak lightly, you give no heed to what I say. I have observed much hustle and coming and going here..."

Kate flushed; she had always been so affectionately dealt with by her husband that the least reproof from him wounded her keenly; lately she had, with the sensitiveness of a young, delicately nurtured woman, resented his absent-mindedness, his fits of melancholy, his long withdrawals to the solitudes of the mountains and the glens, as much as she had resented the uncouthness and isolation of Eyam. "I hope I know a woman's business best," she said warmly. "Bess needs much stuff before she can set up housekeeping. I make what economies I can. But my sister cannot go like a beggar... "

"She need not go, either, like a great gentlewoman," replied Mr. Mompesson. "Indeed, Kate, I want no pomp that is likely to set us above our rank and to rouse malice and unkindness among those to whom we should be an example of humility..."

Kate bit her lip, silenced by this show of authority, but hurt and rebellious; Bessie hung her head and the Rector left the room conscious of having ill played his part, of an uneasiness and uncertainty in himself that ill fitted him to play the mentor to anyone.

He had more serious grounds for concern than the charming, if exasperating frivolity of the two young women; his man, Jonathan Mortin, had met him on his return and told him that, during his absence, Sythe Torre had come to the Rectory, speaking of an urgent matter on which he wished to see the Rector. Urgent it must be, Mr. Mompesson reflected, for the miner to have left his work so early, and he shrank from any contact with this uncouth, almost savage fellow, who had so bad a character even among his coarse fellows. 'I suppose he comes a-begging,' and he told the servant that he would see Torre when he returned, as he had promised to return that evening. 'It is my plain duty,' he told himself; he had another, even more disagreeable. He must go to the Manor House and speak to John Corbyn on a matter that had come to his knowledge—a thing, perhaps, of no importance, and yet perhaps a thing of great moment.

He did not like the Corbyns, a proud, hard family, he thought, which was not diffident about expressing a sense of condescension in marrying their heir to the Rector's portionless sister-in-law. The haughty parents, Mr. Mompesson knew, had been heard to say that the match would never have been made had not John Corbyn met Elizabeth at Rufford Park, where he had gone to pay his devoirs to the new Lord of the Manor. Only the kindness of the Saviles for the bride-to-be had made her acceptable to the Corbyns, and the appointment of William Mompesson to Eyam, which might have seemed so apposite, had rather irritated these local gentlefolk, who would rather have had Sir George's chaplain than the Rector of Eyam in the family.

Of these feelings Mr. Mompesson was well aware, and they did not help to increase his liking for his new position. Nor did he feel altogether easy at trusting the happiness of little Bessie, which was so closely woven with the happiness of his Kate, to John Corbyn, for whom he had little respect. But outwardly it was a fine match and Bessie was deeply in love, so there was nothing for the Rector to do but to make the best of it, and he set out through the summer gold towards the Manor House, which stood a little beyond the village.

The sun was declining and the miners were returning to work in their little fields and gardens before the evening meal; self-absorbed as he was, William Mompesson took no heed of these rude parishioners beyond a casual touch of his beaver; he was thinking, with compassionate love, of the two young women, whose pleasure he had perhaps spoiled by his rebukes. How pleased they would have been had they known that he had met the Earl, how eager to go to Chatsworth, that was even more splendid than Rufford Park.

This reflection brought sharply to his mind what my Lord had said: 'If they do not know, do not tell them.'

For a second Mr. Mompesson could not recall to what this referred; the matter was vague and, compared to the affairs that he had on his mind, unimportant. But it was as well for him to recall the Lord Lieutenant's warning, which was this—the plague that had been so frightful a scourge in the capital last year that the court had removed to Oxford had, after subsiding during the winter, returned, in some slight degree, to London.

Well, he smiled to himself, they were as safe here as if they had been in Cathay, shut a hundred and fifty miles away in this mountain fastness; but if poor, sweet Bess really tried to induce her groom to take her to London, why, then, he must tell her of the Earl's warning; but his smile deepened as he reflected how over-cautious my Lord was in even mentioning this recurrence of the plague in London—why, if it had been in Derby even, there would have been no fear, so cut off from the rest of the world was this little community in the Peak.

And it was with a pang near to regret that Mr. Mompesson recalled that neither he nor his wife had as much as an acquaintance in the capital, for he, when he had visited London with Sir George, had much admired the splendour and eager energy of the life that his patron and his friends led in Whitehall.

The Manor House had long been leased by the Corbyn family, who farmed a large district and owned a lead mine in another part of the Peak; wealthy marriages had increased their importance considerably, and Catherine Mompesson was justified, from a worldly point of view, in rejoicing that her sister had made so good a match as young John Corbyn, only child of Ambrose Corbyn and heir to all his property.

The Rector paused at the gate and looked at what was to be Bessie's house; the stone-masons were working on the new wing and the portion that was being rebuilt was covered with scaffolding poles. It would be some months before the work was completed and meanwhile the young couple were supposed to lodge in the Dower House, a small antique dwelling lower down the valley, so incommodious that it afforded Bessie a fair excuse to travel.

Mr. Mompesson passed through the gardens, now disturbed by the builders, and stood before the old Manor House south door; above this was a circular stone, on which was the crest of the Corbyns cut deeply. A raven on a wreath, perching under a vine, with the date 1560 cut beneath. As the Rector's hand went out to the iron bell-pull, he saw young John Corbyn coming towards him through the orchard at the side of the house, and he turned aside to meet him, coming up with him in the field known as the Manor Yard.

The two young men exchanged greetings and spoke of the wake, for which the Corbyns made extensive preparations. They feasted and entertained their tenants and servants and this year this rejoicing was to be on a large scale, for on the last day of the wake John Corbyn was to marry Bessie Carr. This family had a peculiar connection with the festival, for they held their lease on the condition that they should keep a lamp perpetually burning before the altar of the patroness of the wakes, St. Helen, in the Parish Church.

John Corbyn seemed surprised at this visit from the Rector and, when he had talked rather boastfully about the handsome show his family would make, he fell into a silence that was slightly awkward and left the conversation to the other man.

Bessie's betrothed was a fine young man, tall and well shaped, with thick yellow hair cut square on his forehead, light grey eyes that easily assumed a sullen expression, and good features, slightly thick and coarse. His country clothes were expensive and not free from a hint of foppery in the bunches of ribbons on his shoulders and at his wrist.

"I have to speak to you on a vexatious matter."

John Corbyn at once became hostile; he had never made any disguise of his ill-concealed dislike to the Rector; he protested—what tiresome affair would be brought up now?

"Your conduct in Bakewell," said Mr. Mompesson kindly. "Upon a hint I determined to make inquiries and found that your behaviour has been such as I must take notice of..."

"You put an affront on me!" replied the young man, his sanguine face flushed darkly.

"I am Bessie's guardian," said the Rector, who had expected this anger, "so pray check your wrath and way of thinking. You are not a month off your wedding and you sit in ale houses with mummer's wenches."

"Who told you?" demanded John Corbyn, pausing in his walk and sticking his hands on his hips.

"Those I did not heed. But I rode myself to Bakewell and saw you, three nights ago, though you did not see me, coming in your cups out of The Talbot, with a poor dancing woman on your arm."

"I prepared some actors for the shows up here"; the young man made his excuses with ill will. "Do you expect me to be ever saying my prayers at home?"

"Bessie loves you," said Mr. Mompesson. "If she knew this, all her world would fall into confusion."

"Who is to tell her? Who is to make mischief over a little harmless merriment?"

"Not I, John, not I. Harmless? I do believe it has no great harm, but ill manners breed mischief fast enough."

"This is a time of licence," interrupted the young man shortly. "I am no profane fellow or a scoffer. But I tell you, sir, neither will I live as that snivelling Round-head would have us. I mean Thomas Stanley. This place is quiet for one of my parts. I mean to travel, to get some post with the Lord Lieutenant."

"Jack, I have nothing against your ambitions; the Peak is quiet, too, for Bessie—nor would I be straitlaced. But these levities and debaucheries..."

"When Bessie has me fast," put in John Corbyn, with a sudden smile, "let her hold me if she can—do you doubt that she can? I love her as she loves me. But no more of this preaching, sir. I had my belly full from the dissenter. I marvel that you allow him to lurk about the place. I cannot stir abroad but he is at my bridle, telling me of my foul life. As if a cup of ale and a wench on the knee were damnation."

Mr. Mompesson was offended, for he did not like to be compared to the ranting Puritan whom he disliked, nor to think that Thomas Stanley had taken on himself to rebuke one whose morals and behaviour were in the Rector's charge. John Corbyn saw his vexation and took advantage of it to say:

"Why do you not set the constable on him? Nay, have the soldiers in from Derby, as they did for the Quakers..."

"Some like the man and he does good, too," replied Mr. Mompesson. "He shall not be apprehended on my charge, but we digress..."

"From the sermon that you would read me?" John Corbyn spoke with forced frankness. "Sir, I know it all and you must look upon me as a sensible, religious man, until you have proof that I am a rogue."

"I did not say rogue..."

"No, for you gave up your sword when you put on the gown and bands," said the young man with a wry smile, "therefore you go gently and I must respect you for a clergyman. But were we of a quality as we are of an age, I doubt not that we should come to high words." He turned aside and stared down into the fish-pond, where the big mullet came, gaping with blue-gey mouths, to the stone rim.

'He dislikes me,' thought Mr. Mompesson, 'and it is my fault. I have not handled this carefully.' He was turning away, feeling self-rebuked and grieved, because there would never be, he thought, any real quarrel between Bessie's lord and himself, when the young man called after him in an unpleasant mocking fashion.

"Ask Bessie herself what mischief she has on hand. Is she in debt for finery, does she gamble? She had five pounds from me, and won it from me with kisses. Is that your training, sir?"

Mr. Mompesson was amazed; a sharp denial he checked with difficulty; he saw in the steady, angry grey eyes of John Corbyn that he spoke the truth—he remembered the boxes of patterns, the glistening fopperies that had of late been strewing the Rectory furniture. "Your money shall be returned to you, sir," he said quickly.

"Do you think I would take it?"

"Since you have told me you gave it," replied Mr. Mompesson, with rising colour, "I am at liberty to believe that you would accept its return."

"You had not heard unless you had angered me. I defy you to tell Bessie...?"

"That you betrayed her?" interrupted the Rector bitterly. "You need not fear, sir. I value her peace of mind that rests on my faith in you." He checked himself, this would soon be a quarrel, a scandal, perhaps the ruin of poor Bessie's marriage; he turned away miserably through the thickening gold of the late afternoon and heard John Corbyn laugh behind him as he went.

THE young Rector felt weary with that nervous, restless fatigue which comes from a dissatisfied mind and ill-adjusted labours; he had been quiet during supper and the young women had cheerfully rallied him on his humour. Now he sat alone in his little library or study, awaiting with distaste the arrival of the uncouth miner, Sythe Torre.

'I am in the wrong place,' he thought gloomily. 'I am fitted for none of these things—neither to manage my own wife and her sister nor to control John Corbyn nor to overcome Thomas Stanley nor to understand and help my savage parishioners—what use can I be to this man Torre? A bold ruffian, what does he want of me? What am I? A fine gentleman? A recluse? Why am I thus cloudy and languishing?'

He looked round the room still unfamiliar to him and mean, compared to the painted chamber he had enjoyed for nearly five years at Rufford Park, though Kate's care had done much to make it handsome. A tapestry that was the gift of Sir George Savile hung against the long wall opposite the window; worked in indigo blue and deep green worsted, it represented Moses raising the Brazen Serpent. In front of this was a fine Chinese cabinet on a gilt stand, and lining the short walls, save for the door, cases of books; Mr. Mompesson had a valuable collection of classical authors and some modern treatises; he himself had beeswaxed the shining tooled calf and sepia-inscribed vellum covers, and it gave him pleasure to see the purple, green, and scarlet silk ties hanging below the spines.

Before the window, curtained in a saffron yellow damask, stood the writing-table where the Rector sat, and in the corner was a brass bracket clock, while either side of the window was a small portrait by a Dutch painter: one of Mr. Mompesson's father, painted on his visit to the Brownist Colony at Leyden, the other of his wife, a pale young woman holding an African pink.

Mr. Mompesson's desk was handsomely finished, the standish, hour-glass, and candlesticks were in silver, the Bible and Prayer Book were lavishly bound and mounted with the same gleaming metal.

The reading-lamp, of sparkling crystal and silver-gilt, set close to his hand, was neatly trimmed; quills, packets of paper, tapers, sticks of wax and binding cords for packages, all lay in readiness for the Rector's sermons or his correspondence.

His deep chair with arms was deeply cushioned with saffron velvet heavily fringed, and on the cloth that hung over the back were worked in Kate's fine stitching the Mompesson arms, argent, a lion rampant, sable, charged on the shoulder with a mullet of the field: with the curious crest of a bouget, or Crusader's desert water-carrier, with a string assure, tasselled of the first. Above, in uneven letters was the motto that Kate had found difficult to embroider: 'Mon juge est Dieu seulement.'

Mr. Mompesson had taken considerable pains to make the room that he had found bare and forbidding into some likeness of the luxurious chamber that he had occupied at Rufford Park. But though he had succeeded in impressing his parishioners—far more than he wished—with his gentility and his wealth, the apartment remained, to him, mean and even distasteful.

William Mompesson tried to compose his thoughts; he was deeply vexed with himself that they should be so agitated. He had no reason to be disturbed or forlorn; he reminded himself of his bountiful blessings—his youth, his health, his easy life, his wife, and children, his opportunities for usefulness, the many pleasures he had, from his books, Seneca, Plautus, Lucian, to his beehives and his apple trees.

But content cannot be hastily summoned, nor serenity be put on by making a resolution to be serene.

The young Rector was deeply troubled; he could neither adjust his affairs with man nor, and this was the deeper grief, with God. He had from his early youth accepted Christianity as taught by the Church of England, he was absolutely loyal to the religious teachings that he had imbibed with such enthusiasm.

William Mompesson, sensitive and conscientious, was not the man to enter the ministry for a piece of bread or to accept with grateful facility the mere symbols of a religion. As a Christian priest he knew that he must accept the tremendous fact of God, and God's holy Angels, and the Devil and his loathsome demons, and allow these to guide both his spiritual and his material life.

He had the temperament of a mystic, but worldly matters had impinged upon his secret communings, which had in his youth approached ecstasy, with his Maker. Indolence, worldly ease, even doubt, had crept in like the little foxes that eat the vine. The elegant conversation of Sir George Savile, his wide intelligence, and gently mocking wisdom that were not, for all his protestations, wholly subservient to Christian doctrines, had done something to disturb his chaplain's faith.

Then had come the sharp, poignant, bitter-sweet love of the flesh for Catherine and the joys of his union with her, the birth of his children, and his own studies in the classics, which had engaged him so deeply. He had felt blotted and corrupted by these sensual pleasures.

All these things seemed to put clouds between him and God. The priest began to fear his own mind and his own power of reasoning; he dreaded to feel that through the intellect the Devil tempted men of his temperament. He feared his own easiness and indolence, which at times approached sloth; he winced before his own love and liking for the activities of his life. He knew that he should look upon all these as vain joy, vain grief, vain care, and have all his soul fixed on eternity.

But this attitude of mind and soul was not easy to attain. William Mompesson feared, too, his own inner arrogance, which he could by no means subdue and which made him sense himself to be the superior of these rude, gross people, over whom he had been set, and that he was put apart from them. Indeed, when, as in this moment of solitude in his study, he looked into his own heart, he saw mirrored there nothing but fears, uncertainties, and doubts.

There were specious arguments he might have employed, such as: 'Go thy way, thou hast done no wrong': 'Live pleasantly, dream deeply, and let all else slide': or 'Who has complained about thee? Thou art fortunate, a worthy man in a safe place.'

Such fallacious comforts could not soothe him, nor could he derive contentment from dwelling on his felicity. He knew that his present discomforts in Eyam were but temporary, and with the aid of Sir George Savile and the Earl of Devonshire he might easily, say in a year or two, be sent to some other cure. He might contrive, even, to go to London and become chaplain again in a great house, where the lucky world's gorgeous mask and glittering store would be spread before him, his Kate, and his children.

There he might have, for the asking or the intriguing, all the latest modes of pride and lust.

Yet this hope did not allure him, though ambition stirred in him often enough. It was indeed as distasteful as the rude solitude of his mountain fastness. Every prospect that rose before him seemed equally abhorrent. He would not be here among this coarse peasantry whom he did not understand or like, he would not be amidst the temptations of the glitter of the great cities, he wished to resist the snare that came from the gilded idleness in a vain, glorious lord's mansion.

What, then, did he want?—he would neither be recluse nor man of the world nor nobleman's servant nor plodding citizen nor industrious scholar. Something of all these qualities there was in his nature.

But above them all was this desire to be at one with his God.

He laid his hands out on the desk and looked at them, ashamed of their delicate make. Womanish hands they appeared in the yellow light of the carefully trimmed lamp, too fine for the uses of anything but indolence.

"Lord," he said out loud, "what is Thy will with me?"

But these were words only, and he felt that they did not go upwards to the all-triumphant splendour, for he was vexed because of little troubles—the five pounds that Bessie had borrowed from John Corbyn, Kate's absorption in the approaching wedding festivities, the coming wake that would provoke a licence he would not be able to restrain.

Then the problem of Thomas Stanley, a man whom he respected yet did not like, whom he was protecting, half-willingly, against the Law, whom perhaps he should deliver to the Law, for the man was a heretic, an outcast from and a derider of the Church.

Mr. Mompesson's troubled reverie approached anguish, and prayer broke from his lips that God would relieve the weight about his heart. And then, when the door opened slowly, he was startled at his own seriousness and wondered why this discord had brought him, for no good reason, to so low a state.

It was Jonathan Mortin who entered, his confidential body servant, who had been with him at Rufford Park, and who had very willingly come to Eyam with his master, since that was near his native place, Bakewell.

Jonathan Mortin was a well-trained, quiet man, who had effaced his own personality, as a servant in a great gentleman's house. Mr. Mompesson liked him without being familiar with him, and trusted him without having ever probed into his character.

Ann Trickett, who was Kate's woman, and helped her with the children, had also come from Rufford Park, Buxton was her birthplace, but there were Tricketts in Eyam. It was not the least of William Mompesson's comforts that these two staid and faithful servants had followed him into the strange place and freed him from the necessity of employing the villagers, who to him were like foreigners, for anything save the roughest work.

"It is Sythe Torre, sir," said Mortin; "he declares that you promised to see him."

"It is true," said the Rector, collecting his idle shames swiftly. "Bid him come up."

When the servant had withdrawn, the young man clenched his hands on the desk, and his eyes and brows narrowed into a frown of self-contempt.

'Why do I dread to see this fellow? Why am I so unequal to this that is but a small part of my task?' He turned in his chair so that he faced the door, and putting out that fair right hand, the delicacy of which he had himself despised, on the silver-bound Bible, composed himself for the interview.

He had not the least inkling of what this man would want of him, but he experienced an unpleasant sensation when the miner slowly and sullenly entered the library, for he remembered the bad character the man had, and he was oppressed by his physical stature.

Sythe Torre was accounted in Eyam a giant; he was well over six feet and of enormous proportions. His massive sloping shoulders, short thick neck, small head with the flat back, were characteristics of strength that Mr. Mompesson had seen in antique statues. The Derbyshire miner, indeed, much resembled a bust in the possession of Sir George Savile, which purported to represent the Emperor Maximus. Here were the same blunt, brutal features, the compact dark curls, the heavy jaw outlined by a crisp beard, the deep-set eyes, and the retreating forehead.

The miner was in the prime of life, Mr. Mompesson judged him to have no more than thirty years? His strength and industry earned him good money in the lead mines, but he was not very frequently occupied there, he preferred the upper air. Besides farming his own small piece of land on the outskirts of the village, he took long holidays from his toil when he travelled about the Peak district, wrestling, throwing the javelin, fighting with the quarter-staff, and exhibiting other feats of strength at local fairs.

The Rector had heard ugly stories of the giant, who was reported to be cruel, ruthless, and blasphemous, but his crude stone dwelling, largely built with his own hands, sheltered a silent wife and sickly son, to whom he was reported to be obstinately attached.

Without speaking and taking no notice of the Rector's suggestion to him that he sat, the giant stood, glancing with his small sly eyes around the room, noticing the tapestry, the furniture, the books, with childish curiosity.

He had made, Mr. Mompesson noted, some attempts to compose his dress for this interview. His coarse and soiled shirt was caught together with a ribbon at the neck, his grey-green coat had been brushed and a pair of clean white woollen stockings drawn up over his worn, patched breeches.

The Rector controlled his impatience and waited for this strange member of his strange flock to speak. He wondered if the fellow had come to ask for work, perhaps he was unemployed as a result of some quarrel at the mines—but when Sythe Torre spoke, he showed at once that he had come on spiritual matters.

Looking at the Rector and thrusting his thick finger into the coarse ribbon at his neck, he said:

"Would a murderer be damned, sir, save he make repentance?"

This was no problem to the Rector, who answered directly:

"Every sinner would be damned unless he made repentance, unless he believed."

"Ay," said Sythe Torre, with a deep sigh, "ay. That's what Mr. Thomas Stanley told me, and he's a holy man."

"Do you go to him?" asked Mr. Mompesson quietly. "Are you in his charge? Do you term yourself a dissenter?"

The giant shifted uneasily from foot to foot; he appeared awkward, bewildered, and yet desperately earnest about some vital matter, his dialect was thick and offensive to the ear of the gentleman who listened to him so gravely.

"I don't know these fine terms, sir," he said sullenly. "I come to you about a plain matter. Mr. Stanley's a man of God, too, isn't he? Well, I asked him. He said—damned and lost, burned for ever."

"No one can tell you otherwise," replied Mr. Mompesson sternly. "None but a madman would think it possible to sin and escape punishment. What is this talk of murder? How does it concern you, Sythe Torre?"

"That's not my business to be telling you, nor your business to ask, sir," replied the man, servile and yet hostile too. "I thought it was a point you could make clear to me."

"I have made it clear to you," replied the Rector. "I could enlighten you on other matters, would you come to church. I do not think I have seen you there since my ministry began. I hear you indulge a black self-will, that your lusts disorder into crime."

"I don't understand the church," replied Sythe Torre, looking on the ground. "I don't understand half the things you say. Mr. Stanley told me..."

"When you speak to me," replied Mr. Mompesson coolly, "you must leave Mr. Stanley out of your speech. He is a dissenting minister. If he preaches or tries to instruct any of you, it is against the law. He might be laid in Derby gaol for that."

"Ay, ay, so he said," replied the giant, unmoved. "But I wanted to come to the matter of the murder, sir. There was one man that murdered another, and it was not discovered. And he didn't repent. Is his soul damned?"

"To all Eternity," replied Mr. Mompesson. "Poor man! Have not these awful truths been impressed upon you yet?"

"Who's to tell me they be truths?" asked the huge fellow obstinately. "That's what you say and that's what Mr. Stanley said, and I went to The Brass Head in Bakewell..."

Mr. Mompesson interrupted sternly.

"You must not come here to talk such blasphemous nonsense! These astrologers and witches are but quacks and charlatans, telling lies and performing tricks for money. There is no shorter cut to Heaven than by repentance."

"Ay, ay," replied the giant unexpectedly, "but, sir," and his small eyes were earnest, "the magician told me, too, that there'd be a judgment for it, and maybe not only on the murder, but on the place where he lived. He said that God sent judgment like thunder and lightning and earthquake."

"There was Sodom and Gomorrah," replied Mr. Mompesson with a slight smile, "but these are deep matters to argue with you. If you know one who has a crime upon his conscience, bid him confess, give up his body to the law and his soul to the Church so that he may be saved from eternal damnation."

Sythe Torre stroked his small beard with his coarse hand and looked doubtfully on the ground.

"The murder might have been in a fight, and the one that killed the other might have had the right of it," he argued, "and it might have happened down the lead mines when no one was looking or prying."

"I will not hear these tales save you give them to me as a sincere confession. I suppose you speak of your own case, Sythe Torre?"

"Nay, nay," protested the giant quickly, "I talk of a friend."

"Be that as it may," said the Rector, rising, "I cannot hear these half-confessions nor pass judgment upon problematical cases. Learn, poor wretch, that sin must be punished in this world and in the next, and that the Lord will send judgment on those who offend Him."

"Til think on it," muttered the miner, shuffling uneasily towards the door, pulling again at the ribbon that bound his dirty shirt at the neck. "But there's many who'd rather risk damnation in the next world than be hanged in this. Who knows," he added, with a simplicity that robbed his words of offence, "if God really tells you and Mr. Stanley how things be? There's none comes back either from Heaven or Hell to tell us what the places be like. There's ghosts and spirits enough, but what do they do but gibber nonsense?"

"I cannot help you," replied the Rector, "until you speak to me more frankly. I entreat you to come to church, I entreat you to suffer me to give you some instruction."

"I'd rather go to Mr. Stanley for that," replied the giant. "He's a brave man and means what he says." The Rector flushed slightly; these sincere words seemed a reflection upon his own courage and his own good faith.

"I warned you about Mr. Stanley," he said swiftly. "If your mind is burdened either by your own secret or by that of another person, I can only entreat you to relieve it by a full confession."

"That's as may be," said the giant, with his hand on the door. Then looking up quickly, he added: "There's something you should know about young Esquire John Corbyn."

"There's nothing I should know of Mr. Corbyn from you, Sythe Torre," replied the Rector haughtily, "he is about to marry my sister-in-law."

"For that reason I should tell you, sir," said the miner confidentially, thrusting his thick neck forward and speaking in a hoarse whisper. Before Mr. Mompesson could stay him he added quickly:

"The young master was drunk down at Bakewell, at The Derbyshire Arms, and all the miners was about him and I was there. So was the mummers coming up to St. Helen's Wake. They'd got a wrestler with them and I tried a fall with him..."

"Sythe Torre," put in the Rector, "this has naught to do with me."