RGL e-Book Cover©

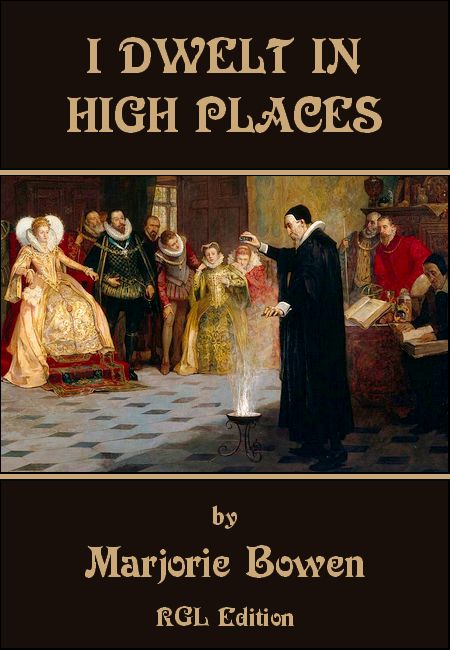

Alchemist John Dee conducting an experiment for Elizabeth I

Henry Gillard Glindoni (1852-1913)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Alchemist John Dee conducting an experiment for Elizabeth I

Henry Gillard Glindoni (1852-1913)

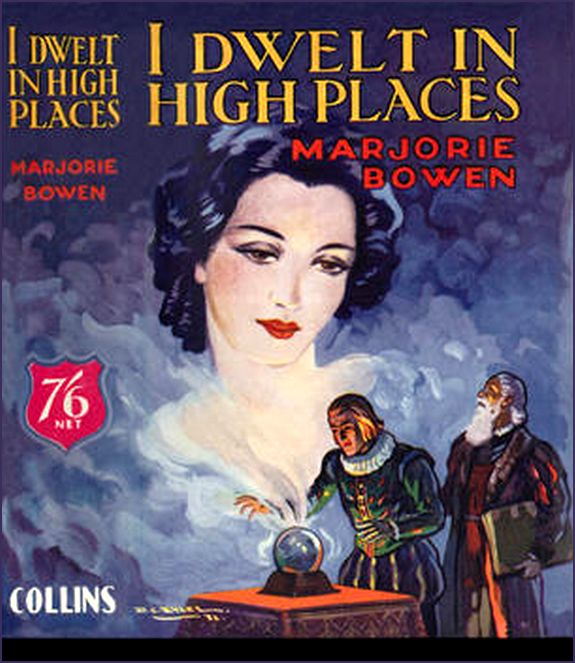

"I Dwelt in High Places," Collins, London, 1933

"I Dwelt in High Places," Collins, London, 1933

MISS BOWEN'S new novel has an Elizabethan setting. The character of the Queen figures in the earlier stages of the story at the Mortlake home of Dr. John Dee, her court astrologer. John Dee and Sir Edward Kelly, his extraordinary assistant, a man so remarkable that it is not yet known if he were charlatan or genius, are two of the main characters. They set out from Mortlake in quest of strange adventures and finally arrive at Prague, the home of the alchemists, and secure the attention of the mad Emperor Rudolph—himself an "adept." Edward Kelly gains complete domination over Dee and finally succeeds in winning from him his young and beautiful wife. The story is not a fantasy, but combines with the quest for the unattainable the sternest and most gorgeous realities of life. Miss Bowen makes splendid use of her material and has written a wonderfully effective novel of an heroic and gallant, if fantastic and wild adventure, against the lurid and magnificent background of the Renaissance.

To My Son

Athelstan Long

On His Entering The College

Of St. Peter At Westminster

(Westminster School)

May, 1932

Where Dr. John Dee's son, Arthur,

was received on May 3rd, 1592

I dwelt in high places and my place is in

the pillar

of the cloud.—The Book of Ecclesiastes.

Behold, He cometh with Clouds, and every eye

shall see Him.—The Book of Revelations.

A land of darkness, as darkness itself; and

of the shadow of death, without any order, and

where the light is as darkness.—The Book of Job.

JANE DEE pretended to herself that she had not heard the bell of the great door ring; it seemed, after all, but a tinkle in the sweet rushing and sighing of the March winds that filled the house by the river with the rumour of tumult. She was very tired after many weeks of anxiety and work, the coming and going of strangers, the illness of Arthur, her eldest child, the trouble with a dishonest maid and that strange frightening affair with Barnabas Saul, her husband's assistant.

It was so soothing to sit alone in the large parlour and to know that there would be nothing to do till supper-time when Ellen Cole would bring the two children home from Petersham, where they had gone to see Nurse Garrett, when her husband would come down from his laboratory and there would probably be visitors who would sit in the lamplight and talk of matters which she, Jane Dee, did not understand.

The wind blew down the wide chimney shaft and stirred the flames from the sea-coal fire beside which the exhausted woman sat sunk in the deep tapestry chair with arms, her hands interlocked behind her head and her long limbs outstretched. She could see, through the long, diamond-paned window, the grey river hastening by and, on the further bank, the bare willows, dragged sideways by the winds, the perished weeds and grasses of last year, beaten and broken above the soggy earth.

Trailing, loose clouds, one close above another, flew seawards. Jane Dee, watching this movement of river, clouds and willows, all swift, grey and flowing in the same direction, away from Mortlake, away from London, from England, out to the ocean, felt a sensation of release and freedom, as if her soul were loosened from her body and escaping down the river.

The bell tinkled again.

Jane Dee did not move. She hoped that whoever was without would go away believing the house to be empty. So many people came to see her husband on selfish errands, many of them consuming food that she, the anxious housewife, could ill afford, or staying for days in the spare room above the hall and demanding service that she could ill provide.

And so long a pause passed that Jane Dee believed that she had indeed deceived the person without and that he had departed. Her body, beautifully formed, relaxed in her shabby, heavy gown, and the pure outline of her face and throat sank against the faded cushions, while her large, dark eyes gazed drowsily at the passage of the clouds and water, the bend of weed and willow without the long window.

She was twenty-five years old, highly born, finely bred. An expression of proud resignation on her delicate face masked restless discontents. Nervous outbursts of violent temper had already marred her small features with fine lines of passion and regret, but her brow was noble, her movements full of grace, and there was about her all the dignity of a woman faithfully devoted to tedious duties, who never thought of her own pleasure or convenience.

Even now, as she sank into a half sleep, little worrying questions shot through her tired mind. Would Ellen Cole be able to get something for the baby's cough from Nurse Garrett? Could she be trusted to see that Arthur did not slip into the river on the way home? Would the new maids really arrive to-morrow?—and be of any use? Would that horrible affair with Barnabas Saul damage her husband? How would she contrive if some money did not come in soon?

They would have to sell something more—one of the standing cups with covers, perhaps. How she disliked seeing the good pieces of plate go out of the house!

The bell rang again, the sharp sound of it penetrated her drowsy worries. She sat up quickly, then rose with a sigh. Perhaps, after all, she had better go; it might be a messenger from someone important—even, perhaps, from the Queen.

As she moved towards the great outer door she frowned with vexation. Why must her husband choose to-day to send the two menservants, Benjamin and George, on some crazy errand in Robin Jacke's boat up the river, and why could not Roger Cook or one of the other assistants sometimes hear the bell?

It was all very well for them to shut themselves up in a distant part of the rambling old house and refuse to disturb themselves for anything; no one cared for her peace and quiet.

She opened the door in a temper, a vast rush of soft wind blew over her, and she found herself face to face with a stranger.

"My husband can see no one," said Jane Dee coldly, but she was conscious of a sudden exhilaration. The wind blew her clothes away from her body, her hair away from her face and she knew, for a second, the sensation of being disembodied, of mounting the wind and flying away from Jane Dee and all her cares and labours.

The stranger stood silent a second, holding his wide-leaved hat; his thin cloak blew about him and his head was slightly bent against the wind.

Jane Dee observed, curiously, the graceful shape of his person, and the intent stare of his pale, grey eyes. There was something remarkable in the silent persistency of his attitude.

"My husband will see no one," she repeated with less confidence. The wind rushed past her into the house and she put up her hand to catch at her flying locks.

"May I come in and tell you my business?"

"That would be no use, I know nothing of my husband's affairs."

But Jane Dee was slightly flattered, because no one had ever before treated her as anything but a housewife.

"You must know something of this, it has to do with Barnabas Saul."

She frowned, for this was an unpleasant subject.

"Come inside, then, sir, for I can hardly hear for the wind."

He was instantly across the threshold and she closed the heavy door. She frowned again, for her peaceful afternoon's rest was spoiled. She wished that she had gone to her own room where she would not have heard the bell, instead of yielding to fatigue and the fascination of the gray river view from the long window of the panelled parlour.

Yet she sighed as well as frowned; perhaps it was fortunate that she, instead of her husband, should deal with the vexatious matter of Barnabas Saul.

She sank into the tapestried chair beside the windblown fire and asked the stranger to tell her quickly what his errand was. She was unconscious that she was a beautiful object at which to gaze, for her worn dress was a pleasing grey-green, like the river without, and her black hair, slightly dishevelled, fell in lines of natural grace around her pale, serious face, while her attitude, weary and dignified, was unconsciously lovely. It was years since she had thought of herself at all.

"Have you come from Barnabas Saul? My husband will not take him back. He may have been acquitted," she added defiantly, "but I never believed him to be anything but a poor trickster."

"I daresay he was only that. No—I do not come from him. But to take his place."

"No!" exclaimed Jane Dee violently. "No!"

The stranger smiled and cast full on her his pale, sad glance. She rose, anxious to get him out of the house.

"My husband will have nothing more to do with that. He was cruelly deceived by Barnabas Saul. You must go at once."

"Is not Dr. Dee searching for a skryer, one who can see the spirits?"

"No. He will not meddle any more, I tell you. He is not interested in any magic."

"Surely you mistake, or else you are afraid of me, Mrs. Dee?" The stranger smiled gently. "My name is Edward Talbot; I can skry very well. I have a number of spirits at my command. I feel sure that Dr. Dee would wish to try my powers."

Jane replied vigorously.

"It is a mischievous folly. My husband, who has so much learning and wisdom, has been tempted to experiment; but it has already been worse than useless. A costly waste of time. I am sure that he will never try anyone else. He and his assistants are now much occupied in other studies."

Mr. Edward Talbot made no effort to move, though the lady stood impatiently, half-turned towards the door; and his very immobility caused her, against her own wish, to give him a keen consideration.

He was about her own age, very finely and strongly built, dressed elegantly in grey; his features were small, the nostrils flaring widely, the mouth beautifully shaped and pale; his eyes, very large and set wide apart, were extraordinary, light as silver, with a metallic gleam, so that he sometimes appeared blind, yet full of a brilliant life, of tenderness, humour and passion, and delicately set under straight, thin brows. The whole face was resigned in expression and of a peculiar, tragic beauty. He wore, what Jane Dee had only seen on much older men, a close cap of black silk, so tight fitting and drawn so low over brow and neck that none of his hair was visible. She disliked him intensely; he filled her with a shuddering apprehension of unnameable disaster.

He smiled as if he saw her fear and her weakening.

"I will remain here until Dr. Dee comes down from his laboratories. I am sure that he will give me a trial."

Jane Dee had not told the truth when she had said that her husband was not searching for a slayer. Despite the many failures that he had had, and the trouble with the rogue Barnabas Saul, who had been arrested for sorcery, despite the fearful dangers attending a study that might any moment contravene the laws and provoke the most frightful punishments, John Dee was still searching for someone who would help in the occult experiments that he could not resist.

Jane Dee felt uneasy. If this strange young man whom she disliked so much did wait for her husband and tell him that she had tried to 'turn him away, Dr. Dee would be very vexed and chide her for an ignorant, wilful woman. It would be better to face the danger boldly and to appeal to her husband to have done with this most perilous matter.

"Stay here, then," she said quietly. "I will go to Dr. Dee myself. Does he know your name or have you any friend of ours to answer for you?"

"None," replied Edward Talbot. He spread his hands to warm before the flaring fire, and she noticed how beautifully shaped they were and that on one index finger was a ring of polished jet.

John Dee was working in his laboratory with his assistants. This room, with adjacent workshops, occupied a large portion of the upper storey of the ancient house which he had inherited recently from his mother. He had added various buildings to the original structure and incorporated with it several cottages where his assistants and many of the strange guests whom he entertained were lodged.

These annexes were approached by a stairway from the laboratory, and had their own yard, so that Dr. Dee was shut away when at work from the original house and garden where his family resided, with Ellen Cole, the children's nurse, George and Benjamin, the two menservants, and two maids who were constantly being changed.

Jane Dee very seldom came to the laboratories; she was not interested in them, and she had a great deal to do in her own apartments. As she went down the long lobby which led from the house to the workshops she caught glimpses of the river from the low-set windows. The wind still blew strongly and the tide was racing to the sea.

The floor of the passage was very uneven, there were cobwebs and dust in the window frames and the plaster was flaking from the walls. Jane Dee sighed. This part of the house was beyond her province. She often complained of the inconvenience of the arrangements of the old building, but sometimes she was glad that she lived in this ancient house, which had been standing when her grandfather was young. She liked the garden, sloping to the river, the landing stage and the ancient arch, she even liked the low, rambling rooms, with the long windows, the rich, deep-cut panelling and the carved, painted roses on the ceiling. Often, too, when she was most vexed and weary she liked to think of the ghosts of all the other women who had toiled there and that some day she, too, would join them—a shadow among shadows.

She had to pass through the long library before she came to the laboratory. This was a place she could not see without great respect and awe, for she knew it to contain one of the most valuable collections of books and manuscripts in the world, said to be worth a very large sum of money, perhaps as much as two thousand pounds.

In this long, low room, which had been built in the old days for music and dancing, were several valuable scientific instruments which Jane Dee always regarded with exasperated admiration, so marvellous were they to her, and so incapable did she feel of even remotely understanding their purposes.

There was the quadrant made by Richard Chancellor, the explorer, who had perished years ago in the distant, dreadful White Seas; there was, swinging in a frame, a radius astronomicus or telescope, and two globes made specially for John Dee by Gerard Mercator, together with several compasses and theories, and many great chests full of boxes containing deeds, records, seals and coats of arms, all of great value to heralds and antiquaries, but depressing Jane Dee with a sense of dusty futility.

She would rather have seen great stores of household linen, shelves filled with jars of conserves and balm, bottles of medicine and wine, fine stores of soap and candles, good bales of woollen cloth and barrels of dried fish for Lent, all of which commodities the house at Mortlake was very deficient in.

Jane Dee knocked at the door of the first laboratory, then entered nervously without waiting for an answer.

There were three laboratories as well as rambling workshops beyond, and garrets filled with all manner of objects for chemical and mathematical research. All this portion of the house smelt of the fumes of strange compounds which were constantly being dissolved into vapours.

Jane Dee hesitated on the threshold. The room looked towards the river and was full of grey light that flowed through the northward windows. Roger Cook, the eldest of the assistants, sat at a long table covered with glass retorts and limbecks that shone like bubbles; he was mixing a red paste on a little square of alabaster and his demeanour was, as usual, melancholy and sullen. He pretended not to see Jane Dee, but hunched himself more closely over his work.

John Dee was standing at a sink in the corner, showing Mr. John Lewis, the doctor's son, how to draw essential oils. This youth was the last and youngest of the assistants, and Jane Dee disliked him because her husband had promised him a hundred pounds if he would help him in some discovery on which he was engaged, and Jane Dee could not endure to think of so much money being paid away for nothing when they were in debt with so little coming in.

She sympathised with Roger Cook, who was bitterly jealous of this diligent, quick young man who had become at once such a favourite with his master.

"Sir, Dr. Dee," she said, for she was always very formal with him. "There is someone to see you whom I cannot be rid of." Vexation made her voice shrill. "Yet he has brought no word from any friend and seems to me a rogue."

"Why, Jane! You should not have come yourself—taken the trouble—"

"There are no maids," she reminded him quietly. "Ellen Cole has taken the children to Petersham and you sent the men up the river, I don't know why, so I had to go to the great door myself."

"Ah, yes, I am sorry, Jane," he looked at her remorsefully. He was always very kind and gentle with her even when she was sullen or angry, but often, for hours together, he would forget about her and her troubles and burdens; she believed that he had no idea of her anxieties and fatigues. She had never loved him, but she felt a great respect for his wisdom and learning, and an irritated compassion for his lack of all practical qualities, and even, at times, an affection for his candid, childlike goodness. He was thirty years older than Jane. They had been married three years and she was entirely devoted to his interests.

He wiped some drops of oil from his hands and set her a chair, while he questioned her about the persistent stranger.

Jane Dee watched the scudding clouds driven by the flying east winds and answered reluctantly. She was annoyed at the quick interest that her husband showed when he heard that the man claimed to be a seer of spirits.

"I should have thought that you would have had a lesson with Barnabas Saul," she said sharply. "This is such another—an evil creature, I'm certain."

Roger Cook gave her a dark glance of sympathy. He had been unable to see any spirits himself and loathed those who claimed that they could do so.

"I might try him, Jane. You know how long I have searched for this—"

"But why? It is dangerous, forbidden by law—"

"Only dealings with evil spirits or the souls of the dead are forbidden, Jane. I have told you so often," he added gently, "that I do not propose any matter that touches secrecy or magic."

"People think that you do; all manner of slanders and rumours go up and down."

"The vulgar always look askance at wisdom and learning, Jane. I am protected by the Queen, who is herself greatly interested in the possibilities of these experiments."

"If you are obstinate in this, Dr. Dee, you will ruin us all." The tired woman spoke with great earnestness, nervously clasping her hands. "You neglect the work that brings you just fame and the money that we so much need, for idle, perilous speculations. You lay yourself open to the tricks of rogues and cozeners, you expose yourself to the derision of serious men."

"Mrs. Dee speaks very wisely," said Roger Cook with a scowl. "I shall go and speak to this impostor, and if he be saucy, hand him over to the law. Perhaps he will not be as lucky as Barnabas Saul."

"Ah, Roger Cook, for a long while you have been picking and devising a quarrel with me. I have had much to endure from your melancholy, jealous humours."

Dr. Dee spoke regretfully; he was fond of Roger Cook, who had worked faithfully under him for fourteen years, and who only of late had revealed himself as morose and lacking in understanding and sympathy. John Lewis, although pretending to occupy himself with the phials of oil, was listening eagerly to the conversation; though he had no psychic powers himself, he was intensely interested in the subject.

Dr. Dee questioned his wife gently about the appearance of this stranger and she replied shortly, affecting forgetfulness, though the figure of the young man with the small features, large grey eyes and close black cap was as vivid before her as if he and not her husband stood before her outlined against the windy grey beyond the window.

John Dee was a tall, spare man, alert and vigorous, who, though fifty-five years of age, seemed only in the prime of life; his features were precise and clear cut, his deepset eyes, heavily lined and shadowed from excessive use, sparkled from a continual enthusiasm; a close-cut, thin beard shaded his jaw and chin; his dress was severe and neglected. As he took off his work apron his wife addressed him with asperity.

"Where have you sent George and Benjamin? I have no one in the house to-day at all."

"They have gone to Henley to fetch the Arabic book I lent to Mr. Dalton."

"Was there need for two of them to go?"

"The book is very precious, Jane."

"And of more concern than my comfort, I suppose!"

To distract her he took a morsel of feathers from the window sill and showed it to her on the palm of his fine hand.

"Why, Dr. Dee, what is that but a dead sparrow?"

"The cat caught it—you will notice, Jane, that it never has had but one wing—that is all Nature gave it."

Roger Cook exclaimed rudely:

"There are many like that, who fly lop-sided and drop to the ground and are devoured in the end."

"And there are those who are not winged at all, but must always crawl, Roger Cook," replied John Dee mildly, as he slipped into his furred gown and left the laboratory.

When John Dee entered the large panelled parlour the stranger was standing by the fire, which now burnt clearly, for the wind had abated. The clouds were torn apart in the west, and a dull red stain began to flush the tossed heavens. Mr. Edward Talbot was looking at this prospect which was clearly visible from the long, low window, when Dr. Dee spoke to him:

"Sir, why have you sought me out?"

"Dr. Dee, you are the wisest man in England. You possess all the worldly learning of which man is capable. In history, logic, geography, languages, chemistry, mathematics, in curious, rare knowledge, in the wonder of experiments with optics you have no equal."

Dr. Dee accepted these words, which were spoken without flattery, without embarrassment; his reputation was perfectly established in Europe.

"Worldly learning," repeated Mr. Edward Talbot, with his air of quiet self-confidence emphasised. "And now I hear that you, replete with this knowledge of earthly matters, would study the world of spirits."

"Only if this may be done with reverence and piety. Far be it from me to dabble in magic or any form of sorcery—"

"Yet you, yourself, Dr. Dee, were once arraigned for the practice of witchcraft?"

"I thought that most men had forgotten that; it must have happened before you were born—"

"Yet I have heard of it. Before the Star Chamber and Bishop Bonner in '53, was it not? A man named George Ferrys accused you of, by spells, blinding one of his children and killing another?"

"That is so," replied Dr. Dee with some anger. "But I was cleared of all suspicion. The charge was the invention of malicious ignorance. At the time I was writing two books for the Duchess of Northumberland, one of which, Ebbs and Floods, was much commended."

"That, too, I know. Yet I believe that you have been much vexed by spiteful rumours that you deal in black magic? Even your late medium, Barnabas Saul, was accused of sorcery."

"But acquitted. Yet now he says he can see no more spirits."

"Did he ever see them?" asked Edward Talbot sharply.

"I do not know. For myself, I can see nothing. I have to thank my God for many talents, for much industry of mind, but that gift has been denied me." John Dee spoke sadly and, stroking his thin beard, looked away across the room, to the river without.

The deepening red light of the sky was reflected on his face, at once noble and simple, that Edward Talbot was subjecting to a passionate scrutiny.

"Barnabas Saul had some such power, as I believe. He had a spiritual visitor when he lodged over the hall, here, in this house. And I myself had strange dreams when he was here. He saw figures in the cristallo. And one directed me to go to Oundle in Northampton, to look for some books buried there."

"You search always for buried treasure? For books and manuscripts, eh, Dr. Dee?"

"I have always tried to preserve the treasures of the monasteries which have been, all over the country, dispersed and destroyed. I petitioned the late Queen, in '56, to allow me to found a national library. I have saved much by my own endeavours."

"Were the books discovered at Oundle?"

"No."

Mr. Edward Talbot laughed softly and the sound caused Dr. Dee to come sharply to a sense of the impropriety of this conversation wherein he was being questioned by an utter stranger, as equal to equal. Jane Dee had often, harshly enough, chidden him for his easiness and self-absorption which allowed all manner of people to take advantage of him. He glanced apprehensively at the young man, as if to discover his charm, for some fascination he undoubtedly exercised.

"And now, sir, you must explain yourself. Who are you?"

"My name is Edward Talbot." The green-grey eyes were full of fire and candour. "My history is curious and not easy to be believed. It would be tedious to tell it now. I have studied at Oxford. I have wandered much, particularly in Wales, the land of the mystics. I have some knowledge which you may, on examination, test." John Dee was greatly attracted by the eager, wild face, the quick ardent words, and by the mention of Wales, for he much cherished his own Welsh descent, but, simple-minded as he was, he reminded himself: "The last man cozened me."

"Have you anyone to speak for you, Edward Talbot? Not only am I loath to waste time, but to practice these matters with a cheat is, in a certain sort, blasphemy."

"I have kept myself hidden from all. I have something precious to conceal." The soft, caressing voice that was touched by an accent strange to John Dee, sank to a whisper. "Something that I can show only to you—a manuscript."

John Dee's face was sharp with interest.

"Where did you find it?"

"In the most sacred spot in Britain—Glastonbury, and with it were two phials of red and white powder."

"What are these?"

"Though I have studied alchemy, I do not know. Nor can I decipher the manuscript. But I can guess what precious secret I have stumbled on."

Dr. Dee controlled his excitement.

"The elixir? So many have been deceived. But in Glastonbury! What is it like? Have you tried any experiments with it?" He checked himself. "But it was as a seer of spirits that you came to me?"

"That is part of the same mystery. The spirits do visit me. But I have not the globes, the tables nor even the peace of mind necessary." He clutched the arm of the elder man. "Look yonder! See, the clouds have fled, and what glory stains the sky!"

Infected by this enthusiasm, which amounted to exaltation, John Dee gazed from the window. An aurora borealis of crimson, scarlet, gold and violet brightened the eastern and northern heavens, and was reflected in brilliant flakes on the river, still agitated from the rage of the lately hushed winds. The reflection of this almost intolerable blaze was in the panelled parlour and dimmed the glow of the sinking fire.

"You see," cried Mr. Edward Talbot wildly, "the very heavens send an omen to mark my coming to you."

He stood with his face turned to the window, and the fiery glow stained his features red and gave a look of flame to his strange eyes, over which the straight brows frowned.

John Dee was much moved by this face, which had at that moment an unearthly beauty, tragic, wistful and almost terrible.

"Fetch your manuscript, Mr. Talbot, and bring that and the powders to me."

Jane Dee also watched the extraordinary sunset which cast such furious colours into the east and north. The willows on the opposite bank were now dark and insignificant, the mud and dead weeds on the river bank were transformed into lines and droplets of light, where the blaze caught the rain drippings. Jane thought of the marvellous Elixir of Life and Philosopher's Stone of which she had heard so much, and which was capable of turning all that it touched into gold. Her husband had often spoken to her of this but he had not yet tampered with hermetic experiments, or so she believed. Yet, with what reverence would he speak of Roger Bacon, Saint Dunstan, Raymond Lull, Albertus Magnus and Paracelsus, who had always striven to achieve illimitable knowledge, to set free the spiritual elements in all chemical substances and metals, and to attain god-like powers of wisdom, of healing and to learn secrets hitherto unguessed at by man!

How often had not her husband spoken to her of the vapours rising from his retorts, the souls of the various substances being compounded, and of the strange shapes, some menacing, some gentle, with which these spirits escaped into the air.

Gold! Jane Dee leaned further from the window and watched the transient glitter on river and puddle, the vapours which seemed to burn in the harsh blue heavens; the metal weather vane on Mortlake Church appeared to be on fire. She knew that the discovery of the transmutation of metals, the knowledge of how to make gold would be as nothing to her husband compared to that other wisdom he hoped to attain, but, for herself, she would very gladly have had a little of the precious metal, even if it were only to the value of a hundred pounds.

Though her husband was so famous, so sought after, so learned, though he held the envied post of Astrologer to the Queen, the only sure income that he could count on was eighty pounds a year which came from the Midland rectories which he held as sinecure through special dispensation of Archbishop Parker; the rest of his revenue had to be made up from odd, erratic gifts from the Queen and other patrons, like the Walsinghams or the Burleighs, by fees from pupils and presents from visitors who came to see the famous library or to have their horoscopes cast, from the Mortlake property John Dee had lately inherited from his mother, and, too frequently, by loans or the sale of some valued object given to the astrologer by a wealthy client.

Jane Dee frowned; mentally, she accused the Queen of being fickle and forgetful—how often had she not promised her faithful servant whom she valued so highly some benefice or lucrative post? More than once she had named him Provost of Eton and then, at the last moment, the coveted place had been given to another.

Thinking of these things, Jane Dee forgot the sunset and went sadly downstairs. She and Ellen Cole would have to set out the supper, probably there would be visitors, and Roger Cook would be asked in, and her husband would forget that they had no cook and ask why there was no hot dish, but only cold pies, pressed beef and cakes.

Ellen Cole had returned with the two children; she was taking off their cloaks in the panelled parlour; her arms, she said, were aching from carrying the heavy baby, Katherine. And what a sunset! Petersham fields had seemed alight.

"What did Nurse Garrett say of Kate, Ellen Cole?"

"She gave me some drops for her. She said that she was thriving finely."

Jane Dee took the baby greedily; when she had a child held to her breast she felt at peace, whatever her troubles. She much disliked sending her children out to nurse and having to go long walks to see them for a brief space when she longed to have them about her always in the house. She was unhappily conscious that perhaps little Kate had been weaned too soon because she had been impatient to fetch her from her foster-mother at Petersham.

Jane Dee leaned back in the shabby chair, clasping the heavy, drowsy child close under her chin, while she watched Arthur, half asleep from the walk and the wind, nodding on the stool at her feet. His perfect little face was stained by gingerbread crumbs, his bright hair stood up in little curling feathers on his head, he stared into the fire that Ellen Cole was replenishing; he was half asleep. Only in her children did Jane Dee feel a complete satisfaction; she hoped that she would have a large family, but she was torn by worrying fears as to how many children could be supported and educated. And this conflict between maternal desire and worldly prudence angered her and her anger turned on her husband, who had so little concern in practical matters and could not understand her great need of comfort and protection.

So when John Dee came in from the garden with mud on his habit, her private musings caused her to give him cold looks.

But he did not observe these, being occupied by the marvel of the light in the heavens, and the strange visit of Mr. Edward Talbot.

"He is a rogue if ever there was one," said Jane Dee, scornful above the sleeping child on her bosom. "I hope that you turned him away. Who is there to supper tonight?"

"Sir George Peckham, who comes to consult me about charts and rudders—he goes exploring in North America and brings his sea master, Mr. Clement. He has promised us some fish for Lent, Jane," added John Dee, seeing her weary, sullen look.

"Ay, promises!" She rose and gave the child to Ellen Cole; her hour of peace was again disturbed; she knew how these seamen ate and drank and talked.

"And, Jane, Sir Harry Lee brings his brother who has been in Muscovy. Did you note the sky, Jane? It was a portent, surely, like the meteor last August—"

She paused at the door, her keys in her hand.

"A portent of what?" she asked suspiciously. "You have sent away that Edward Talbot?"

"He has gone," evaded Dr. Dee. "He lodges at Petersham."

"Do not allow him here again. Though I cannot see the spirits I know that that man will bring misfortune."

She went out into the great kitchen; the two menservants had returned and were getting up the fire. Their appearance was a new vexation; they would want beer, bread and meat, and would be in her way while she was preparing the supper.

As she unlocked the case that contained the scanty store of nutmegs, cloves, ginger and pepper, she questioned them as to the success of their journey.

This had proved fruitless; Mr. Dalton was away from home and had taken the precious manuscript with him and then the servants had hired horses to return because by river it took so long. So good shillings that Jane Dee could have well spent herself had been wasted as well as the time of the servants, who were well paid and ate a great deal.

Jane Dee turned aside sharply to hide the vexation on her face. The colour had faded from water and land, all was dull and grey; the pale sky had the appearance of being bitterly cold.

John Dee's guests came late that night and talked much of the voyages they had made and the voyages they hoped to make, and the newly discovered lands and seas of which the astronomer had made maps and charts. They told many marvels to the learned doctor, whose soul dwelt half in a world of phantasy and speculation, and such talk was sufficient to dissolve the walls of the old house at Mortlake and send him voyaging on vast and desolate oceans or through untracked forests.

He rejoiced that he lived in these modern times, when, as it seemed, most unexpectedly, and surely through the wish and guidance of Divine Providence, all the world was opened up to eager adventurers, and every day brought some marvellous discovery, either in the realms of Nature, or in those of science, or in the finding of strange countries and peoples.

He had travelled much, but he would have liked to have been off again with these bold, eager men, searching for the strange, the unknown and the beautiful. They lacked money; although such enterprises as theirs were generally profitable, it was often difficult to raise sufficient shares in the companies that financed these voyages of discovery, and Mr. Clements, the sea master, asked Dr. Dee with a laugh if it were not possible for him to discover the Philosopher's Stone and give them a few scrapings of gold with which to fit out their ships?

This brought back his visitor of that afternoon to the astronomer's mind and he felt a glow of pleasure and excitement at the thought of Edward Talbot and his queer grey eyes, his self-confident, excitable manner and his talk of the great book found in the ruins of Glastonbury, perhaps on the very spot where Saint Dunstan had practised his magic, and of the red and white powder which might hold some long-sought and tremendous secret of transmutation.

He said nothing of this, but told his guests that he was in a like state to their own—always on the verge of some discovery, and always lacking the means to proceed further in his studies, hampered by the need for pence. His experiments, he reminded them, were near as costly as their voyages; they would be surprised, he was sure, if they were to see his account at the glass-works at Chailey, or what he owed John Fern the potter, who lived by the ferry, for making him all his vessels and building his brick furnaces, while as to what he spent in chemicals, in books, in costly instruments, it was not to be mentioned.

Jane Dee listened with antagonism to all this talk. It sounded to her like boasting; though she did not doubt the wisdom of her husband, nor the courage of the other men, she felt that all of them would have done better to set their minds to simpler things. She thought of all the women she knew who were married to plain men who went about their business and kept out of debt and could afford silk dresses and chains and horses for their wives.

She sighed in vexation as she ncticed the amount of food and drink consumed, the number of candles that were burnt down to the sockets, and all for the sake of talk about wild, barbaric lands like Cathay and Muscovy, and frozen seas where there were nothing but bears and ice floes, where the bodies of adventurous men bleached.

She left them at last, leaving them to their charts and designs, their talk of compasses and winds and waves, and they did not notice her going. She went upstairs thinking anxiously of the morrow and of the money that must soon be found somehow to pay the servants, and for food and interest on loans; the old house was mortgaged and her own marriage portion had long since been spent, and all they could obtain from the Queen and their other patrons were words and vague promises.

Jane Dee looked at her children who slept in little beds either side Ellen Cole in the large room over the parlour.

The river was still and sparkled with reflected stars. She paused by the window to look out over this dark but peaceful prospect. The red lantern of a barge passed slowly by; there were other lights, warm and kindly, glimmering in the windows of farm houses on the north bank, across the obscure fields.

Jane Dee felt comforted. She was not like her husband, versed in astronomy and astrology; the stars were to her but so many lights, far away and mysterious, and yet the sight of them gave a sense of protection. She stood for a while with the curtain in her hand, looking from the prospect of the river, the dark fields, the garden and the stars, to the two sleeping children. Then she went softly to her own large bedroom with the sloping floor and the worsted hangings worked in pale green wool, the labour of herself and her mother in the days before she was married.

She undressed in the dark to save the candle, putting her clothes carefully, one by one, on the large, old chair that had belonged to her husband's mother.

The starlight, which glowed through the low, latticed window, was sufficient to show her the large bed with the handsome curtains of twill lined with silk. She thought that they might perhaps sell these and replace them with something cheaper. The night seemed very still after the sudden dropping of the wind which had sighed round the old house for so many days. In this soft darkness she found it difficult to believe in the brilliant colours of the marvellous sunset. Like an evil vision, too, in the remembrance, like a phantasy wrought from her fatigues and fears was the figure of Edward Talbot; she hoped that she would never see him again.

It was nearly dawn before the two gentlemen adventurers at last rolled up their maps and charts and put away their note-books, called up their servants, and rode away from Dr. Dee's house at Mortlake.

The astronomer had no thought of sleep. He took the last candle which remained from his wife's cherished store and went through the quiet darkened house to his laboratory.

Edward Talbot had been in his mind all the evening, and he went directly to the small attic above his workshop in which he kept his shewstones. He had two of these; one had been left by a friend who was also an alchemist, and one he had purchased himself some years before. This was of opsidian, a ball of volcanic lava from Ethiopia, polished till it shone like glass; the other was a globe of pure crystal. It was in this that Barnabas Saul had seen his few visions. John Dee had tried several mediums with both the shewstones, but the results had been disappointing. This, however, had not in any way shaken the astronomer's faith. His entire being moved in a world very far from everyday matters and there was nothing to him strange or terrifying in the thought that he might get into direct touch with the Angels of God.

He had had, himself, strange experiences, deep dreams and tumultuous visions, and voices singing in his ears. But the power of seeing the angelic beings whom he knew surrounded him had been denied him, for that he must be dependent on another person, and though he had been several times deceived and cheated, his faith in the possibility of finding this person was by no means shaken.

He handled the two globes, both of which gleamed and glittered in the light of his one candle, and, with increasing excitement, he thought of Edward Talbot. His desires were all sincere and unselfish; he had no worldly ambition and felt no hankering after any of the lures which usually serve as baits for mankind. Money, in itself, was nothing to him, nor were honours nor titles, nor the favours of princes, yet he was always in need of money for he spent lavishly on his books, his instruments, his studies, and he was often, too, deeply galled to think of poor Jane, so careful, so anxious, so uncomplaining, so often put to great straits from which he could not relieve her. Almost he wished he had not burdened himself with a wife and children. When he had taken Jane Fromont for his second wife, he had believed that the Queen's deceptive promises would, at last, resolve themselves into some definite benefit for himself. But this has not been so, and he was at present in severe pecuniary difficulties, owing at least three hundred pounds, with nothing certain coming in beyond the eighty pounds from his two Midland rectories, and a few odd golden angels which might be expected from the casting of horoscopes or the drawing of charts and maps.

He put his little candle on the plain table before him and sat down between the two globes, each of which was in a specially constructed wooden frame.

He was fifty-five years of age, healthy, and full of vigour. He had never known an unworthy thought and what he had ever experienced of base and ugly in his dealings with his fellows he had soon forgotten. He had travelled much, read much, experimented much, and his mind had journeyed to the furthest limits of human knowledge, to those infinite spaces where the finite mind reeled, the senses dazzled, and human calculation seemed but a straw borne along the wind of eternity.

He had for himself seen so many marvels that he was ready to believe anything; he thought that only the ignorant and the stupid were incredulous. The study of chemistry, of optics and of mathematics had taught him that many things which might appear miracles or magical to the vulgar, were, in reality, but the result of the sequence of natural laws. He was warmly conscious of living in an age of transition, when many old beliefs and superstitions were cast aside like worn-out garments, and the blinding light of truth was let in to what had been dark places.

He had seen, for instance, the astronomical system of Claudius Ptolemeus of Alexandria overthrown. These beliefs, the result of centuries of study and observation, had held the obedient reverence of mankind for nearly fifteen hundred years. Who had ever dared to dispute that the earth was the stationary centre of the universe, round which moved eight transparent crystal spheres, each of them containing a heavenly body—the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the fixed stars, with a ninth sphere named Crimum Mobile or sometimes the "Motion" which gave the motion to all the others? These spheres, revolving round each other, produced each a several note of music named the "Music of the Spheres."

This Ptolemaic system, as set forth in the Almagest, as the Arabians named this syntax of astronomy, had been spread throughout the world and was universally regarded as unchallengeable, until Nicholas Kopernicus, a professor of Mathematics at Rome, evolved, from his own studies, an entirely new theory. He taught that the Moon revolved round the Earth, and that the Earth was merely one of a number of planets revolving round the Sun; that the apparent motion of the heavenly bodies from East to West was caused by the actual motion of the Earth upon its axis.

Nicholas Kopernicus had had the prudence to keep his discoveries known only to the few until he was on his death-bed, but John Dee owned a copy of his work on the Solar System and had been one of the first Englishmen to study the new theory.

He thought of it now with excitement and elation—if it were possible for the wisdom of the ages to be thus scrolled up like a badly-written page of manuscript cast into the fire and regarded no more, if the mind of this one man, Nicholas Kopernicus, could re-cast the celestial system, if ordinary men like Mr. Clements, who had sat below an hour or so before, with his drink and his food and his charts, could go out and discover new seas, new lands; if man could be inspired to mix from the minerals of the earth compounds that could heal or blast; if, by Divine grace, it were to be permitted for the first time that the great sciences of optics and mathematics and chemistry should be laid bare to the human intelligence, why should it not also be permitted in this great, adventurous epoch that man should converse directly with the spirits of God?

John Dee was almost tired of intellectual knowledge. He could not remember when he had not been a diligent scholar in every branch of learning, all had come to him so easily. He had been a fellow of St. John's College, Cambridge, at the age of fifteen. As a young man he had discussed mathematics as an equal with the learned men of the Dutch universities, Gerard Mercator, Gemma Frisius, and Antonius Gogava.

How long ago it seemed since he had been a student at the University of Louvain, even then famous for its learning, graduating as a doctor before he was twenty years old. Famous men of all nations had come from the brilliant court of Charles V. at Brussels to see and discourse with the famous young Englishman. And afterwards he had lectured in mathematics at the College of Rheims, in Paris. The audience had been older than himself, and so large that the school would not hold it. In those years he had come into close touch with every man of note in all branches of learning; he had had correspondents in the Universities of Orleans, Cologne, Heidelberg, Strasburg, and the great universities of Italy. All that seemed very long ago, and, in a way, useless now.

He had read and written on almost every subject open to the play of the intellect of man. He was a personal friend of all the great men of England, flattered by them, consulted by them, often spending his time and energy in the service of their whims and fancies. He was Astrologer to the Queen; she regarded him with a strong affection and undertook little without seeking his advice. He had to live at Mortlake to be near the Queen's palaces of Richmond, Sion House, Hampton Court, Nonesuch and Greenwich, and yet the Queen would not give him some substantial salary or place which would keep him from worldly want and anxiety as to the future.

And as he sat between his two globes, the dark sphere and the light sphere, in the glimmer of his one candle, looking at the stars which gleamed between the folds of the drugget curtain at the narrow window of the garret, the old man wondered if he had placed too much dependence on an earthly sovereign, considered too much worldly wisdom and the acquiring of worldly knowledge.

Every subject that man had ever studied, every school of thought, every speculation of ancient and modern wisdom, was debated in the valuable volumes which formed his precious library. He himself had written much, rapidly and carefully. There was, surely, something beyond all this, a Divine wisdom, which the humble in spirit and the pure in heart might reach without the intervention of books or writings or experiments with limbecks, retorts and furnaces.

He knew himself to be a sincere and pious Christian and such was his exalted state of mind that he felt no presumption in daring to hope that God would give him a direct guidance by means of his angels in order that he might achieve that high and pure wisdom which would bless the world with a flood of enlightenment and healing, as grateful to the corrupt and sluggish ignorance of mankind as a flow of crystal water in a parched, neglected desert.

Surely, he thought, sitting sunk in his chair and looking at the strip of stars between the drugget curtains, this man, Edward Talbot, might have been directly sent to him, at this, the hour in which he had come to the limits, as it were, of his present knowledge, exactly when his insatiable desire for intercourse with the angels of God had become almost intolerable, when his longing to lay himself and all he knew at the Divine service, had become almost insupportable.

He was, at least, sure that Edward Talbot was no ordinary man. The manner of his coming had been strange; how peculiar was his person, at once beautiful and wild, and his address, ardent and full of self-confidence, how gentle and appealing! If it had not been for poor Jane Dee he would have had the man up at once into his laboratory and let him sit before the crystal and search in its depth for the figure of an angel.

The old man rose and went to the window and pulled aside the worn, dusty curtain. The colourless light of dawn was over the flat landscape, the wet fields, the huddled farms and among the leafless trees. The stars were fading behind the pale vapour, the river was flowing steadily eastwards.

John Dee, though weary, felt exalted and indulged in phantasies. He saw himself wandering away from Mortlake and his daily burdens, cares, worries and interruptions, going away with Edward Talbot—yes, he surely would be his chosen companion—they would travel together through the mystic valleys of Wales—they would climb those veiled hills, they would search through the mysterious fields of the Isle of Avalon! Had not Edward Talbot said that he had discovered a marvellous book which he could not decipher among the ruins of Glastonbury, the cradle of Christianity in England, where St. Joseph of Arimathea had planted one of the thorns from the crown of Christ, which might be seen even now, blossoming fairly at Christmastide.

This was the manner of hidden treasure that attracted John Dee. He did not care much for gold, greatly as he needed it, and sorely as he was often pricked by the lack of it. But these books, manuscripts and precious secrets of the wise men of the past had always lured him. When he was a young man he had gone abroad searching in Holland and Germany for such volumes, many of which he had found. He remembered copying out such a one—a treatise upon shorthand and cipher by the Abbot Trithemius of Wurzburg. He had done it in ten days with the help of a Hungarian nobleman and when he had brought his copy back he had taken it to the Queen and she had read it with him in her little private walled garden at Richmond Palace. And afterwards, in a princely and heroical fashion, she had comforted and encouraged him in his philosophic and mathematical studies.

But all this was over now and seemed, indeed, very long ago.

John Dee closed the curtains. He was touched by a sudden panic fear—supposing that Edward Talbot did not return, or supposing that he came back and refused a glimpse of his precious manuscripts and mysterious powders?

John Dee took an olive wood rosary from his girdle and went into the neighbouring room, which was fitted up as a small oratory, and there prayed, very earnestly, that it might be permitted to his simplicity, purity of intention and singleness of purpose, that the Angels of God would commune with him.

At twelve o'clock of the next day Edward Talbot returned to Dr. Dee's house at Mortlake.

The astronomer had sent Mr. Lewis to watch for him so that Jane might not be disturbed by the sight of the man to whom she had taken such an unfortunate and unaccountable dislike.

Mrs. Dee was occupied with her new maids and it was not difficult for the astronomer's assistant to look out for Mr. Talbot and bring him quietly and quickly to the laboratories.

As he entered the first room where John Dee awaited him, the astronomer scarcely dared glance at him, so afraid was he that the impression he had received yesterday would not be confirmed, and that the personality which had appeared to him so magnificent and peculiar, might now be faded and commonplace. But one glance at the person of Edward Talbot reassured him. Here was no ordinary person, but one full of a strange fire and vitality—a very Mercury himself.

"Have you brought the book, Mr. Talbot?" asked the astronomer anxiously.

The young man shook his head. He was very pale and still wore the close black cap. His hat he carried under his arm.

"No, I have hidden it carefully. I do not wish to carry either that or the powder abroad in daylight."

"It would have been safe enough," replied John Dee with gentle dignity. "I and my menservants often go abroad with such treasures, and we are not molested. This is a peaceful place. But," he added, with an eagerness he scarcely tried to disguise, "come with me and see if any vision is allowed you in the shewstones." And he took the young man by his short grey cloak and led him up the wooden stairs to the garret where he had the two globes of opsidian and crystal.

John Lewis was very desirous to follow, but his master told him to stay below and beguile Roger Cook, who was not by any means to know that spiritual experiments were taking place.

When they had reached the little attic where he had spent a portion of the night between the two globes, John Dee was trembling with excitement. He saw that Edward Talbot was looking at him very curiously.

To turn the subject a little and give himself a certain pause in which to collect his strength, he asked the young man which, among his studies, was his favourite delight?

Edward Talbot shook his head.

"I have not gone very deeply into any matter save this of magic," he replied.

"Then you have missed much," replied the astronomer. "Have you not studied music and harmony?"

"No!"

Mr. Talbot appeared to be giving very little heed to the questions, but was looking quickly and easily about the room, taking in, it seemed, the details of all the objects therein.

"My favoured study, and this after many years delving into all the sciences, is mathematics," said John Dee.

He put his thin white hand lovingly on the opsidian globe.

"I know very little of that," replied Edward Talbot.

He was staring at the black globe, his broad lids drooped over his pale eyes, his mouth was rather grimly set.

"I am sorry for that, Mr. Talbot, for mathematics, next to theology, is most divine, most pure, ample, profound, subtle, commodious and necessary."

"I have done very well without it, Dr. Dee."

"But you will find, if you wish to progress in your studies, it is most necessary. Do you not remember what Plato said: 'Mathematics lifts the heart above the heavens by invisible lines, and by its immortal beam, melts the reflection of light incomprehensible and so procures joy and perfection unspeakable.'"

The young man shook his black-covered head impatiently.

"I hear very little of such matters from the angels. I believe when I get into divine company mathematics is of little account."

There seemed a touch of flippancy in this remark, which caused Dr. Dee an unpleasant shock. Was it possible that he had again met with a cheat and cozener like Barnabas Saul?

He put courteously a chair for the young man, who took it with a certain restless impatience as if he would be done with talk and would be on with some action. But Dr. Dee, with a last lingering of worldly prudence, made some effort to question this new disciple, assistant, whatever he might prove to be, as to his ability and knowledge.

He asked him something about optics and if he had ever heard of the convex mirror which he, Dr. Dee, possessed, and on the young man shaking his head and impatiently professing ignorance, he passed on to other matters such as mechanics, and asked him if he had heard of the water mills at Prague, where long deal boards were sawn without any man being near; if he had ever heard of the diving chamber supplied with air, or of the brazen head made by Albertus Magnus, which spoke; of images, which, by means of perspective glass, could be thrown into the air; or the sphere of Archimedes, and of that famous German workman who was able to make an insect of iron which buzzed about the guests' table and then returned to his master's hand again as though it were weary?

"Do you speak of magic?" asked Edward Talbot. The smile on his pale, beautifully-shaped lips had something of a sneer.

Dr. Dee became angry.

"All these things are easily achieved by skill, will, industry and ability duly applied. If any student or a modest Christian philosopher did these and such like things, mathematically and mechanically, would you count him to be a conjurer?"

"I believe he would be so named by the vulgar, Dr. Dee."

"Have you not the knowledge, Mr. Talbot, to see that such accusations are but the folly of idiots, and the malice of the scornful, who seek to injure one like myself who seeks no worldly gain nor glory, but only asks of God the treasure of heavenly wisdom and knowledge?"

"There are many stories told of you, Dr. Dee, and have been for years, which incline the ignorant to believe that you are a conjurer and sorcerer."

John Dee's anger flared away. He replied with a wistful mournfulness:

"It is an age of wonders, and I cannot understand the incredulity of mankind. If I wish to find more cause to glorify the eternal and almighty Creator, shall I be condemned as a companion of hellhounds, and a caller of wicked, damned spirits? How great is the blindness of the multitude as to things above their capacity!"

"Do you know too much to be deceived?" asked Mr. Talbot with a keen eagerness.

"I have had many years of study and I have fished with a large and costly net and been a great while a-drawing of it in with the help of Lady Philosophy and Queen Theology and shall I at length, catch nothing but a frog, nay, a devil?"

"Then, sir, if you are so sure of yourself, you will be able to know if these spirits which I, by chance, may raise, are of God or the Devil."

At this the astronomer was dismayed. A certain fear, that he might not thus be able to distinguish among the spiritual creatures that might appear to him, did trouble him.

"God knows," he said simply, "my intentions are pure."

Edward Talbot was looking at the crystal shewstone.

"What have you, or any of your slayers, seen in this?"

Dr. Dee recounted quietly that an angel named Annael had appeared in that stone to Barnabas Saul, and to some others.

"Have you yourself seen this angel, Dr. Dee?"

"No, I think I told you that I myself cannot see."

Edward Talbot went up to the opsidian stone and stared into it.

"Iwill try what I can do," he said, "though this is not set as it should be on a table with the seals on the feet and the figures on the underside. But," he added with emphasis, "if my coining here is to be blessed and you and I are to work together, Sir, to the glory of God, surely there will be some sign given us."

John Dee bowed his head, trembling with hope and expectation.

"I will go into the oratory and pray," he said, but Mr. Talbot did not answer. He went on his knees before the small frame in which was set the crystal and he begged the astronomer to draw the drugget curtains closely across the windows and so to shut out the view of grey river, grey sky and windbitten banks.

Dr. Dee eagerly did this and brought a small cushion for the skryer to kneel on, which was refused.

Edward Talbot crossed his hands on his breast, closed his eyes and fell to mumbling prayers and entreaties. His voice was low and seemed shaken by a great passion, both of appeal and complaint, as if he struggled with one whom he both desired and loathed.

Dr. Dee thought that he had become at once unconscious and was in a trance, such as Barnabas Saul used to fall into before he saw his visions or the angels spoke through his lips. The figure of the young man, shadowy in his grey clothes and black cap among the shadows affected the astronomer with a certain sense of pathos. He felt immensely attracted towards this mysterious stranger, who had not yet told him anything of himself nor satisfied him as to his history or the extent of his knowledge.

He tried to keep his mind from such worldly matters, for he felt the moment to be holy and set apart from common things. He took his beads tightly in his hands and passed into the oratory, casting himself before the altar and endeavouring to shut from his mind all emotions save his intense desire to communicate with the angels of God.

He succeeded, as he often could succeed, in snatching away his spirit from his surroundings, so that he did, indeed, seem wrapped up in a cloudiness which was not without its shoots of glory. He scarcely knew where he was till he heard a faint cry which brought him to his feet and sent him hurrying into the outer room. And there he saw Edward Talbot stretched between the two shewstones, calling out like one muttering in his sleep.

John Dee knelt beside him and half lifted him up.

The skryer at once opened his pale eyes and smiled.

He had seen, he said, Uriel, the spirit of light, who had told him that these experiments were to be blessed, and that if implicit obedience were given to the spirits, great benefits and glories might result.

Tears of joy came into the astronomer's tired eyes. Before he took any heed of the skryer who had proved so overwhelmingly successful, he clasped his hands and gave thanks to God for thus acceding to his humble and earnest petition for light and wisdom.

Edward Talbot sat up and asked for a glass of water. He seemed much overcome by giddiness and faintness and his features were of an almost mortal pallor. The astronomer was about to comfort him with kind and grateful words, but the young man sprang up with a sound like a sob, and with a movement as if he were in a violent temper, hastened from the house.

During the whole of April Edward Talbot came secretly to Dr. Dee's house and conducted experiments in the little room above the workshop which was next to the oratory.

Every time he knelt before the shewstones the angels appeared and gave minute directions as to what was to be done to secure the revelations they would finally make.

Dr. Dee got down from his shelves the Liber Mysteriorum (Book of Mysteries) in which he had begun to note the results of the sittings with Barnabas Saul and some others. He still knew nothing of Edward Talbot, nor did he trouble to ask, for he was confident that the angels would not have chosen an unworthy medium.

But there were others in the establishment at Mortlake who were not so easily satisfied. Private as the sittings were kept, Roger Cook had jealously pried them out.

After a passionate protest to his master, which was met by a quiet rebuke, Roger Cook went to Jane Dee and asked her, brusquely, if she knew that the stranger, Edward Talbot, to whom she had taken such a dislike, was frequently and secretly visiting her husband?

"He comes up through the cottages and tenements, very often when it is twilight or very early in the morning before any one is astir, and the new assistant, Lewis, the doctor's son, lets him in, or else it is your husband himself who does not disdain this office."

"Are you certain of what you say?" asked Jane Dee, with an accent and look of great alarm.

"I have seen it with my own eyes. They try to call up spirits in the room beside the oratory, where Barnabas Saul used to practise. It is nothing better than black magic—necromancy, and the man is a rogue. What account has he given of himself? Who knows, what he is or where he has come from?" Roger Cook hurried along violently in his anger. "Here I have worked and toiled for fourteen years, to be entrusted with no secrets, and this stranger must come along and be taken into his confidence within a few hours!"

"Do you suppose he has seen any spirits?"

"Dr. Dee says that he has—Uriel, the Spirit of Light, and the Archangel Michael have appeared to him. One of them gave him a ring with a seal, which Dr. Dee showed me. Either," added Roger Cook furiously, "he lies and cheats or he is raising devils."

"This has been concealed from me," said Jane Dee. "Indeed, I know not what to do. I feared as much when that man first came here, I had a keen apprehension, even at the very look of him."

She glanced up at the blunt features of the man who had lived in this house so much longer than she had and who she both liked and trusted.

"You know, Roger Cook, how little power I have in this. Am I likely to be listened to? If this fellow be a rogue or an angel I shall not be able to dislodge him."

"He is no angel. I think he has an evil look. I would I had leave to find out something of his history—I would swear his name is not Talbot."

"But would my husband with his great learning be so easily deceived?"

"On the question of these psychic matters he is like a child," replied the astronomer's assistant bitterly. "He believes what he wishes to believe and sees what he wishes to see. And I will not deny," he added grudgingly, "this wretch has a strange power about him. I myself have felt it, even when I have passed him in the passage of an evening, or seen him in an early morning mounting the little wooden stairs to the garret."

At this Jane Dee felt a great and almost overwhelming uneasiness. Perhaps the man was a devil or an emissary from Hell sent to trap the soul of her husband in revenge for his daring adventures into occult knowledge.

"Oh, Roger Cook, I know not what to do. I am overburdened. You know our position—it is very bitter. We are much in debt and I can get no more credit. If Sir Francis Walsingham and Lady Warwick had not sent a few nobles yesterday, I do not know how I should have bought the food we must have nor paid the servants. We have sold almost all that we can sell."

"This fellow will prove costly," said Roger Cook, absorbed in the one grievance. "He says that the angels have ordered a table on which to set the globes. It is to be of sweet wood and have special seals. That will cost some money. And who knows what other wild expenditure he will not lead your husband into? Have you not noticed, Mrs. Dee," he added eagerly, "how, lately, he has refused to see almost everyone, even his oldest friends, what long hours he spends apart from you—how distracted he is when he is in your company, how little heed he gives to your complaints and demands? He will become completely absorbed in these dreadful studies and blast himself, you, and his family."

Jane Dee rose up with nervous haste.

"I thank you for what you have told me, Roger Cook. I will try to find out from my husband how far he is besotted with this fellow." And, being quick tempered and stung by a sense of injustice and her own grievances, Jane Dee ran at once to the laboratory, almost stumbling in her haste as she traversed the dusty passages, and panting and a little dishevelled in her shabby gown, confronted her husband with her angry grievance.

"Roger Cook tells me that this stranger—this Edward Talbot, comes frequently and secretly to the house, that that is where you are occupied all these hours when I am left alone, that is where our substance has been going. Why was all this concealed from me?" added the angry woman, on the verge of tears. "It was not because you are ashamed of what you do?"

The astronomer answered mildly. He was never affected by outbursts of feminine passion, and used to the moods and humours of his Jane, who he regarded with tenderness, reverence and loyalty.

"I kept my dealings with Mr. Edward Talbot secret so as not to disturb you, Jane. Because I thought if he were a cheat you need hear no more of it. But he has proved himself not to be, and I meant this very day to tell you of his comings here—to acquaint you with the progress of our studies."

Jane Dee heard these words with despair. She leant in the window place and began to weep violently, her husband, the while, comforting her with much affection and many gentle caresses.

But she was not appeased and soon launched out in a furious attack not only upon Mr. Edward Talbot, but on her husband himself, on the folly and wickedness of his experiments, on their present desperate straits, on their desperate lack of money and the whole galling situation, which fretted her to the bone. But her rage was like a sea spending itself on a rock. His patience was immovable, and at the end of her storm, he informed her that Mr. Edward Talbot would soon be taking up his residence in the room above the hall, where Barnabas Saul had lately lodged.

The table commanded by the angels was duly set up by the end of the month. It was called the Table of Practice and made of sweet wood and was about a yard high with four legs.

Talbot said the angels would reveal certain characters which were to be written with sacred sweet oil, such as was used in churches, on the sides. Each leg was to be set on a seal of wax, and a seal of the same pattern was to be set in the centre of the table (all to be made with clean, purified wax), nine inches across and an inch and a quarter thick, with a mystical figure below, which Dr. Dee found, something to his disappointment, to be no more than an ancient charm which had been in use for some years during the Middle Ages, which contained, within a cross, the initials of the Hebrew words, "Thou art great for ever, O Lord."

But Edward Talbot assured him that this had been especially commanded by the angels.

On the upper side of the seal was a table of forty-nine squares, built up with the seven names of God. Each name was to bring forth seven angels, and each letter of the angels' names was to bring forth seven daughters, and each daughter was to bring forth her daughter, and every daughter a son and every son his son.

Edward Talbot insisted that this seal was not to be looked upon without great reverence and devotion.

The Table of Practice was set upon a square of red changeable silk, and a red silk cover with tassels at the four corners to hang below the table was prepared to be laid over the seal.

Mr. Talbot then placed the crystal globe in its frame in the centre of the cover, resting on the seal beneath the silk. For his own use he ordered a green chair which was to be placed before the Table, while Dee, with the Book of Mysteries, had a desk moved into a corner of the room where he might sit and note what the spirits said.

Usually the spirits remained in the globe, but sometimes they stepped down into a dazzling beam of light and moved about the room. Sometimes they were not seen at all but only a voice was heard. The sittings usually began by a gold curtain appearing in the globe and ended by a black cloth being drawn across the crystal.

John Dee did not himself see the spirits, but only listened to the relation of their appearances and actions in words given him by Edward Talbot.

The sittings had been going on for a month and these elaborate and costly preparations had been carefully made and still the spirits had done nothing but promise that when all was complete they would make astounding revelations.

It was at this moment that Dr. Dee decided that Edward Talbot should reside in the house at Mortlake. The young man had still not revealed anything about himself, either of his life in the past or his hopes in the future. He was sullen when the conversation turned on any topic save that of his spiritual visitors, but the night that he was to take up his residence in the house at Mortlake he admitted that his name was not Talbot but Kelley, and that he would prefer in the future to be known as Edward Kelley.

It was a lovely evening in April when Edward Kelley arrived to take up openly his residence with Dr. Dee. He had no baggage nor furniture of any kind with him. He still wore his grey suit and cloak, his tight, black cap and broad-leaved hat in which he had first appeared more than six weeks ago in the panelled parlour on the night of the Aurora Borealis.

Jane Dee had not seen him since but she forced herself to meet him when he arrived and in a voice full of apprehension and fear she frankly told him her mind.

"Mr. Talbot, or Kelley, or whatever your name may be, I do here protest against your entry into my husband's house. I neither like your person nor your business and you shall get little comfort or fellowship from me."

The young man looked at her without resentment. His expression was rather one of wistful longing.

"These are vain words, Mrs. Dee, for the spirits have said I am to be tied in long companionship with your husband and it is very needful that we keep together, and it is most likely that we shall embark on many long and strange adventures. I therefore pray you, be patient."

He flashed his light look round the room and then added:

"As for worldly means, be not troubled, for a rich patron is even now on his way to relieve us of all anxiety. The spirits have told me so."

Jane Dee felt sick at heart and broken in body, as she always did after her violent outbursts of temper. She knew that she had lost both dignity and grace and entirely failed to achieve her purpose.

Her husband had been concerned and most kind, but it was quite clear that Edward Kelley, who she regarded as a base adventurer and a low impostor, was firmly established in her household.

She was further disturbed by fears that she had been wrong in her estimation of this strange young man; her conviction that he was a cheat began to waver wretchedly and she was tormented by doubts that she had misjudged him and perhaps offended the angels, his guardians. But the greatest of all her troubles was the fact that she herself had felt his peculiar influence. Although at first he had violently repelled her, she now was conscious of his magnetic fascination and when in his presence she could not altogether disbelieve in him. The glance in his pale eyes, the sound of his low voice with the peculiar accent that was unknown to her, stirred in her, most disturbingly, echoes of old dreams that she had believed were dead with childhood.

So she fell into a sullen acquiescence in the new order of things while Edward Kelley was closeted daily in the chamber fitted up for shying next the oratory. But still the angels dealt in nothing but promises, vague as those the Queen had offered throughout twenty years to her patient astrologer and mathematician.

The stranger came and went lightly in the house at Mortlake, causing little trouble in the establishment. He was enclosed in a deep reserve and full of self-confidence, and Jane Dee contrived to run her household on odd monies borrowed from friends or sent as gifts by compassionate patrons. All the assistants save Roger Cook had been dismissed. There was no need for their services since John Dee was now never in the laboratories.

This was a saving of expense, yet it filled Jane Dee with a certain dismay, for it was a sign that the natural order of their lives was being interrupted.

Roger Cook was sufficiently skilled in chemistry to continue work on his own, and he remained enclosed in the laboratories, coming out seldom, and then only to scowl or pace up and down the windy riverside gardens in a melancholy mood.

Then he went away suddenly, and was gone a week and more, and when he came back he seemed in a boisterous good humour and told Jane Dee that he had some fine news for her and what it was she should soon know. Then he asked that Dr. Dee and Edward Kelley might come down to supper that evening to celebrate his return.

It had recently been their custom to long overpass the meal hours and remain shut in the attic chamber until all the household were abed, even for the whole night, as far as Jane Dee knew, for she often did not see her husband for days together.