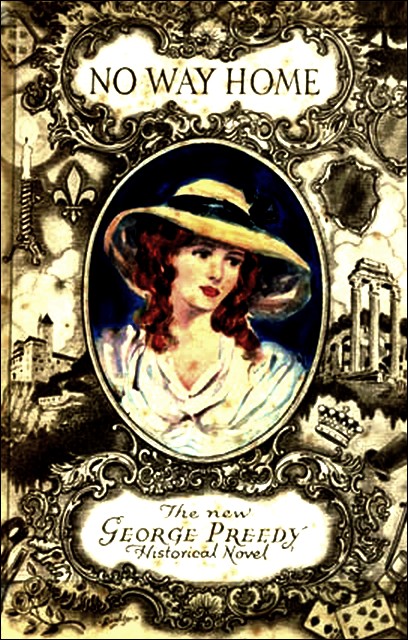

RGL e-Book Cover 2014©

RGL e-Book Cover 2014©

The crime was commonplace, save in the person murdered, but

it was supposed that there might be some tale behind it, but those who might

have spoken kept silence. "All life," the old play has it, "is but a

wandering to find home, and when we're gone we're there." This was quoted by

the philosophers who noted this affair for (said they) "there was no way home

but this for the victim of this midnight violence."

Memoirs of the Parish of St. James's, London.

—Corbie Pettigrew, London, 1830.

George R. Preedy.

There are no chapters in the paper book. The end of each section is indicated by five asterisks. These have been converted into numbered sections to aid in navigating through the ebook.

No Way Home, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1947

| PART 1 § 1 § 2 § 3 § 4 § 5 § 6 § 7 § 8 § 9 § 10 § 11 § 12 § 13 § 14 § 15 § 16 § 17 § 18 |

§ 19 § 20 § 21 PART 2 § 22 § 23 § 24 § 25 § 26 § 27 § 28 § 29 § 30 § 31 § 32 § 33 § 34 |

§ 35 § 36 § 37 § 38 § 39 § 40 § 41 § 42 § 43 § 44 § 45 § 46 § 47 § 48 § 49 § 50 § 51 § 52 § 53 § 53 |

THE TRAVELLER readily obtained lodgings for the night. The landlord asked to see his passport, which was British, in order, made out to Henry Campion, and stamped with the visas of the Duchies of Bavaria and Wurtemberg. He was a heavy, middle-aged man, wearing a light coat with capes, and he had come without a servant, in a small open carriage.

The Drei Mohren was the post house, and Mr. Cam pion paid his dues for hire and toll and ordered the carriage for the morning.

"It would be prudent, sir," suggested the host, civilly, "to engage a courier. The roads are well enough kept in Bavaria, and even through the Forest, but the confusions left by the late wars—" The Englishman put this advice aside with a quick movement of his gloved hand, as if it were matter he had heard often enough before, but Herr Kugler persisted in what he considered an essential warning.

"There have been accidents, disappearances; you must understand, sir, that whole tracts of the country are ruined."

"And you, that I am pressed for time; that I have an object, one object only, and that I conduct my affairs in my own way."

Herr Kugler bowed respectfully. No one travelling without a servant, and not speaking German, had stayed at his post house before. He continued, speaking English, he spoke a little of several languages, to impress on the traveller the dangers of a solitary journey, especially across the frontier, in Wurtemberg.

"Where are you going, sir?" he asked.

"I do not know," replied Mr. Campion abruptly. "You see, I am trying to find some one. I shall stay in Stuttgart, I suppose."

This remark caused the host some dismay.

"Ah, sir, you must realize! To be lost in Europe now is so easy—"

"Yes, so I have understood. But perhaps you can help me."

They stood in the empty, public parlour that was of the superior sort. The ancient house had been a nobleman's residence when the ancient city had been a free member of the Empire. Candles had been lit on the oak table; the windows stood open on the hot summer night and the lime trees in the square.

"Of course, sir." The landlord had seen letters from His Britannic Majesty's residents at Stuttgart and Munich with the passport Mr. Campion had shown. "But how strange if I could assist you! If you will, however, tell me the story—"

Mr. Campion's face became cruel. Herr Kugler swiftly felt that cruelty in the handsome, dark countenance, and the suffering of self inflicted torment. The traveller sat down carefully and drew off his gloves slowly, finger by finger.

"A rash and foolish person," he said, "decided to travel to Italy—"

"Italy!" exclaimed the landlord with relief. "Then you have a long way to go—Vienna to Venice—perhaps."

"You interrupt. Yes, I have a long way to go. This person, I have reason to believe, left Italy and Austria and came to Germany. It is true," he added with fierce weariness, "that I have followed many false clues."

"It is impossible that I should help you," said Herr Kugler firmly. "No one is here—has been here—save they who are accounted for."

"Naturally. Who is here now?"

This accent of authority frightened the landlord. His own secret and that of the stranger alike alarmed him. He wished now that he had said that the Drei Mohren was full, but he had thought it wiser to keep this formidable stranger under his close scrutiny.

"A lady occupies the first floor, sir. She has been resting here some days."

"A lady alone?"

"With a chamber woman, it is understood."

"Who is she, travelling now, unescorted, when, as you warn me, even the highways are dangerous? Dinkelsbuhl is an out of the way place for a lady to repose."

"It is Madame Daun, a most respectable widow. She travels from Stuttgart to Nuremberg on family matters—the selling of some property belonging to her late husband. She was indisposed on the way and rested here."

"A lady alone—she had no male companion?"

"No, indeed, sir."

"Well, I shall see her, I suppose."

"She keeps her chamber, sir, having a slight swelling of the throat."

"The maid, then?"

"Sir, are you of the Duke's police, or some courier of some foreign power that you make so many demands?" asked the host with dignity.

"I have power behind me. My errand is lawful. The Courts of Wurtemberg and Bavaria would support me."

"Then, sir, please be plain with me. Have you any business with Madame Daun, who is a most insignificant person whose papers are correct, above suspicion?"

"I do not think so," replied the Englishman. His fatigue seemed to increase suddenly and lie over him like a leaden cloak.

"Tell me one detail. What colour is this lady's hair?"

The landlord was astonished out of his carefully maintained composure.

"Madame Daun's hair, sir! It is the colour of that of most women in this country—pale brown—and over the temples, a little greyness."

"Send up my supper," ordered Mr. Campion abruptly, "to my chamber. I shall be gone early in the morning."

"Your luggage has been taken up. The room is spacious—on the second floor. Shall I conduct you there?" Relieved, but anxious not to show this, the landlord spoke with deference, as if wholly absorbed in his guest's comfort.

"No. I shall stay here awhile." The Englishman rose and went to the open window. The landlord withdrew, closing the door carefully on the unwelcome stranger who took no further notice of his surroundings.

The limes were in full bloom. The clusters of greenish-yellow flowers were visible in the light from the lamp in the square that fell faintly among the thick leaves.

The traveller suffered an intolerable loneliness, a bitter distaste for life. He was strong willed, determined, obstinate and inspired by a remorseless passion, but he was also fatigued by many disappointments, by a sense of futility and frustration.

The old city was like a prison. He had felt that as soon as he had driven into the gates that morning. He had disliked the Gothic pinnacles and towers of the churches, the medieval gables of the houses, the cobbled streets, even the stocking weavers going home from the work shops. It was all alien. He knew Europe only as battle fields. He had studied it only from military maps. He was now weary, with a deadly weariness, of road charts, bills of exchange, visas, frontier delays and questioning, arrivals and departures at inns and post houses, always alone, always among foreigners. If he heard of the whereabouts of any fellow countrymen he had to avoid them, for he travelled under a false name and on an errand that he could not reveal.

Herr Kugler was not the first to warn him of the perils of travelling without a servant. But his work was not to be shared, but something to be hidden from casual curiosity. Though wealthy and, therefore, used to excellent service, he made his solitary journeys with a fortitude not shaken, even now in the moment of gloom.

"It is only weariness," he whispered, for lately he had begun to talk to himself, though in the lowest of tones and when solitary. He was studious to keep a grave, aloof and taciturn manner when there was the slightest chance of his being observed. "Yes, and not yet—not even yet—being able to realize my misfortunes. My actions sometimes seem to me automatic. Still, it is not hopeless. Several times I have been nearly successful."

He glanced over his shoulder at the candle-lit parlour. "How many such rooms have I not stayed in for a day, a night, an hour—and how I detest all of them."

His dark features were pinched by suffering as he struggled to keep from his inner vision the images of the places where he had been happy. The boughs of the lime trees, gently stirred by the warm breeze before the window, appeared to him like walls. He picked up his beaver and gloves, still, amid his torment, a man of precise habits, and left the Drei Mohren. Once clear of the lime trees he turned to look at his last halting place.

It was a dignified mansion that had been refronted in a style of a hundred years ago. A façade of classic simplicity concealed the old irregular rooms, crooked passages and twisting stairs. A portico had been built over the large doorway, and the windows were set straightly. The shutters were not yet closed, and the traveller saw the gleam of the candles in the parlour he had just left. The windows of the first floor, the apartments of Madame Daun, were all lit. Their muslin curtains stirred to show the sparkles of a cut-glass chandelier, plain white walls and some pieces of austere furniture of Roman design. This glimpse into the pale chamber, so different from the dark, closed and miser able gabled buildings either side the inn, was like a glance into a theatre where the actors have not yet entered.

"Where did I make the mistake—or mistakes?" the Englishman whispered, staring up into the bright empty room. "Where did I take the wrong road, to the wrong city?"

He turned slowly across the public place. Songs were coming from the beer cellars as the flap doors opened and fell. The stranger was shut out of everything save his own narrow and terrible purpose.

He eased his stiff collar and passed his handkerchief over his face. There was no moon and the stars throbbed through a golden haze. The perfume of the lime blossoms was over sweet. He thought of water meadows, willow trees and smooth plots of grass sloping to the quiet river's edge, and knew they were nevermore to be his to enjoy. Slowly, several times losing his way in the twisting streets, he came out on the old fortifications and paced there, like a sentinel.

Herr Kugler went slowly upstairs and knocked on the door of Madame Daun's apartment. The elderly maid opened it and he asked if he might see the lady.

"You know—" the woman began a formal, a reproachful sentence, but the host silenced her by raising a heavy hand. "This is important and unexpected."

"About the police, the visas, the passports?" came the sharp query.

"Official business, yes."

The woman admitted him. The room was altered since he had let this suite, some weeks before, to Madame Daun. Shawls of pale yellow and white silk were draped over the chairs; a chased silver coffee service was set on a side table, some fine Persian mats were laid on the shining floor, a Venetian mirror surrounded by glass flowers scattered with gold flecks had been hung on the white wall. Majolica bowls of early flowers, pinks, roses, hyacinths, were set by the long horse hair couch of classic shape that Madame Daun had softened by cushions of blue, purple and pink embroideries.

She came from the inner door as the host entered, and seated herself on this couch. She wore a pale grey pelisse, and her head was swathed in white muslin, too thick for a veil and through which she could scarcely see.

"What did you say, what is it?" she asked in English. In that tongue the man replied, after the maid had withdrawn to the inner room.

"The most unexpected, the most vexatious incident," murmured the host, looking awkwardly on the ground, as if overwhelmed, not only by the lady's presence, but by the air of elegance she had given his severe room. "A traveller has arrived."

She interrupted nervously: "Is not that usual? There have been several travellers staying here since I came."

"But this gentleman, I regret he has made inquiries about you, Madame."

"Surely you misunderstood!" She sat upright, alert and speaking keenly.

"I express myself with difficulty. Directly, not about your ladyship, no, Madame, but he inquired if there was a lady staying here. He is searching for someone."

"He is French?"

"English—but it is understood that all manner of spies might be employed?"

"You know that I am French, though I speak English with you since you understand that better than my own language," murmured Madame Daun. "Yet, an English spy—it is possible. What did he ask?"

"The colour of your hair, Madame."

She was silent and put up a trembling hand to draw the muslin closer round her head.

"I replied, 'light brown, with a greyness on the temples,' pardon me, that was to give the impression of a middle-aged lady, instead of one so young. For the rest, I told the tale as you bade me."

"Thank you. I do not think that this stranger can concern me, but I shall remain close until he leaves. When is that?"

"To-morrow morning, early."

"Why then, it was hardly needful to tell me this!"

Herr Kugler hesitated painfully.

"My poor house—hardly suitable—the wiser action would be to ask our Duke for advice—I hardly expected the honour for so long."

"The Duke of Bavaria, as I told you, knows my circumstances—he considered that my privacy was assured here, while I negotiated the purchase of a secluded residence."

"I have been honoured by your confidence."

"The Duke will not forget your kindness," said the lady, softly. "As for the stranger, you are over anxious, for which I commend you. In a few hours he will have departed."

The words were spoken in a tone of gentle dismissal, yet the host stood his ground, though awkwardly.

"Perhaps you are tired of my presence?" she added, loosening the muslin from her face.

"It is a responsibility, Madame," he admitted reluctantly.

"I trusted you," she reminded him. "I await important letters. You alone know my secret. Even my chamber woman, Adriana, does not guess as much as I have told you. Soon I shall dismiss her and engage another stranger. You realize the life I lead, so lonely, so perilous." She untwisted the muslin from her head. He shifted his position uneasily, but he was obliged, by the fascination she had for him, to look at the face she had revealed. This was a countenance of dignity and delicacy, with an exquisitely arched nose, a full under lip and pale eyes under sweeping brows. Her loosely curled hair was hazel coloured and whitened by powder on the temples. Herr Kugler knew that he could not resist that sparkling, prominent glance. He murmured: "Your ladyship must stay as long as you desire."

"I shall not be here for many days more." She offered him her entrancing smile where pride was mingled with gratitude. ">My valet de place, Martin, has paid you all I owe?"

"Most scrupulously, Madame." Overcoming his nervousness by an effort of will, Herr Kugler added: "This Herr Martin, he is other than he seems?"

"He is my faithful servant."

"I understand—but his quality? If I might be trusted even further?"

"Martin is no more than my faithful servant. His devotion, as you must have observed, makes my existence possible. He, and his family, have always been in the service of my family."

The lady's tone was cold. Herr Kugler bowed and withdrew. He was not satisfied. As he descended the stairs slowly, with heavy head, he regretted the bias, the romantic temperament, the love of flattery, the awe of the reigning Duke, that had led him into the present situation. He did not doubt at least the main part of the sweet lady's tale; there had been the letter from His Highness, the prayer book with the illustrious signature, the marker, the pencil sketch; a hundred little incidents, all confirming the high flown, the impossible story. Above all there had been the lady's face. He had recognized the likeness at once. Yet some of the details of her case were vexatious. Martin, though he slept over the stables, seemed no ordinary servant and was very much in the confidence of his mistress, even to the handling of her money affairs. Certainly he was most respectful, most discreet, never over-stepping his place, but Herr Kugler, son of an innkeeper and himself in that business all his life, thought that he knew human beings pretty well, and he was dubious about Martin. Yet he could not offer himself any theory that might explain the servant.

As for the lady, if she was not who she hinted she was, who was she? Herr Kugler's instinct refused to connect her with anything discreditable; besides, she was gaining nothing by her life of a recluse at the Drei Mohren, and every week Martin paid her expenses, without questioning the accounts, in golden carolin. It had occurred to the innkeeper that the lady might be afflicted by a derangement in her wits, but against that was her command of money, her sober behaviour, and the facts that the letter from the Duke had demanded special service and protection for her, and that there had been no hue and cry after her, unless indeed, the Englishman?

But no, that was clearly a coincidence. There were so many missing people, of all nationalities, in Europe now, and so many, doubtless, searching for them. And the Englishman, this Mr. Campion, had obviously not been pursuing a woman with light brown hair, even though the landlord had misled him about the lady's age, there he had not been deceived. "Yet I shall be relieved," reflected Herr Kugler, "when all of them have left Dinkelsbuhl."

A widower, he had no anxious woman in whom to confide his doubts and he regretted his faithful Louise. The servants had all accepted the "Madame Daun" story, but he believed he had caught them whispering and staring—furtively, of course—and he did not want them to suspect anything.

Mr. Campion came back to the inn late that evening. He was surprised to see the small glow of a pipe under the linden trees; a man must be standing there, at ease.

"Are you staying at the Drei Mohren?" he asked sharply.

The other, a dark figure with his hat pulled over his eyes, barely discernible in the shadows, muttered an apology in French, and disappeared in the darkness beyond the faint light of the public lamp.

The Englishman entered the hotel. Herr Kugler, as if waiting for him, was in the doorway of the public parlour.

"Who was that man under the trees outside?"

"I don't know, sir, indeed."

"A tall fellow, he spoke in French."

"Ah, that is Madame Daun's servant, he uses French as a polite language, as having been much in Paris, but he is, like Madame herself, an Austrian."

"You permit lackeys to lounge in front of the hotel, smoking?"

"It is understood," replied Herr Kugler uncomfortably, "that a certain liberty—a trusted valet de place—"

"It is little concern of mine," interrupted Mr. Campion, brusquely, "but I should not long reside in an establishment where such poor manners are permitted."

Herr Kugler suffered the rebuke in silence. His desire that the secretive lady should depart became stronger; romantic, even enthusiastic as he might be, his livelihood was with sober, every-day folk.

"I brushed against the fellow," said Mr. Campion haughtily, as he went upstairs. Outside the tall, classical door that led to Madame Daun's apartments he paused, then shrugged his shoulders, as if despising himself, and proceeded to the chamber allotted to him on the second floor.

Here, after Mr. Campion had finished his excellent supper, Herr Kugler presented himself, to the Englishman's annoyance.

"You want your account settled?" he asked, stiffly.

"No, your lordship mistakes the character of my house," replied Herr Kugler reproachfully. "I intrude on the affair of Madame Daun. I am a little troubled there. I thought it wiser to confide in your honour as a gentleman, than to make any secrecy."

"Indeed, and what affair is this of mine?"

"I understand the rebuke, sir. Please understand my difficulty. I have been made the recipient of a secret—a sad secret."

Mr. Campion seemed still to find this talk pompous, even impertinent.

"Then what right have you to chatter to me?" he demanded.

"Because I feel sure you are suspicious—perhaps in trouble yourself, sir," replied the innkeeper with desperate boldness, "and because I know this lady is not the person you look for. She has royal connections, need I say more?"

"I don't understand at all."

"An exile, sir, a fugitive from scenes of the utmost horror—bereaved, shocked, ill, in disguise and seclusion."

Mr. Campion eyed the talkative foreigner with indifference.

"This is no affair of mine, and you waste your trouble. I am searching for two people. A lady travelling alone is of no interest to me."

Herr Kugler bowed.

"I have my good name to think of. It could not be my wish for you to have any doubts as to guests of mine. I saw a letter from the Duke offering them protection—"

"Then, indeed she is no one whom I seek," interrupted Mr. Campion, contemptuously. "What have I to do with such?" His grey eyes shot a glance so cold and sulky at Herr Kugler that the innkeeper became precise and civilly remarked that the light carriage would be ready soon after breakfast on the following morning.

Left to himself, the Englishman paced the waxed boards, up and down before the handsome tester bed with the white, rose sprigged curtains, before the side table on which he had set out his travelling toilet case, on which stood the candles in brass sticks, before the window that gave on the topmost leaves of the linden trees, outlined, amber yellow, against the glow of the street lamp.

Without his cumbersome coat he showed as a fine man, tall and heavily built, with a broad chest, thick neck, and blunt features. His curly, dark brown hair was cut short and close whiskers accentuated his prominent cheek bones. His bearing was stiff and aristocratic; he had no gestures and few intonations in his speech. When he sighed, which was not infrequently, gusts of passion seemed to tear his breast.

At length his restlessness expended itself in the action that had become a nightly ritual with him. He paused by the candle light, seated himself, indifferently, on the dressing stool and drew from the inner pocket of his coat a crimson velvet case, worn by continual fingering and rubbing. He touched the spring and gazed, with a grim intensity of emotion, at a miniature that showed a young woman with two small children gathered affectionately in her arms. She wore a wide-brimmed Leghorn hat, with black ribbons, that shadowed her face, and a white muslin morning gown. The boy's blue coat contrasted prettily with the rose-coloured sash of his younger sister. It was a delicate and attractive, if slightly insipid, portrayal of a charming young mother, only a girl herself, with infants as dainty as wax dolls. Round the miniature, fitted neatly into the case, was a plait of shining hair, of a dark, yet brilliant, red colour.

Mr. Campion continued to stare at this simple miniature that was not skilful enough in the execution to be more than a pallid suggestion of the original, with eyes heavy with a concentration of passion. His mouth, usually stern, twitched into a grimace and his body became set in a sombre, hunched attitude, expressive of his desperate absorption in the thoughts stimulated by the trivial painting. These thoughts never left him during his waking hours and, transformed into fearful shapes, haunted his hideous dreams. But never did they reach such a pitch of agony as when he, unable to resist the nightly torment, gazed at the presentment of these three fair faces.

The unsnuffed candles flared, then guttered into what the gossips name winding sheets, but Mr. Campion took no heed of this uncertain light that cast his ragged shadow jumping on the wall behind him, and across the trim and empty bed.

Martin entered the hotel quietly and softly went upstairs to Madame Daun's apartment. He was a tall, well-made man whose face was covered by a taffeta mask. Herr Kugler and his staff had at first found this disguise unpleasant, but they had accepted the explanation that Martin was so frightfully disfigured by smallpox as to be intolerable to the eyes of his fastidious mistress. Though the romantic innkeeper had sometimes wondered if the silken plaster (as it seemed to be) did not conceal some famous countenance, yet he knew this speculation to be fantastic, and after some weeks in Dinkelsbuhl Martin's misfortune had been accepted. The eyes that looked through the holes were clear but it was impossible to trace the outline of the features beneath the rude modelling of the mask. Martin wore a plain brown livery, with a narrow black braid at the seams. His linen was expensive and he had silver buckles on his well-made shoes. His hair was black and hung lankly on to his broad shoulders.

Madame Daun herself answered his careful knock.

"How late you are!" she whispered nervously.

"I could not venture it before."

He entered the room cautiously. The curtains were drawn and also the candles extinguished save those four wax lights in a girandole on the marble and gilt console beneath the Venetian mirror. In this faint light Martin's mask seemed to be made of dirty plaster. His voice was slightly distorted by the rigid slit that served as mouthpiece.

"Tell me at once," she whispered, pulling her yellow silk shawl about her as she shivered on to the sofa. Her face was free of the muslin, and the extreme delicacy of her features was startling to the man who looked at her so shrewdly.

"You are ill." His voice was sunk but powerful, even in a whisper. "That would be the last misfortune—if you were to be ill."

"I shall not be ill."

"The woman—?" he interrupted, glancing at the inner door.

"You know she does not understand English. The Madame Daun story quiets her, with just a hint of the other. But she should not find you here so late."

"It is he," said Martin.

"O! Here—in this house!"

"Yes. I brushed against him, just now, under the linden trees. I was waiting for him to return. I saw him, clear enough, in the light of the public lamp. I had my hat pulled down. I moved away, then waited outside the window of the common parlour. He was talking to Kugler. Complaining of a lackey's insolence, I believe."

"Then he has no suspicion?" The lady spoke in extreme terror, and leaned forward on her knees as if without strength.

"None. I heard the talk among the servants. He has taken no trouble not to appear odd. He admitted he was searching for someone. Kugler was uneasy. He is a coward as well as a fool."

"Here! In this house! Sleeping beneath the same roof!"

"Not sleeping, I think. He looks desperate—yet strong, too."

"What can we do?"

"Nothing. I repeat, he has no doubts. Remember he is looking for both of us. You are travelling alone. He is not subtle enough to suspect a lackey. A very literal minded man. And he leaves early to-morrow morning."

"I do not feel as I could endure this night—indeed I do not. I shall declare I have a fever and make Adriana sit up with me."

"No. The woman probably knows too much already. You will do nothing unusual."

"You are right, as always. I shall be quiet, but how slowly the hours will pass!" She clasped her hands in an excess of fear, and her body trembled under the thin gown and shawl.

"Tell this woman the other story, or hint at it—show the ducal letter. You are quite a good actress, yet you cannot control yourself."

"My terror is too acute," she murmured. "To know that he is here!"

"It has taken him two years to find us, and now he does not know that he has done so." Martin, as if expecting to be surprised, had maintained a careful distance from the lady and stood, respectfully, well away from the sofa where she crouched.

"I wish I knew what clues he had. How he came here at all."

"May we never be as near again!"

"He must have leave of absence. Some special concession. But it would not be more than six months. He will have, soon, to return home."

The lady muffled the fine texture of the shawl into her face, as if to check cries or sobs.

Martin, alarmed at this emotion, left her, saying sternly: "I trust to your wits. We cannot stay here much longer. I shall tell you our plans to-morrow."

As soon as he had left the room, Madame Daun struck a bell on the console table. Adriana Beheim entered at once. Certain that she had been eavesdropping, the lady said that the devoted Martin had just warned her of danger.

"I may have been recognized and followed. This good fellow saw—someone—in Dinkelsbuhl—" her voice fell to silence.

They spoke in French, Adriana's tongue lagged in that speech. She strained her attention to understand what her mistress said. She appeared eager, yet troubled.

"If you would confide in me," she whispered. "Please, Madame, have faith in me."

"It is impossible. Know me only as Madame Daun. And above all be prudent."

"Never have I failed in the utmost discretion!"

"Yet recall that I engaged you merely from an agency in Vienna."

"But first, Madame, you asked if I was loyal to...to..."

"Do not mention the name!"

"But I must think of it—and of her—every time I see your face, Madame," replied the servant in great agitation. "Yet there is so much I do not understand."

"I intend," said the lady slowly, "to spend the rest of my life in seclusion. I shall take a remote mansion in some remote part of the Duchy or in Wurtemberg—the Duke protects me. I shall hire servants. Money I have in plenty. Martin will conduct my affairs for me. And so, withdrawn from the world, I shall hope not to live long."

"I did not engage for an existence like that," murmured the maid, half in caution, half in fear. "And, Madame, it has, this proposal, a tinge of madness."

"Many will say that I am mad. Perhaps I lost my wits when I was a prisoner. When—all my family—was—murdered."

Adriana crossed herself.

"Do not speak of it, pray, Madame."

"But I think of it, always. Consider my offer. You will be well paid. And I shall not live long."

Adriana inclined her head silently. She was getting old and her life had been without incident. She had no relations and no interests. She found this strange lady, who had partly confided in her so wild and improbable a tale, fascinating. Moreover, her mistress gave little trouble and paid well. It was easier to continue in this service than to seek another place. Yet she remained suspicious, reluctant to involve herself in possible mischief. Nor did the prospect of this lonely house, this sacrificed life, please her mind, romantic and curious, yet shrewd and superstitious.

"See me to bed now," said the lady with a sigh; she rose and the maid followed her into the bedroom. On the bed, covered with a silken shawl, was a fine chemise, embroidered on the sleeve with the letters "M.A." On the table by the bed was a prayer book bound in blue velvet powdered with fleur-de-lys. Madame Daun opened it and glanced at the pencil sketch, on the title page, of a woman whose uncommon face showed a definite likeness to her own fair countenance, and the flowing signature of a murdered Queen. Adriana glanced at it also, with awe and a little wonder.

"If you are devoted to the Imperial Family, Adriana, you could not choose but stay with me."

"Madame, I must consider—"

"Say no more, Adriana."

The lady went to her solitary repose, the maid to her modest closet. Herr Kugler put out the lamps and candles in the public rooms, after bolting the massive front door. Upstairs, Mr. Campion lay drowsed on his bed, in the dark, for the street lamp was out; the miniature, at which he had gazed so intensely, in his hand. In his room above the stable Martin took off his taffeta mask, with a mutter of relief, and lay down to sleep; he also was in the dark.

"The Englishman has gone early?" asked Martin. Herr Kugler replied that this was so, adding: "He would not take a servant. It is dangerous to travel alone."

"Where was he going?"

"To Stuttgart. He seemed sure that the person, or persons, he was looking for are in Wurtemberg. He has the help of the police, he declares."

"Ah, there are many strange guests in Europe now," remarked the valet-de-place. "Perhaps that of my mistress, seeking sanctuary, the strangest of all. I have had letters to-day," he showed a packet in his hand, "I believe we have found the house." And he mentioned a small schloss, or hunting box, situated in one of the loneliest parts of the Forest, known as Wilhelmsruhe and long abandoned.

"What a dismal habitation for a high-born lady!" exclaimed Herr Kugler.

"It is what she seeks, and what the Dukes suggest."

The innkeeper was silent before these august names. Martin proceeded upstairs with the letters that the post had brought that morning addressed to Madame Daun, at the Drei Mohren. Adriana passed him and came down, carrying on a gilt tray the Dresden china service used for her mistress's morning chocolate. As she gave this to a maid passing along the passage, she spoke to the innkeeper in their native tongue.

"I want you to help me about this Madame Daun—in bed as usual."

Herr Kugler raised a silencing hand and motioned her to the little room at the back of the public parlour that he used as an office.

"I was about to ask your help," he said, in some dismay. "I do not wish this interesting traveller to remain here."

"She does not wish to do so. Martin has told me—and so has she—that they intend to establish themselves in a lonely hunting lodge where she will live in utter seclusion. I am asked to share this retreat."

He glanced at her quickly. She shrugged and replied to the look: "Ah, you think that I am one to whom the world offers little! All the same, to shut oneself up like that—"

"The question is," put in Herr Kugler, "who is she?"

"You do not know?"

"Not precisely. I have heard the same stories as you have. There is really no reason to doubt them, save common-sense," sighed the innkeeper. "I confess that at first I was fascinated, baffled, overborne. Then the letter from the Duke—"

"Neither you nor I, my dear sir, is in a position to question His Highness about that letter. Are we simple folk being deceived?"

"For what end? Madame Daun is not a criminal. She has money, jewels, an excellent servant. She receives no one—she makes no attempt to turn her attractions to advantage."

"She is a well-bred lady, of course," agreed Adriana. "And the likeness is remarkable. Then there are also the souvenirs. Yet—" she paused and shrugged her shoulders.

"What are your suspicions?"

"I could hardly say—they are foreigners."

"They—but Martin is a servant."

"More a steward, at least. He knows all her affairs."

"Yes, yes, that is explained by his family's loyalty to her family. Besides, she speaks to me of friends who help her secretly, but who respect her wish for secrecy. After all," added Herr Kugler, as if endeavouring to convince himself, "considering her most horrible experiences, her dread of a loveless marriage to a man she dislikes—it is possible—"

"You do know more than I do," interrupted Adriana sharply. "She has never even hinted more than that she is a survivor of the terror in Paris where her family was murdered, and has some connection with royalty."

"She has told you more. I know it. Why did you refer to souvenirs and the likeness?" Herr Kugler spoke firmly, but kept his voice very low. "Let us be plain," he added. "This lady leads us to believe—without saying so in as many words—that she is that Princess known as 'The Orphan of the Temple,' daughter of your Austrian Queen, whose forthcoming marriage to her cousin was recently in the Gazette."

"Well, yes, she allowed me to think that, now you insist on putting it so plainly."

"Not so plainly—yet it is obvious that she claims royal blood—"

"—And a desire to die in hiding," interrupted Adriana. "I don't know what to do. I feel a devotion, a loyalty. She is easy to please, there is plenty of money."

"Who would supply that? The Bourbons are bankrupt, exiled in Switzerland."

"Some rich friends are helping her—perhaps English, she speaks English, she and Martin. I do not like his mask."

"You are fanciful. I've often known those marred by the small-pox wear them, like blind people wear a bandage over the eyes. I'm used to that. Yet I do feel there is a mystery, and I shall be pleased when they have left my house."

"She admits they search for her, her family that would be, they want this marriage."

"Who is left of her family?" asked Herr Kugler courteously. "I never concerned myself about these exiles, though I pity them. Yes, pity! It is impossible not to feel pity for this young lady."

The man and woman looked at one another doubtfully.

"A royal princess would be missed. I put that to her, she said that a friend had taken her place in the Swiss convent from which she escaped."

"It is fantastic!"

"Yes, there is certainly something fantastic about this lady. Whatever it may be, the Duke protects her, yet she is afraid of spies, of the police. Are you sure that Englishman was not looking for her?"

"I don't know, he has only gone as far as Stuttgart. From there he could watch her or have her watched."

These same words were being spoken by Martin to his mistress as they rode together under the avenues of limes planted on the ancient fortifications: "He has gone to Stuttgart, from there he could watch us." They sat their hired horses well, and Madame Daun, in a fashionable riding suit, showed nothing of the languor that had kept her confined to her elegant apartments in the Drei Mohren.

"Why should he do so?" she asked, wearily. "He certainly had no suspicions or he would not have left the posting house early this morning without even trying to see us."

"Yet I am not satisfied," replied Martin. "He has much help, the police, the two ducal courts—we have but our wits—the English residents, probably, wherever he goes."

"His errand is hardly one that he could confide to the police."

"He will have every assistance," answered Martin, impatiently. "The Regent himself must have granted him leave of absence for this special purpose."

"Do not speak of it, pray!"

"I must, at least, think of it. We cannot stay in the Drei Mohren. I shall take that Wilhelmsruhe house, a hunting lodge, not for some time used. It will suit us very well."

"For how long?" she asked, fearfully.

"I do not know. We must play these parts until we can shake him off. Remember what is on that."

"Cannot we fly, at once? To Austria—to Italy?"

"That would be to attract attention. We must go to earth."

She glanced in terror at his rude taffeta mask, it was only by his voice she could guess at his mood. The lovely day lay heavily upon her as, with the tone of a master, he bade her ride ahead, while he fell into a servant's place behind her as they returned to the town of Dinkelsbuhl.

Without provoking any comment, Mr. Henry Campion lodged at the modest post house, Blaue Engel, in Stuttgart, having crossed the frontier from Bavaria without any difficulty, owing to his papers being of a kind acceptable to both the Duke of Bavaria and the Duke of Wurtemberg. He soon forgot the lady staying at the inn under the name of Madame Daun. He had stayed at so many inns during his recent rapid journeying, and inquired into the identities of so many fellow travellers. He did not expect to find her alone, and for that reason had taken but little interest in the lady living on the first floor of the Drei Mohren. Therefore, he, who had left such alarm and speculation behind him, was obsessed by his own sorrows and furies and gave no thought to the tall man who had brushed against him under the linden trees, nor to that pale room he had seen bright in the summer darkness, behind the open shutters of the lady's chamber.

He had come to an end of his clues. Such reports as had been secretly and lavishly furnished to him he had exhausted. All had proved false and had led him astray from main roads. In six months of hard riding and driving he had zigzagged across Europe, often retracing his steps. It had been like wandering in a maze. War, too, had overturned the usual conveniences and made everything tedious. Many villages were deserted, many chateaux closed, hunting boxes and summer residences abandoned, parks overgrown, the posts were disorganized, the countryside often had a ruined look. It was common to see maimed and diseased people. Herr Kugler had been wise to warn him of the dangers of travelling alone through the dense forests where the rambling walls and stern towers of ancient castles certainly harboured thieves and vagabonds. But he had not been molested. He went well armed and was prudent, he had, also, the fanatic's faith in his destiny that kept him from any concern as to his own safety.

Now, in Stuttgart, he felt himself lost in the maze, as if the entire design enclosed him, twist on twist, and to move would be only to wander senselessly until he died of an agony of fatigue.

He walked along the Grabenstrasse, past the new palace still being built, to the old palace, approached by an avenue of plane trees. The heavy, formidable royal residence, appearing like a fortress of some distant period, partly deserted, partly used as offices, attracted as much of his attention as he had to give to anything. He turned into the courtyard, then into that beyond, and noticed that the ancient chapel was being used as an apothecary's shop.

In his loneliness, his idleness, the intense concentration of his purpose, he moved like a man mechanically propelled, up to the counter on which were wooden bowls of poppy heads, a pair of shining scales and bottles of Bohemian glass, deep blue and a clear crimson, cut on white.

The place smelt pleasantly of herbs and essences; shelves at the back held Delft jars of drugs. The apothecary's assistant was weighing out cloves, cinnamon and bay leaves, and looked up sharply as the foreigner entered. The apothecary was attached to the court and visited only by the better sort. Mr. Campion's self absorption gave him an air of confidence, so that he passed as one well answered for by the great.

"I want," he said, "an anodyne. I do not sleep very well."

The young man shook his head. He did not understand English. Mr. Campion roused himself and repeated his demand in German.

"The name of your physician, sir?" asked the other.

"I have none."

"Then I cannot supply you with anything save a very simple powder—to ease the head or the heart."

The Englishman tapped his fingers on the counter.

"It was an impulse on which I spoke. Naturally, travelling incessantly one becomes fatigued."

"You are credited to the English Ministry?" asked the apothecary's assistant.

"No. But my papers are in good order and I have protection in high places."

"I do not doubt it, sir," replied the chemist sincerely, for the stranger had a figure and air of authority and distinction. "You were recommended here? We have essences, perfumes, soaps, ointments—"

"I shall make some purchases. Let them be what you will." Mr. Campion seated himself on the high-polished stool by the counter. "I am tired. Pray give me the name of some doctor of medicine."

"Dr. Raab of the Postplatz attends most of the foreigners; he speaks several languages. But, sir, you should learn this at the English Residency—"

"I came here by chance," interrupted Mr. Campion. "A curious place in which to find a chemist's shop."

"A magnificent new palace is being built," replied the Wurtemberger with pride, "and this, the ancient Hofburg, is now used as offices. This was the chapel."

"A blasphemy, as I think."

"Sir, you will find, all over South Germany, old chapels, churches and convents now used as shops, barracks and lunatic asylums."

The youth had turned to the back of the long room where trestles, board tables and chairs stood in front of shelves and cupboards.

Mr. Campion rested his arms on the counter and took his face in his hands. He felt giddy and grateful for this respite from fatigue in this shadowed, pungently scented place. His quest was so near hopeless that he might, he thought, as well begin it here as in any other place.

The apprentice returned with a goblet of pale green foaming liquid that he promised would remove the pains of exhaustion, and, after drinking it, Mr. Campion did feel soothed.

The young man continued with his task of weighing and crushing in a mortar aromatic herbs, that he then poured, by a silver funnel, into jars of opaque jasper.

"There is a good deal to see in Stuttgart," he gossiped. "Though it is termed an idle city, having no trade, nothing but the court, the residences and the barracks. But the Stifskirche, just round the corner, has majestic royal monuments in the choir and an organ you can boast of. In the Hofkellerei you can purchase very fine wine, and in the Muns and Medaillen Cabinet are some remarkable coins and gems. In the palace gardens are orange trees three hundred years old—" he held up a small phial of thick milky blue glass, "here is some essence or attar extracted from them. I perceive you are not listening, sir."

"No. I am not sure why I came here. Yours is a pleasant city, and the country about like a park or garden. But I am lost. I am searching for someone—for two people."

"Ah, with the war just over, and another threatened, there are so many lost."

"Pray do not repeat that. I hear it from everyone. I must do my utmost in the time allotted to me. I have help. But I must rely on myself. Do they say in Stuttgart," he added abruptly, "that there will be another war soon?"

"Indeed, yes, sir, that is all the talk, of ill omen and foreboding, and we scarcely able to scrape a living yet from the ruins of the last confusion."

"I hear that also, everywhere. If war comes again my time in Europe is shorter still. I do not know where to begin. As well here as anywhere!" he gave a disagreeable laugh. "I suppose you or your master know all the strangers who come to Stuttgart? I thought I had traced them, after so many tedious miles, to Heilbronn but they, she, had left that valley. Where had she gone? Into Swabia, Franconia—I had many reports. I went here, there, turning back more than once." He checked himself. "Why do I tell you all this? I fall into the weak habit of talking to myself."

"You search, sir, for a lady, travelling alone?" asked the young man, doubtfully.

"No, no, she would be well attended. She is English, eccentric, and using an assumed name. She wintered in Italy for her health, two winters, or in Switzerland—her lungs, as I understand. In brief she has inherited a swinging fortune, an estate in Hampshire, you understand, with responsibilities. I represent her lawyer."

The apothecary's assistant thought this story, told in halting German, incorrectly used, odd and not in accordance with the foreigner's appearance that was in nothing that of a legal or business man, nor was his manner, of hardly suffered passion, that of one engaged in merely mercenary or routine work.

"It must be a troublesome journey, sir. Has the lady left no post or agent's or banker's address?"

"None—eccentric, I told you, and wishful to lose herself."

"She must be well supplied with money. Everything is costly now."

"Yes, she must," replied Mr. Campion, grimly. "I don't understand that—I mean I suppose she is using all her resources."

"But who sends her money?" asked the apothecary's assistant, putting the heavy gilded stoppers into the jars of crushed herbs. "You could, sir, surely, being a lawyer, have found that out in England."

"I did," interrupted Mr. Campion in a hard, angry tone. "She had left the address given me, before I reached it—communication with England is much delayed. I have, therefore, been travelling for several months."

"It must," remarked the young Wurtemberger, "be a considerable estate to warrant such expenses."

"More than an estate hangs on this quest. Tell me if you recall any talk or gossip. I warrant that little takes place here you do not know of."

"I have not heard of an Englishwoman recently in Stuttgart or near abouts, sir."

Mr. Campion sighed. "She is not able to speak any language but her own, save a little French. She could not pass for anyone save an Englishwoman." He paused, fingering the round goblet. The sunlight lay on the stone floor and Mr. Campion gazed at it, as if through it, at long vanished scenes that haunted him and would not be forgotten. "An Englishwoman," he repeated.

"And delicate?" the apothecary's assistant suggested. "Then, sir, this doctor Raab might assist you; as I said, all foreigners go to him."

Mr. Campion rose. As he had lied when he had said the lady was ill this suggestion did not interest him. He wished that he had not entered this strange place, with the vaulted roof above and cold flags beneath, and pungent perfumes. He put a coin on the table for his draught and asked for a parcel of pomades and soaps to be made up and sent to him, Mr. Henry Campion, at the Blaue Engel. He hesitated, looked round as if expecting one to enter the tall door and blot out the shaft of sunshine.

There was something so forlorn, yet so forceful, in his attitude, something that so strongly conveyed both courage and despair, that the young Wurtemberger, who was sympathetic towards this fine handsome man, and who had believed nothing of his story, said: "Perhaps, sir, I might help you. The clue is very slight but—"

Mr. Campion had turned instantly to face him.

"I am used to slight clues. I shall pay well, even for useless information."

"Well, sir, there was a gentleman, a foreigner, sent here by Dr. Raab—he had a touch of quinsy, such has been common, and the malaise from the grapes—too many vineyards round Stuttgart—"

—"and he was travelling with a lady?" Mr. Campion corrected himself. "As a courier, I mean."

"No. He was searching for a lady. I wondered if it might be the same lady. An Englishwoman, he said. He had traced her, or so he supposed, to the Bavarian frontiers."

The young man paused to consider the effect of his words on his sombre and interesting stranger. A flash that was almost like the light of hope spread over the heavy face as Mr. Campion wildly thought, "Has he left her? Is it possible? Has she left him?" The light faded and he said: "Where is this man? Is it possible to speak with him?"

"Why, I do not know, sir, or even if he is still in Stuttgart."

"Did you see him? What is he like in his person?"

"Very well, sir. He came here, when he was cured, and bought a quantity of perfumes. A foreigner, he might be English, his German had an accent."

"Like mine. I never spoke the language until recently. Yes, this man," Mr. Campion laboured out his clumsy lies, "might be the courier of this English lady."

"I do not know where he stayed. But Dr. Raab might tell you."

"Thank you. Send your account to my inn, I shall be there for some days, I suppose."

He left the shop, blinking in the sunlight, then returned asking for the physician's exact address. The young man gave this, then turned, checking over the items the stranger had ordered at random. "Whatever the truth is, he did not tell it to me."

Mr. Campion felt giddy in the sunlight; he made his way heavily to the physician's house in the Postplatz. Dr. Raab was at home and received him civilly. He was an elderly man with a smooth experienced manner. He might, from the appearance both of himself and his neat home, have had many activities besides that of medicine, but Mr. Campion took him on his face value, as a physician and nothing else. Moreover, the Englishman came straight to the point and, dropping all pretence at concern for his own health, related the story the apothecary's assistant had told him.

"Certainly I recall the young man; in this quiet old city every new face is noticed. He was staying at Bode's and may be there now. He inquired about a lady. Rather remarkable that there should be such a lost lady, a foreign lady, travelling in Europe in these tedious times."

Mr. Campion longed to put the queries he had posed to Herr Kugler, but could not bring himself to do so. What had been possible with an innkeeper was not possible with a man of education. He repeated his tale about the estate in Hampshire and stiffly took his leave, awkwardly placing a fee on the physician's bureau. He had the address, Bode's Hotel, of the other foreigner, who seemed to be on the same quest as himself and whose description he had not dared to ask. Before the lackey had opened the front door to him, Dr. Raab had appeared at the head of the stairs, his face smiling. "I do not know if I am betraying a confidence in telling you that this patient of mine, the last time I visited him at Bode's, told me that he had found the lady."

Mr. Campion could not answer. He bowed and went out heavily into the sunshine that lay with a warmth that seemed tangible on the Postplatz. The unacknowledged hope had vanished. She had not left him, not escaped, or if she had she had been recaptured soon and easily. Even, Mr. Campion asked himself fiercely, if they had parted, what difference would that have made, after two years? None, was the answer. Yet there had been that sparkle of hope. He sighed and walked slowly, often losing his way in the unfamiliar streets. When he found Bode's Hotel in the Schlossstrasse, he discovered it to be a superior inn, with a fine frontage, and well kept. There were handsome carriages before the door and liveried valets in the passage.

He asked for Signor Petronio Miola, the name that Dr. Raab had given him as the nom de voyage of the foreigner who might have been English. Mr. Campion, who, because of his limited knowledge of languages, had not ventured to change his nationality, thought that the man whom he sought might very well have done so. "One of his sly, crafty tricks. Yes, he would be clever at any kind of mummery; he knows Europe well, too."

Then Mr. Campion reflected that he had come to Bode's on an impulse, almost stupidly, searching out his enemy face to face, in public, without having thought out what his action would be. He had not intended this, but rather to take them unaware, to spy on them unperceived, to make himself and his purpose known carefully, and by degrees.

Now a moment was possibly on him that he had long and passionately waited for, and he felt unprepared, even sick and nervous.

The valet returned to inform him the Signor Miola was about to leave Stuttgart, it was for him that one of the carriages waited, but that he could offer a few moments to the traveller who wished to speak to him on matters of importance.

Mr. Campion was too absorbed in his purpose to feel the sting to his pride that he would never, save for this one object, have endured. He had never asked favours or waited on others. His spirit was as unbending as his manners.

He was shown into a parlour on the first floor; amid the formal furniture lay strapped valises, and Mr. Campion felt a heightening of his continuous nausea at this constant travelling. The road—the inn—the passport—the visa. The fruitless correspondence, stale and dull, waiting at the posthouses. And again came the forbidden, but not to be denied, thought of lost days of peace and security, of a home with lawns sloping to the edge of the placid river, of the company of those whom he had cherished with a love and pride seldom expressed.

How well he knew these inn rooms! In how many of them had he passed restless nights! They hardly changed from one country to another. If one paid enough, one got good service and accommodation of an unvarying kind, and these continental hostelries provided both an exasperating sense of a vagabond continually changing existence, and a dull monotony. As usual, there was an inner door to the private room occupied by the luxurious traveller. Mr. Campion glanced jealously through this door that stood partly open, and saw, with a sick glance, the back of a man in a summer cloak, standing before a dressing table. The light was so cast that this figure was a mere outline of brownish grey, the hues in the shadow of both the travelling dress and the long, fastened back hair. It might have been the man for whom Mr. Campion searched. The woman also, might have been concealed in the second chamber. Mr. Campion paused to hear their voices. For himself, he could neither speak nor move, but stood rigid, his hat in his hand, his heavy face slightly distorted in a grimace of fatigue and emotion.

His suspense lasted no more than a second, and the man by the dressing table had heard him enter and turned. Even in the obscurity of cross lights and shadows Mr. Campion perceived he gazed at a stranger.

Relief at being spared the hideous climax that he so desperately sought, was instantly followed in Mr. Campion's mind by an intensifying of the dreadful frustration that accompanied him weary day, dreary night.

"I have disturbed you needlessly, sir," he said in English, his sad passion making him awkward, even discourteous in bearing.

The other man came into the parlour. He was young, comely and expensively dressed. His air was cheerful, gentle and aristocratic. He seemed entirely at his visitor's service, anxious to please and of a most sympathetic manner. But Mr. Campion regarded him with dislike as the cause of disappointment, humiliation and a surge of almost intolerable emotion.

"You are not English?" he asked abruptly.

"No. I am a native of Bologna. I speak your language however. I had an English tutor. Pray be seated."

"It is not worth while. You are not the man I seek. Dr. Raab was under a misapprehension, he thought you a fellow countryman of mine."

"If I had been, what would you have asked me?" Signor Miola spoke with a sweet courtesy that Mr. Campion unreasonably resented. Feeling, however, that he must make some excuse for his intrusion, he said: "I am searching for a lady—" Then the words died on his tongue, for he realized how often and to how many people he had repeated them.

"And Dr. Raab told you that I, also, made this search for a gentlewoman?"

"Yes, but now I see that your business can be none of mine."

"Pray be seated, sir. Do not let us part so suddenly. Share with me a bottle of sparkling Necker wine. I have found the gentlewoman I sought."

Partly out of curiosity, not wholly to be denied, partly out of a desire not to appear churlish, Mr. Campion took the red damask chair by the window that looked on to the busy Schlossstraat.

"She was an elderly Spaniard, a connection of mine by marriage, travelling with a chaplain, maids, a courier, a dwarf and spaniels. Her destination was Bad Willsbad, but apparently she changed her mind and went to one of the Brunnen in the Black Forest."

"Sir, this does not concern me."

"But one traveller may tell his tale to another?" The Bolognese pulled the bell. "My quest is rather amusing. My relative's son is in sudden need of money—a pressing bill, you understand—and I, having nothing better to do, undertook to be his ambassador. To-day I travel to Rippoldsau, in the valley of Schappau, where I learn she is."

In return for this frankly given explanation, Mr. Campion offered his dry and badly told tale of the missing heiress to the Hampshire estate.

Signor Miola was all gracious attention to this halting narrative.

"Naturally, everyone travels under a nom de voyage now, but a wealthy Englishwoman travelling alone—"

"Not alone. She would have an English courier with her." He could not save himself from adding: "Have you seen any such lady?"

"Very possibly." Signor Miola poured out the sparkling wine the valet had brought, into the green glasses. "As I was about to say, an Englishwoman, travelling alone, wealthy, keeping to the main roads, should be easily traced. I have been lately on the way between Nuremberg and Stuttgart and searching out of the way places. There are many foreigners at the Brunnen, even now; could you offer me a description?"

Signor Miola spoke fluently, his address was manly and ingratiating. Mr. Campion, whose large hand shook slightly on his glass, felt soothed and more inclined to give his confidence than he had felt since he had left London in the first rigours of his cold, almost despairing resolve.

Yet still he expressed himself with difficulty.

"She is young; of no great, or surprising beauty, you understand. A—well bred—Englishwoman. There is nothing uncommon in her person, save her hair. Red hair. And that hue is uncommon only in England. In the Scotch Lowlands it is not rare."

"I have seen such a lady," replied the other, readily. "But she was with her husband."

Mr. Campion set down his glass with meticulous care, but his strength rose to meet his need.

"Yes, she might be with her husband. She would be, I suppose. As representing her man of business, I know little of her affairs. I suppose she was ill and left in some medical care while her husband, who is a merchant, travelled alone. There would be a courier also—a modest equipage."

The Bolognese had been looking from the window while Mr. Campion forced out these words. Then he spoke indifferently. "A couple answering to that description was here a day or so ago. They lived quietly, but I got into conversation with them, as I like to speak English. The lady did not appear to be delicate."

"What manner of man was her companion?" Mr. Campion obliged himself to ask this odious question.

"About my own age and figure. A soldierly bearing, dark—for your country, at least. Conspicuous good looks. Yes, I think so." Signor Miola smiled as if sympathetically interested.

Mr. Campion tried to rise, but could not.

"The heat," he muttered, "and this incessant jolting over broken roads. I have attacks of giddiness."

"Dr. Raab is an excellent physician."

"I forgot," sighed the Englishman, "to tell him my case. I was so engrossed in finding you. I supposed," he added, more firmly, "that you were either the husband—or the courier of this lady."

He forced himself to rise, and stood holding on to the back of the red damask chair. He obliged himself to look into the pleasant light grey eyes of the Bolognese, who was smiling at him in a most agreeable manner. No one could have been more unlike the man he sought; strange that he had made that first mistake of thinking that there was a resemblance, strange, even allowing for the uncertain light of the shadowed inner room.

"Can you inform me," he asked carefully, "where this—these people, went?"

"Yes, to Donauschingen on the way to Schaffhausen—"

"In Switzerland?"

"Yes."

Mr. Campion restrained his impulse to follow at once the fugitives. Slow and easily deceived, he was yet well trained and constantly goading himself to be on the alert. He reminded himself that he must be cautious. Used to direct methods, he was exasperated by anything in the nature of a subterfuge. Even the fact that he bore what the Bolognese so casually termed a nom de voyage, irritated him, though he was aware that few people travelling in Europe now used their own names, for good or bad reasons. "Careful," he warned himself, "this Italian fellow is certainly a gentleman, but he may be a scoundrel or a practical jester, and it is possible he even desires to throw me off the scent." Aloud, he asked painfully, loathing the part he was playing, if his agreeable host could be certain of the destination of the English couple.

"They said it was Schaffhausen—I heard them instruct the German courier," smiled Signor Miola. "They seemed weary of Germany. Their name is Latymer."

"Oh, these false names! Their appearance? Excuse me that I trouble you, but I have already wasted so much time, and I have to return to England shortly."

"You expect a renewal of the war?"

"Maybe—why do you ask?" Mr. Campion was glad of a respite from the poignant purpose of this odious interview.

"I thought you might be a soldier—you have that air."

A slow colour spread over Mr. Campion's heavy face.

"I am a lawyer, sir, as I told you."

"Why yes, but, as you remarked, sir, these false names! Now how can I help you to identify the Latymers? The gentleman's handsome face was the most notable of their characteristics."

Mr. Campion turned from the window, then turned again like one blind with torment.

"No fop," added Signor Miola, "but a head of classic beauty. The lady? A high nose, prominent eyes, red hair, pale, she wore some Eastern shawls, very fine silk, yellow, white, she had a dressing case of green morocco, for she entrusted it to me to have repaired for her. They knew very little German."

Mr. Campion bowed his head in silence.

"And, if it helps you, the initials on the case, that she said she had possessed before her marriage, were L.W."

"Yes, these are the people," muttered Mr. Campion, with a ghastly look. "You heard her name, her Christian name, used perchance?"

"Yes. I noticed it, for it was odd to me at first. Letty—Lettice—our Letitia, I presume. She told me that the other letter stood for Winslow. So, my dear sir, if you are searching for Mrs. Letty Winslow she is certainly by now at Schaffhausen."

"That is her real name she toys with so. To hear it in this place! From a stranger's lips!" Mr. Campion grinned, sighed and stumbled on. "Truly I am confused with fatigue, this has been a long, a tedious business."

"One understands, perfectly. Perhaps I can help you further. I travel with my servant, who is a very intelligent fellow." Signor Miola stepped to the inner door and called: "Bonino!"

A lean, soft-footed man with quick eyes appeared, a small valise in his hand. His air of perfect detachment soothed even Mr. Campion's terrible agitation.

"Bonino," explained his master, smiling. "This gentleman is looking for the English people who were staying in Stuttgart, will you tell him their names and particulars of their appearance, and their destination."

The body servant, in rapidly spoken Italian and broken English, at once confirmed Signor Miola's story.

Mr. Campion had believed this from the first. Now he heard this second witness he felt he had satisfied all possible prudence and caution. He thanked the Bolognese in a formal and abstracted manner, hardly noticing to whom he spoke, picked up his hat and cane and went downstairs.

Signor Miola watched him from the window.

"Bonino, there is a man most easily gulled. I see him below making inquiries from the porters, he will certainly go at once to Schaffhausen."

"Sir, he appeared incapable of further travel—a man exhausted, consumed by emotion."

"But a very strong man, Bonino. Much what I expected to see. One might feel inclined to pity him."

"Certainly, sir, one pities him a great deal."

"Yet his intention is murder, Bonino."

The valet permitted himself the slightest shrug. "May I ask, sir, where we are going?"

"Into the Forest. See the arms are ready and primed. We must go alone."

"You have found them, sir?" Bonino's tone was regretful.

"Certainly I have. It was not so difficult. We must be off at once."

The servant ventured to step closer to his master; the fading sunlight, now full on him, showed him to be nearly a generation older than Signor Miola.

"If I could once more entreat, even on my knees, that you, my dear lord, abandon this—infatuation, that you return to the splendid life you had at the Villa Aria, at the Palazzo San Quirico. You are so missed—the ornament, the support of your family."

The Bolognese received these words, spoken with all the formality and grace of the Italian language, without the least offence. Indeed, he returned the servant's obvious affection with a loving glance.

"Indeed, I know your worth, Bonino. You have reason on your side."

"Reason, indeed I have, sir. This adventure is beneath you—you who have so much. Besides, I foresee disaster for you among the three of them. Indeed, sir," continued the valet desperately, "what worth or merit have they so to engross your attention?"

"Very little indeed, as I think, Bonino," agreed Signor Miola. "A most ordinary affair, save in a few details. The truth is that I was not so satisfied as you—as anyone supposed—in that splendid life of mine in Bologna. It was dry and hollow. One wearied of the pedantry, the intrigues, even of the artificial merriments."

"So one understands, signore, but this! What substitute is this—for anything?"

"You must return to Italy if you are wearied, Bonino. I shall go on alone until, one way or another, the little drama ends."

"You know that I cannot leave you, signore. You know that my letters, reports home keep your family satisfied."

"Yes, yes. You are very useful," smiled the young man. "You manage everything extremely well. I should find it difficult to travel incognito without you. There is no more to be said than that, Bonino. Take the valise down to the carriage and tell the postillion my destination is Wilhelmsruhe in the Forest, a former hunting box of some small pretensions near Rippoldsau—"

"Where your aunt is staying, sir?" asked the servant, wisely accepting defeat with a jest.

"So your English is better than I thought, you rascal. You not only overheard, but understood all my conversation!"

"How else could I have confirmed your story?"

"I gave you hints enough for that, Bonino. The Englishman is so dense, and so bewildered with passion that he never grasped the significance of your presence in the other room."

"Yet he was shrewd enough, signore, to probe you as to their appearance."

"A desperate kind of shrewdness, Bonino. He was forcing himself to be suspicious, against his native credulity. He has never done anything of this kind before—is rash enough to travel alone and to rely on court introductions and the police. Of course no one takes any interest in his case. He is put off everywhere with lies."

"It is certainly amazing, signore, that he accepted the tale you told him of your eccentric relation."

"Yes, but I am not inclined to laugh at him, Bonino. Now, be on your way. I shall follow."

Left alone, the young man stood thoughtfully, looking down into the street where other travellers arrived and departed as the post-coach put in to change horses. Mr. Campion had left the active scene, and was certainly by now on his way to Donauschingen, a twenty-six hour journey from Stuttgart, and the wretched man already broken by fatigue—

"For his part," mused Signor Miola, "a renewal of the war would be a lucky fortune for him, a chance of an honourable death."

Florio San Quirico, travelling under the name of Signor Miola, ascended the beautiful heights of the Kniebis in his own light carriage that he had brought with him from Italy. Bonino drove the hired horse, the best the post could offer, that took the steep incline without difficulty, while the heavier vehicles were obliged to have extra horses or oxen for the three hours climb. The traveller enjoyed the fair country, rich and lavish in the evening light, the wild hollows overhung by gigantic rocks, the stern round capped towers of feudal castles overhanging deep defiles. The windings of the valleys, the lovely forests in full foliage, showed in an extensive vista as the road rose to the summit of the Kniebis. The glowing lustre of the scene gave a purple bloom to the mountains, the vineyards in the valleys, the fading azure of the heaven.

The Bolognese was not, as was the English traveller, obsessed by an overmastering desire or emotion, though he also was on a quest it was one in which his mind, as well as his heart was concerned. For, more intelligent than Mr. Campion, his passions were more refined, more under control, and a considerable melancholy pervaded his nature. What he was doing was deliberate, well planned and carefully executed. It was, he knew, something in the nature of an indulged whim, an allowed fantasy. It had begun, possibly in boredom; it had more to do with sentiment than passion. He had no sleepless nights, no tormenting dreams, and he was sufficiently detached to be able to relish the incidents of his luxurious travelling.

The clumsy devices of the fugitives had never for long delayed him. Without the assistance that Mr. Campion employed, he, with the expert aid of his servant, had followed, a stage or so behind, easily, the couple whom he pursued. It had not taken him long to discover that a strange lady, supposed, in Stuttgart gossip, to be a member of the French Royal House, had taken the long deserted hunting box near Rippoldsau, once the property of the Grand Duke of Baden, and situated in a garden termed Solitude.

Bonino had been to Dinkelsbuhl and brought back reports; his master had acted on them, but at leisure, with none of the ruthless haste with which the Englishman hastened upon pursuit.

Signor Miola wondered now, searching his own heart, how much there was of caprice in this absenting of himself from his home, the duties of his station, the elaborate structure of his life, so well filled with intelligent activities. A shade of sadness came over his long, smooth comely face, as he watched the light withdraw from the landscape and the sky. He felt pity for the Englishman, respected him and wished him well out of his dreadful trouble—yet death alone would end that tragedy.

The well kept road turned sharply to the south and Bonino, skilful at all he undertook, drove cleverly down the steep descent that led to the lonely, little known valley of the Schappach, deep in the wildness of the forest. As the little carriage proceeded along the level road the thickly set trees shut out all sun, almost all light, from Florio San Quirico. He felt as enclosed as if he drove between high green walls.

The carriage drove past a Gothic church at which Florio San Quirico glanced with pleasure. His taste was gratified by these South German churches with the windows painted in yellow and blue, the stone pulpits with lime-wood canopies, the shrines with the black figure in the tinselled robes, sparkling with sequins and tinsel, with gems and gold, the offerings of rich pilgrims, glittering in starry crowns, and the votive tablets depicting frightful disasters by land and sea. Such churches had, to the polished Italian, a childlike candour, even a crudity, that was agreeable after the elegance of his native edifices, cunning designs in light and space.

He had seen the pilgrim churches on mountains with the winding avenues of chapels approaching them, and been moved by a faint, surprised reverence for what he had been led to believe were merely a dull superstition. He had watched the pilgrims, headed by priests, setting out from a humble village and had heard their rude, earnest hymns with more respect than he had listened to the brilliant music performed so beautifully in San Petronio.

Not himself romantic, Florio San Quirico liked to encourage the romantic mood to which he was as sensitive as he was to every gracious aspect of human nature, and he indulged this now as the carriage drew up before the most modest and obscure of the Brunnen of the Forest, Rippoldsau.

The establishment, the former hunting lodge of the Grand Duke of Baden, was a severe building, surrounded by a number of what appeared to be summer houses, but which in fact sheltered the fine cold mineral springs that the Badhaus offered to those in search of cures for skin diseases. The place appeared deserted, though the windows were open; in their shining panes the last light of the sun glinted red. At the sound of the carriage a dog barked and a man in a plain livery came round the side of the house, followed by an ostler.

Florio San Quirico savoured the prospect. He was skilful with the pencil, as he was skilful with the lute, and the scene pleased him in its lonely and melancholy beauty. The silent grey house, the gleaming windows, the background of huge oaks and massive pines dark against a paling sky, the two men advancing, almost doubtfully, as if they were surprised to see strangers, composed a picture that the young Bolognese could rapidly have touched into his sketch book.

He was amused to realize that he could be thus easily distracted from what he had tried to believe was an imperious purpose. Tried? Was that the key note of the episode? Was he forcing himself to a quest that had no true zest in it?

He sighed lightly and descended from the carriage.

"Are there rooms to be had for myself and my servants?" he asked with that agreeable courtesy that made him acceptable everywhere, yet left no doubt of his quality. The attendant of the Badhaus answered, yes, indeed; this place was little known, though the proprietor had made great improvements in it and the cold springs were excellent, but the season was nearly over.

"I do not suffer from any ill that you can cure," smiled Florio San Quirico. "I would like to repose here for a short while."

Bonino unstrapped the valise, and the ostler took the reins. The landlord appeared in the doorway to welcome this unexpected visitor to his establishment.

Florio San Quirico was given the best chamber in the house. It looked, by a tall window, on the Forest. The floor was tiled in dark red, the sparse furniture was of lime-wood; from the tester of the bed hung white linen curtains; the room had an ascetic air, as if it belonged to a recluse who meditated in loneliness. There was a shelf of books in gold tooled leather, with ties of pink floss silk hanging beneath the spines.

"Perhaps," thought the Bolognese, "some lonely student left them here."