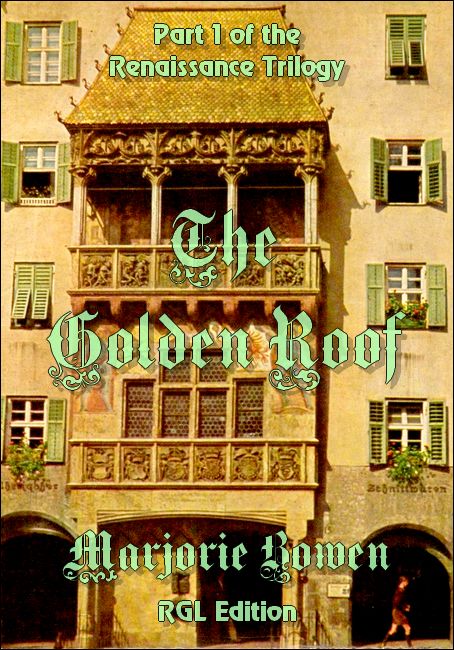

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Golden Roof (das goldene Dachl), Innsbruck

Based on a vintage Austrian postcard (ca. 1900)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Golden Roof (das goldene Dachl), Innsbruck

Based on a vintage Austrian postcard (ca. 1900)

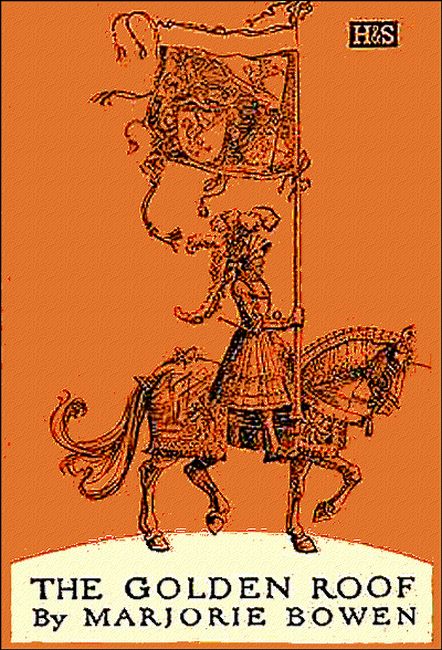

"The Golden Roof," Hodder & Stoughton Ltd., London, 1928

"The Golden Roof," Hodder & Stoughton Ltd., London, 1928

Uncertain, whether by the Winds convey'd,

On Real Seas to Real Shores he strayed;

Or by the Fables driv'n from Coast to Coast

In New Imaginary worlds was Lost.

—Aulius Tibullus, Elegy IV. Book I.

[This appears in the closing pages of the book, together with advertisements for other novels published by Hodder and Stoughton.]

The Golden Roof, an Historical Novel by Marjorie Bowen author of The Pagoda, The Countess Fanny, etc.

The title is taken from the Golden Roof (of copper tiles, gilded) on the Imperial Palace at Innsbrück, one of the few tangible memorials left of the greatness of Maximilian I of Hapsburg, 1459-1519, Holy Roman Emperor, who dreamed once to roof the whole world with the gold of his achievements. The characters in the tale are all historic, the Emperor himself, Ludovice Sforza, Louis XII of France, Catherine of Aragon, Henry VIII of England, Charles Egmont, Duke of Guelders, and the scene is the Tyrol, Vienna, Augsburg, Flanders, Guelders, and France. The love interest is provided by the love story of Maximilian himself with his first wife, Mary of Burgundy.

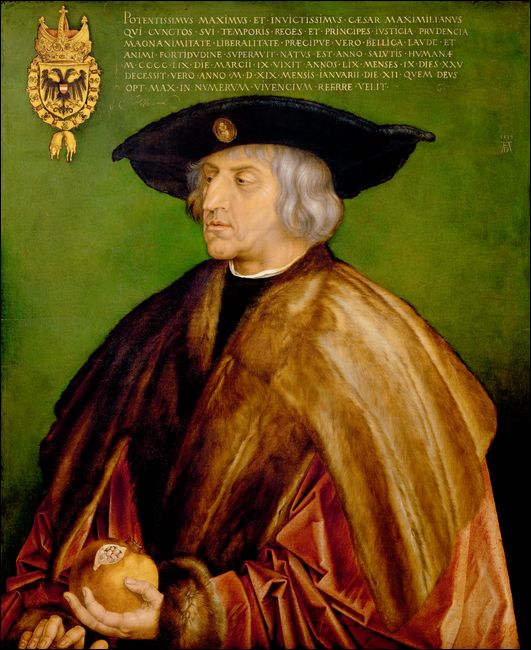

Maximilian I, 1519

A portrait by Albrecht Dürer

MAXIMILIAN I of Hapsburg, crowned King of the Romans and Emperor Elect of the Holy Roman Empire, "Maximilianus, divina favente dementia, Romanorum rex semper Augustus, etc.," as he styled himself, was descended from that House of Austria that achieved imperial honours in the person of Rudolph I, Count of Hapsburg (Emperor 1273-1291), who succeeded the doomed and splendid dynasty of the Hohenstaufen in those vague dominions which were supposed to include the kingdoms and glories enjoyed by the Roman Caesars, by Otto, by Constantine, and by Charlemagne.

Maximilian I was the most remarkable of this family which became so dominant in Europe, and with the rule of his grandson, Charles V, united under the double eagles as wide an Empire as the world was to know till the nineteenth century. Maximilian brought his house, though not either Germany or the Empire, to an extraordinary pitch of material prosperity; a series of brilliant marriages gave rise to the famous "tu felix, Austria, nube," and Maximilian, though constantly defeated and disappointed, left kingdoms to all his grandchildren, Charles, Emperor and King of Spain, Ferdinand Emperor, Eleanor Queen of Portugal, Mary Queen of Hungary; the Spanish Hapsburgs ruled the most important Latin kingdom till 1700; they intermarried with the successful Bourbons who pushed French supremacy as far as Europe would endure, and the "high mouth" of Mary of Burgundy can be seen in Louis XV.

The other branch of the family is not yet extinct though deposed from all power; on the abolition of that superb pretension, the Holy Roman Empire, in 1806, the Hapsburgs retained the Imperial title and named themselves Emperors of Austria; there is no other instance in history of one family retaining such a position for such a length of time, over seven hundred years; it is extraordinary that, except Maximilian I, Charles V and Maria Theresa, none of the Hapsburgs were conspicuous for either mental or moral qualities or any manner of talent.

The period of Maximilian I's life (1459-1519) covers the end of that epoch we call the Renascence, and the beginning of that epoch we call the Reformation; some of the names contemporary with this Emperor, who died the oldest of the then rulers of Europe are: Charles VIII, Louis XII, François I, Kings of France; Henry VII, Henry VIII, Kings of England; Ferdinand and Isabella, sovereigns of Aragon and Castile; Alexander VI; Julius II, Leo X, Popes; Cardinal Georges d'Amboise, Cardinal Wolsey, Cardinal Ximènes; Thomas Cromwell, statesman; Gaston de Foix, Bayard, Ludovico Sforza, Caesare Borgia, Pico della Merandola are a few of the other men whose names most frequently appear in chronicles of the reign of Maximilian I. Among men of genius were Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Hans Holbein and Albrecht Dürer; among the men expressing in writing aspects of their time were Machiavelli and Erasmus; among the men who influenced religious thought were Savonarola and Luther; Columbus had just discovered one new world, and the invention of printing had opened up another, the study of the ancient learning had resulted in a fresh humanism, in every direction was an expansion, an effort to throw off the old crudities, cruelties and ignorances of the feudal middle ages, to substitute for the brute force of the knight and unquestioned tyranny of the king, a rule of justice and reason that considered the rights of the trader and the peasant and welcomed the refining and ennobling effect of science, learning and art.

Maximilian I of Hapsburg was not in the forefront of this new movement; though in much he encouraged it, he remained in essentials the mediaeval patrician, a member of a narrow military caste, trained to fight and to rule. He has been called "the last of the knights"; this is perhaps partially true, for though there were many men of this type subsequent to Maximilian none of them were ever able to display their qualities on the elevation where Maximilian paraded so superbly.

If he hardly noticed the Renascence he was indifferent to the Reformation; a sincerely religious man, he could not fail to be disgusted by the corruptions of the Church of Rome and irritated by the Papacy which had to be reckoned with, not as a spiritual force or a mouthpiece of Heaven, but as a mighty temporal power and the opportunity of some ambitious, able and worldly Italian priest, supported by a Curia as venial, as clever, and as unscrupulous as any ruling body in Europe, but he was not moved in the direction of Martin Luther who was guiding the malcontents, and he died before anyone was forced to side either with Pope or heretic.

Among the humanists directly patronized by Maximilian were many men whose teachings had considerable influence in the formation of the German people; Jacob Wimpheling, Conrad Celtes, Sebastian Brant (whose Ship of Fools attracted almost as much interest as the writings of Erasmus), Conrad Peutinger, and Willibald Pirkheimer, the senator of Nüremburg, that beautiful city that could boast Hans Sachs and Albrecht Dürer, greatest of the artists who served Maximilian I.

Hans Burgmair, Leonard Beck and Freydal worked for the Emperor; these, like the scholars and humanists quoted above, and the coppersmiths like Peter Vischer, were employed in celebrating the glories of the House of Hapsburg.

Maximilian himself dictated the romantic tales illustrative of his own life, Weisskunig and Theuerdank which Burgmair and Freydal illustrated with wood engravings, now far more valuable and interesting than the letterpress they accompany, for Maximilian displays his own character but not his own history in these ingenuous fairy tales.

The Triumphzug and Triumphwagen are now given wholly to Burgmair though long attributed to Albrecht Dürer; a careful account of these wonderful wood engravings and reproductions of them were published for the Holbein Society in 1873.

There are four notable portraits of Maximilian I, that by Ambrogio de Predis, signed and dated 1502, profile, dark dress and cap, the order of the Golden Fleece; the chalk drawing by Albrecht Dürer of 1518; the mixed etching and engraving by Lucas van Leyden, dated 1520, but probably taken from life; and the rich and elegant portrait showing, as none of the others do, Maximilian I in imperial robes and diadem.

The kneeling statue of Maximilian on the cenotaph in the Hofkirche at Innsbrück, and his recurring figure in the bas-reliefs round the empty sarcophagus, were made after his death (1566) by the brothers Abel and Alexander Colin, but are obviously carefully constructed from contemporary sketches or busts; the likeness throughout is exact and true.

There is also a sumptuous figure of Maximilian in armour as Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, wearing the Black Knights' immense "panache" of peacocks' plumes and a crown, by Hans Burgmair.

Maximilian died at Wels, near Linz, the ancient capital of Upper Austria: his body was buried in the Church of St. George at Wiener Neustadt, his heart sent to die church at Bruges where Mary of Burgundy's lovely tomb is still standing by that of her father.

A number of Maximilian's own works have been reprinted in the Jahrbücher der kunsthistorischen Sammlungen etc.; the principal collections of his letters are: Correspondance de l'Empereur Maximilian 1-er et de Marguerite d'Autriche, Le Glay, Paris, 1839, Lettres indites de Maximilian I, etc., Bruxelles, 1851, 2 vols.; other letters and a mass of material relating to Maximilian are to be found in various books, archives, &c., the briefest list of which would be too long for this place. Among modern works on Maximilian I perhaps pride of place goes to Prof. Heinrich Ulmann's Kaiser Maximilian I auf urkundlicher Grundlage dargestellt, Stuttgart, 1884, 2 vols. In English there is not very much: Maximilian I is the subject of the Stanhope historical essay, 1901, by R. W. Seton Watson (Constable, 1902), and of one of Prof. Van Dyke's Renascence Portraits (Constable, 1906).

As far as the present writer is aware Maximilian has never figured in fiction.

The best authority for the affairs of Guelders is Geschiedenis van Guelderland, P. Nijhoff, var. ed. Arnhem. The above particulars are given as the bare bones of the subject treated in The Golden Roof; the writer's experience is that an historical novel is apt to cause some confusion and vexation to the reader who has no time nor inclination to discover which of the material presented to him is fact and which, fiction, and also that there are people who like to follow the characters of an historical novel into history itself—for them the above brief outline may be of some help. Maximilian I is not well known in England, nor are the facts relating to him easily accessible; most of the known details of his character and career have been incorporated in The Golden Roof where no historic truth or event, character or atmosphere has been wilfully or carelessly violated; the effort of the writer has not been to present a "capa e spada" story of romance and adventure, where an historical background is given to actions of fictitious personages (an excellent form of fiction), but to create out of the material of history itself, at once a narrative and a succession of pictures illustrating a certain period (1493-1519) and the characters of that period who lived in the Holy Roman Empire (Guelders, Innsbrück, Austria, Flanders) under the rule of a man who was one of the most attractive and interesting figures to ever wear the unwieldy diadem of the Empire of the West.

The author has, with some reluctance, revealed the reverse of the tapestry—to the rather rare reader who glances at prefaces—and only because experience has shown the confusions and misunderstandings that obscure attempts at historical novels—a difficult and lonely type of fiction.

M. B.

London, 1928.

Forget not yet The Tried intent

Of such a Truth as I have Meant:

My great Travail so gladly Spent,

Forget not yet!

Forget not yet when First began

The weary Life we know, since whan

The Suit, the Service none telle can

Forget not yet!

Forget not yet the great Assays

The cruel Wrong, the Scornful Ways,

The Painful Patience in Delay,

Forget not yet!

—Sir Thomas Wyat. (15th Century.)

THE flat gold pink brick front of the house was shaded by a closely set espalier of clipped lime trees.

It was high noon of a mid August day and the bees were busy in the kitchen garden behind the inn. There was no expectation of any guest, and the green shutters painted with hourglass-shaped white curtains were closed against the glare of the sun. But a traveller, stained with summer dust, had wearily arrived along the white lonely road, and now struck on the door. His knock echoed sharply in the drowsy stillness; a dog barked, and Rosina, setting curds in an out-house, was startled. She wiped her hands on her clean linen apron and hastened to the door. As she opened it she saw the stranger leaning against the trunk of one of the lime trees as if grateful for that gentle shade. Beyond this shelter of the espalier the landscape was vague with heat, swelling to a shimmering horizon sparkling with gold, and the upper air was pale with the fervent rays of the sun. The traveller, turning his head negligently, asked how many leagues it was to Roermonde?

"It is only about half a league," said Rosina, studying him curiously.

Although he was on foot he wore riding attire and spurs, and though he appeared to be of the meaner sort, a travelling merchant or burgher, he carried two weapons—a short sword and a dagger in his belt.

Realizing the presence of Rosina standing thoughtfully and dubiously in the doorway, he took off his flat, dusty cap.

"I cannot walk another half-league," he smiled, courteously. "This is an inn, I think; I may rest here, and eat, perhaps?"

A foreigner, thought Rosina, for his speech, his intonation and accent, were strange to her ear; but she understood what he meant.

"Of course. Come in," she answered, and stepped aside so that he could pass into the long cool passage.

"I have walked a long way," he remarked, "almost from Venlo."

"Yes, that is a long way," she admitted, surprised. "And have you lost your horse, sir, and your companions?"

"I have, indeed," he replied, with a grimace, half-disgust, half amusement. "We were attacked in a wood, and I do not know how many of my companions escaped with their skins, for it was as much as I could do to escape with mine. I have been robbed; but, never fear"—he touched a small wallet fastened to his belt—"that I have not sufficient left wherewith to pay my reckoning."

Rosina was used to these tales of misfortune. The roads were most unsafe in Guelders and violent robberies were of common occurrence. People generally travelled, she rebuked the foreigner, in cavalcades, in large numbers.

"There were a fair number of us," replied the stranger, "but we were attacked by a large band—robbers or soldiers, I do not know who they were."

"I expect they are the Duke of Guelders' people," said Rosina, "they attack everyone. Guelders, you know, is in a state of war, or revolt—I don't quite know what you would call it," she added, ingenuously, "there are always fights and frays, we often have wounded and robbed people coming here; it's very bad for trade," she finished, wisely. And then she asked the stranger if he would like some food set out at once.

But he replied that his greatest necessity was repose. He had been riding, he said, all night and most of the morning until the attack, and then he had been walking, wandering, trying to find his way to Roermonde.

"For this country is strange to me," he remarked, "and I have not been able to come upon a guide. Perhaps there is someone here who, when I have rested a little, can put me on my way?"

Rosina said yes, there were several who would go with him as far as the gates of Roermonde; "But unless you are in good favour with the Duke of Guelders," she added, "it is hardly wise for you to go there, for it is a great walled city full of soldiers."

The stranger easily replied that he knew this, but he had an audience with a high personage there which must be by no means neglected.

Rosina had brought him to an upper chamber, one which looked from the front of the house and directly on to the thick green of the clipped limes which filled the room with a goldish-green shade, for the sun was pouring strongly through the thick elegancy of the clustering leaves, as if it poured through transparent glass, and the shutters were but half closed.

"One may rest very well here," mused the stranger with a sigh of relief.

There was a wooden bed with a coarse coverlet, two wooden chairs, a small press, and a black crucifix hanging on a panelled wall.

"Is there anything that you would like?" asked Rosina, timidly. "We do not keep the shutters latched in this room, for the trees prevent the sun from being too fierce."

"No, there is nothing that I would like," replied the stranger courteously, "I am quite content. No, wait, I would have two ewers of pure water from a well, if you have a well, and six clean linen napkins."

The girl stared. "You could wash down below in the courtyard," she said. "My mistress would never give you six napkins. Even when we have had people of quality here we give them no more than one."

"Still, bring me six napkins and a ewer of water," insisted the stranger, gently, "and I shall do very well. Presently, I will come downstairs and see what you have in the way of food, and order a meal. Till then, leave me undisturbed, and, believe me, I can pay for what I ask."

Rosina, tall, heavy and fair, with her rough, red, work-stained hands folded in the apron, to which still clung the florid fragrance of the curds, turned again in the doorway.

"Well, you will not be richly served, it is not often that we have visitors in the daytime, only in the evening, and sometimes at mid-day for food; but lately, not anyone very much at all, as travelling has become so dangerous in Guelders that we live by the farm," she remarked, placidly, "though it does not matter very much," and then she left the room, and the stranger to his repose.

In her slow placid mind she turned over the question of the foreign guest as she filled two brown earthenware crocks with clear water from the well, and went to a large press in the cool room, and took out the extravagant luxury of six clean linen napkins, which had lain there for weeks, perfumed with sprigs of box pressed between their smooth folds. She thought it was very curious even for a wealthy man to make such a request. Water and clean linen in such profusion was truly remarkable to Rosina. She went slowly up the stairs, a ewer of water in each hand, and the napkins under her arm, and knocked at the door of the room occupied by the traveller. When she had knocked several times and there was no answer she cautiously opened the door and saw what she had expected, to see. He had flung himself on the bed and fallen asleep; he had not even taken off his spurs or the belt in which were the two weapons. Rosina put the rough pressed napkins on the chair in front of the window, then made another journey to the door and brought in the two crocks of water, and then stood undecided; presently, with a placid curiosity, turned to stare at the stranger, who lay carelessly flung on the rough quilt, his cap on the floor beside the bed.

He was a man not more than thirty-four years of age, of a considerable stature, at once slight and powerful, graceful and robust. His clothes were of a plain grey cloth, much stained with dust, and in places torn. His hair, tangled and dark with sweat on his brow, was the bright yellow colour Rosina was accustomed to see in the people of Guelders; it hung down on to his shoulders, which was new to the girl, for the Duke of Guelders had introduced the fashion of the Courts of Burgundy, the shaven head for gentlemen. This long hair added to the strange foreign appearance of the traveller in the eyes of Rosina. He had a remarkable face; the nose high, the complexion pale, the expression at once lively and amiable, even in his sleep he smiled. She noticed, in her slow quiet scrutiny, the beauty of the two weapons he wore in that plain belt, a deeply ornamented steel handle adorned the short dagger, and the sword was of uncommon and costly workmanship. The wallet to which he had called her notice was strapped to the sword-belt.

"I hope he has some money," thought Rosina, quietly, "for his own sake. It's ill travelling without a penny in your pouch."

Then she wondered why he had appeared so quiet and even agreeable when he had lost everything—baggage, his servants, and his companions, in one of those forays which made the journey to and fro Guelders excitement and peril to all travellers. "Why does he want to go to Roermonde," she thought, slowly, "and I wonder what he would like to eat. I expect there will be trouble to please him," and this was her tribute to his haughty and fastidious air which dominated even his amiable and charming aspect. Rosina thought that perhaps, despite his plain dress he was a great man, or at least in attendance on some great man, and she considered that she had better go and tell her parents, who were working in the fields, that a person of some consequence had come to the inn, which had remained empty for so many days. Then she took up the napkins again and folded them, three over each of the ewers of clear water, and decided that after all she could not go and send her parents, who were busily occupied gathering in the early apples, the late plums and pears from the orchard which sloped at the back of the house down to the river Roer, which wound through the lovely landscape towards Roermonde, whose high walls it washed, and there fell into the Maas. She went about her own duties in the cool dairy, setting her curds in the nets for cheeses, and putting underneath them the bowls into which the milky whey dropped. Then she considered what meal she should set before the stranger, and took some pots of preserve from a shelf in the kitchen, and set out the table in the dark dining-room (where the windows were still shuttered against the August blaze) with a white cloth, rough and fragrant of bay and box, and on this she placed a mug for beer, a loaf of bread, a cheese of her own making, and a dish of dried meat. While she was thus engaged, her mind and her fingers deep in her task, she was surprised by the sound of horsemen outside, and a little terror leapt into her placid mind. Everyone in Guelders lived in this terror—soldiers, robbers! Some quarrel of the great in which they most unwillingly would be involved. She paused to listen, and then peered through the round holes in the centre of the shutter, which let in a long ray of bright light; and there she saw, pausing in front of the espalier of lime trees, a group of four horsemen, armed and finely dressed, the horses fresh and impatient, and moving round and round although their riders strove to check them. These were men of her own province, she knew that at once by their appearance, and with a better heart she went and opened the door to them, standing in mute humility until they should choose to make their wishes known.

One of the riders dismounted at once, giving his rein to a companion.

"We can get food here?" he asked.

And Rosina replied patiently that some modest food she could provide, but scarcely a repast fit for such as he.

"We are hungry men," replied the other, "give us the best you can, and is there a stable for the horses?"

Rosina replied yes, there was some poor accommodation, and she walked out into the flecked and flickering shade of the lime trees, and pointed out the stables, which adjoined the farm at the back of the inn buildings. She had now perceived that two of the newcomers were gentlemen and two servants. It was these servants—soldiers they appeared to be—who led away the four horses, while the two gentlemen preceded Rosina into the inn, and walked at once into the dining-room where she had laid her poor but fragrant repast for the stranger who slept upstairs in the room behind the thick lime trees.

Perceiving the table set out, the younger of the two men exclaimed—"Ah, you have someone here?"

"There is a stranger upstairs," said Rosina, doubtfully, "a foreigner, I think. He is very fatigued. He has been plundered in the woods near Venlo this morning early, and has walked all the way from there, missing his path often enough."

"Plundered, eh?" repeated the elder of the two strangers, and then both of them, at the repetition of that word, laughed.

"We will share his meal; bring in what you have," said the younger man, in a tone of arrogant authority, "and tell him to come and eat with us. A stranger who has been plundered and robbed in Guelders is likely to be of some interest, eh?" and he nodded to his companion.

Rosina did not like either of the newcomers. Her interest and sympathy belonged wholly to the man upstairs.

The elder of these two was of a fierce and terrible appearance, at once gross and powerful, bloated and magnificent in bulk, in stature, his appointments handsome. The younger one had a peculiar face, long, smooth and cold in expression, as if his spirit retired in itself in an obstinate reserve. He wore a cloak, and a hat with a coif twisted round which he had not removed, and was partially armed on back and breast with worn, dinted, but well-polished steel. Both of them carried weapons at their belts.

Rosina thought them to be no better than those marauding bands of mercenaries or robbers who attacked all travellers on the roads of Guelders, and to whom that particular traveller, who lay above in the chamber behind the lime espalier, had fallen a victim.

"Would you not rather dine by yourselves?" she asked doubtfully; but they both sharply bid her fetch the stranger down; they spoke together, the austere tones of the younger, the coarse tones of the elder, mingled in one command.

ROSINA went heavily up the shallow stairs to the stranger's chamber. She had no thought of disobedience in her mind, but she did not much like her errand. She must, of course, do as the two gentlemen—captain-adventurers she called them to herself—had told her, but she hoped they meant no harm to the foreigner. She found him as she had left him, asleep on the poor quilt. He had not moved, and she looked at him with a slow vague stirring of compassion. Very likely they meant him ill, those two men below; they might even be members of the band that had attacked him, slain his companions, and stolen his baggage. But she did not dare to linger on her errand, she was too well schooled in implicit submission to her superiors. So, with a certain timidity mingled with kindness, she touched the sleeping man on the shoulder, grasped him more and more vigorously until she almost shook him, and at length he woke, and sat up.

"There are two men below," said Rosina heavily, "and they want you to share their meal. We have only the one room and table, save the kitchen, where their two servants will go."

The stranger stared at her as if he did not comprehend, as one waking from a deep sleep in a strange place will stare, wondering for a moment where he is and who speaks to him.

"I will come down," he answered, "after a second, though I would rather sleep."

"But this is really a command," remarked Rosina simply, "they are soldiers, noblemen, perhaps, and they always question and detain strangers—Guelders, as you know, is at war with many States, and you should not really be here; it is better that you go down," she added, anxiously, "and speak them fairly, than anger them by remaining here, so that perhaps they will fetch you. I have brought you water," nodding towards the two crocks and napkins, "and I will go down and tell them that you are coming."

The stranger smiled, as if all this were rather amusing than alarming.

"Perhaps these gentlemen are going to Roermonde," he suggested, "in which case they can accompany me."

He sprang off the bed, stretched himself and yawned, and, with a smile, told Rosina that he would come down immediately.

She left him, closing the door slowly. She was sorry to think that he was in danger; light-hearted as he might be about it, she knew that he, a foreigner, was certainly in peril from those two soldiers below. Perhaps he is a Hollander, she considered, or a German, and for all she knew of the matter, Guelders was at war with both Holland and Germany.

When she returned to the kitchen she found her mother there, her face hot and wet under the linen cap, her stout arm grasping a basket of purple plums, bloomed with blue. Rosina told her of her three guests. The old woman shrugged her shoulders as she set her load of fruit on the table.

"Nowadays one must be prepared for anything," she answered, "there is enough food in the house for five or six, and these people pay well."

Rosina explained that one of the guests had been attacked in the woods outside Venlo, and that maybe the other two were perhaps members of the band that had robbed him.

Again the old woman shrugged her thick shoulders. "Let them settle that between them, it is no business of ours. Do you hurry yourself, Rosina, and set food on the table. Nothing will anger them more than to keep them waiting for their meal. I have known farms laid waste and houses burnt down for no more cause than keeping gentlemen waiting for their food and drink. As for the other man it is no business of ours, if he has been robbed it was foolish of you to give him a room, Rosina; who knows that he can pay?"

"He has a wallet with him," replied the girl, "and I noticed a carbuncle ring on his hand, I think he is of quality," and while she spoke she skilfully piled dishes and trays with all the food in her store.

When she returned to the front room the two men had taken off their armour, which had become too hot in the August sun, and had piled it in a corner with their weapons and the younger had pulled out a packet of papers which he was reading earnestly with a frowning brow.

Rosina considered again, furtively and timidly, this man's appearance. He was slender, young and handsome—ten years younger, perhaps, than the stranger upstairs, but for all that Rosina was repelled by his appearance. His smooth long face, with the exact slight features, the light grey eyes, the shaven head so closely cropped that one could scarcely discern the colour of his hair, something more than cruel in the firm cut of the even lips—all this gave her a sensation of fear and hostility. As for his companion, the older man, at him she hardly dared look at all. He was silent and unoccupied, merely gazing blankly out of the window, from which he could see only the level boughs of the lime trees.

Rosina had a terrible impression of this second man; she was careful not to glance at him, she had seen sufficient of his person when she had admitted him with his companion. His great unwieldy bulk, the massiveness of his shoulders and arms, the power conveyed by his huge hands, his heavy head, the small flat nose, jutting brow, deep sunken eyes, and pendants of coarse yellow skin on either side of his thick-lipped mouth, conveyed at once to Rosina merciless ferocity and dominant authority; she feared and disliked the man; and as she left the room a fascination of terror caused her to glance back to observe the shaven head, which, coarse as it was, seemed too small for the body, and his powerful face outlined against the sunny square of the window. He was more, she thought, like a monster than a human being, and she wondered how the younger man, who had such an air of cold delicacy and arrogant dignity, could suffer such a companion. When she had placed all the food the inn afforded on the table, and while her mother was busy with the wants of the armed servants in the kitchen, she asked them in her dull timid way what more she could do for them, and told them that the meal was ready.

The elder man came immediately to the table and at once began to eat in a heavy gross fashion, seizing pie and meat and thrusting it into his mouth before it touched the plate. The younger man dealt more slowly and fastidiously with his food. He seemed to have little appetite, and broke a piece of bread on the cloth while he kept his cold light eyes turned on the papers he had brought from his wallet.

"Where is your stranger?" he demanded, negligently, "I have an interest in all the strangers who travel through Guelders."

"He asked for six napkins and two ewers of water," answered Rosina dully. "I think he must be a person of quality—he is washing off the dust of the day."

"Six napkins," repeated the younger man, "you have a traveller in this inn who asks for six napkins!"

"No less would content him," said Rosina, "I gave him all we had in the press."

"And why?" questioned the stranger, "since he has, as you say, been plundered in the woods by Venlo, he is not likely to be able to pay you for these luxuries."

Rosina hung her head stupidly. She did not wish to confess that she had a desire to please the other man at any cost; it had not been a question of money; compassion and admiration had made her fulfil a most unusual request; and while she stood there awkwardly twisting her apron in her hands, fearful to go without a dismissal, and yet fearful to offend by remaining, the other man himself entered the room.

His step was light, his air agreeable, he seemed in no way discomposed or alarmed. He had removed the dust from his face and his hands, and largely from his clothes. His long dark yellow hair, which was such a remarkable feature of his appearance, hung, wet with drops of the well water which Rosina had brought in the ewers, on to his candid forehead and broad shoulders.

The two men at the table glanced at him quickly, the elder wrinkled up his heavy features to stare. The newcomer returned this scrutiny with a careless and amiable salute, and took his place at the table.

"I find that, after all, I am hungry," he returned to Rosina with a smile, "and I am glad that you awakened me. If you had not I should probably have slept till this time to-morrow."

The younger of the other two men thrust his papers into his pockets and asked brusquely, "Who are you? We do not see many strangers in Guelders nowadays."

"I am a German," replied the other steadily, "travelling on business. I was—as I was warned I should be—robbed by a band of villains as I was passing through a wood near to Venlo, I think, though I am not familiar with this country."

"That is very likely," replied the young man, grimly. "And you lost, noble sir, I suppose, your baggage and your servants?"

"Both," replied the German, "my companions also," he added, indifferently; "two of them at least were slain, I saw that with my own eyes. But I," he continued with satisfaction, "disposed of at least four of the enemy, and should have done, indeed, better execution had they not shot my horse beneath me. I regret the horse more than friends, servants or baggage; he was a fine beast and excellently trained."

"You take your misfortune lightly," replied the young man coldly.

"I am used to misfortunes," smiled the German, "and have learnt to treat them in a philosophic manner."

"Are you now returning to your own country?"

"No," replied the foreigner, "I am bound for Roermonde."

At this the two others exchanged a quick suspicious glance.

"Why for Roermonde?"

"And why not?" asked the German, and poured out beer into his stone mug and drank indifferently.

The two men of Guelders continued to stare at the stranger with a scrutiny at once hostile and menacing. The pale, clear, cold eyes of the younger held as steady an antagonism as the brutal threatening look of the elder, but the German, as he had named himself, took no heed of either, and appeared little discomposed by their haughty and discourteous survey. He took his meal with elegancy, and yet with a certain relish, as one bred to good manners and yet kept long fasting. Whatever he might have thought of his companions he kept his counsel to himself, but now and then a smile touched his finely-shaped lips, which was more ironic than timid, and appeared to inflame the two men who so keenly regarded him.

"I have seen you before," remarked the younger, "when I was a child, I think. Was it," he added, harshly, "at the Court of Burgundy?"

And the German shrugged his shapely shoulders, and admitted, "it may have been at the Court of Burgundy."

"You are a Burgundian?" asked the other.

"Eh? I am a German, as I have already told you, and I am in Guelders on business."

"We," replied the stern young man, who seemed irritated by this, "have it as our duty to scrutinize and, if need be, to arrest travellers in Guelders who are here on business—of any kind."

"Why?" demanded the German, smoothly. "The Empire is at peace within itself, is it not? and Guelders is a part of the Empire."

He made this statement quietly, without any note of challenge.

But the young man replied, with cold ferocity, "No, no, Guelders is not a part of the Empire, and we are here to maintain that fact."

"Rebels, eh?" said the German, softly, "so I thought, so I have been informed. These forays and outrages such as I and my companions have been subject to to-day are fostered by Karel of Guelders and his soldiers."

"The whole country is in rebellion against tyranny," admitted the other young man, "for we do not admit an overlord," and his older, ferocious-looking companion, who was then pushing into his mouth large portions of pigeon pie, added in a choked voice, "We do not acknowledge the Emperor."

"Oh, treason," said the German, smilingly, "I thought as much. Karel of Guelders has set himself out to be a gadfly in the side of one engaged in great affairs, and it is a pest, good sirs, which must be plucked out, and crushed between finger and thumb."

"You're a bold fool to talk like that," replied the cold young man. "You are in the Duke of Guelders' country."

The German leant back in his vast wooden chair, and fastidiously wiped his fingers.

"Then, perhaps, you can help me to my destination," he smiled.

"You said it was Roermonde," growled the older man, picking the pigeon bones roughly with his crooked yellow teeth.

"Yes, it is to Roermonde, and, precisely, to the Kasteel van Meurs, which is, I think, not far from Roermonde. You can perhaps direct me there?" And he glanced courteously, and yet in a half mocking fashion from one to another of his hostile companions.

The name that he had mentioned, that of the Kasteel van Meurs, appeared to have a startling and ugly effect on both of these gentlemen. They glanced at each other in quick questioning fashion, and then at him, and the German remarked, with curiosity, the extraordinary eyes of the young man who was sitting at the other end of the short table, so pale as to appear nearly silver, and hard and bright as if they were of metal; set flat in the long smooth face these eyes gave the sinister effect that Rosina in her slow and heavy way had noticed, when she felt herself repelled by the young horseman.

"You wish to see the Graaf van Meurs?" exclaimed this young man, "and who are you? You will deliver your message to me and not to him."

"No," said the German indifferently, "my affair is frankly with the old Graaf Vincent. He is a very ancient man now, I think, and lives retired—more than eighty years old, is he not? and yet he will receive me, for I am come on matters concerning his grandson—the prisoner in Peronne."

At this name the young man gave a deep and half uttered sigh, and cast down his cold eyes, while his companion said harshly: "That is a name not mentioned in Guelders."

"I can believe that," replied the German, in a mocking tone. "Not mentioned these eight years for very shame in Guelders."

The young man, still keeping his eyes downcast, demanded steadily and haughtily: "Why do you use that word 'shame?' Speak me fairly and answer me honestly, for I have it in my power to prevent you fulfilling your business, whatever it may be."

The German made pellets of the bread crumbs and rolled them towards himself across the rough white cloth. "I know you have," he replied indifferently, "and I know you and who you are. My memory is better than yours, Karel van Egmond."

"You know me!" cried the young Duke, at once interested and exasperated.

"I certainly know you, and it was at the Court of Burgundy we met—ten years ago when you were no more than a youth."

"Who are you?"

"One who knows the story of Bernard van Meurs," replied the German, scornfully, and yet with a certain graceful humour that adorned all his words and actions.

THE German, though so completely in the power of the other two men, a stranger in the country, yet appeared master of the situation. He rose and strolled to the corner where their weapons, that had been so carelessly piled, were shining in the obscurity of the shadowed room, and from this vantage ground he watched them, as they sat at the table staring at him, in curiosity and antagonism. Karel van Egmont was most angry and suspicious though he had sufficient command of himself to betray neither of these emotions. More, he made a slight gesture with his slender right hand which rested on the table, as if he would command prudence to his friend who appeared to be about to break into coarse and furious language; this gesture was not lost on the long-haired German, who remarked, with a smile, "It is quite true that you saw me at the Burgundian Court. I am here on an errand of policy and I regret that I have been despoiled of my train and shall cut so mean a figure before Graaf Vincent."

"I am sorry that you have been attacked," replied Egmond, coldly and falsely. "It is no affair of mine."

"You are not able to guard these dominions which you prize so dearly?" asked the German, proudly. "That is what you must expect. Since you refuse the authority of the Emperor, your subjects, as you call them, refuse your authority."

"Not at all," replied Egmond, impatiently. "Do not let us waste time, my noble sir, on foolish and mincing words. Tell me what you are, and what is your embassy?"

"I am one deeply in the confidence of the Emperor," smiled the German, "and my embassy—I should not dignify it by so magnificent a name—is to old Graaf Vincent. It is about his grandson, who is a prisoner in Peronne."

"That affair can be no business of the Emperor," cried the Duke of Guelders, roughly. "I have had too much of this German and Burgundian meddling of late. Listen, sir; it is not a week ago since I caught two more fellows like you—German spies."

"I am not here to spy," returned the other, drily. "I have definitely told you my errand. I have also come to Guelders to see you, and to arrive at some accommodation with you on behalf of the Emperor as to this petty warfare that you wage against him, slily, and behind his back," added the German, "with secret, cunning treachery."

Here Karel's gross and monstrous companion broke in, with the harsh violent words he had with difficulty restrained.

"Emperor! Why do you keep using that word 'Emperor?' Who do you mean—Maximilian, Archduke of Austria?—he is no more though he called himself the King of the Romans."

"He is elected Emperor," said the German, slowly and agreeably, he seemed a man who very seldom lost his temper, "and he means to maintain that splendid pretension with full dignity."

At this both the others laughed coarsely.

"He has empty pockets and an empty head," cried the elder of the two. "I think your Maximilian of Hapsburg is a fool. If you are his man you may tell him so from me. Here in Guelders we pay no heed to him, nor to Albert of Saxony, his stadtholder."

"No," smiled the German, with irony, "and that is why you are in such a ruin of disorder. But, believe me, Maximilian does not intend to be a puppet Emperor—he means to rule well and wisely over all his dominions, and to make great conquests, one in the West, and one in the East, until his Empire spreads across Europe into Asia."

At these grandiose words both the men laughed again, with the ringing scornful laughter of practical people faced by the vapourings of a fool.

But the German took their laughter in good part and seemed, in his turn, to disdain them and their scorn.

"Fair words for an Emperor, perhaps, long ago," remarked Karel van Egmond, "but that was in the Golden Age. We in these modern days have no room or place for such visionaries. These are not the good old times, my friend, but the year 1493, and you will not find anywhere the simple folk who were glad to do homage to your Constantines, and Charlemagnes, and Ottos. Tell your master who wishes to revive these rusty glories that he is better employed in ruling his own duchy."

"A rebel, as I thought," remarked the German, softly, "an insolent rebel." But he spoke without malice and looked at Karel van Egmond with an interest that was almost kindly, and he thought, as Rosina had thought, in her slow diffident way, that this man of the great Guelders family, who called himself Duke of Guelders, and supported that claim by every device that his turbulent and crafty nature suggested, was of an appearance as repulsive as remarkable.

Karel had now removed his hat and coif; his close-shaven head showed of a fine compact form, exactly in proportion to his long narrow features. There was grace in the sharp line of nose and mouth, but the nostrils were too thin, the lips too deeply cut at the corner, and though those light eyes might be accounted a beauty in themselves, in their expression they were cold and unattractive. The German knew this prince to be bold and cunning, disillusioned and mocking, ambitious, restless and dangerous. If he had either passions or weaknesses they had not yet been made apparent to the public eye. Karel van Egmond possessed, however, two negative virtues which highly recommended him in the opinion of the other—he was not cruel, though perhaps not merciful, and he was not dissolute or licentious, but chaste in his' manners and severe in his private life. On both these points the stranger sympathized with him and applauded him, and he thought of these merits now as he looked at those hard, long, smooth features, the small compact head set so arrogantly on the wide shoulders. For he, this German gentleman, had a way of thinking always of the merits and attractions of those with whom he spoke, and it was to this quality of kindly courtesy and sympathetic consideration of others that he owed much of the fascination of his amiable personality.

"Come," he said now, smiling from one to the other of his companions and opponents (as he knew them to be), "we are ill met in an ill place, and I have no state with which to impress you, but, as you say, we live in modern times where we are all practical and reasonable, and disillusioned, no doubt. I have not come to Guelders to discuss dreams or chimeras or fairy tales, but to make substantial proposals for peace between the Duke of Guelders and the Emperor, and to open negotiations for the return of Graaf Bernard from Peronne."

Karel van Egmond's companion looked up from his plate, for he had again begun feeding grossly from the cold remnants of the meal, and demanded in an offensive tone what affair of the Emperor, as he called him, was Graaf Bernard?

"How many years since the battle of Bethune?" replied the German, quietly. "Eight years ago," he answered himself, with emphasis.

Karel van Egmond violently rose from the table: "You say," he remarked drily, "that you have come here as a reasonable man, to talk to reasonable men; you say you are sent from the Archduke of Austria, lately elected Emperor? Well, I do not wish to dispute either your credentials or his rank—though both seem flimsy enough—but you offer nothing but insolence."

"My credentials," smiled the German, "were lost in the attack in the woods; I have nothing with me but my purse in my pouch, and my wits in my head, and two good weapons by my side; and if a man have all those he need not regret anything else."

"You carry it flourishingly," responded Karel van Egmond insolently, and yet with an attempt to subdue his insolence. "I and my Maarshalk here are willing to listen to you, as reasonable and practical men, if as such you speak."

The German glanced at the Maarshalk, as Karel van Egmond had just named his hideous companion: "So you are Maarten van Rossem?"

"I am," snarled the heavy, gross soldier, grimly. "Make a point of remembering me."

"I have heard of you," smiled the German, with disdain.

Karel van Egmond was walking with a light and springing tread up and down the room.

"I can see," he remarked, speaking as if with a cold attempt at conciliation, "that you are a man of quality, and a person of sense and penetration, and I will listen to you, though lately there have been several gentry like yourself travelling in Guelders who pretended to have errands from the Court of Vienna."

"Yes," replied the German, "it was because these messengers did not return that I came myself. Where are they? In your prisons, Karel van Egmond?"

"Leave that," remarked the Duke, sharply, "before I decide how to treat you or your business tell me what affair it is of Maximilian of Hapsburg that Bernard van Meurs should return from Peronne?"

"Where a man has been for eight years," put in Maarten van Rossem sourly, "he may well stay for eighty, it seems to me. No one any longer worries about Graaf Bernard, and why does your Emperor, who is concerned with such vast designs, meddle in so trivial an affair as that of one prisoner, more or less, in the fortress of Peronne?"

Maarten van Rossem accompanied his sneering remark with a piercing look from his deep-sunk bloodshot eyes, and his thick lips fell back over his broken teeth in an ugly sneer.

The German moved aside with an instinctive gesture of repulsion, which all his good breeding could not avail to conceal. But Karel van Egmond broke in heavily—

"Do not talk so grossly of the affair, Maarten. I in my good time will see to the release from captivity of Bernard van Meurs.

"It is as well," remarked the German gentleman, with the first hostile note that had been heard in his voice, and with the first antagonistic glance that had darkened his handsome eyes, "that you should do so, Karel van Egmond. Who was captured at the battle of Bethune? Not he, but you; and he took your place in that fortress, out of courtly friendship, and chivalrous regard. And you were to release him from that imprisonment, to return to Peronne, or by some means free him...in a few months, you said, Karel van Egmond, and everyone of knightly estate and kindly honour has been watching to see you keep your Word. And that is eight years ago, and Graaf Bernard is still in Peronne."

The fierce young Duke of Guelders could not fail to be deeply moved and deeply affronted by these words, spoken so keenly and so fearlessly. His light cruel eyes glanced sideways at the speaker, he bit his thin underlip, and the veins in his neck swelled, but he had sufficient control not to break out into open anger.

"Eh," he answered in a voice of forced quietness; "you take the view of the outsiders. You do not know the inner meaning; I am worth everything to Guelders—it is not possible for me to abandon my country to release Graaf Bernard—he knows that and prefers to remain in captivity."

At this Maarten van Rossem laughed deeply and loudly, pushed his chair roughly back from the disordered table, and slapped his great thigh, laughing again.

"No man loves a prison," mused the German. He looked away from both of them, and out at the sunlight which lay flickering in bright lozenges of dazzling gold among the shadows cast by the espalier of limes. "Graaf Bernard," he added, "performed a brave, chivalrous and gracious act when he took your place in Peronne, and the Emperor, who admires such actions, is not minded that he should suffer any longer for it."

Maarten van Rossem stared at the speaker rudely, as if he resented these words. "Mark it, my good sir," growled the Maarshalk, "this is not a country where a man who has no followers to back him can offer plain and ugly truths. Let me tell you that no one for years has mentioned Graaf Bernard to Karel van Egmond."

"It is time then," answered the German, still smiling, "that someone did so, and that is why I have come from Maximilian of Austria to Roermonde—to Kasteel van Meurs, for the old Graaf Vincent still remembers Bernard, his grandson, and unless I do not make an error, there is another who does also remember him, and that is Gertrude van Bayer van Boppart, who should have been his wife."

"How in the name of the great devil do you know that?" roared Maarten van Rossem, as ferociously as if he had been personally insulted by these simple words; the young Duke of Guelders turned his cold smooth face with a look of bitter menace towards the speaker.

"Leave Guelders, and the affairs of Guelders," he commanded, shortly, "it will be to your safety to do so. I would not willingly openly affront Maximilian of Austria, and I wish to preserve courtesy towards his embassy."

"Yes, you were always sly and crafty," smiled the German; himself so bold and reckless. "Your rebellion has never been open, but subtle, and indirect. Eh, I know quite well that you are a dangerous man, Karel van Egmond."

"I do not think you are," grumbled Maarten van Rossem, "or you would not be here alone like this. What sort of a company did you bring with you that it was so easily scattered on the first attack?"

And so saying the Maarshalk seized a bone from the table and began to chew off the remaining portion of meat.

"It is a hot day," remarked the German, looking at this with extreme disgust: "shall we not walk outside in the garden where it is pleasant among the flowers, and the bees, and the fruit trees? This room oppresses me."

"People who live as I do," replied Karel van Egmond, shortly, "boot and saddle, hole and corner, touch and go, get used to common inns."

Rosina entered heavily and timidly. She carried a dish of fresh curds and a pot of cream which she placed on the table, looking apprehensively from one to another of the three gentlemen, all of whom appeared rather terrible in her eyes, but one of whom was a shining attraction, and this was the German stranger with the long yellow hair, who now stood in such an agreeable and good-humoured attitude by the window, outlined in his radiant fairness against the background of the sunny limes, while the others appeared disordered and stern; the Maarshalk, red, coarse, his forehead beaded with sweat—the Duke, pale, frigid, his attitude one of barely contained anger. The German alone had a courteous, easy, smiling word for Rosina; he thanked her for the curds and cream and asked if they might walk in the garden, to which the girl, with amazed humility, replied that all the house and farm were at their disposal.

"I will not walk in any garden," grumbled the Maarshalk, wiping his face with his sleeve, "it is my custom to sleep after meals."

Egmond placed on his shaven head the linen coif he wore under his steel hat, and said grimly and gloomily that he was at the stranger's disposition—"as well indoors as out," he remarked sourly. "I cannot think your views to be of great moment."

Yet he was plainly disturbed and eyed the German with hostility and apprehension.

When Rosina had gone, the German laughed and exclaimed gaily—"Why, do you not know me, Egmond—I am Maximilian of Hapsburg."

THE German gentleman, who had just announced himself as Maximilian of Hapsburg, had made his statement courteously and quietly, and yet not without a keen sense of its importance; for he was one who loved everything romantical and flourishing, and to him there was something splendid in being able thus to reveal his identity in this poor room of an inn in Guelders, and so put to a sudden shame and confusion his two companions who had taken him so lightly, and spoken of him with a certain disparagement.

Karel van Egmond coloured darkly all over his gloomy face, inwardly he named himself a fool for not having guessed, immediately, who it was to whom he spoke. He had sensed that the stranger possessed an uncommon quality, and had been teasing his memory as to whom he had been at the Burgundian Court where he, Karel, had been in his childhood and youth. But those days had grown dim with him since he had been absorbed with his good Guelders, and he could not recall one personality above the others. Now that Maximilian had made known himself, he did remember the tall athletic figure, with long dark yellow hair, the high aquiline nose, though in ten years Maximilian was changed, as no doubt he, Karel, was changed.

When the Emperor, as he had named himself, had first spoken his name, it had seemed to Karel van Egmond a gross absurdity to suppose that he, Maximilian of Hapsburg, should be in Guelders in disguise with a small escort and forced to put up at this lonely mean inn; then he instantly recollected Maximilian's character was reputed at once extravagant and unstable, and that his action was in keeping with extravagance and unstability; he was indeed a man to undertake just such a venture light-heartedly and with no fear of the consequences. So Egmond, quick and able as he was, made no dispute about this astonishing affair, but accepted what the other said; he peered at him keenly, and spoke with what courtesy he could, on the sudden, muster:

"I should have known you, Kaiser, but it was a long time ago we saw one another last, and I hardly thought to meet you in such a manner, in such a place."

Maximilian agreed that their meeting was strange enough, and as he was superstitious, he imputed this to more than chance. He came to the table now where Egmond had paused beside the chair of the Maarshalk, and remarked, smiling from one to the other, in the most amiable fashion, "Now we are met we can come to some agreement. I believe in these informal conversations between men of intelligence. What do you say to that, Maarshalk?" he added, greeting the old warrior with a brilliant smile.

Maarten van Rossem was at a loss. He stared and sucked his thick lips, trying to remember what manner of insult he had put upon the Emperor in their late talk. He had called him a fool; well, he thought him a fool, and, after all, what did it matter? The German, Emperor or no, was in their power. Van Rossem continued to stare at him rudely, he did not believe in men like that; frivolous and stupid. What was he doing in Guelders with a small escort, getting into a commonplace fray in a wood, and tramping about alone? Pah! This was no Emperor worth the following—he preferred a warrior like the hard young Duke of Guelders, and he turned looks of loyal love on his master.

Maximilian laughed at the old Maarshalk's sullen discourtesy. "You have a faithful servant there, Egmond," he said in familiar tones. "I would he followed me; perhaps some day that will be the same service, eh, Maarshalk?"

Maarten van Rossem made no response to this specious flattery, save to grunt out some half inarticulate answer, and to gaze with eyes of experience upon the person of Maximilian, taking in every detail of his figure and face. The Maarshalk did not approve what he saw, he disliked high Roman noses and long hair, he scorned hunting trousers and soft boots—a sensible man would always go in steel nowadays...a reckless trivial fellow, this boasting Hapsburg.

"Come," added Maximilian, still smiling, perhaps half ironically, "I cannot endure any longer the closeness of this room, I am going out into the garden, and so you join me when you have a little consulted together what you would say to me."

With that he left them with a dignity that they could not deny, gracefully opened and closed the door, with as easy an air as if they had met on some State and ceremonious opportunity in one of their own houses.

"Good faith!" cried Karel, when the door had shut upon Maximilian, "what do you make of that, Maarshalk?"

"The man is a boasting fool," was the sneering reply of the old warrior. "The best way out of this affair is to slit his throat—it will pass for the act of some of these wayside robbers. It could quite easily be done," he added, with a hopeful look at his master. "We have a party of fifty coming up in an hour or so to this appointment."

Karel van Egmond was not surprised at this suggestion. He was used to such instances of brutal ill-breeding on the part of his Maarshalk—he did not trouble to give the remark serious consideration.

"Chivalry and, I think, policy," he replied, drily, "forbid that we should touch him; he is entirely in our power. It would certainly be convenient to clap him in prison, but that could not be done without a great scandal, which would not work out to our profit."

"As you will," grumbled Maarten van Rossem, "you are always too nice. Most men would take advantage of a fool like that."

"Are you sure that he is a fool?" asked Karel van Egmond softly, "he may have very precise and subtle reasons for coming like this to Guelders, and as for that misfortune in the woods about Venlo, I must wash my hands of that, it has an ill colour. He is Emperor Elect, Maarshalk."

"Eh, eh," sneered Maarten van Rossem rudely, "you do not intend to do homage for him for Guelders, do you, Egmond?—that is why he has come here, to force you, Egmond. He has been importuned by the entreaties of Albert of Saxony, his stadtholder, to come to Guelders and deal with the matter himself; and, being romantical and extravagant, he has done so—not at the head of an army, but alone, like a wandering pedlar or mean merchant, to confer with you as one prince to another. That would be his humour."

"That would not be unlike his humour, at least," conceded the Duke of Guelders, reluctantly, "and I must meet him in the same fashion—extravagant caprice though it be."

"Caprice," sneered van Rossem, "caprice! This Maximilian wishes to behave like the heroes they put in fairy stories to amuse the children. He is sick with dreams."

"Perhaps he has the elements of greatness in him," mused Karel van Egmond, frowning. "I do not know him. During his father's life he has been somewhat eclipsed."

"He couldn't hold his wife's dowry," jeered the Maarshalk, "they had him on his knees in the marketplace at Bruges, didn't they? His head is in the clouds. He dreams to be a Constantine, or an Otto, or a Charlemagne, and he has no revenue, and no army, and no capital. Faugh! do not trouble with him, Egmond."

But the Duke of Guelders could not feel this robust contempt for Maximilian of Hapsburg, whose character might be fantastic, and whose circumstances were doubtful and perhaps desperate, but who was Emperor Elect, protected by the Pope—Emperor of Germany, of the West, of the Holy Roman Empire. There was a splendid pretension there, as he had said. And what was he, the Duke of Guelders? A man who held a fief of that same Empire—a little country between Germany and the Netherlands, and one that was scarcely his by right, for his grandfather had mortgaged Guelders to the house of Burgundy and never redeemed it. If this came to a matter of sheer equity, it was Maximilian, and not he, that was lord of this beloved strip of land on the banks of the Waal and Rhine; so the jurists would decide—that he, Karel van Egmond was what Maximilian had named him—a bold, audacious rebel.

Maarten van Rossem spoke again. "If this Maximilian," he asked scornfully, "could hold the whole Empire, do you think he would trouble about Guelders? What is rule here to one who rules from the Danube to the Marne, from Hungary to Holland?"

"You judge men coarsely and rudely," replied Karel van Egmond briefly, "maybe this Maximilian is deep and subtle. His life has been full of heroic actions, but none of them fruitful. It may be his destiny, and not he himself which has so far restrained his glory. It may be that he has some deep meaning in coming here like this. Why did he mention Graaf Bernard?—that touched me closely."

"Go out and speak to him," advised the Maarshalk, "while I sleep off my food. I shall be of no use in your subtle and cunning council. You are the better man, Egmond. See that he does not flatter or beguile you. As you say, I judge grossly, I have no dealings in your deep practices. Were it left to me I would despatch the fellow, for I take him to be but a plague and an impediment to better men."

Karel van Egmond had no answer to this rough counsel. The Maarshalk was deep in his confidence, the best trusted leader of his vagabond armies—one who loved Guelders and Egmond. But, also a man careless and indifferent in matters of policy, a man of action, of the camp not the council room.

With a frown on his smooth brow Karel van Egmond went slowly through the dark corridors of the inn, and out into the pleasant garden at the back, where Maximilian waited for him under the fruit trees which grew at the end of the vegetable and flower patch, and sloped down towards the wide shining river.

This nobleman had been brought up in exile and penury. His father had always rebelled against his grandfather, and the two princes between them had torn Guelders into miserable factions, the sufferings of the elder and the cruelties of the younger had been a scandal in Europe, and the rich and beautiful province of Guelders had been lost to the family of Egmond. The old Duke Arnold had mortgaged his province for what money he could raise from Charles the Rash, Duke of Burgundy, and the young Duke Adolf had been slain in a paltry skirmish beneath the walls of Nimwegen. His wife, Charlotte de Bourbon, died of a broken heart, and was buried in the great church of St. Stephen, lonely, behind the altar, in that same magnificent city, while her two little children, Karel and Filipa, had been brought up in pity and charity at the Court of Burgundy, under the wise and tender care of Mary, the heiress of Charles the Rash. She had married this Maximilian, the Archduke of Austria, the same year as the great battle of Nancy, when her father had gone down in the red ruin of a terrible fray, conquered by the same Rene of Lorraine who was now the husband of Karel's sister Filipa. On the death of Mary, only five years after the date of her marriage, Karel had fled from the Burgundian Court, and joined any noble who might be in the field in any petty warfare, fighting under Englebert of Nassau, and any other princeling who would hire his sword and his youthful energy. Karel had not remembered with gratitude the kindness he had received from the House of Burgundy, or the gentle ministrations of Mary; he had remembered only the grievance that his grandfather, Arnold, had sold for those ninety-two thousand ducats the Dukedom of Guelders, in return for aid against his son Adolf. And now they were both dead, that contending bitter father and son; and he, the grandson, was disinherited through their folly and cruelty. Escaping from the guardianship of Englebert of Nassau, Karel had returned to Guelders and been most warmly received by the warlike inhabitants and the independent nobility of that province, who had never consented to the sale of their land to the Court of Burgundy, and despised the overlordship both of that House and of the man to whom that House's honours had descended—Maximilian of Hapsburg, Archduke of Austria, now Emperor Elect.

Katharine of Guelders, the aunt of Karel, had been ruling the province in his name, and she gladly and proudly proclaimed him Duke. But all these high and brilliant hopes were consumed by the fact that a few months later Karel was taken prisoner in that skirmish with the French at Bethune, when he had been placed in the fortress of Peronne. After many sharp and bitter negotiations he had been ransomed by eighty thousand gulden supplied by the men and women of Guelders, and by the fact that Graaf Bernard van Meurs, grandson of Vincent Graaf van Meurs, had taken his place. This was eight years ago, and Graaf Bernard was still in Peronne. Karel van Egmond had craftily held his lordship in Guelders—not openly defying either Frederick the Third, the late Emperor, nor Maximilian, King of the Romans and, in right of his wife, Lord of Burgundy and the Netherlands, but ignoring their claims, and gripping his own dear lands against the peaceable and industrious Hollanders, the Flemings, and the Duke of Juliers and Cleves, who lay on his strongly fortified borders. Karel van Egmond, playing this sharp high game with impetuous ardour and crafty intelligence, had not believed that the turbulent and troubled Maximilian of Hapsburg would interfere with him, either as Overlord of the Netherlands, or as Emperor Elect.

Now the man was here—in this mountebank fashion, sitting under the fruit trees of this mean inn garden, waiting for him to speak to him. And speak to him about what? That atrocious affair of Bernard van Meurs? Karel van Egmond was vexed and disturbed, on his guard, afraid of a trap. Did Maximilian hope to get him back into the great fortress at Peronne—prisoner for life? He walked reluctantly down the narrow garden path and, for once, he omitted to give a look of fierce gratitude and passionate love to the rich and smiling beauty of the landscape, which so seldom failed to fill him with the warmest and purest emotions a man might know; love of Guelders and the warlike people of Guelders had coloured all his turbulent and difficult life.

Maximilian was sitting by a row of beehives which stood under some apple trees which had just been stripped of their early fruit, and he was gazing with an appreciative eye at the spreading loveliness of the landscape. Karel van Egmond observed this with jealousy. "It is a fair country, is it not?" he remarked, as he approached Maximilian. "All your Empire!" and he could not keep the mockery from his cold voice. "I think you have nothing finer than Guelders with its woods and valleys and castles and fields—"

"A prince of your temper," replied Maximilian with a smile, "should be addicted more to the arts of peace than those of war. If you love the beauty of our rich country, Egmond, why do you not keep it immaculate from outrage and rapine?"

"The nobles are greedy and powerful," said Karel, solemnly.

"But your Overlord is strong," smiled Maximilian. "What the Duke of Guelders cannot achieve the Emperor may."

TO the acute, alert and practical mind of Karel van Egmond nothing could have sounded more futile and foolish than this statement which Maximilian made so sedately and graciously. For Karel believed that Maximilian of Hapsburg had scarcely any power at all; he was, as the Maarshalk had just so rudely said, a prince without an army, capital or revenue. He moved from town to town, from castle to castle, often as now, from inn to inn. He was full of a thousand golden projects, and pursued by a thousand humiliating disappointments. His life had been full of great affairs, but they had left little substantial benefit behind them. Wars and peace, treaties and alliances, and even the most resplendent marriage, had left Maximilian of Hapsburg little more than a brilliant adventurer. Karel van Egmond's designs had been on a smaller scale, and so far he had more accurately achieved his ambition. He was at least master in this little dukedom of Guelders in a way that Maximilian of Hapsburg could not consider himself master in any spot of ground—not even in his own native archduchy of Austria. In aiming at so much the House of Hapsburg had lost a great deal of what they might have had, naturally and by right. Over two hundred years ago Rudolf, Count of Hapsburg, and Landgrave of Alsace, had been elected Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, and his successor had held that dubious yet grand office ever since, having added to it by conquest and by marriage two kingdoms of Bohemia and Hungary, and many lordships and principalities, until their domains, as Maarten van Rossem had said, reached from the banks of the Danube in Hungary to the banks of the Marne. With sneering admiration it had been remarked that the House of Austria had gained more by prudent marriages than others gained by costly wars, and this young man sitting under the apple trees by the beehives had been of all his predecessors the most fortunate in that he had married Mary of Burgundy, sole heiress to her father's vast pretensions, which Charles the Rash had inherited himself by a fortunate marriage and conquests of his ancestors, the House of Burgundy having gained the Earldom of Flanders by marriage, and the Countship of Holland and Zeeland and Hainault by intrigue and violence.

Burgundy had been seized by Louis XI, King of France, at the death of Charles the Rash on the fatal field of Nancy, but all this Prince's other possessions had descended to his daughter, and through her to this Maximilian, Archduke of Austria, afterwards King of the Romans, and Emperor Elect. It was a most magnificent dowry the young girl had brought her husband—a landless man, and son of a prince who had been elected Emperor, because of his feeble impotence, and who was sometimes called, because of his penury, Frederick of the Empty Bags, the nickname given to his namesake and cousin, Frederick of the Tyrol.

Even stripped of Burgundy, Mary's dowry had consisted of sixteen provinces, two hundred and fifty large cities, six thousand three hundred large villages, and a hundred thousand small villages.

Often had Karel van Egmond, even while as a child he was being brought up under Mary's tender care, gloated over this same dowry. "What would I have not accomplished," he had thought, sternly, in after struggles, "if I had married a woman with such princely dependencies?" And even now, meeting again the man on whom this high dazzling fortune had fallen, he considered him with some contempt and some compassion, because he had not made a better use of such an opportunity. But, no doubt, Maximilian of Hapsburg (Karel could admit as much) had been harried and hampered by rebellious burghers and turbulent nobles. Now, perhaps, that he was able to call himself Emperor, now that the feeble and futile old father was dead, he would contrive to assert his overthrown authority. He was, at least, a man of a multitude of designs and of a restless ambition.

Karel van Egmond paused by the beehives, waiting for Maximilian to speak, and regarding with his light and sullen glance the dear and desired prospect of Guelders. While he had been considering the fortunes of Maximilian, Maximilian had been considering the fortunes of Egmond.

The Emperor was a prince who could justly pride himself on his management of his fellow-men, his pleasing courtesy, his unstrained agreeable manners. The charm and graciousness of his personality had so far won more for him than either his statecraft or his arms, and he had assured himself and his councillors that, once he had met Karel van Egmond, he would be able immediately to adjust the differences between that prince and himself. He had been pleased with his fantastic meeting with Egmond, but now, ardent, volatile and gay himself, he was a little distressed by that straight narrow face, those cold, light eyes, by the hard severe manner of the man whom he remembered as an impetuous and wilful boy...not so long ago, in the Burgundian Court at Bruges.

"You and I should be friends, Egmond," he began in an agreeable and engaging manner. "Men like ourselves should not quarrel, but be united."

"I have no wish to quarrel with you, Maximilian of Hapsburg," replied Karel van Egmond, drily; "for ten years—that is, since I was free and in my own estate, I have not affronted your power nor crossed your schemes."

Pleased by this fair opening the Emperor stated his case plainly and with candour.

"You have raided my towns of Holland, you have taken many by force, and many by treachery. You rob and plunder my subjects coming to and fro Germany and the Netherlands, as yesterday, Egmond, I was robbed and plundered outside Venlo. You have married your sister to the prince who slew my father-in-law at Nancy, you intrigue and ally yourself secretly to the French who are the greatest enemies I have. You have repeatedly refused to come to the Diet to do homage to my father for the Duchy of Guelders, and you have often forgotten, Egmond, it is not your Duchy at all, but that your grandfather, Arnold, sold it to my father-in-law for ninety-two thousand gulden."

Karel van Egmond had hot and stern answers ready to all these accusations, but he did not care to voice any of them. He was, above everything, prudent. He contented himself, therefore, with quietly replying:

"As to that bargain with my unhappy grandfather, Duke Arnold, I was not privy to it, nor were the people of Guelders, and if you are in need of the ninety-two thousand gulden, I have no doubt that we can raise them, and so redeem the mortgage on the Duchy."

He said this with a little scorn, almost as if he spoke to a merchant or tradesman, for he knew that Maxi, like his father, was always in bitter want of cash. But Maximilian was also contemptuous of money; when he had any he spent it on luxuries, not necessities; in adding to the rich treasures of the Hapsburgs which had been accumulating since the days of Rudolph, or on some brilliancy of adornment for his person, his troops and his houses. He, therefore, at once refused Karel's offer without even considering its value.

"I did not come here to bargain about money," he replied, at once sweetly and grandly; "I came to see if we could not enter into some manner of alliance. I have, Egmond, princely schemes on foot and it is men like you to whom I would entrust them. A scheme of conquest, crusade—"

"A scheme," smiled Egmond, coldly.

"I wish," said Maximilian, "to drive the Turks out of Croatia, to lead a crusade east, to sail up the Danube into the Bosphorus, and snatch Constantinople from the heathen. Is that not a worthy design for a prince?"

"It is a pretty ambition," conceded Karel van Egmond.