'Matters of Heaven and Hell are mingled in this business,' says one of the characters in this story. It is, indeed, a strange and compelling tale. An historical romance of love, intrigue and adventure, it is at the same time a subtle and haunting allegory, in which the characters move through a twilight world where dream and reality are one. It concerns Julius Sale, a young Scot who is studying law at Leyden University, and whose life is dominated by the single aim of avenging the death of his father. To do this, he believes that he must compass the ruin of a young man of his own age, Martin Deverent, the son—or so Julius believes—of his father's murderer. The intensity of his hatred brings about the strange events of a story which proves ultimately that, strong as is the power of hate, there are forces still stronger which will, in the end, prevail. But much befalls Julius before he discovers this, and, to his own bewilderment, he becomes involved with three mysterious personages, among them a botanist named Dr. Jerome Entrick—the enigmatic 'Man with the Scales' from whom the book takes its title. The late Miss Marjorie Bowen was a distinguished and remarkably fertile writer who occupied a unique position in her particular genre, and this, her last novel, is a work of unusual qualities.

| • Chapter I • Chapter II • Chapter III • Chapter IV • Chapter V • Chapter VI • Chapter VII |

• Chapter VIII • Chapter IX • Chapter X • Chapter XI • Chapter XII • Chapter XIII • Chapter XIV |

• Chapter XV • Chapter XVI • Chapter XVII • Chapter XVIII • Chapter XIX • Chapter XX • Chapter XXI |

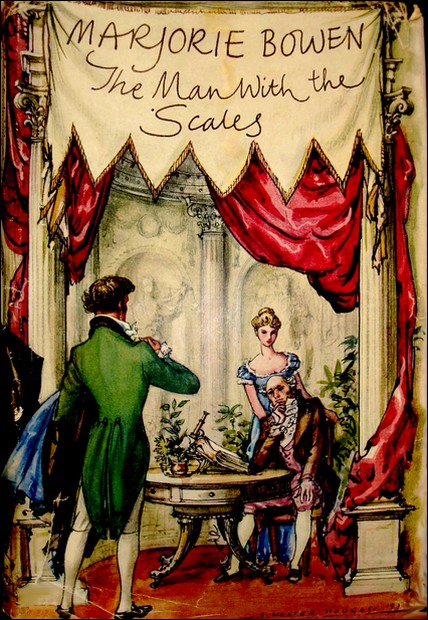

The Man with the Scales - 1st edition dust jacket

Julius Sale was delighted to see the brilliant stranger who was so in keeping with his own mood and the sunshine of the winter day.

Life was neither dull nor uncomfortable for Julius, who was young, strong, rich, and possessed happy prospects; moreover, he found the background of the entrancing town of Leyden very agreeable and was very satisfied with the prospects open to him when he should return to Scotland.

He had worked late into the night at his law studies; but before he had retired he had given some thought to a design never absent from his soul—that of ruining an enemy.

As he possessed the self-confidence of one well born and well dowered who has never received a rebuff, he went up to the stranger, who was pausing by the great canal to watch the barges bringing up their winter cargoes. "Ah, sir, you are new to Leyden, I think," said Julius with a pleasant address that avoided any air of effrontery. "You should see this sight in the summer, when flower petals and fruit seeds are scattered from the barges along the quays."

"I doubt if I shall be here in the summer," replied the other with a civil smile, adding: "I wonder why you take notice of me among all those who go to and fro in this excellent city."

Julius had spoken in English and without thought; now he was impressed by the perfection of the other's accent, for he did not take him to belong to his own nation.

Slightly set back, he replied:

"You suited my thoughts and the day. Pardon me if I have offended."

"By no means," replied the stranger. "I have few acquaintances here and I shall be glad of your company." Julius was flattered.

"Shall we go to the coffee house by the Morsch Gate?" he asked. "The Golden Standard?"

"With pleasure."

Julius was regarding the stranger with considerable interest. He was a well-built, finely formed man of middle age with an air of remarkable distinction that consisted more in his regard and bearing than in his looks, for he was not handsome, his features being rather flat though robust and well coloured; his clothes were of the finest quality but without ostentation; Julius perceived that he was followed closely by a servant in a plain but good livery; this fellow was of a pleasant aspect but slightly deformed.

"You, sir, are not English?" asked Julius, as they proceeded towards the Morsch Gate.

"No—nor am I a Scot," replied the other. "Both I and my servant—I perceive that you regard him closely—come from a far distant kingdom and serve a mighty master."

The native pride of Julius was somewhat offended by the tone of these words, which seemed to hint at some haughty mystery. He gave his own name: "Julius Sale of Basset."

"I am Baron Kiss," smiled the other.

"I think that is a Hungarian name?"

"Certainly. My master is both King and Emperor; he employs me on important business. This poor fellow is named Trett. You might consider him my body servant or else a mere jottery man."

"What! You are familiar with the vulgar idiom of my own country—the Scottish Border!" exclaimed Julius. "I have never heard that term 'jottery man' beyond my native place."

"I have travelled widely and studied much," replied Baron Kiss. "It is not difficult to pick up odd scraps of knowledge."

The air was bluish, and the sunshine had not melted the frost that lay white in the shadows; the smaller canals were coated with ice; the buildings of exquisite brickwork, with applied ornaments of white plaster, showed in flat, pale tones; the leafless trees shivered delicate outlines in pale shades of lustre.

The two entered the coffee house that bore the English name of the Golden Standard, in compliment to the large number of students and travellers who came from Great Britain. The servant disappeared; Julius did not observe how he crept away.

The coffee house was well appointed and one of the most popular in Leyden.

"You know a fair number of people here?" asked Baron Kiss.

"Yes, indeed, but of course I always feel an alien."

"I have heard very good reports of you," smiled the older man, and again Julius, who considered himself not at all meanly, was slightly offended; this stranger was not his schoolmaster.

Baron Kiss perceived his pique and added at once:

"No one can be long in Leyden without hearing of the excellent abilities of the well-graced student—Julius Sale of Basset."

This compliment satisfied the younger man.

"I was up with my books until early this morning," he said. "I hope to do well in my law studies."

"And in everything else, I suppose? Come, admit that as the sole heir of a wealthy house your prospects are superb."

"I do not deny that," replied Julius, drawn out by the stranger's manner, which was at once flattering and reassuring; they drank their coffee together as if they were old friends and gossiped lightly of this and that.

Suddenly Baron Kiss asked:

"Were you thinking of nothing but your legal studies when you lay awake this morning?"

"Perhaps not," admitted Julius.

"What then was your design?"

Julius did not know why he gave his confidence to one whom he had met so shortly before; but he replied, as if without his own volition:

"Revenge on an enemy."

"Are you at Leyden because of this intention?"

"It is true that I thought that a complete knowledge of the law might help me to ruin this man—a Leyden degree is very useful."

"To ruin this man," repeated Baron Kiss. "That sounds cruel."

"His father killed mine," Julius broke out impulsively. "Is it not natural that I should wish to avenge such an atrocity?"

"What age is he—this enemy of yours?"

"About my own."

"Then he must have been a small child when this crime was committed."

"How do you know that?" demanded Julius.

"I guessed. A feud, I suppose, and as such something that has nothing to do with you."

Julius found himself telling his story. It sounded in his own ears very commonplace when related in the comfortable atmosphere of the Leyden coffee house.

Yes, there had been a feud; one of long standing about a parcel of land and some other matter; the so-called crime might have been an accident; the two men had been out shooting together; the verdict had been 'not proven'; but the man once accused and always suspected had gone to Italy and France soon after his acquittal and there died, leaving one son to grow up in poverty on his small estate. Many angry relatives had told the tale again and again to Julius, until he was convinced that his father had been murdered. He was studying law because he thought that by some legal quirk or quibble he could deprive his enemy of his estate; the two families had once been connected, and some clever jurists had secretly assured Julius that there were many flaws in the titles that his enemy Martin Deverent held.

"The land would be useful to me also," said Julius. "And it is a poor price to pay for the death—murder, rather—of a man like my father."

"Has this young man any knowledge of your design, which I must say I applaud?" said Baron Kiss.

"No. We have hardly met. I am glad that you agree that what I intend to do is just—"

"So it seems to me."

"Then I will tell you that I do not intend to stop at the estate—there is a lady—" Julius paused; never before had he spoken so frankly of this affair that lay at the very centre of his being.

He gazed dubiously on Baron Kiss, then down at his coffee cup, beside which stood an empty glass.

"Have we been drinking?" he asked childishly.

"My dear fellow, you yourself ordered the brandies—surely you recall?"

"I cannot say that I do. Maybe I was a little lightheaded after a night nearly sleepless—and then the frost."

Baron Kiss smiled indulgently.

"I am quite prepared to play the host," he remarked with a slight bow.

"You could not suppose that I was thinking of the reckoning?" exclaimed Julius. "What surprised me was that I gave a lady's name."

"You did not do so."

"It was on my tongue." Julius beckoned to the waiter and ordered two more brandies. "We should be drinking this chill weather."

"It is a beautiful day."

"Yes, indeed."

The brandies were brought, and this time Julius noticed the warmth that loosened his speech.

"Her name is Annabella Liddiard," he said. "And she is almost betrothed to this enemy of mine."

"A pretty name," remarked Baron Kiss courteously. "Yes. She has no dower and therefore is not much sought after, but I admire her myself—"

"Still, your motive is revenge—you wish to take this Annabella Liddiard away from this other young man; your enemy, as you think."

"The murderer of my father," said Julius quickly.

"Or rather, the son of the man you suppose murdered your father?" Baron Kiss put in his correction gracefully.

"Yes, yes, I have told you the story. Perhaps you think that I am acting badly, but let me tell you that I intend to marry this girl—even against the wishes of my relations."

"You are in love with her?"

"By no means. But I do not wish to abuse my position by doing anything dishonourable."

Julius spoke with a simplicity that accorded with his comely aspect and took all suspicion of bragging from his words.

"And what are her feelings?"

"I do not know. She is extremely simple and, I suppose, will be ready to make a good match. At least, her people will—they are both ambitious and not rich. Her mother in particular urges on an engagement with me."

"Your prospects are excellent."

"Quite how do you mean that?" asked Julius.

"I mean that you are likely to attain the revenge you seek and to deprive this young man of his estate and his betrothed wife."

"Put like that, the thing doesn't seem pleasant."

"Yet you are elated at the thought of success, are you not?"

"Yes, I confess I am—I have hated this Martin ever since I can remember."

"You think, perhaps, that hate is stronger than love?" asked Baron Kiss.

"I do, indeed—despite all the preachers say. After all, no one loved me very much."

"Not even your mother?"

"Oh, she is a reserved sort of person. I think that all her affection was given to my father."

Baron Kiss called the waiter and asked for a church-warden pipe, which he filled and lit with a deliberate gesture. It seemed to Julius that his face was shining, although he sat in shadow, and that his manner had increased in self-confidence.

"My tale cannot interest you—indeed, it must seem rather paltry."

"By no means," replied the elder man. "There is something majestic in your design that I much admire."

"Perhaps you would if you knew the whole story. I am really rescuing Annabella from a hard life as a poor man's wife."

"Is she really betrothed to him?"

"Oh no—but somehow it has been an understood thing—they are close neighbours."

The coffee house was now empty; a mellow light came from the brass lamps and a gentle warmth from the white porcelain stove. Julius had thought it was early in the day that he had met Baron Kiss, but now surely it was afternoon; probably he had told his story at greater length than he had supposed; he said as much, with reserve and dignity, but Baron Kiss gave his arm a reassuring touch.

"My dear fellow, I have not been so interested for a long time. Why, I can see the whole thing, the people I mean, and the background—"

"It is familiar to you, perhaps, the Border? But I think I asked you that before—"

"It is familiar."

"Strange that I have never seen you—we have few strangers. I hope that one day you will visit me at Castle Basset."

"I hope so, too."

Julius was a little breathless; he supposed he was excited but could not think why this should be; the image of Annabella in her green snood and scarlet dress was clearly before his inner vision.

He ventured on a further confidence.

"My mother knows nothing of my plans, of course—she hopes that I shall marry another lady."

"A pretty tangle, I see!" smiled Baron Kiss. "So your mother is not revengeful?"

"Yes—but her manner is different from mine. She has always ignored this Martin and never mentioned the dreadful episode that killed the heart in her—yet I think that she will be glad when he is ruined—"

Baron Kiss glanced at him keenly out of his sharp little eyes.

"I know this all sounds—well—hateful," Julius once more protested.

Baron Kiss seemed to think this over gravely; there was, however, a pleasant smile on his face that encouraged Julius.

"You see, sir, this Martin is like his father—no one has heard anything good of him. It is a bad family, there is much to his discredit."

"I can quite believe that."

"You are very kind, sir, yet I fear that I have cut a poor figure in your eyes—"

"How often must I repeat that I have heard excellent reports of you and much admire your design?"

"I am an utter stranger—"

"I trust that we shall soon be much better acquainted—and remain on good terms—"

"I am flattered," said Julius.

Baron Kiss smiled across at him with a direct stare and slightly inclined his head.

'How important he looks!' thought Julius. 'Certainly like the servant of a great King—or, rather, Emperor. I wonder what opinion he would have of Annabelle.'

Some customers came into the coffee house; cold air followed them before the heavy doors were shut.

"I shall be pleased," said Julius, "when I have taken my degree and am able to go home."

He spoke with great simplicity; not in the least as if he was capable of planning a long revenge on a man who had not injured him at all.

The Baron gave him a glittering glance of appraisal. Julius was good to look at; graceful, yet massive; everything about him was pleasant; his thick yellow hair hung down like a cap, straight and smooth, and his large grey eyes had an expression of utter candour; he seemed serious and in great earnest; he had an air of having something important to do in life.

"We have sat here too long," he said, rising. "I must not neglect my studies."

"Yes, let us be going," agreed Baron Kiss. "I lodge in the Breestraat—perhaps you will walk some of the way with me?"

Julius gave his own address. He did not want to lose sight of the stranger, yet he was not sure that he altogether liked him; something in the manner of Baron Kiss roused a little prickle of pride in the young Scot.

They left the coffee house together.

The sky was now of a greenish hue, against which the outline of the steep gabled houses stood out sharply; the time seemed to Julius early afternoon. He could not recall when or how he had met Baron Kiss or where he had taken his midday meal. Trett, the servant, with an obliging humble air had taken his place behind his master. Julius found something familiar in the man; what it was he could not say.

There were many people going about on the cheerful business of winter; some with skates, others with wreaths of evergreens.

"I fear that I have missed my lecture," said Julius, "but it is no great matter."

"Certainly not—why, I could teach you in a few hours more than any of these pundits."

Julius was gratified by the Baron's interest in himself and by the worldly man's fluent charm. He did not regret that he had told him so much of his story; indeed, he was eager to relate more details.

"Lydia Dupree—of French descent—is the lady my mother wishes me to marry," he confided, "and I must confess that she is a fashionable beauty of a swinging fortune—"

"Yet you prefer this Annabella Liddiard?"

"Only in order to confound my enemy. She would, alas, be unhappy with him, as I have told you; he is a man of evil tendencies."

"And as such deserves to be punished," said the Baron comfortably.

"Yes, a bad landlord—one without regard for truth or honour—"

"You do well to remove him from the society of decent men."

"But Lydia is a most fair creature."

The Baron was directing their steps into a part of Leyden unknown to Julius.

"I thought you said we were going to the Breestraat?" he asked.

"I have changed my mind. There is an amusing place I should like you to see."

They paused before a building, trim and gay, of red brick and white pilasters, which Julius could not recall seeing before. Baron Kiss rapped on the door with his elegant cane. Julius now perceived that his attire had a military cut and was looped about the seams with braiding in the form of thin laurel leaves.

The door was opened at once by a smart footman in a dark livery; behind him was a vista of light, a corridor which was lit by highly polished candelabra. The servant seemed to know Baron Kiss and bowed with almost exaggerated politeness.

"I am bringing a young friend of mine, well known in Leyden for his learning and the state that he keeps."

The footman bowed again, and Julius followed the Baron into the corridor, which was painted white. Julius noticed that Trett slipped in behind his master. They were at once taken to a large door leading out of the corridor; the footman opened this to show a circular room where a close company were gathered round a table that occupied most of the space.

There was something about the place that Julius did not like. The people, all youthful, had the faces of dolls and wore fantastic straw hats over which were laid sheaves of wild flowers.

It was plain that they were gambling; cards and money were heaped on the green table cloth. Julius had never suspected that there was anything in the nature of a gambling den in Leyden.

Beyond the table was a large mirror with a shelf in front that held a vase of winter evergreens. Nearby stood a young lady who appeared to view the scene with contempt; she was beautiful in a dark Eastern style and dressed in a costly manner Close to her stood a little man of middle age who also surveyed the gamblers with a slight degree of disdain.

As Julius and Baron Kiss entered everyone became still so that it was like looking at an exhibition of waxworks; then suddenly the girl by the mirror laughed; everyone joined in the merriment, and the gamblers took off their masks, as if at a given signal, disclosing the fresh and comely faces of students and the daughters of the citizens of Leyden, many of whom were familiar to Julius.

Their laughter seemed to be pointed at him as if he had in some way been made a fool of, and he glanced at Baron Kiss in a questioning manner.

"I had no idea that this sort of pastime went on in Leyden," he said; "and still less do I know why I was brought here."

"I don't suppose that any of these had any idea of the tale you have just told me," smiled Baron Kiss. "Most people have a secret or two."

Julius now regretted that he had confided in this stranger; he tried to deny what he felt was a piece of folly.

"Oh, as to what I have told you about Martin, Annabella and the death of my father—there is no truth in it. I invented it all—"

"Perhaps you think that I have invented this building and this company?" smiled Baron Kiss.

"No, indeed. I do not take you for a magician," replied Julius; but he was vexed with everyone in the room, including himself. He felt galled that so many of his fellow students, whom he had seen so often decorously enjoying a pipe and a glass of ale in the modest elegance of the Golden Standard, should all the while have been leading this other life of which he knew nothing. He was not pleased, either, to observe, seated at a gambling table, so many young ladies to whom he had always bowed respectfully on the quays or whose finger-tips he had kissed with so distant a courtesy at the formal gatherings given by their parents.

The whole thing seemed like a trick, and he felt a dislike for Baron Kiss (if that really was the fellow's name) for placing him in so disagreeable a situation.

The quiet-looking little man by the mirror came forward and introduced himself as Dr. Jerome Entrick. He at once presented the lady, naming her as his niece who was keeping house for him. He had just, he added, come to take up his quarters in Leyden, where he now held a professorship in botany. He soothed the annoyance Julius felt at the gambling party by explaining that it was all a newly got up affair and they had not mentioned it to Julius as they considered him of too serious a bent to be interested. "As indeed I am," said Julius, eagerly swallowing this sop to his vanity. "It is my earnest wish to get my degree as soon as possible and to return to Scotland"—he glanced at the Baron and noticed for the first time that he wore a curiously shaped cap, of a military cut, the flap of which was turned over and fastened by a jewel of a blazing intensity.

The students and the girls now gathered round Julius and pressed him to join in a game of chance; the stakes were, they declared, very low. He smiled at this enticement, for he had plenty of money.

"Nothing keeps me in Leyden but my studies," he said with an air too grave for his youth.

Dr. Entrick's niece, Amalia von Hart, then asked them all to supper in the adjoining eating room; all excused themselves, however, and, taking shawls and fur coats from the hangers, went their ways, cramming their masks and hats wound with wild flowers into their pockets.

"Well, then," said Amalia, speaking directly to Julius, "will you come and have supper with us and Baron Kiss, or must you always be at your books?"

Julius sensed a challenge, perhaps a mockery, in these words.

"Do not hesitate because you think you are guarding a mystery," added Amalia. "For, of course, your story is well known in Leyden."

"I have not spoken of it to anyone before today!" exclaimed Julius.

"I dare say. But there are many Scots here, and all these feuds are publicly discussed."

"My thoughts and intentions cannot be," replied Julius. The empty gambling room now seemed desolate; he wished that he had not met the Baron, or, for that matter, Dr. Entrick and his niece; all three of them seemed to treat him in a way that made him feel raw, inexperienced, and as if his story, which had so far seemed so important to him, was remote from reality and of no consequence.

Amalia von Hart put on a pelisse of red fur with a lining of striped Roman silk; she seemed, then, in her dark, withdrawn beauty, to be much more than herself; a symbol of unseen things. Julius, for a moment, thought of both Annabella and Lydia as cast-off loves.

They came into the street. Julius was still ignorant of the time. The steep gabled houses still stood out clearly against a greenish sky; chimes were striking; two different clocks clashed the quarter-hour together yet not exactly in unison; Julius was used to the constant filling of the air with religious melodies; they were so much part of the landscape, with the low, quick-flying clouds, the canals bordered with wych elms and the causeways of clearly polished brick, that the young Scot could not set them separately in his thoughts.

The two older men had gone ahead, as if they knew the way, and Julius was obliged to offer some conversation to Amalia von Hart.

He asked her where she had been before she came to Leyden. She replied that she had lived with her uncle in Pisa; he had held a small post at the decaying University. She had found the ancient Italian town very lowering to the spirits; it was much deserted, and many of the grand palaces were falling into ruins or being used as tenements.

Julius had always had joyous thoughts of Italy, which he one day intended to visit, and he was displeased to hear this talk of Pisa, a name that had always dwelt in his mind with a certain grandeur. Amalia seemed to perceive his mood, for she added: "No doubt the city would look very differently to you, going there as a rich traveller. We had to live poorly. My father was killed in the French wars, and we have only my uncle's fees and so see the sad side of things wherever we go."

"How did you come to know this Baron Kiss, who seems a man of substance?"

"Why, he came to one of my uncle's classes. He had a whim to study botany and possesses a very pretty herbarium. Indeed, I should say that he has studied many things. As I dare say you have noticed, he is rather eccentric and has travelled a good deal. Those who have no settled home tend to become odd."

During this speech Julius was turning over his impressions of the whole episode, and finally decided on frankness.

"It seems to me," he said, "that this gentleman deliberately brought us together—"

"Yes, so it seems to me," she replied with an air of candour. "And I cannot think why. We were asked to that gambling party on the excuse that it was a gathering for music—my uncle plays the 'cello and I sing."

"But there was no music."

"None. Nor, I think, any gambling either; only all those people dressed up in masks."

"But I saw the gold and the cards," said Julius.

"Did you? I perceived nothing of that kind, but I had just come from an inner room when you arrived."

"I don't know what it all means," said Julius, slightly perplexed and even alarmed. "Perhaps it has no meaning. At least I hope that you will take no notice of a story this Baron Kiss will claim to have drawn from me."

"I knew that story before I met the Baron," smiled Amalia. "Of course I don't think it is one that does you credit."

"Indeed? May I ask what your nationality is?" asked Julius, piqued by this blame after the praise given him by the Baron.

"Oh, we are of a mixed race. But you will have perceived that I speak an excellent English—is that not sufficient for you?"

"You do not know Scotland?"

"No—but I have spoken with several Scots in Leyden, both professors and students, and all know your feuds and your design of revenge on Martin Deverent."

This statement seemed odd to Julius after what her uncle had said about their recent arrival in Leyden; nor was he aware that there were so many Scots in Leyden or that they would be likely to know of his story. He was heartily sorry that he had imparted this to Baron Kiss and hoped to be able to dispel the whole situation as a legend or delusion.

The air was balmy though keen and full of the salt spray that forever hangs over the Netherlands. Here and there wooden signs and pennants still faintly showed their colours; Julius could not tell if it were moonlight or the last glimmer of the sun that so faintly lit the streets. The few passers-by were hurrying as if intent on arriving at some important destination, and all of them were muffled against the rising cold.

Julius remembered that usually at this time of the evening (if evening it was) he was at home in his comfortable lodgings copying extracts from the vellum-covered books with the sepia inscriptions, or possibly writing a carefully worded letter home to his mother; she was his only correspondent save for his factor, Maryon Leaf, who sent Julius business reports.

They turned down a side street, where a cold light, which appeared almost like ice, covered the narrow canal. They followed Baron Kiss and Dr. Entrick into a small, quiet house of modest pretensions. Everything seemed to have been prepared for them; there was a light on the stairs, and the room they entered was adorned with flowers in Delft vases, heated by a white stove and lit by candles in sticks of blue and white porcelain. Supper for four people was set on the highly polished table.

Julius was about to exclaim at the out-of-season blooms when he recalled the profession of his host and the skill of the Dutch in raising plants under glass; these flowers were mostly white and of a frail, almost unearthly look.

"Wherever we go," said Amalia, "we contrive to find someone who will grow us flowers, even in the winter time."

"I prefer them in their proper season, when they have a more robust air," said Julius, touching a tress of white lilac of a ghostly appearance. "These have no perfume," he added. "One can see that they have never made contact with the earth."

"That has been said sometimes about me," said Amalia, pointing a finger to her bosom and thus directly drawing attention to herself.

Julius had certainly thought that there was something strange about the girl, but he did not think that she shared the remote scentless, delicate quality of the hot-house flowers.

"You wonder why you are here," she added without coquetry.

"Yes, I am rather surprised at the weakness of my own will in allowing this Baron Kiss to force me into your company."

He turned away from Amalia, who appeared to be soliciting his scrutiny, and looked keenly at the Hungarian as he spoke.

But Dr. Entrick put aside this protest. "There are places set for all of us, as you can see," he remarked. "I hope that you can endure our poor company for a short time. The truth is that I met Baron Kiss as soon as I arrived in Leyden, and begged him to come to supper tonight, bringing anyone he knew of interest—"

"And why did the tryst have to be at the gambling salon?" asked Julius.

"Music rooms, my dear sir," replied the botanist in a tone so whimsical that Julius did not trouble to remark that he had seen cards and money on the table; besides, did one have to wear a mask and a fantastic hat in order to play music?

Julius now noticed that Trett was setting the meal. The food was elegant; some delicately preserved fruits were placed in baskets of filigree silver; the wine was in long, pale green bottles; the goblets had a faint amber tinge, and the napkins were of the finest damask. Julius took his place beside Amalia; he now saw that she was wearing a gown of the most brilliant green colour, laced with gold at the seams.

"Do you recall," she asked, "when you took Annabella Liddiard to a ball—and were snowed up? What merry games you had, and how quickly the short winter days passed before the coaches could get through the snow!"

"It is astonishing that anyone should know that!" exclaimed Julius.

"Oh, I am a gossip, and you have already been reminded that there are several Scots in Leyden who know you quite well."

"I suppose that is so," agreed Julius dubiously. "Still, that anyone should recall anything so trivial—"

"Was it so trivial? You learned a good deal of the character of Annabella."

"But that could only affect myself—no one else could consider it of sufficient importance to keep it in mind—"

"But you see that it has been kept in mind. I can tell you what Annabella wore—white, like the snow, fur and slippers—come, eat up your supper and drink this good wine."

"I think that we should drink a toast to the lady we have been mentioning," said Baron Kiss, half rising, with a ceremonious bow. "The health of Miss Annabella Liddiard!"

Julius could not refuse to rise with the others and honour the name of one who seemed extremely remote. He again wished that he had not mentioned her, and he felt the toast to be not only incongruous, but something of a mockery.

As the meal proceeded he was able to take a close note of his companions. Now that Baron Kiss had removed his hat with the gleaming jewel he showed a high forehead and a smooth tuft of white hair that added to his stately appearance. Dr. Entrick, on the contrary, appeared so ordinary as to be almost featureless; Julius was sure that a few moments after leaving him he would have forgotten what he was like.

There could be no doubt about Amalia's beauty; the richness of her colouring and the precise lines of her features were accompanied by a cool self-assurance and a polished manner that made it seem odd even to the inexperience of Julius that she should be content to fill the part of housekeeper to an ill-paid pedant. Nor, indeed, did her clothes indicate poverty. Still, there it was, she lived in obscurity, and Julius wondered why; he knew that both Annabella and Lydia would fade before her as the candle before the sun.

"Will you not find life in Leyden somewhat dull?" he asked her boldly.

"Oh, I make my own world."

"There is no one like you in this old university city—"

"Perhaps not—or perhaps you have never looked for them. And maybe we shall not be here very long."

These words gave Julius a sudden pang of loneliness; yet he could have been sure that he disliked all three of these strangers, even the beautiful woman whose manner towards him was so flattering; for she seemed to give him all her attention as if she had no one better to concern herself with.

"My visit also," said Baron Kiss, "will probably be short."

"Why, when it comes to it, I don't intend to stay very long myself," said Julius. "Only until the end of the term, when I hope I shall take my degree."

"As if that degree was of any importance!" exclaimed Amalia, with a swift smile.

Julius agreed with this comment, which reminded him that he had a certain contempt for his company. At first he had taken Baron Kiss to be a man of property, and the Hungarian had referred to himself as someone who was serving a master of immense power; but if this was so, how came it that he concerned himself with Dr. Entrick, a poor pedagogue, and his jointless niece?

Julius found himself gazing at all three of these strangers with a curiosity that was touched by hostility. Even the beautiful woman looked tawdry, and the hospitality that had first appeared so elegant now seemed vulgar.

He should not have allowed himself to be drawn into this company; he was at Leyden only because of what most people would term a whim; at home his position was that of a lord, owner of a wealthy estate covering many acres of rich land and one of the mightiest castles on the Border.

"I perceive," said Baron Kiss, filling his glass, "that you begin to grow moody. Would you care for us to discuss your story? It is very familiar to all of us, I assure you."

"I do not know," replied Julius with some heat, "what the vanity of an idle moment tempted me into telling you—but I assure you it was all merely a fable."

"We can soon discover the truth of that," interrupted Dr. Entrick. He rose, calling for his hat and cane from Trett, who seemed to be as much in his service as in that of Baron Kiss.

"The host must not be the first to take his leave," said Julius, also rising. "I was about to be on my way."

"You are coming with us," put in Amalia, accepting from Trett the red fur with the silk Roman-striped lining. Julius could not be rid of them. He thought that they must intend to extract some service from him, perhaps even to offer some violence; he was still annoyed by their knowledge of his story and irritated by the social inferiority of all of them (save perhaps the Baron) to himself.

A slight storm of snow had fallen while they had been at supper; the buildings were outlined in a glitter, and though the sky had cleared again to a greenish hue, the sparkling crystals seemed still to hang in the air, making it luminous.

"We do not need Trett's lanthorn," said Baron Kiss, "but this is an odd kind of light."

They passed a house where the lower windows were unshuttered. A cheerful festivity was in progress, and groups of laughing young men and women were gathered round a centre table piled with cakes and sweetmeats. This reminded Julius of the party in the gambling house, but there was no sign of either money or cards; on the walls of this bright room were pictures of flowers and fruit, arranged without regard for season, so that the snowdrop lay across the cheek of the nectarine and the petals of the tulip touched those of the dahlia. Julius was already used to the excellence of the Dutch in such studies, and thought that they looked more natural than those real blooms that had decorated the homely chamber of Dr. Entrick.

They passed along a street that Julius took to be the Noordeinde, though he could be sure of nothing; the light was, as Baron Kiss had remarked, odd and uncertain. They paused before the porch of a large church that Julius believed was dedicated to Saint Bavon; he himself attended the Scots Church, but he was familiar with the Dutch churches with their splendid Gothic interiors, ornate and brightly painted organs, whitewashed walls and superb tombs honouring heroes who had died in battle for their country.

He now found himself in front of one of these of a bizarre design, where a young man in armour had sunk into the swoon of death above an anchor, a coil of rope and heavy laurel wreaths; all was sculptured in sparklingly white alabaster and seemed to give out a light of its own in the dimness of the white-walled church.

Julius looked round for his companions but found himself alone; he did not understand how they had contrived to lead him to this place or to escape from him. There seemed no object at all in his being there.

The organ was playing what seemed to Julius to be a majestic slow march; he looked up at the gilded pipes and the columns supporting the wreaths of coarse wooden flowers.

In the small mirror fixed over the keyboard he could see the face of the organist, a young man in a plain black habit.

At first Julius was resolved to blame again the light and his own disordered memories, for it did not seem possible that this could be his enemy Martin Deverent seated in this unlikely place, at this unlikely hour.

But the other had seen him and came to the edge of the loft, looking down. As the wind left the pipes, a last whisper of melody fell across the white, silent church.

"I am obliged to you for keeping this tryst," said Martin; he resembled his fellow Scot in that he was fair, comely and robustly made; but his attire was shabby, and gave him, in this winter season, a threadbare air.

"I made no tryst!" exclaimed Julius in astonishment, moving towards the pale shadow of the nearest pillar. Martin descended from the organ loft.

"I think some friends of mine did so for me," he answered. It was a long time since they had spoken, though each had been familiar to the other since early childhood.

"I do not think so," said Julius. "I was with a party of strangers, all of whom have disappeared. Indeed, I do not know why I am here."

"It is to meet me," replied Martin with conviction. "Was not one Baron Kiss a member of this party of strangers?"

"Yes, but he brought no message from you."

"All the same, he arranged this meeting—at my request."

Julius was vexed by the whole sequence of events: the first encounter with the Hungarian, the visit to the gambling salon and the supper at the chambers of Dr. Entrick; most vexed of all by this forced meeting with the man he had resolved to ruin.

"We can have nothing to say to each other," he retorted coldly.

"On the contrary, we have so much to say that I came to the Lowlands solely on that account."

"You might, at least, have found me in the ordinary way in my lodgings. This is a very strange place for us to be in."

"That may be, but it is the tryst that this friend of mine advised—"

"Friend of yours?" interrupted Julius. "He did not speak as if he were one. As for the other two, Dr. Entrick and his daughter—"

"Well, what about them?"

"They hardly seemed to be there at all," confessed Julius. "We were like so many waxworks at that supper party—while as for the man Trett—"

"This has nothing to do with me," interrupted Martin. "I know only the man Kiss and I know him as a friend."

He looked at Julius with a mournful intensity, and his shadow was thrown over the reclining figure of the mailed warrior on the sumptuous tomb.

"Friends," said Julius with increasing firmness, "we can never be—"

"Surely you cannot still feel any bitterness about that old grievance?"

"Is it to be dismissed so lightly? An old grievance? When your father killed mine?"

"You know that that was never proven—indeed, everyone believes the affair was an accident."

"I do not so believe."

"Why?"

"As if, standing here in this strange place, I could give you the hundred and one reasons—"

"Let us leave reason out of it," persisted Martin. "Supposing that this happened—why, what has it to do with us? We were children at the time—we never harmed each other."

"I do not know why you are talking like this to me," said Julius. "I never threatened you in any way."

"Everyone knows," replied Martin, "that you are taking a law degree in order that you may the better throw me out of my small heritage."

"You may have heard talk of that, yet hardly anything substantial enough to bring you to the Lowlands."

"Yet here we stand—in this outlandish place, to which we have been led in an outlandish fashion."

Julius looked coldly at his enemy, for this was the word that he obliged himself to use about Martin Deverent.

"Why do you not look after your own affairs instead of forcing yourself on me?" he demanded.

Martin took this rebuke in good part.

"It is true that I have led a somewhat thriftless life and not done what I might have with my estates, poor as they are. But the accident brought us all down—as you know. After the acquittal we went abroad, and the property was much neglected. My education, also, was greatly abridged—my parents died in Paris, and when I returned home it was as a ruined man."

Julius took advantage of the other's humility.

"I never heard that you took any trouble to mend affairs—but mooned about and wrote verses and sighed after a girl you could not hope to marry."

"I am glad that you have brought in this name," said Martin steadily, "for it is precisely of Annabella Liddiard that I wished to speak."

"I did not bring in any name," said Julius, to whom the whole scene was fantastic.

"But you invited me to do so," replied the other, still patiently. "I wanted to tell you that I am betrothed to Miss Liddiard—" He held out a golden object that hung from a fine cord round his neck; Julius saw that it was the half of a thin coin. "We exchanged this, Mr. Sale, when last we met, and our promises of fidelity were sincere."

"Should this have anything to do with me?" asked Julius with an angry look.

"We all know that the Liddiards are ambitious people and that they would prefer you as their daughter's husband."

"I have not made any offer for the lady—"

"But you may do so—"

"On the other hand it is common knowledge that my mother designs me for Miss Dupree."

"Can you then promise me," urged Martin, "that you will not any longer trouble Miss Annabella?"

"I did not know that I had ever troubled her," replied Julius haughtily. He began to find the church extremely cold; the massive monument appeared to be carved out of ice.

"You pay her a good deal of attention," said Martin. "And her parents are continually pressing her to listen to you—"

"I repeat that I have made no offer for the lady."

"You only evade me," persisted Martin. "You know that as long as there is any hope of gaining you as a son-in-law the Liddiards will never listen to my suit—"

"And has the lady not sufficient spirit and daring to defy her parents?"

"Alas, no; and she is much in terror of her mother and indeed I have little to offer."

Martin paused and looked intently at the scowling face of his companion. It would not have cost Julius much to make the promise so earnestly and patiently demanded; his design to avenge himself on Martin was growing faint, and he doubted if he would have the energy to put it through. The image of Annabella Liddiard became remote; he could see himself, easily enough, leaving his law studies, going home, marrying the girl his mother thought so highly of and settling down to look after his estates.

The meeting with Baron Kiss had disconcerted him, and Martin had put in his plea at the very moment when Julius, despite the incivility of his bearing, was most disposed to listen to it. Julius did not find it easy to despise the humble yet dignified young man who stood almost submissively before him, asking only that he should forego a few miles of barren moorland that he did not want and a quiet girl he did not greatly desire.

He was about to turn to where Martin was waiting before the monument and to pass his word that he would no longer interfere with the Deverent fortunes when his attention was attracted by a small blaze of light behind one of the white pillars. A second glance showed this to be the jewel that Baron Kiss wore on his military bonnet; as the Hungarian moved forward, Martin retreated yet farther into the shadows cast by the heavy tomb.

"Come, are you going to grant this request, so touchingly made?" asked the Baron.

"I thought you were my friend," said Martin, who was standing in almost total obscurity. "But you do not now speak as if you were."

"I only mingle in the affair out of curiosity," replied Baron Kiss; he turned, with a touch of mockery, to Julius and repeated that young man's recent thoughts almost exactly.

"Come, what is it to give up, but a poor neglected estate and a girl to whom you are not really attached? I dare say that your legal studies will not have done you any harm even if you do not use them for the ruining of Martin Deverent." There was something in this tone—too slight to be termed scorn—that changed everything for Julius Sale.

It suddenly seemed to him the greatest folly to abandon a course of action so long and so carefully preserved, and the figure of Annabella appeared before his inner vision as of a compelling attraction.

"I had not given my answer," he said coldly. "And I find this church—to which you, Baron Kiss, led me—a strange place for this manner of bargaining."

"Rather like an enchantment," remarked the Baron, "as if the power of some spell had brought your enemy across the sea to appeal to you."

Julius laughed at that; but he wished himself away from the church and from the company of both Martin Deverent and the Hungarian.

"I suppose," he said, "that you, Mr. Deverent, if you have anything serious to say to me—for I do not take what you have said as anything but a jest—that you can find your way to my lodgings."

Martin did not answer; he was now totally lost in the shadows of the tomb; of this nothing could be seen but the falling figure of the young hero in his snow-white alabaster.

Baron Kiss took Julius by the arm and led him out of the church.

"Is it true, Baron Kiss, that you are, after all, a friend of this man's and that you arranged this interview?"

"Perhaps so. Yet it is a thing that has been much on your mind, and you may have invented the whole string of incidents."

Julius laughed.

"I am a very practical sort of fellow. I am only surprised at the folly of Martin, idle as he is, who should have nothing better to do than to follow me here."

"He takes very seriously your intention of ruining him and stealing his Annabella—"

"He deserves no better than both misfortunes," said Julius. "I made no promises, did I?"

It was now clear day, and a pale sunshine fell over the snow-mirrored buildings and the canal skimmed with frost; the quarter chimes struck from a nearby steeple.

"I shall get some sleep," said Julius, "before I am due at the university. It seems to me that I have been up all night—and how, and for what purpose, I do not know. I should be glad if you could tell me, Baron Kiss."

"Your curiosity about myself and the whole episode will soon be satisfied," replied the Baron politely. "Did you know that Dr. Entrick is descended from the famous Charles de d'Ecluse—known as Clusias, who introduced the turbaned tulip from Russia into the Lowlands?"

"How should I have known that, and what difference does it make to me? To tell the truth, I found something disagreeable about the couple."

"What! You even disliked the beautiful Amalia!" exclaimed the Baron.

"My feelings are not deep enough to be termed dislike," replied Julius. "But I must urge that I am very fatigued—I seem to have lost a day and a night."

With that he took his leave abruptly of one whom he now regarded as a meddlesome stranger, and set out for his lodgings. It appeared to be dark when he reached them; certainly he had lost all count of time; his cheerful landlady made no comment (he had half dreaded one) on his appearance; he tried to concentrate on his studies, but, after burning half a candle, found that he could not do so; he then extinguished the feeble light, undressed and went to his comfortable bed; was this really the evening of the same day as that in which he had met Baron Kiss, gone to the gambling saloon, supped with the professor of botany and met Martin Deverent before the heroic tomb at the whitewashed church?

When Julius awoke it was broad daylight, and the round- faced serving-maid brought in his breakfast as if nothing curious had happened. Perhaps, he thought, it was all a dream—though he had never thought of himself as a dreamer.

He went to the window, a cup of hot coffee in his hand, and looked out at the handsome street; a lingering sweetness was in the chill air, a lingering gold in the pallid sky, yet the icy gloom of the short winter's day was already everywhere.

Where had he been last night, in the Oude Kirk or that of Saint Bavon?

Leaving his breakfast uneaten, Julius left his lodging and walked briskly in his fur-lined coat, along the tranquil back streets where the notice cubicola locanda showed in many of the gleaming windows. He walked at random; by the Weigh House and the butter market, the harbour with the Zyl Port. Not being able to come to terms with his thoughts or his roamings, Julius took himself to the stables of a man well known to him and there hired a horse; in order to have somewhere to go, he took the level road to a certain ruined castle that he knew of; he had always considered it odd that in a country so completely prosperous there should be a place so completely abandoned.

He paused by the verge of a lake, formed by the overflowing of the old moat, where a lad had gathered some sheep; Julius, who now spoke Dutch with a fair fluency, asked the youth the story of the castle; the shepherd did not know; hollow and forlorn the ruin had stood thus in the midst of the water ever since even old men could remember; the family who had built it must long since have become extinct.

The winter sky now had the quality of blond nacre dabbled with brown tossed clouds; the lake reflected these colours, also the broken walls of the Kasteel and the crumbling towers, one of which still retained a whimsical metal turret and a spire from which no weathercock glittered.

Through the hollow windows of floorless rooms Julius could see the distant outlines of a snow-flecked landscape. On the far bank some peasants watched their cattle trying to find some green amid the winter-bitten grass.

Near to the sheep and close to where Julius had stayed his horse was an uprooted tree—for the winter gales had been sharp—and one of those dark-leaved, thick plants that withstand the winter's cold. Other trees, erect but stripped of leaves, showed within the grim interior of the castle; once a fortalice built for war, and long since useless save as a passing shelter to a vagrant bird or wild beast.

Julius gazed in dreamy curiosity at this desolate building that did not even possess a legend; then, turning the head of his neat patient horse, he went back towards Leyden. His mood was now softened and calm. Had Martin Deverent now appeared before him, Julius would have granted all his requests; nay, if he had suddenly come upon Baron Kiss he would truthfully have assured the Hungarian that he desired no revenge on the man whom he had so long considered his enemy. Yet this halting of his spite caused a halting of all his activities also; it no longer seemed worth while to pursue his studies, nor did he feel any animation at the thought of returning to his native place and fulfilling his mother's wishes by marrying Lydia Dupree.

Leaving his horse at the stables, he returned, in an idle mood, to his lodgings.

The door of the great parlour was open, and he glimpsed his landlady's daughter, a studious girl, bent over her books; everything about her was luxurious and more splendid than anything that Julius might hope to find on his return to Scotland. Once more, and now without knowing that he did so, he admired the black-and-white marble floors, the leather chairs with the brass nails, the mirrors framed in gilt wood and the heavy presses and cupboards that contained, he knew, a rich store of silver, fine damask, and rolls of satin and velvet. The air was flavoured with the perfume of coffee and spice; on Persian tapestries stood carven pots holding flowers that blossomed in the heat given out by the large porcelain stove. The girl, Cornelia by name, did not look up. She took no more notice of the entry of Julius than she took of the anxious gazing greyhound that stood close to the folds of her vermilion-coloured skirt.

On the stairs he met Cornelia's mother, a woman who seemed much shut away from him.

He knew that these two Dutchwomen, who lived fastidiously on the savings of a dead professor of anatomy and their own letting of rooms to students, represented a way of life that would always be alien to him. He had lived nearly two years in their house and knew very little of them.

The older woman was carrying upstairs a bundle of cold, glossy linen. She was stout and a little bent, for she had seen much service; her strong shoulders were bowed by bending over so many cradles, so many pots and pans, so many death-beds. Julius recognized her as one who saw the will of the Lord in everything that befell her. He wished that he could gain the same serene resignation. If she had no faith in Divine Compassion, at least she credited God with great good sense.

Julius watched her as she moved into another room, leaving the door open behind her. From the oaken sideboard she took down some goblets, amber-green in colour, and, finding them without a speck of dust, returned them to their places.

Beyond the diamond-paned window behind her Julius could see the row of low, pollarded limes that bordered the canal. There, too, he saw a red fur with a lining of Roman-striped silk.

This sudden sight of Amalia von Hart had an almost overpowering effect on him. He went upstairs to his own chamber, and would have bolted the outer door had not the impulse seemed utterly childish. But evidently it was not himself that the pedant's daughter had come to see; he could hear her pretty voice, speaking Dutch with a strong foreign accent, speaking to the landlady on the stairs.

What did she want in his retreat? How had she found out about it?

Julius, lingering by his door, the key yet in his hand, overheard the conversation of the two women. Amalia von Hart was trying to obtain lodgings, for herself and her father, whose position she represented in very rosy hues.

Despising himself for eavesdropping, Julius closed the door, and, in sheer idleness, went to the window. Martin Deverent was on the other side of the canal, waiting with an interested air. He was soon joined by Amalia von Hart, who crossed swiftly over the humped bridge that arched the canal.

Julius at once felt a great tingle of anger that he could by no means understand. What was either of these people to him? Had he not resolved to put Martin out of his life? It now seemed that this was not possible; the fellow must interfere with him. Julius could not guess at his enemy's connection with the von Harts, but it was clear that there was one. He went hastily downstairs in search of his landlady, and found her standing by the door of her room with a puzzled expression on her usually serene face.

"Did that young lady come to ask after me?" he demanded impetuously.

"Do you know her?" asked the Dutch woman in surprise. "I should not have thought, Mynheer—"

"You are right," returned the young Scot resolutely. "She is not of my acquaintances—yet I met her once—and I know the man—a fellow Scot, with whom she came—"

"I did not see him. The lady came to ask for lodgings for herself and her father, who has a post at the University."

"And you had no rooms to let?"

"None," replied the old woman firmly. "Can you imagine a creature like that in my house?"

"No—but would you tell me exactly why?" asked Julius with a curiosity he could not understand very well himself.

The other replied with great simplicity:

"I have never seen anyone like that in Leyden or in Dordt, which is my native town."

"She is foreign—do you know of what race?" asked Julius.

"No. But why, sir, should it trouble you? She did not even mention your name."

Julius thought it useless to confide to this tranquil old woman the odd turn that his story had taken; for odd it appeared to him; he still could not understand why he felt so angry at the obvious friendship between Amalia von Hart and Martin Deverent. He felt that, in some obscure way, they were in a plot to make a fool of him, and that Martin's appeal in the whitewashed church had been part of this stratagem. These feelings confirmed him in his almost foregone resolve to ruin Martin.

He turned to his table and took up his law books, then turned over several portfolios that contained accounts of the various quarrels that had embroiled the family of Sale with that of Deverent, together with descriptions of the death of Kenneth Sale and the trial of Robert Deverent for his murder. He almost knew them by heart; yet there was something unsatisfactory about the whole episode, as if it had never yet been rightly told.

His mother and his friends had never doubted that Martin's father had murdered his; in fact it seemed as if the accused man had hardly attempted to defend himself. He had put in a plea of accident at the trial, certainly, but after his acquittal he had appeared to accept the unexpressed verdict of his neighbours and gone abroad, self-exiled, paying little attention to either worldly or spiritual matters. Julius could just recall the appearance of this dark man with the scowling brows, who resembled his son in so little; he had always lived like a recluse, and his wife was a sad-faced creature who shared his misfortunes with a mute constancy.

The story went—and Julius had heard it from his earliest youth—that Martin, though no more than a child of ten years or so at the time of the tragedy, had somehow helped his father, though in what way had never been made clear to Julius—either by giving false evidence in his favour, or even (for he had been present at that scene) by distracting the attention of Kenneth Sale so that Robert Deverent might shoot him as either of the men would have shot a rabbit.

This strong rumour had always nourished the hatred that Julius had felt for Martin. Other tales also had come to his ears of how Martin had boasted of the manner in which Kenneth Sale, too arrogant, too wealthy, too narrow-minded, had been disposed of as if he had been vermin.

These tales had been brought to the ears of Julius by various travellers who had met Martin unexpectedly abroad, where he would suddenly appear at some club, casino or gambling salon, always shabby, neglectful of his own interests and possessing neither discretion nor grace of manner. Many evils were imputed to his charge; the best that was known of him was his respectful wooing of Annabella Liddiard during his brief and infrequent visits to Scotland.

Turning these matters over in his mind, Julius decided that it was not, after all, so strange that Martin should have appeared in Leyden; but what had Baron Kiss and the von Harts to do with the matter? Julius, frowning over the whole exasperating situation, perceived one cause of his own annoyance; if Martin was attracted by Amalia von Hart, then he, Julius, could not irritate, slight or humiliate him by attracting the affections of Annabella Liddiard; yet Julius could not get from his mind the appeal that Martin had made in the whitewashed church, out of the shadows of the young warrior's tomb. It was difficult to believe that that was in any way feigned. Julius recalled also the gleaming half of the golden coin that had hung above the young man's faded attire.

"At least," Julius muttered to himself moodily, "the routine of my life in Leyden has been shattered. I do not see how I can get back to the lecture room—the treatise—the law book—"

Two days had surely been already spoilt; for though he was confused as to time he thought that it must be at least forty-eight hours since he had first met Baron Kiss, the man who had at first attracted him so brilliantly and who now seemed the cause of intangible misfortunes. Yet why, he asked himself, should it be a misfortune to lose a revenge, that was, whichever way one looked at it, ignoble? Julius had no answer to this question, but he felt that some powerful attraction had gone out of his life and that it would be impossible to return to Scotland and live as a landed gentleman and the husband of Lydia Dupree. At least he would go about Leyden and try to find where Martin lodged.

First he went to the Golden Standard, which was frequented by all save the very poorest students. While he ate his meal he looked about, expecting to see at least Baron Kiss, who had seemed so familiar with the place; but there was no one there he knew save some of the students he had seen in the gambling saloon, and they gave him no sign of recognition.

'Perhaps,' he thought, 'this coffee house is too costly both for the von Harts—for did not Amalia boast of poverty?—and for Martin.'

He therefore quickly finished his meal and visited several other coffee houses, some quite modest, where the students were likely to go for their hot drinks, their disputations and their readings of the Dutch gazettes.

But in none of these did he see the red fur with the Roman-striped lining, the peculiar military cap with the brilliant jewel, or the shabby clothes worn by Martin Deverent. It seemed so strange to him that in a city as small as Leyden, where there were so few places for people to congregate, he should chance not to meet any of those three that he began to wonder if all were not some trick dream engendered, perhaps, by over-attention to his studies. But against this theory, fantastic at best, was the visit of Amalia von Hart to his own lodgings and his own sight of Martin waiting for her on the other side of the canal. No, these people were somewhere in Leyden, and he, without doubt, was determined to find them.

Without giving a thought to his neglected studies, which now seemed purposeless, he wandered the wintry streets, as if, by hazard, he might find the people whom he sought. Recalling, vaguely, where he had met Martin Deverent, he turned into a church, but it was not at all like the one he had entered the evening before. The atmosphere was of great gloom, something bleak and dreary; only the windows, composed of coloured glass, filled the church with magnificence. Daylight shone through the florid designs, which were so rich that they seemed like glimpses of actual scenes between the rounded arches of the arcades. The figures, draped in veils of brilliant blues, purples and reds, moved through immense and flowing compositions and a pellucid, golden air, while the reflections of a thousand rich gems seemed to glitter.

Julius saw Cornelia, his landlady's daughter, enter the church; she carried a rush basket of flowers covered with a clean cloth. Julius then remembered, what he had never noticed before, that his rooms were kept sweet with blooms all the year round. No doubt the women had the acquaintance of a greenhouse-keeper. Yet the forced odourless flowers of winter had not made the impression on him that had been made by the displays offered by Amalia von Hart at her father's supper.

Cornelia set the basket on the floor. Dutch churches, as Julius well knew, were not adorned with anything but the beautiful glass. Cornelia began her set task of dusting and polishing, taking no heed of her mother's lodger, who sat vacantly regarding her from one of the rush-bottomed chairs Cornelia's step made a notable sound in the drowsy stillness. A large tiled stove heated the church. The girl wore a hood and cloak of pear-coloured cloth with wide bands of white fur, over a gown of lustrous grey silk; her hair, fine and pale as raw silk, was twisted in a rope like satin at the nape of her fair young neck. Julius had no interest in Cornelia and had never noticed her with detailed care before; he had always thought of her, when he had thought of her at all, as a slightly pampered child; now, as she went about the church with her duster and feather broom, she seemed like a diligent housekeeper.

Yet Julius was not really thinking of her at all, but of Amalia von Hart, who was probably nothing of a housekeeper; but he remembered the supper served at Dr. Entrick's and retracted his opinion. His vague meditations were interrupted by the appearance of the very person he had, if not hoped, at least perversely wished, to see: Martin Deverent.

"By what strange chance," he exclaimed, "do I twice come upon you in a church?"

He was indeed deeply startled, as if he had come upon an apparition at noonday. Cornelia took no more heed of the second comer than she had of himself. Martin now wore a shabby russet mantle over his worn suit.

"You disappeared yesterday before we could finish our argument."

"It was no argument," replied Martin. "Come outside and let us speak again."

They left the church; it was evening again and unclouded. They went outside the city; the sun was disappearing behind the immense distant horizon and casting long shadows that would linger until the last withdrawal of the long rays.

The distance was misted with touches of gold; here a faintly seen spire, here a bouquet of trees, here a little farm guarded by espaliers, everywhere the gleams of the waterways, the only movement the sails of a windmill quietly revolving.

"Make it possible for me to go home," said Martin Deverent.

"You know that I do not prevent you."

"I know that you evade me," replied the other. "If I could be sure that there would be no lawsuit—that Annabella would be faithful to me—"

Julius scornfully cut him short.

"You should be man enough to confront these eventualities!"

"But all the cards are in your hands," protested Martin. "You know that Annabella is much pressed by her people to accept you—and you know that winning the lawsuit—or gaining victory without one—is very likely to happen to you."

Hearing these words from the man he still disliked gave Julius a sensation of triumph.

The radiance had reluctantly faded from the landscape; but the afterglow had the same quality of clarity; purple shadows darkened the dykes; in the sombre blue-green water the stonework of the causeways and the shapes and sails of the canals were reflected, line for line, thread for thread; all was fading into darkness, but nothing was blurred. The very darkness was clear; the snowdrifts, frozen in the starved grass at the feet of Julius and his enemy, were minutely exact even in this twilight; while beyond them was the flat distance, immense, mournful, a region of immeasurable illusion of sad enchantment.

"Come," asked Julius, trying to throw off the spell of the place and hour, "how is it that you have twice brought yourself into my company in this unexpected way?"

"Surely my requests to you were made in the plainest manner?"

"Yet there is something odd about them. How did you know I was at Leyden?"

"Many people know that—it is common gossip," replied Martin sadly.

"But not my reason for being here—"

"That also is known to several—"

"Ah, you make me think of Dr. von Hart and his daughter, and that strange fellow Baron Kiss."

"What should they have to do with me?"

"That I do not know, but it seems to me as if they were the means of bringing us together."

"There is enough to bring us together without that," said Martin.

They were now re-entering Leyden. The easy, comfortable crowded city was once more about them. They passed between airy fantastic gables, houses of just proportion and elegant brickwork with a rich yet practical air; in such a house Julius lodged, and he thought of this and of how pointless was his walk with his rival; for he was resolved not to ask him into his own rooms.

"You have asked questions," he said, "to which I can give no answer. If the land you occupy belongs to me—why, I must have it. I cannot see that it brings you much. You are never in residence there—or seldom."

"It provides the few monies on which I live," replied Martin with some firmness. "Besides, if I had some hope for the future and Annabella for my wife, I should have more heart to put energy into my stewardship."

"I make no promises," said Julius, walking quicker. "I do what I like with my own and I pay court where I wish."

"If you are interested in Amalia von Hart," demanded Martin, "why cannot you undertake to leave Annabella alone?"

"You do not impress me with your stern accents and your frowns," replied Julius. "I shall do as I please."

"No doubt you are, first of all, gifted and wealthy, then you are eloquent and have the entree wherever you go," replied Martin unexpectedly. "This evening we walk the streets because you will not ask me to your lodgings; and I—who dwell in a hole in the rocks—have none."

"You are resolved to think that I hate you," said Julius; "and perhaps it is so. At least, I regard you as the heir to your father's crimes, as I have said—"

"And have not I said—pleaded—that he has paid? He died poor, in exile, under a shadow."

"I do not wish to hear all that again," said Julius. "Come, we are near to my lodging, and it is true that I do not intend to ask you to enter."

He paused before the agreeable medley of pleasant little shops, now shuttered for the evening, that surrounded his comfortable lodging.

But he added, as if against his own volition:

"It is true that you are on your estate long enough to see Annabella Liddiard and to exchange love tokens with her—"

"You speak as if that were a contemptible thing to do—"

"Perhaps I think that it is. You confess yourself ruined—you have no profession—"

Martin Deverent interrupted:

"And perhaps you would like to add that I have an evil reputation?"

"That has nothing to do with me—but I am not going to invite you into my lodgings, and I refuse your requests."

"Ah, do you, indeed? Then that means that you did intend that I should be desolate and bereft?"

"You have heard my answer."

"I should have thought that the whole affair would seem very small to you—"

"Perhaps it does—yet it is concerned with the death of my own father."

"With which I had nothing to do—"

"Some think that you had, child as you were," replied Julius. "But I cannot—will not—stand debating here with you."

"Yet you deign to spend some time with Baron Kiss, and his companions—"

"Those people!" sneered Julius. "Let me warn you that the Hungarian, at least, is no friend of yours—he urged me on to my design—"

"That of ruining me? You admit, then, that you have one."

"Not at all," said Julius impatiently. "But this stranger—who seems to have come from nowhere—has tried to urge me to make an end of your fortunes."

"Let that be as it may," replied Martin, "I dare say I can contrive to live as well as the next man. What I wanted was your promise to leave Annabella Liddiard alone—"

"You should trust her fidelity," said Julius, and closed the door in the supplicant's face.

The precisely kept, dignified house seemed in keeping with his studious days, hitherto unbroken, and the grim purpose of his life. His landlady was preceding him up the finely polished oak staircase; she had again a basket of freshly laundered linen on her stout arm; indeed, he had never seen either her or Cornelia empty-handed. Half turning, she told him that a lady waited for him in his chamber. The slow smile on her complacent face seemed to note that it was new for him to have female visitors.

Julius expected to find Amalia von Hart in possession of his handsome chamber; and it was indeed she who rose as he entered and greeted him as if she had been the hostess.

Julius rented two rooms, of which this, the outer, he used as a parlour. It contained a chance medley of objects as well as the cases and shelves of all the law books that he used in his studies. There were some brass lamps, kept cleaned to a milky whiteness; one of the windows was occupied by a seascape painted on three panes of glass, set, one behind the other, in a grooved frame; the effect, being before the light, was of a luminous green under gold, and Julius had often half-desired to make such a toy for himself.

"Why do you bother yourself with my affairs?" he asked Amalia.

"Oh, I have been amusing myself. I was looking from behind this pretty trifle and watching you rebuff the poor shabby wretch who still, I see, stands below."

Julius also looked into the placid yet gay pageant of the street. The little metallic warrior was coming out from his tower opposite and about to strike the half-hour chimes.

"There is no getting away from the sound of bells in this country—"

"And no getting away from the sight of your enemy, eh?"

"Oh, I had not seen him for a good number of years, and I shall soon miss him again," replied Julius carelessly.

"But you have been thinking of him a great deal—"

Julius laughed in her face.

"Again I ask you what has this story, that somehow, I suppose, you wheedled out of Baron Kiss, to do with you?"

He seated himself opposite her, thinking how radiant she looked in her red fur, her face flushed from the frosty weather.

"My father and I were at Drenthe lately," she said. "It was on our way from Pisa to Leyden. My father wished to find some rare bog flower; this province, as you know, is a sandy heath. He stayed at Assen and found the people dull and obstinate—" She stopped.

"Yes?"

"It is a haunted country, covered with prehistoric monuments that appear to mark the graves of giants or some such monsters—"

"Hardly the place in which to look for a flower," remarked Julius impatiently.

"Oh, but it is—and we found exactly the variety we searched for—in that sterile plain outside the old capital, Koevorden, that is now no more than a hamlet—" She looked full at Julius, and added, "It is a mean-looking white bloom."

Julius pictured with some distaste the stretches of stagnant marsh which father and daughter had wandered searching for an insignificant flower. But, no doubt, he thought, such meagre triumphs were among the glories of his dull profession.

"But none of this," he said aloud, "affects me and my affairs."

"Yes, it does, for it was at Koevorden that I met the wise woman. There are several such, living on memories of the past and inheriting some of their magic—"

"I believe nothing of that," replied Julius quickly. "You waste your time."

"Oh, that, very likely!" she conceded. "But do not be so disdainful—think a little what the word magic may mean. I do not talk of changing the weather by the beating of a Laplander's drum."

"Tell me what you do mean?"

"Suppose someone dwelt on one idea only—from infancy upwards—do you not think that that might become concrete, so that, instead of thoughts, figures might appear?"

Julius laughed; the suggestion seemed to him nonsense; he believed that Amalia must have some secret purpose in making it.

She saw his incredulity and, rising, asked him to go with her to the wise woman, who was now in Leyden, and who might have something strange to show him.

"Whatever it is," replied Julius, "she will not be able to persuade me that I am surrounded by apparitions, not human beings. But I do not think," he added, stayed by an unexpected thought, "that I have a mind to go out; Martin Deverent may still be there."

Amalia peered behind the glass seascape.

"No—he has gone—do you think he has such faith in your tenderness?"

"It is very odd that I should meet him like this in Leyden—playing the organ in some silent church."

"He wanders all over the place."

"The stranger that I should not have met him before. I had no idea that he was so strongly attached to Annabella Liddiard—"

"And to that piece of ground he calls his own. Come, will you make this visit with me?"