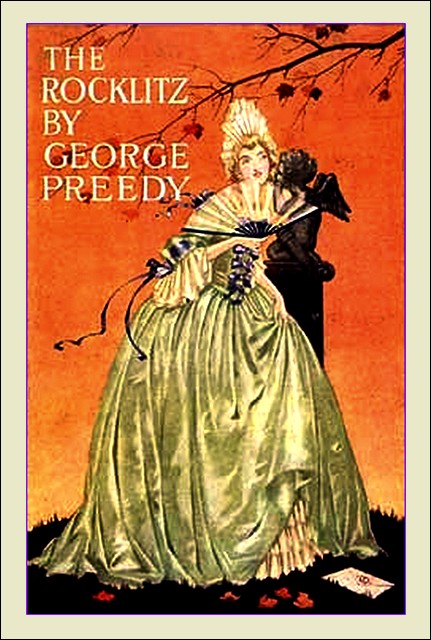

"Leda" by Micheli di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio

In the Preface below, the author recounts, that "the Italian piece of which Johann George IV was enamoured is extremely like the lady. This one-time ornament of the cabinet of the Elector of Saxony (of the Wettin line) is now in the Borghese Gallery, Rome; it is named 'Leda' (foolishly, I think) and given to the chronicler of the ways of genius, Giorgio Vasari...to look at this picture, I am told, is to look at the face of Magdalena Sibylla von Neitschütz...this I can and like to believe."

The painting had been attributed to Vasari however, in the catalogue of the Borghese Gallery, published in 2000, it is stated that the work is now ascribed to Micheli di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, who worked as Vasari's assistant.

The Rocklitz, John Lane/The Bodley Press, London, 1930

THOSE who would care to find what learned men have made of the story of Magdalena Sibylla von Neitschütz can satisfy themselves by turning to Geheime Geschichten (Vol. III) by Bülau, but her contemporaries and my friends, Sir William Colt, George Stepney, Thomas Burnet of Kennet and the great Baron Gottfried Leibnitz, have assured me of very different circumstances from those Bülau records; I think, though they are very guarded in their expressions, that my friends had some compassion and even admiration for this brief luminary; they are not at all averse to her story being told again; they (and especially the relative of the Bishop of Salisbury) were exasperated by Bülau's omission of the account of her two brothers and, how, they ask, could he have confused Françoise de Rosny with Ursula Margaretha von Neitschütz, who died when her daughter was an infant?

These gentlemen have helped me search the galleries of Europe and the portfolios of collectors for a portrait of Magdalena Sibylla; they were very anxious that it should be realized how very beautiful she was; Sir William Colt can remember a portrait of her that she gave him for the King of England, which he sent through the Earl of Portland...We found nothing.

They were vexed...can the dust lie so thickly on what was so burningly radiant?

Those who knew her are surprised that she should be so soon forgotten, but I reminded them that it was all gone like a flash of wildfire...and that others as notable as Magdalena Sibylla have met the complete defeature of Time. Sir William, however, assures me that the Italian piece of which Johann George IV was enamoured is extremely like the lady. This one-time ornament of the cabinet of the Elector of Saxony (of the Wettin line) is now in the Borghese Gallery, Rome; it is named "Leda" (foolishly, I think) and given to the chronicler of the ways of genius, Giorgio Vasari...to look at this picture, I am told, is to look at the face of Magdalena Sibylla von Neitschütz...this I can and like to believe.

The shadow of the Koenigsberg falls heavily across these pages; this terrible prison is not one with the awful fortress of Koenigstein (some miles from Dresden), but a gloomy and sinister building that was destroyed soon after the internecine struggle on the plains of Leipsic. Sir William Colt and George Stepney, who used to pass it daily (or see it daily), have care fully described it to me; the château at Arnsdorf and the cottage on the Bächnitz road have both disappeared; vineyards grow over the sites; but the Marienkirche remains, and that is not without its memories of this tale; I have seen also the MS. of a Rondo alla Turca, by Delphicus de Haverbeck and much ad mired the delicate, neat scoring.

In the "Grüne Gewölb" in Dresden can still be seen many of the treasures with which Fräulein von Neitschütz adorned her apartments and her person, among them the golden egg with which she bought such tragic wares; I believe that Baron Leibnitz was thinking of this story when he wrote:

Nothing is lost, according to my Philosophy; and not only do all simple substances such as souls, preserve themselves, but, what is more, all actions remain in Nature, however transitory they may appear to our eyes, and all the foregoing enter into all the subsequent ones.

The tale proves, at least, an apt illustration to the dictum, for here we see one action breed another, and a deed of dishonour increase in its consequences till it has poisoned and blasted the young, the brave, the lovely, like the late sharp snow and frost of April, 1693, blighted the fruit trees and vineyards on the banks of the Elbe, along the Bächnitz road, and near Château Arnsdorf.

THE AUTHOR.

"What win I if I gain the Thing I seek?

A Dream, a Breath, a froth of Fleeting Joy?

Who buys a minute's Mirth to wail a Week?

Or sells Eternity to gain a Toy?

For one sweet Grape who will the Vine Destroy?

Or, what Fond Beggar, but to touch the Crown,

Would with the Sceptre straight be Strucken Down?"

(The Rape of Lucrece, WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE.)

"And yet," says he, "I dare engage these creatures have

their titles and Distinctions of Honour...They make a Figure in Dress and

Equipage, they Love, they Fight, they Dispute, they Cheat, they Betray!"

(A Voyage to Brobdingnag, JONATHAN SWIFT.)

The children were sporting round the fountain, trailing their hands in the water that completely filled but never over-brimmed the basin of greenish stone, throwing bright balls through the tall jets which overturned it veils of spray, and floating small paper craft on the confined tides made by their lusty rufflings of a surface they had found placid save for the falling drops re turning to their source. Behind the fountain was a hornbeam hedge, twice the height of a man, behind that a level row of wych-elms, three times the height of a man, each pruned, clipped with nice topiary art; this double screen of green kept the descending September sun from the group of children; they frolicked in a mellow shade. From a stone bench before the hedge a youth watched them; the four boys did not appear to know that he was there; but the one girl looked at him now and then with kindly candour, and he smiled in response.

It was the close of her birthday festival; she was garlanded, over the knot of fine muslin that formed her cap, with a wreath of buds and blooms in seed pearls and silver; her tight-laced gown was, instead of the usual brown or grey, a pale azure satin; her little shoes were new and fastened with ribbons with gilt tags, her tiny neck was encircled by the heavy glitter of her dead mother's diamonds, a slight string, but too sparkling for her; she was twelve years old; she ruled her four companions, directing their games, exacting her own desires, insisting on her own pleasures, but gently, with caresses and soft appeals.

When she glanced towards the young spectator, idling with his fingers in a book, she seemed to seek his applause of the skill with which she managed her little empire, and even to invite him to become of the company of her slaves.

But he was eight years her senior and grave; he paid no tribute to the charms and graces of the child who appeared on the verge of becoming a grown maiden; who was so delicious, so soft, delicate and fine, whose ribbons were already knotted with such coquetry, whose apron was tied to show off her waist, whose gala skirts gleamed over prettily chosen laces, whose every pose and look and action revealed uncommon beauties and the most sedulous training. Two of the boys, eagerly watching the wreck of their paper boats in the splashing spray, were her brothers; handsome, noisy lads over whom she had an easy mastery; her tender arts were directed to her guests, one of her own age, one younger, who jealously competed for her esteem.

She sat on the edge of the fountain and trailed the tips of her fingers in the water; she was wetted with the spray, crystals of water hung on her attire, on her rosy face, brighter than the little diamonds round her neck; she was very fair; her head showed a glimpse of silver-gold from piled-up curls through the meshes of her cap; her eyes were a clear light brown, that her lovers, with an easy conscience, would be able to call gold; she was as neat, as exact, as charming, as some little doll on whom a great lady had bestowed all the luxury and elegance of her rich leisure.

The governess came round the hornbeam hedge; the young man rose from his bench and looked at her with distaste; he thought that her presence darkened this hour of delicious sun shine, of laughing play, of careless idleness.

Bowing, he acknowledged the presence of Madame de Rosny, who curtseyed formally, saying slowly:

"It is rather chilly, is it not, Monsieur de Haverbeck? And I think the children have played long enough with the water."

She was a woman of a notable deportment; it was easy to see where the little girl had learnt her air of breeding and decorum, who had trained her to wear her fragments of frocks with an air, to step lightly, to allow no shrill note in her voice, to be at once proud and affable, dignified and caressing—Madame de Rosny was extremely competent in all these matters; a widow of forty-five, her studied elegance neither disclaimed poverty nor assumed riches; her discretion was unfailing, her tact perfect; she knew her place and her value; though, in this house-, hold of a widower, her authority was supreme; she had never vexed the most truculent by the exercise of it; her well-featured face was composed to a refined negation of all the passions, but her figure, not ill-displayed by her simple russet taffetas, was voluptuous; Delphicus de Haverbeck, the youth who had risen at her approach, had always detested her; he was surprised that she lingered to speak to him, surveying him from cool eyes, choosing her words with precision.

"I have scarcely seen you since you returned from Paris. You were diverted, instructed?"

"Both, madame."

"You find Saxony dull?"

"No, madame."

"You are entering the army?" She continued to study him with a gaze of chilly experience, for he was extremely hand some.

"Yes, I have my fortune to make." He was as cold as she; though he was twenty years of age he had none of the hesitancies, crudenesses, or discomposures of youth.

"Ah, yes." Her smile was thin, her scrutiny more persistent. "You are changed, eh? Five years ago since you were playing with these little ones. They, too, have changed—Clement, Casimir—they, too, begin to talk of the army, of making their fortunes"—her sneer vanquished her smile—"a pity, mon Dieu, that the House of Neitschütz has not more money!"

Delphicus de Haverbeck turned away; he realized that she suspected he had heard much to her discredit in Paris; she would not be greatly concerned at that, he thought, for she was independent of her reputation, but it could make her cynical, indifferent to her usual disguises of propriety and prudery; she spoke again, to his averted face, for he was gazing at the children by the fountain:

"And the little Madelon, do you not find her changed too? Very pretty, very accomplished; I can claim some credit there—observe her now with the little Princes, they are quite her subjects. Johann Georg adores her, eh?"

"I have been watching that," said Delphicus de Haverbeck indifferently; "they have been much together."

He faced Madame de Rosny as he spoke and she resumed her gaze; he was certainly extremely handsome.

"A great deal—here and in Dresden, he was very shy, timid, gauche, eh? And my little Madelon has done more than all his tutors to improve him—the Elector is very grateful."

Haverbeck returned her challenge so steadily, with such assurance, opposed so disdainful a silence to her mocking words, that she was reduced to vexed laughter.

"You have certainly learnt something at Versailles," she said, detesting him, then walked meekly to her charges, with curtsies for the little Princes, with gentle commands for the others, with the softest of rebukes for wet ruffles and damp ribbons.

When she had joined that gay and innocent company, Haverbeck found no pleasure in contemplating it; he walked slowly across the small well-kept gardens to the small well-kept château, everything was slightly pretentious; Haverbeck knew that a considerable effort was behind this restricted display of pride, parterres, terraces, statues, ornate gateways, massive coats of arms in stone above doorways and windows; and, to the young man returned from the wide magnificence of Paris, of Marli, St. Germain and Fontainebleau, it was all provincial, rather mean; yet dear and familiar, for he had passed a not unhappy childhood on this estate with those three companions much younger than himself, now sporting by the fountain; he was their second cousin, better born, early orphaned, possessed of the most meagre of fortunes and the most steadfast of ambitions; his handsome bearing and his cool assurance had gained him five years in the family of another relative in France, but his poverty and his foreign birth had closed channels of advancement in Paris and he had returned to Saxony and a lieutenancy in the army of the Elector; he was not perturbed by the thought of the future, nor indeed by anything whatever.

As he reached the château he saw Major-General von Neitschütz on the terrace with the Elector—in close obsequious attendance on His Highness, who was stupid, easy, gross, the father of the two blond boys playing with little Madelon von Neitschütz, and one of the highest Princes in the Empire.

Haverbeck pitied the proud, hard, grasping man forced to supplicate the favour of one in everything but rank his inferior; Neitschütz must consider this visit as the greatest honour, must demean himself with grateful humility because his daughter's festival was thus graced; and Haverbeck knew that he really despised the Elector and bitterly considered himself vilely used by him, because he had saved his life at Seneffe and had never been rewarded; Haverbeck, who was as intelligent as he was handsome, also knew that this neglect was owing to the influence of Count Stürm, who completely governed the Elector and hated Neitschütz. When Haverbeck had been an inmate of Château Arnsdorf his youthful shrewdness had noted the tenacious struggle, stern, bitter, exasperated, of Neitschütz to maintain his influence with the Elector, to oppugn the cold hostility of the minister, Count Stürm, who would tolerate no rival or colleague in the cabinet at Dresden. Neitschütz, harsh, soured, unattractive, aggressive and passionate, trained in the camp and harassed by poverty, hampered by a family, with no merits beyond his high birth and the energy of his tormenting ambition, had never been able successfully to combat Stürm—subtle, amiable, pleasing, artful, schooled in diplomacy, wealthy and childless; with no responsibilities to harry him, with no embittered passions to torture him, a cool, able, experienced man who had made himself indispensable to his Prince and who had without difficulty thwarted the pretensions of Neitschütz. If, at this moment the Elector honoured Château Arnsdorf it was, no doubt, because of the lovely charms of little Madelon who had fascinated his dull and awkward Electoral Highness into a more manly temper...Haverbeck wondered what Count Stürm thought of this development.

The September sunshine gave an air of sweet laziness to the prospect, to the formal gardens where the more delicate trees were thinning in their foliage, to the solid grey façade of the château, to the empty walks and seats; the air was soft, still, the sky veiled with radiance; Haverbeck found some enchantment in this jocund peace; he lingered on the narrow terrace, evading Neitschütz and the Elector who were discussing glass-houses and the merits of the yellow diamond or jargonelle pear; Neitschütz was tall, of a grand, imposing presence, overbearing and severe in his stiff uniform, a man of fifty with heavy features and eyes still golden bright beneath scowling brows, subdued and bent to complaisance and flattery, servile and forcedly courteous to the Elector, whose clumsy person only came to his shoulder, whose wide, flat, red face, with snub nose and loose mouth, clouded eyes and narrow forehead, expressed only stupidity, obstinacy, vanity and a vague good humour.

"I," said Haverbeck to himself, "will not rise by any such means as that—how disgusting to cringe for favour!"

He heard the laughing, quarrelling protests of children coming across the garden; he entered the mansion and, in a vestibule crowded with sham Roman bustos, paused and reflected:

"Where is there one simple honest soul who will tell me the truth?"

He recalled Agostino Steffani, the overworked, insolently-treated tutor, an ill-paid, timid man—patient, industrious, ingenuous, from whom Haverbeck had learnt much; he had made a hesitant appearance at the beginning of the festival when he had handed Madelon a little gift of books; since then no one had seen him or missed him; Haverbeck went to the library where he had studied all his own early lessons and there discovered Signor Steffani feeding some caged linnets with millet seed.

This room, where Madame de Rosny never came, that was occupied only by the gentle pedant and the children, had a far more genial air than the other departments, formal and gaudy, of the château; Haverbeck was pleased to return to this chamber where in five years nothing had altered save to become more shabby, and of which he had warmly affectionate memories; the youth had only loved two people in Château Arnsdorf, and one of them was Maestro Steffani.

The little Italian trembled with gratification at the gracious visit and the gracious greeting of the splendid young man; modestly as Agostino rated himself, he was treated even beneath his own valuation; he had an enemy in Madame de Rosny and knew that Neitschütz only tolerated him because his services were both excellent and cheap; his mild, gentle, sensitive soul took refuge in music, in books, in birds...not in cages, however, the linnets were prisoners of necessity, because little Casimir had snared them and cut their wings...

Haverbeck sauntered round the familiar room; there was the old mappamondo, yellow, crinkled; there were the thumbed Latin and Greek volumes snug on the deep shelves; he took one from its place, opened it and read his name on the fly-leaf, eh, the pride with which he had written that—ten years ago...

"Delphicus Secundus Hyacinthus Lüneburg de Haverbeck, 1674."

He laughed, and Steffani, regarding him with humble delighted admiration, laughed in sympathy; the rich honey-yellow sunshine filled the dark room, showed up the dusty, worn chairs and tables, the rubbed books, the blackened portraits of members of the House of Neitschütz that frowned above the shelves, and on the spruce slenderness and glowing beauty of the young man who had yet all the bloom of the very May of life; he was tall, healthy, dark, alert, yet composed; serene, not placid; self-assured, not vain; his features were of a notable exactitude, and the long, fashionable, carefully-dressed curls, black save when in the sunlight, that hung on to his shoulders, added to his modish elegance; the Maestro thought him marvellously delightful to behold—always had Haverbeck been his favourite pupil. Casimir and Clement were wilful and stupid, while he did not enjoy teaching girls, and Madelon was disconcerting; she impinged on his studious quiet, she involved him in a world from which he had long since withdrawn.

Haverbeck glanced again at the fly-leaf of the Germanicus Tacitus, a name was scrawled in an uncertain childish hand beneath his own:

"Magdalena Sibylla von Neitschütz—Madelon—"

Steffani, peering over his arm, said:

"She writes better than that now, she writes very well, she does everything very well."

"She has been precisely trained," answered Haverbeck, "she was always intelligent."

The meek pedant extolled Magdalena Sibylla—her quickness, her energy, her aptitude for all manner of learning, her eagerness for Greek and Latin, her gift for music, her deftness at the embroidery frame, in the dance, her superiority to her brothers.

"There," put in Haverbeck, "is the sting for my uncle. The boys give no great promise."

Steffani shrugged and grimaced.

"Clement is mediocre, Casimir is lazy, he does not tell the truth—they are both selfish and hard. General von Neitschütz pampered and indulged them, as you recall—"

"At my expense," smiled Haverbeck. "He gave a sharp edge to all his favours to me."

"I recall there has always been an element of bitterness in this house, no one has been really happy here; now that the boys disappoint his expectations the General is harsh with them and they defy him with insolence until he subdues them by force."

Haverbeck returned the Tacitus to the shelf and glanced idly out of the window at the garden and the fields beyond, shimmering in the autumn sunshine.

"What part has Madame de Rosny in this?" he asked.

"With the boys—no part," returned the pedagogue uneasily, "they have outgrown her care—"

"But Madelon, eh?"

"Madelon is Madame de Rosny's especial charge; she has taught her a great deal."

"Not too much, I hope."

Steffani was silent, he opened the harpsichord that stood before the window and looked at the double keyboard as if he took comfort from the face of a friend; not for long could he keep from some manner of music; there was a flute in the room, a violin, and an ancient table virginals painted with cracked and faded flowers.

"I heard," added Haverbeck, "something of Madame de Rosny in Paris—her reputation is as decayed as her family."

"She is well-bred. She offends no one."

"Has she great influence with my uncle?"

"Eh, well, she has been with him since his wife died—ten years."

"Madelon always in her hands. When I lived here I did not understand."

"That is better," said the Maestro wistfully. "There is no scandal—the strictest decorum—better not to understand."

Haverbeck looked at him.

"What shall we think of a man who allows his mistress to educate his daughter? A corrupt woman when he found her among the camp followers in Brussels!"

"Hush, that is not known here."

"I know it. I thought today Madelon had some glances that woman had taught her."

"No, no." Steffani was troubled, vehement; he gazed at the yellow keyboards; the old ivory, cracked and stained, was the colour of his own long, pallid, wrinkled face under the black cap. "Madelon is brought up in the sternest honour, she has her father's sole attention now he is disgusted with the boys; Madame de Rosny stays largely because she knows how to train a gentlewoman."

Haverbeck interrupted sternly:

"Madelon is twelve today, in a few years she also will understand—what then?"

"Then Madame de Rosny will go. She ages, and he is almost tired of her."

"Turned off with a month's fee in her pocket and hatred in her heart? He'll do that? Vile and mean!"

"You know Neitschütz," said the Maestro uneasily. "He has no tendernesses, he is devoured by this ambition—an odd passion to me—to rule Saxony, to be in Count Stürm's place—"

Haverbeck once more interrupted:

"How is Madelon to help him to that?"

"Well, the Electoral Prince has taken a violent fancy for her, when he was sick he would not eat till she was brought to him, he would not do his lessons till she helped him, I have had them here, morning after morning, he has some parts and she can strangely stimulate him, he grows to lean on her. It is not," added the old man shrewdly, "only the dawning passion of a youth for a maiden, it is the domination of a strong mind over a weak one."

"Does my uncle dream of a marriage?" asked Haverbeck.

"I believe he stakes on it; he knows the boys will never do anything, but she—she will be, no doubt, a wonderful creature."

"But a marriage with the Electoral Prince—it is absurd. Count Stürm would prevent it, even if the Elector was persuaded."

"I do not know," answered the Maestro wearily. "I stand apart in this house, but I cannot evade what comes before my eyes. For years have I watched the General struggling for advancement, blocked by Stürm, and seen him drop deeper into difficulties, I know the shifts and economies that go on here, his estate of Gaussig is sold and that of Diemen mortgaged—all gone on flourishing at Dresden in the winter then the money spent on Madelon these last few years since he saw she was to be a beauty—dresses, horses, dancing masters, jewels, even, and sometimes hardly enough on the table and the servants unpaid—"

Haverbeck interrupted:

"Madelon was a noble-minded child—has all this changed too?"

"I do not know. I cannot read her, she is very gay and courteous, but as ambitious as her father, and avid for pleasure and luxury."

"Madame de Rosny cannot have taught her honour," said Haverbeck sadly. "An ambitious woman! That has an ill sound."

Steffani explained himself as if he feared he had been less than fair to his pupil.

"She is exceptional—clear-headed, alert-minded, full of energy and resource, born surely to rule and sway other people; she has already great control; her passions are well under—"

"You mean that Madame de Rosny has taught her duplicity?"

The Maestro had no answer to this; the haze of warm sunshine had faded from the room, leaving it dark and chilly; the heavy bookshelves receded into shadow and the portraits of the members of the Neitschütz family were no longer distinguishable from their frames.

"Talk of yourself," said Steffani, rising. "I hoped you would find some opening in Paris."

"I might have, through the women, but I will not succeed by favour of another man's mistress. There will be war soon and I shall do very well."

"Another war?"

"Nothing else is talked of in Paris. Everyone is tired of the peace, which gives no opportunity to a gentleman."

"You are staying here?"

"If at all, only for tonight. I must go to Dresden for my uniforms, and to join my regiment."

Steffani regarded him wistfully and regretfully; so many brilliant advantages of mind and body, a birth so ancient, to win no more than a lieutenancy in the Life Guards...But the young man seemed neither disappointed nor dismayed; he said affectionately:

"You have worked very hard here, Maestro, and been neglected. When I have established my fortunes I will take you into my service, and you shall be my virtuoso—you know how I love music."

Steffani was greatly moved by this generous offer, even though it came from a penniless subaltern; he seized and caressed the young man's slender hand.

"No doubt," smiled Haverbeck, "my uncle will turn you off as well as Madame de Rosny, but I will provide for you; in a few years I shall be able to do so."

"I don't deserve that," said the poor pedant, "I never did much for you."

"Everything! I never forgot what I learnt from you—"

"You were such an excellent pupil." Steffani sighed, thinking of Casimir and Clement. "You had a wonderful head for mathematics—you've kept that up? Indispensable for a soldier."

"I have taken great care to equip myself at every point," Haverbeck assured him. "I also have my ambitions. Now, patience, dear Maestro, and rely on me. Write to me sometimes at Dresden."

"I will, I will—I shall be honoured."

Haverbeck clasped the old, chilly fingers in his warm grasp, then said, thoughtfully and earnestly:

"Watch over Madelon—do what you can."

The old pedant answered sadly:

"I will do what I can. It will be little."

"Instruct her in honour at every opportunity. I know she has a noble heart."

Haverbeck heard, as he left the library, voices from the courtyard, glanced through a window on the stairs and saw the Electoral coach and escort preparing for departure; he joined the group in the entrance hall; Major-General von Neitschütz was taking ceremonious leave of the Elector; he had an air of exasperated triumph, as one who has succeeded at the cost of infinite fatigue; Madame de Rosny had Madelon by the hand; she effaced herself gracefully; her russet gown was one with the background; imperceptibly she put the child forward; it was Madelon's turn to take leave of the Elector; as the little girl advanced Madame de Rosny whipped off her cap and coronal; a multitude of tiny curls, a paler gold than her bright eyes, fell on to her delicate neck and shoulders; Haverbeck, watching, bit his lip. The Elector paused; Madelon was directly in his path; illuminated by the last warm daylight that fell through the open door, her face was softly flushed, her eyes, her hair, her little satin frock, gleamed; she was all brightness and grace, airy, exquisite in her radiant innocence and candour; she curtsied in the prettiest fashion and thanked His Highness for his gift of a crystal box and his presence at her festival.

The Elector smiled, patted her head, touched her chin, was gracious, nodded at Neitschütz, agreed she was charming, charming; the Electoral Prince, blond, emotional, not ungraceful, with something of his father's flat, wide features, yet comely, took reluctant farewells and with agitation begged for a kiss.

Madelon gave him her hand; the Elector vowed, laughing, that she had been well taught; he delayed his going to stare at her; she bent to his second son, Frederic Augustus, a beautiful child of seven, and lavished on that baby face the caress she was now old enough to deny others; Haverbeck observed her lovely endearments, her delicate kisses, as the laughing boy nestled to her throat and bosom—frank innocence?—he glanced at Madame de Rosny, obscured in the shadow.

The Electoral party went into the courtyard; His Highness in one coach, with outriders, running footmen and an escort of Uhlans; the Princes in another with governor and tutor and pages. They rattled out of Château Arnsdorf and along the Dresden road, clouded with dust, with the misty gold of the setting sun. Neitschütz had remained in respectful attitude on his own threshold until the coaches were out of sight; when he returned, heavily, to the hall, he found Madelon talking to Haverbeck by the stairs, thanking him for the gift he had brought from the Palais Royale.

"But Madame de Rosny says I am too young for fans."

Her father passed between youth and maiden.

"Everyone has gone now, Madelon. Go to bed. I'm tired—amusing fools...Give me the diamonds."

The child put her tiny hand to her throat. "Can I not keep them? Are they not mine, now?"

"No, you are too young. Take them off."

"The best of all my gifts," sighed Madelon; she eyed her father coldly. "I never thought you meant to take them back—"

"Do as you are told. They are valuable."

With no further protest Madelon resigned the glittering string. "Some day," said Haverbeck gently, "you will have many diamonds, Madelon."

Neitschütz glanced at him sharply.

"No doubt but she will. Go to bed, Madelon. You have had a pleasant day?"

"Yes, my father," she curtsied. "Good-night, Cousin!"

She approached Haverbeck; he would have saluted her hand, but she offered her cheek; as the youth kissed her, Neitschütz exclaimed harshly:

"What is this? Your hand was good enough for the Prince, eh?"

"Delphicus," smiled Madelon, "is my cousin."

"Well, well, take her away, madame, take her away."

Madelon tripped up the wide stone stairs, a gleam of lightness, of brightness; her candid laugh was heard when she was out of sight; the Frenchwoman, discreet, silent, followed her like a shadow.

Neitschütz turned a frowning scrutiny on the youth who remained as if waiting for some important event to take place.

"May I have five minutes of your time, sir?" asked Haverbeck.

"Not tonight. I'm fatigued—that tedious fool—how much more of it, eh? Count Stürm never came, you noticed that? No greetings, no message, no gift! A studied slight—you noticed it?"

"Yes. I must beg you to listen to me, sir; I leave early in the morning."

"What's this?" Neitschütz turned to stare down this impertinent insistence—five years ago he had dealt sharply with a boy; but Haverbeck was of his own height and his own arrogance now, and stared back; Neitschütz laughed roughly. "So you've grown up, eh? Well, come and say what you've got to say, but I can't help anyone, much as I can do to keep my own head above water."

"Sir, I am well aware of it."

Haverbeck followed his ungracious host into the little cabinet where, as a child, he had never been allowed to enter; it was off an antechamber with a small bedroom attached, and a private stair with a privy garden; then it was dark, for the small window looked to the east; grumbling, Neitschütz found the lintstock and lit the common thick candles on his bureau; their yellow light revealed that there was nothing of value in the cabinet; all was used, mean and scant; but, above the bureau, was a pretentious picture by an indifferent artist showing the two heirs of the House of Neitschütz in Roman draperies over plate armour, with their hands resting on plumed helmets and their handsome, but insipid, faces gazing at a huge coat of arms quartering Neitschütz, Diemen, Arnsdorf, Gaussig, and Schlaugwitz. On the flamboyant scrolled frame were their names in full: Casimir Ulric Otto and Clement Philip Mathias.

Neitschütz dropped with a groan into a great, wide, stout chair that easily accommodated his massive weight, loosened his stiff collar and cravat, and glanced at Haverbeck through the thick fluttering candle-light; that youth had already seated himself, a fact that the elder man had sourly noted but could not resent; Haverbeck was of the higher rank.

Neither spoke; the large hands of Neitschütz grasped the arms of his chair, his body relaxed, his chin sank on his breast; he gazed steadily at his guest.

And Haverbeck gazed at him and found little to admire.

Major General Rudolph von Neitschütz, Lord of Diemen, Arnsdorf, Gaussig and Schlaugwitz, descended from one of the most ancient families in the Empire, had a powerful, well-proportioned frame; tall, heavy, he was yet erect and free from clumsiness; his features were good but harshly marked with lines of temper, gloom and bitterness; his face revealed that he was a disappointed man who had taken the betrayal of his hopes heavily; it revealed, too, that his intellect was superior to his character; an able, if cynic mind, a cool judgment, a keen purpose showed in those gold-brown eyes, but they were clouded with malice and shadowed by frowning shaggy brows; he disdained the perukes then becoming fashionable and his coarse brown hair, lined with grey, hung straight on to his powerful shoulders.

He suddenly turned from staring at Haverbeck, shot out a hand and pulled towards him a bottle that stood ready on the bureau.

"You drink ratafia now, eh?" He drew the glasses from among his papers and poured out the rum arrack. "You're back, eh? Why the devil didn't you stay in Paris? There is no opening here."

"And none in Paris that I cared to take."

"Fastidious! My God! What do you think you can do for yourself?"

"Everything."

"A crowing cock already! What have you got—a lieutenancy in the Life Guards?"

"Yes."

Neitschütz drank the rum arrack.

"Don't come to me. I'm burdened. Look at me! The boys are fools. What is it going to cost to push them on? Casimir will have vices he can't pay for; Clement has no stomach for soldiering, and that damned Stürm will baulk them at every turn."

"Perhaps I shall be able to help my cousins." Haverbeck spoke without ostentation as he spoke without faltering. Neitschütz regarded him with spiteful contempt.

"My God! What do you found your hopes on? Some trollop of a woman taking a fancy to your baby face and persuading her keeper or her wittol husband to pass you up?"

"No," replied Haverbeck, unperturbed by this brutality, "I prefer to choose my own women—and not because of their influence."

"You're cool. You've learnt something, eh? Let's look at you."

Neitschütz snatched up one of the candles and waved it across the person of his guest.

"Well-cut coat, good cloth, costly lace, a finer shirt than I could even afford—and how much a year?" he sneered. "You're spending above your means now—a body servant, too, in livery, and a handsome horse—don't come to me, my hands are full." He hated the young man who had never been afraid of him, or deferred to him—hated him because he was exactly as he would have wished his own sons to be, because Stürm praised him, because he was brilliant, beautiful and clever. Haverbeck did not flinch from the savage scrutiny, the waving light.

"I have not come to concern you in my promotion, sir. I can look after that. I shall be a Major-General by twenty-five—or dead."

At this mention of his own rank Neitschütz flamed. "And I'm no more at fifty! I laugh, my God, I laugh! A pranking boy! I thought better of your wits."

"Don't laugh, sir. I'm not a fool, I have even some ability and I've worked hard; my mother was of the House of Lüneburg; they have some influence."

The youth spoke coolly and this further angered Neitschütz.

"You're sly. I remember you. Getting up to try horses and wrestle with the grooms when my boys were abed; sitting up over your books with that worm-eaten scarecrow, Steffani, prying into everything—you had to excel, didn't you?—the best shot, the best fencer, Greek and Euclid, too—bah!"

Haverbeck kept his temper and without difficulty.

"I admit as much. As you remind me, I have my way to make—an orphan without a fortune."

"Do you think your accomplishments will help you—these days? With a man like Stürm in power? You don't impress me either—if you were in my regiment I would pass you over—too much a damned Adonis; find some blousy Venus to help you on."

Haverbeck faintly coloured, but kept his composure.

"There will be war—in a year or two, and my chance, not, sir, in your regiment."

"Eh?" Neitschütz banged down the candle, sputtering the wax over his thick hand. "War? You heard that? In Paris?"

"Yes."

"War—between whom?"

"France and the rest of the world. We shall fight with France. Stürm is decidedly in their interest."

"In their pay, you mean, a cursed venial wretch, a tricky, double-dealing liar!" The saturnine countenance of Neitschütz became more sombre, his fingers fidgeted on the arms of the chair, he jerked an eyebrow to glare at the youth. "What did you want with me, eh?"

"A little patience and some courtesy," replied Haverbeck, serenely. "Your temper, sir, is soured; that may be as great an obstacle to your progress as Count Stürm's intrigues."

"Your damned impertinence—" Neitschütz roared, checked himself, and snapped, "I always disliked you."

"I know, sir, I was never happy in your house...and I am sorry," Haverbeck spoke with sudden softness, almost tenderness, "for I am here to ask for the hand of your daughter, Magdalena Sibylla."

To Neitschütz this was the incredible; his coarse face quivered, his lips sneered, trembling on inadequate furies; the youth continued gently:

"Consider, sir, my offer. In a few years I shall be able to afford a wife and then Madelon will be marriageable—consider that I am your superior in birth, healthy, not a fool, not vicious, well educated and ambitious; consider, too, that I shall be content to waive the dowry you will find very difficult to provide for your daughter."

"Consider," stuttered Neitschütz, with clumsy sarcasm, "that you are a penniless young braggart of a lieutenant whom I don't like, whom I don't believe in, and that I have other designs for my daughter—"

"The Elector's son?"

"No less. And, if you knew, where the devil did you find the infernal impudence to put yourself forward?"

"I thought you might, sir, see reason. Madelon will never marry the Electoral Prince."

Neitschütz writhed; this struck at a secret, horrid fear.

"It was as good as promised me today, the Elector—stupid as he is—sees the prize in Madelon, the Electress is agreeable, the boy already her slave—"

"And Count Stürm?"

"Blast Count Stürm!"

"Exactly. But he governs the Elector and he will never permit a marriage that will put you, his enemy, in power and be his own ruin."

"It would, it would," cried Neitschütz, pouring out another glass of rum arrack. "I'd have him in the Koenigsberg—he's bled the country white—how much do you think he made on the last army estimates?"

"Exactly the sum you would like to see in your own strong box, I suppose, sir."

Neitschütz raged into bitter laughter.

"You're a cunning young rogue. Perhaps you'll get on, after all, but Madelon is not for you—that girl has cost me two estates already. And worth it. A beauty—a wit—a mind—she'll govern Saxony."

Haverbeck rose.

"My suit is refused?"

"Definitely. She'll marry Johann Georg."

"No—but, even if she might—maybe I, some day, could do as, much for her as any Elector of Saxony."

Haverbeck now spoke with some emotion; he sighed and looked with a distant pity, odd in one so young, at the heavy man who viewed him with such contemptuous hostility.

"Sir, you will never strike down this game, it flies too high. Stürm is clever—if you were to promise her to me—"

Neitschütz got clumsily to his feet.

"You fly too high. I warn you to be more moderate—Madelon! There'll be no one like her in the Empire."

"That is why I want her. But I see where your wish is set." Haverbeck suddenly spoke in hard tones. "And I warn you, Major-General von Neitschütz, your play is full of peril—this marriage will never be—take care, then, take care, I say."

"Of what, Baron de Haverbeck?"

"You know what I mean. Your lure is delicate and easily blown upon—"

Neitschütz fumbled in the skirts of his coat.

"Take your hand from your sword," smiled Haverbeck. "If your daughter's name is so dear to you send away Madame de Rosny."

"What do you know of Madame de Rosny?"

"Enough. She taints this house. I would not have her breathe on Madelon."

There was a passion in these last words, a pain and a sincerity that held Neitschütz silent in a second's flash of shame; Haverbeck passed him and was gone.

It was dark; small, carefully-placed lights disturbed the shadows in the hall and stairs; the door yet stood open on the empty courtyard; above the low walls of the stables showed the faint pure stars.

"Farewell to Arnsdorf," thought Haverbeck, sighing. "If ever I cross this groundsill again we shall all of us be changed indeed."

He was going in search of his body-servant when he observed an elegant carriage drive into the courtyard; as it drew up at the entrance the lantern showed the arms on the harness-cloth—those of Ferdinand, Count Stürm. Haverbeck paused in the door; as a lackey pealed the bell the occupant of the coach alighted—Count Stürm himself. Haverbeck knew him at once, but he did not recognize in the handsome young man who saluted him the beautiful boy he used to admire.

"I am Delphicus de Haverbeck, sir, immediately returned from Paris."

The minister was delighted.

"Baron de Haverbeck! Let me observe you! My friends have written about you from Versailles—in the Life Guards, eh?"

He studied the young man with approval. He was always keenly alert for talent and grace to attach to his party; quick and experienced as he was he saw success in Haverbeck as clearly as if it had been written on his brow—an uncommonly attractive presence, well-bred assurance, a steady glance, resolute lips—an asset to any party; with the women, invaluable.

"You are leaving for Dresden?" asked Count Stürm. "Immediately."

"Arnsdorf impossible, eh?" The Minister lowered an already soft voice. "Between you and me, my dear Haverbeck, I think Neitschütz is not quite steady in his intellects—so morose, such a hatred for his fellows! Come back to Dresden with me—I shall be a few moments only...Ah, my dear General, I throw myself on your mercy for this late visit!"

Disturbed by the bell, Neitschütz had come from his cabinet; he was dishevelled, his eyes flushed; he had difficulty in controlling his harsh voice; his repeated bows were ironic.

Count Stürm smiled; he seemed to be really amused; he was; for he thought of twenty years ago, when he had snatched from this man's cold wooing the sickly heiress who had left him half a million in rix-dollars, while Neitschütz had furiously stumbled into a marriage with a poor beauty who had left nothing (when his moods and his violences had chilled and withered her to death) but three expensive children. Count Stürm brought a small case from his pocket.

"My poor gift—and my desolation that I missed your Madelon's festival."

His compliments poured out smoothly; he could afford to be amiable, for, during all this long hatred, he had always been successful; he was also, naturally, an agreeable man—accomplished, vivacious and subtle; it cost him no effort to second the mood of another, even with Neitschütz, his enemy, whom he really detested, his manner was smooth and soothing.

Stürm had a delicate appearance; he suffered, secretly, from ill health; his face was pale and sharp; he wore a fair frizzled peruke; he was fifty and below the middle height, bent slightly, too, above his cane.

He was to the last degree daring, resolute, hard and unscrupulous; for twenty years he had been absolute master in Saxony; bribes from all Europe had helped to swell his fortune; now he had been definitely bought by a yearly pension from France. Tormented, Neitschütz lowered before him, stammered over compliments, opened the case—a bracelet of black tourmalines, the most valuable present Magdalena Sibylla had received...Neitschütz tried to smile, grinned, "A sombre gift for so young a girl!"

"The stones are rare, well-matched," Stürm civilly excused himself. "They show up the whiteness of the skin; perhaps in a few years, when your daughter comes to Dresden—"

"When my daughter comes to Dresden, she'll wear diamonds," he closed his lips on, "in a coronet." He was not master of himself; the vexation of the long homage to the Elector, the unexpected exasperation of the interview with Haverbeck, had shaken him; he would like to have thrown both his guests out of the door. Haverbeck saw his mood and did not wish to exacerbate it; he went to find his servant, to order his departure.

The enemies remained in the hall; Neitschütz made muttering offer of a rummer of Rhenish, the Minister refused all refreshment; he was pressed, he was invaded with work, only with difficulty had he been able to snatch a moment for this visit...if Arnsdorf had not been in the suburbs of Dresden...

Neitschütz received in gloomy torment this onslaught of insolent civilities; he was thinking of the poverty of his house, the desperate state of his fortunes, the crudeness of his design to marry his daughter to the Electoral Prince—and how obvious all these were to the keen ironic mind of Ferdinand Stürm.

When Haverbeck returned to the hall the Minister offered him a seat in his coach; when the youth accepted it seemed to Neitschütz that another had been added to his enemies; he made no comment on the sudden departure of Haverbeck.

Count Stürm sighed as he settled comfortably into the cushions of the berline. "A visit here is always disagreeable," and he warned Haverbeck of an invalid dog that occupied a warm place in the coach and whose smooth, fat whiteness could scarcely be perceived in the dusk.

But the young man had entered carefully, all his actions were marked by delicacy and precision; as the carriage swung to the Dresden road he asked:

"Will Neitschütz marry his daughter to the Electoral Prince?"

"Not while I live."

"Is it true that the boy is fascinated by her?"

"Yes—a wilful, unstable, untrained child. He will outgrow many such passions. They are children—wait five—eight years."

"What will Madelon be like in five, eight years?" questioned Haverbeck; he looked out of the coach window and the twilight landscape, vague beneath the sparkle of the stars, gave him an extraordinary pleasure; he felt a mounting ecstasy of happiness due to his own youth, the beauty of the world, and the movement of the coach taking him swiftly on the road towards his own fortune...

Neitschütz remained in his ill-lit hall; he saw Haverbeck's servant and baggage depart; when the clatter of that had died away the house was very quiet; the first dry dead leaves blew in across the stone floor with a rustling whisper; the pellucid azure above the stables faded into darkness.

Neitschütz morosely fumbled with his thoughts of hate and tried to reduce them to some coherent design; his one hope, his one expectation, lay in that child upstairs, asleep now, with Madame de Rosny moving in her chamber, putting away the birthday gifts, the birthday crown, the birthday dress...Never before had Neitschütz felt queasy on the subject of the governess; a swelling rancour rose in him against Haverbeck whose looks and words, bitterly recalled, made him feel queasy now.

When his daughter was married to Johann Georg, that perked up, trim young coxcomb Haverbeck should feel the punishment of his effrontery.

A valet came to close the door; Neitschütz liked neither the fellow's faded livery nor the reminder in his unshaven, sullen face that his wages were overdue; as the bolts shot into place the Master of the House of Neitschütz retired to his gloomy, disordered cabinet, replenished the coarse candles, replenished the rum arrack in the thick glass, found his pipe, drank and smoked, sunken in his massive chair.

By a convenient door near the bureau Madame de Rosny entered; the formality of her russet gown had been discarded for a robe of pink sarcenet, the bosom open on abundant if mended laces; she was perfumed with orris root, the rouge under her eyes gave her face, in the candle-light, some lustre.

"Madelon behaved herself very well. I hope, Rudolph, you are pleased?"

Neitschütz pulled at his pipe without answering; piqued by his sullenness, the governess, who had lately had much to complain of, added:

"You will admit I have taught her something?"

Neitschütz replied rudely:

"Take care you don't teach her too much."

Françoise de Rosny thought at once, "That boy, he's brought tales, he disapproved!" She shrugged and pounced.

"Too late, Rudolph. Madelon is, and always will be, exactly what you and I have made her."

The heavy man, huddled in the heavy chair, the sombre shadow, felt the wound and grinned, a flicker of his flushed eyes returned the weary detestation in her tired gaze.

Madelon's festival was over.

Count Ferdinand Stürm sipped the medicine which his doctor measured out for him and when he had drunk it, gave a lollipop to a pampered monkey, which, belted and chained in carved silver, sat beside him on the table covered with a silk Persian carpet.

"Eh, Pug!" he smiled. "Good Pug, pleasant Pug!" for he liked to see the little animal indulge in the gross delights which did not interest him personally; although a sick man and nearly sixty years of age, Count Stürm had managed by incessant and watchful care to preserve all his mental and many of his physical activities.

Stürm knew exactly what he had to face; while the late Elector, his nominal master, had lived, it had not been too difficult for him to thwart all the frantic (and crude, Stürm thought) endeavours of General von Neitschütz to marry his daughter to the Electoral Prince. Easy, lazy, and relying entirely on his minister, who saved him all trouble and all disagreeableness, Johann Georg III, although he had promised his son's hand to Magdalena Sibylla von Neitschütz, yet had contrived to evade the fulfilment of the contract...His sudden death from an unexpected apoplexy had altered the position. Count Stürm had to deal directly with the wayward lover, who had already petulantly announced his intention of an immediate marriage with the lady of his desire.

The Minister realized, not without humour, exactly what such a marriage would mean to him; he knew to the last degree the amount of hatred he had raised in the breast of General von Neitschütz; he knew that the girl who might be in the position of the arbiter of his destiny had inherited all this hatred; he knew that she was aware of his long, steady efforts—both sly and open—to prevent her marriage with the Electoral Prince.

Sir William Colt, the English envoy (who had come with the excuse of the Garter for the new Elector, but really to win him for the Allies), Count von Spanheim, the Imperial resident, and Mynheer Heemskerke, the Dutch Republic's man, had already shown signs of paying some hesitant and dubious court to the House of Neitschütz in the hope that this marriage, so much discussed and disputed, might become one day an astonishing reality...The Prince was very young, impetuous, desperately lost in love...

Count Ferdinand Stürm therefore faced a life and death contest with the puissant powers of love and ambition; not only his own reputation and fortune and, possibly, his own liberty were in question, but the policy to which he had devoted all his entire life, all his labour and all his intelligence; he was not only influenced by the high pension which he received from King Louis, he sincerely believed in the cause of France. The best fortune that could happen to him, if he made peace with his triumphant enemies, would be to retire to a small estate and watch melons and peaches ripen, and argue with his gardener over the construction of glasshouses. This prospect did not appear seductive to him; a man of affairs, of action, he had enjoyed power for nearly thirty years, and he did not intend to relinquish it without the sharpest of struggles.

As he thoughtfully fed the glutted monkey with the brightly-coloured sweetmeats he considered his plans. He must move swiftly. The young man, who had been despatched on a hunting expedition at Moritzburg, was already restive and suspicious, he could not long by all the attractions of venery be kept from the bewitching girl; he had announced his intention of a visit to Château Arnsdorf. And, once the sly, unscrupulous tribe of them got him at Arnsdorf, Count Stürm was well aware of the danger of a sudden secret marriage; he was too wise a politician to undervalue his opponents; he knew the force and power of General von Neitschütz; he knew, more important, the beauty and wit and intelligence of Magdalena Sibylla, and the hold she had upon the romantic, ignorant youth, the dominion over his senses and his intellects. Stürm knew the pride of the male members of that House of Neitschütz, their ancient birth which could compare not unfavourably with that of the Elector himself; knew their pretensions, their desperation, their boldness and greed; he would have to exert himself to defeat them. "Strike at your enemy's weakest point" had always been his maxim. Rudolph von Neitschütz's weakest point was his poverty; this kept him in a continual exasperated embarrassment; he had had the strength to affront this perpetual torment, but his sons had gone down easily into misfortune. Well, then, strike at him through the sons...worthless, reckless young rakehells; Casimir, at least, worthless, reckless, a scoundrel, without common prudence, knowing no restraint...

Count Stürm drew out of his pocket the draft of a letter and the protocol of an agreement which had just been brought to him by his secretary. This demanded the hand of Eleanora Erdmuth Louise of Saxe-Eisenach, widow of Johann Frederic, Margrave of Anspach, for Johann Georg IV, Elector of Saxony—Arch Marshal of the Empire—a score of other honours! Count Stürm was scanning and approving these documents, fine finger tapping the arm of his chair, when the elegant door opened, and an elegant valet announced:

"Major-General Lüneburg de Haverbeck."

The minister greeted the soldier with tactful and gracious warmth; he entreated him to a seat, made humble excuses for breaking in upon his brief leisure...He always maintained amiable, if not cordial, relations with the officer who, engaged in the war with the Porte on the confines of the Empire, had not seen very much of the minister; for even when the armies went into winter quarters Haverbeck had not spent all his leisure in Dresden. Count Stürm had neither impeded nor aided the soldier's career, which had been, owing to his own brilliant yet solid parts, his splendid gifts of character and intellect, singularly successful.

Major-General Delphicus Lüneburg de Haverbeck, of the Life Guards of the Elector of Saxony, commanding that Prince's troops in Hungary, affable, generous, handsome, was one of the most popular leaders in that large army of mixed nationalities, volunteers, mercenary and Imperial, who held back the Turk on the confines of Europe; easy and smiling, he waited for the old man to speak. Haverbeck was curious to know what business Count Stürm had with him in requesting this interview, yet watched with his usual patience while the minister smilingly played with the monkey who gambolled up and down the table and pulled at the Persian drapery. While still thus idly engaged Stürm asked the soldier if he was soon due to return to Vienna, or to the quarters of the Duke of Lorraine, or that of the Margrave of Baden-Baden...

"I await the commands of the Elector," smiled Haverbeck. "I hear that his new policies are uncertain, and that he is not yet sure of sending his auxiliaries again to His Imperial Majesty."

"Like a child with a new toy," replied the minister, placidly, "His Electoral Highness is engaged in playing with several novel schemes."

"Politics," admitted the soldier, candidly, "do not interest me. I should be sorry, however, to grow rusty in barracks, and I hope, Count Stürm, you will be able to find some use for my sword, either in Hungary or Flanders."

"You must be well aware, my dear General, that it is impossible for me to send Saxony into the field, either against France or for France; I am entirely in the interest of His Most Christian Majesty, but I cannot openly assist him. As for you, your career is best pursued in the East."

"I should not care to fight against France," said Haverbeck, indifferently, "but I do not relish this delay in sending the Saxon contingent to Hungary."

"It will go, it will go," nodded the minister, soothingly, "but you must admit yourself, my dear General, that the roads are deucedly impassable, and that our new master is deucedly impossible—a wayward, petulant youth...I have despatched him to Moritzburg to cool his blood, hunting. I shall have my way with him, no doubt, but it will take time. He has been pampered, he is ill-trained, glutted with indolence and pleasure; yet I think there are in him some sparks of pride and enterprise. The campaign in Hungary under your tuition, my dear General, could be of considerable benefit to His Electoral Highness, could I but induce him to exert himself to that extent."

"It was not this matter," smiled Haverbeck, "that you wished to see me about?"

"No," replied the minister, "I wished to see you about the affair of the House of Neitschütz."

He paused on this name, but Haverbeck did not speak; leaning back in his chair, he played with the ends of his lace cravat and ribbons, and Count Stürm knew that it was useless to waste time on involved compliments or apologies; the soldier was, in his way, as shrewd, as alert, as he was himself.

"Forgive me, if I ask you, my dear Haverbeck, if you have any prospect or expectation of marrying the daughter of General von Neitschütz?"

"None," replied Haverbeck, drily. "As I daresay you are aware I have offered for the lady twice, and twice been definitely refused."

"I am glad for your sake," smiled Count Stürm, carefully putting his delicate finger-tips together. "She is to sight and ear delectable, and I would not decry one who has been your choice; but, believe me, she brings discomfiture for her admirers, there is bad blood in that House—I believe the lady to be like her father, hard, ambitious, and unscrupulous."

"They are my relations," commented Haverbeck, shortly.

"Eh, yes, but the connection is distant. I speak to you as one man of the world to another; it is useless, surely you will not affect to be unaware of what I daresay is the property of every street boy...videlicet, my position with regard to the House of Neitschütz in general and this lady in particular."

Haverbeck smiled, looked steadily at the speaker, and raised his dark, slanting brows.

"The young Elector is lost in love with Fräulein von Neitschütz, you mean, and will marry her, in spite of all your efforts, Count Stürm?"

"We shall see." The minister was smiling also. "They will make, of course, the most valiant and determined attempt; he is already pestered to go to Arnsdorf, and if they once get him there in his present mood, after three months apart from her, there will be a secret marriage, no doubt...the design is palpable enough."

"Can you prevent him going?" asked Haverbeck.

"No, I do not think I can, but perhaps I can put him into such a mood that his going there will not mean a marriage."

"I," said the young soldier, slightly troubled, "can have no part in this. The House of Neitschütz has declined my alliance and even my friendship. I have not been to Arnsdorf for eight years."

"I recall," nodded Stürm, "the day you and I left together, eh? Well, my dear General, I have never been able to do anything for you, you have never asked any favours, and maybe, never will; but I come to you now and ask a favour. Do you know anything of the affairs of your cousins—Captain Casimir and Captain Clement von Neitschütz?"

As Count Stürm made this request he carefully studied the agreeable, handsome face of the soldier, and he saw it harden; he therefore added immediately:

"I do not ask you—it goes without saying—to betray either a confidence or a relation."

"As I supposed," replied Haverbeck, drily. "I know nothing of these two young men, they have avoided me; I have been, as you know, so much abroad and am in another regiment and of another rank. You must be aware that they have little capacity and great extravagance."

"They are involved, I think," suggested Count Stürm, thoughtfully caressing the monkey, "with Fani von Ilten, eh?"

"It would be extraordinary if they were not," replied Haverbeck; "she has most of the idle young officers of the garrison in her vile net. I sometimes wonder, my dear Count, that you do not lessen that harridan's activities."

"The good Baroness is extraordinarily useful to me," admitted the minister. "I obtain through her means information that it would be hopeless to endeavour to get hold of in any other way, and it is not in her power to ruin anybody but fools—and fools are of no use to themselves or to anyone else."

"I believe it probable that my cousins go to her infamous house, and gamble, and that they have borrowed money from her, but I know nothing."

"I can find that out for myself," said Count Stürm, patiently. "You have answered me, my dear General. I take it that you know nothing more and would not tell me, if you did."

"I should not feel obliged to do so," smiled Haverbeck. "I do not know your motives in these questions—which ring unpleasantly enough."

"I did not so intend them," the minister assured him gently. "I trust you will do me the honour to believe that I have been perfectly frank, and that I desire to be of some benefit to you. Cannot you see what I would propose?"

"No," declared Haverbeck, roundly.

"This, then: you tell me that you have offered twice—a fact that I already knew—for Magdalena Sibylla von Neitschütz. I may believe, therefore, that the lady has some value in your eyes?"

"You may," admitted Haverbeck, "believe as much."

"If she does not marry the Elector," added Count Stürm, quickly, "it would be likely, would it not, my dear General, that she might marry you, especially if I were to give another flourish to your career by securing you promotion—at twenty-eight, eh? You are worthy of it. Briefly, in every possible way help me to break off the affair with the Elector, and I will help you in every possible way to secure Fräulein von Neitschütz for yourself."

"How could I help you?" asked Haverbeck, sternly, leaning forward in his chair.

The answer came swiftly, as if it had been long prepared:

"Through those two flaunting young rakehells your cousins...Find out from them what will disgust the Elector. No doubt they are in their sister's confidence, and she must have written to them...Get hold of Fani von Ilten and discover from her the extent of their entanglement. Find me some evidence I can put before the Elector."

"Evidence as to what?" demanded Haverbeck, rising.

"Evidence as to the gross trap being laid for him. Perhaps," added Stürm, softly, "you have had some favour—some trifling letter or note, that might show where the lady's fancy lies...you take me?"

General de Haverbeck shook his handsome head slowly, smiling down at the shrunken figure of the minister beside the long table with the Persian cloth and the quick little monkey, and the sardian onyx bowl of sweetmeats.

"Nothing," he said, "nothing whatever. The lady has never marked me out for the least consideration...I know nothing, nothing whatever of the House of Neitschütz."

"You will not help me, then?"

"No, I am not a man of intrigue."

Count Stürm at this attitude showed discreet surprise.

"Not even to gain the lady to whom you have been so faithful? everyone comments, my dear General, that it is strange that you are not yet married."

"There are some things that no woman is worth," replied Haverbeck, indifferently; "I never had a fancy for that for which I had to stoop to pick up."

"You are not, then," smiled Count Stürm, "lost in love, as you termed the Elector?"

"By no means," agreed Haverbeck, affably.

The two men looked at each other with a certain curiosity that for a second overbore their common interest in what they spoke of; they were so different; the little statesman, shrivelled, bent, dainty and precise, with his nice airs and heartless smile, his sharp, unwholesome coloured face, tinged with the acids of ill health, his immense, pale, frizzled peruke, and his handsome, formal clothes hanging limply on his wasted frame, was an odd, a pitiable, object in the eyes of the soldier; Delphicus de Haverbeck, who had eight years before attracted the jaded glance of Madame de Rosny as an extremely handsome youth, was now an extremely handsome man, set off by the parade of a fine uniform, and a generous, noble air, at once amiable and resolute; he gave the impression of one who had his own fortunes admirably in hand and would never ask license or favour from any. Stürm who had kept an easy but continuous watch on him, knew that he stood very well with the Emperor and his Generals, Lorraine, and Baden-Baden, and that he had acquitted himself with brilliant credit against the veteran troops of the Porte in that tedious, anxious, internecine warfare that tore and harried at the frontiers of the Empire.

"I suppose," remarked Stürm, seeming to huddle closer into his handsome clothes, "that you mean to do the best you possibly can for yourself?"

"I know of no one who would admit to less."

Stürm stroked his flaccid visage.

"You sent a Memorial to the Elector on the state of the Army."

"Uselessly. As I imagine."

"It has inflamed the young man to no purpose. Why excite him about what he knows nothing of? His father kept him silly—away from affairs—his idea of fighting is fisticuffs; indeed," added Stürm with an odd smile, "he is very innocent and simple for twenty-one."

"The late Prince was a good soldier," replied Haverbeck, with bold candour, "but lately suffered, under your influence and through a long peace, the Army to be decayed."

"Blame me. Yes, you are right. I do not intend war—why spend money on the Army?"

"The troops I have in Hungary," said Haverbeck, "were far from an honour to Saxony. Lorraine remarked it. To my confusion."

"But you have amended that, eh? I hear you have some admirable soldiers now."

"They have improved. But I cannot prevail against the corruption here. Marshal von Pollnitz is senile, and ruled by a rapacious woman."

"He has, however, one merit," put in Stürm, gently, "he is obedient to all I say."

"I know. Your man. So all is blocked. I have set out the abuses to the Elector, yet with slender expectation of reform. The Council of State is in your hands, too. And the fame of Saxony is cheapened, Count."

"Ah," smiled Stürm, not in the least nettled, "you listen to the chit-cats...the Army is adequate for a peace standing. The Elector won't heed your Memorial."

"It was a matter of conscience to send it."

"You were not thinking of your career as well as the fame of Saxony?" suggested Stürm, slyly.

"Certainly I was thinking of that. I do not care to be set back by the knavery of others, nor thwarted by the dishonest mischief of weaklings and imbecile traffickers in honours and profits."

Haverbeck spoke sternly with a rise of passion in his voice.

"Your tone is not ceremonious," protested Stürm, yet mildly and with insinuation in his voice, "but I have not invited ceremony. I know you are a man of inviolable honour and distinguished energy—vigilant and cautious—a little out of place in these times, but no doubt, General de Haverbeck, you will make your mark. The quickness of your perception will have enabled you to realize that this will scarcely be through me."

"Precisely," replied Haverbeck. "And you, sir, will be aware that I can be involved in no deception or stratagem that is intended on the House of Neitschütz."

The soldier took up his large gauntlets, his cane, and his braided cockaded hat; his pleasant manner verged on contempt. He departed with the least possible ceremony.

"Unshakable, useless," smiled Count Stürm, giving the monkey his finger to bite. "He'll climb on his own path, unaided, eh, Pug?—and probably fall before he reaches the summit." The old man then struck a bell that brought his sombre, quiet secretary; Stürm handed him the letter with the marriage contract of the young Elector.

"Have those articles engrossed and sent off immediately. Have you the report from Strattmann about the brothers Neitschütz?"

"Yes, sir, it is ready for your perusal."

"He has watched them?"

"Yes, sir, and prepared a dossier."

"Very well, I will see Strattmann myself, and intimate to the Baroness von Ilten that I would like a personal interview—not here, I think, but at her own house. And now, hand me the green ledger."

The secretary unlocked a handsome cabinet in cinnabar lacquer, and brought out a thick book bound in green morocco which he put before his master. This contained a list, continually altered and brought up to date, of all the principal men in the Empire, of all the nobility who composed the court at Dresden, and of many of the considerable citizens of that city, together with the names of their wives or mistresses, and notes of the amount of influence these ladies were supposed to enjoy with their husbands or lovers. Count Stürm turned swiftly to the entry—"Major-General Delphicus Secundus Hyacinthus Lüneburg de Haverbeck of the Life Guards—Commanding for the Elector in Hungary." Against this was the note—"Angelica, or Angelique, an actress of the Italian Comedy (Carlotta Drexel, formerly a lace maker at Cassel). He has withdrawn her completely from the stage and keeps her in a small country-house outside Dresden on the Bachnitz Road. Though she appears faithful she has no influence with him whatever; she is very ignorant; she does not accompany him on his campaigns. There is one child aged about four years."

Count Stürm closed the green book and returned it to his secretary. He had learnt nothing that helped him; not because of any passion for another woman had Haverbeck declined to use the means suggested to obtain Magdalena Sibylla von Neitschütz, to whom however the minister continued to believe he was faithfully and deeply attached.

"Eh, well, Pug, we've done our best."

Convinced now that Haverbeck was of no use to him, Count Stürm put him out of his mind; he bore the handsome soldier no malice; he would prefer to have him for a friend rather than an enemy, for he believed that he would be very successful—possibly a great man.

"No doubt Saxony will be too small for his ambitions! but, eh, well, I'm ageing, by the time he is at his zenith my sun will have set, eh, Pug?"

The lean little man grinned, unfolded and read the report of Strattmann, one of his secret service agents, on the two young scions of the House of Neitschütz, the brothers of the dangerous Magdalena Sibylla. He found this very satisfactory. It should be easy to skilfully deal some fatal stroke at this most vulnerable spot; he reflected deliberately yet swiftly on time and circumstance, considered how long he could keep Johann Georg fretting at Moritzburg, how long Neitschütz would be likely to wait for him at Arnsdorf, the possibility of the girl being brought to Dresden, whether it would be wise to detain Haverbeck in Dresden, on the chance that he might again be brought face to face with Magdalena Sibylla von Neitschütz, or whether it would be the greater prudence to arrange for his return to Hungary...Fani von Ilten, who was likely to supply the key to the whole scheme, must be seen at once.

Count Stürm had recently noted that this lady had lately taken into her establishment—the pleasanter name for which was a gambling hell—a woman by the name of Françoise de Rosny—a discredited French noblewoman, who had been for a number of years at Arnsdorf in the capacity of governess to Magdalena Sibylla. It was not to be supposed that she would feel much loyalty to her late employer; Stürm was certain she could be bought, and almost certain that she would have matter worth the buying...this part of the game was apt to soil the fingers, he would move through it swiftly, fastidiously; it was not the first time that he had had to close his nostrils to the odour of the materials that he handled; he did not swerve from his purpose for any ugly details in the way.

Major-General de Haverbeck had left the Residenzschloss with some disturbance of his spirits. He had been aware of the methods of Count Stürm from the first time that he had been brought actually in touch with them. His life of the camp, though outwardly free and frank, had its undercurrent of intrigue, and intrigue not too delicate or savoury; but Haverbeck had never mingled in underhand policies—what he could not take easily and boldly he had forgone. He was convinced in his own mind that Count Stürm was over-anxious, and that the Elector—infatuated as he might be—would never marry the penniless daughter of a ruined subject. He judged that young man to be too vain, too sensitive to ridicule, too mean to venture so great a throw. In brief, Haverbeck did not think well enough of Johann Georg to believe he would put through so princely an action as to marry the woman he loved in the face of the opposition of his ministers and the scorn of his fellow-princes; he thought therefore that the House of Neitschütz would be most hideously baulked of their long-anticipated fortune.

Returned to his own lodging, Haverbeck composed a letter in duplicate, not without some disgust at those to whom he wrote and an uncommon lack of harmony in his own spirits.

My Cousin,

I believe it is necessary to inform you that you would do well to be cautious

in your dealings with the woman, Fani von Ilten, and in every way to beware

of creating any scandal. I have no knowledge of your circumstance or fancies,

but whatever they be I beg you to take this to heart, for your own as well as

your father and sister's sake. Believe me to be, my dear Cousin, your

devoted, affectionate friend and cousin, Delphicus Lieneburg de

Haverbeck.

He addressed these two epistles to Casimir and Clement, and sent them by his sergeant to the depot of the Cuirassiers, to which regiment the two brothers belonged. He was so ignorant of the affairs of the House of Neitschütz as not to guess that his warning came altogether too late, that it would prove of not the slightest significance, and be screwed up and tossed away as an impertinence by the young men he wished to save from a degradation to which they were already too deeply committed.

The spring day hung slackly on the spirits of Haverbeck when he had dispatched his epistles; the blue air about the city was for him empty of delight; he had been arrogantly menaced by Providence; his dearest desire seemed lost, she was withheld from him by all the force of vile, alarmed and powerful passions; and Stürm had allowed him to see that his career in Saxony was destitute of glorious opportunity; Pollnitz, the sick, corrupt ancient Chief of the Army, would retain his post, and he, Haverbeck, might waste in the Hungarian marshes, a General of Cavalry, and no more, indefinitely. Haverbeck did not abate his intentions of a better fortune than this, but he had the fortitude to do a hard thing for one of his temperament—wait, in idleness, on events.

"Oblige me," said Count Stürm, "as far as your convenience permits, and I shall not be troublesome either to you or your friends."