1. This ebook was made from the "Fifth and Cheaper Edition" (1928), published by Methuen and Co. Ltd., London. The publisher states that "the book has been abridged to bring it within the length of this series."

2. In the Preface to this edition (see below) the author places the novel within the context of the series of five novels which she composed from the history of The Netherlands. All five novels are available from Project Gutenberg Australia and from Roy Glashan's Library.

William, by the Grace of God, 1928 edition

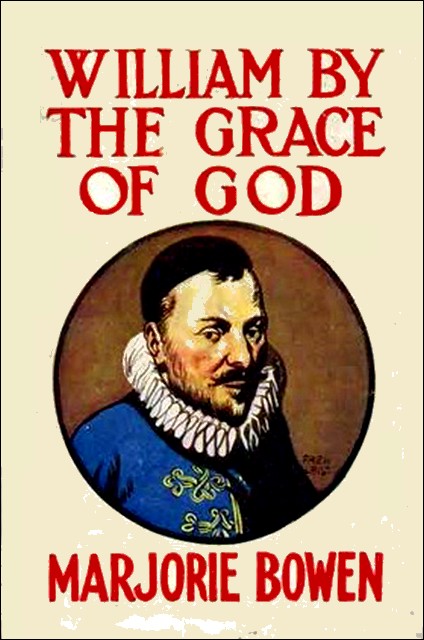

This historical novel is the second in a series of five which the writer has composed from the history of The Netherlands, a subject hitherto untouched by English romancers. Prince and Heretic dealt with William I of Orange (called in English "William the Silent"), in the early days of his career, and with his first marriage, and the beginning of the revolt in The Netherlands, those northern provinces of Philip II's Dutch dominions which finally wrested themselves free from his power, and constituted the Dutch Republic, the first free country in Europe.

The present story, which is a sequel to the first, brings us into the heart of the struggle, and commences when the prospects of the Dutch looked dark and even disastrous. The tale introduces William as a fugitive, but in no way dispirited or disheartened, and still animated by that intense ardour and enthusiasm for the work to which he had set his hand and which was, in the end, to prove eminently successful.

The effect of the Massacre of St. Bartholomew on the cause and on the Prince next follows. The book covers the battle of Mookerheide, with the tragic death of the two young Nassau princes, the brothers of William, the siege of Leiden, and finally the assassination of William at Delft by Gèrard, the fanatic Burgundian.

The story, however, does not end on a note of despair, for, if William of Nassau was killed, his son Maurice of Nassau lived; and that son was to prove a more than worthy successor to his great father, and regain for The Netherlands many towns and villages, and to set on a firm basis the Dutch Republic that his brother, Frederic Henry, was to raise to a bright pinnacle of glory.

Women do not play a great part in this story, which is essentially of men and men's affairs, and deals with the building up of a nation; but there are portraits of Charlotte of Bourbon, the one-time nun, and Louise, the last wives of William of Orange, and the devotion of an obscure lady-in-waiting runs like a quiet obbligato through all the affairs of state and all the pomp of war.

Nearly a hundred years later, the Dutch Republic, built up by William of Orange and his friends and sup porters into one of the great powers of Europe, was again in grave danger—this time in peril of utter extinction by a foreign foe, as it had been through the efforts of the King of Spain in peril of utter extinction almost before it was created.

This time it was France that swept The Netherlands, and again it was a Prince of the House of Orange who rescued them. This story, one of the most splendid in modern history, is told in the three books, I Will Maintain, Defender of the Faith, God and The King, which carries the story of Holland down to the opening years of the eighteenth century.

The last of this series covers the history of England at that period as well, the fortunes of the two nations being then one; nor is the story of William the Silent without interest for English readers, for it touches our story at many points—Philip II, his grim opponent, was the husband of one of our English queens, Mary Tudor, and her Protestant sister, Queen Elizabeth, did send help to William the Silent, though perhaps in a paltry measure. Sidney and Leicester are still well-known names in The Netherlands, and there are few towns which have not some memory of the help given by England to the Dutch in the sixteenth century. Zutphen is still celebrated as the spot where the famous Sir Philip Sidney met his end, and there can be no doubt that the firm resistance of the Dutch to the aggressions of Spain did keep at bay a most formidable foreign power that was striving, with every effort, to reduce the prestige and even the very existence of England, the England as was then established after the Reformation.

English volunteers in considerable numbers also helped Maurice of Nassau, later Prince of Orange, though he had no official assistance from England, and the names of the Veres and Charles Morgan are still strongly associated with these long wars in the Low Countries, only finally terminated by the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which put an end to these religious conflicts: thus concluding the long struggle for the Dutch Independence and the Thirty Years War in Germany which, for a great part of the time, ran side by side with it, and which produced another great Protestant hero from the north, Gustavus-Adolphus, to assist in holding back the power of Rome and the princes helped and inspired by Rome. How far these wars were really political and how far really religious, it is now impossible to decide, then as now men's motives being so mixed; but, with all the allowances made for the intrigues of politicians and the ambitions of princes, there can be no doubt that these Protestants—from kings to peasants—were fighting, in the main, for the cause of liberty, and struggling to break away from tyrannies Which had become insupportable, and which were represented by Catholic powers—the Pope, the Emperor, the Kings of France and Spain—all, on their several occasions, striving to overwhelm and destroy the countries of the north which had adopted the reformed religion: England, The Netherlands and Scandinavia, and parts of Germany itself, the cradle of the Reformation.

It is this struggle, continuing for so many years, which is the main theme of these five romances of which this is the second; and, though the heroes change, the cause does not, and the theme, though treated with many varieties of scene and character, remains identical from first to last of these five books.

Though written mainly from a Protestant angle, they contain no prejudice whatever against the Roman Catholics, in whose cause many grand figures fought, and for whose politics and outlook there was, of course, a great deal to be said; and who had, in many of their pretensions, considerable justification, at least in the matter of worldly rights. One need cherish no bias for one side or the other to be enabled to appreciate the stories of these Princes of the House of Orange, and their long and persistent struggles against unequal odds.

MARJORIE BOWEN.

GRAY'S INN, LONDON.

February 8, 1928.

A man was travelling through the Palatine towards the Nassau country; he rode a shabby little horse and his plain riding suit was both worn and mended, a cloak of dark blue Tabinet protected him from the March winds and a leaf hat without a buckle was pulled over his face.

He rode steadily until he came to an inn, the only house visible in all the long grey road, and there he dismounted, took his horse himself to the stable, then passed into the parlour and, going straight to the fire, warmed his hands with an air of pleasure and good humour.

Two other men were there, travellers like himself; they looked at him keenly, with suspicion, apprehension ready to change into open enmity.

One of these addressed the new-comer.

"Early in the year and late in the day to be on the road," he remarked.

"I come from France," was the answer, "business that will not wait forces me to overlook time and season."

"My name is Certain," he added, "a poor merchant from the Netherlands."

He smiled at them, advanced to the table and seated himself there, looking at his companions still with that smiling intentness.

He had revealed himself as a man of middle height, hardly yet in his full maturity, his figure and his bearing were both notably graceful, his hands extremely fine, his head was small, his complexion olive, his eyes and cropped hair brown, his beard shaved close; a muslin collar finished his ancient green suit; he wore no jewels nor ornaments; at his waist hung a short sword and a frayed leather wallet.

There was something remarkable in his appearance that caused the other two to gaze at him with undiminished curiosity.

Mynheer Certain, for his part, had soon summed up them and knew them very accurately for what they were, a French pastor of the Calvinist faith and a German clerk or shopkeeper of the poorer sort.

"You appear to doubt me," said the merchant pleasantly; he tapped on the table and when the drawer came ordered wine.

"I doubt the name you gave us," returned the French man; "who in these times travels under his own name?"

"And I," said the other, "was wondering at your nationality—from the Netherlands you say! I did not know that Alva had left any Netherlanders alive."

"A few," Mynheer Certain still smiled.

"So few that we may consider it a country lost from the world, a nation consumed with the fires of its own homesteads," he said, and he looked with a certain commiseration at the Netherlander.

"You think, then, there is no hope for my unhappy land?" asked that person.

"None," said the Calvinist. "The wrath of the Lord has unchained a devil upon them. Evil has strangled there truth and piety—as in France—where indeed can the Reformed Faith claim a foothold save in this realm of the Elector Palatine? You are of the Reformed Faith?"

"Of the Reformed Faith, yes."

The wine had been brought, and the merchant was drinking it slowly, with the relish of a tired man.

"Perhaps," said the German, "you have lost everything under Alva?"

Mynheer Certain gave his ready smile; his face, though lined with fatigue, was charming in contour and expression, and his manner was one of exquisite courtesy.

"Everything," he answered. "My property, my houses,—my son—my dignities, my revenues, my country. For I am an outlaw, an exile. Under the ban of King Philip."

"For your faith, Monsieur?" asked the Calvinsit with sympathy.

"For that, yes."

"You must hate Alva," said the German.

"Hate Alva?" repeated Mynheer Certain. "I do not know if I hate Alva—or King Philip."

"You have, then, no wish for revenge?" asked the pastor. "No wish to assist your wretched brethren, who, like you, have not only lost their all, but are under the hellish dominion of Spain?"

"Every wish," returned the merchant gently, "but no means."

"You are yourself a fugitive?" asked the pastor. "You fly, like all the persecuted, to the Court of the Elector Frederic?"

"No," said the Netherlander. "I am employed by a French house, trading in wool. I make my living."

The Calvinist regarded him with some contempt.

"You are too young to be so idle—there are men fighting for the Reformed Faith—fighting."

"Fighting in a hopeless cause," added the young German.

"So some say," said Mynheer Certain. He finished his wine and pushed back his chair. "Since Condé died at Jarnac—"

Neither of the others answered; the fatal name of Jarnac, where the Protestants had gone down to final defeat before the Catholic legions of France, silenced them.

Only the Netherlander spoke, completing his sentence.

"Who is there to take his place?"

"Coligny," said the pastor with a flash of hope.

"A great man—a helpless one," replied the merchant.

"The Prince of Nassau," said the clerk. He rose, brushing his hat with his coat sleeve.

"They are but as dust before the wind of Philip's wrath," returned the Calvinist. "And the Prince of Orange—he failed—"

"Failed so often," remarked Mynheer Certain, "failed so utterly."

"A great name once," said the German, "a great gentle man, too. I was in Leipsic when he was married to the Elector's niece."

The merchant looked at him sharply.

"You were there?"

"I, yes. I used to work for the Elector's alchemist. What an excitement that marriage was!—the Prince was Catholic then and we all thought that it was a cruelty to the Princess," he laughed. "She has proved to be a mad woman and a wanton too, they say, a disgrace to a proud family."

"Speak of what you know," reproved the merchant sternly, "the name of the Princess of Orange is not for vulgar handling."

"I speak of what all the world knows," returned the young man lightly. "A great wedding," he repeated. "I saw the Prince once, but it seems a thousand years ago—now he is an outlaw like yourself, Mynheer Certain."

"He failed; he failed!" cried the Calvinist impatiently.

"Who was he to withstand Philip?" demanded the German, clapping on his hat. "Though he had titles which would fill a parchment roll and the revenue of an Emperor—yet Philip! 'Tis the greatest king in the world, what subject of his could dream rebellion against him?"

"He of whom you speak," said the merchant quietly, "is no subject of Philip, but a sovereign ruler—Prince of Orange, by the Grace of God."

"By the Grace of God," repeated the Calvinist. "May be yet, God will use him for our deliverance, but humanly speaking I have no hope of him."

"Nor I," added the clerk. "I am due at Heidelberg—so a good evening, sir."

"A good evening," answered the merchant courteously. The Calvinist rose; a life of continual persecution had given him a furtive look; the resignation taught by his stern faith lent some dignity to an appearance of poverty and despair. He was an elderly man and all his life had known nothing but the disappointments of a losing cause, the bitterness of being one of a despised minority.

"How long, O Lord, how long?" he murmured.

He drew his cloak precisely about him and left the room; when the door had closed his heavy tread could be heard mounting to the little room that was his temporary refuge in his wanderings.

The Netherlander stood motionless by the fire; at that moment the sense of the intense unreality of life came oyez him with terrible force.

He thought of the past and time ceased to exist. The days of his prosperity, the days of his exile, moments of anguish, moments of ease mingled together in one intricate pattern, all his life seemed without period or date, a con fusion of events and emotion.

A thousand years ago seemed the marriage of the Prince of Orange, the young man had said—the Netherlander had also been in Leipsic for that ceremony—a thousand years ago—it seemed no less to him...he recalled his own past, pleasant days of gaiety, sport and jest—so utterly lost that no magic could recall them, days when the world had been normal, when all things had moved, pleasantly in their accustomed grooves, days when he had not lacked respect, companions, money, nor leisure—days such as might come into another's life, never again into his...half reluctantly his mind travelled the chaos that had followed the ending of those pleasant times, the exile, poverty, humiliation, failure—the loss of all, the country from which he was banished, the wife who had deserted him, the friends who had died or fallen away from his perilous cause.

No shadow disturbed the composure of his serene face, but the great sadness that was in his eyes deepened, and tears filled them.

With the restless movement of one in pain, he turned from the hearth to the window.

It was raining heavily; the Netherlander looked out steadily at this view of rain, wet trees and loose sky.

A word used by the stranger who had just spoken to him continually recurred to his mind—the Prince of Orange had failed.

In this moment the man looking out at the rain was acknowledging failure, accepting it, failure so complete, until he stood stripped, barren, humiliated before his enemies, a landless exile, banned and proscribed.

Again his mind travelled back to the old days. He contemplated his downfall; he remembered that at one time he had counted on happiness as a right, taken it for granted. Now that seemed to him extraordinary.

He returned to the table and took a little notebook from his pocket, looked through it and laid it down, then he brought out a handful of money, some silver pieces and one piece of gold; this was all he possessed, and taking from his wallet a sheet of paper, he began writing a letter to his brother...

"In the long coffer in my room is a suit of grey and a pair of hosen you may have mended for me—I am in sore need of these and shall thank you for your kind offices could you find a cheap small horse? I need one for a good friend of mine who at present goes a-foot, this is a very necessary thing if the means could be found."

He was penning this letter with a certain haste, as if eager to be rid of a disagreeable task, when the door of the little parlour opened. The traveller at once and swiftly put away his letter.

Voices sounded in the passage and a woman entered the room.

She wore a brown cloth riding suit and carried her wet skirts high, showing her muddied boots; the rain had draggled the long black feather in her buff hat and the locks of reddish hair that had been blown across her wind-flushed face; she was handsome in an imposing, opulent fashion, but her expression was humble and sad.

—Mynheer Certain had risen from his seat at her entry and was turning away, but the instant's glance he had of the woman caused him to pause and glance at her again.

She, entering, came face to face with him and stood arrested in all movement, her face flushing with a look of bewilderment and joy.

The innkeeper behind her began talking of her lame horse and when he might be able to procure her another. She composed herself to answer him.

"If need be I can walk to the Castle," she said, "it is so near—and—I will rest a little while—"

She stopped and began pulling off her gloves.

The landlord left, and the man and woman looked at each other again.

"You remember me?" he said gently

"I was your servant," she answered, "—but you remember me?"

"My lady's waiting-woman, the heretic maid from Dresden—Rénée le Meuny. But perhaps you have changed that name?"

"No," she was looking at him breathlessly. "Why do you speak of me? What of yourself?"

All humility and reverence were in her words; her knees trembled and her lips quivered.

"How I have prayed for your Highness," she murmured. The tears sprang to her eyes. "All these years—" He was moved at that; his sensitive nature was touched by the thought of her remembering and praying when he had forgotten her utterly until he had come face to face with her again.

"—All these years," repeated Rénée le Meuny. "You were ever very loyal," he said kindly.

"Loyal?" she answered strangely.

"Loyal," he repeated. "I remember that I noticed that quality in you—from the first."

He recalled her now very clearly, her impassiveness and reserve, her endless patience before the caprices of an intolerable mistress, the stedfastness with which she had once or twice ventured to speak to him of her persecuted faith.

"I hope all is well with you," he said, and there was a certain tenderness mingled with the usual perfect courtesy of his manner; tenderness for the past and the part Rénée le Meuny had played therein.

She did not appear to hear what he was saying, so utterly absorbed was she by the wonder of meeting him, of seeing actually before her the man who had so long occupied her thoughts.

"We think of you so much at the Castle," she said, "so much."

"You are at the Castle?"

"With the good Electress, yea. She shelters so many—your Highness is coming to the Castle?"

"I had not thought to do so," he answered. "I have no news for the Elector Palatine. I travel as Mynheer Certain—to keep in touch with some agents of mine. My eventual goal is Dillenburg."

"But you will come to Heidelberg," she said, clasping her hands nervously. "You would not pass them by—they—I—we have waited so long for news of you—so patiently."

"I have no news," he said again and turned away his tired eyes.

"Your Highness must come," she pleaded. "Oh, your Highness will come!"

She strangely tempted him—to be among friends, to snatch a few hours of ease, of comfort, why not?

It had not been his intention to ask the sympathy even of those whom he knew would offer it lovingly, but this resolve of his now faltered; something in the personality of the woman swayed him; he had long lacked the devotion of a woman in his life; lately he had met few, refined and comely as Rénée le Meuny; once such women had been as plentiful round him as the flowers in his parterres and as little noticed, now they were a rarity; he even felt grateful to this lady who looked at him in an amaze of pleasure and reverence.

"Why should I not come?" he said with a smile. "It grows dark and you will need an escort to the Castle."

"You would ride with me?" she exclaimed. He was almost startled at her tone.

"Why should I not ride with you?" he asked gently. "I was your servant, one of the least of your servants," she said.

"I am a landless man now," he answered. "I have no servants, and but few friends—make these one more, Mademoiselle."

She moved a little away from him.

"To me," she said simply, "you are always William of Orange."

Slowly they rode together through the pine forest; the rain fell steadily yet gently, there was a faint warmth in the air like the first beginning of the beautiful heat of summer; here and there fresh green tipped the winter darkness of the trees.

They rode with a certain leisure as people who are at no haste to be at their journey's end. To the woman it was an episode of pure happiness in a life that had always been unhappy, to the man it was a pleasant interlude in a life of stress and turmoil unutterable; he rode his shabby hack and she the borrowed horse from the inn; their wet cloaks clung about them and the moisture dripped from their felt hats; the woman's heart glowed with a joy that made the grey afternoon as radiant to her as a midsummer noonday, her mind admitted nothing beyond the fact that they were riding alone together. It seemed incredible after all these years of patience, of abnegations, of dreams.

"You think often of the Netherlands?" asked the Prince.

"Often," she said. "I have wondered if I am ever to return to my unfortunate country—believe me I would go," she added, "if my going was of the least service, but I have always been one of the useless."

"We are all useless compared with our tasks," said the Prince gravely. "I feel myself a handful of dust before the wind, a straw before the tide."

"You are the guiding star of a whole nation," said Rénée le Meuny, "the hope of a Faith—the solace of a Cause." He smiled, turning on her his sad eyes.

"You are good to think that of me—it is their own courage guides and supports the Netherlanders, not II am a man who set himself against great odds and who has failed."

"But who is not defeated, Highness."

"No, not defeated," he assented quietly. "I have yet my brain, my two hands, the name—a name something loved—nothing else."

She looked at him; under the broad brim of his hat his dark face showed pale; the exact fine features had changed since the day she had seen him first; the day when he had mounted the stairs of Leipsic town hall to greet his bride, Anne of Saxony—the smooth olive cheek was hollowed, the brilliant eyes shadowed, in the thick close chestnut locks the white hairs were sprinkled; he looked infinitely tired, and there was great sadness in the resolute lines of his full lips.

Rénée remembered—remembered days of pomp and magnificence and this man moving through them, courted, beloved, and serene, a Prince, a Grandee of Spain, the greatest man in the Netherlands.

And the years between then and now were not so many, and yet she, his wife's waiting-woman, who had courtesied from his path with awe, had met him, a forlorn and penniless exile in a wayside inn, and they were riding together as equals.

Equals—her heart trembled at the word; she knew it was but another dream, that he would always remain a sovereign Prince and she a humble commoner, yet for the moment it was a dream with the semblance of reality; at least all outward sign of difference was done away with, they rode together as fellow exiles, as two of the same country and the same faith—as mere man and woman. And his wife was no longer between them; the worthless, faithless, wanton woman whom Rénée had laboured so long and patiently to save, was repudiated at last, insane in the care of her own kinsfolk.

"If we could ride for ever," thought Rénée, "if the world would stop about us and we could ride on like this through all eternity."

The rain ceased and the light of sunset showed in a faint blur through the straight dark stems of the trees, a pale saffron glow diffused itself through the wood, an indistinct gleam of sunshine quivered along the ground.

"Afterwards," said the Prince, looking at his companion, "when I am again lost in my obscure wanderings, I shall remember this ride very pleasantly."

She turned her glance to her gauntleted hands so slackly holding the reins.

"Count Louis is in health?" she asked. "He is so much spoken of at Heidelberg."

A look of tenderness softened the Prince's face at mention of his younger brother.

"Louis is well and gay," he answered. "His bright spirits help us all to have confidence in our desperate cause."

Rénée recalled her first meeting with Count Louis—the idle young gallant—she remembered too how she had despised him for his air of foppery—how he had shamed her judgment. She had also felt some contempt for the handsome gorgeous Prince of Orange and his political marriage, but that Rénée had now forgotten utterly.

"You remember the days in Brussels?" smiled the Prince, "the feasts, the tourneys—poor wild Brederode—Hoogstraaten—Egmount, Hoorne—my brother Adolphus—Bergen, Floris Montmorency all dead!—dead as the ashes of those festal fires, Mademoiselle."

Rénée shuddered.

"How will Philip answer to God for all these lives, all those other lives, obscure, miserable as these were great?"

He glanced at her still with that wistful smile about his lips.

"Philip? He has pleased his God and knows no other." Rénée was puzzled.

"But there surely is Judgment for such a man?"

"Who knows?" said William calmly. "Judgment is not in our hands, Mademoiselle, we perform our little task while we can and when our day is done—good night! So much to do, so little time to do it in!"

"You do not hate Philip?" she asked as the Calvinist had asked.

"I have hated him. These last years I have got beyond hate—and beyond despair. Mademoiselle, I have been very much in the depths—I have seen grief and sorrow very close. I have been in those places where a man leaves his life or his passions. I lived. I think there was nothing left of what I used to be but a certain faith in human endeavour, a certain hope in the triumph of this world's better things—even against a Philip."

She was silent, overwhelmed that he should thus speak to her.

"So I have hope, even for the Netherlands," continued the Prince. "So I have faith—even in the coming of that time when there shall be no one creed tryannizing over another creed. Even in that I have faith—but one can do so little—only all of us doing something may bring nearer the day of deliverance. So little!" he repeated softly, "to serve the truth as we see it—God as we know Him—justice as it is revealed to us—so little!"

"This from your Highness—who has done everything!"

"Lost everything. The two strangers I parted from just now spoke of my name and failure—coupled the words together!"

But as he spoke he smiled and his eyes were serene.

Rénée thought of all he had endured—defeat, humiliation, contempt, the endless endeavour, the slow patience, the vast energy, the indomitable resource that had again and again been wasted in a fruitless task.

"You will achieve," she said in a low voice, "such as your Highness always achieve."

"If I could do only a little," he answered quietly. "Lately I have been afraid they would kill me before I could do anything at all."

"Kill you?" she stammered.

"Philip thinks me of some importance still," he answered simply, with a little smile. "I am on the list of those he considers dangerous—the list on which he put Hoorne and Egmont."

"They—try to assassinate you?"

"Persistently. Philip has not forgotten that I escaped the net that caught the others."

Rénée's face quivered, she looked away.

"God would not let you be killed," she said. "Too many need your Highness."

He did not answer this; he too had his faith, but it was not so simple as hers; he did not think that Heaven had given him any special mission or would afford him any special protection; to him Eternal Truth and Eternal Justice were throned high above the mud and blood of the present strife, nor did he believe that his endeavours would be even noticed by that Vastness men called God; so far he was a fatalist, and to this point the Calvinist religion, that it had become most expedient for him to embrace, was congenial to him; but had it not been a matter of political wisdom he would not have joined any particular sect; narrowness was hateful to him and the very essence of the cause for which he had given everything was liberty of conscience.

They came out from the pine forest on to the high road; dusk was closing in and before them gleamed the lights in the windows of Heidelberg Castle.

As the Prince saw the Castle before him, his expression subtly changed; the moment of softness passed; like a shadow the reserved look of the man of great affairs, of one engaged in perilous causes and burdened with heavy secrets, came over his face.

"The Elector is at home?" he asked, and Rénée saw that he had already put her from his thoughts and was considering how this chance visit he had been persuaded into might be turned into political account.

"Yes, Monseigneur," she answered, instantly subduing herself to his service, "he will be most honoured at your Highness's coming."

"A pity," observed William, "that he is not so powerful as he is well meaning."

"He is very generous," said Rénée, loyal to the man whose little Court had sheltered her and so many of her co-religionists. "He does not refuse his protection to the most destitute and insignificant. The Electress, too, is wide in charity."

"Mademoiselle de Montpensier is with her?" asked the Prince.

"Yes, Highness. I am her particular attendant. At some peril to themselves their Highnesses shelter this lady, who fled from France to them—Monseigneur knows the story?"

"Of Mademoiselle de Montpensier, the abbess of Jouane?" smiled William, then added with a sudden gravity, "I do not know why I smile, her action showed great courage in the lady."

"Such courage, Monseigneur, for one enclosed in a convent since she was a child of eleven!" said Rénée eagerly, "but she is brave, the Princess, and strong."

"Such women are needed in these times," answered William. "Mademoiselle should marry and comfort some weary man."

Rénée knew that there had been long and persistent talk of a union between William's brother, Louis of Nassau, and Charlotte de Montpensier and she thought that it was to this that he alluded.

"The Electress is eager for such a marriage," she said, "but the Princess is dowerless; her father will give her nothing, and her sister, Madame de Bouillon, cannot."

"Many a man will wed without a dower now as many a woman without an establishment—your little princess will find her mate—she looks a woman for a home."

Rénée was startled.

"Your Highness has seen her?" she exclaimed.

"Once. When I first came to France." He dismissed the subject with a certain abruptness. "We are almost at the Castle, Mademoiselle. I trust your good offices," he added with a very winning courtesy, "to assure my welcome."

"Your Highness humbles me," breathed Rénée. This meeting with the Prince had changed everything for her, so suddenly, so utterly, that she was giddy with it.

In the courtyard he helped her to dismount; and held her gloved hand for a moment after she was standing beside him.

"I thank you for a pleasurable hour, Mademoiselle," he said, and his voice had a quality of gratitude as if he had not been lately used to such sympathy as she had offered him.

She turned towards the Castle entrance, and the Prince, taking off his shabby hat and shaking the water from the brim, followed her.

An officer standing in the hall stared curiously at the slim shabby man behind Rénée.

"The Elector!" she asked.

"His Highness"—he began.

As he spoke Frederic himself came down the wide stairs; beside his stern martial figure was the slender one of the young Count Christopher.

Rénée turned to them.

"Messieurs, I bring you a very notable guest."

"In very notable attire," added William, and he laughed. The Elector came swiftly down the stairs, his face coloured with pleasure. He put his hands on the Prince's shoulders and kissed him on either cheek.

Rénée sped past them, up the stairs and to the apartments of Mademoiselle de Montpensier.

"Mademoiselle," said Rénée breathlessly, "he is here!"

"Who is here, my dear?" asked the Princess. "Your knight at last? I thought that you must have one, Rénée."

Rénée turned away; her lips trembled, her throat was dry and she could not speak.

Charlotte de Bourbon did, not lift her eyes from her work.

This Princess, daughter of the proud Duc de Montpensier, who had been forced by her parents into a cloister at the age of eleven, who had taken her vows under protest, and abandoned her position as abbess in one of the most princely and wealthy establishments in France, to fly into the Palatinate and embrace the Reformed Faith, was a slight fair girl of no great appearance of energy or force of character.

Her features were small, her hair soft and fine, the chin was a little heavy, the eyes dark blue, her manner was one of, above all, serenity. She wore a puce-coloured gown and a falling ruff of delicate muslin covered with needlework.

"Who is he?" she asked again without looking up. "The Prince of Orange, Mademoiselle," answered Rénée quickly.

Now Charlotte dropped her work.

"The Prince of Orange!"

"Yes, Mademoiselle, he is now in the castle."

"Secretly—in disguise?"

"Yes, I left him with the Elector."

Charlotte looked thoughtful; Rénée, who believed the common rumour that the Princess was interested in and would eventually marry Louis of Nassau, remarked, timidly.

"His Highness spoke of his brother—Count Louis, who is safe and well."

Charlotte glanced at her calmly; the serenity that had enabled Mademoiselle de Montpensier to support with dignity so many years of conventual life was always apparent in her demeanour, and Rénée, at least, had never seen any of the spirit that had urged her to break her enforced vows and escape her convent; there still seemed much of the abbess in Charlotte, the dignity of one trained to command, the poise of one who is remote from the world and impervious to worldly troubles.

"Do you think that I am so eager for news of Count Louis?" she asked pleasantly.

"Yes," said Rénée frankly; she was as intimate with the Princess as any woman, but Charlotte had a quality of elusive remoteness difficult to the warm and impulsive nature of the Fleming.

"You listen to gossip," smiled the Princess gently, "but I shall be glad to meet the Prince. He has been wonderful. I believe he will do something yet, even against Alva."

"He has given all he has," answered Rénée. "Everything—you cannot imagine how great and splendid he was, how magnificent—and now—like a beggar—lonely."

"You speak with great enthusiasm," said Charlotte, looking up. "You knew him very well?"

It was in Rénée's heart and almost on her lips to disclose her long-kept secret—"I love him," but something in the utter gentle calm of the Princess checked her; she kept a stern rein over her agitation and answered quietly.

"When I was with his wife I saw much of His Highness."

"Where is his wife?" asked Charlotte; the disastrous ending of the Prince's marriage was a thing hushed and mysterious; these two had never spoken of it before.

"I believe she may be at Dillenburg in the custody of Count John," said Rénée. "Count Louis told me that the Prince had repudiated her and that the Elector of Saxony was to take her back. She is mad."

"Poor wretch!" murmured Charlotte.

Rénée flushed.

"There is no need to pity her, Mademoiselle, she made the Prince's life a humiliation and a misery. I knew her as few others could and there was no good in her. And when the trouble came she deserted him—and—and stooped to another man."

"I know," said the Princess, "therefore I say, 'poor wretch!' Do you not pity such as these, Rénée?

"Nay—at least for her I had no pity."

Charlotte was silent.

"And now the Prince is free," added Rénée. "Free? He considers himself free?"

"He is now a Protestant, and Protestant Divines have freed him from a union the woman trampled on."

Charlotte said no more; she folded away her silks and ribbons into a cedar-wood box.

The rain had begun again, heavy drops splashed down the wide chimney on to the log fire, a high wind shook the window behind the heavy curtain.

The Prince of Orange sat in the Elector's private cabinet and listened to his host speaking on the confusions and disorders that rent the nations. It was second nature in him to listen to all, to defer, to soothe, to conduct intricate intrigue secretly and use people while they thought they used him; he was still the accomplished diplomat he had been in the days of his power when the redoubtable Cardinal Granvelle had described him as "the most dangerous man in the Netherlands," and he still masked his abilities with that show of perfect good humour and tolerance that had always gained him so many adherents.

In his heart he was sick of all men; he himself saw so clearly, so straightly both the great issues that he had at heart and the means to achievement of these same issues, that it was weariness to him to have to wait always on the whims and crooked policies of others.

On every side these others baulked him; the Queen of England was a Protestant, but she would not help him, in despite of her half-promises, because it was not her policy to go to war with Spain, the Protestant Princes of Germany would not risk their all in an encounter with Alva, the French played fast and loose with Protestant and Romanist, Condé's little band with whom William and his brothers had thrown in their fortunes had been scattered like chaff; the Prince had no allies beyond his brothers, John, Louis and Henry, and no resources beyond his own apacity.

The Elector admired him and sympathized with both his cause and his situation, yet William would not even have troubled to visit Heidelberg had he not met Rénée le Meuny, so hopeless did he know it to be to ask Frederic for material.

So he listened to the good Elector's denunciation of Rome and Philip, Alva and the Inquisition, and in his heart was the great sadness and weariness of the man who has undertaken an almost impossible task and knows that he must shoulder it alone.

Frederic sat by the fireplace, his fine, rather heavy face was flushed and animated, his eyes shone under his grey hair and his mouth was firmly set between the grey moustaches and beard.

William, silent, shabby yet elegant, with his air of courteous attention, sat at the round table that occupied the centre of the room; his eyes were fixed intently on the Elector, yet when Frederic, ceasing his powerful yet vague reproaches against the supporters of the Christian faith, asked a sudden question it was with an effort that William recalled himself from his own straying thoughts to answer.

"Why do you rely on the French?" the Elector had demanded.

The Prince utterly unable and unwishful to explain his intricate policies to even such a loyal friend as Frederic, answered smoothly. "I doubt if I could tell why I try for French support," he said, "save that a desperate man clutches at straws. I do not, however, rely on them."

"'Twere wiser not to do so," remarked the Elector shrewdly. "Think you Catherine or her sons could play fair?"

"There is the Guise," replied William. "It is a country split with factions—one of their ambitious young Princes might be tempted."

"By what?"

"The kingdom of the Netherlands," said the Prince calmly.

"Ah, you would offer that?"

"My ideal would be a Republic," answered the Prince, "but I think that unattainable in these times. Therefore I would create a kingdom and offer it to the Prince who would deliver us from Philip and the Inquisition."

"A bold plan," said the Elector with admiration and a little amazement. "Your Highness really thinks it possible to completely deliver the Netherlands?"

"Yes."

"Then it is your Highness should have the throne of this new kingdom."

William appeared neither startled nor flattered; the idea was not new to him.

"A more powerful Protector than myself is needed, Highness. I am a landless man. I can neither command one chest of money nor one regiment of foot. The Netherlands require one who can liberate before he can rule."

"If there is a man in Europe can do that," declared the Elector, "it is yourself."

William slightly flushed.

"I have tried and failed. More than once. I have gathered armies to see them scattered, I have spent all I had with no results. I have lost all I ever had in this cause, all but life," he added, "for what am I now but a derision to Philip and Alva and an object of pity to the world? I undertook what I could not do. I shall try again, but it cannot be alone."

"Better alone than with treacherous help," said the Elector.

William did not answer; the vast schemes that he was meditating required the aid of nations, not only individuals; to attempt alone the task to which he had set his hand was to play a fool's part; he thought the Elector did not understand this but considered him a forlorn adventurer, and therefore he did not answer.

"Whom would you trust?" pursued Frederic. "France, Austria, England?"

"I work," replied the Prince, "with all three, with all—with any. I cannot too carefully choose my means for these ends I have in view—the liberation of the Netherlands and toleration for the Reformed Religion."

The Elector sighed; there was still that look of faint amazement in his face. It seemed quite hopeless to defy Philip, for he was sincere in his profession of the Reformed Faith and ardent in his championship of his co-religionists in the Netherlands.

For an instant the younger man's faith almost convinced him; he looked searchingly at William's steadfast face.

Supposing these golden dreams did come true, supposing the defeated Prince did snatch a nation from Philip's wrath and Alva's sword?

"You have great confidence in success, Highness?" he asked.

"I do not know," replied William slowly. "I cannot tell how long I have."

"You think that Philip pursues you?" asked Frederic gloomily.

"I know it. I was on the same list as Hoorne and Floris, Egmont and Bergen. The King will not rest till I have joined them, Highness."

"Assassination! the Spanish hound!" cried the Elector. "Death some way," said William. "They have tried several times. Once they will try and not fail."

"You think that?"

"Is it likely, Highness, that such a man as Philip would fail in such an aim?"

"This is a horrible thing for you to live with," muttered the Elector.

"I am used to it. I know that some day Philip's steel or bullet or poison will end me as it ended them. Unless the chance of battle saves me. The question is, how much I can accomplish first."

Frederic had no good answer ready; it seemed to him indeed unlikely that Philip who had set William under a ban, and resolved on his death by any means and at any cost, would allow to escape the last and most illustrious of the Netherlanders who had defied his authority.

The Prince's thoughts had travelled far from the subject; there was one question only he wished to put to the Elector. "How many men would you raise for me in the Palatinate?" talk of other matters was but waste of time, and he would consider his evening wasted if he could not obtain some promise of support from Frederic.

He rose and crossed to the hearth with the intention of asking the Elector for a levy of men; though he would very willingly have been silent on this matter to the Elector; but his policy had been too long that of ceaseless endeavour in every direction for him to leave unused this chance that had come his way.

He was about to speak when the door opened and two women entered the apartment.

The foremost was the Electress, she who had been the wife of the wild Beggar leader, Count Brederode, and her companion was Mademoiselle de Montpensier.

"Highness," said the Electress, addressing the Prince of Orange, "since you would not come to wait on us we are here to wait on you," she held out her hand frankly and smiled. "We used to know each other in Brussels, Monseigneur, will you ignore old friends?"

"I was in no trim to speak to ladies," answered William. "I go darkly, shadowed with misfortune, and would not offend gentle eyes nor sadden hearts."

As he spoke he looked at her wistfully, for in truth she reminded him of those old Brussels days—the days of youth and pleasure.

"I knew they would bring you their homage, Prince," smiled the Elector. "Your name is ever on their tongues—this," he drew forward his young guest, "this is Mademoiselle Charlotte de Bourbon, the Duc de Montpensier's daughter, lately of that faith, Highness, for which you fight."

The Prince glanced at her quickly; the Elector had drawn her into the golden circle of the lamplight.

In that moment Charlotte looked beautiful, her face was flushed and soft above the fine gauze ruff, the fair hair loosened about the low placid brow and the eyes shining with an eager light.

"We met before, twice," said William.

"Twice?"

"Once at the Louvre—you were a very little maid, you stood in an alcove and watched the Queen of Scotland dance. It was a little while before King Henry died."

She smiled.

"You saw me? A funny little child! Soon after that they made me a nun."

"And now you have taken your freedom. With great courage."

The Princess impulsively caught the Elector's hand, while her eyes turned affectionately towards his wife.

"These saved me. I am homeless but for them. My father disowns me. I am exile as yourself, Highness; closed to me is France—but I am very happy here," she added instantly; despite her dignity there was a certain childishness about her as she spoke infinitely touching.

"She is not happy," said the Electress gently. "Who could be in such times as these? Who could be, cast from their home and their country? But we will find an establishment for her."

Frederic smiled kindly at the little refugee.

"She deserves good fortune, this fair heretic," he said.

Charlotte looked at the Prince, who was gazing at her very intently; he was recalling that morning, early in the year, soon after he had entered France, and how she had ridden by, an abbess with her train of nuns...and how she, even then, had wished him "God speed" on his perilous adventure.

Seeing his eyes on her she flushed, but her gaze was steady.

"What great talk have we interrupted with our coming?" she asked seriously.

The Elector shook his head.

"The Prince has said nothing. You must use your persuasions to make him talk, Mademoiselle."

"What of?" smiled William. "I have long since become rusty in subjects interesting to a lady's ears."

Charlotte looked at him gravely; he was impressed now, as he had been when he had seen her last, by a certain nobility in her face.

"Your Highness must not dismiss us as trifles now," she said. "Women can be of use, even in these times. We have changed as the men have changed—is it not so, Madame?" She turned to the Electress.

"At least we understand," was the gentle answer.

"Your Highness would never realize how we have followed your exploits, waited for news, hoped, prayed—and blessed you, Prince, you and Count Louis and Count John and all who fight."

William, looking at these two earnest and intelligent women, thought of the wife who still bore his name, the woman who had insulted him and his cause, who had deserted him and his faith and stooped to a low intrigue with one scarce a gentleman.

The pain of this thought caused him to turn away abruptly; he walked to the wide hearth, then turned again, facing the three.

None of them could have guessed his secret disease, but all saw the sudden cloud on his face and a little silence fell.

It was the Princess Charlotte who broke it; she did what was to William an amazing thing. She turned quietly to Frederic.

"How many men can you raise for his Highness?" she said.

William started to hear the question that had been so insistently in his own mind, started to hear her ask so quietly the question he, a Prince, had not cared to ask.

The Elector looked at her straightly, almost with a challenge.

"Who told you, Mademoiselle," he asked, "that I proposed to raise a levy for the Prince of Orange?" She answered simply:

"I was sure you would help to your utmost, Highness." She smiled as she added, "The Duke Christopher is eager to go."

"Ah, he has no secrets from you, eh?" smiled the Elector.

"I do not know his secrets, Highness, only this, that he is eager to volunteer under the Prince of Orange."

"Well, better that than to spend his life in sloth," he answered.

"And how many men can the Palatinate raise?" asked Charlotte.

"She has a courage," remarked the Electress with a smile.

"What courage?" asked Charlotte; she too was smiling. "Is it not true that the Elector is a Protestant Prince—and is it not true," she turned shyly to William, "that His Highness requires men for his campaign against Alva in the Netherlands?"

William had been watching this little scene with an intent curiosity.

"It is very true," he answered at once. "How can I thank my gracious advocate?"

"Thank the Elector," said Charlotte, "when he has given you the levy—and now a good night, for I have had my say. Before your going I shall see your Highness."

She took the arm of the Electress and the two were gone as quickly and unceremoniously as they had entered. Frederic turned to William.

"I will help you to the best of my power," he said, and held out his hand.

Charlotte left the Electress and ran up to her own chamber, where Rénée le Meuny sat by the fire.

"I have seen him," said Charlotte.

"The Prince?" Rénée looked up.

"Yes."

"I thought that he was here secretly and would see no one but the Elector," said Rénée slowly.

"What did you think of him?" she asked with reluctance.

Charlotte answered gravely.

"He is such as I should wish to marry, to serve and be with always."

They met again, the Prince and Charlotte de Bourbon; he, who was used to only a few hours' sleep, was up almost with the early spring dawn; the day was sunny and misty after yesterday's rain; she and Rénée were walking in the garden when the Prince found them.

At sight of him the waiting-woman withdrew herself, as she had withdrawn herself all her life, but her step was heavy and her shoulders drooped as she went.

The Princess greeted him with her simple serenity, trained to be composed and distant in graciousness.

"I wished to see you again, Mademoiselle," said William.

They fell into step side by side, walking slowly between the flower beds where the snowdrops showed beneath the bushes.

"You leave soon?" asked Charlotte.

"In a few hours."

"Your Highness is not long in any one place," she smiled. "No—an exile's life!"

"We are both exiles," said Charlotte, "and for the same cause."

"Tell me," he asked, "how you came to this great resolution, Mademoiselle, to leave all?"

It did indeed seem strange to him that she, a mere girl, should have dared to break her bonds, her vows, and return to the world from which she had been forever excluded and embrace the faith that was one with damnation to her people and her kin.

He was puzzled also because he did not see in her any great energy or force of character, she seemed rather simple and conformed.

Yet she had done this thing, uninfluenced and unaided.

"I never wished to be a nun," she answered. "When I took my vows I made a protest before the Novices. I was then eleven years old. I loathed the life—from the first."

"And you heard of what was taking place in the world?"

"A little. Something of this great new freedom that was coming—something of the great conflict in France—of what the Queen of Navarre and the Elector were doing, and my sister's lord, Monsieur de Bouillon. I thought it was the moment to free myself."

"And you left everything?"

She looked up at him as if she did not understand his meaning.

"I mean you lost your inheritance, your country and your home? Is this not so, Mademoiselle?" insisted William.

"Has not your Highness lost as much, and more?" she replied.

"Oh, I!" he smiled.

She continued looking at him, knitting her brows in the earnestness of her speech.

"And your life must have been pleasant, was it not?"

"Yes, I think it was, Mademoiselle."

"While mine was hateful to me—so mine was a very little sacrifice beside yours," said the Princess.

"And you," smiled William, "are a very little person beside me—and half my years."

"But Monsieur, you think me very foolish?"

"I wonder at you. I know what it was to break from all custom, old tradition—to renounce all that one had hitherto held sacred."

"But I," said Charlotte, "had never felt these things sacred."

"No?"

"No," repeated the Princess. "I thought we all have the right to our own lives always—and freedom—I never believed in priests and I always thought one faith as good as another and the Reformed Faith a deal more convenient. And I never could believe the plaster statues were the Mothers of God, or the little wax Christmas babies Our Lord."

In these words, spoken with great earnestness, he saw now her strength, the calm force of her steadfast character, her common-sense view, undazzled by tradition; the simplicity of her character pleased his mind, itself so tortured by a thousand intricacies of thought, and the boldness of her outlook a little amazed him, accustomed as he was to numberless sophistries and hesitations, both in his own innermost beliefs and those of the men whom he dealt with.

"And you have never repented your step, Mademoiselle?" he asked.

"Oh, no. I am happy here."

Yet he saw that she was no enthusiast for the cause to which she had given such singular evidence of devotion.

"The religion was the excuse to leave the nun's life?"

"Yes," said Charlotte slowly, "had I not been forced to be a nun I might have been content with the old faith. My whole sympathy, though, is with the Protestants and I shall ever be a true professor of their faith."

He believed her; there was great loyalty, he saw, in her character, she would be very sincere in all her dealings.

They came to a little stone seat beneath an ash tree just covered with the first black buds and seated themselves. William found it pleasant to look at her, and as he looked a sense of her sweetness touched him very deeply; he imagined her as the centre of a home, as the mother of children, and the thought came to him—"If I had had such a woman these last years, how different my life would have been."

He spoke, prompted by these thoughts.

"Now you are in the world, Mademoiselle, you will do as the world does?"

She did not affect to misunderstand him.

"I wish to marry, Monsieur, when the time comes that one I can admire wishes for me, and to help in making life easy for one of your fighting men. But I am dowerless," she added with a smile.

"He who weds you will not look for a dowry," said William. "You have heard of my brother, Count Louis, and his admiration of you?"

"I have seen him," she answered. "He is not my suitor, Highness."

"Not openly as yet, he is afraid, because he has so little to offer."

She shook her head sadly.

"Too much for me to accept."

"Nay, in worldly gear nothing," said William, "but in himself he is a knight for any maiden's dreams, Mademoiselle."

"I do believe it," she answered simply.

She looked round at him; he was gazing at her and as their glances met she faintly coloured, but her eyes continued steadfast.

They were a strange contrast, she in her youth' and candour, in her spotless gown and linen, he in his worn maturity, his shabby clothes, his dark face sad and thoughtful, his reserved manner, his courtesy; yet they had something in common, for each had flung aside the shackles life had hung on them and now stood free.

And each nursed a dream; and though his was to free a nation, establish a religion and enthrone freedom securely in Europe, and hers was but to have her own house and her man to tend and her baby in her arms, still each was equally sincere, equally passionate, and this gave them in common the steadfastness imparted by a burning desire and a deep resolve.

For even as William meant to accomplish his tremendous aims, so Charlotte meant to accomplish her hidden hopes, but while he was active she was passive, while he strove she waited.

"If it should be Count Louis," he said, "I should be glad."

"I thank you for that," she answered, "but you speak of what is not in the hearts of either of us, Monseigneur."

While he was silent she spoke again, as if she had completely dismissed Count Louis from her thoughts. "Your Highness leaves here to-day?"

"Yes."

His face became graver; he had allowed himself this rare interval of distraction, with a feeling of relief, and now he thought with distaste upon the resumption of his task: "If I had my own home," he thought strangely, "this work of mine would seem different to me."

The thoughts of the Princess were working on different lines.

She leant forward a little, greatly interested.

"Your Highness has hopes from my country?"

"France could do everything."

"Alas, that my people are Catholic and on the side of your Highness's enemies."

"At least you are not," he said.

He put out his hand and took hers.

"You are my friend, are you not? Mademoiselle, good wishes such as yours do help as well as armies."

"But I would rather give you the armies," she smiled, colouring a little and letting her hand lie in his while she looked at him with her truthful eyes.

He kissed the fingers he held, then rose.

"I hope you will have good news of me," he said, "but you must expect bad, Mademoiselle. Meanwhile my pleasant hours pass, and I must leave Heidelberg."

She rose also and they looked at each other wistfully, as it they had more to say than words could at that moment express.

Then they parted.

He returned to the Castle to take his leave and Charlotte remained in the garden.

The bright sunshine of the early day had now changed into a fitful light obscured by clouds, the air became chilly and the Princess drew her wrap closer.

Presently she began gathering the snowdrops and Rénée, who had not returned to the palace, now perceived she was alone and joined her.

"The Prince has gone?" she asked.

"He has left to take his leave of the Elector," replied Charlotte.

She showed Rénée her flowers, but the other woman looked at the Princess and disliked her serene face.

"What a life is this!" she exclaimed.

Charlotte gave her a glance of surprise.

"You are tired of Heidelberg?"

"Tired of life."

"Why?"

"Your Highness would not understand."

"I do not know," replied Charlotte gravely. "I understand what it is to be dull and unhappy; you forget how many years I was a nun."

Rénée laughed bitterly.

"For longer years I have been a waiting-woman, exiled, dependent on charity."

"It is a weary life—it must be," said the Princess gently. Rénée was surprised, but not softened by her sympathy. "I think I will end it," she said with a sigh.

"How can you?"

"Some way—any way—I could return to the Netherlands—even on foot, and die as others are dying, every day."

"You serve better by waiting—the tide will turn—perhaps soon."

"I am tired of waiting," said Rénée passionately.

"I know—I know how tired I was, of the eventless life, the even days."

"But your Highness," said Rénée, "had the fortune to gain release."

"I had to make my own fortune."

"But you were a Princess, with powerful friends. I have no one. I am so obscure no one cares if I live or die; why should they, since neither my living nor dying can make any difference to any one."

She turned away abruptly, but not before the Princess had seen the tears in her eyes.

Charlotte put her hand on the elder woman's sleeve, and spoke, without attempting to look into her averted face.

"I do not know your special grief," she said gently, "but if it is mere loneliness—I know indeed what you suffer—believe me."

She paused a moment, then added sadly—

"Do you suppose that I am happy? Am I not also dependent on charity? Are these kind people my people? or even of my nation? I also am hopeless, penniless, cast out."

Rénée was silent.

"If ever," continued the Princess simply, "I should have the happiness to have a home, you shall share it."

Rénée turned and looked at her wildly.

"Truly your Highness does not understand," she said in a low voice. "Your Highness must forgive me—I am not well to-day. These winds give me pains in my head—I speak more than I mean and of things I do not understand how to express."

She moved away; Charlotte, looking after, shook her head.

More than once this barrier had come between them, friendly as they had been during their short acquaintance. Charlotte did not know, though Rénée did, that it was the difference in their natures that came between them, Charlotte was incapable of feeling passion or even of understanding it, and Rénée was capable of assuming, but not of feeling, the calm serenity that maintained the Princess through all her misfortunes.

Charlotte returned to the Castle and went to join the Electress in the still-room.

She did not even know exactly the hour when the Prince left the Castle, but Rénée was at an upper window watching for his departure.

She saw him ride away, wrapped in the shabby cloak, and her gaze followed him until the walls of Heidelberg hid him from her view.

And her heart ached after him with a great and intolerable yearning.

If she could have ridden behind him—as his foot-boy—as his slave, if she could be with him, to soften ever so little his troubles and discomforts—

But she was—as ever, useless.

And now he had gone and she must live on rumours again, such scraps of news as she could gather from people who never considered that she had any special interest in, or right to know of, the doings of William of Orange.

Long she remained looking from the window, gazing at the dull grey clouds that now filled the sky.

She recalled other times when she had watched him ride forth from his house in Brussels—his attire, his gay face, the gentlemen who had crowded round him, men who had all fallen victims to the wrath and the guile of Philip.

Egmont and Hoorne, who had died by public execution in the market-place, Berghen and Floris Montmorency, inveigled to Spain and strangled or poisoned in Spanish jails, Hoogstraaten and Adolphus of Nassau dead in battle, poor brave Brederode dead of a broken heart, who now was left of all those gallant nobles who had defied the tyrant king and the bigot priest? None save these two ruined men, William and Louis of Nassau.

"And how long have they?" thought Rénée, "for they also are under the ban of Spain."

She trembled for the lonely rider she had just seen depart and the tears washed the tired eyes that had so often wept for the Netherlands and William of Orange.

William, acting on a change of humour prompted AM, his visit to Heidelberg, decided not to go to Dillenburg.

The sight of those dear to him, his motherless children, the wreck of his once princely establishment, always disturbed him—now he felt he would not face them—and with empty news as always—to talk of further need of money, to demand new sacrifices from those who had already sacrificed almost everything—to be reminded, most painfully, of his mad wife and his son a prisoner in the hands of Philip.

This time he would avoid these things.

He turned aside instead to a little village on the edge of the Nassau lands and went to the house of a certain miller who was one of his agents; with great labour William had constructed an elaborate system of spies and agents in Germany, France and even the Netherlands and Spain; he had been trained by Charles V and was no novice in ways of guile, he even had his emissary in the very cabinet of Philip.

It was to pay for these things that he wore a threadbare suit and rode a worn hack.

One of his posts or messengers was waiting at the mill for news, on meeting the Prince in person, he handed him a packet in cipher that had come slowly from Spain, having been slipped secretly from one faithful hand to another.

William finished the letter to his brother that had been interrupted by the entrance of Rénée le Meuny and added a postscript telling of his whereabouts and asking Count John to come there and see him—"as for the moment I have no courage for Dillenburg."

He sent this on by the messenger who had brought him the news from Spain and took up his lodging in the mill-house.

The place was curiously peaceful with that sense of utter detachment from the world found in some rustic spots that are unvisited by change or trouble.

Behind, the hill rose to a little forest of chestnut and briar hedges where the first wild roses showed; a little vineyard and a little vegetable garden were attached to the house, both, at present, bare, with the fresh earth newly turned.

The mill-wheel, dark and dripping with weeds and slime, stood the other side of the house where the stream rushed past the rock on which the building stood.

Here the Prince must pass the empty hours, looking up at the high line of the bare chestnut trees against the cold blue sky, or down at the racing water.

Here, seated on a fallen log, he read the letter from Spain.

It told him little or nothing that he had not known or guessed before.

Spain was full of unrest, the King was desperately in want of money, the people were bent beneath the load of taxation, the Court favourites absorbed all, Philip was driven by the monks—"like a blinded mule."

Yet, as William knew, the King had his secret obstinate principles and ideas from which not even monks could have moved him.

If the Pope himself had preached tolerance and mercy, Philip would have given no heed, but would have quoted the council of Trent as the yardstick by which to measure Christians and have gone his way.

His was the terrible strength of bigotry, of a nature unbalanced by unlimited power, his was the unswerving purpose of a nature corrupt and cruel to the inmost fibre, the diseased, half-insane product of a degenerate race.

William had never deceived himself into thinking of Philip as a puppet in the hands of men like Granvelle and Alva or women like the Princess of Eboli—Philip in himself was terrible, awful and greatly to be feared.

His personal, ceaseless industry had woven the nets that had caught the grandees of the Netherlands, his personal flattery had lured Egmont to the block and Berghen to his secret death, his personal wish had forced the Inquisition on the Netherlands and imposed those edicts which had made a hideous ruin of a prosperous country and condemned to deaths of a horror unspeakable thousands of those innocent of all save the desire of liberty of conscience.

He had had willing, greedy and unscrupulous tools, but the mainspring of all their actions had been his own inexorable will, his unfaltering command, his pitiless intrigue, his insatiable cruelty.

Behind Alva, as behind Granvelle, was always Philip.

William knew that he had to struggle with Philip of Spain, that thin precise figure with the white face and reddish hair and beard, the bright blue eyes, and the under-hanging jaw that he had known in the old days when he was friend and favourite of Charles V.

What use the corruption, the faction, the intrigue, the financial embarrassments of Spain while Philip continued her unquestioned ruler—his narrow policies might involve in ruin his own empire as well as the countries subject to him, but they would never yield.

No peace, no agreement could ever be come to with Philip, who "would rather lose all his dominions than see them peopled with heretics," and who would never spare even his own in pursuance of his inflexible resolves, as he had not spared his miserable son. William had long ago faced this, he was fighting a foe who had stripped him of everything and was using infinite pains to deprive him of life itself. To fight Philip was like fighting wind and tide in a rudderless boat.

Yet the Prince of Orange never faltered in his belief that it could be done.

He slowly read the letter which contained details of the recent death of Hoorne's brother, Montigny.

The gallant young Netherlander, after long enduring the torture of a Spanish jail, had been secretly executed on the eve of Philip's third wife's entry into Spain.

The king knew that the dowager Countess of Hoorne had besought this bride, the Austrian Princess, to ask her son's life as a first favour from her husband and he had forestalled her petition.

William folded up the paper and stared down into the swirling mill-stream.

A slow colour mounted into his face; Montigny had been his friend—well he recalled him, young, honourable, and impetuous.

A brilliant life, full of promise—and because he had defied Philip it had ended in the executioner putting the cord round his neck.

William mused bitterly; he wondered, if ever he should even partially succeed, whether any of his friends would be there to rejoice with him.

Even now there were so few...he felt curiously lonely; yet if only they left him Louis, his beloved brother, and Henry, the boy who had so eagerly followed the fortunes of his elders, and John, the faithful and loyal—

Could these but remain there might yet be happiness snatched from bereavement.

He wished Louis would marry, and, thinking this, he thought of Charlotte de Bourbon.

She would make a man happy in his home; she was formed for that; his mind dwelt on her with great tenderness.

He had no passion to give any woman now—but he might need a wife. At this reflection he smiled to himself—she a renegade, a runaway nun, he a homeless exile.

And his wife lived, disgraced, mad, repudiated, she yet lived.

He thought of her with no pity; that loveless marriage of convenience had burnt itself out into bitter ashes indeed and he could rake no spark of sympathy nor kindness from them; but he thought of her son Maurice with affection—his only son, since that poor prisoner in Spain was dead to him and to the Netherlanders.

But Maurice "who may live to complete what I can scarcely begin"—William dwelt on him with pride—a fine boy, and again he thought, he and the others would be better for a home.

Count John came to the mill as fast as his horse could carry him, but the time of waiting had seemed long to William, who almost regretted that he had not pushed on to Dillenburg.

They met outside the mill-house, on the rocky banks of the stream.

John of Nassau was the most ordinary member of his house, he had neither the genius of his elder nor fire of his younger brothers, but he was dearly loved by all, and his character, loyal and courageous, was felt by them to be something always stable and unchanging in the midst of their shifting and desperate fortunes.

They could always turn to John, keeping up the home at Dillenburg, offering asylum and protection to the weaker members of the family, supplying what assistance he could.

He was not, perhaps, the man to have done what William and Louis had done, but rather one to go peacefully with the tide, but this made his self-sacrifice the finer, for he had practically ruined himself for the cause which his brothers had embraced and staked all, without a complaint, in a quarrel that was none of his seeking.

The Prince often thought, with a gratitude that was not unlike remorse, of what the quiet John had done for him without a thought of recompense or return and in his heavy moments it seemed to him as if he had dragged the whole of his family into an undeserved ruin.

The brothers sat down on the short dry grass.

"It is so dark in those small rooms," said William, "and I have grown enamoured of the open air."

He asked after all at Dillenburg, and John answered with an eagerness that was almost impatience; it was plain that he had great news to impart.

"You have something to tell me?" asked the Prince keenly.

"Something that you should have known before," replied the other with a certain reproach, "but you keep us so short of news—we know not of your whereabouts from one week to another."

"It is not so easy to send messengers," said William, "wandering as I do in disguise from place to place through unfriendly countries. Now give me your news."

His worn face slightly flushed in response to the obvious excitement of his brother's.

"Guess," said John, "from where it comes."

"From England?"

"Nay, their game is too cautious, they play but for their own profit—it is no great nation, but your Sea Beggars who have brought you fortune."

"The Sea Beggars!" said William, and the light died from his eyes.

He had no faith in these pirates who sailed his flag and held his charter and had long since dismissed them from his mind as of no profit and some disgrace to his cause.

Under his right as a sovereign Prince he had some years ago issued "letters of mark" to a number of Netherland nobles, with the idea that the ships they commanded would form the nucleus of a navy to annoy Philip and defend the Low Countries.

But his mandates had been disobeyed and his authority defied, and the Sea Beggars, as they called themselves, had degenerated into pirates, whose excesses had dishonoured their flag and whose plunder went no further than their own pockets.

The last that William had heard of them was that Elizabeth of England, in deference either to the continued protests of Philip, or because of the behaviour of the pirates themselves, had closed her ports to them and that they were, henceforth, without harbours or any refuge, but compelled to remain on the High Seas, without a base, and depending on coast raids, and now his brother told him that these ruffians, lately reduced to desperation, had brought him fortune.

"I had not looked to hear good news from De la Marck," smiled William.

John laid his hand on his brother's shabby sleeve. "He has descended on Brill—captured the Spanish garrison, received the keys in your name and hoisted your flag."

William coloured swiftly.

"De la Marck has done this?" he exclaimed, and he thought of the despair and contempt with which he had hitherto regarded his Admiral—as a useless instrument he had always considered him.

"Yes. We have now a base in the Netherlands, a town we can call our own. It is a great thing—the turning of the tide."

For one moment William shared his brother's enthusiasm; he saw this success as the beginning of a real change of fortune—himself taking up, by will of the people, the former stadtholderships he had held, Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht—then his native prudence, strengthened by so many disappointments, cast down his spirits.

"Can one trust De la Marck or his Beggars?" he asked sadly. "The thing is hasty, I will not build on it. I have better hopes in this tax of Alva, which he is resolved to enforce and which greatly rouses the Netherlands."

"That also works in our favour," agreed John. "There has not been so much dissatisfaction since Alva began to rule."

"That I count on—not on De la Marck!"

"But you are wrong," said John earnestly. "Have you heard Louis' news?"

"He is still at La Rochelle?"

"No—but descending into the Netherlands on Mons—he too, they say, called the Beggars hasty, but he is endeavouring to follow up their success, I believe he has affected some agreement with the French Huguenots, but his letters are brief."

William sat thoughtful.

"Louis was ever sanguine," he said, "and so he would fall on Mons, eh?"

"And you?" asked John.

"You would ask what I have done? I rely on Coligny, John—he is a great power, and may bring a quarter of France to our aid, the Protestant faction is strong there."

"And the King—the Queen-Mother?"

"I believe that they may think it wise to conclude a Protestant alliance—the marriage between the King's sister and the King of Navarre seems likely to be accomplished."

"You trust them?"

"Nay,—but I believe that expediency will force them to act in our interests—and on Coligny I do rely."

"What will you do?" asked John.

"I must a little while consider," replied the Prince; he rose, "let us into the house."

As they turned towards the mill he spoke again and abruptly.

"What of the Princess—Anne my wife?"

"She is at Beilstein still, under restraint—partially."

"She should be wholly so—we maintain her?"

"Yes—it is a heavy drain, William, her mad fancies cost dearly."