RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

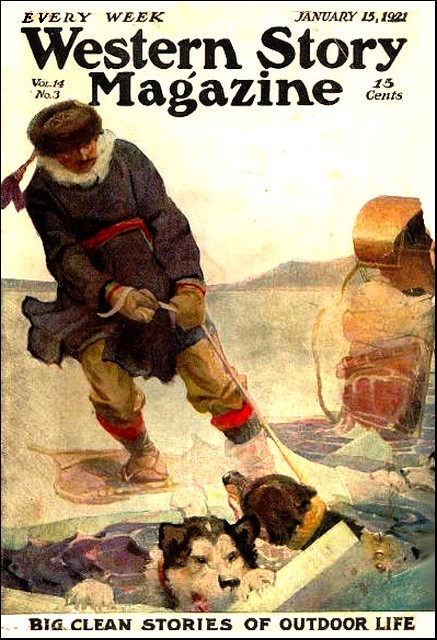

Western Story Magazine, January 15, 1921, with "The Cure of Silver Cañon"

THIS is a story of how Lew Carney made friends with the law. It must not be assumed that Lew was an outcast; neither that he was an underhanded violator of constituted authority. As a matter of fact there was one law which Lew always held in the highest esteem. He never varied from the prescriptions of that law; he never, as far as possible, allowed anyone near him to violate that law. Unfortunately that law was the will of Lew Carney.

He was born with sandy hair which reared up at off angles all over his head; his eyes were a bright blue as pale as fire. Since the beginning of time there has never been a man, with sandy hair and those pale, bright eyes, who has not trodden on the toes of the powers that be. Carney was that type and more than that type. Not that he had a taint of malice in his five-feet-ten of wire-strung muscle; not that he loved trouble; but he was so constituted that what he liked, he coveted with a passion for possession; and what he disliked, he hated with consummate loathing. There was no intermediate state. Consider a man of these parts, equipped in addition with an eye that never was clouded by the most furious of his passions and a hand which never shook in a crisis, and it is easy to understand why Lew Carney was regarded by the pillars of society with suspicion.

In a community where men shoulder one another in crowds, his fiery soul would have started a conflagration before he got well into his teens; but by the grace of the Lord, Lew Carney was placed in the mountain desert, in a region where even the buzzard strains its eyes looking from one town to the next, and where the wary stranger travels like a ship at sea, by compass. Here Lew Carney had plenty of room to circulate without growing heated by friction to the danger point. Even with these advantages, the spark of excitement had snapped into his eyes a good many times. He might have become a refugee long before, had it not chanced that the men whom he crossed were not themselves wholly desirable citizens. Yet the time was sure to come when, hating work and loving action, he would find his hands full. Some day a death would be laid to his door, and then—the end.

He was the gayest rider between the Sierras and the Rockies and one of the most reckless. There was no desert which he would not dare; there was no privation which he had not endured to reach the ends of his own pleasure; but not the most intimate of Lew's best friends could name a single pang which he had undergone for the sake of honest labor. But for that matter, he did not have to work. With a face for poker and hands for the same game, he never lacked the sources of supply.

Lew was about to extinguish his camp fire on this strange night in Silver Cañon. He had finished his cooking and eaten his meal hurriedly and without pleasure, for this was a dry camp. The fire had dwindled to a few black embers and one central heart of red which tossed up a tongue of yellow flame intermittently. At each flash there was illumined only one feature. First, a narrow, fleshless chin. Who is it that speaks of the fighting jaw of the bull terrier? Then a thin-lipped mouth, with the lean cheeks and the deep-set, glowing eyes. And lastly the wild hair, thrusting up askew. It made him look, even on this hushed night, as though a wind were blowing in his face. On the whole it was a rather handsome face, but men would be apt to appreciate its qualities more than women. Lew scooped up a handful of sand and swept it across the fire. The night settled around him.

But the night had its own illumination. The moon, which had been struggling, as a sickly circle through the ground haze, now moved higher and took on its own proper color, an indescribable crystal white; and it was easy to understand why this valley had the singular name of Silver Cañon. In the day it was a burning gulch not more than five miles wide, a hundred miles long, banked in with low, steep-sided mountains in unbroken walls. Under the sun it was pale, sand-yellow, both mountains and valley floor, but the moon changed it, gilded it, and made it a miracle of silver.

The night was coming on crisp and cold, for the elevation was great. But in spite of his long ride Carney postponed his sleep. He wrapped himself in his blankets and sat up to see. Not much for anyone to see except a poet, for both earth and sky were a pale, bright silver, and the moon was the only living thing in heaven or on earth. His horse, a wise old gelding with an ugly head and muscles of leather, seemed to feel the silence. For he came from his wretched hunt after dead grass and stood behind the master. But the master paid no attention. He was squinting into nothingness and seeing. He was harkening to silence and hearing. A sound which the ear of a wolf could hardly catch came to him; he knew that there were rabbits. He listened again, a wavering pulse of noise; far off was a coyote. And yet both those sounds combined did not make up the volume of a hushed whisper. They were unheard rhythms which are felt.

But what Lew Carney saw no man can say, no man who has not been stung with the fever of the desert. Perhaps he guessed at the stars behind the moon haze. Perhaps he thought of the buzzards far off, all-seeing, all-knowing, the dreadful prophets of the mountain desert. But whatever it was that the mind of Lew Carney perceived, his face under the moon was the face of a man who sees God. He had come from the gaming tables of Bogle Camp; tomorrow night he would be at the gaming tables in Cayuse; but here was an interval of silence between, and he gave himself to it as devoutly as he would give himself again to chuck-a-luck or poker.

Some moments went by. The horse stirred and went away, switching his tail. Yet Carney did not move. He was like an Indian in a trance. He was opening himself to that deadly hush with a pleasure more thrilling than cards and red-eye combined. Time at length entirely ceased for him. It might have been five minutes later; it might have been midnight; but he seemed to have drifted on a river into the heart of a new emotion.

And now he heard it for the first time.

Into the unutterable silence of the mountains a pulse of new sound had grown; he was suddenly aware that he had been hearing it ever since he first made camp, but not until it grew into an unmistakable thing did he fully awaken to it. He had not heard it because he did not expect it. He knew the mountain desert as a student knows a book; as a monk knows his cell; as a child knows its mother. It was the one thing on earth which he truly feared, and it was probably the only thing on earth which he really loved. The moment he made out the new thing, he stiffened under his blankets and canted his head down. The next instant he lay prone to catch the ground noise. And after lying there a moment, he started up and walked back and forth across a diameter of a hundred yards.

When he had finished his walk, he was plainly and deeply excited. He stood with his teeth clenched and his eyes working uneasily through the moon haze and piercing down the valley in the direction of Bogle Camp, far away. He even touched the handles of his gun and he found a friendly reassurance in their familiar grip. He went restlessly to the gelding and cursed him in a murmur. The horse pricked his ears at the well-known words.

But here was a strange thing in itself: Lew Carney lowering his voice because of some strange emotion.

The sound of his own voice seeming to trouble him, he started away from the horse and walked again in the hope of catching a different angle of the sound. He heard nothing new; it was always the same.

Now the sound was unmistakable; unquestionably it approached him. And to understand how the sound could approach for so long a time without the cause coming into view, it must be remembered that the air of the mountains at that altitude is very rare, and sound travels a long distance without appreciable diminution.

In itself the noise was far from dreadful. Yet the lone rider eventually retired to his blankets, wrapped himself in them securely, for fear that the chill of the night should numb his fighting muscles, and rested his revolver on his knee for action. He brushed his hand across his forehead, and the tips of his fingers came away wet. Lew Carney was in a cold perspiration of fear! And that was a fact which few men in the mountain desert would have believed.

He sat with his eyes glued through the moon haze down the valley, and his head canted to listen more intently. Once more it stopped; once more it began, a low, chuckling sound with a metallic rattling mixed in. And for a time it rumbled softly on toward him, and then again the sound was snuffed out as though it had turned a corner.

That was the gruesome part of it, the pauses in that noise. The continued sounds which one hears in a lonely house by night are unheeded; but the sounds which are varied by stealthy pauses chill the blood. That is the footstep approaching, pausing, listening, stealing on again.

The strange sound stole toward the waiting man, paused, and stole on again. But there are motives for stealth in a house. What motive was there in the open desert?

It was the very strangeness of it that sent the shudder through Lew. And presently he could feel the terror of that presence which was coming slowly down the valley. It went before, like the eye of a snake, and fascinated life into movelessness. Before he saw the thing that made the sound; while the murmur itself was but an undistinguished whisper; before all the revelations of the future. Lew Carney knew that the thing was evil. Just as he had heard the voices of certain men and hated them before he even saw their faces.

He was not a superstitious fellow. Far from it. His life had made him a canny, practical sort in the affairs of men; but it had also given him a searching alertness. He could smile while he faced a known danger; but an unknown thing unnerved him. Given an equal start, a third-rate gunfighter could have beaten Lew Carney to the draw at this moment and shot him full of holes.

Afterward he was to remember his nervous state and attribute much of what he saw and heard to the condition of his mind. In reality he was not in a state when delusions possess a man, but in a period of superpenetration.

In the meantime the sound approached. It grew from a murmur to a clear rumbling. It continued. It loomed on the ear of Carney as a large object looms on the eye. It possessed and overwhelmed him like a mountain thrust toward him from its base.

But for all his awareness the thing came upon him suddenly. Looking down the valley he saw, above a faint rise of ground, the black outline of a topped wagon between him and the moonlight horizon. He drew a great sobbing breath and then began to laugh with hysterical relief.

A wagon! He stood up to watch its coming. It was rather strange that a freighter should travel by night, however, but in those gold-rush days far stranger things had come within his ken.

The big wagon rocked fully into view; the chuckling was the play of the tall wheels on the hubs; the rattling was the stir of chains. Carney cursed and was suddenly aware of the blood running in old courses and a kindly warmth. But his relief was cut short. The wagon stopped in the very moment of coming over the rise.

Then he remembered the pauses in that sound before. What did it mean, these many stops? To breathe the horses! No horses that ever lived, no matter how exhausted, needed as many rests as this. In fact it would make their labor all the greater to have to start the load after they had drawn it a few steps. Not only that, but by the way the wagon rocked, even over the comparatively smooth sand of the desert, Carney felt assured that the wagon carried only a skeleton load. If it were heavily burdened, it would crunch its wheels deeply into the sand and come smoothly.

But the wagon started on again, not with a lurch, such as that of horses striking the collar and thrusting the load into sudden motion, but slowly, gradually, with pain, as though the motive power of this vehicle were exerting the pressure gradually and slowly increasing the momentum. It was close enough for him to note the pace, and he observed that the wagon crept forward by inches. Give a slow draft horse two tons of burden and he would go faster than that. What on earth was drawing the wagon through this moon haze in Silver Cañon?

If the distant mystery had troubled Lew Carney, the strange thing under his eyes was far more imposing. He sat down again as though he wished to shrink out of view, and once more he had his heavy gun resting its muzzle on his knee. The wagon had stopped again. And now he saw something that thrust the blood back into his heart and made his head swim. He refused to admit it. He refused to see it. He denied his own senses and sat with his eyes closed tightly. It was a childish thing to do, and perhaps the long expectancy of that waiting had unnerved the man a little.

But there he sat with his eyes stubbornly shut, while the chuckling of the wagon began again, continued, drew near, and finally stopped close to him.

Then at last he looked, and the thing which he guessed before was now an indubitable fact. Plainly silhouetted by the brilUant moon, he saw the tall wagon drawn by eight men, working in teams of two, like horses. And behind the wagon was a pair of heavy horses pulling nothing at all!

No, they were idly tethered to the rear of the vehicle. Weak horses, exhausted by work! No, the moon glinted on the well-rounded sides, and when they stepped the sand quivered under their weight. Moreover they threw their feet as they walked, a sure sign by which the drait horse can always be distinguished. He plants his feet with abandon. He cares not what he strikes as long as he can drive his iron-shod toes down to firm ground and, secure of his purchase, send his vast weight into the collar. Such was the step of these horses, and when the wagon stopped they surged forward until their breasts struck the rear of the schooner. Not the manner of tired horses, which halt the instant the tension on the halter is released! Not the manner of balky horses, either, this eagerness on the rope!

But there before the eyes of Lew Carney stood the impossible. Eight forms. Eight black silhouettes drooping with weariness before the wagon; and eight deformed shadows on the white sand at their feet; and two ponderous draft horses tethered behind.

It is not the very strange which shocks us. We are readily acclimated to the marvelous. But the small variations from the commonplace are what make us incredulous. How the world laughed when it was said that ships would one day travel without sails; that the human voice would carry three thousand miles! Yet those things could be understood. And later on there was little interest when men actually flew. The world was acclimated to the strange. But an unusual handwriting, a queer mark on the wall, a voice-like sound in the wind will startle and shock the most hard-headed. If that wagon had been seen by Lew Carney flying through the air, he probably would have yawned and gone to sleep. But he saw it on the firm ground drawn by eight men, and his heart quaked.

Not a sound had been spoken when they halted. And now they stood without a sound.

Yet Lew's gelding stood plainly in view, and he himself was not fifty feet away. To be sure they stood in their ranks without any head turning, yet beyond a shadow of a doubt they had seen him; they must see him. Still they did not speak.

In the mountain desert when men pass in the road, they pause and exchange greetings. It is not necessary that they be friends or even acquaintances. It is not necessary that they be reputable or respectable. It is not necessary that they have white skins. It suffices that a human being sees a human being in the wilderness and he rejoices in the sight. The sound of another man's voice can be a treasure beyond the price of gold!

But here stood eight men, weary, plainly in need of help, plainly scourged forward by some dreadful necessity, yet they did not send a single hail toward Lew.

No man among them spoke. The silence became terrible. If only one of them would roll a cigarette. At that moment the smell of burning tobacco would have taken a vast load off the shoulders of Lew Carney.

But the eight stirred neither hand nor foot. And each man stood as he had halted, his hands behind him, grasping the long chain.

HOW long they stood there Lew Carney could not guess. He only knew that a pulse began to thunder in his temple and his ears were filling with a roaring sound. This thing could not be, and yet there it was before his eyes.

It flashed into his mind that this might be some sort of foolish practical jest. Some wild prank of the cattlemen. But a single glance at the figures of the eight robbed him of this last remaining clue. Every line and angle of their bent heads and sagging bodies told of men taxed to the limit of endurance. The pride which keeps chins up was gone; the nerve force which allows a last few springy efforts of muscles was destroyed. Without a spoken signal. Like dumb brute beasts, the eight leaned softly forward, let the weight of their bodies come gently on the chain and remained slanting forward until the wagon stirred, the wheels turned, and the big vehicle started on. The sand was whispering as it curled around the broad rims of the wheels; that was the only sound in Silver Cañon.

Stupefied, Carney watched it go without relief. Another man might have been glad to have the mystery pass on but, after the first chill of fear. Lew began to hunger to get under the surface of this freak. Yet he did not move until there was a sudden darkening of the moonlight. Then he looked up.

As he did so he saw that the moon was obscured by a gray tinge, and he felt a sharp gust of wind in his face. Up the cañon toward Cayuse the air was thick with a dirty mist, and he knew that it was the coming of a sand storm.

That dismal reality brushed the thought of the wagon from his mind for a moment. He found a bit of shrubbery a hundred yards away and entrenched himself behind it to wait until the storm should pass over, and he might snatch some sleep. The horse, warned by these preparations, came close.

They were hardly finished before the blast of the wind had a million edges of flying sand grains. And a moment later the sand storm was raging well over them. Lew Carney, comfortable in his shelter except for the grit that forced itself down his neck, thought of the eight men and the wagon. Even in the storm he knew that they had not stopped, but were trudging wearily on. And if the wagon were halted and dragged back by the weight of the wind, still they would lean against the chain and struggle blindly. The imaginary picture of them became more vivid than the picture as they had stood in the moonlight.

It was not a really heavy blow. In two hours it was over; but it left the air dim, and when Lew peered up the valley the wagon was out of sight. For a time he banished the thought of it, wrapped himself again in the blankets, and was instantly asleep.

The first brightness of morning wakened him, and tumbling automatically out of his blankets, he set about the preparation of breakfast with a mind numbed by sleep. Not until the first swallow of scalding coffee had passed his lips did he remember the wagon, and then he started up and looked again at the valley. He rubbed his eyes, but it was nowhere in sight.

Ordinarily it would not seem strange that a night's travel, even at the slowest pace, should take a wagon out of sight, but Silver Cañon was by no means ordinary. Through the thin, clear air the eye could look from the place where Lew stood clear up the valley to the cleft between the two mountains thirty miles away, where Cayuse stood. There were no depressions to conceal any object of size, but the floor of the valley tilted gradually and smoothly up. To understand the clearness of that mountain air and the level nature of the valley, it may be remarked that men working mines high up of the sides of the mountains toward the base of Silver Cañon could see the camp fires of freighters on four successive nights, dwindling into stars on the fourth night, but plainly discernible through the four days of the journey. And a band of wild horses could be watched every moment of a fifty-mile run to the water holes, easily traced by the cloud of dust.

Bearing these things in mind, it can be understood why Lew Carney gasped as he stared up the valley and saw—nothing!

The big schooner had vanished into thin air or else it had reached Cayuse. This thought comforted him, but after a moment of thought he shook his head again. They could not have covered the thirty miles. Two hours' travel had been impossible against the storm. Deducting that time, there remained well under three hours. Certainly, the eight men pulling the wagon could not have covered a quarter of that distance in three hours or double three hours. And even if they had harnessed in the two big horses, the thing was still impossible. An hour of sharp trotting would have broken down those lumbering hulks of animals. And as for keeping up a rate of ten miles an hour for three hours with a lumbering wagon behind them and through soft sand, why it was something that a team of blooded horses, drawing a light buckboard, could hardly have accomplished.

The rest of Lew's breakfast was tossed away untasted. He packed his tins with a rattle and tumbled into the saddle, and presently the gelding was cantering softly toward Cayuse.

As he expected, the storm had blotted out all traces. There was not a sign of wheels; the sand, perfectly smooth except for long wind riffles, scrawled awkwardly here and there. Little hummocks had been tossed up around shrubs, but otherwise all was plainly in view, and the phantom wagon was nowhere on the horizon.

Of course, one possibility remained. They might have turned out of the main course of the valley and gone to one side, ignorant of the fact that those mountains were inaccessible to wagons. It required a horse with tricky feet, unhampered with any load, to climb those sliding, steep, sand surfaces. For the draft animals to attempt it with a wagon behind them was ludicrous. Yet he kept sweeping the hills on either side for some trace of the schooner, and always there was nothing.

As has been said, Lew was by no means superstitious, and now he had broad daylight to help steady his nerves and sharpen his faculties; yet in spite of broad daylight he began to feel once more the eerie thrill of the unearthly, and he felt that even if he had stepped out to examine the tracks of the wagon as soon as it passed him, he would have found nothing.

At this he smiled to himself and shook his head. A ghost wagon did not make eight men sweat and strain to pull it, and a ghost wagon did not rumble as it traveled and make a whispering of the sand. No, a solid wagon and eight solid human beings, and two heavy horses, somewhere between his last dry camp and Cayuse, had vanished utterly and were gone!

Searching the walls of the valley on either side, he almost neglected the floor of the cañon, and it was only the bright flash of metal that made him halt the gelding and look to his right and behind. He swung the mustang about and reached the spot in half a dozen jumps; a man lay with his arms thrown out crosswise, and a revolver was in his hand.

At first glance Carney thought that the fellow lived, but it was only the coloring effect of the morning sun and the lifting of his long hair in the wind.

He was quite dead. He had been dead for hours and hours it seemed. And here was another mystery added to the disappearance of the wagon. How did this body come here? What vehicle had carried the man here after he was wounded?

For, tearing away the bandages around his breast, Carney saw that he had been literally shot to pieces. The tight-drawn bandages, shutting off the flow of blood, perhaps, had bruised the flesh until it was a dark purple around the black shot holes.

One thing was certain: after those wounds the man had been incapable of travel on horseback. He must have been carried in a wagon. But certainly only one wagon had gone that way before the sand storm, and after the sand storm any vehicle would have left traces.

After all then, there had been some freight in the ghost wagon, and this man, perhaps dead at the time, had been part or all of the burden that passed under Lew's eyes.

But why had the wagon carried a dead body? And if it carried a dead body at all, why was it not taken on to the destination of the wagon itself? Certainly the burden of one man's weight was not enough to make any difference.

Two startling facts confronted him: first, here was a dead man; second, the dead man had been brought this far by the ghost wagon.

Here, also, was the chance of learning not only the identity of the dead man, but of the man who had killed him. Carney searched the pockets and brought out a wallet which contained half a dozen tiny nuggets of pure gold, nearly a hundred dollars in paper money, and a pencil stub. Evidence enough that robbery had not been the motive in this killing.

Besides the wallet, the pockets produced a strong knife, two boxes of matches, a blue handkerchief, a straight pipe, and a sack of tobacco.

There was no scrap of paper bearing a name; there was nothing distinctive about the clothes whereby the man could be identified. He was dressed in a pair of overalls badly frayed at the knees, with a smear of grease and an old stain of red paint, both on the right leg; also, he had on a battered felt hat and a blue shirt several sizes too large for him. In appearance he was simply a middle-aged man of average height and weight, with iron-gray hair, and hands broadened and callused by years of heavy labor. His face was singularly open and pleasant even in death, but it had no striking feature, no scar, no mole.

Carney stripped him to the waist and turned the body to examine the wounds, and then he straightened with a black look. It was not a man-to-man killing; it was murder, for the vital bullet which eventually robbed the man of life had struck him in the center of the back. By the small size of the wound he knew that the bullet had entered here, just as he could tell by the gaping orifice on the breast where the bullet had come out. Yet the man had not given up without a struggle. He had turned and fought his murderer, for there were other scars on the front. In five distinct places he had been struck, and it was only wonderful that he had not been instantly killed.

Had they carried him as far as this and, then discovering that he was indeed dead, flung his body brutally from the wagon for the buzzards to find? No, at the very latest he must have died within two hours of the reception of these wounds. He must have been dead long before he passed the dry camp of Lew Carney. But if they had carried him as far as this, what freak of folly made them throw the dead body, the brutal evidence of crime, in a place where the freighters were sure to find him inside of twelve hours?

It was reasoning in a circle. One thing at least was sure. The murderer and the men of the ghost wagon were confident that their traces could not be followed.

As for the body itself, there was nothing he could do. The freighters would take the man up and carry him to Cayuse where he would receive a decent burial. In the meantime, unless that wagon were indeed a ghost, it must have come by means however mysterious to Cayuse also. And toward that town Carney hurried on.

THE mountains went up on either side of Cayuse, but from each side it was easy of access. It gave out upon Silver Cañon in one direction, and on the other side there was a rambling cattle country. As for the mountains, they were better than either a natural highway or a range, for there was gold in them. Five weeks before it had been found; the rumor had gone roaring abroad on the mountain desert; and now, in lieu of echoes, a wild life was rushing back upon Cayuse.

Its population had been more than doubled, but by far the greater number of the newcomers paused only to outfit and lay in supplies before they pushed on to the gold front. The majority found nothing, but the few who succeeded were sufficient to send a steady stream of the yellow metal trickling back toward civilization. Of that stream a liberal portion never went farther than Cayuse before it changed hands. For one thing supplies were furnished here at doubled and redoubled prices; for another a crew of legal and illegal robbers came to this crossing of the ways, to hold up the miners.

In perfect justice it must be admitted that Lew Carney belonged to the robbers, though he was of the first class rather than the second. His sphere was the game table, and there he worked honestly enough, matching his wits against the wits of all comers, and trying his luck against the best and the worst. It meant a precarious source of livelihood, but in gambling a cold face and a keen eye will be served, and Lew Carney was able to win without cheating.

His first step after he arrived was to look over old places and new. He found that the main street of Cayuse was little changed. There were more people in the street, but the buildings had not been altered. Away from this established center, however, there was a growing crowd of tents that poured up a clamor of voices. Everywhere were the signs of the new prosperity. There stood half a dozen men pitching broad golden coins at a mark and accepting winnings and losses without a murmur. Here was a peddler with his pack between his feet, nearly empty. Everything from shoestrings to pocket mirrors, and hardly a man that passed but stopped to buy, for Cayuse had the buying fever.

Carney left the peddler to enter Bud Lockhart's place. It had been the main gaming hall and bar in the old days and, by attaching a lean-to at the rear of his house. Bud had expanded with the expanding times, and he was still the chief amusement center of Cayuse. In token of his new prosperity he no longer worked behind the counter. Two employees served the thirsty line; and in the room behind, stretching out into the lean-to, were the gaming tables.

As he entered, he saw a roulette wheel flash and wink at him, and then the subdued exclamations of the crowd as they won or lost. For the wheel fascinates a group of chance takers at the same time that it excites them. The eye of Carney shone. He knew well enough that where the wheel is patronized by a group, there is money to spend on every game. One more glance around the room was sufficient to assure him. There was not a vacant table, and there was not a table where the chips were not stacked high. Bud Lockhart came through the crowd straight toward Carney. He was a large man with a tanned face, which in its generous proportions matched his big body. What it lacked in height above the eyes it made up in the shape of a great, fleshy chin.

"Hey, Lew," called the big man, plowing his way among the others and leaving a disarranged but good-natured wake behind him. Carney turned and waited. "I need you, boy," said Bud Lockhart as he shook hands. "You've got to break your rule and work for me. How much?"

The gambler hesitated. "Oh, fifty a day," he murmured.

"Take you at that price," said the proprietor and Lew gasped.

"Is it coming in as fast as that?" he queried.

"Faster. Fast enough to make your head swim. The suckers are running in all day with each hand full of gold and they won't let me alone till they've dumped it into my pockets. I've got a lot of boys working for me but most of the lot are shady. They're double-crossing me and pocketing two-thirds of what they make. I need you here to take a table and watch the boys next to you."

"Fifty is pretty fat," admitted Carney, "but I think I'll do a little gold digging myself."

Bud gasped. "Say, son," he murmured, "have they stuck you up with one of their yarns? Are you going in with some greenhorn and collect some calluses on your hands?"

"No, I'm going to do my digging right in your place, Bud. You dig the coin out of the pockets of the other boys; I'll sit in a few of your games and see if I can't dig some of the same coin out again."

"Nothing in that," protested Bud Lockhart anxiously. "Besides you couldn't play a hand with these boys I have. I've imported 'em and they have the goods. Slick crowd, Lew. You've got a good face for the cards but these fellows read their minds!"

"I see," nodded Carney. "But there's ways of discouraging the shifty ones. Oh, they're raw about it, Bud. I saw that fat fellow who's dealing over there palm a card so slow I thought he was tryin' to amuse the crowd until I saw him take the pot. I think I could clean out that guy, Bud."

"Not when he's going good. You could never see him work when he tries."

"He wouldn't try the crooked stuff with me," remarked Carney. "Not twice, unless he packs along two lives."

"Easy," cautioned Lockhart. "None of that, Lew. I paid too much for my furniture to have you spoil it for me. Look here, you're grouchy today. Come behind the counter and have a drink of my private stock."

"This is my dry day. But what's the news? Who's been sliding into town? You keep track of 'em?"

"I'll tell a man I do! Got two boys out, workin' 'em as fast as they blow, and steerin' 'em down to my joy shop. Not a bad idea, eh?"

"What's come in today?"

The proprietor pulled out a little notebook and turned the pages with a fat forefinger.

"Up from Eastlake there was a gent called Benedict and another called Wayne; cowmen loaded with coin. They're unloading it right now. See that table in the corner? Then there was Hoe..."

"I don't know the lay of the land east of Cayuse," protested Lew Carney. "No friends of mine in that direction."

"Out of the mountains," began Bud, consulting his notebook again. "There was..."

"Cut out the mountains, too. What came out of Silver Cañon?"

"What always comes out of it? Sand." Bud's fat eyes became little slits of light as he grinned at his own jest.

He added: "Looking for somebody?"

"Not particular. Heard somebody down the street talk about a wagon that came off the desert with eight or nine men. What was that?" To conceal his agitation he began to roll a cigarette.

"One wagon?" asked Bud Lockhart.

"Yep."

"What'n thunder would eight men be doin' in one wagon?"

"I dunno."

Carney took out a match, scratched it and then lighted his cigarette hastily. Every nerve in his body was on edge, and he feared lest the trembling of his hand should be noticed.

"Eight men in one wagon," chuckled Bud. "Somebody's been kiddin' you, Lew. If this crowd has started kiddin' Lew Carney for amusement, it's got more nerve than I laid to it. But why's the wagon stuff eatin' on you, Lew?"

"Not a bit," said Carney. "Doesn't mean a thing but, when I heard that the wagon came off Silver Cañon, I thought it might be from my own country, might find a pal in the crowd."

"I'm learning something every day," Bud replied with a grin. "Makes me feel young again. Since when have you started in having pals?"

"Why shouldn't I have 'em?" retorted Carney sharply, for he felt that the conversation was not only unproductive but that he had aroused the suspicion of the big man.

"Because they don't last long enough," replied the other, with perfect good nature. "You wear 'em out too fast. There was young Kemple. You hooked up with him for a partner, and he comes back with a lump on his jaw and a twisted nose. Seems he disagreed with you about the road you two was to take. Then there was Billy Turner that was going to be your partner at poker. Two days later you shot Billy through the hip."

"He tried a bum deal on me, on his pal," said Carney grimly.

"I know. I told you before that Billy was no good. But there was Jud Hampton. Nobody had nothin' ag'in Jud. Fine fellow. Straight, square dealin'. You fell out with Jud and busted his..."

"Lockhart," snapped the smaller man, "you've got a fool way of talkin' sometimes."

"And right now is one of 'em, eh?"

"I've given you the figures," said Carney. "You can add 'em up any way you want to."

It was impossible to disturb the calm of big Bud. "So you're the gent who is lookin' for some pals?" he chuckled. "Say, Lew, are you pickin' trouble with me? Hunt it up some place else. And the next time you start pumpin' me, take lessons first. You do a pretty rough job of comin' to the wind of me."

A lean hand caught the arm of Bud as he turned away; lean fingers cut into his fat, soft flesh; and he found himself looking down into a face at once fierce and wistful. "Bud, you know something?"

"Not a thing, son, but it's a ten to one bet that you want to know something that's got a wagon and eight men in it. What's the good word?"

The knowledge that he had bungled his first bit of detective work so hopelessly made Lew Carney flush. "I've talked like a fool," he said. "And I'm sorry I've stepped on your toes, Bud."

"That's a pile for you to say," replied Bud. "And half of it was enough. Now what can I do for you?"

"The wagon..."

"Forget the wagon! I tell you, the only thing that's come in out of Silver Cañon is you. Hasn't my spotter been on the job? Why he give me a report on you yourself, the minute you blew in sight. What d'you think he said? 'Gent with windy lookin' hair. Rides slantin'. Kind of careless. Good hoss. Looks like he had a pile of coin and didn't care how he got rid of it.' It sure warmed me up to hear that kind of a description, and then in you come. 'There he is now,' says the spotter. 'Like his looks?' 'Sure,' says I. 'I like his looks so much you're fired.' That's what I said to him. You should've seen his face!"

The fat man burst into generous laughter at his own joke.

The voice of Lew Carney cut his mirth short. "I tell you, Bud, you're wrong. Either you're wrong or I'm crazy!"

"Don't be sayin' hard things about yourself," Lockhart retorted.

"It's gospel, is it?"

"It sure is."

"Then keep what I've said to yourself."

"Not a word out of me, Lew. Now let's get back to business. What you need to get this funny idea out of your head is a game..."

But the head of Lew Carney was whirling. Had he been mad? Had it been an illusion, that vision of the wagon and eight men? He remembered how tightly his nerves had been strung. A terrible fear for his own sanity began to haunt him.

"Blow the game," said Carney. "I'm goin' to get drunk!"

"I thought you said this was your dry..."

But the younger man had already whirled and was gone among the crowd. He went blindly into the thickest portion, and where men stood before him he shouldered them brutally out of the way. He left behind him a wake of black looks and clenched hands.

Bud Lockhart waited to see no more. He hurried to call one of his bartenders to one side.

"You see that gent with the sandy hair?" asked Bud.

"Yep."

"Know him?"

"Nope."

"He's Lew Carney and he's startin' to get drunk. I've known him a long time, and it's the first time I've ever heard of him goin' after the booze hard. Take him aside and give him some of my private stock. Keep a close eye on him, you hear? Pass the word around to all the boys. There's a few that knows him and they'll hunt cover if he starts goin'. But some of the greenhorns may get sore and try a hand with him. You're kind of new to these parts yourself, son. But take it from me straight that Lew Carney has a nervous hand and a straight eye. He starts quick and he shoots straight. Let him down as easy as you can. Put some tea in his whiskey if he's goin' too fast. And see that nobody touches him for his roll. And if he flops, have somebody put him to bed."

ALL of these things having been accomplished in the order named, with the single exception that the "roll" of Carney was untouched, the gambler awakened the next day with a confused memory and a vague sense that he had been the center of much action. But he had neither a hot throat nor a heavy head. In fact after the long nerve strain which preceded the drunk, the whiskey had served as a sort of counter poison. The brain of Lew Carney, when he wakened, was perfectly clear for the present. It was only a section of the past that was under the veil.

Through the haze, facts and faces began to come out, some dim, some vivid. He remembered, for instance, that there had been a slight commotion when news came that a freighter had brought in the body of a man found dead in Silver Cañon . He remembered that someone had jogged his arm and spilled his whiskey, whereupon he had smote the fellow upon the root of the nose and then waited calmly for the gun play. And how the other had reached for his gun but had been instantly seized by two bystanders who poured whispered words into his ears. The words had turned the face of the stranger pale and made his eyes grow big. He stared at Lew, then had apologized for the accident, and had been forgiven by Lew, and they had had many drinks together.

That was one of the incidents which was most vivid.

Then, somebody had insisted upon singing a solo, in a very deep, rough bass voice. Carney had complimented him and told him he had a voice like Niagara Falls.

A little, wizened man with buried eyes and hatchet face had confided to Carney that he was a Comanche chief and that he was on the warpath hunting white scalps; that he had a war cry which beat thunder a mile, and that when he whooped, people scattered. Whereupon he whooped and kept on whooping and swinging a bottle in lieu of a tomahawk until the bartender reached across the bar and tapped the Comanche chief with a mallet.

A tall, sad-faced man with long mustaches had poured forth the story of a gloomy life between drinks.

Once he had complained that the whiskey was too weak for him. What he wanted was liquid dynamite so he could get warmed up inside.

Later he was telling a story to which everyone listened with much amusement. Roars of laughter had greeted his telling of it. Men had clapped him on the back when he was finished. Only one man in the crowd had seemed serious.

Lew Carney began to smile to himself as he remembered the effect of his tale. The tale itself came back to him. It was about eight men pulling a wagon across the desert, while two horses were tethered behind it.

At this point in the restoration of the day before, Carney sat erect in his bed. He had told the story of the phantom wagon in a saloon full of men. The story would go abroad; the murderer or murderers of that man he had found dead in the desert would be warned in time.

He ground his teeth at the thought, but then settled himself back in the bed and, with a prodigious effort, summoned up other bits of the scene.

He remembered, for instance, that after he told the story, somebody had pressed through the crowd and assured him in a voice tearful that it was the tallest lie that had ever been voiced between the Sierras and the old Rockies. Whereat another man had said that there was one greater lie, and that was the old man Tomkins's story about the team of horses which was so fast that when a snowstorm overtook him in his buckboard, he put the whip on his team and arrived home without a bit of snow on him, though the back of his wagon was full to the top of the boards.

After that half a dozen men had insisted on having Carney drink with them. So he had poured six drinks into one tall glass and had drunk with them all, while the crowd cheered. After this incident he could remember almost nothing except that a strong arm had been beneath his shoulders part of the time, and that a voice at his ear had kept assuring him that it was "all right... don't worry... lemme take care of you."

Finding that past this point it was hopeless to try to reconstruct the past, he returned to the beginning, to the first telling of the tale of the wagon, and strove to make what had happened clearer. Bit by bit new things came to him. And then he came again in his memories to the man who had looked seriously, for one instant. It had been just a shadow of gloom that had crossed the face of this man. Then he had turned and gone through the crowd.

"By Heaven!" said Lew, to the silent walls of his room. "That gent knew something about the wagon!"

If he could recall the face of the man, he felt that two-thirds of the distance would have been covered toward finding the murderer, the cur who had shot the other man from behind. But the face was gone. It was a vague blur of which he remembered only a brown mustache, rather close-cropped. But there were a hundred such mustaches in Cayuse.

He got up and dressed slowly. He had come to the halting point. Dim and uncertain as this clue would be, even if the stranger actually had some connection with the murder, even if he had not been simply disgusted by the drunken tale, so that he turned and left in contempt. Yet in time his memory might clear, Carney felt, and the veil be lifted from the significant face of the man. It seemed as though the curtain of obscurity dropped just to the top of the mustache, like a mask. There was the strong chin, the contemptuous, stern mouth, and the brown mustache, cropped close. But of eyes and nose and forehead, he could remember nothing.

Downstairs he found that he had been the involuntary guest of Bud Lockhart overnight in the little lodging house; so he went to the big parlor to repay his host. Smiles greeted his entrance. He reduced his pace to the slowest sauntering and deliberately met each eye as he passed; the result was that the smiles died out, and he left a train of sober faces behind him.

With his self-confidence somewhat restored by this running of the gantlet, he found Bud Lockhart and was received with a grin which no amount of staring sufficed to wipe out. He discovered that Bud seemed actually to admire him for the drunken party of the day before.

"I'll tell you why," said Bud, "you get in solid with me. Some's got one test for a gent and some's got another. But for me, let me once get a gent drunk and I'll tell you all about how the insides of his head are put together. If a gent is noisy but keepin' his tongue down to make a bluff, he'll begin to shoutin' as soon as the red-eye is under his belt. And if he's yaller, he'll try to bully a fellow smaller than himself. And if he's a blowhard, he'll start his blowin'. But if he's a gentleman, sir, it's sure to crop out when the whiskey is spinning in his head."

At this Carney looked Bud in the eye with even more particular care.

"And after I knocked a man down and insulted another and told a lot of foolish stories, just where do you place me, Lockhart?"

"Do you remember that far back?" asked Bud with a chuckle. "Son, you put away enough whiskey to float a ship. You just simply got a nacheral ability to blot up the booze!"

"How much tea did you mix with my stuff?"

At this Bud flushed a little, but he replied: "Don't let 'em tell you anything about me. No matter what it was you drank, you put away just twice as much as was enough. Son, you done noble, and I tell it to you! You done noble. Only one fight, and seein' it was you, I'd say that you spent a plumb peaceable day."

"Bud," broke in the other, "I think I chattered some more about that ghost wagon. Did I?"

"Ghost wagon? What? Oh, sure, I remember it now. That funny idea of yours about seein' a wagon with eight men pullin' it? Sure, you told that yarn, but everybody put it down for just a yarn-and had a good laugh out of it. I suppose you've got that fool idea out of your head by this time, Lew? Good thing if you have!"

Lew Carney began to feel that there was far more generous manliness in Bud Lockhart than he had ever guessed.

"I'll tell you how it is," he said. "I'd put the thing out of my head if I could, but I can't. Know why? Because it's a fact."

The smile of the big man became somewhat stereotyped.

"Sure," he said. "Sure it's a fact."

"Are you tryin' to humor me?" asked Carney with a growl.

The older man suddenly took his friend by the arm and tapped his breast with a vast, confidential forefinger.

"Listen, son. The first time you pulled that story it was a swell joke, understand? The second time it won't get such a good hand. The third time people are apt to pass the wink when you start talking."

"But I tell you, man, I saw that thing as clearly..."

"Sure, sure you did. I don't doubt you, Lew. Not me. But some of the boys don't know you as well as I do. You'll start explainin' to 'em real serious, and then they'll pass the wink along. Savvy? They'll begin to tap their heads. You know what happened to Harry the Nut? Between you and me, I think he had just as good sense as you and me have. But he done that one queer thing over to Townsend's and when he tried to explain, it didn't do any good. Then pretty soon he was doin' nothin' but explainin' and tryin' to make people take him serious. You remember? And after a while he got to thinkin' about that one thing so much that I guess he did go sort of batty. It's an easy thing to do. I'll tell you what, Lew. If you can't figure out a thing, just start thinkin' about somethin' else. That's the way I do."

There was something at once so hearty and so sane about this advice that the young gambler nodded his head. He had a wild impulse to declare outright that he knew there was a close connection between the ghost wagon and the dead man whom the freighters had brought in the day before. But he checked himself on the verge of speech. For this tale would be even more difficult of explanation than the first.

Instead he took the big man's hand and made his own lean fingers sink into the soft fat ones of Bud Lockhart.

"You got a good head, Bud," he said, "and you got a good heart. I'm all for you and I'm glad you're for me. If you ever hear me talk about the ghost wagon again, you can make me eat the words."

The big man sighed and an expression of relief spread visibly across his face. Oil had been cast upon troubled waters.

"Now the thing for you is a little excitement, son," he advised. "Go over to that table. I'll bring you the stakes; and you start dealin' for the house."

"Whatever you say goes for me today," murmured Carney obediently.

"And as for the coin," said the fat man, "you just split it with the house any way you think is the right way."

ONLY half of the mind of Lew Carney was on the cards, and west of the Rockies it needs very close attention indeed to win at poker. Once he collared a fellow clumsily trying to hold out a card. At the urgent entreaty of Bud Lockhart to do him no serious damage, he merely threw him out of the place. Luck now inclined a little more to his side, when the men who took their chances at his table saw that they could not crook the cards; but still he lost for the house, steadily. He had an assignment of experienced and steady players, and the chances seemed to favor them.

By noon he was far behind. By mid-afternoon Bud Lockhart was seen to be lingering in the offing and biting his lip. Before evening Carney threw down the cards in disgust and went to his employer.

"I'm through," he said. "I can't play for another man. I can't keep my head on the game. I'll square up for what I've lost for you."

"You'll not," said Lockhart. "But if you think the luck ain't with you, well, luck takes her own time comin' around; and if the draw ain't with you, well, knock off for a while."

"I'm doin' it. S'long, Bud."

"Not leavin' the house, old man?"

The proprietor moved back before the door with his enormous arms outspread in protest. "Not goin' to beat it away right now, are you, Lew?"

"Why not? I want a change of air. Gettin' nervous."

"Sit down over there. Wait a minute. I'll get you a drink."

"Not now."

"Bah! You don't know what you need. Besides, I've got something to say to you."

He hurried away, turned.

"Don't move out of that chair," he directed, and Carney sank into it, as though impelled by the wind of the big man's gesture.

Once in it, however, he stirred uneasily. The events of the day before had served to make him a well-known character in the place. Wherever people moved, they often turned and directed a smile at the young gambler, and such glances irritated him. Not that the smiles were exactly offensive. Usually they were accompanied by some reference to the celebrated tale of the evening before, the amazing lie about the ghost wagon. Yet Carney felt his temper rise. He wanted to be away from this place. He did not know how many of these strangers he had drunk with the night before. Perhaps he had drunk with his hand on the shoulder of some. He had seen drunken men do that, and the thought made his flesh crawl. For Lew Carney was not in any respect a good democrat and there was very little society which he preferred to his own. Not that he was a snob, but his was a heart which went out very seldom, and then with a tide of selfless passion. And the faces in this room made him feel unclean himself. He dreaded touching his own cheek with the tips of his fingers for fear that he would feel the stubble left by the hasty shave of that morning.

Above all, at this moment, the thought of the vast flesh and the all-embracing kindliness of his host was irksome to him. He felt under an obligation for the night before, and the manner in which Lockhart had handled the delicate situation of the gambling losses deepened the obligation, made it a thing that a mere payment of cash could not balance. He had to stay there and wait for the return of Bud, and yet he could not stay! With a sudden, overmastering impulse, he started up from his chair and strode swiftly to the door.

His hand was upon the knob when a finger touched his shoulder. He turned; there stood Glory Patrick, the man who kept order in the parlor and gaming hall of Bud Lockhart. Glory was a known man whether with his bare hands or with a knife or gun. And Lew Carney had seen him working all three, at one time or another. He smiled kindly upon the rough man; his eyeteeth showed with his smile.

Glory smiled in turn.

Who has not seen two wolves grin at each other?

"The boss wants you, chief," said Glory. "Ain't you goin' to wait for him?"

"Can't do it. Tell Bud that I'll be back." He looked around rather guiltily. The big man was nowhere in sight. And then he turned abruptly upon Glory: "Did he send you to stop me just now?"

"Nope. But I seen that he was comin' back and would want you ag'in."

It was all said smoothly enough, but when Carney asked his direct question the eyes of the bouncer had flicked away for the briefest of spaces, a glance as swift as the flash of a cat's paw when it makes play with the lightning movements of a mouse.

Yet it told something to Lew Carney. It told him a thing so incredible that for an instant he was stunned by it. He, Lew Carney, battler extraordinary, fighter by preference, trouble seeker by nature, gunman by instinct, boxer by training, bull terrier by grace of the thing that went boiling through his veins, he, Lew Carney, was stopped at the door of this place by a bouncer acting under the order of fat Bud Lockhart.

It shocked Carney; it robbed him of strength and made him an infant. "Don't Bud want me to go?" he asked.

"Nope. Between you and me, I don't think he does."

"Oh," said Carney softly. "Wouldn't you let me go?"

"You got me right," said Glory.

Carney dropped his head back so that he could only look at Glory by glancing far down, with only the rim of his eyes. He began to laugh gently and without a sound.

At length he straightened his head. All he said was: "Oh, is that what it means?" Glory went white about the mouth, and his eyes seemed to sink in under his brows. He was a brave man, as all the world knew; he was a strong man, as Lew Carney perfectly understood. But he had not the exquisite nicety of touch; he lacked the lightning precision of the windy-haired youth who now stood with a devil in either eye. All of these things each of them knew; and each knew that the other understood. Glory was quite willing to take up an insult and die in the fight; but he would infinitely prefer that Lew Carney should withdraw without another syllable. And as for Carney, he balanced the chances; he rolled the temptation under his tongue with the delight of a connoisseur, and then turned on his heel and walked out.

It had all passed within a breathing space; yet the space of five seconds had seen a little drama begin, reach a climax of life and death, and end, all without sound, all without gesture of violence, so that a man rolling a cigarette nearby never knew that he had stood within a yard of a gun play.

The door swung behind Lew Carney and he stepped into the street and confronted the man with the close-cropped brown mustache! All at once he felt some power beyond him had taken him by the shoulder and made him start up from the chair where he had sat to await the coming of Bud Lockhart, had forced him through the door past Glory Patrick, and had thrust him out into the daylight of the street and into the presence of this man.

It was no guess work. The moment he saw the fellow the film of indecision was whipped away, and he distinctly remembered how this man had heard the tale of the ghost wagon begun and had turned with a shadow on his face and gone through the crowd. It might mean nothing; but a small whisper in the heart of Lew Carney told him that it meant everything.

He had not met the eye of the other. The man stood at the heads of two horses, before a store across the street, and his glance was toward the door of the shop; the source of the expectancy soon appeared. She was a dark girl of the mountain desert, but with a fine high color that showed through the tan; so much Lew Carney could see, and though the broad brim of her sombrero obscured the upper part of her face, there was something about her that fitted into the mind of Carney. Who has not thought of music and heard the same tune sung in the distance? So it was with Carney. It was as though he had met her before.

In the meantime she had gone straight to one of the horses, and he of the brown mustache went to hold her stirrup and give her a hand. The moment they stood side by side, Lew felt that they belonged together. There was about them both the same cool air of self-possession, the same atmosphere of good breeding. The old clothes and the ragged felt hat of the man could not cover his distinction of manner. He did not belong in such an outfit. His personality broke through it with a suggestion of far other attire. He should have been in cool whites, Carney felt, and the cigarette between his fingers should have been "tailor-made" instead of brown paper. In fact, just as the girl had fitted into Carney's own mind, so now the man stepping up to her drew her into a second and more perfect setting. And it cost the gambler a pang, an exquisite small pain that kept close to his heart.

Another moment and the pain was gone; another moment and the blood went tingling through the veins of Lew Carney. For the girl had refused the proffered assistance of her companion and she had done it in an unmistakable manner. Another woman in another time might have done twice as much without telling a thing to the eyes of Lew Carney, but now he was watching with a sort of second sight, and he saw her wave away the hand of the other and swing lightly, unaided, into the saddle.

It was a small thing but it had been done with a little shiver of distaste, and now she sat in her saddle looking straight before her, smiling. Once more Carney read her mind, and he knew that it was a forced smile, and that she feared the man who was now climbing into his own place.

A MOMENT later they were trotting down the street side by side, and the pain darted home to Lew Carney again. A hundred yards more and she would jog around the corner and out of his life forever; she would pass on, and beside her the man who was connected with the ghost wagon and the dead body in Silver Cañon. Yet how small were his clues! He had frowned at a story which made other men laugh; and a girl had shrugged her shoulders very faintly, refusing the assistance to her saddle.

Small things to be sure, but Carney, with his heart on fire, made them everything. To his excited imagination it seemed certain that this brown-faced girl with the big, bright eyes, was riding out of his life side by side with a murderer. She must be stopped. Fifty yards, ten seconds more, and she would be gone beyond recall.

He glanced wildly around him. His own horse was stabled. It would take priceless minutes to put him on the road. And now the inertness of the bystanders struck him in the face. Could they not see? Did not the patent facts shout at them? A man sat on the edge of the plank sidewalk and walled up his eyes, while he played a wailing mouth organ. A youth in his fourteenth year passed the man, sitting sidewise in his saddle, rolling his cigarette, and sublimely conscious that all eyes were upon him.

A thought came to Lew. He started to the horse of the boy and grabbed his arm. "See 'em?" he demanded.

"See what?" said the boy with undue leisure.

"See that gent and the girl turning the corner?"

"What about 'em?"

"Do me a favor, partner." The word thawed the childish pride of the boy. "Ride after him and tell him that Bud Lockhart wants him in a deuce of a hurry."

For what man was there near Cayuse who would not answer a summons from Lockhart? The boy was nodding. He swung his leg over the pommel of the saddle and, before it struck into place in the stirrup, he had shot his horse into a full gallop, the brim of his hat standing straight up.

Carney glanced after him with a faint smile; then he started in pursuit, walking slowly, close to the buildings, mixing in with the crowd to keep from view. What he would say to the girl when he met her, he had not the slightest idea; but see her alone, he must and would, if this simple ruse worked.

And it worked. Presently he saw the man of the brown mustache riding slowly back down the street, talking earnestly to the boy. In the midst of that earnest talk, he checked his horse and straightened in the saddle. Then he sent his mount into a headlong gallop. Carney waited to see no more but, increasing his pace, he presently turned the corner and saw the girl with her horse reined to one side of the street.

She had forgotten her smile and was looking wistfully straight before her; behind her eyes there was some sad picture and Carney would have given the remnants of his small hopes of salvation to see that picture and talk with her about it. He went straight up to her, pushed by the fear that the man of the brown mustache might ride upon them at any moment, and when he had come straight under her horse, she suddenly became aware of him.

It was to Lew Carney like the flash of a gun. Her glance dropped upon him. A moment passed during which speech was frozen on his tongue and thought stopped in his brain. Then he saw a faint smile twitch at the corners of her lips as the color deepened in her cheeks. He became aware that he was standing with his hat gripped and crushed in both hands and his eyes staring fixedly up to her, like any worshipping boy. He gritted his teeth in the knowledge that he was playing the fool, and then he heard her voice, speaking gently. Apparently his look had embarrassed her, but she was not altogether displeased or offended by it.

"You wish to speak to me?" she was saying.

"I don't know your name," said Carney slowly, and as he spoke he realized more fully how insane this whole meeting was, how little he had to say. "But I've something to say to you."

He was used to girls who were full of tricky ways, and now her steady glance, her even voice, shook him more than any play of smiles and coyness.

"My name is Mary Hamilton. What is it you have to say?"

"I can't say it in this street; if you'll go..."

But her eyes had widened. She was looking at him with more than interest; it was fear. "Why?" she asked.

"Because I want to talk to you for two minutes, and your friend will be back in less time than that."

"Do you know?"

The excitement had grown on her with a rush, and one gauntleted hand was at her breast.

"I sent for him," confessed Carney. "It was a bluff so I could see you alone."

Momentarily her glance dwelt on him, reading his lean face in an agony of anxiety; then it flashed up and down the street, and he knew that she would go with him.

"Down here and just around the corner," he said. "Will you? Yes?"

"Follow me," commanded the girl and sent her horse at a trot out of the street and down the byway. He hurried after her, and as he stepped away he saw the man with the brown mustache thundering down the street. But there were nine chances out of ten that he would ride straight on to find the girl and never think of turning down this alley. But there was something guilty about that speed, and when Lew stood before the girl again he felt more confidence in the vague things he had to say. All the color was gone from her face now; she was twisting at the heavy gauntlets.

"What do you know?" she asked, and always her eyes went everywhere about them in fear of some detecting glance.

"I think," said Lew, "that I know a few things that would interest you."

"Yes?"

"In the first place you're afraid of the gent with the brown mustache."

All at once he found her expression grown hard.

"He sent you here to try me," she said. "Jack Doyle sent you to me!"

What a wealth of scorn was in her voice! It made the cheeks of Carney burn.

"He's the one that's with you?"

"Don't you know it?"

"I'm some glad to have his name," said Lew. Suddenly he decided to make his cast at once. "My story you may want to know has to do with a wagon pulled by eight men, with two horses and..."

But a faint cry stopped him. She had swung from the saddle with the speed of a man and now she caught at his hands.

"If you know, why don't you save us? Why..."

She stopped as quickly as she had begun and pressed a gloved hand over her lips. Above the glove her eyes stared wildly at him.

"What have I said?" she whispered. "Oh, what have I said?"

"You've said enough to start me and something you've got to finish."

She dropped her glove.

"I've said nothing. Absolutely nothing. I..." And unable to finish the sentence, she turned and whipped the reins over the head of her horse, preparatory to mounting.

The gambler pressed in between her and the stirrup.

"Lady," he said quietly, "look me over. Then go back and ask the town about Lew Carney. They'll tell you that I'm a square-shooter. Now say what's wrong. Make it short, because this Jack Doyle is driftin' around lookin' for you."

She winced and drew closer to the horse.

"Say two words," said Lew Carney, the uneasy spark bursting into flame in his eyes and shaking his voice. "Say two words and I'll see that Jack Doyle don't bother you. Lift one finger and I'll fix it so that you ride alone or stay right here."

She shook her head. Fear seemed to have her by the throat, stifling all speech, but the fear was not of Lew Carney.

"Gimme a sign," he pleaded desperately, "and I'll go with you. I'll see you through, so help me God."

And still she shook her head. It was maddening to the man to feel himself at the very gate of the mystery, and then to find that gate locked by the foolish fears of a girl.

"I got a right to know," he said, playing his last card. "Everybody's got a right to know; because they's one dead man mixed up with the ghost wagon, and there may be more!"

She went sick and pale at that, and with the thought that it might be guilt, Lew Carney grew weak at heart. How could he tell? Someone near and dear to her might have fired that coward's shot from behind. Why else this haunted look? More than anything, that mute, white face daunted him. He fell back and gave her freedom to mount by his step. And she at once lifted herself into the saddle.

With her feet in the stirrups fear seemed in a measure to leave her. And she looked with a peculiar wistfulness at Carney.

"Will you take my advice?" she said softly.

"I'll hear it," said Lew.

"Then leave this trail you've started on. It's a blind trail to follow, and a horror at the end of it. But if you should keep on, if you should find it, God bless you!"

And she spurred her horse to a gallop from that standing start.

IT was as though she had smiled on him before she slammed the door in his face. He must not follow the blind trail to the horror; but if he did persist, if he did go to the end of the trail, then let God bless him!

What head or tail was he to make of such a speech? She wanted him to come and yet she trembled at the thought. And at the very time she denied him her secret, she pleaded bitterly with her eyes that he should learn the truth for himself. When he mentioned the ghost wagon, she had flamed into hope. When he spoke of the dead man, she had gone sick with dread. But above all that her words had meant, fragmentary as they were, the tremor of her voice when she last spoke was more eloquent in the ear of Lew Carney than aught else.

Yet, stepping in the dark, he had come a long way out of the first oblivion. He was still fumbling toward the truth blindly, but he knew at least that the ghost wagon had not been an illusion of the senses. How it had vanished into thin air; what strange reason had placed eight men on the chain drawing it; all this remained as wonderful as ever. But now it had become a fact, not a dream. His first impulse, naturally enough, was to go straight to Lockhart and triumphantly confirm his story.

But two good reasons kept him from such a step. In the first place there was now a new interest equaled with his first desire to learn the truth of the ghost wagon, and the new interest was Mary Hamilton. Until he knew or even guessed how far she was implicated, he could not take the world into his confidence. And beyond this important fact there was really nothing to tell the world except the exclamation of the girl, and the frown of Jack Doyle.

These things he thought over as he hurried toward the stables behind Bud Lockhart's saloon. For on one point he was clear: no matter how blind might be the trail of the ghost wagon, the trail of the girl and her escort should be legible enough to his trained eyes, and he intended to follow that trail to its end, no matter where the lead might take him.

Coming to the stables he had a touch of guilty conscience in the thought that Bud Lockhart must be still waiting for him in the gaming rooms; for no doubt Glory had told the boss that Lew Carney had stepped out for only a moment and would soon return. But there was no sign of Bud in the rear of the saloon, and Lew saddled the gelding in haste and swung into place. He touched the mustang in the flank with his spur and leaned forward in the saddle to meet the lunge of the cow pony's start, but instead of the usual cat-footed spring, he was answered by a hobbling trot.

For a moment he sat the saddle, stunned. Lameness was not in the vocabulary of the gelding, but Lew drew him to a halt and, dismounting, examined the left front hoof. There was no stone lodged in it. Deciding that the lameness must be a passing stiffness of some muscle, Lew leaped into the saddle again and spurred the mustang cruelly forward. The answering and familiar spring was still lacking. The horse struck out with a lunge, but on striking his left foreleg crumpled a little, and he staggered slightly. Lew Carney shot to the ground again. If the trouble was not in the hoof, it must be in the leg. He thumped and kneaded the strong muscles of the upper leg and dug his thumb into the shoulder of the gelding, but there was never a flinch.

He stood back despairing and looked over his mount. Never before had the dusty roan failed him, and to leave him to take another horse was like leaving his tried gun for a new revolver. Besides, it would mean a loss of time, and moments counted heavily, now that the afternoon was waning to the time of yellow light, with evening scarcely an hour a way. Unless the two took the way of Silver Cañon—and that was hardly likely—they would be out of sight among the hills if he did not follow immediately.

Looking mournfully over that offending foreleg he noticed a line of hair fanning out just above the knee, as if the horse had rubbed against the stall and pressed on the sharp edge of a plank. He smoothed this ridge away thoughtlessly and then looked wistfully down the street. The lazy life of the town had not changed. Men were going carelessly about their ways, yet there were good men and true passing him continually. Charlie Rogers went by him, Gus Ruel, Sam Tern, a dozen other known men who would have followed him to the moon and back at a word. But what word could he give them? A hundred men would scour the hills at his bidding, yet what reason could he suggest? All that wealth of man power was his if he only had the open sesame which would unlock the least fragment of the secret of the ghost wagon. No, he must play this hand alone.

He looked back with a groan to the lame leg of the horse and again he saw the little ridge of stubborn hair. It was a small thing but he was in a mood when the smallest things are irritating. With an oath he leaned over and smoothed down the hair with a strong pressure of his finger tips, and at once, through the hair, he felt a tiny ridge as hard as bone, but above the bone. Lew Carney set his teeth and dropped to his knees. It was as he thought. A tiny thread of silk had been twisted around the leg of his horse, and drawn taut, and that small pressure, exerted at the right place over the tendons, was laming the gelding. One touch of his jack-knife, and the thread flew apart while there was a snort of relief from the roan. And Lew Carney, lingering only long enough to cast one black look behind him, sprang into the saddle for the third time, and now the gelding went out into his long, rocking lope.

The gambler felt the pace settle to the usual stride but he was not satisfied. What if Doyle had given his horses the rein as soon as he found the girl? What if he had made it a point to get out of Cayuse at full speed? In that case he would be even now deep in the bosom of the hills. And many things assured him that the stranger was forewarned. He must have been given at least a hint by the same agency which had lamed the roan. More than this, if someone knew that Lew Carney was about to take up this trail, and had already taken such a shameful step as this to prevent it, he would go still further. He might send a warning ahead; he might plant an ambush to trap the pursuer.

There is no position so dangerous as the place of the hunter who is being hunted and, at the thought of what might lie ahead of him, Lew Carney drew the horse back to a dogtrot. Even if the odds were on his side, it might be risky work, but he had reason to believe that there were eight men against him, eight men burdened with one crime already, and therefore ready and willing to commit another to cover their traces.

The thought had come to Lew Carney as he broke out of Cayuse and headed west and south, but while the thoughts drifted through his mind, and all those nameless pictures which come to a man in danger, his eye picked up the trail of two horses which had moved side by side. And the trail indicated that both horses were running at close to top speed. For the footprints were about equally spaced, with long gaps to mark the leaps. The trail led, as he had feared, into the broken hills south of Silver Cañon where danger might lie in wait to leap out at him from any of twenty places in every mile he rode.

But Lew Carney at any time was not a man to reckon chances too closely; and Lew Carney, with a trail to lead him on, was close to the primitive hunting animal. He sent the roan gelding back into the lope, and in a moment more the ragged hills were shoving past him, and he was fairly committed to the trail.

It was a different man who rode now. With his hat drawn low to keep the slant sunlight from dazzling him, his glance swept the trail before him and the hills on every side. Men have been known to play a dozen games of chess blindfolded; Lew Carney's problems were even more manifold. For every half mile passed him through a dozen places where men might lie concealed to watch him or to harm him, and each place had to be studied, and all its possibilities reckoned with. He loosened his rifle and saw that it drew easily from the long holster. He tried his revolver and found it in readiness. Now and again he swung sharply in the saddle, and his glance took in half the horizon behind him, for in such a sudden turn a man can often take a pursuer by surprise. But the great danger indubitably lay ahead of him, and here he fixed his attention.

The western light was more and more yellow now, and before long the trail would be dim with sunset, and then obscured by the evening. When that time came, he must fix a landmark ahead of him, and then strike straight on through the night, trusting that Doyle had cast his course in a straight line. Unless by dint of hard riding he should come upon the two before dark. But this he doubted. Riding at full speed, Doyle and the girl had opened up a gap of miles before Lew was even started. Moreover, for all his leathery qualities of endurance, the roan was not fast on his feet over a comparatively short distance. It needed a two days' journey to bring out his fine points.

Lew preferred to keep to a steady gait well within the powers of the roan, and trust to bulldog persistence to bring him up with the quarry. He kept on with the hills moving by him like waves chopped by a storm wind. When the sunset reds were dying out, and the gloom of early evening beginning to pool in blues and purples along the gulches, he caught the first sign of life near him. It was a glint of silver far to his left, and it moved.