RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library.

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

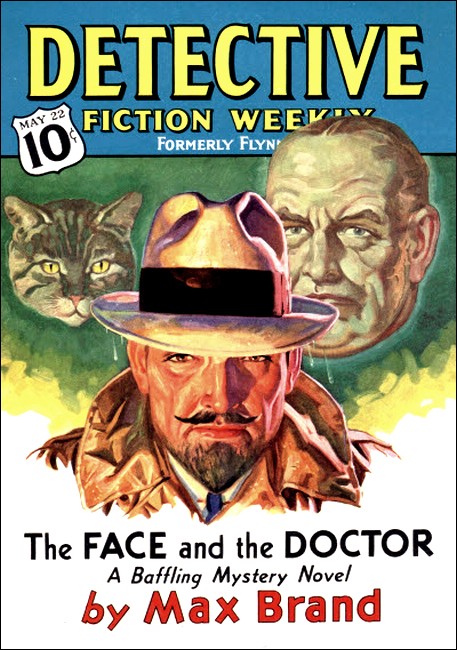

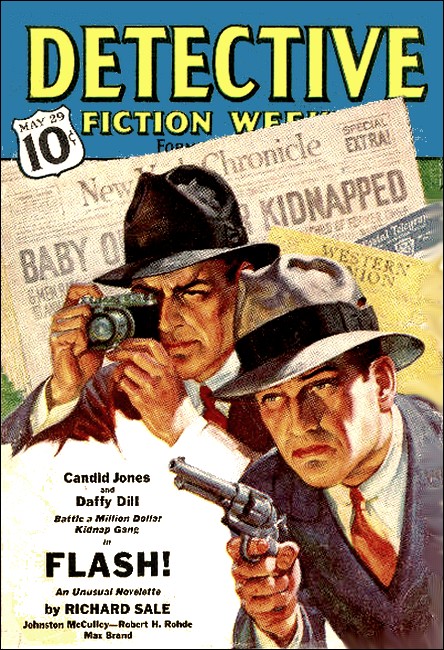

Detective Fiction Weekly, 22 May 1937, with first part of "The Face and the Doctor"

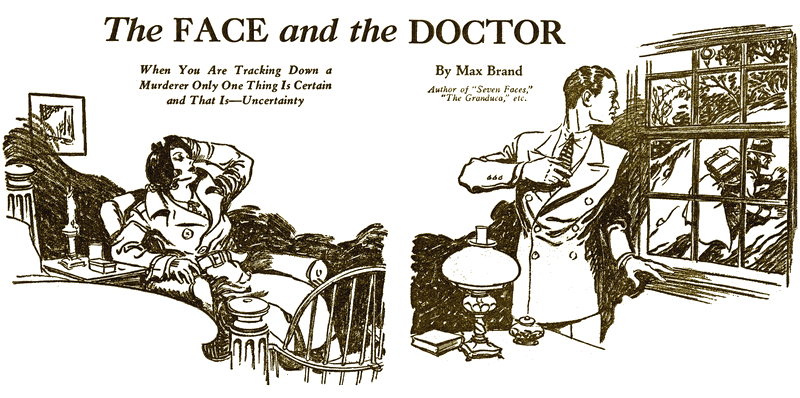

When you are tracking down a murderer only one thing is certain.

At last Muir was looking at the man he was hunting.

WHEN Muir came up to the bar, a Third Avenue elevated train was going by like thunder in a tin heaven and he had to pitch his voice as though he were talking into a high wind in order to ask for a Scotch-and-soda, but by the time he could wrap his long fingers around the glass there was sufficient quiet for him to ask: "Has Everett Franklin been here?"

"Dunno the name," said the bartender.

"Middle-sized, a good pair of shoulders, and as handsome as Hollywood," said Muir. "Looks five years younger than I."

The bartender scanned again the huge, scholarly forehead of Muir and the face half-ugly with pain that was not of the body. He looked forty, though in the morning of the day no doubt he seemed five years younger.

"It's the reporter that you're askin' about," said the bartender. "He's been and gone."

"When?" asked Muir.

"Fifteen, twenty minutes, maybe."

Muir glanced at the clock on the wall and it was, in fact, a quarter past eleven. Other questions rose in his eyes, but he kept them silent and drew the letter from his pocket again. He read it very slowly, deliberately.

Dear Pete,

You remember when we were riding up-town in the taxi the other day, and I pointed to a house and said I was going to raise a scandal out of that place that would put a bad smell all through New York? Well, tonight is the night for me to do a little looking into the business, and it may be a job that will need your pick-lock, your flashlight, and even that big automatic you like to harness under your left arm.

The fact is that you haven't had much fun since you were the boy aviator in '18, playing tag with the enemy over the Western Front, but tonight I may be able to show you enough action to quiet your nerves, for a week or so, and you'll be able to sleep every night through instead of going the rounds like a silly ass and lapping up all the liquor in New York.

I know you're only four days back from Central America and you may have meant it when you said that you wanted to rest a bit, but if I know the old Peter Angus Muir, he'll be on the job with me tonight.

When I say scandal, I don't mean any dirty man- woman business because I know that's not up your street. I mean another kind of dynamite that may blow New York wide apart. Till eleven, I'll be at O'Doyle's Saloon, on Third Avenue, near Fifty- ninth.

Adieu to the greatest detective outside of books from the greatest reporter that ever covered crime. And I mean it!

B. F.

Muir, refolding the letter, drank half the scotch-and-soda

slowly, without taking the glass from his lips. More than ever he

could curse, now, that restless habit which kept him roaming the

city and which on this night had caused him to miss the telephone

call of Franklin at his apartment, for he felt that some great

venture lay ahead, and that he might be left hopelessly in the

rearward of the event.

He lighted a cigarette and looked into the smoke with the eyes of a crystal-gazer, trying to step back to the hour when he had ridden up-town with Franklin four days before. He could remember first, and most clearly, the grinning face of that malevolent reporter as he had hooked his thumb over his shoulder and said: "One of those houses right there on the corner—I'm going to raise a worse smoke than murder, I think, out of it. The police are going to hate my heart all over again."

It had been on the East Side, somewhere. Not Fifth, because there had been houses on each side of the street; not Park because the avenue had not been so wide. Not Third because there was no double file of ugly pillars for the elevated. It was Madison or Lexington, then.

MUIR paid for his drink and took a taxi across to Lexington

and then up-town, driving slowly. Instead of peering earnestly at

every corner, he relaxed in the left side of the seat as he had

done when he was with Franklin and kept his eyes forward as in

consideration, letting the street-corners drift casually through

the widest angle of his vision. They were north of Seventy-second

Street when a ghostly finger tapped at his forehead.

He got out at the next corner, paid the taxi, and went back. On the northern side of the block below, three houses of identical aspect, long and narrow as the faces of three fools, rose cheek to cheek. Now that he confronted them, all recollection of having seen them before departed from him, but he would not deny the authority of that electric touch which he had felt as the taxi passed this corner.

He went to the south west street corner and viewed the houses aslant, as he must have done when Franklin called his attention to them. Still nothing returned from his memory, so he came closer to examine them at first hand. The one nearest Lexington was alight from the first floor to the sixth and highest story; music. Young voices crowding together in laughter, told him of the party which was going forward.

It did not have the look of a place where Franklin might have need of a pick-lock, a flashlight, and a gun. The adjoining house carried a "For Rent" sign, so he went past it to the third place where the front windows were equally filled by empty blackness. His confidence in the trail he was following had diminished almost to nothing, but he wandered up onto the porch of the house and took from his inner coat an electric torch hardly larger than a fountain pen. It cast a thin, sharp ray with which he ran rapid pencil strokes of light about the porch.

He saw the doorplate of "Dr. David J. Russo;" he saw the folds of the thick satin drape which hung inside the door-glass; and on the cement floor of the porch lay a cigarette butt that had been stepped on by a foot which afterward twisted over it and left paper and tobacco as an ugly spot, well-ground into the cement. Few men put out their cigarette butts with such care, but Everett Franklin had that ugly habit.

Muir turned from the house and walked straight across the street, where he lounged in the thick shadow between two houses. Franklin had been at the third house before him, and not more than twenty-five minutes ago.

He had come, according to his letter, prepared to go to great lengths to enter the building, and therefore the chances were large that he was in the house at the present moment; for every successful reporter has to have a good deal of the bulldog about him and Franklin had the patience of a hunting beast.

A paved footway ran down the left side of the house but not a glimmer of light came from the windows on that side. If Franklin was inside, he was at work with one of those flashlights of which he had spoken.

If that were the case, it would probably be foolish or even a little dangerous to try to enter the place while the investigation was going on. There came to the eye of Muir a picture of shadowy hands running through the papers of a desk, while an electric torch set them flashing.

A GIRL walked down the farther side of the street and the eye

of Muir commenced to follow her because her steps were not

checked and stilted by high heels; she moved with the rhythmic

lightness of an athletic boy, with a good, free swing. When she

reached the house Muir was watching, she turned and ran up the

steps, and for some reason he looked up at the bright December

stars and laughed, silently.

He could even hear the click of the key in the lock, he thought, as he strained his ears; then the door opened and she went inside. The door glass was illumined only a moment later; then the shades of the double window to the side glowed faintly.

Muir forced himself to wait two minutes; then he crossed the street and rang the house-bell.

He heard a step come into the hall. The door was pulled open by the brisk hand of someone in a hurry, and he saw the girl before him with the fox-fur loosened about her throat. The cold of the winter night was rosy in her face and twinkling in her eyes. She had the glow and the air, if not the exact features, of beauty.

Muir took off his hat. "Dr. Russo in, by any chance?" he asked.

The late hour made her look carefully at him.

"He isn't in," she said, "and I'm afraid that he won't be in tomorrow, either. I'm sorry."

Muir smiled on her a little.

"After all, this is not an office hour, is it?" he said.

"Hardly," she answered, and then, looking farther into him: "Are you in pain? Is it something acute?"

"Rather," nodded Muir.

She glanced instinctively down at a wrist-watch. Then: "Will you come in? I can make a note and perhaps the doctor can get in touch with you later?"

"Thank you," said Muir, and stepped inside.

Crossing the hall, he photographed on the sensitive plate of his memory the details of the hat-rack at the side, the two straight-backed chairs which flanked the mirror farther down the hall, and the stairs climbing into shadow. The girl showed him into an office with a small mahogany desk set at an angle in a corner, three framed diplomas on the wall, two shelves of books, a coal fireplace, a rather good Persian rug with a pine-tree pattern on the floor, and above the mantelpiece the large photograph of a narrow-bearded, professorial face, a sensitive face with a great slope of forehead and penetrating eyes; the moustaches and beard left the expression of the mouth somewhat indecipherable. But what Muir used his eyes on chiefly were the ranges of books. He picked the word "diet" out of half a dozen titles.

The girl was sitting behind the desk, now, pulling the glove from her right hand, then pulling a note-book in front of her.

"Your name, please?" she asked.

He did not hesitate. The name Peter Angus Muir was not known in many quarters. In 1918, when he came back from the front, the newspapers had made a good deal of the seventeen year old boy who perjured his way into the air force and shot down eight planes, but that was nearly two decades ago and people had forgotten the Great War.

He had another reputation which was almost entirely confined to a small scope in the New York police department for certain bits of voluntary detective work which he had done and it was this reputation which he was trying to keep in shadow as he gave the name: "Oliver Croft."

"Your address, Mr. Croft?"

"The Centenary Club," he answered, for the club knew what to do with communications addressed to "Oliver Croft."

"And the symptoms?" she asked.

He considered his physical condition and began to speak the truth.

"For the last day or two," he said, "I've had a subnormal temperature, a heaviness in the knees, disinclination to stir about, and something rather misty about the old brain. Living in something of a fog—that sounds a bit on the liverish side, doesn't it?"

"A bit," she answered, gravely.

He saw that he would have to add something more to justify this midnight call at a doctor's office.

"And in addition, griping occasional pains in the stomach," said Muir.

She made the notations swiftly. A huge tiger cat came into the room on silent feet, turned its yellow eyes on Muir, and then leaped onto the desk. It sat down facing the girl, with its long tail wrapped around its fore-paws. As she finished writing, she put out her hand and scratched the cat across the forehead. The sound of its purring began like a distant buzz-saw.

"Much drinking?" she asked.

"Much," said he.

"Very late hours?"

"Very," said Muir.

She read his face from right to left and then from left to right. She did not smile.

"May I ask who recommended the doctor to you?" she asked.

"A fellow down in Nicaragua, just before I flew back. Craig, or Krank, or some such name, I think."

"May I ask a rude question?"

She had green eyes, full of penetrating thought.

"Fire away," said Muir.

"You don't look well," she remarked, "but did you come here partly because you're in pain and partly because you wanted something to do?"

"Partly," he admitted. "Twelve o'clock hasn't come, and that's not so very late for a doctor to be awake in his home."

"But he doesn't live here," she answered.

"Doesn't he? The fact is that I was up in this part of the city and suddenly remembered his name and that my in-sides seemed to need some tinkering. Did you ever want to kill some time in the middle of the night?"

"Of course," she said, rising.

"From the moment the sun goes down, in fact?" asked Muir. "Will you have a cigarette?"

She hesitated over the offer, and then smiled as she took the cigarette. Muir lighted their smokes.

"Will you sit down a moment?" she asked.

"I'm only going to take a bit of your time, and I'd as soon take it standing," he answered. "I know you're about to leave."

"How do you know that?" she asked, her brows lifting slightly.

"You have a forward look in your eyes," said Muir, "that tells me you have some place to go. You people with places to go—you have all the luck."

"Do you always know what people are going to do?"

"They don't have to look at their watches for me to know that they're going to leave me."

"No, people don't leave you," she decided.

"Ah, but they do. Can't put a value on a thing you can have any time you want it. Oliver Croft is a glut on the market."

She surveyed him again with a faintly whimsical smile.

"No, not a glut on the market," she said. "I don't think he puts himself on the market at all."

"Don't you?" asked Muir.

"No," she decided more firmly. "He keeps away from his friends because humanity disgusts him a little; and then all at once the corners of the room fill up with shadows and he has to go somewhere, anywhere, quickly. Isn't that it?"

"Who the devil are you?" asked Muir, abruptly. "If you don't mind me asking?"

"I'm Katherine Edwards," she said. "Trained nurse?"

"Yes. How do you guess that? Because I'm here in a doctor's office?"

"Not at all. I guess by the professional way you have of picking up a man and sifting him through your fingers. Do you ever have trouble wasting time? But of course not."

"Why not?" she asked.

"If you ever do, ring the Centenary Club and ask for poor Oliver Croft. But I know how they're standing in line. A pretty girl in the upper brackets. Whenever I see one of you, there's a procession of ghosts filing away behind your shoulders; all the poor devils who have looked at you and wished that your smiling were not such a confounded generalization. Do you mind me saying that?"

"You know I don't mind it," she answered. "It's the manly way of doing the thing, I suppose."

"What thing?" asked Muir.

"Paying a compliment, and wrapping it up in a little bitterness."

"I'd better go," said Muir.

"No, I have about two minutes more," she answered.

"I don't want the minutes," said Muir. "You've seen too much already. Will you tell the doctor about me?" he added when he was at the door.

"Of course," said she.

"But you won't tell him everything, will you?" he asked.

She laughed, and he went out, buttoning his overcoat against the cold.

He walked with a brisk step down the pavement past the three houses, turned, and came back with a silent footfall into the side-path that ran past the doctor's place. Inside he could hear the voice of the girl, for one of the office windows was slightly ajar. She was saying: "Is this Greenwood 510?... Mr. Baldwin told me to telephone and that you'd let me know how to get out to your place... yes, Mr. Philip Baldwin... how shall I know the car?... I'm five feet seven, have blonde hair, and will be wearing a fox- fur and a gray overcoat. I'll carry a small pigskin suitcase... I'll repeat it. A blue convertible. I simply ask if the driver can take me to Mr. Baldwin? Thank you. Good-by."

The receiver clicked. A moment later the lights snapped off, then the front door closed heavily and quick footfalls went down the street toward Lexington Avenue. When the sound of them died out, Muir went back to the front porch of the house with a little steel pick-lock in his fingers.

WHEN at last the door was open and he made the first quick

step into the dark of the hall, he tripped over something soft

and movable and had to bring his left foot down with a stamp to

keep from falling. The ray from his torchlight caught the tiger

cat which was racing towards the stairs with its body twisting to

the side because the hind-legs went too fast for the front

feet.

Muir switched off the light and swung the door softly and slowly shut, with his head bowed to listen. For tripping over the cat might have warned any other people in the house that a stranger had entered.

As he paused, he could hear the soft, rushing noises of the city. The groan of iron on iron no longer troubles the ear of New York, now that street cars are being banished from the town and the predominant night-sounds are the swishings of well-treaded tires and the whine of accelerating motors. Muir pushed from his mind these outer noises and tried to leave his ears purged of them to listen to smaller and more intimate sounds inside the house, like the fall and small echo of a footstep, or a creaking of floorboards, no matter how soft, or the dim murmur of a voice, or the dull thump of a shutting door.

In fact, he heard nothing at all, but from that moment forward he felt like a man besieged by danger and muffled every move that he made. As he moved from room to room, searching, he kept the thin sword-point of the torchlight pointing again and again at the doors which might open noiselessly upon him. He wished more than once for a light sufficiently strong to flood each chamber, no matter how dimly, but he knew that such a light would be strong enough to illumine windows and perhaps flash telltale warnings to eyes outside the building.

He began his work in the office, running rapidly through the drawers of the desk, where he found two items that caused him pause. One was a case of shimmering surgical instruments; another was a newspaper item which described the return to practice and New York of Dr. David J. Russo, the eminent young dietitian who for the last three years had been at work in the Orient.

Dr. Russo was quoted as saying: "Just as in medicine there are few specifics, so in diet there are few foods which are either banned or indicated, except in the case of definite disease. The dietitian walks in a general darkness; we lack a definite science."

The room behind the office was a small laboratory, fitted with the utmost compactness and neat arrangement, with Bunsen burners and other standard equipment, and long ranges of labeled bottles in glass cupboards.

He gave hardly a flash of the light to the multiple, glimmering face of science, but went on into a little room behind the laboratory. It might have been used for a bedroom because of the small cot in it.

The flashlight picked up on the point of its bright pencil the ashes of a pack of miniature cards which lay in a corner of a smoking-tray. In a corner of the room was the top part of a tiny pagoda, made of a bright red composition; the sort of toy that one can pick up in a five-and-ten-cent store.

In the bathroom adjoining there was nothing of note except a mirror which had been struck a heavy blow in the center, so that the glass was broken away around a circular aperture in the middle, while a thousand fracture-lines ran out to the square frame.

A door on the right opened on what seemed to be a waiting- room, to judge by the comfortable chairs and the file of magazines which covered a center table. On the wall were three or four big photographs of the upper Himalayas. He recognized the tremendous outlines of the more famous peaks.

The tiger cat was there before him. He expected it to scamper away when he appeared, but instead, it did not even wince from the passing ray of the torch. He put the bright spot on it again, curiously, and saw that the cat was stalking, its belly almost touching the floor as it stole forward and its tail crooking at odd angles from side to side. But the direction of that hunting trail led only toward the blank face of the wall!

MUIR sat on his heels to watch. Even the continued brightness

of the spot light on it did not disturb the striped cat, for it

seemed to be drawn on by a horrible fascination, like a bird

towards a snake's eyes. The repugnance it felt caused the hair to

stand on its back, and it put down each foot gingerly, with its

body sloping back, ready to whirl and flee at any instant, and

yet it continued to stalk until it had come to the very edge of

the wall. There it extended a fore-paw, and ran its unsheathed,

upturned claws along the bottom of the wall; then it whirled and

raced from the room.

Even the blood of Muir was chilled by that strange pantomime. A moment later, running the meager knife-edge of the light across the wall, he discovered something that gave a little more earthly sense to the actions of the cat, for he found the almost imperceptible outline of a door, set flush in the wall to keep from disturbing the pattern of the landscape paper. Now that his attention was drawn to it, he had no difficulty in finding the little drop-handle with which a latch turned, and he opened the door upon a small closet. On the floor inside was huddled the body of Everett Franklin with his dead eyes looking into the face of his friend and his upturned face cross-hatched with lines of blood.

The faintest noise of sighing air behind him made Muir whip around. His spotlight found a door closing at the side of the room. Natural fear stopped him for an instant like a fist in the face; then he raced for the door with a long automatic in his right hand and the flashlight in the other.

As he turned the latch and flung the door open, he slipped to the side, offering only his head and shoulders as he flashed the light into the interior. It was a mere vestibule for a flight of servants' stairs that ran at a sharp angle up the back of the house and above him he heard not the pounding, but the whisper and faintly creaking pressure of footfalls fleeing up the steps.

He followed eagerly, with the hunting animal alive and alert in him, and pictures of dead Everett Franklin flicking through his mind; bright, swift glimpses of Franklin rousing the dangerous streets of Singapore; Franklin with heels and ice-pick dug in on the edge of a Tibetan crevasse; Franklin on a rollicking Western mustang. Grief had no chance to overtake Muir as he swung around the corners of the stairway to the floor above, and the floor above that behind the stealthy sounds of flight. There he ran down a narrow hallway toward an open door and plunged through it to the room beyond.

The flashlight showed him a white-painted iron bed, a cheap bit of matting on the floor, a holiday poster on the wall.

The opposite door was locked, and as he came to a pause, listening intently for the noise of the running feet, he heard the door behind him shut, and the turn of the key in the lock. Downstairs ran the fugitive footfall, swiftly fading out of his ken.

Rage and disappointment locked his jaws together. He was groaning softly as he set to work with the pick-lock, but a state of confused passion was not the way to try to read the mind of even the simplest lock. It left him in a cold sweat, but he brushed the storm out of his mind and with half-closed eyes set to his work. There could not have been a more ordinary house- lock, but it was complicated by rust. It might have been only five wretched minutes that he spent on his knees, laboring, but it seemed to Muir a half-hour before he had the door open.

He went down the stairs without haste, and as one who knew that the vital moment was irretrievably gone from him. The closet door, as he had expected, was now closed, but the body of Everett Franklin was no longer inside. There was not even a bloodstain on the floor, which had been carefully washed and was rapidly drying, now, in the warmth of steam heat.

He found light-switches and turned them on through the lower part of the house. Then he telephoned the police.

THE next morning, John Tory, Inspector of Detectives, arrived at eight o'clock at the apartment of Peter Angus Muir and had the door opened for him by a big man with a pair of beautifully groomed moustaches and a great bald dome of a head.

"I want to see Mr. Muir," said the inspector.

"Mr. Muir is not called until eleven o'clock, sir," said the big man.

"I'm an inspector from the police," said Tory, sharply.

"Mr. Muir will be very sorry," said the guardian of the door. "He is not called until eleven in the morning."

The door began to close, slowly, in the face of the man of the law. Suddenly he pointed a finger.

"Why, you're Hawley; you're the valet, aren't you?" he asked.

The edge of the door cut the face and large figure of Hawley in two as he answered: "Yes, sir."

"You've heard Muir speak of me, then. You've probably heard him speak of me? I'm John Tory."

The door instantly swung wide.

"Mr. Muir speaks of you constantly. Come in, sir. I beg your pardon," said Hawley.

The sense of crowded New York left the inspector, the moment the door closed behind him, and he found himself in the spaciousness-of a large reception hall with a hunting scene running across a great green tapestry on the opposite wall. The air had not been parched to lifelessness by steam heat and the room seemed to be warmed entirely by a fire of big logs that burned in a corner fireplace beneath a hood of carved Italian marble.

"Have you had breakfast, sir?" asked Hawley. "And is there anything I can do personally to make you comfortable? The fact is that Mr. Muir is in the country."

"In the country? When did he go to the country?" asked Tory.

"Yesterday evening, sir."

"He was in New York at midnight Hawley. Did you know that?"

"Exactly, sir," said the unblushing Hawley, "but I presume he may be in the country now. He is not at home."

"Is he going the rounds?" asked Tory.

"Sir?" said Hawley.

"I've been around them with him," said Tory, "and I know you've been around after him. In one night I've been from Mulberry Street to Harlem, and across the Triborough and George Washington Bridge, and from a cellar dive to a penthouse in the middle of the sky. I've followed him till my knees sagged; and I've had my brain whirling although I've drunk only one whiskey to his two all evening long. Is he out on a bender like that?"

Hawley took a breath and regarded the inspector with a whimsical eye that seemed to struggle with a desire to speak from the soul.

At last he exclaimed: "Sir, he's always out—except for brief spells in the library and the laboratory. More in the laboratory by far."

"Laboratory?" said Tory.

"Yes, sir."

"Tell me this, Hawley. How can he stow away so much alcohol in that long, scrawny body of his?"

"I can give you an explanation which he once offered to me, sir," said Hawley. "We were in Egypt at the time, in the company of some English residents and the English who live in tropical countries, as you no doubt know, sir, are really very wonderful with their whiskey."

"Champions!" said the inspector, without hesitation.

"However," said Hawley, "on this evening they failed to stay with Mr. Muir. They failed signally, I may say, sir, at about three-thirty in the morning, and Mr. Muir came home at about six in the morning with an Arab horse thief."

"Horse thief?" said the inspector.

"You must be aware, sir, that after midnight Mr. Muir is in the habit of finding very interesting companions."

"True," said Tory.

"The Arab, sir," said Hawley, "showed his international culture by drinking whiskey with Mr. Muir, but at about eight o'clock he fell asleep in his chair. I had not been able to follow the conversation, because it was entirely in Arabic, and now Mr. Muir turned to me and said: 'The rest of the world resists alcohol, Hawley, and because they resist, the alcohol breaks them,' were the words Mr. Muir used, 'but I go to it with my arms open, like a friend, and the infernal stuff passes me by with a mere pat on the head.'"

"Nobody knows him as well as you do," said Tory, "now tell me if nothing but another World War would fill up his time and set him at peace with life again?"

"Nothing else, sir," said Hawley, solemnly. He turned a bit to the side, as though anxious to escape from the subject of the conversation. "As for the laboratory, sir, it would be sure to interest you—and at about nine o'clock Mr. Muir is fairly sure to return."

TORY went willingly into the laboratory. It was a room as big

and as lofty as the entrance hall. There was a large sink, drain-

board and table for experiments at one end of the apartment with

a blacksmith's forge adjoining.

The walls were lined with cupboards which Hawley prepared to open with a bunch of keys but the attention of the inspector fastened upon a large table which was covered and piled deep at the corners with locks of every size, from great padlocks to little devices no larger than a woman's wrist-watch. All the locks on the right half of the table rested upon individual sheets of paper covered with penciled notations.

"What are these for?" asked the inspector.

"A long time ago," said Hawley, "Mr. Muir heard about Houdini in Sing Sing and decided to look into the question of safety devices."

"Houdini in Sing Sing?" queried the inspector.

"I believe it is true," said Hawley, "that Houdini offered himself to be locked with the utmost security in the strongest cell in Sing Sing, with his clothes in another cell, and wagered that he would walk out free and fully dressed within fifteen minutes. As a matter of fact, they loaded him, naked, with complicated chains and irons secured by the most difficult locks they could find. His clothes were placed in another strong cell.

"In five minutes and a half, Houdini walked out of the first cell with the irons gone from him; in eight and a fraction minutes he was fully clothed and ready to leave the prison. This story intrigued Mr. Muir and he has been studying locks, off and on, ever since. Those on the left of the table he has not come to yet. Those on the right he has solved and made notations in short hand and with diagrams on the papers beneath them. Ah, Mr. Muir has returned—with a friend!"

For here a powerful tenor voice, thickened a bit by fatigue and vocal cords loosened by wine, broke into a hearty Neapolitan ballad.

THEY found the two in the entrance hall, Muir already equipped

with a highball and curled into a deep chair while a fat Italian

in a ruff-neck sweater and tattered clothes, teetered back and

forth and sang to the flames in the fireplace, waving a fiasco of

red wine to keep time with his music. His knees began to bend

before he had finished the lyric. Muir watched him curiously, his

own face dead-white, but his eyes as clear as ever.

"Put him to bed in the Quattrocento room, Hawley," said he.

"I beg your pardon, sir? To bed?" said Hawley.

"To bed," said Muir, rising as he saw the inspector.

"In the Quattrocento room?" echoed Hawley, sadly.

"In the Quattrocento room," answered Muir, with patience. "How are you, John?"

"Much better than you," said the inspector, bending back his bulldog neck and peering up into the face of his friend. "You look like the devil, Peter."

The door of the room slammed. The Italian tenor rose dimly from a distant part of the apartment.

"I need a few minutes of sleep," said Muir, "and I'll be as right as rain. Will you have a drink?"

"No. You should have called me last night. You shouldn't have let those foolish fellows of mine walk over you roughshod, that way. They're good men, all of them, but they simply didn't know you. When I told the sergeant that you were the Peter Angus Muir, he turned inside out."

"That must have been an ugly sight," said Muir. "However, there was no great purpose in waking you up in the middle of the night and as for the way they slanged me, why, talk doesn't break the skin. I gave them the clues I had."

"Thank heavens Willett had enough sense to write them down," said Tory, pulling a notebook out of his pocket. "The ashes of a pack of miniature cards; the top tip of a toy pagoda, red in color; a smashed mirror in a bathroom; marks of scrubbing on the floor of a downstairs closet; the picture of the doctor; a clipping that tells he has been in the Orient; and a case of surgical instruments. It doesn't make a great deal of sense to me, just reading the list off. Are you going to do some high- power deduction with this list as a basis, Peter?"

"My dear old fellow, deduction is almost entirely rot," said Muir. "It's in books, not in the facts of detective work, as a rule."

The inspector listened with a shrewd glint of amusement in his eye.

"Do you believe a single word you've just spoken?" he asked.

"Yes, two or three of them," said Muir.

"Did you give the police everything that you can testify?" "Almost."

"Will you give me the rest of it?"

"No, John," said Muir.

"Ah!" exclaimed the inspector.

"Ah... what?" asked Muir.

"Does it mean that you're going on this case yourself?"

"I think it does," said Muir, "if there's room for me."

"Peter, you know what you can always have from me. Every card in the pack that I can deal to you."

"Tell me what you've found out about the doctor," said Muir, "and I'll let it go at that."

WHEN the inspector left, he had given Muir an extended picture of Doctor Russo. The dietitian had been a brilliant student and could have taken his choice of almost any field of medicine when he finished his interneship. He could have been surgeon or diagnostician under the best auspices. He had practiced for some time with the greatest success, but finally went to the Orient to pursue the study of certain obscure diseases of the skin. His return to New York was recent and rather unheralded, because he had been away long enough to be forgotten. He was thirty-seven years old, and he still was missing from his office.

Muir pulled off his shoes and coat and lay flat on his back on a bedroom floor for twenty minutes; he roused and lay a somewhat similar time face down. After that, he bathed, and coming back into his dressing room found Hawley there placing on a table a choice of guns in arm-pit holsters and a selection of small flashlights. For wearing, he had put out a heavy gray tweed and a pair of thick-soled shoes.

"Am I bound in that direction, Hawley?" he asked.

"Nicaragua turned out to be a dull place for you, sir," said the valet, "and I daresay you must find recreation and rest, now."

"Is it rest and recreation to go out with this stuff?" asked the master.

"It is rest for a hunting dog to follow a trail, sir. I beg your pardon," said Hawley.

"Is that it?" sighed Muir. "But isn't a man a fool who baits a trap with his own danger?"

"You're not intending to do that, sir, I trust?" asked Hawley.

"I hope not," said Muir, and dressed gloomily for the street.

HE slept on the train for Greenwood, Westchester County, and

got out at the station before noon. In the middle of the big

street, between parallel white lines ruled aslant, were parked a

score of automobiles besides the machines which nosed the

concrete station platform. What Muir picked out was a blue

convertible with a weather-stained top.

Before he went to it, he looked over the brown winter hills of Greenwood, and the gray trees which rolled like storm-clouds across them. The brightness of the sky could not bring cheer to that landscape, and he had a strange, cold feeling in his heart that the hills were drawing closer to see the last of him. He had to rally himself by the use of his powers of logic, for after all he was not on the actual trail of murder but on what was probably a most innocent by-path.

When he recalled the well-tubbed, outdoor, free-swinging look of Katherine Edwards, his spirits rose again. But he could not banish entirely a slight numbness and mist in the brain that had been growing in him during the last few days, since the airplane brought him back from Central America.

As for the girl, he told himself that he had for her a more intellectual than emotional interest, for he had made romance a stranger in his life. And if he followed her by the most slender clue, he made sure that it was not her beauty that led him, but merely his abiding passion for crime-solution. And she was the only approach to the trail, an almost intangible approach, to be sure.

It was his certainty of her innocence that had kept him from speaking about her to Tory or to the homicide squad the night before, and even now she brought to him a sense of refreshment as profound as long sleep.

He went over to the convertible and found behind the wheel a man in a canvas coat with a turned down collar lined with lamb's wool; his head hung down in sleep and he roused from it gradually, coming back to full consciousness with a rhythmical jerking that got his head erect at last.

He had a pale, thin face and when he spoke he looked straight ahead as though he was accustomed to keeping his eye on the road at all costs.

"You can get me to Mr. Philip Baldwin, can't you?" asked Muir.

"A dollar and a quarter," said the driver.

"That's all right," said Muir, and got into the rear seat.

THE car was a four-year-old model, but the motor was tuned up

to a hair-trigger fineness. It started at a touch, and softened

its whine as the driver ran through the gears to high. He drove

like one to whom an inch is as good as a mile, sliding through a

tangle of cars to gain the open road. The village dropped behind;

and with the gathered speed of the automobile the brown-faced

hills began to flow across the sky.

"You known Mr. Baldwin a long time?' asked the driver.

"Not a great time," said Muir.

"No?" said the driver, and found the remark enough for his digestion during at least a mile of the road.

"Not so many friends as there used to be," said the chauffeur at last.

"Three are enough," ventured Muir, studying the back of the driver's head.

"Yeah. You mean real ones."

"That's it."

"There ain't that many," said the driver. "There ain't three."

"I don't know about that," said Muir.

"I do," said the driver, and pulled in at a gas station with a sudden soft, strong pressure of hydraulic brakes.

"Five gallons," he said to the attendant, and then to Muir, as he got out of the car: "Be a minute."

He disappeared into the station and Muir, turning sidewise on the seat, half-closed his eyes in order to focus all his nerve- power on concentrated listening. In this manner, though dimly, he heard the stream of gasoline from the hose plump into the tank, not with a sharp tinny resonance as into an almost empty receptacle but with a full, dull sound as into a tank already nearly brimming.

When he had satisfied himself about this, he faced front again, only watching from the corner of his eyes as the pale driver came out of the station; but it was not the sort of a face that, could be read easily, needing close study and some familiarity before thoughts would be apparent on that cold surface.

It was reasonably certain that the fellow had telephoned ahead about his passenger who had not known Mr. Baldwin a long time and who said that three real friends were enough.

That trust which Muir had been investing in the clean beauty of Katherine Edwards vanished at once. A thunderhead which was growing out of the west, trailing its obscure shadow over the hills and melting them into the sky, seemed to Muir to represent the darkening of his mind as he approached the end of his journey. Even as his eye watched the coming of the storm, so his spirit felt the approach of the danger. Perhaps he should have, brought Hawley, that steady, brainless hand.

The car swerved up a slope of gravel and stopped in front of an old shingle building. Muir filled his eye with it as he climbed out of the car. Time had taken the building by the roof- tree and shaken it. There were no straight lines remaining. The roof humped in one direction, the porch-roof sagged in another, and the side-walls leaned inward for greater security. For a generation at least no care had been given the old tavern; even the yellow paint on the porch pillars and balustrades was rain- rusted to a dingy brown.

Muir paid his driver.

"You go in there, through the bar," said the man, and let his colorless eyes rest once on Muir's face.

THE bar-room contained, as the law requires of liquor vendors,

a number of tables covered with cloths checkered red and

white—and a scattering of salt and pepper shakers helped

the legal illusion. But something stiff in the wrinkles of the

tablecloths showed how seldom they were disturbed, and the worn

floorboards in front of the bar told where the chief trade

lingered in Stowett's Tavern. Muir paused there and asked for a

beer. A pair of country fellows in complete suits of brown

overalls studied him with a dim interest in the mirror.

"I want to see Mr. Baldwin. Is he in?" asked Muir.

It seemed to him that the bartender's ivory ruler made a sudden jerk as it carved the foam from the top of the glass.

"If he's in, I'll tell him your name," said the bartender.

"Croft," said Muir, "Oliver Croft."

And as he spoke, he remembered the green, clear eyes of Katherine Edwards and her direct manner of speech, like the conversational way of a man. If she had in fact come to a place like this, it was a stain upon the memory of her. The two ideas no more went together than a princess goes in rags and squalor. It was then for the first time that a doubt of her grew up strongly in his mind, for he remembered that crime draws a dirty hand over high and low.

In the meantime he studied the bartender, who was serving another pair of beers to the farm laborers before he left with Muir's message. His knowledge of bars and barmen was long an intimate and somewhere in his past he thought he could recall Jeff's face when the features had not been so engrossed in red flesh. For a long moment he looked inward until the picture of the other place grew clear.

It had been a somewhat shady resort owned by Shannon, the politician, who was still one of the powers behind the thrones of New York. Lightly the mind of Muir linked bartender, Shannon, and this unknown Philip Baldwin together, in a tentative chain.

Jeff being gone, Muir drifted his eyes about the room. A picture of the old thoroughbred, Bendigo, hung on one wall, and a large head of McChesney faced it from the opposite side. Above the big, round-bellied stove was a colored sketch of a coach and four "on the road to Nyack. Mr. Vincent St. John, whip."

The bartender returned. He had a red face solidly supported by great jowls. The hairs on his head were white and few but they made up somewhat by their vigor, standing up almost on end. He had found Mr. Baldwin, he said, and the gentleman would come down to the bar.

The two farmhands left, but came bolting back into the barroom again a moment later, driven by a downpour of rain that made the old tavern shudder from head to foot; and through the broken light of a window a fine rain-dust entered the air of the room. With the natives entered a third fellow, low and squat and heavy- shouldered as a mastiff. In a few years he would have only the soggy weight of a draft horse, but now youth and hard exercise lightened him. He stood silently by the stove, sunning his back in the warmth, and from the peak of his corduroy cap water dripped unheeded down his cheek.

"How are you, Steve?" asked the bartender.

In the mirror, as he sipped his beer, Muir saw the bulldog nod without unlocking his jaws to answer.

The rain had darkened the place thoroughly before a big fellow inches above six feet entered the bar from the interior of the tavern. He had a dished nose and a scar in front of his left ear pulled his features slightly awry, particularly when he talked. He had the bulk of a wrestler above the hips and the taper look of a runner below them. He seemed to appreciate the magnificence of his body and set it off with a double-breasted brown suit that fitted him a shade too snugly.

He wore a small red flower in his buttonhole and his blond hair was given luster by some ointment. He carried a certain delectable fragrance into the room and coming straight up to Muir gave him his hand and a slightly twisting smile. His voice was so soft and the pitch of it so low that only a fine resonance kept his words from obscurity.

He said: "You want to see me, Mr. Croft?"

"I do," said Muir. "Will you have a drink with me?"

"With pleasure," said Philip Baldwin. "A beer, Jeff, if you please... dark day, Mr. Croft, isn't it?... December ought to be white; there's no drama in black mud and brown grass."

HE picked up his glass from the bar, but in the act of raising

it and nodding acknowledgment to Muir, he turned suddenly and set

his back to the edge of the bar almost as though a twinge of

physical pain had disturbed him. Whether it were a thought or

actually a touch of suffering, his face darkened in spite of the

air of courtesy with which he masked it. It seemed to Muir that

the scar must be somewhat new and perhaps that accounted for a

slight stiffness of the face muscles which gave a hint of the

look of a paralytic.

"The driver of the car didn't approve of me," said Muir, with an air of cheerful frankness. "He stopped on the road and telephoned."

"Did he?" asked Philip Baldwin.

"Poor Jim has to think out everything in his own way."

"Only held us up a moment," said Muir, "and after all why have a man unless he's careful, eh?"

"Perhaps," agreed Baldwin, and though he lifted his eyes no higher than the long, thin hands of Muir, the latter had a distinct impression that he was being searched to the soul.

"We might sit over at one of those tables, do you think?" asked Muir.

"Certainly," said Baldwin. "Will you have another beer?"

"No, I'll keep this going for a while," answered Muir.

He led the way toward a corner and heard the voice of Baldwin exclaim behind him, not loudly but with a sharper ring: "What's the matter with that dog, Jeff?"

Muir turned and saw a big German shepherd with one side of its face swollen and the black, ragged mark of a cut across the puff of one jowl.

"That Schneider dog, that Airedale of theirs," said Jeff. "He got a tooth into Max yesterday. That's all. Max made him run, though, and howl while he was running."

"Get him out of my sight, will you?" demanded Baldwin.

"Sure, sure," said the bartender, and called the dog away.

"I hate it," said Baldwin, gloomily, as he waited for Muir to take a chair and then sat down opposite, "I hate to see a poor beast suffer. They can't talk. That's the devil of it. They can't talk. They can't tell you where it hurts, and it makes me sick to see them done in."

He pursed his mouth with distaste and took a quick swallow of the beer. He was so moved that the highlight on his flat-faced emerald ring trembled a little.

"You're wondering why I'm here, I suppose?" asked Muir.

"I try not to guess at things," said the soft voice of Baldwin. "Will you have a cigarette? The guessing is what does the harm, because no matter how wrong it may be, the guess stays in one's mind."

"But what about the times when a guess is all one can have?" asked Muir.

"Those are the unlucky times," said Baldwin. "They cost money."

"Or blood," suggested Muir.

"Well, yes. Even blood—I'm afraid that I'll have to give you only a few moments, Mr. Croft."

"You know why I'm here, don't you?" asked Muir. "I mean, you wouldn't have to guess more than twice?"

"Well, I suppose so," replied the big fellow.

"In other words," said Muir, feeling his way delicately forward, "a man either can come because he wants to, or because he's sent."

"Oh, of course," said Philip Baldwin. "I know you're not out here for your own pleasure."

"But it is a pleasure, too," answered Muir.

"Is it?" asked Baldwin. "I mean to say, one likes to see for oneself."

"Ah, does one?" remarked Baldwin, with that slight ring of the voice which Muir had noted before. "But suppose you tell me the whole thing, straight out."

"Right from the beginning?"

"And to the end," nodded Baldwin.

Muir considered, parted his lips as though to speak, and then shook his head.

"I don't think I can do that," he decided aloud.

"Very well," murmured Baldwin, and submitted with a barely audible sigh. "But I wonder what's gained, finally, by dodging through so many fences?"

"Well, suppose that Shannon—" began Muir.

"Did Shannon send you?" snapped Baldwin suddenly.

"You know how Shannon is," said Muir. "He wouldn't want too much talk."

"I know. He doesn't change," agreed Baldwin. "I sometimes want to damn him and leave him damned."

"Ah, but we couldn't do that, could we?" asked Muir.

"No, perhaps not. Definitely, it is Shannon who sent you out?"

"I don't think that I can answer that," declared Muir, gravely.

"You can't?"

"No. I'm afraid not— I'm going to get another beer. Will you have one now?"

"I'll do with this, thanks."

Muir felt the eyes of Baldwin following him as he left the table carrying his empty glass. He had made very slight progress indeed, except that he had found weight in the name of Shannon. He had gathered that there was something a trifle strange in the background of Baldwin, but he had gone a single full step on the trail, no matter where it was leading. Dr. David J. Russo, now wanted for murder, seemed certainly as far from Greenwood as he was from his house in New York. And an unusual sense of self doubt was beginning to trouble Muir: He could not tell whether he had come into the country on the trail of the suspected murderer, or whether he was merely hoping, rather blindly, that he might find Katherine Edwards again.

He needed also to escape for a moment from the pressure which the examining eyes and the mere physical bigness of Baldwin exerted upon him.

That was why he had started for the bar to get a fresh beer. And on the way toward it something else occurred to his mind and made him swerve toward the outer door.

The big young fellow at the stove instantly left his place and found something of interest to stare at through the glass door- panes.

"Brightening a bit over there in the west, isn't it?" asked Muir.

"That ain't where brightness would do any good," snapped Steve, and continued to stare out the door. "The big rains come from the east."

Muir went on to the bar, slowly, for he needed more time than ever to think out his problem. It was considerably more complicated now, since he was sure that Steve was posted to keep him from bolting suddenly away. Perhaps Baldwin himself had not placed him under strict guard, but a very sensitive and accurate instinct told him that they were making him a prisoner in the house.

THE bartender, filling the glass of beer, kept his eyes down, with one wrinkle of a frown in the middle of his forehead; Muir carried the drink back to his corner table and sat down again. And as he approached, he noted that the whole upper face of Baldwin possessed a still and perfect beauty as far down as the eyes; below that point the torment began.

"You can't tell me whether or not Shannon sent you out," said the soft, gentle voice of Baldwin. "What can you tell me, Mr. Croft?"

"Are you doubting me?" asked Muir, smiling.

He felt again the reach and thrust of the eyes of Baldwin, probing him.

"I have to doubt most things, don't I?" asked Baldwin.

"Why not get hold of Shannon on the phone?" asked Muir, taking another step in the dark.

"You surely know that I can't do that," answered Baldwin, with the first real touch of impatience. "But just what are you doing out here, Mr. Croft? Couldn't Shannon give you a letter of introduction?"

"A letter?" echoed Muir.

"No, that's true," nodded Baldwin.

"Nothing written, I suppose," said Muir.

"No, nothing written," sighed Baldwin.

"The fact is," said Muir, "that I'm to establish contact and simply hold on until another man arrives."

Baldwin looked at him in amazement.

"Do they think that I'm about to slip and run?" he asked.

"You know how it is when there is more than one set of brains at work on a thing?" suggested Muir.

"I know; I know," nodded Baldwin. He looked at Muir as though he were comparing him with a picture in his mind. "Weren't you with the Lott and Cornish Sand and Gravel people, five or six years ago?" he asked.

"Not quite," smiled Muir.

"Not directly, eh?" asked Baldwin.

"No, not apparently," said Muir, still smiling.

The lips of Baldwin pinched hard together.

"Frankly," he said, "I don't like this very well. It's no pleasure for me to be treated like a child who mustn't be allowed to hear the real truth."

Muir made an appealing gesture with both hands.

"Can't you understand that?" he asked. "Can't you understand the positions?"

"Yes," admitted Baldwin, grudgingly. "Yes, I can understand it in a way. The fact is that you're not going to tell me anything. You're simply here to—feast your eyes on me. Is that it?"

"Well, more or less."

Baldwin passed a hand of impatient anger over his face.

"I hope you're satisfied, then," he said. "I hope that the rest of them will be satisfied, too. And may they be damned," he added in the softest of whispers. "May they all be damned!"

He pushed back his chair, breathing hard with emotion.

"What do you want to do now?" he asked briefly.

"I want to turn in and have a sleep," answered Muir. "I'm done in."

"I'll tell them to give you a room upstairs," said Baldwin. He added, bitterly: "There may be a rat or two.... But the four- legged kind don't matter. The two-legged rats are the ones that eat the soul out of a man, Mr. Croft.... Jerry, fix up Mr. Croft with a room."

Baldwin rose.

"You can understand my being busy," he said, dryly. "Not as busy as I once was, but pretty well employed. You'll excuse me for the time being, Mr. Croft."

"Certainly," said Muir, and remained at the table to finish his beer. He needed to add up his gains from Baldwin's conversation and he found that the results were quite nebulous. Some sort of a criminal or extra-legal background was suggested, certainly, but at the end what remained most vividly in the mind of Muir was the remark about "two-legged rats."

THE bartender appeared, grunting: "Follow me up!" and turned

to lead the way; and as Muir rose from the table he was aware of

the eyes of Steve, turning their brunt sidelong upon him. He had

again the impression that this was jail, and that yonder was the

jailer.

Jeff led him on through a pair of frowzy parlors. From door to door cigarette ashes had been trodden into the worn carpets and outlined a path clearly. There was a dank, heavy atmosphere of cookery and unaired humanity, and a clutter of chairs and old sofas upholstered in frayed velvet.

In the second parlor, a door at the left was closing slowly, softly as he passed through to a winding stairway that rose out of the corner of the room. As he climbed the stairs, Muir felt a slight draft of air and, glancing back, saw that the same door was open again. He could feel rather than see what stood beyond the threshold.

The worn heels of Jeff guided him up that dim stairway to the floor above and then down the hall to the second door on the left, where he paused and produced a jingling of big keys. He unlocked the door and pushed it open with a moan and shudder of rusted hinges. Muir looked in on a dingy room with an old four- poster bed covered with a spread which seemed to have been laundered gray instead of white. He walked in, saying: "This will do."

"Will it?" growled Jeff. "That's good, then."

He stood a moment on the threshold with his small eyes worrying at the face of Muir. Then he shrugged his shoulders, closed the door, and disappeared. His footfall creaked away down the hall, down the stairs. And a moment later Muir heard deep laughter from the floor below.

He went to the window. A big tree just outside bent down its branches glistering with rain and overlaid the rain-misted landscape with the black pattern of its trunk and boughs. Through the window the dull light that entered the room came as a stain more than an illumination. It was not middle-afternoon, and yet lamplight would have brightened the place.

On the wall, pictures of horses were the motif of the decoration.

Muir threw himself down on the bed, turned on his side, and closed his eyes. The fatigue of the night before, the poison of weariness which had been accumulating strangely in his brain during the past few days, now was pressing down on all his nerves with a steady weight.

He reviewed certain alternatives. It might be that the highly irritated Philip Baldwin would actually get in touch with Shannon, whoever that might be; and it might be that Shannon in a word could reveal "Mr. Croft" as an impostor. What would follow then, Muir could use a fine spread of imagination to foresee.

He had a feeling that Jim, the chauffeur, and Jerry, the bartender, and Steve, the fighting mastiff, were linked together under the absolute authority of big Philip Baldwin. They might be no more than family servants whom Baldwin had taken with him into a temporary exile, but Muir felt in them something more sinister.

HE determined to sleep for a half hour, and tried to set his

subconscious mind like an alarm clock for that space of time.

Then, quickly, in a quick numbness of fatigue, slumber rolled

over him and submerged him, and he carried down with him into

darkness the sharp-bearded face of Doctor David J. Russo, wanted

for murder, and Katherine Edwards with her green, clear, steady

eyes.

That subconscious brain of his for once was not honest. When he wakened, the light that came through the window was as pale as early dawn and his brain whirled for a moment in the effort to place himself in time and space. The musty smell of the tavern was what brought him to the proper identity, at last.

He sat up. Voices rumbled from the barroom, dimly, like machinery at work in the bowels of a ship. The day's end had come, and perhaps he had wasted a vital share of his time. He realized this with a sinking heart and above all with a sense of weakness, as though his own nature had betrayed him. Something was undoubtedly wrong; a brittle weakness in his knees told him that, as he stood up; and he had to make a sort of physical effort to clear his mind.

He had exploring to do and he required silence for it; therefore he did not cross the center of the floor where his weight would act with a greater leverage upon the boards, but he moved close to the wall, putting down his feet gingerly and keeping his weight as much as possible distributed on both legs.

So he managed to come without a single creak of the floor to the door. He turned the knob of it with the same gingerly care—and found it locked!

He could remember, distinctly, that when he first entered the room a key had been left on the inside of the door. It was gone, now, and therefore that door had been opened while he slept. It might be that deft hands had run through his clothes at the same time; but when he touched his pockets with rapid fingers he found everything in place.

The locking of the door changed everything. It was equivalent to a declaration of war, silently delivered, and all sense of weariness left Muir at once.

He would have confessed to fear out of the honesty of his mind, but for many years all real happiness had had in it the sharp ecstasy of danger intermingled. He was happy now as he leaned over the lock and began to read its mind with the sliver of steel which he drew from his coat. It was a simple matter for him to turn the heavy bolt. It required merely the brain of a child and strength in the fingertips before he was opening the door softly.

The key was on the farther side, half engaged, and he removed it to the inside as a matter of course. He found the hallway drowned in shadow as thick as sea-water. Only the doorknobs up and down its length glistened dimly.

HE tried the one opposite him. It was unlocked and gave on a

damp odor of decay. The finger of the electric torchlight touched

a high-stacked mass of furniture, old chairs turned upside down

on tables and couches, with red rust stains on the bottom

linings. Up the hall, the next room was locked, but he needed

only a moment's work to open it. He stepped inside and found the

last of the day looking into the room only as far as the center

table; the rest of the furniture was as obscurely in shadow as

the background of a Rembrandt.

His flashlight spotted a large book on the stand beside the bed. He stepped to that and found a Blackstone's Commentaries, with marginal notes scribbled thickly into the margins by one handwriting, but of different ages. For a dozen years the reader must have been writing his observations at the sides of the pages.

Muir turned from that to a closet door which stood somewhat ajar and as he pulled it farther open he saw a serried mass of neckties showering down like a rainbow from an inside bracket of the door.

A dozen suits hung within, all newly tailored, most of them with double-breasted coats, and by the width of the shoulders and the natty lines, he could be sure that he was in the room of Philip Baldwin.

While he scanned the rest of the room with the light, his fingers were automatically dipping into coat pockets, but he found them all empty, and in the entire chamber nothing of the slightest importance.

He returned to the door, listened to make sure that the hall was empty, and continued his investigations. He tried the next door on left, across the hall, and finding it unlocked he pushed cautiously into the dim, twilight atmosphere, where the darkness was hastened by the crowding branches of a tree near the window.

As he closed the door, he half-shut his eyes and took a deep breath, for mingling with the musty odor of the old house he detected a thin scent of fragrance that called him back to some memory, near or far. A moment later he had placed it, for Katherine Edwards had used a touch of just such a perfume.

Curiosity made him cut the dimness with the edge of his torchlight, left and right. It gleamed on the false marble front of the fireplace, it flashed with brilliance from a mirror on the wall, and in between it cut across the bed, the table, the open suitcase on a chair. He made a step toward the latter before another instinct halted and turned him back to the door. He had his hand on the knob when footfalls entered the hall, one light and quick, one soft but weighty. A light in the hall snapped on and etched in the door with a broken line of radiance from which Muir backed away across the room. Pie was in the middle of it when the voices of Katherine Edwards and Philip Baldwin paused at the door.

THE corner wall stopped the retreat of Muir. He could not help a glance towards the window, but since he knew there was no time to clamber through this, he resigned himself suddenly and sat down in a chair near the head of the bed.

There he remained, relaxing with folded arms and crossed legs as the door pushed open and showed the girl entering, with the huge shadow of Philip Baldwin flooding over her. He came a step after her, half shutting the door behind him. The sharp tang and purity of the outdoors passed through the room. On the shoulders of Baldwin's overcoat the raindrops, entangled in the upper fuzz of the tweed, shone brilliantly, but since the hall light was at some distance, the angle at which it entered the doorway embraced Baldwin alone and left the rest of the room in an accentuated darkness.

"I ought to wait, but I can't wait," said Baldwin. "I've got to know it now! Kate, do you still care about me?"

"Ah, of course I do," she said. He kept a nervously doubled fist against his breast and she put up a caressing hand against it as she spoke. "No—it's not any good," said Baldwin. "When you look at me, you're changed, Kate. I remember everything too well, you see."

"I haven't changed. I won't change," said the girl.

"There you're fighting yourself," said the soft, gentle voice of Baldwin. "You're whipping yourself forward, dear, but the soul doesn't respond. Tell me. Isn't that the truth?"

She shook her head. "I won't let it be the truth," she told him, "Do you think where I've given my word — I mean, when I've ever loved—"

"Hush!" said Baldwin. "The truth is that you can't look at me. Isn't that the actual truth?"

"It isn't the truth! I do look at you—"

"And pity me, Kate. Isn't that it?"

"And love you, and want to weep about you."

"Do you think that we can build it into a great, beautiful life together?" asked Baldwin. "Do you still want time before you tell me, definitely?"

"A little time, my dear," said the girl. "Does that wound you? Does it hurt you? I'll want to kill myself if it has!"

"A man has to take the blows, if he's worth a rap," said Baldwin.

"I have hurt you," breathed the girl.

He lifted his big head, and by the light from the hall, all that Muir could see clearly was the noble, polished forehead.

"It's no more than I can stand," said Baldwin. "But I must leave you, Kate."

"Not now," she pleaded. "Stay just a moment longer and let me try—"

"God bless you, my dear," said Baldwin. "But I think I shall have to be alone."

He closed the door. The thick blackness swept over the room for from the sky came only a sooty grayness that entered through the window no more than a step. Then a switch by the door snapped on and threw a dazzle into the eyes of Muir from the naked unshaded globe that hung from the center of the ceiling.

"That was a little thin, wasn't it?" asked Muir, without rising from the chair.

He saw the outcry swell in her throat, but she set her teeth over it with a swift, fine self-control.

"Pathos, I mean," he repeated, standing up. "There was just a dash of Pathos in Baldwin's farewell. Or what would you say?"

"Do you know that I'm only half a breath from a scream?" she panted, staring at him.

"You'd better get off those wet clothes or you'll be only half a breath from a bad cold," suggested Muir.

Her hands began to unbutton her coat. They stopped that rapid work as she exclaimed: "It hypnotizes me to see you so perfectly calm; as though we'd been talking here ever since tea. What on earth are you doing here?"

"LET'S talk about big Mr. Baldwin," said Muir. "I'll lend

you an idea that ought to be useful. That clever fellow wanted

you to think that he was resigning himself to a deep agony of the

spirit. But as a matter of fact he was simply playing a clever

hand of cards and taking a trick; and now he's planning the next

shuffle and the next deal, which may have all sorts of surprises

for you. One way or another he intends to have you, don't you

think?"

"It wasn't sickness at all that brought you to the doctor's office last night," she told him. "You have something in your mind; and I don't want to be a silly little fool and make trouble for you, but hadn't you better explain?"

"If you called Mr. Baldwin with those great big hands of his, there would be trouble, I suppose," nodded Muir.

"I don't want to call him," she answered. "I don't want to do anything melodramatic. But you know I can't take this for granted, after all."

"Can't you," asked Muir, smiling a little.

"Certainly I cannot," she answered.

"Tell me, honestly," said he. "After the first surprise—are you in the least degree shocked or alarmed or in fear on account of me?"

"No," she said. "I mean—well, it's true that I'm not afraid."

"You don't think that I went to the doctor's office to burgle it, do you?"

"No, I suppose not."

"And you don't believe that I'm out here to rob the tavern?"

"Perhaps not."

"But you're guessing at another logical reason that would bring me here?" asked Muir.

She said: "You'd better go, hadn't you?"

"You want me to tell you why I'm here, don't you?" he insisted.

"Yes," she admitted.

"Well, I don't look like a romantic fellow, do I?"

He felt her eyes on his forehead and on the hard-drawn lines of his face.

"No," she said. "Not exactly romantic."

"However," said Muir, "I'm here for a tremendously romantic reason. I want to perform a rescue."

"Ah, good," she answered. "Rescue what?"

"You," said Muir.

"And from what?" she asked rather patiently.

"From danger, of course," said Muir.

"What danger, please?"

"All the danger that's under the roof of the tavern; and there's plenty of it, I have an idea."

"You are a bit romantic, I'm afraid," she said without interest.

"Why are you here, for instance?" he asked.

"Doctor..." she began, and stopped suddenly. "I simply came out for a bit of country air," she concluded. "The doctor told me I should."

"Because you'd had too much of the city?" asked Muir.

"Yes."

"I'm not surprised," he went on, with ironical sympathy. "Last night I noticed how worn you were, and how bad your color was. But the doctor... did you expect to find him here?"

"I don't see..." she began.

"You did not find him, did you?" asked Muir.

SHE started, and then lifting her head, slowly, she looked at him with new eyes, enthralled by some totally unexpected danger, as it seemed. "What do you mean by that?"

"I mean an entirely simple question," he said. "You came here because it was said the doctor wanted you. When you arrived, you asked about him. He was not in. He continues to be out. Isn't that the truth?"

She took a quick breath, but let no words escape from her lips.

Muir went on: "The doctor was out, I suppose? When you asked for him, he would be back presently? Perhaps he was out on a call. Didn't the story go something like that?" She said nothing.

"Well, I'll trot on back to my room," said Muir, going toward the door.

"Please stay for another moment," said the girl.

"Just as you wish," he answered, and turned back to the window.

A shaft of light from another window beneath it showed the slant of the hillside in the rear of the tavern, the loom and lift of a great tree trunk in the distance and a few shrubs with ragged leaves on the tips of the branches nearer to hand. From the downpour of rain, which was slackening now to nothing, little runlets of brown water trickled down the bank. Muir eyed it automatically for an instant before he turned toward the girl again.

"At your service," he said, smiling.

"Now please tell me what you think," she asked.

"I think I see a nurse," said Muir, "but where is the sick person she is taking care of?"

"There is..." she began, but stopped again and even glanced rather apprehensively toward the door.

"There is to be a case presently. Isn't that it?" demanded Muir.

She slipped down into a chair and, with her head raised high and her eyes studying the opposite wall and her hands folded in her lap, she remained impassive for a moment.

"I have to think just a bit," she said.

Muir stepped up behind her and laid a hand on her shoulder.

"Doesn't that help?" he asked. "Help the thinking, I mean?"

She turned her head, slowly, until she could look up into his face.

"Yes," she answered gravely. "It helps—it helps to take the horrible, sick fear out of me."

She was looking straightforward again.

"And in the meantime," said Muir, "that noble friend of yours, Philip Baldwin, has a chance to show his nobility and give you a glimpse of his suffering soul. That's one convenience in having you out here, isn't it?"

"Will you not talk about him, please?" asked the girl.

"Not a word, if you wish," said Muir.

HE drew up another chair beside hers and facing her. As he sat

down, he saw that she was swallowing with a hard effort, fighting

back a panic that kept growing the more she looked into her mind.

Muir took her hand and said nothing.

"Will you tell me this?" she asked at last. "Will you tell me what brought you here?"

"Chiefly you," said Muir. Half-frowning, she looked at him steadily. He ran a hand quickly over his face.

"I know," he said. "It's bad. Full of long nights and short days, and all that. But the truth is still what I say. It's chiefly you that brought me here. On a rather blind trail. After I left you last night, I listened under the office windows and heard you telephoning into the country. So I came out here pretending to want to see Mr. Baldwin and I've seen him. He's a bit suspicious but he's not quite sure that I'm a fakir. If he were sure, I think he'd wring my neck. What do you think?"

She put up a hand to her throat and looked at him with eyes made blank because of what they saw inwardly.

"You can't talk about him," nodded Muir. "There was a time when he meant most of the world to you. Isn't that true?"

She agreed with a gesture.

"Why did you come to the doctor's office last night?" she asked.

He said, faintly smiling: "Because I had a premonition that I'd find you there, of course. Is it bothering you to have me talk like a silly ass at the very moment when you're beginning to be afraid?"

"You know it doesn't," she said.

"Whatever I had to say, you'd listen?"

"Yes."

"As though we had a thousand safe hours ahead of us?"

"Yes," she said.

"And I'm something more than a bit of middle-aged grotesquerie?" he asked.

She smiled at him, with the fear gone from her eyes and only a slightly amused human consideration left in them.

"Something more. A great deal more," she admitted.

"Now you want to know why I was at the doctor's office? Because I was following a friend who was there before me. Everett Franklin."

"The newspaper man?"

"That's right."

"Did you have an idea that he could be there?"

"I was fairly certain that he was there."

"But of course—"

"And he was. I found him."

She opened her eyes, at this.

"Are you steady?" he asked.

"Like a rock," she said.

"HE was an old friend," said Muir. "I'd run across him in a

dozen different parts of the world when he was hunting news and I

was hunting —other things. He had one of those beautiful

faces that you never find outside of Hollywood. He couldn't grow

older. He was one of those bright little boys who always have the

answer. There was no more fear in him then there is in a ferret,

and he was always going into dark holes and bringing out the

truth, sometimes with the blood still fresh on it. One part of me

loved him. Do you understand?"

"You've put him in the past. He's dead!" murmured the girl.

"He was dead," said Muir, keeping firm hold on her with his eyes. "I found him in the closet of that room with the landscape wallpaper."

She took the news of the death with a wonderful calmness.

"He had been stabbed to death," said Muir, still holding her eyes strongly. "And the murderer wasn't satisfied with that. He'd leaned and slashed him across the face—crisscross slashes—a lot of them, over and over again. With something as sharp as a scalpel."

The strength went out of her, suddenly. Her head dropped to the back of the chair. Her eyes closed. By the blue gray of her lips she seemed to have fainted, but Muir saw the faint pulsation of the artery at the base of her throat.

He stood up and went to the window, to lift the sash of it so that fresh air could blow in; and as he did this he saw the figure of a man pass up the bank at the rear of the tavern, a tall, alert, sure-footed fellow in a raincoat and a slouch hat with a heavy pack strapped behind his shoulders.

Through the thin mist of the rain, the light from the lower window played upon him clearly enough, striking upward to follow him as he reached the brush.

Then, as one does after climbing over an obstacle, he turned and looked back down the bank which he had just passed. Muir saw the face of his quarry, that same face which Inspector Tory so eagerly desired to trace, with the pointed beard giving it an old-fashioned professional neatness. As Muir watched, Doctor David J. Russo turned again and stepped out of the misty light into darkness, leaving the brush trembling behind him and a few of the dead leaves slowly adrift down the bank.

PETER MUIR, undercover agent, has at last caught up with his quarry. But he is a virtual prisoner in that country tavern, and is thwarted from stalking the murderer of his closest friend. Yet Muir is a man of great resourcefulness, and you will thoroughly enjoy watching him try to extricate himself from the strange predicament in which he finds himself.

The concluding installment of "The Face and the Doctor" by Max Brand comes to you in next week's DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY.

Detective Fiction Weekly, 29 May 1937, with second part of "The Face and the Doctor"

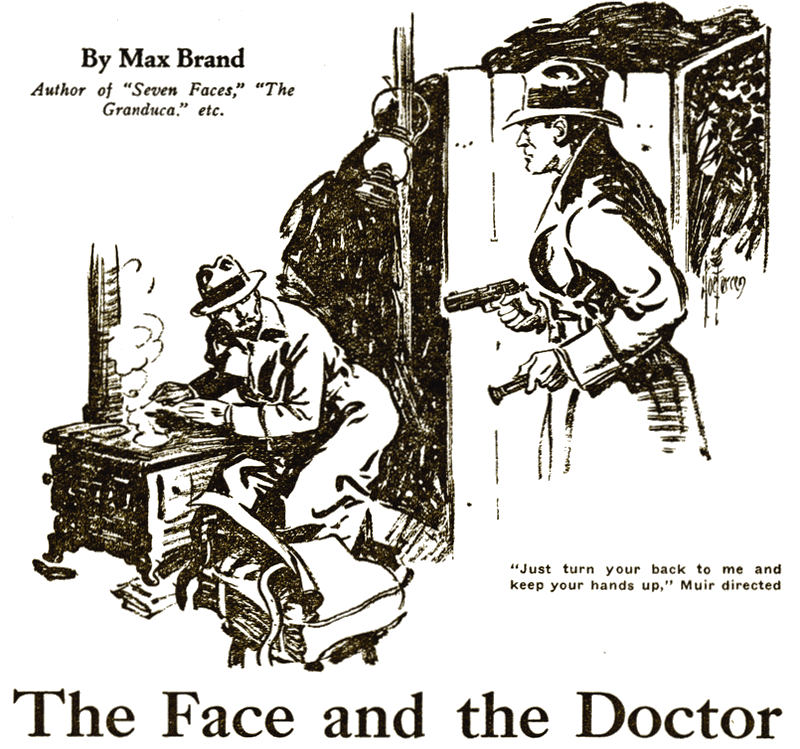

A scandal big enough to rock New York! And Pete Muir was

just the man to get the lowdown on the upper underworld.

"Just turn your back to me and keep your hands up," Muir directed.