RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Amazing Stories, March 1935 with "Millions for Defense"

We are very glad to give our readers a story by Dr. Breuer. He will be remembered by our readers as a favorite author of many years' standing, and in the near future we shall have the pleasure of giving more of his works. This is one of those stories whose finale can never be successfully guessed of; you have to read it to the end.

"IT'S about time you quit fooling around and got down to some real work. You've been tinkering long enough."

The coarse, red face of Jake Bloor spread into an unsympathetic leer, and he grunted contemptuously.

"I promised your mother I'd put you through school," he continued. "Now I'm through with that, and a big bunch of boloney I call it."

That was the welcome that awaited John Stengel after graduation from college, upon his arrival at the only home he had, that of his uncle, who was a banker in the small country village of Centerville.

"Yes, sir," replied John, biting his lips.

His uncle screwed his lips into ugly rolls around his cigar, and then took it out and spat on the floor.

"This job I'm giving you in my bank," he went on, "is not a part of my promise to your mother. That comes out of the kindness of my heart."

That mind can and does triumph over matter was demonstrated again by the fact that John did not turn on his heel and walk out of the house, never to return. John Stengel, known to his fellow-students for four years as Steinmetz Stengel, stood five burly inches above his stocky uncle; his blue eyes blazed a resentment that was everywhere else concealed by his quiet and respectful bearing. The powerful arm that bent to run his big hand through his yellow hair, could have knocked his corpulent uncle off his feet, but it dropped quietly at his side, and he again said:

"Yes, sir!"

For graduation is a bewildering experience. The world is wide, and one is not sure just which way to turn. A fifteen-dollar a week job as a clerk in a country bank was nevertheless a discouraging jolt to the rosy aspirations that flowered at this time of the year, quite as brilliantly as did the roses; for behind him were four splendid years of distinguished achievement as a scientific student.

However, just now there seemed no way around it. The offer of this job from his uncle had come several weeks before. Jake Bloor had not presented it kindly nor gracefully; he had rubbed it in with patriarchial magnanimity, and with conspicuous contempt for John's scientific training, which he had permitted only because of his promise to his dead sister, when she had placed the child John in his hands. During the weeks between his uncle's offer and the date of graduation, John had thought hard and tried everything. Especially he had discussed the problem with his fellow-students and his instructors.

He had nothing else to fall back on. His parents had died when he was a child and left him nothing but the ill-natured promise of a grumpy uncle. He had tried in vain to get a position of any sort; but the country was in the grip of the most severe financial depression of the century. No positions were available anywhere. His failure to locate anything in the way of a livelihood, after several months of correspondence during his last year of school, was not surprising, with ten millions of unemployed in the nation. The bank-clerk job, even though it was offered largely as an insult to John's scientific training, seemed like a straw to a drowning man. It had occurred to John that Jake Bloor was prosperous even while other country banks were failing.

"Your uncle seems to be a good business man, and it will do you no harm to learn something about business," one of his student friends said to him.

"Keep up some scientific reading," the Dean of the Engineering Department said to him, "but by all means take the job. Keep your laboratory hand in practice somehow."

The Dean was much interested in John's future, and consulted with John at length about the matter.

"You will get there in the long run," the Dean said; "but do not permit yourself to become stagnant."

The suggestion of John's roommate, who was as brilliant and clever an engineer as John himself, seemed to offer the most promise of interest.

"These country banks simply invite robbery," Bates had said. "Perfectly simple to walk in and help yourself—"

"You mean that I ought to rig up some stuff to protect the shack in case of robbery? Good idea!" John was interested.

"Easy enough, wouldn't it be? And a good way to amuse yourself."

"And Hansie, dear," Dorothy had said to him, "I know you can do something great no matter where you go. This is only temporary, and we'll be patient, and some day we shall have that home together."

Dorothy was at the same time the Light of the World, and the hardest problem of John's life. They had decided that they could not live without each other; and yet here they were, finding it impossible to live together. But, as Dorothy held on to his arm, walking with him across the campus in the moonlight, and held her soft, brown head close to his and gazed at him with limpid, sympathetic eyes, John felt that he could and must accomplish anything in the world for this wonderful girl that a kind Providence had given him.

CENTERVILLE was certainly a drab and dismal place, after the glitter of life on the campus, whose great, picturesque buildings had thrilling things going on in them. Here there were half a dozen tiny business buildings strung out along two sides of the dusty highway, and a score or so of cottage residences scattered about, and beyond those, monotonous prairie in all directions.

There were two general stores; the one in the brick building was carelessly run and had a poor stock; the other was better arranged and more ambitious, but its wooden, gable-roofed shack looked almost ready to collapse in upon it. The garage was the busiest and most systematic-looking place in the neighborhood. Two "caffis" (in reality soft-drink parlors), one ragged and catering to coarsely dressed men, one somewhat cleaner and filled at noon with high-school students; a hardware store with dirty windows and a heap of nondescript junk within them covered with the undisturbed dust of years; a drug-store with its window full of patent-medicine and cosmetic posters mottled by fading, all gave John an indescribably dreary feeling of lostness and futility. The traffic that slipped down the highway all day, and the color and activity of the two filling stations, Standard Oil at one end and Conoco at the other, did but little to relieve him.

The bank itself made John think of the little toy banks that children play with; and when he first set eyes on it he was sure that it must have a slot in the top to drop nickels in. It was square, somewhat larger than a garage, with white-painted drop-siding and a flat roof. Within, it had iron bars across the windows, a single room divided in two by a counter with a rusty iron grill, a big iron safe set on wheels. The floor was unpainted and splintery; the ink in the bottle on the sloping-topped table at the door, was dry and caked, and the pad of deposit-slips upon it was yellow and curled with age. Hardly anyone passed along the little street all day, and only rarely stepped into the bank itself. Between two and three in the afternoon there were a few merchants; Saturday evenings there might be three or four farmers in the bank all at once.

JOHN smiled when he first saw the place. Providing there were anything to take, it would be the simplest and easiest of tasks for the modern bank-robber to clean the place out and get away. It certainly looked as though there might be something to take. His uncle Jake Bloor's huge, sprawling, white house brooded over the village like some coarse temple; and his big, throbbing cars glittered back and forth from the city, boasting insolently of money. It seemed especially insolent to John, because he knew there were countless unemployed who did not know where their next meal was coming from, and countless others who were ground almost flat to the earth by debts and losses at this particular time, while his uncle lorded it about without a care in the world nor a thought for others. It did not seem fair that this crude, heartless man, who had never done the world any material service, but had only selfishly pinched off for himself generous portions of the world's money which he had handled, should be rolling in safety and luxury, at a time when men who had invented and built and taught and organized were being faced with grim want. Things weren't right in the world.

John was young and human. We cannot blame him, therefore, for the fact that when he did eventually get to work to devise some scientific means for preventing a robbery of the bank, that his motive did not consist of any overwhelming loyalty to his uncle's bank. He did it merely because he took pleasure in the creation of something that would operate. The abstract idea in the mind, when the concrete working out of it does things that can be seen and felt—that is the thrill of the creative spirit. John loved his figures and his drawings; he loved the coils and the storage batteries, the clicking little gears and the quick little switches that ticked and made swift little movements of their own accord, as though they were living and intelligent things.

FOR many long, luxurious weeks he did nothing; it was a delight to be merely a sort of vegetable; to rest from the rush of the last weeks in school; to shed completely, if temporarily, the strain of looking into the future. His mind hibernated during that time, and lay fallow; for it required no effort to discharge his simple duties as clerk at the bank; and life in Centerville was an excellent anesthetic. His body made up what it had missed in exercise by long walks down the highway and along the railroad tracks. Long letters to and from Dorothy punctuated the soothing monotony, and the thrill they gave him was all the excitement he wanted. They must have been good letters, as we might have judged could we have but seen him slip off into solitude on the first opportunity after their arrival, his face breaking out in delightful smiles—only no one saw him.

FINALLY, one day in the fall, after the heat of the summer was out of his bones, he began to get ambitious. First he put a coat of bronze paint on the rusty window-bars and on the grill-work of the counter.

"Looks like a new place in here," said old Larson, the town constable, who was the first one to come in and see it.

John smiled.

"I believe my sixty cents' worth of paint will boost the confidence of the bank's depositors thousands of dollars," he bantered.

Jake Bloor guffawed when he came in and saw it.

"All right!" he sneered. "If you want to waste your pennies that way in this dump. But I think you're a damned fool!"

This was not very encouraging, thought John, for broaching the idea of installing some equipment for protection against robbery. He decided to say nothing about it for the present, and await a better chance.

A week dragged out its length after that, and John began to get restless. The autumn coolness was beginning to be stimulating and after his most excellent rest, John wanted to be up and doing something, using his hands and his brain. The matter of devising some protection against robbery in the bank was constantly on his mind. He turned over in his head various projects. He watched his uncle, constantly hoping for a chance to mention the matter.

THEN one morning the city daily came in with two-column heads about the robbing of the bank at Athens, forty miles away. Three masked men had walked into the bank in the middle of the forenoon; one had forced the clerk to hold up his hands at the muzzle of a pistol, while the others had cleaned out the safe, gotten into a car, and disappeared. Eighty thousand dollars worth of cash and negotiable securities had vanished. No trace of any kind could be found of the robbers.

"I could rig up some stuff to prevent that sort of thing in your bank," John said, forcing his voice into a casual tone over his pancakes.

"Prevent what?" growled his uncle.

"Your bank being robbed, like the one at Athens," John said.

"Oh!" and a couple of grunts from the uncle.

"Doesn't it worry you? It might happen to us, you know." John was showing anxiety in his voice—whether for the fate of his uncle's bank or in his eagerness to be at some technical work, again, he could not tell.

"Oh, I suppose." And Jake Bloor went on reading.

"Do you mind if I fix up some apparatus to protect you?"

"All a bunch of humbug!" Jake Bloor exclaimed impatiently, gnawing at his cigar. "The swindlers are always after me with the stuff. They want to sell something, that's all."

"No. I don't mean for you to buy anything," John urged. "I'll make it myself."

His uncle roared derisively.

"That would cost more than ever!"

"It wouldn't cost you a cent!" John explained, holding down his anger with difficulty. After a moment's silence he regained his control.

"If you don't mind," he continued, "I'll fix it up for you at no expense to yourself."

"You're a damn fool!" Jake Bloor sneered. "But go ahead and have your fun. Only look out and don't do any damage. That's all I care about."

He got up and walked out of the house. In the door he stopped and snorted back at John:

"And don't kid yourself too much. Those fellahs are on to these tricks. Before you could kick off your alarm they would have you shot. Better take care of your hide."

John thought it over as he walked to the bank that morning.

"If he invites robbery, I ought to let him be robbed," he thought. "But, if he should be robbed, as it is probable that he will be, his bank being the richest as well as the most rickety for a long distance around, where would my job be? And, as four months writing of applications all over the country hasn't got me an answer, where would I be without a job? Seems that it is up to me to protect the bank whether he wants it or not."

Then his mind turned to the technical parts of the problem and began to run quickly about among them.

"I believe he is right, too," he thought, "about kicking off an alarm under the counter. That is an old dodge, and the robbers are probably ready for it. There must be a way around that."

FOR a solid month John was happy. He was the same old Steinmetz Stengel, whom his fellow-students gibed at, and at the same time loved so well, going about in an abstracted gaze, studying some complex problem in his head, or spending every spare moment of the day and many hours at night with the slide-rule and drawing-instruments, and with tools and materials, giving some astonishing child of his brain the outward concrete form that was necessary to make it a visible and functioning thing among men. Packages in corrugated paper and wooden boxes arrived for him at the little railway station; and there were a few automobile trips to the city.

When the thing was finished, it differed vastly from the usual burglary protection equipment. Nevertheless it was quite simple. The keynote of it was a row of photo-electric cells just above his head, which received daylight from the window behind him, and permitted a steady flow of current from a storage battery, whose charge was maintained by a trickle charger from the lighting current. This storage-battery current held down a relay armature. Anything that cut off the light from the photo-electric cells would shut off the storage-battery current, release the relay, and set off the works.

WHEN he had gotten it made thus far, he tried it out several times by raising his hands above his head while he stood at his window, as though he were facing a bank's customer.

"Hands up!" his imagination supplied the robber's command.

His hands went up; there was a click, and the three one-quarter-horse-power motors began to whirr.

The usual device in the country bank is a big alarm bell on the outside of the building. This had been a conspicuous failure in a number of recent robberies in the neighborhood. Those who were summoned by the alarm came too late or did not have nerve enough to interfere. In one case the accomplices on the outside had found it a convenient warning to help them get away, and in another they had held all the arrivals at bay, and made a good getaway with the booty. John discarded the idea of the alarm bell to awaken the village, and looked for an improvement on it.

A drum of tear-gas supplied the solution. One of the motors operated by the relay was so arranged as to shoot a blast of tear-gas right across the public side of the bank room, just where the hold-up men would be standing. A telephone-pair to the city fourteen miles away, rented at two dollars a month, comprised the next step; over these wires he arranged for an automatic signal in the sheriff's office, which would announce that the bank was being robbed, just as soon as the storage-battery current was cut off by the raised hands in front of the photo-electric cells.

A second motor set off by the relay, located in a box under the building, closed the outside door and shot an iron bar across it to keep it closed. John also reinforced this street door by screwing to it a latticework of iron straps and painting them neatly.

He felt highly thrilled the evening that he gave the apparatus its first trial. He tried it after dark, and therefore had to put a strong electric-light bulb into the street window to replace day-light, and instead of tear-gas he used a drum of compressed air. He rehearsed the whole scene in his mind: the door burst open by masked men, the pistol stuck in his face, and demand: "Hands up!" He put his hands up in as natural a manner as possible, and his delight knew no bounds to hear the relay click, so softly that no one not looking for it could possibly have caught it; he was even moderately startled at the sudden loud hiss of escaping air, and the street door slammed shut in a ghostly manner. He walked around in front of his window in the latticework on the counter, and felt the compressed air from the tank still blowing right across the place where the imagined robber was standing.

That ought to have been enough. It was amply sufficient to take care of any robbery that might have been staged. But John had a third motor at hand and some vague idea in his head. There was still something lacking, though he could not quite put his finger on the lack. For several days he was uneasy with the half-emerging thought that there was still something that he ought to add to this. But, try as he might, nothing further occurred to him. The arrangement, as he had it, seemed to be enough, and that was all he could think of.

He therefore demonstrated it to his uncle one evening. Jake Bloor said nothing, which was unusual for him. He was rarely silent. It may have meant that he was impressed; it may not. He did manage to keep the contemptuous look on his heavy red face. But he walked out without having said a word. The next morning he threw the newspaper sneeringly across the table at John, who was eating with his head bent down, thinking of Dorothy. John glanced at the captions announcing that another bank had been robbed, and that the bank clerk, who had been in league with the robbers, had handed out the booty and was also under arrest.

"Good idea!" drawled Jake through his nose. "Combine that with your plan. Load up the robbers nicely and then turn on your tricks. With a gas mask you can take the swag off them and hide it before the police come "

JOHN heard no more. His mind was busy again. He saw the danger to himself. And, as never before, he observed the paltry meanness of his uncle's character. There was some deep subtlety in Jake Boor's sarcastic persecution of the earnest, ambitious boy, which John could not comprehend. That Jake hated John seemed to be clear. But why? And why had he gotten him there apparently at his mercy for the purpose of getting him into trouble? The only thing that John had to go on was that his uncle's old, patriarchial conception of the "honor" of the family had been hurt when John's mother had run off and married a poor but clever mechanic. That was in the eyes of all her relatives a mortal sin, not even possible of expiation by her unoffending son.

But, John's mind ran more to mechanisms than to the tangled personal relationships of the family. A few days of hard thinking convinced him that there was only one way to protect himself, and that was to include himself in the field of the tear-gas. He would have to take his medicine at the same instant as did the rest of them. One October afternoon, out on one of his walks, he strode down the highway into the dusty sunset, and ahead of him a farmer was raising a tremendous dust in a field, getting together, with a horse hay-rake, a lot of old weeds for burning. As the farmer moved his lever and pulled his lines, the row of curved steel tines beneath him poised and waited, and then pounced upon their prey, and John got an idea. He thought of a use for his third motor.

He was soon busy again in his improvised workshop, putting together two affairs that resembled big hay-rakes, each as tall as a man; but the tines were of rigid steel, and when they closed toward each other, they could grip a man as tightly as a huge steel claw, and hold him immovable. He installed these, one on each side of his teller's window at the counter, with the motor under the floor so arranged that it could rotate them against each other and slip them past a catch which would lock them firmly together. When the photo-electric relay went off, anyone standing in front of the window would be raked in, clutched, and held in a steel fist, six feet tall. Yet, when these claws were turned back out of the way, painted with bronze paint, they mingled with the bronzed grillwork of the counter, and were hardly noticeable.

For some time Jake Bloor had been talking of taking a trip West for a several weeks' stay. There was no mention of the purpose of the trip, and it was discussed in a sort of secretive way, causing John to half suspect that his uncle might be bound on a bootlegging expedition. But he cast it out of his mind, considering that it was none of his business. He was too worried anyway, to think of that, by Jake's stern admonitions about bank affairs.

John was thoroughly frightened for Jake Bloor held him closely responsible for the veriest trifles as well as for the largest affairs, and yet had not properly inducted him into an adequate knowledge of the bank's affairs. It was an unfair position for John, and he felt like a blindfolded man walking a tightrope across a chasm; he was just trusting to luck that nothing went wrong before his uncle returned.

"Don't pass up any good loans," his uncle growled at the breakfast table on the day of his departure. "But, if I find any rotten paper in the vault when I get back, I'll wring your neck."

John said nothing, but was determined in his mind to loan nothing, and sit tight waiting for his uncle's return; for he could not tell good paper from bad. His business was engineering.

"I'll stop at the bank yet before I leave," Jake said, with an air of thrusting a disgusting morsel down an unwilling throat.

ABOUT the middle of the forenoon, the loneliest time of the day, John heard his uncle's car drive up in front of the bank. He could see suitcases strapped to the rear of it. Two men walked into the bank along with Jake, one of them carrying a large suitcase.

Jake Bloor drew a big pistol and levelled it at John with a sneer.

"Well, let's see how your plaything works," he said in a hard, ironic voice.

John protested vigorously, "Tear gas is no fun "

"Do you suppose I really want a dose of it?" his uncle roared. "Don't you dare put up your hands. Keep them on the table where I can see them. No kid tricks, either!"

His grim harshness now alarmed John.

"I'm more afraid of that big pistol than of the gas," John protested again. His voice stuck in his throat, and lights danced before his eyes; the whole business was such a shock, that he could not puzzle it out, though his brain roared like a racing motor in the effort to make head or tail of it. "That thing might go off and hurt somebody."

"Damn right it might!" his uncle growled. "That's why you had better be careful and not play anything on me. Keep your pretty hands still, or I'll ruin them with a bullet. Now, turn around, march over to the vault, and bring me the tin boxes with the cash and the bonds. Go on, damn it! I mean it"!

Jake snapped the hammer of the revolver, and John, turned with considerable alacrity and went after the tin boxes of valuables in the safe. His face was pale and his hands trembled. The weakness of his ingenious plan was being shown up unmercifully. His uncle had no learning, but was diabolically clever in a practical way. John now expected to be the butt of his cruel sneering for weeks to come.

"I guess you win," he laughed nervously at Jake. "I give up. My apparatus was no good, and the laugh is on me."

Jake stamped violently on the floor.

"By God! I told you to get those boxes of bonds and cash. If you think I'm fooling, you're due to learn something in about ten seconds. This bank is through, do you know it?"

John reasoned rapidly. The only thing to do was to go ahead. If it was a joke, it would be interesting to see how far it would be carried. If it was not a joke, what else was there to do anyway? After all, life on nothing with no prospects was still considerably better than a bullet through his vitals.

"And don't touch anything, and keep your hands down low," Jake reminded him with a thin ironic leer in his voice. "If you don't believe I'll shoot, just try something."

Like a magician on the stage, anxious to show that he has nothing up his sleeve, John avoided touching anything but essentials, and touched these clearly and gingerly. He handed over some $200,000 worth of negotiable valuables from the safe, truly a princely sum for such a tiny bank. The idea occurred to him when it was too late, that he ought to have had some sort of trip or switch or button in the safe itself. That is, if it were really too late. Perhaps this was just a good chance to discover the defects of his apparatus and elaborate upon it. If this were only a test, he was certainly learning rapidly. His head was already full of improvements, and he was willing to forgive the grimness of the joke for the help it afforded.

The two other men held John covered with pistols while Jake Bloor stowed away the tin boxes in the suitcase.

"Now," Jake said again in that offensive, thick-lipped sneer, "I suppose you have been wondering how I am going to get out of here and keep you from pulling something. Well, it's like taking candy from a baby."

He approached the window again.

"Keep your hands down on that desk!" he commanded.

Jake Bloor took out his pocket knife and went for the wire that was concealed on the outside of the cage.

"Look out! Don't—" cried John in alarm.

"Ha! ha!" Jake thoroughly enjoyed his big laugh. "You thought I was too dumb to notice that this was your main feed wire from your battery under the floor, to your little light bulbs. Ha! ha! ho! ho! Your old uncle's not so dumb!"

"But—" John tried to protest again.

He was too late.

"Shut up" his uncle barked sharply, "and keep your hands down."

"O.K., joke or no joke," thought John. "It's on his head."

He shut his eyes tightly and took a deep breath.

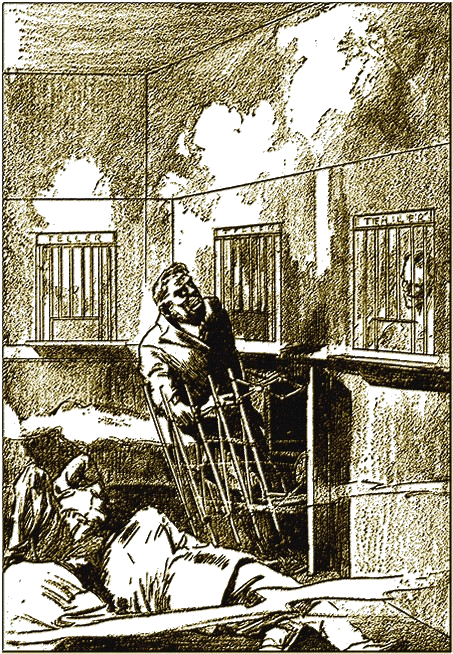

Jake cut the wire and yanked out a big length of it, which he started to put in his pocket. But he did not get that far with it. John heard the faint, comforting little click. There was a harsh hiss of gas. The door slammed ponderously shut and its bar clanged to. In front of the teller's window there was a whirr and a clash. Loud screams rent the air.

John could not resist opening his eyes, in spite of his knowledge of what the gas would do to them. Just for an instant, before a searing pain cut fairly into them, he saw kicking, struggling, writhing, screaming figures rolling on the floor, and just in front of his teller's window, his uncle was squeezed flat in a cage of bronzed bars, unable to move but only to give general twitchings. Then John got down slowly and lay on the floor, because of the stinging in his eyes, nose and throat.

He saw kicking, struggling, writhing, screaming figures

rolling on the floor, and just in front of his teller's window,

his uncle was squeezed flat in a cage of bronzed bars.

A thousand swords burned into his eyes; he sneezed and coughed and felt so miserable that he could neither remain on the floor nor stand up; he kept squirming and writhing about. He could hear the others groaning and writhing about and kicking the floor, and the loudest lamentations came from his uncle, hung up between the steel rakes. But no attempt that he could put forth was able to get his eyes open, which, in spite of his pain, he regretted. At that moment he would have given years off his life for a sight of Jake Bloor pinned up against the counter and gassed with tear gas, holding on to his suitcase full of money.

It seemed a hundred years of flashing, stabbing misery before relief came. Actually it was twenty minutes after the breaking of the wire when the sheriff from the city arrived with a car full of armed men. During this period, no one in Centerville had awakened to the fact that anything was wrong at the bank. John felt the breath of cool, fresh air, and strong hands lifting him. He was too dazed to pay attention to what was going on, and submitted when medicine were put down his throat. He was in bed for two days before he could get about properly.

ON the morning of the third day his uncle came into the room. A burly man walked on each side of him. In fact, his uncle hardly walked; he was principally supported and pushed forward. Behind them came Dorothy; darting around in front of them, she had hold of John's hands.

"Johnny-on-the-spot!" she laughed, and kissed him in front of all the others, thereby embarrassing him tremendously.

But John had not missed the look of anxious concern on her face for an instant when she first came into the room, and before a quick glance told her that he was in good shape. He was grateful to Providence for her.

His uncle shuffled up to the bed.

"You're fired!" he attempted his quondam roar, rather anticlimatically. He looked very much used up.

"Tush! tush!" one of the big men said. "We can't fire that boy. We still need him." He was softly sarcastic about it.

John looked at them closely. They were certainly not the furtive creatures who had come into the bank that forenoon with Jake Bloor. In fact, he could see the edges of shiny badges peeping out from under their coats. It was only too obvious that Jake Bloor was under heavy arrest.

"But what I want to know," one of these big, official-looking men was saying, "is how you set off your stuff? This guy says he had you covered and that he cut your wires and pulled a section out of it."

John laughed heartily and long.

"My uncle is clever," he said, when he could finally speak; "but he missed a slight, though important, fact. That wire supplied a current from a storage battery, and as long as that current kept running, everything was peaceful. It was the breaking of the current, either by shutting off the light to the photo-electric cells by hands up, or merely by cutting the wire, that set off the relay and turned on the tricks."

"Oh-h-h!" said Jake Bloor faintly.

"I tried to tell you " John began.

"Never mind," one of the big men said. "We'll tell him. But now we want you to come to the bank."

John dressed and went to the bank, where he again found his uncle and the two men. These two showed a persistent fondness for close proximity to his uncle; they would never permit him to move more than a few inches from their sight. There were also two smaller men going over the books.

"As I thought," said one of the latter. "Flat failure!"

One of the big men shook Jake.

"So you had the balloon punctured, and were ready to skip," he said quietly. "That won't sound good to the judge. Well, anyway, there's enough cash in your bag to pay off your depositors with— unless we have to divide it among those of the other banks he has robbed around here."

"Robbery and embezzlement both," said the other deputy. "That'll be about a hundred years at Leavenworth."

He turned to John.

"You will be required for a witness, so stay where we can reach you. I understand that the loss of this job is tough luck for you. Well, here's hoping you have no trouble finding another."

They all went out, bundling Jake Bloor with them. John and Dorothy were left alone in the bank.

With startling suddenness, the telephone rang shrilly. It was long-distance calling from the city.

"Are you the young man who devised the apparatus that caught the robbers in this bank? This is the Palisade Insurance Company, and we need somebody like you on our staff. Can you came into the office and discuss the details of your position? Thank you."

John and Dorothy looked into each other's eyes. That home of dreams was becoming a reality at last.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.