RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

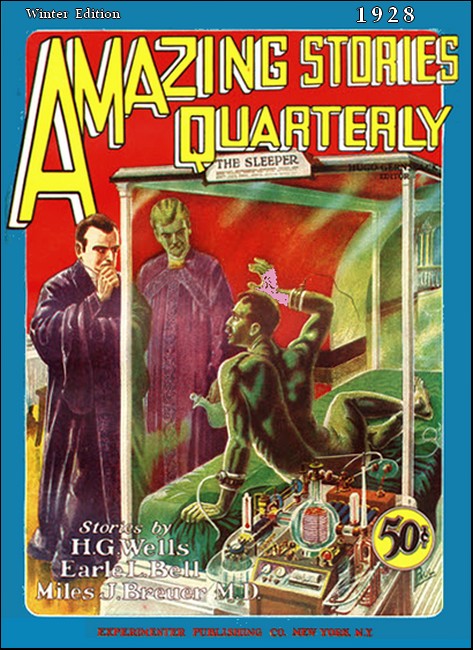

Amazing Stories Quarterly, Winter 1928 with "The Puzzle Duel"

"I'll get you somehow..." my thoughts began and suddenly

stopped. Right before my eyes he dropped like a slaughtered ox.

DURING the years just preceding the World War, our supposedly homogeneous country contained numerous undercurrents of race-hatred. I had an exceptional opportunity to observe them, for I was a student at the University of Chicago, that teeming meeting-place of youthful brilliance from all the ends of the earth. It was fascinating to mingle in class with them—Japanese from their Pacific Island, Balkans from their wild borderland, Latins from the vastness of South America, Englishmen from the Cape, fair-haired Nordics from the Scandinavian countries—all young and all gathered together to learn about the world and how to run it.

All these children of different climes were so interesting to me that I cultivated personal friendships with many of them, and finally chose as my room-mate a young Hindu by the name of Raputra Avedian. I became very much attached to this intelligent chap, who was qualifying himself to teach at the University of Calcutta. His work was in physics—chiefly electrical theory. The longer I knew him, the better I liked him for his quiet and dignified modesty coupled with profound learning and brilliant ability. Despite his dark skin and his strange white headdress, he seemed more like a brother to me than did my fellow-students from my home town in Iowa.

Therefore the incident in the library came as a severe shock to me; a shock both because of my affection for my friend, and because of the startling difference in the workings of the foreign mind from our own American ideas. Raputra had been standing near the door, talking to a short, heavy-set man with a red face and a plateau of blond hair. Though not personally acquainted with him, I knew who he was: Schleicher, a graduate of the University of Heidelberg in Germany, and doing post-graduate work in physiological chemistry at the University of Chicago. What little I knew of him was unsavory; he had a reputation of being personally difficult to get along with. Right now he seemed to be living up to that reputation. Though I could not hear anything that was said, the sneering expression and the contemptuous snarls of the man were irritating even to a disinterested spectator at a distance. Suddenly Raputra drew himself up to the full height of his tall figure and deliberately slapped the German across the mouth.

The sharp sound of it made me sit upright in my chair. The white mark of the Hindu's fingers showed against the red of Schleicher's face, which grew redder until his downy mustache stood out white against it. He kept puffing up till I was afraid he might explode. When he was nearly purple, he caught himself up with a gulp; his lower jaw worked up and down and he fumbled in his vest pocket. He drew out a card, handed it to my friend, turned on his heel, and walked away. I had read enough about duelling customs in German universities to know what that meant. Raputra turned and looked at me. His face was calm as I came toward him.

"Peters," he said evenly, "will you assist me in this affair?" I stood for a moment not knowing what to say.

"I might endure personal insult," he explained, "but no Indian gentleman will listen to national calumny."

He gave me the German's card and walked out of the building. There was only one other student in the library. When I had recovered from my daze, he was coming toward

"Jerry Stoner," he introduced himself succinctly. "As I understand it, these birds want a duel. Schleicher said to me: 'Only his life will satisfy me!'"

"I'm not very strong for this stuff," I said.

"And what's more," replied Jerry Stoner, "the police aren't either."

"Yet these benighted foreigners consider us under obligation to arrange a fight between them," I reflected aloud.

"What we ought to do," Jerry Stoner said vehemently, "is to get them out behind the wall of Stagg Field with their coats off and a couple of pairs of eight-ounce gloves. But their minds don't run that way; I know them too well."

"We'll have to fix up some sort of an arrangement that will satisfy their pride and do them no harm," I continued. "I've got an idea. Both of them are clever scientists-"

"Each of them is hungering for the other's life," Jerry Stoner interrupted me.

"Look here!" I drew my chair up to his. "Let's have them fight a modern, scientific duel. Science for weapons! The real fight will be a battle of wits to devise a secret, silent blow. The victims will not know when or how it is to fall. The one who deals it will not be on the scene to be connected with it. To the public it will seem like a natural death or an accident."

"Sounds all right," Jerry Stoner laughed skeptically. "I doubt if they can hurt each other much, if they stick to the rules of that."

"That's what we want, isn't it? Both are well equipped for such a contest. It will keep them busy for a while. Then, in the press of daily work, they will forget it. I can't imagine any man, who is really busy, letting a little falling-out like this upset him for very long."

Raputra Avedian was delighted with the plan when I outlined it to him. Something about the subtlety of it appealed to his Oriental mind and it also satisfied his scientific nature. He thanked me as profusely as though I had done him a tremendous favor, and for some days afterwards was silent and happy.

He was missing all of one night and I became worried lest he had met with some disaster; but he turned up in the morning, grimy and fatigued as though he had been at some sort of hard labor, but he seemed cheerful and enthusiastic.

He seemed to be taking something very seriously; but I forbore questioning him about it. I could see that he was not neglecting the defensive, although I did not know what his plan of attack was. He assembled a pocket first-aid kit containing all manner of emergency measures, antidotes, stimulants, antitoxins, stomach pump, purgatives, and emetics. He ate only at the Commons, of the same food with hundreds of other students, and never went anywhere but to his laboratory and to our room at the dormitory, always within view of numerous people and always watching about himself carefully. He was as unapproachable as a royal personage. I regarded his danger as an exaggerated fancy.

The blow came all the more, therefore, as a shocking surprise. The suddenness of it, the mystery of it, left me stunned and paralyzed.

ONE Sunday morning I remained in bed for a few minutes after Raputra had risen and gone into our little bathroom. I could hear him stropping his razor and washing his face. Then there was a heavy thud and a rapid knocking which gradually died down. I leaped up and ran in. Raputra lay on the floor, still moving feebly, but already stiffening in death. He had got his emergency kit open and one hand jerked it about, spilling the contents about the room. It jerked back and forth feebly once, and then he lay still.

I grew so suddenly weak that I had to sit down on the floor for a moment before I could look around. Then I searched carefully. Nowhere on Raputra or about the room were there, any signs of violence or of anything unusual.

How had it happened?

The wonder of it occupied my mind for a moment then I caught sight of the wet toothbrush at the foot of the lavatory; the pitiful little subject told me that my friend had been stricken while brushing his teeth, and a rush of grief drove all the detective impulses out of my mind. Poor Raputra! All his brilliant fire and his vast promise were nothing now! Again my mind returned to the mystery. The only window in the room was closed and locked on the inside. Outside, five stories of smooth, gray brick wall stretched down to the ground, with a feeble wisp of ivy here and there. There was no exit save through our sleeping room; this had one door into the corridor, locked on the inside. No one could have gotten in or out unobserved. What a foolish idea! Of course no one had gotten in or out. This was the secret, scientific death, and Schleicher had done it.

All at once it came to me that a sudden death of this sort would have to come before a coroner's jury. I decided that I had better leave everything undisturbed for more skilled investigators than I was. I called the police and waited.

I will not go into detail about the miserable days that followed. The post-mortem examination that took two doctors and two assistants six hours, the analyses for poisons, the minute study of our room and bathroom, the minute questioning and re-questioning of myself and all persons in our end of the dormitory, failed to reveal the least suggestion of a possible cause of death.

Not a sign, not a clue, not a mark!

It looked as though he had been struck dead by magic, and the case promised to remain a medical mystery. No less a personage than Doctor Victor LeCount was involved in the investigation. This man, the author of a book on sudden death and its causes, and the world's foremost authority on that subject, had been retained by the insurance company in which Raputra had recently taken a policy; for the presence of the emergency kit had stirred the company's suspicions. However, even this great man could offer no suggestions. So, the death certificate was made out as "sudden death, cause unknown," a burial permit issued, and the insurance paid to Raputra's brother.

Of course, Jerry Stoner and I had kept quiet in regard to the duel. My first impulse was to stand up and accuse Schleicher. But reflection quickly showed me that such a course would not only be futile, but dangerous to both of us. It would sound so improbable that everyone would doubt its truth and no proof of any kind could be produced. On the other hand, we would only lay ourselves open to blame for complicity in the death.

So my friend was buried. The world seemed strangely blank and gray to me. I had not known that a mere roommate could mean so much in one's life. My mind was in a whirl of torment, for in the background of my mind was the guilty feeling that I was to blame. My own brain had contrived the devilish idea. It had never occurred to me that my friend might be the victim. My mind was filled with resentment against the German. Surely the justice that in the movies always overtakes the wicked, was lacking in the real world. Why had the possibility not occurred to me that the overbearing Prussian might not get his just dues?

The more I thought about it, the more my resentment rose against the cruel turn of fate, and against Schleicher himself. He had murdered my friend! I determined to ascertain how, to prove it, and to prosecute him. If I could thus avenge my friend, I could at least justify myself in my own eyes for the regrettable part I had played in the affair. It could not bring my friend back, but it might wipe out my guilty feeling. I thought about it constantly, alternating between the depression of self-censure and the efforts of solving the mystery. I was quite unable to attend to my class work. The problem interfered with my sleep and appetite.

FINALLY, I went to LeCount. My regular course would bring me under his instruction the following year, and I had no hesitation in seeking his acquaintance.

He was short and rotund, with a fat, grey mustache. His students looked up to him with awe because of his learning and with fear because of his snappy manners. I found him at a microscope in the Pathology Laboratory. He was not much of a conversationalist; when I tried to explain why I had come, he jerked out:

"Tell me all of it this time!" That embarrassed me from the beginning; evidently he referred to my testimony before the coroner's jury, and in some uncanny way knew that I had withheld some information. Then he sat motionless, without the quiver of a muscle all the time I was telling the story. After I had finished, he continued to stare at me until I thought I would go frantic. Finally I had to speak:

"Do you think Schleicher killed him?" I asked.

"Of course he did!"

"In God's name, how?"

"I don't know." That was all. He looked at me inscrutably. I did not know what to do or say. His eyes were fixed on me until I began to think I had done it myself. "Possible, all right," he finally snapped. "Now go over all the details of that Sunday morning." As I talked, he interrupted me frequently: "Did he take a drink every morning?"

"Did he ever cut himself with his razor?"

"The toothbrush! Ah, the toothbrush!"

"The dormitory is familiar to me," he mused as I concluded. "It is possible for someone to get into your rooms during your absence, is it not?"

"Yes, but—"

"There is only one explanation possible. Your history eliminates every other. Some sort of poison—"

"But none was found in the post-mortem analyses—"

He looked at me sternly for interrupting, and then went on as though I should have known better: "Here are some poisons that leave no trace perceptible to the analyst." He pointed to a chapter in his own book on toxicology, and continued: "Aconitine kills in doses too small to leave any detectable traces. Rattlesnake or cobra venom, if introduced directly into the circulation, that is, not through the stomach, also kills without leaving any traces for the analyst. Finally, Vaughan's split-protein products have much the same effect as the snake venoms."

He regarded me steadily for a while and then thrust "Now do you have an idea how he met his death?"

"Of course, the poisons are a possibility," I pondered. "But how were they administered? There are no marks of needles—"

"Think some more. Perhaps you can recall if there was a spot of blood on the toothbrush?"

"Yes. Almost everyone's gums bleed occasionally during the brushing of the teeth. Raputra was more susceptible to bleeding than I."

"Well? Did Schleicher know that?"

"He might have."

I could not make out what he was driving at.

"All right. We can probably eliminate the aconitine. Death by that is slower than this man's was, and does not produce the convulsion that seemed to be present in this case. But either snake-venom or split-protein placed on the toothbrush Saturday night when both of you were out celebrating the football victory, would introduce enough poison directly into the bloodstream to have caused just such a death. Where's the toothbrush?"

"In the room. I don't think it has been touched since that morning."

In response to his curt nod, I bolted out and was back with the toothbrush in twenty minutes.

By the time I returned, he had two guinea-pigs ready. He first injected one with some physiological salt solution.

"That is the control," he said; "just to prove that the salt solution is pure and harmless."

The guinea-pig was quite unconcerned after its experience. Then Dr. LeCount soaked the toothbrush for a few minutes in a test-tube half full of the salt solution, and injected a syringeful of that into the second pig. He hardly had time to remove the needle; the animal shivered, kicked convulsively several times and was dead.

"Of course, I can't tell you whether it is rattlesnake or cobra; it might be split-protein. But, is that proof?"

The doctor fixed his wide, blue eyes on me again.

"That's proof enough!" I exclaimed. "I'm going straight to the District Attorney's office. I'll get Schleicher yet."

Dr. LeCount smiled. That was a rare thing. It meant something. "The District Attorney's office does not close until four o'clock. It is now eleven," he said deliberately. "Wait a while."

So I waited, while he studied me. I felt like a germ on a slide.

"In the first place," he began in his favorite phrase, "scientific proof is not legal proof. This sort of evidence wouldn't convict anybody. My work is the study of disease, not of law; but I get mixed up with law often enough to know that you can never get a case against that man. You may prove it morally and scientifically, but not legally.

"Secondly," he eyed me fixedly, "for a scientific man, you are inconsistent. You'll have to reason more rigidly than that if you want to pass my class next year. These two men stepped out of the bounds of the law when they arranged their duel. Now all parties concerned should be satisfied. To invoke the law now is childish in the eyes of a fair man.

"Finally, what about the part you played in it? You should have thought of this possibility when you planned the duel. Now you are apt to get into trouble as an accomplice."

I left his presence humble, but not subdued. The desire for revenge is a shamefully primeval impulse; it is so powerful, that its suppression causes even civilized men considerable difficulty. As I walked down the street, I shook my fists in the air, vowing that I would get Schleicher somehow. Involuntarily my footsteps carried me toward Schleicher's residence. For—and it doubled my resentment—Schleicher was evidently independently wealthy; at least he spent money as though he were. He never got sufficiently accustomed to Chicago's ways to live in a flat or an apartment. He occupied one of the cottages in the row opposite Washington Park, and had a flower garden in his front yard. Gardening was his hobby. Then I recollected that he had not been seen since the day of the challenge. Was it guilt that kept him in concealment? The report had gone about his laboratory that he was confined to his home by sickness. I strode quickly toward his house.

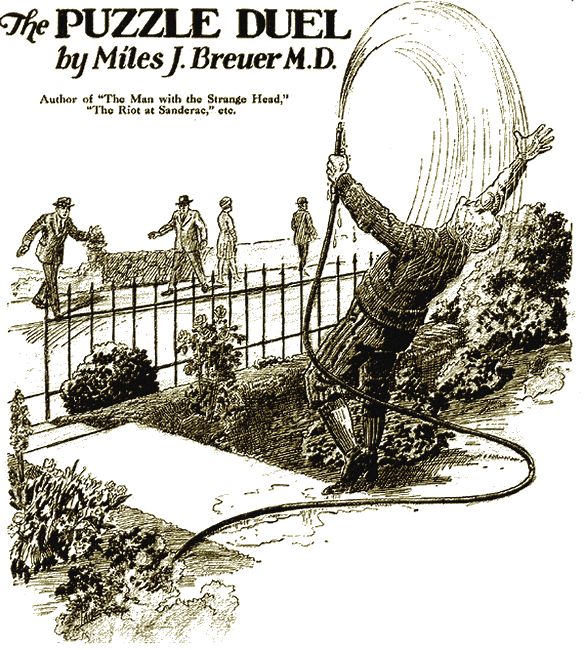

There he was now in his garden, sprinkling with a hose. If he had been sick, he must have just recovered, for it was his first appearance. I walked slowly past on the opposite side of the street. He stood stiffly, holding his red face arrogantly above the rest of humanity, and moving the stream of water from his hose with military precision. He didn't even see me. I execrated him; I almost shook my fist at him. I wondered what to do next.

"I'll get you somehow—" my thoughts began, and suddenly stopped. Schleicher had toppled over and lay flat on the ground. He had been standing in his stiff, military attitude, spraying the hose this way and that on the flowers and shrubbery. Then right before my eyes he dropped like a slaughtered ox. Now he lay still and the hose spurted over him in an arch where it had fallen out of his hand. I reached him first though a number of people also came running up. His heart seemed to flutter a little, but as I felt of it, it stopped still. Half a dozen people gathered before I had him looked over. He was undoubtedly dead. Nowhere on him was there a scratch or a mark of any kind.

Another sudden death! Another secret, silent, scientific blow! This time the mystery of it elated me. I left the others crowding around the body, while I eagerly looked the surroundings over carefully, behind the fence, under the porch, through the shrubbery, hoping that I might find a clue to the method.

Then, a gleam of metal, hidden in the shrubbery, caused me to halt and stagger back. I had caught myself just in time to prevent my hand from touching it. There was an insulated copper plate concealed in the bush. From it ran a cable which I quickly traced toward the Jackson Park Elevated Railway.

The whole scheme was clear to me now. I understood the meaning of the coil of cable and the bag of tools that Raputra had carried out of our room with him on the night that he had spent out. The plate in the bush was connected with the third rail of the elevated railway, and when the water from Schleicher's hose struck it, the powerful current that ran the trains overhead had electrocuted him on the spot.

The crowd about the body increased. The distant clanging of an ambulance swelled rapidly. I stood off from the crowd and reflected. Things seemed to balance now. Appropriately, by the hand of a man several days in his grave, movie-justice had been done.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.