RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Amazing Stories, December 1927 with "The Riot at Sanderac"

THE courts have started their slow, blundering grind at Sanderac. First there came the newspaper headlines screaming the shocking news over the country. The next day the columns went into details concerning the unaccountable outbreak of rioting in the little mining city. Nearly two hundred dead, buildings burned, property destroyed, and no one knew the cause. The nation stood aghast, because the perpetrators of the ferocious massacre were those who had until then been solid and respectable citizens.

I happened to have been there when it occurred. I told my story. I was scoffed at and received no attention. The courts continue to grope ineffectually about in circles. How futile they seem!

The town is built about the mine head. Its population is about half American, half foreign labor. Among the latter is a colony of Russian refugees, largely Marxian Communists, or as we know them, Soviet Bolsheviks. Their meetings were watched by the police, and some vague, ridiculous rumors started that they planned organizing a Soviet right there on Lake Superior. But no one took it seriously. On the whole, the Bolsheviks lived harmoniously with the five thousand Americans. Even the refugees belonging to the Russian aristocracy and intelligentsia got along very well with the Reds. Such is the leveling influence of Americanism.

I was visiting an engineer friend of mine at Sanderac. This was my first visit to Grant since our college days at the "Boston Tech." He had gone straight to the mine job, while I had a government position which took me all over the country. I still remembered Grant as a fellow of uncanny ingenuity as well as ridiculous absent-mindedness. He was—overjoyed to see me, made me put up at his home, and took me all over the town—the town which has now become so famous.

"I have often wondered," I said to him at dinner, "why as brilliant a man as you are, is willing to bury himself here out of sight. I looked forward to your accomplishing some sensational thing in the world."

"Well, you may not be so far wrong at that," Grant said with a smile that seemed to indicate he wasn't telling everything. "This is an ideal position for me: not much work, lots of leisure, plenty of money. I'm working on things of my own, you see!"

I knew then that he had some sensational plan worked out. From that moment on, I gave him no rest until he had started out to tell me about it. I hurried myself and him through the rest of the meal. Grant took me out to a concrete shack near his building at the mine works. It was heavily locked. Within was a workshop.

From the looks of the tools and the small parts, it was evident that he was working on some delicate electrical stuff. A smooth-shaven, sad-looking man of about fifty, bent over a bench, was working on some things strung full of green-insulated wires.

"This is Sergei, my assistant," Grant said, introducing me. Sergei's face showed refinement and intelligence. His courtesy was of the European type, which Americans so admire but cannot imitate. He moved away to turn on more lights.

"Queer fellow," Grant said in an undertone. "He won't even associate with the other Russians. Used to be a musician. The Bolsheviks killed all his family."

For a moment I was more interested in the Russian than in the machine, but he was now bent over a table, studying a blue-print and putting pieces together. There was a sort of hopeless droop about him; yet he worked swiftly and with marvelous skill.

"Here we are!" explained Grant. "This is what I've spent the last ten years on."

"What's it supposed to be?" I inquired. "It doesn't suggest a thing to my mind."

There was a semi-circular keyboard, like those on large pipe-organs. The rest of it was built up into a sort of a cabinet, with bulbs, instead of organ pipes. It was something like an exaggerated and caricatured radio sending set. There were scores of the bulbs, globular, pear-shaped, gourd-like, flask-shaped, and of all sizes from that of an egg to one as big as a pumpkin.

Grant moved a switch. The complex array of bulbs filled with a pale white glow.

"They look as though they might be electron-tubes," I remarked, "Is it some form of musical instrument?"

"No. Not exactly. Sit down." Grant was elated.

So, while I found a chair, he took his place on the bench in front of the organ thing. He ran his fingers around over the keys. I stared at him in surprise. Not a sound came from the instrument. Was it some effect of light or color that I should look for? I looked closely, but the bulbs glowed quite unchanged. Was he out of his mind? Not knowing what else to do, I sat and waited patiently.

I sat bowed forward with my chin leaned on my hand and my elbows on my knees. Grant's movements at the silent machine became monotonous and depressing. The dingy, concrete walls were unutterably gray. The gloomy interior of the shack made me think of some graveyard of human desires. Even the futile wires sprawled all about, gave a mournful impression. I grew so lonesome and discouraged that I could feel the muscles of my face droop and sag. Grant, failure of a fellow that he was, seemed somehow ragged and dismal as he lugubriously pawed the keys. I watched the heavy smoke drag across the square of leaden sky visible through the window, in the same way that my useless soul was drifting across a colorless and dreary world. The only place for me was at home with my mother; my mother of the white apron and sunny hair, who made gingersnaps for me. But my mother was dead.

Grant stopped his activity at the keys and turned around. He looked at me intently for a long time. Then he turned around and started playing again on that dumb, futile keyboard. He danced around on his seat like a clown; like a travesty of Paderewski. He crooked his fingers into claws and brought them down wildly on the keys, and then ran them through his ruffled hair. His knees worked comically up and down as he manipulated some sort of pedals. He looked so silly that I was forced to smile. Then I leaned back and laughed. I laughed at him, and at the funny little zig-zag wires on the bench near me, like wiggling rat's tails, and at the comical shapes assumed by the wisps of smoke outside the foolish little window. The back of Sergei bent over his work was like a hump on the back of some droll camel; it made me laugh till I rocked. The whole adventure up on the mountainside with a coal-mine below and a cracked inventor pounding on an organ that wouldn't work, was all so inexpressibly funny that I laughed till I was hoarse.

GRANT was sitting motionless again, gazing fixedly at me. As my laughing died down, he turned again to the keys.

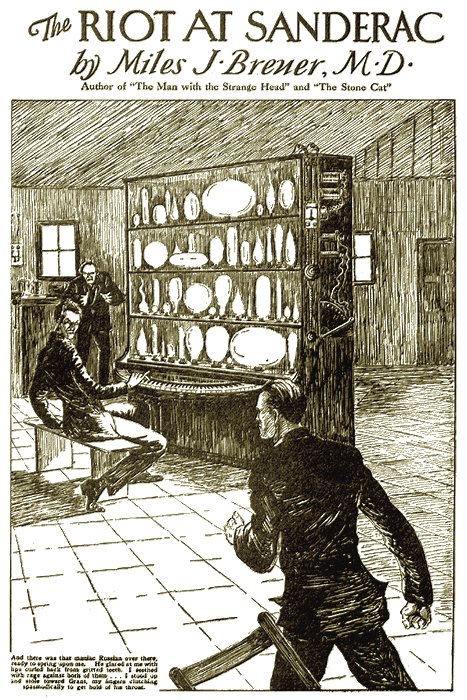

He played slowly, if I could call it playing, since I heard nothing. The crazy fellow, trying to deceive me that way! I grew impatient at him. Did he think I was a fool? I had a strong notion to tell him what I thought of him and his abortive invention. His slowness was irritating. I knew he was doing it to tantalize me. I felt like giving him a shove and knocking him off the seat—and kicking him into a corner. My lists clenched and my biceps tightened. Why had he brought me into this barred and locked stone cell, full of poisons and dangerous currents? And there was that maniac Russian over there, ready to spring upon me and kill me unawares! The coward! I looked at him. He straightened up and glared at me with lips curled hack from gritted teeth. I seethed with rage against both of them. I've got to get them both out of my way before I can escape. Grant first. I stood up and stole toward him, my fingers clutching spasmodically to get hold of his throat. I wanted to maul him, to break his bones.

He whirled around and saw me. His hand shot out and moved a switch. The glow in the bulbs died out. A sudden limpness went through me; my knees went weak and I collapsed on the floor. Now everything was peace. I was myself again, wondering what had been happening to me.

Slowly it dawned on me that Grant's "playing" must have had something to do with these storms of emotion.

I sat up. Sergei was sitting in a chair, pale and clutching a bench.

"That last effect was foolish of me." Grant was saying. "You might have beaten me up before I realised what was happening. My own fault."

I stood up, feeling much better physically. Grant was again the same old good-natured, absent-minded scientific child. Sergei also walked away in deferent silence. He didn't look fierce at all, only humble and quiet, and very much a gentleman. Think of it, a concert musician now at a menial job. And a wife and two girls murdered by Bolsheviks!

"Narrow escape, I had," Grant laughed again, as I stared around, unable to find words. "And poor old Sergei was on his way out to clean up his Bolshevik neighbors!"

"What's this?" I finally demanded. "What's been happening to me?"

"You will admit that it affected you powerfully?" Grant smiled.

"I'll say it did! It nearly drove me crazy. What is it? How is it done? Tell me quick, or I'll get you yet!"

"When I explain," Grant warned, "you will be disappointed at the simplicity of it."

"I'm waiting to be."

"You know well," he began, "that emotions are purely physical states, produced by the activity of the ductless or endocrine glands. Stimulation of the suprarenal produces rage; that of the thyroid, fear and anxiety; that of the gonads, love, and so forth. Warm up the gland, increase the amount of its secretion, and the emotion follows. By mixtures and combinations, an endless chain of emotions may he produced. That is well established knowledge."

"Old stuff!" I agreed.

"The next step is that the operation of the body cells is merely a matter of the exchange of electrical charges. Secretion, nerve action, muscle contraction, ail you do, is merely a movement of electrons from here to there."

"Nothing new or startling about that so far," I commented.

"The rest isn't so old. I figured that instead of waiting till the exchange of electrons in the body takes place by chance impulse and accidental combinations of perceptive stimulation. I would make them for you at will, by shooting electrons at you out of my vacuum tubes. The numbers, velocities, and quantity-rates of discharge of negative electrons, and various varieties of positive ions, determine whether it is your suprarenal or your pituitary that is warmed up. Your body obeys; can't help itself."

"It is simple," I admitted. "But it is uncanny. I certainly felt real emotions."

"They were real emotions. And I had a real one, too, when I saw you coming—I was scared!"

I sat down to think over the astounding thing. He had sat up there and played on keys, and made me feel as I did. And since feeling controls action—that man had an instrument that could make people do anything. He had the world at his beck.

"You just got here in time," he was saying in a most matter-of-fact voice. "We were about to begin taking the machine apart and moving it to a theater. I want to give a public performance."

In fact, Sergei was already taking out the electron tubes and packing them in cotton-lined cartons.

"I'd like to see that," I said eagerly, my mind full of interesting possibilities. "When does it come off?"

"By all means come. That will be an excuse for you to remain with me for a few days. I am planning the show for next Friday. Sergei can almost handle the moving alone, so you and I can have lots of time together, for my work at the mine is light."

GRANT'S advertising for his public performance was very modest. I was afraid that he would not have much of an audience. He announced in the newspaper and on billboards that he had a scientific discovery for influencing emotions in a new way, without the medium of pictures, music, words, or other common means; something different. He told me that he did not care to have a big crowd for the first performance.

But the house was packed full. Grant's towns-people apparently knew him, and expected something worth while. The buzz of excitement through the theater swelled and waned in rhythmic waves as the people sat and looked at the organ keys and the assortment of odd-shaped bulbs. The theater was full; people continued to crowd in, and there were more people outside. And still Grant had not arrived.

He had tested out the machine in the afternoon and had waited eagerly for the evening. Then, at 7:30 P.M., he had been called to the power-house at the mine, where a safety-valve of a loaded boiler had jammed. Now it was 8:15, and the densely packed audience shuffled impatiently and broke out into occasional bursts of clapping to encourage themselves. At 8:23 a messenger arrived from Grant with a note. Sergei, who had been hovering anxiously about the machine, took it, glanced at it, and handed it to me. The note was addressed to me.

### LETTER

"Bad job here," it read. "I don't know whom else to ask, and therefore I should like to have you get up and explain to the audience what the situation is. Tell them that I shall be back in an hour. They may go out, and return in an hour if they wish. Grant."

Facing an audience has always been unpleasant to me, even for such a trifling matter as this. It took me some minutes to screw up my courage, but eventually I was in front of them.

The people looked queer. Their eyes were big and glaring. They sat up rigid. Everyone's teeth showed in an ugly snarl. Here were the town's best people, business and professional men whom I had previously met; well dressed women; as good a group as one could see in any city. But now they looked like some savage beasts.

Then, suddenly I understood. A glance backward had shown me Sergei seated at the keys, his body swaying, his fingers busy, every inch a musician. I gave one more terrified glance at the audience. Peoples' arms jerked convulsively. One by one they were leaping fiercely to their feet and surging forward. I was desperately afraid for my own safety, and I turned and fled across the stage and out of the rear door. I ran—something I was not accustomed to do. I puffed and my head throbbed. I ran for the powerhouse where Grant was working on the jammed safety valve. An overloaded boiler was less dangerous than this fiercely aroused audience. The uproar of shouting and trampling behind me, lent speed to my clumsy progress.

I began to feel relieved when I saw the boiler-house in front of me. Why I do not know, for what could Grant do? Then, the boiler house acted queerly. It bulged outwards. The tall chimney stack bent in the middle like a knee, and seemed to hang that way for an interminably long time. There was a great spout of steam, and a terrible boom that reverberated and roared for several minutes. Before me was a vast cloud of steam, out of which black objects flew high in all directions. Some of them seemed to be men. I stopped. Behind me the clamor of shouting and trampling was increasing. I looked back and saw names shooting high in the air from the theater building. A mob of infuriated people was running, surging, pouring through the streets, brandishing things. Terror possessed me. Which way should I run?

However, I soon noted that they were not after me. They turned and flowed to my left, toward the mountainside. I stared at them, amazed, for a while. In the mean time, shots and screams and hideous thuds came from the section on the mountain slope where the Russian miners lived. Flames shot up here and there. The attack had fallen on the Bolshevik quarter, which was being swiftly wiped out.

For a moment I stood frozen in my tracks. Then I dragged myself to the garage where I kept my car. I dashed out of that place in the twilight, without a hat, without my baggage—without my mind, almost.

Now, the courts are foolishly, blunderingly groping around, trying to fix the blame. They have scores of citizens in prison—perfectly innocent citizens. I tried to tell them of Grant's instrument, and of Sergei who was a musician and whose wife and daughters were horribly murdered by Bolsheviks.

But I was only told that I had not been called as a witness, and if my testimony was required, I would be notified.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.