RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

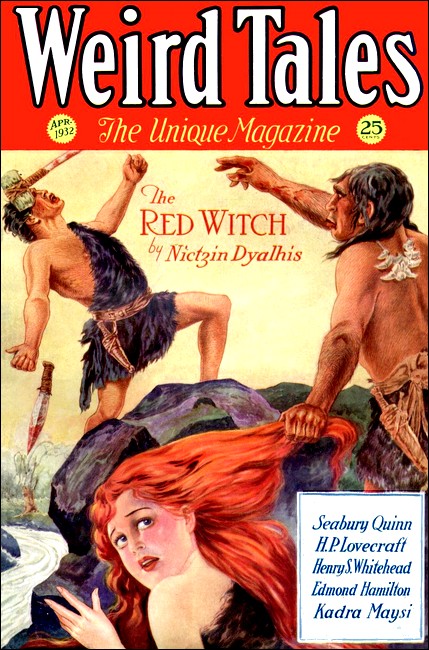

Weird Tales, April 1932, with "Midnight Madness"

A blow in the night, a man thrown overboard—by these means Carl Van Doorn mistakenly thought to secure happiness for himself...

TWO men sat idly smoking on the rear deck of the yacht Doris. Neither had spoken for fully twenty minutes, for both were busy with their thoughts.

For three years, both had been suitors for the hand of Doris Page. Clayton Raeburn had won, despite the fact that Carl Van Doorn was immensely wealthy while he depended on a salary. Van Doorn, however, had shown himself a game loser by promptly inviting the happy couple to cruise with him to the Bermudas in the yacht he had named for the girl whom both men loved. He had been a most congenial and companionable host, and Clayton's thoughts at length resolved themselves into spoken words.

"It's been awfully good of you, Carl," he said, "inviting us on this trip, I mean, and treating us as guests of honor after—after—"

"Don't mention it, old top," Van Doorn interrupted cordially. "It has been the greatest pleasure of my life."

His face, calm and smiling in the moonlight, gave no more hint of the raging storm within his bosom than did the even, pleasant tones of his voice. Van Doorn would have made a great actor.

Raeburn rose, walked to the stem rail and tossed his glowing cigar into the water. Far off to the port side he saw a dark fringe of palm trees silhouetted against the sky, and below them a curved, silvery outline: the white, sandy beach of a tropical islet.

"A veritable fairyland," he exclaimed. "It's bedtime, but I feel—"

The sentence was never finished. Something struck him a terrific blow on the head, his knees sagged, and he sank to the deck unconscious.

Van Doorn cast a quick, sly glance about the ship. All his guests had retired. Officers and men had gone below, with the exception of the helmsman, whose voice, dimly audible above the throbbing drone of the engines and the churn of the propeller, was raised in a rollicking sailors' chanty as he stood at the wheel, his eyes on the moon-silvered waves ahead. Quickly tossing his blackjack away, he picked up the huddled, inert form of Raeburn and heaved it over the rail. For a moment he saw the flash of a white face disappearing beneath the foaming water—and shuddered. The ship's bell tolled the hour of midnight as he turned away from the rail with a shrug of his shoulders, calmly lighted a cigarette, and walked to his cabin on soundless, rubber-soled shoes, his actor face a study in tranquillity.

THE Page-Van Doorn wedding was a gorgeous affair. As Doris and her husband mounted the steps of the Pullman that was to convey them to the country home in which they had decided to spend their honeymoon, a cheering group of friends waved gay farewells and wished them happiness.

Van Doorn found his bride strangely reticent after they were settled in their compartment. He made several unsuccessful attempts at conversation, then lapsed into moody silence, wondering what had come over her so suddenly. She had been cheerful and vivacious up to the moment when they boarded the train. Could it be that she had guessed? But, no. That was impossible.

Doris had guessed nothing, suspected nothing. The affair on the yacht had been too well planned and too skilfully executed for that. Raeburn had disappeared during the night. That was all any one knew. Van Doorn told his story in so plausible and straightforward a manner, how he had left his friend standing near the rail at midnight and gone to his cabin alone, that every one believed him without question. It was decided that Doris' fiancé had either leaped or fallen overboard when there was no one around to see. She was thinking of a shattered dream of love—a cherished vision that had faded with the disappearance of her lover.

Carl Van Doorn had been good to her during their return from the Bermudas and throughout the long, dreary year that had intervened between the finish of that trip and their wedding. His show of sympathy and his evidently sincere grief at the loss of his friend had won her regard. For months he had dropped no hint of love or marriage, waiting with patience born of a subtle understanding of the minds of women. At the psychological moment he had spoken, and she had capitulated—with reservations.

"I do not—can not—love you, Carl," she had said, sadly. "You know that all my love was Clayton's and will be to the end of time. I suppose I must marry some one, though, so if you want me you must take me as I am."

"I will teach you to love anew," he had exclaimed as he took her in his arms and rained kisses on her unresponsive lips.

All these memories returned to her as she looked out on the swiftly moving landscape, and she wondered why she had married Carl Van Doorn. Even the touch of his hand on hers sent a feeling of loathing through her entire being.

WHEN they arrived at the station Van Doorn's worries were multiplied. His chauffeur had sent word that the car in which he had intended to meet them had been damaged in a collision and was out of commission. Then there was trouble about the baggage. His wife's trunk, containing her trousseau, was missing and could not be located, either in the baggage cars or the station. After twenty minutes spent in the telegraph office he learned that the trunk had been left behind but would be forwarded on the next train.

On his return to the waiting-room he found Doris talking to a ragged derelict who wore blue glasses that announced his affliction and carried a tray of cheap pencils.

"Come," he said, a bit petulantly. "We must take a taxi. Your trunk will be along at six this evening and I have arranged to have it delivered to the house immediately." He noticed, with surprise, that there were tears in her eyes and she seemed unusually pale. "Why, what's the matter?" he asked apprehensively. "What has this tramp said to you?"

"Oh, I am so sorry for him," she murmured. "Think of the horror of a lifetime spent in darkness."

Van Doorn extracted a roll of bills from his pocket, tossed one carelessly on the tray and hurried her out the door and into the waiting taxicab. She was trembling and tearful as they drove through the streets of the village and thence along the dusty road which led to the estate of her husband.

"You are too tender-hearted, dear," he said gently. "Don't let the story of this blind man spoil the first day of our honeymoon. There are thousands of blind men in the world with stories just as sad."

"Be patient with me, Girl, and I promise you I shall be myself presently," she replied bravely, winking away the tears.

Soon they turned into a delightful driveway which curved through artistically massed flowers and shrubbery, and drew up before a well-executed reproduction of an English country house.

They spent the afternoon roaming about the spacious grounds, and Van Doorn was pleased by the fact that Doris had regained her accustomed vivacity. Her usual sparkling wit was in evidence at their tête-à-tête dinner. Afterward, in the music room, she played the piano and sang for him in her full, sweet contralto. He seized her hands as she rose, a world of passion in his eyes.

"You are wonderful, adorable, Doris," he exclaimed, pressing her hands to his lips.

"I am tired after our journey and—and everything," she murmured.

Suddenly he crushed her in his arms, smothering her with kisses.

"Please, Carl," she gasped. "Not—not now."

"But you are—"

"I know. Please go now. You may come back to me if you wish—at midnight."

He went into his own room, puzzled and a bit sulky, closing the connecting door with unnecessary violence. With difficulty he repressed a sudden impulse to turn and enter her room, then flung himself savagely into a chair.

"Patience, fool," he muttered. "Would you spoil everything now by haste?"

A glance at his watch revealed the fact that it was not quite nine o'clock. Three hours until midnight. And why had she said "midnight"? he wondered. He lighted a cigarette and pondered the matter.

An hour passed during which he consumed one cigarette after another. That hour seemed like an age as his watch slowly ticked off the seconds. He removed his clothing and put on pajamas and slippers, then resumed his seat in the chair and tried to read. Presently he fell asleep. Wild dreams disturbed his slumber and he tossed restlessly. One dream in particular caused him to moan and cry out in his sleep—the vision of a white face going down—down beneath the blue-green water.

HE awoke with a start, bathed in a cold perspiration, the horror of that dream fixed in his consciousness. A chill of horror ran the length of his spine. This would not do. He must pull himself together.

For the moment he had forgotten his tryst with his wife. His watch, lying on the dresser, showed one minute of twelve. Opening the door of her room, he looked in. She had extinguished her light and her bed was bathed in the silver rays of the moon shining in through the window.

He closed the door and stepped softly to her bedside. How pale her face looked, there in the moonlight, against the folds of wavy hair that were spread on her pillow! Somehow it reminded him of another face—a pallid face surrounded by whirling, foaming water—and he shuddered.

The mood passed quickly, however, and was followed by one of exultation. She was his—all his! The blood surged to his temples. His brain reeled with the mad intoxication of her nearness as he bent to take her in his arms. Suddenly he leaped back from the bed with a gasp of dread amazement. Instead of the soft, warm body of his wife, he had clasped to his bosom a cold corpse!

Doris dead? Impossible! What could have killed her? Had she taken her own life? At length he grew conscious of an acrid odor in the room and saw the cause. A half-emptied bottle of carbolic acid stood on the dressing-table. With a wild sob he gripped it in his shaking fingers and poured the searing liquid down his throat. He sank to the floor in agony as the great clock in the hall announced the hour of midnight.

DOWN at the railway station, a blind man boarded the midnight train. A blow on the head had gradually robbed him of his sight, and months of exposure on a tropical island had browned and dried his skin like parchment. Even his closest friends would scarcely have recognized him as Clayton Raeburn!