RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"Tam. Son of the Tiger," Avalon Books, New York, 1962

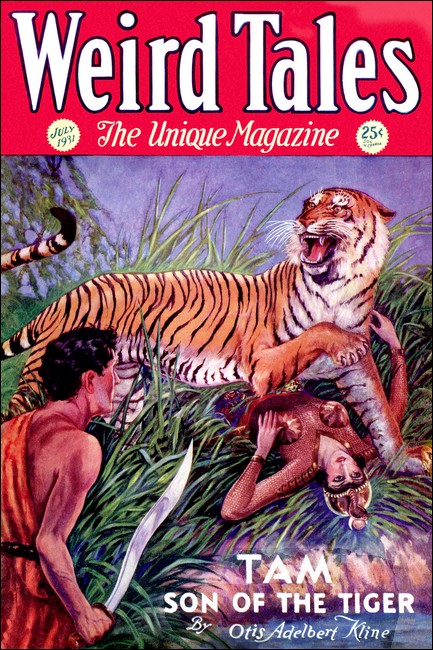

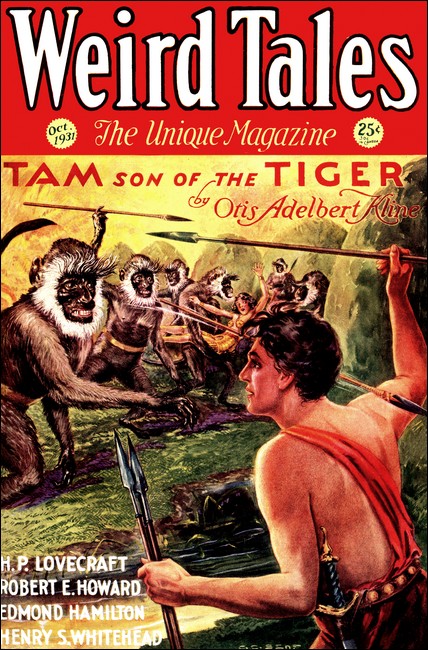

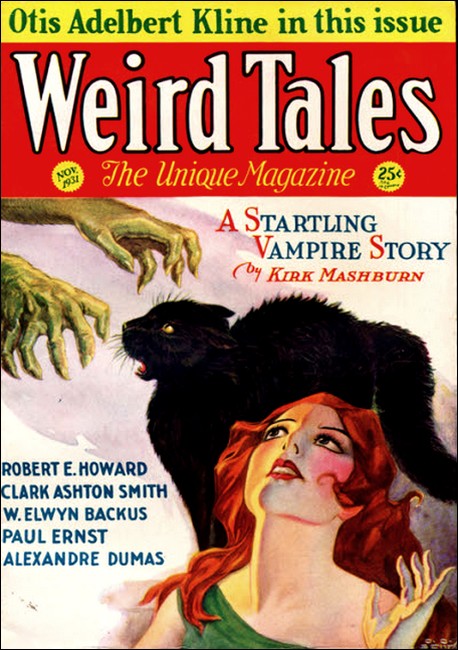

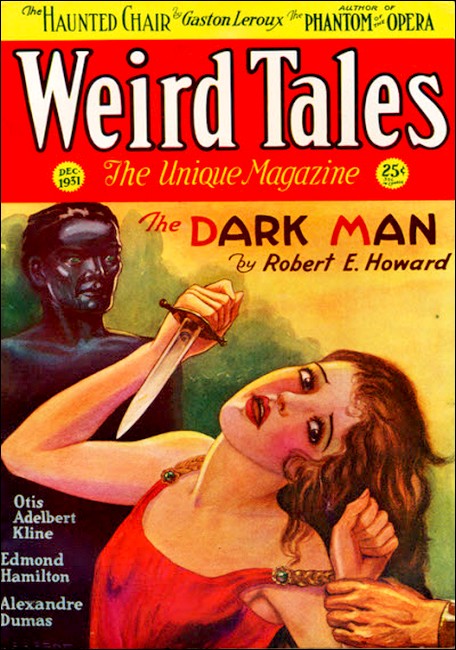

This complete and unabridged e-book edition of "Tam, Son of the Tiger" was built from a donated set of image files of the six issues of Weird Tales in which the novel was first published in 1931. With a view to preserving the "feel" of the original, it is divided into six parts, each of which is preceded by a copy of the corresponding magazine cover. It also includes all original illustrations, along with the publisher's blurbs and synopses.

—Roy Glashan, 22 January 2018.

Weird Tales, Jun-Jul 1931, with first part of "Tam, Son of the Tiger"

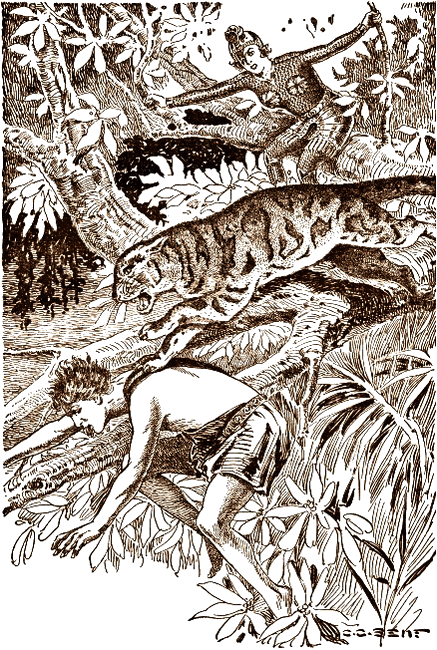

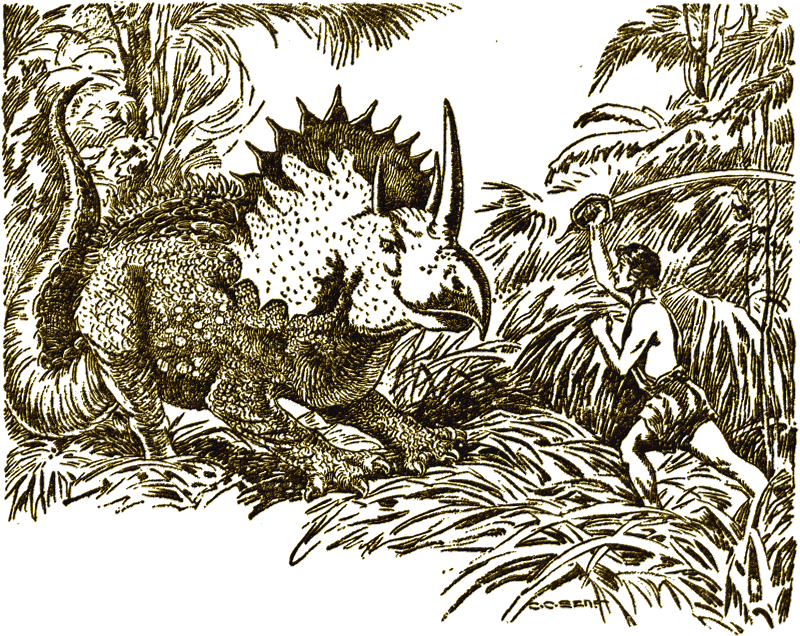

Tam dangled limply from her mouth.

BURMA—land of mystery, of gilded Buddhas and almond-eyed dancing-girls, of patient elephants piling teak, of shaven, yellow-robed priests, smoldering incense, and the silver tinkle of temple bells.

The jungle—teeming with tropical life and potential death.

In its upper branches were the feathered inhabitants. Liquid tones of sweet-voiced songsters competed with the harsh, raucous cries of parrots and crows. Flashes of brightly pigmented plumage contrasted with the greens and browns of the vegetation. Peacocks proudly spread their painted fans.

A little lower, monkeys chattered at spider-limbed gibbons with faces like little old men. A sleek, well-fed leopard basked on a thick limb, its mottled hide blending perfectly with the black and gold shadows that descended through the leafy canopy.

And on the forest floor, creeping through the undergrowth with cat-like stealth, was that most cunning and ferocious of all jungle creatures—the man-eating tiger.

The leopard bristled, laid back its small ears, and growled softly at sight of the huge striped terror passing beneath. The monkeys and gibbons heard that growl and scampered away through the branches. A rusty black crow cocked its head to one side and stared for a moment with beady eyes. Then it uttered a sharp, rasping "caw!" that plainly said "tiger!" to all jungle inhabitants. The peafowls rose, en masse, with a thunderous whir of wings.

And the tiger, snarling its anger at this premature exposure of its presence, and knowing that all concealment was at an end, charged straight for the human being, straggling behind the others, which it had marked for its prey.

MAJOR CHARLES EVANS, young American philanthropist and sportsman, had come to

Burma with a twofold purpose: to gather chaulmoogra seeds for planting on the

Hawaiian land which he had donated to the leper colony at Kalaupapa, and to

hunt tigers. With him were his wife, Lucille, and his two-year-old son,

Tam.

After a boat trip down the Irrawaddy and up the Mu from Mandalay, they had come to the village of Kyokta, near which it was said the chaulmoogra might be found. Scouts under the leadership of Zahn, son of the village tajies, or headman, had quickly located several extensive stands of the trees, and toward one of these Evans and his wife journeyed after a night in a Kyokta hut. They were guided by Zahn and his friends, who carried baskets for gathering the fruit from which the seeds were to be later removed. Tam had been left at the village in the care of his colored nurse maid, Clarabelle Jackson, who had accompanied them from the United States.

Zahn proudly marched at the head of the, procession. Just behind him walked the American and his wife. Major Evans was tall, broad-shouldered and athletic. He wore high laced boots, khaki trousers, a shooting-jacket with large pockets, and a pith helmet. Beside him walked his pretty young wife, dressed exactly like her husband, but so small and daintily feminine that even in mannish clothes there was no mistaking her sex. Four villagers who acted as gun-bearers came behind them, carrying two heavy, double-barreled .450 Bury rifles, a Winchester and a Savage. The major had high hopes of stalking a tiger, but not the slightest suspicion that, at that very moment, the striped death was stalking his own party.

Following the gun-bearers were a score of villagers with the baskets and bags which were to be filled with the fruit of the chaulmoogra. And at the rear trailed Kru Muang, youthful chum of Zahn. The handle of his basket was slung over one arm, and he was using his spear as a staff.

Suddenly the boy heard a sharp "caw!" from a near-by branch, followed by the flapping of startled peafowls, a low snarl, and the rush of a heavy body through the undergrowth behind him.

"Suar! Suar!" he shouted, springing forward. "Tiger! Tiger!" Then he uttered a single piercing shriek of terror and agony as the huge teeth of the charging man-eater sank into his shoulder, hurling him to the ground.

Half of the villagers instantly dropped their baskets and bags, and took to the trees. The others stood their ground, clutching their spears in readiness for attack, but making no move to help the stricken boy. The major wrested one of the heavy Burys from the trembling hands of a frightened gun-bearer, but before he could bring it to his shoulder a brown-skinned body flashed between him and the tiger, which was now shaking its prey as a cat shakes a mouse. It was Zahn, armed only with his spear, dashing to the rescue of his chum.

The man-eater saw him coming, and dropping its prey, launched its striped bulk through the air. Zahn halted and extended his spear, but the great carnivore swept the puny weapon aside with one huge paw, and seizing his face in its mighty jaws, bore him to earth.

Evans, who had not dared to shoot before for fear of hitting Zahn, now fired. At the impact of the heavy projectile, the tiger leaped high in the air. Just as it struck the ground the major fired again, and it sank down motionless beside the chief's son.

The sportsman reached for a second gun and advanced cautiously. Going up to the beast, he prodded it with the end of the weapon. But it was limp and lifeless. Shot first through the body, then through the head, the terrible man-eater had breathed its last.

Gingerly, the natives formed a ring around the fallen brute and his two victims. Lucille Evans glanced at Zahn, then averted her eyes with a shudder. He was past all help, his face completely bitten away. She knelt beside Kru Muang. His shoulder was cruelly torn and lacerated, but he was still breathing.

With water from her flask, and gauze from the emergency kit, she bathed his wounds. Then the major saturated them with iodine and helped her to bind them.

The natives had, meanwhile, rigged two pole litters for the fallen. The carcass of the tiger was suspended from another pole thrust through its bound feet and carried by four men. Then the sad little procession turned its footsteps back toward the village. There would be no journey to the chaulmoogra groves that day.

When they drew near to the village, the major went on ahead in order that he might break the news to the tajies before his son's mutilated body was brought in. But he met him coming out of the village at the head of a considerable body of armed men who seemed very much excited.

The major walked up to the old fellow, and said:

"It is my sad duty to inform you that your son, Zahn, has just been killed by a tiger. He died a hero, giving his life to save his chum, Kru Muang, who is being brought in badly wounded."

The old man halted, and for some time regarded him in silence, tears flooding his eyes and starting down his withered cheeks. Then he replied:

"Let us mourn together, sahib, for this day both of us have been bereaved."

"Both of us? What do you mean? Speak!"

"Your little son has just been carried off by a white tigress, sahib. We were coming out to tell you."

LEANG, the white tigress, stalked majestically through the jungle grass near the Village of Kyokta, her tail held high, and on her feline features a look of supreme satisfaction. She had just dined exceedingly well, having slain a water buffalo in the jungle, and was on her way to the river to quench the thirst which followed her feast.

Having drunk her fill at the stream, she was returning by the way she had come, when something white and spherical rolled across her path, startling her considerably. She was within fifty feet of one of the village huts, and knew that it must have come from that direction. This sphere, which caused her involuntarily to pause and then leap backward, was an affront to her dignity. Never before had she been molested by a human being. Men respected her, not only because she was a tigress, but because she was a white tigress. They did not send arrows, spears and bullets after her as they did at her common striped relatives.

She looked in the direction whence the sphere had come, and saw a tiny man-thing running toward her—a little lad with dark curly hair, wearing a loose khaki blouse, shorts, and tiny, high-laced boots. He was laughing, the spontaneous, carefree laughter of healthy childhood, as he pursued the rubber ball which he had just hurled into the jungle grass. The tigress crouched, waiting to see what he would do next.

Suddenly the boy came face to face with her—saw her for the first time. She snarled, politely warning him away, for Leang was not a man-eater. Furthermore, she had so stuffed herself with buffalo flesh that she would not be able to eat a morsel for many hours to come.

But this boy, it seemed, was not so ready to run from her as had been most other humans she had encountered.

"Ooh! Big kitty!" he exclaimed, and paused, staring at her.

She stared back, slightly jerking the tip of her tail in token of annoyance, and snarled again, but more softly.

"Big kitty mustn't be mad with Tam," he said. "Tam won't hurt you." Then he fearlessly and deliberately walked up to her and scratched her behind the ear.

The tigress was so amazed at this unprecedented temerity that she forgot to snarl again. The little hand scratching her neck felt good. She made a contented noise deep down in her throat, and tilted her head to one side that the boy might better reach the spot which had begun to feel so pleasant under his ministrations. Leang was purring like a house cat, but with a noise that more nearly resembled the rumbling of distant thunder. And while she purred, the boy prattled to her in a voice that was soft and soothing.

"Big kitty want to play ball?" he asked, presently. "Come on and play ball with Tam."

He picked up the ball and rolled it toward her.

Leang was a young tigress, and had not yet lost her liking for play. Moreover, she had played with a ball before, as she had been raised by a man—a very strange man. She tapped the ball lightly, rolling it back at the boy, who chuckled with glee. For some time they played together, the tigress apparently enjoying herself fully as much as the boy. Then their play was interrupted by the sound of a woman's voice.

"Tam! Tam! Where is you, honey?"

The boy paused in his play to reply:

"Here I am, Clarabelle. Come and see big kitty Tam found."

Again he rolled the ball at the tigress, but she paid no attention to it. She was snarling slightly, ears cocked in the direction whence the sound of the maid's voice had come.

The colored girl, who had been dozing in the doorway of the hut, and had awakened to find Tam missing, advanced toward the jungle grass which concealed boy and beast. Suddenly she caught sight of the tigress, and shrieked at the top of her voice.

Her cry brought people running from the bamboo huts near by. The old Buddhist priest poked his shaven head out the door of the teakwood temple. A crowd of people gathered around the negress as she shrieked again and fell in a swoon.

"Suar! Suar!" a voice cried, and some of the men ran to get their spears.

Tam picked up his ball and stood beside the now thoroughly aroused tigress. Her tail lashed the grass stalks and she growled thunderously. The menace in the cries and actions of the villagers was unmistakable. This was annoying. She and the boy had been having so much fun before this interruption. Well, they would go somewhere else to play.

She started away with a low invitation to Tam to follow, much like the "mew" of a mother cat. But he did not understand. He only stood looking at her. She paused and called again, but still he stood there, bewildered, looking first at her and then at the crowd of excited villagers surrounding the swooning Clarabelle.

Leang's feline mind considered. This man-thing was only a cub, and had not yet learned to understand the mother call. Like any other cub, he must be taught its meaning. She accordingly returned, and picking him up by the collar of his blouse, trotted away.

When they saw this the assembled villagers redoubled their cries. Men came running with spears. One carried an old muzzle-loading gun. But none of the weapons was used, for those who carried them saw that the tigress was white, a sacred animal which they believed to be a reincarnation of some great lady, perhaps a ranee, or even a minor goddess. While they watched, awe-stricken, she gave a great leap and disappeared in the jungle. She continued to run with tail held high and Tam dangling limply from her mouth until the sounds of the voices died away. Then she stood him on his feet.

Tam stroked her head and back.

"Nice kitty," he said. "Gave Tam big ride. More."

But Leang didn't want to linger, nor did she care to play just then. She did want to teach this man-cub to understand and obey her orders. Also her distending mammae had begun to remind her that she must get back to her own cub, which would be hungry and in need of her ministrations.

She took a few steps, calling to the boy to follow her. When he did not move she returned, and taking him by the arm, led him for a little way. Then she let go and called once more. This time, he followed.

But the way was long and difficult for a little boy of two, and soon Tam grew very tired.

"Wait, kitty," he called. "Don't go so fast."

But the tigress proceeded, paying no attention.

PRESENTLY, Tam stumbled and fell. He was exhausted. Leang turned and looked

at him for a moment. Then she promptly returned, picked him up by his collar,

and carried him on. His slight weight did not inconvenience her at all, for

Leang was fully capable of lifting the huge bulk of an ox or buffalo, and had

often done it.

After traveling many miles at a steady, tireless trot, she came to an ancient wall covered with vines and creepers. She leaped to its summit and, dropping lightly to the other side, crossed a weed-grown grass plot and entered the doorway of a small pagoda of wood and glazed tile, one of a pair that stood on each side of the entrance to a large wat, or temple, much of which was in ruins.

Inside the ancient pagoda, she set Tam on his feet. Then she affectionately licked the little striped cub that came toddling and mewling from a comer at her approach.

Tam tried to pet the cub, but it spit at him and he backed away. He had had some painful experiences with house cats that spit.

Leang lay down on her side and the cub promptly found a nipple. Soon it was purring contentedly, pumping industriously with both front paws as it absorbed the warm and indubitably fresh milk. Tam watched this process with considerable interest. It was long past his lunch time, and he, too, was thirsty and hungry. Presently he approached more closely and sat down beside the cub. The tigress leaned over and nuzzled him, pushing him down toward the source of the liquid food supply, of which there was an overabundance for her one cub. Then she lay back and rolled slightly—invitingly. It was a plain bid to tiffin, and the boy accepted hungrily.

Tam had tasted mother's milk, goat's milk, cow's milk and tinned milk, but never before had he tasted tiger's milk. And never before had milk of any variety tasted quite so good. He pumped and drank until his little stomach was distended quite comfortably. Then he slept, his tousled head pillowed on a furry foreleg.

When Tam awoke, the newly risen sun was sending its first shafts into the pagoda, and birds were caroling their morning songs. The tiger cub was curled into a striped, furry ball beside him, but the tigress was gone.

He looked about him in bewilderment at first, for it seemed to him that he must be in his little cot next to that of his father and mother, and that they were surely there beside him. When he realized where he was he began to feel very sad and lonely, and very much afraid.

"Mother!" he cried. "Daddy!"

But only the twittering, screeching and chattering of the jungle folk answered him.

He sat up and again called to his parents at the top of his voice. Them realizing that they were not with him, he began to cry.

The cub, disturbed by the strange noises, uncurled itself and toddled over to him. Evidently understanding that he was in distress, it rubbed its striped sides against him—a friendly, sympathetic gesture that showed it had accepted him as a member of the family circle.

Never before had there been a time in Tam's short life when his wailing had not speedily brought some one to do something about it—to pick him up, comfort him, and humor him. Now it amazed and disconcerted him to find that no matter how loudly he howled, nobody came. For the first time in his life he was learning the lesson which the prophet, Mohammed, learned many centuries before—that if one wanted a mountain and it wouldn't come when called, one had best go to the mountain.

Rubbing his tear-filled eyes with his small fists, he got up and walked out into the sunshine, the cub waddling after him. He was in a large, walled enclosure, in the center of which stood the ruined temple. The only way out was barred by a tall, brass gate, sagging on its hinges and covered with the verdigris of centuries.

Hungry, thirsty, and homesick, Tam wept softly to himself as he wandered aimlessly about the enclosure, accompanied by the cub. Convinced that there was no one to hear his cries, he no longer screamed at the top of his voice.

But one of the jungle creatures had heard. For a moment it gazed down from the top of the wall at this luscious and helpless morsel which might easily be had for the taking. Its eyes glowed with a greenish-yellow light which showed that it was fearful of the pungent tiger scent. But its hunger evidently overcame its fear of the great beast's lair, for it leaped lightly into the enclosure and bounded toward the boy and cub.

The cub spit angrily, then turned and ran toward the pagoda. Tam, looking up, saw a big "kitty," covered with black spots against an orange background, bounding toward him. There was something about its demeanor which struck terror into his little heart. He turned and ran after the retreating cub, but before he could reach the pagoda, sharp claws ripped through his blouse.

Then, snarling ferociously, the leopard bore him to earth.

LEANG, the white tiger-mother, awoke early and went forth into the gray dawn. After quenching her thirst at the ancient fountain of bronze and marble which, though centuries had passed since it was built, still bubbled and splashed in the center of the enclosure, she leaped the wall and set off through the jungle at a rapid trot.

It was with pleasant anticipation that she thought of the many pounds of buffalo flesh waiting to be consumed where she had left her kill the day before. The more she thought of that excellent meat the keener her appetite became, and the faster she trotted. True, it would have become a bit "high" after many hours in the heat, but this mattered not a whit to Leang. Although unlike some human epicures, she preferred her meat fresh, she was not at all averse to eating it after it had become quite putrid.

But as she drew near the spot where she had left the carcass there came to her sensitive nostrils a fetid body-scent that caused the hairs of her neck and back to stiffen and a low rumble to issue from her throat. Jackals! She bounded forward at top speed and arrived at the spot just in time to see a dozen slinking forms melt into the shadows. Of the carcass there remained only part of the skull, the horns, and a few gnawed vertebrae and rib bones, all reeking with the stench of the jungle scavengers.

Leang lashed the undergrowth with her long tail as she roared her rage and disappointment, but she did not attempt to follow the skulking forms. Many times before had she been despoiled of her prey by jackals, and she had learned that it was useless to attempt to capture the elusive thieves.

After sniffing about for some time to make sure there were no edible morsels which the jackals had overlooked, the thoroughly angered tigress set off once more toward her lair. As she traveled, she hunted by the way. Presently an unwary peahen fell prey to her skill and partly satisfied her hunger. This put her in a slightly better humor as she approached the temple ruins. Then she heard a cry—the wail of her man-cub. She quickened her pace.

A spotted form flashed to the top of the wall, hung there for a moment, and then dropped to the other side. Leang bounded forward.

Over the wall she hurtled in one great leap, her feet barely touching its top. Her own cub was scampering toward the pagoda. Her man-cub, trying to follow, was brought down by the leopard.

Intent on his prey, the spotted carnivore did not see the charging mother tiger until she was almost upon him. He turned just in time to receive a cuff that sent him rolling over and over for fully twenty feet. Recovering with the agility common to all members of the cat tribe, he dashed for the wall. Once in the jungle, he could easily elude the tigress. A tremendous spring carried him to the top of the wall. It was his last. Powerful jaws closed on the back of his neck. Long sharp claws sank into his mottled shoulders. He was dragged back into the enclosure.

The tigress and leopard fell to the earth together, the former growling thunderously, the latter screaming his fear and pain. As this fearful uproar smote upon the ears of the lesser jungle creatures, their own voices were stilled. Rodents hastily sought their burrows. Climbers scrambled for the highest branches. Birds flew to another part of the jungle.

But the screeching of the leopard soon ceased, as Leang, with the precision of a trained surgeon, bit through his cervical vertebrae. For a moment a shudder ran through his frame. Then he lay limp and lifeless beneath her.

Far overhead a passing kite paused in its flight, wheeled, and circled lower. Then it dropped like a plummet, alighting on the fronds of a tall palm that stood in the enclosure. Soon it was joined by a host of others, and by several vultures, all apparently materialized from a clear sky.

TAM, who had regained his feet and scampered into the pagoda with the cub,

crouched in the doorway, watching breathlessly. His back smarted where the

leopard's claws had punctured his khaki blouse, but he had not been injured

otherwise.

Crouching beside her kill, the tigress, whose tremendous hunger had only been partly satisfied by the peahen, leisurely began her second breakfast, starting on the hind quarters as is the custom with the great cats. Her audience of vultures and kites watched hungrily, the former craning their scrawny necks, the latter maintaining their balance on the swaying fronds by flapping their black wings from time to time as if applauding.

Her hunger satisfied, the tigress drank at the fountain and went into the pagoda. Tam, who had been fearfully watching the proceedings from the doorway, saw the kites and vultures descend to finish what was left of his terrible enemy. Then he joined the cub at breakfast.

Man can live where he pleases because of his capacity for adapting himself to any environment. Young or old, weak or strong, he has this ability to a far greater extent than any other animal.

And thus it was that Tam, finding himself living under a new set of conditions, was soon as much at ease in the tiger's lair as he had formerly been in the home of his parents.

Here he had a broader vista than the four walls of his nursery had afforded, and real live "kitties" for playmates, instead of imitations stuffed with sawdust and excelsior.

It was not long before Leang began bringing meat to her lair—freshly killed peafowls, wild boars, deer, and at times, great haunches of buffalo meat.

The boy and cub feasted very daintily on these at first, both preferring the liquid food to which they were accustomed. But it was not long before they grew to like meat above everything else, and became as clamorous as small children around a parent bringing candy whenever Leang returned after a kill.

The cub grew with a rapidity that amazed Tam. In six months he was as large as the boy, and much stronger, though Tam, playing with him every day, was developing strength far beyond his years. They had many romps and mimic fights under the approving eye of the tiger mother, and played with the ball until it was completely worn out by the cub's teeth and claws.

Tam's clothes soon went to pieces, but he had no desire to replace them. He was far more comfortable in that hot climate without them. His shoes soon began to pinch his growing feet, and he discarded these, also.

It was not long before he began thinking of himself, not as a human being but as a tiger. He imitated all the sounds made by Leang and the cub, and soon grew to know the meaning of each. He could understand them or be understood without difficulty.

When the cub grew large and strong, Leang, as is the custom of tiger mothers, brought live game into the enclosure to be killed by the youngsters. Here the cub excelled, as in the mock fighting, and Tam shed tears of envy because of his own inability to grow such splendid claws and teeth.

Leang also taught both of them the value of moving silently through the grass and undergrowth. One of their favorite games was for both to separate, then each to try to stalk the other. At this game Tam soon learned to excel the cub, and these victories helped to salve his wounded pride at being defeated in the mock battles and outclassed in the game killings.

Then came the time when Leang called them to accompany her on a hunt. The cub was, by this time, able to leap to the top of the wall, but Tam, try as he would, couldn't make it. Fearful of being left behind, he ran to the gate, squeezed his slim brown body between the bars, and hurried after the two beasts, his feet as silent and his movements as stealthy as Leang's own.

They found royal game indeed for the first day. It was a big bull buffalo. Leang showed them how to stalk it, keeping to windward and moving noiselessly. But when she roared the signal to charge, Tam made the mistake of getting in front of the beast. Before it was dragged down by Leang it tossed the boy with one long horn. Scratched and bruised, but not pierced by the horn, Tam fell in the soft mud fully twenty feet away. He had learned, long since, that crying was a useless accomplishment in the jungle, and got up without a whimper to return for his share of the kill.

There were many hunts after that, in some of which Tam was quite painfully injured. But he eventually learned to avoid the horns and hoofs of deer and buffalo, and the tusks of boars.

BY THE time Tam reached his seventh year the cub was a full-grown tiger, as

large and strong as his mother. Sometimes the three hunted in concert, but

often one or the other would wander off to hunt alone.

Tam took to exploring the jungle by himself, not merely for the sake of hunting—he killed only when hungry—but because of the pleasure it gave him to observe the wild things. Leang had taught him to avoid the haunts of men, but like all boys he was very curious, and often went as near to the villages as he could approach without being seen, in order to learn how the strange and terrible creatures, shaped like himself, lived.

Once he saw a traveling fakir charming a cobra with his queer, squalling noise-stick. Tam remembered the sounds made by that strange stick, and on his return to the wat imitated them with considerable success, for he was a born mimic.

Leang had taught him to give all serpents a wide berth, and for this reason he had never dared to explore the rear rooms of the temple, which were inhabited by cobras. He decided to try his new magic on one of them. The subject he selected paid no attention to him at first, but he persisted until it raised its hooded head and swayed in time to the barbaric strains. Emboldened by his success, he approached the snake, stroked it, and picked it up, finally depositing it on the floor and getting away unscathed. Often after that he amused himself at the dangerous sport of snake-charming, until the cobras paid no more attention to his comings and goings than to each other.

After this, he made friends with many of the other jungle creatures. By watching them patiently, day after day, he learned the meanings of the various sounds they made, and, imitating them, was thus able to converse with each in its own language.

From the monkeys and gibbons he quickly learned the art of swift silent travel through the upper traffic lanes of the jungle. From these, also, he learned that certain fruits and nuts were very good to eat, and often supplemented his meat diet with them. As soon as they learned that he would not harm them, they accepted him as a friend and companion, and he passed many pleasant hours with them, amused by their strange antics.

Two or three times in his wanderings he came upon men, and these meetings were always unpleasant. The first man he met, a member of a fierce hill tribe, hurled a spear at him. It pierced his arm and clung there for some time as he scurried away through the forest. He plucked it out and flung it from him, but it left a painful wound that was many days in healing.

Several times after that he came upon men unexpectedly, and all of them were ready to use their weapons first and ask questions afterward. He decided that men, like leopards, jackals and hyenas, could only be regarded as dangerous enemies, and had best be avoided.

The first herd of wild elephants he encountered excited his wonder. For many days he followed them, observing how the great pachyderms lived.

Once, in his northern wanderings, he came into a teak forest that was being worked. Here there were many elephants laboring under the direction of men, who sometimes walked beside them, sometimes sat on their necks. These elephants wore wooden bells that went: "Tika, tok, tok, tok," and some had leg-irons that clanked when they moved.

Always keeping well out of sight, Tam watched the mahouts, striving to learn how they controlled the great brutes, and resolving that some day he, too, would capture an elephant and cause it to obey him. He noticed that the ankus, or elephant hook, was a part of every mahout's equipment, and one night succeeded in pilfering one and getting away unscathed. He returned to the wat with his treasure, but the wild herd had moved to another feeding-ground; so he put the ankus away in the pagoda for future reference.

Tam took no notice of the passing of time, but he did notice that as the seasons came and went he grew larger and stronger, whereas, after the fifth year, Leang's cub had ceased to grow. Several times during those years, strange tigers had come to the wat, evidently attracted by Leang, but these she had always driven away.

In his wanderings through the jungle, Tam also met a number of strange tigers. They neither ran from him nor attempted to attack him, but treated him precisely as if he were another tiger. This was because if they voiced their thoughts and feelings, as tigers often do, he answered them in their own language. If they remained silent, he addressed them in the same language, making it plain that though he was friendly enough, he was not to be trifled with, for he was a very devil of a tiger, himself.

By the time he was twelve years of age he could pull down his buck or boar quite as well as Leang, though a buffalo was still too much for him.

One day, after he and the two tigers had slain and devoured a buck, they returned to the temple enclosure to drink at the fountain.

Suddenly they heard a voice, a human voice, at the gate.

"Leang," it said.

Turning, Tam beheld a tall man with a wrinkled yellow face, peering through the gate. He wore a red cap, and a robe of the same color, caught over his left shoulder. His right arm and shoulder were bare.

To Tam, every man was a deadly enemy. He snarled fiercely, and the tiger echoed his snarl.

But Leang only stared at the stranger.

LOZONG, the pious lama, drew his robe of red Lhasa cloth more tightly about his tall, straight figure as he plunged into the jungle trail which he had not taken for more than ten years, and which was nearly obliterated by the vegetation.

When necessary, he swung his dah, or double-curved jungle knife, to clear the path. But as he cut and forced his way through the thick undergrowth he did not for a moment cease to lay up merit for himself in the world to come, for over and over again his lips framed the mystical formula: "Om mani padme hum."*

[* O, Jewel in the Lotus, Amen.]

Despite his priestly garb and pious declamations there was something in the bearing of Lozong which made it appear that he had not always been a man of the robe and alms-bowl. His straight, soldierly figure smacked more of the camp and battlefield, and the ease and precision with which he used his dah showed more than casual acquaintance with a cutting weapon.

His Mongoloid features were old, and yet young, for though his sun-cured skin was like wrinkled yellow parchment, his black eyes flashed with a fire that was decidedly youthful. They were the eyes of a conqueror, descendant of a race that had once terrorized the entire civilized world, and were strangely incongruous in the otherwise austere countenance.

As he hewed and chanted his way through the jungle, he wondered if Leang, the white tigress, still lived in the pagoda before the temple ruins in which he had made his home for five years, and from which, ten years before, he had emerged to go on a long pilgrimage. He had visited most of the celebrated shrines of India, Burma and Siam, learning Sanskrit that he might study the ancient religious books of India, and seeing many strange and wonderful sights.

Thirteen years before, Lozong, who had retired to the old sacred ruins to meditate in solitude and to lay up merit, had found an orphan tiger cub less than three months old playing in a nest beneath the umbrella-like foliage of a korinda. The bones of the mother lay near by, picked clean by scavengers. She had evidently been shot or poisoned, and had succumbed before she could reach her lair.

The cub, which was a white female, was half starved. Had it been an ordinary striped animal, Lozong would have left it there to die, but as it was white, and therefore sacred, he could acquire much merit by saving its life. He had accordingly captured the spitting and growling youngster in his robe, and taken it to his retreat, establishing it in a grass nest in the pagoda. After that, for many months, he had been kept busy trapping birds and small game for his young charge, which he named Leang. He built traps that caught the game alive, then permitted his pet to kill it, herself, so he need not commit the sin of taking animal life.

But Leang had eventually learned to do her own hunting, and when she was nearly three years old, began consorting at night with her own kind. Lozong let her come and go as she pleased, and she remained quite friendly until, one morning when he approached the pagoda, she warned him away with a thunderous growl. He understood, and did not go near her den for many days, nor did she come to see him in his temple room as was her wont.

But one day as he was seated on the temple steps eating his frugal meal of curry and rice, donated by a village housewife, she had emerged from the pagoda followed by four striped cubs which she proudly led up to him for inspection.

A few days later a tiger came—a great striped brute. He killed and ate three of the cubs which had been playing in the temple enclosure. The fourth, asleep in the pagoda, he overlooked. Leang returned as he was devouring the third little body. Lozong, watching from the temple corridor, saw an exhibition of feline fury such as it falls to the lot of few men to witness. The tiger, badly scratched and bitten, beat a hasty retreat. Nor did he dare come near the place again. He had been Leang's mate, but never would she mate with him again.

A few days thereafter, Lozong had gone on his long pilgrimage, bidding the sacred tigress and her remaining cub a fond farewell. Now, as he neared the temple ruins, his thoughts were on the two creatures he had left there.

Leang would be thirteen years old. The cub, which he had named "Chiam," would be ten—a full-grown tiger in his prime.

Suddenly, as he neared a little glade which he knew to be but a short distance from the temple ruins, he heard the roar of a charging tiger and the crashing of heavy bodies through the underbrush. Silently he slid behind a tree and watched.

Into the glade a buck came leaping. Behind it bounded an immense tiger. It looked as if the buck would escape when there swiftly flashed from the undergrowth in its path, a lithe, sun-browned human form—a slender boy about twelve years of age, naked and unarmed. From the other side a white tigress charged. But it was the boy who brought down the game. He met the buck in midair, gripped the antlers and twisted them to one side. As his prey went down he uttered a roar that matched that of the tiger, and sank his teeth into the furry throat.

Then, while the astonished lama looked on from his place of concealment, the boy and two beasts settled down to feed on their kill.

Lozong did not doubt that the white tigress was Leang. And the tiger might be her cub, Chiam, or a new mate. But this naked, black-haired boy with the voice of a tiger and the muscles of a gladiator—who could he be, and whence could he have come? It was plain that he was not of the tribes of Burma or Siam, nor yet of India or Tibet. Though his skin was deeply tanned by the sun, he was undoubtedly white, like the English or French.

The lama knew better than to approach a feeding tiger. So he kept out of sight until the boy and the two beasts had finished. He knew that after they had eaten they would drink, and wondered if they would go to the river or the temple. When they turned toward the ruins his belief in the identity of Leang was confirmed, and he followed silently.

THE boy and the two brutes leaped the wall, and Lozong, watching through the

bars of the bronze gate, saw them drinking at the fountain.

When they had finished, he cried: "Leang."

The tigress turned, looking curiously in his direction. The boy and tiger both snarled.

"Leang, come here," he called, as he had summoned her in the old days.

She pricked up her ears, elevated her tail, and trotted toward the gate. Behind her came the boy and the tiger.

In Leang's attitude there was only curiosity, but the others were openly hostile.

"Don't you remember me, Leang?" asked Lozong. "Don't you remember your old master who fed you?"

The tigress sniffed at him through the bars. The boy and tiger were snarling belligerently.

Suddenly, with an angry snarl, the boy sprang—raked the lama's bare shoulder with his nails. But Leang turned on him—cuffed him back. At this instant the tiger leaped, but him also she buffeted back. Then she rubbed her jowl against the bars, and Lozong knew that she remembered.

Fearlessly he scratched her under the chin—behind the ear—while she purred loudly. The boy and the tiger remained in the background, still unfriendly, but obedient to the tigress.

Presently the lama took a large bronze key from the voluminous breast pocket of his robe, and inserted it in the lock of the gate. It stuck with the corrosion acquired during his ten years' absence, but he eventually succeeded in turning it. Then he swung the gate on its complaining hinges and boldly entered, closing it after him.

Leang stood aside to let him in, then walked with him as he fearlessly strode toward the temple. He watched the boy and tiger from the corners of his eyes as he passed, but they made no move to molest him. It was evident that they had a wholesome respect for the authority of the white tigress.

Straight through the ruined temple portal he went, and to the room he had previously occupied. Here he squatted, cross-legged, on the floor, and Leang stretched out beside him. Unslinging his alms-bowl, he lifted the bit of oily paper which covered it, disclosing the rice and ghee which a woman of the near-by village had given him.

He made a greasy ball and held it out to Leang, just as he had fed her from his bowl ten years before. She took it daintily, chewed it much more than was necessary, and swallowed it. But when he offered her more she turned her head away. Evidently buttered rice was no longer to her liking. It was as if she had taken the first morsel for politeness' sake.

Lozong ate rapidly, for the sun was nearing the zenith and it was not permitted that he eat solid food after midday. Having completed his plain but satisfying meal, he took his water-strainer from his pocket and went out for a drink at the fountain, the strainer being a religious rather than a hygienic precaution, as it was unlawful for him to take animal life, even of the most minute kind.

Stretched in the shade of one of the mango trees that lined the approach, the boy and tiger barred his path to the fountain. The lama did not wish to show fear, nor did he desire to arouse either of them, as he knew that if one should spring for him, the other, also, would attack.

He advanced cautiously, intending to circle the two and pass on. But just as he turned aside from the path, an ugly, hooded head reared its spectacled death-sign above the grass.

The cobra swayed angrily for a moment with darting tongue—then struck.

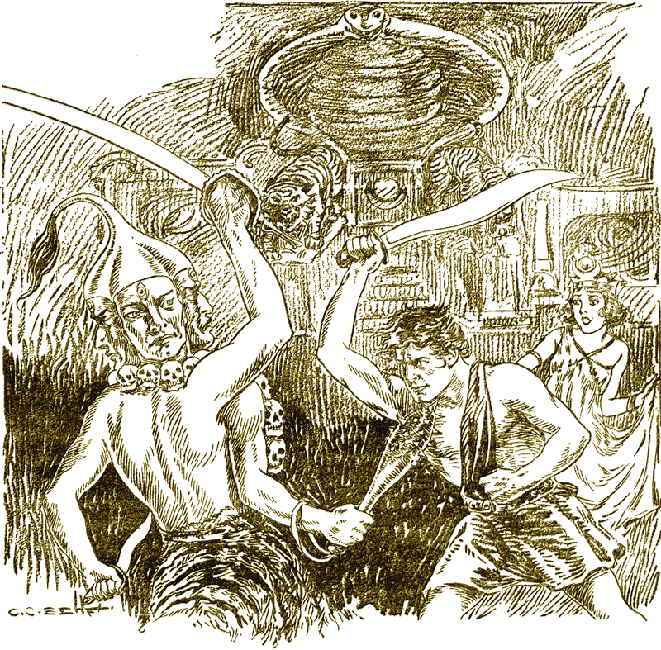

THE head of the striking cobra moved as swiftly as an arrow, yet just a fraction of a second quicker flashed the dah of Lozong. There was a scarcely perceptible turn of the lama's wrist, and the keen blade severed the venomous head with the neat drawing cut of an expert.

Although he had momentarily saved his own life by his quickness with the weapon, Lozong, by making the sudden movement, had instantly put it in jeopardy again. The boy and tiger, basking in. the shade, both took it for a hostile gesture. Their roars resounded together as they sprang for the lama.

According to Lozong's belief he had committed a deadly sin by slaying the cobra, despite the fact that he had acted on the spur of the moment to save his own life. Many thousands of "Om mani padme hums" would have to be said before sufficient merit was acquired to atone for this one act.

But the instinct of self-preservation made him turn again at this new attack, his dah lightly balanced in the hand so skilled in its use, as the boy and tiger sprang at him.

Leang, right behind her former master, leaped for the tiger, knocking him over. In an instant he was rolling on the ground with the tigress standing over him.

Seeing this, the lama smiled and dropped his dah as the boy sprang upon him. Tiger fashion, the lad attacked with teeth and nails. And tigerish was the strength of the muscles that rippled beneath his sun-browned skin.

But Lozong, who had not always been a lama, who was a past master in the arts of offense and defense, knew how to meet his every movement and turn it into defeat. Had it not been for the uncertainty of what the tigers might do, he would have played with him. But because of that uncertainty, he quickly ended the contest.

Catching one extended wrist, the lama turned and dragged the arm across his shoulder, throwing the boy heavily. Before he could recover, he was down beside him, his hands playing skilfully here and there. The lad was, for a time, paralyzed—helpless. Lozong had learned jiu jitsu from a Japanese expert, and learned it well.

Picking up his dah, the lama sheathed it and proceeded serenely toward the fountain, precisely as if nothing had happened. He drank, then returned to the temple, looking neither to the right nor the left. The boy, still unable to move, snarled as he passed, but the tigers, now lying side by side in the shade, made no sound.

Lozong squatted, cross-legged, in the shade of the portal, and began clicking the wooden beads of his rosary, the while he muttered his monotonous: "Om mani padme hum." This prayer would have to be said countless thousands of times in order to recover the merit lost by slaying the cobra.

But the repetition of the prayer was purely mechanical. His mind was occupied with the problem of making friends with the other occupants of the wat. Leang, he believed, could be counted on to remain friendly. The tiger, which he now felt sure was Chiam because of the way Leang had cuffed him about, was more of a problem. Though he had petted and handled him when a tiny cub, there was no possibility of that memory assisting him now. He must find some other way.

And the boy. He, indeed, was the greatest problem of all. Wild and ferocious as the tigers, and aided by a mind far superior, he could be approached only with the greatest caution. Lozong pondered the course to be pursued as he muttered his prayers and gazed out at him through the dancing heat waves.

Presently the lad, finding himself able to move once more, stood up. He flexed his muscles as if to make certain that they would serve him. The lama forgot his prayers for a moment, fearing another attack as the boy looked in his direction. But the lad turned and went over to where the headless body of the cobra lay. No malice showed on his features—only wonder and curiosity. After examining the decapitated reptile with evident puzzlement, he went over and lay down in the shade with the panting tigers. So far as the lama was concerned, he seemed disposed to ignore his presence.

As he lay there in the shade, Tam, though feigning to completely ignore the strange being who had moved into the wat, very much concerned about him. He was puzzled by the fact that Leang not only obeyed him as if she were his cub, but actually showed affection for him, even to the point of protecting him against her own offspring.

Despite the fact that he had always considered all men as his enemies, Tam was beginning to believe that this unusual person, who had defeated him almost painlessly, was friendly.

Suddenly the man in red began making strange noises with his mouth, which sounded very much like those made by the people of the villages. To Tam, they were incomprehensible, yet the man seemed to be addressing him. Although, during his ten years in the jungle he had learned the language of most of the wild things, Tam had not picked up a single human word to add to the meager nursery vocabulary he had brought with him at the age of two. And even this, through disuse, had been long forgotten.

But now the man was making noises which aroused some latent memory. Having tried him with Tibetan, Burmese and Siamese, Lozong was now speaking English.

"What is your name, my son?" he asked. "Who are you?"

At the words: "What is your name?" there flashed through Tam's mind the recollection of an answer which should follow—an answer in which he had been drilled, day after day, by his parents in case he should ever be lost. He turned and faced the lama as he replied:

"Tam Evans, 1130 Lake Shore Drive, 'Phone Lake Shore 0206."

"Come over here and sit with me in the shade, Tam Evans," said Lozong. "I would be your friend."

Tam stared at him in bewilderment, not because he couldn't comprehend his meaning, but because he could. Gradually taking form in his objective consciousness were memories, shadowy and indistinct, of his father and mother, and of his black nurse-maid, who had made such sounds which he had understood, long, long ago. Yet never, since that time, had he heard human beings make sounds which had any meaning for him.

"You need not be afraid. I won't hurt you," assured the lama.

At this, Tam sneered.

"You hurt Tam? Tam afraid? No! Tam is a fierce kitty. Tam could kill and eat you." He amazed himself as the unfamiliar speech rolled from his lips, for he was translating into English exactly what he would have said to a strange tiger inclined to be bellicose.

The lama smiled. He knew better than to dispute the boy's strange statement at this stage.

"All right, fierce kitty," he said. "Come over and talk to me."

Tam walked over and crouched on the steps near him. They talked long, the erudite lama skilfully adapting his speech to the boy's tiger-like thought processes and limited vocabulary. And thus there began a firm friendship that was to last for many years.

THAT night the lama slept on the bare floor of his cell. The following

morning when he awoke, he found freshly gathered fruit lying beside him, and

a newly killed bird of paradise. He ate part of the fruit, but the bird he

would not eat raw, and it was forbidden that he should prepare his own food,

so he carried it outside.

Neither Tam nor Leang was in sight, but Chiam the tiger was lying at the foot of the temple steps. Lozong tossed the bird to him. He leaped back with a snarl, then seized it and carried it off to the bone-littered space before the pagoda, to devour it.

Lozong drank at the fountain, let himself out at the gate, and with his alms-bowl tucked in the large breast pocket of his robe, set off for a near-by village.

He had not gone far when he heard a rustling in the branches above his head. Looking up, he beheld Tam. A gibbon that had evidently been with him scampered off through the branches.

"Where you going?" asked the boy. "To the village where men live," replied the lama.

"Don't go," said Tam. "They will kill you with sharp sticks, and eat you."

"No, they will give me food to eat," replied Lozong.

Tam followed him as far as the edge of the jungle, but would go no farther. When the lama returned, his bowl filled with curried vegetables and rice, the boy was waiting for him. They walked through the jungle together, back to the temple ruins. As they were passing through the courtyard, Chiam, the tiger, came out of the pagoda. At sight of the lama, Chiam growled menacingly, and barred his way to the portal.

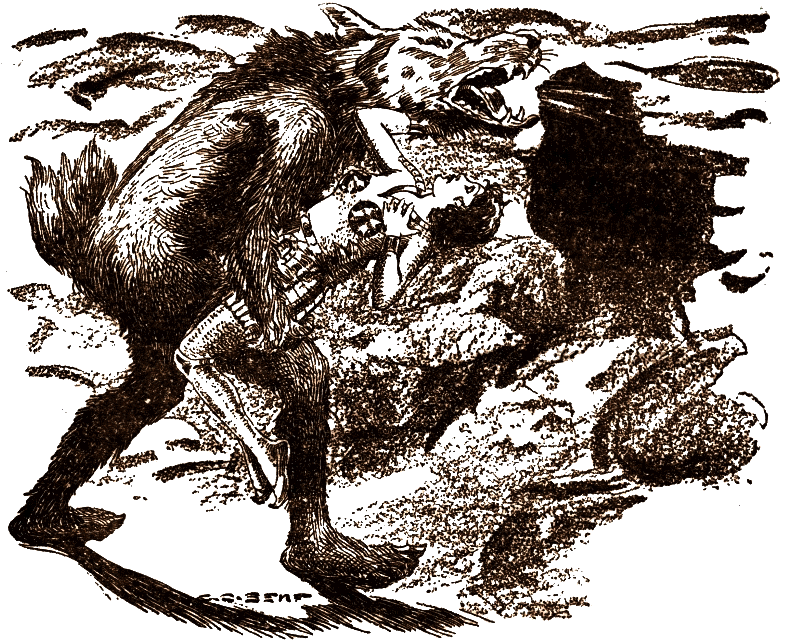

Lozong paused. This time the white tigress was not there to defend him. Chiam advanced, ears laid back, tail lashing the air, voicing his disapproval of the lama in no uncertain tones.

To Lozong's surprize, the boy leaped in front of the tiger. There issued from his throat a growl that matched, in volume and ferocity, the voice of the big feline. For some time, boy and beast growled and snarled at each other. Then the tiger sprang.

The lama dropped his begging-bowl and whipped out his dah, expecting Tam would be mangled by those terrible teeth and claws. But the boy leaped lightly to one side, and before the beast could recover, had flung himself on its back. Gripping the loose skin of its neck and locking his feet far back beneath the belly, he hung on like grim death. The tiger flung itself over backward, rolled over and over, and tried its best to paw him off, but to no avail. Presently the beast subsided, panting.

Tam laughed, and releasing his hold, scratched the big feline behind the ear, making low, purring sounds meanwhile, which were answered by the tiger.

Then he stood up and returned to where the astounded lama waited.

"Kitty won't hurt you, now," he said. "I told him you were our friend."

"But you might have been killed," exclaimed Lozong.

Tam laughed.

"We play like that, often," he said. "When I was little and weak, he could beat me, but now I am big and strong. Now I win the games. He still has better teeth and claws, but I am quicker. Some day when my teeth and claws grow bigger it will be easier."

"You will grow bigger some day, Tam," said the lama, "but you will never have big teeth and claws. Men do not have them. You must stop thinking you are a kitty, because you are a boy, and when you grow up you will be a man."

"I was a boy, once," replied Tam. "I remember a little about it."

"And you are still a boy," replied Lozong. "There are many things I must teach you, which boys and men should know." They sat down in the shade, and there across the alms-bowl began Tam's first lesson.

EACH day, Lozong made his morning trip to the near-by village. But about two weeks after his arrival at the temple, he returned with a parcel wrapped in heavy paper. He made a great mystery of it until he and Tam reached his cell. Then he unwrapped it ceremoniously.

Tam watched, with wide-eyed curiosity, as the lama took out several books, pads of writing-paper, pencils, and a ruler. "What are they?" he asked.

"I sent for them," replied Lozong, "in order that I might teach you to read and write the language of your people. These will be the foundation for your education."

And thus, at the age when most children have graduated from grammar school, Tam made his beginning.

He progressed rapidly, and Lozong ordered more books and supplies for him from time to time. Each afternoon was set aside for his studies. His mornings were usually spent roving in the jungle. The lama was an excellent instructor because he made everything interesting, and Tam's thirst for knowledge was insatiable.

Book knowledge was not all that Lozong taught his pupil. He taught him jiu jitsu and boxing, and the use of the dah. At first he let Tam use his knife, but one day he brought him a bright new one from the village, with a sheath and belt. He had previously persuaded Tam to wear a garment which he had cut for him from red Lhasa cloth. It was merely a narrow strip of the material passed over his left shoulder and wound about his loins, but quite enough for that climate.

When Tam had become proficient with the dah, the lama brought him other weapons and taught him their use. They soon accumulated quite an arsenal of spears, bows and arrows, crossbows and their shorter projectiles, blowguns and darts, axes and swords. For hours at a time they would practise shooting at marks, hurling spears and knives, and fencing.

Lozong's favorite weapon was the terrible yatagan, or double-curved sword. With this, he would fell a tall tree at a single blow, then instruct his pupil to cut it up.

At first, Tam could not more than cut half through the trunk of a tree felled by his teacher, but gradually he got the knack of it.

"Slice!" Lozong would cry excitedly, when Tam, in spite of his powerful muscles, would end with his blade still sticking in the wood. "Watch this. Observe that I do not strike with half the force you used, yet my blade passes clear through. Why? Because I turn the wrist, so, and draw the blade back, so; so I bring it down. Your wrist should be of rubber, not of wood. You chop like a clumsy Chinaman."

So Tam would try again and yet again. But he was sixteen before he could cleave through a trunk that Lozong had felled at a single blow, and twenty before he had become his equal at fence. Meanwhile, his studies had progressed tremendously. He could read and write Tibetan and Sanskrit as well as English, and had studied and discussed with Lozong the sciences and the leading religions of the world.

But most of all, he liked to hear Lozong relate his interesting life experiences—how his people had moved to Hangchow from Tibet when he was a boy, and he had become a Christian and gone to school at the Ching Nea Way, the American Y.M.C.A. Then how he had gone to Japan and saved the life of a descendant of the samurai, who had taught him jiu jitsu and swordsmanship. And then how he had gone to visit his parents, who had moved back to Tibet, and while there, had been left for dead by a company of Chinese soldiers that had massacred the entire village, including his parents and his brothers and sisters. Embittered against the Chinese, he had turned brigand, and soon became leader of the most dreaded band of marauders in that region. His fame had spread, and new recruits had flocked to him until he became a military power to be reckoned with.

But he grew sick of bloodshed and endless campaigns, and at thirty decided to give up all his possessions and seek salvation by way of the eight-fold path. He had accordingly taken leave of his followers and entered a lamasery, but such was his popularity and piety that in less than a year he had become its chief lama.

Still dissatisfied, he left the lamasery in charge of a subordinate, and set out on a pilgrimage, a seeker after that elusive entity, Truth. Wandering through Burma, he had accidentally found the ancient ruins, where he had tarried for a time to meditate and study in solitude, and near which he had found Leang.

At twenty, Tam had not only grown mentally, but had attained to splendid physical manhood. He was slightly taller than Lozong, who was six feet without his sandals, broad-shouldered, narrow-hipped, and superbly muscled.

Leang and Chiam had become middle-aged tigers, and though he still hunted with them, Tam now employed the weapons Lozong had taught him to use. Like his preceptor, he came to favor the yatagan above all other weapons. With this he could sever the neck or split the skull of a charging buffalo at a single stroke.

Nor had he forgotten his many jungle friends. These he had cultivated through the years. But the achievement which had pleased him most of all was his conquest of a mighty bull elephant. The great bull, suffering from that strange temporary madness called must, had slain his mahout one day when the man had used his ankus a bit too roughly, and dashed off into the jungle. He had managed to elude the men sent after him, and his wanderings had brought him to Tam's hunting-grounds.

For many days, Tam had watched him, feeding in the forest or wallowing in the river, spraying himself with water. From the first day he carried the ankus which he had been keeping for just such an occasion. Though he feared no jungle creature, it was with some trepidation that Tam went up to the great brute for the first time carrying a peace offering of fruit.

The elephant, which had fully recovered from its illness by this time, readily responded to the commands which Tam had learned by observing the mahouts, and he received one of the greatest thrills of his life when, swung upward on the trunk of the huge pachyderm, he took his seat behind the gigantic head and, ankus in hand, rode off through the forest.

He said nothing of his conquest to Lozong, but several days later, when he and the great brute had become better acquainted, he rode his mighty steed down the path to meet the lama on his return from the village.

Astounded, Lozong looked on while Tam put the big beast through his paces, finally causing him to kneel so that the lama might mount his back. They rode home in state that night, or nearly so, for the elephant stopped and refused to budge when he scented the lair of the tigers. By much perseverance and the employment of fruit and balls of sweetened rice, Tam eventually persuaded him to enter the enclosure and actually to make friends with the two tigers. After that, Ganesha, as they called him, made his headquarters in the temple enclosure. He was friendly toward Lozong, but showed positive affection for Tam.

ONE DAY Ganesha wandered away, and did not return that night as was his wont.

Worried, Tam set out on his trail the next morning.

As usual, Tam carried the weapons which had made him master of the jungle. From his belt hung his dah and yatagan. At his back was his quiver, containing his powerful bow and a supply of arrows. In his hand he carried the ankus, his scepter of authority over the elephant.

The trail of Ganesha led straight to the north, and Tam followed it all morning without pausing. But as the blazing sun reached the zenith he decided to halt for rest and refreshment. He had eaten only a little fruit for breakfast, and his long tramp had engendered meat hunger. He turned aside from the trail to hunt.

Traversing a dense thicket of bamboo, he came out in a flat expanse of tall jungle grass through which a little brook meandered. Thirsty, he went down to the stream to drink. He had barely touched his lips to the purling water when he heard a movement in the tall grass on the farther bank. Silently he slid back into the rushes and drew his yatagan. No doubt this was some jungle creature coming for a drink. Well, it should supply the meat he craved. The breeze was neither in his favor nor against him, but blowing downstream, so his nose told him nothing. He must wait for his eyes to reveal the quarry.

As he crouched there in the rushes, Tam gasped in amazement at sight of the wondrous creature that emerged from the waving jungle grass. A slender girl, panting and swaying as if from exhaustion, ran out on the bank.

Her garments were unlike anything he had ever seen or heard of. On her head was a tight-fitting golden helmet crowned with a gold disk above a silver crescent, set on a uraeus with eyes that were smoldering rubies. Wisps of her dark-brown hair peeped from beneath the magnificent head-piece, and in her hazel eyes was the look of one who has just escaped some unspeakable horror. Her shapely limbs and torso were encased in light, golden chain mail, reinforced by sliding shoulder plates, circular breast plates, and a jointed girdle with a skirt of faces, and adorned with glittering jewels set in strange designs. From her belt of scarlet leather hung a dagger sheath and sword scabbard, both empty.

Fascinated, Tam stared in breathless wonder and admiration. But the slight hint of a movement in the tall grass behind the girl drew his jungle-trained eyes. Something was stalking her! Then he saw the striped tip of a long tail lashing above the grass, and he knew!

He leaped up, a cry of warning on his lips, but at that moment the tiger sprang, emitting a thunderous roar as it crushed its victim to the ground.

With an answering roar, Tam leaped across the brook and confronted the tiger, his yatagan gleaming in his hand.

Standing over the prostrate girl, the tiger snarled its anger at this presumptuous human who had the temerity to dispute its right to its prey. Then it charged and reared up to seize its challenger, teeth gleaming and claws aspread.

With the swiftness of lightning flashed the razor-sharp yatagan. It caught the rearing tiger squarely between the eyes, and divided its skull as neatly as a dah divides an orange, finding lodgment in the neck vertebrć. Like a thing of inflated rubber, the mighty body collapsed.

Tam jerked his blade free and sprang to the side of the girl.

"Are you badly hurt?" he asked in English.

She did not understand, but held up both hands to him, a gesture he could not fail to comprehend. He dropped his gory blade and grasping her hands, helped her to her feet. Despite the weight of her armor, she seemed light as a feather. And when she leaned against Tam for support, the crest of her helmet barely reached to his shoulder. Tam repeated his query in Tibetan and Sanskrit. She appeared to understand the latter language and replied in a language that was very much like it—enough to make her speech intelligible to Tam.

"My armor protected me," she said, then added: "I am very thirsty. Let me drink."

With his arm around her slender waist, Tam helped her down the bank, then supported her while she knelt and drank from the stream, using her cupped hands. When she signified that she had enough, he helped her to her feet once more. She seemed greatly refreshed.

Pointing to the split skull of the tiger, she said:

"That was a marvelous stroke. I am beholden to you for my life."

Tam flushed.

"It was nothing," he replied. "A great swordsman taught me, and I have had much practise on the hard skulls of buffaloes."

"Then you are a hunter. Can you find meat for me? I have not eaten for three days, and am faint from hunger."

"I will get you much meat, and quickly," responded Tam. He picked up his yatagan and wiped it on the flank of the tiger. Here was meat, but not of a kind that he could bring himself to eat. Leopards, caracals, ounces, or any other felines were all right for food according to his ideas, but despite Lozong's teaching he could not get over the feeling that tigers were his own kind—that to eat the flesh of one of these beasts would be an act of cannibalism. And it was quite evident that the girl did not consider the beast he had slain fit for food.

"Come with me," he invited.

Together, they leaped the little brook, crossed the grass plot, and entered the bamboo thicket. As they were traversing this, Tam heard the sound for which he had been listening—the discordant cry of a peacock.

"Follow quietly behind me," he said. "There is food."

As he moved silently through the bamboos, he took his bow from the quiver, strung it, and drew forth an arrow. The bow twanged, and a magnificent bird fell to the ground, where it fluttered for a moment, then lay still.

BACK to the brook they went, to pluck, draw and wash the bird, and to build a

cooking fire. Soon they were broiling slabs of peacock breast impaled on

green bamboo over the hot coals.

"It tastes even better than it looks," said the girl as she sampled her first mouthful.

"It is the favorite meat of tigers," replied Tam between mouthfuls, " and they are good judges of meat. They live on it."

"You seem to know a great deal about tigers," said the girl. "Tell me who you are, and more about yourself."

"My name is Tam," he replied, "and I was raised by a white tigress."

"By a white tigress!" she exclaimed. "The prophecy!"

"What prophecy?"

"It is a secret. I should not have mentioned it."

"Never mind," replied Tam, "I'll forget it. Prophecies bore me, anyhow. Tell me who you are, and where you live."

"My name is Nina," she said, "and I live in Iramatri."

"Never heard of that country," said Tam, "but I've heard the name, Nina. She was a goddess, one of the first goddesses, in fact. They worshipped her about five thousand years ago."

"And longer," replied the girl. "Fifty thousand years ago men worshipped Nina."

"There are no records that old," said Tam, "so how could you know that?"

As he spoke, he looked into her eyes. She was regarding him oddly. For some reason a chill ran down his spine.

"Why, you wear a uraeus!" he exclaimed, noticing her serpent diadem for the first time. "Nina was a serpent goddess!"

As he uttered these words her eyes flashed with a strange light like that of the rubies that smoldered in the uraeus. They seemed to burn into his very being, bringing a disconcerting sensation of utter helplessness. He tried to move, to shake off the feeling, but found himself as powerless as if he had suddenly been turned to stone. The meat which he was holding over the coals burned to a crisp, unheeded.

"You know much for a modern earthling," said the girl, finally. "I thought the world had forgotten Nina."

As suddenly as it had come, Tam's feeling of helplessness departed.

"So it has, almost," replied Tam. "She has been worshipped under the names of Ishtar, Isis, Ashtoreth, Tanit and Persephone. As Tanit she still has a few followers in the vicinity of old Carthage, and as Ishtar, superstitions concerning her are preserved throughout the world, though her followers are referred to as witches and wizards."

"She withdrew from the world five thousand years ago," said Nina, "because of the crimes that were committed in her name. Zealots stained her altars with human blood. Parents offered their children to be burned by sadistic priests, thinking to please her. These same priests corrupted her vestal virgins, then, urged by their lust for gold, made brothels of her temples. And when she left the world of earthlings, the priests set up graven images in her place, and called upon the people to worship these in her stead. She could have destroyed them all, but preferred to leave them to work out their own destruction."

"Which they did to perfection," said Tam. "There are ruins scattered around the Mediterranean from Rome to Karnak which testify to that. But tell me, how is it that you know so much about this goddess. Can it be that you-?"

He paused suddenly, as there came to his ears a sound like the roll of distant thunder—or elephants stampeding. The girl heard it at the same time, and they both stood up. Looking out over the waving grass tips, Tam saw, converging toward them, a semicircle of beasts that were larger by far than the biggest elephants he had ever seen. They were twelve to thirteen feet high at the shoulders, and the tops of their massive heads on long, arched necks, were from fifteen to sixteen feet above the ground. They were almost hairless, but protected by skin as thick and leathery as that of the rhinoceros.

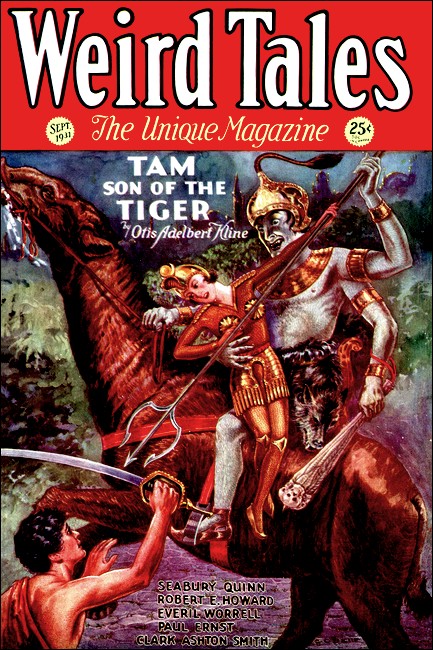

Mounted on these huge beasts were giant riders, terrible of mien and most extraordinary in appearance. At first Tam thought there were two on each beast, but as they drew closer he saw that each rider was of immense size and had two pairs of arms. They were a white race, but pasty white, as if they had never seen sunlight. Each monster carried a long-shafted trident couched like a lance, a bronze mace with a hideous human head graven on the knob, and an immense tulwar, a sword with a curved blade and an elaborate guard. The fourth hand, weaponless, held the reins which guided the giant steed.

The riders wore brazen helmets, flat collars of the same material that represented twining serpents, bangles on their wrists and arms, and the skins of animals wrapped about their loins. One, who seemed to be the leader, wore a magnificent golden helmet decorated with three faces like his own, one on each side and one in the back. In addition to the snake collar, his torso was covered with scale-armor, and he wore a long necklace of white human skulls.

"The gods of India!" exclaimed Tam. "And I thought they had no real existence!"

"Save me! Hide me!" pleaded the girl. And Tam saw in her eyes the same look of horror that had been there when first he saw her. "If I can not escape them, the world—your world—is doomed!"

He took her hand, and together they sprinted for the bamboo thicket. But they had not gone a hundred feet when they were halted by a shower of stones, and there charged out at them from the thicket a mob of hairy, shambling creatures, man-like and yet ape-like. They were armed with slings and clubs, and each carried a bag of large pebbles that hung from a cord around his neck.

"They saw our smoke and sent the Zargs to cut off our retreat before they charged," said the girl. "We are in a trap."

Tam quickly strung his bow, and sent an arrow through the breast of the foremost Zarg. He fell without a sound, and the others paused, but did not cease hurling their stones. By this time the giant riders had come within range. Tam brought down the first of these with an arrow through the left eye. Then he heard a shout from the gold-helmeted leader:

"Dismount, Asoza, and cut down the youth."

A pasty-faced giant, fully eight feet in height, swung down from his high saddle and ran forward, whirling his tulwar and mace until they whistled in the air.

Tam launched an arrow, which glanced from the brazen collar. They he whipped out his yatagan and dah, and awaited the onslaught. As they came together, the giant swung his tulwar in a neck-cut that would have decapitated the youth had it landed. But Tam ducked, and extended his point, wounding his adversary in the groin.

After that they fenced, blade clashing with blade, and Tam was sorely put to it, not only to defend himself from the whistling tulwar but to avoid the smashing blows of the heavy mace.

While he was thus occupied, he saw the golden-helmeted leader swiftly ride up to where the girl stood, stoop, and swing her up in front of him, kicking and struggling. He had been fencing carefully before, but this sight made him reckless. Springing in close, he delivered a savage shoulder cut. His blade bit through the brazen collar, and shearing flesh and bone alike, sliced down through the heart of his adversary.

But he paid for his temerity. The heavy mace, swinging wildly in one of the four flailing hands, collided with the side of his head. There was a brief flash of a million multi-hued sparks, and oblivion.

Left for dead by his strange enemies, Tam comes to his senses only to face

new and undreamed-of perils. Bead of his thrilling adventures in the August

Weird Tales, on sale July 1st.

A vivid novel of thrills and strange happenings, with the very gods of Asia as characters

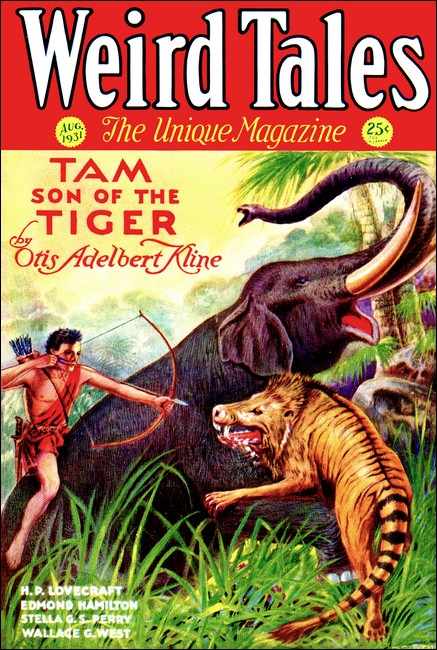

Weird Tales, Aug 1931, with second part of "Tam, Son of the Tiger"

TAM EVANS, two-year-old son of Major Charles Evans, American philanthropist and sportsman, was carried off by a white tigress while his parents were hunting in the Burmese jungle.

The tigress, which had lost three of her four cubs, adopted the boy, and raised him in a pagoda in an old temple ruin that stood in the heart of the jungle. Her remaining cub was Tam's only playmate.

Tam's foster mother had been reared by a lama named Lozong, who had gone on a pilgrimage. Lozong later returned to find the cub full-grown and Tam about half-grown, living and acting exactly like a tiger.

The lama made friends with all three, and being well educated, taught Tam much from his store of knowledge. In his youth he had been a brigand leader and a mighty swordsman, and he also taught the boy to use weapons, particularly the yatagan, a terrible, double-curved sword with which he could cut down a tall tree at a single stroke.

The boy made friends with many jungle creatures, including a huge bull elephant, which he named Ganesha. At the age of twenty, Tam had the strength and bravery of a tiger, an education better than the average, a knowledge of the jungle such as only its creatures possess, and an almost uncanny ability with weapons.

One day Ganesha strayed off into the jungle. Tam, while hunting for him, rescued a beautiful girl in golden armor from a man-eating tiger. Speaking a language which resembled both Sanskrit and Tibetan, both of which Tam understood, she told him her name was Nina, and that she came from a place called Iramatri. She was hungry, and Tam shot a peafowl for her. But while they were cooking it they were attacked by a band of four-armed giants riding on strange beasts larger than elephants, and assisted by a number of hairy, primitive men.

Tam slew one of the hairy men and cut down one of the four-armed giants. But the girl was carried off, while Tam, knocked senseless by a blow from a mace, was left for dead.

WHEN Tam regained consciousness after being knocked out by the terrible, four-armed rider, he felt a blast of hot breath in his face. Looking up, he saw a great shadowy bulk swaying above him. It was Ganesha, the elephant.

The giant bull was shifting his weight from one foot to another, after the manner of his kind, flapping his great ears and, from time to time, throwing bunches of jungle grass over his back to rid it of accumulated insert pests. Presently Tam sat up.

The end of the trunk sniffed at him affectionately for a moment, then, as he grasped it, stiffened, forming a brace by which he drew himself erect. His head ached dully, and touching it with his hand he felt the hair matted with dried blood over a painful bump where the mace had struck.

Suddenly dizzy, he swayed, and would have fallen but for the supporting trunk. But presently his vision cleared, and he was able to look about him. Lying undisturbed where it had fallen, he saw the body of his gigantic enemy.

To his surprize, the sun was just rising over the eastern tree tops. It had been early afternoon when he had fought to save Nina, the beautiful girl in the golden armor. Hence, he had lain unconscious all night. Or had it been but one night? With his jungle training it was easy for him to solve the problem quickly. He knew that Ganesha must have come upon him almost immediately after he had lost his senses, or he and the body of his adversary would have been devoured by the scavengers which quickly scent out dead and wounded animals in the wilds, and that the elephant must have been standing guard over him since that time.

The tracks showed that Ganesha had gone to the little stream twice to drink. In two days of munching the dry jungle grass he would have gone oftener. Tam also noticed the condition of the trampled area about him and the amount of grass which had been devoured. All these signs told him that he had lain unconscious but one night.

Presently, finding that he could stand unsupported, he staggered off toward the little stream. Depositing his weapons and his single scant garment on the bank, he wallowed in the shallow water for a time, drinking and bathing. Ganesha came to join him, and Tam splashed water over his big friend to the latter's manifest enjoyment.

Then, resuming his clothing and weapons, he commanded the elephant to hoist him to his neck, and with his bare feet dangling behind the great, flapping ears, he set out to the northward, riding on the trail of the strange and fearful creatures who had carried off the beautiful Nina.

As he hurried Ganesha along the trail, Tam did not attempt to analyze the reason for his pursuit of Nina's abductors. He only knew that he felt the urge to follow and rescue her—that somehow, though he had never felt that way in the jungle before, he now was strangely lonely. Other than Lozong, she was the only human friend he had found, and it seemed to him that the short hours of their comradeship were the brightest and most interesting of his existence.

FOR six days Tam followed the well-marked trail left by the gigantic mounts

of his enemies. Game was plentiful, and there was forage for the elephant in

abundance, so it was not necessary to make any long stops to secure food. As

he progressed, the trail began to slant toward the northwest. He noticed,