RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Antoine Caron (1521-1959)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Antoine Caron (1521-1959)

"A Mystery of the Pacific," Blackie & Son, Ltd., London, 1899

"A Mystery of the Pacific," Variant Cover

"A Mystery of the Pacific," Blackie & Son, Ltd., London, 1899

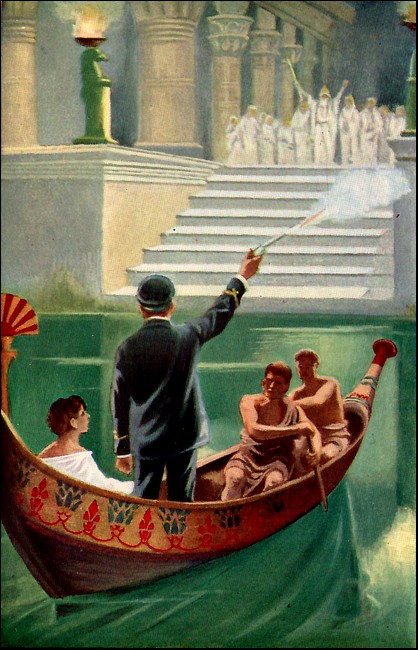

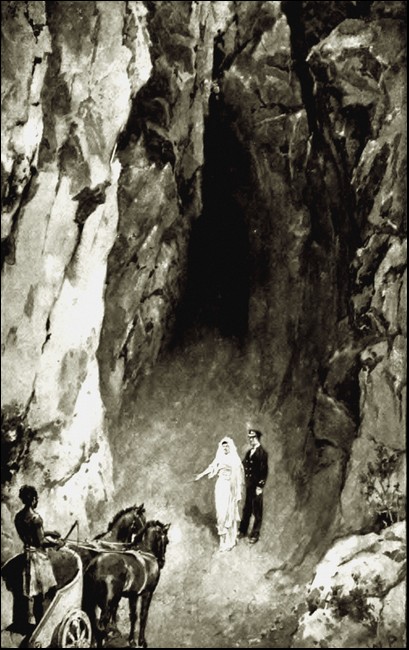

Frontispiece. Saluting the Subterranean City.

SEVERAL years ago, in the good old days of the Queensland Polynesian Labour Trade—instituted, as some of my readers are aware, to provide a supply of Kanakas to work the sugar plantations in that colony—in the good old days of the trade, I say, before the abuses crept into it, and kidnapping replaced honest and voluntary engagement of the islanders of the South Seas, I held the position of government agent or inspector on board the Fitzroy, one of the schooners engaged in the traffic. The situation possessed two of the enviable characteristics of the immortal Circumlocution Office—the salary was liberal and the duties were nominal. The latter consisted mainly in representing the paternal government of Queensland at all engagements of the natives. My instructions when I entered the service, given to me with an appalling amount of periphrasis by the veteran official who then presided over the Colonial Secretary's department, included the onerous duty of seeing that the "boys"—as the islanders are called—clearly realized the provisions of the contract as an entirely voluntary agreement entered into for so many "moons"—usually thirty-six—in return for which they were to receive a fixed amount of wages, including tobacco; also, that when their term of service expired they would be brought back to the island and the particular village whence they had been taken.

We had already made two or three successful trips in the Fitzroy. My cousin, Bob Anstey, our captain, was as fine a seaman and as noble a fellow as ever walked a quarter-deck. By many of his friends and fellow-skippers he was styled "the Bayard of the Pacific". Some of them good-humouredly ridiculed what they designated his "quixotic championship of the nigger." He in turn would retort in the lofty lines of old Whittier, his favourite poet, against the wrong of sneering at—

"the black man, whose sin

Is the curl of his hair and the hue of the skin."

Far from any of the cruelties staining the later annals of the traffic being perpetrated during the visits of his vessel to the islands, he was notoriously lenient and indulgent to the boys, and would have shot down any sailor who attempted to employ force to secure a single recruit. A tight hand and a ready arm were required to keep in check the "anointed ruffians" we were often compelled to employ as sailors. Really good men, with their papers right, would rarely look at the terms of the "labour service," for the wages for seamen were low and the work was heavy and incessant.

Bob's strangely magnetic personality and popularity with all and sundry had carried him hitherto over all difficulties. Skipper Anstey's craft, with its white hull and blue lines, was always welcomed at every island, from the Solomon Group and the savage Marquesas to New Britain and the mysterious Easter Island.

The trite old proverbial copyhead, "Honesty is the best policy," that has come down to us from the old Greek polymath, Pittacus, holds true to-day quite as firmly among the fetish-worshippers of the Pacific as among the ethical casuists of London and Berlin. The islanders of the South Seas could always rely upon receiving a fair price and honourable treatment from "Boss" Anstey, in return for their cargoes of copra and bêche-de-mer. Against his commercial honesty there was no black mark in the unwritten register of the natives. He had never suffered from lapses of memory as to payment as soon as he had the cargoes under hatches, nor shown a clean pair of heels in place of either coin or kind. The outrages in the South Seas which our missionaries and missionary societies are ever and anon eloquently bewailing, were never the result of his unchristian swindling of the "gentle" savage. They were due to the deceit perpetrated by other captains, whose Christian practice was often in inverse proportion to the volubility of their profession.

In October, 1877, we left Brisbane, upon what was destined to be our last voyage, amid the usual felicitations and wishes of bon voyage from the owners of the Fitzroy (in which, by the way, Anstey held a share) and our skipper's numerous friends. Apparently our company held it truth with Praed, who sings:—

"I think I have as warm a heart

As friend to friend can be,

So another bumper ere we part—

Old wine, old wine for me!"

For champagne and claret corks popped freely as the trim, taut little schooner was being towed by the tug Gannet down the Brisbane River. Two or three of the sugar-planters for whom we were procuring the Kanaka recruits, a friend of Professor Barlow's—the Professor was taking a trip with us to pursue certain ethnological studies—a journalist or two, besides Messrs. Laffit and Jolliboy (the firm of owners), and some of Bob's friends, were on board, intending to proceed as far as the Pile Lighthouse, where we would "cast off" the tug, in which they would return to town.

Little did we think that some of us at least would never see the old shores again, as we dropped slowly down the winding reaches of the beautiful river on that deliciously clear evening in the fair colonial springtide, when the very atmosphere was redolent with sweet, subtle odours of magnolia, gardenia, and other semi-tropical flowers, as well as of new-mown hay, wafted to us from the little farms on the banks. The great glad world around us was teeming with the countless myriads of that multiform life visible under the Southern Cross.

Trouble oft comes with the swiftness of lightning out of a blue sky, sings the Persian poet Firdausi. Scarce were the adieux and the well-wishes of our friends spoken and our sails set when our cares commenced. Bob's proverbial luck deserted him. Verily, as in the case of Ulysses, it seemed as if the favour shown to him hitherto by some of the gods had, in an inexplicable way, aroused the jealousy of the others, for he was now to experience frowns in place of smiles.

Our crew consisted of twelve men all told. They were a rather worse lot than usual. We had not lost sight of the sandy coast-bluffs of Queensland more than twenty hours, and were running down our "Eastings" before a fine westerly breeze blowing fresh off the land, when notice was brought aft by the steward to the mate, Mr. Rodgers, that one of the men in his watch had been seized with a mysterious ailment. Rodgers, who was a first-rate seaman after the skipper's own heart, went to the fo'c's'le without delay to see the sufferer. Presently he returned with a rather grave and troubled face. Professor Barlow, Anstey, and I were seated on the poop conveniently near the wheel, that Bob might keep an eye on the course until we got well clear of the land. They were discussing the moral and intellectual status of the Australian aborigines, while I was reading a smart article in the Athenaeum on George Eliot's Daniel Deronda, but listening ever and anon to scraps of the conversation. The Professor was adducing certain facts he had collected to demolish the theories of the existing ethnological schools relative to the assumed debasement of the race.

Rodgers joined us, and deprecating so abruptly interrupting Barlow, asked the Captain if he had any laudanum on board. The skipper replied in the affirmative, and inquired what was wrong.

"I hardly know what is wrong," replied the mate. "Bill Adams, one of the best men in my watch, and, next to the bo'sun, the most reliable hand on board, has been seized with the most excruciating pains in his stomach. He has become quite black in some places, and is swelling terribly in all his extremities."

While Captain Bob went to get the laudanum the Professor turned to the mate, saying:

"Can I be of any use to you? I have devoted myself to the study of medicine for many years past. Perhaps I might be able to do the poor fellow some good."

Rodgers eagerly accepted the offer. The time hanging heavily on my hands, I thought I might as well accompany them to the forecastle. The skipper joined us with the bottle of laudanum in his hand, and we all walked "forrard."

As we neared the fore part of the vessel, we were saluted by the most pitiful moans it has ever been my fortune to hear. Adams was certainly in mortal anguish. His whole body was covered with profuse perspiration, induced by the physical torture through which he was passing. Deep black lines were already apparent beneath his eyes, and the eye-balls themselves seemed starting from their sockets. He was in a state of semi-coma, only recognizing us at intervals. Several of the mates of his watch were standing around endeavouring to alleviate his pain, but seemingly realizing their helplessness.

The Professor, as he entered, uttered a hasty exclamation, and walked quickly over to the bunk of the sick man. After taking the temperature of the sufferer, raising his eyelids to see whether the pupils were dilated, opening his mouth to examine his tongue, the Professor turned to the skipper and said:

"Captain Anstey, this man is suffering from the effects of an irritant poison, administered within the past three or four hours. At first I thought the symptoms were those of antimony, but now I am convinced something else has been mingled with it. The spasmodic contortions of the body suggest strychnine, but there are other symptoms indicative of arsenic. Singularly, and most unhappily for us, the patient has not retched at all, and I must now try to make him do so, though I may as well say I fear the case is hopeless."

"Then, doctor, if the case is hopeless, what's the use of troublin' him ter make him retch?"

It was one of the men who spoke, a swarthy, sinister-looking Irish-American, big and burly enough in physique, but who carried the word "villain" writ large on his features.

"To discover the scoundrel who has administered this poison, for that this is a case of either accident or suicide I cannot believe," replied the Professor, eyeing his questioner so steadily and closely that he slunk away behind his fellows.

At this moment the shadow of an overwhelming trouble seemed to descend over Captain Bob. His face became pale as marble, but as impassive. Turning to Rodgers I heard him remark in a low, hurried tone, "Quick, lock up the armoury, bring two or three loaded revolvers." Then in a louder tone, to be heard by all, "You will find it in a green bottle in my cabin." In an instant Rodgers was gone, and, as events proved, it was well the precaution was taken. A few minutes afterwards Adams revived a little, and opening his eyes, noticed the captain by his side. Beckoning him to bend down over him, the sick man made an effort to say something, in which the words "Poisoned—wouldn't agree—plot—mutiny—seize ship—piracy," were alone distinguishable.

Suddenly the captain was with scant ceremony pushed aside, and a hoarse voice said:

"'Axin' parding, cap'n, but I knows his ways. Here I be, mate; here's old Joss; I won't leave yez. Och, but poor old Bill's mind's away agin; he don't know his best friends."

The latter part of the speech was occasioned by a look of unutterable horror which flashed into the dying man's features at the sight of the evil-looking Irish-American who called himself Joss.

What more might have passed can only be surmised, but at this moment the Professor turned swiftly round to Joss, and, pulling a small but deadly-looking revolver from the breast of his coat, pointed it directly at his head.

"Jake Huggins, alias Joss Ramage, hands up! I charge you with the attempted murder of William Adams, and with a plot to mutiny and seize this ship."

For a moment the villain was dumb-foundered at the discovery of his plot, but, recovering himself, he shouted to the "watch on deck", "To the armoury, boys; snaffle the shooting-irons, for the gaff's blown!" making at the same time an attempt to rush from the forecastle to join his confederates, who were beginning to gather round the door.

The Professor, albeit a scientist, and likely to be more familiar with gases than gunpowder, and with the theoretic course of the bullet as governed by the laws controlling projection, than with accuracy of aim, was as cool and determined a man as ever lived. He had calculated every chance before he took the overt step he did. He therefore hesitated now not for an instant, but fired point-blank at Huggins, who fell at his feet with a deep groan. A loaded revolver slipped at the same time from his grasp, and Captain Bob at once appropriated the weapon. At the same moment also the mate and bo'sun, a thoroughly reliable man, whom Rodgers had taken into his confidence, appeared, heavily armed, and driving the watch on deck before them like a flock of sheep, the man at the wheel having been cautioned, as he valued his life, to remain at his place, and keep the vessel's head to her course.

The combat, if such it could be called, was over almost immediately. The two other ringleaders, disheartened by the fall of Huggins, submitted to the inevitable, and surrendered at discretion. They were at once placed in irons, while the body of the leader, sewn in a shroud with a couple of shot at his feet, was thrown overboard without more ado.

Poor Adams only lived another hour. The Professor was confident that, had he been informed of his seizure earlier, he could have saved him. Huggins, however, had put off summoning assistance until the poor fellow was in articulo mortis. Another of the men exhibited signs of having been marked out for the same fate. But Professor Barlow, by strong antidotes, was enabled to counteract the effect of the poison. He was convinced, by further examination, that the basic poison, or that administered in the largest quantities, had been strychnine. For some considerable time he had been engaged in the study of toxicology, particularly with relation to snakebite, and had verified the brilliant discovery of Dr. Mueller, of Yackandandah, that strychnine is an infallible specific for the bite of even the most venomous of reptiles.

With the true scientist's power of reasoning by analogy, he argued that if strychnine possesses the power of rendering innocuous the toxic principle present in the fangs of a snake, that toxic principle inversely should prove an antidote to strychnine. With infinite trouble he had collected a small phialful of the fluid extracted from the poison-bag of numerous snakes, in order to subject it to chemical analysis.

As soon, therefore, as the second sufferer was seized, Barlow administered two minims of the latter poison to him. In two hours' time, save for an overpowering feeling of nausea, the man was free from pain; in twelve he was at work. The success of the experiment was complete.

Meantime the skipper and the mate were investigating the plot to mutiny and seize the ship. Of this, Huggins appeared to have been the Arch-Diabolus. His design had been deliberately planned, and as deliberately put into practice. Along with two accomplices, he was to ship on board the Fitzroy, and endeavour to win the crew over to their scheme. In this, by threats and cajolery, he seemed to have been successful. Only in the case of Adams and Robb had he failed. They had been faithful to their trust, and declined to have anything to do with the matter, threatening, were it prosecuted further, to reveal all to the mate. This difficulty, so unexpected, had rather staggered Huggins, and he therefore determined to remove them by poison. The revelation that poison had been used was likewise a surprise to the conspirators. That the Professor would know anything of toxicology had never entered into their calculations, and his swift, sudden recognition of Huggins, notwithstanding his elaborate disguise, thoroughly disconcerted the scoundrel.

Professor Barlow afterwards supplied the remaining links of the story. Huggins he had known in America as a wrecker and bully of the worst type. The evening previous to the outbreak he had been lying in one of the boats taking some lunar observations. He was completely concealed from the view of all on deck.

Presently Huggins and two other men belonging to the watch on deck approached, and, leaning over the bulwarks, immediately under the davits supporting the boat wherein Barlow lay, commenced to talk of the plot. The arch-conspirator had completely won the men over to his plans, which he was recounting for their special information, so that the Professor was placed in possession of all. Of poisoning Adams and Robb, however, no mention was made, although the threat was used that if they did not yield they would rue it.

The Professor at once communicated to the captain what he had heard. They both determined to be on their guard and await developments, informing Rodgers of the affair. The sacrifice of poor Adams' life, however, brought matters to a crisis, and at a signal from Captain Bob, the Professor had acted in the way he did. When they came to overhaul the effects of Huggins and his two accomplices, they gained some idea of the object of the plot, to account for which had previously puzzled both the captain and the Professor. In Huggins' chest was found a bottle, evidently a message from the sea, the contents of which were such as to cause them the utmost surprise. The bottle itself had apparently been a considerable time in the water, as the glass was encrusted with minute shell-fish and withered sea-weed.

Inside they discovered a paper on which was inscribed in faded, rusty-red characters, the following words, a considerable portion of them being quite undecipherable through damp:—

"L.t 27°13' S., L....111° 17' W. Is..e...Spirits, Tu..day 12th Fe....ry 18.. The fo.rth y.ar.... residenc...dreary island...home..kin...love...God....Christ come...help....five castaway Englishm... gold.. treasu.es, precious... tempt ... here... abundan....make...wealthy,....dreams of... men...come...no . elay ...end. ord. Mary We...ter Com..cial Ro.d, Lei.h, whoever fi....his, and .od.r...ard.y...

"John Webster, 1.te ma..er..ec..ed..rig Emily Hope ...n. Gib..n ma.e...son, bo's.. Tho....ret, sa.l..Jo..Ric..ds, sail.r."

To decipher the letter was a work of some difficulty, owing to the action of the brine in eating away the paper—evidently a leaf out of an old note-book.

The characters also, originally written in blood, were so faint as to be well-nigh illegible. However, after a time I succeeded, in accordance with the captain's request, in piecing together the epistle, supplying what was awanting from the connection supplied by the context. The full text of the message then read as follows:—

"L(a)t. 27° 13' S., L(ong.) 111° 17' W., Is(l)e (of) Spirits, Tu(es)day, 12th Fe(brua)ry 18 (year impossible to decipher). The fo(u)rth y(e)ar (of our) residenc(e in this) dreary island (far from) home (and) kin(dred). (For the) love (of) God (and of his Son Jesus) Christ come (to the) help (of) five castaway Englishm(en). (If) gold (together with) treasu(r)es (and) precious (stones can) tempt (any one to come) here (there is) abundan(ce to) make (any one) wealthy (beyond the) dreams of (avarice). Men (we entreat you?) come (to our help, make) no (d)elay. (S)end (w)ord (to) Mary We(bs)ter Com(mer)cial Ro(a)d, Lei(t)h, whoever fi(nds) this, and (G)od (will) r(ew)ard y(ou). John Webster, l(a)te ma(st)er, (wr)ec(k)ed (b)rig Emily Hope.—Gib(so)n, ma(t)e—(names illegible of bos'un and sailors, the last names, perhaps, John Richards or Richardson)."

LYING alongside the bottle containing so pitiful a cry for help from the trackless ocean, was a bundle of letters and papers referring to it. From these the fact became apparent that Huggins' cupidity, not his humanity, had been excited by the information. To proceed to the spot indicated was evidently his intention as soon as he had obtained facilities for so doing.

Not, however, to rescue the unfortunate castaways! With him as with the buccaneers of the seventeenth century, life ranked as a bagatelle compared with that precious metal, of which its bard Tom Hood sings:—

"Gold! Gold! Gold! Gold!

Bright and yellow, hard and cold,

Heavy to get, and light to hold;

Price of many a crime untold.

For gold they lived, and they died for gold;

How widely its agencies vary!"

Calculations as to the exact position of the Isle of Spirits, letters in reply to some of his, urging men to join in an attempt to secure the treasure, an epistle half written addressed to one Joseph Parslow, exhorting him to make every effort to ship on board the Fitzroy, as she was a vessel suitable for their purpose, and stating the fact that "circumstances" might render it necessary for "five" of those on board "to join the majority" without delay, were all discovered, with many other odds and ends, among the papers of this finished and pitiless scoundrel.

On our showing what had been discovered to Professor Barlow, to our surprise he betrayed signs of an uncontrollable emotion. His features blanched until they assumed the colour of parchment. Staggering back until he stumbled against the bulwarks, he ejaculated in a hollow tone, gazing at the paper meantime as if on the lineaments of some frightful spectre, "My God, my sister's long-lost husband—John Webster—Emily Hope!"

Captain Bob, with his usual sympathetic kindness, tried to console him by suggesting that, as the paper showed signs of having been in the water for a considerable period, the castaways had probably already been rescued. But against this suggestion, the keen, logical mind of the Professor instantly balanced the negative probabilities of the case. "That may be so," he replied, "but with equal force it may not. Captain Anstey, Heaven has prospered me as far as this world is concerned. I am what people call a wealthy man. Now, I offer you whatever sum you choose to name, to bear down into the latitudes mentioned in the message, and to see if my brother-in-law is still there."

"Did it rest alone with me, Professor," said the manly British seaman, "no inducement would be needed to stimulate me to crowd on every stitch of canvas I possess, and to proceed as quickly as possible to the rescue of my fellow-men. But I have my fellow-owners, Messrs. Laffit and Jolliboy, to consider, as well as the underwriters. Not that they would not agree with me in hurrying the vessel to the rescue of the castaways, But they are not here to give their opinion."

"Name your price, name your price; or, stay, let me buy the vessel right out," said the Professor, "including a sum representing the possible profits of the trip."

"Perhaps that would be the quickest and the surest way out of the difficulty; we, of course, buying it back from you at the same figure when you have completed your search."

The Professor assented. Summoning Rodgers and myself to act as witnesses, Captain Anstey and Barlow descended into the main cabin, and there an agreement was drawn up, whereby, for the sum of £3000 plus £800 (as representing the possible profits of the trip), the latter became possessor of the schooner Fitzroy, together with all her belongings. To this, a detailed statement was also appended, setting forth the reasons for the transaction for the information of the Government. To this document our signatures were affixed, and all on board straightway became the servants of Ernest Barlow, by virtue of the cheque drawn by him in favour of the Captain and Messrs Laffit and Jolliboy, and deposited in the ship's safe.

"Now, gentlemen, a glass of wine to seal our bargain. Steward, a bottle of that old 'Three Star' Hennessey you crack up so much," cried the Professor. "Now, skipper, here's to our success, make the little girl show her heels to the wind. Crowd on your canvas. Every damage you sustain will be made good. Remember my brother-in-law's life and those of his men may depend on our expedition."

Captain Bob cheerfully responded to the Professor's toast. That every expedition would be used he assured him, and as the wind continued favourable the progress was all that could be desired. Yet we could see that, excellent though the record achieved might be, it was much too slow to keep pace with the lightning course of the Professor's anxiety. While he was constantly quoting as a sort of oral anodyne for the gnawing anguish of his suspense, the beautiful lines in the Helena of Euripides, where the chorus advises the unfortunate daughter of "Leda"—"Never with presaging mind to anticipate evils to come,"—we could note that the unuttered apprehensions outweighed the unction he fain would lay to his soul.

Captain Bob had assured the Professor that, taking the distance at about 2200 miles from the position of the vessel at the date of the discovery of the letter, to the exact spot in the Pacific Ocean mentioned as the locale of the so-called Isle of Spirits—a point, however, marked on none of the Admiralty Charts as occupied by any land whatsoever—the duration of the voyage could not, under the most favourable circumstances, be less than twenty-six days. Though an average rate of progress, registering six knots an hour, might be maintained in many places, allowance had to be made for calms, currents, baffling and head winds, and the like.

The Professor reiterated his full conviction of Captain Bob's anxiety to reduce the term of the Fitzroy's run to a minimum. He assured us of his intention to possess his soul in patience, to employ the time in pursuing his studies, with other determinations of a philosophical and laudable character.

But of all servitors a truant attention is the most intractable. Easier it is to preach than to practise patience, or, as good Adriana in the Comedy of Errors says, "They can be meek that have no other cause." Professor Barlow's endeavour to fulfil the Scriptural injunction to possess his soul in patience had much in common with the illustrious exemplification of the same virtue by that paragon of patience, Sir Fretful Plagiary.

Long before the twenty-six days of the estimated term had run their course, the Professor's anxiety had broken down the rigid barriers of an Englishman's natural reserve, and that mask of unemotional callousness modern society pronounces comme il faut. More than once a suspicious glistening was perceptible in the Professor's eyes. But the sun is very trying to the eyes in those latitudes, and the Professor always blew his nose with remarkable vigour on such occasions. But as the longest lane must have its turning, the dreariest day its end, so the voyage of the Fitzroy to the mysterious Isle of Spirits at last approached its termination. Captain Bob had privately confided to me his opinion that an error had been made in Captain Webster's observations. "Could it be possible," he reasoned, "that the numberless American, colonial, and British ships passing this way would not have discovered and reported land at a point where neither the Admiralty, nor the French, nor even, for that matter, the Dutch charts, imperfect though they be, mark a rood of the barrenest rock ever sea-fowl settled on? He must have landed on Elizabeth Island or Ducie Island, or perhaps on Easter Island, which, God knows, is mysterious enough to satisfy the biggest glutton for mystery and supernaturalism the Psychical Society ever acknowledged as an emissary. But not a word to the Professor; poor soul, he is worried enough already. Let him hug his illusions a little longer."

At last we reached the twenty-sixth day, on which Bob had given it as his opinion we ought to sight the Isle of Spirits. Our voyage had been prosecuted under the most favourable circumstances, both as regards wind and currents, but not a trace of land appeared on any quarter. In vain did the Professor scan the horizon all round with his powerful telescope. Twelve o'clock arrived, when the skipper took his observation. "In five hours," said he, "we ought to cross your brother-in-law's line of observation; but, as you see, there is no land in sight."

The Professor said nothing; the deepening of the lines of anxiety on his forehead was the only reply. The wind meantime had died away to the lightest possible breeze.

Suddenly Mr. Rodgers, the mate, who was standing at the bow of the vessel, reported huge masses of sea-weed extending for miles right across the direct course of the ship, and barring progress.

"Humph—funny!" grunted Bob; "we are thousands of miles away from the Sargasso Sea, and I never heard of such belts of weed in these latitudes."

The Fitzroy drove directly on to the bed. She passed the outer edge without much perceptible hindrance, but a few seconds afterwards was lying perfectly stationary, rolling like a log amidst an immense mass of tangled black seaweed, offering an obstinate resistance to her further course.

"Confound the thing!" cried the skipper. "'Bout ship! What can it mean? Long as I have sailed these waters—and I may safely say I have been a dozen times in this very latitude—I never saw anything like this before. Lower the jolly-boat, Mr. Rodgers, while we are making this tack, and take a look round if you can see any break in the weed."

After some little difficulty in getting the vessel set to her new course, Mr. Rodgers fulfilled the captain's instructions. We watched him and his men skirting the edge of the huge bed for more than a mile. Then they appeared to turn suddenly at right angles into the sea-weed, and the boat, now a speck, seemed swept up some opening with considerable velocity. After proceeding into the heaving mass for some hundreds of yards, we saw them turn and endeavour to retrace their course back to the ship. But the task proved no easy one. They evidently were battling against a current, whose tendency was to sweep them further into the heart of the weed-bed. Bit by bit, however, they won their way out, and at last we saw them emerge from the tangled mass of black snaky feelers and row towards us.

Their arrival was now awaited with anxiety.

On coming aboard again, the mate reported that about a mile and a half on the port side there was a break in the sea-weed, in the form of a channel about fifteen yards wide. But, singularly enough, down this open space ran a current of not less, he was convinced, than from three to four knots. As far as he could see, the channel stretched for miles into the heart of the weed-bed. Of the latter there seemed positively no termination whatever.

"Well, Professor, what do you wish us to do?" asked Bob.

"I wish you, Captain, to run the vessel into that channel, and to sail through it. As I am a living man, I believe that behind this vast bed lies the Isle of Spirits, where my poor brother-in-law is. But, stay—there may be dangers here altogether foreign to the ordinary perils incident to a mariner's life. Will you, as captain, announce to the men, that to every one on board I will guarantee a bonus of 20 per cent on the aggregate amount of their yearly, not their monthly, wages if they will stick to me?"

"Oh, that is not needed, Professor," said the Captain dissuadingly. "Your previous generosity in raising the wages of all on board would stimulate every one to do his best to assist you in your quest."

"Never mind, skipper; do as I wish, please, and let them all understand that he who obliges me in this will not find me ungrateful."

From the cold reserved Professor this meant much. Anstey said no more. He bowed, and proceeded to execute the order.

In a short time the Fitzroy, albeit hampered by the light wind, was heading direct for the break in the wide expanse of algae indicated by Rodgers, who was personally acting as "lookout" in the bow of the vessel. Ere long we passed between the two outlying "capes" of weed marking the entrance. Scarcely had the ship entered the so-called channel than she experienced the force of the current referred to by the mate. Her rate of progress was perceptibly accelerated, while as we were now moving more rapidly than the wind, the sails were flapping idly against the mast.

The scene around us was weird and strange in the extreme. To some vast lake, whose surface was covered with water-lilies prior to flowering, as well as with other aquatic plants and weeds, the entire expanse of ocean, far as the eye could see on every side, bore close resemblance. In place of its bosom presenting a shimmering mirror, blue as the cerulean heavens above, it exhibited a dreary monotonous waste of brownish-black tendrils or streamers, bobbing their knotted and knobbed "ganglia" at times above the surface, but generally covered by a thin layer of water, so that they were ever floating and swaying and twisting and turning on that surface, like myriads of octopi stretching out black horrible tentacles to suck down any hapless being that fell amongst them. Even the proverbial "waste of waters" was preferable to this terrible spectacle.

But the channel through which we were passing showed no signs of narrowing, nor did the current decrease in velocity. For considerably over three hours we had been carried along by it without experiencing any sign of slackening speed. Thrice had Captain Anstey ordered the lead to be heaved, receiving as a response—20—18—22 fathoms respectively.

Professor Barlow's excitement increased every hour. His agitation had become well-nigh uncontrollable. Ceaselessly he paced the poop, stopping every few minutes to sweep the horizon line anew with his glass. Pale as parchment were his features. To no one did he address himself, and all respected the silence he evidently desired to preserve.

Suddenly, as afternoon was deepening into evening, and the shadows lengthening, the startling cry, "Land ho!" rang from the cage at the mast-head, where Captain Anstey had posted a sailor as "look-out ."

The effect upon every one on board was electrical.

"Where away?" cried the skipper, startled out of his apathy.

"Low down on the starboard bow; but there is a mist or something hanging over it, so that you can't make it out clearly."

The skipper and the Professor at once proceeded to the mast-head. With the aid of the strong telescope of the latter the fact was established beyond a doubt that, be it of large or small extent, land certainly lay in the direction indicated. Before long it was visible even from the poop as a low dark line on the horizon.

Over all else hung a heavy pall of cloud or mist. To the Professor, however, what was revealed was sufficient. That the land before him was the Isle of Spirits he entertained not a doubt. His gloom disappeared in an instant, and in his satisfaction he was inclined to gently rally Captain Anstey on his incredulity.

"Well, Professor, I must own I am in the wrong. But I may say this, that, old sailor as I am, I never heard of land lying in this precise latitude before. I grant the Pacific is most imperfectly laid down as yet by hydrographic survey, and that there are hundreds of miles of water in these archipelagoes into which no vessel of any size dare enter, owing to the difficulties of navigation from the coral reels. Still the existence of this island is a mystery."

"My dear Anstey, you were right when you said the Pacific is most imperfectly surveyed. Still, I imagine that the difficulty meeting us this morning in the vast algae beds, has been the main cause of deterring other vessels from running down here. They have not been so fortunate in striking this channel."

"Nay, even if they did find it, not one man in a thousand would dare to venture down it. I warn you it will need a tidy cap of wind to take us out again, unless this current finds an outlet elsewhere, after skirting the island, and will do us the same kind office in carrying us out as it is now doing in bearing us in."

But to the Professor any warning meantime fell on deaf ears. To solve a family mystery, overshadowing with the deep pall of sorrow the life of his youngest and favourite sister, and rendered even more acute because of the uncertainty attending the fate of the loved one, was at present his one absorbing purpose. Humanity exhibited towards one object may, when carried to excess, unwittingly involve gross cruelty towards others. This was exactly our present situation. His natural affection towards his sister blinded the Professor to the overwhelming danger threatening the entire ship's company, in thus running recklessly upon an unknown coast.

THAT the Captain apprehended to the full the perils of the case, I could detect in his troubled look and restless demeanour. With the anxiety of Professor Barlow to solve the pending doubt as to the fate of his brother-in-law, he had too keen a sympathy to permit him to say anything. But all that a bold and skilful British seaman could do to ensure safety for us he did.

To the island we were now steadily approaching, and its outlines were beginning to stand forth in bolder relief against the glowing amethyst and orange hues of the evening skies. The shimmering radiance of the dying day was rapidly merging into the deeper shades of the coming night. This fact, however, occasioned but slight apprehension, as, ere long, the moon, then at its full, would arise and afford us abundant light. The mists enveloping the land had rolled away like the curtain of a panorama, and disclosed to us an island of considerable size, to judge of the whole by the part presenting itself to our view. Though still a long distance from the shore, we could perceive the physical characteristics of it to be mountainous; successive ranges of hills rising tier above tier behind one another, until they culminated in one supreme and solitary peak, partially snow-clad and loftily sublime, at whose summit, amidst the darkling shadows of the night, gleamed the sullen, steady glow of a semi-active volcano. To the steamy smoke, rising as it did in white, sulphurous volumes from the cone, were due the clouds and the vapours enveloping the island when viewed from afar.

The Professor was in ecstasies. In his quest, he had struck upon a veritable terra incognita, a rare experience in this age of persistent "globetrotting," when a man's reputation as a traveller rests not on his ability to reproduce the scenes through which he has passed, but on the aggregate amount of the world's surface he has covered in his peregrinations. The Professor at once proceeded to christen the volcano "Mount Anstey," in honour of our captain.

Darkness had now fallen over the scene, rendering everything more weird and unearthly, as seen in the dull red light cast in fitful flashes from the distant crater. Presently, however, over the north-eastern shoulder of the mountain the moon began to arise in all its peaceful silvery radiance; while afar off lights were peeping out like flitting fire-flies from the shore, evincing that the island was at least inhabited, though by whom remained to be seen.

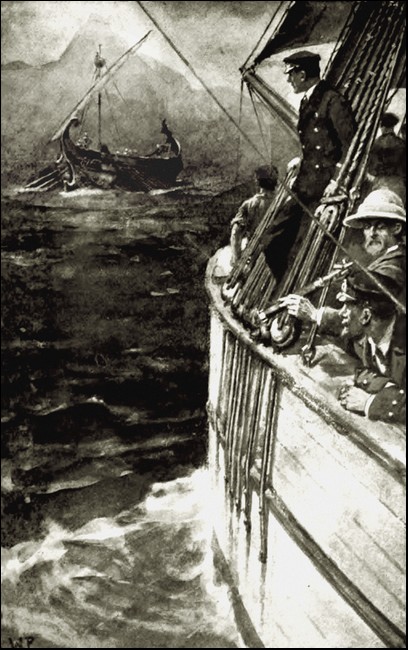

While speculating on this, we were startled by another cry from the look-out, "Sail on the port bow!" A sail!—surely not? Another rush to the side. But the "look-out" was right. There, bearing down upon us, out of the semi-gloom of that side of the island lying under the shadow of the towering mountain, and, therefore, not yet illumined by the rising moon, gleamed what seemed to be the white sails of a vessel. She was approaching us with great rapidity, albeit travelling against the current. Nearer we drew to each other. Now she emerged out of the deep gloom cast over the waters by the mountain ranges into the tremulous argent sheen gradually being suffused over the scene by "Cynthia in all her beauty."

"Good heavens! what kind of a craft is she?" cried the skipper, in a tone of utter astonishment. The sentiment was re-echoed by us all. At both stem and stern were curious voluted figure-heads; while her bulwarks stood high out of the water. She carried only one mast, on the low yards of which hung one vast, broad sail, in size and shape resembling a lateen sail, but at present clewed up into a single reef. Her breadth of beam, and quaint, high poop also attracted notice; but what most of all excited our surprise was the fact that, although a vessel of about 100 or 150 tons burden, she was propelled by three banks of oars, placed in an oblique order above each other on either side.

At last, when she was about three hundred yards distant from us, the Professor, who had been attentively examining her through his telescope, broke silence with the words,—

"As I live, a Roman trireme, complete in every detail!" uttered in a tone of the most profound astonishment.

"As I live, a Roman trireme!"

"What do you say, Professor?" said the captain.

"I remarked that the vessel approaching us is a facsimile, in every detail, of a Roman galley or trireme of the age of the early Caesars. What it all means I cannot say."

Presently, in response to some order, the rowers on board the galley ceased pulling, and were evidently waiting for us to approach.

Captain Anstey was, however, determined to err on the safe side.

"Bring up a rifle or two from the armoury," he said to the mate. "Let each man carry his revolver in readiness; whether they be friendly or hostile, it is well to be prepared."

At length, when we came within hailing distance, there advanced to the side of the galley a picturesque figure, attired in a helmet and cuirass of some highly-polished metal, a coat or kilt of chain-mail reaching well-nigh to the knee, and greaves covering the legs from the knee to the ankle. He was armed with a short sword, held drawn in his right hand, while on the left arm rested a small circular shield with metal "bosses." In fact, his whole accoutrements reminded me of the illustrations in those highly-esteemed volumes, familiar enough in my school and college days in "Auld Reekie"—Dr. Smith's Dictionary of Antiquities and History of Rome.

Our surprise over the occurrences of this eventful night was rapidly deepening into the profoundest amazement. Was it possible that the customs in vogue in the Rome of the Caesars could be existent in the nineteenth century away out in the semi-tropical Pacific? The whole matter appeared an enigma of the most perplexing character. To say it was deepened would be to convey only the faintest possible conception of the thrill of astonishment vibrating through our minds, when across the channel separating the two vessels came the accents of that tongue, which, though now ranking among the dead languages of the earth, had been the current speech of that mighty empire, the stateliest and the most imposing the world has known—

"Quae navis est? Estisne amici aut hostes?" But the Professor, in proportion as the mystery became more inexplicable, rose to the occasion. In his Oxford days he had been famous for the purity and felicity of his Latinity. On him, therefore, the task of conversing with the strangers in the language of old Rome naturally devolved, and was a delight. Without hesitation he replied in their own tongue—

"This is the ship Fitzroy; we come as friends, seeking friends who are thought to have suffered shipwreck here."

"You and yours, then, are welcome to Nova Sicilia. Publius Manlius Torquatus, and Caius Flaminius Piso, the consuls, have commissioned me to meet you to inquire your errand, and if ye came in peace, to bid you welcome in the name of the Republic," was the response.

"In the name of my friends and myself I thank you. We are anxious to cast anchor. Where may this be done with safety?"

"This trireme will conduct you to a convenient anchorage in the harbour, if you will accompany us. It lies about sixteen stadia from the present spot. At about half that distance the current now carrying you along takes a turn to the right, and skirts the southern shores of the island. Our principal town, Nova Messana, lies a little to the north. You will therefore require to get out your oars, and leave what we call the 'stream', so as to strike over the bay to the harbour."

A puzzled man was good Captain Anstey when the information given by the stranger was translated to him.

"God bless the fellow, how the mischief can I get out of this stream, as he calls it now, when there is not as much wind as would fill your hat? Get out my oars! the man must be a blooming chucklehead! What kind of oars would a 400-ton schooner carry, does he think? No, Professor, the only thing to be done is that the gentleman in the tin hat should order his trythingumyjig to take us in tow. By the powers, what have I come to, when my trim little craft has to be taken in tow by an outlandish cockle-boat like that!"

"My dear Captain Anstey, it is a genuine Roman trireme, and those apparently are descendants of the ancient Romans, though how in the name of wonder they got here goodness only knows."

Poor Captain Bob muttered something about not caring much whether it was a "try-ream" or a "try-quire;" he didn't like the business any the more. However, the Professor, having hailed the stranger—who, by the way, informed him that his name was Quintus Calpurnius Lepidus—explained the difficulty to him. Apparently, the unwonted characteristics of our party were occasioning quite as much astonishment on board the galley as theirs among us. Lepidus having held a hurried consultation with some of his companions, signified their willingness to take us in tow, but seemed at a loss to understand how it was to be managed.

"Oh, that's a simple matter," cried Captain Anstey. "Bo'sun, take the jolly-boat and a couple of men, and carry a cable line aboard that—that—what the dickens d'ye call it, Professor?"

The honest bo'sun, Job Simpson, one of the most faithful souls on earth, to whom an order represented a command to be carried out at all costs, nevertheless did not relish his mission. He muttered some words about "not liking the cut o' the jib o' them there furrineerin' blokes," but at once proceeded to execute his mission. With evident surprise, those on board the galley observed the three men in the boat first being lowered from the davits, then proceeding to the bow of the schooner to take up the tow-line.

But the climax of honest Job's experience was attained when he reached the side of the galley, and, looking through one of the oar-ports, observed some of the rowers (usually slaves or criminals in the days of Rome) eyeing him very attentively. To Job all "furrineerin' fellers" had some subtle connection with Frenchmen. Only natural, then, was it that the good sailor should address them, as he considered, in appropriate terms:

"Axin' yer parding, mounseers, I ain't acquaint with yer parley-vous, but would yez jist kitch a hold o' this here line?"

But not a sign of acquiescence was vouchsafed.

"Drat the fellers! Are they all deaf and dumb, think yez, boys? I'm sayin', mounseers, if yer honours would just lay hold o' this here line it would be a great obleegement."

Still not a sign from those whom he addressed, only sounds of suppressed laughter.

"Gosh, here's a mess! either all these bloomin' coves are stone deaf or they can't understand a word o' good English. I'm sayin', mounseer—"

But here the Professor, who, with Captain Anstey, had been watching the efforts of Job with some little amusement, interposed, and directed the attention of Lepidus to what was desired. The line was at once taken on board over the stern of the galley and fastened securely. Presently the trireme began to forge slowly ahead with the schooner in her wake.

At this point the channel perceptibly widened, until it attained a width considerably over 100 yards. The algae beds receded farther and yet farther apart, finally terminating altogether, while we noted, gradually opening up in front of us, the coast-lines of a noble and spacious bay, semicircular in shape, around which, and extending up the slopes of the hills behind, gleamed the lights of a large and widely-scattered town—populous, too, if the hum and bustle of busy life reaching us even at this distance were any criterion. Here, too, we left the current that had so long borne us on our way. After a few minutes' steady strain on the tow-line, during which we distinctly heard the voices of what Professor Barlow informed us were the hortatores or overseers (also called by Plautus, pausarii), encouraging the remiges or rowers in their task by a sort of rhythmic refrain or chant, the schooner was slowly but surely drawn from the current of the ocean stream, and was presently gliding through smooth water towards the entrance to the bay.

Passing a projecting headland of rocky precipitous cliffs, whereon stood a pharos or lighthouse, differing materially in design, however, from Smeaton's great structure on the Eddystone Rock—the model of all future erections of the kind—we swept into the bay, and in the clear moonlight beheld the harbour and town unfolded like a panorama before us.

IN the fair moonlight this mysterious town of Nova Messana—whereon the eye of no European had rested that returned to tell the tale—stood out in strong relief. The houses, being built of a white stone or marble, were thrown into prominence against the dark background of the mountains. The city was evidently of great size, for around the entire sweep of the coast-line, and over the shoulders of the two spurs of hill that jutted far out to sea and formed the bay, serried lines of streets and houses were to be detected. Besides, the hoarse muffled hum that reached us, of vehicles rolling along roads, dogs barking, children shouting, music playing, and all the hundred-and-one sounds one overhears when approaching a busy hive of population, betokened the presence of a mighty multitude, be its nationality what it might. But who were they? How came they to these latitudes? Such questions were still wrapped in mystery.

At last we glided slowly into the magnificent harbour round which the town clustered in serried lines of masonry. Yonder were substantial stone wharves lined with stately warehouses. Close in, by the side of the wharves, lay innumerable craft of much the same type as that now towing us, though lacking the rostra or high convoluted beaks. On the wharves we also noted cranes and slings for loading and unloading cargo of much the same type as those among us.

About a hundred and fifty yards from the shore, Lepidus informed us we could anchor without any danger. Then the trireme, having cast off the tow-line, returned towards us, and Lepidus intimated that the consuls would like to see the leaders of the party as soon as was convenient.

"Look here, Professor, you go, and take our friend Bill with you," said Captain Anstey, pointing to me. "I cannot leave my ship. It wouldn't be right."

"Why not come up with me and see what the people are like?" replied the Professor.

"No, Professor; again I say, let Bill and you go. I will stay here, and if any mischief is intended, I'll fire on the town with our carronade. It's not worth much against cannon, but it's unlikely, if they work with the tin armour that worthy gentleman Mr. Leppydoes wears, that they ever heard the sound of artillery before."

"Well, as you think best, skipper. Bill, do you mind going with me?" he asked of me.

"Not a bit. There's nothing I should like better; but I would advise we go heavily armed."

"Of course. We'll each take a couple of revolvers and some spare cartridges. We don't know anything about the people yet."

"I say, Professor, it might not be amiss if, under cover of saluting the flag of the country, we fire one or two blank charges. Explain to your friend Leppydoes that we mean it as an honour."

The Professor did as desired, and Lepidus appeared highly gratified. He thought they were to be treated to some entertainment. But when the thunder of the first discharge awoke all the echoes around the bay, and reverberated among the mountain defiles for miles back—when, too, it was followed by a second and a third, an awful stillness fell upon the city.

Then rose the terrible cry: "It is the voice of the gods, it is the voice of Jove!" and when we looked once more at the galley, we saw that Lepidus and his companions were kneeling on the deck. Their palms were turned outwards, and their heads bent in the attitude of worship.

The worthy centurion, though startled by the sound, was sufficiently master of himself not to show fright after the appalling sound ceased, but his respect for us had been deepened. Therefore, when we stepped aboard the trireme by a gangway thrown from its deck to our bulwarks, we were received with every demonstration of honour. We were conducted to the high raised poop, where seats were provided for us, and where Lepidus endeavoured to do the honours of his vessel. On inquiring whence we came, and on learning from the Professor that we hailed from the west, he inquired how things went on at Rome, who were the consuls, how far the "Mistress of the World" had now pushed her conquests, and the like, until he succeeded in so bamboozling the poor Professor that he had to beg for time to answer the questions in detail.

But before this could be done, we reached the wharf, and there, packed closely together, and evidently watching our approach with the intensest interest, were thousands of human beings, all attired in strict accordance with the costume of ancient Rome, the toga virilis We noticed that very few females were present. Males predominated. Yet the utmost decorum and order prevailed. Attended by Lepidus, we disembarked and passed up the narrow lane left for us between the crowds of eager citizens. A party of soldiers, attired like our guide, and armed with the spear, circular shield, and sword, preceded us, and we were followed by the entire mass of the population.

We passed along streets of noble buildings gleaming white in the clear moonlight, each edifice being an exact facsimile of those that used to figure in the engravings in our books of Roman history and antiquities. They were in general two or three stories high, the façades being richly adorned, while the porches and doorways were ornamented with fine carvings, and were also furnished with rows of Ionic and Corinthian pilasters. The paucity of windows facing towards the street gave the frontages of the houses rather a blank, heavy appearance. As was the custom in Rome, nearly all the windows of the rooms on the first or ground floor faced inwards upon the spacious inner court, opening from the atrium, or general sitting-room. From lattices over our heads faces peered through, and soft dark eyes looked curiously on the mysterious strangers that seemed to have dropped from the clouds. From the roadway litters, chariots, and waggons, heavy and clumsy, were drawn up that their occupants might have a glimpse of the strangers.

During our walk Lepidus kept up a lively conversation with Professor Barlow. I had been a fairly good Latin scholar when I graduated in Edinburgh University. Though the rust of time had blunted the edge of my proficiency in the language, still I was able to follow with comparative ease the course of the conversation.

Lepidus, as we advanced, pointed out the theatre where the plays of Fundanius and Puppius, dramatists of the Augustan age in Rome, were still performed, as he stated, with those of native colonial playwrights. He also showed us in the distance the Coliseum, the Museum, and other places of note. Finally, we reached the Forum or market-place, a broad open space, laid out in the form of a square,—as far as we could detect in the darkness,—and adorned with numberless statues. In the Forum were located the consular and senatorial halls and offices.

At last we stopped in front of a splendid pile of buildings with a handsome pillared propylaeum, to which a flight of steps led up. We ascended the stairs with our guide amidst a crowd of eager spectators.

"The Senate is in session, and would like to see the strangers," said another individual, approaching Lepidus.

"That is well," replied Lepidus, and, motioning us to follow, he entered the Senate House of the Republic of Nova Sicilia.

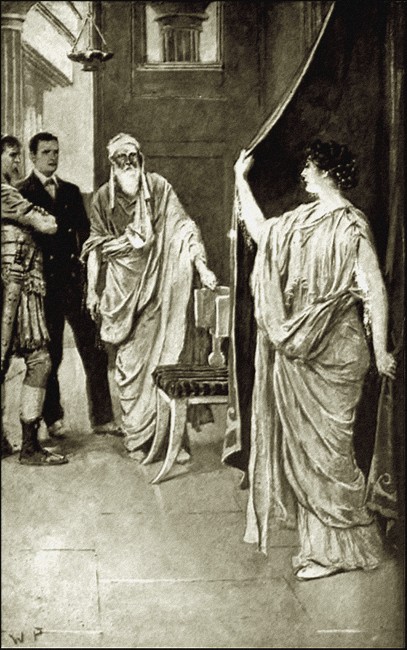

A vast hall with sloping benches like a semi-amphitheatre! At one end was a raised platform or tribune, in front of which were tables for scribes. Here met the assembly of the old men of the state—the Patres Conscripti—in whose hands lay the destinies of the country.

One of the two consuls for the year always presided over the deliberations of the Senate, taking the duty for six months each. The aged councillors of the republic, whose long white beards evinced the age and venerable character of the owners, received us standing. The consul, Caius Flaminius Piso, in his own name, conjointly with that of his colleague, and in the name of the Senate, welcomed us to the country. It was evident that Skipper Bob's salute had produced a very extraordinary effect on the minds of the people and of the Senate. They regarded us as descended from the gods, or, at least, in some subtle way connected with them, if we were not gods ourselves, and it seemed to them perfectly in keeping with the eternal fitness of things that these strange personages should be received with all honour.

Piso, a fine-looking old man with a silvery beard rippling down to his waist in hoary masses, having duly welcomed us, motioned the senators to be seated, then led us to some ivory chairs placed on a slightly lower level than his own, and reserved for those whom the Republic delighted to honour. He then indicated to us that we should sit down.

After seating himself, a slight pause ensued, intended as a gentle hint that the Senate would like to hear our story. The Professor was not long in responding to the hint. Bracing himself for the effort, he commenced to speak, and, after the first few sentences, got on wondrously well, and produced a very favourable impression on the Senate. In a few simple words, as far as I could follow him, he recorded the reasons for our voyage, then the circumstances of the suppressed mutiny, and, finally, the discovery of the paper in the bottle written by the Professor's brother-in-law.

With breathless silence the whole story was listened to by the members of the Senate. At last, when on concluding the recital he inquired, "Tell me, I entreat you, has my kinsman reached your hospitable shores? and if so, is he still here amongst you?" The answer pealed out from many responsive throats, "Certe—Yes"—than which no word could have been more delightful to Barlow.

"Pray inform me how he arrived here," said the Professor, addressing the consul. "When can I see him?"

But a strange diffidence was now visible in Piso's manner.

"I—I—am sorry—he has gone—"

"What has he done? Where has he gone? Has he committed any crime against your laws?"

The Consul shook his head, and a strange buzz of whispered comment on the question ran through the assembly.

"Then if he be not a criminal, if he be not an offender against your laws, if he has done nothing to merit punishment, why may not I see him?"

There was a sternness and a decision about Professor Barlow's manner that were not without their effect on the Consul and the senators.

Piso shifted uneasily, conferred with one of the old members who sat near him, and then replied:

"O strangers, think not our unwillingness to speak was due to any hostility to your kinsman. I was anxious to save your feelings as much as I could." Here again Piso paused and eyed the Professor sympathetically.

The features of the latter paled visibly as the words fell on his ear. He started, glanced quickly at me, then said impulsively: "I would know the worst, tell me all."

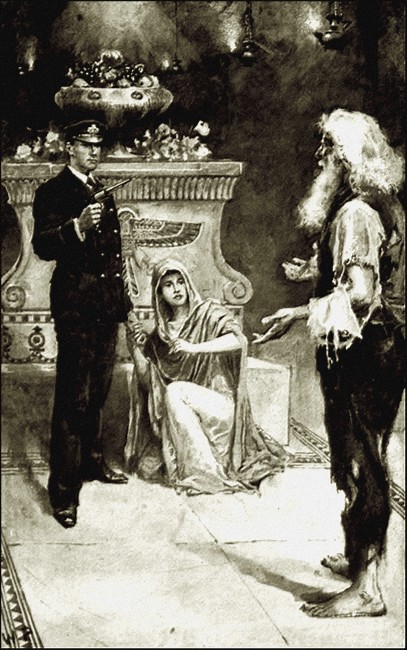

"You have made your choice. Joannes Websterius, about six months ago, mysteriously disappeared. We know not where he is, save that he was seen to enter the 'Cave of Gems'."

The Consul thereupon began to explain the nature of the "Cave of Gems," which, it turned out, was only the entrance to a perfect network of caverns which ran throughout the entire length of the mighty range of mountains behind the town.

The Professor listened in silence. Then he said in a low tone: "Do you think he has starved to death there? Is there no chance of escape?"

The Consul shook his head. "Even if he escaped and discovered the exit on the other side of the mountains, that would lead him into the country of the Ariutas, our enemies, and he would be remorselessly killed."

"My poor Mary!" exclaimed Barlow sadly. Then turning to the Consul he said, "Will you inform me of all you know of Webster, so that I may convey the news to his wife?"

"He had become very morose and unsociable in his habits just before his disappearance. He would not converse with anyone, nor would he have any intercourse with us. He wandered about the country aimlessly, neglecting his work and his duties. He would neither eat nor drink. As for sleep, it never seemed to visit him."

"The poor fellow had become desperate through his lonely situation," said the Professor to me in a low tone; then turning to Piso he continued: "Ah! he had been so long separated from his wife and family, from all who are dear to him, that despair had seized on him."

Piso nodded his head and added: "You desired to know something about the manner of his arriving here!"

"I should be very grateful."

"About five years ago he came to us in a small boat with two or three other companions, all of whom have since died. He informed us, through signs, that he had suffered shipwreck in the Mare Occidentale, and had endured terrible hardships before reaching Nova Messana. After being entertained by us for some time, as he was a man of great ability, we had him instructed in our language, which we deemed it strange he did not know, and at the end he was in charge of our naval construction yard. He would fain have made radical changes, and banish the remiges, or banks of rowers, as being useless; but that we could not recommend on his bare word alone; now, however, that we have seen your vessel moving without oars, the Senate will again consider the scheme."

"May I see the Cave of Gems?"

The Consul looked surprised, but recovering himself in a moment he replied:

"Most certainly, we will assist you in every way we can. You will be remaining here for a few days. The Government of the Republic will lend you all the help in its power."

The Professor gratefully acknowledged the promise. Immediately after this matter was settled, a knot of senators gathered round us both, and endeavoured to elicit information concerning the changes that had taken place in Rome and in Europe generally. They seemed to date everything to the beginning of the "Perpetual Consulship," as they termed it, of Octavius, shortly after the death of the great Julius. Not a member of the Senate but had some question to ask. It was as much as the Professor could do to answer the queries as briefly as possible, so rapidly did they follow each other.

The Professor's replies evidently excited profound astonishment, though few of the "Fathers" appeared to realize what was said. An example of this occurred when Barlow, in a voice choking with emotion, thanked the Republic through Piso for the humanity and kindness it had shown to his brother-in-law, adding that he would represent the matter to the British Government, so that some formal recognition might be made.

"The British Government—where is that?—Britannia we know as a dependency of Rome—is it not still so?"

The Professor was only able to indicate a few of the steps whereby the British Empire had advanced to its present pitch of greatness when he was interrupted by many of the senators crying, "But where was Rome all that time? Why did she allow you to attain such greatness?"

"Because Rome was crushed and overwhelmed, and no longer exists as the Rome you knew." But the fact at this time did not seem to be realized by the senators. They only smiled incredulously at what they considered the Professor's romancing.

Barlow at this stage expressed his desire to obtain some information regarding the migration of the Roman colony to the South Seas, adding, "We, in Europe, know nothing of your existence here."

"Nay, we do not wish you to know anything of us," retorted one of the senators hastily.

"Why so? Why do you not wish to be known?"

"Because Rome would crush us. She would not tolerate our independent existence. Our fathers have informed us of the policy she pursued towards her colonies, and time will not have modified her ideas."

"But I tell you Rome does not exist to-day."

Only a shrug of the shoulders followed this remark of the Professor's. The Senators evidently considered he had some sinister motive in asserting the fact, which to them was incredible, and one of them voiced the suspicions of the others when he muttered, "How do you come to know our language if Rome no longer exists?"

Observing this, Barlow varied his question by requesting Piso to inform him how their fathers had reached the quarter of the globe in which they now lived? The business of the Senate had been over before we arrived, so that we were not interfering with its transactions by remaining in the Chamber. Piso pondered over the request for a moment, then said:

"Tis only just you should know. After Caius Julius Caesar had grasped at supreme power, and overturned the ancient form of government—after the triumvirate of Antony, Octavius, and Lepidus in its turn had been superseded by the imperial authority of Augustus—after our great hero, Brutus, ultimus Romanorum had died, a number of the older Republicans in the state, despairing of the salvation of the country, determined, after the manner of the old Grecian colonies, to found a new state which would represent all the nobler features of ancient Roman virtue, valour, and fortitude. Our forefathers spent a year in quietly making preparations. They arranged to meet, as the narrative preserved in our archives records, at the head of the Red Sea, with 20 triremes, and a company of 400 men, 150 women, and many children. The vessels were well provisioned, and appointed with everything necessary for the foundation of a new colony. They knew they must push out into the vast unknown, beyond the confines of the known world, otherwise the greed of conquest, united to his rage at their escape, would cause Augustus to send his legions to wipe them out of existence. Therefore they resolved to go as far as possible beyond India Extra Gangem, from which ambassadors had been sent to Augustus, so much dreaded was the Roman name even there.

"The last point known to our Roman geographers, at which our fathers touched, was the Sindae Isles in the Indian Ocean. Here they heard that two ships from Brundusium had been there a few months before, and had sailed farther east. This determined them, and after laying in a great quantity of provisions, they also sailed east. After proceeding twenty days in this manner they reached the shores of a very large continent, where the inhabitants were exceedingly savage."

"Australia or New Guinea," said the Professor to me.

"Here they were about to land, but on consulting the augurs they said the gods had brought them only half-way on their journey, and that they must proceed onward for at least forty days more, when they would see their appointed home. Our fathers never doubted that the gods were guiding them, and this was proved by the fact that they were seldom out of sight of land more than a day at a time, and were enabled to take in water and fruits. On the morning of the fortieth day they came to the algae beds, which doubtless you saw, and which had well-nigh proved an insurmountable obstacle. But a flight of birds miraculously showed them the passage, down which they went fearlessly, the great Neptune himself leading the way in the shape of a large porpoise. That night our fathers reached this land. Here we have abode ever since. That is the history of the foundation of Nova Sicilia."

"What a wonderful history! And from that day to this you have quietly progressed, until you have reached the stage where we find you to-day?"

"Even so. The gods have been good. Our constitution is based on that of ancient Rome, our laws, our municipal regulations, are all based on those of Rome. We would have called our city Nova Roma, but it would have been unlucky. You will, I trust, remain with us for some time, and study our polity. We in our turn will study yours, and thus we may mutually benefit. But I beg of you when you return home not to inform the Romans of our existence."

Professor Barlow no longer attempted to remove their deeply-rooted belief in the "eternity" of the Roman power. He accepted Piso's invitation to make a stay in the city, but insisted upon returning to the vessel that night to inform Captain Anstey of what had taken place. He promised, on the following day, to call upon Piso, who offered to conduct him throughout Nova Messana.

WHEN the Professor and I reached the street, we were at once made the centre of an eager group of spectators, who walked with us as we returned to the vessel. Yet one could not help observing the innate courtesy of the people. Though their curiosity must have been intense, they did not cause us to feel its effects in any unpleasant manner, by mobbing us, or handling our clothes, as savages are apt to do.

Their attitude was most respectful. But it was easy to see they were in doubt whether to rank us as men like themselves or as sons of the gods.

We passed once more along the stately streets, Lepidus acting as our guide, and we found something to admire at almost every step. The massive architecture gleamed dazzlingly white in the glorious moonlight, while from well-nigh every house resounded the notes of music or the ripple of soft laughter.

At the top of the long tree-lined avenue leading down to the wharves Lepidus took leave of us, with stately Roman courtesy, and we pursued the remainder of our journey alone, save for the posse of the curious, who still followed us.

"My poor brother-in-law!" murmured Barlow, as we walked down the approach; "what a lonely existence he must have had amongst them. I fear he must be dead, or he would have been heard of."

"Well, Professor Barlow, I'll make one to go with you and search until we find some traces of him. I don't think he can be dead. Surely his body would have been found."

"Right, lad; you are a good fellow; you have raised my hopes again. We'll make a big effort to find some intelligence of him. These antipodean Romans seem a grand race."

"That they are, if all be true that we hear about them."

"Lepidus has given me a great deal of information regarding his nation. It appears they look upon a liar as having committed moral suicide, and no one will have anything further to do with him."

"That is a good trait. They do credit to their ancestors."

"But that little old man, with whom I was speaking, gave me the most information of all. He is a half-caste, and belongs to the native Ariutas. He is a doorkeeper in the hall."

"Dear me, what did he say?"

"He says that the New Sicilians are cold, critical, and unimpassioned. In some respects they are cruel, in others callous; but I think it is because they do not know what pity is. Yet they are just, virtuous, and noble in their lives, with all their severity. 'Crime is rare,' he said, 'and poverty is almost unknown.' They are simple in their habits, and exceedingly hospitable up to a certain limit, save to those strangers that come to spy. Several natives from Easter Island came here some weeks ago. They were kindly treated and sent home again, with a warning, however, not to return. With the aborigines of this island they are constantly at war, but as to intercourse with the outside world they have absolutely none."

"Is the island of Nova Sicilia large, did the old man inform you?" I inquired.

"Yes, larger than the original Sicily. It is wonderfully fertile, and such minerals as gold, silver, copper, lead, etc.—are to be found almost everywhere, with diamonds, rubies, sapphires, and opals in extraordinary abundance."

"It is a wonder it was never discovered before now."

The Professor shook his head, and then said in a lower tone, "There is more under that than appears. I believe the island has been discovered again and again, but that no one has returned to tell the tale."

"What do you mean?"

"Though not naturally cruel, the people here will do anything to preserve their liberty. They dread the very name of Europe. They cannot believe that the Rome of to-day is totally different from the Rome of 1800 years ago."

"Do you think they killed those who came here before from Europe?"

"Well, you saw me go over to a cabinet in the Senate Chamber and look into it. It contained curiosities. Among them, to my intense surprise, I found three suits of antique European clothes, an ancient flint-lock musket, a volume of Shakespeare dated 1736, and an old clay pipe. On asking where these came from, the Senators said, 'From the waves'. But there was a strange smile on their lips that I didn't like. My idea is, they belonged to some Englishmen who were fortunate enough, as they thought, to discover a new country, but were never allowed to leave it alive."

"But that is not like the nature of the New Sicilians."

"Far from it. Hospitality is to them an article of religious faith, but then security is the first consideration."

"Might these articles not have been found in some sailor's chest that was washed ashore?" I asked.

"It is possible, but I hardly think it probable, because they would have kept the chest also."

The Professor remained for a long time plunged in thought. In fact we were near the pier before he said:

"I don't like the look of it. We must watch, and be on our guard."

At last we reached the wharf, and on a whistle from me, Bob sent the boat across for us, and took us on board. We had so many things to relate to him that the new day was near its dawning before we separated.

When we awoke next morning and went on deck, a glorious prospect awaited us. There was the lovely city of Nova Messana basking in the sunshine, and glistening white as a pearl against the deep emerald background of the majestic range of mountains. The hills were densely wooded, all except the towering peak of the volcano; and a more charming picture than that presented by the bright blue of the bay studded with shipping, and the town stretching on all sides as far as the eye could reach, with its vineyards and olive groves, its orchards and pleasure gardens, could scarcely be conceived.

"It beats the Bay of Naples, I verily believe," cried the Professor enthusiastically. "Surely men living amid such beauties cannot be otherwise than noble."

"Are there any other towns in the island, Emilius?"

Lepidus had sent over one of his officers to know if he could be of any service to us. He was standing near, and heard the Professor's remark, at which he smiled gravely.

"O yes," answered the young officer. "There are four other seaports—Brundusium, about twenty miles along the coast; Syracusa, on the other side of the island, about sixty miles distant; and Drepanum and Bruttium, about eighty and a hundred miles respectively. We estimate the island to be about two hundred miles in circumference, and about a hundred and twenty or a hundred and thirty miles across. But the interior, though in parts thinly settled by the colonists, is in large measure held by the natives, who, by the way, are very far from being savages. In fact, there are over fifty miles of the coast-line still in their hands."

"And what is the population of the island?" I asked.

"That would be hard to answer. Messana has over 70,000 inhabitants, and the other towns less in proportion; but I should estimate the total population at not less than 400,000, exclusive of natives."

"And these absolutely unknown to the people of Europe," said the Professor. "What a treat it will be to study their customs, and note what direction their own natural development has taken!"

Emilius soon after went ashore to meet the Consul, who was to pay us a state visit that day.

The morning was but young when the shrill sound of a trumpet from the shore, where crowds had been gazing at us from the earliest hours, betokened the advance of the consul. Presently we saw Piso come down to the wharf, preceded by lictors, with their bundles of fasces, from which peeped out the heads of the axes. The party embarked on board the galley that had been our convoy on the previous evening. Evidently the consul meant that his state visit should impress us.

Captain Bob was determined that "these old-fashioned beggars should see that the world had not stood still, if they had." He therefore ordered the mate to salute the New Sicilian flag with three more discharges of cannon, and the ensign to be dipped as the galley approached.

The effect of the artillery was even more pronounced than on the previous evening. The thunder of the discharge reverberated again amongst the hills with startling echoes and re-echoes. The rowers were evidently awe-stricken, and stopped pulling, and it needed all the persuasions of the hortatores to induce them to proceed.

But Roman pride was flattered all the same. The Consul, as he stepped from the galley on board the Fitzroy, was graciously pleased to observe to the Professor that the Republic would be pleased to enter into an alliance with a state whose representatives were ready to show the flag of Nova Sicilia so much honour.

The Professor bowed low to hide his smile of amusement. Piso was evidently much impressed with what he saw on board the Fitzroy, but when he heard that it was but a cockle-boat compared with some of the warships in the British navy, he appeared to think the travellers were, vulgarly speaking, "talking tall." He replied with haughty assurance, that even the Roman Republic in the Second Punic War accounted a quinquereme a very large vessel.