RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

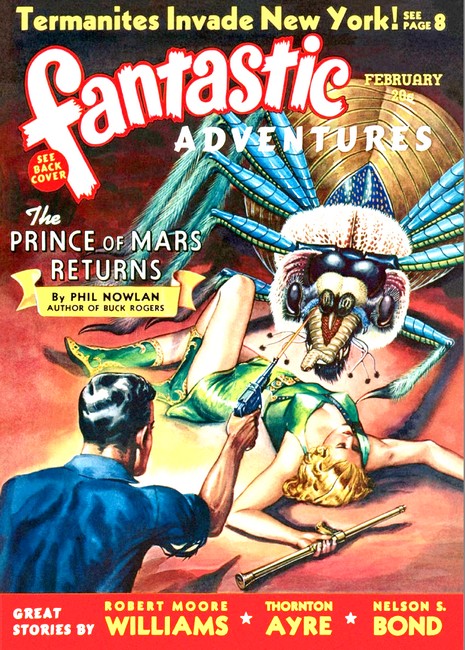

Fantastic Adventures, Feb 1940, with

first part of "The Prince of Mars Returns"

Hanley's gun roared as his leap carried

him high over the heads of his opponents.

I, CAPTAIN DANIEL J. HANLEY, chief meteorologist of the General Rocket Corporation, had no intention of going to Mars when I stepped into the new space car and pressed gently but with finality on the gravity-screen lever.

I was conscious only of a great urge to get as far away as possible from a certain young woman who had—but why go into details about that? It is enough that I didn't fully realize what I was doing.

And as a result, here I was, the first man ever to pass beyond the stratosphere of Earth, actually hovering a scant mile above a Martian landscape, trembling with suppressed excitement and giving not a thought to the girl who had driven me to my mad, premature plunge into space.

I faced infinity with reckless abandon, and found that I liked it. What did it matter if the end came in a day, week, or month? Why, there were no days, weeks, or months in interplanetary space! Only eternal, blazing noon on one side of my tiny craft and everlasting midnight on the other, while countless galaxies gleamed upon me in new glory from all sides.

That I landed on Mars, instead of some other planet, was due solely to chance. In hurling my tiny craft madly, blindly away from Earth I happened to set it on an orbit that brought it closer to Mars than to any other heavenly body. As I drew nearer, the planet grew in size and in interest, until it entirely filled the great lens of my wide-angle scope. Its mountain ranges and peculiar canals became plainly visible.

I manipulated my rocket blasts a bit and swung closer. There was no indication that the canals were man-made. Rather they seemed furrows caused by glancing blows of meteors. And there were many craters which, though small like those of the moon, appeared to be the result of head-on meteoric impact.

As the planet grew still larger, I could see that there were no oceans and continents in the sense that we know them on Earth. Nevertheless, the divisions between the ice caps, polar seas, solid vegetation belts, canal-irrigated sections, and finally the vast and eternally dry, red equatorial belt, were clear and sharp. The northern and southern hemispheres, widely divided by this belt, seemed duplicates.

"Why not inspect the planet at close range?" I asked myself.

So here I was, easing down over a countryside such as no man of Earth had ever seen.

Through the forward port I gazed upon a country of scrubby, dwarfed, cactus-like trees and shrubs, stretching away drably to where a ribbon of water—one of these much discussed "canals" sparkled. To my left, toward the equatorial belt, the vegetation became more dwarfed and sparse, until its pale, yellow-green blended into the deeper, reddish tint of the arid desert.

To my right, a rolling plain swelled into distant hills heavily covered with the yellow-green foliage. On the horizon, a range of gaunt, jagged mountains flashed and shimmered like crystal in the pale, cool sunlight.

"Quartz!" I muttered. "They must be pure quartz!"

I brought my craft gently down on the bank of the little river that meandered along the "canal" or valley. With trembling fingers I opened the valve of one of the test chambers and watched the pressure gauge.

I had feared an uncomfortably rare air, but the gauge registered a pressure no less than that of mountainous regions at home. There was more carbon dioxide and more hydrogen, but the oxygen content was about the same as on Earth! I could leave my little metal shell and walk around on a new planet!

Excited, I threw back the hatch at the top of my little hemispherical craft and leaped out joyously. I landed, not where I expected-but fifteen or twenty feet beyond. I had forgotten that I would weigh only about a third as much as on Earth.

But with a little practice, I found I could gauge my muscular effort instinctively to the desired distance. It was a delightful amusement, leaping twenty-five or thirty feet with the effort of an eight or ten foot jump. But finally I gave some consideration to my position.

"And now," I told myself, "here I am on an utterly strange planet. I have no idea what dangers I may have to face. I don't know whether intelligent beings live here or, if they do, what their attitude toward me might be. It might be just as well to have an ace in the hole. I'll hide my ship, mark the spot well, and then if by any chance things should get too hot for me, I'll have the means in reserve to do a fade-out."

I studied the banks of the stream. Obviously the little river was at high-water mark. That was good. There would be no more powerful current than this to wash my ship away then, for it was my intention to sink her in the middle of the stream.

Again I climbed aboard, closed the hatch. Letting my space car drift a few feet above the water, I maneuvered over the center of the stream and then submerged. The ship went about ten feet below the surface. I had previously unloaded the equipment I meant to use, so nothing remained but to put everything in order, enter the airlock, adjust the pressure, and dive down and out through the port.

I realized, as I donned my woolen shirt, leather breeches and puttees, that the sun did not shed as much warmth on Mars as on Earth. It seemed scarcely more than half the size to which I was accustomed. As I rolled up my blankets, I had little doubt I would need them after nightfall.

As yet I had seen no sign of animal life. But there were many spots on Earth where a visitor would find none for miles. So that proved nothing. I strapped a heavy automatic to my thigh, clasped on a cartridge belt. As an extra precaution, I slipped a smaller automatic in a shoulder holster which I put on under my shirt. For the rest, I thought, my hunting knife and short-handled axe might prove serviceable.

Marking the position of my submerged spacecraft by carefully sighting the distant mountain peaks on crossed lines, I shouldered my light pack and hiked toward the gleaming, flashing mountain range.

It was glorious to weigh no more than about sixty pounds, and yet have muscles that had been accustomed to carrying one hundred seventy. Walking did not give them the exercise they demanded after the long period cooped up in the little space ship, so I ran with exhilarating lightness, practicing long and high leaps as I went and shouting, at times, from sheer, unrestrained joy.

I had gone about five miles when I first saw her.

The scrubby undergrowth had given way to another cactus-like type of vegetation, the trees of Mars, slim and tall with stubby, blunt branches. They bore no leaves. Rather, both trunks and branches seemed to be leaves in themselves, pale yellow-green and semi-transparent. A thin syrupy sap ran freely from one, which I scored with my axe.

The sudden flash of a movement somewhere ahead of me arrested my eye. Abruptly I halted, standing motionless, alert. I saw nothing but the yellow-green trees. I shifted my axe to my left hand. Quietly my right fist rested on the butt of my automatic. I advanced, poised for instant action.

From somewhere ahead came a metallic twang. I ducked. A heavy missile thudded into the trunk of a tree directly behind me. Then a girl stepped confidently forth, about twenty feet away.

Evidently she thought she had hit me, for her first reaction was to start back at the sight of me standing there. Hastily she dropped the four-foot tube she held in her hand, and in something like a panic, tugged at a kind of quiver or a sheath slung across her shoulder until she held another tube pointed straight at me. For some moments we stood motionless, gazing at each other in amazement.

I had rather expected to find life of some sort on Mars, and was even hoping to find intelligent creatures of some sort. But to find a pretty, golden-haired Amazon, in green kilts, soft leather leggings and loose, sleeveless blouse that did not by any means conceal her slender form—well, that took my breath away!

AT last the significance of that tube, pointed at my chest unhesitatingly, broke through my stunned thoughts. I dropped my axe, held out my empty hands in a gesture of friendliness.

"Can't we be friends?" I smiled, knowing full well my language would not be understood, but hoping that my tone might.

Her reply, uttered in a soft, euphonious tongue, was obviously a question. And feeling a bit foolish, I tried to indicate by gestures that I could not understand her.

For a moment she watched me. A quizzical look crept into her green-blue eyes. Then she laughed and lowered the tube a bit, but quickly covered me again as I stepped forward. She was taking no chances, it seemed, for again her eyes flashed a warning as I sought to recover my axe.

She motioned me back. As I complied, she walked over and picked up the axe herself, never taking her eyes off me. Next she motioned toward my knife. I tossed it at her feet, and she picked this up also. The automatic strapped to my leg meant nothing to her, seemingly. She did not demand it.

Feeling safer now, she stood back and surveyed me speculatively. At length she motioned me to precede her in the direction of the distant mountains. This I did willingly enough, for I felt that with my two guns I could always command the situation, even if her people did not prove as friendly in their attitude as I hoped.

I had been eyeing those tubes she carried in the quiver, and had come to the conclusion, both from their appearance and their peculiar, twanging, metallic quality, that they hurled their bullets by the force of a coiled spring.

As I marched on, occasionally turning to look at my fair captor, the vegetation became thicker, and the hills and ravines more pronounced. Coming to the top of one of these ridges she called out, and by gestures commanded me to turn sharply to the right. A bit later she paused and gave a peculiar whistling signal. This was replied to from some point ahead, and we went on.

I hardly know what I expected to see. It certainly was not the type of structure we finally came upon.

Sheer walls of a glassy, translucent, solid material rose to a height of fifty feet or more. At least I judged them to be solid. I could see no joints or crevices.

There was a triangular opening. Through this peculiarly shaped gateway I strode on a pavement of material similar to the wall, which was worn smoothly and deeply as though by centuries of countless feet.

The space inside the wall was diamond-shaped, about a thousand feet long and probably three-quarters that distance at its greatest width. The entire space was paved with a solid sheet of the glassy material, in which smooth troughs or channels had been worn.

In contrast with the solid and permanent nature of the walled space, which gave evidence of high engineering skill, there was no shelter inside except some two or three dozen tents, not unlike Indian tepees, of pale green leather over metal framework.

There were a score of men and women about, all garbed exactly like my captor: golden-haired, blue-eyed people of somewhat slighter build than the average on Earth, but otherwise remarkable only for the uniform perfection of their physique.

Men and women were of about the same height, none of them coming within several inches of my six feet. The men were only slightly sturdier than the women, and all seemed in perfect physical condition, like trained athletes. I did not see a fat nor a flabby individual among them.

Our appearance caused no great excitement, though a number gathered around us and my captor was questioned with mild curiosity. But they made way for us readily enough at her explanation.

Quite at ease now, she walked beside me, having sheathed her "gun," touching my arm occasionally to direct me toward a tent in the center, somewhat larger than the others. It was about thirty feet across, of a high, conical shape. A large translucent disc, set in the top of the metal framework, let in a soft light.

I don't know what she said to the blond-bearded man who sat at the carved, light metal table, but from her tone and the little gesture with which she called his attention to me, it must have been something like:

"Look what I found in the forest, Father!"

There ensued some rapid conversation in that peculiarly mellow tongue. Then, to my considerable embarrassment, they began to examine my apparel and myself with a critical scrutiny, finally motioning me outside where there was more light.

That they were both of them greatly puzzled was quite clear. At length, the man who seemed to be the head of the little community, endeavored to talk with me by signs. He placed a finger on my chest and looked questioningly at me. I guess I looked foolish, for I did not get him at first. So he pointed to himself.

"Ur Mornya," he said. Then he pointed at the girl and said, "Ur Lil-rin."

"Oh!" I nodded. "You mean those are your names." Then I pointed to myself and bowed.

"Dan, Dan Hanley, Captain Daniel J. Hanley, U.S. Army Reserve Corps, at your service."

"Danan-lih" said the girl softly, as though the name was somehow both familiar and amazing.

Then Ur Mornya waved his hand, generally, toward the people scattered about the enclosure.

"Ta n'Ur," he said. From which I surmised that the "Ur" part of their name was a clan or community designation. I smiled and put my finger on his chest. "Mornya," I said. "Ur Mornya."

He seemed a bit taken aback at the freedom of my gesture, but smiled his assent, if a bit wryly.

Then, I turned to the girl, and suddenly curious to see what would happen, placed my hand boldly on her shoulder as I spoke her name.

For an instant Mornya was about to lash out at me in fury. Lil-rin's eyes blazed in indignant resentment. Then suddenly she blushed and tried to act as though I had done nothing she thought unusual, while with a struggle her father strove to assume the same air.

Here was no race of barbarians, nor of slaves; but people of high spirit, independence, culture, and quick intelligence. I sensed that I had committed a grievous offense, which was forgiven me instantly in view of my "ignorance." I sensed, too, that they must regard me somewhat in the light of a guest. Some imp of perversity led me to puzzle them still further when, after a bit, they motioned me within the tent again, where a meal was laid out on the table.

I looked curiously at the unfamiliar viands of fruits and vegetables, most of which I had never seen. There was meat, and a fowl of peculiar shape. All of the tableware was of metal, a pale alloy that looked like gold, but was not. The platters were inlaid with iridescent stones, and there were spoons, but no knives. My hosts used the blades which they took from the sheaths at their belts.

I made an apologetic gesture and went to my little pack, which had been laid in a corner. From it I took my silver knife and fork, and returned to the table.

They strove to conceal their curiosity, but stared frankly. It was on the fork that their interest centered. Not only its shape seemed unfamiliar to them, but the sterling silver itself. The girl watched my use of it with a kind of fascination, then actually blushed and giggled when I handed it to her.

Her father frowned and made another serious effort to question me by gestures. At last I gathered his meaning. He wanted to know whence I had come.

I pointed upward, toward the sky. His frown increased, and he shook his head. My explanation wasn't at all satisfactory, it seemed. Nor did I wonder at this. And the thought came to me then that it would be just as well not to try to explain. I wouldn't be believed. Who on Earth, say, would be believed if he claimed to be a Martian? True, I might exhibit my little spacecraft in substantiation of my story. But, I did not know that sooner or later my life might depend on keeping its existence and its hiding place a secret. So I shrugged and let it go at that.

NIGHT came. A new tent was erected for my use. And when at last I tired of the glory of the two Martian moons which swung low and swiftly across the scintillating heavens, and Lil-rin had given me a curiously, speculative smile of adieu. I went inside and threw myself on the pile of soft skins and silks that evidently was intended as my couch. Almost at once, I slept.

The days passed swiftly. Little by little I learned their language. It was hard pulling it off at first, but I had always had a certain facility with strange tongues—I learned something, too, of Martian life and history.

Mornya, Lil-rin's father, was Myar-Lur, supreme chief of the Ur, a clan of a race which, like the Cossacks on Earth, was somewhat nomadic in its inclinations, and jealously guarded its tribal traditions. Mornya with his seven Myars, or sub-chiefs, was at present in the service of the Northern Cities.

For five successive years the clan had contracted with the Northern Cities to guard the Desert Gap in the Quartz Mountains and the approaches to it.

The work of the clan had consisted chiefly in keeping the territory south of the Gap clear of the "dulyals," or yellow apes, beasts of almost human intelligence. These dulyals, I gathered, possessed a higher order of mentality than any of their counterparts on Earth.

They were tailless, walked erect, but had prehensile feet. They were covered with a golden brown fur, and though larger and more muscular than Martian men, were more human than apelike in build. They were omnivorous, hunted in packs, had a rudimentary language, and fashioned crude clubs and spears.

Yet, they were distinctly not human, Lil-rin informed me.

"After two or three generations of captivity," she said, "they make excellent slaves. Unless they taste blood, they can be trusted invariably to be loyal to their masters. They bring higher prices in the slave markets because they are stronger and more docile, than men that is, the domesticated ones are more docile. About two-thirds of the city populations are dulyal slaves.

"You know," Lil-rin looked up at me slyly, "the reason I tried to shoot you that day in the forest was because I thought you were a dulyal!"

We were sitting on an outcropping of rock, a great scintillating quartz boulder, gazing down a gentle slope toward the "canal". There was speculation, and it seemed to me, a bit of suspicion in Lil-rin's steady gaze.

"Why do you look at me that way, Lil-rin?" I asked. "Because I have dark hair, unlike your people?"

I thought perhaps she had not heard me, for she did not answer at once. For several moments she mused.

"Danan-lih, you are like no living man on this world!" she finally blurted out. Then, just as suddenly, she was all solicitude.

"I am sorry, I had no right to say such a thing. The ancient custom forbids anything that would make a guest feel uncomfortable. My offense is unpardonable."

That was my cue. "No it isn't, Lil-rin," I protested. "You and your people have been so kind to me that explanation is the least—"

"No, no!" she cried, jumping up and putting her hands over her ears. "I won't listen. You mustn't tell me anything. It wouldn't—"

A weird, shrill, wailing cry somewhere down the slope in front of us interrupted her. I'm not easily startled, but for an instant I felt a chill shoot up my spine. Lil-rin stood in an instant, rigid, motionless, staring pale and wide-eyed in the direction whence the sound had come.

"It's a birrok," she gasped, tugging at the quiver in which she carried her bolt-hurting tubes. "Run, Danan-lih, run! You can't fight it without bolts, and even then, you have to get it with the first shot, or—"

Then I saw the thing. It was a gigantic yellow-green spider. Its legs were fully twelve feet long. Suddenly, it straightened them and the furry body, which had been resting close to the ground, rose as though on stilts. Clearly, the thing sensed our presence and was looking for us.

Instantly, those legs began to move with amazing rapidity. The body seemed to swoop down and glide swiftly toward us with an easy, undulating swing. It would be upon us in a moment. Instinctively, I drew my automatic.

"Quick, Danan-lih! Run!" said Lil-rin, sharply, and stepped between me and the poisonous monster, her tube leveled.

There was a whir and a clang. The bolt shot true toward its mark. But, with unbelievable agility, the great spider leaped forward. Lil-rin uttered a little cry of despair, and threw herself in front of me. I squeezed the trigger of my gun. The shots blended into a roar as a succession of stabbing flashes leaped from the muzzle, for I emptied the whole magazine at the thing. As before, the beast leaped sharply to one side, but not quickly enough. The long legs crumpled up, and after one or two convulsive movements the thing lay still. At that, I believe it had dodged all but the first bullet.

LIL-RIN recovered before I could make up my mind to leave her long enough to go down to the stream for water.

"Wh—what was it, Danan-lih—that terrible noise? And you really killed the birrok? Impossible! H—how did you do it?"

I showed her the automatic, at which she gazed, fascinated, as I refilled the magazine. Then she looked up at me with her big blue-green eyes.

"You could have killed me just like that the day I shot at you," she said. "And I didn't have sense enough to take that machine-thing away from you!"

"Why, yes," I laughed. "Of course I could have, but I wouldn't—"

I broke off, for Lil-rin did not join in my laughter. Instead there was a look of almost tragic solemnity in her eyes.

"You not only spared my life when I treated you as an enemy, but saved it as well from the terrible birrok. My life no longer belongs to me, but to you—to do with as you see fit, Danan-lih."

She stood there, straight and slim and brave, her little jaws clenched in the effort to hold back the tears that would not be denied. Then, she whirled away from me and broke into uncontrollable sobs.

I wanted to comfort her, but I was badly flustered. I knew nothing of Martian customs at all. This girl was as much of a soldier as the men of her clan. Did she mean that I had a right to command her military service, or were her words to be taken literally? Lord, was I expected to claim her as my wife!

"Lil-rin," I said at last, and she swung around toward me with a pathetic little air of submission. "Come here and sit down again. You must listen and bear with me while I tell you who I am."

She nodded acquiescence, dabbing a bit at her eyes. She would not look at me. And that made it hard to begin. But somehow I managed it.

"If I only had half a dozen extra arms or legs, or something," I concluded, "there'd be some excuse for your believing my story that I just dropped down here from another planet. But here we are, with not as much difference between us as there might be between a man and a girt of two different races on Earth or on Mars, I imagine.

"It's a wild story. But it's the truth, although I can hardly expect you to believe it."

"But I do believe it," she said gently. "I've seen your space ship. I went back and found it the day after I took you to our camp. I was curious about you. I found your footsteps coming from the edge of the water, and I swam out. I saw something under the water, and I dived. I did not know what it was, of course, but I knew it must contain the secret of where you came from and I was worried. But I didn't tell anybody."

"And I know what's worrying you now," she said, finally looking up at me with grave, serious eyes. "It's ... it's me." She blushed frankly. "But we can't help it, Danan-lih, whether we like it or not. The law is:

"To him who has saved a life, belongs that life and the service thereof," she quoted.

She breathed almost with a sigh. "It has been that way among the Ta n'Ur for untold ages, since the days when fire rained down from the skies, gouging great scars across the face of our world, drying up the ancient oceans and destroying the Old Civilization."

"But Lil-rin," I protested, "I would not dream of embarrassing you, much less of making any claim upon you for what I did. I was saving my own life as well as yours. Besides, you might have killed the birrok with one of your own bolts."

"You can't get out of it that way," she said with a wan little smile. "It's the law. You saved my life. I belong to you. 'Ifs' and 'maybes' and 'perhapses' don't count here on Mars."

"Well," I said, "I can do with my property what I want, can't I? There's no reason why I can't give you back to yourself."

"Yes, there is. Because under the law, in a case like ours, it ... means ... it means—"

"Means what?" I had to ask, knowing the answer in advance.

"Marriage."

"But ... but—" I objected. "Suppose I were already married?"

"Then I would become your wife's slave," she explained unhappily, "and if I were already married, both my husband and I would become your slaves."

I didn't think much of that law. It seemed to have too many disadvantages.

"Do you mean to say," I demanded, "that if I were to save the life of your father, for instance, that he—the chief of your clan—would become my slave?"

"Oh, yes! That is, unless it were in battle, when all lives already belong to him anyway as commander-in-chief. In that event, you could establish no claim on him. But, if you were to save my father's life as you saved mine just now, he—Myar-Lur of the Ta n'Ur—could never submit to the indignity of becoming a slave."

"But how could he help it? You say it is the law, and—"

"He would kill himself," she said simply.

"Oh."

For a long time we sat without speaking. I was trying to get a mental grasp on this strange Martian custom and the problem it involved. Lil-rin sat dejectedly, gazing down the slope toward the undergrowth, in which the dead birrok lay.

Then there came to me a thought in which it seemed there might be a gleam of hope. I put it up to Lil-rin.

"I'm no Ur. Therefore the laws of the Ta n'Ur shouldn't apply to me," I argued.

This would be true if Captain Hanley were on Earth. Travelers in a foreign country, while subject to the civil and criminal regulations in that country, are still citizens of their own state. As such, visitors cannot be forced into any kind of contract-marriage if such is to their rights in their own nation. Foreign governments having diplomatic relations with other states all subscribe to "international law" or a set of customs which guarantees equal rights in commerce and the security of visiting citizens of another state.

"Yes, they do," she insisted. "We're within the treaty boundaries of the Ta n'Ur. And even though you are not one of us, you are subject to our laws."

"Well," I said in a clumsy attempt to comfort her, "I guess you do things differently on Mars. Anyway, we'll find some way out of it, Lil-rin. So—"

"What's the matter?" she asked in sudden anxiety, for my startled expression must have revealed something of the sudden fear that assailed me.

"You wouldn't think of getting out of it by—"

"By killing myself?" She smiled sadly. "No. I don't want to kill myself. I want to live. I ... oh—"

Without warning, she burst into tears and then began to laugh hysterically. She jumped up and started to run back to the camp, then paused and returned slowly.

"You wouldn't run away, would you?" She was pleading with me. "Because if you did, they'd cast me out as a deserted wife."

Then she was gone, her slender little figure flashing in and out among the pale green stems of the forest as she ran back toward the camp.

It was a crazy situation all right. But, no crazier than the fact that I was on Mars. I pinched myself hard and winced. No, this was all real enough. I gazed around at the pale yellow-green vegetation, with its strange, unfamiliar forms. Low over the horizon hovered the sun, not half the size it should be to earthly eyes.

Overhead, the strange tiny moons of Mars, moons only a few thousand miles distant and quite visible though it was broad daylight, hurled themselves across a cloudless sky with a speed that was visibly tremendous. Scarcely a thing on which my eye rested had any aspect of familiarity to me. Yet, everything was vividly real.

As to the girl, well, I didn't see what I could do about that. I sighed, and bent my steps slowly back toward the camp of the Ta n'Ur.

By the time I got there, the entire clan was drawn up in military array. Lil-rin, pathetically courageous, stood with her father several paces in front of the line. When she saw me, she said something to Mornya and stepped forward to meet me.

"We have to go through with it, Danan-lih," she murmured. "Don't hate me too much."

"Don't worry, little one," I whispered. "They make you my slave, or wife, whichever it is. But they can't make me treat you like a menial. You shall always be as free as you are now," and I gave her a little squeeze to reassure her.

"Your kindness makes me more your slave ever," she whispered in reply. "Now come."

She led me before her father. He read some formula rapidly from an inscription on a metal plate—it looked like gold—which he took from a leather case slung over his shoulder. He spoke rapidly in some other tongue than that used normally by Ta n'Ur, so I could not follow him at all.

Then Lil-rin bowed her head, and he placed my hand on her fair hair. Were there tears in her eyes? I wasn't sure. She kept her head averted from me.

The simple ceremony was over in a few moments. The clansmen took it all very solemnly. They gathered in little groups as they walked away, and there were many curious glances thrown over shoulders at us.

Mornya held out his hand to me, and I grasped it, Earth fashion. But I could sense that there was no excess of warmth in him at the idea of Lil-rin's marriage to me, an unknown and mysterious Outlander—for Mornya, of course, did not know my full story. Lil-rin had not dared tell him, nor in all probability would he have believed it.

He looked at me searchingly with troubled eyes. I stammered some promise to him that I would always consider Lil-rin free, but I don't think his mind was on my words. He muttered a perfunctory benediction of some sort. Then he too turned and walked rapidly away, leaving us alone together in the center of the big square.

THERE were no festivities. Nobody seemed to be happy. Certainly Lil-rin and I were not. We had gone through a meaningless formula, one that was acceptable to none of us. Yet, there seemed to be nothing that could be done about it. Lil-rin timidly interrupted my musing. "I shall get our supplies, Danan-lih, if it pleases you. And—"

"Supplies?" I interrupted. "What for?"

"We must leave the clan for three days," she explained. "Our wedding trip, you know."

"But look here, Lil-rin," I objected. "That isn't going to mean a thing to us. I don't see why. We don't actually have to go, do we?"

She nodded her head. "It is the custom. We won't need so very much. I'll be back with our supplies presently."

I stood there frowning. The clansmen avoided me. I saw too that they avoided Lil-rin. The newly wedded bride and groom were to be ignored, cast out, avoided for an arbitrary period of three days, it would I appear.

Lil-rin returned presently, laden with bags of food and weapons. Uncomfortably I remembered the birrok. Strapped to her back was one of those light metal tent-frames, and rolled and thrown across her shoulder was the tent itself. She staggered a bit under the burden. I hastened to her side, but she motioned me away.

"No, no, Danan-lih!" she said. "It is I who am the slave-mate, not you. It is I who must carry the burden."

"Nonsense!" I began with some heat.

"It is the law," she said simply. "It is I who will suffer if you do not let me obey it."

I glanced quickly around. The clansmen were watching us intently. So I had to give it up. I shrugged my shoulders helplessly. Feeling meaner than I had ever felt in my life before, I followed Lil-rin as she staggered through the triangular gate, away from the gleaming walls of the fortress-like edifice, off into the yellow-green forest.

But once beyond sight, a single bound carried me to her side. Heedless of her protests, I took all of the burdens from her. To my Earth muscles, the load was trifling.

"And now," I laughed, "where do we go from here? And why didn't you bring two tents?"

"Anywhere you say," she rejoined with the nearest thing to a smile since I killed the birrok. "And I shall sleep outside, if you want me to."

"You'll do nothing of the sort," I muttered. "I will."

There were low hills a few miles beyond the canal, and we turned our steps in that direction. Lil-rin had regained a bit of her gaiety, but was clearly ill at ease. We chatted in more or less desultory fashion as we went along.

At a point somewhat higher up than that at which I had concealed my little space ship, we prepared to cross the river. I thought with a little pang of my spacecraft. Perhaps Lil-rin would like a ride in it. Why-why, I might even take her back to Earth with me!

But, no. It wouldn't be as though we were really in love with each other—had really ever been married. So I left my thoughts to myself.

We paused at the bank of the stream. All of a sudden, Lil-rin gave a shriek of alarm. I looked at her quickly. I had a fleeting impression of her startled glance at something behind me, of a twanging noise from that direction. Something hit me with a tremendous blow on the back of the head, and I knew no more.

I don't know how long it was before I revived.

The pain in my head was terrific. Only by the most desperate effort of my will did I avoid slipping off into unconsciousness again. Little by little, I struggled to my knees and looked around me, fighting the nausea in my stomach.

Lil-rin was gone. So was all our baggage. There were marks in the soil as though a struggle had taken place. I staggered to my feet. My gun was gone from my thigh holster. But I still had the little automatic inside my shirt.

It was not hard to tell what had taken place. An abduction! I had been shot down from behind. Lil-rin had struggled, but had been overcome and carried away. So hasty had been her kidnappers that they had not searched me thoroughly, which was certainly a break from my viewpoint.

It stood to reason, of course, that Lil-rin's abductors had not been members of her own clan. Who, then, were they? Members of a similar clan of nomads? Or men of another race, from north of the barrier?

Well, what to do? After a little of my strength came back, I got into action. My space ship was under the water where I had left it. But the marauders apparently had found it, for one of the hatches—and not that of the airlock—had been opened. The sphere was filled with water. It would have to be dragged ashore and rolled over to be emptied.

For a moment, I hesitated whether to return to the encampment and arouse the Ta n'Ur or not. But it would mean further loss of precious time.

So I didn't give that angle a second thought. And a moment later, my helplessness gave way to sudden excitement. For my desperately seeking eyes had caught marks on the bank of the stream—boat marks, as though a water craft of some sort had been run up there. It was easy to see that the stream did not flow much farther in that direction. The presence of those boat marks indicated flight in the opposite direction! Away I went upstream along the canal-valley in prodigious leaps of fifteen feet and more.

On Mars, Captain Hanley's weight would be one-third of normal. But the difference in gravity would not affect his muscular strength. Hence, on Mars he would be three times as strong as on Earth.

I was confident that my superiority over the Martians in speed, in strength, and in the weapon I still cuddled beneath my arm would enable me to overcome great odds. Time was the important element right now.

At length, I came to the gap in the great quartz barrier, where at some far-distant age in the past the meteor, which had plowed this canal-scar in the face of the planet had cut through. As yet, I had caught no glimpse of a water craft.

A faint hail reached me from the glittering rocks above, and a figure stood forth, arm upraised.

I recognized him as one of the Ta n'Ur. I was up in the face of the jagged cliff and at his side in a few moments. It was a young man named Uldor, on guard duty at the Gap.

A "wheel-boat," he told me, had gone downstream and returned. But he had seen no one in it except four Northerners, with a crew of dulyals at the wheels.

"Still," he added, "the forward deck was covered. Many people might have lain bound and gagged beneath that cover.

"It's not part of the Ta n'Ur's duty," he went on, "to interfere with the Northerners themselves in their very rare passages back and forth through the Gap. Our obligation under our treaty with them is simply to prevent migrations of the wild dulyals."

As I dropped back to the canal gap and leaped away toward the North, I saw Uldor racing madly back toward the encampment to pass on my alarm.

North of the barrier the character of the country changed somewhat. It was wild, but the vegetation was more prolific, and there were evidences here and there of ancient irrigation ditches laid out in regular rows. The canal itself was a shallow valley gouged across the face of a level plain. In its center the stream had cut a deeper and less regular course.

Several miles north of the barrier I came upon the first evidence of habitation. It was a small structure, but built of that same iridescent material of which the fortress occupied by the Ta n'Ur had been constructed. And like that mysterious edifice, it was a monolith, very old and worn.

I redoubled my efforts and was passing the spot in mid-leap when a figure rose suddenly to contest my way.

It was my first glimpse of a Northerner. In the split second that elapsed before I hit him, my eye photographically registered a figure in flexible armor of yellow, overlapping metal plates. There was a conical helmet that guarded the nose, ears, and neck as well as the head. Curved plates fitted over the shoulders; arm-pieces cleverly overlapped at the elbows. Completing the outfit were a skirt or kilt on which more overlapping plates were fastened, and what might be described as metal boots, hinged at the ankles. The fellow, in a panic of frantic haste, was trying to bring one of those long bolt-throwing tubes up at me.

Evidently, my great leaps and speed completely upset his judgment of distance. My heavily shod foot came down on the tube, and we went crashing to the ground with a great clangor of metal.

I was on my feet in an instant, but the Martian did not rise. There was a grotesque twist to his head. He had fallen, clumsily, and his neck was broken.

His armor, I thought, might be useful to me as a disguise, and for an instant I considered appropriating it. But on second thought, I decided not to do so. It would be too awkward.

I turned away and was about to leap on up the canal-valley, which was becoming wider now, when I started back in surprise and alarm. Directly in my path was a mounted Martian. But it was the character of his steed that startled me.

It was not a horse at all, but the only thing I could call it in any tongue of Earth would be a "dog." It was as large as a small horse and distinctly canine in appearance and in the intelligence of its eyes, as it stood there, softly poised, watching me as intently, as was its rider. The Martian was clad entirely in soft yellow leather, richly embroidered with sparkling beads. But his garb was not like that of the Ta n'Ur. Instead of a loose sleeveless shirt, he wore a sort of collarless fitted jacket with long sleeves and a sash of scarlet leather. In place of the kilts, he wore tight-fitting leggings which covered his limbs entirely.

He sat well forward on the back of his strange mount, with his toes hooked into peculiar stirrups just back of and under the animal's forelegs. The saddle was, in reality, a combination saddle and collar with a metal handle on the top of the latter part. There was no bridle. The rider evidently guided his mount by voiced commands, or possibly by pressure on the collar handle, though I judged the handle more to aid him in keeping his seat.

FOR a moment we confronted each other, and in that brief spell I was conscious of a liking for the handsome young face before me. In it was nothing of fear, though this Martian knight had no weapon that I could see. But, he sat watching me with a shrewd and alert interest.

Then he raised his arms and held them wide, palms forward, in the Martian gesture of friendship. I glanced, uneasily, at the body of the dead guard. He noted it, too.

"It is nothing," he said. "An accident. I saw it all. The fellow exceeded his duty in trying to stop you without first challenging."

He paused a moment. "You are the 'mysterious guest' of the Ta n'Ur that Mornya was telling me about. I have never seen hair as dark as yours. What are you doing here?"

"Are you Mornya's friend?" I asked softly, my hand slipping inside my shirt until it closed over the butt of the little automatic. I thought his eyes narrowed a bit at that. But he showed no alarm.

"I am Mornya's friend," he declared flatly. "It was I who negotiated the treaty for the Ta n'Ur for the Council of Alarin, the Greater Lords of the Polar Cities."

I was quite sure then that this lad had had no part in the abduction of Lil-rin, and determined to take a chance on him. After all, I would need help of some sort in rescuing the girl. So I told him how I had been struck down, and of the "wheel-boat," as Uldor called it. His astonishment and indignation were obviously genuine.

"And just what were you about to do when we met?" he asked, giving me a curious look.

"Follow that wheel-boat and rescue Lil-rin."

He shook his head slowly in negative judgment. "You would not have had a chance," he said. "In the first place, you could not have overtaken it. I saw the speed at which you were leaping. I also saw the boat. In the second place, either Gakko, Alar of Gakalu, or one of his Epsin-Lesser Lords was in charge of it. Then there were the dulyals at the wheels. They can fight, you know; and when handled by clever commanders, they are terrible adversaries.

"Oh I know of the bolt-thrower inside your garment, which your hand now rests on. I heard of that also from the Ta n'Ur. But there were fifty dulyals in that boat, and I don't think you have that many bolts in your weapon."

Discouragement must have shown in my face, for he laughed.

"But it's not so hopeless as all that. A plan is taking shape in my mind. Gakko is no friend of mine, nor of Layani, the Alar-Lur, Supreme Lord of the Cities. This abduction is surely Gakko's work. It is rumored that he has stolen girls from the Southern clans before, that he has several of them among his wives."

He smiled reassuringly. "Come with me. We must talk this over. We have, I think, a great opportunity to outwit Gakko."

"But what of Lil-rin in the meantime?" I objected.

"She will be all right. Gakko would not dare harm her until he had her safe within his power at home, in Gakalu. Besides, he must hasten to attend a council of the Alarin to be held on the Island in two days."

I consented. There didn't seem to be much else for me to do. The young Martian, who informed me his name was Banur, and that he was one of the Lesser Lords of Borlan, the land adjacent to Gakalu on the Polar Sea, made me mount his dog-steed behind him. At his command the animal set off, leaping and scurrying up one of the ancient irrigation ditches away from the canal-valley.

Across a cultivated plain we scurried, between fields of melon-like plants, toward a range of low, verdure-clad hills. It took some skill to cling to the great dog's back, but so fast did he run that it was a matter of minutes only before we had plunged into the vegetation on the slope of the hills. The animal was now scrambling upward to where, in a clearing, stood one of those great iridescent monolithic fortresses such as that occupied by the Ta n'Ur.

In through a triangular gate we flashed, and as the great dog came to a slithering stop, uttering a thunderous bark, a number of dulyals ran forward to take charge of him. It was the first chance I had had of seeing these near-human apes who served the Northerners as slaves.

Very manlike they were in build and carriage, and covered from head to foot with yellow fur. But their eyes, so it seemed to me, did not shine with even as great intelligence as those of the dog-steed.

I mentioned this to Banur.

"They are not as intelligent," he replied. "But they are more dependable, when through several generations of captivity they have been trained to their tasks. But they have their limitations. These fellows, for instance, are of use only in the steed kennels. Those over there have been trained to till the fields. They are good for nothing else.

"These," pointing to several who were patrolling the walls, armed with spears "are good soldiers, although quite incapable of acting on their own initiative. They can comprehend only a single military command at a time."

"I see very few humans," I remarked.

"No," he replied. "There are only a handful here, a few Ildin—that is to say, Freemen—and a dozen or so slaves. You see, this is merely an agricultural outpost. But its supervision comprises part of my duties, and I have to make periodic visits here."

Banur insisted that I change from my Earth clothes and put on a Martian suit, which he found for me among his stores. After that we tarried at the post only long enough for refreshments. While we drank "lilquok," that invigorating beverage the Martians make from one of their varieties of giant melons, Banur explained to me something of the law which held together the Northern Cities.

Seven lands bordered on the Polar Sea, ruled by seven Alarin. One of these, Layani, Alar of Hok-lan, was by election Alar-Lur, or Supreme Lord of the Council of Alarin.

Theoretically the Alarin were as subject to the law as the Epsin, or Lesser Lords, and the Ildin, or Freemen. But as a matter of fact, they enjoyed absolute power; for accusations could be brought against a Martian of the Polar Cities only by one of equal or superior rank.

There were few of the Alarin who would not welcome the retirement of Gakko from among them, but none who would risk the precipitation of a general war. Gakalu, the land ruled over by Gakko, was one of the richest and most powerful of the confederation, with strong natural barriers, a larger population of Ildin and slaves than any other land, and by far the greatest force of fighting-trained dulyals.

Likewise, no other Alar was anxious to give Gakko any cause for offense that could be avoided.

"But," Banur suggested thoughtfully, "I think that the man with a just complaint against this tyrant, and the courage to slay or strip him of his power, would not be regarded as an enemy. Not, at least, by the Alar-Lur, the Supreme Lord, who fears Gakko's growing influence. Nor the rulers of Borlan, Tuskidon and Ilmo.

"The Alarin of Trilu and Yonodlu, the lands beyond Gakko's on the other side of the Sea, are definitely his supporters. But I do not know that even they would necessarily feel injured by his elimination.

"Certainly it would be their best policy to cultivate the favor of the other Alarin, in the event that Gakko were deposed or slain."

Politics, it would seem, is the same on any planet with an intelligent population. It is not beyond the bounds of reason to suppose that the present crisis now facing Earth may not at some time have been duplicated in a remote planet.

Banur paused uncomfortably. "Now ... Dr ... I don't know whether you would resent being made use of in this way. You see, I am being perfectly frank with you. But you appear to be determined to fight Gakko single-handed anyhow, and—"

"Well, I thought it might not be displeasing to you to know that you can count on a certain amount of secret help since your decision has already been made. Of course, if you fall into Gakko's hands you must realize that no Alar could go very far in giving you protection. The whole situation is rather delicate. I'm sure you can understand our position," he added hastily.

I grew thoughtful at this. I did not like the idea of plunging into the midst of the political turmoil in a world with which I was virtually unfamiliar, of being made a cat's paw by certain of its rulers. I had not leaped all this distance from the encampment of the Ta n'Ur to become an assassin of Martian kings. I merely wanted to rescue Lil-rin and punish the villains who had abducted her.

"Of course, you are under no obligation to accept any aid at all," Banur put in shrewdly. "My only thought was that you want to rescue the girl and—"

"I'll do it!" I said, jumping to my feet.

"Good!" echoed Banur exuberantly. "Come."

A FEW moments later found me galloping with Banur at the head of a band of mounted dulyals, Banur had supplied me with a great, powerful brute of a dog to ride. The beast looked understandingly at both of us when Banur turned him over to me. Wagging his immense tail, he accepted me from that moment as his master.

Both the dulyals and the dogs on which they were mounted accorded me the same understanding, at a word from Banur. The young Martian then drilled me in the words and methods of command necessary for their control.

The most remarkable affection existed between the dulyals and their mounts. There seemed to be a perfect understanding of commands and coordination of action. The dogs were more intelligent than the great dulyal apes, but of course lacked much of their physical prowess. Both, Banur explained, were terrible in battle, although quite docile to the commands of their master, whoever was the leader selected by the Northerners for a particular task.

To me, it was also comforting to learn that the dulyals were trained to the use of the spear and a short, broad-bladed sword almost like a cleaver, and that they carried these weapons with them.

"We're taking an overland short-cut toward a little seaport at the boundary of Borlan and Gakalu," Banur said. "It is there, undoubtedly, that Gakko has taken Lil-rin. For once out on the Sea, she will be in Gakalun waters, and he will have a run down the coast of only some seven hundred miles to Gakko's own city."

"Will we catch them there, do you think?"

"Not we," he said frankly. "Possibly you. But if you can't overtake them before they reach their own territory, I should advise you not to try it, but to journey on leisurely along the coast of the Polar Sea until you arrive at the city of Gakalu.

"Establish yourself there as—let me see, now ... as the son of a rich merchant of Ilmo, for that is the land farthest away from Gakalu across the Pole, and you would be less likely to meet Ilmonions in Gakalu."

For the rest of our journey, as our great dogs tore along with us at amazing speed and the cavalcade of dulyals raced after us, Banur supplied me with much information as to the customs of the Martians.

At length he motioned me to give the order to halt for the dulyals and dogs now looked to me only as their master, as Banur himself had previously commanded them. He pointed toward a silvery sheen on the horizon beyond a growth of short ferns.

"It is the sea," he said. "Your way lies straight ahead. You will see the village after a little bit. Luck be with you, and may you return safe from this daring adventure, for there are many things I would like to discuss with you. Things which I feel I cannot talk over with you at this time. Besides, there has been so much information to give you."

"On what points are you curious?" I asked, having a pretty good idea of what was on his mind from the surreptitious glances he had been casting my way.

"Well, for one thing, your coloring is like that of no man I have ever seen," he stammered, and his face grew red. "Indeed, throughout all history, even back through the legendary period of the great Rain of Fire, there is no mention of men with brown hair and deep blue eyes. You appeared suddenly—from nowhere it seemed—among the Ta n'Ur. At least, so Mornya told me.

"Among the Southern Clans, it is considered bad manners to pry into the affairs of strangers and guests." He smiled deprecatingly. "You see, our own customs are somewhat different."

"Does history or legend shed any light on the lands below the equatorial desert?" I asked him.

"None," he admitted. "It is a great subject for speculation among the wise men as to what may be on the Southern half of the globe. We know, of course, that we do live on a globe and not, as it might seem, on a great, flat circular world. But somehow I do not believe you crossed that desert. Neither do the Ta n'Ur."

I laughed. "What do you think, then?" I asked.

"My thought is so wild that I hesitate to take it seriously." He was looking at me keenly. "Have you ever watched the skies at night, and gazed on the Green Planet?"

By Green Planet, Banur meant of course Earth, for that is how Earth would look to the Martians.

"Often," I had to admit. "I've often seen it from a distance." Well, considering the many space voyages I'd made, that was true enough.

"Have you ever wondered whether it was a habitable world?"

"No, I never had to wonder about it."

The look of disappointment on his face was eloquent. He had been shrewd, but he had been frank, too. I could but reply in kind.

After a pause I added: "I know that it is."

"What?" Banur shouted. "Then you really—"

"Yes. That is where I came from. Earth, we call it."

Banur acted like one suddenly bereft of his senses. He shouted and laughed, waving his arms madly. Then as quickly he turned and was gone, his great dog racing and bounding across the plain away from me, back in the direction from which we had come.

Amazed and puzzled, I could only gaze helplessly after him. And by the time I thought of calling out to him, he was beyond hearing.

Then came the thought of little Lil-rin. Well, that was my job, wasn't it? So, with considerable misgivings, I turned toward the distant Polar Sea. I shouted "Hep!" and pointed forward. In an instant, followed by the dulyals and the dogs, I was bounding along, frequently grabbing at the saddle-handle to steady myself, and muttering the while a silent prayer that at least I had had experience riding horses.

To my earthly eyes the village was indeed strange. I was astonished to find that most of the "buildings" were underground. In this they were quite unlike the only other Martian structures I had seen the ancient, iridescent monoliths.

The modern Martians, as I was to learn, dug their cities and villages deep underground, with thick-walled superstructures. Soil and rock were mixed with a red cement, made into large slabs or bricks. The superstructures were little more than entrances and anterooms to the quarters beneath.

Remembering what Banur had told me that the "gasto," or inn, would be located on the outskirts of the villager held up my hand. The great dogs behind me slithered to a sudden stop, as did my mount.

I looked around for a shaft of stone or cement bearing a picture or a carving of a dog's head. A metal rod projected from a hole in the ground beside it. This I lifted and let drop again. Somewhere down in the ground there was the sound of a gong, and the metal door in the wall before me was opened.

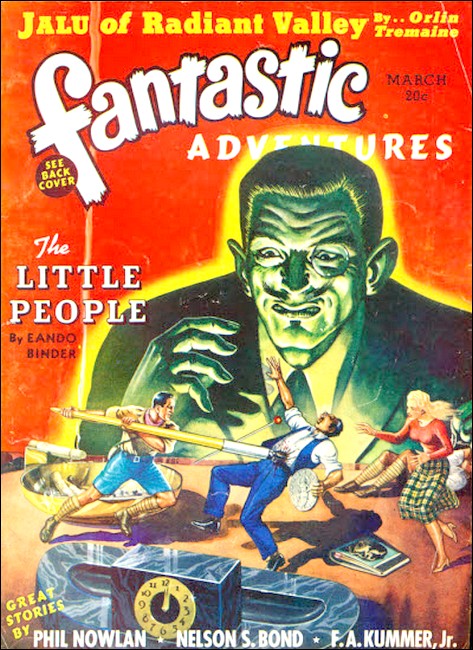

Fantastic Adventures, Mar 1940, with

second part of "The Prince of Mars Returns"

Dan Hanley fired over his shoulder at their

pursuers and was rewarded by a hoarse yell of pain.

THERE, standing before me, stretching his arms wide and bowing with some difficulty, the first fat man I had seen on Mars.

On the far side of the building I found were cage-like structures for the dogs and the dulyals. After ordering my animals to remain in them until I called, I followed the innkeeper back around the building to the metal door.

From here, a circular ramp led down to the lower levels. I stopped at the first level to pay my board and lodging with the heavy little red beads (rubies, I think they were) that the Martians use for money, since gold is far too plentiful.

I drew a puzzled glance from mine Martian host when I laughed because the little cage at which I paid was so much like a cashiers corner in innumerable little restaurants on a planet millions of miles away.

My room proved to be on the third level down.

I was shown from my room to the "moccor," which I suppose would be translated in English variously as "lobby," "bar-room" or "restaurant." It was on the first level below ground. Here, gathered about the great solid, carved blocks of quartz that served as tables were seated some score or more of Martians, all of the Ildin class, or Freemen. This, I gathered from the green sashes they wore like my own with which Banur had outfitted me.

In a far corner of the room was a little party of four, obviously strangers to the village, for like myself they seemed to be interested in their surroundings. They surveyed their neighbors with some curiosity. Two of them were Epsin-Lesser Lords. They wore the red sash distinctive of their class. The other pair were Ildin.

A couple of slaves, obviously members of the party and not inn attendants, garbed in the black that denoted their position in life, hovered in the background with big bowls and jugs.

There was a vacant table near the group, and I moved toward them, as unconcernedly as I could. They seemed to take no notice of me.

Almost immediately the name "Gakko," although uttered in a hushed tone, caught my ear. I strained to hear more, but without much success for awhile, for one of the inn's servants was placing my food before me.

Later I heard the city of Gakalu mentioned a few times, and there was something said about the seaworthiness of a certain wheel-boat, and the necessity of guarding someone well under pain of Gakko's violent displeasure.

I had no doubt it was Lil-rin to whom they referred, and that this was the party I was after. Certainly there was something furtive about their manner, something sly that argued there was no good in the business that had brought them here.

I felt for the little automatic under my shirt, and casually unfastened the garment a bit at the neck that I might reach it quickly. None of those in the room had taken particular notice of me as yet, and I was thankful for the rather dull light thrown by the crystal bowls placed in recesses along the walls, in which wicks floated.

I was thankful, too, for the Martian custom that did not require men to uncover indoors, although women were supposed to—a curious reversal of the practice on Earth.

I was trying to decide upon my next step when fate took the initiative.

There was a sudden commotion near a triangular door that gave access to one of the lower level ramps. A slender girl in the black garb of a slave dodged frantically among the tables toward the group I was watching. Her progress was marked by growls and resentful glances.

One or two Ildin half rose in their places, then sank back again quickly enough when they saw the red sashes of the Epsin, who had risen in some alarm as the slave girl fought her way toward them.

But, once she had made her breathless report, the four men, followed by the girl and the two slaves, dashed for the ramp.

In the excitement, I followed.

A turn in the ramp muffled the commotion behind us, and I heard the patter of the conspirators' running feet as they circled downward. I leaped after them, closing the gap quickly, and stopped barely in time to avoid turning another corner and crashing full into them. They paused at the fourth level down and threw aside the leather curtain that concealed a triangular door. With a rush they were through.

In addition to the two Epsin, there were four or five Ildin in the room, and several slaves of both sexes. They had spread out and were cautiously closing in on a far corner of the room where a slim girlish figure, almost denuded of clothing and bleeding from an ugly gash on the arm, stood at bay.

In one hand she had a spring-gun, with which she kept threatening her enemies, as one or another of them took a chance and tried to advance a step. In her other hand she held my large automatic.

Here then was Lil-rin of the Ta n'Ur, the golden-haired, blue-eyed Amazon of the Southern clan whom I had sworn to rescue. Lil-rin, gloriously waging the battle of her life against a band of Martian vultures, who leered evilly at her gleaming body, yet respected the deadliness of her weapons. Lil-rin—my wife! Her clear sweet voice rang out now with scorn as she taunted and defied them. And they howled back like a pack of wolves.

"Stop this folly! Throw down that weapon!" roared one of the Epsin, who seemed to be the leader, as he pushed his way forward to face the girl.

"Be careful, Uallo," cautioned the other noble at his elbow. "She means it. She'll do what she says. I know these clansmen of the South. And the Ta n'Ur are the most desperate warriors of them all." The other hesitated. "But this is ridiculous. She is only a girl, and—"

"The daughter of their leader, their Myar-Lur," interpolated the cautious one. "It is best to take matters slowly."

It was the psychological moment. I acted.

Stepping inside the door, I raised my little automatic and fired a shot into the ceiling. The reverberation in that heavily walled room was terrific. It seemed to stun the Martians. Demoralization was in their faces as they swung about and saw me there like a statue, my gun half raised and a tiny wisp of smoke curling up from it. They shrank from me.

"Come, Lil-rin," I said. "We must get out of here. You go first and clear the way. Use my gun if you have to, but I think there are none above who have an interest in stopping us. I'll hold this scum back."

Lil-rin looked at me like one who sees a happy vision and doubts its reality. I never saw her look more beautiful than at that moment, disheveled as she was and bleeding from the rather ugly gash in her arm. But there was no indecision in the girl.

With her little shoulders thrown back, her chin high and an expression of regal contempt for Uallo and all his followers, she stepped briskly to my side. For just an instant she paused and looked at me, an inscrutable something in her clear blue eyes. Then, she slipped through the curtained door and was gone.

Her disappearance seemed to break the spell.

"Stop them! At any cost!" Uallo roared, and threw himself recklessly at me.

Instinctively the rest leaped with him. Three or four times my automatic roared; four of the enemy pitched headlong. But the distance between us had not been great, and even those who had stopped my bullets plunged into me as I went under from the combined rush, pulling the leather curtain on top of me as I fell outward through the door.

As fast as I could press the muzzle of my gun against a new mark I pulled the trigger, but my head was entangled in the curtain and so many Martians had fallen on top of me that I could not at once wriggle free.

I fired my automatic as fast as I could pull the trigger.

It was then that I heard the heavier roar of Lil-rin's gun. Five times, at evenly spaced intervals, she fired, evidently aiming with calm deliberation. Then all was quiet, save for the groans of the Martians around me and the curtain was lifted from my head. I struggled to my feet, to meet Lil-rin's anxious and inquiring gaze.

"Are you hurt, Danan-lih?" she exclaimed. "I was afraid they had gotten you. Now what shall we do?"

In a few breathless sentences I explained to her how Banur had helped me, told her of my dulya cavalcade as we raced up the ramp. We found the moccor, the inn's public room, deserted. Nor did anyone appear to halt us before I blew a shrill call on the whistle Banur had given me. The great dogs and the yellow apes came racing to us around the corner of the building.

I made two of the dulyals ride double, and Lil-rin leaped on the back of the spare dog after I had bound her injured arm with a strip torn from her garment. And then we were racing away from the village, through the yellow-green ferns and back across the plain toward Bartur's post.

"YOU'VE canceled the debt of life forfeiture, Lil-rin," I said to her.

She gave an odd, quick look and laughed. "No, that didn't count. I told you, the slave is obligated to protect the master in battle. And besides, that is the second time you have saved my life. I'm doubly forfeited now, Danan-lih, whether you like it or not."

"I don't—I mean, I do like it—that is—what I mean—I'm not accustomed to enslaving girls," I stammered. "Besides—"

Lil-rin sighed. "Then you must be awfully good at things you really are accustomed to," she said, and looked abruptly away over the yellow-green prairie as our strange cavalcade thudded madly on.

For an instant my heart pounded. Did she mean ... But, no, that couldn't be. Certainly Lil-rin did not want to be a slave. She, daughter of the chieftain of a warrior clan. Slave! Why, the girl was technically and officially my wife!

There was no pursuit. Lil-rin and I between us had accounted for nearly all of Uallo's party. It was my impression that none had escaped, except perhaps a couple of the slaves.

Presently the girl's eyes caught my own. "Before three suns have passed, the Ta n'Ur and our allies among the clans will be in arms against some or all of the Polar Cities," she said simply.

Then, suddenly, Lil-rin was all emotion, "Well, let it be!" she cried fiercely, clenching her little fists. "It had to come! The legend must be fulfilled!"

"Legend? What legend do you mean, Lil-rin?"

But that was all that she would say...

In due course we neared the agricultural post from which Banur and I had set forth such a short time before. Not twelve hours had elapsed.

Captain Hanley's watch was of great convenience. He had found that the Martian day was almost the same as that on Earth.

As we drew nearer an Ildin, or Freeman, rode forth on a dog to meet us. But he paused suddenly some two or three hundred yards away, gazed intently at us, then turned and raced madly for the post, waving his arms and shouting something. But he was too far ahead of us for me to hear what it was.

I thought no further about the Ildin. But when we arrived, I was amazed to see no less than a hundred and fifty spearmen, in full armor, drawn up in military formation. And at their head, in golden armor, a vermilion cloak over one shoulder, stood Banur of the Gap. In the rear stood rank after rank of dulyals, minus armor, but armed with those terrible, short, broad-bladed swords. I halted in surprise.

As if he had been waiting for this signal, Banur tossed his spear into the air.

"Hail to the Hero of the Legend!" he shouted. "To the Alar of the Green Star!"

In amazement I turned to Lil-rin, and to my still greater astonishment found her not surprised at all.

"I knew it," she was saying softly. "From the beginning I feared it!" And there was something of both tragedy and pride in the tear-dimmed eyes she turned to mine.

"You heard him say it," she continued. "The Legend of the Green Star! And you, Danan-lih, are the Hero of the Legend. And the Legend shall be fulfilled!"

And then this little golden Amazon with the green-blue eyes did the last thing I had ever expected to see her do. She fainted and tumbled headlong from her saddle.

In an instant I had leaped from my own mount and picked her up in tender arms. Poor kid! She must have gone through a lot while in the hands of Uallo and his villains.

Banur, too, came running to us and offered to carry her into the little fortress.

But Lil-rin on Earth would have weighed no more than a hundred and fifteen or twenty pounds. To my sturdier Earth muscles, she seemed no more than thirty-five or forty pounds. I lifted her like a child and carried her into the building.

THAT night, while the bright little moons of Mars sped swiftly across the starry sky and Lil-rin slept, Banur told me of the Legend of the Green Star.

"It is a strange mixture," he said, "of historic fantasy and more definite tradition. It has a great hold on the popular imagination, not only among us of the Polar Cities, but among the people of the Southern clans as well.

It is said that once, untold ages ago (Banur went on), no men lived in this world of Mars, which was inhabited by great beasts and by the progenitors of the dulyals, who were supposed to have stooped a bit as they walked, and to have had tails by which they could hang from trees. A quaint idea, that. To think of an animal using its tail in that fashion!

But there was another world, where the vegetation was of a much darker green, and where there were great seas and oceans, yet too much land for this world was larger. And, another quaint conceit, there were men of many different colors living on this world: black men, brown men, red men, white men with yellow hair, and white men with black hair.

And among all these different kinds of men there was one race superior to the rest, for they were far advanced in intelligence, in the arts and sciences, and were able to make war with lightning and thunder.

Indeed, they had machines which would run themselves and accomplish in trifling time the work of many salves laboring over a long period. And over these men—the men with yellow hair and green-blue eyes—there ruled a chief whose name was Danan, Alar of the Antin, or Island Men, as these yellow-haired ones were known.

For although their land was large, it was surrounded entirely by an ocean, and thus separated from all other lands.

Now it happened in the course of time (Banur continued) that from out of the void of space, there came rushing a little world or planet that had nothing to do with the sun. Danan's wise men, after making many careful observations and calculations, told him that this planet seemed certain to hit the Green World on which they all lived.

That, in particular, this little planet would probably strike the Atl or island, on which they had their dwelling places. Danan's wise men even went so far as to say that the roving planet would most certainly destroy the Atl, probably the whole world, so that all men would be killed.

It was then that Danan put other wise men to work, constructing a great ship which would fly through the void of space, just as many of the ships of the Atl Antinat that time were able to do. Together with many thousands of his people, Danan set forth, fleeing through space from the doomed world in the hope of finding another which would be habitable.

In time they are supposed to have landed here on Mars, and after centuries of struggle, to have slain all the great beasts and domesticated the dulyals.

But in the meantime, through the great lenses which they used to magnify sight, they saw the little world hit the big one from which they had fled and then bounce off again, taking with it much of the material of the big world. This became a moon, only much farther away than our two moons, and much larger.

But only portions of the big world appeared to have been destroyed. It seemed to the wise men who watched the collision, that the big world had not been hit where they thought it would be, but on the other side.

Now (said Banur) there had been many more thousands of the Atl Antin who had refused to risk the voyage away from the Green World with Danan, their Alar. Danan wondered if these people might not have escaped annihilation, after all. So he had his great space-traveling ship repaired, and left on a visit back to the Green World, promising to return to his people here.

That, according to the legend, was the last ever seen of the Alar, Danan.

But belief or fancy, or whatever you choose to call it, has persisted through the thousands of years since then that one day, in fulfillment of his promise, Danan would return.

Great interest, too, has centered around the romantic side of the legend, of which there are many versions of widely variant nature. The oldest and simplest form of the legend has it that Danan had no wives, and that when his people were reluctant to let him venture the journey back to the Green Star, he left behind him the girl of noble blood who was betrothed to him, and whom he loved dearly, as a pledge of his return." (Banur concluded.)

To say that I listened to all this in astonishment would be putting it mildly. Banur's description of the catastrophe to the "Green World," his reference to the "Atl Antin" left me gasping. Do we not have our own legends of the lost land of Atlantis, which was supposed to have existed somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean?

Do not other legends maintain that it is from the immensity of the Pacific that the material forming the moon was thrown off? And have not many scientists in recent years receded further and further from the position that the history of man is as simple as that of an evolutionary rise from animalism and savagery?

Have these learned men not inclined more favorably to the theory that innumerable prehistoric civilizations, of which no traces are left, may have preceded our own?

"And now," Banur said solemnly, "we come to the final links in the chain of events. Your name is Dan Hanley—he pronounced it "Danan-lih"—while the hero of the Legend is Danan, Lil-rin is of the Ta n'Ur daughter of the clan's chieftain. It is one of the cherished legends of the Ta n'Ur that their entire clan is of prehistoric kingly blood, and you have joined her in marriage."

Heavens above, was I doomed by fate, to live my life as a legend old beyond time itself?

"I will confess," Banur admitted, "that when Gakko's villains abducted Lil-rin, the Legend seen to be shattered. For the Alar Danan could not be conceived of as allowing another to take from him his mate. But the promptness and daring of your rescue only adds color to the story."

"It was nothing," I protested quickly. "I had superior weapons—" "Of lightning and thunder," Banur murmured.

Me, Daniel J. Hanley, a legend!

"My strength is naturally greater, since gravity is denser on Earth than here on Mars," I almost shouted.

"As befits the Hero of the Legend," he insisted calmly.

"And besides, Lil-rin fought as well as I did, and actually saved me when I went down under the rush of Uallo and his followers—"

"Which is only to be expected in a warrior princess of the Ta n'Ur-and the espoused of Danan," Banur concluded triumphantly.

It was useless to argue with him, so I took another angle.

"Well, Banur," I said rising, "it is certainly an astounding coincidence. But, to get down to cases. My next step must be to get Lil-rin back to her own people."

"No," Banur told me, also rising and bowing low with arms wide, in the Martian gesture of respect for superiors.

"The Ta n'Ur," he announced, "will be here by morning, fully equipped for a long campaign as the bodyguard of Danan-lih and Lil-rin the Alar-Lur and Alara-Lur of Mars."

"Wha—what are you talking about?" I gasped. "Have you gone insane?"

"If I have, Danan-lih, so has my lord Almun, Alar of Borlan, who has learned of you and your fulfillment of the Legend. He personally instructed me to lay his tribute at your feet and to inform you of the irrevocable decision of all the Alarin, except Gakko and possibly his two satellites, in naming you Alar-Lur, Supreme Lord of the Council. Layani, the present Alar-Lur, is retiring, to continue only as Alar of Hoklan."

"But ... but ... if I protested—" suddenly drained of further strength and expostulation.

"They would not dare do otherwise, in view of the popular devotion to the legend. Besides, the situation is the most opportune that has ever arisen to deal with Gakko. For Gakko, with the support of Mui and Donar, Alarin of Trilu and Yonodlu, has determined to stop at nothing to make himself the Supreme Lord.

"The army of Borlan already is on the march to the Gakalun border. The forces of Hoklan follow. Around the other shore of the Polar Sea, eastern, the Tuski-donin will threaten Yonodlu and Trilu, endeavoring to hold them neutral, but attacking if they are unsuccessful.

"Alar Udaro and his Ilmonin will take to the sea, skirt both sides of the Polar Ice Cap, and attack the Gakalun coast, centering their operations on the city of Gakalu. And you, Danan-lih, will be our Leader."

THE morning brought news by dog-post. There had been desperate fighting at all the passes in the mountains dividing Gakalu and Borlan, but neither side had gained advantage. The Ilmonin had set forth in their fleet.

Layani, ex-Alar-Lur, with his Hoklanin shock troops, was one-third of the way across Borland in his march to reinforce the Borlanin in the mountains. Before night he would arrive with his bodyguard to make personal obeisance to me and Lil-rin.

And the Ta n'Ur had arrived. They greeted us with a great shout and much tossing of spears as Lil-rin and I stepped forth, clad from head to foot in the blue of royalty. Every young man and woman of the clan was there, fully armed, to the number of nearly a thousand.

Lil-rin, taking direct command, spent the day explaining and demonstrating to me their battle tactics, mounted and unmounted. Before Layani and his Hoklanin arrived, I had a pretty good idea of what the Ta n'Ur could do and how to handle them.