RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

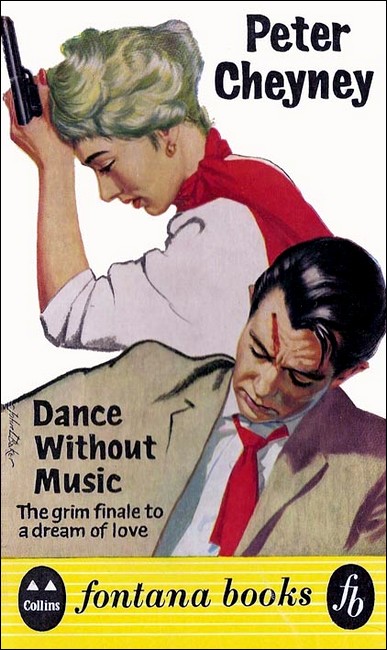

"Dance Without Music," Collins, London, 1947

"Dance Without Music," Dodd, Mead & Co., New York, 1948

"Dance Without Music" is also the title of a short story by Peter Cheney featuring Slim Callaghan. At the time of writing, the date and place of original publication could not be ascertained, but it is conjectured that the story made its first appearance in 1939 in the weekly magazine Illustrated (Odhams Press, London). It was reprinted in the 1941 collection Mister Caution—Mister Callaghan (William Collins, London).

BEING a private detective is a strange sort of business. A business which sometimes attracts odd types. I do not necessarily mean bad types. It has always seemed to me that the primary attraction to the profession is a desire for adventure; to live a life apart from the day-to-day routine of normal affairs—an irregular, sometimes boring, and occasionally exciting life.

Often, experienced and responsible police officers—sometimes of high seniority—become private detectives on retirement from the police and detective forces. Even they—after a lifetime spent in dealing with crime, mayhem and skullduggery in general; in meeting the weird types that abound in the half-world and underworld—still feel the fascination for the game that bring with each "case" the lure of fresh adventure or the matching of wits against a sequence of peculiar events or people.

There are, generally speaking, four types of private investigators; and although these types may occasionally overlap, it is interesting to consider them. They are: The retired police officer who starts his own agency; the Specialist Investigator retained by an Insurance Company for "insurance" investigations; the man who has gone into the game because he likes it and either runs his own office or works as a "staff-man" in an Agency; and lastly—because I think he is the most interesting "type"—the "free-lance" investigator who works for any Agency or organisation that cares to employ him he likes the job and the money is good enough.

Quite obviously, the "free-lance" has to be good at his job. He must be. If he isn't he won't eat. He is dependent on work being put in his way by other organisations, or because of a personal recommendation from a satisfied professional client. He is usually retained in a case because it presents features or difficulties at which he is known to be expert. He must be trustworthy because he is not a "staff-man" who can be sacked if he makes a mistake. In other words, he lives on being known and recommended as a good, trustworthy man who is fitted to work on his own; cautious—yet a man who, in spite of his caution, will, if the job requires it, "take a chance." Because, believe it or not, every private investigator, at some time in his career, has to take a chance. Especially in England where—unlike the U.S.A.—he is not recognised in any way by the official police forces, and where official records and information are not (or not supposed to be!) at his disposal.

The work that comes to the "free-lance" is varied. Often it is an extremely confidential—essentially secret—investigation which the head of an established agency prefers to be handled outside the office for one of a dozen reasons. Sometimes the work is concerned with cases that end in the Divorce Court. These cases are often more interesting than appears on the surface. Sometimes a divorce investigation presents the most thrilling, subtle features. Often the actual evidence—sordid as it may seem—given at the hearing of a divorce case, presents only one very small aspect of a picture that, very often, began with love; went on to indifference, distrust and infidelity; finished with hatred—and worse than hatred.

It must be obvious that the private detective, is subject to many temptations. Sometimes he falls. Private detectives are human like people in other professions. They may be good, bad or indifferent. But if they have failings, it must be remembered that they also have virtues. They serve their purpose; otherwise they would not exist.

And if they seldom add up to the picture of the invariably moral, forthright, brilliant and virtuous private detective presented in the usual "detective" novel; if they are human enough not to possess all—or any—of these qualities, still they are often adequate to "steer" their clients through some of the difficult mazes of life and eventually to write "Closed" on a folder in which are written the notes of some secret story which, if published, might possibly redound to their credit.

This is the story of Leonora Ivory, of Alexis and Esmeralda Ricaud, of John Epiton Pell and a few other people who came into it, said their little piece and walked—or were pushed-out again.

It is also a part of my life because I handled the Ivory business from the start and I have tried to tell the story without any frills.

Cheyney has written it pretty well as I told it to him. He has found it necessary to alter names, switch dates and localities and time angles.

But, fundamentally, the story differs little from the one that I told him after our first (and now historic!) meeting at Trubshaw's place—The Lamb Inn—on the Eastbourne-Hastings road in 1946.

Caryl Wylde O'Hara.

Steynehurst,

Near Wych Cross,

Sussex.

February 1947

THE street looked like a river that led nowhere. Just like that. The lamps were dimly reflected on its flat, wet surface.

The houses and warehouses at the side, the pavements, were in the darkness. You couldn't see them. All you could see was that the flat surface of the curving street with the reflection of the lamps and an occasional shadow made the street look as if it were flowing like a river.

I stopped on the corner to light a cigarette. I'd looked at the goddamned street so often—at so many different times of the night or day—that I knew every inch of it. And I didn't like it. I thought that as streets go it was second-rate and everything in it was like that—including the office. That office was second-rate all right. So was I. I was worse than second-rate. At the moment I was fourpence a gross C.O.D. and please return the empties.

One of these days, I thought, I was going to get out of this dump and go somewhere where there were green fields and cows with no intelligence grazing in them. And sunsets. And no hooch. Where women were women and the men didn't worry about the fact too much.

Somebody—Montaigne or some brain like that—said that adversity is the time for philosophy. Like hell it is. Philosophy being the process of adapting a new frame of mind to an extremely dull set of circumstances. Which sounds to me like sympathising with a gumboil. It doesn't do much good but it doesn't make it any worse. You only think it does.

Here and there down the street were the rear lights on parked cars. Like fireflies on the river. I passed a new Armstrong-Siddeley. It looked sleek and out of place. When I opened the downstairs door the smell of dust came out and hit me. I was used to it but tonight it seemed worse than ever. I began to climb. I went up slowly, making up my mind. Which is something I can usually do very quickly. I could either take Pell's money, close up the office and get out for a little fresh air, or I could stay put and see what happened. I thought that if anything was going to happen it wouldn't happen immediately—or would it? How did I know?

It seemed to me that the matter should be decided with whisky. There was a half-bottle in the office. Which was about the only good thing in the set-up.

I walked along the passage on the second floor. I passed all the bum little offices where odd types fronted at being agents for something or other and often looked harassed to hell in the process. At the end was my own door. And there was a light inside.

That was funny. But perhaps it wasn't. Perhaps Pell had already sent round the pay-roll. It could be. But I doubted it. I'd never known Pell to be in a hurry to pay—not even when the money was so well-earned as this was.

Still... you never knew.

I opened the door and went into the outer office. The door of the inner room was half-open and the light was on, I took a quick sniff at the air and smelt perfume—good perfume.

I pushed open the door and went in. I stopped just inside and had a good look. This, I thought, is the end of a perfect day.

She was seated in the one big leather armchair in front of my desk. She was relaxed and her arms lay along the sides of the chair. She looked at me coolly as if I was some new sort of animal. Not unpleasantly, but with a detached—a rather vague—interest.

I looked at her for quite a while. She wore a dull pink dress with a full length coat of the same colour over it. The pockets and collar of the coat were powder blue velvet. The coat was cut in at the waist and showed off a figure that was very inviting. Her hat was of dull pink felt with a blue ribbon to match the velvet. Underneath, her chestnut brown hair gleamed with bronze tints. Her stockings were sheer and expensive and she wore blue glacé court shoes. Her gloves and bag lay on my desk. She wore two or three gold rings and one very good diamond clip-brooch.

I felt in my pocket for the packet of cigarettes. I took one out and lighted it. I was still looking at her. Her face was long and heart-shaped. She had fine eyes and a straight nose, a mouth with a short upper lip, and one of those complexions that take about four generations of beauty treatment to acquire. And she wasn't worrying a lot about anything.

I said: "Good evening." I went behind my desk; took off my overcoat and hat; hung them on the hat stand behind the chair and sat down. I switched on the desk lamp, got the half-bottle out of the lower drawer, drew the cork and took a long swig. It made me shudder a little. I remembered I hadn't eaten for quite a while. I put the bottle back in the drawer.

She seemed faintly amused. She said: "You are Mr. O'Hara, aren't you?"

I nodded. "When did you arrive?" I asked.

"About ten-thirty. Mr. Pell said he thought you would return after drinking hours. He said he thought you'd be doing a little drinking this evening."

"Did he tell you why?"

She nodded. A small movement of the head. Whenever she made a movement you wanted her to repeat it. She was worth watching—if you know what I mean. "He said you'd spent most of today in the Divorce Court, and that he thought Counsel had been rather unkind to you."

I grinned. "An understatement," I said. "Counsel for the other side tore me in pieces." I shrugged my shoulders. "One of the risks of my profession."

She moved a little. "He wasn't very kind, was he? He said that you were unscrupulous; cheap; a hired raker of dungheaps. He said that it was appalling that evidence such as yours should be necessary or possible; that you must be lost to all sense of decency to have undertaken to give the evidence you did give."

I said: "You must have been reading the evening papers. The fact remains that my evidence clinched the case." She nodded. "It was not suggested that you were an unsuccessful raker of dungheaps," she said slowly. She was nearly smiling.

I got out the bottle and took another swig. "And you've been sitting here waiting to tell me this?" I asked. I was wondering.

She shook her head. "You were working for the Pell Agency, I believe. I went to see Mr. Pell to-day to ask him to handle some business for me. He didn't like it at all. He told me about the case you gave evidence in. He said he'd never handle another case like that after the beating-up you got this afternoon."

I drew on my cigarette. "I like that. I handle the case. I get the beating-up and Pell snivels. Is that all?"

"No," she said. "When I told him what I wanted done he said that he wouldn't have any part in it. He said that after today he was through with anything of that sort. He said they'd employed you and that you'd secured your evidence by the most unethical methods—judged by the lowest standards. He said that in no circumstances would Pell ever employ you again. He said that after to-day he doubted if any Investigation Agency would employ you."

"Very nice of him," I said. I grinned again. "Pell never had an over-developed sense of gratitude."

I decided to finish off the whisky. Then I thought I wouldn't. I was interested.

I sat there, drawing on my cigarette and looking at her. She was quite unperturbed. She seemed not to mind being looked at. She was relaxed—reposeful. She knew her own mind—that one. She was the sort of person who knew what she wanted and went straight for it. She was so goddam certain of herself that she could afford to be cool about it and not worry about other people's reactions. And she was very easy to look at. I went on looking.

After a minute she said: "Well... aren't you going to say anything, Mr. O'Hara?" She picked up her handbag. "And do you mind if I smoke?"

"Go right ahead," I said. I put my hand in my pocket for my lighter, but she beat me to it with a small gold Ronson. She lit the cigarette—one of those fat expensive Egyptian ones, inhaled, and sat looking at the office wall. After a while she repeated; "Well?"

I asked: "Well... what? I'm supposed to react, am I? I'm supposed to listen to that piece you just gave me about Pell not using me any more and doubting if any Investigation Agency—no matter how cheap or near-the-knuckle—would ever use me after to-day's business in Court? Well... I'm not reacting. Maybe I'm supposed to say that the K.G. who led for the respondent was talking through his wig; that I was merely doing my duty; that somebody has to rake over dungheaps in not-so-nice divorce cases?"

She blew a smoke ring. When she did it she pursed up her mouth and that was definitely something to look at. It showed you just how her mouth would look if she was kissing you. I thought that if she ever got as far as Hollywood, and somebody like Pandor Berman ever got a look at that smoke-ring blowing thing, he would sign her up for keeps. Not that her type ever had to go to Hollywood.

I fished out a fresh cigarette.

"Maybe," I went on, "I'm supposed to say that Pell is a louse. Such a louse that he passed the buck to me in this business so that he could keep out of it, collect a lot of dough from a rich client, and still keep his nose clean. Maybe I'm supposed to say all that. Well... I'm not saying it."

She raised her eyebrows and took a quick look at me. She had clear blue eyes that were quiet and unhurried.

She said: "Exactly what are you saying then?" I grinned at her. "What the hell has that to do with you?" I asked.

She laughed. I liked hearing her laugh. It was a low rippling sort of business, and it was an amused laugh. She really meant it.

"Of course, you're perfectly right," she said. "I haven't even explained my presence here. I wanted to hear you talk."

"Well, you're hearing me talk. And I'm not even charging a cover fee. What would you like next? Shall I recite or go into my song and dance act?"

She got up. For a moment I though she was going. Just for a few seconds I began to be a little disappointed. But it was all right. After she'd got up, she turned the chair round so that it was facing me. Then she sat down again and crossed her legs. Her legs and ankles matched the rest of the outfit. Everything was definitely very good.

She stubbed out the cigarette in the ashtray. She said: "Let's imagine——just for the sake of argument—that I have some sort of right to be here; that you don't mind talking to me; that you know who I am; that..."

I laughed. "I'd rather imagine that you were paying me money. I like that better."

"Very well." She gave another of those little laughs. "Imagine that. And go on talking. You finished on the note that you were not saying any of the things that I expected you to say—about Mr. Pell. And about the things he said of you."

"Right," I said. "That was the note. I'm not saying any of the expected things, because if I did they wouldn't be true. I knew all about that case when Pell asked me if I would undertake to get the evidence. I knew about it first of all because of what he told me, and also because I'm a very good investigator, and I had a pretty good idea as to how the thing was going to shape. Getting evidence in defended divorce suits when the parties would pay money to see each other laid out on a morgue slab is never a business for people with sensitive nervous systems. The evidence is never particularly nice, and the methods used to get it are usually extremely unethical, to say the least of it. You understand that?"

She nodded. She said she understood.

"I also guessed that Pell would throw me to the lions afterwards," I continued. "I knew he'd have to. But his people would win their case and why the hell should he worry about me? All Pell could do would be to wash his hands of me and say that the whole thing was just too shocking; that if he'd known what sort of business it was in the first place he would never have touched it with a barge pole—and all the rest of it. I knew all that before I started."

She nodded again. "Then please tell me," she asked, "why you did it?"

"Don't be silly," I said. I got up and came round the desk. I stood away from the side of the desk and looked down at her. From that angle she looked good enough to eat except that she had some sort of aura round her that reminded you of Iceland. "Don't be silly," I repeated. "Why do you think I did it? I knew there was gold in them thar hills. One hundred down; twenty a day for expenses; and a thousand pounds on the successful completion of the suit; that is the decree nisi. Well... they've got their decree nisi and I can use the thousand pounds."

She moved a little. "You think it was worth it?"

I shrugged. "I never think about what's worth what. I'm not like that. I weighed it up and concluded that what was coming to me was worth the thousand pounds."

"And you've received the money?"

"Not yet," I answered. "I'll get that tomorrow."

She said: "I don't think so."

I drew on my cigarette. I asked: "Just what is this?"

"Mr. Pell talked to me," she said. "He was very frank about all this. He wasn't feeling at all pleased about it. I think he talked to me much more freely than is usual because he appeared to want to stop me doing something that I wanted to do; something which he thought would be very foolish. He..."

"Let's take all that for granted," I said. "Why don't I get paid?"

"He seems to think that the loser of the case today—the respondent—isn't at all happy about it." She smiled—a soft little smile. "Not at all happy. You can understand that. It seems that the respondent has been threatening all sorts of things ever since this afternoon. One of the things he says is that half of your evidence, supported as it seemed by independent testimony, was false; and the independent testimony secured by bribery—from you. Mr. Pell says he's going to wait to see what happens; that there may be an intervention in the case, and that he's not going to pay you until he knows. That isn't so good for you, is it?"

"No," I agreed. "That isn't so good. It was nice of you to come here to tell me about it. I like that. It's very friendly."

There was a silence—one of those silences that you could cut with a knife. I went back and sat down in the chair.

I asked: "Where do we go from there?"

She opened her bag; took out another cigarette. She lighted it. She said: "You're not awfully curious, are you?" When she said that she looked at me and smiled gently.

I said: "I gave up being curious years ago. People are only curious when something in life surprises them. Nothing surprises me."

She said: "No?" She raised her eyebrows.

I went on: "When you've been a private investigator for as long as I have, take it from me that when something surprises you, you fly a blue flag and fire a twenty-one gun salute."

She didn't say anything.

"I'm not even surprised," I said—I was grinning at her—"that Pell, who is supposed to be one of the cleverest private investigators in this country, should sit down and discuss somebody else's business with you at length, in order to stop you doing something which you wanted to do. And I've never known Pell to be so confiding. Something must have happened to him. The only thing that would make Pell confiding or altruistic would be money."

She said: "You're quite right. I was prepared to pay him quite a lot of money for advice."

"Nice work," I said. "Having got the money he gave you some sweet and negative advice. When in doubt, don't do it. That sounds like Pell. I hope you got your money's worth."

"So I take it," I continued, "that ever since then you've been having quite a struggle with yourself. You go to Pell, pay him a large fee and ask him what you're to do. You open your heart to him."

I stubbed out the cigarette. I was sick of smoking cigarettes.

"And a woman like you doesn't do a thing like that unless she's in a spot. So I take it you're in a spot. Pell warned you off whatever you wanted to do. But you tried to talk him into it. I imagine that he still wasn't playing, but he had a nice fat fee on the desk in front of him and he thought he'd give you some value for your money, so he told you about the last case he'd handled. He told you about me. He told you what a son of a bitch I was; what Counsel had said about me and people like me generally. Pell held this up to you as a grim warning." I grinned at her.

She smiled again. She settled herself back comfortably in the armchair. She fascinated me. Every time she moved I watched her. Every movement, no matter how small, was imbued with an unstudied, almost perfect, grace. I thought as a woman she could cause plenty of trouble. Maybe she had.

She said: "You're a very discerning person, Mr. O'Hara. Your instinct seems sound."

"Instinct my eye," I said. "The facts are sticking out like Brighton Pier. People like you don't hang about in a dingy office like this at this time of night, waiting for the proprietor to return from a spot of drinking, just for the pleasure of telling him that he is a discerning person. Why don't you cut out the frills and get it off your chest? I've an idea that whatever it is, it's very tough."

She asked: "Why do you think that?"

"It has to be," I said, "You wouldn't have been giving me all this Pell stuff—what he said and what he didn't say—unless you were preparing me for something even worse than this afternoon's experiences."

She got up. She got up quite suddenly and quickly. She stood on the other side of the desk, the cigarette held between her slim white fingers, looking at me seriously.

She said: "I expect you're very disappointed about the Pell money."

"It's very nice of you to be concerned," I told her. "I take it you're referring to the thousand pounds that Pell told you he wasn't going to pay me?"

She said slowly: "Yes... that's what I meant."

I said: "Listen... do I look like the sort of man who's not going to be paid? Pell made a deal with me. I've carried out my part of the bargain. I'm going to see he carries out his."

She asked quickly: "You think you can make him pay?"

"I haven't thought about it at all yet," I answered, "but I'll back myself to find some means of making Pell cough up that money. And now, if you don't mind, I'm rather tired of discussing Pell. In any event, it has nothing to do with you."

"It has quite a lot to do with me," she answered. She hesitated; then: "You see, I shall be glad to give you the thousand pounds that Mr. Pell isn't going to pay. And you can take it from me he won't. I know when a man means what he says. He's scared. He has the idea that if there's an intervention about the divorce case he might be affected. After all he was the person who hired you. He thinks if he gives you the thousand pounds, the fee is large enough for somebody to suggest that there may have been bribery."

I shrugged my shoulders. "So you're going to make it up to me? That's very nice of you. Why?"

She said: "Of course there are conditions."

I laughed at her. I said: "Sit down. Sit down and relax. I like to look at you sitting down."

She sat down.

"So there are going to be conditions?" I went on. "Extraordinary! You're not just going to give me a thousand pounds because you like my personality."

She said softly: "You're being fearfully whimsical, aren't you, Mr. O'Hara? Of course I'm not going to give you the thousand pounds for nothing. But I'm prepared to pay a thousand pounds because I don't want you to be annoyed with Mr. Pell, and also because I'm rather grateful to him in a way. If I hadn't gone to his office this afternoon I should never even have heard about you."

"And you're glad you did?" I queried.

She nodded. She smiled again and showed me a perfect set of teeth.

She said: "I'm very glad I did. What I've heard about you tells me that you're the person I'm looking for."

I started a new cigarette. "Let me hear the worst."

She paused for a moment; then: "Is there anybody you're particularly fond of, Mr. O'Hara—really fond of?"

I shook my head. I said: "I can't remember anybody. There are one or two people I've liked. I don't know anybody I'd go to bat for in a really big way." I smiled at her. "I think about people superficially," I said. "It's easier."

She moved in her chair. "You sound to me like a man who's been disappointed about something—possibly a woman."

"What man hasn't?" I asked.

"Precisely—but you particularly," she said. "You sound rather cynical."

I didn't say anything.

She went on: "I asked if you'd been very fond of someone because if you had been you'd understand the way I feel."

"And how do you feel?" I asked.

She shrugged her shoulders. "I'm very unhappy—very miserable. Not about myself personally... I've nothing to be unhappy or miserable about. But I'm terribly unhappy about a friend—a woman friend. She's younger than I am. She was a very sweet girl."

I said: "And what do I do about that?"

She was silent for a few moments. She seemed to be trying to make up her mind about something. I had time to look at her and concentrate on the business. I came to the conclusion that she was an extraordinary type. You just didn't see people like her in those go-ahead days. She was unique. She had beauty and style and breeding and practically everything that goes with those things, Also she was clever. She had brains. She had to have brains to have pulled a fast one on Pell. And I was certain that she had pulled a fast one on Pell. I wasn't so pleased about that.

Eventually she said: "It's rather a long story, but it's better that you hear it from the start. Then you'll know how to handle it. You'll be able to tell me if my idea is right. Would you like to listen?"

I nodded. I said: "Go ahead."

She began to talk in a quiet voice. She looked at her hands, folded in her lap, whilst she was talking. I had the impression that it annoyed her a little to have to talk.

She said: "When the war began I thought I was in love with an officer in an Infantry Regiment. He was a little younger than I was and I know now—now that I've had lots of time to think about it—that I didn't really love him. I suppose I liked him a lot and felt a little maternal about him. Can you understand that, Mr. O'Hara?"

"Why not?" I said. "That's easy enough."

She went on: "He wanted to marry me before he went to Burma, but I wouldn't do this. I said that when he came back would be time enough. He was sorry about that but he agreed. He was an awfully nice person."

She stopped talking and I could see her long fingers clasping and unclasping. She was feeling nervous about something.

"He was captured by the Japanese and he had a terrible time in a prison camp," she said slowly. "Eventually he died. I expect you can imagine that life had been pretty grim for him before the end."

"I can imagine that," I said.

"When I heard about his death I was terribly upset. I felt that in any event I ought to have married him. I was angry with myself and unhappy about everything. I thought that the best I could do would be to travel and not think about things. I was rather ill and my doctor thought it might help if I went away. I went to America and I took my friend Esmeralda with me."

I asked: "Does she come into this?"

She nodded.

"What is Esmeralda like?" I asked.

"She's younger—five years younger than I am." she said. "She used to take a rather superficial view of life. She was carefree and happy and inclined to be romantic. I was very fond of her. I still am."

I told her to go on.

"After I'd been in America for a few months I met a man—Alexis Ricaud. I'd just begun to get over my previous unhappiness, but I was still restless and unsettled. And Ricaud seemed charming and friendly and strong. He seemed to be very much in love with me and to be rather a nice person. I married him in America and found out that I'd made a mistake a little too late."

"What sort of mistake?" I asked her.

"I found out about Ricaud," she said. "I need not go into details, but a few months after we were married I discovered, by an add accident that he wasn't at all a nice person. I discovered that he lived mainly by blackmailing women; that his charming exterior concealed an extremely nasty and sadistic nature; that his record was an unpleasant one; that he had married me merely for my money."

"And you did something about that?" I asked.

She nodded. "I had straight talk with him. I told him that I knew about him. I told him that I intended to divorce him immediately."

"And he didn't like that?" I asked.

"He didn't like it, but he couldn't do anything about it. I told him that if he tried to put any obstacle in the way of the divorce I should go to the police..."

"His record was as bad as that?" I queried.

She said: "Yes... it was very bad. He agreed to the divorce and admitted that everything I had said was true. Knowing him I ought to have suspected that his prompt acquiescence in my wishes meant that some scheme was already in his mind. But I didn't suspect. I told him that I was leaving the United States immediately and returning to England; that I had instructed a New York attorney to bring suit for divorce against him; that I should take steps to free myself from him as soon as possible.

"I returned to England. Esmeralda returned with me, I had no suspicion at this time that Ricaud had already been making love to her; that she was fascinated by him; that she believed everything he said."

"Has Esmeralda any money?" I asked.

She nodded, "She was quite well off." She shrugged her shoulders. "But not now."

"Go on with the story," I said.

"In due course my divorce came through. Then, almost immediately, I learned that Ricaud had come to England; that he was engaged to be married to Esmeralda. I was horrified. I wrote to her and told her what I knew. I entreated her not to go through with the marriage until she had talked to me."

"But she didn't believe you," I said. "They never do."

"You're quite right... she didn't believe me. On the contrary she wrote and told me that I had concocted the story about Ricaud because I was sorry that I had divorced him; that I was jealous of her. She refused to see me. Soon after, she married Ricaud."

"And now she knows that you were telling the truth," I said.

She nodded her head. "She knows now," she said softly. "Now that it's too late. Mr. O'Hara, she's in an awful state. Ricaud has had most of her money. She has very little left. She discovered quite soon after her marriage to him that what I had said about him was only too true. But she was absolutely and completely in his power. Once or twice she wrote to me and told me that she was going to divorce him. Then, for some unknown reason, she would change her mind. She left him, came to me and told me stories of his conduct and cruelty, and then returned to him. I realised that he had some strong hold over her. Something that was greater than her own will-power, her self-respect, every good thing about her—something so beastly that one can't imagine it...."

I said: "Dope?"

"Yes," she said slowly. "He started her on drugs, and now I believe she's a complete addict. She makes half-hearted attempts to get away from him, but always fails. She won't let any of her relations or friends help her. She's absolutely and completely in his power."

She stopped talking. There was quiet in the office. I could hear the clock on the mantelpiece ticking. It was a cheap clock with a hell of a tick. In the silence it sounded like an infernal machine.

"Is that all?" I asked.

She said miserably: "Isn't it enough?"

I asked: "Enough for what?"

She put her hands on the edge of the desk. I could see that her fingers were trembling.

She said quickly: "Isn't it enough, Mr. O'Hara? Isn't it enough for you to do something about?"

I stubbed out my cigarette. "What do I do about it?" I asked her.

She said: "Listen to me, Mr. O'Hara. I'm afraid. I'm awfully afraid for Esmeralda. I think she's reached the end of her tether; that she isn't quite responsible for what she's doing. Something must be done and done quickly."

"What's in your mind?" I asked. I was almost interested.

"I can't prove that she's getting drugs from Ricaud," she said. "But I'm certain of it. So is her doctor. And Ricaud is afraid of the law. I'm certain it would help if you went to see him. If you told him that you were acting for Esmeralda's relations; that you had discovered that she was getting drugs from him; that unless he agreed to leave the country immediately and to leave her entirely alone so that she could be properly looked after and cured, you would go to the police. But I want you to do that immediately, Mr. O'Hara. At once. There isn't any time to be lost."

I lit a cigarette. I said: "It doesn't seem worth a thousand pounds to me. It's too easy."

"It might not be so easy," she said. "He's clever and unscrupulous. And he has some peculiar friends. If you threatened him there might be some after-effects."

I grinned at her. "I see. You mean that I might have to look after myself for a bit?"

"Yes," she said. "That's what I meant."

I asked: "By the way, who are you?"

She smiled. "You're the oddest man, Mr. O'Hara. I think your attitude is quite enchanting. You arrive here and give yourself a drink and sit down and very kindly listen to what I have to say; then suddenly you decide that you'd like to know who I am."

"Is that odd?" I asked her. "It really hasn't mattered until now."

She looked at me. Her eyelashes were long black and very well-mascaraed. So well done that you could hardly see the make-up.

"Of course you're perfectly right," she said. "It hasn't mattered until now. And now when it does matter you want to know." She smiled again, suddenly. "You become curious only when it's really necessary. You must be very bored with life to be like that."

"All right," I said. "Let's take it that I'm very bored with life. And now the name...?"

"My name is Ivory," she said quietly. "Mrs. Leonora Ivory. That was my maiden name. I re-took it when I received my divorce from Ricaud."

"It's a nice name," I said. I wrote it down on a pad. "Can I have the address?"

She said: "I'm staying at the Culloden Hotel at the moment."

I wrote that down too. I asked: "Have you got the thousand pounds?"

She smiled again. "Yes. I knew you'd help." She opened her handbag. She brought out a fat packet of notes and laid it on the desk.

I smiled back at her. "It's a pretty sight," I said. "A packet of new notes like that. If I were an artist that would be my idea of still life."

She said: "Perhaps it's a pity that you aren't an artist."

I said: "I shall have to try to be artistic about Mr. Ricaud, shan't I?" I put the notes in the desk drawer. "Where does he live?"'

"He has a house not far from Maidenhead—a house called 'Crossways.' It's on the outskirts of the place. He's usually to be found there."

I asked her: "Does he live there alone?"

She said: "I think so. He's not there very much in the day, I believe, but usually at night. Some women come in and look after the place in the day. I think he's usually alone at night." She hesitated. "Unless he has someone with him...."

"A woman?" I queried.

"Usually a woman," she answered.

"Right," I said. "Thank you very much, Mrs. Ivory."

I got up; threw away the cigarette.

She asked: "What are you going to do?"

I smiled back at her. "I'm not going to do anything."

She rose quickly. She stood looking at me across the desk. Her eyes were suddenly very cold. She said: "Do you mean that?"

"Why not?" I asked. "What I lose on the swings I make up on the roundabouts. I've got the thousand pounds. The money that you say Pell isn't going to pay me."

She said coldly: "You think that you are safe in doing this? You think you can afford to behave like this?"

"I'm damned certain I can," I said. "Do you think anybody is going to believe you if you tell them that, after seeing Pell this evening; after hearing what he had to say about me; after knowing what Counsel said about me in Court this afternoon; do you mean to tell me that anybody is going to believe that you put a thousand pounds in that nice handbag of yours; came round, sat alone in my office and waited for me to come back? Do you think anybody is going to believe any part of this story?"

She said: "Mr. O'Hara, the notes I gave you were five-pound notes. The bank will have the numbers."

"No, Mrs. Ivory." I grinned at her. "Banks used to keep the numbers of five-pound notes, but they don't today. They haven't for the last two years."

There was silence; then: "So it seems there isn't anything more to be said." She sounded very unhappy.

I came round the desk. I said: "That's how it seems to me."

I was going to move the door to open it. When I got near her, I stopped. She was looking at me and her eyes were filled with tears. She looked like a dog that's been beaten. I don't know what perfume she was wearing, but it was unobtrusively devastating. I stopped and stood looking at her. I liked the view.

She said in a low voice: "I was rather scared when I came here tonight to wait for you—scared of what you'd be like; what you'd say. I'm not used to this sort of thing. I grant you I came here because I thought you weren't a very scrupulous person. I wanted someone who wasn't very scrupulous, because the thing I was going to ask wasn't a particularly nice thing. When I'd talked to you for a little while, in spite of myself, I got a vague impression that you might not be quite so black as you were painted."

I said: "And now you know you were wrong?"

"I'm still wondering if I'm wrong," she answered. "I can't quite believe that you'd do a thing like this."

"I'm doing it," I said. "You can't believe it because you don't like believing it."

She did an odd thing. She took a step towards me and put her hand on my arm. The whiteness of her long, slim fingers seemed strange against the dark background of my sleeve. She said in a low voice: "Mr. O'Hara... please... oh please..."

I said: "No soap...! Thanks for a pleasant evening. I'm sorry you'll have to go down the stairs, but we haven't a lift."

She flushed. Then she hung her head. She moved to the desk and picked up her handbag and gloves. Then she walked out of the office. The tears in her eyes weren't imitation. They were very good.

I heard her high heels tapping down the corridor.

I sat down in the revolving chair, opened the desk drawer and took another swig at the whisky bottle. By now it was only a third full. Then I walked out of the office and down to the end of the corridor. I opened the window and looked out. Below me lay the street, the lamps still gleaming on its wet surface.

After a minute she came out of the downstairs doors. She walked along to the Armstrong-Siddeley; unlocked it; got inside. She made a "U" turn and drove off.

I went back to the office and sat down. I began to think about Mrs. Ivory. She was a person you could spend a lot of time thinking about.

But at that moment I wasn't very fond of her. At the back of my head was the idea that she had been trying to frame me somehow; trying to push me into something... .

Not that her story hadn't sounded O.K. It was plausible enough, but it was the Pell thing that I didn't like.

I knew Pell. He was old in sin and tricky as hell. But he wouldn't take me unless he was very badly tempted. He knew goddam well that I knew the solicitors in the case; that I knew that they knew that I'd pulled the chestnuts out of the fire for their client and not Pell. Pell had that thousand pounds for me, and if Mrs. Ivory hadn't turned up he would have paid it. He always paid promptly when he had to. And this time he had to and knew it. Until she came along.

She'd gone to him and told him some story, and Pell had told her that I'd probably handle the business for her if I was interested, and if I was sufficiently hard up. He would have told her that I was like that. He would have told her that I never handled cases unless I was interested—for some reason or other—and unless I wanted money. My guess was that he'd told her that I didn't want money just now because he owed me a thousand pounds.

And then she'd got to work on Pell. She'd made it worth while for Pell to say he wouldn't pay me because he thought that there might be an intervention. This way she thought she was making a certainty of me. She knew I'd have to take the case because I needed the money. It suited Pell because he thought that with luck he'd be able to hang on to the thousand for a bit, and that I shouldn't worry him because I'd have her money and think maybe that more would be coming. She'd talked Pell into it, paid him well, and he'd supplied her with the story, my address and a description of what he considered to be my somewhat peculiar characteristics.

Mrs. Ivory, I thought, had had what was coming to her. But I didn't like it. Not a lot. She was too beautiful to try to pull fast ones on O'Hara.

That's what I thought. I thought it and then I finished the whisky.

THE chime of the church clock, striking the half-hour, sounded as if it was cracked. Maybe it was cracked. When it had finished striking I listened to the clock on the mantel-piece ticking.

I decided that I wouldn't think about Mrs. Ivory any more. I took her money out of the drawer and put it into my inside breast pocket. Then I put on my hat, switched off the lights, closed up the office and went away. Out in the long dark corridor I could see the moonlight flooding through the window at the far end. It was like walking out of night into broad daylight.

My footsteps echoed down the wooden, carpetless stairs. I closed the outer door, locked it, and walked down the street.

It took me ten minutes brisk walking to get to Joe Melander's place—The Desert Room. Joe was waiting at the bottom of the long flight of stone steps that led down to his Bottle Party. He looked like he always looked—plump, well-fed, and freshly shaved, with just a spot too much talc powder and a hair-dressing that was over-scented.

He said: "Good-evening, Mr. O'Hara. Glad to see you. Always glad to see you." He grinned at me. "I see Mr. Lamberley, K.C., was a little harsh about you this afternoon, These barristers..." Joe shrugged his shoulders. "It's very hard on you private eyes," he went on. "Come and have a little drink with me out of my bottle?"

I left my hat and coat with the girl in the entrance lobby and went in with him. We sat down at a table in the far corner. The waiter—who looked as if he'd got sleeping sickness—brought a bottle of whisky, a siphon and some glasses.

I said: "A private detective is entitled to be shot at in a divorce case. If the suit's defended. The other side always try to discount his evidence. When it's a bad case like this one was, a Private dick is lucky to get out with a whole skin."

"Yeah," said Joe. He poured out two big slugs of whisky. He smiled a little.

"They must have paid you a lot of money. That man was very very unkind to you." He squirted in the soda water.

"You're unreasonable," I said. "Why should a Divorce Court pleader be kind to a detective? It wouldn't be human."

Joe said: "You've certainly got a sense of humour."

I looked round the big room. I thought that the idea of calling it The Desert Room was subtle. But then Joe Melander was like that. The walls were painted to look like an oasis in the desert, with palms, camels and things. Looking at the clientele you could be certain that the only interest it took in camels was a professional one. Anything that could go for eight days without any sort of drink would really mean something to these boys and girls.

They were an extremely tatty crowd. Especially the women. The men had plenty of money acquired by all sorts of strange methods that come after a war. The women were thinking up ways and means of getting some of it. You could see them doing it. I think some of the girls were having a hard time. But then anything would seem hard after the Americans had gone home.

"I thought you didn't handle divorce cases, Mr. O'Hara?" Joe refilled the glasses; then he grinned; shrugged his shoulders. "Sorry about that," he said. "Me—I'm always too curious."

"It's all right, Joe." I said. "I don't usually handle that sort of thing. But things aren't too good these days and the money was very attractive."

I began to feel restless. It was a sudden sort of feeling. I didn't know why.

Joe said: "You look tired to me. You look like you need a holiday."

I nodded. "It's an idea. If anybody comes here asking where I am, you can say I've gone on a holiday."

"You expecting somebody to ask?" His expression was what they call old-fashioned.

"Maybe," I said. "You never know." I got up. "Can I use your telephone?"

He nodded. "If anybody wants to know where you are, you've gone on a vacation. And you didn't leave an address."

"That's right," I said.

He gave me the key of his office and I walked across the dance floor, up the little flight of stairs; let myself in to the office; switched on the light. I closed the door and put the catch on the lock.

I looked up the number of the Culloden Hotel and dialled it. I asked the night clerk to put me through to Mrs. Ivory.

He said there wasn't any Mrs. Ivory staying in the hotel; that there was no pending reservation in that name; that they didn't know anything about Mrs. Ivory.

That surprised me a little. But not much.

I relaxed in Joe's big office chair. I began to think about the picture I'd seen of the hotel in Torquay; with the palms and the long vista of the sea and the sunshine. An attractive picture. I thought that Torquay would suit me very well for a few weeks. The idea of sitting in a deck-chair, listening to music and watching the sea, seemed good and—at the moment—desirable.

I thought that Torquay was the place.

I wondered what it would be like to sit in a deck-chair and listen to music, and watch the sea, and talk to Mrs. Ivory. That, I thought, would be something.

As ideas go it was good and it went.

I picked up the telephone and called Pell's flat. While I was waiting for the buzz I looked at my wrist-watch. It was nearly twelve o'clock. Pell would be getting his beauty sleep.

He came on the line. He sounded a little short.

I said: "Pell? This is O'Hara. I'm coming round to see you."

He yawned. "I'm in bed. I'm tired and I've got an office to see people in. What's the matter with tomorrow morning?"

"Nothing as far as I know," I told him. "Except that I'm going to see you tonight—in about ten minutes."

He asked: "Are you going to try to make a lot of trouble?"

"How do I know?" I said. "I'm not a mind reader."

I hung up. I went out of the office, down the stairs and back to Joe's table. I gave him the key.

I said: "Good-night, Joe. Thanks for the phone call."

He put the key in his pocket. "So you fixed it, Mr. O'Hara. Are you off tonight?"

I nodded. "I'm going to Torquay. It ought to be a nice night for driving. I saw a picture once of an hotel there. I liked it."

"Torquay is a nice place," he said. "I hope you have a good time."

It took me twelve minutes to walk round to Pell's place. The apartment block was in darkness except for a light in the front hallway. I went up in the lift, switched on the passage lights, walked along to the flat and rang the bell. A man in a black alpaca coat opened the door. He was a short, thin character, with a twitch in one eye. He looked pallid, careworn and fed-up.

I said: "I'm Mr. O'Hara. Mr. Pell is expecting me."

He stood to one side and, after he had shut the door, I followed him down the long passage. The flat was airy and well-furnished. Some of the pieces were very good.

He opened a door at the end and I went in. Pell was sitting at a desk, facing me, on the other side of the room. He was wearing a finely-checked black and white dressing-gown and a scarf. He was smoking a green cigar and there was a whisky glass on the desk.

Pell was plump in the face and bald. He had a peculiar skin that looked grey in some lights. His mouth went down at the corners. His lips were thin but looked better when he smiled. He had fat white hands and wore a valuable ruby ring, which he said some Indian Princess had given him, on one fat little finger. Pell was successful and clever and tricky and grasping.

I looked at the other man in the room. This was a very big one. He was sitting in an armchair on the right of Pell's desk. The armchair was big but seemed too small for him. He seemed about six feet two or three in height, and as wide as a house. He had a face like a rock and an underslung lower lip. His clothes were too smart. He was smoking a cigar and looked very happy about something. I didn't like him much.

Pell smiled at me. I closed the door behind me and walked over to the desk.

He said: "Hallo, O'Hara. What's the trouble?"

"There isn't any," I said. I got out a cigarette and lighted it. "I want to talk to you. I thought it was important. And it's private." I looked at the man in the chair.

Pell waved his hand. "Don't worry about Lennet. He's an old friend."

"I'm not worrying about him. I'm just saying I don't think he's necessary. I want to talk to you."

Pell shrugged his shoulders. "Look, O'Hara. The way things are I thought it better if Lennet was here. That's fairly reasonable, isn't it? He's not doing any harm and maybe it's a good thing to have him here. For everybody's sake."

"No," I said. "He has to go."

The man in the chair laughed. It sounded like the tide coming in. Out of the corner of my eye I could see him measuring me; assessing my six feet of thinness and lack of muscle.

"Don't be silly, O'Hara," said Pell. He meant his voice to be soothing.

I said to the man in the chair: "Go away, Stupid. Go and get some sleep. Your type needs a lot of sleep."

He put the cigar on the edge of the desk. He pushed himself up with hands that were like meat plates. When he was up, he looked very intimidating.

He came over to me. He said: "What did you say, Clever?"

I let him get close. As his hands went up I flashed a shin-clip with my left foot; side-stepped and pushed with his weight as he went back to avoid the foot-blow. At the second that he was off-balance I put two quick fingertip blows on the neck muscle; then, as he turned away from the pain of the neck blows, I gave him the side-of-the-hand blow downwards on the kidney. He gasped; hesitated; tried to stand away. I went with him and let him have two fast simple judo blows with a hard hand—a direct neck and muscle blow on the Adam's apple.

He made a noise like a wheezy bagpipe. He went backwards into the chair.

I stood watching him. I said to Pell, over my shoulder: "That's judo. It's nice, isn't it?"

Pell drank some whisky. He nodded. He seemed impressed.

"Get up, Fat," I said to the man. "I didn't mean to hurt you. Get up, shake hands and go home. You're safer in bed."

He got up. He held his hand out and I took it. When I saw his left arm move I put the neck lock on. The neck lock done from the handclasp.

He gasped. It didn't sound at all nice. He stood there, his head and neck held rigid, staring straight in front of him.

I said to Pell: "It's pretty, isn't it? He's paralysed. He can't move. When I take this lock off he'll still be suffering from shock for a minute or two, and during that time he's mine."

I took off the lock and let go his hand. He stood quite still, moving his neck and head warily. I gave him a backhand smack across the face to help him a little. His lip began to bleed. Some colour began to come back into his face.

"Get your cigar and get out of here," I said. "Be quick, because I'm getting tired of you."

He looked at Pell uncomfortably. Pell nodded. The man picked up the cigar with fingers that were a little shaky. He went out. I heard the front door shut.

"That's very nice stuff," said Pell amiably. "Where'd you get that, O'Hara?"

I told him.

"You've been around," he said. He got up; went to the sideboard; mixed a glass of whisky and soda; brought it back to me. I sat down in the chair. He went to his seat behind the desk. He relit his cigar; drew on it with pleasure. He exhaled the tobacco smoke slowly. He seemed to be enjoying himself.

He grinned at me. "You're a tough egg, O'Hara. What's troubling you?"

"Nothing," I said. "Nothing much."

I lighted a fresh cigarette. "Tonight," I went on, "when I went back to my office, some crazy woman was there. A Mrs. Ivory. A very striking piece of femininity. Maybe you know her?"

He nodded. "So she went round to your place after all. What did she want?"

"I don't know," I answered. "I didn't ask her. I didn't get so far. She bored me. She told me that she'd been to see you and that you'd given her a long piece about not doing something she wanted to do. You warned her off whatever it was she wanted to do. She told me that you held me up as an example of what happened to people who did things they shouldn't. That you quoted Counsel's attack on me this afternoon in Court as a further example. She told me that you said you expected an intervention in the divorce case; that you weren't going to pay me until you knew there wasn't going to be an intervention."

Pell said: "She must be nuts."

"That's what I thought," I said. "I told you she was crazy. If she'd had any sense, she'd have known that the judge wouldn't have granted the decree nisi unless he believed my evidence, no matter what Counsel for the other side said. Any child of two ought to know that Counsel always goes bald-headed for the detective who supplies the evidence in a defended action for divorce, especially when the respondent has brought a cross-suit—as this one did. Any child ought to know that."

Pell chewed on his cigar. "Women are very funny," he said. "Obviously she didn't know what she was talking about. I didn't tell her anything like that."

"I'm prepared to believe that," I said. "By the way, what did you tell her?"

He stubbed out the cigar butt. He finished the glass of whisky. Then he said: "She came here this afternoon with a long spiel about something or other. I wasn't particularly interested. I told her that the Pell Agency never handled a case unless the client was personally recommended by someone we know; that I was sorry but I couldn't handle her business. You see?"

I nodded.

He went on: "She went on talking and I thought she might make a scene. She was good and worked up about something or other. I wanted to get rid of her. So I told her about you."

"What did you tell her?" I asked.

"I told her that you'd just handled a job for me that required a lot of tact, ingenuity and guts. I said you'd done a great job and that even if Counsel had attacked you in Court the judge had believed your evidence and granted the decree nisi to our client. I told her that if she liked to go round and see you and tell you about it, there was a chance that you might handle it. I told her that she couldn't be in better hands."

"That was nice of you, Pell," I said. "Maybe I ought to have talked to her and heard what she had to say."

He shrugged his shoulders. "You never know—there might have been something in it." He got out another cigar. "Is that all you wanted?"

"No," I said. "I want a thousand pounds."

He raised his eyebrows. "You're in a hell of a hurry, O'Hara. Come in to the office tomorrow and we'll fix it."

"No." I told him, "the money was due to me when the decree nisi was granted. That was this afternoon. I'll have it now."

Pell said: "Supposing I haven't got it?"

"You'll have to get it," I said. "I want it now."

He grinned at me. "You like a joke, don't you? It's all right. I've got the money here for you. I thought you'd be coming round for it. And you earned it all right. My people are tickled silly about today. The lawyers were on to me this afternoon. They said you'd done a terrific job."

He opened a drawer in the desk. He took out a quarto envelope and passed it over to me. I opened it and counted the notes inside. It was all there. I put the envelope in my pocket. I got up.

Pell said: "You can send me a receipt tomorrow." He yawned. "Perhaps it would have been a good thing if you'd listened to what the Ivory woman had to say," he went on. "Maybe there would have been something in it for you."

I picked up my hat. I said: "Why did you have to have that bruiser around here when I came, Pell?"

He laughed. "Oh, him.... He's an old friend of mine—Lennet. He thinks he's good. He thought you were taking a rise out of him. I was very glad when you put him in his place. When I said that it would be a good thing to have him here I was just pulling your leg."

"Of course," I said. We stood smiling at each other. Then I said good-night and went out.

Outside, the streets were cool. I began to walk slowly towards Mack's place near Leicester Square.

I liked the walk. I began to think about the picture of that lunch in Torquay and the sea and the sunshine. I liked thinking about these things.

After a bit I thought about Pell. Pell was very clever and very tricky. He knew his way about. I wondered why the hell he had pulled all that stuff on me about the woman Mrs. Ivory. I wondered if he thought I believed any of it.

But he'd been goddam clever about Mrs. Ivory. Now I begun to get an idea about the way he'd played it. She'd paid him good money—probably a lot——to promise that he wasn't going to give me the thousand. She'd come round to me believing that; thinking that I'd work for her because I was broke.

But Pell was ready to pay me if I got tough about it. He thought I was going to be tough so he paid. That way he saved the amount she'd paid him that afternoon. Everyone, it seemed, was fairly happy—except Mrs. Ivory.

Mrs. Ivory paid everyone and didn't get anything much—except a brush-off. Which is what inevitably happens to beautiful ladies who try to be very clever.

And Pell believed the stuff I had told him about not knowing what she came to see me about. He knew nothing about my having had the thousand from her. If he had, he would never have parted with his money.

That meant she hadn't seen him since she left my office. She hadn't attempted to see him. She'd gone off somewhere. But not to the Culloden Hotel. I wondered why she'd given me that address. Maybe she'd meant to go there if I'd agreed to do what she wanted. Maybe if I'd said yes she'd have gone to the Culloden and made a reservation. She knew the place was half-empty anyhow and that getting a room there would be easy.

But why hadn't she made the reservation first?

There might be an answer to that one. Supposing I'd really done what she wanted me to do; supposing I'd said yes and taken the thousand and gone off and started in? Would she have gone to the Culloden then P?

I thought not. Definitely not. It was a certainty that nobody had seen her come to my office. She'd carefully left the car right down the street. If I'd taken her money and agreed to try to fix Ricaud, she was going off and she was going to say that she'd never seen me in her life. If I tried to find her at the Culloden I should draw a blank. She wouldn't be there and they wouldn't know anything about her.

I thought Mrs. Ivory was nearly good. She had brains.

MACK WAS sitting in the little glass office in the corner of the all-night garage. He had a thin face and big luminous brown eyes and sandy hair. I'd known him for a long time. He liked running an all-night garage because he didn't like people a lot. I think he'd had a lot of trouble in his life and in a place like that you didn't have to talk much. People who came in just wanted petrol or oil or something. They paid and went away.

He was reading The Evening News. He grinned when he saw me. He said: "Hallo, Mr. O'Hara. I see you've been in the wars again."

I looked at the newspaper. "Oh... that...! Yes, if you like to call that a war." I gave him a cigarette. I asked him if he had a car for sale.

He asked: "Is it for you?"

I nodded.

He said: "I've got the very thing for you, Mr. O'Hara. I'll guarantee it. The owner brought it in two days ago. He's going abroad. It's a 16 Rover—a sports coupé—only done nine thousand miles. I've been over it and it's in perfect condition."

I asked: "Can I drive it away?"

He nodded. "It's licensed and insured till the end of the year. I've got the log book. If you like to pay for it, all it needs is some petrol and oil. It costs seven hundred and fifty pounds, and it's a bargain."

I took the packet with the Pell money inside it out of my pocket and counted out the notes.

I said: "Give me a receipt, Mack... and fill the car up."

He asked: "Are you going far?"

"To Torquay," I said. "I haven't had a holiday for a long time."

He said: "That ought to be good." He went to the back of the garage and drove the car up to the pump. It looked in good condition. And the tyres were good. He began to fill the tank.

I asked: "How do you go to Devonshire, Mack?"

He said: "That's easy. From here to Chiswick High Street and the Great West Road, branch off for Staines and Virginia Water, and then it's near straight as damn. You'll be all right. They've got 'A.A.' signs up now. There's only one thing you want to remember... when you curve off from the Great West Road you come to a fork. The left hand side goes to Staines. That's what you want. Don't take the right hand fork; otherwise you'll end up in Berkshire."

I said: "All right."

I watched him fill the car with oil.

He asked: "Shall I send the receipt round to the office, Mr. O'Hara?"

I said: "No... I won't be there for a bit. Send it to the Malinson Hotel, and put on the envelope 'To await arrival.' I expect I'll be going there when I come back."

He said "O.K."

I got into the car; started the engine; drove off. The car sounded good to me. I liked having it. Altogether it seemed as if it had been a pretty good evening—except for Mrs. Ivory. I thought that the situation about Mrs. Ivory wasn't really very satisfactory. But that was just one of those things. Life is like that. Mainly because I had nothing else to think about, and you've got to think about something when you're driving a car at nearly one o'clock in the morning—I began to think about some of the things she'd said.

I found myself getting a little angry about her. I found myself thinking about Mrs. Ivory and trying to remember what her perfume was like. I found myself wondering about Esmeralda, and trying to work out what might—or might not—have happened if I'd taken the job and gone down and seen Alexis Ricaud and played it off the cuff and watched results.

It might have been interesting....

Except for the phoney address she'd given me. And perhaps there were some strings to the job. Perhaps if I'd done what she wanted I should have walked into something. Maybe she'd intended that...

You never knew with women as beautiful as Mrs. Ivory.

It began to rain again. The clouds came over the sky, but there were good headlights on the car and I thought it would take me about seven or eight hours to get down to Torquay. I looked forward to arriving just in time for breakfast. I turned off the Great West Road. In front of me was the roundabout. The road to the left led to Staines; that on the right—the Bath road—to Slough and Maidenhead. I pulled the car in on the left-hand side by the roundabout and lit a cigarette. I sat there with the rain pattering on the roof of the car, smoking and thinking about Torquay.

Of course the picture I'd seen was probably an exaggeration. All those advertisement pictures of hotels and sea fronts are always a little too good. But even if the place was something like it, it was still going to be all right. I'd always heard that Devonshire was a great county.

I started up the car and let in the gear slowly. The car began to move forward. Just for an instant I had one of those flashes—you know what I mean—a mental picture that for no reason at all comes right in front of your eyes, a reminiscent thing of something that's happened and implanted itself on your subconscious brain. It was a picture of Mrs. Ivory going out of my office. As the car moved forward I thought about her. Just in those fleeting seconds I was able to think quite a lot. I thought she was a phoney; that she didn't like telling the truth; that maybe she was a damned good actress. The whole thing possibly had been an act. But she was a very intriguing sort of woman. I wondered what the hell she was at.

Then I stopped the car.

I stopped it because I knew something. I knew I was kidding myself. I knew goddam well that if I took that left fork to Staines, and if I went down to Torquay and stayed at that hotel, and sat on the front in the sunshine and watched the sea and listened to seagulls, and took an interest in boats and things that I hadn't seen for a long time; I knew that if I did that, all the time I'd be curious. I'd be wondering about Mrs. Ivory...

And that gave me a jolt. It gave me a hell of a jolt because I realised that I was curious. I was curious about something, and I hadn't been curious about anything for years.

I knew the Torquay thing was going to be no soap. If I went to Torquay I was going to have something at the back of my brain for the rest of my life that I wouldn't be able to forget. I threw the cigarette stub out of the window and lighted another one. I started up the car again. I took the right fork—the fork to Slough and Maidenhead.

I STOPPED the car on the dirt road twenty yards behind the high iron gates that led into the back driveway of the house. The gates were unlocked. I pushed one side open and went through. I walked along the wide gravel path. To the left and right of me were thick shrubberies. Trees, heavy with rain, were dotted about. The path wound through a labyrinth of rhododendron bushes.

The rain had stopped as suddenly as it had started. The moon had come out from behind the clouds. I could see the house—a big Georgian affair—standing on a rise a good hundred yards away.

I looked about me. Ten or twelve yards ahead, a path ran off from the driveway on which I was standing; disappeared amongst the trees. I began to walk along it. It wound through the shrubbery. I thought maybe it would lead to one of the back entrances to the place—the servants' or tradesmen's doors.

The path led nowhere. It finished abruptly, turning off into a little clearing where the grass was thick, uncut and glistening with rain. I leaned up against a tree. I was looking at something that was very funny. A young woman in an evening frock was going through the motions of slow fox-trot underneath the trees on the other side of the clearing. It looked as if she found it difficult to dance on the slippery grass with high heels, but she seemed to like it.

She had a fur coat over one arm and an evening handbag—a large flat affair—clasped under the other. I thought she was either mad or cockeyed—maybe both. I walked across the clearing. Now the moon was right out of the clouds. It was quite bright. When she saw me, she stopped dancing. She stood, her shoulders hanging limply, the fur coat trailing on the grass, staring at me with a bemused expression. She looked to me like a girl of about twenty-five or twenty-six years of age. She might have been a little younger or a little older. She had good blonde hair which had been well-dressed before the rain got at it.

She wore a parma violet dinner frock that had been cut by somebody who knew his business, and a string of pearls. There were long sleeves to the frock and they clung closely to her arms with the weight of the rain. She was a pretty girl, with big surprised looking eyes.

She said in an odd voice: "Hallo! Who are you? And where are you going—that is if you know where you're going?" She leaned against the tree and regarded me dully.

I said: "I'm not going anywhere." I grinned at her. "You like al fresco dancing on a wet evening?"

She laughed. "Yes..." she said shrilly. "I like it. It's nice. To dance without music. We used to do that. We used to meet here in the moonlight and dance without any music and we liked it. It was fun."

"Why was it fun?" I asked her. "And what are you trying to do about it now? Are you trying to recapture the memory? That's usually due to sentiment—or misery—or jealousy. Or the whole lot. Which is it?"

She said: "You've got your nerve, Mr. Clever-dick. Telling me about what I'm trying to recapture and why and how and what. You've got your nerve, Mr. Whoever-you-are."

Her voice was thick and she enunciated with difficulty. She was tight. Her head sank down and then she pulled it up with a jerk. I should think she was finding it difficult to keep awake.

"All right," I said. "You were saying that you like to dance without music..."

She interrupted impatiently. "Yes... that's what life's like—a dance without music! A lot of people dancing about on a ballroom floor—and they don't even know that the band's gone to bed."

I said: "Maybe you're right." I came closer to her. I could see the initials in gold on the flat parma violet evening handbag—"E.R."

"My name's O'Hara," I said.

She looked at me for a little while; then she jerked her head up again. "Good evening, Mr. O'Hara. I'm Esmeralda."

"Esmeralda Ricaud?" I asked.

She said: "Yes... how did you know?"

I pointed to the initials on her handbag.

She said stupidly: "I think you're very clever." She smiled at me. Her eyes were vacant.

I said: "Look, I came here on the chance of seeing Mr. Ricaud. I have had a look at the front of the house and the whole place seems to be in darkness. I tried the frontdoor bell and nothing happened so I drove round to the back."

She said: "Quite. Everybody here uses the back gate. It's more convenient." She relapsed into silence and her head drooped. I thought she was going to fall over. I think she would have if it hadn't been for the tree. She said suddenly: "Look, why don't you and I go and have a little drink, Mr. O'Hara? Why don't you and I have a party?"

I said: "I think that's a good idea. Let's go and have a party. Where?"

She nodded towards the house. "We'll go in. I've got a key." She began to sing to herself... "I've got an invitation to a ball..."

I said: "All right. My car's on the road. What shall I do with it?"

She said: "Drive it through the gates and leave it amongst the trees. It'll be safe there. Nobody'll see it."

I asked: "Have you come down from somewhere?"

"Oh, yes... from London," she answered. "I was at a party. I got bored with the party so I thought I'd come down here."

I said: "Well, I'll go and get the car. Will you wait here till I come back?"

She nodded. "Yes, I'll wait here."

I went down the path, back to the car; drove it through the gates, off the main gravel path, in amongst some trees. I switched off the headlights and locked it. Then I went back and closed the gates. When I got back to the clearing she was still there leaning against the tree. The fur coat and the handbag were on the ground where she'd dropped them. I picked them up. I put the handbag under my left arm and draped the coat over it. When I squeezed my arm against the soft handbag I could feel the outline of the gun in it. I put my other arm round her.

I said: "Let's walk."

We began to walk. She got better every minute. Her body was well-shaped and supple but thin. She was wearing some sweet, rather heavy, perfume which I didn't like. It took us quite a while to get to the house. We reached a door at the back and after a search in her handbag she managed to find a key. We went in.

She said to me: "There's a switch in this passage somewhere on the right. You find it."

I left her leaning up against the wall while I found the switch. When I'd put the light on we walked down a long passage-way that led to what I took to be the front hall—quite a big, well-furnished affair. We went down another passage at right angles, through a door, into a room. On the way I put on lights when she told me.

It was a comfortable room—big, high-ceilinged, with good furniture. There were one or two good oil-paintings on the walls. There was a big old-fashioned sideboard against the wall with a lot of bottles on it. She moved unsteadily from the door, got as far as one of the big chairs by the side of an electric imitation fire, and flopped into the chair.

She said: "Welcome to 'Crossways,' Mr...."

I said: "The name's O'Hara."

She said: "Of course, Mr. O'Hara. What's your first name?"

I told her my first name was Caryl. She smiled vaguely. She said: "Christmas Carol... I think that's a nice name. I like it, Are you an Irishman?"

"Mostly," I said.

She said: "I like Irishmen. D'you think you might get us some drinks? And I want a cigarette."

I gave her a cigarette and lit it. I said: "Don't you think you ought to get out of that frock? You're wet through."

She looked at her thin soaked evening shoes. She said: "It doesn't matter. It couldn't matter less. I don't mind being wet."

I said: "All right."

She looked at the sideboard; then: "For me... some whisky... whisky with ginger ale. You have whatever you like... Caryl."

I went to the sideboard. I mixed myself a stiff whisky and soda. I put my forefinger in the top of the whisky bottle; ran it round the edge of a clean glass; then poured some ginger ale into the glass. That way she could smell the whisky and think she was drinking it. I carried the glass back to her. Then I knelt down and switched on the electric fire.

I said: "Well, this is very nice. What shall we talk about?"

She drank some of the ginger ale. She said: "This tastes very strange to me."

I said: "Yes? It's a very mild one. Shall I change it?"

She shook her head. "It doesn't matter. Nothing matters. Nothing matters at all... at all... at all..."

I pulled up the other big armchair so that it was opposite hers. I sat down and lit a cigarette. I said: "Tell me something, Esmeralda... why do you have to carry a gun in your bag?"

She looked at me suspiciously. "How d'you know I've got a gun?"

"I felt it when I carried the bag. Do you have to have it?"

She nodded. "But definitely!" she said. "I have to have a gun. And I have to have it all the time, because if I have it all the time, one of these fine days or nights I'm going to use it."

I said: "That's fine. You mean you can't make up your mind to get around to using it on any specific occasion. You just like to have it with you in case you feel you'd like to use it. In other words... time, place opportunity—and you've got the gun with you. Is that it?"

She said: "That's very nearly right, Caryl. I can see that you do quite a lot of thinking."

I asked: "How do you feel about me, Esmeralda. Do you like me?"

She looked at me for a long time. Then she smiled—suddenly. "Yes. I haven't known you for an awful long while, but I certainly don't dislike you. Why?"

I said: "If you don't dislike me, tell me why you have to carry a gun around always. Tell me who it is you want to kill."

She smiled again. It was a peculiar and not very pleasant smile. Looking at her now I could see that she'd been quite beautiful at one time, but her face was ravaged. Her features were good, her nose was straight, her mouth well-shaped, her teeth regular and white. But there was so much unhappiness and misery about her eyes that the beauty had become obscured.

She looked at me for a long time. The way she was sitting her face was in the shadow, and I couldn't see her expression. She seemed to be considering something. Or maybe she was tired and cockeyed. I wasn't quite certain.

She began suddenly: "I was at a party... and what a stupid party. But then I think most parties are stupid... don't you, Caryl?" Her voice trailed away into nothingness.

"Parties can be all right," I said. "Sometimes... or not... as the case may be. You seem to have done pretty well at yours. Weren't you happy?"

She laughed. The laughter was odd. It had a peculiar lilt in it. Something not particularly good to listen to.