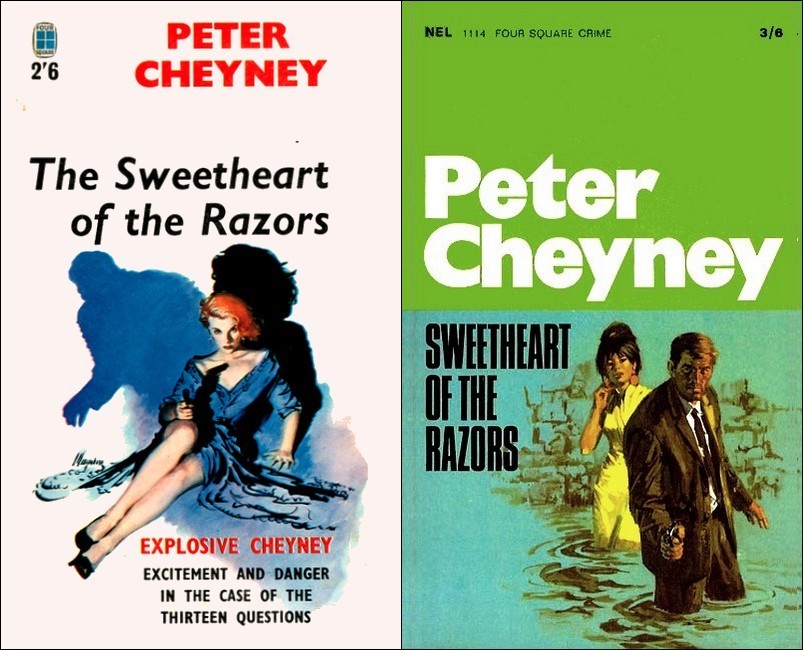

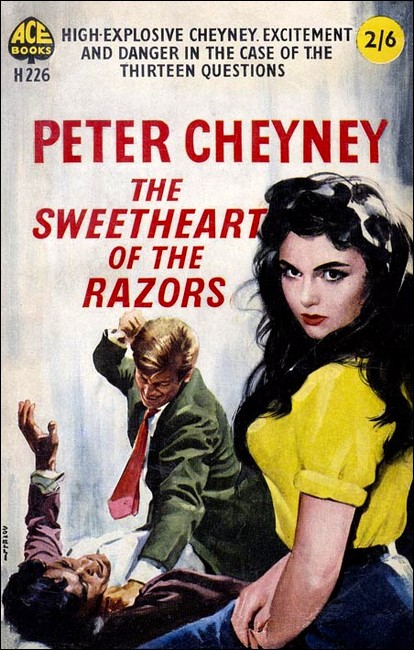

RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

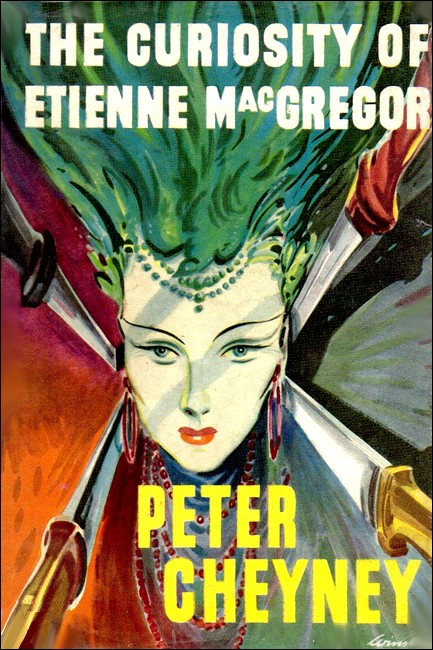

"The Curiosity of Etienne MacGregor," Hennel Locke, London, 1947

In this episodic novel Etienne MacGregor, a young and cheerful man about town, is informed by Rudder, Foal and Rudder, a firm of solicitors, that his uncle has died, leaving him £25,000, providing he answers thirteen questions. If he fails to answer any one of the questions within seven days, the money is to go to the son of his late uncle's partner—a Chinaman named Suan Chi Leaf. MacGregor soon realises that Suan Chi Leaf and his mother, Mrs. Lotus Leaf, will stop at nothing to prevent him answering the questions, and that his uncle has deliberately matched him against the cunning of the Chinese.

Thanks and credit for making this work available to RGL go to the Australian bibliophile Terry Walker, who collected and pre-processed them for publication in book form. The stories are arranged chronologically in the order of their publication in the Australian press.

— Roy Glashan, March 2017.

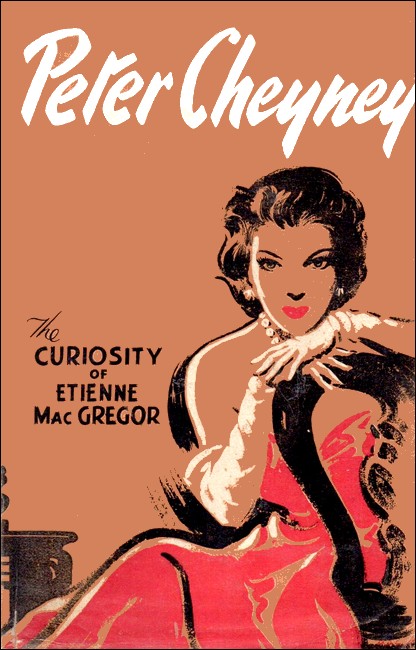

"The Curiosity of Etienne MacGregor," Corgi Paperback (undated)

IN spite of the mist, which, approaching from the direction of the palace, was slowly enveloping The Green Park in a greeny-grey cloud, and in spite of the drizzling rain, the face of the Mr. Etienne MacGregor bore that cherubic and philosophic expression which had so often impressed people with the mistaken idea that he had nothing to worry about. He sat on a seat immediately facing the band-stand. The park was deserted, except for one or two pedestrians, who, under the shelter of umbrellas and rain-coats, hurried to catch their last trains. The fact that the seat was rapidly assuming an uncomfortable dampness was increasingly borne upon Mr. MacGregor as each minute passed. But he sat there with a faint smile upon his round countenance, looking at the band-stand as if concentration upon that structure would in some mysterious manner solve his difficulty.

Things were not well with Mr. MacGregor. There was not the slightest doubt about that. If one had been able to see beneath his tightly-buttoned rain coat one would have been aware of the fact that his clothes were well cut and well kept, but an investigation of his well-polished shoes would have informed the close observer that the sole of the right shoe was becoming less on speaking terms with the upper at every moment.

Not that he minded being hard up. He had been hard up for most of his 28 years, but there had always been methods of procuring money at difficult moments. At least there had been one method—his uncle. But the letter which reposed in his breast pocket had even nullified that source of income.

He drew it out from his pocket and read it for the tenth time, as if one more perusal might help in the solution of the difficulty. The letter read:—

142 Lincoln's Inn Fields, W.C.

Dear Mr. MacGregor,—

With reference to your application for a further loan from your uncle, we regret to inform you that this is impossible, owing to the regrettable fact that he died last Tuesday.

We have pleasure in informing you that you are his sole heir, and under his will you inherit his fortune of about £25,000, but under certain conditions. These conditions are that you supply us with the answers to thirteen questions.

Those questions will be given to you singly, and the answer must be brought by you to this office within one week from the time you receive the question.

In the event of your not answering a question within the time stated, the whole of your inheritance passes to the son of your uncle's partner—Mr. Suan Chi Leaf.

In the meantime, our instructions are to render you no financial assistance whatsoever, as your uncle was of the opinion that this method of leaving you his money would give you some chance of satisfying what he describes as your "insatiable curiosity," and that if you succeed in answering the thirteen questions and remain alive he thought that you would have more than earned the money.

The first question to which we must request your answer within seven days is:—

Who is Mrs. Lotus Leaf?

We are, dear sir,

Your obedient servants,

RUDDER, FOAL and RUDDER, Solicitors.

MacGregor replaced the letter in his pocket and

ruminated upon the hardness of the world, and more especially

upon his old curmudgeon of an uncle. How could he answer

questions of this description? The bit at the end, too, about

remaining alive did not sound too hopeful. He realised that

there had been but little love lost between himself and his

uncle, and probably the old boy had taken more than usual care

to ensure that the questions should be practically unanswerable.

MacGregor was so engrossed with the proposition that he failed

to observe the odd-looking individual who had seated himself

upon the end of the seat, and who was regarding MacGregor with

more than usual interest.

Etienne got up from the damp seat and commenced to walk in the direction of Piccadilly. So did the odd-looking stranger. As they approached the park gates the seedy individual came close to MacGregor and touched his arm.

"Excuse me, sir," he said in a wheezy voice, "but I think that you are in a little difficulty—a difficulty in which my assistance might be useful. My name is Gubbs."

Etienne regarded the stranger for a moment, reflecting that his appearance certainly was not prepossessing.

"Well, Mr. Gubbs," he said, after the scrutiny, "and may I ask how you intend to help me?"

"Well, Mr. MacGregor," said the man, wheezing more than ever. "You want to find Mrs. Lotus Leaf, don't you? And I can tell you just where you will find her."

"Now, look here," said MacGregor, stopping suddenly; "look here, friend Gubbs. How do you know that I want to find Mrs. Lotus Leaf?"

The man smiled rather sadly. "It's my business—knowing things, sir," he said. "You see I used to be one of your uncle's head clerks in China, until I was dismissed. I know the conditions under which you will, or will not, inherit the money."

MacGregor thought hard for a moment. When he looked up his smile was more cherubic than ever.

"What do you expect to get out of this, Mr. Gubbs," he asked.

Gubbs looked pained. "I don't want anything, sir," he said, "nothing at all. I thought I'd like to do something for my old master's heir, that's all."

"I see," said MacGregor, quietly. "Just doing it out of kindness, er, friend Gubbs? Well, that being so, just where is Mrs. Lotus Leaf?"

Gubbs smiled. "You'll find her at the Three Leaves Club; in Slater-street, Limehouse, Mr. MacGregor. But if you want to see her you'd better go down right away. She's leaving for Paris tomorrow, but if you go down there at once you'll find her all right. I'll put you on the right bus. I'm walking down Piccadilly myself."

In vain did Mr. MacGregor point out to the persistent Gubbs that he knew the Limehouse bus routes quite well, for that worthy insisted on accompanying the curious Etienne, and it was only when he was safely ensconced on the front seat of a Limehouse bus that Mr. Gubbs, with a flourish of his dilapidated hat, faded away.

It was characteristic of MacGregor that immediately Mr. Gubbs and disappeared he got off the bus with alacrity, and walked quickly to his rooms in Mortimer-street.

Mrs. Hands, the housekeeper, who opened the door, gazed at him in astonishment.

"I never expected to see you, Mr. MacGregor," she said. "At least, not so soon after getting your note!"

MacGregor smiled. "So you got a note from me, did you, Mrs. Hands?" he said. "Brought, I suppose, about ten minutes ago by a seedy-looking gentleman by the name of Gubbs. Can I see it?"

Mrs. Hands produced the note and handed it to MacGregor. It was signed with a very fair imitation of his own signature, and stated that he had been forced to leave suddenly for Paris; that he might not be back for some time, and requesting Mrs. Hands to forward his clothes to the cloak-room at the Gare St. Lazare, Paris. MacGregor folded the note and placed it in his pocket.

For some moments after Mrs. Hands returned to her domain in the basement he stood motionless in the hall, immersed in thought. It was only when the housekeeper's fourteen-year-old son, Tommy, ascending the basement stairs, sneezed violently that MacGregor came out of his reverie.

"Hallo, Tommy!" said MacGregor. "Your cold doesn't seem to have improved."

"It ain't the cold I mind, Mr. MacGregor," said Tommy. "It's the stuff she gives me for it. It's awful."

His face registered disgust.

MacGregor looked at the boy for a moment. Then his face broke into an amused grin. "Listen, Tommy, my lad," said he. "I rather think that we are going to have an adventure together. Incidentally, we are going to make use of that cold of yours. In some ways I think it constitutes an extraordinary improvement on your speaking voice. We will repair to the nearest teashop, and over a dish of cream buns discuss a blood-curdling plot. Are you game?"

"I'm game," said Tommy darkly. "There ain't been any excitement round here since the boy next door got run over last June."

It was quite dark when the pair sallied out and made for the nearest Lyons. Here, over a huge dish of cream cakes which brought joy to the heart of Tommy Hands, MacGregor unfolded his plot, and fifteen minutes later he hurried off to catch the Limehouse bus, leaving his accomplice to finish the cream buns and to reflect on the wonderful adventure which had come his way at last.

IT was half-past ten when Etienne found himself in

Slater-street, Limehouse, looking left and right for the

entrance to the Three Leaves Club. He found it eventually,

situated in a dirty alley which led off the main street. The

place seemed deserted and dismal, and it was only when he had

pushed open the battered door and descended a flight of stone

steps that he was able to hear the strains of the indifferent

jazz band which was one of the "features" of The Three Leaves

Club.

At the bottom of the stairs was a dingy office, and as he approached a bullet head protruded and asked him his business.

"My name is MacGregor," said Etienne amicably, "and I wish to see Mrs. Lotus Leaf."

"You just wait a minute," replied the villainous-looking doorkeeper, "an' I'll see if she's in."

Mrs. Lotus Leaf was in, and two minutes afterwards Etienne found himself following the doorman along a stone passage which ran alongside the dance hall. A glance into the main club room assured Etienne that the Three Leaves Club was no ordinary health resort. Full-blooded "blue" niggers rubbed shoulders with Lascars and Chinamen, and exchanged greetings with the white scum of Limehouse.

At the end of the passage was a door, and after knocking upon this Etienne's guide indicated that he might enter. MacGregor pushed open the door, stepped inside, and stood transfixed.

The room was in absolute contradiction to the rest of the place. The furniture was antique and valuable, and the carpet on which he stood was of the finest quality, but it was the woman who sat at the desk facing the door, and who rose as he entered, who was responsible for Etienne's lack of breath.

She was Chinese—and beautiful. Her skin, unlike the usual Asiatic complexion, was pale, and her hair, dressed in European fashion, and piled high on her head, gave her added height. She bowed to Etienne and indicated a vacant chair which faced the desk. A young man, also Chinese, and dressed, in the height of fashion, appeared from the end of the room and stood by her side.

"I am delighted to meet you, Mr. MacGregor," she said softly. "May I present my son, Mr. Suan Chi Leaf."

Mr. Suan Chi Leaf bowed. Round the corners of his mouth appeared the ghost of a cynical smile. MacGregor noticed it, and his own smile became more cherubic. "I am honored to meet you and your son, Mrs. Lotus Leaf—by the way, isn't that a pretty name—" said MacGregor. "Incidentally, I ought to explain to you that my uncle having died and left me his money, providing that I can answer certain questions, I am compelled to seek your assistance, the first question being, 'Who is Mrs. Lotus Leaf?' I shouldn't have known where to start except for the kindness of a certain Mr. Gubbs."

"Exactly," murmured the woman. "I arranged that 'kindness' on Mr. Gubbs's part. Your uncle had a peculiar sense of humor, Mr. MacGregor, which both my son and myself appreciate. As you are aware, in the event of your not answering the questions within the time stated, the money goes to my son, and I think your uncle's rather cynical sense of humor was responsible for setting you to match your wits against us. Unfortunate—for you—that sense of humor, I am afraid."

"Really," murmured Etienne. "May I ask why?"

She smiled. "Certainly," she said. "Because, Mr. MacGregor in an hour's time you will be dead! You must realise that from our point of view you are better out of the way. You will not leave this place alive! A note from you has already been delivered to your housekeeper, who thinks that you have left for Paris. You will leave for Paris. For my son will take your body across tonight in our motor launch. Possibly in two or three weeks' time the body of Mr. Etienne MacGregor will be found floating somewhere on the Seine, and there will be nothing in the way of my son's inheritance."

She looked at him with a cool smile.

MacGregor yawned—politely—behind his hand.

"You are very beautiful, Mrs. Lotus Leaf," he said; "but, really, I don't think you are nice to know. Or your jolly old son either! But I'm afraid that this awfully clever idea of yours isn't coming off. You see, I'm very curious, and I wanted to know why dear old Gubbs was so awfully keen on actually seeing me on to that Limehouse bus. That's why I got off and went home! I thought that as he knew so much about me he'd probably know my address, too. I read the note he left, and then I thought of a bright idea. I thought that you might like to write a note for me to take to my uncle's lawyers telling them that I know all about Mrs. Lotus Leaf, and before I came down here I arranged with K Division police station to ring up here at ten past eleven and ask for me, and unless I'm back at the police station by eleven-thirty I'm afraid they might come along and kick up a fuss. So perhaps you'll write that letter. Incidentally, if you've got a few ten pound notes about the place they'd be awfully useful at the moment!"

The eyes of Mrs. Lotus Leaf narrowed. She was about to speak when the telephone beside her rang. She answered the call, and handed the instrument to Etienne without a word.

"Hallo, inspector," he said. "Thanks for phoning. I'll be with you in twenty minutes. I'm just staying on for a bit to collect a letter and some cash from my dear old friend Mrs. Lotus Leaf—such a sweet woman! I hope your cold is better, inspector—you sound quite hoarse! One day when you've time you must let me introduce you to Mrs. Lotus Leaf and her son. He's a great fellow—a motor launch enthusiast, I believe. Yes, I very nearly went across to France with him tonight, but I thought it was a bit too cold! Goodbye, inspector; goodbye!"

ONE hour later Mr. Etienne MacGregor expounded the ethics of

arithmetic to Tommy Hands.

"Tommy," said he, "your voice as the inspector was excellent, thanks to that cold of yours. It sounded most manful. All of which goes to prove that my curiosity plus your cold and some brains equals one question answered and fifty pounds for me and unlimited cream buns for a month for you!"

TO the casual onlooker it would have appeared that Mr. Etienne MacGregor was engrossed in a study of the scenery out of the railway carriage window. Really, he was interested in nothing of the sort; his mind being engaged at the moment with the contents of the second letter which he had that morning received from Messrs. Rudder, Foal and Rudder, his late uncle's lawyers, which congratulated him upon finding the answer to the first question, and requested politely but firmly an answer to the second within seven days; this second question being:—

"Where was the end of the river that ran sideways?"

Apparently, the lawyers wished to give him some slight clue, for they stated that his late uncle had suggested that he might find the air at Norfolk beneficial when endeavouring to solve this problem.

MacGregor's usual charming smile became more cherubic than ever as he regarded the only other occupant of the railway carriage—an elderly gentleman who might have been a well-to-do farmer, judging by his clothes and general appearance, who had—Etienne had noticed—walked up and down the length of the train twice before deciding to enter this particular carriage.

MacGregor, whose round face and juvenile brow hid an extremely keen brain, had already decided that the appearance of this elderly gentleman was possibly not quite so accidental is it appeared, and, following his usual plan, he proceeded to open the call before his travelling companion could put any of his own ideas into execution. Etienne turned to the old gentleman with his most charming smile.

"Excuse me, sir," he said pleasantly, "but I wonder if you know Norfolk well!"

The elderly gentleman smiled. "Know it well? I should think I did," he said. "Seeing that I was born and bred there."

"Ah," murmured Etienne. "Then I wonder if you have ever heard, of a river that ran sideways?"

The old gentleman looked astonished. "A river that ran sideways," he repeated. "Strange.... very strange. Funnily enough, I have heard of such a river. I can quite well remember hearing it mentioned. At the beginning of last year I was staying at an inn at Gomphill, on the broads. One evening, when I was sitting in the bar listening to the talk of the watermen, I heard a great deal of laughter and chaff about a certain man. This man's name was Twist Anderson, and it appeared that he was the local drunkard, and when in his cups would produce some wonderful story about having seen a river running sideways instead of along its usual course. This story seemed to be a sort of village joke."

"Quite," said MacGregor. "By the way, sir, what was the name of the inn?"

"The Sepoy Inn," replied the old gentleman. "A very old property, I believe. It used to be a country house belonging to a retired merchant named MacGregor. A very pleasant spot indeed."

MacGregor was silent. So the Sepoy Inn had been his uncle's country house! He had known that once on a time his uncle had possessed a house in Norfolk. Was it coincidence, thought Etienne, that this old gentleman—a chance travelling acquaintance—should know so much about the place, and had heard of the river that ran sideways, or was the hand of Mrs. Lotus Leaf behind all this?

At the next station the old gentleman got out, as MacGregor thought he would. He had done what he intended to do. His information was the first move in the game!

Etienne left the train at Gomphill, and found the Sepoy Inn without difficulty. It was a charming old place. On one side of it a well-kept lawn ran down to the river's edge, and on the other was a tennis court. He pulled an arm-chair to the window, and sat thinking deeply.

It was apparent to MacGregor that the old gentleman in the train was no chance traveller. He had selected the carriage after seeing that MacGregor occupied it.

Etienne realised that Suan Chi Leaf and his mother were taking little trouble to cover their tracks. And why should they? They knew perfectly well that he had to solve the questions before he could claim the money, and therefore they were quite prepared to help him along—so long as their help brought him into the set of circumstances in which they could deal with him. He had to be got out of the way—and they would stick at nothing! It seemed to him, therefore, that there was nothing for it but to watch for the next step on the part of Suan Chi Leaf and his mother.

It was evidently their idea that MacGregor should stay at the Sepoy Inn. Well here he was.

Suddenly the actual question flashed into MacGregor's mind—what was at the end of the river that ran sideways? Did Suan Chi Leaf know? Supposing he did not. What was more likely than the fact they would endeavour to help MacGregor to solve the question in order that any advantage should accrue to them? For half an hour Etienne sat by the window, his brain busy with impossible schemes, then a humorous smile appeared on his face, and, lighting a cigarette, he strolled downstairs in search of the waterman—Twist Anderson.

He had little difficulty in finding that worthy. Everyone in Gomphill knew "Twist," and MacGregor was directed to a little cottage which stood directly on the river's edge, about a quarter of a mile from the inn. MacGregor knocked at the door. When it was opened he knew instinctively that the man facing him was Twist Anderson. No man could have been more aptly named. His face was twisted into a perpetual grin, and his arms and legs, which showed great strength, were twisted, too.

"Mr. Anderson," said MacGregor cheerily, "I've come to have a little talk with you about the river that runs sideways!"

Twist Anderson said nothing for a minute, but looked at the ground, and when he looked up his smile seemed more twisted than ever.

"You'd better come inside, sir," he said, and held open the cottage door. MacGregor followed him into the cottage—a very ordinary waterman's cottage, with one exception; on the end of the mantelpiece was a brand new telephone, which Etienne's quick eyes immediately noticed. He took the chair which Anderson placed for him, whilst the waterman sat astride a chair immediately facing him.

"Might I ask, sir," said Anderson, "what you mean by the river that runs sideways?" His grin seemed wider than ever.

Etienne lit a cigarette. "Look here, Mr. Anderson," he said. "I'm a very curious person, and I heard at the Sepoy Inn that several people had laughed at you because you've said that you have seen a river about here that runs sideways. Speaking personally, I'm rather interested—I want to have a look at that river, and if you can help me to do so I'll see that you don't lose anything by it."

Anderson looked at the floor. It appeared to be a habit with him. Then he got up from his chair, and crossing the room to a dilapidated locker produced a map, which he spread out on the table. "Here's the river that runs past this cottage," he said, pointing to it with his finger. "Here is a backwater, about a hundred yards away, and here is a stream—a fairly wide one, which crosses the river near Sanner's-bridge. That's the river that runs sideways. I've seen it doing it," continued Anderson. "I was down there fishing one night, and suddenly my boat was swept over to the bank. I sat there amazed—I wasn't drunk either, and, believe me or not, the river was running from bank to bank instead of along its course. Everybody said I was drunk, and when I thought it over next day I almost, thought it myself! But I wasn't. I've seen it happen a dozen times since then, and always at the same time—2.30 in the morning."

MacGregor was silent for a few minutes, during which time he studied the map closely.

"Well, Mr. Anderson," he said eventually, "I shall be much obliged if you would take me to see this river running sideways. Is that all right? Good. Let's say tomorrow night. I'll meet you at 2 o'clock."

A few minutes afterwards Etienne took his departure. Twist Anderson stood at his cottage door and watched him as he strolled away.

BACK in his room at the Sepoy Inn, Etienne grinned hugely. He

felt very curious, and mainly he wanted to know why Twist

Anderson had so suddenly felt the need of a telephone, for it

was obviously brand new.

When darkness came he undressed, donned a bathing suit and over it some old flannels. Then he quietly made his way across the deserted tennis courts, and, hidden amongst the thick trees, kept close watch on Anderson's cottage.

He had not long to wait. At 10 o'clock a figure appeared and hurried to the back door of the cottage. As it passed through a patch of moonlight the face was plainly shown to MacGregor. It was Suan Chi Leaf!

MacGregor guessed that he had arrived in response to Anderson's telephone message. Keeping well in the shadows, MacGregor hurried down the river bank until he found Sanner's-bridge. He remembered the spots on the map shown him by Twist Anderson, and he examined the banks of the river with the utmost care. At last he thought he had found what he sought, and throwing off his clothes, he dived into the river. He was an excellent underwater swimmer, and it was nearly two minutes before he appeared on the surface. A few quick strokes brought him to the bank, where he dressed hurriedly and set off at a run for the inn.

Half an hour afterwards, after a rub down, he made his way back to the river bank. Then he produced from his pocket a long, coiled length of manila rope. One end of this he fastened carefully to a tree, and paid out the rope until he was able to hang the coil, secured with a piece of silk thread just under the surface of the river beside the bank, at a spot which he calculated carefully. After which, in great good humor, he betook himself to bed.

THE moon cast an uncertain light on the smooth surface of the

river as MacGregor, with Twist Anderson punting, floated quietly

past Sanner's-bridge. Suddenly Anderson drove the punt into the

bank, and caught hold of the overhanging branch of a tree.

"Here's the spot, Mr. MacGregor," he said. "It's 2.25 now. It might happen at any moment!"

MacGregor kept his eyes on the surface of the river and waited. Suddenly, without warning, the river swirled, and then flung itself sideways against the bank. At the same moment Anderson, with a wicked grin, gripping the tree branch, drew himself out of the punt, and simultaneously the punt shot into the swirling waters. It was obvious to MacGregor that the punt must overturn. But he had been prepared for this. Taking a purchase with his feet on the rocking punt, he dived for the spot where the coil of rope was hidden. He sighed with relief as his fingers closed over it, and the silk thread which bound the coil breaking as he tugged, he played out the rope as the swirling waters sucked him down. It seemed an eternity to Etienne as he was flung along by the current.

Then, as suddenly as before, the waters became quiet, and, arching his back, he came to the surface and filled his lungs with air. He was in complete darkness, and he could feel that only a few feet of the rope remained in his hands. After a moment a dim light appeared, and he was able to see dimly about him. He found himself in a square cavern, which he knew, had been cut out of the bank at the side of the river, both above and below water level.

The cavern was filled by means of a large trap opening which had been cut out of the bank below the surface of the river and which, when opened, caused the river to run sideways until the cavern was filled to the water level. At the far end of the cave leading out of the water was a flight of rough-hewn steps. These led into a narrow passage, from the end of which the dim light came.

Etienne looked round keeping a firm hold on the end of the rope. At his end of the cave, well above the water, was a small wooden shelf, and on this shelf was a box of the size of a large cigar box. He swam across and took the box from the shelf. Then, treading water, he peered towards the stairs and the passage. He knew that at the end of that passage Suan Chi Leaf was waiting, certain in his own mind that the only way out of the cave for Etienne was the way of the steps and passage.

Probably, Etienne thought, Twist Anderson was with him, too. The water cave had been the repository of his uncle's secret, and Suan Chi Leaf had intended that it should also be the repository of Etienne's body. Of course his disappearance would be easily explained. The punting accident would account for that.

MacGregor smiled quietly as he thought of the suave Chinaman waiting patiently. Then with a prayer that the trap opening beneath the bank was still open, and gripping the rope securely, he dived and commenced to draw himself hand over hand along the length of the rope. The trap was open, but it seemed years before he gained the surface of the river. He drew a grateful breath, swam for the bank, scrambled out, and with the box under his arm ran for the Sepoy Inn—and safety.

ONE hour afterwards, after a hot bath and supper, he

ascertained from the local exchange Twist Anderson's telephone

number, and rang up that gentleman.

"Hullo, Mr. Anderson," he said cheerily. "You sound a little depressed. I hope you are feeling well. By the way, if Mr. Suan Chi Leaf is with you remember me kindly to him. You might tell him, too, that the box contained a letter to my uncle's lawyers, and £500 in notes. It rather looks as if I'm getting the legacy by instalments, doesn't it? Tell Mr. Leaf that I'm sorry I couldn't leave the water cave by the passage, as you so carefully planned. If you take a look at the rope on the bank you'll see how I managed it. It would have been such a pity if I'd been drowned as a result of our little accident, wouldn't it? Better luck next time! Good-night 'Twist,' pleasant dreams!"

Mr. MacGregor hung up the receiver, and with a more than usually cherubic smile went to bed.

MR. ETIENNE MACGREGOR, at peace with the world, leaned back in a comfortable arm-chair in the lounge of the Rialto Hotel, and, sipping his tea, listened with appreciation to the orchestra. Etienne was not dissatisfied with life.

He had managed to answer the first two questions, and in doing so had enriched himself to the tune of £500. It was because of this affluence that he was staying at the Rialto, whilst his rooms in Mortimer-street were undergoing their annual spring clean. At the same time he was beginning to feel slightly impatient.

By this time he should have heard from his late uncle's lawyers with reference to the third question, for, the financial aspect apart, Etienne was keenly interested in the strange quests in which he found himself involved as a result of his uncle's will.

His eyes, wandering round the lounge, stopped for some moments on the figure of a lady who had just entered the lounge, and who was looking round as if in search of someone. She had a letter in her hand, and, as her glance fell upon Etienne she commenced to walk towards his table. MacGregor, apparently concerned with the orchestra, watched her as she approached. His curiosity was aroused. He got up as she stopped at his table.

"Are you Mr. Etienne MacGregor?" she asked.

He nodded. "I am that unfortunate person," he murmured with a grin. "May I do something for you? Will you have some tea?"

She smiled. There was no doubt that she was a very charming person. "I'm from Rudder, Foal and Rudder," she said, "and I've brought a letter. Mr. Foal thought it would be better if I delivered it myself. I'm his secretary."

She held out the letter to MacGregor.

"Thank you," said Etienne. "Now you must have some tea whilst I read it. Waiter, bring another cup."

He tore open the envelope and read the letter. He read it through quickly, and then reread it more slowly, but, although his eyes were apparently on the paper before him, in reality he was unobtrusively noting some details about the lady who sat opposite him sipping her tea. In the first place MacGregor was curious about the thin chain which she wore about her neck, and which disappeared into the top of her well-cut black georgette gown. The chain was obviously of platinum. Etienne sensed that there was some ornament attached to the chain, which he thought, had been deliberately slipped into the top of her gown, and why?

Already an idea had begun to take shape in MacGregor's fertile brain, as he turned his attention, this time with a shade more interest, to the letter before him, which read:—

Dear Mr. MacGregor—

My sincere congratulations on your success in finding the answers to the first two questions. The third concerns the age of your late uncle's partner, who is an aged Chinese—Mr. Ho Hang Leaf. His age is known only to two people: his wife, Mrs. Lotus Leaf, and his son, Mr. Suan Chi Leaf. I am permitted to give you this slight clue. There was an elderly Chinese named Yo Hang, who owns a curiosity shop off Clint-street, Long Acre, and who was a very old friend of Ho Hang Leaf, being born the same day. Perhaps you can find this old man. In the meantime I must formally request that you inform us of the correct age of Ho Hang Leaf within seven days from this date.

I am, yours faithfully,

H.G. Foal,

pp. Rudder, Foal and Rudder.

Solicitors.

MacGregor slipped the letter into his pocket, and consulted his watch. Then he gave an exclamation.

"By Jove!" he said. "There's a man waiting to see me in the smoke-room. I'd forgotten him. Please excuse me. I shall be with you again in two minutes. I'd like you to wait, because I want to send a note by hand to Mr. Foal."

He strolled casually out of the lounge, but once out of sight of the lady he hurried to one of the smoke-room telephones and rang up his rooms in Mortimer-street. "Look here, Mrs. Hands," he said. "I want you to ask Tommy to speak to me on the telephone—be as quick as you can, and when I've finished talking to him will you give him a sovereign for me. I want him to do something."

Mrs. Hands was quick, and in another minute the voice of Tommy, her fourteen-year-old son, came over the wire to Etienne's ears.

"Now look here, Tommy," said MacGregor. "Here's an adventure for you. We were fairly successful together last time. Take a cab immediately and drive to within about twenty yards of the Rialto Hotel. In a few minutes' time a young lady will come out. You'll recognise her, for I shall walk to the entrance with her. Keep your cab waiting, and if she takes a taxi follow her and let me know where she goes. Do you understand?"

"You bet, Mr. MacGregor," replied Tommy. "I won't lose her. If she goes a long distance I'll telephone you at the Rialto so that you shan't be kept waiting."

"Good man," said MacGregor. "You'll be a regular Sherlock Holmes before you've finished. Get round as quickly as you can!"

He replaced the receiver and rejoined his companion in the lounge.

"I'm so sorry to have kept you waiting," he said cheerily. "Won't you have some more tea?"

"No thank you very much, Mr. MacGregor," she replied demurely. "I really must be getting back. My mother is not very well and I'm afraid that she will wonder what has become of me. I must be going at once. I think I ought to take a cab."

Etienne walked with her across the lounge and through the entrance hall, making their pace as slow as possible. He was thinking that if Tommy Hands had hurried and had been lucky enough to secure a taxi at once he would arrive in time. In this surmise he was correct, for, luck being with him, it was quite some little time before the commissionnaire succeeded in getting a taxi for the girl and, as she drove off, Etienne saw Tommy's head come out of the window of a taxi-cab just down the street, give some hurried instructions to the driver and then disappear.

MacGregor watched the girl's cab speed off in the direction of Knightsbridge with Tommy in pursuit, and with a sigh of satisfaction he returned to the lounge, and over a cigarette ruminated on the plan in his head.

He realised that if his idea with regard to the girl who had called with the letter was correct he had not a great deal of time left in which to put his plan into execution. At the back of his brain an idea was taking shape rapidly—an idea by which he hoped within a few hours to become possessed of the correct age of Ho Hang Leaf, without consulting or obtaining the assistance of the Chinaman Yo Hang, who lived off Long Acre.

He walked into the smoke-room once more and telephoned to a Mr. "Slick" Walker, an acquaintance of the days when Etienne had been studying life in all its different aspects, a gentleman whose peculiarly clever and light fingers often found themselves in other people's pockets, but whose sense of humor was unfailing. After a short conversation with Mr. Walker, when an arrangement was made for a meeting at Knightsbridge Tube station in an hour's time, Etienne returned to his seat in the lounge, and waited patiently for the message from Tommy—the message on which everything depended.

Fifteen minutes afterwards Tommy telephoned. "That you, Mr. MacGregor?" he whispered tensely. "I followed her to March Mews, a little turning off Sloane-street. She went into a house there—I waited outside for about ten minutes. Then she came out, and a man came to the door with her. He looked like a Chinaman, and had a little black moustache. I pretended to be waiting to go into the house next door, and I heard him say to her, 'I shall meet you at my mother's flat, I shall leave here at eight forty-five.' Then she went off down Sloane-street, and he went back into the house. Can I do anything else, Mr. MacGregor?"

"Nothing, thank you, Tommy," answered Etienne. "That's A1. You've done your job very successfully. I'll come round and tell you about it tomorrow."

Outside the smoke-room, MacGregor consulted his watch. He realised how lucky it had been that he had made the appointment with "Slick" Walker at a spot near Knightsbridge. Things were shaping very well. He went to his room and got his hat; then, with a cheerful smile, he made his way slowly towards Knightsbridge tube station, where he found Mr. "Slick" Walker, his hands in his pockets and a cigarette stub adhering to his lower lip, studying with professional interest the diamond rings in an adjacent jeweller's.

AT a quarter to nine Mr. Suan Chi Leaf left his house in

March Mews and walked down Sloane-street. He appeared to be

quite satisfied with life, judging by the smile of satisfaction

which wreathed his thin, cruel lips. As he approached the corner

of Sloane-street and Knightsbridge, where there is always a

crowd of people waiting for the buses, Mr. "Slick" Walker, who

seemed to be waiting for a bus, knocked into him. Mr. Walker

apologised profusely, taking such a time over asking Suan Chi

Leaf's pardon that the Chinaman wondered at such good manners in

such an ill-dressed man.

Suan Chi Leaf continued on his way, until a tap on his shoulder caused him to stop and turn. He found himself looking into the face of a police constable and at the somewhat dignified and stern countenance of Mr. Etienne MacGregor.

"That's the man, officer," said MacGregor. "He brushed against me a moment ago, and immediately I missed my watch and chain. I saw him sneak off putting something into his waistcoat pocket. I'm certain that's him."

Suan Chi Leaf smiled. "This is ridiculous," he snarled. "This is what you call a 'frame up,' I suppose."

"We can talk about that at the police station," said the constable. "If you didn't steal this gentleman's watch, let's see what you've got in your pockets."

With a self-satisfied air Suan Chi Leaf turned out his waistcoat pockets. His face expressed the utmost amazement when he found, in his right-hand waist-coat pocket, the watch and chain of Mr. MacGregor. He commenced to argue, but ten minutes later found himself comfortably installed in a cell at Knightsbridge police station on a charge of picking pockets.

Etienne, with his most charming smile, then held a short conversation on the legal aspects of the case with the station inspector, and having ascertained from that worthy the address which Suan Chi Leaf had given when he was charged, which address MacGregor guessed would be that of Suan's mother—Mrs. Lotus Leaf—he left the police station and took a cab to that lady's flat in Oxford-street. Five minutes later found him ringing the bell at the Oxford-street flat. As he entered her sitting-room Mrs. Lotus Leaf regarded him smilingly, but beneath the smile lurked all the venom of her Oriental nature.

"What can I do for you, Mr. MacGregor?" she asked, regarding him intently. "Won't you sit down? Please make yourself quite comfortable."

Etienne grinned.

"It's awfully nice hearing you asking me to make myself comfortable, Mrs. Lotus Leaf," he said. "I appreciate your kind thoughts for my welfare, but I won't take up too much of your valuable time. What I want is to know the age—the exact age—of your husband, Mr. Ho Hang Leaf. You see that is the third question which I have to answer—the third of the thirteen questions which must be answered before I can inherit my uncle's money, I expect that you are rather surprised at my visit—you rather expected me to go to Mr. Yo Hang's in Long Acre tonight, didn't you, dear lady, and I expect that you and your equally charming son would have had a nice little surprise waiting for me when I got there. I gathered as much when you sent that charming and demure lady to my hotel with the letter, which you had typed on a sheet of Rudder, Foal and Rudder's note paper. You made one or two mistakes, though. Solicitors' typists don't wear 25-shillings-a-pair silk stockings, neither do they usually wear platinum neck chains, with immense diamond ornaments attached, which I noticed, although the lady had taken great care to wear it inside her dress. She forgot that lace is often transparent I was, therefore, forced to deal with the matter, and the position is briefly this. Half an hour ago your son, Mr. Suan Chi Leaf, was arrested in Knightsbridge for picking my pocket. My watch was actually found on him, and he is at the present moment in a cell at Knightsbridge police station. The point is this. If tomorrow, when he comes before the magistrate, I press the charge against him he will probably get six months' imprisonment, and be deported at the end of that term. Now I don't want him to be deported any more than you do. I find that you and he have helped me a great deal, in spite of yourselves, in answering these first two questions, and I want to put this proposition up to you. Supply me with the answer to the third question—give me the correct age of your husband, and I will call on Rudder, Foal and Rudder at 10 o'clock tomorrow morning. If the answer is correct I will withdraw the charge against your charming son, and he shall go free. If it isn't..."

MacGregor shrugged his shoulders.

Mrs. Lotus Leaf's long manicured fingers replaced carefully a tendril of her carefully-dressed hair. Then she looked at MacGregor with her usual smile—a smile that boded no good for him in the future.

"I agree to your terms, Mr. MacGregor," she said. "Mainly because it appears, that I have no option but to agree. I admire your brains. You say that in spite of ourselves we have been of use to you. We shall he more careful in the future. We are learning. Next time we shall make no mistake!"

She wrote the answer to the question on a sheet of note-paper, which she handed to him. "That is my husband's correct age," she said. MacGregor took the sheet of paper and rose.

"Thanks awfully, Mrs. Lotus Leaf," he murmured. "You are as charming as ever. I'm really very sorry that I can't oblige you by being a corpse! I do hope that your son won't be too uncomfortable tonight. It will give him an opportunity to think quite a lot, won't it? Goodbye, and many thanks!"

THREE minutes afterwards Mr. MacGregor might have been

observed walking down Oxford-street looking at peace with all

the world, and in the saloon bar of the Three Crowns in Seven

Dials Mr. "Slick" Walker held forth to a bosom companion on the

strangeness of life.

"George," observed Mr. Walker, "I've been pickin' pockets all me life, but, strike me pink, this is the first time in me life that a feller's ever paid me to pick 'is pocket and put 'is watch an' chain into somebody else's. It's a funny world, ain't it!"

IN spite of the cheerful and carefree expression which radiated from the round countenance of Mr. Etienne MacGregor as he strolled slowly up Regent-street, he was not feeling at all cheerful. Only three days remained for him to supply the answer to the fourth question which he had received four days ago from his late uncle's lawyers—the fourth of the thirteen questions which it was necessary for him to answer in order to inherit a fortune. He wondered if his luck had turned on him.

The first three questions had been easily dealt with—firstly, because of the keenness of the brain which existed behind Etienne's cherubic brow, and, secondly, because of the involuntary assistance he had received from Mrs. Lotus Leaf and her son Suan Chi Leaf. But this fourth question was a poser. He had not the slightest idea where to start in an endeavour to find the solution.

On reading Rudder, Foal and Rudder's letter, it had seemed to him that possibly this was the easiest question up to date. They had requested that he should inform them, within the stated seven days, what exactly were the contents of the China tea chest which had stood, in the chief clerk's office in his late uncle's warehouse at Wapping.

Etienne had immediately visited the warehouse, and found it not only dilapidated, but also closed, and apparently it had been deserted for years. No one in the vicinity could give him any information, neither could any of his uncle's old employees, whom he had hunted up, give him any information as to any China tea chest. And there the matter stood.

Immersed in thought Etienne slowed down and looked into a shop window at a set of expensive silk pyjamas. He was not really concerned with the pyjamas, but he considered that the splash of color in the window was attractive, and that it might be conducive to a brain wave. After a moment he was preparing to move away, when his attention was attracted and held by the reflection of a face in the plate glass window before him. It was the face of Mrs. Lotus Leaf.

Now although Mrs. Lotus Leaf was Chinese she was very beautiful, and Etienne, although he had no cause to love her, but a great deal of cause to dislike her, would have looked at her reflection any time. But on this occasion he was more than interested, for the expression on her face was so fiendishly triumphant that it almost brought a gasp of astonishment to his lips. He looked casually at the contents of the window once more, and then walked slowly away in the direction of his rooms in Mortimer-street.

Arrived there, he lit his pipe, and throwing himself into an arm-chair, allowed his mind to run on Mrs. Lotus Leaf—there had been no mistaking the expression of triumph on her face, and there was only one reason for this expression. She knew that MacGregor had not yet succeeded in answering the fourth question. It seemed to Etienne that, this being so, there must be some definite reason for her knowledge, and the most obvious one was that the China tea chest was in the possession of either Mrs. Lotus Leaf or her son, or both of them. This being so, she would have every reason for her triumph.

Etienne considered that his theory was supported by the fact that his old uncle had probably insisted on the China tea chest question being asked in order that Etienne might have another opportunity to match his wits against the Chinese. Puffing away at his pipe, he got up and walked over to the window. It had commenced to rain, but on the other side of the road, huddled up against the wall, stood a lounger—the type of man usually seen selling matches in the street. This in itself would not have interested Etienne, but he had seen the man before, and on both occasions he had been standing on the opposite side of the road, his hands in his pockets very busily engaged in doing nothing.

Etienne came to the conclusion that the man was probably employed by Suan Chi Leaf to keep the MacGregor flat under observation. Suddenly an idea came to Etienne, and he grinned happily. A scheme had suggested itself to him whereby he might find the headquarters of Mrs. Lotus Leaf and her son. Once he could do this, he knew that the China tea chest would not be far away. If by some means he could get the idea into the heads of Suan Chi Leaf and his mother that he knew of the whereabouts of the China tea chest and was going to make an attempt to discover what the contents were, it seemed to him that they might take some action which would give him a clue. In any event, something had to be done, and within the next three days, if he were not to lose all chance of obtaining the legacy.

He seized the telephone from his writing table and rang up Fletter's Detective Agency, a reliable firm which he had used on previous occasions. In two minutes he was connected with Fletter himself.

"Now listen carefully, please, Mr. Fletter," he said. "I'm speaking from my rooms in Mortimer-street, and there is a lounger on the opposite corner—a clean-shaven fellow dressed in a ragged fawn overcoat. I want you to send a man along at once to keep this fellow under observation, and when he goes off I want your man to follow him. Got that? Good."

He hung up the receiver and proceeded to carry out the second part of his scheme. He took a sheet of notepaper and wrote a note to Mr. Foal, of Rudder, Foal and Rudder, which read:—

Dear Mr. Foal,

I am in a position to tell you that I shall be able to supply the answer to the question with regard to the contents of the China tea chest within the next forty-eight hours.

I am,

faithfully yours,

Etienne MacGregor.

He placed this letter in an envelope, addressed and stamped it, and slipped it into his pocket; then he took up a position just behind the window curtain, where he could keep the watcher on the other side of the street under observation. About fifteen minutes afterwards Fenway, one of Fletter's most reliable men, appeared in Regent-street, just opposite the end of Mortimer-street, and it was apparent to Etienne that he had recognised Suan Chi Leaf's man and was keeping out of the way for the moment.

MacGregor now put his plan into execution. He rang his bell, and when the house-maid appeared he handed her the letter which he had written to Foal, and gave her certain explicit instructions. Then, taking up his previous position by the window, he watched the man outside. A few minutes afterwards the house-maid, bearing in her hand the letters for the post, crossed the road to the pillar box on the corner of Regent-street.

As she passed the lounger, who still stood leaning against the wall, a letter fell, apparently unobserved, from her hand, and lay in the gutter. The lounger waited until the girl had returned to the house, then, with a quick glance up and down the street, pounced upon the letter. He disappeared into a doorway, and presumably read the note to Foal, and then to Etienne's great delight hurried off as quickly as his legs would carry him, with Fenway unobtrusively in pursuit.

MacGregor chuckled at the success of his little plot. His fake letter to Foal would be in Suan Chi Leaf's hands in a little while, and that gentleman, believing that Etienne had some clue to the mystery of the China tea chest, would probably make some movement which would give Etienne the required clue.

At 8.30 the telephone bell rang, and Etienne took off the receiver to hear Fenway's voice.

"That you, Mr. MacGregor?" said the operative. "I've had a rare chase after this fellow. I followed him down to some deserted warehouse in Wapping, where, unfortunately, I lost him. I hung about, and some time afterwards he turned up again, but this time there were two people with him—a man and a woman. They rowed out from some steps that lead down to the river at the side of the warehouse, and I lost sight of them. There's a mist on the river tonight. That's all up to the moment, sir."

With a word of thanks, MacGregor hung up the receiver. There was no doubt that his little plot had succeeded. Suan Chi Leaf on receiving the fake note to Foal had promptly come to the conclusion that MacGregor knew the whereabouts of the China tea chest, and had gone off with his mother to ensure its safety.

Etienne slipped on his overcoat, and hurried out into Regent-street, where he procured a taxi and ordered the driver to make for the Wapping warehouse as quickly as possible. It seemed to him that the China tea chest was probably aboard some boat belonging to Suan Chi Leaf out in the river, and he had made up his mind to look for any suspicious-looking craft in the vicinity of the warehouse.

He paid off the cab at Wapping, and walked quickly to the warehouse, which fronted into a mean street, and the back of which was actually washed by the river. He could see little, for the mist described by Fenway had thickened. After a moment's thought he made for the stairs by the side of the warehouse, a wooden flight running down to the river. Peering out over the dark water he could make out dimly the lights of several boats which lay moored to buoys behind the warehouse, and he made up his mind to inspect these.

A dinghy was moored to the steps, and he jumped into this, and, untying the painter, pulled out on to the river. Suddenly he lay on his oar and waited. Above him, shining dimly from the black wall of the warehouse was a light. One of the back upper rooms was occupied, for there could be no other reason for the illumination.

He pulled silently back to the warehouse, paddling the dinghy along the wall and feeling for any door or other entrance to the warehouse. Presently he found what he sought. An iron ladder ran up from the water in the direction of the light above him. Apparently it was a fire-escape, and the light was coming from an open trap on the second floor of the warehouse, used in former days for lowering cases down to the river barges.

Etienne tied the dinghy to the iron ladder. The river in his vicinity appeared to be deserted, and only the occasional hoot of a siren broke the stillness. Then, as silently as possible, he commenced to climb the ladder. He climbed warily, moving slowly as he approached the open trap. When his head was just below its level he paused in his climbing and listened intently. A peculiar sound came to his ears—the sound of a man snoring!

Inch by inch Etienne raised himself on the ladder until he was able to look into the dimly-lit room. Then an involuntary gasp escaped him. The room had evidently been used once on a time as an office. Some bits of dirty and broken-down furniture stood about the place, and along one side of the wall was a dilapidated settee, and on this settee stretched to full length and snoring heavily lay a six-foot man of the hooligan type. Against the back wall of the room, four or five feet behind the sleeper, stood a rough table, and on this table stood a small and richly inlaid engraved chest—the China tea chest!

Etienne commenced quietly to descend the ladder once more, and, having reached and untied the dinghy, pulled a few yards away from the warehouse and lay on his oars whilst he considered the situation. One thing was absolutely obvious to him—a trap had been set for him, and one into which he had not the slightest intention of walking!

The China tea chest so carefully set out on the table and guarded by the large gentleman who was pretending to be asleep and snoring much too loudly to be convincing. Etienne had no doubt that on the other side of the door, at the far end of the room, Suan Chi Leaf and his satellites were waiting to seize him immediately he put his foot into the room.

He pulled the dinghy back to the steps by the side of the warehouse, and sitting down a few steps above the water's edge, gave himself up to deep thought. The fog had lifted, and his eyes, wandering over the surface of the river, encountered a long, grey boat moored to an official landing-stage which stood some fifteen yards to the right front of the warehouse. Then, as an idea took shape in his mind, his usual broad grin reappeared on his face, and he ran quickly up the steps.

At the top he gazed about him until he saw the lights of a public house twinkling down the street. Then, with a cheery smile he walked towards the Blue Boar, whistling.

Twenty minutes afterwards Etienne held an informal

meeting at the end of a dark lane which ran to the left of the

warehouse. The meeting consisted of six individuals collected by

Etienne from four public houses—gentlemen of the type

which is not a bit particular as to how it gets money, so long

as it gets it!

He explained carefully to this motley crew exactly what he wanted, and then taking twelve one pound notes from his pocket, he tore them carefully in half and handed each member of the meeting two of the torn halves. "Now, gentlemen," he said, "when you've carried out my instructions I will hand you the other halves of the notes. As you doubtless know, the smaller halves which I have given you are worthless. I'll meet you here in ten minutes' time."

"That's all right, guv'nor," said the self-appointed leader of the men. "It's as easy as shellin' peas. Come on, boys!"

Etienne ran back to the stone steps, descended to the dinghy, and casting off pulled out on the river until the boat lay a few yards off the bottom of the iron ladder. The room at the top of the ladder was still lit up, and the faint sounds of snoring still came to Etienne's ears.

Suddenly a terrible hubbub occurred. From the street behind the warehouse came cries of "Fire," and to his left MacGregor could just discern one of his hirelings dashing along the pier to the stage where the long grey craft—the Thames fire-boat—was moored. "Fire!" yelled this gentleman at the top of his voice. "Fire!"

And as the crew of the fire-boat tumbled on deck—"There it is, in that warehouse where the light is—look sharp for 'eaven's sake."

With one look at the fire-boat Etienne pulled for the bottom of the iron ladder. As he did so a strong stream of water shot from the automatic hose at the stern of the fire-boat straight into the room at the top of the ladder.

As he reached the top and looked into the room he roared with laughter. The terrific stream of water was playing straight on the now open door on the far side of the room, and in the dim light of the spluttering lamp Etienne could discern the drawn face of Suan Chi Leaf as he made attempt after attempt to enter the room, to be driven back each time by the force of the water.

MacGregor wormed his way over the top of the ladder, and crawling forward on his stomach, keeping well under the stream of water which played above him, succeeded in reaching the table. He pulled it over, and in a minute the China tea chest was in his arms, and he was wriggling back to the ladder. In a minute he was in the dinghy and pulling for the steps.

Fifteen minutes afterwards Etienne, having paid off his satellites, wandered to the edge of the crowd which surrounded the warehouse, and had the satisfaction of watching Mr. Suan Chi Leaf trying to explain to an infuriated policeman what he was doing in the warehouse. Then he hailed a cab, and with the chest beside him drove cheerfully back to Mortimer-street.

ETIENNE MACGREGOR, lying at full length in the heather which covered the slopes of Cammock Hill, a pair of field glasses held to his eyes, searched the long, flat stretch of ground which lay immediately beneath him until he discovered what he sought.

Three-quarters of a mile away, approaching from the direction of Newmarket, a party of mounted men appeared, and Etienne kept his glasses on them until they were near enough for him to recognise his man. In advance of the party rode a stable lad mounted on the horse Greensleeves. There was no mistaking Greensleeves—a distinctive brown horse of average build and height with three white stockings. Behind the lad on Greensleeves rode the trainer, a gentleman whose broken nose told of more than one "rough house." To the right and left of the trainer, mounted on hacks, were two tough-looking fellows, who, Etienne imagined, were acting as stable guards for Greensleeves. Behind this party, smoking a cigarette, and smiling pleasantly, rode Suan Chi Leaf, immaculately dressed for riding.

Etienne watched them for a moment, and then, throwing the field glasses down beside him, turned over on his back and gave himself up to deep thought. He was engrossed trying to solve the fifth question. The letter from his late uncle's lawyers reposing at the moment in his breast pocket asked him, within the usual seven days, to inform them as to the number of teeth which were missing from the mouth of the racehorse Greensleeves, originally owned by his uncle.

They had given him a slight clue in the statement that the horse had been sold to a Mr. Jones Llewellyn, but it had taken Etienne four days to trace that gentleman and to discover that the horse had been sold by him to Suan Chi Leaf, and, with the help of Fletter's Detective Agency, to trace Suan Chi Leaf to Garran Manor, near Newmarket.

Of course Suan Chi Leaf had bought the horse because he knew what the fifth question was, and because he had no intention of allowing MacGregor to obtain any opportunity of inspecting the mouth of Greensleeves in order to discover which teeth were missing. Suan Chi Leaf and his mother, Mrs. Lotus Leaf, were much too perturbed by Etienne's success in answering the first four questions to take any chances.

MacGregor had taken rooms in a village a few miles from Garran Manor, and, under cover of night, had scaled the high wall which surrounded the old house, and inspected the place as thoroughly as he was able. But this inspection had shown him that there was little chance of getting anywhere in the vicinity of Greensleeves.

The horse was securely housed in a stable immediately adjoining the house. A man was on guard at the stable door all night, and in a barn close to the stable three or four Newmarket "toughs" slept so as to be within call of the guard should an alarm be given.

As Etienne lay on his back looking at the blue sky above him he racked his brains vainly in an endeavour to think of some plan by which he might once more outwit the wily Suan Chi Leaf. One thing was obvious, and that was that by some means or other he must obtain some opportunity of inspecting Greensleeves. His mind busy, he rose to his feet and commenced to walk across country in the direction of his inn at Seffcot. He was so engrossed in his problem that he failed to observe the individual who had overtaken him, and was walking alongside until the man commenced to speak.

Then MacGregor took stock of his companion. He was a tall, thin fellow, dressed in a pair of very old but well-fitting riding-breeches, and a carefully patched coat. He was well-shaven, and wore a bowler hat rakishly over one ear; a long straw was in his mouth, and he exuded an atmosphere of stables and horses. Etienne guessed that he was some hanger-on from one of the big racing stables at Newmarket.

"Good morning, sir," he said, touching his hat with his forefinger. "It's a lovely day. I suppose there isn't anything which I could do for you, sir?"

Etienne, rather amused at this greeting, lit his pipe, and looked over the match at the horsey-looking gentleman.

"I don't know," he said eventually. "What do you usually do for people?"

The man grinned. "Well, sir," he said, "as you may have guessed, I am an expert on horses. Yes, sir, there isn't anything about a horse I don't know. I've got a way with horses, I have. I can make 'em do anything I like!"

Etienne smiled. "That's rather an unusual accomplishment," he said. He looked the man over with more interest. There was something in the good-humored, hungry-looking face which appealed to him. It occurred to him instantly that it would be amusing to tell this chance acquaintance of his present difficulty, and see if he, with his knowledge of horses, could offer any solution. He drew his cigarette case from his pocket and gave the horsey man a cigarette.

"Look here," said MacGregor, as the other puffed gratefully, "I am engrossed at the moment with a rather unusual problem, which concerns the number of teeth in the mouth of a certain horse. The horse is in the stable at Garron Manor, and is guarded night and day, and I am afraid that any attempt I might make to get into the stable would be thwarted. Now if you've got any ideas on the subject I shall be glad to have them."

"Ah," said the horsey-looking gentleman, gazing ahead at the blue horizon. "Now, that's very interestin' that is, an' might I ask what manner of horse this horse is, sir. What does he look like?"

Etienne described Greensleeves as nearly as possible. When he had finished the horsey-looking gentleman came to a standstill rather suddenly, and, putting his hands into his breeches pockets, faced MacGregor.

"My name is James Tope, sir; Jimmy I'm usually called, an' if you'll be good enough to tell me where I could see you in, say, three or four hours' time, I think I might be able to produce an idea, so to speak."

"I'm staying at the Green Man at Saffcot," answered MacGregor. "You'd better meet me there at 4 o'clock. Come and have tea?"

Mr. Tope grinned. "That'll be very welcome, sir," he said. "I think I'll get back to Newmarket and find out one or two things, after which I'll join you at tea, which, as I have said, will be very welcome, especially if it's a meat tea!"

So saying, Mr. Tope with a grin raised his forefinger half way to his very horsey bowler hat and turned back in the direction of Newmarket. MacGregor, his round face illuminated by its usual cherubic smile, watched the tall figure as it strode away. For some reason for which he could not account he had a decided feeling that Mr. Tope would and could assist him in solving the Greensleeves mystery.

THREE hours after Etienne and Mr. Tope took tea together at

the Green Man Inn, Mr. Tope had gathered a fund of information

with reference to Greensleeves, in and about Newmarket.

Apparently, Suan Chi Leaf proposed to run the horse in a race in

the near future, and in the meantime was taking the utmost care

that there was no possibility of anyone approaching

Greensleeves. The horse was taken out for exercise each day,

accompanied, as Etienne had seen, by a veritable crowd of

attendants and guards, and as Mr. Tope so aptly pointed out, no

opportunity could be found on these occasions to examine the

horse's mouth.

Etienne found his hopes, which had risen slightly after his meeting with Mr. Tope, rapidly disappearing.

"It looks as if we are as far away as ever, Tope," he said gloomily. "If we can't get at the horse during exercise, and we can't get at him when he's in the stable, what can we do?"

Mr. Tope drank his fifth cup of tea.

"Well, sir," he said, "I've had a look round at Garran Manor. There's only one entrance—through the main gates, and the wall which surrounds the grounds is quite high; also, there's a lot of shrubbery about the place inside. Now, I had a little idea, sir, an' if you could let me have, say, twenty pounds, I think that tomorrow night we might have a look at Greensleeves!"

Etienne listened to Mr. Tope. Then he produced the twenty pounds, and watched that gentleman as he swung off down the Newmarket-road, after which Mr. MacGregor repaired to the saloon bar of the Green Man and stood himself a large whisky and soda with much glee.

NEXT night, shortly before midnight, Mr. Etienne

MacGregor, accompanied by Mr. Tope and three of Mr. Tope's

particularly intimate friends, who had been recruited by him

during the afternoon, also a horse and cart, containing boards,

ropes and other implements, and a travelling loose-box, drawn by

another horse, travelled slowly across the downs in the

direction of Garran Manor. They arrived shortly after one

o'clock, and the all-clear having been signalled by Mr. Tope,

who, with the inevitable straw in his mouth, had gone on ahead,

the cavalcade drew up beneath the shadow of some giant oaks

which stood near the high wall surrounding the Manor.

Mr. Tope then took charge, and under his direction all sorts of activities took place, and the boards, ropes and other implements having been brought out and assembled to the satisfaction of Mr. Tope, the five conspirators withdrew into the shadow of the trees and discussed the plan of action once more in order to avoid the possibility of a mistake.

Then, with a parting word, Etienne quietly ascended the gangway formed by the planks, which ran over the high wall and into the Manor grounds, and carefully crept forward to the edge of the shrubbery, from which position he could look across the lawn at the stable door which directly faced him. It was a fine night, and he could see plainly the man on guard outside the stable doors, in his shirt sleeves, smoking his pipe. Five minutes afterwards a hand was laid on Etienne's shoulder, and a bridle slipped into his hand.

"'Ere you are, Guv'nor," wheezily whispered one of Mr. Tope's friends, "and don't fergit—directly you 'ear the whistle make for the entrance gate. There's a guard of three men there. Don't be in too much of an 'urry."

"Right," whispered Etienne, and the man crept away. Etienne crouched in the shadows. Then to his ears came the sound of a soft whistle. At the same time a shout echoed across the grounds. Etienne saw the man at the stable door start forward, and then fall as Mr. Tope hit him across the back of the head with a sand-bag.

Then, as Suan Chi Leaf's additional guard commenced to make for the stables, Etienne flung himself across the horse's back and set off at a half gallop for the entrance gates. As he rode across the lawn he glimpsed Suan Chi Leaf, in a dressing gown, and the rest of his men chasing after him. As he neared the gates Etienne checked his horse, just as a dozen hands stopped his progress. Etienne dismounted with an exclamation of disgust.

"Just my luck," he said. "I thought the gates would be opened."

The men stood round him in a threatening half circle. They made way as Suan Chi Leaf appeared. The Chinaman lit a cigarette, and smiled amiably at Etienne.

"My condolences on the failure of your little plot, Mr. MacGregor," he said. "As I notice that you have not had time to remove the hood and cloths of my horse Greensleeves, it is obvious that you have not yet examined his mouth, and that you are, therefore, still in ignorance of the little details which you have taken so much trouble to endeavour to ascertain. Smith, take the horse back to the stable, and open the gate for this gentleman. Good-night, Mr. MacGregor. I am afraid that you will have a rather lonely walk back to Newmarket. Good-night—my best wishes go with you!"

Suan Chi Leaf grinned cynically as Etienne, with a shrug of his shoulders and a disappointed expression, passed through the gates.

AT 3 o'clock on the next afternoon Mr. Jimmy Tope, his

hat carefully cocked over one eye, and the straw in his mouth

set at a jaunty angle, rang the bell of the entrance gates of

Garron Manor, and the gates being opened passed through.

Mr. Tope, with the expression of a man who has done his duty nobly and well, handed the bridle of the horse he was leading to the astonished gatekeeper, together with a note addressed to "Suan Chi Leaf, Esq."

Then, with a cheery nod, he turned on his heel, and whistling the latest fox-trot walked off.

Suan Chi Leaf, sitting with his mother in the pleasant conservatory, was rather surprised to receive the note. He was even more surprised when he opened it and read it. As his eyes scanned the last lines and the signature the note dropped from his hand, and he gazed straight before him, his features distorted with rage. Mrs. Lotus Leaf picked up the note and read:—

My Dear Old Suan,—

I return herewith your horse Greensleeves by my trusty retainer Mr. Tope, who is, believe me, some expert on horses. The credit of this business belongs to him. Knowing how carefully the stable was guarded, he suggested that Greensleeves might be provided with a double, and the horse that your men so carefully stopped me on last night was a brown horse of the same size as Greensleeves, carefully painted with white stockings by friend Mr. Tope. Whilst you were all so keenly chasing me to the gates (which we knew would be shut), dear old friend, Tope and his merry men were getting the real Greensleeves out of the stable and over the bridge which we fixed up over the wall behind the shrubbery. I have this morning sent Rudder, Foal and Rudder the information they required, and everything in the garden is lovely! My best wishes to yourself and your charming mother. Let me know when Greensleeves is running. Both Mr. Tope and myself would like to back him. My felicitations!

Yours, Etienne MacGregor.

And perhaps it was just as well that Mrs. Lotus Leaf said what she did say in Chinese!

ETIENNE MACGREGOR gazed moodily into the fire and bit savagely on the mouthpiece of his pipe. For once, his usual cheerful expression had vanished, and there was a determined look about his mouth which showed plainly that the matter that was troubling him was of an unusually serious nature.

Where was the "Yellow Kaffir"? This—the sixth—question asked by his late uncle's lawyers six days ago was yet unanswered, and Etienne knew that unless the answer was forthcoming within the next twelve hours he could give up all hope of inheriting his uncle's large fortune.

Certain facts had been easily ascertained. The "Yellow Kaffir" was a large diamond, not very valuable, but valuable enough, with a yellow flaw in its lustre, which had given it its unusual name. The diamond had been owned by his uncle, but where it was or where some clue to its whereabouts could be obtained Etienne had not the slightest idea.

In the previous questions which he had successfully answered there had been often some indication which had set him on the right track, or else some step taken by Suan Chi Leaf or his wily mother, Mrs. Lotus Leaf, to keep Etienne from finding the solution to a question had served as a clue which his quick intelligence had seized and acted on.

His eyes wandered to the mantelpiece and the squat Chinese idol which was placed in the centre. The idol had been sent to him a few days before by Rudder, Foal and Rudder, who had informed him that it was one of the few articles which his uncle had directed should be handed over to him.

At first Etienne had hoped that it might prove some indication as to the whereabouts of the Yellow Kaffir, but an examination had proved that the idol was carved out of some heavy stone, and there was no inscription or writing upon it as Etienne had hoped. Last night an attempt had been made to break into the house in Mortimer-street in which Etienne had his rooms, but the attempt had been frustrated owing to the quickness of the policeman on duty. He wondered if Suan Chi Leaf was behind the attempted burglary—and if so, why?

On previous occasions the Chinese had been too obvious in their intentions to prevent Etienne finding the answers to the riddles set him by Rudder, Foal and Rudder, but during the last week there had been no sign of Suan Chi Leaf or his myrmidons, a fact which caused Etienne some uneasiness. He wondered if the Yellow Kaffir were in the possession of Suan Chi Leaf, and if that cynical gentleman, sure in the knowledge that Etienne could not supply the answer to the question, was lying low until the seven days which MacGregor was allowed in which to answer were up.

Where was Suan Chi Leaf? This was the next point which troubled Etienne. The flat of Mrs. Lotus Leaf in Oxford-street was closed, and the tenant gone. The Three Leaves Club in Limehouse, another headquarters of the nefarious pair, had been raided. Fletter's Detective Agency, a reliable firm, who had been used before by Etienne, had up to the moment failed to trace either Suan Chi Leaf or his mother.

Etienne got up, and commenced to pace up and down the room. It seemed to him that he was beaten this time, and that the risks he had previously taken in answering former questions had been in vain. His luck, which had been so good in the past, had deserted him, he thought, and he was considering resigning himself to the inevitable, when with a suddenness which made him start the telephone rang. He took off the receiver and answered.

"That you, Mr. MacGregor?" said a voice. "This is Fenway speaking—Fletter's head man. I've been after Mr. Suan Chi Leaf for the last five days, and think that I've got a line on him at last. I picked up one of his men this evening and followed him down to Hounslow. I lost him on the edge of the Heath, but unless he intended to take a very long walk for the sake of his health there could be only one place to which he could be going—the old Mill House, which stands well in the centre of the Heath. I thought I'd better telephone and tell you."

Etienne, after a word with the man, hung up the receiver. There was only one thing for him to do. He must at once go to Hounslow and investigate the old Mill House. Anything was better than inaction. And there was just a chance—a slim chance—that Suan Chi Leaf might be there, and that he might have the Yellow Kaffir.

He opened a drawer and slipped a heavy automatic pistol into his pocket, and then hurried round to the garage in Portland-street where his motor-bicycle was kept. Five minutes afterwards, with the throttle wide open, he was speeding through the night towards Hounslow.

FROM the thicket in which he had hidden his motor-cycle

Etienne could discern dimly the outline of the old Mill House,

which stood on the most lonely and unfrequented part of the

Heath. At first the place had seemed to be in complete darkness,

but as he moved away from the thicket he could see a dim light

burning in one of the upper windows. He approached cautiously,