RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

"THE GOLD KIMONO" is one of four "lost" Peter Cheyney novels recently discovered in the digital newspaper archives of the National Libraries of Australia and New Zealand. The titles of the other three are: "Death Chair," "The Sign on the Roof" and "The Vengeance of Hop Fi."

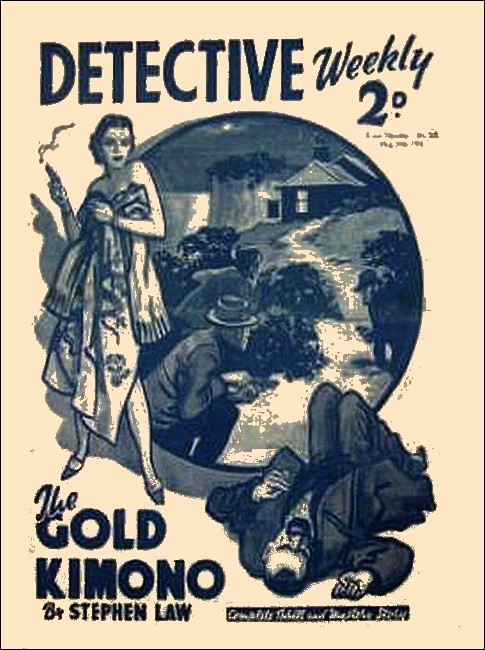

In 1937 the British magazine Detective Weekly published three short novels with the titles "The Gold Kimono," "The Mark of Hop Fi" and "The Riddle of the Strange Last Words," all under the by-line "Stephen Law," which is evidently a pseudonym used by Peter Cheyney. The first of these works is a version (presumably abridged) of the serial published in Australia and New Zealand.

Detective Weekly, May 29, 1937, with "The Gold Kimono"

The text used to create the present RGL version of "The Gold Kimono" appeared in The Sunday Times, Perth, Australia, between October 5 and December 28, 1930. Typographical, OCR and other obvious errors have been corrected without comment.

Thanks go to the Australian bibliophile Terry Walker for processing the digital newspaper image files of the serial used to make this e-book.

—Roy Glashan, May 1, 2017

JOSIAH PEABODY, swinging along the cliff top running from Stranover to Hetton-on-the-Strand, noticed events only subconsciously. His conscious mind was much too busy to be aware of little things.

The sea mist, which had already enveloped the smooth sands; the few spots of rain which were falling—large occasional spots heralding a storm; the gusty wind, which, for the moment, was holding up the rain; all these things were to him only vague things.

Also, he was too familiar with his surroundings to be interested in them, for many week-ends during the year found Josiah Peabody on the Stranover-Hetton cliff road. Often he wondered why he did it, why he was so attracted to the lonely road and why he did not allow the unfortunate past to die as so many other things had died.

Kenkins, that medical materialist, had had the effrontery to voice this thought. Peabody had said nothing. He had only looked at Kenkins with his usual quiet smile, and that worthy possessed sufficient tact to leave the subject well alone. After that Kenkins kept his thoughts to himself. In any event he had little use for women.

O'Farrel understood. It was entirely plain to the nervously instinctive O'Farrel why this tall quiet man whose name was the only incongruous thing about him and whose inevitable smile served as a very effective mask for despair, wandered about the moorland roads which run across the country between Stranover, Hetton, Salthaven and the sea. When one says nothing one must needs think.

Peabody said nothing, and his thoughts came easier in these lonely places, where he conned over the things which had happened there, and vainly tried to arrive at some logical conclusion.

And a logical conclusion was impossible. Peabody realised that. There would never be an explanation. O'Farrel, on one occasion, heartened by a strange burst of confidence from Peabody, who, almost at breaking point, had actually broached the subject—O'Farrel had put the thing plainly.

"Why shouldn't she disappear, Peabody?" he had said. "There was every reason for it! Consider the matter from a proper point of view. Here you are in North Russia, a temporary Engineer Captain, serving at the fag end of a good looking war. Suddenly, there appears a woman. Very beautiful, very fascinating. She says she is running from the Bolsheviks. You believe her. She says that her entire family, with the exception of a brother who is a prisoner in Moscow, have been murdered by the said Bolsheviks. You believe her. She says she loves you. You not only believe her, but you also marry her on the strength of it, there and then. You return to England and you are demobilised. You plan a honeymoon, and you go to Stranover. Then, two weeks afterwards your wife disappears with all the loose change she can lay her fingers on. Well, why shouldn't it happen? The whole business has been so illogical that the ending was in keeping with the beginning. You knew nothing about her except what she told you. You know nothing about her now. Forget her, my Josiah. There are lots of other women in the world, besides which you are inclined to be a good-looking man, and they like strong, quiet specimens like you, my bucko! She may appear again, quite possibly. If she does I hope you don't meet her, that's all, for in your present state of mind you'd be at her mercy again. She'd have you on the end of a little string, my Josiah. Besides, how do you know that she hasn't got husbands all over the world. Very probable, I think!"

Deep in his heart Peabody thought that O'Farrel might be right. But it had been impossible to forget her. Wandering along the road, he had picked out spots where they had rested on long walks. Spots where they had picnicked. He had to remember. Peabody had, from boyhood, repressed every obvious emotion to such an extent that now he was quite unable to realise that whether the woman was good, bad, or indifferent, she was entirely necessary to him, that he loved her. To have admitted this to himself would have been emotional, and Peabody was never that.

To his left, over the wide stretches of moorland running back to Salthaven and the bleak hills beyond, the black clouds were flying. A heavy gust of wind flung the sodden leaves over the asphalt road. Peabody strode on, his pipe empty between his teeth, still thinking, still trying to worry something out. The rain, falling more quickly now, blew into his face and stung.

Further down, a narrow bye-road ran off across the moor, the road to Salthaven. Some way down this bye-road, standing within a rickety fence, he could discern in the mist the blurry outline of Sepach Farm, which he had intended should be the limit of his walk.

Sepach Farm interested him to-day. A square, two-storey building, deserted, and locally reputed haunted, the desolate place seemed in some way to fit into his mood. Life seemed rather like Sepach Farm, thought Peabody.

They had never entered the farm, but on one grey day—a day not unlike this, they had sheltered from the rain under the wide window-ledge of the low, first storey window. She had joked about the English weather....

From behind him somebody called, breaking into his meditation. Peabody stopped and looked round. Walking towards him he saw a short thick-set and florid-looking individual, wearing a well-cut suit of brown plus-fours and a cheerful smile. He was puffing, and seemed a little out of breath. Peabody wondered where he had sprung from. He had noticed no one on the road previously, but he surmised that the individual in plus-fours might have been on the moor behind the hedge which bordered the land side of the road.

As Plus-Fours approached he knocked out a stubby little pipe—rather like himself, that pipe, thought Peabody—against the palm of his hand.

"Sorry to interrupt your walk," said the stranger, "but does your name happen to be Truesmith?"

Peabody shook his head. "Sorry. It isn't," he said, with his usual smile.

"Ah," said Plus-Fours, "that's bad luck. I'm very keen to find a fellow called Truesmith. Expecting him to be about this part of the world to-day. Going far?" he inquired pleasantly, refilling his pipe.

"Just walking," said Peabody.

"Good exercise," said Plus-Fours. "Good exercise. Well, I'll be getting back, I think. Tea and crumpets. Thought of going to the Turkish Café, but I think I'll walk back to Stranover. I don't think I'm too keen on the Turkish Café. Are you?"

"Never been there," said Peabody.

"Haven't you, though?" said Plus-Fours. "I suppose you don't belong round here, although why anyone should notice the place I don't know, stuck away as it is on that ledge of cliff. Funny idea building the place at all. You don't know who it belongs to, I suppose?"

"No, I don't," said Peabody. He was still smiling, but his brain was rather seriously concerned with the gentleman in plus-fours. Somehow, to Peabody, there seemed some definite purpose in the conversation.

Why should he be Truesmith? The original question seemed to Peabody to constitute simply an excuse, but the following questions and the remarks about the Turkish Café surely had some motive other than idle curiosity? It was raining steadily now, and is was hardly usual for two strangers to stand in a rainstorm and talk about nothing.

"You can't have been down here lately," said Plus-Fours. "The Turkish Café is along the road here, on a sort of gallery cut in the cliff face. They meant it for a shelter at first, I think, and then someone bought it and turned it into a café. Funny idea. Very few people come far along this road unless they're going to Hetton, and people who go to Hetton aren't usually the people who want to drink tea. Of course, in the summer there are a few visitors. Ever come down here to the summer? You don't? Not a bad spot if the weather is all right."

Plus-Fours smiled amiably at Peabody. He looked rather like a big child, and a raindrop running down his nose gave him a peculiarly humorous appearance.

"Well, well, I'll be getting back to Stranover," he said. "You'll be pretty wet won't you," he added. "There's nowhere about here to shelter except the café, or at Sepach Farm... neither of 'em very attractive, I must say!"

"I don't mind rain," said Peabody.

"Quite," said Plus-Fours airily. "I think it's quite nice sometimes. We get too much of it in this country though. Well... good afternoon."

He nodded and, turning about, walked off abruptly. Peabody stood still until the mist had swallowed the gentleman in plus-fours. Then he turned and continued his walk.

SO somebody had started a café in a gallery cut into the cliff face? Peabody thought that Plus-Fours seemed extremely interested in this fact. He wondered whether he spent his afternoons hanging about the Stranover-Hetton road and talking to odd people about odd things.

About him the telephone wires on the left of the road whistled and sang in the weird way that telephone wires do. Peabody didn't like the sound. It reminded him of the ray and he did not like thinking about the ray.

He hated it because it constituted a motive. He wanted it to be forgotten like the rest of the business. If O'Farrel had known about the ray... if Peabody had told him that during that short honeymoon he had explained the ray to her, shown her the model, elucidated the various technical points. If O'Farrel had known this...

Peabody could picture him, could almost bear the words accompanied by O'Farrel's cynically humorous smile; could see the sudden halt in the reckless walk up and down the room.

"So that's why she went," O'Farrel would have said. "The logical explanation, my Josiah, at last! There always is one, you know. So the little Russian aristo who was on the run from the Bolsheviks and who married our Josiah, disappeared after, immediately after, little Josiah had explained all about the ray to her. Oh, ho! Of course she couldn't have heard of that ray before she married Josiah, could she? You poor chump! Haven't you heard that no government in the history of the world had ever made such wonderful use of women's beauty for the acquisitions of other people's secrets as our Soviet friends. And little Josiah fell for it!"

But O'Farrel did not know. He knew nothing of the existence of the ray. Peabody wondered whether he should have told O'Farrel about Irma knowing and understanding about the ray. In spite of the cynical humour, O'Farrel's advice was often worth having. And he knew women too, slightly too well (so he said). Peabody asked himself what O'Farrel's advice would have been. Of course he would have jumped at the ray as being the motive for the whole thing.

Was it the motive? The question had burned in Peabody's brain for years. Once more he began to add his facts, for and against. Suppose they had heard of the invention, somehow. Then it was quite natural that they should try and obtain it by any means. But would the events have worked out exactly as they had.

They didn't know he was going to marry her. Besides, he, himself, did not know that the ray was usable, practical. He had heard nothing from the British Government who had had the whole thing put up to them years ago, and who had said that if experiments proved successful he would be required for further tests.

He had heard nothing at all, and inquiry, recent inquiry, had evoked the same answer. But it was a motive, a very logical motive.

Peabody bit into the mouthpiece of his pipe and walked on. He was soaked through, for the rain was teeming down now.

On the seaside the mist was less heavy. In front of him, a few yards away, almost opposite the bye-road to Salthaven, he could see the upper part of a house showing over the cliff edge. He realised that it must be the Turkish Café, the café which the man in plus-fours had explained was built on a gallery cut into the cliff face.

Peabody was almost relieved to think about it. He wanted to think about anything but the ray and Irma. He would go there and have tea. As this thought struck him he became aware that he was not alone on the road, for a few yards in front of him on the moor side, a tall round-shouldered figure was moving, a figure whose head was sunk forward so that the man must have been walking looking always about a foot in front of his own feet, slouching along with its hands sunk into the pockets of a dingy green overcoat that cleared the ground only by a few inches.

Diagonally opposite to Peabody, he moved along with a peculiar restlessness showing in his gait. The restlessness of a man who is keen to get somewhere and lacks the necessary strength to hurry. The soft brown hat, pulled over the brow, was dilapidated, and his boots looked like two squelchy lumps which dragged themselves along the road in a weird and jerky manner.

Together they approached the bye-road to Salthaven. Peabody seemed certain that the man in the green overcoat would turn up the road. He wondered why the man had not cut across the moor and saved himself the longer walk. Still, he might be going to Hetton. But Peabody illogically enough, was certain that Green Overcoat was not going to Hetton. He was certain that he would take the bye-road. Perhaps he was going to Sepach Farm, thought Peabody, and this line of thought reminded him again (for some unknown reason) of Plus-Fours and his childish smile and little chubby pipe.

Immediately following this idea came the thought that this man might be Truesmith. Peabody, impelled by some mysterious motive, quickened his steps and walked gradually across the road till he was a pace behind the man.

Green Overcoat, although he most have been aware of Peabody's proximity, took not the slightest notice.

Peabody spoke. "Excuse me," he said smiling as usual, "but does your name happen to be Truesmith?"

The man in the green overcoat stopped dead, and turned half round.

Peabody noticed the dark, ill-kept beard, the shaven face, and the eyes, dark rimmed, and cornered with the viscous fluid of premature senility, eyes which glittered. At the corner of the man's mouth, on the lip, there was a white particle. Peabody recognised it as a piece of dried sunflower seed. The man had been chewing sunflower seed—a Russian habit.

Peabody sensed immediately that the man was Russian, that the green overcoat which he was wearing was a Russian army coat, converted for civilian use. The man stood silently, his mouth working. Then he looked, at Peabody and deliberately, and with unmistakable venom, spat. Then he wiped his mouth with the back of his band, and, almost with care, replaced the hand in the tattered overcoat pocket.

"I am not Truesmit'," he said slowly and harshly. "No, I am not Truesmit', Captain Peabody."

He looked straight at Peabody's eyes. Then spat once more, turned on his heel and walked off. Peabody watched him turn up the Salthaven road. The man did not look back, but Peabody knew, somehow instinctively, that the Russian was going to stop at Sepach Farm. He found himself wondering how he knew this fact, but it was a certain thing, settled definitely in his mind, that the Russian would stop at the farm, and Peabody developed quite suddenly an idea to go after him and talk to him.

The man in plus-fours and his silly chatter, and this tattered, green-coated, devilish-eyed man had started something between them. They had drawn him into—something. Peabody wondered, rather vaguely, if his nerves were going a bit.

He stood quite still in the rain. He felt uncomfortable and unhappy. He disliked the afternoon, the mist, the lonely road—everything. He disliked the forced and cheery conversation of the man in Plus-Fours and his airy discussion of the Turkish Café, but much more he disliked this tall, shabby specimen with the burning eyes, this dirty ill-kept man who possessed some sort of pride and who spat so venomously and deliberately.

But the thing which perturbed Peabody most of all was the knowledge that this man, this Russian, knew his name. How did he know that he was Captain Peabody? Peabody had dropped the rank years before demobilisation. No one ever called him Captain.

He stood there trying to think clearly about the afternoon, trying to arrive at some conclusion, realising, as be did so, that there was no conclusion to be arrived at, but wanting all the time to go on after Green Overcoat, who had disappeared up the Salthaven bye-road, and who was jerking along somewhere on the other side of the mist.

He looked towards the sea. The mist had cleared still more. Opposite him on the cliff edge was a balustrade of stone running down with the steps which led to the gallery on which the Turkish Café stood. A sign swung in the wind on an iron pole by the side of the steps with the words "Turkish Café" painted on it.

Peabody fought down his desire to go on to Sepach Farm, and turning, abruptly walked towards the steps. Peabody, half way down the steps which led to the oaken door of the café, congratulating himself on having definitely renounced the idea of going after Green Overcoat and thoroughly decided that he would forget both that gentleman and Plus-Fours, stopped suddenly.

He found himself confronted with something else which required explanation, and he was sick of trying to elucidate things.

There were half a dozen steps and a small entrance porch between him and the café door, and lying half over the bottom step and half in the entrance porch was a black georgette gown. The diamante buckle at the waist glimmered a little as Peabody, walking carefully, descended the remaining stairs.

He picked it up. It had been lying there for some time, for it was soaked with rain. Peabody wondered how it had got there, and why somebody had not picked it up. He stood before the door of the café, which was closed, holding the gown in his left hand, and biting his pipe stem. He imagined the humorous picture he would present, entering the café with a gown in his hand.

He stood listening. A sound came from within the café. After a moment Peabody recognised it. It was the sound of a woman sobbing. Hoarse, racking sobs. He felt terribly uncomfortable.

He dropped the gown and began to ascend the steps leading to the cliff road. He was scared. He had no desire to enter the café. He was not interested in any woman who had something to cry about, but as he walked up the stairs he had that horrible feeling of being trapped.

Wherever he went he would walk into something. If he went up the Salthaven road there was the possibility of meeting the Russian. Peabody was now thoroughly decided that he did not want to see the man in the green overcoat any more. On the other hand, if he took the road back to Stranover he felt certain that he would meet the man in plus-fours with his airy smile and (so they seemed) ominous questions; behind him, in the café, the place he had selected as a means of forgetting or escaping from the other two, something even more unpleasant was afoot.

Undecided, be descended the stairs again and gave the door a push. It was locked. That decided him. Every man, even a man of the Peabody stamp, is a little curious. He wanted to know what the georgette gown was doing, lying there possessing, he thought, some weird animation of its own, lying in front of this locked door behind which some woman was sobbing.

Peabody stepped back and then flung his shoulder against the door. The lock was rotten; with a splintering of wood the door crashed open. A heavy perfume came to Peabody's nostrils. He stood, transfixed, gazing at the weird sight which met his eyes.

A LONG room confronted him, and a not unattractive perfume greeted his nostrils. His eyes had not accustomed themselves to the gloom of the place when he saw something move.

A woman got up from the armchair in which she had been huddled, at the far end of the café. She turned and passed through the curtains which shadowed the other end so quickly that Peabody was unable to realise anything about her except that she was tall, and that she was wrapped in a gold kimono, which she held closely about her.

The hangings fell to behind her, and he stood wondering, sniffing the heavy perfume which abounded in the place and gazing about him.

His first thought was one of amazement that any sane person should construct and furnish in such outlandish fashion what he had supposed to be an ordinary seaside teashop. The hangings round the walls were of silk and velvet. The lamps, shaded, and throwing a dim and mysterious light about the place—a light which seemed to make more for grotesque shadows than illumination, were of Turkish design and, he thought, valuable. The floor, which was of stained oak was covered with thick, expensive rugs. In a corner, furthest from him, burned a brass brazier on a tripod. It was burning a perfume and the wraith of smoke which floated up from it brought back some old memory to Peabody. At the far end of the café a heavy velvet curtain covered the entire width of the wall, but on the right-hand side he could discern the shape of a circular flight of stairs leading up, he supposed, to the one floor above—the floor which would be above cliff-top level.

And it was up this flight of stairs that the woman, the train of her gold kimono trailing after her like a snake, had disappeared.

It never occurred to him to go after her, to question her. To Peabody, the satisfaction of his elementary sense of duty was enough. He had heard her sobbing. He had entered with the idea of finding out what was the matter, and of asking what the black georgette gown was doing lying out there in the rain. Well, she had seen him enter and she had gone. Obviously she did not want to talk to him. That was that. Peabody thought now, having regard to the rather weird atmosphere of the café, that he would prefer another encounter with Green Overcoat or Plus-Fours to a conversation with this lady in the kimono who had cause to sob so bitterly.

He turned and walked out of the café, closing the door carefully after him. Outside, he stood for a moment in the porch considering. Before him, on the ground where he had thrown it, lay the black georgette gown getting very adequately spoiled in the rain.

Peabody, leaning against the porch and refilling his pipe, took himself to task and considered the necessity of getting himself well in hand once more. He came to the conclusion that he was an old woman suffering from a bad attack of nerves. He had encountered three people on an afternoon walk—rather strange people, he granted, but then all people were, more or less, strange. It was quite on the cards that the man in plus-fours was one of those peculiarly garrulous people who will stop and talk to anybody, anywhere; one of those people who love the sound of their own voices. The man in the green overcoat, well, he was probably some bad-tempered tramp, who knew his name through some coincidence—he might have served as interpreter attached to one of the British units in Russia, or anything like that. The world was very small, and there was probably some quite reasonable explanation for the black gown lying in the rain, and for the woman crying in the café. After all, women often cried, reasoned Peabody, and very often, he had heard (for he knew little about them) without any adequate reason at all.

It was all a lot of nonsense, he told himself as he began to mount the steps leading to the road above. Half way up he asked himself exactly where he was going. He had a decided disinclination to return to Stranover. He thought he would go on to Sepach Farm. Of course, the Russian would not be there. This, said Peabody to himself, was another of the silly ideas which he had developed during the afternoon. Why should the Russian be going to the farm? Subconsciously, Peabody's idea was to go and see if the Russian was there, but at the moment he would not admit this to himself.

At the top of the steps he stood looking about him and listening. There was no one in sight. The mist had blown away in front of him and he could see some little way up the Salthaven road. To his left, towards Stranover, the mist was still thick. To his right the bleak rain-lashed moorland lying towards Hetton looked ominous. The very sound of the pattering rain on the asphalt road was distasteful. Peabody thought that his surroundings looked like the sort of place where something not very nice could easily happen. The thought disturbed him and he put it quickly out of his mind.

He turned and looked down at the café door. It looked just as it had looked before, but the black gown lying there before it seemed strangely incongruous. Peabody had a half humorous desire to run down the steps, pick up the gown, fold it, and lay it carefully in a corner of the porch out of the rain.

He lit his pipe, shielding the match carefully with his hands, for the wind was high. Then he began to walk across the road. Halfway across the wind dropped for a moment and the rain descended in torrents. Peabody was getting fed up with the rain. His clothes were heavy with it. He crossed the road quickly and stood beneath a tree which afforded a little shelter and which stood in the angle formed by the Salthaven and Stranover roads. He sat down on the gnarled and clawlike root of the tree and puffed at his pipe.

He was deciding whether he should return to the café and shelter there, till the rain ceased—he expected the woman had finished crying by now, or whether he should walk up to the farm and shelter there. It had to be one of the two places. Peabody remembered with a slight distaste than the man in plus-fours had pointed this fact out to him. Then suddenly he ceased thinking.

Somewhere in the vicinity someone was whistling. Peabody listened carefully. Soon the whistling became more distinct. He could recognise the tune—"Annie Laurie"—and the whistler was evidently not in the least perturbed about the weather. He whistled slowly, giving each note its full value, and occasionally whistling a bit of the song several times in succession before continuing with the rest of it. Then, when he had got right through the chorus he would commence the process over again with a maddening sort of regularity.

And he was approaching. Peabody thought that he would emerge from the mist on the Stranover road, but he was wrong. The man came out from the corner directly opposite Peabody, evidently from the moor, and as he leapt the little ditch which bounded the road, Peabody recognised him—it was the man in plus-fours.

He was as cheerful as ever, and, with his round cheeks blown out to their fullest extent with his whistling he looked quite juvenile. His right hand was in his trouser pocket and in his left hand was a little chubby pipe. He stood for a moment looking towards the mist on the Stranover road, still whistling.

Suddenly he stopped—right in the middle of a bar—took his right hand out of his trouser pocket and moved it round to his right hip-pocket, at the same time putting the little chubby pipe into his left-hand jacket pocket.

Then he stood quite still with his head on one side. He seemed to have come to some decision.

He walked slowly across the road until he stood at the top of the steps leading to the café. He stood there for a moment, peering over. Peabody wondered if he had seen the black georgette gown, and if he, too, were curious about it. It seemed to have a strange effect on the man in plus-fours, for he stepped back a couple of paces, slipped his hand to his hip pocket, produced a medium-sized automatic pistol and a cartridge clip, and whistling again—this time quite softly, Peabody could just hear him—proceeded to load the clip into the pistol. This done, he replaced the automatic in his jacket pocket and, keeping his hand in the pocket, he moved slowly down the steps towards the Turkish Café door. He had evidently not seen Peabody, or, if he had, he had not taken the slightest notice of that gentleman.

Peabody got up and stood considering whether he should go on up to Sepach Farm or whether he should return to the café and see what the man in plus-fours who kept his hand so carefully on his automatic was doing. His thoughts were disturbed, however, by the sound of a shot.

Peabody's head cocked slightly to one side. The sound seemed to have come from the direction of Sepach Farm. He had just conceived this thought when he heard another shot. He stepped round the tree and looked towards the farm. It looked just the same. Turning round, he saw Plus-Fours standing at the top of the café steps looking towards the farm, still whistling quietly to himself. His right hand was still in his jacket pocket, and in his left hand he held the sodden black georgette gown. Peabody wondered why he had picked the gown up. From his position on the far side of the tree Plus-Fours could not see him. Peabody felt glad about this too.

Plus-Fours stood at the top of the steps for quite two minutes, then he turned and descended, once more disappearing from view.

Peabody stepped out from beneath the tree and walked rapidly up the Salthaven road, towards Sepach Farm. He was feeling sick of mysteries, and the idea of a practical move appealed to him. He had made up his mind to walk up the Salthaven road and, in passing, to take a look at the farm (what good he would do by "taking a look" at the farm never occurred to him), then cut across the moor and get to Stranover as quickly as possible and take a hot bath.

Probably the shots were occasioned by someone shooting on the moor. He supposed that people did shoot in the midst of rainstorms sometimes. Here again Peabody was deliberately deluding himself. It was practically certain that the shots had come from the farm, and Peabody had experience enough of shooting to know the difference between the sound of a sporting gun fired in the open and the very different noise made by a heavy-calibre pistol.

As he approached the farm he observed someone coming towards him. This individual was a tall, good-looking young man, dressed in a tweed suit which was well cut and nearly new. As he came closer Peabody saw that his face was fine and intellectual—the face of an artist—and that his hands were beautifully-shaped and white.

Peabody called out, "Good afternoon. Did you hear those two shots fired just now?"

The young man touched his cap—another foreigner Peabody surmised—and when the young man spoke he knew that he was correct.

"I did not... I heard no shots," said the young man smilingly. "It must have been your imagination."

"It wasn't," said Peabody, feeling, for some reason, quite hostile to the fellow. "I don't imagine things like that!"

"Don't you," said the young man, quite cheerfully. "Well, that that's isn't it? Good afternoon." He walked on down the road.

Russian again, thought Peabody. He was angry with himself for having spoken to the fellow, who had been as politely rude as possible.

Peabody stood looking after him. When he reached the crossroads he turned left, and went towards Hetton. The mist was fairly thick on that side and it soon swallowed up the young man in the tweeds.

At this moment, simultaneously with the disappearance of the young Russian, Plus-Fours appeared at the top of the café steps. He was smoking his pipe and had his hands in his pockets as usual. He stood for a moment looking about him and then walked off rapidly towards Stranover.

Peabody wondered what he had been doing in the Turkish Café, and if he had succeeded in finding out what was troubling the lady in the gold kimono who had occasion to sob so bitterly. Plus-Fours was what Peabody would have described as a "pretty cool card." Nothing seemed to perturb him very much, even when he had occasion to load automatic pistols. There was no doubt that Plus-Fours was up to something, was carrying out some definite idea, but what this idea had to do with the woman in the café and the man in the green overcoat, Peabody could not guess.

THE rain had abated somewhat by now and was drizzling steadily down as if saving its forces for another torrential downpour in a little while. Peabody, walking towards the farm, quickened his steps. Definite ideas were beginning to shape in his head with regard to the young Russian in tweeds. Coming down the Salthaven road he could only have been walking from Salthaven Junction six miles away, or from Sepach Farm. Obviously he had not walked from the junction, for his clothes were hardly wet. Therefore it seemed certain that he had been standing up for quite some considerable time in the vicinity of the farm, and must have heard the shots. What reason could he have for denying this?

A dazzling flash of lightning appeared just in front of Peabody, then a terrific crash of thunder, followed by the deluge of rain which he had been expecting. He increased his pace, and, half running, passed through the wooden gate of the farm, crossed the overgrown and weed-filled courtyard, and took shelter under the overhanging ledge of the first-storey window. The same ledge that Irma and he had used.

He looked at his watch. It was five o'clock and the evening shadows were falling fast. Lights were glimmering in Hetton Village, and as Peabody's eyes drew across he saw a bright spot appear in the upper window of the Turkish Café—the one window which appeared above the cliff edge. So someone was still there. Peabody imagined that the lady in the kimono, having got over her particular trouble, was carefully powdering her nose and removing any traces of the sorrow of the earlier afternoon.

He felt hot, and removing his cap, wiped his brow. Raindrops, collecting on the ledge above him, fell coolingly on his head. Rather a pleasurable sensation, thought Peabody.

He knocked out his pipe, refilled, and lit it, then stood, leaning against, the wall of the farm, smiling at himself. There was no doubt that his nerves were out of condition, and that he had exaggerated several unimportant events and people into a first-class mystery. He considered that after a hot bath and some food he would view the whole thing from a proper perspective and probably smile at himself for his qualms. There was no doubt, too, that this wandering about the roads and moorland had got to stop. It wasn't doing any good, but only opening old wounds, resuscitating old thoughts and memories which were better buried and forgotten. Kenkins thought him a fool, and Kenkins, even if he were a materialist was probably right. O'Farrel probably thought the same thing.

Peabody wondered what the enterprising O'Farrel would have made of the events of the afternoon, what logical story he would have strung between the facts which had occurred. Peabody was about to put on his cap, when suddenly he stopped and considered. For the last few moments the raindrops from the ledge above him had been falling onto his head with almost monotonous regularity. He was donning his cap because he was tired of the sensation, which (the thought flashed through his mind) was reminiscent of the Chinese water torture, but he stopped in the action of replacing his cap because he thought that something very peculiar was happening—the rain falling on to his head was becoming warmer and warmer. He stood perfectly still. He thought that his imagination was absolutely running away with him. He was a case for a nerve specialist—no doubt about this.

Another drop fell onto his head. It was quite a warm drop, he thought. He pulled out his handkerchief, ran it over his hair and looked at it. A nasty stiff feeling ran over the skin of his face and neck. He jerked himself upright. His handkerchief was red—red with blood.

He stepped out into the rain and looked above him at the ledge. He felt quite sick. He knew now that his nerves were not at fault. The events of the afternoon were only the beginning—things were really going to happen now. He knew what the shots had meant. The sound had come from Sepach Farm—he had been right there, and he had been standing under the window-ledge and somebody's blood had been dripping onto his head with horrible regularity, taking the place of the grateful rain.

Peabody had a desire to run; a desire to place as much space between himself, this farm, and the weird people who seemed to be hanging about the neighbourhood as possible. Then his unemotional self reasserted itself. He must know what it was all about. He must enter the farm and find out exactly what had happened.

He put the handkerchief into his pocket. Put on his cap and walked round to the dilapidated front door. It was half closed. Peabody kicked it open and entered.

HE found himself in a small and irregularly-shaped hall. A door immediately to his left opened into a ground-floor room running the entire length of the house.

He glanced quickly into this room and then began to mount the staircase which stood on the right-hand side of the doorway. It was a rickety and dusty stairway, and the recent muddy footmarks on the bare boards told Peabody that someone had used it since the rainstorm.

He had got over his feeling of sickness. The matter had now taken a turn which required practical effort, and doing things appealed much more to Peabody than thinking about them. As he mounted the stairs he was preparing himself for a sight, which, he told himself, would not be too pleasant. He walked up the stairs slowly, and, at the top, stood for an instant, stamping some of the rain from his shoes.

A passage ran from the top of the stairs to the back of the house. It was a long passage ending, apparently, in a dead wall. There were only two doors leading off the passage, exactly opposite each other. The one on the right, he knew, would be the door of the first-storey room, the room with the wide window ledge, under which he had been standing outside, the room in which he knew he should find something not very nice. He walked down the passage. The silence of the place seemed to Peabody to possess some peculiar quality. A heavy atmosphere seemed to pervade the place. He wished that the injured man would groan or do something to break the silence.

He was about to turn into the right hand room when something prompted him to glance into the room on the left. He did so, and received a distinct shock, for lying at full length in the middle of the empty room stretched out, with his long, thin, and dirty fingers clutching at the floor underneath him, with his head and face turned towards Peabody, and the piece of sunflower seed still sticking to his lip, lay the man in the green overcoat. Peabody, his first shock over, forgot for the moment about the other business, forgot the blood dripping from the window ledge in the other room, and stood looking at the Russian as he lay there, still malevolent, his tattered olive-green overcoat disarranged and caught about his shabby legs.

The explanation was fairly obvious, for the whole back of the overcoat was covered with a dark red blotch. Peabody stepped nearer and looked down at it. The man in the green overcoat had been shot through the back with a heavy calibre pistol Peabody thought. So that was the explanation of the shot—the first shot. Peabody realised that the explanation of the second shot would be in the opposite room. Just beyond the fingers of the Russian's right hand, lying where it had fallen from the nerveless grasp, was a Mauser automatic pistol, and just beyond the pistol the blood stains started.

He walked quickly across the passage and into the opposite room. The window was half open, and propped against it, half sitting on the window ledge, with a queer sort of smile playing about a mouth which was already beginning to sag, was a man of about 35 years of age. As Peabody entered the room he began to slip downwards from the ledge, and, as Peabody sprang forward to check his fall, slid with a bump to the floor.

He was alive and breathing heavily and hoarsely. Peabody, glad to do something, opened the fawn raincoat which was buttoned about the man. Underneath, the coat and waistcoat of brown tweed were soaked with blood. He also, had been shot clean through the body for Peabody could see that the side of the window against which his back had rested was bloodstained.

It came to Peabody that the Russian in the other room had done this. Had he shot this man through the back as he had turned to leave the room? But then who had shot the Russian? Peabody remembered that there had been a pause of perhaps half a minute between the shots. Who had been shot first, the Russian or this man? The man lay quietly on the floor, looking at the ceiling. Occasionally his eyelids flickered. His face was strikingly handsome—an experienced face, Peabody thought, with a firm jaw and well-set grey eyes which were already slightly touched by the film of death.

The thought of dashing out and endeavouring to secure help came to Peabody to be immediately dismissed. The man on the floor was beyond help, and to leave him would be foolish. He might manage to say something—something which might throw some light on the grim business which had taken place at Sepach Farm; for by this time Peabody knew that he was in the business, whatever it was, and he was part of it, and that fate had thrown these things across his path for the sole purpose of drawing him in, and making him play his little part.

With a great effort the dying man slowly turned his head towards Peabody, the queer half-smile still showing about his mouth. That he wanted to say something was obvious for his lips were moving although no sound came from them. Peabody, bending over him, strove vainly to get some idea, by the lip movements, of what the man wanted to say.

Presently his eyes closed, and Peabody thought that it was all over, but after a moment they opened again, and flickered weakly, closed, opened and flickered again. Suddenly Peabody realised, with a start that the man was signalling with his eyes, flickering the "calling up" signal in the Morse code;

He tapped the "answer" signal on the floor with his pipe-stem, the dots and dashes taking him back through the years to the war.

R... D...—tapped Peabody—R... D...

The dying man's eyelids flickered slowly, and Peabody prayed that he would have sufficient strength to send the message.

s-t-e-i-t-l-i-n-stop, said the slow moving eyelids, i-r-i-e-t-o-f-f-stop... 2-c-h-2-v-I-r-c-h-l-o-r-7-3-7-stop.

A convulsive shudder shook the signaller and his eyes closed, for a moment the humorous smile seemed to Peabody to deepen, then it faded away. The man was dead.

But in spite of the death which was in Sepach Farm, Peabody stood, his eyes wide with something which was nearly fear, writing down on a scrap of paper the message which had been so strangely sent, "steitlin, irietoff" .... these seemed to him to be names, surnames, and they meant nothing to him, but it was the last thing, the formula, which shook him. For "2ch2/VIR/chlor/737" was the formula which stood for the ray—Peabody's Ray, the ray which spelt instant and terrible death, and which was known to only two men!

HE stood looking at the piece of paper. Back to him came the droning of the telegraph wires of the earlier afternoon. That had reminded him of the ray, and that had reminded him of Irma. But even she did not know the formula, the formula by which the ray was known to Peabody and the one War Office expert. How then did this dead man come to be in possession of it?

One after another the incidents of the afternoon flashed through Peabody's mind. The meeting with the man in plus-fours, the meeting with the Russian, the man who lay dead in the other room, still malevolent, clawing at the floor, and who had known his name, the meeting with the young Russian whose cool insolence had annoyed him, the two shots, and then this!

And, worst of all, at the back of his mind lurked the motive. Was this the motive for Irma's disappearance? Was she responsible for this? Had the information which he had so foolishly imparted to her resulted in this double murder and the knowledge by at least one of the dead men of a formula which, under certain circumstances, might easily shatter the peace of the world?

And was this knowledge confined to one man? If this dead man lying before him had known it, why not others?

The vicious circle of thoughts chased round in Peabody's brain—Irma, the ray, and these dead men. And what was to be the next move?

Obviously, the police. They must be informed, and at once. But here again Peabody found himself thinking something without any logical reason for the thought. He found himself possessed of a decided disinclination to go to the police immediately.

The sequence of events during the afternoon and evening were beginning to exercise a peculiar fascination on Peabody. All these people were connected in some way with the crimes and each other. The man in plus-fours, the young Russian who had walked off so airily towards Hetton, the woman in the gold kimono. Each one of them, Peabody thought, had contributed in some way to this particular climax.

Peabody became practical and moved forward towards the dead man. Then he sank on one knee and began a systematic search of the body. He searched thoroughly, even half undressing the body in his efforts to find something. There was nothing at all—nothing; not even a laundry mark, and the tabs bearing the maker's name had been carefully removed from overcoat, suit, hat and underclothes.

He re-arranged the clothing, straightened the body out, and stood regarding it. There was something quite attractive about what remained of the stranger in the brown tweed suit. The half-humorous smile still seemed to play about the firm mouth. Death, thought Peabody, had little terror for this man. It had been, it seemed to him, something which was to be expected, a move in the game, something which must be regarded as a semi-humorous possibility, and when it had arrived, his only thought had been to signal a few words, essential words, which would enable somebody else to take up the game where he had been forced to drop it.

And the game had to be taken up.

Peabody shuddered a little as he thought of the Q-Ray formula being known to all sorts of weird people, who would not scruple to use it for their own immediate gain. The Russian in the opposite room for instance. This thought sent Peabody quickly across the passage into the room on the other side. He stood looking down at the man in the green overcoat as he lay, face pressed sideways on the floor, still malevolent, still threatening. Eventually he turned the body over and examined the clothing carefully. As in the other case there was no clue. In one pocket of the green overcoat were a handful of sunflower seeds, and in the other an automatic clip, an additional one, evidently. Peabody remembered how the man in the green overcoat had thrust back his hand into his overcoat pocket when he had spoken to him on the Stranover road earlier in the afternoon. Possibly, thought Peabody, the Russian had been expecting to meet someone who might merit the attention of his automatic.

It was now nearly dark and the last of the evening's light was casting grotesque shadows about the floors and walls of this house of death. Peabody dropped the automatic to the floor and stood for a moment regarding it. The sight of it reminded him once more of the man in plus-fours—that strange person who hung about country roads, who stood whistling a song over and over again, and who, for some reason best known to himself, carried an automatic pistol too. An idea came to Peabody; he left the room and walked quickly across the passage and into the other room. Stepping gingerly over the body of the other man, he peered out of the window into the shadows of the courtyard, and across to the tree-bordered road beyond. On the other side of the road, beneath a tree, was a tiny light. A firefly, thought Peabody. Then, straining his eyes into the darkness, he managed to make out the silhouetted figure beneath the tree. It was as he had thought. Lounging on the other side of the road, smoking his little chubby pipe, was the man in plus-fours.

Peabody, drawing back from the window, and stepping gingerly across the body once more, stood in the middle of the room and thought.

Obviously he must go and find a policeman somewhere and tell him. He visualised himself telling some country policeman the events of the afternoon, leading up to the grand climax of the double murder. He visualised the arm of the law with an open notebook and an open mouth wondering exactly where he was to start making notes.

Having come to this conclusion Peabody filled his pipe, lit it and, with a last look at the dead man, walked out into the passage and prepared to descend the stairs.

Outside the wind was positively howling, and whenever it stopped for a moment a great gust of rain descended, beating upon the roof of the farm and splattering noisily into the puddles in the courtyard. Almost at the bottom of the stairs he trod on something—something hard which, as he put his weight on it, gave. He stooped and picked it up, looked at it for a moment, and then realised what it was. It was a diamante buckle, and it was the fellow to the one which he had seen upon the black georgette gown, which, unless someone had moved it, was still lying in the rain at the bottom of the steps leading down to the Turkish Café. Peabody wondered how it had come to the farm. It was funny how all these mysterious things seemed to be associated with each other. Peabody found himself wishing that the buckle could talk. He imagined that it might have a rather peculiar story to tell.

Then he slipped it into his pocket, and continued towards the door.

Arrived, he stood in the doorway straining his eyes across the courtyard. He could make out the rickety fence quite plainly, and, on the other side of the road he could see the dim spot of light which was Plus-Four's pipe, glowing in the darkness beneath the clump of trees.

Then, as he was about to step into the courtyard, cross the space between himself and Plus-Fours, and tackle that gentleman, something else happened. A figure came from out of the darkness from the direction of the Turkish Café, and before Peabody could quite see who it was he sensed that it was the woman—the woman in the gold kimono! She came out of the darkness and approached the broken wooden gate which led into the farm courtyard. Peabody found himself remembering something about the way she moved.

He stepped out of the doorway and took a couple of steps towards the gate. She had entered the gate when, looking up, she saw him, and he heard her sob.

Peabody, standing there in the rain, felt quite sick. He took an involuntary step towards her, then stopped, hesitating, not knowing what to do; and, while he stood, she turned and half walked, half ran to the gate, through it and down the road, back towards the Turkish Café.

Peabody turned back to the door of Sepach Farm and sat down on the step, his head between his hands. For the whole of his little world—the little world which he had built up during the last few weary years—had fallen in. He felt rather like a child; he did not know what to think, what to do.

For the woman in the gold kimono was Irma—his wife!

IT was some minutes before Peabody was able to regain control of his feelings. Then he got up and walked slowly towards the gate, passed through it, and stood in the road, uncertain what to do.

His first impulse had been to dash off down the road to overtake Irma, and to ask her for an explanation of this amazing business; but his logical mind, functioning even in this time of distress, told him that she was not likely to tell him the truth. The realisation that his wife was mixed up in this business; that there was some connection between her and the two murders at the farm, stung Peabody. One idea was predominant; he must not go to the police until he had found out what was the connecting link between Irma and the deaths, for although he would not admit this to himself, Peabody was trying to make himself believe that there was still a chance that his wife was innocent of complicity in the crimes. He was trying to give himself time to protect her.

An idea suddenly came to him. There was little likelihood of anyone visiting Sepach Farm before next day. If he could cross country to Salthaven he could catch the nine o'clock express and be in London by 11 that night. He had made up his mind that he would go to O'Farrel, that he would tell him the whole story, disguising one fact only, the fact that the woman in the gold kimono was his, Peabody's, wife. Peabody felt sure that he could rely on O'Farrel's assistance; he felt certain that the romantic mind of Etienne would immediately seize on the tangled skein of the afternoon's happenings, and unravel it. Peabody thought that it would be possible for O'Farrel and himself to return that night to Sepach Farm, hide the bodies temporarily, and then he, Peabody, would go to the Turkish Café, and would elicit something from Irma which would enable him to come to some definite conclusion as to her guilt or otherwise.

Having come to this conclusion, Peabody felt better. Looking down the road towards the sea, he saw a light glimmer above the cliff edge. This light he knew would be in one of the top rooms of the Turkish Café. Irma had got back, but would she stay there, or would she, knowing that he was in the neighbourhood, try to make her escape? Once more he dismissed the idea of going to the Turkish Café, and, turning on his heel, strode up the road, walking quickly.

Half a mile up the road he branched across country, walked over the wet moorland, brushing through the wet gorse-bushes, occasionally tearing his clothes, which were again thoroughly wet. He was beginning to feel a little better. He was, at least, doing something definite. He realised now that some unkind fate had planned a sequence of mysterious events that had drawn him into a net from which he must somehow cut himself clear.

Ten minutes after Peabody had left the farm the man in

plus-fours, who had been waiting patiently, nibbling his pipe-stem

as usual, on the opposite side of the road, crossed it,

walked across the farm courtyard, and entered the farm. He was

still whistling "Annie Laurie" under his breath. Once in the

farm he ascended the stairs, and, walking into the room on the

left of the passage, stood looking at the body of the Russian as

it lay on the floor. His face betrayed no sign of emotion

whatever.

After a few minutes' scrutiny he crossed the passage and walked into the other room, and looked for some minutes at the body of the man in the fawn raincoat.

After a while he descended the stairs, walked round to the back of the farm and, pushing his way, walked out on to the moorland. He stopped by a clump of trees and whistled. A few minutes later a figure emerged from the bracken near by.

"Good evening," said the man in plus-fours. "Things aren't so good."

The other man, a broad-shouldered individual who looked as though he might have been a sailor, scratched his ear reflectively.

"Anybody hurt?" he asked. "There was a couple of shots somewhere round here about two hours ago. I thought of going into the farm."

"You don't have to think," interrupted the man in plus-fours. "I will do all the thinking that is required, and some thinking has got to be done pretty quickly. At the present moment Sepach Farm, in addition to its other advantages, is acting as a temporary morgue. The thing is how I am to keep the local police from sticking their noses into something that doesn't concern them. There is something else, too. There's a man, a rather nice-looking man, strangely enough, hanging about this place. I met him on the Stranover road this afternoon. He went into the farm; he has just left there, and, if I know anything, is cutting across country to catch the nine o'clock from Salthaven. This fellow perturbs me; I don't know who he is, or what he wants. He's a nuisance."

The man in plus-fours refilled his pipe and lit it. After some moments' reflection he spoke again.

"You had better get back to Stranover, Stevens," he said. "There's nothing else can be done to-night, but before you go, push the motor-bike on to the road. I am going to catch that train from Salthaven, too. You had better stand by at Stranover until I telephone you."

The man went off, and reappeared after a moment, pushing a motor-cycle. Five minutes afterwards the man in plus-fours rode off rapidly through the darkness, along the Salthaven road, and Stevens, shaking himself like a wet dog—for he had spent the whole afternoon on the moor—tramped on on his long walk back to Stranover.

As his figure disappeared along the cliff road, another figure appeared from the direction of Hetton village. It walked quickly to the top of the flight of steps which led to the Turkish Café.

After a moment's hesitation the young man ran down the steps, and knocked on the door of the Turkish Café. The door opened, and, outlined in the doorway, the woman in the gold kimono gazed at the face of the man who stood before her. Then, with a little cry, she collapsed in a dead faint.

The young man who was none other than the second Russian—the man who had informed Peabody that he had heard no shots at the farm—produced a small toothpick from his pocket, and stood picking his teeth, calmly regarding the prone figure on the floor before him. After a moment, he stepped over the woman, dragged her into the café, shut and locked the door and sat down. Presently she stirred; her eyes opened.

The young man smiled sardonically, and lit a cigarette. "Well, Madame Steitlin," he said in Russian, "what have you to say?"

THE nine o'clock train was just about to pull out of Salthaven station, and Peabody, alone in his carriage, was congratulating himself on the fact that, at least, he would have time and opportunity to think. He was not allowed to think for long, however, for at the last moment the carriage door opened, and the man in plus-fours jumped in. He was still looking quite pleased with himself, and there was still a raindrop perched perilously on the end of his nose.

He puffed vigorously at his pipe, and sat down in the opposite corner of the carriage, regarding with great interest the photographs on the other side of the carriage.

Peabody recovered from his surprise at seeing this mysterious individual, once more made up his mind to come to a complete understanding with him.

"I'd like a few words with you," he said, abruptly. "I don't know who you are or what you are, but it seems to me that you have spent the greater part of this afternoon and evening in following me about. When you first spoke to me this afternoon I thought you were just a chatterbox; afterwards there seemed to be rather more behind what you said than I thought at the time. There has been some pretty weird business going on in the vicinity of Sepach Farm and I believe you've got something to do with it. Incidentally, I may as well tell you that I'm going to make it my business to see that the police are informed of what has happened this afternoon."

The man in plus-fours blew a perfect smoke-ring across the carriage.

"Well, of course, you know best," he said gently, "but, do you know, I've always found that it's an awfully good thing not to interfere in matters which don't concern one. I might as well say that I don't know what you were doing hanging about the Stranover road this afternoon, but I would not think of saying such a thing, for the very simple reason that it isn't my business. Live and let live, is what I say."

"I've no doubt," said Peabody, "that this is a case of live, and let not live. There has been murder done this afternoon; somebody is responsible; for all I know it may be you."

"Exactly," said the man in plus-fours, blandly. "It's pretty obvious that people don't get murdered unless somebody's done it. But, by the way, where has this murder taken place?"

Peabody looked straight into the grey eyes of the man in the plus-fours.

"There has been murder at Sepach Farm," he said, "and you know it."

"I don't," said the man in plus-fours "and if there's been a murder at Sepach Farm what have you done with the body?"

Peabody sat back and gasped.

"What do you mean?" he asked.

"Well," said the man in plus-fours, "when you were in the farm, or, rather, when you were just leaving it, you know, when that weird woman in the gold kimono came up the road, I was trying to light my pipe under the trees on the opposite side of the farm. I could not do it because of the wind, so after you left the farm I went in just to light my pipe, you know, and I looked all over the place, and I could not see anybody. Still, you never know, perhaps somebody moved them."

"I see," said Peabody, "I said that a murder had been committed, and yet you, who have seen no bodies, refer to 'them.' So you did see the two bodies at Sepach Farm? I believe..."

The man in plus-fours leaned over towards Peabody. His jaw had set in quite a determined manner, and his eyes were very hard.

"Now, look here," he said, "let's finish with this nonsense. Whatever you have seen, or whatever you have heard this afternoon and this evening, if you value your own skin, I advise you to keep it to yourself. In other words, mind your own business. What has happened at Sepach Farm has got nothing to do with you. As a matter of fact, I don't know why you've been hanging about the place, neither do I care, but I tell you this, and I mean it. You say you are going to the police—all right! Go to them, tell them your story about Sepach Farm, tell them your story about the shots and bodies! I tell you they won't believe you. They will tell you that you are mad; that you are suffering from hallucinations. Try it, and see. In the meantime, take a tip from me and keep away from Sepach Farm. It never was a very healthy place if the tales they tell in the neighbourhood are true, and it's certainly not likely to be a health resort now."

And, with these remarks, the man in plus-fours got up, put on his cap, knocked out the little chubby pipe, and walked down the corridor of the train towards the dining-car.

Peabody, knowing that there would be no meal served on the train at this hour, wondered, why he had gone, but, presently, glancing down the corridor into the dining-car, he saw the man in plus-fours, sound asleep, a beneficent smile on his countenance, at peace with all the world.

Peabody, in spite, of all his suspicions, had to admit that this weird individual certainly did not look like a murderer.

He leaned back in his seat, trying vainly to make some sense out of the jumble of weird events which had transpired during the day. He was terribly worried, and the thought of Irma, recurring every two or three minutes, almost drove him mad. It was with a sigh of relief that he saw the lights of Victoria Station come into view.

Arrived, he dismissed everything from his mind except the story he was to tell O'Farrel. He would tell him nearly everything: that Irma, when she had left him originally, knew the secret of the ray; but he would not tell O'Farrel that the woman in the gold kimono was Irma. For some reason which he could not explain, he wanted to keep this knowledge to himself. He could bear that O'Farrel should think that Irma had stolen the secret of the ray, but he could not bear that Irma should be suspected of the murders at Sepach Farm, although deep inside, Peabody himself thought that she had played some part in the double crime.

O'FARREL, clad in a brilliant crępe-de-chine dressing gown, his feet poised on the end of his writing desk, lay back in his chair, and listened with rapt attention to the story which Peabody told.

Then he selected a cigarette from the box on the table, inserted it in a long holder, and smoked for some minutes.

"All very interesting," he said eventually, jumping up from his chair and walking up and down the room, "but may I ask this? Why do you consider that your wife has anything to do with this business? You say that, before she left you, years ago, you had told her the secret of this ray, and the fact that this unfortunate individual signalled to you the formula doesn't necessarily mean that he obtained it from her. It may have been stolen from somewhere else."

Peabody realised instantly that O'Farrel had put his finger on the one weak spot in the story. Had he told O'Farrel that the woman in the gold kimono was his wife, the connection between her and the knowledge of the ray formula on the part of the murdered man at Sepach Farm would have been obvious; but he said nothing.

O'Farrel regarded Peabody intently for a moment; then he continued: "Beyond that, the whole thing is rather interesting. Briefly, I take it your story is this: You are walking along a road and are accosted by a stranger in plus-fours, who asks you a lot of ridiculous questions. Further along the road you meet another stranger, a Russian, with a limp. By some means or other he knows your name. Further on you find a black georgette gown lying in the rain in front of a mysterious café, in which some enterprising lady, dressed in a gold kimono, is having what is usually described as a 'good cry.' A little later—on your way to the farm—you pass a young foreigner, probably a Russian, you think. His clothes are quite dry, which would seem to indicate that he had been standing up at the farm; but he says that he has heard no shots,-although you say he must have heard them. Add to this a couple of corpses on the first floor, and our plump friend in plus-fours hanging round generally, and it would seem that we have the makings of a very fine story."

O'Farrel blew a smoke-ring into the air, and watched it sail across the room.

"There is only one thing that I am certain about," he went on continuing his restless pacing. "I think I can elucidate the mystery of the georgette gown."

"Can you?" said Peabody. "What is the explanation?"

"My dear fellow," said O'Farrel, "if you wanted to keep a woman in a certain place what would you do?"

"I should lock her in," said Peabody.

"Exactly," said O'Farrel, "and that is why the door of the Turkish Café was locked; but whoever locked the woman in the gold kimono in the Turkish Café made doubly certain by taking away her clothes. That is the reason that she was dressed in a gold kimono, and that is the reason that the individual who locked her in, in his hurry, dropped her georgette gown outside the door. The same individual, to whose clothes one of the diamante buckles on the gown had probably stuck, dropped this buckle at Sepach Farm at the bottom of the stairs, where you found it. Therefore," said O'Farrel, "I would say that the young man in the dry clothes was with the woman in the gold kimono at the Turkish Café before the rain started, just before you spoke to the man in the plus-fours. He goes off, after having locked our lady friend up in the Turkish Café, and dropped her gown outside, straight up to Sepach Farm, either does a little bit of shooting himself or sees somebody else do it, waits till the rain is over, and then walks back towards the Turkish Café, probably for the purpose of releasing the lady. When he sees you, however, in order to divert suspicion, he turns off and goes towards Hetton village. Very interesting."

"It is," agreed Peabody, "but the thing is, what are we going to do? My idea was that if we returned to-night to the farm we could hide those bodies."

O'Farrel spun round.

"Why, Peabody," he said, "this isn't a bit like you. Your duty is, obviously, to inform the police; yet I find you coming to me with some scheme about hiding bodies."

"I don't think you've told me the truth," said O'Farrel, "or, if you have, it hasn't been the whole truth. Another thing, you insult my intelligence by suggesting that Kenkins lends us his assistance. I don't like Kenkins. He reminds me of a logical elephant both from the mental and the physical point of view, and I'm certainly not going to be mixed up in any crime investigations assisted by Mr. Kenkins. Therefore, Peabody, my lad, you will have to do without my help."

O'Farrel stuck another cigarette into the long holder, and grinned at Peabody.

Peabody was amazed. He had thought that O'Farrel would jump at the chance of being in on a first-class mystery. He realised that O'Farrel had quickly discovered the weak part in his story, and was convinced that he had not told the whole truth, but even this did not explain O'Farrel's unwillingness to embark on anything which looked like an adventure.

For a moment Peabody was inclined to tell O'Farrel the whole truth; to inform him that the mysterious woman in the gold kimono was Mrs. Peabody, but after an instant's hesitation he resolved on his policy of silence.

"You go round, and get old Kenkins to help you," said O'Farrel. "He's the fellow for you. In the meantime I'm fairly busy. I've got to think out the ending of a short story to-night, and get it finished before twelve. Come back and tell me when you have elucidated the mystery."

Peabody got up. More surprised at O'Farrel's attitude, he thought the best thing he could do would be to go round and see if Kenkins would assist him—Kenkins whom O'Farrel described as a logical elephant, but whose logic was often as useful as O'Farrel's Irish intuition. At the same time he felt intense disappointment in not having O'Farrel's help.

He shook hands with O'Farrel, who walked with him to the front door.

Outside, in Gower Street, a taxicab was crawling past.

"There's a cab," said O'Farrel, "jump into that, and you will be at Kenkins' place in five minutes. Give him my love, and say I hope his pet rabbit dies! Good-night!"

As Peabody stepped into the cab O'Farrel shut the door. He had thrown off his air of lazy nonchalance, and dashed up the stairs of his flat three at a time. Inside, he rang for his man.

"Sparks," said he, "go round to the garage and get my motor-cycle. See that the petrol tank's filled, and bring it back here as quickly as you can. I'm going to the country; I may be a few days. Be quick, Sparks!"

Sparks disappeared, and O'Farrel, going into his bedroom, changed quickly into a tweed suit. Fifteen minutes later, after having consulted a road map, in the face of a head wind, and with the rain beating on his mackintosh, O'Farrel rode rapidly over Waterloo Bridge. There was a smile on his face. Before him lay the mystery of Sepach Farm, and O'Farrel liked mysteries but he preferred to handle them alone.

PEABODY, smoking his pipe in Kenkins' consulting room, was gratified by the reception of his story. Kenkins was a great believer in Peabody, and had signified his willingness to help in any way he could, more especially when he heard that O'Farrel had refused to have anything to do with the mystery. Kenkins, who had a certain heavy contempt for the airy persiflage of O'Farrel and his semi-cynical attitude towards life, felt rather pleased that he was to have the opportunity of assisting Peabody.

"You know, Peabody," said Kenkins, "there is one thing I can't understand, and that is the remark that this man in plus-fours made to you in the train. You remember he said, 'You say you are going to the police. All right! Go to them, tell them your story about Sepach Farm, tell them your story about shots and bodies. I tell you that they won't believe you. They will tell you that you are mad, that you are suffering from hallucinations.' Well," said Kenkins, "that is a funny thing for him to say. If he were not bluffing it could only mean one thing, and that was that he knew that for reasons best known to themselves, the police would do their best to keep this business at Sepach Farm quiet, even if it meant telling you that you did not know what you were talking about. I propose we call the bluff."

"How?" asked Peabody.

"Oh! That is simple enough," said Kenkins. "Let's go round to Scotland Yard, tell them the story, and see what they say. They can easily get into touch with the local police."

Peabody thought for a moment; he realised that, if Kenkins' idea was not correct, by going to Scotland Yard he would be raising a hue and cry. At the same time, it was obvious to him that the police had got to know sooner or later, and he knew, too, that if he acted quickly, and returned to the farm, after going to Scotland Yard, he could assist Irma to escape, if necessary, before police inquiries were made. After all, he knew that it was impossible for her to have any hand in the actual murders.

"All right," he said eventually, "let's go to Scotland Yard now. We will soon see if the man in plus-fours was bluffing or not."

Things move quickly at Scotland Yard, and five minutes

after passing the portals Peabody and Kenkins were sitting in

Sir John Scarrell's office, he having been summoned from the

House nearby.

Peabody, who was getting rather tired of telling his story, waited impatiently to hear what the Assistant Commissioner would have to say. Sir John Scarrell pressed a button on his desk.

"Your story is an amazing one, Mr. Peabody," he said, "and I shall have to ask you to wait for half an hour while I investigate."

He turned to the police-inspector who had entered the room in answer to his bell.

"Get through to the Chief Constable at Stranover, Jevons," said Sir John, "and ask him to get into touch with Hetton-on-the-Sands station. I want a responsible officer sent up to a place called Sepach Farm near Hetton, to report on any out-of-the-way occurrences which may have transpired this afternoon and evening in that district."

The inspector went off, and Peabody and Kenkins waited patiently. Twenty minutes afterwards, Sir John Scarrell, in response to a message, left the room, and when he returned he was smiling rather peculiarly, Peabody thought.

"Mr. Peabody," he said, "I don't know whether you are trying to pull our legs, but the inspector in charge of Stranover Station informs me that there are no bodies at Sepach Farm, and that, far from any murders being committed there this afternoon, his police-sergeant, a most responsible officer, was actually standing up from the rain in Sepach Farm at the time you tell me these weird events happened."

Peabody rose to his feet amazed.

"Perhaps," went on the Assistant Commissioner "you are not very well, your nerves may be out of order. I have known people suffer from hallucinations before."

Peabody was about to speak but Kenkins jabbed him with his arm.

"I think you may be right," said Kenkins suddenly to Sir John Scarrell, "my friend, Peabody, has not been at all well lately, and I think it is quite possible that he has been imagining things. He needs a holiday. Come on, old man. Sorry to nave disturbed you, Sir John."

So saying, Kenkins took the astonished Peabody's arm, and led him swiftly out of the building. Outside he summoned a cab.

"That clinches it, Peabody," he said, "the man in plus-fours was right. There's something on at Sepach Farm, something that's so big that even the police are trying to keep this business quiet. By Jove! I'm beginning to see things now. Don't you see? The man in plus-fours knew what was going to happen at Sepach Farm that afternoon, he was looking for somebody, possibly trying to stop it happening. I should say that the man in plus-fours is a detective. Anyway, there's nothing to be done at the moment, but I looked up the A.B.C. before we came out. There's a train to-morrow to Stranover at 6.30 in the morning, and I propose we catch that. In the meantime, you'd better sleep at my place. We'd better turn in as soon as possible."

This was easy to say, but they sat in front of Kenkins' fire until two thirty, discussing the strange turn which events had taken. Peabody guarded his tongue carefully so that he should not give away his own particular secret.

At the back of his mind there still lurked some little amazement that O'Farrel had turned the whole thing down so inexplicably. Peabody might have been still more amazed had he known that the moment he ascended Kenkins' stairs on his way to bed Etienne O'Farrel had already arrived at Sepach Farm!

IN spite of the fact that another drizzle of rain had begun and that he was thoroughly tired after his fast ride to Sepach Farm, O'Farrel felt quite pleased with himself as he pushed open the rickety wooden gate which led to the farm courtyard.

On the journey his mind had been busy with the story which Peabody had told him, but O'Farrel, whilst having the greatest belief in Peabody's integrity, certainly did not consider that his friend had told him the whole truth.

First of all, it was entirely unlike Peabody to get mixed up in an affair like this one unless there was very good reason, and, candidly, at the moment O'Farrel could see no reason. The idea had come to him that possibly Peabody was endeavouring to shield someone, but who this somebody was O'Farrel had not the slightest idea.