RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

Recent bibliographic research conducted in collaboration with the Australian bibliophile Terry Walker and the New Zealand writer Keith Chapman (pen name "Chap O'Keefe") led to the discovery of four novels by Peter Cheyney which, until now, have never been published in book form.

The titles of these novels are:

Indirect evidence supports the assumption that the present novel, "The Vengeance of Hop Fi," was originally serialised in the British newspaper The Sheffield Mail, presumably in 1928. In a blurb advertising an upcoming serial called "Death Chair" in its sister-publication, the issue of The Sheffield Independent for April 15, 1931, writes:

"DEATH CHAIR" tells of a journalist who looked for a story and found a murderer. It is full of thrills, puzzling situations and brilliant amateur detective work. MR. PETER CHEYNEY is already well known to Sheffield Mail readers who will remember his splendid stories "The Vengeance of Hop Fi" and "The Gold Kimono."

In 1928 "The Vengeance of Hop Fi" was syndicated for

publication in at least two countries—Australia and New

Zealand.

It was first serialised on the pages of The Auckland Star, New Zealand, beginning on July 7, 1928. Digital image files of this version are available at PapersPast, the web site of the National Library of New Zealand.

In Australia it was first published in The West Australian, Perth, beginning on September 1, 1928. The Brisbane-based newspaper The Queenslander printed its first installment of the serial in the following year, on March 14, 1929. Digital image files of both versions are available at Trove, the web site of the National Library of Australia. Copies of these files were used to produce this, the first, book edition.

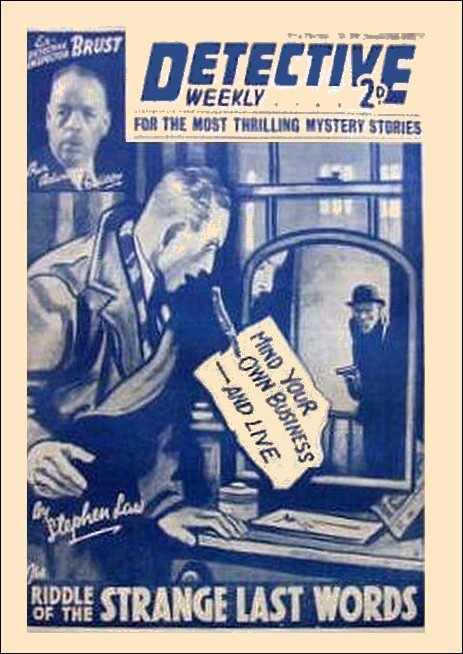

A novelette published in the British magazine Detective Weekly on January 29, 1937, under the title "The Mark of Hop Fi" is presumably an abridged version of "The Vengeance of Hop Fi." Authorship of the novelette is attributed to a "Stephen Law," evidently a hitherto unknown pseudonym used by Peter Cheyney. This assumption is supported by another coincidence of name and title. In 1930 and 1931 respectively, The Sunday Times, Perth, Australia, and The New Zealand Herald, Auckland, published a Peter Cheyney serial called "The Gold Kimono." On May 20, 1937, Detective Weekly published a novelette by "Stephen Law" under the same title. Coincidentally, this issue of Detective Weekly contained the 8th installment of Cheyney's Lemmy Caution novel "Poison Ivy," so it may well be that a pseudonym was used to avoid double-billing Cheyney. The only other work found under the byline "Stephen Law" is the novelette "The Riddle of the Strange Last Words" (presumably an abridged version of "Death Chair"), which Detective Weekly published on January 16. 1937. Incidentally, the cover of this issue illustrates a scene from "The Vengeance of Hop Fi," not, as the title on the cover suggests, from "The Riddle of the Strange Last Words".

Detective Weekly, January 16, 1937. Cover art

illustrates

following scene from Chapter IV of "The

Vengeance of Hop Fi."

Stuck between the frame and the mirror in the bottom right-hand corner was a dirty piece of paper. At the top was a crude drawing of a German steel helmet, and underneath, scrawled in an almost illegible hand, were the words:— "Mind your own business—and live!"

Typographical and other obvious errors found while processing

the source files from The Queenslander and The West

Australian used to build this e-book have been corrected

without comment. The name given to one of the villains in the

original newspaper versions of the

story—"Stahlhauben"—is not a correct German name; it

is the plural form of the word for "steel

helmet"(Stahlhaube). For the sake of linguistic accuracy

the correct name form—"Stahlhaube"—has been used in

this e-book edition. For the same reason the other name under

which this character is known—"von Eison"—has been

corrected to "von Eisen."

Thanks for making "The Vengeance of Hop Fi" available

for publication by RGL go to Terry Walker, who collected and

pre-processed the files from which the book was built.

—Roy Glashan, April 3, 2017

WHEN I got to the top of Frimley Hill I knew I couldn't stick it much longer. The blister on my heel was sending a red-hot pain up my leg with every step. I sat down in the hedge and took off my broken boot. The relief was wonderful, but tinged with the thought that I must move on in a little while. I felt terribly weak, for I had eaten nothing since the morning before. I had a shilling in my pocket—my last. Should I wire Conway from the next post office and ask him for help? Dare I risk my last shilling when I was not absolutely certain of his address?

I leaned back against the bank with my hands in my pockets. I was tired out and my head was beginning to fall forward. With a last effort I pulled myself together, and at the same moment my fingers clenched something hard in my pocket. I pulled it out—a blue leather case. I opened it and looked at the Military Cross which lay within. My last possession.

Tucked away inside the case was a cutting from the

London Gazette. I opened and read it:—"Lieutenant

John Relph—awarded the Military Cross for conspicuous

gallantry and devotion to duty."

Dimly, I realised that I was John Relph, sitting by the roadside, broke. The Cross in its case seemed to me like a remote connection with some other existence. With an effort I got to my feet and stumbled along the road. In the distance I could see an inn.

They were kind folk. The woman gave me some cold water and boracic and a piece of lint. I had a drink, and a crust of bread and cheese, for which they refused to take any payment. I thanked them, and sat down on the bench outside the inn.

Presently a big car appeared and pulled up outside. The face of the man who descended from the car and was about to enter the inn seemed familiar to me. He stared hard at me for a moment and then walked to where I sat. His voice was brusque, and I realised that he was a foreigner.

"I know you," he said, "I meet you in Cologne. I am Zweitt—Henri Zweitt. Don't you remember. In the riot—you help me!"

"Good God! Zweitt!" I exclaimed, astonished. "What are you doing here?"

I remembered the man well. He had got mixed up in one of the never-ending riots in Cologne which followed the British occupation. I had managed, with a party of our Military Police, to rescue him from the infuriated crowd.

"I am working for a firm 'ere," he said. "In London. Wines an' spirits. What are you doing, hein?"

I told him. He listened in silence. Then he said:

"Listen to me. I 'ave lunch 'ere. You join me. I will 'ave no refusal. Then I go to London. You come with me in the car. There is a vacancy for a clerk—a junior in my firm. I am 'ead manager. I will get you the job."

I could hardly believe my ears. Such good luck seemed impossible. I stammered my thanks.

Zweitt pulled a fat wallet from his pocket.

"'Ere is money," he said, pushing three five-pound notes into my hand. "When we get to London you will buy clothes and a lodging. Then I will send for you. I am Henri Zweitt. I do not forget."

I was silent, astounded by my good fortune. It was true that I had got Zweitt out of a nasty situation. We had arrived just in time to prevent the crowd from pulling him to pieces. Apparently, by the look of his wallet, he had done pretty well out of the war.

When, after lunch, we left the inn and entered the car I took a parting look at Frimley Hill, on the top of which I had that morning railed at my bad luck. The innkeeper bade me a hearty farewell.

"Good luck," he said. "Maybe this old house will be the turnin' point in your fortunes."

I thanked him and we set off. Henri Zweitt sat back in the car. Now that we had left the inn he seemed to have become more serious. Occasionally he glanced nervously over his shoulder at the road behind. The unaccustomed food and wine had made me drowsy, and the afternoon air was heavy. I closed my eyes and presently was fast asleep.

I WAS awakened by Zweitt pulling at my sleeve. I sat up

and rubbed my eyes. We were in London, some way down Oxford

Street, going towards the Park. In a minute we turned into

Poland Street, and Zweitt stopped the car outside a fairly

decent looking house, which he entered.

Presently he came out, and at his request I followed him into the house. Here he introduced me to Mrs. Game, the owner of the place, who showed me to a room on the second floor. It was clean and decently furnished, and there was a bathroom on the same floor. She told me the rent would be fifteen shillings a week. I thought this very reasonable, and paid a month's rent in advance.

Zweitt had disappeared, so I hurried out, and, before the shops closed, bought what I required. I returned about half-past nine, and sat in my room reading. About ten o'clock someone tapped at my door, and Zweitt entered. He appeared worried, but he accepted a cigarette, and sat down in the armchair. Suddenly, with a peculiar, strained look on his face, he leaned forward.

"Relph," he said, "you are a brave man. I will tell you—" He broke off suddenly with a forced laugh—"Eet is nothing. I mus' 'ave my joke," he said.

It struck me that his brand of humour was rather unusual, but I said nothing.

After a few minutes he went down to his room and reappeared with a bottle of whisky. He started talking about the old days in Cologne, helping himself, time and time again, from the whisky bottle. It was half past eleven when he rose unsteadily to his feet and bade me good-night. As he fumbled with the handle of the bedroom door he spoke to me over his shoulder.

"To-morrow I fix you that job," he said. "You are a brave man—I, Zweitt, am also brave." He laughed drunkenly. "I do not care for them—not one bit!" he cried, and lurched off along the passage.

I AWOKE early next morning and had finished dressing,

when Mrs. Game entered, at eight o'clock, with my tea, and

informed me that Zweitt had suggested that I breakfast with him

in his room.

He was showing the effects of last night's whisky pretty badly, and there were heavy lines under his eyes.

Presently he got up and walked over to the window. He stood, looking out on to the sunlit street for a while. Then he turned and, with his hands in his pockets, addressed himself to me.

"Relph—you come to the office this afternoon, at three o'clock," he said. "I will see you there. Do not be late. 'Ere is the address."

He put on his overcoat and hat, and with a nod walked out of the room. I thought his manner was abrupt and moody, and, thinking that the whisky had upset him, dismissed him from my mind. I was amusing myself looking at some books on the mantelpiece, when Mrs. Game entered.

"There's a man downstairs—a Chinaman, Mr. Relph. 'E wants Mr. Zweitt. I've told 'im that Mr. Zweitt's gorn, but 'e don't seem to understand. I thought per'aps you'd come down an' talk to 'im."

I followed her downstairs. Standing in the hall was a Chinaman. His costume struck me as being rather extraordinary. He wore a suit of blue overalls, such as are worn by artisans, and a greasy bowler hat was perched on the back of his head. A shiny pigtail hung over his right shoulder, whilst a horrible scar, starting in the middle of his forehead, reached almost to his left ear, just missing the eye. In his hand he held a letter, sealed with a great blob of black wax. He looked me over, almost insolently, as I approached.

"Mr. Zweitt," he enquired, his head on one side.

"Mr. Zweitt is out," I said. "What is it you want?"

"I wan' Mr. Zweitt," he said.

His perpetual grin annoyed me.

"Well, Mr. Zweitt isn't here," I said, "and I don't know when he will be here. You'd better leave any message you may have for him."

"I shall leave nothing," he said. "I want Mr. Zweitt. Where is he?"

"Look here," I said. "I've given you all the information I'm going to. Either leave your message or get out—whichever you like!"

He grinned more broadly. In another minute I should have hit him.

"Velly well," he said. He raised his grinning face and looked me straight in the eye. The malevolence in his gaze was appalling.

"Good morning, my gentleman," he said and, turning on his heel, walked out of the house.

I WENT upstairs to Zweitt's room and lit a cigarette. I was feeling remarkably bad tempered after my encounter with the Chinaman. From behind the cover of the window curtain I could see his dirty blue overalls disappearing down Poland Street.

I wondered what connection could possibly exist between Zweitt and the Chinaman who had brought the letter. I wondered what was in the letter, and why the Chinaman would not leave it.

Eventually I went out. I lunched at Lyons and at two o'clock prepared to make my way to the city. Zweitt had given me the address of his firm on a piece of paper. It was:

John Brandon, Ltd., Wine Shipper. Brennan's Buildings. Cannon Street, E.C.1.

Brennan's Buildings were situated in a narrow turning off Cannon Street, and the offices were on the ground floor. When I pushed open the door a bell sounded, and, after a moment's interval, Zweitt came out of the inner room, closing the door softly behind him.

"So. You are 'ere," he said. "I have talk with Mr. Brandon about you. You go in now and see 'im."

He seated himself at a desk and commenced writing. I took off my hat and knocked at the door of the inner room. A voice bade me enter, and I went in.

Brandon was seated behind a large desk in the centre of the room. The top of this desk was littered with papers and books of every description. Everything was untidy, and his appearance was in keeping with the rest of the office. A coat which seemed much the worse for wear hung upon his shoulders. His collar, cut with very deep points, stood away from a shrivelled neck, the skin of which seemed to have the consistency of parchment. Almost entirely bald, the fringe of white hair round his head, and the long, straggling whiskers which grew to his chin gave him the most extraordinary appearance. His blue eyes twinkled incessantly. I discovered afterwards that he had the habit of fixing his eyes steadfastly upon the face of the person to whom he was talking, and this disconcerting habit he practised upon me at this moment.

"And so this is Mr. Relph," he said pleasantly, his eyes twinkling like two little stars. "Well, Mr. Relph, Mr. Zweitt informs me that he has engaged you to be our new junior. Excellent! Your salary will be three pounds per week. Mr. Zweitt will instruct you in your duties. Supposing you start work to-morrow? Very well, Mr. Relph, you may go."

I left the office having said precisely nothing. Outside Zweitt turned his chair round.

"So. You are engaged," he said. "That is good. You start work to-morrow? You will draw a full week's salary. I will see to that. I do not forget."

"You've been very decent to me, Zweitt," I said. "If ever I get the opportunity of doing you a good turn I shall certainly take it."

His eyes lighted up. "You would do that?" he said. "Yes, I believe soon you may have the opportunity. We shall see."

"Look here, Zweitt," I said. "Is there anything wrong?"

He sat silent, occasionally stabbing the pad of blotting-paper on his desk. I could not see his face. After a moment he got up and walked over to the fire-place, and stood, his hands on the mantelpiece, gazing into the fire. Suddenly he turned round.

"I 'ave been a good friend to you, Relph," he said. "If I ask you to do me a favour, will you do eet?"

I could see the beads of perspiration standing out on his forehead.

"Why, of course," I answered. "I'd do anything in my power to return your kindness. What's wrong, Zweitt?" I asked.

"'Eet is nothing much. I do not think that eet matters much at the moment, but per'aps something will 'appen—something will arise, and then I will ask for your 'elp."

He put his hands in his pockets and returned to his desk, at which he stood staring as if unable to make up his mind.

"Well, you will want to be going," he said eventually. "Per'aps I shall see you to-night. Au revoir!"

It was evident that he did not wish to say anything more at the moment, so I put on my hat and left the office. As I was about to turn into Cannon Street, I perceived the Chinaman who had called at Poland Street for Zweitt approaching. As he mounted the steps which led to the entrance he drew from the breast of his dirty overalls a letter. I could distinctly see the blob of black wax on the back of the envelope. I wondered how he had found Zweitt's business address.

For a moment some instinct prompted me to return to the office and speak to Zweitt, but I immediately dismissed this from my mind. After all, it was no business of mine. With this thought I boarded a passing 'bus, and made my way westwards to Conway's flat in Berners Street.

In a few minutes I was shaking hands with my old friend.

"Well, if it isn't old Relph," he said, heartily. "Come into the study. Of course you'll stay and have tea."

He dragged me after him into his study, and pushed me into a chair, seating himself opposite. "I'm awful glad to see you, Relph," he said. "I've seen practically none of the old crowd. What are you doing in London?"

I briefly recounted my adventures during the last three or four months, finishing up by telling him about my job with Brandon Limited. He nodded sympathetically.

"Why didn't you get in touch with me before?" he asked. "Anyhow I'm glad you're fixed up now."

"You look pretty prosperous, Conway." I said.

"Oh, I haven't done so badly," he answered. "I left the R.A.M.C. immediately after the Armistice. There wasn't much doing, and it wasn't exciting enough. Then I bought this practice, which keeps me pretty busy. Then, to my extreme joy, I managed to get appointed Police Surgeon to this district two months ago. So taking things into consideration, it might be worse with me."

He pushed over a big bowl of tobacco. "Where are you staying?" he asked. I told him. Then tea arrived, and we began reminiscing of the old days.

About 6.30 I took my leave. Conway accompanied me to the door.

"Come in any old time, Relph," he said. "I'm always here, and if I've a patient there's plenty to read in the waiting-room."

We shook hands and I set off for Poland Street. I let myself into the house with the key which Mrs. Game had given me and went straight upstairs to my room. As I entered my eye was caught by a note stuck between the glass and frame of the mirror on my dressing table. I tore open the envelope and read:

Dear Relph,

You say to-day that you will help me if I ask. Please meet me at Salvatori's shop in Angel Alley near Wardour Street at 9 o'clock to-night. It is urgent. For God's sake do not fail.

Henri Zweitt.

I stared at the note in amazement! What could be the matter? By the tone of the note it seemed that Zweitt was in some serious trouble. I wondered what he wanted me to do. I hoped sincerely that I had not let myself in for something undesirable when I promised him my help. However, it was up to me to go and see what it was all about, so at twenty minutes to nine o'clock I put on my hat and went out.

IT was a dirty little cul-de-sac off one of the

innumerable turnings in Wardour Street. At the end of the little

street, I could see a dimly-lighted shop. I approached and

examined the window. It was filled with dummy boxes of soups and

sauces. A few bottles of multi-coloured cheap sweets and a stale

loaf or two completed the contents. Through the window I could

see a little narrow shop with a counter on which were a pair of

scales and a tired-looking ham. There were one or two chairs,

and a little table in the shop, and a notice saying that tea and

coffee were served. At the far end of the shop was a door, the

top half of which was glass, covered with the dirty remnant of a

window curtain.

As I entered the shop the door at the end opened, and a man walked round behind the counter. He was a big, burly man, with dark black hair, and long black moustache—obviously Italian.

"Is this Salvatori's shop?" I asked.

The man stared. In his big black eyes I thought I could detect a look of fear.

"I am Salvatori. What you want?" he asked.

"I'm waiting for a friend," I answered. "Give me a cup of coffee, please."

He lit a tiny gas-ring on the counter, and proceeded to heat the coffee. Periodically he glanced at me and at the entrance to the shop. Presently he brought the cup of coffee, and placed it on the little table. His hand was trembling, and a stream of perspiration was running down one side of his face. He stared at me closely.

"You are Inglees, eh?" he asked.

"That's so," I responded shortly, and commenced to drink the coffee. He brought a chair and sat down on the other side of the table.

"You e'scuse me, please," he said after a minute. "You wait for someone 'ere. You tell me who—please, I ask you."

In the ordinary course of events I should probably have been rude to the man, but when I looked up from my coffee there was such an entreaty in his look that I answered civilly.

"Zweitt."

His eyes brightened.

"You wait for Henri Zweitt," he repeated slowly. "You are a fren' of Henri Zweitt. Tell me, please. You know 'im a long time?"

I was getting fed up with being questioned.

"I haven't," I said. "Mr. Zweitt's a friend of mine, and he has asked me to meet him here at nine o clock. Anything else you want to know?" I asked, looking him straight in the eye.

He looked down at the table. "Mister," he said, tremulously, "I do not t'ink that Zweitt come—my God, I do not t'ink he come!"

"Look here," I said sharply, "what the devil's all this about?"

He looked at me. Fear was written all over the man. Beads of perspiration were standing out on his forehead.

"Listen," he said, "your name is Relph?"

I nodded.

"Zweitt tell me," he continued, "I tell you why I have great fear. Zweitt say you are a brave man. You will not care."

He leaned across the table. His voice had sunk to a mere whisper.

"Ten—twelve years ago. I work for a beezness in Milan. Zweitt is there also. De boss of de beezness is called Moreatte. We 'ave de office on a ground floor. Underneat' is de vaults. One day Zweitt an' me go to de circus. After, Zweitt find 'e 'as left 'is bag at de office. We go back. De door is locked, but Zweitt get tro' de window. I follow 'im. We getta de bag. Then Zweitt 'e 'ear a noise downstair. We are brave men. We go to look—"

He broke off suddenly. A motor-horn had sounded in the street nearby. Then it sounded again.

Salvatori looked at the clock above the door. It was ten minutes past nine.

"Listen," he said. "You mus' go. You come back 'ere at ten o'clock. I tell Zweitt to wait. Please, you mus' go!"

He almost pushed me towards the door.

"You come back at ten. I tell you the rest of the story—please do not fail."

"I won't fail," I said, and walked out of the shop. My curiosity was thoroughly aroused. What did all this business mean?

I turned into Wardour Street. Drawn up against the kerb on the corner was a big car. As I turned the corner a woman descended from the car, and made her way towards the cul-de-sac. She was a woman of middle height, and in the dim light of the solitary street lamp I could discern her evening cloak of bronze-coloured velvet, and caught a glimpse of beautifully dressed black hair. She entered the shop. I saw Salvatori hold the door, and bow his head respectfully.

I walked towards the Park, my brain busy with a dozen questions on this strange sequence of events. I was keen to see Zweitt, to get some explanation from him. I walked about, and at a quarter to ten retraced my steps to Salvatori's shop.

There was no one in the shop, and after a minute I rapped on the counter. Still nobody appeared. I rapped on the door at the far end of the shop. Nothing happened. With an exclamation of annoyance I pushed open the door. As I crossed the threshold a sight met my eyes which made me draw back in horror.

With his head in the fireplace, and the handle of an ordinary table knife sticking in his breast, lay Salvatori. His hands were clenched, and his eyes, wide open, were fearful. A thin stream of blood ran from the wound and trickled into the fireplace.

I remembered Conway. His place was but a few minutes away. I was turning to go when I saw Salvatori's eyelids move. Then his right hand moved, and with a terrific effort he half turned in my direction. As he moved the handle of the table knife moved with him. It seemed horribly grotesque.

I noticed a half-empty bottle of brandy on the mantelpiece. Seizing it, I knelt by Salvatori's side and poured a few drops on his tongue. He moved spasmodically. A bright metal object was revealed on the floor beside him. I slipped it into my pocket, thinking it might warrant examination later. Then the dying man's hand found mine and pressed my fingers. He was struggling to speak. I put my mouth to his ear.

"Who did this, Salvatori?" I asked.

His lips moved feebly. I raised his head. In the dim light of the dirty room I saw the perspiration on his forehead, and the fear in his eyes. His voice sounded cracked and harsh In the silent room.

"Zweitt—did—not—come." he gasped. "I tell you—"

He moistened his lips, and with a terrible effort sat upright.

"The end of de story." he gasped. "I tell you—Sour Milk—De Sour Milk!" He fell back into the fireplace—dead!

"WELL, Mr. Relph, it's a strange business."

The detective inspector turned the knife between his fingers. We were seated in Conway's study, and I had just finished telling my story to Inspector Jaffray, of Scotland Yard, who had been hurriedly summoned to the scene of the murder.

"Of course, there's no obvious motive," the Inspector went on. "It's pretty evident that Salvatori was stabbed some time between ten minutes past nine and a quarter to ten. As far as I can see there is absolutely no clue. We've got to find Zweitt. That seems to me to be the most important thing. Evidently there was some sort of business going on between him and Salvatori. Then there's that Chinaman who was so keen to see Zweitt."

"It's quite on the cards that Zweitt may turn up at the office to-morrow," I hazarded.

"He may, but I don't think he will," said the inspector. "I think Zweitt will keep out of the way. I'm having all the ports watched, and we'll take good care that he doesn't get out of the country, but London is a big place, and there are lots of holes where a man can hide in spite of all the police combing in the world."

Conway lit his pipe.

"You suspect Zweitt, Inspector?" He asked.

"Why not?" said the inspector. "He has an appointment with Salvatori and doesn't turn up till late. He sees Mr. Relph talking to Salvatori and waits till he goes. Then he enters the shop. They quarrel and Zweitt stabs Salvatori."

A sudden thought leapt to my mind. Excited by the happenings of the evening I had forgotten the mysterious woman in the car who had entered the shop just after I left it. Had she murdered Salvatori? For a moment I hesitated; then some inexplicable instinct told me to hold my tongue.

"That's all very well, Inspector," said Conway, "but if Zweitt intended to kill Salvatori he would never have written that note to Relph asking him to meet him at the shop—unless, of course, the crime was unpremeditated."

"Well, Doctor, doesn't everything point that way?" asked the detective. "Relph tells us that the knife was stuck in the ham on the counter outside. I should say that the quarrel took place in the shop. Salvatori, frightened, backed towards the door of the inner room, and his assailant followed him, picking up the knife en route. Surely, if the crime had been premeditated he would have brought a weapon with him. Besides, Mr. Relph says that Zweitt is a short, square man. He'd be fairly strong I expect, and that knife isn't too sharp. A fairly strong man stabbed Salvatori."

For some reason or other I felt relieved. Then the mysterious woman had not killed Salvatori. I remembered that she was short and slight. I looked at the knife which Jaffray still held in his fingers. She would never have had the strength to drive that blunt weapon into Salvatori. The detective rose from his chair.

"I'll be off," he said. "You'll be at your office to-morrow, Mr. Relph. I want to have a talk with your Mr. Brandon about Zweitt. He may be able to give us some information."

I told Jaffray that I should be at the office at 9.30 next morning. He wrapped up the knife in an old handkerchief, and with a good-night to us both left the flat.

"It's a funny business," said Conway, when Jaffray had gone. "I wish you had heard the end of Salvatori's story. I wonder why he didn't finish it. Perhaps he was expecting someone?"

"Very likely," I answered. "The whole thing is a mystery."

I put on my hat and coat, said good-night to Conway, and made my way to Poland Street. I was feeling upset about the whole business. I don't mind excitement, but I don't like too much of it. I realised, too, that I had done wrong in not telling Jaffray about the woman. Probably she could supply vital information.

Mrs. Game met me on the doorstep. She was, in turn, excited and depressed at the news.

"Oh, Mr. Relph," she said. "I knew it! I knew murder or something shockin' 'ad been done w'en the perlice come 'ere to-night. They asked me questions till my 'ead was near fit to burst. Mr. Zweitt disappeared, too, they say! Do you think 'e'll come back, Mr. Relph? Not that I'm worrying about the rent. It's paid for a fortnight ahead, but there's all 'is clothes an' things. An' the perlice—"

"Did the police search his room, Mrs. Game?" I asked.

"They're 'ere now," she said, indignantly. "At least they've left one perliceman 'ere to see that nobody disturbs 'is room. One of the 'eads is comin' to examine everythink to-morrow. I never 'eard of such goin's on in my life. I didn't." She clattered off, perturbed, but not exactly displeased with the excitement.

I went upstairs. As I passed Zweitt's room on the first floor I looked in through the open door. One of the plain-clothes men who had arrived at Salvatori's shop with Jaffray was seated at the table smoking a pipe and reading a newspaper.

"I don't envy you your job," I said with a grin.

He laughed. "Oh, I'm pretty used to it, sir. Though why the chief should want somebody on guard here all night, I don't know. I suppose he's got something at the back of his head, though."

"He expects Zweitt to come back," I said.

The detective grinned. "I don't think we shall see much of Mr. Zweitt," he said. "At least, not unless we lay hands on him ourselves. I should rather like to see him come back to-night."

He touched his pocket, and I heard the clink of handcuffs. "My orders are to arrest him on suspicion right away; but he won't come back, Mr. Relph."

I stayed chatting with the man for a few minutes, and then, bidding him good-night, went up to my room. Sitting on the bed, I thought over the strange events which had taken place since yesterday afternoon, when I had met Zweitt, on Frimley Hill.

I WAS not feeling at all easy in my mind. At the back of

my brain a conviction was growing that I had not played the game

by Jaffray in withholding the information about the woman in the

evening cloak. For the life of me I did not know why I had not

told him, except that for a moment, as I had seen her standing

beneath the dim light over the entrance of Salvatori's shop,

there had seemed something pathetic in her face, something that

was almost an appeal. In some remote manner she seemed to remind

me of someone I had met.

What had become of Zweitt? I undressed slowly, wondering. His attitude had certainly been strange. Zweitt had been badly frightened by something or somebody. His disjointed remarks of the night before took on a new significance. Why had he not kept the appointment at Salvatori's shop?

I stuck my hands in my trouser pockets and moved over to the window, stopping suddenly as my right hand closed over something in my pocket, something I had forgotten in the excitement of the evening, the bright bit of metal I had picked up from the floor beside Salvatori.

I pulled it out of my pocket and stood staring at it in amazement. It was an identification disc on a thin silver chain, such as was worn round the wrist, during the war, by officers, and it bore the name of my friend, Harry Varney!

For a moment I thought that my eyes had deceived me. I took it under the gas bracket and inspected it closely. There was no doubt about it. In spite of the wear and scratches with defaced the silver disc, the lettering was quite plain:—

2nd Lieut. H.J. Varney, 4th Loamshire Fusiliers, C. of E.

I stood wondering. Harry Varney and I had been the greatest friends ever since we joined the regiment on the same day early in 'fifteen, until the day in 1916 when he had been reported "missing, believed killed."

What was the disc doing in Salvatori's shop?

Once again the mysterious woman came into my mind. I felt terribly uneasy.

I sat down once again and thought. There was only one thing to be done. To-morrow I must make a clean breast of the whole business, and tell Jaffray everything I knew. Probably I had been guilty of withholding a most important clue. I put the identification bracelet down on the dressing-table and walked over to the window and looked down Marlborough Street.

The street looked stolid and peaceful, and the lamps twinkled brightly. I felt not in the least inclined to go to bed. I was over-excited, and the thought of a walk in the quiet outside appealed to me. I put on my coat and waistcoat, and, slipping quietly down the stairs, past Zweitt's room on the first floor, in which a light was still burning, I opened the front door and closing it quietly behind me walked off towards Regent Street.

LONDON streets by night have always held a strange fascination for me, and to-night the atmosphere of the last two days added to their mystery. I walked down Marlborough Street, finding some comfort in the sight of the burly policeman on duty outside the police station, and, crossing Regent Street, struck off down Maddox Street.

I had walked hallway down the darkened street, when I stopped to light my pipe. Turning to throw the match away, I saw a figure slink into one of the dark doorways a few yards behind me on the other side of the street. I walked on slowly for a few yards, undecided. Then, as I approached Bond Street, I quickened my pace, and suddenly turned round and faced about. Sure enough on the other side of the road a short figure disappeared from view. I carried on down Bond Street, glancing time and again over my shoulder, but evidently I was being followed no longer. I decided that the man had seen was possibly some half-drunken reveller returning home, and that my imagination was responsible for his sudden disappearance.

As I walked up Piccadilly and through Park Lane, I thought continuously of Zweitt, wondering how much or how little he knew of the death of Salvatori. The thought struck me that he might have returned to Poland Street in my absence, and I quickened my steps.

As I hurried past the dingy little shop with the wooden shutters half up, just as they had been when I went to keep my appointment with Zweitt, a picture of Salvatori came vividly to my mind. I saw him leaning across the table, his untidy black hair over his forehead, and that extraordinary frightened look in his eyes. Salvatori, as well as Zweitt, had been badly frightened of something or somebody. As I walked down Poland Street I could see that the light in Zweitt's room was still burning. I took out my key as I approached the house, but when I attempted to insert it in the lock I was surprised to find the door unlocked.

I pushed it open. As I crossed the threshold a peculiar smell came to my nostrils, a smell that reminded me of hospitals—chloroform! I stood still and struck a match. By its flickering light I saw that the hall was empty. The match went out as I stepped forward. I reached the stairs, and with a gasp of surprise tripped over something which lay at the bottom. I picked myself up, and standing against the wall on the right of the stairs fumbled with my matchbox. I was almost afraid to strike the match—afraid of what I might see at the bottom of the stairs.

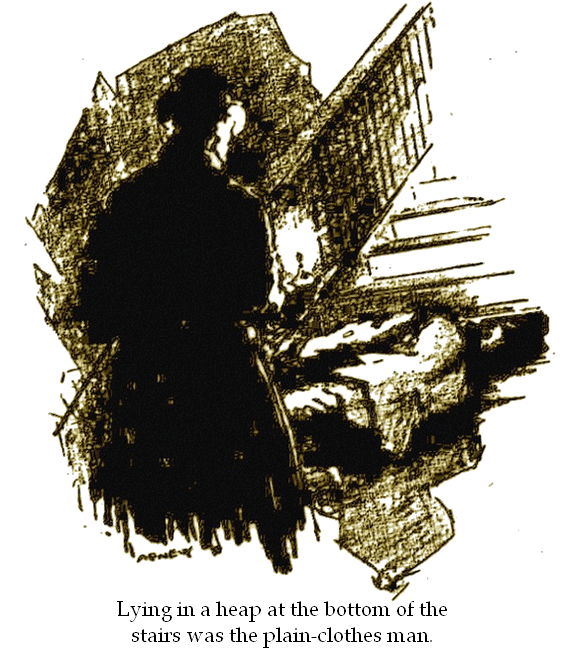

The match spluttered, and then burned brightly. Lying in a heap at the bottom of the stairs was the plain-clothes man who had been left to guard Zweitt's room. He lay sprawled across the stairs, one arm hanging limply, through the banister rails. With an overwhelming sense of relief I saw that he was breathing heavily. I ran to the head of the basement stairs and shouted for Mrs. Game. Then, returning, I straightened out the recumbent figure of the plain-clothes man, and possessing myself of his whistle, I ran out into Poland Street and blew vigorously.

AN hour later, sitting in Zweitt's room, the plain-clothes

man regarded Jaffray across the table with an air of an

injured innocent.

"It was all over so quickly, sir," he said. "I was outed before I knew where I was. I heard the front door shut when Mr. Relph went out, and looked out of the window after him. I suppose it was somebody tapped at the door downstairs, about twenty minutes afterwards, and I thought for a moment that Mr. Relph might nave left the door unlocked, and that it was the man on the Poland Street beat making his rounds. Anyway, I went down. As I caught hold of the handle of the door and drew it towards me somebody stepped slick into me and squeezed a handkerchief or something over my nose. He must have been a pretty big man, too, for I hadn't a chance against him, and I won the Metropolitan Police Heavyweight Championship last year," said the plain-clothes man somewhat apologetically. "That's all I know about it. Next thing I knew was Mr. Relph here bending over me."

Jaffray looked round Zweitt's room. The place had been thoroughly searched. Drawers were ransacked and the contents strewn over the floor. The bed had been pulled out, and the bedclothes flung over the rail. Whoever had searched the place had done his work thoroughly.

Jaffray filled his pipe. "Well, it's no good crying over spilt milk, and they certainly put it over neatly," he said. "You're certain it was a big man, Stevens?" he asked.

The plain-clothes man nodded. "Absolutely certain, sir," he said. "Directly I felt the chloroform cloth over my nose I put my hands up and his shoulders were well above the level of my own. I'm five feet nine," he added.

Jaffray smoked silently for a minute. "That disposes of Zweitt," he said. "He's just under middle height. It looks to me like a carefully planned job," he added. "They knew that I should be here first thing in the morning to look through Zweitt's things, if he hadn't turned up in the meantime, and they took good care to get here first. The man you saw following you, Mr. Relph, must have been a look-out man. I suppose he saw you well on your way down Bond Street, and then ran back and let the other fellow know that the coast was clear for a quick job. They knew what they were after, too," he glanced round the disordered room. "I wonder if they found it?" he added. "It's a funny business."

It was on the tip of my tongue to tell him about the woman and the identification bracelet, but the presence of Stevens deterred me. I was not quite certain how Jaffray would take my admission of withholding the information, and I thought I would wait until we were alone.

After a few minutes, with a final glance round the room and a word to the man who was taking the place of the unfortunate and drowsy Stevens, Jaffray prepared to depart. I volunteered to accompany him to the end of Marlborough Street, thinking that an opportunity would present itself for me to make my confession about the mysterious woman, but Jaffray was preoccupied and evidently desirous of thinking, so I made up my mind to wait.

At the end of Marlborough Street Jaffray stopped.

"Good-night, Relph," he said. "I shall be coming down to Cannon Street to-morrow morning to see your Mr. Brandon. See you then. So long!"

With a cheery smile he went off. As I returned to the house I wondered how Brandon would take the news of the murder and the disappearance of his trusted henchman, Zweitt. I wondered, too, how it was that Jaffray was so certain that Zweitt would not return. At the back of my head was an idea that the quiet chief inspector knew more about the whole business than appeared on the surface.

Just outside the front door I found Mrs. Game and the new plain-clothes man deep in conversation. Mrs. Game's opinion of Zweitt seemed to have changed in a remarkable manner, for she was confiding to her companion that she "'ad always thought that there was somethink funny about 'im, but then, orl these foreigners are alike, ain't they?"

I said good-night and went up to my room. It was half-past three, and the excitement of the evening had reacted on my nerves. I felt tired out. I lit the gas and walked over to the dressing table. A glance showed me that Varney's identification disc was gone!

Then my eyes fell on the looking-glass, which stood on the dressing table, and beside which I had placed the identification disc. Stuck between the frame and the mirror in the bottom right-hand corner was a dirty piece of paper. At the top was a crude drawing of a German steel helmet, and underneath, scrawled in an almost illegible hand, were the words:—

Mind your own business—and live!

WHEN I awoke next morning, the sun shining brightly through my bedroom window dispelled much of the gloom of the night before. At the same time I was considerably worried. The warning note which I had found on the mirror brought the Salvatori affair home to me personally. I walked to the office, and had been working for half an hour when Brandon arrived.

"Hard at work, eh, Mr. Relph?" His blue eyes twinkled humorously. "An excellent thing, hard work," he continued, unlocking the door of his room.

"I've very nearly finished these invoices, Mr. Brandon," I said. "What shall I do afterwards?"

"Let me see—let me see," he ruminated. "Oh, Mr. Relph, I think you had better read through those correspondence books which you will find on that shelf above Mr. Zweitt's desk—"

He stopped suddenly as the door opened, and Inspector Jaffray, accompanied by another man, entered the office. Jaffray stepped forward.

"Mr. Brandon, I believe?" he said.

"Precisely," said Brandon, "and what may I do for you, gentlemen?"

"Well, Mr. Brandon," said Jaffray, "I don't know whether Mr. Relph here has told you anything about the matter, but a murder was committed last night in Angel Alley. A man named Eustachio Salvatori was stabbed. There are some rather peculiar circumstances connected with the case concerning a man we believe to be in your employ—Henri Zweitt. I should like to ask you a few questions about this man."

"I will do my best to help you," said Brandon. "But surely no suspicion is attached to Zweitt. He is a most steady and reliable man, and has been employed here for a considerable time. I have the utmost confidence in his integrity."

He opened the office door. "Will you come in gentlemen?" he said.

"Thank you," said Jaffray. "I should like Mr. Relph to be present, if you don't mind, Mr. Brandon."

Brandon looked from the detective to me in amazement. "Of course," he said, apparently bewildered. "Of course—" He led the way into his office.

"The position is briefly this," said Jaffray. "Last night Mr. Relph received an urgent note from Zweitt, asking him to meet Zweitt at Salvatori's shop, in Angel Alley. Mr. Relph kept this appointment, but Zweitt did not appear. About ten minutes past nine Mr. Relph was requested by Salvatori to leave, and to come back at ten o'clock. Salvatori was evidently expecting somebody. Mr. Relph returned to the shop at 10 o'clock, and discovered Salvatori stabbed. As far as we can see, Zweitt did not return to his rooms last night after seven o'clock. We know he was there before that time, as Mr. Relph returned home at 6.45, and the note from Zweitt was awaiting him. At what time did Zweitt leave this office last night, Mr. Brandon?"

"That I cannot tell you," Brandon replied. "I left him working here at about 4.30 yesterday afternoon. You see, I live at Surbiton, and I usually catch the 4.45 at Waterloo. Zweitt had a fair amount of work to get through and I expected that he would be working here till about seven o'clock."

"Did you know anything of any friendship existing between the dead man and Zweitt?" asked Jaffray.

"Of that I am afraid I have no knowledge." replied Brandon. "I know that Zweitt saw Salvatori occasionally. You see, he was a customer in a small way. He served a few of the Italian houses in the neighbourhood with cheap Chiantis and other of the lesser Italian wines. We supplied him with these, and, of course, it is quite possible that in doing business they had become friendly."

"What was Zweitt doing in a motor car at Frimley?"

"At Frimley!" echoed Brandon, in astonishment. "I really cannot tell you. The day before yesterday he should have been at Kelsham!"

Jaffray closed his notebook. "Of course, Mr. Brandon," he said, "You have no idea where Zweitt is at the moment?"

Brandon smiled. "None whatever," he said, "How should I?"

Jaffray took up his hat.

"We'll be going," he said to his colleague. "Thanks for your help, Mr. Brandon. We'll let you know if we want you again."

Brandon arose and accompanied the detective to the outer door.

"I am sorry that I have been unable to help you any more, gentlemen," he said. "If I can do anything else, please command me."

I returned to my desk.

Brandon, stood in the outer office by the window, his hands clasped behind his back. He sighed.

"Mr. Relph," he said slowly. "This is a very serious business. Can it be that Zweitt has anything to do with this awful crime? I cannot find it in my heart to mistrust him. Yet why did he send you that note? A bad business, Mr. Relph—a bad business."

He went back to his office, closing the door behind him. In spite of his remarks he seemed remarkably unperturbed by Zweitt's disappearance and the fact that he was so closely associated with a serious crime.

I was sorry that Jaffray had gone without giving me an opportunity of speaking with him alone. The warning note which I had received the night before might possibly constitute useful evidence.

At half-past twelve Brandon came to the door of his office.

"You may go to lunch, Mr. Relph," he said, "and you need not return until one-thirty. I am surprised that we have heard nothing from Mr. Zweitt, but perhaps this afternoon will bring us some news."

He went back into his room, leaving the door ajar so that he could hear if any customers came into the outer office.

I WENT out and found a teashop near Brennan's Buildings.

Opening a newspaper which I had bought, I looked for some report

of the Angel Alley murder. There was a very brief report of the

crime, and I was surprised when I read that "the police had

excellent reasons for believing that the clues in their

possession would enable them to trace the murderer within a few

days."

This struck me as being extraordinary. What clues had the police discovered? I wondered if the astute Jaffray had inspired the Press report in order to lull the suspicions of someone who was connected with the crime.

Finishing my lunch, I paid my bill and made my way back to Brennan's Buildings. It was then about a quarter past one. I walk fairly quietly, and I suppose I did not make very much noise when I opened the outer door. The door of Brandon's office was still open, and as I walked to my desk I looked through. I saw Brandon on his knees by the side of his desk, groping in the waste paper basket, which, as usual, was full to overflowing. I turned my back to the open door and gave a slight cough, then I turned to hang up my hat and coat. When I glanced through the door again Brandon was at his desk writing.

Presently he went out to lunch, locking his office door after him. The afternoon seemed interminable, mainly, I suppose, because I was excited.

BRANDON returned to the office somewhere in the region

of three-thirty, and remained in his room until half past five.

He told me that I could close the office at six o'clock, and

gave me instructions as to how I should deal with any customers

who might come in.

Then, with a curt good-night, he went off.

At six o'clock I tidied up my desk, put on my hat and coat, and, unlatching the Yale regulator on the door, pulled it to behind me.

Dusk was falling as I left the entrance to Brennan's Buildings, and as I turned into Cannon Street I seemed to recognise a figure as it hurried past me. I stopped and looked back. It was the Chinaman who had brought the letter to Zweitt. When I saw him he was just passing Brennan's Buildings. I walked quickly after him, but the narrow turning was crowded with clerks and typists hurrying home, and as I reached King William Street at the other end of the alley I realised it was hopeless to endeavour to find him in the crowd.

I walked to the Bank station, took the tube to Tottenham

Court Road, and in a few minutes I was in Conway's flat. Conway

promptly suggested that as my present abode was not a

particularly cheerful spot having regard to recent events. I

should move my kit and take up my abode with him, more

especially as he was feeling a bit lonesome himself in the long

evenings.

I was glad to agree, and went off to Poland Street, returning soon after with my few belongings.

Conversation soon turned on the Salvatori murder.

"You think Jaffray's a good man at his job, Conway?" I asked.

"He's about the best man at the Yard," he answered. "He very seldom falls down on a case, and is highly thought of."

The telephone interrupted him, and he picked up the receiver.

"It's Jaffray. He wants to speak to you, Relph," he said.

I took up the telephone and spoke to Jaffray.

"That you, Mr. Relph? I'd be glad if you could come round to Salvatori's shop at once. I'll be there when you arrive. You'll find the shop door open."

I hurried over to Angel Alley. A cold wind was blowing, and I turned up my coat collar. As I approached the shop I saw that a single light was burning inside. One or two portions of the wooden shutters had been put up over the shop window, but the right half was left unshuttered, and the flickering light inside cast fitful shadows on the dusty bottles and boxes in the window.

Pushing open the door, I entered. Jaffray was leaning against the counter, his hands in his pockets, puffing at a short briar pipe. His bowler hat was pushed well back on his head, and he seemed immersed in thought. He straightened himself as I entered, and shook hands. There was some quality about Jaffray which allayed the feeling of depression which the dark shop and the weather had produced. Without wasting any time I told him of the mysterious disappearance of the bracelet, and gave him the warning note which had been left in my bedroom the night before.

He read the note beneath the dim gas light, which supplied the shop with its uncertain light. His eyes were gleaming, and a little smile curved his mouth. He folded the note, and put it carefully in his pocket-book. Then he chuckled quietly.

"That's a bit of luck, Mr. Relph," he said. "It's a funny thing, but criminals are the most conceited fellows in the world, and the chap who tried to draw that steel helmet was letting his conceit run away with him. I rather fancy, too, that his own life wouldn't be particularly safe if the heads knew he'd done it."

"The heads?" I queried. "Is it a gang, then?"

"That remains to be seen," he answered. "Except it's fairly obvious that it isn't one man." He walked to the centre of the shop, his hands in his pockets, and glanced about him. He stood there for a moment or two, and then turned to me.

"Will you step into the inner room?" he said. "I want you to show me just how Salvatori was lying when you found him."

I lay down in the fireplace and showed Jaffray as well as I could how Salvatori was lying when I entered the room. When I had risen to my feet Jaffray sat down in the dilapidated armchair and gazed thoughtfully at the floor, on which an ominous red stain still showed near the grate.

It was raining hard outside. A strong wind had arisen which howled dismally into Angel Alley. I glanced nervously round the shabby little room lighted only by the dim light of the cheap oil lamp.

"MR. RELPH,"—The detective's quiet voice brought me back to earth. "I'm going to confide in you. Let me tell you first of all that we are, all of us who are connected with this business, in danger. Needless to say, we shall do everything in our power to protect you. We are up against something big. I've handled a lot of bad cases, most of them successfully, but I realise I've met my match this time—I'm up against brains."

I stared at Jaffray in surprise.

"Don't misunderstand me. Mr. Relph," he said. "We've got to get them or they'll get us. They'll stop at nothing. They don't know how much you know, but I've had to show my hand to-day."

"Then the newspaper report was right," I said.

"No, it wasn't," said Jaffray. "When I had that paragraph inserted in the papers I did it with the express purpose of misleading certain people. It was purely by accident that I stumbled on a theory which fits the jig-saw of Salvatori's half-told story and our other slender theories."

Jaffray smoked in silence for a moment, then he told me to sit down. I took the rickety chair he indicated, whilst he walked to the door and glanced round the shop. Then he returned and drew his chair nearer to mine.

"This is what we're up against, Mr. Relph," he said. "I know it sounds like a fairy story, and it's quite on the cards that I'm wrong on one or two points. The thing which put me on the right track was Salvatori's tale. You remember he said, that ten or twelve years ago he and Zweitt were employed by a firm called Moreatte in Milan. I got in touch immediately with the Italian police, who, by a coincidence, had quite a fund of information about this firm, which they cabled to me. Before I tell you about that, however, I must interrupt myself to tell you—"

Jaffray drew his chair nearer to mine. His voice had sunk almost to a whisper. The night was so quiet that the lashing of the rain outside sounded weirdly loud, and the wind moaned a dismal accompaniment.

"Outside the sacred city of Pekin," Jaffray went on, "there is a monastery. It is called the Monastery of Li Tsu Chen. Although the priests were reported to have large quantities of treasure stored in the monastery, they were an industrious crowd, and spent their days making weird liqueurs and sweetmeats which they sold. They were good business-men, and had agents in every country of the world who sold their products for them. This Moreatte and Co., of Milan, were apparently their chief distributors. They seem to have been a pretty shady crowd. There were two partners running the business, an Englishman and a German. Suddenly, just before the outbreak of war in 1914, the business was shut up, and the partners disappeared. Certain information came into the hands of the Italian C.I.D. They made inquiries, and then—" Jaffray suddenly stopped speaking. He motioned me to keep silent, and listened intently.

"Listen—the music!" he whispered.

Above the sounds of the rain and wind outside I could hear a peculiar noise—Chinese music. It seemed to come from somewhere near, but the door between the shop and Salvatori's room was open, and we could see that we were alone. I felt a chill creeping over me—the soft cadences of the music (it sounded as if a reed instrument was being played softly) held something ominous. I looked at Jaffray. His face was drawn. Very slowly his hand stole to his hip-pocket. Then, as slowly, he leaned over to me and placed his automatic pistol in my hand.

"It's outside," he whispered. "Creep to the door with me, then run at 'em. Don't be afraid to shoot!"

My fingers closed round the pistol butt. I felt more secure. Together we crept to the shop door, bending low to avoid being seen through the window.

Then Jaffray flung the door open and we rushed out into Angel Alley. It was pitch dark outside, but down on the right-hand side of the alley I could nave sworn I saw the figure of a man running silently towards Mole Street. I ran swiftly in this direction, but after a moment I stopped. I knew that there was little chance of finding my man in the labyrinth of narrow turnings. A police whistle sounded—then another. I put the pistol in my pocket and hurried back to Salvatori's shop. At the end of the alley I could see a police bull's eye flashing in the shop.

I pushed open the door and entered. A police constable was bending over Jaffray, who lay on the floor just in front of the counter. His face was distorted with pain, and his eyes were closed. He breathed heavily, and in a strange gulping way. There was a sound of running feet—and two constables and Stevens came in.

Stevens spoke to one of the uniformed men.

"Over to Berners Street, quick, Jim," he said. "Get Doctor Conway. I hope to God we're not too late!"

We bent over the prostrate figure. Very slowly Jaffray opened his eyes. His will was fighting with the strange thing which was throttling him. He turned his eyes slowly to me.

"Relph," he whispered hoarsely, while I bent my head to within an inch of his face. "Careful—secret road—don't touch—the sour milk!"

A hoarse rattle sounded in his throat, and his head fell forward. The constable bent over him, then rose to his feet and touched his helmet. Jaffray lay still upon the floor. I gazed at the body of the man who a few minutes before had been talking to me in the inner room. I felt the weight of the automatic pistol in my pocket. He had given it to me. If he had kept it—?

A lump rose in my throat. I knew I had lost a good friend.

SEATED in my bedroom in Conway's flat I tried to review the whole business dispassionately. Sleep was out of the question. Jaffray's body lay in the surgery at the end of the corridor. I was possessed by a great loneliness. I had the horrible feeling that I was struggling in a net the meshes of which were drawing tighter and tighter about me. Jaffray's warning was imprinted on my brain—"We've got to get them or they'll get us!"

Unfortunately, the death of the Inspector had left us in a worse position than ever. Jevons, Jaffray's assistant, who was now handling the case, knew nothing except the few facts which I was able to give him, which, with the incomplete story of Salvatori, were little enough to work on. I had given Jevons a full and complete account of my last interview with Jaffray. He had listened carefully, and then scratched his bullet head in perplexity.

"It beats me," he said. "Unfortunately, Jaffray had said very little of real importance about the case to me. I think it must have been only this morning when he stumbled upon the right track. The extraordinary thing about the whole business is this 'sour milk.' What did Salvatori and Jaffray mean? In both cases these words were practically their last. What did Jaffray mean by 'the secret road'? Who was Moreatte, and what was the connection between the Chinaman and Zweitt? It seems to me," Jevons had said, in conclusion, "that I've got to start right at the beginning again, and not lose much time, either!"

NEXT morning I started to read the correspondence books

which Brandon had pointed out to me on the shelf above Zweitt's

desk. I thought that there was a remote possibility that I might

find some clue. I was disappointed, however, for the books

simply contained copy letters, such as are usually sent out to

customers, and related to shipments, or purchases and sales, to,

or from, different well-known firms. I had hoped that I might

find some correspondence with a firm in Milan, where Salvatori

had told me he and Zweitt were originally employed, but there

was nothing of the sort.

Brandon arrived fairly early, and spent most of the morning in his office. Nothing had been said of Zweitt's prolonged absence, and, as there was no mention of Jaffray's murder in the papers. I had not mentioned it.

After Brandon returned from lunch he started clearing his office of the mass of litter and packing cases, which were strewn about the place. It seemed that the office cleaners were not allowed to clean his room, and he performed this task himself pretty thoroughly. I thought it rather strange that he did not ask my assistance, and I was sorry for this, as I had made up my mind to examine his room as soon as an opportunity presented itself. The conviction had been growing in my mind that Brandon knew very much more about the mysterious disappearance of Zweitt than he had said.

Why had Zweitt been so anxious to procure the job for me? Was it because his disappearance had been arranged beforehand, and he knew that someone would be required in the office?

I could not quite believe this theory when I remembered his strained expression, and the peculiar remark be had made on the day of his disappearance. He had seemed to be in fear of something. I wondered if Zweitt was dead—if be had fallen a victim to the same mysterious agency which had been responsible for the deaths of Salvatori and Jaffray. Why had he asked me if I would do him a good turn if the occasion arose when it should be necessary?

Brandon left the office early. I tried his door, but it was locked as usual. I made up my mind that if I could obtain his key by some means or other I would take an impression of it and get a duplicate made. Brandon had been even more taciturn than usual during the day. He seldom spoke, and when he did it was to give some direction as to work to be done. When he had gone about ten minutes I started to make a thorough examination of the outer office. I pulled out the desks, moved the furniture, and examined every nook and cranny in the place. I was just replacing Zweitt's desk, when a knock sounded on the office door. I walked over and opened it.

On the threshold stood a man wearing the leather apron of a carter. He handed me a paper, which, on examination, proved to be an invoice for several dozen bottles of liqueurs.

"Where am I to put the stuff, Guv'nor?" he asked.

"I don't know," I replied. "Unless you bring it in here. Where do you usually put it? Have you delivered here before?"

"Oh, yus," he said. "We deliver here every month. An' we usually puts the stuff down in the vault. There won't be much room left 'ere if we dumps it in this orfis," he continued, looking round.

"I suppose the vault door is locked?" I asked.

"I'll go down an' see. Sometimes it ain't. I'll leave the stuff 'ere for now."

He went outside, and reappeared in a moment with a large packing case, which he pulled and pushed into the office. Then he tramped off down the stairs.

I waited for five minutes, but the carter did not appear, so I went downstairs in search of him. There was no sign of any cart or truck outside the building, nor had the doorkeeper seen anything of such a vehicle. It struck me that it might be useful for me to have a look at the Brandon vault, and I quickly descended to the basement. The vault door was very securely fastened with an ordinary lock and an iron locking-bar and padlock. A sudden thought came to my mind. I remembered that Salvatori had said that Moreatte's offices consisted of a ground floor office and vault. Was it purely coincidence that the geography of Brandon's offices was practically the same? I returned to the upstairs office and, putting an my things, locked up, and with a final glance round set off for Oxford Street.

I had proceeded some way down Cannon Street, when an idea came to me and I quickly retraced my steps to Brennan's Buildings. I went up to the office, and taking the office paste-pot I made my way down to the basement.

I put a little of the paste at each end of the locking bar where it would remain unnoticed, and a tiny piece on the padlock arm. Then I scrutinised my work carefully. Any attempt to open the door of the vaults would result in the seals formed by the paste being broken. The conviction was growing stronger in my mind every moment that the key to the Zweitt-Salvatori mysteries lay in Brandon's offices, and I made up my mind to search the place thoroughly the following evening.

When I arrived at Conway's flat I told him of my

decision.

"I think you're taking a bit of a chance, Relph, don't you?" he said. "Why not leave the matter to Jevons?"

I told him that Jevons had no possible excuse for searching the offices. At least I had an excuse for remaining late on the premises, but if Jevons' men did the job some explanation would have to be made to Brandon, and that was just the thing I did not want to happen. If I discovered anything there would be lots of time to tell Jevons about it afterwards.

"By the way," I asked, "did your further examination of Jaffray's body reveal anything?"

"Nothing beyond what I have already told you," he answered. "His body was taken away early this morning, and I received a message from the Home Office pathologist that the cause of the death was strangulation, but by what means the experts could not say. Poor old Jaffray, he was such an excellent fellow."

I LEFT Conway's flat early next morning, and arrived at Brennan's Buildings a good twenty minutes before Brandon's usual time of arrival. I examined the door of the vault and found the paste seals undisturbed. As I had thought, no attempt had been made on the previous night to gain admittance to the vault.

The day passed uneventfully. Brandon continued with the clearing up of his office and departed soon after five o'clock. Soon after Brandon had left the office door opened and Jevons walked in.

"Hello, Mr. Relph," he said., "Hard at work? I want you to spare a few minutes if you can to talk to me."

"Certainly, Inspector," I said. "What's the latest news?"

"Only another mysterious message," said Jevons. "I'm beginning to think that there are quite a lot of people interested in our business."

He passed to me an ordinary business envelope, with a typewritten address. "What do you think of that, Mr. Relph?" he asked. I examined the envelope. It was posted from West Kensington, and bore the date of the day before. The address, as I have said, was typewritten, and the envelope was addressed to Jevons at Scotland Yard. I opened the envelope and drew out a quarto sheet of typing paper on which these words were typed:

Dear Inspector Jevons,

Whilst having the greatest regard for your acumen, I think it extremely improbable that your search for Henri Zweitt will be successful. I think you will be much better advised to look for the Chinaman. Best wishes for your ultimate success.

Believe me.

Faithfully yours,

THE ONLOOKER.

I stared at the paper in amazement. Who was this new-comer to the mystery?

"It's pretty cool cheek, isn't it?" said Jevons.

"What are you going to do about it?" I asked.

"I'm going to do as he suggests," replied Jevons with a grin. "Mr. Relph, I think that note is sincere, and I'm going to act on it. It's quite on the cards that there is someone who knows more about this business than we do, and who is afraid to come out into the open with his information, and is therefore doing what he or she considers the next best thing. Of course, the whole thing may be a fake. Still, there's no harm in trying."

"I suppose it's not possible to find out who wrote this note," I asked.

"We might try," said Jevons, "but personally I think it would be a waste of time. We know that the letter was written on a Remington No. 10 machine, because of the distinctive type. The machine was a fairly old one, too. You will notice, if you look at the letter again, that the 'e' is very badly worn with constant use, and that half of the tails of the 'y's' are missing. Also the small 'c's are set in a peculiar angle. It would probably take ten years to round up that particular machine, and I don't think we've got the time," added Jevons facetiously.

We walked over to the typewriter which stood on the small table to the right of Zweitt's desk.

"This is a Remington No. 10," he said. "It's the typewriter which is used in most business houses, and there must be tens of thousands of them in existence."

He placed a piece of paper in the machine and commenced to type.

"It's fairly easy to tell the age of a typewriter by the condition of the type," continued Jevons. "This machine now—" he broke off suddenly.

"Good God, Mr. Relph! Come here? Look at this!"

I looked over his shoulder. Jevons had been tapping out a copy of the mysterious note, and the copy in the machine bore exactly the same characteristic faults in the type as the original. The letter to Jevons had been written on the Remington machine before us!

Jevons examined the copy again carefully.

"There's no possible mistake, Mr. Relph," he said. "That letter was written on this machine."

"Then it must have been written last night after I had gone," I said. "I was the last person on the premises—the doorkeeper waited to see me off. Some one came back here last night and typed that letter, and they were either concealed in the building or they were supplied with keys. Brandon's door was locked, and concealment in this office is impossible."

Jevons walked to the door and examined the Yale lock.

"This door has been opened, and with a 'spider,'" he said. "A 'spider,' Mr. Relph," he explained, "is an instrument used by crooks to open Yale locks. If you will examine this lock carefully you will see the faint scratches on the outside."

Jevons sat down in Zweitt's chair.

"Who could have written that letter?" he said.

It had occurred to me that the letter might have been written by Brandon, but Jevons' statement that the office door had been opened with a 'spider' dispelled this theory. Brandon could easily let himself into the building at any time he liked, and therefore it was unnecessary that he should force an entrance.

Jevons looked at the typewriter in perplexity.

"It seems to me," he said, "that we shall never get to the end of the business. No sooner do I make up my mind to work along one line than something turns up to upset my theories!"

He put on his hat and went off, looking thoroughly puzzled.

AFTER Jevons had gone I went upstairs and inspected the

other offices in the building.

It was just after seven o'clock and the place was empty, the cleaners having finished their work. Then I went down to the front entrance. The doorkeeper was just putting on his hat and coat.

"I shall be staying late to-night, Stevens," I said. "I've got some work to finish. I suppose I shall be able to get out all right."

"Oh, yes, sir," he answered. "The door is a self-locking one. Just give it a good pull, and it will be all right."

I said "good-night" to him and went upstairs. In a few minutes I heard the door bang after him. I was alone in the building. I had brought a packet of sandwiches and a flask with me, and I made a meal where I sat.

It was midnight before I moved from the office, when I removed Jaffray's automatic pistol from my hip pocket and slipped it in my right-hand coat pocket. Then I took my electric torch and moved over to the door. Very carefully I turned the door-handle, and pulled back the latch regulator, and commenced to open the door, inch by inch.

Outside the passage was in absolute darkness, except at the far end, where a small window let in a patch of silver moonlight, and there was not a sound to be heard. I slipped quietly into the passage, closing the door behind me, and, pulling it gently until I heard the lock click. I could reopen it if necessary with my key.

Then I tiptoed gently along to the head of the stairs and looked over the banister rail. There was a black void beneath me, but I knew that anyone attempting to reach the vault door down in the basement must pass immediately beneath where I stood at the head of the stairs. Not a sound came from below. After waiting for about fifteen minutes and hearing nothing I quietly descended the stairs, and, pushing open the door which led to the basement, made my way down to the vault door. I switched on my electric torch and examined the paste seals. They were still intact.

Suddenly I heard a slight noise—a peculiar scraping sound, which seemed to come from somewhere in the upper regions of the building. I switched off my torch and ascended once more to the first floor, and stood there listening. Perhaps the noise had only existed in my imagination, or, possibly, had been caused by a mouse or rat.

Just as I had come to this decision I heard it again—a weird sort of shuffling sound. There was no doubt that it came from somewhere above my head. I flattened myself against the left-hand wall of the corridor where the stairs led to the next floor. I reached the end of the corridor, and, edging past the splash of moonlight which came through the window, silently proceeded to mount the staircase to the second floor. As I neared the top of the stairs I heard the shuffling again, but this time it was much nearer. I flattened myself against the wainscoting by the side of the staircase and, with my pistol ready, waited. Nearer and nearer came the sound. I could not see a hand's breadth in front of me, but, it seemed that someone was approaching the top of the stairs and dragging a heavy weight along the ground behind him.

As the sound approached I retreated down the stairs, timing my silent steps as nearly as possible with those of the man above me. It was my intention to get to the bottom of the stairs where they curved round by the window and, remaining in the shadow of the curve, to let the mysterious unknown pass me and step into the moonlight with his burden.

After what seemed an eternity I reached the curve at the bottom of the stairs and flattened myself against the wall. Evidently the unknown had no notion of my presence, for he approached casually. I could hear him wheezing, whilst every step he took was accompanied by the bump of his burden falling from stair to stair. He came level with me—then passed me, so closely that I could have touched him with my hand. Then, as he moved into the splash of moonlight, I saw a short, stooping figure dragging a heavily laden sack behind him. As the moonlight fell upon his face I gave an involuntary start. It was the Chinaman!

FOR a moment I was tempted to spring out upon him, but this idea I dismissed as impracticable. It would be far better to see where he was going with his mysterious burden. He had by this time proceeded about ten yards down the corridor. I ascended a few steps and, gripping the banister rail, I lowered myself over the stairs and descended, hand over hand, until my feet touched the floor. In this way I missed the patch of moonlight at the bottom of the stairs, and found myself just behind the Chinaman once more.

Where was he going with his burden? He was so far advanced down the corridor that he must be going either to his own office, the front door, or down to the vault via the basement. I calculated that we were now about ten yards from the door of Brandon's office, and fifteen yards from the top of the stairs leading to the front entrance.

Suddenly there was silence—the Chinaman was not moving. Had he heard me? I crouched against the wall, every nerve strained to the uttermost in preparation for his spring. Nothing happened!

I waited for what seemed an interminable time, but what was in reality about five minutes. Still there was no movement. I crept noiselessly along the passage till I had reached the head of the stairs, then, with my pistol held ready, I flashed my electric torch down the corridor. It was empty! The Chinaman and the sack had disappeared!

I stood in amazement. Then I walked, down the corridor to the spot where I had last seen him. It was about twelve yards from the office door. How could he have disappeared—and where? On one side was a blank wall and on the other there was about fifteen feet of panelling leading along by the side of the stairs.

There could be one explanation only. There must be some secret way leading out of the passage.

I walked slowly down the corridor, examining the wall and the stair siding as well as I could, but I could find nothing out of the ordinary. I retraced my steps, and was considering whether I should let myself into the office, when I heard a slight sound beneath me. It seemed like the clang of metal. Suddenly it struck me that someone was opening the vault door. Could it be the Chinaman? How had he got downstairs without passing me at the stair top?

Very faintly I heard the sound again. I tiptoed quietly to the top of the stairs and looked over. All was quiet below. With my heart pumping with excitement I made my way down the stairs to the ground floor, where a quick examination of the front door showed me that the lock was intact. Then I noiselessly descended to the vault door. Switching on the torch I examined the paste seals. They were broken! I gently tried the lock on the door and gave the padlock which secured the locking-bar a gentle pull. It came off easily, The vault door was unlocked!