RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Apart for the names of the protagonists this story is almost identical with the Vulmea story "Swords of the Red Brotherhood." The manuscripts of both stories were found in Robert E. Howard's papers after his death. The order in which he wrote them is disputed. In his essay "The Trail Of Tranicos" (1967) L. Sprague de Camp wrote: "There is reason to believe that the pirate version came before the Conan one." On the other hand, Karl Edward Wagner, in his introduction to "The Black Stranger" in Echoes of Valour, claimed: "I have the photocopy of Howard's original manuscript of 'The Black Stranger', which clearly shows Howard's efforts to change the story from the Conan to the Black Vulmea version.

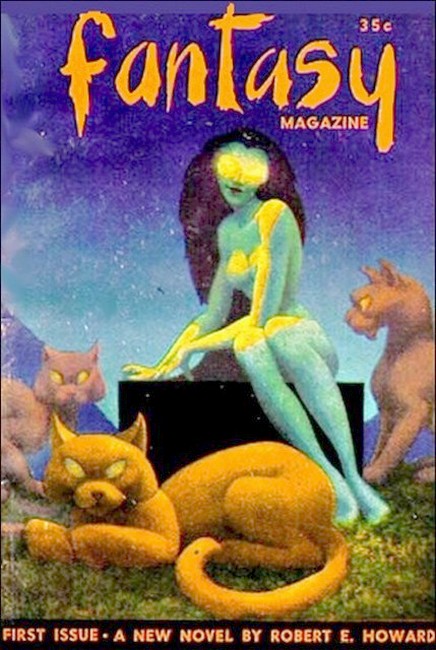

Fantasy Magazine, March 1953, with "The Black Stranger"

ONE moment the glade lay empty; the next, a man stood poised warily at the edge of the bushes. There had been no sound to warn the grey squirrels of his coming. But the gay-hued birds that flitted about in the sunshine of the open space took fright at his sudden appearance and rose in a clamoring cloud. The man scowled and glanced quickly back the way he had come, as if fearing their flight had betrayed his position to some one unseen. Then he stalked across the glade, placing his feet with care. For all his massive, muscular build he moved with the supple certitude of a panther.

He was naked except for a rag twisted about his loins, and his limbs were criss-crossed with scratches from briars, and caked with dried mud. A brown- crusted bandage was knotted about his thickly-muscled left arm. Under his matted black mane his face was drawn and gaunt, and his eyes burned like the eyes of a wounded panther. He limped slightly as he followed the dim path that led across the open space.

Halfway across the glade he stopped short and whirled, catlike, facing back the way he had come, as a long-drawn call quavered out across the forest. To another man it would have seemed merely the howl of a wolf. But this man knew it was no wolf. He was a Cimmerian and understood the voices of the wilderness as a city-bred man understands the voices of his friends.

Rage burned redly in his bloodshot eyes as he turned once more and hurried along the path, which, as it left the glade, ran along the edge of a dense thicket that rose in a solid clump of greenery among the trees and bushes. A massive log, deeply embedded in the grassy earth, paralleled the fringe of the thicket, lying between it and the path. When the Cimmerian saw this log he halted and looked back across the glade. To the average eye there were no signs to show that he had passed; but there was evidence visible to his wilderness-sharpened eyes, and therefore to the equally keen eyes of those who pursued him. He snarled silently, the red rage growing in his eyes—the berserk fury of a hunted beast which is ready to turn at bay.

He walked down the trail with comparative carelessness, here and there crushing a grass-blade beneath his foot. Then, when he had reached the further end of the great log, he sprang upon it, turned and ran lightly back along it. The bark had long been worn away by the elements. He left no sign to show the keenest forest- eyes that he had doubled on his trail. When he reached the densest point of the thicket he faded into it like a shadow, with hardly the quiver of a leaf to mark his passing.

The minutes dragged. The grey squirrels chattered again on the branches—then flattened their bodies and were suddenly mute. Again the glade was invaded. As silently as the first man had appeared, three other men materialized out of the eastern edge of the clearing. They were dark-skinned men of short stature, with thickly-muscled chests and arms. They wore beaded buckskin loin-cloths, and an eagle's feather was thrust into each black mane. They were painted in hideous designs, and heavily armed.

They had scanned the glade carefully before showing themselves in the open, for they moved out of the bushes without hesitation, in close single file, treading as softly as leopards, and bending down to stare at the path. They were following the trail of the Cimmerian, but it was no easy task even for these human bloodhounds. They moved slowly across the glade, and then one stiffened, grunted and pointed with his broad-bladed stabbing spear at a crushed grass-blade where the path entered the forest again. All halted instantly and their beady black eyes quested the forest walls. But their quarry was well hidden; they saw nothing to awake their suspicion, and presently they moved on, more rapidly, following the faint marks that seemed to indicate their prey was growing careless through weakness or desperation.

They had just passed the spot where the thicket crowded closest to the ancient trail when the Cimmerian bounded into the path behind them and plunged his knife between the shoulders of the last man. The attack was so quick and unexpected the Pict had no chance to save himself. The blade was in his heart before he knew he was in peril. The other two whirled with the instant, steel-trap quickness of savages, but even as his knife sank home, the Cimmerian struck a tremendous blow with the war-axe in his right hand. The second Pict was in the act of turning as the axe fell. It split his skull to the teeth.

The remaining Pict, a chief by the scarlet tip of his eagle-feather, came savagely to the attack. He was stabbing at the Cimmerian's breast even as the killer wrenched his axe from the dead man's head. The Cimmerian hurled the body against the chief and followed with an attack as furious and desperate as the charge of a wounded tiger. The Pict, staggering under the impact of the corpse against him, made no attempt to parry the dripping axe; the instinct to slay submerging even the instinct to live, he drove his spear ferociously at his enemy's broad breast. The Cimmerian had the advantage of a greater intelligence, and a weapon in each hand. The hatchet, checking its downward sweep, struck the spear aside, and the knife in the Cimmerian's left hand ripped upward into the painted belly.

An awful howl burst from the Pict's lips as he crumpled, disemboweled—a cry not of fear or of pain, but of baffled, bestial fury, the death-screech of a panther. It was answered by a wild chorus of yells some distance east of the glade. The Cimmerian started convulsively, wheeled, crouching like a wild thing at bay, lips asnarl, shaking the sweat from his face. Blood trickled down his forearm from under the bandage.

With a gasping, incoherent imprecation he turned and fled westward. He did not pick his way now, but ran with all the speed of his long legs, calling on the deep and all but inexhaustible reservoirs of endurance which are Nature's compensation for a barbaric existence. Behind him for a space the woods were silent, then a demoniacal howling burst out at the spot he had recently left, and he knew his pursuers had found the bodies of his victims. He had no breath for cursing the blood-drops that kept spilling to the ground from his freshly opened wound, leaving a trail a child could follow. He had thought that perhaps these three Picts were all that still pursued him of the war-party which had followed him for over a hundred miles. But he might have known these human wolves never quit a blood- trail.

The woods were silent again, and that meant they were racing after him, marking his path by the betraying blood-drops he could not check.

A wind out of the west blew against his face, laden with a salty dampness he recognized. Dully he was amazed. If he was that close to the sea the long chase had been even longer than he had realized. But it was nearly over. Even his wolfish vitality was ebbing under the terrible strain. He gasped for breath and there was a sharp pain in his side. His legs trembled with weariness and the lame one ached like the cut of a knife in the tendons each time he set the foot to earth. He had followed the instincts of the wilderness which bred him, straining every nerve and sinew, exhausting every subtlety and artifice to survive. Now in his extremity he was obeying another instinct, looking for a place to turn at bay and sell his life at a bloody price.

He did not leave the trail for the tangled depths on either hand. He knew that it was futile to hope to evade his pursuers now. He ran on down the trail while the blood pounded louder and louder in his ears and each breath he drew was a racking, dry- lipped gulp. Behind him a mad baying broke out, token that they were close on his heels and expected to overhaul their prey swiftly. They would come as fleet as starving wolves now, howling at every leap.

Abruptly he burst from the denseness of the trees and saw, ahead of him, the ground pitching upward, and the ancient trail winding up rocky ledges between jagged boulders. All swam before him in a dizzy red mist, but it was a hill he had come to, a rugged crag rising abruptly from the forest about its foot. And the dim trail wound up to a broad ledge near the summit.

That ledge would be as good a place to die as any. He limped up the trail, going on hands and knees in the steeper places, his knife between his teeth. He had not yet reached the jutting ledge when some forty painted savages broke from among the trees, howling like wolves.

At the sight of their prey their screams rose to a devil's crescendo, and they raced toward the foot of the crag, loosing arrows as they came. The shafts showered about the man who doggedly climbed upward, and one stuck in the calf of his leg. Without pausing in his climb he tore it out and threw it aside, heedless of the less accurate missiles which splintered on the rocks about him. Grimly he hauled himself over the rim of the ledge and turned about, drawing his hatchet and shifting knife to hand. He lay glaring down at his pursuers over the rim, only his shock of hair and blazing eyes visible. His chest heaved as he drank in the air in great shuddering gasps, and he clenched his teeth against a tendency toward nausea.

Only a few arrows whistled up at him. The horde knew its prey was cornered. The warriors came on howling, leaping agilely over the rocks at the foot of the hill, war-axes in their hand. The first to reach the crag was a brawny brave whose eagle feather was stained scarlet as a token of chieftainship. He halted briefly, one foot on the sloping trail, arrow notched and drawn halfway back, head thrown back and lips parted for an exultant yell. But the shaft was never loosed. He froze into motionlessness and the blood-lust in his black eyes gave way to a look of startled recognition. With a whoop he gave back, throwing his arms wide to check the rush of his howling braves. The man crouching on the ledge above them understood the Pictish tongue, but he was too far away to catch the significance of the staccato phrases snapped at the warriors by the crimson-feathered chief.

But all ceased their yelping, and stood mutely staring up—not at the man on the ledge, it seemed to him, but at the hill itself. Then without further hesitation, they unstrung their bows and thrust them into buckskin cases at their girdles; turned their backs and trotted across the open space, to melt into the forest without a backward look.

The Cimmerian glared in amazement. He knew the Pictish nature too well not to recognize the finality expressed in the departure. He knew they would not come back. They were heading for their villages, a hundred miles to the east.

But he could not understand it. What was there about his refuge that would cause a Pictish war-party to abandon a chase it had followed so long with all the passion of hungry wolves?

He knew there were sacred places, spots set aside as sanctuaries by the various clans, and that a fugitive, taking refuge in one of these sanctuaries, was safe from the clan which raised it. But the different tribes seldom respected sanctuaries of other tribes; and the men who had pursued him certainly had no sacred spots of their own in this region. They were the men of the Eagle, whose villages lay far to the east, adjoining the country of the Wolf-Picts. It was the Wolves who had captured him, in a foray against the Aquilonian settlements along Thunder River, and they had given him to the Eagles in return for a captured Wolf chief. The Eaglemen had a red score against the giant Cimmerian, and now it was redder still, for his escape had cost the life of a noted war- chief. That was why they had followed him so relentlessly, over broad rivers and hills and through the long leagues of gloomy forest, the hunting grounds of hostile tribes. And now the survivors of that long chase turned back when their enemy was run to earth and trapped. He shook his head, unable to understand it.

He rose gingerly, dizzy from the long grind, and scarcely able to realize that it was over. His limbs were stiff, his wounds ached. He spat dryly and cursed, rubbing his burning, bloodshot eyes with the back of his thick wrist. He blinked and took stock of his surroundings. Below him the green wilderness waved and billowed away and away in a solid mass, and above its western rim a steel-blue haze he knew hung over the ocean. The wind stirred his black mane, and the salt tang of the atmosphere revived him. He expanded his enormous chest and drank it in.

Then he turned stiffly and painfully about, growling at the twinge in his bleeding calf, and investigated the ledge whereon he stood. Behind it rose a sheer rocky cliff to the crest of the crag, some thirty feet above him. A narrow ladder-like stair of hand-holds had been niched into the rock. And a few feet from its foot there was a cleft in the wall, wide enough and tall enough for a man to enter.

He limped to the cleft, peered in, and grunted. The sun, hanging high above the western forest, slanted into the cleft, revealing a tunnel-like cavern beyond, and rested a revealing beam on the arch at which this tunnel ended. In that arch was set a heavy iron-bound oaken door!

This was amazing. This country was howling wilderness. The Cimmerian knew that for a thousand miles this western coast ran bare and uninhabited except by the villages of the ferocious sea-land tribes, who were even less civilized than their forest-dwelling brothers.

The nearest outposts of civilization were the frontier settlements along Thunder River, hundreds of miles to the east. The Cimmerian knew he was the only white man ever to cross the wilderness that lay between that river and the coast. Yet that door was no work of Picts.

Being unexplainable, it was an object of suspicion, and suspiciously he approached it, ax and knife ready. Then as his bloodshot eyes became more accustomed to the soft gloom that lurked on either side of the narrow shaft of sunlight, he noticed something else—thick iron-bound chests ranged along the walls. A blaze of comprehension came into his eyes. He bent over one, but the lid resisted his efforts. He lifted his hatchet to shatter the ancient lock, then changed his mind and limped toward the arched door. His bearing was more confident now, his weapons hung at his sides. He pushed against the ornately carven door and it swung inward without resistance.

Then his manner changed again, with lightning-like abruptness; he recoiled with a startled curse, knife and hatchet flashing as they leaped to positions of defense. An instant he poised there, like a statue of fierce menace, craning his massive neck to glare through the door. It was darker in the large natural chamber into which he was looking, but a dim glow emanated from the great jewel which stood on a tiny ivory pedestal in the center of the great ebony table about which sat those silent shapes whose appearance had so startled the intruder.

They did not move, they did not turn their heads toward him.

'Well,' he said harshly; 'are you all drunk?'

There was no reply. He was not a man easily abashed, yet now he felt disconcerted.

'You might offer me a glass of that wine you're swigging,' he growled, his natural truculence roused by the awkwardness of the situation. 'By Crom, you show damned poor courtesy to a man who's been one of your own brotherhood. Are you going to—' his voice trailed into silence, and in silence he stood and stared awhile at those bizarre figures sitting so silently about the great ebon table.

'They're not drunk,' he muttered presently. 'They're not even drinking. What devil's game is this?'

He stepped across the threshold and was instantly fighting for his life against the murderous, unseen fingers that clutched his throat.

BELESA idly stirred a sea-shell with a daintily slippered toe, mentally comparing its delicate pink edges to the first pink haze of dawn that rose over the misty beaches. It was not dawn now, but the sun was not long up, and the light, pearl-grey clouds which drifted over the waters had not yet been dispelled.

Belesa lifted her splendidly shaped head and stared out over a scene alien and repellent to her, yet drearily familiar in every detail. From her dainty feet the tawny sands ran to meet the softly lapping waves which stretched westward to be lost in the blue haze of the horizon. She was standing on the southern curve of the wide bay, and south of her the land sloped upward to the low ridge which formed one horn of that bay. From that ridge, she knew, one could look southward across the bare waters—into infinities of distance as absolute as the view to the westward and to the northward.

Glancing listlessly landward, she absently scanned the fortress which had been her home for the past year. Against a vague pearl and cerulean morning sky floated the golden and scarlet flag of her house—an ensign which awakened no enthusiasm in her youthful bosom, though it had flown trimphantly over many a bloody field in the far South. She made out the figures of men toiling in the gardens and fields that huddled near the fort, seeming to shrink from the gloomy rampart of the forest which fringed the open belt on the east, stretching north and south as far as she could see. She feared that forest, and that fear was shared by every one in that tiny settlement. Nor was it an idle fear—death lurked in those whispering depths, death swift and terrible, death slow and hideous, hidden, painted, tireless, unrelenting.

She sighed and moved listlessly toward the water's edge, with no set purpose in mind. The dragging days were all of one color, and the world of cities and courts and gaiety seemed not only thousands of miles but long ages away. Again she sought in vain for the reason that had caused a Count of Zingara to flee with his retainers to this wild coast, a thousand miles from the land that bore him, exchanging the castle of his ancestors for a hut of logs.

Her eyes softened at the light patter of small bare feet across the sands. A young girl came running over the low sandy ridge, quite naked, her slight body dripping, and her flaxen hair plastered wetly on her small head. Her wistful eyes were wide with excitement.

'Lady Belesa!' she cried, rendering the Zingaran words with a soft Ophirean accent. 'Oh, Lady Belesa!'

Breathless from her scamper, she stammered and made incoherent gestures with her hands. Belesa smiled and put an arm about the child, not minding that her silken dress came in contact with the damp, warm body. In her lonely, isolated life Belesa bestowed the tenderness of a naturally affectionate nature on the pitiful waif she had taken away from a brutal master encountered on that long voyage up from the southern coasts.

'What are you trying to tell me, Tina? Get your breath, child.'

'A ship!' cried the girl, pointing southward. 'I was swimming in a pool that the sea-tide left in the sand, on the other side of the ridge, and I saw it! A ship sailing up out of the south!'

She tugged timidly at Belesa's hand, her slender body all aquiver, and Belesa felt her own heart beat faster at the mere thought of an unknown visitor. They had seen no sail since coming to that barren shore.

Tina flitted ahead of her over the yellow sands, skirting the tiny pools the outgoing tide had left in shallow depressions. They mounted the low undulating ridge, and Tina poised there, a slender white figure against the clearing sky, her wet flaxen hair blowing about her thin face, a frail quivering arm outstretched.

'Look, my Lady!'

Belesa had already seen it—a billowing white sail, filled with the freshening south wind, beating up along the coast, a few miles from the point. Her heart skipped a beat. A small thing can loom large in colorless and isolated lives; but Belesa felt a premonition of strange and violent events. She felt that it was not by chance that this sail was beating up this lonely coast. There was no harbor town to the north, though one sailed to the ultimate shores of ice; and the nearest port to the south was a thousand miles away. What brought this stranger to lonely Korvela Bay?

Tina pressed close to her mistress, apprehension pinching her thin features.

'Who can it be, my Lady?' she stammered, the wind whipping color to her pale cheeks. 'Is it the man the Count fears?'

Belesa looked down at her, her brow shadowed.

'Why do you say that, child? How do you know my uncle fears anyone?'

'He must,' returned Tina naively, 'or he would never have come to hide in this lonely spot. Look, my Lady, how fast it comes!'

'We must go and inform my uncle,' murmured Belesa. 'The fishing boats have not yet gone out, and none of the men have seen that sail. Get your clothes, Tina. Hurry!'

The child scampered down the low slope to the pool where she had been bathing when she sighted the craft, and snatched up the slippers, tunic and girdle she had left lying on the sand. She skipped back up the ridge, hopping grotesquely as she donned her scanty garments in mid-flight.

Belesa, anxiously watching the approaching sail, caught her hand, and they hurried toward the fort.

A few moments after they had entered the gate of the log palisade which enclosed the building, the strident blare of the trumpet startled the workers in the gardens, and the men just opening the boat-house doors to push the fishing boats down their rollers to the water's edge.

Every man outside the fort dropped his tool or abandoned whatever he was doing and ran for the stockade without pausing to look about for the cause of the alarm. The straggling lines of fleeing men converged on the opened gate, and every head was twisted over its shoulder to gaze fearfully at the dark line of woodland to the east. Not one looked seaward.

They thronged through the gate, shouting questions at the sentries who patrolled the firing-ledges built below the up-jutting points of the upright palisade logs.

'What is it? Why are we called in? Are the Picts coming?'

For answer one taciturn man-at-arms in worn leathers and rusty steel pointed southward. From his vantage-point the sail was now visible. Men began to climb up on the ledges, staring toward the sea.

On a small lookout tower on the roof of the manor house, which was built of logs like the other buildings, Count Valenso watched the on-sweeping sail as it rounded the point of the southern horn. The Count was a lean, wiry man of medium height and late middle age. He was dark, somber of expression. Trunk-hose and doublet were of black silk, the only color about his costume the jewels that twinkled on his sword hilt, and the wine- colored cloak thrown carelessly over his shoulder. He twisted his thin black mustache nervously, and turned his gloomy eyes on his seneschal—a leather-featured man in steel and satin.

'What do you make of it, Galbro?'

'A carack,' answered the seneschal. 'It is a carack trimmed and rigged like a craft of the Barachan pirates—look there!'

A chorus of cries below them echoed his ejaculation; the ship had cleared the point and was slanting inward across the bay. And all saw the flag that suddenly broke forth from the masthead—a black flag, with a scarlet skull gleaming in the sun. The people within the stockade stared wildly at that dread emblem; then all eyes turned up toward the tower, where the master of the fort stood somberly, his cloak whipping about him in the wind.

'It's a Barachan, all right,' grunted Galbro. 'And unless I am mad, it's Strom's Red Hand. What is he doing on this naked coast?'

'He can mean no good for us,' growled the Count. A glance below showed him that the massive gates had been closed, and that the captain of his men-at-arms, gleaming in steel, was directing his men to their stations, some to the ledges, some to the tower loop-holes. He was massing his main strength along the western wall, in the midst of which was the gate.

Valenso had been followed into exile by a hundred men: soldiers, vassals and serfs. Of these some forty were men-at-arms, wearing helmets and suits of mail, armed with swords, axes and crossbows. The rest were toilers, without armor save for shirts of toughened leather, but they were brawny stalwarts, and skilled in the use of their hunting bows, woodsmen's axes, and boar-spears. They took their places, scowling at their hereditary enemies. The pirates of the Barachan Isles, a tiny archipelago off the southwestern coast of Zingara, had preyed on the people of the mainland for more than a century. The men on the stockade gripped their bows or boar-spears and stared somberly at the carack which swung inshore, its brass work flashing in the sun. They could see the figures swarming on the deck, and hear the lusty yells of the seamen. Steel twinkled along the rail.

The Count had retired from the tower, shooing his niece and her eager protegee before him, and having donned helmet and cuirass, he betook himself to the palisade to direct the defense. His subjects watched him with moody fatalism. They intended to sell their lives as dearly as they could, but they had scant hope of victory, in spite of their strong position. They were oppressed by a conviction of doom. A year on that naked coast, with the brooding threat of that devil-haunted forest looming for ever at their backs, had shadowed their souls with gloomy forebodings. Their women stood silently in the doorways of their huts, built inside the stockade, and quieted the clamor of their children.

Belesa and Tina watched eagerly from an upper window in the manor house, and Belesa felt the child's tense little body all aquiver within the crook of her protecting arm.

'They will cast anchor near the boat-house,' murmured Belesa. 'Yes! There goes their anchor, a hundred yards offshore. Do not tremble so, child! They can not take the fort. Perhaps they wish only fresh water and supplies. Perhaps a storm blew them into these seas.'

'They are coming ashore in long boats!' exclaimed the child. 'Oh, my Lady, I am afraid! They are big men in armor! Look how the sun strikes fire from their pikes and burgonets! Will they eat us?'

Belesa burst into laughter in spite of her apprehension.

'Of course not! Who put that idea into your head?'

'Zingelito told me the Barachans eat women.'

'He was teasing you. The Barachans are cruel, but they are no worse than the Zingaran renegades who call themselves buccaneers. Zingelito was a buccaneer once.'

'He was cruel,' muttered the child. 'I'm glad the Picts cut his head off.'

'Hush, child.' Belesa shuddered slightly. 'You must not speak that way. Look, the pirates have reached the shore. They line the beach, and one of them is coming toward the fort. That must be Strom.'

'Ahoy, the fort there!' came a hail in a voice gusty as the wind. 'I come under a flag of truce!'

The Count's helmeted head appeared over the points of the palisade; his stern face, framed in steel, surveyed the pirate somberly. Strom had halted just within good earshot. He was a big man, bare- headed, his tawny hair blowing in the wind. Of all the sea-rovers who haunted the Barachans, none was more famed for deviltry than he.

'Speak!' commanded Valenso. 'I have scant desire to converse with one of your breed.'

Strom laughed with his lips, not with his eyes.

'When your galleon escaped me in that squall off the Tralli-bes last year I never thought to meet you again on the Pictish Coast, Valenso!' said he. 'Although at the time I wondered what your destination might be. By Mitra, had I known, I would have followed you then! I got the start of my life a little while ago when I saw your scarlet falcon floating over a fortress where I had thought to see naught but bare beach. You have found it, of course?'

'Found what?' snapped the Count impatiently.

'Don't try to dissemble with me!' The pirate's stormy nature showed itself momentarily in a flash of impatience. 'I know why you came here—and I have come for the same reason. I don't intend to be balked. Where is your ship?'

'That is none of your affair.'

'You have none,' confidently asserted the pirate. 'I see pieces of a galleon's masts in that stockade. It must have been wrecked, somehow, after you landed here. If you'd had a ship you'd have sailed away with your plunder long ago.'

'What are you talking about, damn you?' yelled the Count. 'My plunder? Am I a Barachan to burn and loot? Even so, what would I loot on this naked coast?'

'That which you came to find,' answered the pirate coolly. 'The same thing I'm after—and mean to have. But I'll be easy to deal with—just give me the loot and I'll go my way and leave you in peace.'

'You must be mad,' snarled Valenso. 'I came here to find solitude and seclusion, which I enjoyed until you crawled out of the sea, you yellow-headed dog. Begone! I did not ask for a parley, and I weary of this empty talk. Take your rogues and go your ways.'

'When I go I'll leave that hovel in ashes!' roared the pirate in a transport of rage. 'For the last time—will you give me the loot in return for your lives? I have you hemmed in here, and a hundred and fifty men ready to cut your throats at my word.'

For answer the Count made a quick gesture with his hand below the points of the palisade. Almost instantly a shaft hummed venomously through a loop-hole and splintered on Strom's breastplate. The pirate yelled ferociously, bounded back and ran toward the beach, with arrows whistling all about him. His men roared and came on like a wave, blades gleaming in the sun.

'Curse you, dog!' raved the Count, felling the offending archer with his iron- clad fist. 'Why did you not strike his throat above the gorget? Ready with your bows, men—here they come!'

But Strom had reached his men, checked their headlong rush. The pirates spread out in a long line that overlapped the extremities of the western wall, and advanced warily, loosing their shafts as they came. Their weapon was the longbow, and their archery was superior to that of the Zingarans. But the latter were protected by their barrier. The long arrows arched over the stockade and quivered upright in the earth. One struck the window- sill over which Belesa watched, wringing a cry of fear from Tina, who cringed back, her wide eyes fixed on the venomous vibrating shaft.

The Zingarans sent their bolts and hunting arrows in return, aiming and loosing without undue haste. The women had herded the children into their huts and now stoically awaited whatever fate the gods had in store for them. The Barachans were famed for their furious and headlong style of battling, but they were wary as they were ferocious, and did not intend to waste their strength vainly in direct charges against the ramparts. They maintained their widespread formation, creeping along and taking advantage of every natural depression and bit of vegetation—which was not much, for the ground had been cleared on all sides of the fort against the threat of Pictish raids.

A few bodies lay prone on the sandy earth, back-pieces glinting in the sun, quarrel shafts standing up from arm-pit or neck. But the pirates were quick as cats, always shifting their position, and were protected by their light armor. Their constant raking fire was a continual menace to the men in the stockade. Still, it was evident that as long as the battle remained an exchange of archery, the advantage must remain with the sheltered Zingarans.

But down at the boat-house on the beach, men were at work with axes. The Count cursed sulphurously when he saw the havoc they were making among his boats, which had been built laboriously of planks sawn out of solid logs.

'They're making a mantlet, curse them!' he raged. 'A sally now, before they complete it—while they're scattered—' Galbro shook his head, glancing at the bare-armed henchmen with their clumsy pikes.

'Their arrows would riddle us, and we'd be no match for them in hand-to-hand fighting. We must keep behind our walls and trust to our archers.'

'Well enough,' growled Valenso. 'If we can keep them outside our walls.'

Presently the intention of the pirates became apparent to all, as a group of some thirty men advanced, pushing before them a great shield made out of the planks from the boats, and the timbers of the boat-house itself. They had found an ox-cart, and mounted the mantlet on the wheels, great solid disks of oak. As they rolled it ponderously before them it hid them from the sight of the defenders except for glimpses of their moving feet.

It rolled toward the gate, and the straggling line of archers converged toward it, shooting as they ran.

'Shoot!' yelled Valenso, going livid. 'Stop them before they reach the gate!'

A storm of arrows whistled across the palisade, and feathered themselves harmlessly in the thick wood. A derisive yell answered the volley. Shafts were finding loop-holes now, as the rest of the pirates drew nearer, and a soldier reeled and fell from the ledge, gasping and choking, with a clothyard shaft through his throat.

'Shoot at their feet!' screamed Valenso; and then—'Forty men at the gate with pikes and axes! The rest hold the wall!' Bolts ripped into the sand before the moving shield. A bloodthirsty howl announced that one had found its target beneath the edge, and a man staggered into view, cursing and hopping as he strove to withdraw the quarrel that skewered his foot. In an instant he was feathered by a dozen hunting arrows.

But, with a deep-throated shout, the mantlet was pushed to the wall, and a heavy, iron-tipped boom, thrust through an aperture in the center of the shield, began to thunder on the gate, driven by arms knotted with brawny muscles and backed with blood-thirsty fury. The massive gate groaned and staggered, while from the stockade bolts poured in a steady hail and some struck home. But the wild men of the sea were afire with the fighting- lust.

With deep shouts they swung the ram, and from all sides the others closed in, braving the weakened fire from the walls, and shooting fast and hard.

Cursing like a madman, the Count sprang from the wall and ran to the gate, drawing his sword. A clump of desperate men- at-arms closed in behind him, gripping their spears. In another moment the gate would cave in and they must stop the gap with their living bodies.

Then a new note entered the clamor of the melee. It was a trumpet, blaring stridently from the ship. On the cross-trees a figure waved his arms and gesticulated wildly.

That sound registered on Strom's ears, even as he lent his strength to the swinging ram. Exerting his mighty thews he resisted the surge of the other arms, bracing his legs to halt the ram on its backward swing. He turned his head, sweat dripping from his face.

'Wait!' he roared. 'Wait, damn you! Listen!'

In the silence that followed that bull's bellow, the blare of the trumpet was plainly heard, and a voice that shouted something unintelligible to the people inside the stockade.

But Strom understood, for his voice was lifted again in profane command. The ram was released, and the mantlet began to recede from the gate as swiftly as it had advanced.

'Look!' cried Tina at her window, jumping up and down in her wild excitement. 'They are running! All of them! They are running to the beach! Look! They have abandoned the shield just out of range! They are leaping into the boats and rowing for the ship! Oh, my Lady, have we won?'

'I think not!' Belesa was staring sea-ward. 'Look!'

She threw the curtains aside and leaned from the window. Her clear young voice rose above the amazed shouts of the defenders, turned their heads in the direction she pointed. They sent up a deep yell as they saw another ship swinging majestically around the southern point. Even as they looked she broke out the royal golden flag of Zingara.

Strom's pirates were swarming up the sides of their carack, heaving up the anchor. Before the stranger had progressed halfway across the bay, the Red Hand was vanishing around the point of the northern horn.

'OUT, quick!' snapped the Count, tearing at the bars of the gate. 'Destroy that mantlet before these strangers can land!'

'But Strom has fled,' expostulated Galbro, 'and yonder ship is Zingaran.'

'Do as I order!' roared Valenso. 'My enemies are not all foreigners! Out, dogs! Thirty of you, with axes, and make kindling wood of that mantlet. Bring the wheels into the stockade.'

Thirty axemen raced down toward the beach, brawny men in sleeveless tunics, their axes gleaming in the sun. The manner of their lord had suggested a possibility of peril in that oncoming ship, and there was panic in their haste. The splintering of the timbers under their flying axes came plainly to the people inside the fort, and the axemen were racing back across the sands, trundling the great oaken wheels with them, before the Zingaran ship had dropped anchor where the pirate ship had stood.

'Why does not the Count open the gate and go down to meet them?' wondered Tina. 'Is he afraid that the man he fears might be on that ship?'

'What do you mean, Tina?' Belesa demanded uneasily. The Count had never vouchsafed a reason for this self-exile. He was not the sort of a man to run from an enemy, though he had many. But this conviction of Tina's was disquieting; almost uncanny.

Tina seemed not to have heard her question.

'The axemen are back in the stockade,' she said. 'The gate is closed again and barred. The men still keep their places along the wall. If that ship was chasing Strom, why did it not pursue him? But it is not a war-ship. It is a carack, like the other. Look, a boat is coming ashore. I see a man in the bow, wrapped in a dark cloak.'

The boat having grounded, this man came pacing leisurely up the sands, followed by three others. He was a tall, wiry man, clad in black silk and polished steel.

'Halt!' roared the Count. 'I will parley with your leader alone!'

The taller stranger removed his morion and made a sweeping bow. His companions halted, drawing their wide cloaks about them, and behind them the sailors leaned on their oars and stared at the flag floating over the palisade.

When he came within easy call of the gate: 'Why surely,' said he, 'there should be no suspicion between gentlemen in these naked seas!'

Valenso stared at him suspiciously. The stranger was dark, with a lean, predatory face, and a thin black mustache. A bunch of lace was gathered at his throat, and there was lace on his wrists.

'I know you,' said Valenso slowly. 'You are Black Zarono, the buccaneer.'

Again the stranger bowed with stately elegance.

'And none could fail to recognize the red falcon of the Korzettas!'

'It seems this coast has become the rendezvous of all the rogues of the southern seas,' growled Valenso. 'What do you wish?'

'Come, come, sir!' remonstrated Zarono. 'This is a churlish greeting to one who has just rendered you a service. Was not that Argossean dog, Strom, just thundering at your gate? And did he not take to his sea-heels when he saw me round the point?'

'True,' grunted the Count grudgingly. 'Though there is little to choose between a pirate and a renegade.'

Zarono laughed without resentment and twirled his mustache.

'You are blunt in speech, my Lord. But I desire only leave to anchor in your bay, to let my men hunt for meat and water in your woods, and perhaps, to drink a glass of wine myself at your board.'

'I see not how I can stop you,' growled Valenso. 'But understand this, Zarono: no man of your crew comes within this palisade. If one approaches closer than a hundred feet, he will presently find an arrow through his gizzard. And I charge you do no harm to my gardens or the cattle in the pens. Three steers you may have for fresh meat, but no more. And we can hold this fort against your ruffians, in case you think otherwise.'

'You were not holding it very successfully against Strom,' the buccaneer pointed out with a mocking smile.

'You'll find no wood to build mantlets unless you chop down trees, or strip it from your own ship,' assured the Count grimly. 'And your men are not Barachan archers; they're no better bowmen than mine. Besides, what little loot you'd find in this castle would not be worth the price.'

'Who speaks of loot and warfare?' protested Zarono. 'Nay, my men are sick to stretch their legs ashore, and nigh to scurvy from chewing salt pork. I guarantee their good conduct. May they come ashore?'

Valenso grudgingly signified his consent, and Zarono bowed, a bit sardonically, and retired with a tread as measured and stately as if he trod the polished crystal floor of the Kordava royal court, where indeed, unless rumor lied, he had once been a familiar figure.

'Let no man leave the stockade,' Valenso ordered Galbro. 'I do not trust that renegade dog. Because he drove Strom from our gate is no guarantee that he would not cut our throats.'

Galbro nodded. He was well aware of the enmity which existed between the pirates and the Zingaran buccaneers. The pirates were mainly Argossean sailors, turned outlaw; to the ancient feud between Argos and Zingara was added, in the case of the freebooters, the rivalry of opposing interests. Both breeds preyed on the shipping and the coastal towns; and they preyed on one another with equal rapacity.

So no one stirred from the palisade while the buccaneers came ashore, dark-faced men in flaming silk and polished steel, with scarfs bound about their heads and gold hoops in their ears. They camped on the beach, a hundred and seventy-odd of them, and Valenso noticed that Zarono posted lookouts on both points. They did not molest the gardens, and only the three beeves designated by Valenso, shouting from the palisade, were driven forth and slaughtered. Fires were kindled on the strand, and a wattled cask of ale was brought ashore and broached.

Other kegs were filled with water from the spring that rose a short distance south of the fort, and men began to straggle toward the woods, crossbows in their hands. Seeing this, Valenso was moved to shout to Zarono, striding back and forth through the camp: 'Don't let your men go into the forest. Take another steer from the pens if you haven't enough meat. If they go trampling into the woods they may fall foul of the Picts.

'Whole tribes of the painted devils live back in the forest. We beat off an attack shortly after we landed, and since then six of my men have been murdered in the forest, at one time or another. There's peace between us just now, but it hangs by a thread. Don't risk stirring them up.'

Zarono shot a startled glance at the lowering woods, as if he expected to see hordes of savage figures lurking there. Then he bowed and said: 'I thank you for the warning, my Lord.' And he shouted for his men to come back, in a rasping voice that contrasted strangely with his courtly accents when addressing the Count.

If Zarono could have penetrated the leafy mask he would have been more apprehensive, if he could have seen the sinister figure that lurked there, watching the strangers with inscrutable black eyes—a hideously painted warrior, naked but for a doeskin breech-clout, with a toucan feather drooping over his left ear.

As evening drew on, a thin skim of gray crawled up from the sea-rim and overcast the sky. The sun sank in a wallow of crimson, touching the tips of the black waves with blood. Fog crawled out of the sea and lapped at the feet of the forest, curling about the stockade in smoky wisps. The fires on the beach shone dull crimson through the mist, and the singing of the buccaneers seemed deadened and far away. They had brought old sail-canvas from the carack and made them shelters along the strand, where beef was still roasting, and the ale granted them by their captain was doled out sparingly.

The great gate was shut and barred. Soldiers stolidly tramped the ledges of the palisade, pike on shoulder, beads of moisture glistening on their steel caps. They glanced uneasily at the fires on the beach, stared with greater fixity toward the forest, now a vague dark line in the crawling fog. The compound lay empty of life, a bare, darkened space. Candles gleamed feebly through the crack of the huts, and light streamed from the windows of the manor. There was silence except for the tread of the sentries, the drip of water from the eaves, and the distant singing of the buccaneers.

Some faint echo of this singing penetrated into the great hall where Valenso sat at wine with his unsolicited guest.

'Your men make merry, sir,' grunted the Count.

'They are glad to feel the sand under their feet again,' answered Zarono. 'It has been a wearisome voyage—yes, a long, stern chase.' He lifted his goblet gallantly to the unresponsive girl who sat on his host's right, and drank ceremoniously. Impassive attendants ranged the walls, soldiers with pikes and helmets, servants in satin coats. Valenso's household in this wild land was a shadowy reflection of the court he had kept in Kordava.

The manor house, as he insisted on calling it, was a marvel for that coast. A hundred men had worked night and day for months building it. Its log-walled exterior was devoid of ornamentation, but, within, it was as nearly a copy of Korzetta Castle as was possible. The logs that composed the walls of the hall were hidden with heavy silk tapestries, worked in gold. Ship beams, stained and polished, formed the beams of the lofty ceiling. The floor was covered with rich carpets. The broad stair that led up from the hall was likewise carpeted, and its massive balustrade had once been a galleon's rail.

A fire in the wide stone fireplace dispelled the dampness of the night. Candles in the great silver candelabrum in the center of the broad mahogany board lit the hall, throwing long shadows on the stair. Count Valenso sat at the head of that table, presiding over a company composed of his niece, his piratical guest, Galbro, and the captain of the guard. The smallness of the company emphasized the proportions of the vast board, where fifty guests might have sat at ease.

'You followed Strom?' asked Valenso. 'You drove him this far afield?'

'I followed Strom,' laughed Zarono, 'but he was not fleeing from me. Strom is not the man to flee from anyone. No; he came seeking for something; something I too desire.'

'What could tempt a pirate or a buccaneer to this naked land?' muttered Valenso, staring into the sparkling contents of his goblet.

'What could tempt a count of Kordava?' retorted Zarono, and an avid light burned an instant in his eyes.

'The rottenness of a royal court might sicken a man of honor,' remarked Valenso.

'Korzettas of honor have endured its rottenness with tranquillity for several generations,' said Zarono bluntly. 'My Lord, indulge my curiosity—why did you sell your lands, load your galleon with the furnishings of your castle and sail over the horizon out of the knowledge of the king and the nobles of Zingara? And why settle here, when your sword and your name might carve out a place for you in any civilized land?'

Valenso toyed with the golden seal-chain about his neck.

'As to why I left Zingara,' he said, 'that is my own affair. But it was chance that left me stranded here. I had brought all my people ashore, and much of the furnishings you mentioned, intending to build a temporary habitation. But my ship, anchored out there in the bay, was driven against the cliffs of the north point and wrecked by a sudden storm out of the west. Such storms are common enough at certain times of the year. After that there was naught to do but remain and make the best of it.'

'Then you would return to civilization, if you could?'

'Not to Kordava. But perhaps to some far clime—to Vendhya, or Khitai—'

'Do you not find it tedious here, my Lady?' asked Zarono, for the first time addressing himself directly to Belesa.

Hunger to see a new face and hear a new voice had brought the girl to the great hall that night. But now she wished she had remained in her chamber with Tina. There was no mistaking the meaning in the glance Zarono turned on her. His speech was decorous and formal, his expression sober and respectful; but it was but a mask through which gleamed the violent and sinister spirit of the man. He could not keep the burning desire out of his eyes when he looked at the aristocratic young beauty in her low-necked satin gown and jeweled girdle.

'There is little diversity here,' she answered in a low voice.

'If you had a ship,' Zarono bluntly asked his host, 'you would abandon this settlement?'

'Perhaps,' admitted the Count.

'I have a ship,' said Zarono. 'If we could reach an agreement—'

'What sort of an agreement?' Valenso lifted his head to stare suspiciously at his guest.

'Share and share alike,' said Zarono, laying his hand on the board with the fingers spread wide. The gesture was curiously reminiscent of a great spider. But the fingers quivered with curious tension, and the buccaneer's eyes burned with a new light.

'Share what?' Valenso stared at him in evident bewilderment. 'The gold I brought with me went down in my ship, and unlike the broken timbers, it did not wash ashore.'

'Not that!' Zarono made an impatient gesture. 'Let us be frank, my Lord. Can you pretend it was chance which caused you to land at this particular spot, with a thousand miles of coast from which to choose?'

'There is no need for me to pretend,' answered Valenso coldly. 'My ship's master was one Zingelito, formerly a buccaneer. He had sailed this coast, and persuaded me to land here, telling me he had a reason he would later disclose. But this reason he never divulged, because the day after we landed he disappeared into the woods, and his headless body was found later by a hunting party. Obviously he was ambushed and slain by the Picts.'

Zarono stared fixedly at Valenso for a space.

'Sink me,' quoth he at last, 'I believe you, my Lord. A Korzetta has no skill at lying, regardless of his other accomplishments. And I will make you a proposal. I will admit when I anchored out there in the bay I had other plans in mind. Supposing you to have already secured the treasure, I meant to take this fort by strategy and cut all your throats. But circumstances have caused me to change my mind—' He cast a glance at Belesa that brought the color into her face, and made her lift her head indignantly.

'I have a ship to carry you out of exile,' said the buccaneer, 'with your household and such of your retainers as you shall choose. The rest can fend for themselves.'

The attendants along the walls shot uneasy glances sidelong at each other. Zarono went on, too brutally cynical to conceal his intentions.

'But first you must help me secure the treasure for which I've sailed a thousand miles.'

'What treasure, in Mitra's name?' demanded the Count angrily. 'You are yammering like that dog Strom, now.'

'Did you ever hear of Bloody Tranicos, the greatest of the Barachan pirates?' asked Zarono.

'Who has not? It was he who stormed the island castle of the exiled prince Tothmekri of Stygia, put the people to the sword and bore off the treasure the prince had brought with him when he fled from Khemi.'

'Aye! And the tale of that treasure brought the men of the Red Brotherhood swarming like vultures after carrion—pirates, buccaneers, even the black corsairs from the South. Fearing betrayal by his captains, he fled northward with one ship, and vanished from the knowledge of men. That was nearly a hundred years ago.

'But the tale persists that one man survived that last voyage, and returned to the Barachans, only to be captured by a Zingaran war-ship. Before he was hanged he told his story and drew a map in his own blood, on parchment, which he smuggled somehow out of his captor's reach. This was the tale he told: Tranicos had sailed far beyond the paths of shipping, until he came to a bay on a lonely coast, and there he anchored. He went ashore, taking his treasure and eleven of his most trusted captains who had accompanied him on his ship. Following his orders, the ship sailed away, to return in a week's time, and pick up their admiral and his captains. In the meantime Tranicos meant to hide the treasure somewhere in the vicinity of the bay. The ship returned at the appointed time, but there was no trace of Tranicos and his eleven captains, except the rude dwelling they had built on the beach.

'This had been demolished, and there were tracks of naked feet about it, but no sign to show there had been any fighting. Nor was there any trace of the treasure, or any sign to show where it was hidden. The pirates plunged into the forest to search for their chief and his captains, but were attacked by wild Picts and driven back to their ship. In despair they heaved anchor and sailed away, but before they raised the Barachans, a terrific storm wrecked the ship and only that one man survived.

'That is the tale of the Treasure of Tranicos, which men have sought in vain for nearly a century. That the map exists is known, but its whereabouts have remained a mystery.

'I have had one glimpse of that map. Strom and Zingelito were with me, and a Nemedian who sailed with the Barachans. We looked upon it in a hovel in a certain Zingaran sea-port town, where we were skulking in disguise. Somebody knocked over the lamp, and somebody howled in the dark, and when we got the light on again, the old miser who owned the map was dead with a dirk in his heart, and the map was gone, and the night-watch was clattering down the street with their pikes to investigate the clamor. We scattered, and each went his own way.

'For years thereafter Strom and I watched one another, each supposing the other had the map. Well, as it turned out, neither had it, but recently word came to me that Strom had departed northward, so I followed him. You saw the end of that chase.

'I had but a glimpse at the map as it lay on the old miser's table, and could tell nothing about it. But Strom's actions show that he knows this is the bay where Tranicos anchored. I believe that they hid the treasure somewhere in that forest and returning, were attacked and slain by the Picts. The Picts did not get the treasure. Men have traded up and down this coast a little, knowing nothing of the treasure, and no gold ornament or rare jewel has ever been seen in the possession of the coastal tribes.

'This is my proposal: let us combine our forces. Strom is somewhere within striking distance. He fled because he feared to be pinned between us, but he will return. But allied, we can laugh at him. We can work out from the fort, leaving enough men here to hold it if he attacks. I believe the treasure is hidden near by. Twelve men could not have conveyed it far. We will find it, load it in my ship, and sail for some foreign port where I can cover my past with gold. I am sick of this life. I want to go back to a civilized land, and live like a noble, with riches, and slaves, and a castle—and a wife of noble blood.'

'Well?' demanded the Count, slit-eyed with suspicion.

'Give me your niece for my wife,' demanded the buccaneer bluntly.

Belesa cried out sharply and started to her feet. Valenso likewise rose, livid, his fingers knotting convulsively about his goblet as if he contemplated hurling it at his guest. Zarono did not move; he sat still, one arm on the table and the fingers hooked like talons. His eyes smoldered with passion, and a deep menace.

'You dare!' ejaculated Valenso.

'You seem to forget you have fallen from your high estate, Count Valenso,' growled Zarono. 'We are not at the Kordavan court, my Lord. On this naked coast nobility is measured by the power of men and arms. And there I rank you. Strangers tread Korzetta Castle, and the Korzetta fortune is at the bottom of the sea. You will die here, an exile, unless I give you the use of my ship.

'You will have no cause to regret the union of our houses. With a new name and a new fortune you will find that Black Zarono can take his place among the aristocrats of the world and make a son-in-law of which not even a Korzetta need be ashamed.'

'You are mad to think of it!' exclaimed the Count violently. 'You—who is that?'

A patter of soft-slippered feet distracted his attention. Tina came hurriedly into the hall, hesitated when she saw the Count's eyes fixed angrily on her, curtsied deeply, and sidled around the table to thrust her small hands into Belesa's fingers. She was panting slightly, her slippers were damp, and her flaxen hair was plastered down on her head.

'Tina!' exclaimed Belesa anxiously. 'Where have you been? I thought you were in your chamber, hours ago.'

'I was,' answered the child breathlessly, 'but I missed my coral necklace you gave me—' She held it up, a trivial trinket, but prized beyond all her other possessions because it had been Belesa's first gift to her. 'I was afraid you wouldn't let me go if you knew—a soldier's wife helped me out of the stockade and back again—please, my Lady, don't make me tell who she was, because I promised not to. I found my necklace by the pool where I bathed this morning. Please punish me if I have done wrong.'

'Tina!' groaned Belesa, clasping the child to her. 'I'm not going to punish you. But you should not have gone outside the palisade, with these buccaneers camped on the beach, and always a chance of Picts skulking about. Let me take you to your chamber and change these damp clothes—'

'Yes, my Lady,' murmured Tina, 'but first let me tell you about the black man—'

'What?' The startling interruption was a cry that burst from Valenso's lips. His goblet clattered to the floor as he caught the table with both hands. If a thunderbolt had struck him, the lord of the castle's bearing could not have been more subtly or horrifyingly altered. His face was livid, his eyes almost starting from his head.

'What did you say?' he panted, glaring wildly at the child who shrank back against Belesa in bewilderment. 'What did you say, wench?'

'A black man, my Lord,' she stammered, while Belesa, Zarono and the attendants stared at him in amazement. 'When I went down to the pool to get my necklace, I saw him. There was a strange moaning in the wind, and the sea whimpered like a thing in fear, and then he came. I was afraid, and hid behind a little ridge of sand. He came from the sea in a strange black boat with blue fire playing all about it, but there was no torch. He drew his boat up on the sands below the south point, and strode toward the forest, looking like a giant in the fog—a great, tall man, black like a Kushite—'

Valenso reeled as if he had received a mortal blow. He clutched at his throat, snapping the golden chain in his violence. With the face of a madman he lurched about the table and tore the child screaming from Belesa's arms.

'You little slut,' he panted. 'You lie! You have heard me mumbling in my sleep and have told this lie to torment me! Say you lie before I tear the skin from your back!'

'Uncle!' cried Belesa, in outraged bewilderment, trying to free Tina from his grasp. 'Are you mad? What are you about?'

With a snarl he tore her hand from his arm and spun her staggering into the arms of Galbro who received her with a leer he made little effort to disguise.

'Mercy, my Lord!' sobbed Tina. 'I did not lie!'

'I said you lied!' roared Valenso. 'Gebbrelo!'

The stolid serving man seized the trembling youngster and stripped her with one brutal wrench that tore her scanty garments from her body. Wheeling, he drew her slender arms over his shoulders, lifting her writhing feet clear of the floor.

'Uncle! shrieked Belesa, writhing vainly in Galbro's lustful grasp. 'You are mad! You can not—oh, you can not—!' The voice choked in her throat as Valenso caught up a jewel-hilted riding whip and brought it down across the child's frail body with a savage force that left a red weal across her naked shoulders.

Belesa moaned, sick with the anguish in Tina's shriek. The world had suddenly gone mad. As in a nightmare she saw the stolid faces of the soldiers and servants, beast-faces, the faces of oxen, reflecting neither pity nor sympathy. Zarono's faintly sneering face was part of the nightmare. Nothing in that crimson haze was real except Tina's naked white body, crisscrossed with red welts from shoulders to knees; no sound real except the child's sharp cries of agony, and the panting gasps of Valenso as he lashed away with the staring eyes of a madman, shrieking: 'You lie! You lie! Curse you, you lie! Admit your guilt, or I will flay your stubborn body! He could not have followed me here—'

'Oh, have mercy, my Lord!' screamed the child, writhing vainly on the brawny servant's back, too frantic with fear and pain to have the wit to save herself by a lie. Blood trickled in crimson beads down her quivering thighs. 'I saw him! I do not lie! Mercy! Please! Ahhhh!'

'You fool! You fool!' screamed Belesa, almost beside herself. 'Do you not see she is telling the truth? Oh, you beast! Beast! Beast!'

Suddenly some shred of sanity seemed to return to the brain of Count Valenso Korzetta. Dropping the whip he reeled back and fell up against the table, clutching blindly at its edge. He shook as with an ague. His hair was plastered across his brow in dank strands, and sweat dripped from his livid countenance which was like a carven mask of Fear. Tina, released by Gebbrelo, slipped to the floor in a whimpering heap. Belesa tore free from Galbro, rushed to her, sobbing, and fell on her knees, gathering the pitiful waif into her arms. She lifted a terrible face to her uncle, to pour upon him the full vials of her wrath—but he was not looking at her. He seemed to have forgotten both her and his victim. In a daze of incredulity, she heard him say to the buccaneer: 'I accept your offer, Zarono; in Mitra's name, let us find this accursed treasure and begone from this damned coast!'

At this the fire of her fury sank to sick ashes. In stunned silence she lifted the sobbing child in her arms and carried her up the stair. A glance backward showed Valenso crouching rather than sitting at the table, gulping wine from a huge goblet he gripped in both shaking hands, while Zarono towered over him like a somber predatory bird—puzzled at the turn of events, but quick to take advantage of the shocking change that had come over the Count. He was talking in a low, decisive voice, and Valenso nodded mute agreement, like one who scarcely heeds what is being said. Galbro stood back in the shadows, chin pinched between forefinger and thumb, and the attendants along the walls glanced furtively at each other, bewildered by their lord's collapse.

Up in her chamber Belesa laid the half-fainting girl on the bed and set herself to wash and apply soothing ointments to the weals and cuts on her tender skin. Tina gave herself up in complete submission to her mistress's hands, moaning faintly. Belesa felt as if her world had fallen about her ears. She was sick and bewildered, overwrought, her nerves quivering from the brutal shock of what she had witnessed. Fear of and hatred for her uncle grew in her soul. She had never loved him; he was harsh and apparently without natural affection, grasping and avid. But she had considered him just, and fearless. Revulsion shook her at the memory of his staring eyes and bloodless face. It was some terrible fear which had roused this frenzy; and because of this fear Valenso had brutalized the only creature she had to love and cherish; because of that fear he was selling her, his niece, to an infamous outlaw. What was behind this madness? Who was the black man Tina had seen?

The child muttered in semi-delirium.

'I did not lie, my Lady! Indeed I did not! It was a black man, in a black boat that burned like blue fire on the water! A tall man, black as a negro, and wrapped in a black cloak! I was afraid when I saw him, and my blood ran cold. He left his boat on the sands and went into the forest. Why did the Count whip me for seeing him?'

'Hush, Tina,' soothed Belesa. 'Lie quiet. The smarting will soon pass.'

The door opened behind her and she whirled, snatching up a jeweled dagger. The Count stood in the door, and her flesh crawled at the sight. He looked years older; his face was grey and drawn, and his eyes stared in a way that roused fear in her bosom. She had never been close to him; now she felt as though a gulf separated them. He was not her uncle who stood there, but a stranger come to menace her.

She lifted the dagger.

'If you touch her again,' she whispered from dry lips, 'I swear before Mitra I will sink this blade in your breast.' He did not heed her.

'I have posted a strong guard about the manor,' he said. 'Zarono brings his men into the stockade tomorrow. He will not sail until he has found the treasure. When he finds it we shall sail at once for some port not yet decided upon.'

'And you will sell me to him?' she whispered. 'In Mitra's name—'

He fixed upon her a gloomy gaze in which all considerations but his own self-interest had been crowded out. She shrank before it, seeing in it the frantic cruelty that possessed the man in his mysterious fear.

'You will do as I command,' he said presently, with no more human feeling in his voice than there is in the ring of flint on steel. And turning, he left the chamber. Blinded by a sudden rush of horror, Belesa fell fainting beside the couch where Tina lay.

BELESA never knew how long she lay crushed and senseless. She was first aware of Tina's arms about her and the sobbing of the child in her ear. Mechanically she straightened herself and drew the girl into her arms; and she sat there, dry-eyed, staring unseeingly at the flickering candle. There was no sound in the castle. The singing of the buccaneers on the strand had ceased. Dully, almost impersonally she reviewed her problem.

Valenso was mad, driven frantic by the story of the mysterious black man. It was to escape this stranger that he wished to abandon the settlement and flee with Zarono. That much was obvious. Equally obvious was the fact that he was ready to sacrifice her in exchange for that opportunity to escape. In the blackness of spirit which surrounded her she saw no glint of light. The serving men were dull or callous brutes, their women stupid and apathetic. They would neither dare nor care to help her. She was utterly helpless.

Tina lifted her tear-stained face as if she were listening to the prompting of some inner voice. The child's understanding of Belesa's inmost thoughts was almost uncanny, as was her recognition of the inexorable drive of Fate and the only alternative left to the weak.

'We must go, my Lady!' she whispered. 'Zarono shall not have you. Let us go far away into the forest. We shall go until we can go no further, and then we shall lie down and die together.'

The tragic strength that is the last refuge of the weak entered Belesa's soul. It was the only escape from the shadows that had been closing in upon her since that day when they fled from Zingara.

'We shall go, child.'

She rose and was fumbling for a cloak, when an exclamation from Tina brought her about. The girl was on her feet, a finger pressed to her lips, her eyes wide and bright with terror.

'What is it, Tina?' The child's expression of fright induced Belesa to pitch her voice to a whisper, and a nameless apprehension crawled over her.

'Someone outside in the hall,' whispered Tina, clutching her arm convulsively. 'He stopped at our door, and then went on, toward the Count's chamber at the other end.'

'Your ears are keener than mine,' murmured Belesa. 'But there is nothing strange in that. It was the Count himself, perchance, or Galbro.'

She moved to open the door, but Tina threw her arms frantically about her neck, and Belesa felt the wild beating of her heart.

'No, no, my Lady! Do not open the door! I am afraid! I do not know why, but I feel that some evil thing is skulking near us!'

Impressed, Belesa patted her reassuringly, and reached a hand toward the gold disk that masked the tiny peep-hole in the center of the door.

'He is coming back!' shivered the girl. 'I hear him!'

Belesa heard something too—a curious stealthy pad which she knew, with a chill of nameless fear, was not the step of anyone she knew. Nor was it the step of Zarono, or any booted man. Could it be the buccaneer gliding along the hallway on bare, stealthy feet, to slay his host while he slept? She remembered the soldiers who would be on guard below. If the buccaneer had remained in the manor for the night, a man-at-arms would be posted before his chamber door. But who was that sneaking along the corridor? None slept upstairs besides herself, Tina and the Count, except Galbro.

With a quick motion she extinguished the candle so it would not shine through the hole in the door, and pushed aside the gold disk. All the lights were out in the hall, which was ordinarily lighted by candles. Someone was moving along the darkened corridor. She sensed rather than saw a dim bulk moving past her doorway, but she could make nothing of its shape except that it was man-like. But a chill wave of terror swept over her; so she crouched dumb, incapable of the scream that froze behind her lips. It was not such terror as her uncle now inspired in her, or fear like her fear of Zarono, or even of the brooding forest. It was blind unreasoning terror that laid an icy hand on her soul and froze her tongue to her palate.

The figure passed on to the stairhead, where it was limned momentarily against the faint glow that came up from below, and at the glimpse of that vague black image against the red, she almost fainted. She crouched there in the darkness, awaiting the outcry that would announce that the soldiers in the great hall had seen the intruder. But the manor remained silent; somewhere a wind wailed shrilly. That was all.

Belesa's hands were moist with perspiration as she groped to relight the candle. She was still shaken with horror, though she could not decide just what there had been about that black figure etched against the red glow that had roused this frantic loathing in her soul. It was man-like in shape, but the outline was strangely alien—abnormal—though she could not clearly define that abnormality. But she knew that it was no human being that she had seen, and she knew that the sight had robbed her of all her new-found resolution. She was demoralized, incapable of action.

The candle flared up, limning Tina's white face in the yellow glow.

'It was the black man!' whispered Tina. 'I know! My blood turned cold, just as it did when I saw him on the beach. There are soldiers downstairs; why did they not see him? Shall we go and inform the Count?'

Belesa shook her head. She did not care to repeat the scene that had ensued upon Tina's first mention of the black man. At any event, she dared not venture out into that darkened hallway.

'We dare not go into the forest!' shuddered Tina. 'He will be lurking there—'

Belesa did not ask the girl how she knew the black man would be in the forest; it was the logical hiding-place for any evil thing, man or devil. And she knew Tina was right; they dared not leave the fort now. Her determination, which had not faltered at the prospect of certain death, gave way at the thought of traversing those gloomy woods with that black shambling creature at large among them. Helplessly she sat down and sank her face in her hands.

Tina slept, presently, on the couch, whimpering occasionally in her sleep. Tears sparkled on her long lashes. She moved her smarting body uneasily in her restless slumber. Toward dawn Belesa was aware of a stifling quality in the atmosphere. She heard a low rumble of thunder somewhere off to sea-ward. Extinguishing the candle, which had burned to its socket, she went to a window whence she could see both the ocean and a belt of the forest behind the fort.

The fog had disappeared, but out to sea a dusky mass was rising from the horizon. From it lightning flickered and the low thunder growled. An answering rumble came from the black woods. Startled, she turned and stared at the forest, a brooding black rampart. A strange rhythmic pulsing came to her ears—a droning reverberation that was not the roll of a Pictish drum.

'The drum!' sobbed Tina, spasmodically opening and closing her fingers in her sleep. 'The black man—beating on a black drum—in the black woods! Oh, save us—!'

Belesa shuddered. Along the eastern horizon ran a thin white line that presaged dawn. But that black cloud on the western rim writhed and billowed, swelling and expanding. She stared in amazement, for storms were practically unknown on that coast at that time of the year, and she had never seen a cloud like that one.

It came pouring up over the world-rim in great boiling masses of blackness, veined with fire. It rolled and billowed with the wind in its belly. Its thundering made the air vibrate. And another sound mingled awesomely with the reverberations of the thunder—the voice of the wind, that raced before its coming. The inky horizon was torn and convulsed in the lightning flashes; afar to sea she saw the white-capped waves racing before the wind. She heard its droning roar, increasing in volume as it swept shoreward. But as yet no wind stirred on the land. The air was hot, breathless. There was a sensation of unreality about the contrast: out there wind and thunder and chaos sweeping inland; but here stifling stillness. Somewhere below her a shutter slammed, startling in the tense silence, and a woman's voice was lifted, shrill with alarm. But most of the people of the fort seemed sleeping, unaware of the oncoming hurricane.

She realized that she still heard that mysterious droning drum-beat and she stared toward the black forest, her flesh crawling. She could see nothing, but some obscure instinct or intuition prompted her to visualize a black hideous figure squatting under black branches and enacting a nameless incantation on something that sounded like a drum—

Desperately she shook off the ghoulish conviction, and looked sea-ward, as a blaze of lightning fairly split the sky. Outlined against its glare she saw the masts of Zarono's ship; she saw the tents of the buccaneers on the beach, the sandy ridges of the south point and the rock cliffs of the north point as plainly as by midday sun. Louder and louder rose the roar of the wind, and now the manor was awake. Feet came pounding up the stair, and Zarono's voice yelled, edged with fright.

Doors slammed and Valenso answered him, shouting to be heard above the roar of the elements.

'Why didn't you warn me of a storm from the west?' howled the buccaneer. 'If the anchors don't hold—'

'A storm never came from the west before, at this time of year!' shrieked Valenso, rushing from his chamber in his nightshirt, his face livid and his hair standing stiffly on end. 'This is the work of—' His words were drowned as he raced madly up the ladder that led to the lookout tower, followed by the swearing buccaneer.

Belesa crouched at her window, awed and deafened. Louder and louder rose the wind, until it drowned all other sound—all except that maddening droning that now rose like an inhuman chant of triumph. It roared inshore, driving before it a foaming league-long crest of white—and then all hell and destruction was loosed on that coast. Rain fell in driving torrents, sweeping the beaches with blind frenzy. The wind hit like a thunder-clap, making the timbers of the fort quiver. The surf roared over the sands, drowning the coals of the fires the seamen had built. In the glare of lightning Belesa saw, through the curtain of the slashing rain, the tents of the buccaneers whipped to ribbons and washed away, saw the men themselves staggering toward the fort, beaten almost to the sands by the fury of torrent and blast.

And limned against the blue glare she saw Zarono's ship, ripped loose from her moorings, driven headlong against the jagged cliffs that jutted up to receive her....

THE storm had spent its fury. Full dawn rose in a clear blue rain-washed sky. As the sun rose in a blaze of fresh gold, bright-hued birds lifted a swelling chorus from the trees on whose broad leaves beads of water sparkled like diamonds, quivering in the gentle morning breeze.

At a small stream which wound over the sands to join the sea, hidden beyond a fringe of trees and bushes, a man bent to lave his hands and face. He performed his ablutions after the manner of his race, grunting lustily and splashing like a buffalo. But in the midst of these splashing he lifted his head suddenly, his tawny hair dripping and water running in rivulets over his brawny shoulders. He crouched in a listening attitude for a split second, then was on his feet and facing inland, sword in hand, all in one motion. And there he froze, glaring wide-mouthed.

A man as big as himself was striding toward him over the sands, making no attempt at stealth; and the pirate's eyes widened as he stared at the close-fitting silk breeches, high flaring-topped boots, wide-skirted coat and head-gear of a hundred years ago. There was a broad cutlass in the stranger's hand and unmistakable purpose in his approach.

The pirate went pale, as recognition blazed in his eyes.

'You!' he ejaculated unbelievingly. 'By Mitra! You!'