Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

Maclean's, 1 March 1923, with

"The Horror at Stavely Grange"

"The Saving Clause," Hodder and Stoughton Ltd, London, 1927

with "The Horror at Stavely Grange"

"A FACT pointing in a certain direction is just a fact: two pointing in the same direction become a coincidence: three—and you begin to get into the regions of certainty. But you must be very sure of your facts."

Thus ran Ronald Standish's favourite dictum: and it was the astonishing skill with which he seemed to be able to sort out the facts that mattered from the mass of irrelevant detail, and having sorted them out, to interpret them correctly, that had earned him his reputation as a detective of quite unusual ability.

There is no doubt that had he been under the necessity of earning his own livelihood, he would have risen to a very high position at Scotland Yard; or, if he had chosen to set up on his own, that his career would have been assured. But not being under any such necessity, his gifts were known only to a small circle of friends and acquaintances. Moreover, he was apt to treat the matter as rather a joke—as an interesting recreation more than a serious business. He regarded it in much the same light as solving a chess problem or an acrostic.

In appearance he was about as unlike the conventional detective as it is possible to be. Of medium height, he was inclined to be thick-set. His face was ruddy, with a short, closely-clipped moustache—and in his eyes there shone a perpetual twinkle. In fact most people on first meeting him took him for an Army officer. He was a first-class man to hounds, and an excellent shot; a cricketer who might easily have become first class had he devoted enough time to it, and a scratch golfer. And last, but not least, he was a man of very great personal strength without a nerve in his body.

This, then, was the man who sat opposite to me in a first-class carriage of a Great Western express on the way to Devonshire. On the spur of the moment that morning, I had rung him up at his club in London—on the spur of the moment he had thrown over a week's cricket, and arranged to come with me to Exeter. And now that we were actually in the train, I began to wonder if I had brought him on a wild-goose chase. I took the letter out of my pocket—the letter that had been the cause of our journey, and read it through once again.

"Dear Tony," it ran, "I am perfectly distracted with worry and anxiety. I don't know whether you saw it in the papers, and it's such ages since we met, but I'm engaged to Billy Mansford. And we're in the most awful trouble. Haven't you got a friend or someone you once told me about who solves mysteries and things? Do, for pity's sake, get hold of him and bring him down here to stay I'm nearly off my head with it all—Your distracted Molly."

I laid the letter on my knee and stared out of the window. Somehow or other I couldn't picture pretty little Molly Tremayne, the gayest and most feckless girl in the world, as being off her head over anything. And having only recently returned from Brazil I had not heard of her engagement—nor did I know anything about the man she was engaged to. But as I say, I rang up Standish on the spur of the moment, and a little to my surprise he had at once accepted.

He leant over at that moment, and took the letter off my knee.

"The Old Hall," he remarked thoughtfully. Then he took a big-scale ordnance map from his pocket and began to study it.

"Three miles approximately from Staveley Grange."

"Staveley Grange," I said, staring at him. "What has Staveley Grange got to do with the matter?"

"I should imagine—everything," he answered. "You've been out of the country, Tom, and so you're a bit behindhand. But you may take it from me that it was not the fact that your Molly was distracted that made me give up an excellent I.Z. tour. It was the fact that she is engaged to Mr. William Mansford."

"Never heard of him," I said. "Who and what is he?"

"He is the younger and only surviving son of the late Mr. Robert Mansford," he answered thoughtfully. "Six months ago the father was alive—also Tom, the elder son. Five months ago the father died: two months ago Tom died. And the circumstances of their deaths were, to put it mildly, peculiar."

"Good heavens!" I cried, "this is all news to me."

"Probably," he answered. "The matter attracted very little attention. But you know my hobby, and it was the coincidence of the two things that attracted my attention. I only know, of course, what appeared in the papers—and that wasn't very much. Mansford senior and both his sons had apparently spent most of their lives in Australia. The two boys came over with the Anzacs, and a couple of years or so after the war they all decided to come back to England. And so he bought Staveley Grange. He had gone a poor man of distinctly humble origin: he returned as a wealthy Australian magnate. Nine months after he stepped into the house he was found dead in his bed in the morning by the butler. He was raised up on his pillows and he was staring fixedly at a top corner of the room by one of the windows. And in his hand he held the speaking tube which communicated with the butler's room. A post-mortem revealed nothing, and the verdict was that he had died of heart failure. In view of the fact that most people do die of heart failure, the verdict was fairly safe."

Ronald Standish lit a cigarette.

"That was five months ago. Two months ago, one of the footmen coming in in the morning was horrified to find Tom sprawling across the rail at the foot of the bed—stone dead He had taken over his father's room, and had retired the previous night in the best of health and spirits. Again there was a post-mortem—again nothing was revealed, And again the same verdict was given—heart failure. Of course, the coincidence was commented on in the press, but there the matter rested, at any rate as far as the newspapers were concerned. And therefore that is as much as I know. This letter looks as if further developments were taking place."

"What an extraordinary affair," I remarked, as he finished. "What sort of men physically were the father and Tom?"

"According to the papers," answered Standish, "they were two singularly fine specimens. Especially Tom."

Already we were slowing down for Exeter, and we began gathering our suitcases and coats preparatory to alighting. I leant out of the window as we ran into the station, having wired Molly our time of arrival, and there she was sure enough, with a big, clean-cut man standing beside her, who, I guessed, must be her fiance. So, in fact, it proved, and a moment or two later we all walked out of the station together towards the waiting motor car. And it was as I passed the ticket collector that I got the first premonition of trouble. Two men standing on the platform, who looked like well-to-do farmers, whispered together a little significantly as Mansford passed them, and stared after him with scarcely veiled hostility in their eyes.

A moment or two later we all walked out of

the station together towards the waiting motor

car.

On the way to the Old Hall, I studied him under cover of some desultory conversation with Molly. He was a typical Australian of the best type: one of those open-air, clear-eyed men who came over in their thousands to Gallipoli and France. But it seemed to me that his conversation with Ronald was a little forced: underlying it was a vague uneasiness—a haunting fear of something or other. And I thought he was studying my friend with a kind of desperate hope tinged with disappointment, as if he had been building on Ronald's personality and now was unsatisfied.

That some such idea was in Molly's mind I learned as we got out of the car. For a moment or two we were alone, and she turned to me with a kind of desperate eagerness.

"Is he very clever, Tom—your friend? Somehow I didn't expect him to look quite like that!"

"You may take it from me, Molly," I said reassuringly, "that there are very few people in Europe who can see further into a brick wall than Ronald. But he knows nothing, of course, as to what the trouble is—any more than I do. And you mustn't expect him to work miracles."

"Of course not," she answered. "But oh! Tom—it's—it's damnable."

We went into the house and joined Standish and Mansford, who were in the hall.

"You'd like to go up to your rooms," began Molly, but Ronald cut her short with a grave smile.

"I think, Miss Tremayne," he said quietly, "that it will do you both good to get this little matter off your chests as soon as possible. Bottling things up is no good, and there's some time yet before dinner."

The girl gave him a quick smile of gratitude and led the way across the hall.

"Let's go into the billiard room," she said. "Daddy is pottering round the garden, and you can meet him later. Now, Billy," she continued, when we were comfortably settled, "tell Mr. Standish all about it."

"Right from the very beginning, please," said Ronald, stuffing an empty pipe in his mouth. "The reasons that caused your father to take Staveley Grange and everything."

Bill Mansford gave a slight start.

"You know something about us already then."

"Something," answered Ronald briefly. "I want to know all."

"Well," began the Australian. "I'll tell you all I know. But there are many gaps I can't fill in. When we came back from Australia two years ago, we naturally gravitated to Devonshire. My father came from these parts, and he wanted to come back after his thirty years' absence. Of course he found everything changed, but he insisted on remaining here and we set about looking for a house. My father was a wealthy man—very wealthy, and his mind was set on getting something good. A little pardonable vanity perhaps—but having left England practically penniless to return almost a millionaire—he was determined to get what he wanted regardless of cost. And it was after we had been here about six months that Staveley Grange came quite suddenly on to the market. It happened in rather a peculiar way. Some people of the name of Bretherton had it, and had been living there for about three years. They had bought it, and spent large sums of money on it: introduced a large number of modern improvements, and at the same time preserved all the old appearance. Then as I say, quite suddenly, they left the house and threw it on the market.

"Well, it was just what we wanted. We all went over it, and found it even more perfect than we had anticipated. The man who had been butler to the Brethertons was in charge, and when we went over, he and his wife were living there alone. We tried to pump them as to why the Brethertons had gone, but they appeared to know no more than we did. The butler—Templeton—was a charming old bird with side-whiskers; his wife, who had been doing cook, was a rather timorous-looking little woman—but a damned good cook.

"Anyway, the long and short of it was, we bought the place. The figure was stiff, but my father could afford it. And it was not until we bought it, that we heard in a roundabout way the reason of the Brethertons' departure. It appeared that old Mrs. Bretherton woke up one night in screaming hysterics, and alleged that a dreadful thing was in the room with her. What it was she wouldn't say, except to babble foolishly about a shining, skinny hand that had touched her. Her husband and various maids came rushing in, and of course the room was empty. There was nothing there at all. The fact of it was that the old lady had had lobster for dinner—and a nightmare afterwards."

"At least," added Mansford slowly, "that's what we thought at the time."

He paused to light a cigarette.

"Well—we gathered that nothing had been any good. Templeton proved a little more communicative once we were in, and from him we found out, that in spite of every argument and expostulation on the part of old Bretherton, the old lady flatly refused to live in the house for another minute. She packed up her boxes and went off the next day with her maid to some hotel in Exeter, and nothing would induce her to set foot inside the house again. Old Bretherton was livid."

Mansford smiled grimly.

"But—he went, and we took the house. The room that old Mrs. Bretherton had had was quite the best bedroom in the house, and my father decided to use it as his own. He came to that decision before we knew anything about this strange story, though even if we had, he'd still have used the room. My father was not the man to be influenced by an elderly woman's indigestion and subsequent nightmare. And when bit by bit we heard the yarn, he merely laughed, as did my brother and myself.

"And then one morning it happened. It was Templeton who broke the news to us with an ashen face, and his voice shaking so that we could hardly make out what he said. I was shaving at the time, I remember, and when I'd taken in what he was trying to say, I rushed along the passage to my father's room with the soap still lathered on my chin. The poor old man was sitting up in bed propped against the pillows. His left arm was flung half across his face as if to ward off something that was coming: his right hand was grasping the speaking-tube beside the bed. And in his wide-open, staring eyes was a look of dreadful terror."

He paused as if waiting for some comment or question, but Ronald still sat motionless, with his empty pipe in his mouth. And after a while Mansford continued:

"There was a post-mortem, as perhaps you may have seen in the papers, and they found my father had died from heart failure. But my father's heart, Mr. Standish, was as sound as mine, and neither my brother nor I were satisfied. For weeks he and I sat up in that room, taking it in turns to go to sleep, to see if we could see anything—but nothing happened. And at last we began to think that the verdict was right, and that the poor old man had died of natural causes. I went back to my own room, and Tom—my brother—stayed on in my father's room. I tried to dissuade him, but he was an obstinate fellow, and he had an idea that if he slept there alone he might still perhaps get to the bottom of it. He had a revolver by his side, and Tom was a man who could hit the pip out of the ace of diamonds at ten yards. Well, for a week nothing happened. And then one night I stayed chatting with him for a few moments in his room before going to bed. That was the last time I saw him alive. One of the footmen came rushing in to me the next morning, with a face like a sheet—and before he spoke I knew what must have happened. It was perhaps a little foolish of me—but I dashed past him while he was still stammering at the door—and went to my brother's room."

"Why foolish?" said Standish quietly.

"Some people at the inquest put a false construction on it," answered Mansford steadily. "They wanted to know why I made that assumption before the footman told me."

"I see," said Standish. "Go on."

"I went into the room, and there I found him. In one hand he held the revolver, and he was lying over the rail at the foot of the bed. The blood had gone to his head, and he wasn't a pretty sight. He was dead, of course—and once again the post-mortem revealed nothing. He also was stated to have died of heart failure. But he didn't, Mr. Standish."

Mansford's voice shook a little. "As there's a God above, I swear Tom never died of heart failure. Something happened in that room—something terrible occurred there which killed my father and brother as surely as a bullet through the brain. And I've got to find out what it was: I've got to, you understand—because,"—and here his voice faltered for a moment, and then grew steady again—"because there are quite a number of people who suspect me of having murdered them both."

"Naturally," said Standish, in his most matter-of-fact tone. "When a man comes into a lot of money through the sudden death of two people, there are certain to be lots of people who will draw a connection between the two events."

He stood up and faced Mansford.

"Are the police still engaged on it?"

"Not openly," answered the other. "But I know they're working at it still. And I can't and won't marry Molly with this cloud hanging over my head. I've got to disprove it."

"Yes, but, my dear, it's no good to me if you disprove it by being killed yourself," cried the girl. Then she turned to Ronald. "That's where we thought that perhaps you could help us, Mr. Standish. If only you can clear Billy's name, why—"

"Yes, but, my dear, it's no good to me if you disprove

it by being killed yourself," cried the girl.

She clasped her hands together beseechingly, and Standish gave her a reassuring smile.

"I'll try, Miss Tremayne—I can't do more than that. And now I think we'll get to business at once. I want to examine that bedroom."

RONALD STANDISH remained sunk in thought during the drive to Staveley Grange. Molly had not come with us, and neither Mansford nor I felt much inclined to conversation. He, poor devil, kept searching Ronald's face with a sort of pathetic eagerness, almost as if he expected the mystery to be already solved.

And then, just as we were turning into the drive, Ronald spoke for the first time.

"Have you slept in that room since your brother's death, Mansford?"

"No," answered the other, a little shamefacedly. "To tell the truth, Molly extracted a promise from me that I wouldn't."

"Wise of her," said Standish tersely, and relapsed into silence again.

"But you don't think—" began Mansford.

"I think nothing," snapped Standish, and at that moment the car drew up at the door.

It was opened by an elderly man with side whiskers, whom I placed as the butler—Templeton. He was a typical, old-fashioned manservant of the country-house type, and he bowed respectfully when Mansford told him what we had come for.

"I am thankful to think there is any chance, sir, of clearing up this terrible mystery," he said earnestly. "But I fear, if I may say so, that the matter is beyond earthly hands." His voice dropped, to prevent the two footmen overhearing. "We have prayed, sir, my wife and I, but there are more things in heaven and earth than we can account for. You wish to go to the room, sir? It is unlocked."

He led the way up the stairs and opened the door.

"Everything, sir, is as it was on the morning when Mr. Tom—er—died. Only the bedclothes have been removed."

He bowed again and left the room, closing the door.

"Poor old Templeton," said Mansford. "He's convinced that we are dealing with a ghost. Well, here's the room, Standish—just as it was. As you see, there's nothing very peculiar about it."

Ronald made no reply. He was standing in the centre of the room taking in the first general impression of his surroundings. He was completely absorbed, and I made a warning sign to Mansford not to speak. The twinkle had left his eyes: his expression was one of keen concentration. And, after a time, knowing the futility of speech, I began to study the place on my own account.

It was a big, square room, with a large double bed of the old-fashioned type. Over the bed was a canopy, made fast to the two bedposts at the head, and supported at the foot by two wires attached to the two corners of the canopy and two staples let into the wall above the windows. The bed itself faced the windows, of which there were two, placed symmetrically in the wall opposite, with a writing table in between them. The room was on the first floor in the centre of the house, and there was thus only one outside wall—that facing the bed. A big open fireplace and a lavatory basin with water laid on occupied most of one wall; two long built-in cupboards filled up the other. Beside the bed, on the fireplace side, stood a small table, with a special clip attached to the edge for the speaking-tube. In addition there stood on this table a thing not often met with in a private house in England. It was a small, portable electric fan, such as one finds on board ship or in the tropics.

There were two or three easy chairs standing on the heavy pile carpet, and the room was lit by electric light. In fact the whole tone was solid comfort, not to say luxury; it looked the last place in the world with which one would have associated anything ghostly or mysterious.

Suddenly Ronald Standish spoke.

"Just show me, will you, Mansford, as nearly as you can, exactly the position in which you found your father."

With a slight look of repugnance, the Australian got on to the bed.

"There were bedclothes, of course, and pillows which are not here now, but allowing for them, the poor old man was hunched up somehow like this. His knees were drawn up: the speaking-tube was in his hand, and he was staring towards that window."

"I see," said Standish. "The window on the right as we look at it. And your brother now. When he was found he was lying over the rail at the foot of the bed. Was he on the right side or the left?

"On the right," said Mansford, "almost touching the upright."

Once again Standish relapsed into silence and stared thoughtfully round the room. The setting sun was pouring in through the windows, and suddenly he gave a quick exclamation. We both glanced at him and he was staring up at the ceiling with a keen, intent look on his face. The next moment he had climbed on to the bed, and, standing up, he examined the two wire stays which supported the canopy. He touched each of them in turn, and began to whistle under his breath. It was a sure sign that he had stumbled on something, but I knew him far too well to make any comment at that stage of the proceedings.

"Very strange," he remarked at length, getting down and lighting a cigarette.

"What is?" asked Mansford eagerly.

"The vagaries of sunlight," answered Standish, with an enigmatic smile. He was pacing up and down the room smoking furiously, only to stop suddenly and stare again at the ceiling.

"It's the clue," he said slowly. "It's the clue to everything. It must be. Though what that everything is I know no more than you. Listen, Mansford, and pay careful attention. This trail is too old to follow: in sporting parlance the scent is too faint. We've got to get it renewed: we've got to get your ghost to walk again. Now I've only the wildest suspicions to go on, but I have a feeling that that ghost will be remarkably shy of walking if there are strangers about. I'm just gambling on one very strange fact—so strange as to make it impossible to be an accident. When you go downstairs I shall adopt the role of advising you to have this room shut up. You will laugh at me, and announce your intention of sleeping in this room to-night. You will insist on clearing this matter up. Tom and I will go, and we shall return later to the grounds, where I see there is some very good cover. You will come to bed here—you will get into bed and switch out the light. You will give it a quarter of an hour, and then you will drop out of the window and join us. And we shall see if anything happens."

"But if we're all outside, how can we?" cried Mansford.

Standish smiled grimly. "You may take it from me," he remarked, "that if my suspicions are correct the ghost will leave a trail. And it's the trail I'm interested in—not the ghost. Let's go and don't forget your part."

"But, my God! Standish—can't you tell me a little more?"

"I don't know any more to tell you," answered Standish gravely. "All I can say is—as you value your life don't fall asleep in this room. And don't breathe a word of this conversation to a soul."

Ten minutes later he and I were on our way back to the Old Hall. True to his instructions Mansford had carried out his role admirably, as we came down the stairs and stood talking in the hall. He gave it to be understood that he was damned if he was going to let things drop: that if Standish had no ideas on the matter—well, he was obliged to him for the trouble he had taken—but from now on he was going to take the matter into his own hands. And he proposed to start that night. He had turned to one of the footmen standing by, and had given instructions for the bed to be made up, while Ronald had shrugged his shoulders and shaken his head.

"Understandable, Mansford," he remarked, "but unwise. My advice to you is to have that room shut up."

And the old butler, shutting the door of the car, had fully agreed.

"Obstinate, sir," he whispered, "like his father. Persuade him to have it shut up, sir—if you can. I'm afraid of that room—afraid of it."

"You think something will happen to-night, Ronald," I said as we turned into the Old Hall.

"I don't know, Tom," he said slowly. "I'm utterly in the dark—utterly. And if the sun hadn't been shining to-day while we were in that room, I shouldn't have even the faint glimmer of light I've got now. But when you've got one bit of a jig-saw, it saves trouble to let the designer supply you with a few more."

And more than that he refused to say. Throughout dinner he talked cricket with old Tremayne: after dinner he played him at billiards. And it was not until eleven o'clock that he made a slight sign to me, and we both said good-night.

"No good anyone knowing, Tom," he said as we went upstairs. "It's an easy drop from my window to the ground. We'll walk to Staveley Grange."

The church clock in the little village close by was striking midnight as we crept through the undergrowth towards the house. It was a dark night—the moon was not due to rise for another three hours—and we finally came to a halt behind a big bush on the edge of the lawn from which we could see the house clearly. A light was still shining from the windows of the fatal room, and once or twice we saw Mansford's shadow as he undressed. Then the light went out, and the house was in darkness: the vigil had begun.

For twenty minutes or so we waited, and Standish began to fidget uneasily.

"Pray heavens! he hasn't forgotten and gone to sleep," he whispered to me, and even as he spoke he gave a little sigh of relief. A dark figure was lowering itself out of the window, and a moment or two later we saw Mansford skirting the lawn. A faint hiss from Standish and he'd joined us under cover of the bush.

"Everything seemed perfectly normal," he whispered. "I got into bed as you said—and there's another thing I did too. I've tied a thread across the door, so that if the ghost goes in that way we'll know."

"Good," said Standish. "And now we can compose ourselves to wait. Unfortunately we mustn't smoke."

Slowly the hours dragged on, while we took it in turns to watch the windows through a pair of night glasses. And nothing happened—absolutely nothing. Once it seemed to me as if a very faint light—it was more like a lessening of the darkness than an actual light—came from the room, but I decided it must be my imagination. And not till nearly five o'clock did Standish decide to go into the room and explore. His face was expressionless: I couldn't tell whether he was disappointed or not. But Mansford made no effort to conceal his feelings: frankly he regarded the whole experiment as a waste of time.

And when the three of us had clambered in by the window he said as much.

"Absolutely as I left it," he said. "Nothing happened at all."

"Then, for heaven's sake, say so in a whisper," snapped Standish irritably, as he clambered on to the bed. Once again his objective was the right hand wire stay of the canopy, and as he touched it he gave a quick exclamation. But Mansford was paying no attention: he was staring with puzzled eyes at the electric fan by the bed.

"Now who the devil turned that on," he muttered. "I haven't seen it working since the morning Tom died." He walked round to the door. "Say, Standish—that's queer. The thread isn't broken—and that fan wasn't going when I left the room."

Ronald Standish looked more cheerful.

"Very queer," he said. "And now I think, if I was you, I'd get into that bed and go to sleep—first removing the thread from the door. You're quite safe now."

"Quite safe," murmured Mansford. "I don't understand."

"Nor do I—as yet," returned Standish. "But this I will tell you. Neither your father nor your brother died of heart failure, through seeing some dreadful sight. They were foully murdered, as, in all probability you would have been last night had you slept in this room."

"But who murdered them, and how and why?" said Mansford dazedly.

"That is just what I'm going to find out," answered Standish grimly.

AS we came out of the breakfast-room at the Old Hall three hours later, Standish turned away from us. "I'm going into the garden to think," he said. "I have a sort of feeling that I'm not being very clever. For the life of me at the moment I cannot see the connection between the canopy wire that failed to shine in the sunlight, and the electric fan that was turned on so mysteriously. I am going to sit under that tree over there. Possibly the link may come."

He strolled away, and Molly joined me. She was looking worried and distraite, as she slipped her hand through my arm.

"Has he found out anything, Tom?" she asked eagerly. "He seemed so silent and preoccupied at breakfast."

"He's found out something, Molly," I answered guardedly, "but I'm afraid he hasn't found out much. In fact, as far as my brain goes it seems to me to be nothing at all. But he's an extraordinary fellow," I added, reassuringly.

She gave a little shudder and turned away.

"It's too late, Tom," she said miserably.

"Oh! if only I'd sent for you earlier. But it never dawned on me that it would come to this. I never dreamed that Bill would be suspected. He's just telephoned through to me: that horrible man McIver—the Inspector from Scotland Yard—is up there now. I feel that it's only a question of time before they arrest him. And though he'll get off—he must get off if there's such a thing as justice—the suspicion will stick to him all his life. There will be brutes who will say that failure to prove that Bill did it, is a very different matter to proving that he didn't. But I'm going to marry him all the same, Tom—whatever he says. Of course, I suppose you know that he didn't get on too well with his father."

"I didn't," I answered. "I know nothing about him except just what I've seen."

"And the other damnable thing is that he was in some stupid money difficulty. He'd backed a bill or something for a pal and was let down, which made his father furious. Of course there was nothing in it, but the police got hold of it—and twisted it to suit themselves."

"Well, Molly, you may take it from me," I said reassuringly, "that Bob Standish is certain he had nothing to do with it."

"That's not much good, Tom," she answered with a twisted smile. "So am I certain, but I can't prove it."

With a little shrug of her shoulders she turned and went indoors, leaving me to my own thoughts. I could see Standish in the distance, with his head enveloped in a cloud of smoke, and after a moment's indecision I started to stroll down the drive towards the lodge. It struck me that I would do some thinking on my own account, and see if by any chance I could hit on some solution which would fit the facts. And the more I thought the more impossible did it appear: the facts at one's disposal were so terribly meagre.

What horror had old Mansford seen coming at him out of the darkness, which he had tried to ward off even as he died? And was it the same thing that had come to his elder son, who had sprung forward revolver in hand, and died as he sprang? And again, who had turned on the electric fan? How did that fit in with the deaths of the other two? No one had come in by the door on the preceding night: no one had got in by the window. And then suddenly I paused, struck by a sudden idea. Staveley Grange was an old house—early sixteenth century; just the type of house to have secret passages and concealed entrances...There must be one into the fatal room: it was obvious.

Through that door there had crept some dreadful thing—some man, perhaps, and if so the murderer himself—disguised and dressed up to look awe-inspiring. Phosphorus doubtless had been used—and phosphorus skilfully applied to a man's face and clothes will make him sufficiently terrifying at night to strike tenor into the stoutest heart. Especially someone just awakened from sleep. That faint luminosity which we thought we had seen the preceding night was accounted for, and I almost laughed at dear old Ronald's stupidity in not having looked for a secret entrance. I was one up on him this time.

Mrs. Bretherton's story came back to me—her so-called nightmare—in which she affirmed she had been touched by a shining skinny hand. Shining—here lay the clue—the missing link. The arm of the murderer only was daubed with phosphorus; the rest of his body was in darkness. And the terrified victim waking suddenly would be confronted with a ghastly shining arm stretched out to clutch his throat.

A maniac probably—the murderer: a maniac who knew the secret entrance to Staveley Grange: a homicidal maniac—who had been frightened in his foul work by Mrs. Bretherton's shrieks, and had fled before she had shared the same fate as the Mansfords. Then and there I determined to put my theory in front of Ronald. I felt that I'd stolen a march on him this time at any rate.

I found him still puffing furiously at his pipe, and he listened in silence while I outlined my solution with a little pardonable elation.

"Dear old Tom," he said as I finished. "I congratulate you. The only slight drawback to your idea is that there is no secret door into the room."

"How do you know that?" I cried. "You hardly looked."

"On the contrary, I looked very closely. I may say that for a short while I inclined to some such theory as the one you've just put forward. But as soon as I saw that the room had been papered I dismissed it at once. As far as the built-in cupboard was concerned, it was erected by a local carpenter quite recently, and any secret entrance would have been either blocked over or known to him. Besides McIver has been in charge of this case—Inspector McIver from Scotland Yard. Now he and I have worked together before, and I have the very highest opinion of his ability. His powers of observation are extraordinary, and if his powers of deduction were as high he would be in the very first flight. Unfortunately he lacks imagination. But what I was leading up to was this. If McIver failed to find a secret entrance, it would be so much waste of time looking for one oneself. And if he had found one, he wouldn't have been able to keep it dark. We should have heard about it sharp enough."

"Well, have you got any better idea," I said a little peevishly. "If there isn't any secret door, how the deuce was that fan turned on?"

"There is such a thing as a two-way switch," murmured Ronald mildly. "That fan was not turned on from inside the room: it was turned on from somewhere else. And the person who turned it on was the murderer of old Mansford and his son."

I stared at him in amazement.

"Then all you've got to do," I cried excitedly, "is to find out where the other terminal of the two-way switch is? If it's in someone's room you've got him."

"Precisely, old man. But if it's in a passage, we haven't. And here, surely, is McIver himself. I wonder how he knew I was here?"

I turned to see a short thick-set man approaching us over the lawn.

"He was up at Staveley Grange this morning," I said. "Mansford telephoned through to Molly."

"That accounts for it then," remarked Standish waving his hand at the detective. "Good-morning, Mac."

"Morning, Mr. Standish," cried the other. "I've just heard that you're on the track, so I came over to see you."

"Splendid," said Standish. "This is Mr. Belton—a great friend of mine—who is responsible for my giving up a good week's cricket and coming down here. He's a friend of Miss Tremayne's."

McIver looked at me shrewdly.

"And therefore of Mr. Mansford's, I see."

"On the contrary," I remarked. "I never met Mr. Mansford before yesterday.

"I was up at Staveley Grange this morning," said McIver, "and Mr. Mansford told me you'd all spent the night on the lawn."

I saw Standish give a quick frown, which he instantly suppressed.

"I trust he told you that in private, McIver."

"He did. But why?"

"Because I want it to be thought that he slept in that room," answered Standish. "We're moving in deep waters, and a single slip at the present moment may cause a very unfortunate state of affairs."

"In what way?" grunted McIver.

"It might frighten the murderer," replied Standish. "And if he is frightened, I have my doubts if we shall ever bring the crime home to him. And if we don't bring the crime home to him, there will always be people who will say that Mansford had a lot to gain by the deaths of his father and brother."

"So you think it was murder?" said McIver slowly, looking at Standish from under his bushy eyebrows.

Ronald grinned. "Yes, I quite agree with you on that point."

"I haven't said what I think!" said the detective.

"True, McIver—perfectly true. You have been the soul of discretion. But I can hardly think that Scotland Yard would allow themselves to be deprived of your valuable services for two months while you enjoyed a rest cure in the country. Neither a ghost nor two natural deaths would keep you in Devonshire."

McIver laughed shortly.

"Quite right, Mr. Standish. I'm convinced it's murder: it must be. But frankly speaking, I've never been so absolutely floored in all my life. Did you find out anything last night?"

Standish lit a cigarette.

"Two very interesting points—two extremely interesting points, I may say, which I present to you free, gratis and for nothing. One of the objects of oil is to reduce friction, and one of the objects of an electric fan is to produce a draught. And both these profound facts have a very direct bearing on..." He paused and stared across the lawn. "Hullo! here is our friend Mansford in his car. Come to pay an early call, I suppose."

The Australian was standing by the door talking to his fiancée, and after a glance in their direction, McIver turned back to Ronald.

"Well, Mr. Standish, go on. Both those facts have a direct bearing on—what?"

But Ronald Standish made no reply. He was staring fixedly at Mansford, who was slowly coming towards us talking to Molly Tremayne. And as he came closer, it struck me that there was something peculiar about his face. There was a dark stain all round his mouth, and every now and then he pressed the back of his hand against it as if it hurt.

"Well, Standish," he said with a laugh, as he came up, "here's a fresh development for your ingenuity. Of course," he added, "it can't really have anything to do with it, but it's damned painful. Look at my mouth."

"I've been looking at it," answered Ronald. "How did it happen?"

"I don't know. All I can tell you is that about an hour ago it began to sting like blazes and turn dark red."

And now that he had come closer, I could see that there was a regular ring all round his mouth, stretching up almost to his nostrils and down to the cleft in his chin. It was dark and angry-looking, and was evidently paining him considerably.

"I feel as if I'd been stung by a family of hornets," he remarked. "You didn't leave any infernal chemical in the telephone, did you, Inspector McIver?"

"I did not," answered the detective stiffly, to pause in amazement as Standish uttered a shout of triumph.

"I've got it!" he cried. "The third point—the third elusive point. Did you go to sleep this morning as I suggested, Mansford?"

"No, I didn't," said the Australian, looking thoroughly mystified. "I sat up on the bed puzzling over that darned fan for about an hour, and then I decided to shave. Well, the water in the tap wasn't hot, so—"

"You blew down the speaking-tube to tell someone to bring you some," interrupted Standish quietly.

"I did," answered Mansford. "But how the devil did you know?"

"Because one of the objects of a speaking-tube, my dear fellow, is to speak through. Extraordinary how that simple point escaped me. It only shows, McIver, what I have invariably said: the most obvious points are the ones which most easily elude us. Keep your most private papers loose on your writing-table, and your most valuable possessions in an unlocked drawer, and you'll never trouble the burglary branch of your insurance company."

"Most interesting," said McIver with ponderous sarcasm. "Are we to understand, Mr. Standish, that you have solved the problem?"

"Why, certainly," answered Ronald, and Mansford gave a sharp cry of amazement. "Oil reduces friction, an electric fan produces a draught, and a speaking-tube is a tube to speak through secondarily; primarily, it is just—a tube. For your further thought, McIver, I would suggest to you that Mrs. Bretherton's digestion was much better than is popularly supposed, and that a brief perusal of some chemical work, bearing in mind Mr. Mansford's remarks that he felt as if he'd been stung by a family of hornets, would clear the air."

"Suppose you cease jesting, Standish," said Mans-ford a little brusquely. "What exactly do you mean by all this?"

"I mean that we are up against a particularly clever and ingenious murderer," answered Standish gravely. "Who he is—I don't know; why he's done it—I don't know; but one thing I do know—he is a very dangerous criminal. And we want to catch him in the act. Therefore, I shall go away to-day; McIver will go away to-day; and you, Mansford, will sleep in that room again to-night. And this time, instead of you joining us on the lawn—we shall all join you in the room. Do you follow me?"

"I follow you," said Mansford excitedly. "And we'll catch him in the act."

"Perhaps," said Standish quietly. "And perhaps we may have to wait a week or so. But we'll catch him, provided no one says a word of this conversation."

"But look here, Mr. Standish," said McIver peevishly. "I'm not going away to-day. I don't understand all this rigmarole of yours, and..."

"My very good Mac," laughed Standish. "you trot away and buy a ticket to London. Then get out at the first stop and return here after dark. And I'll give you another point to chew the cud over. Mrs. Bretherton was an elderly and timorous lady, and elderly and timorous ladies, I am told, put their heads under the bed-clothes if they are frightened. Mr. Mansford's father and brother were strong virile men, who do not hide their heads under such circumstances. They died, and Mrs. Bretherton lived. Think it over—and bring a gun to-night."

For the rest of the day we saw no sign of Ronald Standish. He had driven off in the Tremayne's car to the station, and had taken McIver with him. And there we understood from the chauffeur they had both taken tickets to London and left the place. Following Ronald's instructions, Mansford had gone back to Staveley Grange, and announced the fact of their departure, at the same time stating his unalterable intention to continue occupying the fatal room until he had solved the mystery. Then he returned to the Old Hall, where Molly, he and I spent the day, racking our brains in futile endeavours to get to the bottom of it.

"What beats me," said Mansford, after we had discussed every conceivable and inconceivable possibility, "is that Standish can't know any more than we do. We've both seen exactly what he's seen; we both know the facts just as well as he does. We're neither of us fools, and yet he can see the solution—. and we can't."

"It's just there that he is so wonderful," I answered thoughtfully. "He uses his imagination to connect what are apparently completely disconnected facts. And you may take it from me, Mansford, that he's very rarely wrong."

The Australian pulled at his pipe in silence.

"I think we'll find everything out to-night," he said at length. "Somehow or other I've got great faith in that pal of yours. But what is rousing my curiosity almost more than how my father and poor old Tom were murdered is who did it? Everything points to it being someone in the house—but in heaven's name, who? I'd stake my life on the two footmen—one of them came over with us from Australia. Then there's that poor old boob Templeton, who wouldn't hurt a fly—and his wife, and the other women servants, who, incidentally, are all new since Tom died. It beats me—beats me utterly."

For hours we continued the unending discussion, while the afternoon dragged slowly on. At six o'clock Mansford rose to go: his orders were to dine at home. He smiled reassuringly at Molly, who clung to him nervously; then with a cheerful wave of his hand he vanished down the drive. My orders were equally concise: to dine at the Old Hall—wait there until it was dark, and then make my way to the place where Standish and I had hidden the previous night.

It was not till ten that I deemed it safe to go; then slipping a small revolver into my pocket, I left the house by a side door and started on my three-mile walk.

As before, there was no moon, and in the shadow of the undergrowth I almost trod on Ronald before I saw him.

"That you, Tom?" came his whisper, and I lay down at his side. I could dimly see McIver a few feet away, and then once again began the vigil. It must have been about half-past eleven that the lights were switched on in the room, and Mansford started to go to bed. Once he came to the window and leaned out, seeming to stare in our direction; then he went back to the room, and we could see his shadow as he moved about. And I wondered if he was feeling nervous.

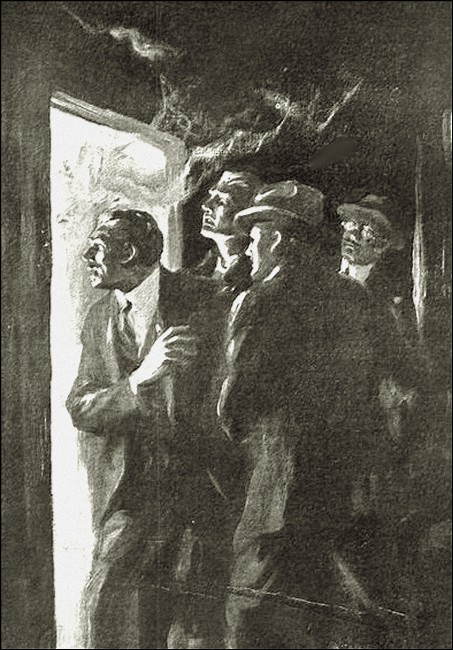

At last the light went out, and almost at once Standish rose.

"There's no time to lose," he muttered. "Follow me—and not a sound."

Swiftly we crossed the lawn and clambered up the old buttressed wall to the room above. I heard Ronald's whispered greeting to Mansford, who was standing by the window in his pyjamas, and then McIver joined us, blowing slightly. Climbing walls was not a common form of exercise as far as he was concerned.

"Don't forget," whispered Standish again, "not a sound, not a whisper. Sit down and wait."

He crossed to the table by the bed—the table on which stood the motionless electric fan. Then he switched on a small electric torch, and we watched him eagerly as he took up the speaking-tube. From his pocket he extracted what appeared to be a hollow tube some three inches long, with a piece of material attached to one end. This material he tied carefully round the end of the speaking-tube, thereby forming a connection between the speaking-tube and the short hollow one he had removed from his pocket. And finally he placed a cork very lightly in position at the other end of the metal cylinder. Then he switched off his torch and sat down on the bed. Evidently his preparations were complete; there was nothing to do now but wait.

The ticking of the clock on the mantelpiece sounded incredibly loud in the utter silence of the house. One o'clock struck—then half-past—when suddenly there came a faint pop from near the bed which made me jump violently. I heard Ronald drawing his breath sharply and craned forward to see what was happening. There came a gentle rasping noise, as Standish lit his petrol cigarette lighter. It gave little more light than a flickering glimmer, but it was just enough for me to see what he was doing. He was holding the flame to the end of the hollow tube, in which there was no longer a cork. The little pop had been caused by the cork blowing out. And then to my amazement a blue flame sprang from the end of the tube, and burnt steadily. It burnt with a slight hiss, like a bunsen burner in a laboratory—and it gave about the same amount of light. One could just see Ronald's face looking white and ghostly; then he pulled the bed curtain round the table, and the room was in darkness once again.

McIver was sitting next to me and I could hear his hurried breathing over the faint hiss of the hidden flame. And so we sat for perhaps ten minutes, when a board creaked in the room above us.

"It's coming now," came in a quick whisper from Ronald. "Whatever I do—don't speak, don't make a sound."

I make no bones about it, but my heart was going in great sickening thumps. I've been in many tight corners in the course of my life, but this silent room had got my nerves stretched to the limit. And I don't believe McIver was any better. I know I bore the marks of his fingers on my aim for a week after.

"My God! look," I heard him breathe, and at that moment I saw it. Up above the window on the right a faint luminous light had appeared, in the centre of which was a hand. It wasn't an ordinary hand—it was a skinny, claw-like talon, which glowed and shone in the darkness. And even as we watched it, it began to float downwards towards the bed. Steadily and quietly it seemed to drift through the room—but always towards the bed. At length it stopped, hanging directly over the foot of the bed and about three feet above it.

The sweat was pouring off my face in streams, and I could see young Mansford's face in the faint glow of that ghastly hand, rigid and motionless with horror. Now for the first time he knew how his father and brother had died—or he would know soon. What was this dismembered talon going to do next? Would it float forward to grip him by the throat—or would it disappear as mysteriously as it had come?

I tried to picture the dreadful terror of waking up suddenly and seeing this thing in front of one in the darkened room; and then I saw that Ronald was about to do something. He was kneeling on the bed examining the apparition in the most matter of fact way, and suddenly he put a finger to his lips and looked at us warningly. Then quite deliberately he hit at it with his fist, gave a hoarse cry, and rolled off the bed with a heavy thud.

He was on his feet in an instant, again signing to us imperatively to be silent, and we watched the thing swinging backwards and forwards as if it was on a string. And now it was receding—back towards the window and upwards just as it had come, while the oscillations grew less and less, until, at last it had vanished completely, and the room once more was in darkness save for the faint blue flame which still burnt steadily at the end of the tube.

"My God!" muttered McIver next to me, as he mopped his brow with a handkerchief, only to be again imperatively silenced by a gesture from Standish. The board creaked in the room above us, and I fancied that I heard a door close very gently: then all was still once more.

Suddenly with disconcerting abruptness the blue flame went out, almost as if it had been a gas jet turned off. And simultaneously a faint whirring noise and a slight draught on my face showed that the electric fan had been switched on. Then we heard Ronald's voice giving orders in a low tone. He had switched on his torch, and his eyes were shining with excitement.

"With luck we'll get the last act soon," he muttered. "Mansford, lie on the floor, as if you'd fallen off the bed. Sprawl: sham dead, and don't move. We three will be behind the curtain in the window. Have you got handcuffs, Mac," he whispered as we went to our hiding place. "Get 'em on as soon as possible, because I'm inclined to think that our bird will be dangerous."

McIver grunted, and once again we started to wait for the unknown. The electric fan still whirred, and looking through the window I saw the first faint streaks of dawn. And then suddenly Standish gripped my arm; the handle of the door was being turned. Slowly it opened, and someone came in shutting it cautiously behind him. He came round the bed, and paused as he got to the foot. He was crouching—bent almost double—and for a long while he stood there motionless. And then he began to laugh, and the laugh was horrible to hear. It was low and exulting—but it had a note in it which told its own story. The man who crouched at the foot of the bed was a maniac.

"On him," snapped Ronald, and we sprang forward simultaneously. The man snarled and fought like a tiger—but madman though he was he was no match for the four of us. Mansford had sprung to his feet the instant the fight started, and in a few seconds we heard the click of McIver's handcuffs. It was Standish who went to the door and switched on the light, so that we could see who it was. And the face of the handcuffed man, distorted and maniacal in its fury, was the face of the butler Templeton.

"Pass the handcuffs round the foot of the bed, McIver," ordered Standish. "and we'll leave him here. We've got to explore upstairs now."

McIver slipped off one wristlet, passed it round the upright of the bed and snapped it to again. Then the four of us dashed upstairs.

"We want the room to which the speaking-tube communicates," cried Standish, and Mansford led the way. He flung open a door, and then with a cry of horror stopped dead in the doorway.

Confronting us was a wild-eyed woman, clad only in her nightdress. She was standing beside a huge glass retort, which bubbled and hissed on a stand in the centre of the room. And even as we stood there she snatched up the retort with a harsh cry, and held it above her head.

"Back," roared Standish, "back for your lives."

"Back," roared Standish, "back for your lives."

But it was not to he. Somehow or other the retort dropped from her hands and smashed to pieces on her own head. And a scream of such mortal agony rang out as I have never heard and hope never to hear again. Nothing could be done for her; she died in five minutes, and of the manner of the poor demented thing's death it were better not to write. For a large amount of the contents of the retort was hot sulphuric acid.

"WELL, Mansford," said Standish a few hours later, "your ghost is laid, your mystery is solved, and I think I'll be able to play in the last match of that tour after all."

We were seated in the Old Hall dining-room after an early breakfast and Mansford turned to him eagerly.

"I'm still in the dark," he said. "Can't you explain?"

Standish smiled. "Don't see it yet? Well—it's very simple. As you know, the first thing that struck my eye was that right-hand canopy wire. It didn't shine in the sun like the other one, and when I got up to examine it, I found it was coated with dried oil. Not one little bit of it—but the whole wire. Now that was very strange—very strange indeed. Why should that wire have been coated with oil—and not the other? I may say at once that I had dismissed any idea of psychic phenomena being responsible for your father's and brother's death. That such things exist we know—but they don't kill two strong men.

"However, I was still in the dark; in fact, there was only one ray of light. The coating of that wire with oil was so strange, that of itself it established with practical certainty the fact that a human agency was at work. And before I left the room that first afternoon I was certain that that wire was used to introduce something into the room from outside. The proof came the next morning. Overnight the wire had been dry; the following morning there was wet oil on it. The door was intact; no one had gone in by the window, and, further, the fan was going. Fact number two. Still, I couldn't get the connection. I admit that the fact that the fan was going suggested some form of gas—introduced by the murderer, and then removed by him automatically. And then you came along with your mouth blistered. You spoke of feeling as if you'd been stung by a hornet, and I'd got my third fact. To get it pre-supposed a certain knowledge of chemistry. Formic acid—which is what a wasp's sting consists of—can be used amongst other things for the manufacture of carbon monoxide. And with that the whole diabolical plot was clear. The speaking-tube was the missing link, through which carbon monoxide was poured into the room, bringing with it traces of the original ingredients which condensed on the mouthpiece. Now, as you may know, carbon monoxide is lighter than air, and is a deadly poison to breathe. Moreover, it leaves no trace—certainly no obvious trace. So before we went into the room last night, I had decided in my own mind how the murders had taken place. First from right under the sleeper's nose a stream of carbon monoxide was discharged, which I rendered harmless by igniting it. The canopy helped to keep it more or less confined, but since it was lighter than air, something was necessary to make the sleeper awake and sit up. That is precisely what your father and brother did when they saw the phosphorescent hand—and they died at once. Mrs. Bretherton hid her face and lived. Then the fan was turned on—the carbon monoxide was gradually expelled from the room, and in the morning no trace remained. If it failed one night it could be tried again the next until it succeeded. Sooner or later that infernal hand travelling on a little pulley wheel on the wire and controlled from above by a long string, would wake the sleeper—and then the end—or the story of a ghost."

He paused and pressed out his cigarette.

"From the very first also I had suspected Templeton. When you know as much of crime as I do—you're never surprised at anything. I admit he seemed the last man in the world who would do such a thing—but there are more cases of Jekyll and Hyde than we even dream of. And he and his wife were the only connecting links in the household staff between you and the Brethertons. That Mrs. Templeton also was mad had not occurred to me, and how much she was his assistant or his dupe we shall never know. She has paid a dreadful price, poor soul, for her share of it; the mixture that broke over her was hot concentrated sulphuric acid mixed with formic acid. Incidentally from inquiries made yesterday, I discovered that Staveley Grange belonged to a man named Templeton some forty years ago. This man had an illegitimate son, whom he did not provide for—and it may be that Templeton the butler is that son—gone mad. Obsessed with the idea that Staveley Grange should be his perhaps—who knows? No man can read a madman's mind."

He lit another cigarette and rose.

"So I can't tell you why. How you know and who: why must remain a mystery for ever. And now I think I can just catch my train."

"Yes, but wait a moment," cried Mansford. "There are scores of other points I'm not clear on."

"Think 'em out for yourself, my dear fellow," laughed Ronald. "I want to make a few runs to-morrow."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.