RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Macleans, 15 October 1929, with "Fer de Lance"

A poignant drama of exile in the tropics.

CEASELESSLY the machine went on. It worked somewhat on the principle of a moving staircase. An endless canvas band, lying loosely over crosspieces placed at intervals, formed a series of ever-advancing cradles, which vanished, each with its load, into the hold. Then the band, flattening out underneath for its return journey, came back for more.

Everything worked with the smoothness born of long practice. Overhead the garish spluttering arc lights hissed, throwing crude shadows on train and boat alike. Occasionally with the harsh clanging of a bell the engine would move forward a few yards, in order to bring the opening of another truck opposite the loading machine. A moment's respite while the train moved, and then down to it again. No pause, no respite: the s.s. Barare was loading bananas, and it was an all-night job. Stem after stem of the fruit—still green—was carried out of the truck by natives and placed each in its separate moving cradle, only to be seized by other natives inside the ship and stowed away in the hold.

Seated on a raised stand was an unshaven, bleary-eyed man. In front of him was a pad on which he checked the number of stems loaded; just as he had checked them for years—or was it centuries? Bananas: millions of stems of bananas had he recorded on paper—until the word banana drove him frantic. He loathed bananas with a loathing that passed description. On the occasions when he had delirium tremens—and they were not infrequent—no imaginary animals haunted him. He was denied a rat of any hue. Only bananas: bananas of all shapes and sizes and colours thronged in on his bemused brain, till the whole world seemed full of them.

He was a strange personality—this unkempt checker, and how he had held his job for nearly three years was stranger still. Perhaps the answer could only have been given by the quiet, clean-cut man who was his boss—a strange personality himself. For rumour had it that on one occasion, when a ship was loading, the boss had gone on board as usual. And as he reached the top of the companion he ran straight into a certain Austrian nobleman, who gave a startled gasp of amazement before drawing himself up and bowing punctiliously. Rumour had it also that that same nobleman, having paced the deck with him for a while, was heard to call him "Sir."

An ill-assorted pair, one would have thought—a drunken, down-and-out Englishman and a man whom an Austrian of ancient family called "Sir." And perhaps the reason lay in the fact that the epithet "down-and-out" is only relative. Once the crash has come, a bond of sympathy exists between those who crash, even though their falls are of different height.

The Englishman called himself Robinson when he was sober enough to remember. At other times he was apt to give a different name. The boss called himself Barlock, which, as a name, had certain advantages. It left one in doubt as to the nationality of its owner. And the two men had arrived at Port Limon about the same time in very different capacities Barlock was taking over a responsible post in the Union Fruit Company, that vast American concern whose tentacles stretch into every corner of the West Indies and Central America. Robinson was merely drunk. He arrived as a deckhand in an old tramp, and, being temporarily mislaid when she sailed again, was left behind without lamentation or regret. And acquaintance between the two men started almost at once in a somewhat peculiar way.

Barlock was wandering round the big railway shed, which was to be the scene of his labours for the next few years, and as he stepped behind some barrels he walked on the other man.

"Don't apologise," remarked Robinson, getting unsteadily to his feet. "I'm used to it. Would you tell me if a bilge-laden old tub, whose name escapes me for the moment, has sailed?"

"If you mean the Corsica," said the other, "she sailed about six hours ago."

"It would appear, then, that I have been left behind. Not that it matters in the slightest degree. I have long given up any attempt at regularity in my habits. One small point, however, might be of interest. Where am I?"

Barlock smiled faintly: there was a certain whimsical note in the other's voice that amused him.

"This is Port Limon," he answered. "And in the event of your geography having been as much neglected as mine was, Port Limon is in Costa Rica."

"Costa Rica," said the other, thoughtfully. "Its exact position on the globe is a little beyond me at the moment, but, provided it possesses a bar, it fulfils all my requirements."

He shambled off, leaving the other staring after him. A gentleman obviously: equally obviously a drunkard. And for a moment or two Barlock wondered how the mixture would be digested by the narrow strip of civilisation that lies at the bottom of the densely-wooded hills which make up the greater part of the republic. Then with a shrug of his shoulders he went about his lawful occasions.

For a week he saw Robinson no more. Then one night he found him standing at his elbow. A banana train had just creaked into the station, its bell clanging furiously. Natives were lethargically replacing greasy packs of cards in their pockets; Port Limon's justification for existence came to a groaning standstill. No bananas: no Port Limon.

"It is incredible," remarked Robinson, "that human stomachs can consume such inordinate quantities of vegetable matter. I am not a banana maniac myself, unless they are soaked in rum. And even then—why spoil the rum? But when one sees that train, and realises that there are other trains in other places all carrying bananas, one takes off one's hat in silent homage to the world's eaters. By the way, I suppose you haven't the price of a drink on you?"

A sudden idea struck Barlock.

"I have not," he said, shortly. "But I'll give you a job of work. Go and help load them. You'll get the same rate of pay as the natives."

For a moment the other hesitated: it was black man's work. Then finding Barlock's steady eye fixed on him, he gave a short laugh and peeled off his coat. And thus began his personal acquaintance with bananas. Began also a strange relationship between the two men.

Friendship it could hardly be called. Their positions were too widely separated. Barlock was the boss; Robinson a paid hand doing coolie work. But through the long nights, whilst the loading went monotonously on, sometimes the difference between them disappeared. They became just two white men amongst a crowd of blacks. Moreover, they became two white men of the same interests and station. Away from the railway shed it was different. Bar-lock, by reason of his job, belonged to the club, and could enjoy what social life the place afforded; Robinson was down and out, living native fashion. But under the hissing arc lights the two men met on a common ground—bananas.

And then there occurred an incident which insensibly brought them nearer to one another. If a competition open to the world for the number of snakes to the square yard was instituted, Costa Rica would be very near the top of the list. Moreover, her representatives would not be of the harmless variety. And it so happens that on occasions members of the fraternity go to ground in the bunches of fruit as they lie stacked beside the railway line, waiting to be picked up by the train. The snake hides itself along the stem, and may or may not be discovered at the up-country siding. If it is, it is promptly dispatched; if it is not, it makes the journey to Port Limon. And so at that terminus the danger is an ever-present one, especially as the snake, after having jolted down the line in a stuffy truck, is not in the best of tempers on its arrival.

It all happened very quickly—some six months after Robinson's introduction to his new trade. He had just taken a big stem of fruit from the man standing in the opening of the truck, when a native beside him gave a shout. He had a momentary glimpse of a wicked yellow head curving out of the fruit in his arms: then there came the thud of a stick, and he dropped the bunch.

He looked up a little stupidly to find Barlock standing beside him, the stick still grasped in his hand. And for a few moments the two men stared at one another in silence, whilst a native completed the good work on the platform.

"Fer de Lance," said Barlock, curtly. "Lucky I had a stick."

"Thanks," muttered Robinson, staring at the dead body of perhaps the most deadly brute in existence. "Thanks. Though I wonder if it was worth while."

"Don't talk rot," said Barlock, even more curtly, and moved away.

The incident was over; a Fer de Lance was dead. Robinson was alive. And there were still bananas to load. But when one man has saved another man's life, it is bound to make some difference in their relationship. And though nothing changed outwardly, though they still remained boss and paid hand, under the surface there was an alteration.

"Thanks once more," said Robinson, as the empty train pulled out the next morning. He had followed Barlock to his room in the station, and was standing in the open door. "You were deuced quick with that stick."

"Not much good moving by numbers when there is a bone-tail about," said Barlock with a laugh.

"So you're of the breed, are you?" Robinson stared at the other man. "I always thought you were by the set of your shoulders. By numbers. God! how it brings things back. Do you know our immortal songster? I've got a new last line to one of his things:—

"Gentlemen rankers out on the spree,

Damned from here to eternity.

God have mercy on such as we,

Ba—na—na.

"I load the damned things to the rhythm."

Barlock looked at him thoughtfully.

"What regiment?" he asked after a moment.

"Thirteenth Lancers," said the other. "And you?"

"Austrian Cavalry of the Guard," answered Bar-lock.

"Of course, I knew you weren't English," said Robinson, "though you speak it perfectly. So we went through that performance on different sides. Funny life, isn't it? Look here, I don't want to be impertinent or unduly curious. The reason for me is obvious: I can't keep away from the blasted stuff. But you—you don't drink."

Barlock smiled grimly.

"Have you ever thought, my friend, of the difference it makes when the last two o's are lopped off a man's income? The gap between fifty thousand and five hundred is considerable."

"So that's it, is it?" Said Robinson, and began to laugh weakly. "And our mutual life-belt is that rare and refreshing fruit the banana."

Suddenly he pulled himself together.

"By the way, there's just one thing I'd like to say. I don't suppose the situation is ever likely to arise, but it may do. There's a lot of tourist traffic passes through—and one never knows. I'm dead."

"I don't quite follow," said Barlock, quietly.

"I should have thought it was easy," remarked the other. "But I'll be more explicit. Six or seven years ago a regrettable accident took place. An extremely drunken man fell over 'Waterloo Bridge into the River Thames, and the only thing that was ever recovered was his hat. Wherefore after prolonged search the powers decided that the oner of the hat had been droned. The powers that be were wrong, but it would be a pity if they found out. There would be complications."

Barlock turned away abruptly; there are moments when a man may not look on another man's face.

"I see," he said, after a pause. "Your secret is safe with me."

"Complications," repeated Robinson, dully. "Damnable complications. Well—I'll be pushing on. Thanks again for that snake business."

He slouched off don the platform, and for a time the Austrian stood staring at his retreating back. Damnable complications: the words rang in his brain. Then, with a little shrug of his shoulders, he closed his door. For when one's job is to unload bananas by night, it is necessary to sleep by day.

It was a year afterwards that the official belief concerning Robinson was very nearly justified. Two trains came in, were unloaded and departed again, but of Robinson there was no sign. And after the second, Barlock made inquiries. It was not the first time that Robinson had missed a train, but never before had it been more than that. And the result of Barlock's inquiries was short and to the point. A more than usually fierce drinking bout, coupled with the intense heat—it was the end of July—had just about finished him off. In fact, Barlock's native informant stated that he was, in all probability, already dead. However, if the boss wished he would lead him to the house where the sick man was.

The boss did wish, though once or twice on the way he almost repented and turned back. There are degrees of filth and stench even in the native quarters of Port Limon, and it seemed to Barlock that his destination reached the lowest abyss in the scale. Verminous dogs slunk garbaging along the refuse-strewn gutter; naked children, the flies swarming round them, stared at him with wide-open eyes as he picked his way along the road. And over everything, like a hot wet blanket, pressed the tropical heat.

He thought with longing of the club at the other end of the ton, where what breeze there was came fresh from the sea, and where a man could wallow in the water through the stifling afternoon. After all, this man meant nothing to him. What was he save a broken-down waster belonging to a nation largely responsible for his own present condition? And then he laughed a little cynically. Whatever Robinson was he knew that he was going through with it. White is white, however far don it has sunk.

At last his guide turned through a ramshackle gate from which a short path, which was evidently the household dustbin, led to a dilapidated shanty. Seated outside the front door was a vast negress, who grinned expansively on seeing the white man. Her lodger was about the same, she told him, and would his honour walk in if he wished to see him. Bar-lock did so, dodging some hens that walked out simultaneously. And once again he almost chucked it. If the smell outside was bad, there at any rate it was not confined. But in the hovel he had just entered it was concentrated to such an extent that it produced a feeling of physical nausea. And then, as he stood there for a moment or two undecided, there came a hoarse voice from a room beyond.

"Steady, lads—steady! They're coming on again."

One of the breed, and they had gone through that performance on different sides. Yes—it had its humorous side, without doubt. Barlock crossed the room, and pulled aside a dirty hanging. Different sides, perhaps—but both were the same colour.

More hens scuttled out as he stood in the opening. The sick man was lying on some reeds in the corner, and as Barlock crossed to him he glanced up. His eyes showed no trace of recognition, and his visitor saw at once that matters were serious. It was a question of a doctor, and a doctor quickly.

Then his eyes caught sight of something that lay beside the sick man; he bent over him and removed it. And Robinson, delirious as he was, was not so far gone that that escaped him. He cursed foully, and tried to snatch it out of Barlock's hand, only to fall back weakly on the rushes.

"Listen, Robinson," said Barlock, speaking slowly and distinctly. "I'm going to get a doctor."

But the sick man only muttered and mouthed, and glared at his visitor with a look of venomous hatred.

"Now, you old devil," continued Barlock to the negress who had come shambling in, "if I find he has any more of this, you'll be sorry. Police after you, unless you're careful. I go get doctor."

He strode out, leaving the old woman shaking like a mountain of jelly. Then, having smashed to bits a bottle of illicit native spirit, he went in search of the one tolerable doctor the place boasted of. By luck he found him taking his siesta, and dragged him out despite his protests. And between them they saved what was left of Robinson.

Barlock did most of it. For hours on end when he was free did he sit beside the sick man, listening to his ravings—and in the course of those ravings learning the truth. And after a while a great pity for the wretched derelict took hold of him. For the first time he found out Robinson's real name, and truly the crash was greater than he had guessed. And for the first time he found out that' there was a woman involved.

At last came the day when the fever died out, and the sick man opened sane eyes to the world.

"Hullo!" he said, staring at Barlock, "have I been talking out of my turn?"

"Don't worry about that," answered the other quietly. "I'm the only person who has heard. And it's safe with me."

"You know who I am?" persisted Robinson, and Barlock nodded.

"Yes—I know who you are," he answered.

"You know I'm married. Or rather"—the smile was a little pitiful—"was married."

"I gathered so," said Barlock. "Look here—we'll talk it all over when you're a bit stronger. You go to sleep now."

Robinson shut his eyes wearily.

"Damnable complications," he muttered. "That's why I'm dead. Because Ulrica has married again."

And at that it was left. A fortnight later Robinson reported for duty again, but now there was a difference. The fever had left its indelible mark: the physical labour required for that continuous carrying of heavy bunches of fruit was beyond his powers. And so Barlock promoted him; he became assistant checker. Seated on his raised stand, he checked on the pad in front of him the number of stems loaded, and he went on checking them as each ship came in. Until in the fullness of time the s.s. Barare arrived, and, as usual, it was an all-night job.

Leaning over the ship's rail, watching the scene, was a tall, fair-haired man He was smoking, and every line of his figure breathed that lazy contentment which only a good cigar can give. Occasionally a faint smile flickered round his lips, at some monkey-like contortion of one of the niggers, but for the most part his face was that expressionless mask which is the hallmark of a certain type of Englishman.

Suddenly his eyes narrowed: he leaned forward, staring into the crowd below.

"Good God!" he muttered, "it can't be. But it is, by Jove!"

Barlock was coming up the gangway, and the tall, fair-haired man moved along the deck so that the two met at the top.

"But what astounding luck!" he cried. "My dear Baron—how are you? And what are you doing here?"

The faintest perceptible frown showed for a moment on Barlock's forehead.

"How are you, Lord Rankin?" he said. "But if you don't mind—not Baron. My name here is just Barlock."

The other stared at him in puzzled amazement.

"My dear fellow," he stammered, "I don't quite follow."

"And yet it's fairly easy," answered Barlock. "Financial considerations made it necessary for me to work. So I now superintend the loading of bananas for the Union Fruit Company. And since the job, though honest and homely, is hardly one that I ever saw myself doing in the past, I decided, temporarily at any rate, to drop my title."

"Well, I'm damned!" said the other, a little awkwardly. "You stagger me, my dear chap. One thing, however, is perfectly clear. Whatever your name is here, to me you are Baron von Studeman, who was amazingly good to a young military attache in Vienna. And I insist—first on your having a drink, and second on your meeting Ulrica."

"Ulrica!" said Barlock, standing of a sudden very still.

"My wife," explained the other. "I've been married seven years, old boy. Her young hopeful is below now, safely tucked up in the sheets."

But Barlock's eyes were fixed on the back of an unshaven, bleary-eyed man who was checking stems of bananas on a pad. Seven years: an uncommon name like Ulrica. Had the unexpected happened?

And then a peculiarity in the other's phrasing struck him.

"Her young hopeful!" he said with a slight smile.

"Yes," answered Lord Rankin. "My wife had been married before. He was droned, leaving her with a boy two years old."

Once again Barlock stared at the man with the pencil below.

"I see," he heard himself saying. "By the way, did you ever meet your wife's first husband?"

Lord Rankin raised his eyebrows. Loading bananas did not seem to have increased the Baron's tact.

"I did not," he said curtly, and changed the conversation.

But Barlock hardly heard what he was saying. The unexpected had happened. Back to his mind came the remembrance of that day when Robinson had stood in the doorway of his office. He saw once more the look on his face, heard once more those low-breathed words, "Damnable complications." And unless he did something the complications had arrived.

He tried to force himself to think clearly—to get the salient facts in his brain. There, on the dock, within fifteen yards of where he stood, was a man whose wife and child were on board the boat. At any moment Lady Rankin might appear, and what was going to happen then? For even if she did not recognise him, he would be bound to recognise her.

"Excuse me for a few minutes," he said. "There are one or two things I must see to on the quay."

"You'll come back?" cried the other, and Bar-lock nodded. At all costs he must speak to Robinson.

He went swiftly don the gangway, and crossed to the stand where he sat.

"Hullo, my noble boss!" said Robinson. "You seem a little agitated."

"Look here, Robinson," he said, quietly, "you've got to pull yourself together. Something that you have long feared has happened."

For a moment the other stared at him uncomprehendingly; then he sat up with a jerk.

"You mean that—"

"I mean that Lord Rankin is on board."

"And Ulrica?"

"Yes, she is on board, and your son."

"My God!" Mechanically he was ticking off the bunches as they passed. "My God!"

"Don't took round," went on Barlock. "Rankin is leaning over the rail now, and Lady Rankin has just joined him."

He watched the other stiffen, till the sweat dripped off his forehead on to the paper in front of him.

"If I could only see her once again," he muttered. "And the boy."

"But you mustn't," said Barlock, quietly. "Of course—you mustn't."

"Of course I mustn't," repeated Robinson, dully. "Why—no; you are right."

"So keep your back turned, Robinson," continued Barlock.

"Yes, I'll keep my back turned, Barlock. But tell me how she is looking, Barlock, and whether she still has that quaint little trick of hers of throwing her head sideways when she laughs. Go and talk to her, Barlock—while I go on counting bananas. And if maybe she did drop her handkerchief, why, I don't think she'd miss it much, would she, Barlock?"

"Hell!" grunted the other as he turned away. "You poor devil."

"Come along," came Lord Rankin's cheery hail. "We'll go and split a bottle."

"One thousand three hundred and twenty-one bunches up to date," said Robinson, with a twisted grin. "Yes—go and split a bottle, Barlock."

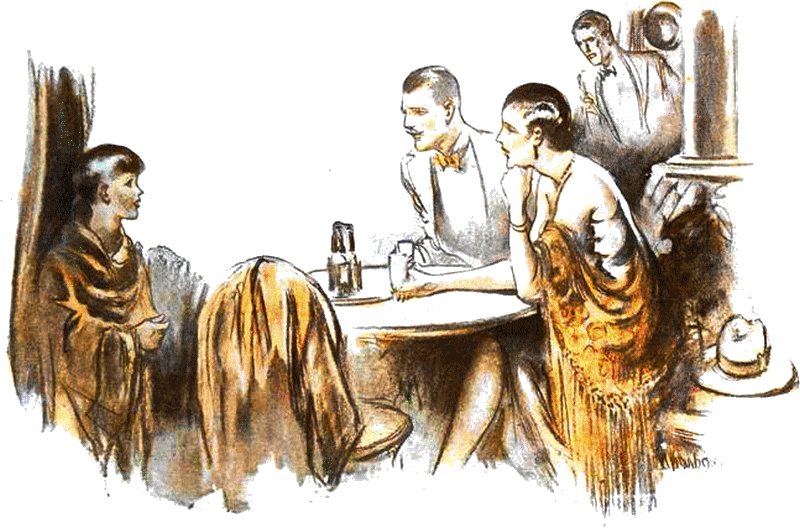

And with the feeling that the whole night was a dream from which he would wake soon, the Baron von Studeman went to split a bottle. It increased, that sense of unreality, as the three of them sat in the smoking-room, till he became conscious that his host was looking at him curiously. And he realised he was speaking at random and must pull himself together.

"All natives, I suppose?" said Rankin. "Don't you find it damned boring? Except that fellow you were talking to, who looked white."

"I rather think he is white," he answered, slowly. "As white as you or I."

It came unexpectedly, the sudden commotion on the platform outside. There was a hoarse shouting from the natives, and then some excited babbling.

"Probably only a snake," said Barlock, reassuringly. "They always lose their heads when one arrives in the bananas. Hullo! who is this young man?"

Standing in the open doorway was a small figure arrayed in a large dressing-gown.

"I say, mummie," remarked an enthusiastic treble voice, "I've had a priceless time. They've just walloped a snake."

"I say, Mummy, I've had a priceless time. They've just walloped a snake.

"Tommy!" cried his mother. "You naughty boy! Why aren't you in bed?"

"That funny machine woke me up," answered the child. "So I put my head out to look. And then I saw all the bananas. So I thought I'd go and see what was happening. There was such a nice gentleman sitting on a stool who wanted to know if I'd shake hands with him."

Barlock rose a little abruptly and stared out into the darkness.

"What's this about a snake, young fellah?" said Lord Rankin.

"Well, daddie, just as I was talking to this gentleman, somebody suddenly gave a shout. And I looked round, and there was a yellowy-green snake on the platform close to me. And the gentleman sort of fell out of his chair, and the snake bit him in the hand."

"What's that you say, laddie?" Barlock's voice seemed to come from a distance. "The snake bit him in the hand?"

"Why, yes," said the child. "And then he was so funny. He said, 'I used to field in the slips, old man,' and then he went away ever so quickly, while the natives killed the snake."

"Well, come to bed at once now," cried his mother. "It's nearly midnight."

She bustled him out, leaving the two men alone.

"Young devil," chuckled Lord Rankin. "Not going yet, von Studeman, are you?"

"For a little," returned the other evenly. "I will come back later."

But he searched for twenty minutes before he found Robinson. A glance told him it was too late. The end was very near. He had been bitten in the wrist, and nothing could be done.

"A bonnie kid, Barlock," he said, feebly. "I'm glad I saw him. Just got my hand there in time. It was one thousand seven hundred and thirty—"

The voice died away, and the man called Robinson lay still.

"A very narrow escape for the boy." It was an hour later, and the Baron von Studeman was standing with Lord Rankin on deck. "The snake was a Fer de Lance, one of the most deadly in the world. They generally remain in the bananas until the stem is lifted out. But this one apparently escaped in the truck; anyway, it was loose on the platform. And but for—Robinson's quickness, the kid would now be dead."

"Good God! It would have broken his mother's heart," said the other. "Where is this man, Robinson? Because I must thank him."

"I don't think you quite realise what happened, Rankin," said the Baron, quietly. "Robinson received the bite intended for the boy in his own wrist."

The other stared at him speechlessly.

"You don't mean—" he stammered, and the Baron nodded gravely.

"My God!" repeated the other. "This is too awful. Poor devil! Dead!"

He paced up and down in his agitation.

"Anything I could have done for him I would. You see, von Studeman, I didn't tell you before. But my wife's first husband was the most frightful waster. And it broke her up badly before he was drowned. Made her put everything into the kid. If anything had happened to him, I don't know what she'd have done. And this poor chap—dead. I can't get it somehow. Look here, I must do something. He was probably not too well off, and you could help me here. What about giving a present to his wife? He was married, I suppose?"

A queer smile flickered round the lips of the Baron von Studeman.

Below him the machine went on ceaselessly, for the s.s. Barare was loading bananas and it was an all-night job.

"Married?" he said. "Not that I'm aware of."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.